Abstract

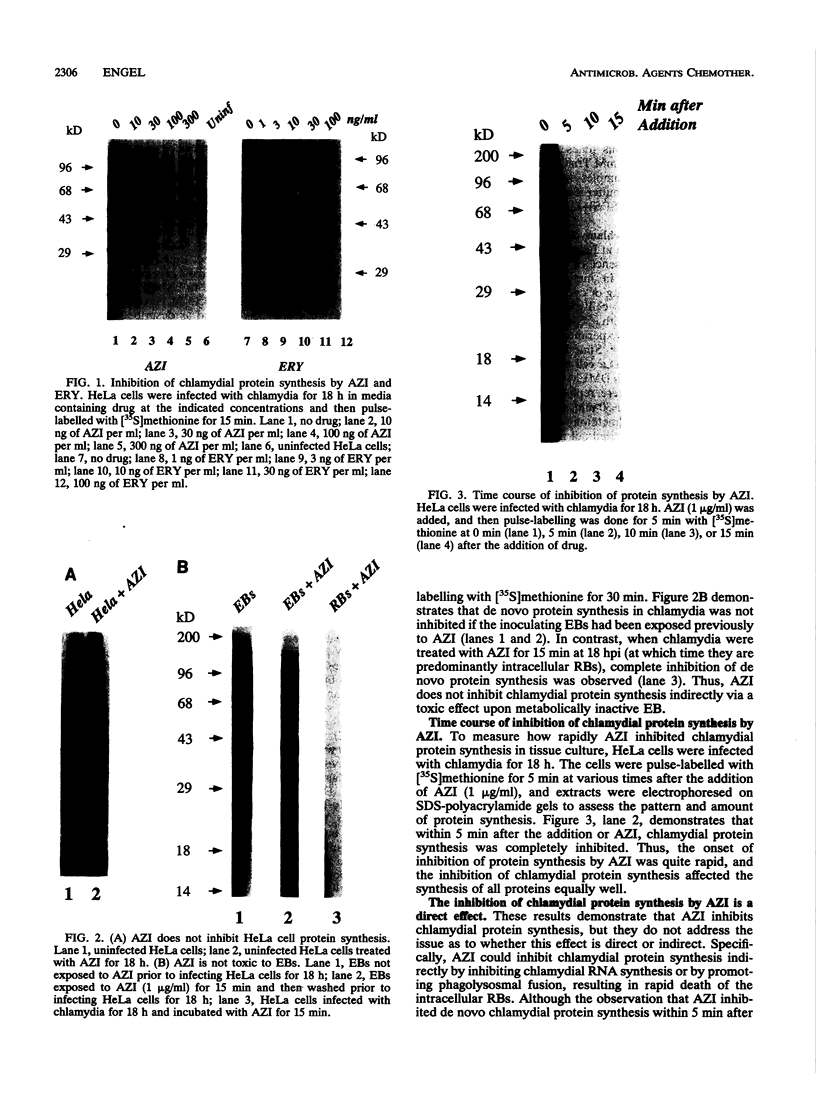

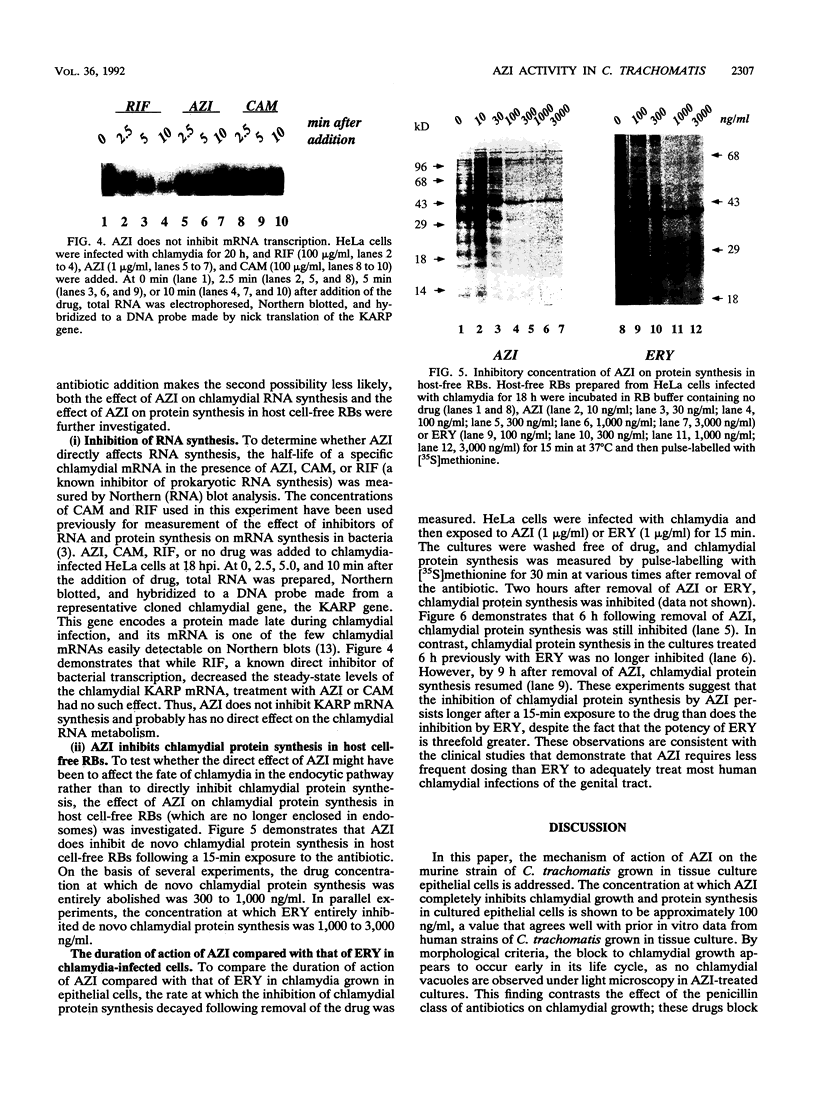

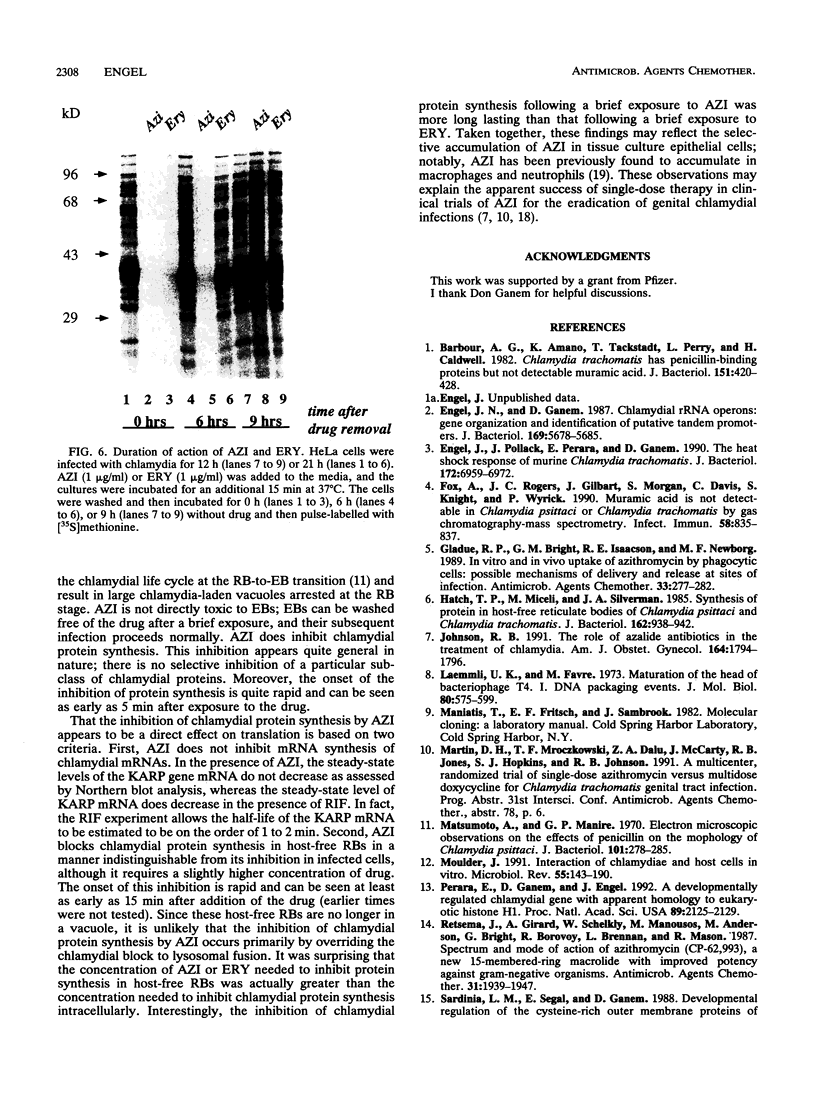

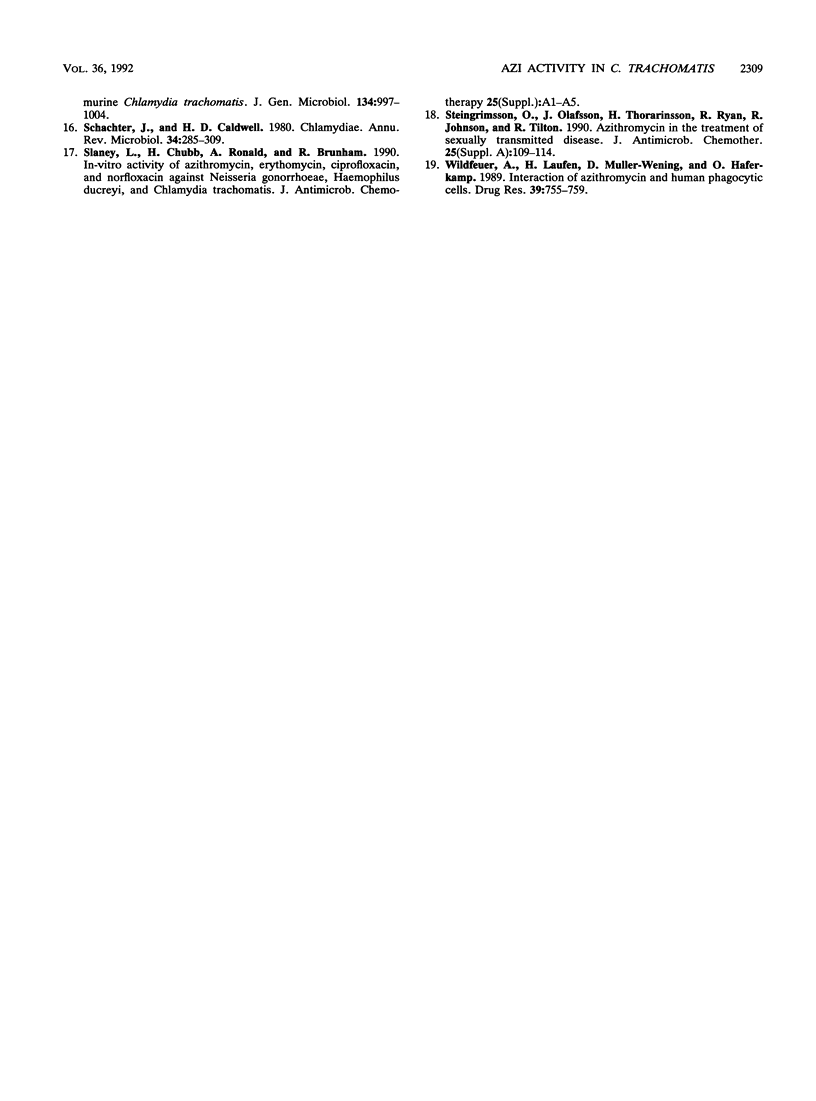

The mechanism of action of azithromycin on the murine strain of Chlamydia trachomatis grown in tissue culture epithelial cells is addressed. Azithromycin at a concentration of 100 ng/ml inhibits chlamydial growth in tissue culture, a value that agrees well with prior in vitro data from human strains of C. trachomatis grown in tissue culture. By morphological criteria, the block to chlamydial growth appears to occur early in its life cycle. Azithromycin is not directly toxic to chlamydial elementary bodies but does inhibit chlamydial protein synthesis in chlamydia-infected cells. This inhibition appears quite general in nature and is rapid. It is further shown that azithromycin does not directly inhibit mRNA synthesis. Azithromycin blocks chlamydial protein synthesis in host cell-free chlamydial reticulate bodies in a manner similar to its inhibition in infected cells, albeit at slightly higher concentrations. The inhibition of chlamydial protein synthesis following a brief exposure to azithromycin is more long lasting than that following a brief exposure to erythromycin.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barbour A. G., Amano K., Hackstadt T., Perry L., Caldwell H. D. Chlamydia trachomatis has penicillin-binding proteins but not detectable muramic acid. J Bacteriol. 1982 Jul;151(1):420–428. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.420-428.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J. N., Ganem D. Chlamydial rRNA operons: gene organization and identification of putative tandem promoters. J Bacteriol. 1987 Dec;169(12):5678–5685. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.12.5678-5685.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J. N., Pollack J., Perara E., Ganem D. Heat shock response of murine Chlamydia trachomatis. J Bacteriol. 1990 Dec;172(12):6959–6972. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6959-6972.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A., Rogers J. C., Gilbart J., Morgan S., Davis C. H., Knight S., Wyrick P. B. Muramic acid is not detectable in Chlamydia psittaci or Chlamydia trachomatis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Infect Immun. 1990 Mar;58(3):835–837. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.3.835-837.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladue R. P., Bright G. M., Isaacson R. E., Newborg M. F. In vitro and in vivo uptake of azithromycin (CP-62,993) by phagocytic cells: possible mechanism of delivery and release at sites of infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989 Mar;33(3):277–282. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch T. P., Miceli M., Silverman J. A. Synthesis of protein in host-free reticulate bodies of Chlamydia psittaci and Chlamydia trachomatis. J Bacteriol. 1985 Jun;162(3):938–942. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.938-942.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. B. The role of azalide antibiotics in the treatment of Chlamydia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Jun;164(6 Pt 2):1794–1796. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K., Favre M. Maturation of the head of bacteriophage T4. I. DNA packaging events. J Mol Biol. 1973 Nov 15;80(4):575–599. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto A., Manire G. P. Electron microscopic observations on the effects of penicillin on the morphology of Chlamydia psittaci. J Bacteriol. 1970 Jan;101(1):278–285. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.1.278-285.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder J. W. Interaction of chlamydiae and host cells in vitro. Microbiol Rev. 1991 Mar;55(1):143–190. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.143-190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perara E., Ganem D., Engel J. N. A developmentally regulated chlamydial gene with apparent homology to eukaryotic histone H1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Mar 15;89(6):2125–2129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retsema J., Girard A., Schelkly W., Manousos M., Anderson M., Bright G., Borovoy R., Brennan L., Mason R. Spectrum and mode of action of azithromycin (CP-62,993), a new 15-membered-ring macrolide with improved potency against gram-negative organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987 Dec;31(12):1939–1947. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.12.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardinia L. M., Segal E., Ganem D. Developmental regulation of the cysteine-rich outer-membrane proteins of murine Chlamydia trachomatis. J Gen Microbiol. 1988 Apr;134(4):997–1004. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-4-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter J., Caldwell H. D. Chlamydiae. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1980;34:285–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.001441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steingrimsson O., Olafsson J. H., Thorarinsson H., Ryan R. W., Johnson R. B., Tilton R. C. Azithromycin in the treatment of sexually transmitted disease. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990 Jan;25 (Suppl A):109–114. doi: 10.1093/jac/25.suppl_a.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildfeuer A., Laufen H., Müller-Wening D., Haferkamp O. Interaction of azithromycin and human phagocytic cells. Uptake of the antibiotic and the effect on the survival of ingested bacteria in phagocytes. Arzneimittelforschung. 1989 Jul;39(7):755–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]