Abstract

Members of the Wnt family of secreted glycoproteins regulate many developmental processes, including cell migration. We and others have previously shown that the Wnts egl-20, cwn-1, and cwn-2 are required for cell migration and axon guidance. However, the roles in cell migration of all of the Caenorhabditis elegans Wnt genes and their candidate receptors have not been explored fully. We have extended our analysis to include all C. elegans Wnts and six candidate Wnt receptors: four Frizzleds, the sole Ryk family receptor LIN-18, and the Ror receptor tyrosine kinase CAM-1. We show that three of the Wnts, CWN-1, CWN-2, and EGL-20, play major roles in directing cell migrations and that all five Wnts direct specific cell migrations either by acting redundantly or by antagonizing each other's function. We report that all four Frizzleds function to direct Q-descendant cell migrations, but only a subset of the putative Wnt receptors function in directing migrations of other cells. Finally, we find striking differences between the phenotypes of the Wnt quintuple and Frizzled quadruple mutants.

CELL migration is an essential component of metazoan development. Many cell types, including cardiac precursors, primordial germ cells, melanocytes, and neurons migrate extensively during vertebrate development. In a related process, neuronal growth cones migrate to establish neural connections.

During Caenorhabditis elegans development, several cells migrate long distances (Figure 1; Sulston et al. 1983; Hedgecock et al. 1987). For example, during embryogenesis, the canal-associated neurons (CANs) migrate posteriorly to the middle of the animal. Anterior lateral microtubule neurons (ALMs) migrate posteriorly to positions between the nuclei of two nonmigratory marker cells, V2 and V3 (Sulston et al. 1983). Hermaphrodite-specific neurons (HSNs) and BDU neurons migrate anteriorly during embryogenesis (Sulston et al. 1983; Hedgecock et al. 1987). The left and right Q neuroblasts (QL and QR, respectively) and their descendants (QL.d and QR.d) migrate in opposite directions during the first larval stage (Sulston and Horvitz 1977). The QL.d cells migrate posteriorly, whereas QR.d cells migrate anteriorly (Sulston and Horvitz 1977).

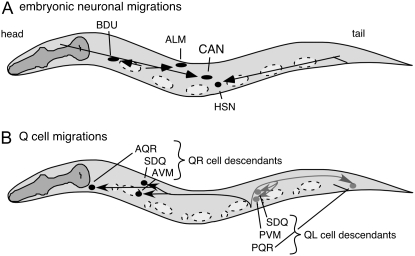

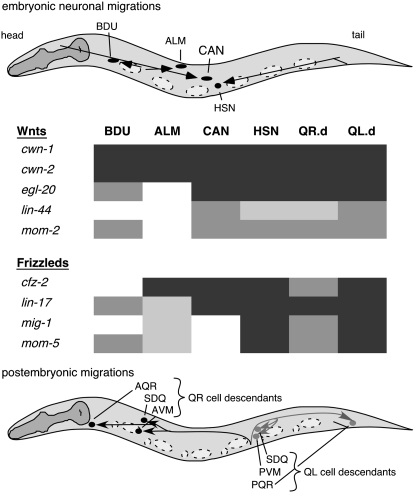

Figure 1.—

C. elegans cell migrations. Anterior is to the left and dorsal is up in all figures. (A) Embryonic cell migrations. Schematic lateral view of a newly hatched first larval stage hermaphrodite. Both the final positions of the ALM, BDU, CAN, and HSN cell bodies (ovals and circle) and their migration routes (arrows) are indicated. Dashed ovals show the positions of landmark nuclei (V cells) used in assessing cell position. (B) Q-neuroblast migrations. Schematic lateral view of first larval stage animal after the Q descendants have completed their migrations. Indicated are the final positions of the QR descendants SDQ, AVM, and AQR (solid circles) and their migration routes (solid arrows) and of the QL descendants SDQ, PVM, and PQR (shaded circles) and their migration routes (shaded arrows). Cell divisions and cell deaths in the Q lineages are not shown. Dashed ovals and circles show locations of the landmark hypodermal nuclei, Vn.a and Vn.p, used in assessing cell position.

Members of the Wnt family of secreted glycoproteins regulate many developmental processes, including cell migration. The C. elegans genome includes five Wnt genes: cwn-1, cwn-2, egl-20, mom-2, and lin-44 (Shackleford et al. 1993; Herman et al. 1995; Rocheleau et al. 1997; Thorpe et al. 1997; Maloof et al. 1999). EGL-20, CWN-1, and CWN-2 have been shown to direct cell migrations (Harris et al. 1996; Maloof et al. 1999; Forrester et al. 2004; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005; Pan et al. 2006) and guide neuronal axons (Hilliard and Bargmann 2006; Pan et al. 2006). MOM-2 specifies endodermal cell fates (Rocheleau et al. 1997; Thorpe et al. 1997). LIN-44 orients cell polarity (Herman and Horvitz 1994; Herman et al. 1995). All five Wnts function redundantly during vulval development to specify vulval precursor cell fates (Inoue et al. 2004; Gleason et al. 2006).

Several proteins that serve as receptors for Wnts have been described. Wnt receptors include members of the Frizzled (Frz) family of cell surface proteins (Bhanot et al. 1996; Hsieh et al. 1999; Dann et al. 2001). The C. elegans genome includes four Frizzled genes: lin-17, mig-1, cfz-2, and mom-5 (Sawa et al. 1996; Rocheleau et al. 1997; Ruvkun and Hobert 1998). Other proposed Wnt receptors include members of the Ryk/Derailed family of receptor tyrosine kinase-like proteins (Yoshikawa et al. 2003; Inoue et al. 2004). The C. elegans genome includes a single Ryk/Derailed homolog, lin-18 (Inoue et al. 2004). Members of the Ror family of receptor tyrosine kinase-like proteins have also been implicated as Wnt receptors in some species (Hikasa et al. 2002; Oishi et al. 2003; Mikels and Nusse 2006; Green et al. 2007). The sole C. elegans Ror, CAM-1, acts as a negative regulator of Wnt signaling (Forrester et al. 2004; Green et al. 2007).

Multiple signaling pathways act downstream of Wnts. In one, often referred to as the canonical/β-catenin Wnt-signaling pathway, Wnt proteins bind to Frizzleds to activate an intracellular cascade that results in the stabilization of cytoplasmic β-catenin. β-Catenin associates with transcription factors of the TCF/LEF family to regulate downstream gene expression (reviewed in Logan and Nusse 2004; Nusse 2005; Gordon and Nusse 2006).

In C. elegans, a canonical Wnt signal transduction pathway regulates the direction of migration of the Q neuroblasts and their descendants (reviewed in Herman 2002; Korswagen 2002; Silhankova and Korswagen 2007). EGL-20/Wnt and components of the canonical Wnt-signaling pathway regulate the QL-descendant expression of mab-5, which encodes an antennapedia homeobox protein (Harris et al. 1996; Maloof et al. 1999; Korswagen et al. 2000). Expression of mab-5 in QL results in posteriorly directed migrations, whereas the lack of mab-5 expression in QR results in anteriorly directed migrations (Salser and Kenyon 1992). Mutations in egl-20 or other components of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway transform QL.d to a QR.d-like fate, in which they do not express mab-5 and therefore migrate anteriorly (Harris et al. 1996; Costa et al. 1998; Maloof et al. 1999).

To further understand how Wnt signaling might regulate neuronal migrations, we have examined the roles of all five C. elegans Wnts, all four Frizzleds, the Ryk/Derailed, and Ror family members. We find that three of the Wnts, CWN-1, CWN-2, and EGL-20, play major roles in directing cell migrations. Furthermore, the migrations of some cells involved all five Wnts. Only a subset of the putative Wnt receptors functions in directing migrations of other cells whereas all four Frizzleds function to direct Q-descendant cell migrations. Our analysis of strains mutant for multiple Wnts and Frizzleds included Wnt quintuple and Frizzled quadruple mutants that lacked Wnt or Frizzled zygotic function. Interestingly, the cell migration phenotypes of the Wnt quintuple mutants differed strongly from those of the Frizzled quadruple mutants for most cells examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and C. elegans culture:

Strains were cultured as described (Brenner 1974) except as noted. In addition to the wild-type N2, strains containing the following mutations and transgenes were used in these studies:

LGI: mig-1(e1787), lin-17(n3091), lin-17(n671), dpy-5(e61) (Brenner 1974), mom-5(or57) (Thorpe et al. 1997), mom-5(ne12), lin-44(n1792) (Herman and Horvitz 1994), zdIs5 [mec-4∷gfp] (Clark and Chiu 2003);

LGII: cwn-1(ok546) (Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005) and cam-1(gm122) (Forrester and Garriga 1997);

LGIII: mab-5(e1741) (Salser and Kenyon 1992);

LGIV: egl-20(n585), egl-20(mu27) (Harris et al. 1996) and cwn-2(ok895) (Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005);

LGV: cfz-2(ok1201) (Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005), dpy-11(e224) (Brenner 1974), mom-2(or309) (Thorpe et al. 1997), and mom-2(ne874ts);

LGX: lin-18 (Inoue et al. 2004) and gmIs18[ceh-23-unc-76∷gfp, rol-6(su1006sd)].

Strains were grown at 20° except for the following: lin-44(n1792) zdIs5, cwn-1(ok546), egl-20(n585) cwn-2(ok895)/nT1 [qIs48], and mom-2(ne874ts)/nT1 mutant animals were grown at 15°. Homozygous lin-44(n1792) zdIs5, cwn-1(ok546); egl-20(n585) cwn-2(ok895), and mom-2(ne874ts) Wnt quintuple-mutant progeny were grown at 15° until embryos were produced. Early embryos were shifted to the restrictive temperature of 22.5°, allowed to hatch, and scored for Q.d cell positions. All multiply mutant strains that include mom-2 or egl-20 carried the mom-2(or309) and egl-20(mu27) alleles with the exception of the Wnt quintuple mutant. Similarly, multiply mutant strains that include a mom-5 mutation carry the mom-5(or57) allele with the exceptions of mig-1(e1787) lin-17(n671) mom-5(ne12)/hT2 I;III [qIs48]; cfz-2(ok1201), and mig-1(e1787) lin-17(n671) mom-5(ne12)/hT2 I;III [qIs48]. Strains reported carry the lin-17(n671) allele except for lin-17(n3091); cfz-2(ok1201).

Genotypes of strains carrying multiple mutations were confirmed by PCR for deletions or sequencing of individual mutations. The egl-20(mu27) cwn-2(ok895) double-mutant strain was made by identifying Egl non-Dpy recombinant progeny from egl-20(mu27) dpy-20(e1282ts)/cwn-2(ok895) heterozygous parents and screening for the presence of the cwn-2 mutation. Homozygous egl-20 cwn-2 mutants were identified by PCR and DNA sequencing.

Wnt ligand and receptor mutant alleles used in this study either eliminate or severely reduce gene function with the exception of mom-2(ne874ts). mom-2(ne874ts) is a temperature-sensitive allele; at the restrictive temperature, it produces a phenotype similar to that of the null mutation.

Quadruple Frizzled mutants were derived from hermaphrodites heterozygous for mig-1, lin-17, and mom-5 and therefore might retain maternal product from those genes. Similarly, animals homozygous mutant for mom-2(or309) were derived from heterozygous mothers and therefore might retain maternal product.

Characterization of migratory cell position:

Cell migrations in wild type, mutant, and transgenic animals were assessed by comparing the positions of nuclei relative to the nuclei of nonmigratory hypodermal cells using Nomarski optics with a Nikon E600 microscope. We scored the positions of embryonically migrating ALM, BDU, CAN, and HSN cells relative to nonmigratory hypodermal V and P cells in newly hatched first larval stage (L1) hermaphrodites. We scored the final positions of the postembryonically migrating Q descendants relative to the hypodermal Vn.a and Vn.p cells in mid-L1 stage hermaphrodites. In most strains examined, the positions of the V and P cells appeared unchanged. However, in strains containing simultaneous mutations in the three Wnts cwn-1, egl-20, and cwn-2, V and P cells occasionally appeared altered in their positions.

Mutating lin-17 and mom-5 Frizzleds simultaneously resulted in cell lineage defects, producing extra mec-4∷gfp-expressing cells. These cells were similar in morphology to wild-type Q descendants and expressed the Q-cell marker mec-4∷gfp. Because these cells were indistinguishable from normal Q descendants, their cell positions were included in the data analysis. No Wnt mutations were observed to produce extra Q cells.

Statistical analysis:

Final positions of migrating cells were compared using statistical methods to assess the significance of the difference in cell positions among strains. To quantitate cell positions, the distance between the start of a migratory route and the farthest observed final wild-type cell position was divided into 100 increments (to reflect 100% migration if a cell reached its final position). Cells that migrated beyond the normal range of positions were assigned a value >100% using the same scale. Conversely, cells that migrated in the opposite direction were assigned a value less than zero using the same scale. The cell position values were compared using the Mann–Whitney nonparametric hypothesis test, which does not make assumptions of normality, using Minitab statistical software.

RESULTS

Multiple Wnts direct embryonic neuronal migrations:

Three C. elegans Wnts, CWN-1, CWN-2, and EGL-20, play major roles in directing the embryonic migrations of the cells that we examined, as described below. Two Wnts, CWN-1 and CWN-2, functioned in the migrations of all four of the following cells: CAN, ALM, BDU, and HSN (Table 1; Figures 2–7). EGL-20 participated in directing each of these migrations although it did not appear to play a major role in migrating ALMs. The remaining Wnts, LIN-44 and MOM-2, appeared to perform more limited roles in the migrations of specific cell types, as discussed below.

TABLE 1.

Cell migrations

| ALMa

|

BDUb

|

CANc

|

HSNd

|

QLe

|

QRf: | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Anterior | Posterior | Anterior | Posterior | Anterior | Posterior | Anterior | Posterior | N | Anterior | Posterior | N | Posterior | N |

| Wild typeg | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 65 | 0 | 0 | 57 | 3.1 | 32 |

| Wnt mutants | ||||||||||||||

| cwn-1g | 7.9 | 0 | 0 | 18.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 72.7 | 33 |

| cwn-2g | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | 44.7 | 23.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 46.7 | 30 |

| egl-20g | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 80.0 | 30 | 96.3 | 0 | 54 | 93.8 | 32 |

| lin-44g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 29 | 7.7 | 37 |

| mom-2g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 36 |

| lin-44; cwn-1 | 11.6 | 0 | 0 | 21.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.9 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 90.3 | 32 |

| lin-44; egl-20 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 4.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 92.0 | 25 | 90.6 | 0 | 32 | 59.4 | 32 |

| cwn-1; egl-20g | 2.9 | 5.9 | 0 | 12.1 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 34 | 9.3 | 0 | 43 | 100 | 30 |

| cwn-1; mom-2h | 0 | 0 | 0 | 29.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.8 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 89.5 | 40 |

| egl-20 cwn-2 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 0 | 55.0 | 28.3 | 11.7 | 0 | 84.6 | 59 | 100 | 0 | 48 | 95.5 | 44 |

| cwn-1; cwn-2g | 48.8 | 2.4 | 0 | 71.4 | 35.7 | 33.3 | 0 | 60.0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 90.3 | 31 |

| cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 | 34.9 | 4.7 | 2.3 | 39.5 | 59.1 | 2.3 | 0 | 95.2 | 42 | 5.0 | 65.0 | 40 | 100 | 28 |

| lin-44; egl-20 cwn-2 | 4.0 | 0 | 22.0 | 34.0 | 32.0 | 10.0 | 0 | 93.5 | 50 | 100 | 0 | 30 | 100 | 30 |

| egl-20 cwn-2; mom-2h | 0 | 6.5 | 0 | 58.1 | 9.7 | 35.5 | 0 | 75.9 | 31 | 96.0 | 0 | 50 | 100 | 52 |

| lin-44; cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 | 20.7 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 60.7 | 38.0 | 3.4 | 0 | 96.2 | 29 | 7.5 | 40.0 | 40 | 100 | 40 |

| lin-44; cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2; mom-2h | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0 | 41.7 | 41.7 | 12 | 100 | 20 |

| Candidate Wnt receptor mutants | ||||||||||||||

| cfz-2g | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 58 | 11.7 | 60 |

| mig-1 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63.6 | 23 | 50.7 | 5.5 | 73 | 3.1 | 52 |

| lin-17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.0 | 30 | 18.6 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 |

| mom-5ghi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 0 | 0 | 13.3 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 86.7 | 30 |

| lin-18 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 2.3 | 44 |

| cam-1g | 27.1 | 0 | 0 | 14.1 | 85.7 | 0 | 65.2 | 0 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 38.5 | 39 |

| mig-1 lin-17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37.1 | 36 | 30.3 | 12.1 | 34 | 0 | 36 |

| lin-17; cfz-2 | 7.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.3 | 0 | 0 | 17.9 | 40 | 25.0 | 0 | 36 | 3.6 | 56 |

| mom-5; cfz-2gh | 3.2 | 0 | 0 | 3.4 | 29.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 100 | 30 |

| mig-1; cfz-2 | 4.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 92.7 | 41 | 77.3 | 0 | 46 | 4.3 | 46 |

| lin-17 mom-5 | 5.3 | 2.6 | 0 | 23.7 | 10.5 | 0 | 0 | 21.1 | 38 | 16.7 | 5.0 | 63 | 100 | 74 |

| cfz-2; lin-18 | 4.5 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 | 13.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 40 |

| cam-1; cfz-2 | 21.4 | 3.6 | 12.0 | 8.0 | 72.4 | 0 | 50.0 | 3.6 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 13.3 | 30 |

| mig-1; cfz-2; lin-18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 | 6.8 | 0 | 0 | 74.4 | 44 | 82.2 | 8.9 | 46 | 5.5 | 36 |

| mig-1 lin-17; cfz-2 | 10.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.0 | 0 | 0 | 38.8 | 47 | 53.7 | 22.0 | 42 | 2.1 | 48 |

| mig-1 lin-17 mom-5h | 10.0 | 0 | 0 | 6.7 | 10.0 | 3.3 | 0 | 56.7 | 30 | 57.8 | 15.6 | 45 | 96.6 | 59 |

| mig-1 lin-17 mom-5; cfz-2h | 0 | 0 | 5.7 | 17.1 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 74.3 | 34 | 35.6 | 34.5 | 87 | 91.4 | 70 |

| Wnt and candidate receptor mutants | ||||||||||||||

| egl-20; cfz-2g | 5.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.3 | 0 | 0 | 72.2 | 36 | 90.6 | 0 | 32 | 56 | 25 |

| lin-44; cfz-2 | 10.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 8.6 | 36 |

| cwn-1; cfz-2g | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 15.2 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 4.3 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 94.3 | 35 |

| cwn-2; cfz-2g | 5.1 | 0 | 0 | 45.5 | 39.4 | 0 | 0 | 2.1 | 98 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 51.6 | 31 |

| mom-5; cwn-1h | 0 | 3.4 | 0 | 46.2 | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 7.1 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 38 | 100 | 38 |

| cam-1 cwn-1 | 28.6 | 0 | 2.5 | 30.0 | 90.9 | 0 | 41.5 | 2.4 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 69.0 | 30 |

| cam-1; cwn-2 | 61.9 | 0 | 1.3 | 17.8 | 73.3 | 0 | 56.1 | 2.4 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 44 | 53.4 | 46 |

| cam-1; egl-20 cwn-2 | 44.1 | 8.8 | 28.9 | 28.1 | 85.3 | 0 | 12.9 | 54.8 | 31 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| lin-44; cwn-1; cfz-2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.3 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 71.4 | 26 |

| egl-20 cwn-2; cfz-2 | 7.0 | 0 | 7.1 | 59.5 | 60.5 | 2.3 | 0 | 79.5 | 41 | 100 | 0 | 38 | 100 | 30 |

| cwn-1; cwn-2; cfz-2g | 36.4 | 18.2 | 0 | 74 | 75.0 | 0 | 0 | 67.5 | 44 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 95.0 | 40 |

| lin-44; egl-20 cwn-2; cfz-2 | 7.7 | 0 | 8.6 | 42.9 | 25.6 | 17.9 | 0 | 91.7 | 37 | 100 | 0 | 30 | 100 | 40 |

| mab-5(gf)j | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.4 | 0 | 0 | 2.1 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 4.0 | 50 | 0 | 44 |

| cwn-1; mab-5(gf); egl-20 cwn-2j | 20.7 | 13.8 | 0 | 48.1 | 60.6 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 34.1 | 44 | 100 | 47 |

Cell positions were assessed by Nomarski optics. ALM, BDU, CAN, and HSN positions were determined in newly hatched hermaphrodite larvae (L1). QR- and QL-descendant positions were determined in older L1 stage hermaphrodites after the V cells had divided. Numbers are the percentage of cells that failed to migrate to their normal position. N, number of cells scored. ND, not determined.

An ALM was scored as anteriorly misplaced (Anterior) if its nucleus was anterior to the V2 nucleus and posteriorly misplaced (Posterior) if posterior to the V3 nucleus.

A BDU was scored as anteriorly misplaced (Anterior) if its nucleus was more than a V-cell diameter anterior to the V1 nucleus and posteriorly misplaced (Posterior) if posterior to the V1 nucleus.

A CAN was scored as anteriorly misplaced (Anterior) if its nucleus was anterior to the V3 nucleus and posteriorly misplaced (Posterior) if posterior to the V4 nucleus.

An HSN was scored as anteriorly misplaced (Anterior) if its nucleus was anterior to the V3 nucleus and posteriorly misplaced (Posterior) if posterior to the V4 nucleus.

A QL-cell descendant was scored as misplaced anteriorly (Anterior) if its nucleus was anterior to V4.p. and posteriorly misplaced (Posterior) if posterior to the V5.p nucleus. Because they occupy positions near each other, the data for SDQL and PVM were combined. The position of PQR, a third QL descendant, was not included because it migrates to a location near other nuclei with similar morphology.

A QR-cell descendant was scored as posteriorly misplaced (Posterior) if its nucleus was posterior to the V2.a nucleus. Because they occupy positions near each other, the data for SDQR and AVM were combined. The position of AQR, a third QR descendant, was not included because it migrates to a location near other nuclei with similar morphology.

Some of these data have been reported elsewhere (Kim and Forrester 2003; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005). They are presented here for comparison.

These animals were homozygous mutant progeny of heterozygous parents. See materials and methods for more information.

These animals were homozygous mutant progeny of dpy-5 mom-5/nT1 parents. Cell migration is normal in dpy-5 homozygous mutant animals.

These animals were mutant for the gain-of-function mab-5(e1751) allele.

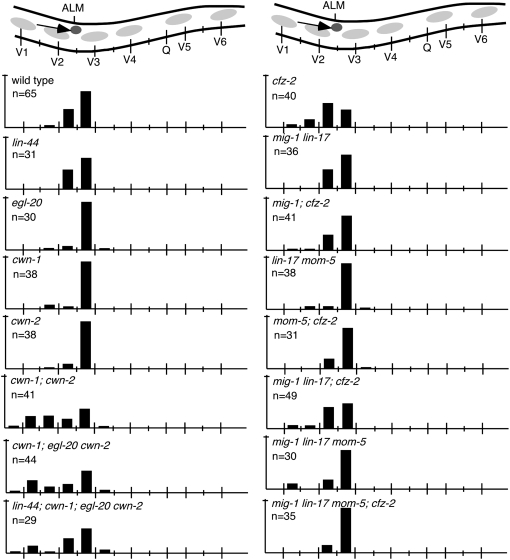

Figure 2.—

ALM cell migration. (Top) A schematic of the middle section of an animal with the ALM cell (darkly shaded circle) and its migration route (arrow). Bars represent the percentage of ALM cells located at that position along the anterior–posterior axis of L1 larvae. Long tick marks on the animal (top) and on the x-axis denote the location of V- and Q-cell nuclei and short tick marks denote the location of P-cell nuclei. The tick mark on the y-axis indicates 100%. n, number of ALM cells tallied.

Figure 3.—

Representative ALM cell migration defect. (Right) Enlargement of the boxed region. (A) In wild type, ALM (arrow) migrates to positions between V2 and V3 nonmigratory marker cells. (B) In cwn-1; cwn-2 mutants, ALM (arrow) is often misplaced anteriorly and is found above the nuclei of the V1 marker cell. Bars, 20 μm.

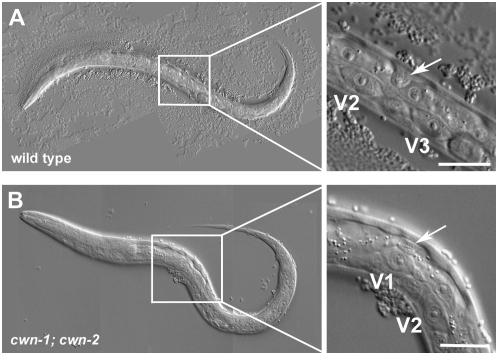

Figure 4.—

CAN cell migration. (Top) A schematic of the anterior section of an animal with the CAN cell (darkly shaded circle) and its migration route (arrow). Data are presented as described in the legend to Figure 2.

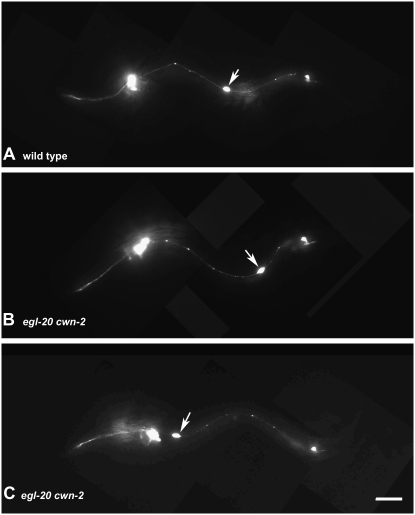

Figure 5.—

Representative CAN cell migration defects. Immunofluorescent photomicrographs of larvae carrying a ceh-23∷gfp transgene. (A) In wild type, CAN (arrow) migrates to the middle of the animal. (B) In egl-20 cwn-2 mutants, CAN (arrow) is sometimes misplaced posteriorly. (C) In egl-20 cwn-2 mutants, CAN (arrow) is often misplaced anteriorly. Bar, 20 μm.

Figure 6.—

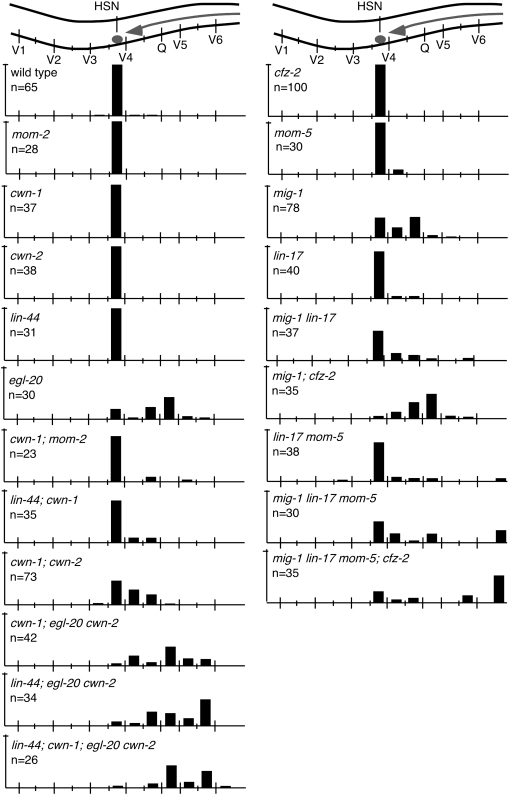

HSN cell migration. (Top) A schematic of the middle section of an animal with the HSN cell (darkly shaded circle) and its migration route (arrow). Data are presented as described in the legend to Figure 2.

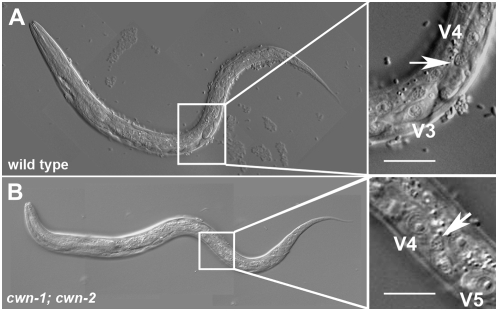

Figure 7.—

Representative HSN cell migration defect. (A) In wild type, HSN (arrow) migrates to positions between V3 and V4 nonmigratory marker cells. (B) In cwn-1; cwn-2 mutants, HSN (arrow) is misplaced posteriorly. Bars, 20 μm.

Analysis of cwn-1 and cwn-2 mutant animals revealed that these two Wnts collaborate to direct ALM cell migrations (Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005). Mutating cwn-1 or cwn-2 alone did not result in ALM cell positions significantly different from wild type (7.9 or 2.6%, respectively, vs. 3.1% in wild type; P > 0.1; Table 1; Figure 2). In the cwn-1; cwn-2 double mutants, ALMs were displaced anteriorly significantly farther than in either single mutant (48.8%; Table 1; Figures 2 and 3; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005). Mutation of additional Wnts did not further alter ALM migration defects to a statistically significant level (P > 0.1; Table 1; Figure 2).

BDU cell migrations were directed in a manner similar to those of ALM, requiring the same Wnts (Table 1). Mutation of cwn-1 or cwn-2 alone produced BDU cell migration defects (18.4 or 44.7%, respectively; Table 1). In contrast to migrating ALMs, however, mutating egl-20 in the absence of both cwn-1 and cwn-2 strongly suppressed the BDU defect of the cwn-1; cwn-2 double (39.5 vs. 71.4% of BDUs misplaced; P < 0.02; Table 1), suggesting that egl-20 may antagonize cwn-1 and cwn-2 function in BDU cell migration. Mutating lin-44 and egl-20 in the absence of other Wnts caused some BDU cells to migrate to abnormally anterior positions (Table 1).

CWN-1, CWN-2, and EGL-20 played major roles in directing CAN cell migrations (Table 1; Figures 4 and 5). Mutation of cwn-2 alone, but not of cwn-1 or egl-20, produced CAN cell migration defects with 23.7% of CANs misplaced in cwn-2 mutants (Table 1; Figure 4; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005). Simultaneous mutations in cwn-1 and cwn-2 enhanced the CAN cell migration defects of the single mutants (35.7% of CANs anteriorly and 33.3% posteriorly misplaced; Table 1; Figures 4 and 5; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005). Furthermore, simultaneous mutation of cwn-1, cwn-2, and egl-20 produced an even greater enhancement (59.1% of CANs anteriorly misplaced; P < 0.005; Table 1; Figure 4). Similarly, mutation of mom-2 enhanced the CAN cell overmigration phenotype of the egl-20 cwn-2 double mutants with 35.5% of CANs posteriorly misplaced in mom-2; egl-20 cwn-2 vs. 11.7% in egl-20 cwn-2 (P < 0.04; Table 1; Figure 4), suggesting that MOM-2 functions with EGL-20 and CWN-2 to prevent overmigration of the CANs. Simultaneous mutation of lin-44; cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 suppressed the CAN cell migration defects of the cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 triple mutants to 38.0% (P < 0.05; Table 1; Figure 4).

All five Wnts function to direct HSN cell migrations (Table 1; Figures 6 and 7; Pan et al. 2006). Mutating any single Wnt gene other than egl-20 did not produce defects in the migrations of HSN neurons (Table 1; Figure 6). However, mutations in two or more Wnts produced synthetic or enhanced defects in HSN migration, revealing that each of the five Wnts functions in HSN cell migration (Table 1; Figures 6 and 7).

Multiple Frizzleds direct embryonic cell migrations:

Unlike mutation of individual Wnt genes, mutation of individual Frizzled genes produced few cell migration defects. For example, mutation of cfz-2 caused 20% of ALMs to be misplaced, but did not affect BDU, CAN, or HSN migrations (Table 1; Figures 2, 4, and 6; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005). Similarly, mutation of mig-1 produced significant HSN cell migration defects, but did not affect CAN, ALM, or BDU migrations (Table 1; Figure 6; Pan et al. 2006).

Assessing cell position in animals simultaneously mutant for multiple Frizzleds revealed additional roles in directing specific cell migrations. cfz-2 is the sole Frizzled required for ALM migration (Table 1; Figure 2; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005). Although mig-1 lin-17 mom-5 produced an apparent ALM cell migration defect, cell position was not significantly different from wild type (P > 0.4). Mutations in mig-1 or mom-5 each suppressed the ALM migration defects caused by a mutation in cfz-2 from 20.0 to 3.2% in mom-5; cfz-2 or to 4.9% in mig-1; cfz-2 mutants (P < 0.03, Table 1; Figure 2). Simultaneous mutation of mig-1 lin-17 mom-5; cfz-2 also suppressed the ALM defect of cfz-2 mutant animals to 0% (P < 0.0001; Table 1; Figure 2).

Mutations in single Frizzled mutants did not cause significant BDU migration defects whereas mutating both mom-5 and lin-17 did (Table 1). Mutating all four Frizzleds did not increase the BDU defects of the mom-5; lin-17 double mutant (Table 1).

CFZ-2 and MOM-5 redundantly direct CAN cell migration (Table 1; Figure 4; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005). In cfz-2 or mom-5 single mutants, CANs were not significantly misplaced, but in the cfz-2; mom-5 double mutants, they were misplaced 29% of the time (Table 1; Figure 4). Mutations in all four Frizzleds resulted in a CAN defect statistically similar to that produced in mom-5; cfz-2 mutants with 14.3% of CANs misplaced in the quadruple mutant vs. 29.0% in mom-5; cfz-2 (P > 0.4; Table 1; Figure 4), suggesting that LIN-17 and MIG-1 do not function in CAN cell migration.

MIG-1 and CFZ-2 appear to be the major Frizzleds involved in HSN cell migration (Table 1; Figure 6). Mutating cfz-2 alone had no effect on HSN position whereas mutation in mig-1 shifted the majority of the HSNs posteriorly (Table 1; Figure 6; Harris et al. 1996; Forrester et al. 2004; Pan et al. 2006). Simultaneous mutation of cfz-2 and mig-1 produced a farther posterior shift in the final HSN position (Table 1; Figure 6). Mutating lin-17 suppressed the HSN cell migration defect of mig-1; cfz-2 double mutants (38.8% of HSNs were misplaced in mig-1 lin-17; cfz-2 vs. 92.7% in mig-1; cfz-2 mutants; P < 0.0001; Table 1; Figure 6; Pan et al. 2006). mig-1 lin-17 mom-5; cfz-2 quadruple mutants showed the strongest defect in HSN cell migrations, where many of the HSNs were not able to migrate out of the tail (Table 1; Figure 7), indicating redundancy among the Frizzleds for HSN migration.

Interestingly, simultaneously mutating four Wnts in general produced cell migration defects more severe than mutating any combination of Frizzleds. For example, mutation of lin-44; cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 produced CAN, ALM, and BDU defects that were more severe than in any combination of Frizzled mutants that we examined (Table 1; Figures 2–7).

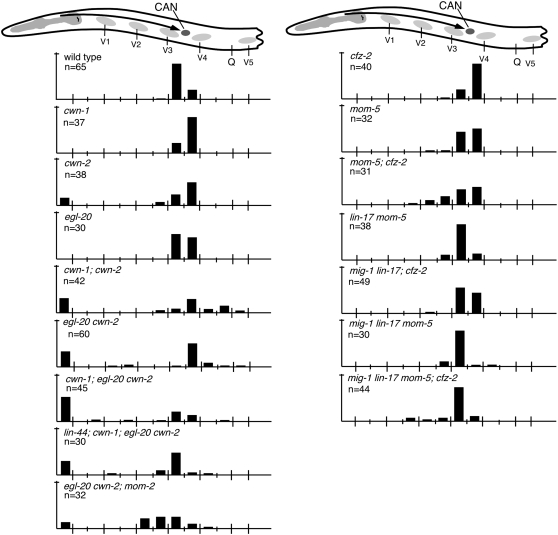

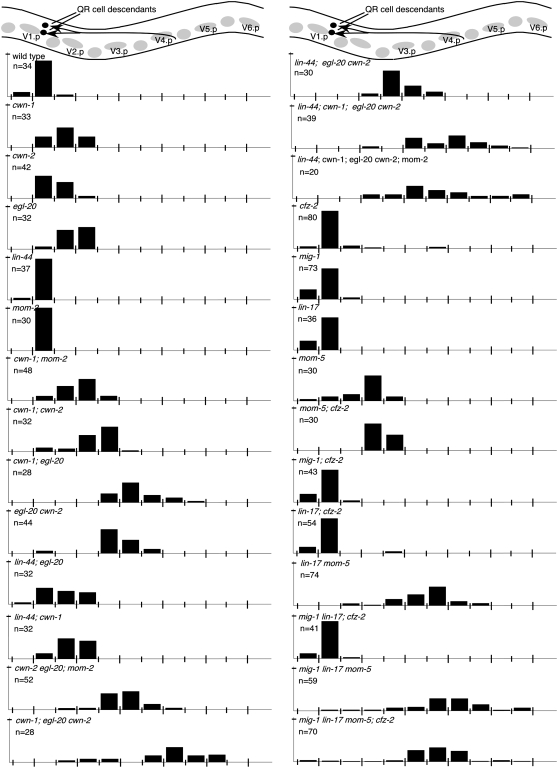

Multiple Wnts and Frizzleds redundantly regulate postembryonic migrations of the QR.d neuroblasts:

QR neuroblast descendants migrate anteriorly during the first larval stage, with the QR descendants AVM and SDQR ending their migrations between two nonmigratory cells, V1.a and V2.a, (Figures 1 and 8; Sulston and Horvitz 1977). Single mutation of cwn-1, cwn-2, or egl-20 produced QR.d migration defects whereas mutation of lin-44 or mom-2 did not (Table 1; Figure 8; Maloof et al. 1999; Whangbo and Kenyon 1999). Most pairwise Wnt mutant combinations further enhanced QR.d migration defects (Table 1; Figure 8). However, mutation of lin-44 partially suppressed the QR.d defect of egl-20 mutants (Figure 8). The QR.d migration defects of lin-44, cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2; mom-2 quintuple animals were no more severe than those of cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 mutant animals, suggesting that these three Wnts play major roles in directing QR.d migrations (Table 1; Figure 8). In both the cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 triple and the lin-44, cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2; mom-2 quintuple mutants, some QR.d cells were found posterior to their birthplace, indicating that they had migrated posteriorly (Figure 8).

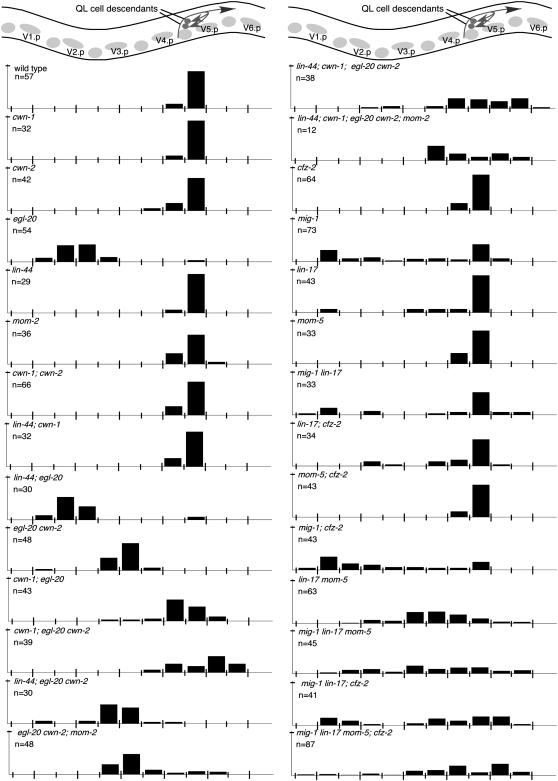

Figure 8.—

QR-descendant migration. (Top) A schematic lateral view of the middle section of a late L1 animal. Lightly shaded circles and ovals show the position of landmark Vn.a and Vn.p nuclei (each Vn.p is named). The final positions of the cell bodies of the QR descendants, SDQ and AVM (darkly shaded circles), and their migration routes (darkly shaded arrows) are indicated. Bars represent the percentage of QR descendants located at that position along the anterior–posterior axis of L1 larvae. The long tick marks on the x-axis indicate the location of Vn.p nuclei and the short tick marks indicate the location of Vn.a nuclei. The tick mark on the y-axis denotes 100%. Data for SDQ and AVM were combined. AQR was not included because it migrates to a location near other neurons, making its position difficult to score.

Each of the Frizzled receptors participates in directing QR.d migrations (Table 1; Figure 8). Mutation of individual Frizzled genes produced little effect on QR.d migration, with the exception of mom-5 (Table 1; Figure 8). Simultaneous mutations in mig-1 lin-17; cfz-2 produced no QR.d migration defects, suggesting that these genes play minor or no roles in this migration in the presence of wild-type MOM-5 (Table 1; Figure 8). However, mutating one or more Frizzleds in combination with mom-5 revealed roles for the other Frizzleds in QR.d migrations. For example, mutation of cfz-2, lin-17, or mig-1 and lin-17 together each enhanced the mom-5 QR.d cell migration defects (Table 1; Figure 8). The defects of the quadruple Frizzled mutant resembled those of the quintuple Wnt mutant except that some QR.d cells were found more posterior in the Wnt quintuple mutant (Figure 8).

Multiple Wnts and Frizzleds redundantly regulate the postembryonic migrations of the QL.d neuroblasts:

QL neuroblast descendants migrate posteriorly during the first larval stage, with the PVM and SDQL cells ending their migrations between two nonmigratory cells, V5.a and V5.p (Figure 1; Sulston and Horvitz 1977). Mutation of egl-20 transforms QL to a QR-like fate, causing its descendants to inappropriately migrate in an anterior direction (Maloof et al. 1999; Whangbo and Kenyon 1999). Mutation of cwn-1 and cwn-2 in an egl-20 mutant background resulted in QL.d positions that were posterior to those in egl-20 alone (Figure 9). One interpretation of this effect is that mutation in cwn-1 or cwn-2 enhances the cell migration defect of the now QR-like cells that result from mutation in egl-20. Consistent with this, the mab-5 gain-of-function allele e1751 is able to partially rescue the cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 mutant phenotype, presumably by restoring QL cell fate (Table 1; data no shown). Absence of cwn-1, cwn-2, and egl-20 or of all five Wnts not only caused the QL.d cells to remain in the posterior but also sometimes shifted them posterior to their normal positions (Figure 9). QL.d cells were shifted slightly anteriorly in lin-44; egl-20 and lin-44; egl-20 cwn-2 mutants compared to egl-20 and egl-20 cwn-2 mutant animals, respectively (Figure 9).

Figure 9.—

QL-descendant migration. (Top) A schematic lateral view of the middle section of a late L1 animal. Lightly shaded circles and ovals show the positions of landmark Vn.a and Vn.p nuclei (each Vn.p is named). The final positions of the cell bodies of the QL descendants, SDQ and PVM (darkly shaded circles), and their migration routes (darkly shaded arrows) are indicated. Bars represent the percentage of QL descendants located at that position along the anterior–posterior axis of L1 larvae. The long tick marks on the x-axis indicate the location of Vn.p nuclei and the short tick marks indicate the location of Vn.a nuclei. The tick mark on the y-axis denotes 100%. Data for SDQ and PVM were combined. PQR was not included because it migrates to a location near other neurons, making its position difficult to score.

Mutations in the Frizzleds mig-1 and lin-17 cause QL.d to migrate to the anterior, similar to QR.d (Table 1; Figure 9; Harris et al. 1996). In animals mutant for both mig-1 and lin-17, some QL descendants were misplaced posterior to their birth positions. Single mutations in cfz-2 or mom-5 did not affect QL.d migrations (Table 1; Figure 9). Addition of a mom-5 mutation to that of lin-17 or both mig-1 and lin-17 shifted the average QL.d position farther to the posterior (Figure 9). Mutation of cfz-2 along with mig-1 and lin-17 sometimes shifted QL.d more posterior to the QL birth position (Figure 9). In animals mutant for all four Frizzleds, QL.d cells were distributed along the length of the animal (Figure 9). Because mutations in mig-1 and lin-17 transform QL to a QR-like fate (Harris et al. 1996), we cannot separate their effects on fate from their effects on migration.

Specific Wnts may function through specific receptors:

Because Frizzleds can function as cell surface receptors for Wnts, we have begun to examine cell migration in some Wnt/Frz mutant combinations to begin to gain insights into the Wnts and Frzs that function together. If a Wnt functions in the same pathway as a Frizzled to guide migrations of a given cell, we expect to see no enhancement of the double-mutant phenotype compared to that of a single Wnt and Frizzled mutant.

We found that loss of cfz-2 in cwn-2, cwn-1; cwn-2, or egl-20 cwn-2 mutant backgrounds increased the CAN migration defects of the Wnt mutants, suggesting that cwn-2 and egl-20 do not direct CAN migration through cfz-2 (Table 1). In contrast, loss of cfz-2 from a cwn-1 mutant background did not result in an enhanced CAN defect, suggesting that CWN-1 might function in the same pathway as CFZ-2 (Table 1).

Loss of cfz-2 in the cwn-2 mutant background did not result in an enhanced QR.d defect, suggesting that CWN-2 might function with CFZ-2 in QR.d migrations (Table 1; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005). In contrast, we found that mutations in mom-5/fz and cwn-1/wnt mutually enhanced the QR.d migration defect, suggesting that cwn-1 functions in a pathway parallel to mom-5 (Table 1). Similarly, mutating cfz-2 in the absence of cwn-1 also enhanced the QR.d defect (Table 1; Zinovyeva and Forrester 2005).

Roles of non-Frizzled Wnt-interacting proteins in neuronal migrations:

In addition to the four Frizzleds, the C. elegans genome contains a Ryk/Derailed homolog, lin-18, and a Ror/atypical RTK homolog, cam-1, each of which has been implicated in Wnt-signaling pathways: lin-18 as a putative receptor (Inoue et al. 2004) and cam-1 as a negative regulator of Wnt signaling (Forrester et al. 2004; Green et al. 2007).

lin-18 mutations cause ALMs to undermigrate (Table 1). Interestingly, simultaneous mutation of cfz-2 and lin-18 suppressed the ALM undermigration phenotype of cfz-2 (Table 1), suggesting lin-18 involvement in ALM cell migration as an antagonist of CFZ-2 function. The lin-18 mutation on its own or in combination with other Frizzled mutants did not cause statistically significant defects in the migrations of any other neurons (Table 1; data not shown).

cam-1, a Ror/RTK homolog, negatively regulates EGL-20/Wnt signaling in HSN migrations (Forrester et al. 2004). Mutation of cam-1 produced an ALM cell migration defect (Table 1). cam-1 cwn-1 mutant animals showed ALM defects similar in severity to those of cam-1 alone (Table 1). In contrast, mutation of both cam-1 and cwn-2 enhanced the ALM migration defect over the single mutants (Table 1). Similarly, mutation of cam-1 enhanced the ALM defects of the egl-20 cwn-2 double mutant (Table 1), suggesting that cwn-2 and egl-20 are not targets of cam-1 negative regulation in ALM migration.

Mutation in cam-1 produces a CAN cell migration defect (Table 1; Forrester and Garriga 1997). We found that cwn-1 cam-1, cam-1; cwn-2, and cam-1; cfz-2 doubly mutant animals each showed a CAN defect similar in severity to that of cam-1 alone (P > 0.1; Table 1; Figure 2), suggesting that CWN-1, CWN-2, and CFZ-2 function with CAM-1 to coordinate CAN cell migration. The different CAN and ALM phenotypes seen in the cam-1; cwn-2 double vs. the single mutants suggest that the CWN-2 and CAM-1 functional relationship differs with respect to ALM and CAN cell migrations.

Mutation in cam-1 causes BDUs and HSNs to migrate too far (Forrester and Garriga 1997; Forrester et al. 1999). Interestingly, mutations in cam-1 suppressed the BDU and HSN undermigration defects of the egl-20 cwn-2 double mutant perhaps by stimulating BDU and HSN migration (Table 1). Mutations in cam-1 also produced a posterior shift in QR.d positions (Table 1; Forrester and Garriga 1997; Forrester et al. 2004). The cam-1 mutations did not enhance the QR.d migration defect of cwn-1 or cwn-2 mutants (Table 1), suggesting that CAM-1 may function with the two Wnts in directing QR.d migrations.

DISCUSSION

The C. elegans genome contains five Wnt and four Frizzled genes (Shackleford et al. 1993; Herman et al. 1995; Sawa et al. 1996; Rocheleau et al. 1997; Thorpe et al. 1997; Ruvkun and Hobert 1998; Maloof et al. 1999). In addition, it includes the Ryk/Derailed-related Wnt receptor lin-18 (Inoue et al. 2004) and the Ror/RTK family member cam-1 (Forrester et al. 1999; Koga et al. 1999). In this study, we examined the roles of all Wnts and their candidate receptors in embryonic and postembryonic cell migrations. We found that each Wnt and Frizzled is involved in directing the migrations of one or more neurons. Our analysis revealed that CWN-1, CWN-2, and EGL-20 play major roles in directing embryonic and postembryonic cell migrations; simultaneous mutations in these genes generally produced the most pronounced cell migration defects. We found that the Ror/RTK-like receptor CAM-1, an apparent negative regulator of Wnt signaling (Forrester et al. 1999, 2004; Green et al. 2007), functions with the Wnts to direct multiple cell migrations.

Wnt and Frizzled interactions:

HSN and Q-cell migrations involve all five Wnts, and CAN cell migrations involve four Wnts (Figure 10). Similarly, HSN and Q-cell migrations involve all four Frizzleds, and CAN migrations involve two Frizzleds. Why is such extensive redundancy among the Wnts and Frizzleds necessary to direct cell migrations? One possibility is that multiple Wnts are needed to direct migrating cells and to fine tune cell positions, especially for cells migrating longer distances. The spatial and temporal distribution of Wnts may combine to provide directional and positional information to migrating cells. For example, posteriorly expressed CWN-1, EGL-20, and LIN-44 could all repel HSNs away from the posterior, and midbody-expressed MOM-2 could attract HSNs to the midbody. Similarly, multiple Wnt signals could guide and precisely position the CAN cells in the midbody region of the animal. These scenarios assume that Wnts act as guidance cues. Although EGL-20 has been shown to act as a repellent for HSN migration (Pan et al. 2006), the mechanisms by which other Wnts influence migration are less clear. An alternate possibility is that other Wnts specify fates of migrating or surrounding cells. A third possibility combines the first two, with some Wnts specifying fates of some cells and others acting as guidance cues. Indeed, individual Wnts can serve both roles; EGL-20 appears to specify QL fate (Maloof et al. 1999; Whangbo and Kenyon 1999) and guide HSN migrations (Pan et al. 2006). Furthermore, the observation that egl-20 mutation converts QL to a QR fate and that QR fails to migrate fully raises the possibility that EGL-20 provides both functions for the Q cells.

Figure 10.—

Wnts and Frizzleds direct migrations of multiple neurons. Dark shading represents strong Wnt or Frizzled involvement in directing migrations of specific neurons, while lighter shading represents lesser Wnt or Frizzled involvement in directing cell migrations on the basis of the severity of mutant phenotypes.

How can multiple Wnts and their candidate receptors combine to direct cell migrations? In principle, multiple Wnts could direct cell migrations through separate receptors, or individual Wnts could promiscuously bind multiple receptors. Wnt-binding promiscuity has been suggested as a model to account for Wnt redundancy (Pan et al. 2006). If true, then such binding promiscuity does not extend to all cells examined. In some cases, our data show that multiple, independent Wnt-signaling pathways direct the migration of a single cell. For example, CWN-2 functions redundantly with both CWN-1 and CFZ-2, while CWN-1 may function together with CFZ-2 in directing CAN cell migrations. This suggests that at least two signaling pathways direct migration of CANs. In addition, we found that all or most Wnts direct migrations of some cells (for example, HSNs and CANs) but only two Wnts and one Frizzled appear to be involved in ALM migrations, suggesting a more specific Wnt/Frizzled binding in this process. Comprehensive study is needed to determine C. elegans Wnt/Frizzled binding specificity. Attempts to identify Wnt-binding partners have been reported (Green et al. 2007). However, Wnt/Receptor-binding preferences remain poorly understood.

In some cases, mutating one Wnt gene suppressed the cell migration defects produced by mutation of another. For example, the CAN migration defects of cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 mutants are partially suppressed by a mutation in lin-44. Similarly, the BDU migration defects of cwn-1; cwn-2 mutants are suppressed by egl-20 or egl-20; lin-44 mutations. For both QR.d and QL.d migrations, mutation in lin-44 antagonized the effects of egl-20 mutation. These results suggest that some Wnts act antagonistically to one another in cell migration. How might a single Wnt antagonize other Wnts for some of the cells but not others? Perhaps Wnts act via different mechanisms for specific cell migrations. For example, discrete downstream signaling cascades could be activated due to differential expression of specific Wnt receptors in specific neurons.

Wnt expression and function:

Determination of where Wnt proteins are expressed provides clues to Wnt function. Wnt expression has been assessed using reporter transgenes. CWN-1, EGL-20, and LIN-44 are expressed primarily in the posterior of the animal (Herman et al. 1995; Inoue et al. 2004; Gleason et al. 2006; Pan et al. 2006). EGL-20 protein forms a declining posterior-to-anterior gradient (Coudreuse et al. 2006) and could be observed as far anterior as the midbody of embryos (Pan et al. 2006). Faint and inconsistent expression of LIN-44 also was seen in the middle of the animal (Inoue et al. 2004). CWN-2 is expressed throughout much of the animal (Gleason et al. 2006) and MOM-2 is expressed in several cells in the middle of the animal (Inoue et al. 2004).

How do Wnts with restricted posterior expression exert their influence on cells that are born in or near the head of the animal? For example, the CAN cell is born at the anterior end of the embryo, from which it migrates posteriorly to the middle (Sulston et al. 1983). Two of the Wnts implicated in controlling CAN cell migration, CWN-1 and EGL-20, are expressed in the tail. How do posteriorly restricted CWN-1 and EGL-20 influence CAN cell migration? We can imagine at least three scenarios to explain this. First, CWN-1 and EGL-20 may diffuse the length of the embryo to participate in CAN cell migration. Second, perhaps these Wnts are expressed at low levels from more anteriorly located cells and these sites of expression are key to CAN cell migration. Third, perhaps posteriorly expressed CWN-1 and EGL-20 diffuse anteriorly to influence fates of cells located in the middle of the animal. These cells in turn provide cues that direct CAN cell migrations. Definitively identifying sites of Wnt function through rescue or mosaic experiments will help in understanding the role of Wnts in directing cell migrations.

Wnt/Fz function in Q-cell migration:

Mutations in egl-20, mig-1, and lin-17 transform QL fate to a QR-like fate (Harris et al. 1996; Maloof et al. 1999). In the absence of these proteins, QLs behave like QRs and migrate anteriorly. Loss of additional Wnts shifts QL.d farther to the posterior. Posterior migration of QLs depends on mab-5 expression (Harris et al. 1996; Maloof et al. 1999). In egl-20 mutants, QLs migrate anteriorly because they no longer express mab-5 (Harris et al. 1996; Maloof et al. 1999). Mutation in cwn-1 and/or cwn-2 did not affect expression of a mab-5∷gfp reporter (not shown).

Overall, cell positions of QR.d and QL.d are similar in egl-20, mig-1, or lin-17 mutants, but QL.d are generally found more posteriorly. If egl-20 mutations transform QL to a QR-like fate, then why are they not positioned identically in egl-20 mutants? Several models could explain this phenomenon. While born in identical positions on each side of the animal, QLs polarize toward the posterior, whereas QRs polarize toward the anterior. This polarization event is believed to be guided by mechanisms separate from the ones that direct Q-cell migrations (Honigberg and Kenyon 2000). Therefore, QLs start their migrations at a position more posterior to that of QRs and therefore end up in more posterior positions. Another possibility is that transformed QL cells do not fully adopt a QR-like fate.

Role of CAM-1 in Wnt signaling:

cam-1, a Ror/RTK homolog, has been shown to negatively regulate EGL-20 signaling in HSN migrations and EGL-20 and CWN-1 signaling in vulval development (Forrester et al. 2004; Green et al. 2007). CAM-1 can bind CWN-1 and EGL-20 (Green et al. 2007). Our genetic data show that mutation of cam-1 in cwn-1 or cwn-2 mutant animals did not enhance or suppress the CAN migration defects. We envision two plausible explanations for this result. First, CAM-1 may modulate CWN-1 and CWN-2 activity in a manner similar to its function as an EGL-20-sequestering molecule (Forrester et al. 2004; Green et al. 2007). In this scenario, too little or too much Wnt results in a CAN migration defect. Alternatively, CAM-1 may function in one pathway with CWN-1 and CWN-2 as a coreceptor for one or more Frizzleds. Interestingly, Rors interact with Frizzleds (Hikasa et al. 2002; Oishi et al. 2003), and Frizzled receptors can dimerize (Carron et al. 2003). In this scenario, CAM-1 may function in parallel to CFZ-2 and with CWN-1 and CWN-2 to promote CAN cell migrations. However, no Frizzled mutants display a CAN defect as penetrant as the one seen in cam-1 mutants. Furthermore, CAM-1's cell migration function does not require its intracellular domain (Kim and Forrester 2003). The same two models apply to CAM-1 function in ALM migration, with one exception: CAM-1 might function with CWN-1 but in parallel to CWN-2 in directing this process.

Phenotypic differences between Wnt and candidate receptor mutants:

An interesting finding of the studies presented here is that loss of Frizzleds generally results in phenotypes weaker than those caused by loss of Wnts. For example, mutations in cwn-1; egl-20 cwn-2 produced more severe CAN and ALM migration defects than mutation of all four Frizzleds. Mutation of the Wnt receptor lin-18, alone or in combination with other Frizzled mutations, does not cause significant migration defects for most cells. These results raise the possibility that additional yet unidentified Wnt receptors exist. Unfortunately, we were unable to look at animals lacking all four Frizzleds and LIN-18, leaving this possibility unexplored. Finally, because Frizzled quadruple-mutant animals were progeny of triply heterozygous mothers, perhaps maternally provided protein was sufficient to guide migrating cells to their wild-type positions. Interestingly, mutation of Frizzled genes affected Q-cell lineages whereas mutation of Wnts did not (not shown), revealing a possible Wnt-independent function of Frizzleds.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, Craig Mello, David Eisenmann, and Gian Garriga for providing strains. We thank Hisako Takeshita for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HD37815 to W.C.F. and by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to H.S.

References

- Bhanot, P., M. Brink, C. H. Samos, J. C. Hsieh, Y. Wang et al., 1996. A new member of the frizzled family from Drosophila functions as a Wingless receptor. Nature 382 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carron, C., A. Pascal, A. Djiane, J. C. Boucaut, D. L. Shi et al., 2003. Frizzled receptor dimerization is sufficient to activate the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. J. Cell Sci. 116 2541–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S. G., and C. Chiu, 2003. C. elegans ZAG-1, a Zn-finger-homeodomain protein, regulates axonal development and neuronal differentiation. Development 130 3781–3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M., W. Raich, C. Agbunag, B. Leung, J. Hardin et al., 1998. A putative catenin-cadherin system mediates morphogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans embryo. J. Cell Biol. 141 297–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coudreuse, D. Y., G. Roel, M. C. Betist, O. Destree and H. C. Korswagen, 2006. Wnt gradient formation requires retromer function in Wnt-producing cells. Science 312 921–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann, C. E., J. C. Hsieh, A. Rattner, D. Sharma, J. Nathans et al., 2001. Insights into Wnt binding and signalling from the structures of two Frizzled cysteine-rich domains. Nature 412 86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, W. C., and G. Garriga, 1997. Genes necessary for C. elegans cell and growth cone migrations. Development 124 1831–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, W. C., M. Dell, E. Perens and G. Garriga, 1999. A C. elegans Ror receptor tyrosine kinase regulates cell motility and asymmetric cell division. Nature 400 881–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, W. C., C. Kim and G. Garriga, 2004. The Caenorhabditis elegans Ror RTK CAM-1 inhibits EGL-20/Wnt signaling in cell migration. Genetics 168 1951–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, J. E., E. A. Szyleyko and D. M. Eisenmann, 2006. Multiple redundant Wnt signaling components function in two processes during C. elegans vulval development. Dev. Biol. 298 442–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, M. D., and R. Nusse, 2006. Wnt signaling: multiple pathways, multiple receptors, and multiple transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 281 22429–22433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. L., T. Inoue and P. W. Sternberg, 2007. The C. elegans ROR receptor tyrosine kinase, CAM-1, non-autonomously inhibits the Wnt pathway. Development 134 4053–4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J., L. Honigberg, N. Robinson and C. Kenyon, 1996. Neuronal cell migration in C. elegans: regulation of Hox gene expression and cell position. Development 122 3117–3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock, E. M., J. G. Culotti, D. H. Hall and B. D. Stern, 1987. Genetics of cell and axon migrations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 100 365–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, M. A., 2002. Control of cell polarity by noncanonical Wnt signaling in C. elegans. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 13 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, M. A., and H. R. Horvitz, 1994. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene lin-44 controls the polarity of asymmetric cell divisions. Development 120 1035–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman, M. A., L. L. Vassilieva, H. R. Horvitz, J. E. Shaw and R. K. Herman, 1995. The C. elegans gene lin-44, which controls the polarity of certain asymmetric cell divisions, encodes a Wnt protein and acts cell nonautonomously. Cell 83 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikasa, H., M. Shibata, I. Hiratani and M. Taira, 2002. The Xenopus receptor tyrosine kinase Xror2 modulates morphogenetic movements of the axial mesoderm and neuroectoderm via Wnt signaling. Development 129 5227–5239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard, M. A., and C. I. Bargmann, 2006. Wnt signals and frizzled activity orient anterior-posterior axon outgrowth in C. elegans. Dev. Cell 10 379–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg, L., and C. Kenyon, 2000. Establishment of left/right asymmetry in neuroblast migration by UNC-40/DCC, UNC-73/Trio and DPY-19 proteins in C. elegans. Development 127 4655–4668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, J. C., A. Rattner, P. M. Smallwood and J. Nathans, 1999. Biochemical characterization of Wnt-frizzled interactions using a soluble, biologically active vertebrate Wnt protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 3546–3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, T., H. S. Oz, D. Wiland, S. Gharib, R. Deshpande et al., 2004. C. elegans LIN-18 is a Ryk ortholog and functions in parallel to LIN-17/Frizzled in Wnt signaling. Cell 118 795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C., and W. C. Forrester, 2003. Functional analysis of the domains of the C elegans Ror receptor tyrosine kinase CAM-1. Dev. Biol. 264 376–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga, M., M. Take-uchi, T. Tameishi and Y. Ohshima, 1999. Control of DAF-7 TGF-(alpha) expression and neuronal process development by a receptor tyrosine kinase KIN-8 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 126 5387–5398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korswagen, H. C., 2002. Canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways in Caenorhabditis elegans: variations on a common signaling theme. BioEssays 24 801–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korswagen, H. C., M. A. Herman and H. C. Clevers, 2000. Distinct beta-catenins mediate adhesion and signalling functions in C. elegans. Nature 406 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan, C. Y., and R. Nusse, 2004. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20 781–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloof, J. N., J. Whangbo, J. M. Harris, G. D. Jongeward and C. Kenyon, 1999. A Wnt signaling pathway controls hox gene expression and neuroblast migration in C. elegans. Development 126 37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikels, A. J., and R. Nusse, 2006. Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits beta-catenin-TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol. 4 e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse, R., 2005. Wnt signaling in disease and in development. Cell Res. 15 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, I., H. Suzuki, N. Onishi, R. Takada, S. Kani et al., 2003. The receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2 is involved in non-canonical Wnt5a/JNK signalling pathway. Genes Cells 8 645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, C. L., J. E. Howell, S. G. Clark, M. Hilliard, S. Cordes et al., 2006. Multiple Wnts and frizzled receptors regulate anteriorly directed cell and growth cone migrations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Cell 10 367–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau, C. E., W. D. Downs, R. Lin, C. Wittmann, Y. Bei et al., 1997. Wnt signaling and an APC-related gene specify endoderm in early C. elegans embryos. Cell 90 707–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruvkun, G., and O. Hobert, 1998. The taxonomy of developmental control in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 282 2033–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salser, S. J., and C. Kenyon, 1992. Activation of a C. elegans Antennapedia homologue in migrating cells controls their direction of migration. Nature 355 255–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa, H., L. Lobel and H. R. Horvitz, 1996. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene lin-17, which is required for certain asymmetric cell divisions, encodes a putative seven-transmembrane protein similar to the Drosophila frizzled protein. Genes Dev. 10 2189–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleford, G. M., S. Shivakumar, L. Shiue, J. Mason, C. Kenyon et al., 1993. Two wnt genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Oncogene 8 1857–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhankova, M., and H. C. Korswagen, 2007. Migration of neuronal cells along the anterior-posterior body axis of C. elegans: Wnts are in control. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 17 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston, J. E., and H. R. Horvitz, 1977. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 56 110–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston, J. E., E. Schierenberg, J. G. White and J. N. Thomson, 1983. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 100 64–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, C. J., A. Schlesinger, J. C. Carter and B. Bowerman, 1997. Wnt signaling polarizes an early C. elegans blastomere to distinguish endoderm from mesoderm. Cell 90 695–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whangbo, J., and C. Kenyon, 1999. A Wnt signaling system that specifies two patterns of cell migration in C. elegans. Mol. Cell 4 851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, S., R. D. McKinnon, M. Kokel and J. B. Thomas, 2003. Wnt-mediated axon guidance via the Drosophila Derailed receptor. Nature 422 583–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinovyeva, A. Y., and W. C. Forrester, 2005. The C. elegans Frizzled CFZ-2 is required for cell migration and interacts with multiple Wnt signaling pathways. Dev. Biol. 285 447–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]