Abstract

Models and methods of work system design need to be developed and implemented to advance research in and design for patient safety. In this paper we describe how the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model of work system and patient safety, which provides a framework for understanding the structures, processes and outcomes in health care and their relationships, can be used toward these ends. An application of the SEIPS model in one particular care setting (outpatient surgery) is presented and other practical and research applications of the model are described.

Keywords: work system, patient safety, system design, human factors engineering, systems engineering

Most errors and inefficiencies in patient care arise not from the solitary actions of individuals but from conflicting, incomplete, or suboptimal systems of which they are a part and with which they interact. To improve the design of these systems, the US Institute of Medicine (IOM) has proposed the application of engineering concepts and methods—in particular, human factors and systems engineering.1,2,3 Emphasis on system design was promoted in a recent report by the National Academy of Engineering and the IOM: “… it is time to… establish a vigorous new partnership between engineering and health care and hasten a transition to a patient‐centered 21st century health care system”.4 Our research program, the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS, http://www2.fpm.wisc.edu/seips/), originally funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, meets this challenge through a novel integration of human factors and healthcare quality models and proposes the SEIPS model of work system5,6,7 and patient safety.

Patient safety researchers clearly recognize the need for human factors engineering and systems approaches to patient safety research, analysis, and improvement. However, noticeably missing from the patient safety literature are models to guide studies to empirically examine system design in relation to patient safety and medical errors. The model described by Reason,8 often referred to as the “Swiss cheese” model, is probably the most well known system model used within the patient safety community. Vincent et al9 have expanded Reason's model and described seven categories of factors that influence clinical practice, such as organizational and management factors, work environment, team factors, task factors and patient characteristics. The Haddon model, which is used commonly in epidemiology and injury prevention, has been proposed for use in quality and safety.10 It defines three categories of the environment as potential contributors to patient safety: physical (e.g. noise), social (e.g. poor communication), and biological (e.g. patient factors). Our SEIPS model5,6,7 goes further by clearly specifying the system components that can contribute to causes and control of medical errors, incidents and adverse events, showing the nature of the interactions between the components, showing how the design of the components and their interactions can contribute to acceptable or unacceptable processes, and nesting itself in a model familiar to many health care professionals—namely, Donabedian's quality model.11,12

A comparison of the strengths and weaknesses of the SEIPS model, the Reason/Vincent model, and Donabedian's quality model is shown in table 1. The SEIPS model explains how the design of the work system can impact not only the safety of patients but also employee and organizational outcomes. Employee outcomes include safety, health, satisfaction, stress and burnout; organizational outcomes include rates of turnover, injuries and illnesses, and organizational health (profitability).

Table 1 Comparison of the SEIPS model, the Reason/Vincent model, and Donabedian's quality model.

| Model | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| SEIPS model of work system and patient safety | Focus on system design and its impact on processes and outcomes Broad view of processes Description of system, its components and interactions among components Impact on patient safety and employee/organizational outcomes | Descriptive model; no specific guidance as to the critical elements |

| Reason/Vincent model of accidents and adverse events | Focus on etiology of accidents and adverse events Description of contributing factors | No discussion of processes No guidance for system redesign and improvement of patient safety |

| Donabedian's model of quality (structure‐process‐ outcome, SPO) | Description of relationships between structure, processes and outcomes | Narrow description of “structure” Limited description of processes |

In this paper we describe the SEIPS model and its research and practical applications, and propose that this model can be used to help address the systemic problems of patient safety.

SEIPS model of work system and patient safety

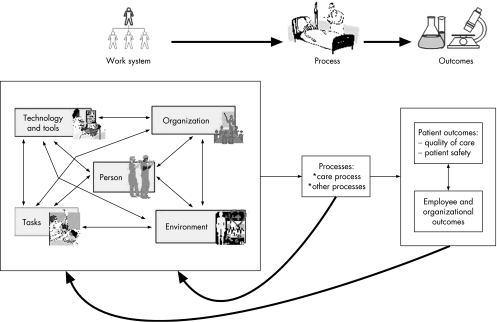

Our systems engineering approach to patient safety is anchored within the industrial engineering subspecialty of human factors. The discipline of human factors emphasizes interactions between people and their environment that contribute to performance, safety and health, and quality of working life, and the goods or services produced.13,14 It is important to characterize these many interactions between people and their environment in a concise and coherent manner to identify points for improvement or intervention. In order to achieve this goal, we use the work system model developed by Carayon and Smith (fig 1).5,6,7 According to the work system model, a person (the person could be a care provider, another employee of a healthcare institution such as a biomedical engineer, a unit clerk, or the patient) performs a range of tasks using various tools and technologies. The performance of these tasks occurs within a certain physical environment and under specific organizational conditions. The five components of the work system (person, tasks, tools and technologies, physical environment, organizational conditions) interact with each other and influence each other. The interactions between the various components “produce” different outcomes: performance, safety and health, and quality of working life.

Figure 1 SEIPS model of work system and patient safety.

Assessing patient safety and designing systems that produce safe patient care can be accomplished by using the SEIPS model that integrates Donabedian's structure‐process‐outcome (SPO) framework and the work system model (fig 1). The structure of an organization (or, more generally, the work system) affects how safely care is provided (the process); and the means of caring for and managing the patient (the process) affects how safe the patient is (outcome). We suggest that the work system model applied to patient safety complements and expands Donabedian's framework. Sainfort et al15 have proposed an earlier adaptation of the work system model and the concept of healthy organizations to health care. Overall, the work system in which care is provided affects both the work and clinical processes, which in turn influence the patient, employee, and organizational outcomes of care. Changes to any aspect of the work system will, depending on how the change or improvement is designed and implemented, either negatively or positively affect the work and clinical processes and the consequent patient, employee, and organizational outcomes. Table 2 displays elements of the various SEIPS model components. This is not an exhaustive list of elements, but should be considered as examples.16 Some of the elements have recently been emphasized—for example, teamwork17,18 which is an element of the organizational component; our SEIPS model does not highlight any single element of the work system.

Table 2 Components and elements of the SEIPS model.

| Components | Elements (examples) | |

|---|---|---|

| Work system or structure | Person | Education, skills and knowledge |

| Motivation and needs | ||

| Physical characteristics | ||

| Psychological characteristics | ||

| Organization | Teamwork | |

| Coordination, collaboration and communication | ||

| Organizational culture and patient safety culture | ||

| Work schedules | ||

| Social relationships | ||

| Supervisory and management style | ||

| Performance evaluation, rewards and incentives | ||

| Technologies and tools | Various information technologies: electronic health record, computerized provider order entry and bar coding medication administration | |

| Medical devices | ||

| Other technologies and tools | ||

| Human factors characteristics of technologies and tools (e.g. usability) | ||

| Tasks | Variety of tasks | |

| Job content, challenge and utilization of skills | ||

| Autonomy, job control and participation | ||

| Job demands (e.g. workload, time pressure, cognitive load, need for attention) | ||

| Environment | Layout | |

| Noise | ||

| Lighting | ||

| Temperature, humidity and air quality | ||

| Work station design | ||

| Process | Care processes and other processes | Care processes |

| Other processes: information flow, purchasing, maintenance, cleaning | ||

| Process improvement activities | ||

| Outcomes | Employee and organizational outcomes | Job satisfaction and other attitudes |

| Job stress and burnout | ||

| Employee safety and health | ||

| Turnover | ||

| Organizational health (e.g. profitability) | ||

| Patient outcomes | Patient safety | |

| Quality of care |

Donabedian's model

Traditional approaches to quality assurance often rely upon SPO measures of quality as conceptualized by Donabedian.19 Donabedian's model has proved valuable in examining the clinical processes and outcomes of care, but it is limited in its recognition of the interactions and interdependencies among system components. Donabedian's model explicitly links the structure and processes of care to subsequent patient outcomes. The SEIPS model builds on this idea by showing how work system design (structure) is linked to patient safety (outcome) through care processes. In Donabedian's model, the structure includes the organizational structure (work system model component = organization); the material resources (work system model components = environment, technology/tools); and the human resources (work system model components = care provider, tasks). Donabedian's two other means of assessing quality include evaluating the process(es) of care (how provider tasks and clinical processes are both organized and performed) and evaluating the outcome(s) of care (assessing the clinical results and impacts of and patient satisfaction with the care provided). Donabedian20 concludes that direct relationships may exist between structure, process and outcome.

In Donabedian's model, however, there is a clear statement that “we must begin … with the performance of physicians and other health care providers”.19 This reflects the fact that most of the focus of the SPO model centres on the providers and their relationship with the processes and outcome(s)—that is, quality is assessed by the way in which care is provided by an individual or care team as well as the outcome of the care. The implication is, therefore, that aspects of the structure may be of lesser consequence. As a result, components of the work system (such as the organization or the environment) and their interdependencies may be overlooked or underemphasized. According to Donabedian's model, poor quality, in turn, results by not following what is defined as the appropriate or correct means of performing a task (poor process). Likewise, a bad outcome is associated with the poor performance of an individual (or a group of individuals). As a result, practitioners tend to associate the SPO model with traditionally punitive efforts and reporting—for example, the credentialing process of medical staff requires reporting performance measures, generally originating from quality assessment activities. Conversely, patient safety activities place greater emphasis on the system in which practitioners work and less on individual performance.21

In contrast to the SPO model, the SEIPS model emphasizes the structure. It proposes the work system model as an expansion of the structure by addressing elements of the work system model such as the physical environment, organizational culture and climate, error reporting and analysis, and work design that are so much a part of the current patient safety focus. The work system model also allows linkage of the various elements of the structure in the SPO model—that is, the organizational structure and material and human resources. The implication is that outcomes (both patient and employee/organizational, as proposed by the SEIPS model) are related and that they also are associated with structure aspects of the SPO model. Battles and colleagues22,23 have made a similar effort at expanding Donabedian's model and have called for increasing attention to the “structure” element.

Our proposed model enriches Donabedian's model in four major ways:

it adds employee and organizational outcomes to the list of important outcomes to consider;

it specifies possible relationships between patient outcomes and employee/organizational outcomes;

it includes other processes besides care processes; and

it proposes a more comprehensive definition of “structure”.

The individual in the work system model

In the SEIPS model the individual is at the centre of the work system. In turn, the work system should be designed to enhance and facilitate performance by the individual and to reduce and minimize the negative consequences on the individual (such as reduced stress) and therefore the organization (for example, improved organizational performance). The individual at the centre of the work system could be any healthcare provider performing patient care‐related tasks or a patient receiving care.

It is important to recognize that a healthcare work system often includes both healthcare providers and the patient being cared for. For instance, if the focus of the work system is on the nurse administering a medication, the individual of the work system would be the nurse. The patient is involved in various components of the nurse's work system. The nurse's task of actually administering the medication involves the patient. The physical environment may involve noise and distractions coming from requests from other patients. If the focus of the work system is on the patient taking a medication, the individual of the work system would be the patient. Nurses and other healthcare providers and staff are involved in various components of the patient's work system. The patient performs the task of taking a medication that has been ordered by a physician and administered by a nurse. Any healthcare work system can therefore involve multiple individuals such as healthcare providers and patients. The design of the work system must meet all of their needs—not just the needs of one individual—for the design to be effective.

The patient in the SEIPS model

It is important to remember that the term “patient safety” includes the “patient”.24 The patient fits in the SEIPS model in different ways. Firstly, if the individual in the work system is a healthcare provider, tasks performed by the individual often involve the patient—for example, surgical tasks. The patient is also involved in patient care processes and is the “recipient” of good or bad outcomes of the care process. From this viewpoint, the patient is an “input” into the SEIPS model. Secondly, the SEIPS model can be applied directly to the patient. The individual in the work system could be the patient who is performing tasks (for example, visiting his/her physician, receiving medications from the pharmacist) using various technologies and tools (for example, email to communicate with the physician, prescription order) in a certain physical environment (such as a clinic or pharmacy) under certain organizational conditions (for example, waiting to see the physician, rushing to get the prescription filled). Using the SEIPS model with the patient at the centre of the work system model can help to identify deficiencies in the healthcare system that can impair the patient's capacity to receive high quality safe care, and therefore contribute to the design of systems and processes for delivering patient centred care.

SEIPS model and the professional model

The individual in the work system can be a physician. Professionals such as physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other licensed healthcare providers are bound by ethical mandates to serve in their clients' best interests.25 The concept of the physician as a professional implies both great responsibility and great respect. This professionally motivated sense of autonomy and responsibility may, in part, explain physician resistance to organizational strategies to change their behavior. However, it has been noted that physician professionalism also fosters a “culture of blame” when things go wrong because, if physicians are responsible for the entire medical process, then they are also exclusively to blame for poor quality care.26 A system redesign approach to changing physician behavior may not only be a more effective approach, but may be better accepted by physicians than traditional organizational efforts to improve quality using incentives.27 For example, system redesign has been employed in anesthesiology to develop devices such as a system of gas connectors that do not allow a gas hose or cylinder to attach to the wrong site. This type of technological advance, in addition to an emphasis on a “culture of safety”, has helped to decrease deaths due to anesthesia.28 These system redesigns support rather than conflict with the physician's role as a professional.

Quality improvement efforts that incorporate system redesign may therefore be more successful in changing physician behavior because they preserve physician professionalism. Redesigning a system to make it “easy to do things right and hard to do things wrong” supports this approach to changing physician behavior. Involvement of physicians in the system redesign process is critical to both the success of the system and to physician acceptance of the new system.26 The SEIPS model, which maintains a sense of job control and participation in the process of organizational change, may improve physician acceptance of, and adherence to, new systems.

Processes in the SEIPS model

Donabedian's model focuses on care process(es)—that is, how care is provided, delivered and managed. The SEIPS model expands the concept of process to include not only care processes but also other processes that support the care process such as maintenance, housekeeping and supply chain management. These other processes need to be designed to support the delivery of safe care. For instance, performance obstacles such as inadequate supplies in isolation rooms may prevent ICU nurses from safely delivering care to critical patients.29 In this example, the supply chain management process does not support the care process.

It is also important to understand that processes are very much influenced by work system design.30 For instance, a care process can be considered as a series of steps or tasks performed by an individual or a team of individuals using various technologies and tools; the care process may involve various locations, therefore different physical environments. The care process is also affected by multiple organizational characteristics such as the need for coordination and collaboration among the healthcare providers involved in the process. In the next section we describe an example of the analysis of the outpatient surgery process applying the work system components.

Balanced work system

The SEIPS model uses the concept of “balance” proposed by Carayon and Smith.5,6 Some negative elements in a work system that are hard to change may be overcome by focusing on some other positive elements. For example, in a care unit where the layout is not optimal for patient care in terms of the visibility of the patients, assigning patients located next to each other to the same nurse may help with individual nurse outcomes (fatigue, stress) as well as patient safety (nurse can monitor the patients continuously). Or the difficulty of not having an adequate number of nursing assistants in the unit may be overcome by strong teamwork and collaboration among nurses.

One element of the work system that has been extensively focused on in health care is the skills and knowledge of the individual healthcare provider. The SEIPS model is useful for understanding that, although the skills and knowledge of an individual healthcare provider are important, it is not sufficient by itself to ensure high quality care and patient safety. The entire work system needs to be well designed for optimal performance. For example, a nurse who has excellent skills and knowledge may not give the highest quality and safest of care to the patient if the equipment she/he needs to use is outdated or the medication that she/he gives to the patient is not available in the unit at the scheduled time. This is an example of a poor balance in the work system where one element (for example, outdated equipment) creates a barrier or obstacle to optimal performance.29 The same individual healthcare provider practicing in two different work systems may demonstrate different performance. For example, a nurse who has a high patient load may provide high quality and safe care and may not feel very tired at the end of the shift because he/she may be receiving help from other nurses (teamwork and support) and may have the right tools and equipment in the unit and the patient room to support her. This is an example of a balanced work system. On the other hand, the same nurse who has the same patient load may not perform well in another work system where she/he does not get much support from peers and does not have the right tools and equipment in the unit. This example shows a lack of balance in the work system.

The challenge of achieving a balanced work system is highlighted in the following example. This example describes a mechanism for reducing physician workload in the selection and insertion of central venous catheters. Traditionally, a physician, assisted by a nurse, places catheters in the central venous system for patient therapy and monitoring. However, with the introduction of peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICCs), this practice has changed. PICCs are inserted by the nurses and/or physicians certified in this procedure. By following patient care policy and procedures for central venous catheter use, an ICU physician determines which type of central catheter should be placed. A PICC line team composed of certified nurses inserts and cares for the patient's PICC line, thus freeing up the physician from this time consuming procedure. However, the PICC line intervention may not decrease the nurse's workload but add to the workload as more and more patients require PICC line insertion rather than central venous catheter insertions.

This example shows the need to focus on the entire work system relevant to the particular care process (PICC line insertion): a narrow focus on the physician work system creates a problem for the nurse work system. As explained above, the design of the work system needs to consider the needs of all the people involved.

Impact of work system and processes on outcomes

Our model emphasizes the linkages between patient outcomes and employee/organizational outcomes. The fact that the SEIPS model explains how the design of a system can impact patients, employees, and the organization has its roots in the theory of healthy work organizations (HWOs). HWOs are organizations that have both good organizational outcomes and a healthy and safe workforce.31,32 A healthcare HWO would also provide high quality safe patient care.15 Some evidence exists that healthcare organizations are not, in fact, healthy organizations. Healthcare workers experience many negative consequences of poor system design such as job dissatisfaction, burnout, intentions to quit, reduced mental health, and injuries.6

Others have also emphasized the important relationship between patient outcomes and employee/organizational outcomes.15,33 Poor employee/organizational outcomes, such as back injuries experienced by nurses, are likely to be related to poor patient outcomes.34 The experience of musculoskeletal pain or discomfort may affect the nurse's psychological and physical resources necessary to perform her job safely. In addition, work system factors are likely to simultaneously contribute to negative employee/organizational outcomes and negative patient outcomes such as medical errors.35 Performance obstacles in the work system can not only affect the healthcare provider's capacity to perform his/her job, but also affect their attitudes toward their organization such as job dissatisfaction and frustration.29

The SEIPS model specifies feedback loops from processes to work system and from outcomes to work system. These feedback loops represent pathways to design or redesign the work system. Poor processes and outcomes can be triggers for system redesign: the need would then arise to identify negative work system elements that affect processes and the quality and safety of care, as well as employee and organizational outcomes.

Application of the SEIPS model to outpatient surgery

In collaboration with our SEIPS partners, we identified outpatient surgery services as the first target for testing the SEIPS model as a guide for patient safety assessment and intervention. We have subsequently applied the SEIPS model to our pilot study of five outpatient surgery centres located in Madison, Wisconsin.36 The goal of the project is to identify elements within outpatient surgery systems and processes where safety threats may exist, and to plan mediating efforts in a manner that is congruent with the context.36 The SEIPS model was used for two purposes: (1) to guide the assessment of systems, processes and outcomes in each outpatient surgery centre for the development of system redesign interventions, and (2) to guide the evaluation of the system redesign interventions (table 3).

Table 3 Application of the SEIPS model to the SEIPS outpatient surgery project.

| Components of SEIPS model | Phase of assessment and determination of system redesign interventions | Evaluation of system redesign interventions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff survey | Shadowing of patients | Review of floor plans | Assessment of position descriptions | Employee questionnaire | Patient survey | |

| Work system | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Processes | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Employee and organizational outcomes | √ | |||||

| Patient outcomes | √ | √ | √ | |||

Assessing work systems, processes, and outcomes of outpatient surgery

In the assessment phase of our study of outpatient surgery we used a variety of methods to understand the work systems, care process, and various outcomes including:

completion by staff of an open ended questionnaire aimed at identifying healthcare professionals' areas of concern regarding quality and patient safety, as well as those aspects of their work system that promote patient safety and a healthy work environment;29,37

“shadowing” of patients undergoing outpatient surgery to better understand the information flow and any shortcomings and strengths associated with the system from a patient's perspective;38

review of floor plans to aid in assessing the physical flow of patients and staff; and

assessment of position descriptions to clarify roles of those providing care.

The first data collection method (staff questionnaire) provides data on components of the work system as well as issues related to the work system and processes perceived by the staff as affecting patient outcomes, in particular quality of care and patient safety.37 The initial staff questionnaire included three questions:

What do you think are the main issues related to quality of patient care and patient safety in your outpatient surgery unit?

Please think of instances in the past year when you feel your performance was challenged or below par due to problems in the OSC [Outpatient Surgery Center] “system”. Please briefly describe any such instance(s) you experienced by explaining the situation and what you think caused it?

Please think of instances in the past year when you feel your performance was exceptional. Please briefly describe any such instance(s) you experienced by explaining the situation and what you think caused it.

Staff responses to the questionnaire can be associated with numerous aspects of the work system.29 Tasks, tools, and organization coincide with an issue repeatedly reported by staff concerning the process of obtaining clinical information on patients in a timely fashion. Here staff conveyed the inherent inefficiencies of tracking down information that should have been previously provided. Likewise, quality and safety issues identified were related to insufficient and potentially inaccurate information then collected because of the last minute nature of these clinical assessments. Staff offered suggestions to remedy this problem through redesign of forms and changes in policy and job design. Staff responses to the questionnaire were also associated with various processes (including care processes) and outcomes. They commented about the low quality of communication with patients regarding preoperative preparation (for example, understanding of instructions) and postoperative recovery (for example, inconsistencies in providers' instructions). They also emphasized coordination issues related to patient information. For instance, unavailability of patient related information sometimes can lead to cancellations of surgeries on the day they are scheduled.

The second data collection method (patient shadowing) records the components of the work system over time to collect data on the patient care process.38 During the shadowing the observer maintained a two dimensional log: (1) listing the chronological sequence of steps the patient underwent and (2) recording observations according to the work system component(s). For example, a patient whose vital signs are being collected during intake by the preoperative nurse may have the following log entries at a given time:

Box 1 SEIPS model for system design

The management of a rural hospital wants to meet the guidelines of the Leapfrog Group and decides to invest in computerized provider order entry (CPOE).

Management soon realizes that, to achieve successful implementation of CPOE, they need to be proactive and redesign their systems and processes. Looking at the SEIPS model, they realize that the CPOE technology will probably interact with existing technologies, tasks, environment, organization, and people (work system), so they begin to make an inventory of the possible interactions.

The CPOE technology will have to be integrated with the existing computerized decision support system, pharmacy information management system, laboratory information management system, radiology information system, billing software, and electronic medical record (technologies and tools). Physicians' task of ordering medications will change, pharmacy transcription may be eliminated, and additional technical support (organization) will likely be required. An informational campaign and training materials for physicians and pharmacists need to be developed (organization). Additional computers (technologies and tools) will need to be purchased for ordering, which means additional space for the computers. From an organizational point of view, because order capture will be enhanced, billing accuracy should improve as well. New policies for physician ordering and pharmacy verification will have to be developed (organization). Various processes will therefore have to be redesigned.

The administration creates task forces to work on all of these design issues before the CPOE is implemented so that their healthcare system and processes are ready.

Task: patient vitals taken.

Environment: patient door open; noisy and distracting interactions between staff in hallway.

Tools/technology: vitals recorded manually in patient's chart.

Organization: nurse conveys that he will most likely not follow the patient throughout her stay.

The review of floor plans provides information on the physical aspects of the work system and their potential impact on processes. In this case the plans provided an understanding of the work flow and offered a greater appreciation for the confidentiality issues identified during the patient shadowing. Likewise, it was easier to understand comments on the staff questionnaire concerning the work space. For instance, concern was expressed by staff regarding the lack of privacy for patients and high noise levels. A review of the floor plans helped the research team further understand the reasons for these concerns.

Box 2 SEIPS model for proactive hazard analysis

A nursing home director, knowing that medication administration errors have become a major concern at many nursing homes, decides to launch a hazard analysis of the medication administration system at her nursing home before her nursing home has a problem.

To decide what information to collect, she refers to the SEIPS model. From the model she understands she will have to collect data about hazards related to all the people involved in the medication administration process as well as the technology, tasks and procedures, organizational policies and culture, and environment related to medication administration. This is far more data than she would have otherwise thought to collect.

Through the data collection it is discovered that nurses are administering on average six medications per patient (task), that nursing home policy only allows them a certain number of minutes for medication passes (organization), and that to follow all nursing home administration protocols would require at least double the amount of time allotted (interaction between organization and task). Because of that, nurses are circumventing the supposed “safety” protocols for administration.

Finally, the assessment of position descriptions provides general information on the work system of the various healthcare professionals. This gave us greater insight concerning the expectations for the various positions as well as how each centre was organized according to the various tasks.

Evaluation of system redesign interventions

Two data collection methods were used to evaluate the various system redesign interventions implemented in the five outpatient surgery centres: a structured employee questionnaire and a patient survey. The employee questionnaire includes questions on several components of the work system, particularly the issues targeted by the redesign interventions (such as communication and coordination).37,39 It also includes questions on employee outcomes (for example, quality of working life such as job satisfaction and stress), as well as staff perceptions of quality and safety of care provided by their outpatient surgery centres. The patient survey focuses on processes (such as medication related information) and patient outcomes (such as symptoms and complications from surgery).40

Using the SEIPS model of work system and patient safety: design and research applications

Because of its emphasis on a systems approach, the SEIPS model can be used both proactively and reactively to improve patient safety by focusing on the design of work systems. It can be used proactively to guide system design and hazard analysis, or reactively to guide patient or employee injury investigations. It can also guide patient safety researchers toward developing research questions and understanding what variables to measure for a particular study. Examples are used to illustrate the case for each in boxes 1–4. For each example, components of the SEIPS model are highlighted in italics.

Box 3 SEIPS model for accident investigation

A major academic teaching hospital has a sentinel event and sets out to conduct a root cause analysis (RCA).

In order to make sure that the RCA team does not jump to conclusions or fall into blaming the individuals at the sharp end, the hospital patient safety officer shows the RCA team the SEIPS model. She explains to the team that the many potential causes of the event may have come from the design of the tasks and procedures, the environment, the technology used, the organizational culture or reward system, or most likely, some interaction among the elements.41

The RCA team then examines all of those factors in order to understand how they each might have contributed to the sentinel event (patient outcome).

Conclusion

The SEIPS model is useful for providing a view of the whole system instead of focusing on only one aspect of the work system and treating that aspect in isolation. It is descriptive, not prescriptive. It does not tell if a change in one factor in the work system leads to any specific employee, organizational or patient outcome. However, it provides a framework on how to think about the different aspects of a work system, their interactions, and possible outcomes. This can be considered as a limitation of the model because it does not provide specific guidance as to the critical elements; but it can also be a strength because the model is generic and adaptable to the particular context or situation.

It is critical to understand how resistance to a systems approach may limit effective implementation of the SEIPS model in practice. In particular, provider resistance may derive from a mismatch between the implications of the work system model and the degree of autonomy expected by providers in their work environment. The professional model assumes that providers have the ultimate authority to define and carry out the core tasks of providing medical care.42 Because the professional status of providers is linked so strongly to their autonomy, they may resist system efforts to manage the process of medical care as infringing on their autonomy and degrading their professional status. Recognizing potential resistance and obtaining strong support from key opinion leaders43 is essential to effective implementation of the SEIPS model.

Box 4 SEIPS model for patient safety research

Research on patient safety is generally concerned with understanding (a) the predictors of safe or unsafe care practices, (b) the predictors of potential or actual patient harm, and (c) testing interventions to improve patient safety.

The SEIPS model can guide researchers in identifying potential predictors by helping them think about all of the relevant factors in the system, as opposed to just focusing on what seems to be relevant (for example, caregiver characteristics or workload).

The SEIPS model can also help intervention researchers. To successfully study an intervention, the intervention must be designed appropriately and the correct indicators of success or failure must be measured. The SEIPS model can help guide the design of the intervention to make sure that the relevant technological, organizational, job, environmental and personnel factors are being considered. Furthermore, the SEIPS model can guide the measurement of success by pointing to changes in the technology, organization, jobs, environment, or personnel that might indicate success or failure. According to the SEIPS model, success or failure needs to be evaluated on both patient outcomes and employee/organizational outcomes.

Key messages

The design of work systems affects patient safety as well as employee and organizational outcomes.

The design of work systems influences processes which, in turn, affect outcomes.

The individual is at the centre of the work system and can be a healthcare provider, a healthcare team, or the patient.

The work system needs to be balanced and to consider the requirements of the various stakeholders involved in the process(es).

Patient outcomes and employee/organizational outcomes are influenced by the work system design. They also influence each other.

We have shown that the SEIPS model can be applied in many different ways to patient safety challenges. Healthcare institutions interested in understanding the relationship between the work system and patient safety may start by answering the following questions:

What are the characteristics of the person(s) performing the tasks or involved in the work?

What tasks are being performed and what are the characteristics of the tasks that may contribute to safe or unsafe patient care?

What in the physical environment can be sources of error or promote safety?

What tools and technologies are being used to perform the tasks and do they increase or decrease the likelihood of untoward events?

What in the organization prevents or allows exposure to hazard? What in the organization promotes or hinders patient safety?

How do the tasks, physical environment, tools/technologies, and organization facilitate or hinder the performance of the individuals involved in the work system?

Footnotes

Funding for this research was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Grant # P20 HS11561‐01.

Competing interests: none.

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Organizational Design and Management Conference, 2003 (Carayon P, Alvarado CJ, Brennan P, et al. Work system and patient safety. In: Luczak H, Zink KJ, eds. Human factors in organizational design and management—VII. Santa Monica, CA: IEA Press, 2003:583–9).

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001 [PubMed]

- 2.Institute of Medicine To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1999

- 3.Institute of Medicine Keeping patients safe: transforming the work environment of nurses. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2004 [PubMed]

- 4.Reid P R, Compton W D, Grossman J H.et alBuilding a better delivery system. A new engineering/health care partnership. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 200515. [PubMed]

- 5.Carayon P, Smith M J. Work organization and ergonomics. Appl Ergon 200031649–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith M J, Carayon‐Sainfort P. A balance theory of job design for stress reduction. Int J Ind Ergon 1989467–79. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith M J, Carayon P. Balance theory of job design. In: Karwowski W, ed. International encyclopedia of ergonomics and human factors. London: Taylor & Francis, 20001181–1184.

- 8.Reason J.Human error. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990

- 9.Vincent C, Taylor‐Adams S, Stanhope N. Framework for analysing risk and safety in clinical medicine. BMJ 19983161154–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brasel K J, Layde P M, Hargarten S. Evaluation of error in medicine: application of a public health model. Acad Emerg Med 200071298–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donabedian A. The quality of medical care. Science 1978200856–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Memorial Fund Q 196640166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson J R. Fundamentals of ergonomics in theory and practice. Appl Ergon 200031557–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandjean E.Fitting the task to the man: an ergonomic approach. London: Taylor & Francis, 1980

- 15.Sainfort F, Karsh B, Booske B C.et al Applying quality improvement principles to achieve healthy work organizations. J Qual Improve 200127469–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carayon P, Alvarado C J, Hundt A S. Work system design in healthcare. In: Carayon P, ed. Handbook of human factors and ergonomics in healthcare and patient safety. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 200761–78.

- 17.Sexton J B, Thomas E J, Helmreich R L. Error, stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: cross sectional surveys. BMJ 2000320745–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morey J C, Simon R, Jay G D.et al Error reduction and performance improvement in the emergency department through formal teamwork training: evaluation results of the MedTeams project. Health Serv Res 2002371553–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 19882601743–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donabedian A.The definition of quality and approaches to its assessment. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press, 1980

- 21.Leape L L, Bates D W, Cullen D J.et al Systems analysis of adverse drug events. JAMA 199527435–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Battles J B, Lilford R. Organizing patient safety research to identify risks and hazards. Qual Saf Health Care 200312(Suppl II)ii2–ii7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coyle Y M, Battles J B. Using antecedents of medical care to develop valid quality of care measures. Int J Qual Health Care 1999115–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennan P F, Safran C. Patient safety. Remember who it's really for. Int J Med Informatics 200473547–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ABIM Foundation ACP‐ASIM Foundation, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med 2002136243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leape L L. Error in medicine. JAMA 19942721851–1857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flynn E A, Barker K N, Pepper G A.et al Comparison of methods for detecting medication errors in 36 hospitals and skilled‐nursing facilities. Am J Health‐System Pharm 200259436–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaba D M. Anaesthesiology as a model for patient safety in health care. BMJ 2000320785–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carayon P, Gurses A P, Hundt A S.et al Performance obstacles and facilitators of healthcare providers. In: Korunka C, Hoffmann P, eds. Change and quality in human service work. Munich: Hampp Publishers, 2005257–276.

- 30.Carayon P, Schultz K, Hundt A S. Righting wrong site surgery. Jt Comm J Quality Saf 200430405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauter S, Lim S Y, Murphy L R. Organizational health: a new paradigm for occupational stress at NIOSH (in Japanese). Japanese J Occup Mental Health 19964248–254. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy L R, Cooper C L. eds. Healthy and productive work: an international perspective. London: Taylor and Francis, 2000

- 33.Kovner C. The impact of staffing and the organization of work on patient outcomes and health care workers in health care organizations. Jt Comm J Qual Improve 200127458–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson A, Baptiste A. Evidence‐based practices for safe patient handling and movement. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 20049 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keijsers G J, Schaufeli W B, LeBlanc P M.et al Performance and burnout in intensive care units. Work & Stress 19959513–527. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carayon P, Hundt A S, Alvarado C J.et al Implementing a systems engineering intervention for improved patient safety—example in outpatient surgery. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks E, et al eds. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005305–321.

- 37.Carayon P, Alvarado C J, Hundt A S.et al Patient safety in outpatient surgery: the viewpoint of the healthcare providers. Ergonomics 200649470–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carayon P, Alvarado C, Hsich Y.et alA macroergonomic approach to patient process analysis: application in outpatient surgery. XVth Triennial Congress of the International Ergonomics Association. Seoul, South Korea 2003

- 39.Carayon P, Alvarado C J, Hundt A S.et al Employee questionnaire survey for assessing patient safety in outpatient surgery. In: Henriksen K, Battles B, Marks E, et al eds. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005461–473. [PubMed]

- 40.Hundt A S, Carayon P, Springman S R.et al Outpatient surgery and patient safety—the voice of the patient. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks E, et al eds. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005445–459.

- 41.Carayon P, Alvarado C, Hundt A S.Reducing workload and increasing patient safety through work and workspace design. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, 2003

- 42.Freidson E.Profession of medicine: a study of the sociology of applied knowledge. New York: Harper & Row, 1970

- 43.Flynn K E, Smith M A, Davis M K. From physician to consumer: the effectiveness of strategies to manage health care utilization. Med Care Res Rev 200259455–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]