Abstract

B cell receptors have been shown to cluster at the intercellular junction between a B cell and an antigen-presenting cell in the form of a segregated pattern of B cell receptor/antigen complexes known as an immunological synapse. We use random walk-based theoretical arguments and Monte Carlo simulations to study the effect of diffusion of surface-bound molecules on B cell synapse formation. Our results show that B cell synapse formation is optimal for a limited range of receptor-ligand complex diffusion coefficient values, typically one-to-two orders of magnitude lower than the diffusion coefficient of free receptors. Such lower mobility of receptor-ligand complexes can significantly affect the diffusion of a tagged receptor or ligand in an affinity dependent manner, as the binding/unbinding of such receptor or ligand molecules crucially depends on affinity. Our work shows how single molecule tracking experiments can be used to estimate the order of magnitude of the diffusion coefficient of receptor-ligand complexes, which is difficult to measure directly in experiments due to the finite lifetime of receptor-ligand bonds. We also show how such antigen movement data at the single molecule level can provide insight into the B cell synapse formation mechanism. Thus, our results can guide further single molecule tracking experiments to elucidate the synapse formation mechanism in B cells, and potentially in other immune cells.

INTRODUCTION

Many important physiological processes are mediated by the binding of receptor molecules to ligands and the formation of receptor-ligand signaling complexes (1). In the immune system, the binding of antigen ligands by lymphocyte receptors, namely the T cell and B cell receptors (TCR and BCR, respectively), is the principal mechanism by which lymphocytes recognize antigen. During this process, it has been observed that the receptor/antigen complexes cluster at the center of the contact zone between the lymphocyte and the antigen presenting cell while excluding other surface molecules, forming a visible segregation pattern known as the “immunological synapse” (2–9). The clustering of receptor/antigen complexes in the immunological synapse is thought to enhance signaling (10,11). The immunological synapse pattern was first observed in T cells (2–5), and subsequently was also observed in B cells (6–9).

Given its significance and complexity, many studies have been conducted to fully understand the mechanisms of immunological synapse formation in lymphocytes (12–23). Several of these studies, including our own work on B cell synapse formation (21), show that diffusion of receptor/ligand complexes is important in immunological synapse formation (12,13,15,19–21,24). Indeed, diffusion is the primary mechanism by which receptors and receptor-ligand complexes translocate within the cell membrane (25). However, the effect of receptor-ligand complex diffusion on synapse formation remains largely unknown. Recently, pioneering single molecule tracking experiments carried out by the Pierce group measured diffusion of receptor molecules at the single molecule level during the course of B cell synapse formation (26). However, the same cannot be done easily for receptor-ligand complexes (e.g., B cell receptor/antigen [BCR/Ag] complexes) due to their finite bond lifetime. Hence, computational and theoretical approaches are necessary to establish a relation between the diffusion of free receptors and the diffusion of receptor-ligand complexes. Such a theoretical approach can potentially elucidate the synapse formation mechanism in B cells, as antigen mobility can differ depending on the precise mechanism of synapse formation.

In this study, we have used theoretical arguments and a detailed Monte Carlo simulation procedure to investigate synapse formation in B cells to focus exclusively on the role of diffusion in synapse formation (21). Monte Carlo methods are ideally suited to study systems involving receptor segregation and pattern formation, as the number of molecules may be small (as little as ∼100) and spatial heterogeneity and exclusion effects are important (21,23,27–29). Although the diffusion coefficient of receptor-ligand complexes is difficult to determine in vivo, it is generally believed to be lower than that of free receptor molecules (13,20,30–33). Our results clearly show that an order of magnitude difference in mobility between free and complex molecules is crucial to synapse formation in B cells. Given the difficulty of measuring the diffusion coefficient of receptor-ligand complexes directly, we propose an indirect method that relies on tracking individual antigen molecules.

Our method is based on measuring the mean-square distance an antigen molecule has traveled from its original location as receptor-ligand affinity is varied. If receptor-ligand complexes are as mobile as free molecules, we would expect little decrease in the mean-square distance traveled as affinity increases. However, if the diffusion coefficient of receptor-ligand complexes is significantly lower (∼an order of magnitude or more) than that of free molecules, the mean-square distance traveled by the antigen molecule will decrease as binding affinity increases. We have found a nonlinear relationship between the mean-square displacement of antigen molecules and time, indicating subdiffusive behavior. Such a result can be readily used to estimate the diffusion coefficient of membrane-bound complex molecules from that of free molecules. More importantly, the information gathered from antigen diffusion at the single molecule level can be used to probe the nature of the B cell synapse pattern and its formation mechanism.

METHOD

Our stochastic simulation scheme belongs to the kinetic Monte Carlo class of methods (27). Individual molecules are randomly sampled to undergo diffusion or reaction with given probabilistic rates. One long-standing issue in the design of such stochastic simulations is that the simulation timescale is often arbitrary, providing limited opportunities for comparing the simulation results with data obtained from biological experiments (23). One rudimentary way of choosing the size of the time step in stochastic simulations is to match the simulation timescale with the already-known timescale of the relevant biological process (23). Instead of this approach, in our method the size of the simulation time step is set by matching the diffusion coefficient obtained from a low density, random-walk simulation to experimentally measured diffusion coefficient values. This does not guarantee that the timescale of a simulation of a complex biological process involving several species and large numbers of reacting molecules will match the timescale of diffusion of a single species at low density. However, the timescale of immunological synapse formation that emerged from our simulation due to the collective diffusion and reaction of a large number of molecules was comparable to that of biological experiments.

Model setup

Our modeling procedure is based on that described in (21). The system we model is a B cell-lipid bilayer system such as the one used in B cell synapse formation experiments (6–9). We model a 3 μm × 3 μm square area on the bilayer surface and its vertical projection on the cell surface, as shown in Fig. 1. This area is substantially larger than the region where the vertical distance between the cell and the bilayer, z, is small enough for receptor-ligand binding to occur. This area is also believed to be large enough so that a zero net flux condition can be assumed to exist at the boundaries, which in our model is simulated by means of fully reflecting boundaries. The cell membranes are modeled as discrete Cartesian lattices consisting of an N*N grid of nodes. We assume the B cell membrane initially has a spherical curvature (to minimize free energy) so that the vertical separation distance z between the two surfaces at any given point (x, y) is given by:

|

(1) |

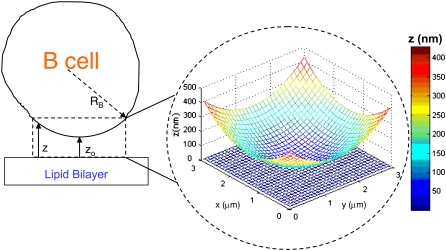

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of the cell-bilayer system simulated in our model. The bilayer and cell surfaces are modeled as N*N Cartesian lattices. We use a lattice spacing of 10 nm and simulate a 3 μm × 3 μm area on the bilayer and its projection on the cell surface. The initial vertical separation distance z(x,y) is given by Eq. 1. The 3 μm × 3 μm simulated area is chosen to include the entire area where z is small enough for receptor-ligand binding to be physically possible.

Only one molecule can occupy a node in our simulation, so we choose a nodal spacing equal to a membrane protein molecule's exclusion radius, ∼10 nm (resulting in N = 300 nodes). The exception are BCR molecules, which being bivalent, have a width of ∼25 nm (34,35) and thus occupy three nodes, with either a horizontal or vertical orientation on the lattice. For the radius of B lymphocytes we use RB = 6 μm and z0 = 40 nm.

At the start of a simulation run, molecules are uniformly distributed over the two surfaces at random. The molecular species represented are BCR and lymphocyte function activated antigen-1 (LFA-1) on the B cell surface and their binding partners, antigen and Intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), on the bilayer surface. At every time step in the simulation, molecules from the population are individually sampled at random to attempt either diffusion or reaction events, determined by means of a coin toss with probability 0.5.

Reaction move

If a molecule has been selected to undergo a reaction, the first step is to check the same node on the opposite surface for a binding partner. If that is the case, a random number trial with probability pon(i) is carried out to determine if the two molecules will bind and form a receptor-ligand complex. BCR molecules are able to bind up to two antigen molecules, one on each end node (but not the middle node). If a free BCR molecule is selected for a reaction, an additional coin toss is carried out to pick one of the end nodes, and the bilayer surface opposite the chosen node is checked for a free antigen molecule. Sometimes a BCR molecule may have bound an antigen molecule on one Fab (Fragment, antigen binding) domain and have the other Fab domain free, forming a BCR/Ag complex. If the free Fab domain is selected, the reaction proceeds as described above, which may result in a second antigen molecule binding to the BCR/Ag complex (forming a BCR/Ag2 complex), whereas if the Fab domain with the bound antigen is selected, the BCR/Ag complex may dissociate into its component molecules with probability poff(i). Three reversible reactions are thus possible: LFA-1 + ICAM-1 ↔ LFA-1/ICAM-1, BCR + Ag ↔ BCR/Ag, and BCR/Ag + Ag ↔ BCR/Ag2. The binding and dissociation probabilities for the two reactions involving antigen are assumed to be the same and thus the subscript i refers to the BCR/Ag reactions when i = BA and the LFA-1/ICAM-1 reaction when i= LI. We also used a different binding/dissociation probability for binding to the second Fab domain, without any qualitative changes in our results.

We assume the probability of bond formation, pon(i), and bond dissociation, poff(i), depends on the intermembrane distance z in accordance with the well-known linear spring model (1,21,36,37). Because pon(i) and poff(i) are analogous to kon and koff, we can define the probabilistic analog to the association constant KA, denoted by PA, as the ratio pon(i)/poff(i):

|

(2) |

The quantity PA(i)(z) defined in Eq. 2 denotes the overall receptor-ligand affinity, which consists of both the intrinsic affinity  and the bond stiffness κi. Individually varying

and the bond stiffness κi. Individually varying  and

and  while keeping the ratio

while keeping the ratio  constant changes the timescale of the simulation, but not the equilibrium behavior. The intrinsic affinity

constant changes the timescale of the simulation, but not the equilibrium behavior. The intrinsic affinity  corresponds most closely to the quantity KA and the mapping between KA, kon, koff and

corresponds most closely to the quantity KA and the mapping between KA, kon, koff and  respectively, is given in Tsourkas et al. (21).

respectively, is given in Tsourkas et al. (21).

Diffusion move

On the other hand, if a molecule has been selected to undergo diffusion, a random number trial with probability pdiff(i) is used to determine if the diffusion move will occur successfully. If the trial is successful, one of the four neighboring nodes is selected at random for the molecule to diffuse to. Because two molecules are not allowed to occupy the same node, the molecule will only move if the appropriate node(s) are unoccupied. For example, three nodes need to be free for a BCR molecule to diffuse in the direction transverse to its length, whereas only one free node is needed for it to diffuse along its length. In the case of complexes, the appropriate nodes on both surfaces need to be free (two nodes for monomeric LFA-1/ICAM-1 complexes, two or four for BCR/Ag complexes, and three or five for BCR/Ag2 complexes).

Sampling and time step size

In our algorithm, a number S of diffusion/reaction trials is carried out during every time step. The number of trials S is set equal to the total number of molecules (free and complexes) present in the system at the beginning of each time step, and the simulation is run for a number of time steps T. A schematic of our Monte Carlo algorithm is shown in Fig. 2. The mapping between our model's timescale and physical time is given in (21). We use a time step of 10−3 s and the simulation is run for T = 105 steps, i.e., 100 s. This is broadly in agreement with the timescale of B cell synapse formation observed in imaging experiments (6–9). The Monte Carlo code is written in the C programming language and run on a Linux Beowulf cluster (PSSC Labs, Lake Forest, CA). Each run of our simulation takes <5 min on a cluster node.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of the Monte Carlo model.

Parameter values

The parameters used in our model are listed in Table 1. Parameter values found in the literature are given on the left side of Table 1, whereas the appropriately mapped forms used in our model are listed on the right side of Table 1 (21). Parameters whose values vary during experiments (such as BCR/Ag affinity) or whose values are unknown (such as the diffusion coefficient of receptor-ligand complexes) are those that we vary in our simulations.

TABLE 1.

Experimentally measured parameter values and their probabilistic counterparts

| Experimental parameter | Measured value | Simulation parameter | Mapped value |

|---|---|---|---|

| KA BCR/Ag | 106–1011 M−1 (7,8) |  |

102–107 |

| kon BCR/Ag | 106 M−1s−1 (7,8) |  |

0.1 |

| koff BCR/Ag | 1–10−5 s−1 (7,8) |  |

10−3–10−8 |

| KA LFA-1/ICAM-1 | 3.3 μm2/mol (38) |  |

103 |

| kon LFA-1/ICAM-1 | 0.33 μm2 · s−1/mol (38) |  |

0.1 |

| koff LFA-1/ICAM-1 | 0.1 s−1 (38) |  |

10−4 |

| BCR molecules/cell | ∼105 (13,21,37) | B0 | 3000 molecules |

| LFA-1 molecules/cell | ∼105 (13,21,37) | L0 | 3000 molecules |

| Antigen concentration | ∼100 mol/μm2 (7) | A0 | 1000 molecules |

| ICAM-1 concentration | 170 mol/μm2 (7) | I0 | 2000 molecules |

| κLI | 40 μN/m (13) | κLI | Same as measured value |

| κBA | Unknown, taken as κLI | κBA | Same as measured value |

| zeq(LI) | 42 nm (13) | zeq(LI) | Same as measured value |

| zeq(BA) | ∼40 nm (6,32,33) | zeq(BA) | Same as measured value |

| Dfree molecules | ∼0.1 μm2/sec (38) | pdiff(F) | 1.0 |

| Dcomplexes | Unknown, varied | Pdiff(C) | 1–10−3 |

The diffusion coefficient of free receptor molecules in a cell membrane is in the range of ∼0.01–0.1 μm2/sec (12,13,39). We thus collectively group the individual diffusion probabilities of the free molecule species in Table 1 (pdiff(B), pdiff(A), pdiff(L), pdiff(I)) into a single parameter pdiff(F), and likewise group the individual diffusion probabilities of the complexes, pdiff(BA) and pdiff(LI), into a single parameter pdiff(C). Because the upper bound of the diffusion coefficient of free molecules is of the order of 0.1 μm2/sec, we set that value to correspond to pdiff(F) = 1.0 (21), whereas pdiff(C) is assumed to be unknown and therefore variable (although it cannot exceed pdiff(F)).

RESULTS

Theoretical model

Mapping to a continuous time random walk problem with given waiting time distribution

Diffusion of BCR molecules on the B cell surface can be mapped to an effective random-walk problem with a given waiting time distribution that arises from binding with antigen molecules on an apposing antigen-presenting cell surface. The waiting time distribution can be obtained by assuming that receptors can diffuse only when they are not bound to any ligands, which are taken to be immobile. We can calculate the probability P(n) that a receptor molecule that is initially bound with an antigen and diffuses for the first time at step n. P(n) is given by a sum of all possible ways a receptor can go through a series of binding-unbinding reactions to finally unbind at step (n−1) and then diffuse for the first time at step n. The terms in P(n) are going to be dominated by the term ∼P(n) ∼ (1−Poff)n ∼ exp[−αt], with α = −ln(1−Poff)/τ. The constant τ = t/n arises from mapping the discrete step n to a continuous time t.

For flat cell-to-cell contact area, Poff is a constant leading to an exponentially distributed P(t) arising due to BCR-antigen binding. Hence the waiting time distribution for the effective random walk diffusion is also exponentially distributed. Details of the derivation of the waiting time distribution and the mapping to an effective random walk problem will be described in a separate manuscript (S. Raychaudhuri and P. Tsourkas, unpublished). The continuous time random walk diffusion with a given waiting time distribution can be solved using Fourier-Laplace transform of the space-time variables to yield the probability distribution of the displacement (40):

|

(3) |

The quantity ψ(s) is the Laplace transform of the waiting time distribution and p(ω) is the Fourier transform of the step size distribution of a given random walk. For an exponential waiting time distribution, the mean-square displacement is linear with time, indicating diffusive behavior. In the case of any directed transport of BCR molecules, diffusive scaling can be masked by the leading displacement ∼ time behavior of directed BCR motion. Thus, studying the mean-square displacement of receptor diffusion can elucidate the essential molecular mechanism of immune synapse formation.

If the cells are assumed to be spherical (or with some curvature), the binding-unbinding constants (Pon/Poff) become position dependent. In such a scenario, the waiting time distribution also acquires a spatial dependence. For cell-cell contacts with spherical cell shapes, such spatial dependence of the waiting time distribution is nonlinear. Hence, our random walk model with spatially dependent waiting time essentially captures diffusion of receptor molecules in a nonlinear confining potential that arises due to binding with ligands at a curved cell-cell contact area. A random walk in such a nonlinear potential leads to subdiffusive behavior for biologically relevant timescales and hence pure diffusion (mean-square displacement varying linearly with time) may not be observed in experiments (40). Hence, we can use the time of synapse formation as a cut-off at which the mean-square displacement is calculated for various affinity antigens. The mean-square displacement at the preset cut-off time will be affinity-dependent if the synapse formation mechanism is dominated by pure diffusion and binding of antigens. Some of the results of our random walk model are corroborated by a detailed kinetic Monte Carlo model of receptor diffusion. One advantage of using such a Monte Carlo model is that it can easily incorporate additional complexities such as mobility of antigens or BCR-antigen complexes and crowding effects and hence matches the experimental situation more closely.

Monte Carlo simulations

The diffusion of receptor-ligand complexes is a key factor in synapse formation mechanism

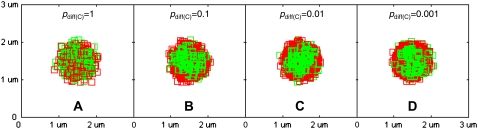

We first investigate the effect of the diffusion probability of receptor-ligand complexes (pdiff(C)) on synapse formation, shown in Fig. 3. In the Figure, we see that synapse formation is optimal for pdiff(C) = 0.1 and 0.01 (Fig. 3, B and C). Significant deterioration in synapse quality is observed when the diffusion probability of receptor-ligand complexes is equal to that of free molecules (pdiff(C) = 1, Fig. 3 A). As an objective measure of synapse formation, we tabulate the mean radial distance (in μm) from the center the contact zone of BCR/Ag complexes and LFA-1/ICAM-1 complexes in Table 2.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of receptor-ligand complex mobility on immune synapse formation. BCR/Antigen complexes are shown in green and LFA-1/ICAM-1 complexes in red. In this set of images, the diffusion probability of receptor ligand complexes, pdiff(C), directly analogous to the diffusion coefficient, D, is varied across orders of magnitude from pdiff(C) = 1 to pdiff(C) = 10−4, whereas the diffusion probability of receptor ligand complexes is fixed at pdiff(F) = 1. High complex mobility is detrimental to synapse formation (A). These patterns were obtained after 105 time steps (t = 100 s) with the parameter values given in Table 1.

TABLE 2.

Mean distance of receptor-ligand complexes from the center (in μm) as a function of diffusion probability (pdiff(C))

| pdiff(C) = 1 | pdiff(C) = 0.1 | pdiff(C) = 0.01 | pdiff(C) = 0.001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCR/Ag | 0.305 | 0.272 | 0.258 | 0.258 |

| LFA-1/ICAM-1 | 0.327 | 0.295 | 0.284 | 0.287 |

The detrimental effect of high receptor-ligand complex diffusion coefficient on synapse formation can be explained as follows: in our simulations, segregation of BCR/Ag and LFA-1/ICAM-1 complexes is driven mainly by the difference in poff(i) between the two reactions (21), or equivalently, by the differences in the free energy of bond formation. In the case of synapse formation, the decrease in entropy due to the clustering and segregation of receptor-ligand complexes is balanced by the decrease in free energy associated with receptor-ligand binding (Supplementary Material in Tsourkas et al. (21)). Changes in entropy are primarily associated with the diffusion coefficient, whereas free energy is primarily determined by affinity (PA(i)), with higher affinity corresponding to higher free energy. Thus, if receptor-ligand complexes are highly mobile, entropic factors will prevail and an ordered pattern such as an immunological synapse will not form.

Tracking individual antigen molecules can reveal the mobility of BCR/Ag complexes and help elucidate the mechanism of B cell synapse formation

Given the importance of the diffusion coefficient of receptor-ligand complexes in synapse formation, and the difficulty of measuring it directly in physical experiments, we used our simulation to devise an indirect method for estimating it. We track an individual antigen molecule for the duration of a simulation run and record the square of the distance (R2) it has traveled from its starting position at every 100 time steps. This is shown in Fig. 4, where we plot the trajectory (Fig. 4, A and D) and R2(t) (Fig. 4, C and F) for four antigen molecules for both high BCR affinity (KA = 1011 M−1; Fig. 4, A–C) and low BCR affinity (KA = 106 M−1; Fig. 4, D–F). Also shown is the corresponding segregation pattern formed by the receptor-ligand complexes (Fig. 4, B and E). In these simulations we have set pdiff(C) = 0.1 and pdiff(F) = 1.0, so that antigen binding events are reflected in the plot of R2(t). When the antigen molecule is outside the zone where binding is possible (Fig. 4, black circle), the value of R2(t) varies rapidly over time because the molecule is in the free state (pdiff(F) = 1.0). As soon as the antigen binds to a BCR, however, the mobility of the molecule decreases by an order of magnitude and the variation in R2(t) over time becomes considerably slower.

FIGURE 4.

Plots of the trajectories of four individual antigen molecules (A and D), the resulting segregation patterns formed by the receptor-ligand complexes (B and E) and the square of the distance each antigen molecule has covered (C and F). A–C represent high BCR affinity (KA = 1011 M−1) whereas D–F represent low BCR affinity (KA = 106 M−1). In (A and D), black stars represent the start of the trajectory and red stars represent the end of the trajectory. Each antigen molecule trajectory in (A and D) corresponds to an R2(t) plot in (C and F). The inversion in the canonical synapse pattern in (B) is due to differences in koff between BCR/Ag and LFA-1/ICAM-1 (21). The plots were obtained after 105 time steps (t = 100 s), with pdiff(C) = 0.1, pdiff(F) = 1, and the remaining parameters as given in Table 1.

In the high affinity case (Fig. 4, A–C), the antigen molecule whose trajectory is traced in pink is bound to a BCR almost from the beginning, and hence its R2(t) value increases very little over time. The antigen molecule whose trajectory is denoted in green never binds to a BCR and thus R2(t) for this molecule varies rapidly over time. In the remaining two tracks, the antigen molecule initially starts outside the zone of binding, drifts toward the center, and subsequently binds to a BCR. Accordingly, the trajectories are initially noisy and level off after binding. Because BCR/Ag affinity in this case is higher than LFA-1/ICAM-1 affinity and the two species have the same bond stiffness, the segregation pattern is the inverse of the canonical synapse pattern (21).

For the low affinity case (Fig. 4, D–F), in two tracks (beige, green) the antigen molecule starts outside the zone of binding and eventually diffuses inside and binds a BCR, whereas in the remaining two tracks (pink, cyan), the antigen molecule also starts outside, binds a BCR, but then diffuses all the way to the edge of the contact zone and eventually unbinds. The value of R2(t) after binding varies more rapidly than the high affinity case because there are more unbinding and rebinding events after the initial binding event (poff = 10−8 for Fig. 4, A–C, but poff = 10−3 for Fig. 4, D–F).

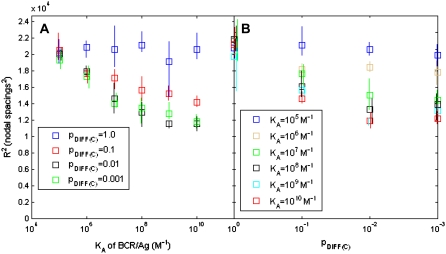

From Fig. 4, we thus see that R2(t) is strongly affected by the value of BCR/Ag affinity. We deduce that it would in fact be possible to estimate the value of pdiff(C) if we could measure the value of R2(t) in experiments in which the value of BCR affinity is known. Because the value of R2(t) can vary greatly between trials, it is necessary to obtain R2(t) from the average of a large number of trials. In Fig. 5, we plot 〈R2(t)〉, obtained by averaging the trajectories of 1000 antigen molecules, whereas BCR affinity is varied from KA = 106 M−1 to 1010 M−1. In the case of pdiff(C) = 1 (Fig. 5 A), there is little variation in the final value of R2(t) as BCR/Ag affinity is varied across four orders of magnitude. This is to be expected as pdiff = 1 regardless of whether the tracked antigen molecule is free or bound, and thus varying affinity will have no effect on 〈R2(t)〉. The situation is markedly different when pdiff(C) = 0.1 (Fig. 5 B), where we see a clear decrease in the final value of 〈R2(t)〉 as affinity increases. Again, this is expected as increasing affinity means an increase in the mean time the antigen molecule stays bound, which in turn implies more time spent in the pdiff = 0.1 regime. As noted in our theoretical analysis of an effective random walk model, a curvature dependent nonlinear potential due to receptor-ligand binding at the cell-bilayer contact can lead to subdiffusive behavior of receptor molecules during B cell synapse formation. In our synapse formation simulations, we do not observe diffusive behavior (Fig. 5). We use the final values of 〈R2(t)〉 for typical synaptic pattern formation timescales (shown in Fig. 4) as a measure of mobility.

FIGURE 5.

Plots of R2(t) obtained from averaging 1000 individual trials (such as those in Fig. 4, C and F). BCR affinity was varied from KA = 106 to KA = 1010 M−1. When pdiff(C) = 1, there is little separation among the curves, but when pdiff(C) = 0.1, we clearly see that the final value of R2(t) decreases as affinity increases.

The values of the end points of the curves in Fig. 5 (i.e., the final value of 〈R2(t)〉) are plotted as a function of both BCR/Ag affinity and pdiff(C) in Fig. 6. In Fig. 6 A, we plot the endpoint of 〈R2(t)〉 as a function of affinity and each series corresponds to a fixed value of pdiff(C). From Fig. 6, we see that the final value of 〈R2(t)〉 remains constant with affinity when pdiff(C) = 1, but we also note that it decreases in a nonlinear manner with increasing affinity for pdiff(C) = 0.1, 0.01, and 0.001. We also note the there is not much difference between the latter three cases, particularly between pdiff(C) = 0.01 and 0.001. We believe that these results form a theoretical basis for a method to experimentally determine whether the mobility of receptor-ligand complexes is roughly the same as that of free molecules, or at least an order of magnitude less. If we note the initial and final positions of a large number (∼1000) of antigen molecules in an experimental cell-bilayer system, we can estimate the order of magnitude of the diffusion coefficient of receptor-ligand complexes within an order of magnitude by observing whether or not there is a decrease in the final value of 〈R2(t)〉 as BCR/Ag affinity increases.

FIGURE 6.

Plots of the final value of 〈R2(t)〉 as a function of BCR/Ag affinity (A) and pdiff(C) (B). In (A), each series represents a constant value of pdiff(C). We see that the final value of R2(t) decreases as BCR/Ag affinity increases for pdiff(C) = 10−1–10−3 but remains the same for pdiff(C) = 1. If it were possible to measure the final value of R2 for a large number of antigen molecules as BCR/Ag affinity is varied from KA = 106 to KA = 1010 M−1, it would be possible to determine the order of magnitude of pdiff(C) (and hence the diffusion coefficient of receptor-ligand complexes) by noting whether the final value of R2(t) decreases or remains constant as BCR/Ag affinity increases. In (B), each series represents a constant BCR/Ag affinity value. For low BCR/Ag affinity (105–106 M−1) there is little decrease in the final value of R2(t) as pdiff(C) decreases.

We also plot the final value of 〈R2(t)〉 as a function of pdiff(C) in Fig. 6 B, where each series represents a fixed BCR affinity value. Here, we see that it is impossible to distinguish between values of BCR affinity when pdiff(C) = 1, but as pdiff(C) decreases we note that is increasingly possible to distinguish between affinity values. This is especially true when the probability of diffusion of receptor-ligand complexes is very low (pdiff(C) ≤ 0.01).

The study of diffusion of antigen molecules at the single molecule level can be used to probe the mechanism of B cell synapse formation. Single molecules tracks showed considerable variation as BCR/Antigen affinity was varied, as evidenced in Fig. 4, A and D. Therefore, if it is true that BCR/Antigen affinity determines the nature of the synaptic pattern, as in Fig. 4, B and E, this synapse formation mechanism will also be reflected in the tracks of individual antigen molecules. On the other hand, if B cell synapse formation is not governed by an affinity dependent mechanism, the final 〈R2(t)〉 values should be insensitive to BCR/Antigen affinity. It should be noted that in our simulation, the diffusion of receptor-ligand complexes is spatially dependent, as affinity itself is a function of position (Eq. 2). Therefore, the diffusion of antigens in this case should be very different from cases where synapse formation is mainly driven by a directed transport mechanism.

DISCUSSION

Diffusion plays a critical role in receptor clustering, including B cell immune synapse formation. If the B cell synapse forms primarily by an BCR/antigen affinity dependent mechanism (21), then our results show that receptor-ligand complexes need to diffuse at least an order of magnitude slower than free molecules to synaptic pattern to form. If receptor-ligand complexes are as mobile as free receptors, entropic effects predominate and receptor-ligand complexes do not segregate, and the pattern formed is purely random. Tracking receptor-ligand complexes, however, cannot be done easily in biological experiments due to the finite lifetime of receptor-ligand bonds. It is, however, readily possible to do so in computer simulations. We have found a nonlinear relationship between mean-square displacement of antigen molecules and time. Interestingly, such a nonlinear relationship depends on antigen-affinity only when receptor-ligand complexes diffuse at a slower rate than free molecules. Our results elucidate how tracking antigen molecules at the single molecule level can provide crucial insight into the mechanism of B cell synapse formation. Specifically, a synapse formation mechanism primarily driven by BCR/Antigen affinity leads to distinct antigen molecule trajectories as BCR/antigen affinity is varied.

Acknowledgments

During the course of this study we came to know about single molecule diffusion studies in the context of B cell synapse formation from the Susan Pierce lab at the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Pavel Tolar from the Pierce lab for sharing some of his initial experimental data with us, and for helpful discussions.

Editor: Michael Edidin.

References

- 1.Lauffenburger, D. A., and J. J. Linderman. 1993. Models for binding, trafficking and signaling. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- 2.Wülfing, C., M. D. Sjaastad, and M. M. Davis. 1998. Visualizing the dynamics of T cell activation: Intracellular adhesion molecule 1 migrates rapidly to the T cell/B cell interface and acts to sustain calcium levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:6302–6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monks, C. R., B. A. Freiberg, H. Kupfer, N. Sciaky, and A. Kupfer. 1998. Three-dimensional segregation of supramolecular activation clusters in T cells. Nature. 395:82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grakoui, A., S. K. Bromley, C. Sumen, M. M. Davis, A. S. Shaw, P. M. Allen, and M. L. Dustin. 1999. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science. 285:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krummel, M. F., M. D. Sjaastad, C. Wulfing, and M. M. Davis. 2000. Differential clustering of CD4 and CD3ζ during T cell recognition. Science. 289:1349–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batista, F. D., D. Iber, and M. S. Neuberger. 2001. B cells acquire antigen from target cells after synapse formation. Nature. 411:489–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrasco, Y. R., S. J. Fleire, T. Cameron, M. L. Dustin, and F. D. Batista. 2004. LFA- 1/ICAM-1 interaction lowers the threshold of B cell activation by facilitating B cell adhesion and synapse formation. Immunity. 20:589–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrasco, Y., and F. D. Batista. 2006. B-cell activation by membrane-bound antigens is facilitated by the interaction of VLA-4 with VCAM-1. EMBO J. 25:889–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleire, S. J., J. P. Goldman, Y. R. Carrasco, M. Weber, D. Bray, and F. D. Batista. 2006. B cell ligand discrimination through a spreading and contracting response. Science. 312:738–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis, M. M., and M. L. Dustin. 2004. What is the importance of the immunological synapse? Trends Immunol. 25:323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrasco, Y. R., and F. D. Batista. 2006. B cell recognition of membrane-bound antigen: an exquisite way of sensing ligands. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18:286–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi, S. Y., J. T. Groves, and A. K. Chakraborty. 2001. Synaptic pattern formation during cellular recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:6548–6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burroughs, N. J., and C. Wülfing. 2002. Differential segregation in a cell-cell contact interface: the dynamics of the immunological synapse. Biophys. J. 83:1784–1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee, K. H., A. R. Dinner, C. Tu, G. Campi, S. Raychaudhuri, R. Varma, T. N. Sims, W. R. Burack, H. Wu, J. Wang, O. Kanagawa, M. Markiewicz, P. M. Allen, M. L. Dustin, A. K. Chakraborty, and A. S. Shaw. 2003. The immunological synapse balances T cell receptor signaling and degradation. Science. 302:1218–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, S. J. E., Y. Hori, J. T. Groves, M. L. Dustin, and A. K. Chakraborty. 2002. Correlation of a dynamic model for immunological synapse formation with effector functions: two pathways to synapse formation. Trends Immunol. 23:492–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hori, Y., S. Raychaudhuri, and A. K. Chakraborty. 2002. Analysis of pattern formation and phase separation in the immunological synapse. J. Chem. Phys. 117:9491–9501. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raychaudhuri, S., A.K. Chakraborty, and M. Kardar. 2003. Effective membrane model of the immunological synapse. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91:208101–208104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coombs, D., M. Dembo, C. Wofsy, and B. Goldstein. 2004. Equilibrium thermodynamics of cell-cell adhesion mediated by multiple ligand-receptor pairs. Biophys. J. 86:1408–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weikl, T. R., and R. Lipowsky. 2004. Pattern formation during T-cell adhesion. Biophys. J. 87:3665–3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iber, D. 2005. Formation of the B-cell synapse: retention or recruitment? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62:206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsourkas, P., N. Baumgarth, S. I. Simon, and S. Raychaudhuri. 2007. Mechanisms of B cell synapse formation predicted by Monte Carlo simulation. Biophys. J. 92:4196–4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chakraborty, A. K., M. L. Dustin, and A. S. Shaw. 2003. In silico models for cellular and molecular immunology: successes, promises, and challenges. Nat. Immunol. 4:933–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein, B., J. R. Faeder, and W. S. Hlavacek. 2004. Mathematical and computational models of immune-receptor signaling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:445–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wülfing, C., and M. M. Davis. 1998. A receptor/cytoskeletal movement triggered by co-stimulation during T cell activation. Science. 282:2266–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wülfing, C., I. Tskvitaria-Fuller, N. Burroughs, M. D. Sjaastad, J. Klem, and J. D. Schatzle. 2002. Interface accumulation of receptor/ligand couples in lymphocyte activation: methods, mechanisms, and significance. Immunol. Rev. 189:64–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tolar, P., H. W. Sohn, and S. K. Pierce. 2008. Viewing the antigen-induced initiation of B cell activation in living cells. Immunol. Rev. 221:64–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hammer, D., and S. Apte. 1991. Simulation of cell rolling and adhesion of surfaces in shear flow: general results and analysis of selectin-mediated neutrophil adhesion. Biophys. J. 63:35–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahama, P. A., and J. J. Linderman. 1995. Monte Carlo simulations of membrane signal transduction events: effect of receptor blockers on G-protein activation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 23:299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Kampen, N. G. 2001. Stochastic Processes in Physics and Chemistry. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- 30.Krobath, H., G. J. Schutz, R. Lipowsky, and T. R. Weikl. 2007. Lateral diffusion of receptor- ligand bonds in membrane adhesion zones: effect of thermal membrane roughness. EPL. 78:38003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahya, N., D. A. Wiersma, B. Poolman, and D. Hoekstra. 2002. Spatial reorganization of bacteriorhodopsin in model membranes: light induced changes. J. Biol. Chem. 277:39304–39311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee, C. C., and O. N. Petersen. 2003. The lateral diffusion of selectively aggregated peptides in giant unilamellar vesicles. Biophys. J. 84:1756–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gambin, Y., R. Lopez-Esparza, M. Reffay, E. Sierecki, N. S. Gov, M. Genest, R. S. Hodges, and W. Urbach. 2005. Lateral mobility of proteins in liquid membranes revisited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:2098–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Access Excellence at the National Health Museum. http://www.accessexcellence.org/RC/VL/GG/ecb/antibody_molecule.php. Accessed June 16, 2008.

- 35.Alberts, B., A. Johnson, J. Lewis, M. Raff, K. Roberts, and P. Walter. 2002. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th ed. Garland Science, London. p. 1375.

- 36.Dembo, M., T. C. Torney, K. Saxman, and D. Hammer. 1988. The reaction-limited kinetics of membrane-to-surface adhesion and detachment. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 234:55–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell, G. I. 1983. Cell-cell adhesion in the immune system. Immunol. Today. 4:237–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tominaga, Y., Y. Kita, A. Satoh, S. Asai, K. Kato, K. Ishikawa, T. Horiuchi, and T. Takashi. 1998. Expression of a soluble form of LFA-1 and demonstration of its binding activity with ICAM-1. J. Immunol. Methods. 212:61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Favier, B., N. J. Burroughs, L. Weddeburn, and S. Valitutti. 2001. T cell antigen receptor dynamics on the surface of living cells. Int. Immunol. 13:1525–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouchaud, J.-P., and A. Georges. 1990. Anomalous diffusion in disordered media: statistical mechanisms, models and physical applications. Phys. Rep. 195:127–293. [Google Scholar]