Abstract

Intracellular effects of submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses imply changes in a cell's plasma membrane (PM) and organelle membranes. The maximum reported PM transmembrane voltage is only 1.6 V and phosphatidylserine is translocated to the outer membrane leaflet of the PM. Passive membrane models involve only displacement currents and predict excessive PM voltages (∼25 V). Here we use a cell system model with nonconcentric circular PM and organelle membranes to demonstrate fundamental differences between active (nonlinear) and passive (linear) models. We assign active or passive interactions to local membrane regions. The resulting cell system model involves a large number of interconnected local models that individually represent the 1), passive conductive and dielectric properties of aqueous electrolytes and membranes; 2), resting potential source; and 3), asymptotic membrane electroporation model. Systems with passive interactions cannot account for key experimental observations. Our active models exhibit supra-electroporation of the PM and organelle membranes, some key features of the transmembrane voltage, high densities of small pores in the PM and organelle membranes, and a global postpulse perturbation in which cell membranes are depolarized on the timescale of pore lifetimes.

INTRODUCTION

We present an argument for needing nonlinear interaction mechanisms to explain basic features of the response of living cells to submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter electric fields, a growing research activity (1). The central interaction is electroporation, the formation of transient aqueous pores in phospholipid-based artificial and biological membranes in response to elevated transmembrane voltages due to the application of large pulsed electric fields (2,3). Electroporation can enhance or enable molecular delivery to cells by permeabilizing the plasma membrane (PM) and has been widely used as a tool for delivering DNA and other molecules into cells. Yet despite its widespread usage in biological research and numerous studies aimed at characterizing the membrane response to applied electric fields, much remains unknown about the basic mechanisms of electroporation (4,5).

Recently, there has been a renewed interest in electroporation because of reports that submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses can electroporate the membranes of the cell interior, opening the possibility for new biotechnological and therapeutic applications of electroporation (6–29). Experimentally observed cellular responses to such short duration, large magnitude pulses include cytochrome c release, caspase activation, apoptosis induction, phosphatidylserine (PS) translocation, changes in intracellular calcium concentration, and little or delayed uptake of membrane integrity dyes such as propidium iodide (PI). Apoptosis induction is of particular interest because of its potential uses for clinical applications.

Electroporation is difficult to study experimentally because the phenomenon occurs on short time and length scales. Except for reports of large, secondary pores after a large applied electrical pulse (30), electroporation experiments have not directly observed pores in cell membranes. Instead, most experiments have examined secondary effects of electroporation, such as the transmembrane transport of DNA and fluorescent dyes, and changes in transmembrane voltage. Because of the challenges in probing the basic mechanisms of electroporation experimentally, theoretical models have played an important role in elucidating the basic mechanisms that lead to the secondary effects observed experimentally. The recent push to study ever shorter, larger pulses that significantly perturb the cell interior provides further motivation for theoretical approaches. Unfortunately, some of these theoretical approaches have been overly simplistic and applied beyond a scope that is justified given their assumptions. Examples include the use of charging time constants and equations that are inadequate on the nanosecond timescale (6,7,11,12,15,18,19,23,25) and the use of electrical models that do not explicitly represent pore formation and resulting pore conduction (6,7,11,12,15,18,19,23,25,31,32), thereby predicting transmembrane voltages far in excess of what experiments and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations show biological membranes can sustain.

Models of the electrical response of cells to applied electric fields can broadly be classified as passive (linear) or active (nonlinear). In passive models, the electrical properties are fixed and the system is linear and time-invariant, whereas in active models, the electrical properties are not fixed and the system can be both nonlinear and hysteretic. More specifically, active models account for the tremendous increase in membrane conductance that accompanies electroporation, while passive models assume that the membrane conductance remains unaltered. The predictions of active and passive models should be identical in the limit of applied electrical pulses too small to cause electroporation. However, the predictions diverge dramatically for the large applied electrical pulses in submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter experiments. Here we demonstrate the striking differences between the predictions of passive and active models and question the continued use of simplistic passive models in interpreting submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter experiments. Furthermore, as in recent experimental articles (23,26,27), we challenge the suggestion that submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses can significantly electroporate intracellular membranes without electroporating the PM. Note that these two objectives are essentially equivalent because the suggestion that a passive model adequately represents the PM is equivalent to saying that the PM is not electroporated.

We employ two spatially distributed two-dimensional cell models constructed using the meshed transport network method (MTNM), a robust method for simulating nonlinear and coupled transport phenomena (1,33) that is a more general formulation of the transport lattice method (TLM) (34,35). The first model is a passive model similar to traditional spherical cell models with a concentric organelle (31,32), and insofar as it is passive, a much simpler model (15). The second model is an active model with local membrane models based on the asymptotic model of electroporation (35,36). To be specific, we compare the electrical responses of active and passive spatially distributed cell models to a nominally 60 ns, 95 kV/cm pulse similar to the pulse used in a recent experimental study (37).

METHODS

Model system

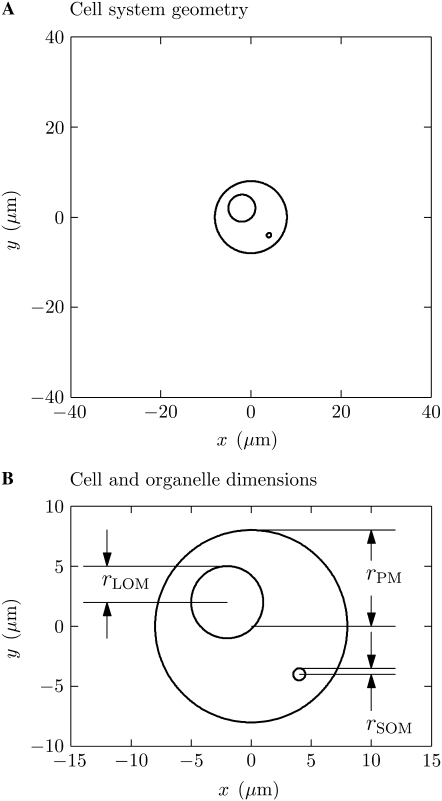

The cell system comprises a circular plasma membrane (PM) enclosing one circular large organelle membrane (LOM) (nucleus-sized) and one circular small organelle membrane (SOM) (mitochondrion-sized), a large region of extracellular electrolyte, and a pair of ideal planar electrodes (Fig. 1 A). The membranes have thickness dm = 5 nm and radii rPM = 8 μm, rLOM = 3 μm, and rSOM = 0.5 μm. To emphasize the ability of the model to use asymmetric cell geometry, the LOM and SOM centers are purposefully offset from the PM center by (−2 μm, 2 μm) and (4 μm, −4 μm), respectively (Fig. 1 B). The membranes have resting potentials Vrest, PM = −50 mV, Vrest, LOM = 0 mV, and Vrest, SOM = −200 mV, which are typical of a Jurkat cell PM, nucleus, and mitochondrion, respectively. Consistent with experimental observations and most traditional models (32,38), the cytosol conductivity, σi, was chosen initially to be a quarter of the extracellular conductivity, σe, because of the large intracellular volume fraction that is excluded from ionic transport in the crowded interior of a cell. Later we treat the case σi = σe. The electric field, Eapp, is applied by ideal (zero overvoltage) planar electrodes at y = 40 μm (anode) and y = −40 μm (cathode) (Fig. 1 A). Here Eapp is the voltage applied between the electrodes, Vapp, divided by the distance between the electrodes, 80 μm. The bounding box for the system is 80 μm × 80 μm, with the cell centered. The bounding box was made much larger than the cell so that boundary effects would be negligible. The electrical parameters (Table 1) of the cell system are a combination of those used by others (32,37).

FIGURE 1.

Cell system model geometry. (A) The isolated cell is centered in a large (80 μm × 80 μm) region. The upper (anode) and lower (cathode) boundaries are planar electrodes. (B) The radii of the plasma membrane (PM), large organelle membrane (LOM), and small organelle membrane (SOM) are rPM = 8 μm, rLOM = 3 μm, and rSOM = 0.5 μm. These idealized, single-layer membranes represent the plasma membrane, nuclear envelope, and mitochondrial membrane. The poles, or polar regions, discussed in the text refer to the regions of greatest |y| for each membrane. The polar regions of membrane are perpendicular to the applied electric field.

TABLE 1.

System electrical and electroporation parameters

| Symbol | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| rPM | 8 μm | Plasma membrane radius. |

| rLOM | 3 μm | Large organelle membrane radius (typical nucleus). |

| rSOM | 0.5 μm | Small organelle membrane radius (typical mitochondrion). |

| σe | 1.2 S m−1 | Extracellular electrolyte conductivity. |

| σi | 0.3 S m−1 | Intracellular electrolyte conductivity. |

| σm | 9.5 × 10−9 S m−1 | Membrane conductivity. |

| εel = εe = εi | 72ε0 = 6.38 × 10−10 F m−1 | Electrolyte permittivity. |

| εm | 5 ε0 = 4.43 × 10−11 F m−1 | Membrane permittivity. |

| Vrest, PM | −50 mV | Cell resting potential. |

| Vrest, LOM | 0 mV | Large organelle resting potential. |

| Vrest, SOM | −200 mV | Small organelle resting potential. |

| α | 1 × 109 m−2 s−1 | Pore creation rate density. |

| Vep | 0.224 V | Characteristic electroporation voltage. |

| q | 1 | Electroporation coefficient. |

| No | 3.3 × 106 m−2 | Equilibrium pore density at Vm = 0 V. |

| rp | 0.8 nm | Minimum energy pore radius at Vm = 0 V. |

| dm | 5 nm | Membrane thickness. |

| wo | 3.2 kT | Pore energy barrier. |

| η | 0.15 | Pore relative entrance length. |

| T | 300 K | Temperature. |

| H | 0.50 | Steric hindrance. |

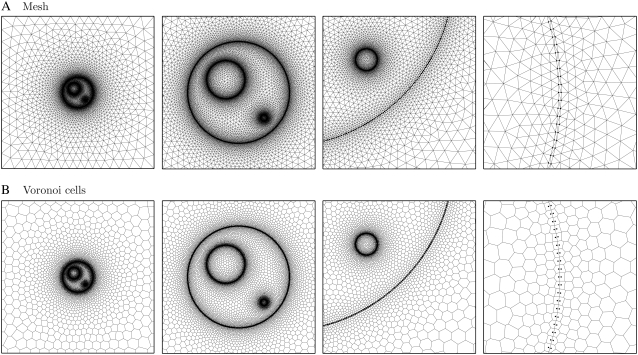

Mesh generation

A triangular mesh (Fig. 2 A) was generated for the cell system using a modified version of an open-source algorithm (39). The algorithm produces high-quality meshes with elements that may vary widely in size (1), here by three orders of magnitude. The PM, LOM, and SOM have 600, 400, and 200 transmembrane node pairs, respectively, and the entire mesh has 19,061 nodes, 38,061 triangles, and 57,121 edges.

FIGURE 2.

Cell system mesh and Voronoi cells. The cell system (A) mesh and (B) Voronoi cells are shown at four scales with black dots indicating membrane-surface nodes. The mesh has 19,061 nodes, 38,061 triangles, and 44,691 edges. For a sense of scale, the lengths of the subfigure sides are (left to right) 80, 24, 7, and 0.3 μm.

A Voronoi cell (VC) is associated with each node in the triangular mesh (Fig. 2 B). By definition, each VC encloses the region of the domain closer to its node than to any other node (40). As such, the sides of the VCs are perpendicular bisectors of the triangle edges, which simplifies the calculation of transport between adjacent nodes. The VCs are the small volumes into which the entire domain is discretized, with the behavior of each small volume being approximated by its associated node.

Meshed transport network method

The MTNM provides a robust framework for modeling complicated, spatially distributed, coupled transport phenomena. The method focuses on defining transport locally in terms of constitutive equations that can then be easily translated into equivalent circuits. The conservation principles imposed by Kirchhoff's Current Law join the locally specified constitutive equations into complete, spatially distributed models. Here Berkeley SPICE 3f5 is used to obtain the electrical response of cell equivalent circuit networks to pulsed electric fields.

The MTNM is a generalization of the TLM (34) to the use of unstructured meshes. While the results of comparative solutions of passive (41) and active (33) systems have shown that the two methods produce similar results, the MTNM is more accurate and computationally efficient because it uses unstructured meshes that respect the boundaries of all structures in the system and uses variably-sized elements that allow nodes to be optimally distributed throughout the system. For example, in the cell system mesh (Fig. 2 A), the triangular elements resolve the 5-nm thickness of membranes but expand in size to have a triangle edge length of ∼5 μm at the system boundary, a difference of three orders of magnitude. The use of 5 nm rectangular elements in the TLM would require a prohibitively large number of elements.

Representing transport in physical systems using equivalent circuits is a powerful conceptual tool in thinking about how quantities, such as charge, heat, and molecules, move from place to place. This is not, however, the only reason to use this abstraction. Robust computer software exists for simulating circuit networks. Thus, the numerical difficulties ordinarily encountered in simulating nonlinear transport are handled by the circuit simulation software, which has powerful numerical routines for simulating nonlinear devices, thereby decoupling the problem of solving the system of nonlinear transport equations from the problem of understanding the transport mechanisms and setting up a model that adequately characterizes the transport processes. Here the equivalent circuit networks describing the response of a cell are simulated using SPICE, though alternative simulation methods could also be used.

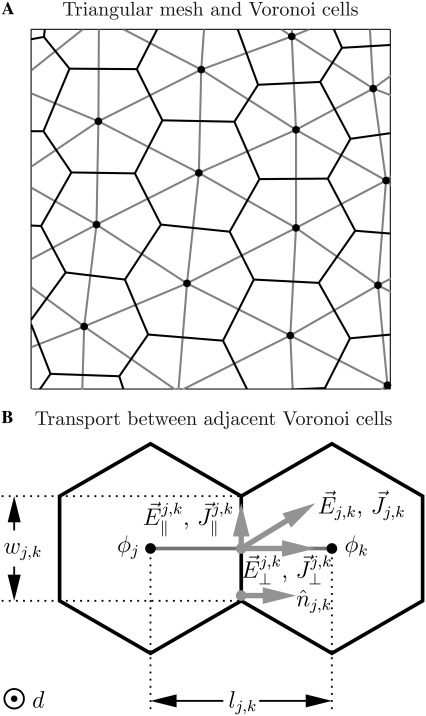

Fig. 3 shows the relationship between the mesh and VCs (Fig. 3 A) and the electrical transport between adjacent VCs j and k (Fig. 3 B). There exists an electric field  and current density

and current density  at the interface of VCs j and k. These vectors may be separated into components normal and parallel to the interface, and clearly only the former contribute to transport between the VCs. VCs j and k have potential difference (Δφ)j,k = φk – φj, a shared interface of area wj,kd, a nodal separation lj,k, and contain a medium with conductivity σ and permittivity ε. Thus, the total current flowing from VC j to VC k is

at the interface of VCs j and k. These vectors may be separated into components normal and parallel to the interface, and clearly only the former contribute to transport between the VCs. VCs j and k have potential difference (Δφ)j,k = φk – φj, a shared interface of area wj,kd, a nodal separation lj,k, and contain a medium with conductivity σ and permittivity ε. Thus, the total current flowing from VC j to VC k is

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

where Rj, k ≡ lj, k/(σwj, kd) and Cj, k ≡ εwj, kd/lj, k and  is used as the first-order approximation to the normal electric field at the interface. Therefore, the transport between VCs j and k may be represented by a parallel resistor-capacitor pair between nodes j and k in the circuit representation of the system.

is used as the first-order approximation to the normal electric field at the interface. Therefore, the transport between VCs j and k may be represented by a parallel resistor-capacitor pair between nodes j and k in the circuit representation of the system.

FIGURE 3.

Two-dimensional transport system. (A) Triangular mesh and Voronoi cells (VCs). The two-dimensional system is discretized into a set of VCs (solid) associated with the nodes connected by triangulation (shaded). (B) Adjacent Voronoi cells. The VCs have depth d and an interface of length wj,k, and the distance between the VC nodes is lj,k. The VCs have electric potentials φj and φk and, at the VC interface, there is an electric field  and current density

and current density  which can be broken into components normal (

which can be broken into components normal ( and

and  ) and parallel (

) and parallel ( and

and  ) to the interface.

) to the interface.

Conservation relations provide the additional basic constraint on the electrical transport by relating the currents flowing out of each VC. The total current flowing out of each VC must equal zero for timescales much greater than the charge relaxation time constant (ε/σ ≈ 0.5 ns for physiologic saline). This requirement is automatically imposed by Kirchhoff's Current Law in circuit space.

The complete circuit representation of a passive system is built by placing resistors and capacitors between all adjacent nodes with all values calculated according to local electrical parameters and mesh geometry, as described. To include active local mechanisms, sources and sinks can also be added with almost arbitrary dependencies. In this model, active subcircuits are used to calculate the local pore density and the associated transmembrane voltage and current.

The MTNM/TLM is not confined to modeling electrical transport. Rather, it may also be used to model simple molecular transport phenomena, such as diffusion, as well as coupled, nonlinear transport phenomena, such as electrodiffusion (1). Heat transport by diffusion (heat conduction) and perfusion (34,42) and phenomena comprising sources and sinks (e.g., chemical partitioning and thermal release of intracellular chemicals) ((43), A. T. Esser, K. C. Smith, T. R. Gowrishankar, Z. Vasilkoski, and J. C. Weaver, unpublished) can also be described. More details of the method may be found in the Appendix and Smith (1).

Electroporation model

Neu-Krassowska asymptotic model of electroporation

The dynamics of electroporation often are described by using the Smoluchowski equation with pore creation and destruction rates (2,45). In the limit of the pore creation/destruction dominating pore expansion/contraction, the Smoluchowski equation simplifies to the ordinary differential equation

|

(5) |

where N is the local pore density, α is the pore creation rate coefficient, Vm is the transmembrane voltage, Vep is the characteristic electroporation voltage, No is the equilibrium pore density for Vm = 0 V, and q is an electroporation coefficient (36).

The primary simplification of the asymptotic electroporation model is that pores are assumed not to expand. This assumption is reasonable for strong electric fields of short duration (46) but less so for intermediate to small electric fields of long duration. In response to elevated transmembrane voltage, pore creation and subsequent pore expansion contribute to increased membrane conductance and associated maintenance of a transmembrane voltage of ∼1 V or less (47–50). Pore creation proceeds much more rapidly (insofar as it increases membrane conductance) than pore expansion. As such, pore creation dominates pore expansion when the applied electric field is very large while pore expansion is at least commensurate with pore creation when the applied electric field is smaller (51). Although the detailed pore population behavior is a function of the applied field, the electrical predictions of the model are quite robust. That is, whether pore creation or expansion dominates, the processes proceed toward a state in which the transmembrane voltage drops from a transient peak somewhat >1 V down to ∼1 V as a consequence of reversible electrical breakdown (REB) of the membrane. For longer pulses, a model with pore expansion predicts that the transmembrane voltage drops to a somewhat smaller ∼0.5 V (A. T. Esser, K. C. Smith, T. R. Gowrishankar, Z. Vasilkoski, and J. C. Weaver, unpublished, (50)). Pore expansion (A. T. Esser, K. C. Smith, T. R. Gowrishankar, Z. Vasilkoski, and J. C. Weaver, unpublished, (50)) will become more important in future models that describe molecular uptake, which is expected to depend strongly on the pore size distribution.

Pore conductance

A cylindrical pore with electrolyte conductivity σe, radius rp, thickness dm, and steric hindrance H(rp) has conductance

|

(6) |

where K is the transmembrane voltage-dependent partition coefficient

|

(7) |

The value wo is the energy barrier inside a pore, η is the relative entrance length of a pore, and νm is the dimensionless transmembrane voltage νm ≡ Vmqe/kT (46,52). Here qe is the charge of the monovalent ions (Na+, K+, Cl−) that dominate the electrical conductivity of typical electrolytes. Thus, the current im, p through pores in a small region of membrane with area Am and pore density N is

|

(8) |

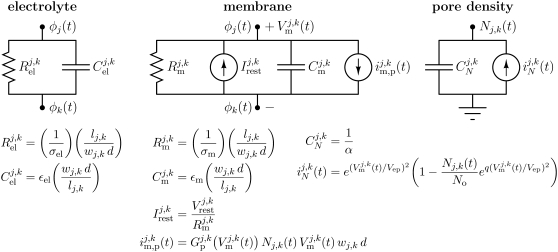

Cell model equivalent circuit

Fig. 4 shows the circuit representations and their expressions for each pair of adjacent nodes j and k in the system model equivalent circuit. Most of the nodes lie within electrolyte, and the transport between these nodes is simply described by the electrolyte resistance,  and capacitance,

and capacitance,  associated with the transport between the Voronoi cells corresponding to the circuit nodes. The values

associated with the transport between the Voronoi cells corresponding to the circuit nodes. The values  and

and  are calculated as described above in Meshed Transport Network Method, and are determined by the electrolyte conductivity, σel, and permittivity, εel, and the distance, lj,k, between nodes j and k and the width, wj,k, and depth, d, of their shared VC interface.

are calculated as described above in Meshed Transport Network Method, and are determined by the electrolyte conductivity, σel, and permittivity, εel, and the distance, lj,k, between nodes j and k and the width, wj,k, and depth, d, of their shared VC interface.

FIGURE 4.

Local model equivalent subcircuits for cell system model (Figs. 1 and 2). An electrolyte or membrane subcircuit is placed between each pair of adjacent nodes in the cell system. The electrical transport is determined by the local mesh geometry, passive electrical properties of the electrolyte and membranes, and, at the membranes, by the instantaneous pore density and associated time-dependent conductance, which provide a rapidly changing (active) response mechanism. In the active model, each membrane subcircuit has an associated pore density (units: m−2) subcircuit (35) that is used to calculate the total current through pores. In the passive model, there are no pores, and the membrane conductance is constant.

In the active cell model, the equivalent membrane subcircuit is much more complex than the electrolyte subcircuit describing transport in the electrolyte because of the highly nonlinear change in electroporated membrane conductance (Fig. 4). The provision of the resting potential sources is a further complication. The passive membrane resistance,  and capacitance,

and capacitance,  have conductivity σm, and permittivity εm, and the same length parameters as the electrolyte, lj,k, wj,k, and d. In this case, lj,k = dm. The current through pores,

have conductivity σm, and permittivity εm, and the same length parameters as the electrolyte, lj,k, wj,k, and d. In this case, lj,k = dm. The current through pores,  is determined by the conductance per pore,

is determined by the conductance per pore,  pore density, Nj,k(t), instantaneous transmembrane voltage,

pore density, Nj,k(t), instantaneous transmembrane voltage,  and local membrane area,

and local membrane area,  is simply calculated by Eq. 6, but Nj,k(t) must be calculated by solving Eq. 5.

is simply calculated by Eq. 6, but Nj,k(t) must be calculated by solving Eq. 5.

This is accomplished by a subcircuit that describes the creation and storage of pores, i.e., a pore creation rate that is mathematically analogous to a current and pore accumulation (storage) that is mathematically analogous to charging a capacitor. Specifically, this integration is performed by a small subcircuit with a capacitor,  and a current source,

and a current source,  that is a function of Nj,k(t) and

that is a function of Nj,k(t) and  (Fig. 4) (35). The constitutive relation for the capacitor relates its voltage, Nj,k(t) (units: pore m−2), to its pore current,

(Fig. 4) (35). The constitutive relation for the capacitor relates its voltage, Nj,k(t) (units: pore m−2), to its pore current,  (units: dimensionless), by

(units: dimensionless), by

|

(9) |

where the expressions for  and

and  are as shown in Fig. 4. This is the differential equation governing pore creation in Eq. 5. Therefore, the subcircuit solves Eq. 5:

are as shown in Fig. 4. This is the differential equation governing pore creation in Eq. 5. Therefore, the subcircuit solves Eq. 5:

|

(10) |

The initial condition at time t0 is satisfied by assigning the initial (equilibrium) pore density, Nj,k(t0), to  at the start of the simulation,

at the start of the simulation,

|

(11) |

where Vrestj,k is the resting potential of the membrane between nodes j and k.

The membrane resting potential between nodes j and k is provided by the constant current source  (Fig. 4). The resting potential is normally represented by a constant voltage source in series with the membrane resistance (53). However, the Norton equivalent circuit is used here, in which the current source

(Fig. 4). The resting potential is normally represented by a constant voltage source in series with the membrane resistance (53). However, the Norton equivalent circuit is used here, in which the current source  (the contribution of pores to the total membrane conductance is negligible at

(the contribution of pores to the total membrane conductance is negligible at  ) was placed in parallel with the total membrane resistance. This gave faster computation times.

) was placed in parallel with the total membrane resistance. This gave faster computation times.

Circuit generation and simulation

MATLAB 7.3 and Berkeley SPICE 3f5 were the primary software packages used to generate and run the cell system model. MATLAB generated the meshes and determined all of the circuit element values based on the electrical and electroporation parameters and the mesh geometry. MATLAB output large circuit netlists, which are text files that list each circuit element and its parameters and connections (54). The netlists were then loaded by SPICE and the corresponding circuits were solved. SPICE then created a binary output file containing all of the circuit node voltages and currents through dependent sources. These SPICE output files were loaded by MATLAB and all of the important variables were extracted, analyzed, and plotted in traditional formats, e.g., equipotentials. The model solutions and analysis were performed on a computer with dual 2.4 GHz Intel Xeon processors and 4 GB RAM running Red Hat Linux.

RESULTS

To be specific and relevant to reported observations, we examined the responses of both a passive and an active cell model to an idealized version of the pulse used experimentally by Frey et al. (37). Their pulse was nominally 60 ns duration and 95 kV/cm magnitude. Here, 60 ns is the approximate duration of the pulse plateau (peak value). We fit the pulse waveform measured at the electrodes of the experimental apparatus (37), which gave a 71 ns, 95 kV/cm trapezoidal pulse with a 6 ns rise-time, 55 ns plateau, and 10 ns fall-time (Fig. 5). The models' results are presented in several different ways to give a comprehensive sense of the differences between the active and passive model responses.

FIGURE 5.

Electric field pulse. The pulse applied to the cell system model was an idealized trapezoidal version of the pulse used experimentally by Frey et al. (37) (95 kV/cm; 6 ns rise-time, 55 ns plateau, and 10 ns fall-time). Solid dots indicate the times at which the results are plotted in Figs. 6 and 7.

Spatial comparison of electric potentials

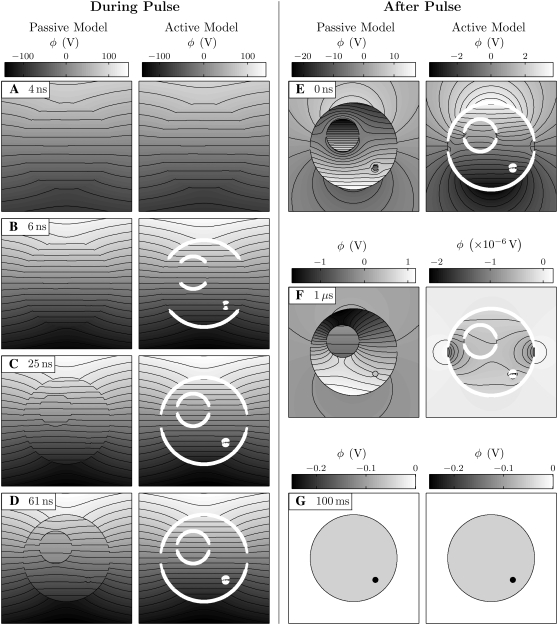

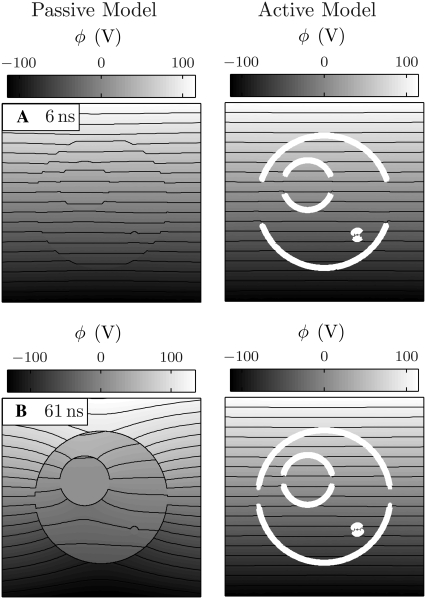

Fig. 6 shows the responses of the passive and active cell models to an idealized version of the pulse (Fig. 5) used experimentally by Frey et al. (37), and provides a general idea of the differences between the models. The electric potential is shown by the equipotential contour lines and grayscale, and, for the active model, thick open lines indicate membrane areas with significant electroporation (>1014 m−2; mean pore spacing <100 nm).

FIGURE 6.

Passive and active cell responses. The electric potential and pore density are shown for the cell models (A–D) during and (E–G) after the electric pulse. For the active model, pore density is indicated by the white line thickness (1014, 1015, 1016 m−2). Twenty-one contour lines are uniformly spaced between the extreme values of their associated grayscale bars. Note that the intracellular and extracellular electric field magnitude are not equal, even early in the pulse, because σi = σe/4 (Table 1). See Fig. 10 for the case σi = σe.

The responses of the passive and active models are similar during the early phase of the pulse, before pores form in the membranes of the active model (Fig. 6 A). The membrane impedance is initially largely determined by the membrane dielectric properties because of the extremely low conductivity of the membrane and high frequency content of the pulse rise. The equipotential lines are more closely spaced (i.e., the electric field magnitude is larger) inside the cell than outside because of the smaller conductivity of the cytosol (Table 1).

Shortly before the end of the 6 ns pulse rise-time, the polar regions of the PM, LOM, and SOM reach transmembrane voltages of 1–1.4 V and rapidly form pores in the active model (Fig. 6 B) at a rate determined by Eq. 5. The tremendous increase in membrane conductance that accompanies pore formation causes a sudden shift at ∼4 ns, from dielectric to conductive property-determined membrane impedance. The pore creation is self-limiting in that pore creation decreases the transmembrane voltage to a level (∼1 V) at which the pore creation rate is much slower.

The passive model has no mechanism by which the membrane conductance can be altered. For that basic reason, the PM, LOM, and SOM continue to charge well beyond the 1.4 V maximum transmembrane voltage of the active model, reaching 27 V, 23 V, and 11 V for the 71 ns, 95 kV/cm pulse. The membrane impedance in the passive model continues to primarily be determined by membrane dielectric properties.

As the pulse continues, in the active model the regions farther from the poles charge to 1–1.4 V and electroporate (Fig. 6, B–D). All membrane areas achieve significant pore densities except narrow equatorial bands around the PM, LOM, and SOM that do not charge beyond ∼1 V on the timescale of the applied pulse. The high conductance state of the membrane results in continued penetration of the electric field into the intracellular and intraorganellar spaces (Fig. 6 D), even as the highest frequency components decay.

In contrast, in the passive model, the electric field is increasingly excluded from the intracellular and intraorganellar spaces as the highest frequency components decay, and the fixed conductance of the membrane remains too small to permit such a significant electric field penetration (Fig. 6 D).

The cell and organelle membranes discharge rapidly after the end of the pulse (Fig. 6, E–G). In the active model, the membranes discharge to ∼0 V in ∼50 ns because the greatly increased membrane conductances temporarily prevent the reestablishment of the cell and organelle resting potentials. As the pore densities exponentially decay with a time constant of No/α = 3.3 ms (46), the conductances of the membranes return to their original values and the cell resting potentials are reestablished, based on the simplifying assumption that the resting potential source is unaltered. Here, the resting potential recovery takes 70 ms (∼20 times the 3.3 ms time-constant for pore destruction).

Remarkably, the transmembrane voltages do not approach ∼0 V in the passive model. Rather, they directly approach the membrane resting potentials at a rate slower than the rate of membrane discharge in the active model. Specifically, the resting potentials are reached after ∼3.5 μs in the passive model.

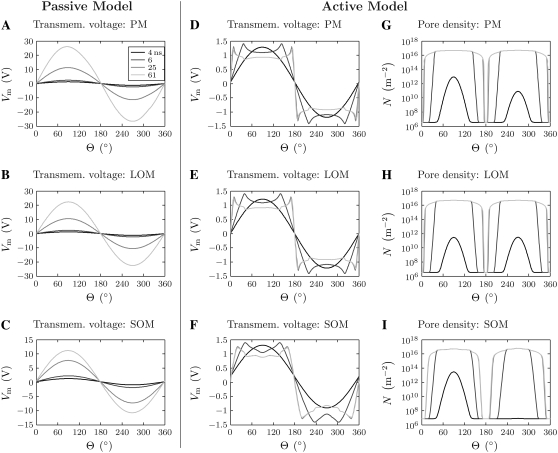

Transmembrane voltage and pore density distribution

Fig. 7 shows the transmembrane voltage as a function of angle, Vm(Θ), at four times (4, 6, 25, 61 ns) for the passive and active cell models. For the passive model, the Vm(Θ) values have nearly cosine profiles that grow in amplitude throughout the pulse (Fig. 7, A–C). The profiles are vertically shifted by the membrane resting potentials and deviate from perfect cosine curves at angular values where the membranes are close to each other, particularly toward the end of the pulse when the electric field inside the cell becomes less uniform (Fig. 6 D). The PM, LOM, and SOM reach peak anodic and cathodic transmembrane voltages of 26.8 V and 27.4 V, 22.7 V and 22.8 V, and 11.2 V and 10.7 V at the end of the pulse (61 ns), respectively.

FIGURE 7.

Angular distributions of responses. The (A–F) transmembrane voltage and (G–I) pore density are shown as a function of angle for the plasma membrane (PM) and each organelle membrane (LOM, SOM) for the passive and active cell models. Times shown (from dark to light gray) are 4, 6, 25, and 61 ns. Θ = 90° is the anodic pole and

Θ = 270° is the cathodic pole. Note that there are few changes in Vm and N between 25 ns and 61 ns and, consequently, the 61 ns traces obscure the 25 ns traces in many of the plots.

For the active model, the Vm(Θ) values initially (while Vm is still small) exhibit cosine profiles identical to those of the passive model (Fig. 7, A–F). The amplitudes of the Vm(Θ) curves increase until they exceed ∼1–1.4 V at ∼3 ns, and REB occurs (Fig. 7, G–I). Pores form first at the hyperpolarized anodic poles of the PM and SOM and slightly later at the depolarized cathodic poles (Fig. 7, G and I). Pores form simultaneously at both the anodic and cathodic poles of the LOM, which does not have a resting potential (Fig. 7 H). As pores form, the conductances of the membranes increase, and Vm is driven down because of voltage division with the fixed conductance of the aqueous media. This dynamic behavior results in waves of elevated Vm and pore creation traveling from the membrane poles toward the membrane equators as the pulse progresses, leaving in their wakes Vm ≈ 1 V and N ≈ 5 × 1016 m−2 (mean pore spacing ∼5 nm) (Fig. 7, D–I).

The Vm values of the polar regions of the membranes peak during the 6 ns pulse rise-time, which then leads to somewhat higher N and lesser resultant Vm. The pulse rise has the highest frequency components of the pulse. Therefore, in comparison to the lower frequency content of the pulse plateau, during the rise more pores must be created for the membrane conductive properties to dominate the dielectric properties and drive Vm down to a level at which pore creation is lessened. Additionally, the post-peak decrease in Vm is slightly slowed by the continued increase of Vapp during the rise-time (Fig. 8 B). Therefore, Vm and N reach higher values than they tend to during a pulse plateau. This rise-time effect, as it will be called hereafter, is manifest in Fig. 7, D–I, by the relatively sharp transitions in Vm(Θ) and N(Θ) profiles at the interfaces between regions of membrane that do and do not electroporate during the rise-time. This is apparent in the Vm(Θ) profiles by looking at the maxima and minima of Vm(Θ) at the end of the 6 ns rise-time and noting that they align exactly with the sharp transitions in Vm(Θ) that are apparent at the next time point (25 ns).

FIGURE 8.

Temporal responses. (A and B) Transmembrane voltage and (C) pore density at the anodic (solid lines) and cathodic (dashed lines) poles of the plasma membrane (PM) and organelle membranes (LOM, SOM) for the (A) passive and (B and C) active cell models. Each plot is shown for 10 ns (top with dotted-line indicating end of pulse rise-time) and 100 ns (bottom) timescales. Note the significant differences in the voltage scales for passive and active models. The initial, pre-electroporation Vm are the same for both models, but the post-electroporation Vm differ greatly. For the passive model, the Vm increase throughout the pulse and peak at the end of the applied pulse plateau (61 ns). For the active model, the maximum Vm occur at ∼4 ns because the accompanying burst in pore creation and REB cause a large increase the membrane conductance and concomitant decrease in Vm.

The N(Θ) profiles are quite broad for all three membranes at the end of the pulse, with nearly all regions electroporating except the narrow bands near the membrane equators (Fig. 7, G–I).

After the pulse, Vm values quickly fall to ∼0 V for all of the membranes, with the Vm falling fastest in the highly electroporated polar regions (not shown), for which the largest conductance most quickly discharges the fixed capacitance of the membranes.

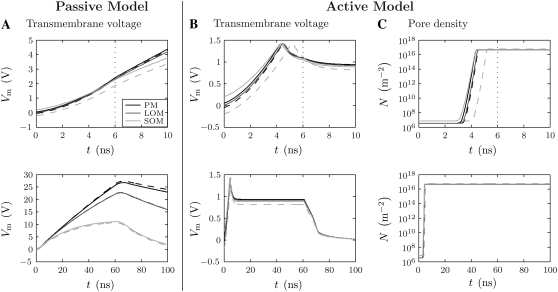

Transmembrane voltage and pore density at the membrane poles

Fig. 8 shows the temporal responses at the poles of the PM, LOM, and SOM for the passive and active models. Two timescales are shown to give a sense of the changes both over the duration of the entire pulse and during the early phase of the pulse.

In the passive model, the poles of the membranes initially charge at rates that are independent of their size (Fig. 8 A) (41). However, as the pulse proceeds into the plateau phase, the charging rates of the LOM and SOM decrease more substantially than that of the PM. By the end of the pulse plateau, the PM, LOM, and SOM anodic and cathodic poles reach 26.8 V and 27.4 V, 22.7 V and 22.8 V, and 11.2 V and 10.7 V, respectively (Fig. 8 A). The relative differences in Vm between the anodic and cathodic membrane poles are small. After the pulse, the Vm decay toward the membrane resting potentials (not shown), reaching resting values after ∼3.5 μs.

In the active model, the applied electric field is sufficiently large to drive all of the Vm of the cell and organelle membrane poles into REB and electroporate them during the 6 ns pulse rise-time (Fig. 8 B). As in the passive case, the initial charging rates are largely independent of the membrane radii because of the high frequency content of the pulse rise (Fig. 8 B). Additionally, the Vm are identical to the Vm of the passive model until ∼3 ns (4% of the pulse duration), when the poles electroporate (Fig. 8 C).

The polar Vm peaks first at the PM and SOM anodic poles at 4.3 ns, and then is closely followed by the PM cathodic pole and both LOM poles at 4.5 ns and the SOM cathodic pole at 5.2 ns. All poles reach a peak Vm of 1.4 V. Accordingly, all of the poles reach N of ∼5 × 1016 m−2 (mean pore spacing ∼5 nm). For each membrane pole, essentially all pore creation starts after ∼3 ns, lasts ∼1 ns, and coincides with the peak in Vm (REB) (Fig. 8, B and C). Because pore creation occurs at the beginning of the pulse and with such rapidity, the membrane poles have high pore density, and therefore high conductance, for nearly the entire duration of the applied pulse (Fig. 8 C). The dramatically increased conductance drives down the polar Vm (Fig. 8 B). Because of the rise-time effect, the increase in the membrane conductance that accompanies electroporation is sufficient to drive the Vm down to ∼0.9 V for the remainder of the pulse plateau.

During the pulse fall-time and after the pulse, the polar Vm of the membranes decrease and quickly reach 0 V (Fig. 8 B). This extensive depolarization lasts much longer than the pulse. The polar Vm drop quickly during the fall-time because the Vm are primarily determined by the conduction-dominated voltage division between the electrolyte and the membranes. Thus, the polar Vm(t) profiles mirror the Eapp(t) profile. The polar Vm quickly approach ∼0 V. The pore population then decays exponentially with a time constant of 3.3 ms (not shown), much longer than the ∼60 ns pulse.

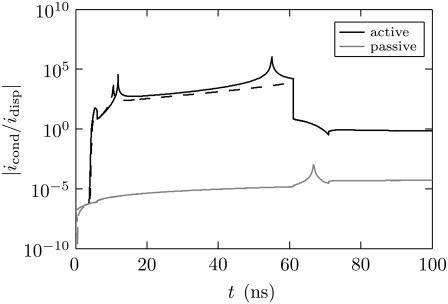

Dominance of conduction over displacement membrane current

The essential difference between the passive and active models is that pores form in the active model membranes in response to elevated transmembrane voltages, dramatically increasing the membrane conductance and depressing the transmembrane voltage. This tremendous change in local membrane conductance results in major differences in the electrical responses of the passive and active models. The total current through the membrane is the sum of conduction and displacement current contributions. For frequencies f < σm/2πεm, the conduction current dominates the displacement current. For frequencies f > σm/2πεm, the displacement current dominates the conduction current. Here σm is the membrane conductivity (or, in the presence of pores, the effective membrane conductivity) and εm is the membrane permittivity. For the passive membranes, σm/2πεm = 34 Hz. For the active membranes, σm/2πεm = 34 Hz in the absence of pores, as in passive membranes, but σm/2πεm = 86 MHz at a pore density of N = 5 × 1016 m−2.

Fig. 9 shows the ratio of the PM conduction current to the PM displacement current for the active and passive models. The total currents are obtained by integrating over the entire anodic and cathodic sides of the PM.

FIGURE 9.

Membrane current. The ratio of the conduction current to the displacement current for the anodic (solid) and cathodic (dashed) PM sides for the active (solid) and passive (shaded) models. After ∼4 ns, the conduction current is ∼3 orders-of-magnitude larger than the displacement current for the active model. In contrast, the conduction current remains ∼5 orders-of-magnitude smaller than the displacement current for the passive model.

The applied pulse has high frequency content because of its short duration, and the conductivity, σm, of the passive (fixed) membrane is very small (Table 1). Therefore, in the passive model, the membrane current is dominated by the displacement current for the entire duration of the pulse (Fig. 9). In the active model, however, the membrane current is briefly dominated by the displacement current (∼4 ns), but thereafter rapid creation of pores dramatically increases σm and then results in the dominance of the conduction current by several orders of magnitude (Fig. 9).

In addition to dominating the electrical conduction after ∼4 ns, the pores provide aqueous pathways for transport of small charged and neutral molecules (e.g., calcium), but not large molecules, and may thereby provide a mechanism for secondary effects.

DISCUSSION

Supra-electroporation

The term supra-electroporation was introduced to emphasize the hypothesis that an extraordinary number of small pores are created by 60 ns, 60 kV/cm pulses (35). At that time, and often continuing today, many experimental studies have instead hypothesized that ultrashort pulses perturb subcellular structures without perturbing the PM because the measured intracellular fluorescence of PI and ethidium homodimer (membrane-integrity dyes) is minimal after submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses but not after conventional pulses (6,8–12,14,17,19). Intracellular effects are often explained by arguments based on membrane charging time constants in which the charging time constants are claimed to be shorter for organelle membranes than the PM because of their smaller sizes. However, because of the importance of membrane dielectric properties on short timescales, this assumption is incorrect. On short timescales, the initial rate of membrane charging is independent of the size of the membrane-enclosed region (31,32,35,41). Moreover, aside from whatever parameter adjustments one may propose to make organelle membranes charge faster, the electrical properties of the PM are well established, and passive model simulations show that transmembrane voltages greatly exceeding values for REB (∼1 V) on these timescales would be produced in the absence of PM pores in response to the megavolt-per-meter pulses applied in experiments (32,33,35,41,55), which are generally on the order of 50–150 kV/cm. Furthermore, there is no mechanistic hypothesis for why similar transmembrane voltages would have dramatically different effects on the PM and the organelle membranes.

Significantly, experimentalists have used very different metrics for assessing perturbations of the PM and organelle membranes. The PM integrity has generally been assessed by the transmembrane transport of PI and ethidium homodimer, while the integrity of subcellular structures has usually been more indirectly assessed by detecting intracellular calcium concentration changes and other nonmembrane quantities and events (e.g., caspase activation) and then inferring that subcellular structures have been electroporated or otherwise perturbed. However, membrane integrity dyes are only a reasonable method of assessing PM electroporation if the pores created are large enough and numerous enough to transport sufficient dye molecules to exceed the optical measurement detection threshold of the particular experimental system. In response to submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses, however, pore creation dominates pore expansion and pores remain ∼0.8 nm in radius (46), thereby admitting but hindering transport of larger, highly charged dyes while leaving transport of smaller species, like calcium and monovalent ions, relatively unhindered. As such, assertions that the PM remains unperturbed while the intracellular organelles are significantly perturbed are unwarranted because of the differences in the methods of the detection of the perturbations.

An alternative hypothesis, supported by the results presented here and elsewhere (1,33,35,55,56), is that submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses lead to supra-electroporation, in which minimum-sized (∼0.8 nm) pores form in essentially all cell membranes. According to this hypothesis, the size and charge selectivity of the small pores limits uptake of membrane integrity dyes and limits loss of essential intracellular molecules, which is thought to also reduce the likelihood of necrotic cell death.

Recent experimental and MD studies are consistent with the supra-electroporation hypothesis. Experimental observations of PS externalization (18,19,21,23,29) are consistent with the supra-electroporation hypothesis. PS is a negatively-charged phospholipid normally located only on the intracellular leaflet of the PM. In a typical set of experiments, 30 ns pulses of up to 35 kV/cm magnitude were applied to cells in suspension. Asymmetric externalization of PS was observed, with significantly more PS externalization on the anodic side of the cell (19). Such asymmetric PS externalization is consistent with electrophoretic transport of negatively-charged PS through pores (21,29,57).

Vernier et al. (23) demonstrated that exposure of cells in vitro to repeated pulses can result in measurable uptake of the fluorescent dyes YO-PRO-1 and PI. They applied 4 ns and 30 ns pulses with repetition frequencies up to 10 kHz and magnitudes up to 80 kV/cm. YO-PRO-1 uptake was observed for 4 ns, 60 kV/cm pulses applied 30 or more times at 1 kHz, and PI uptake was observed for 4 ns, 80 kV/cm pulses applied 100 or more times at 10 kHz (25). These results suggest that submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses do electroporate the PM and contribute to transmembrane transport of fluorescent dyes, but that the number of dye molecules transported per pulse is small, as evidenced by the need to apply many pulses in quick succession to achieve detectible levels of intracellular dye (25). This is consistent with the supra-electroporation hypothesis, which predicts the presence of minimum-sized PM pores, limiting transmembrane transport of small molecules.

Very recent experiments reported changes in whole-cell PM conductance in response to 60 ns, 12 kV/cm pulses using patch-clamp measurements (26,27). They found significant increases in the PM conductance after the pulses. While the increased PM conductance lasted minutes, uptake of the membrane integrity dye PI was below the detection threshold in the 30–60 min after the pulse, suggesting that the pores that result in the increased PM conductance remain too small to permit significant uptake of PI (27). These findings are also consistent with the supra-electroporation hypothesis (1,33,35,55,56).

MD simulations provide still more support for the supra-electroporation hypothesis (21,29,57–61). These models simulate the movement and interaction of membrane and electrolyte molecules in the presence of an externally applied electric field (23,57–60) or an imbalance of sodium ions (29,61). These simulations generally apply or create relatively large transmembrane voltages of 2–3 V to increase the probability of pore formation within a few nanoseconds because of the tremendous computational resources required for the simulations. In the small spatial regions simulated, the membranes form defects that become small pores within nanoseconds. It is not yet clear if this forcing results in behavior that is consistent with experimental conditions. Nevertheless, the MD simulations have the potential to greatly enhance the as yet poorly understood dynamics of pore formation and transmembrane transport of small ions and molecules, and may provide better estimates of parameters used in continuum models, such as pore lifetime.

Recently, Frey et al. (37) studied the response of Jurkat cells in vitro to a 60 ns, 95 kV/cm (nominal) pulse using a fast, voltage-sensitive dye. The study used very technically difficult methods and represents the only study thus far, to our knowledge, on the transmembrane voltage of cells in suspension during a submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulse (37). The pulse used in this study (Fig. 5) is an idealized version of the pulse used in the experimental study of Frey et al., which found that the transmembrane voltage at the anode and cathode quickly rose to 1.6 V and 0.6 V, peaking at 15 ns, decreased to 1.2 V and 0.4 V at the end of the pulse plateau, and then both decreased to ∼0 V within 40 ns of the end of the pulse (37). The results of the active model anodic pole presented here (Fig. 8 B) compare quite favorably with the results of Frey et al., with the maximum transmembrane voltage peaking at 1.4 V, decreasing to 0.9 V by the end of the pulse plateau, and then decreasing to ∼0 V within 40 ns of the end of the pulse.

The transmembrane voltage peak is somewhat later and broader (in time) in the experiment of Frey et al. (37) than in the active model presented here (Fig. 8 B). The difference between the times at which the transmembrane voltage peaks, could result from differences in membrane and electrolyte parameters. The broader transmembrane voltage peak measured by Frey et al. may be attributed, at least in part, to the spatial and temporal averaging inherent in their method. The transmembrane voltage of Frey et al. is calculated from the fluorescence of a voltage-sensitive dye over an extended region of each pole with a temporal resolution of 5 ns (37), whereas the transmembrane voltage at the poles shown here (Fig. 8 B) is not spatially or temporally averaged. Given the narrowness of the transmembrane voltage peak in both space (Fig. 7, D–F) and time (Fig. 8 B), the methods of Frey et al. would cause a broadening of the measured transmembrane voltage peak (by the time response of the measurement, 5 ns) in comparison to the theoretical methods used here.

Notably, the transmembrane voltage at the cathodic pole in the study of Frey et al. is a factor of ∼2.5 smaller than the transmembrane voltage at the anodic pole (37) and the transmembrane voltage at both poles in this study (Fig. 8 B). Asymmetry in transmembrane voltage and molecular transport has been noted in previous studies of conventional electroporation, with the polarity of the asymmetry depending on cell type (62–64). The resting potential may play a role (50), particularly for smaller applied fields, and differing lipid compositions of the inner and outer leaflets of the lipid bilayer may also be important. However, electroporation experiments on vesicles (65), which lack resting a potential and have identical inner and outer leaflet composition, suggest that there must be more a fundamental causes of asymmetry, perhaps related to permanent lipid dipoles (65). Such biophysical features have not been included in the electroporation model used here, and therefore any asymmetry that results from such features cannot be described by this model.

Passive and active cell models

A recent passive cell model with two concentric, spherical membranes with identical electrical properties was used to examine the transmembrane voltages of the membranes in response to pulses ranging from 20 ns to 20 μs. The transmembrane voltage of the inner membrane was found to never exceed that of the outer membrane (31).

More recently, a very similar passive model was developed and used to thoroughly examine the transmembrane voltages of concentric, spherical PM and organelle membrane in response to submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter trapezoidal pulses (32). The authors rigorously derived analytical expressions for the transmembrane voltage as functions of frequency and position on the membranes. For the plasma (10 μm radius) and organelle membranes (3 μm radius) with the same electrical parameters, the organelle transmembrane voltage is much less than the cell transmembrane voltage for low frequencies (<∼0.1 MHz) but approaches the cell transmembrane voltage for higher frequencies (>∼1 MHz). The transition occurs as the membrane impedance is increasingly determined by the membrane dielectric properties, which increases the intracellular electric field magnitude to almost as large as the extracellular field magnitude (32).

The article (32) then explored the intracellular membrane electrical parameter space to demonstrate that for certain membrane parameters the organelle transmembrane voltage can exceed the cell transmembrane voltage by a factor of ∼2 at particular frequencies. It also examined the temporal cell and organelle transmembrane voltages in response to a trapezoidal 150 kV/cm pulse with 1 ns rise- and fall-times and a 10 ns plateau. Note that the applied electric field magnitude is not particularly important for passive models because the results scale linearly with the electric field magnitude. However, because of the high frequency content of the short pulse, the transmembrane voltages of the cell and organelle are very similar for the duration of the pulse, actually reaching 8 V by the end of the pulse (32). Similarly, in the active model presented here, the cell and organelle responses are very similar (Fig. 8), but because of electroporation, the transmembrane voltages do not exceed 1.4 V, a much smaller value. By adjusting the organelle parameters, the authors were able to make the organelle transmembrane voltage exceed the cell transmembrane voltages such that the organelle transmembrane voltage reaches 26 V by the end of the pulse while the cell transmembrane voltage reaches 8 V. This is offered as evidence that it may be possible to perturb the intracellular membranes without perturbing the PM. Indeed, this may be true for very special pulses if the organelle membranes do in fact have electrical properties that allow them to charge faster than the PM in response to pulses with high frequency content. However, there is no reason to think that this is a general, robust effect of submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses. There is no evidence that a PM can withstand 8 V without perturbation (consistent with all MD results to date). A more reasonable explanation for the apparent intracellular effects without measured changes in the PM is that the experimental methods are indirect, limited by the measurement signal/noise ratio, and fundamentally different for the PM and organelle membranes.

Several articles (1,33,35,55) preceding this one have presented active cell models based on the TLM (33,35,55) and the MTNM (1,33), and these models exhibited supra-electroporation in response to short duration, large magnitude pulses. The TLM cell model with several organelles (55) provides the most biologically realistic cell model system to date. The organelle membranes were electroporated along with the PM in response to submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses. Subsequent TLM and MTNM models (33) used the same cell system as that used here but without resting potentials. As in the passive TLM and MTNM comparison (41), the MTNM produces more accurate results with much greater efficiency than the TLM, though the results of both models are quite similar generally, showing electroporation of the PM and organelle membranes (33).

Passive models are convenient insofar as they are straightforward to implement and allow frequency-domain analysis of cell systems. However, electroporation is a complicated, highly nonlinear, hysteretic process that dramatically alters the subsequent response of a cell to a pulsed electric field, and passive models quite simply lack the appropriate interaction mechanisms to describe this response. Passive models can only make reasonable predictions before the cell membranes electroporate, which the active model predicts occurs after only ∼3 ns for a 71 ns, 95 kV/cm pulse (Fig. 8, B and C). Passive models predict that the cell interior is essentially only accessed by displacement currents (Fig. 9) and therefore predict that the intracellular electric field peaks and then decreases as the pulse progresses (during the plateau phase) and the PM increasingly shields the cell interior. However, the active model exhibits very different behavior and is consistent with experiments and MD simulations. PM electroporation causes the conduction current to dominate the displacement current, resulting in a large and relatively constant intracellular electric field for most of the pulse examined here (Fig. 9).

Moreover, the electrical perturbation of the cell is predicted to be long-lived, lasting until the pore density sufficiently decreases for the cell and organelles to reestablish resting potentials, which takes ∼20 times the assumed pore lifetime (No/α = 3.3 ms), here 70 ms. The passive model fails to describe this predicted perturbation, which may significantly effect cell behavior by gating membrane channels (66). Not only do passive models fail to accurately capture the fundamental electrical response of a cell to a pulsed electric field, they also fail to make any predictions about secondary effects of the pulse because they cannot illustrate the spatial distribution or degree of electroporation and associated permeabilization of cell membranes.

Some passive models in the literature have been rigorously derived (32), but because they are based on the assumption that membranes do not electroporate, they are intrinsically limited in their ability to make useful predictions about the behavior of cells and organelles in response to pulsed electric fields.

Other electrical models in the literature are fundamentally incorrect, based on simple equations for charging of spherical dielectric shells that are erroneous on the very short timescales of ultrashort pulses (6,7,11,12,15,18,19,23,25). In Schoenbach et al. (15), for example, the authors obtain expressions for the transmembrane voltages of the PM and an organelle membrane (with identical electrical properties), and these expressions indicate that the transmembrane voltage of the organelle transiently exceeds that of the PM. However, this result is in error. The authors incorrectly assume that the voltage drop across an entire cell, Vcell, in an applied electric field, Eapp, is the steady-state value Vcell = fEappD, where f is a geometric coefficient (f = 1.5 for sphere and f = 2 for cylinder) and D is the cell diameter. In fact, Vcell is a time-dependent quantity, and the steady-state expression used in Schoenbach et al. (15) is inappropriate during a rapidly rising pulse. This error then propagates, leading to the prediction that the intracellular electric field initially exceeds Eapp by factor f, which results in initially faster charging of the organelle membrane. In fact, for a passive model with the assumptions made by the authors, the intracellular electric field is initially almost identical to Eapp (due to membrane displacement current) and then drops off as the PM shields the cell interior, and the transmembrane voltage of the organelle never exceeds that of the PM. This has been explicitly shown by others in the frequency domain (32,67) and time domain (31,32).

Many electrical cell models, both active and passive, use an effective intracellular conductivity that is approximately four-times smaller than the extracellular conductivity because of the large volume of organelles that exclude intracellular current flow. For consistency with previous models (32), we used σi = σe/4 = 0.3 S/m in the primary cell model here. However, the tremendous increase in the conductance of the PM and organelle membranes suggests that this intracellular conductivity representation is not reasonable for pulses causing supra-electroporation because the organelle membrane electroporation allows significant conduction current flow through organelles. That is, the organelles cannot be considered excluded volumes.

For this reason, Fig. 10 shows the passive and active responses to the 71 ns, 95 kV/cm pulse in a model for which σi = σe = 1.2 S/m. In contrast to the primary model examined with σi = σe/4 = 0.3 S/m, in which the intracellular electric field exceeds the extracellular electric field (Fig. 6), in this version of the cell model the electric field is initially uniform throughout the intracellular and extracellular spaces of the active and passive models due to the low membrane impedance and identical intracellular and extracellular conductivities (Fig. 10 A). For the passive model, the electric field becomes considerably less uniform at the end of the pulse plateau as the electric field is excluded from the interior of the cell and organelles. In contrast, for the active model, the electric field remains uniform at the end of the pulse plateau as the electroporated membranes allow continued electric field penetration of the cell and membrane interiors. This is consistent with an earlier models in which the cell becomes “electrically invisible” by supra-electroporation (33,55). The spatial patterns of electroporation are very similar for both active models (Figs. 6 and 10), though the time courses of electroporation vary slightly.

FIGURE 10.

Passive and active cell responses for σi = σe = 1.2 S/m. The electric potential and pore density are shown for the passive and active models at (A) 6 ns and (B) 61 ns for σi = σe = 1.2 S/m. For the active model, pore density is indicated by the white line thickness (1014, 1015, 1016 m−2). Twenty-one contour lines are uniformly spaced between the extreme values of their associated grayscale bars. (A) Initially, the electric field magnitude in the intracellular and extracellular regions is approximately equal. (B) For the passive model, at the end of the pulse plateau the intracellular electric field magnitude is significantly smaller than the extracellular electric field magnitude. For the active model, the electric field magnitude in the intracellular and extracellular regions remains approximately equal because of the high conductance of the electroporated membranes.

Because the actual, as opposed to effective, conductivity of the intracellular space of a cell is ∼1.2 S/m and the cell supra-electroporation effectively eliminates the intracellular excluded volume that has traditionally motivated the use of decreased effective intracellular conductivity, we suggest the use of σi = 1.2 S/m in future models used to study supra-electroporation.

The active model presented here, while containing approximations, is consistent with experimental results and MD simulations to date and shows the primary features of an electroporation-based model's response of a cell to a submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulse.

Perspective

There are assumptions made in this active cell model. However, it appears to be robust in quantitatively characterizing the electrical response of cells to large pulsed electric fields. Pore populations that develop in membranes in response to large applied electric fields quickly reduce the transmembrane voltage to ∼1 V. A general feature of membrane electroporation models is rapid creation of conducting pores, a feedback mechanism that tends to discharge the membrane both during and after a pulse. This is supported by experiments on different timescales and by MD on the nanosecond timescale (37,48,61). For this reason, the electrical predictions are somewhat independent of the details of the pore properties and pore populations. Further, electroporation-based applications will require understanding of more than just the electrical responses of cells and tissue. Specifically, biological effects and medical interventions are likely to depend on the pore size distribution and corresponding molecular transport and all other mechanisms (e.g., channel gating) by which large fields can alter cell biochemistry. Therefore, future models should increasingly address fundamental questions involving the molecular nature of pores, biological realism, and coupled molecular transport at the subcellular, cellular, and multicellular levels.

Electroporation models and their parameters were motivated by conventional electroporation, in which pore densities are quite low relative to those of supra-electroporation. Thus, there is an emerging question as to the limits of current electroporation theory and, indeed, the fundamental molecular structure of a pore. Given a large enough pulse, for example, the asymptotic model can predict total pore areas that exceed the membrane area, which is impossible. There are, perhaps, simple ways to extend the current electroporation theory, such as modifying the differential equation for pore creation (Eq. 5) such that pore creation strongly decreases at high pore densities. New insights from experimental results and fundamental theory and simulation, such as MD, are likely to be necessary.

Here the highest pore density predicted is ∼5 × 1016 m−2 at the membrane poles, which corresponds to a fractional aqueous pore area of 0.1. Considering the significant fraction of the membrane area occupied by protein (68,69), the fractional aqueous pore area of the lipid regions is still higher. Given the assumed toroidal conformation of hydrophilic pores, this implies that essentially the entire membrane areas in the regions of such high pore density are significantly structurally perturbed. As such, the results should be viewed with the qualification that, in the limit of high pore densities, the physical behavior of a membrane may vary significantly from that predicted, and, indeed, the very nature of a pore on such short timescales and at such high pore densities may be very different from the usual toroidal pores. It may also be that the molecular structure of pores does not change on shorter timescales or at higher pore densities, but rather there are self-limiting features of electroporation that are not captured by current models. For behavior at the cellular level, the MTNM, on which the models are based, is quite robust and should easily accommodate new electroporation models.

This cell model has some key features of a cell, including organelles and spatially distributed resting potential sources, but to the biologist, it is still simplistic. However, cells with considerable structural complexity including many organelles (Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, etc.) could be modeled with the current methods. Two dimensions and circular membranes were used here to facilitate data presentation and to address physical issues by using traditional geometry (circles). However, more complicated structures without symmetry can easily be meshed and simulated. Increasingly biologically realistic cell models will help electroporation research engage the biological research community.

CONCLUSION

Submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses result in diverse cellular effects that are inconsistent with passive models. We therefore advocate pursuit of active models that are based on mechanistic hypotheses that can be represented by one-dimensional equations and then assigned to MTNM/TLM models. To date, such models predict responses that are consistent with observed cellular responses and are useful for hypothesizing mechanisms by which submicrosecond, megavolt-per-meter pulses may interact with biological membrane systems and lead to complex downstream cellular events, such as apoptosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. T. Esser, T. R. Gowrishankar, D. A. Stewart, J. F. Kolb, and P. T. Vernier for valuable discussions and K. G. Weaver for computer assistance.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant No. R01-GM63857), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and Department of Defense Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative Grant on Subcellular Responses to Narrowband and Wideband Radio Frequency Radiation, and Graduate Research Fellowships from the Whitaker Foundation and National Science Foundation.

APPENDIX A: MESHED TRANSPORT NETWORK METHOD

Constitutive relations

Fig. 3 A shows a typical triangular mesh and its associated VCs, which are polygons enclosing the region closer to the node associated with the VC than to any other node. The sides of the VC bisect the triangle edges at right angles. Fig. 3 B shows a pair of adjacent VCs j and k and the triangle edge connecting their nodes. The VC interface has length wj,k, the triangle edge has length lj,k, and the system has depth d. The area of the VC interface is therefore Aj,k = wj,kd. There is an electric field  current density

current density  and outward-pointing unit normal vector

and outward-pointing unit normal vector  at the VC interface.

at the VC interface.

In a homogeneous, passive medium, the current density  may be expressed as the sum of conduction and displacement current density contributions:

may be expressed as the sum of conduction and displacement current density contributions:

|

(12) |

Here,

|

(13) |

The current densities and electric field can be expressed as the sums of components normal and parallel to the VC interface:

|

(14) |

It is clear from Fig. 3 B that the components parallel to the VC interface do not contribute to transport between the VCs. That is,

|

(15) |

|

(16) |

The currents flowing from VC j to VC k are the product of the interface area Aj,k = wj,kd and the dot product of the current densities with the outward-pointing unit normal vector:

|

(17) |

Substituting Eq. 16, the currents become

|

(18) |

The components of the current densities normal to the VC interface may be expressed in terms of the normal component of the electric field at the VC interface:

|

(19) |

Substituting for the current densities, the currents become

|

(20) |

A first-order approximation to the normal component of the electric field is

|

(21) |

where (Δφ)j,k = φk – φj and lj,k is the distance between nodes j and k. Substituting for the perpendicular electric field component, the currents become

|

(22) |

The terms in the currents may be regrouped as the products of time-independent and time-dependent quantities:

|

(23) |

Defining

|

(24) |

the currents may be expressed as

|

(25) |

Thus, the total current flowing from VC j to VC k is

|

(26) |

Conservation relations

Conservation requires

|

(27) |

In the discretized two-dimensional system, these relations become

|

(28) |

where Nj is the number of VCs adjacent to VC j. Simplifying,

|

(29) |

Summing the conduction and displacement current contributions, the total current leaving VC j must also equal zero:

|

(30) |

Substituting the constitutive relation (Eq. 26) yields the system of equations governing transport,

|

(31) |

for each VC j.

Editor: Joshua Zimmerberg.

References

- 1.Smith, K. C. 2006. Cell and Tissue Electroporation. Master's thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- 2.Abidor, I. G., V. B. Arakelyan, L. V. Chernomordik, Y. A. Chizmadzhev, V. F. Pastushenko, and M. R. Tarasevich. 1979. Electric breakdown of bilayer membranes. I. The main experimental facts and their qualitative discussion. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 6:37–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weaver, J. C., and Y. A. Chizmadzhev. 1996. Theory of electroporation: a review. Bioelectrochem. Bioenerg. 41:135–160. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver, J. C. 2003. Electroporation of biological membranes from multicellular to nano scales. IEEE Trans. Dielect. Elect. Ins. 10:754–768. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teissie, J., M. Golzio, and M. P. Rols. 2005. Mechanisms of cell membrane electropermeabilization: a minireview of our present (lack of?) knowledge. BBA Gen. Subjects. 1724:270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoenbach, K. H., S. J. Beebe, and E. S. Buescher. 2001. Intracellular effect of ultrashort electrical pulses. Bioelectromagnetics. 22:440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenbach, K. H., S. Katsuki, R. H. Stark, E. S. Buescher, and S. J. Beebe. 2002. Bioelectrics—new applications for pulsed power technology. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 30:293–300. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beebe, S. J., P. M. Fox, L. J. Rec, K. Somers, R. H. Stark, and K. H. Schoenbach. 2002. Nanosecond pulsed electric field (nsPEF) effects on cells and tissues: apoptosis induction and tumor growth inhibition. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 30:286–292. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beebe, S. J., J. White, P. F. Blackmore, Y. P. Deng, K. Somers, and K. H. Schoenbach. 2003. Diverse effects of nanosecond pulsed electric fields on cells and tissues. DNA Cell Biol. 22:785–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beebe, S. J., P. M. Fox, L. J. Rec, L. K. Willis, and K. H. Schoenbach. 2003. Nanosecond, high-intensity pulsed electric fields induce apoptosis in human cells. FASEB J. 17:1493–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buescher, E. S., and K. H. Schoenbach. 2003. Effects of submicrosecond, high intensity pulsed electric fields on living cells – intracellular electromanipulation. IEEE Trans. Dielect. Elect. Ins. 10:788–794. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deng, J. D., K. H. Schoenbach, E. S. Buescher, P. S. Hair, P. M. Fox, and S. J. Beebe. 2003. The effects of intense submicrosecond electrical pulses on cells. Biophys. J. 84:2709–2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hair, P. S., K. H. Schoenbach, and E. S. Buescher. 2003. Sub-microsecond, intense pulsed electric field applications to cells show specificity of effects. Bioelectrochemistry. 61:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernier, P. T., Y. H. Sun, L. Marcu, S. Salemi, C. M. Craft, and M. A. Gundersen. 2003. Calcium bursts induced by nanosecond electric pulses. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 310:286–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenbach, K. H., R. P. Joshi, J. F. Kolb, N. Y. Chen, M. Stacey, P. F. Blackmore, E. S. Buescher, and S. J. Beebe. 2004. Ultrashort electrical pulses open a new gateway into biological cells. Proc. IEEE. 92:1122–1137. [Google Scholar]

- 16.White, J. A., P. F. Blackmore, K. H. Schoenbach, and S. J. Beebe. 2004. Stimulation of capacitative calcium entry in HL-60 cells by nanosecond pulsed electric fields. J. Biol. Chem. 279:22964–22972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen, N. Y., K. H. Schoenbach, J. F. Kolb, R. J. Swanson, A. L. Garner, J. Yang, R. P. Joshi, and S. J. Beebe. 2004. Leukemic cell intracellular responses to nanosecond electric fields. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 317:421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vernier, P. T., Y. H. Sun, L. Marcu, C. M. Craft, and M. A. Gundersen. 2004. Nanoelectropulse-induced phosphatidylserine translocation. Biophys. J. 86:4040–4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vernier, P. T., Y. H. Sun, L. Marcu, C. M. Craft, and M. A. Gundersen. 2004. Nanosecond pulsed electric fields perturb membrane phospholipids in T lymphoblasts. FEBS Lett. 572:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nuccitelli, R., U. Pliquett, X. H. Chen, W. Ford, R. J. Swanson, S. J. Beebe, J. F. Kolb, and K. H. Schoenbach. 2006. Nanosecond pulsed electric fields cause melanomas to self-destruct. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 343:351–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vernier, P. T., M. J. Ziegler, Y. H. Sun, W. V. Chang, M. A. Gundersen, and D. P. Tieleman. 2006. Nanopore formation and phosphatidylserine externalization in a phospholipid bilayer at high transmembrane potential. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128:6288–6289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun, Y. H., P. T. Vernier, M. Behrend, J. J. Wang, M. M. Thu, M. Gundersen, and L. Marcu. 2006. Fluorescence microscopy imaging of electroperturbation in mammalian cells. J. Biomed. Opt. 11:024010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vernier, P. T., Y. H. Sun, and M. A. Gundersen. 2006. Nanoelectropulse-driven membrane perturbation and small molecule permeabilization. BMC Cell Biol. 7:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jordan, D. W., M. D. Uhler, R. M. Gilgenbach, and Y. Y. Lau. 2006. Enhancement of cancer chemotherapy in vitro by intense ultrawideband electric field pulses. J. Appl. Phys. 99:094701. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun, Y. H., P. T. Vernier, M. Behrend, L. Marcu, and M. A. Gundersen. 2005. Electrode microchamber for noninvasive perturbation of mammalian cells with nanosecond pulsed electric fields. IEEE T. Nanobiosci. 4:277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pakhomov, A. G., J. F. Kolb, J. A. White, R. P. Joshi, S. Xiao, and K. H. Schoenbach. 2007. Long-lasting plasma membrane permeabilization in mammalian cells by nanosecond pulsed electric field (nsPEF). Bioelectromagnetics. 28:655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pakhomov, A. G., R. Shevin, J. A. White, J. F. Kolb, O. N. Pakhomova, R. P. Joshi, and K. H. Schoenbach. 2007. Membrane permeabilization and cell damage by ultrashort electric field shocks. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. In press, corrected proof. Http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6WB5–4NT9J8N–1/2/87d6a136629a4a39f572c0a4e95e05b4. [DOI] [PubMed]