Abstract

Polyprenyl phosphates, including undecaprenyl phosphate and dolichyl phosphate, are essential intermediates in several important biochemical pathways including N-linked protein glycosylation in eukaryotes and prokaryotes and prokaryotic cell wall biosynthesis. Herein we describe the evaluation of three potential undecaprenol kinases as agents for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of polyprenyl phosphates. Target enzymes were expressed in crude cell envelope fractions and quantified via the use of luminescent lanthanide binding tags (LBTs). The Streptococcus mutans diacylglycerol kinase (DGK) was shown to be a very useful agent for polyprenol phosphorylation using ATP as the phosphoryl transfer agent. In addition, the S. mutans DGK can be coupled with two Campylobacter jejuni glycosyltransferases involved in N-linked glycosylation, to efficiently biosynthesize the undecaprenyl pyrophosphate-linked disaccharide needed for studies of PglB, the C. jejuni oligosaccharyl transferase.

Keywords: undecaprenol kinase, undecaprenyl phosphate, dolichyl phosphate, LBT

1. Introduction

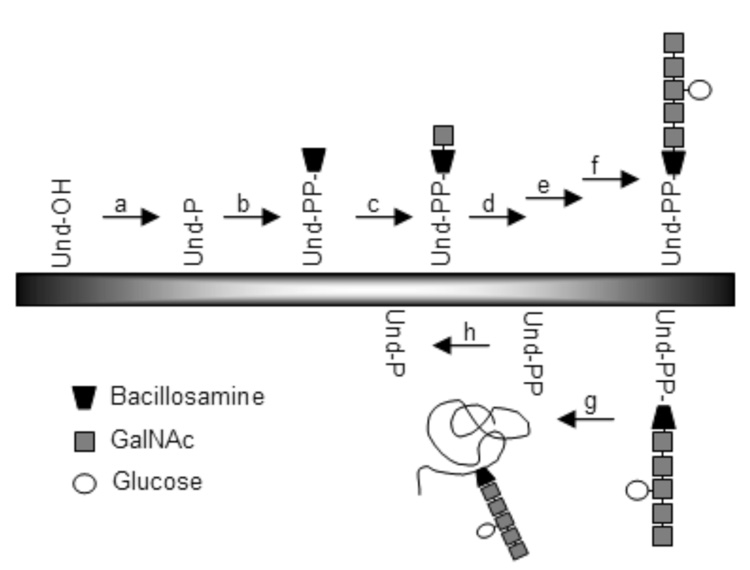

Polyprenyl phosphates, present in the membranes of all organisms, are critical components in several prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways. In prokaryotes, undecaprenyl phosphate (Und-P; 2) is required for peptidoglycan biosynthesis, which is essential to bacterial viability.1 Und-P is also involved in the biosynthesis of lipopolysaccharide in gram-negative bacteria.2 Another essential polyisoprenyl phosphate, Dol-P (Dol-P; 4), is integral in the structure of the oligosaccharide donor that is essential for eukaryotic N-linked protein glycosylation3 and is suggested to play a similar role in the corresponding glycosylation pathways in certain archaea.4 Furthermore, N-linked glycosylation also occurs in some prokaryotes, including the gram-negative pathogenic bacterium Campylobacter jejuni;5 in this case, N-linked glycosylation involves the en bloc transfer of a heptasaccharide from an undecaprenyl pyrophosphate carrier to the amide nitrogen on the asparagine side chain of a protein. Und-P is a critical precursor for in vitro studies of the glycosyltransferases6–8 responsible for undecaprenyl-pyrophosphate heptasaccharide biosynthesis (Fig. 1, b–f) and the bacterial oligosaccharyl transferase9, 10 (Fig. 1, g).

Figure 1.

The C. jejuni N-linked glycosylation pathway. Glycosyltransferases are responsible for the transfer of one or more sugars from the UDP-activated donors (enzyme b–f). Enzymes involved in the pathway: (a) kinase; (b) PglC; (c) PglA; (d) PglJ; (e) PglH; (f) PglI; (g) PglB, the oligosaccharyltransferase; (h) Und-PP phosphatase; Und, undecaprenol; Und-P, undecaprenyl phosphate; Und-PP, undecaprenyl pyrophosphate.

Polyprenyl phosphates are essential for the biochemical characterization of several fundamental cellular processes. Therefore, a convenient and effective method for their preparation is desirable. In general, chemical methods have been relied upon to obtain the desired substrates, since it is difficult to isolate large amounts of the phosphorylated polyprenols from natural sources. For example, Und-P and Dol-P have been chemically synthesized using various approaches.8, 11–15 However, in general chemical methods are not ideal, because the starting isoprenols are expensive and often only available in very limited quantities (µg-mg) and chemical phosphorylation may be impractical on small scales. In addition, it is difficult to quantify the small amounts of polyprenyl phosphates produced in these reactions. At the outset of our studies, we deemed an enzymatic route to polyprenyl phosphates to be an excellent alternative, because it would offer the possibility of a simple, one-step reaction that could be preformed on a variety of scales using ATP as the phosphate donor. This approach would also be useful for preparing radiolabeled polyprenyl phosphates via the use of [γ-32P]-ATP. We first focused on identifying a kinase that could be used to phosphorylate undecaprenol and then examined the utility of the enzyme in the phosphorylation of the dolichol family of polyprenols.

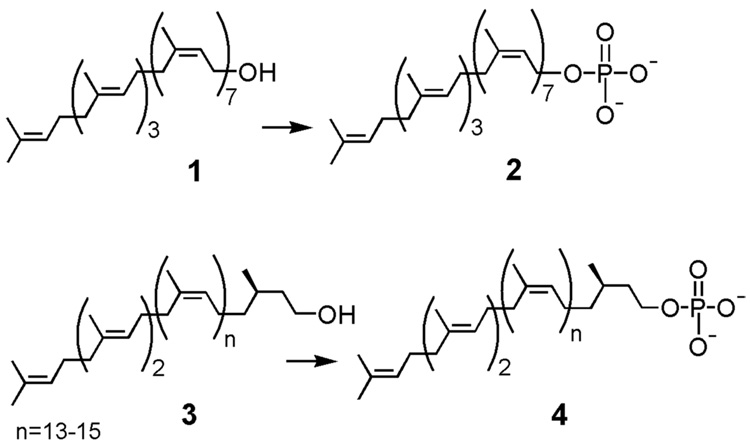

Cellular undecaprenol often exists in membranes as undecaprenyl phosphate or undecaprenyl pyrophosphate. De novo generation of Und-P (2) in vivo is thought to occur by direct phosphorylation of undecaprenol (1) (Fig. 2) and several undecaprenol kinases have been identified.16,17 An alternate source of Und-P includes a salvage pathway in which a phosphatase hydrolyzes the phosphodiester bond of undecaprenyl pyrophosphate (Fig. 1, h).18 Undecaprenyl pyrophosphate is a prevalent component of membranes as it is the isoprene product released after the oligosaccharyl transfer reaction in peptidoglycan biosynthesis in all bacteria and in N-linked glycosylation in C. jejuni (Fig. 1, g). Three enzymes were selected as potential kinases that could be used to phosphorylate undecaprenol. In the 1970’s undecaprenol kinases from Staphylococcus aureus16 and Lactobacillus plantarum17 were identified and biochemically characterized. As this research occurred in the pre-genomic era, the protein and related gene sequences were unknown. However, a more recent study revealed undecaprenol kinase activity in a homolog of diacylglycerol (DGK) kinase from Streptococcus mutans (NP 721953).19 Using NP 721953 as a lead, a bioinformatics search revealed a C. jejuni enzyme (NP 281451) with 36% homology to the S. mutans DGK. Thus, NP 721953 and NP 281451 were selected as two potential candidates for expression and kinase activity screening.

Figure 2.

Undecaprenol (1) and dolichol (3) can be phosphorylated to form undecaprenyl phosphate (2) and dolichyl phosphate (4), respectively. This reaction can be done synthetically or chemoenzymatically by the action of a kinase.

In addition, a further search of the genomic database of C. jejuni was carried out to identify genes with homology to the E. coli BacA (NP 281415), since strains resistant to the undecaprenyl pyrophosphate-binding antibiotic bacitracin were found to have an overexpressed BacA gene.20 It was believed that BacA might encode a polyprenol kinase that compensated for a reduction in the recycling of undecaprenyl pyrophosphate to Und-P by increasing the de novo production of Und-P from undecaprenol.21 However, subsequent in vitro functional assays in E. coli revealed that the E. coli BacA was actually the pyrophosphatase that hydrolyzes the isoprenyl pyrophosphate and regenerates Und-P18 (Figure 1, h). Despite this finding in the E. coli system, the C. jejuni NP 281415 was selected as a third potential target as the enzyme from this organism had not been functionally annotated and because it minimally represented a protein that bound an Und-P derivative.

All three of the enzymes screened for undecaprenol kinase activity were predicted to have multiple membrane domains. Since the purification of membrane-bound proteins is challenging and often results in considerable loss of activity, it is convenient to work with such proteins in native membranes as a cell envelope fraction (CEF). However, it is difficult to quantify the amount of a specific enzyme within a CEF preparation. Quantitative Western blot analysis is one possible approach however, it has many drawbacks; most importantly, it is difficult to generate consistent standards for comparison with the protein of interest. Also, integral membrane proteins, such as those used in these experiments, often behave anomalously in gel electrophoresis experiments. To avoid these problems, an alternative method of enzyme quantification was used, in which the three target enzymes were co-expressed with lanthanide-binding tags (LBTs). LBTs are useful biophysical tools that have been applied in techniques such as X-ray crystallography and NMR.22, 23 Here, the expression of the LBT-protein fusion allows for reliable and reproducible quantification of the amount of LBT-labeled protein present in a crude extract. The unique and tight binding of the LBT to a lanthanide ion, such as Tb3+, results in luminescence at 544 nm. The luminescence can be readily measured and used to estimate the amount of LBT-labeled protein present in the crude cell envelope fraction. The double-LBT (dLBT) developed recently23 binds two Tb3+ ions and was utilized here to determine the relative concentrations of the kinases in the cell envelope fractions.

Finally, to establish the broader utility of kinases identified in the activity screening, we also demonstrated that one of the three enzymes can be used in a coupled system with two Campylobacter jejuni glycosyltransferases involved in N-linked glycosylation to efficiently biosynthesize the undecaprenyl pyrophosphate-linked disaccharide needed for studies of PglB, the C. jejuni oligosaccharyl transferase.

2. Results

2.1 Cloning and expression of three potential undecaprenol kinases

The open reading frames of S. mutans DGK, the C. jejuni DGK homolog, and the C. jejuni BacA homolog were amplified by PCR from the genomic DNA of S. mutans and C. jejuni, respectively. The potential kinases, which all contained multiple predicted transmembrane domains, were expressed heterologously in E. coli BL21 cells and were isolated as cell envelope fractions.

2.2 Lipid specificity of C. jejuni BacA, S. mutans DGK, and C. jejuni DGK

An assay based on radioactivity was performed to evaluate the three potential kinase candidates; the transfer of [32P]-γ-phosphate from the aqueous soluble [γ-32P]-ATP to the organic soluble undecaprenol was monitored. The three enzymes, purified in cell envelope fractions, were initially screened. The S. mutans DGK was the only enzyme that showed levels of polyprenol phosphorylation above the levels in native cell envelope fractions containing a blank pET-24a(+) vector, but both the S. mutans DGK and the C. jejuni DGK showed levels of diacylglycerol phosphorylation above background levels. Assays of the BacA homolog confirmed that it had no phosphorylation activity. BacA cell envelope fractions had turnover levels (30% ± 4.4%, mean ± s.e., n=4) comparable to background controls in which blank cell envelope fractions were assayed with undecaprenol (28% ± 1.4%, mean ± s.e., n=4) and in which BacA cell envelope fractions were assayed without undecaprenol (27% ± 1.7%, mean ± s.e., n=4).

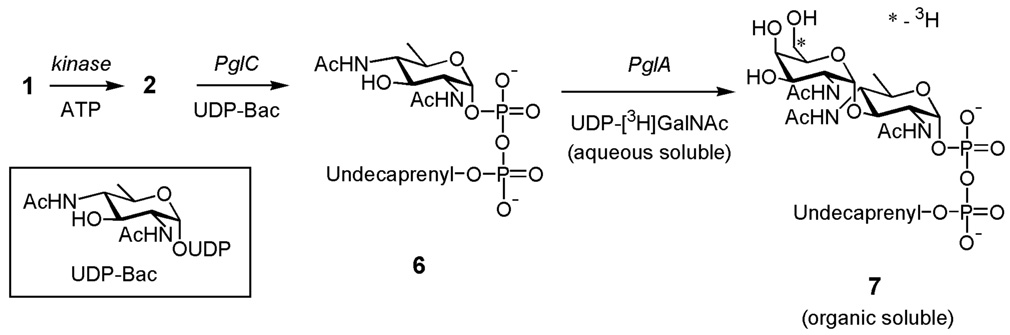

In order to further define the lipid specificities of S. mutans DGK and C. jejuni DGK, it was necessary to purify the enzymes from the native membranes to reduce the high background phosphorylation caused by native membrane-bound E. coli kinases. Both enzymes were purified using Ni-NTA chromatography and assayed immediately with undecaprenol (1), dolichol (3), or diacylglycerol (5). The results of these assays (Table 1) suggested that the S. mutans DGK effectively phosphorylates both undecaprenol and dolichol and that both the S. mutans and C. jejuni DGKs phosphorylate diacylglycerol with a lower efficiency. Diacylglycerol phosphorylation yields may be improved by optimizing the reaction,24 but this was not attempted.

Table 1.

Specificity of S. mutans DGK and C. jejuni DGK for undecaprenol, diacylglycerol, and dolichol. To correct for background transfer of [32P]-phosphate to the organic layer in the absence of lipid, a control reaction was performed in the absence of lipid substrate.

| Lipid component | % turnover with S. mutans DGKa | % turnover with C. jejuni DGKa |

|---|---|---|

| No lipid | 17 ± 1.8 | 10 ± 2.3 |

| Undecaprenol | 56 ± 3.4 | 10 ± 1.7 |

| Diacylglycerol | 32 ± 4.5 | 24 ± 2.6 |

| Dolichol | 55 ± 2.9 | 12 ± 2.9 |

Values reported reflect mean ± s.e., n=4.

The identity of the products generated by the S. mutans DGK was confirmed by isolation of the [32P]-phosphorylated product using normal-phase HPLC chromatography. Comparison by TLC confirmed that the products isolated from the kinase reaction were identical to chemically synthesized Und-P and Dol-P.

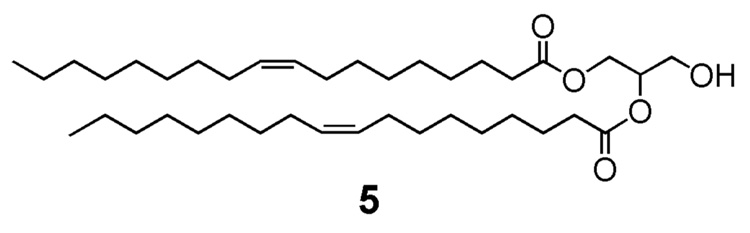

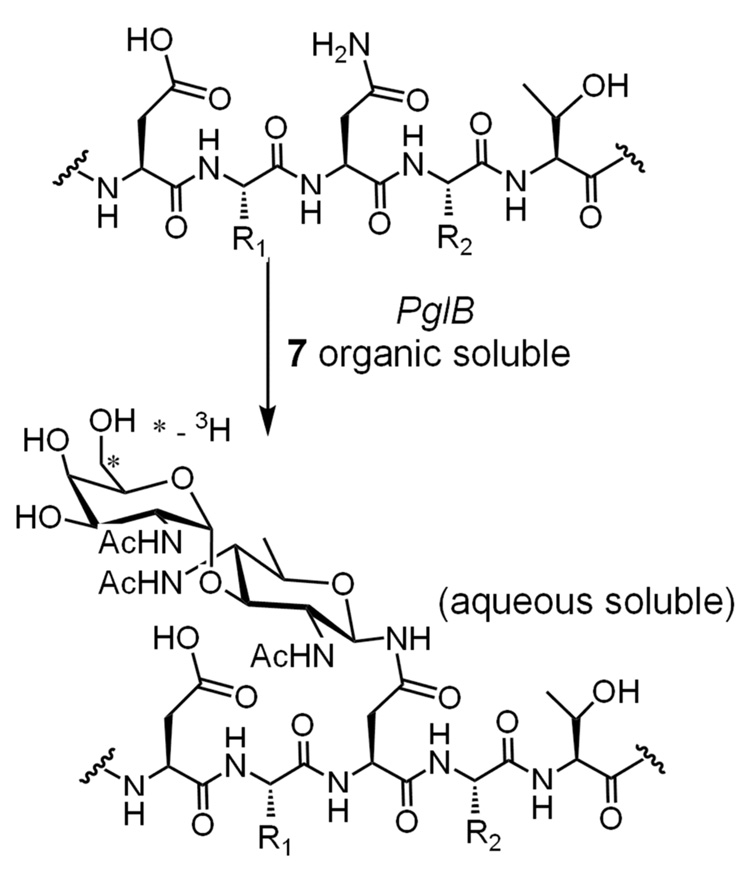

2.3 Development of a one-pot enzymatic route to undecaprenyl pyrophosphate disaccharide

Previously, radiolabeled undecaprenyl pyrophosphate disaccharide (6) had been generated by combining synthetically prepared Und-Ps with the first two glycosyltransferases in the C. jejuni pathway, PglC and PglA (Fig. 3). PglC is responsible for the transfer of 1-phospho-2,4-diacetamido bacillosamine (Bac) from UDP-Bac to give 6.7 The second enzyme in the pathway is PglA, which catalyzes the transfer of N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) from UDP-GalNAc to form the product 7.6 Formation of the product, undecaprenyl pyrophosphate-linked Bac-GalNAc (7), was detected by monitoring transfer of the radiolabeled [6-3H]-GalNAc from the aqueous phase to the organic phase.

Figure 3.

An enzymatic reaction scheme showing the synthesis of undecaprenyl pyrophosphate-linked disaccharide (7).

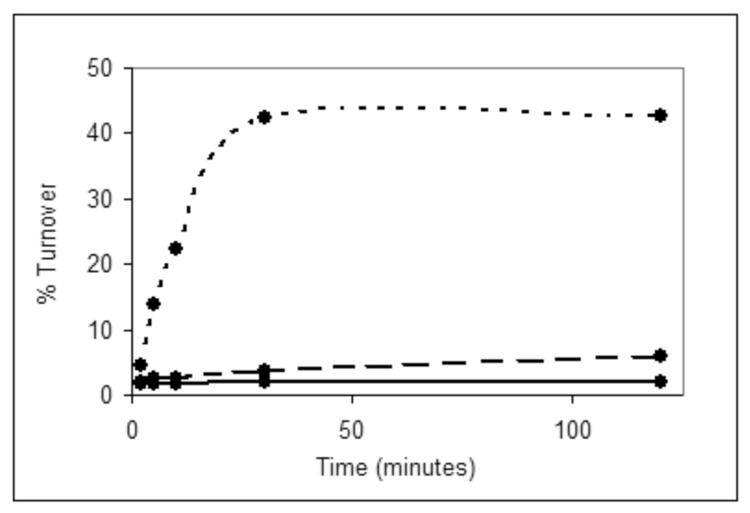

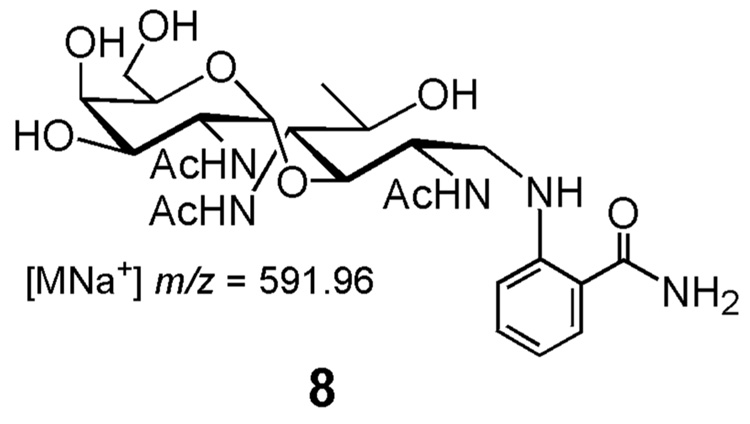

As an alternative to this method, a coupled reaction was developed in which undecaprenyl pyrophosphate-linked disaccharide was generated in a one-pot reaction starting from undecaprenol, ATP, and the UDP-sugars using the kinase, PglC and PglA. In an initial attempt, the reaction with S. mutans DGK showed activity (~41% yield). Interestingly, the C. jejuni DGK produced some tritiated product (7%) at an amount higher than the background turnover (3%) present in the blank cell envelope fractions (Fig. 4). This is in contrast to the [32P]-ATP experiments in which the C. jejuni DGK had no phosphorylation activity. BacA, however, showed no more turnover than the control reaction confirming that it has no discernable phosphorylation activity under these assay conditions (data not shown). The identity of the radiolabeled disaccharide product was confirmed as previously described using fluorescence-based HPLC and MALDI MS.6 For these analyses, the glycan was cleaved from the isoprenyl pyrophosphate under acidic conditions and labeled with 2-aminobenzamide via reductive amination. The fluorophore-labeled disaccharide (8) was separated via normal phase analytical HPLC column and subjected to MALDI MS, which confirmed the identity of the product.

Figure 4.

Time course of assay in which the kinase candidates are coupled to PglC and PglA. Dotted line, S. mutans DGK; dashed line, C. jejuni DGK; solid line, blank cell envelope fraction.

2.4 Optimization of disaccharide synthesis conditions

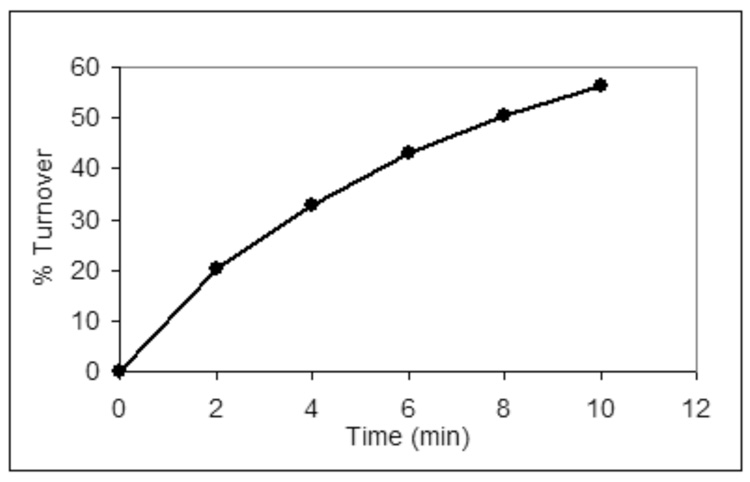

The reaction conditions were optimized to obtain the highest yield of radiolabeled undecaprenyl pyrophosphate disaccharide. To identify the lowest specific activity (i.e. highest substrate concentration) that would maintain high turnover (~70%) of the radiolabeled UDP-GalNAc, the amount of radioactivity in each reaction (0.015 µCi) remained constant, but the specific activity of the UDP-[3H]GalNAc added was varied. As seen in Table 2, high turnover of labeled UDP-GalNAc was seen at specific activities of 30 mCi/mmol or more for S. mutans DGK. The efficiency of C. jejuni DGK dropped substantially as the amount of sugar substrate increased; the only reaction that proceeded with high turnover contained the highest specific activity substrate. Attempts to increase the turnover by allowing the reaction to proceed more than two hours or adding more kinase were unsuccessful. The reaction can be scaled-up to produce 3.8 nmoles (0.3 µCi/nmol) of radiolabeled substrate, which is enough substrate to perform ~50 PglB assays (Fig. 5); PglB is the C. jejuni oligosaccharyl transferase.

Table 2.

Percent turnover of C. jejuni DGK and S. mutans DGK in the synthesis of undecaprenyl pyrophosphate [3H]-disaccharide with UDP-GalNAc at varying specific activities.

| Specific activity of UDP-[3H]GalNAc in mCi/mmol | C. jejuni DGK | S. mutans DGK |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 62 | 67 |

| 300 | 20 | 70 |

| 30 | 5 | 67 |

| 3 | 3 | 24 |

| 0.3 | 4 | 23 |

Figure 5.

A PglB assay scheme showing transfer of the radiolabeled disaccharide from the isoprenyl pyrophosphate carrier onto a peptide.

2.5 Use of undecaprenyl pyrophosphate disaccharide to assay PglB

The radiolabeled undecaprenyl pyrophosphate-linked disaccharide (7) produced in the coupled enzymatic reaction is essential in studies of the C. jejuni oligosaccharyl transferase. A PglB activity assay (Fig. 5) monitors transfer of the radiolabeled disaccharide from the organic soluble polyisoprenol derivative to a peptide in the aqueous layer containing the required sequon for bacterial N-linked glycosylation, DXNXT/S.10 The disaccharide is a sufficient determinant for transfer to peptide substrates by PglB, which in vivo transfers a heptasaccharide from the isoprenyl carrier.9 This type of assay has been used extensively to determine the peptide specificity of PglB10 as well as to screen for potential inhibitors. An assay of PglB using the radiolabeled undecaprenyl pyrophosphate disaccharide and an optimized peptide as substrates is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

A time course of a PglB reaction in which radiolabeled undecaprenyl pyrophosphate disaccharide is used as a substrate.

2.6 Quantification of kinases by use of a dLBT

In the comparative analysis, the C. jejuni DGK appeared to phosphorylate undecaprenol when coupled to PglC and PglA, although not with the robust activity shown by the S. mutans DGK (Fig. 4). To establish whether the difference in turnover levels was caused by differing expression levels, it was necessary to determine the kinase concentrations in the cell envelope fractions. To do this, the two DGKs were expressed with lanthanide-binding tags fused to the N-termini of the enzymes. The dLBT-fused kinases were expressed and isolated in cell envelope fractions. Coupled reactions with PglC and PglA showed that the amount of turnover was not affected by the presence of the dLBT on the kinase. The turnover seen after two hours was reproducibly similar for the tagged and untagged versions of the DGKs (Table 3). From the dLBT luminescence analysis, it was determined that the C. jejuni DGK (10 µM) was present in a five-fold excess over the S. mutans DGK (2 µM).

Table 3.

Results from studies of dLBT-kinase activity and luminescence.

| turnover in disaccharide reaction | Protein present in reaction (µg) | Cell envelope fraction concentration (µM) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. jejuni DGK | 6% | ||

| S. mutans DGK | 61% | ||

| dLBT-C. jejuni DGK | 17% | 3.3 | 10 |

| dLBT-S. mutans DGK | 59% | 0.7 | 2 |

3. Discussion

We have demonstrated that the S. mutans DGK can be used to rapidly synthesize polyisoprenyl phosphates; this method is straightforward and avoids a labor-intensive chemical phosphorylation reaction and purification process. With the addition of an HPLC purification step, pure polyisoprenyl phosphates can be synthesized on a small scale (10–100 nmoles) in a matter of hours. In addition, the kinase maintains activity in the presence of other enzymes and can be coupled to C. jejuni glycosyltransferases to produce other complex isoprenyl phosphate-linked substrates such as undecaprenyl pyrophosphate-linked disaccharide (6). The utility of the kinase undoubtedly expands beyond the C. jejuni N-linked glycosylation pathway; in all likelihood, the kinase can be coupled to similar glycosyltransferases from both prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways.

While S. mutans DGK phosphorylated both dolichol and undecaprenol in high yields, the homologous DGK in C. jejuni showed no turnover in reactions containing only the kinase and only small amounts of turnover in the presence of other enzymes. It is likely that the consumption of Und-P by the subsequent glycosyltransferases drives the reaction of C. jejuni DGK with undecaprenol, even though undecaprenol is not the preferred substrate. This could explain the observation that C. jejuni DGK shows enhanced activity towards undecaprenol in the presence of coupling enzymes.

The results of the dLBT quantification of S. mutans kinase and C. jejuni DGK also provide some insight into the different turnover levels. The higher concentration of C. jejuni DGK (10 µM versus 2 µM for S. mutans DGK) suggests that the enhanced activity of S. mutans DGK is intrinsic to the enzyme and is not due to an excess of enzyme. Also, it is probable that the in vivo substrate of C. jejuni DGK is not undecaprenol, but rather is diacylglycerol as suggested by protein homology with the E. coli DGK and the lipid specificity assays. In addition, these results are consistent with recent work that characterizes a DGK homolog in Bacillus subtilis that also exhibits undecaprenol kinase activity.25 It was noted that the bacterial species identified with undecaprenol kinases, like S. mutans,19 B. subtilis,25 S. aureus,16 and L. plantarum,17 are gram-positive bacteria, whereas the DGK in the gram-negative bacterium E. coli26 does not phosphorylate undecaprenol in vitro. Sequence analysis also revealed significant differences between the DGKs from gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. As C. jejuni is also a gram-negative bacterium, its lack of a DGK-like undecaprenol kinase is not surprising and is consistent with the hypothesis that gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria have developed different mechanisms of isoprene recycling.

4. Conclusion

In summary, the S. mutans DGK has been used to prepare polyprenyl phosphates, including undecaprenyl phosphate and dolichyl phosphate, from the unmodified polyprenols using ATP as the phosphoryl donor. Thus, this kinase can be used to generate the prenyl phosphate substrates needed for in vitro biochemical studies of peptidoglycan synthesis in bacteria and N-linked glycoysylation in all domains of life. Specifically, the kinase has been used here in conjunction with enzymes from the bacterial N-linked glycosylation pathway in C. jejuni to efficiently generate radiolabeled undecaprenyl pyrophosphate-linked disaccharide needed to probe the function of PglB, the oligosaccharyl transferase. It is probable that the kinase could be coupled successfully to glycosyltransferases from prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathways. In addition, dLBT-kinase fusion proteins were expressed and partially purified as cell envelope fractions and the unique luminescence of the interaction of Tb3+ with the dLBT was used to quantify the amount of protein present in the crude fraction. S. mutans DGK is an extremely useful and rapid tool for the synthesis of small, highly quantifiable amounts of polyprenyl phosphates.

5. Experimental

5.1 Materials

The genomic DNA of S. mutans (25175D) and C. jejuni (700819D-5) were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection. The radiolabeled substrates were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. The UDP-bacillosamine was prepared as previously described27 and the UDP-GalNAc was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The pure solvent upper phase (PSUP) solvent used in the enzyme assays was prepared by mixing 235 ml of H2O containing 1.83 g of KCl with 15 ml CHCl3 and 240 ml MeOH. The fluorophore-labeled disaccharide was separated on a normal-phase GlykoSepN HPLC column purchased from ProZyme. The isoprenol derivatives were separated on a normal-phase Varian Microsorb HPLC column. A Fluoromax 2 instrument from Jobin Yvon Horiba was used to measure the LBT luminescence. A LS6500 Beckman Scintillation Counter was used to determine the radioactivity present in the assay samples.

5.2 Cloning of kinase genes into expression vector

C. jejuni BacA and C. jejuni DGK were cloned from C. jejuni genomic DNA (ATCC 700819) using the polymerase chain reaction. Primers for both proteins inserted a BamH I restriction site at the N-terminus (CGCGGATCCATGGAAAATTTATATGCTTTAATACTTGG for BacA and CGCGGATCCATGAAGCCTAAATATCATTTTTTAAATAACG for DGK) and an Xho I restriction site at the C-terminus (CGGCTCGAGTAGCTTAAATTCACTTCCAGCATTTAAAATC for BacA and CGGCTCGAGATGAAAAAGCAAAAACCAAATTTTTGG for DGK). S. mutans dgk was cloned from S. mutans genomic DNA (ATCC 25175D) using PCR. Similar primers inserted a BamH I site at the N-terminus (CGCGGATCCATGCCTATGGACTTAAGAGATA-ATAAGC) and an Xho I site at the C-terminus (CGGCTCGAGATGAAAAAGCAAAAACCAAATT-TTTGG). The genes were inserted into a pET-24a(+) expression vector (Novagen), which contains a T7 tag at the N-terminus and a His6 tag at the C-terminus.

5.3 Expression of enzymes in E. coli BL21 cells

S. mutans DGK and C. jejuni BacA were expressed in E. coli BL21 Gold cells and C. jejuni DGK was expressed in E. coli BL21 Codon Plus-RIL cells. A liter of Luria-Bertana Broth was inoculated with 5 ml of an overnight starter culture and incubated with shaking at 37°C. When the OD600 of S. mutans DGK and C. jejuni DGK reached ~0.4 AU, the cultures were cooled to 16°C. At 0.6 AU, the cultures were induced with 1 mM iso-propyl β-D-thiogalactoside and incubated with shaking for ~20 hours at 16°C. The procedure was similar for C. jejuni BacA, with the exception that the cells were not cooled prior to induction and were incubated at 37°C overnight. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and pellets were stored at −80°C.

5.4 Isolation of kinases in cell envelope fractions

The kinases were isolated in cell envelope fractions. The frozen cell pellets were thawed into 40 ml of buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) per liter of cells and lysed by sonication. A low speed spin (45 minutes, 5,697 × g) removed most of the cellular debris; it was followed by high speed spin (65 minutes, 142,414 × g) to pellet the cell envelope fraction. The pellet was homogenized in 0.5 ml of 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0 per gram of cell pellet and aliquoted into smaller fractions for storage at −80°C.

5.5 Assay of kinases with 32ATP

To a tube containing 13 nmoles of dried lipid, 3 µl dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 7 µl 7% Triton X-100 were added. The tube was vortexed and sonicated for several minutes to ensure solubilization of the lipid. To the same tube, 5 µM ATP (~4.5 mCi/mmol), 40 µl of purified enzyme or 10 µl of crude enzyme, 30 mM Tris-Acetate buffer pH 8.0, 50 mM MgCl2, and dH2O were added to a total volume of 100 µl. The reaction was initiated with ATP and generally quenched after 1 hour into 1 ml of 2:1 CHCl3:MeOH and extracted with PSUP (3x, 400µl). The organic layer was dried under nitrogen gas and prepared for scintillation counting by addition of 200 µl of Solvable and 5 ml of Formula 989 (Perkin-Elmer) with vortexing. After waiting 60 minutes for the decay of chemiluminescence, samples were counted for 1–5 minutes.

5.6 Purification of kinases from cell envelope fraction

To purify the kinases from the cell envelope fraction, 50 µl of sample were incubated with 5% Triton X-100 for one hour at 4°C. Then the samples were spun at 16,110 × g in a tabletop microcentrifuge. The resultant supernatant was incubated with 100 µl Ni-NTA resin for 1 hour. The resin was placed in a 0.2 µm filter in a microcentrifuge tube for the subsequent wash and elution steps. The resin was washed twice with 250 µl of buffer containing 50 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.0 and twice with 250 µl of the same buffer with an additional 45 mM imidazole; each wash was centrifuged for 45 s at 1306 × g. The protein was eluted in 200 µl of 50 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.0 with 300 mM imidazole. Enzymes were assayed immediately following the elution step.

5.7 Purification of phosphorylated isoprenols by normal phase HPLC

The phosphorylated isoprenols were separated on a normal phase analytical HPLC column using 4:1 CH3Cl: MeOH (solvent A) and 10:10:3 CH3Cl:MeOH:H2O, 2M ammonium acetate (solvent B). A gradient of 50% to 30% of solvent A over 20 minutes was used at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Fractions of 0.5 ml were collected and were subjected to scintillation counting to detect the radiolabeled isoprenol derivatives. TLC conditions used for Und-P were 65:25:4 CHCl3:MeOH:H2O.

5.8 Synthesis of radiolabeled undecaprenyl pyrophosphate disaccharide

To synthesize the desired undecaprenyl pyrophosphate Bac-[3H]GalNAc, undecaprenol (20 µg, 26 nmol) in hexanes was measured into a microcentrifuge tube and the solvent removed by evaporation. After adding DMSO (6 µL), followed by 1% Triton X-100 to solubilize the isoprenol, 50 mM MgCl2, 30 mM Tris-Acetate, pH 8.5, S. mutans kinase CEF (50 µL), PglA (purified to ~1 mg/ml, 20 uL), PglC CEF (20 uL), and dH2O were combined for a final reaction volume of 200 µL. In a separate tube, 10 mM ATP, 2 mM UDP-Bac, 50 µM UDP-GalNAc (150 mCi/mmol) were mixed, and the reaction was initiated by the addition of the substrate mixture to the enzyme. The reaction was stirred every 30 minutes for 2 hrs, then quenched through the addition of 2:1 CHCl3:MeOH (1.3 mL). The aqueous layer was removed, and the organic layer extracted with PSUP (3x, 300 µL).

5.9 Quantification of the dLBT-kinase in a cell envelope fraction using luminescence

The amount of dLBT-tagged protein present in a sample can be determined by measuring the luminescence of the sample incubated with Tb3+ under denaturing conditions. A Fluoromax 2 instrument (Jobin Yvon Horiba) was used to obtain the luminescence emission spectra as previously described.28 The samples were prepared by diluting the cell envelope fraction to a total of 2.99 ml of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride. A 40-fold dilution minimum was maintained to ensure complete denaturation of the protein and availability of the dLBT for Tb3+ binding. The luminescence was measured by integrating the area under the Tb3+ emission peak at 544 nm. Measurements were recorded before and after the addition of 10 µl of 1 mM Tb3+ and for subsequent calculations to obtain the background luminescence.

A purified dLBT-ubiquitin construct was used as a standard to determine the amount of luminescence emitted by a known amount of dLBT. The concentration of the dLBT-ubiquitin was determined using UV spectroscopy (ε280 = 15590 M−1cm−1). A linear standard graph was prepared for a range of dLBT-ubiquitin concentrations from 50 nM to 2 µM. The luminescence of the dLBT-kinases was recorded and compared to the standards to approximate the amount of kinase present.

6. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grants from NIH (GM-68692 and GM-39334). The authors acknowledge Dr. N. Olivier for guidance on the project and his critical reading of the manuscript. Also, the authors would like to thank Dr. M. Sainlos for obtaining the MALDI MS data and Dr. J. Troutman for his assistance in the isoprene substrate HPLC purification. Finally, the authors are grateful to L. Martin for sharing his dLBT-ubiquitin protein as well as his extensive LBT-related knowledge.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Higashi Y, Strominger JL, Sweeley CC. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:3697–3702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Troy FA, Vijay IK, Tesche N. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:156–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendrickson TL, Imperiali B. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9444–9450. doi: 10.1021/bi00029a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lechner J, Wieland F, Sumper M. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:860–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szymanski CM, Wren BW. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:225–237. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glover KJ, Weerapana E, Imperiali B. Proc. Natl. Acad. U.S.A. 2005;102:14255–14259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507311102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glover KJ, Weerapana E, Chen MM, Imperiali B. Biochemistry. 2006;45:5343–5350. doi: 10.1021/bi0602056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weerapana E, Glover KJ, Chen MM, Imperiali B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13766–13767. doi: 10.1021/ja054265v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glover KJ, Weerapana E, Numao S, Imperiali B. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen MM, Glover KJ, Imperiali B. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5579–5585. doi: 10.1021/bi602633n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ye XY, Lo MC, Brunner L, Walker D, Kahne D, Walker S. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3155–3156. doi: 10.1021/ja010028q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branch CL, Burton G, Moss SF. Synth. Commun. 1999;29:2639–2644. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren CD, Jeanloz RW. Methods Enzymol. 1978;50:122–137. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(78)50010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki S, Mori F, Takigawa T, Ibata K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:5103–5306. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imperiali B, Zimmerman JW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:5343–5344. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higashi Y, Siewert G, Strominger JL. J. Biol. Chem. 1970;245:3683–3690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalin JR, Allen CM., Jr Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1979;574:112–122. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(79)90090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Ghachi M, Bouhss A, Blanot D, Mengin-Lecreulx D. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30106–30113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lis M, Kuramitsu HK. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:1938–1943. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.4.1938-1943.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cain BD, Norton PJ, Eubanks W, Nick HS, Allen CM. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:3784–3789. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3784-3789.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siewert G, Strominger JL. Proc. Natl. Acad. U.S.A. 1967;57:767–773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.3.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silvaggi NR, Martin LJ, Schwalbe H, Imperiali B, Allen KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7114–7120. doi: 10.1021/ja070481n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin LJ, Hahnke MJ, Nitz M, Wohnert J, Silvaggi NR, Allen KN, Schwalbe H, Imperiali B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7106–7113. doi: 10.1021/ja070480v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh JP, Bell RM. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:6239–6247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jerga A, Lu YJ, Schujman GE, de Mendoza D, Rock CO. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:21738–21745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohnenberger E, Sandermann H., Jr Eur. J. Biochem. 1979;94:401–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb12907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olivier NB, Chen MM, Behr JR, Imperiali B. Biochemistry. 2006;45:13659–13669. doi: 10.1021/bi061456h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fran KJ, Nitz M, Imperiali B. ChemBiochem. 2003;4:265–271. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200390046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]