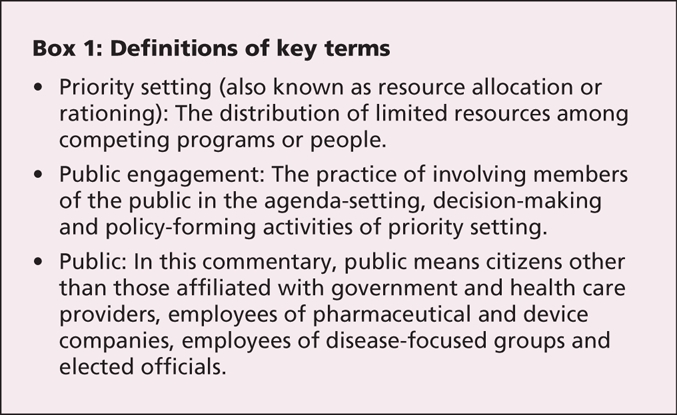

Setting priorities in health care means allocating limited resources so that some programs are supported and others are not (Box 1). For more than a decade, patients, scholars and government reports have asserted that the public should have greater involvement in setting health care priorities,1 but progress on this front in Canada has been slow. We believe the merits of public involvement are compelling and in keeping with a democratic society's desire for an informed, fully engaged citizenry. In this commentary, we review the value of public engagement, address the perceived barriers and suggest ways forward.

Box 1.

The value of public engagement

There are at least 4 reasons for believing that public engagement in setting health care priorities has value. First, because the public funds and uses the health care system, citizens are the most important stakeholders of the health care system. Thus, legitimacy and fairness demand that they be at the priority-setting table.2 Second, greater involvement of the public in policy-making is in keeping with the principles of democracy.3 Third, empowering people to provide input in decisions that affect their lives encourages support for those decisions, which in turn improves the public's trust and confidence in the health care system.4 Fourth, public involvement provides a crucial perspective about the values and priorities of the community, which should lead to higher quality, or at least greater acceptance of, priority-setting decisions.5

Perceived barriers

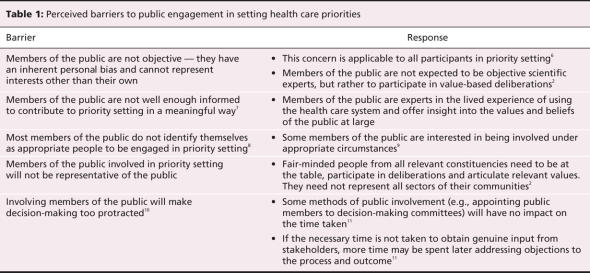

Various barriers have frequently been cited in the literature as reasons not to pursue greater public involvement.6–11 We do not believe these arguments stand up to scrutiny (Table 1).

Table 1

It is frequently stated that members of the public are not objective — they have an inherent personal bias and cannot represent interests other than their own. However, this concern is applicable to all participants currently sitting at the priority-setting table, including health care professionals, administrators and researchers.6 There is no reason to believe that members of the public are less objective than any other type of participant.

Some believe that the public is not well enough informed about the complicated scientific, clinical and administrative aspects of health care to contribute meaningfully to priority setting.7 However, many, if not most, members of the public have real-life experience as users of the health care system and other public services (such as education) and can offer insight into the values and beliefs of the public at large. In genuine public engagement, members of the public are not expected to be scientific experts, but rather to provide their perspectives.2

Some studies have shown that members of the public do not identify themselves as appropriate people to be engaged in priority setting, and they have been labeled “reluctant rationers.”8 However, there is evidence that, if the public is educated about priority-setting decisions and involved under appropriate circumstances, they are willing to accept the inevitability of rationing and want to participate in such decisions.9

Three factors will increase public enthusiasm for involvement in priority setting. First, priority setting is sometimes framed as a technical exercise focusing on evidence-based medicine and cost-effectiveness analysis (e.g., Canadian drug reimbursement committees). Members of the public would be reluctant to participate in such technical discussions for which they are not equipped; it must be made clear that the role of public committee members is to reflect the values and views of the public, not to debate complicated scientific issues, no matter how important they are to the decisions concerned.

Second, too often members of the public who have been “consulted” about policy choices later find that their views have been ignored, which leads them to conclude that their input was not valued, thus causing anger and cynicism.12

Third, members of the public often perceive an intimidating power imbalance between them and clinician and policy-making experts, which can undermine the legitimacy and fairness of the priority-setting process.13 Efforts should be made to minimize these imbalances by setting an appropriate tone during deliberations and including a sufficient number of representatives of the public on decision-making bodies so that they do not feel that their membership is token.13 Even when a commitment to meaningful public involvement is made, often no more than 1 or 2 public members are included; this may be too few for a critical mass and reduces the probability of reflecting the broad views of the public.14

Another barrier to public engagement is concern that those chosen will not be representative of the public. A small number of public representatives on a decision-making committee cannot possibly represent all legitimate public views. However, the same can be said of the ability of a small number of clinicians or health care managers to represent the complexities of their constituencies' views, much less the views of the public. Focusing on representation misframes the issue. What is important is not that those individuals represent all sectors of their communities, but that a diverse group of fair-minded individuals from relevant constituencies come to the table, participate in deliberations and articulate a range of diverse and relevant values.2

Finally, some believe that involving the public will make the decision-making process too protracted.10 However, some methods of public involvement, such as having members of the public on decision-making committees, typically have little impact on the time required to make a decision. Other methods, such as consulting with the public through public forums, may extend the time required. However, sometimes “you save time by taking time.”11 If the necessary time is not taken to obtain genuine input from stakeholders to help ensure pragmatic priority setting, a greater amount of time may be spent later addressing objections to both the process and the outcome.

Ways to increase public engagement

Some formalized public involvement already exists in Canadian health care, notably through public boards of directors of hospitals and other health care delivery organizations, including regional health authorities. However, board members are often chosen because of their fundraising abilities and political connections (both very important attributes), and some spend relatively little time on priority setting, which is usually left to the “experts” within the organization. Evaluation of Canadian advisory committees on health technology assessment has identified opportunities and specific methods to enhance public involvement in such assessment.15 Recently, there have also been some initiatives to increase public involvement in decision-making about drug reimbursement, through appointment of members of the public to the Canadian Expert Drug Advisory Committee and the Ontario Committee to Evaluate Drugs, as well as the creation of an Ontario Citizen's Council focusing on drug policy. Although these efforts are encouraging, they are insufficient.

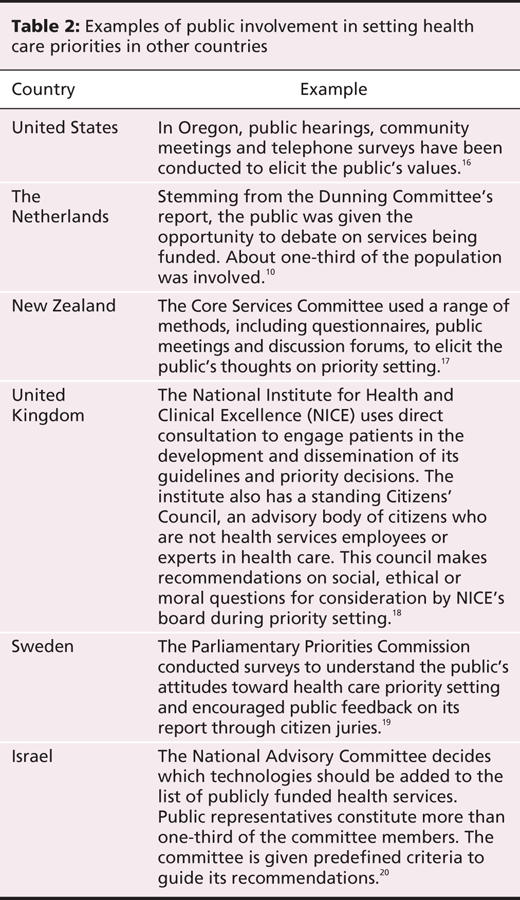

Canadian decision-makers can learn from domestic and international experiences to develop a culture of shared decision-making among policy-makers, expert advisers and members of the public (Table 2).10,16–20 The public can be involved in several ways:

Table 2

as representatives on priority-setting committees

as representatives on executive committees and boards (i.e., hospital boards and regional health authorities)

as members of citizens' councils to provide ongoing advice on specific matters

as participants of surveys, citizens' juries, community meetings, focus groups and the like, to provide feedback on all elements of priority setting.

Of course, not all decisions require this degree of public involvement, and good judgment is needed when deciding when and how to involve the public.

Cautions and realities

Although we believe that the case for more public involvement in setting health care priorities is compelling, little high-quality evidence exists to support that assertion. Because of the complexities of decision-making, such evidence will be hard to produce. However, we do not consider this sufficient reason to delay increasing public involvement in priority setting.

Priority setting often means making difficult choices, and public involvement may not always make these easier or less controversial. This was illustrated by the demonstrations and court action in response to the decision of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence not to reimburse users of cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia,21 despite its involvement of patients and the public in almost all aspects of its decision-making process.

It is important that the request for public input not be overtaken by advocacy groups. In our current system, there is already ample opportunity for disease-oriented groups to engage in political lobbying and, although their voices should be heard in public-engagement exercises, it is the “unaffiliated public” who have the least say in decision-making, with important societal implications.

Poorer members of our society already have worse health and access to health care than wealthier members. It is important that public engagement not involve only people of higher socioeconomic status, as this would exacerbate the disparities.

All deliberations made with public input need not be conducted in public. There can be great value in an appropriately constituted decision-making body meeting in private, but then publicly disclosing the results of its deliberations. This is analogous to the private deliberations of juries in our legal system, which allow them the opportunity to discuss freely, question and argue to arrive at the best decision.

Key points.

The public is the most important stakeholder in the health care system.

Engagement of the public in priority setting in health care is in keeping with the ideals of a democracy.

Members of the public can provide a crucial perspective about the values and priorities of the community, which should lead to higher-quality decisions in priority setting.

Engagement of the public should improve the public's trust and confidence in the health care system.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Duncan Sinclair and Arthur Slutsky for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Rebecca Bruni conducted the majority of the literature research and drafted the manuscript. Andreas Laupacis made substantial contributions to the conceptualization of the paper and critically revised all drafts of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Doug Martin has worked in the arena of public engagement and priority setting for many years, and he originally conceived the manuscript and made substantial contributions to revising all drafts.

This research was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Emerging Team Grant. Rebecca Bruni was supported by a Canada Graduate Scholarship Master's Award from the CIHR. Douglas Martin was supported by a New Investigator Award from the CIHR.

Competing interests: None declared.

Members of the University of Toronto Priority Setting in Health Care Research Group: Rebecca Bruni, University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.; Tony Culyer, Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.; Irfan Dhalla, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Ont.; William K. Evans, Juravinski Cancer Centre at Hamilton Health Sciences and McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont.; Alan Hudson, Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto, Ont.; Andreas Laupacis, Keenan Research Centre at the Li Ka Shing Knowlege Institute, St. Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Ont.; Wendy Levinson, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.; Douglas K. Martin, University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics and the Department of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.; Steve Pearson, US National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC; and Terence Sullivan, Cancer Care Ontario, Toronto, Ont.

Correspondence to: Mrs. Rebecca A. Bruni, University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics, 88 College St. Toronto ON M5G 1L4; rebecca.bruni@utoronto.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.New B, editor. Rationing: talk and action in healthcare. London (UK): Blackwell BMJ Books; 1997.

- 2.Daniels N, Sabin J. Setting limits fairly: Can we learn to share medical resources? New York: Oxford University Press; 2002.

- 3.Goldman J. Millions of voices: a blueprint for engaging the American public in national policy-making. Washington (DC): America Speaks; 2004.

- 4.Traulsen JM, Almarsdóttir AB. Pharmaceutical policy and the lay public. Pharm World Sci 2005;27:273-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Ham C. Rationing in action: priority setting in the NHS: reports from six districts. BMJ 1993;307:435-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Burgess M. What difference does public consultation make in ethics? [Electronic Working Paper series]. Vancouver: W. Maurice Centre for Applied Ethics, University of British Columbia; 2003.

- 7.Knox C, McAlister D. Policy evaluation: incorporating users' views. Public Adm 1995;73:413-36.

- 8.Lomas J. Reluctant rationers: public input to health care priorities. J Health Serv Res Policy 1997;2:103-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kapiriri L, Norheim OF, Heggenhougen K. Public participation in health planning and priority setting at the district level in Uganda. Health Policy Plan 2003; 18: 205-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Lenaghan J. Involving the public in rationing decisions. The experience of citizens juries. Health Policy 1999;49:45-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.O'Hara K. Citizen engagement in the social union. In: Securing the social union. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks; 1998. p. 77-110.

- 12.Turnbull L, Aucoin P. Fostering Canadians' role in public policy: a strategy for institutionalizing public involvement in policy. Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks; 2006.

- 13.Gibson JL, Martin DK, Singer PA. Priority setting in hospitals: fairness, inclusiveness, and the problem of institutional power differences. Soc Sci Med 2005; 61: 2355-62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Martin DK, Abelson J, Singer PA. Participation in health care priority-setting through the eyes of the participants. J Health Serv Res Policy 2002;7:222-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Abelson J, Giacomini M, Lehoux P, et al. Bringing “the public” into health technology assessment and coverage policy decisions: from principles to practice. Health Policy 2007;82:37-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Dixon J, Welch HG. Priority setting: lessons from Oregon. Lancet 1991;337:891-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Edgar W. Rationing health care in New Zealand — how the public has a say. In: Coulter A, Ham C, editors. The global challenge of healthcare rationing. Philadelphia: Open University Press; 2000. p. 175-91.

- 18.Kelson M. The NICE Patient Involvement Unit. Evidence-Based Healthcare Public Health 2005;9:304-7. Available: www.mdconsult.com/das/article/body/87766853-2/jorg=journal&source=&sp=N&sid=0/N/480685/1.html?issn= (accessed 2008 Feb 12).

- 19.Swedish Parliamentary Priorities Commission. Priorities in health care. Stockholm: Ministry of Health and Social Affairs; 1995.

- 20.Shani S, Siebzehner MI, Luxenburg O, et al. Setting priorities for the adoption of health technologies on a national level — the Israeli experience. Health Policy 2000;54:169-85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Dyer C. NICE faces legal challenge over Alzheimer's drug. BMJ 2007;334:654-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]