Abstract

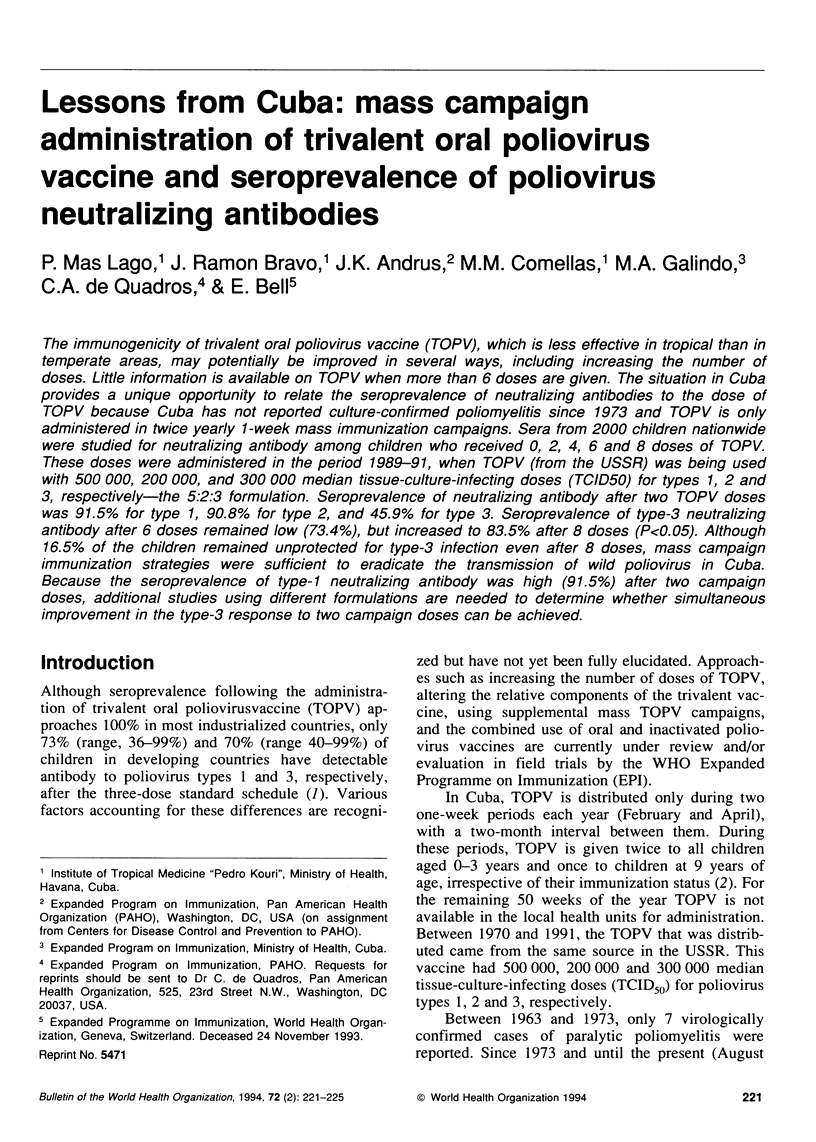

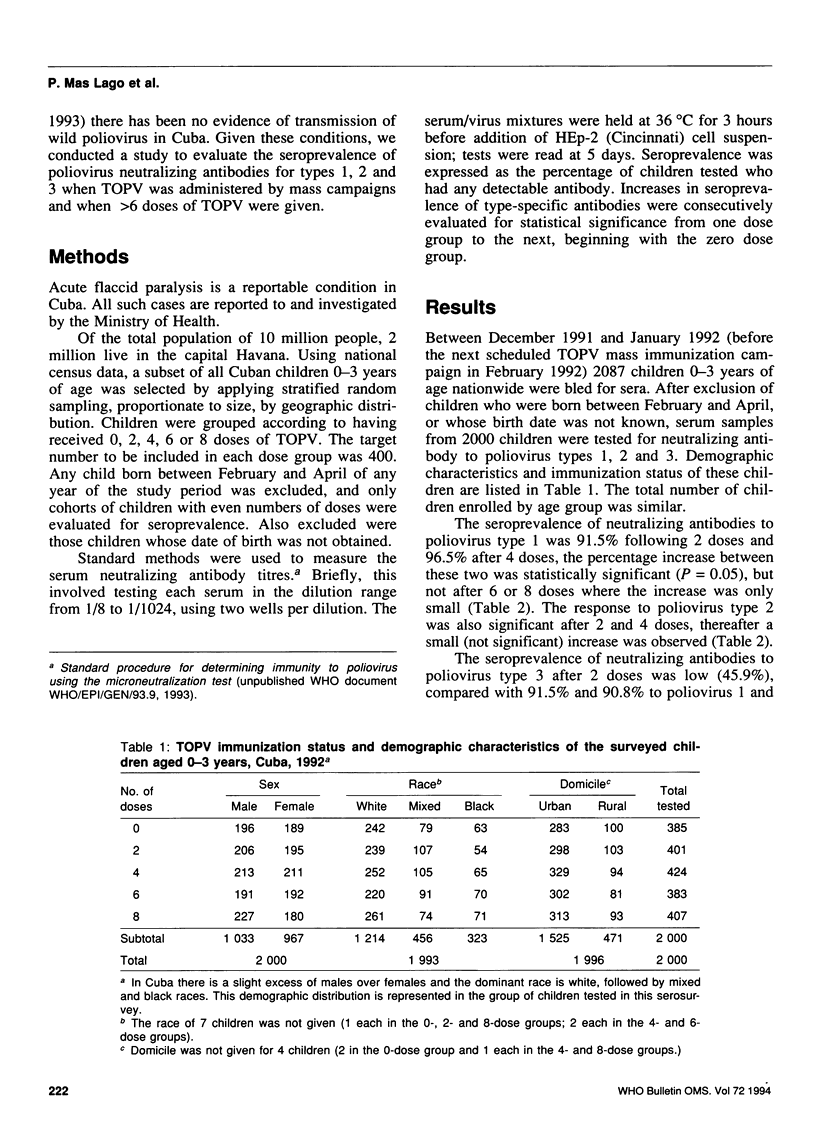

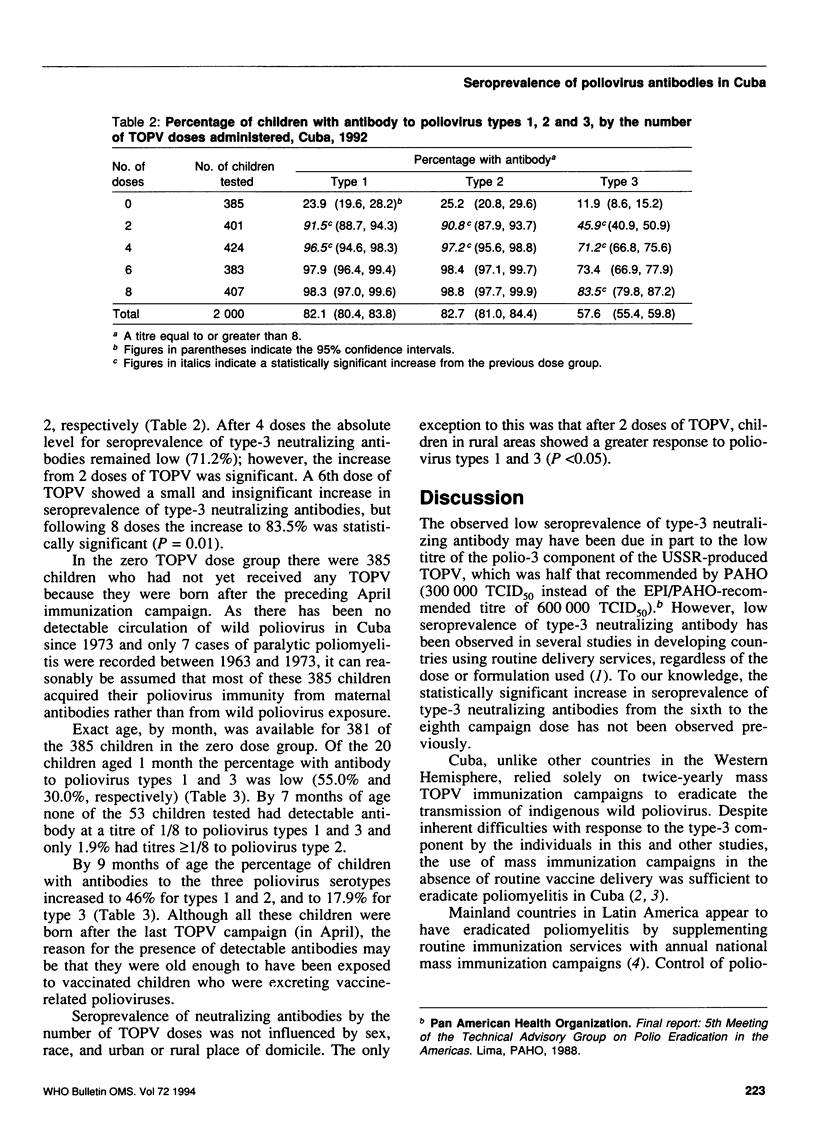

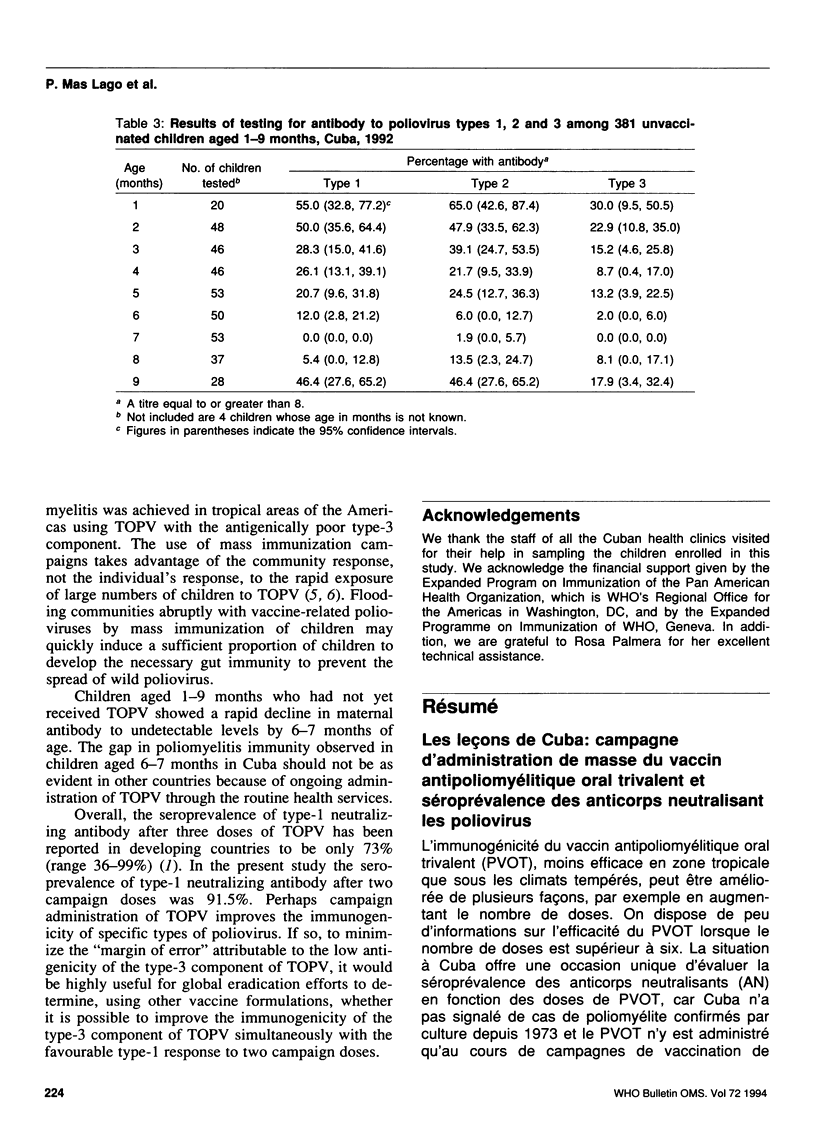

The immunogenicity of trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine (TOPV), which is less effective in tropical than in temperate areas, may potentially be improved in several ways, including increasing the number of doses. Little information is available on TOPV when more than 6 doses are given. The situation in Cuba provides a unique opportunity to relate the seroprevalence of neutralizing antibodies to the dose of TOPV because Cuba has not reported culture-confirmed poliomyelitis since 1973 and TOPV is only administered in twice yearly 1-week mass immunization campaigns. Sera from 2000 children nationwide were studied for neutralizing antibody among children who received 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8 doses of TOPV. These doses were administered in the period 1989-91, when TOPV (from the USSR) was being used with 500,000, 200,000, and 300,000 median tissue-culture-infecting doses (TCID50) for types 1, 2 and 3, respectively--the 5:2:3 formulation. Seroprevalence of neutralizing antibody after two TOPV doses was 91.5% for type 1, 90.8% for type 2, and 45.9% for type 3. Seroprevalence of type-3 neutralizing antibody after 6 doses remained low (73.4%), but increased to 83.5% after 8 doses (P < 0.05). Although 16.5% of the children remained unprotected for type-3 infection even after 8 doses, mass campaign immunization strategies were sufficient to eradicate the transmission of wild poliovirus in Cuba. Because the seroprevalence of type-1 neutralizing antibody was high (91.5%) after two campaign doses, additional studies using different formulations are needed to determine whether simultaneous improvement in the type-3 response to two campaign doses can be achieved.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- De Quadros C. A., Andrus J. K., Olivé J. M., Da Silveira C. M., Eikhof R. M., Carrasco P., Fitzsimmons J. W., Pinheiro F. P. Eradication of poliomyelitis: progress in the Americas. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991 Mar;10(3):222–229. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa E. G., Lago P. M. Epidemiological surveillance and control of poliomyelitis in the Republic of Cuba. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1987;31(4):381–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patriarca P. A., Wright P. F., John T. J. Factors affecting the immunogenicity of oral poliovirus vaccine in developing countries: review. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(5):926–939. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.5.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Cruz R. Cuba: mass polio vaccination program, 1962-1982. Rev Infect Dis. 1984 May-Jun;6 (Suppl 2):S408–S412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quadros C. A., Andrus J. K., Olive J. M., Guerra de Macedo C., Henderson D. A. Polio eradication from the Western Hemisphere. Annu Rev Public Health. 1992;13:239–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.13.050192.001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]