Abstract

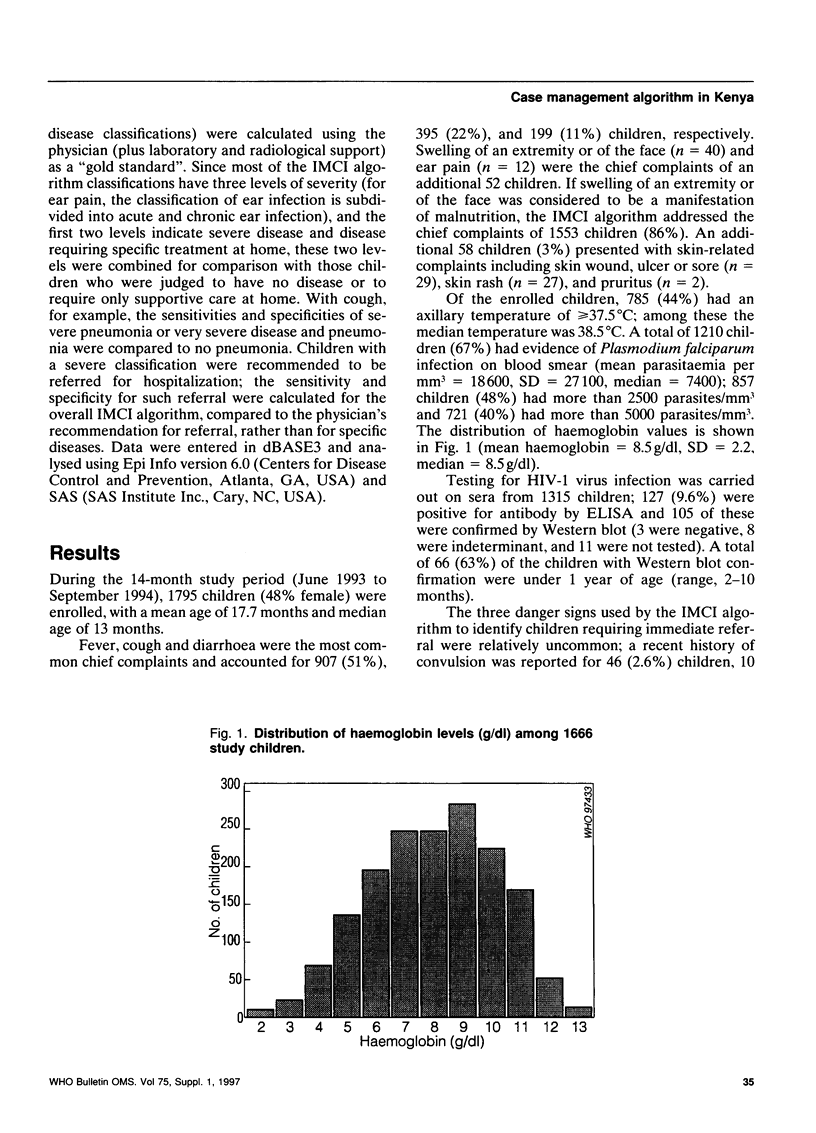

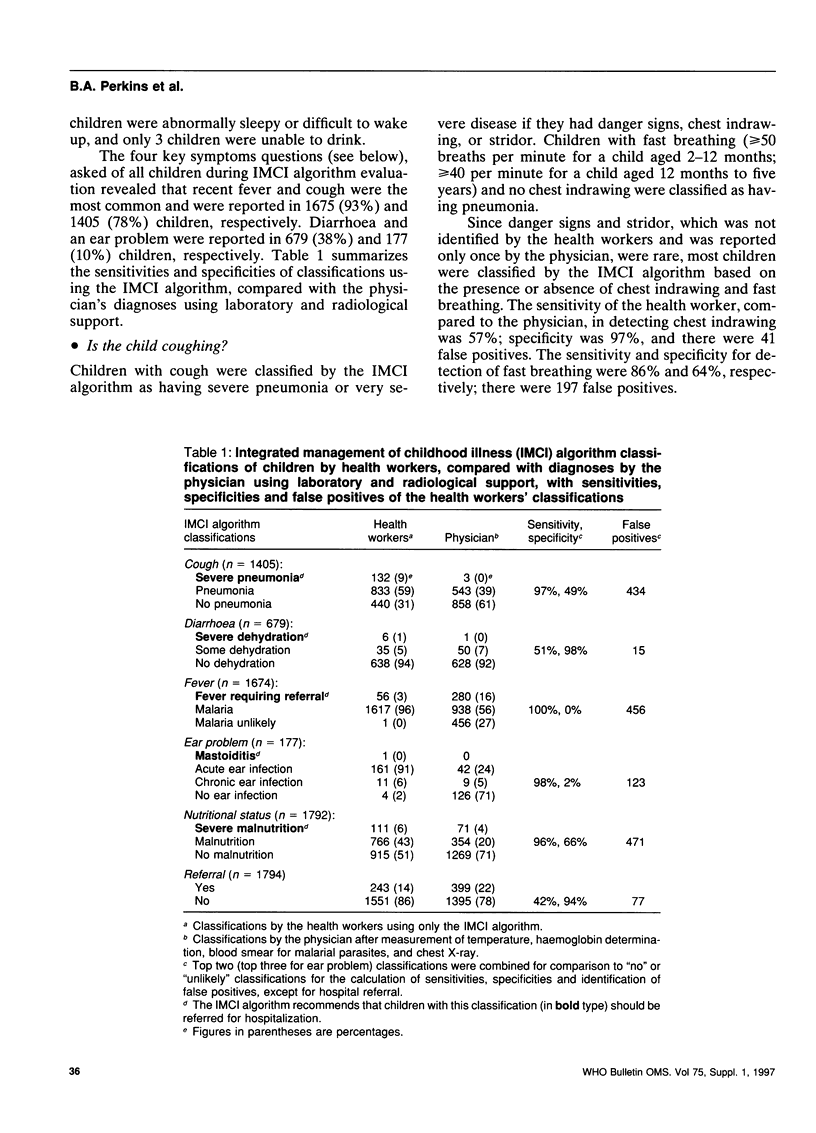

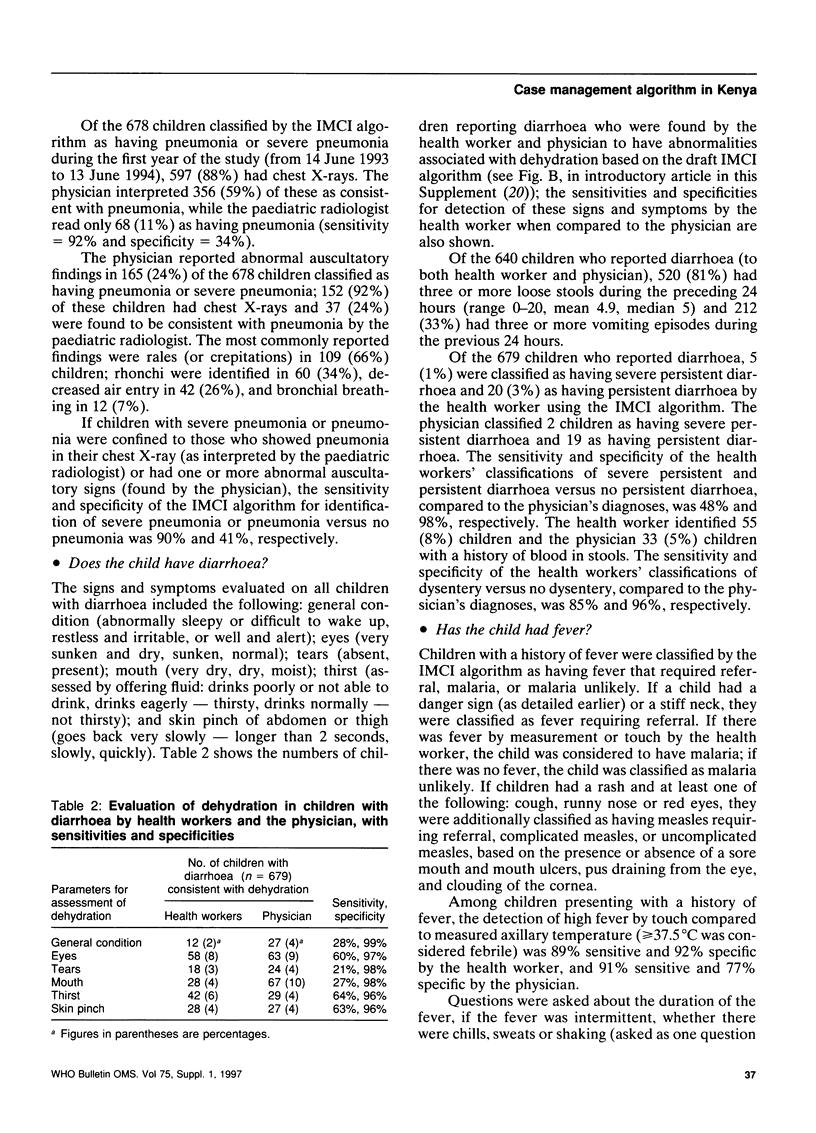

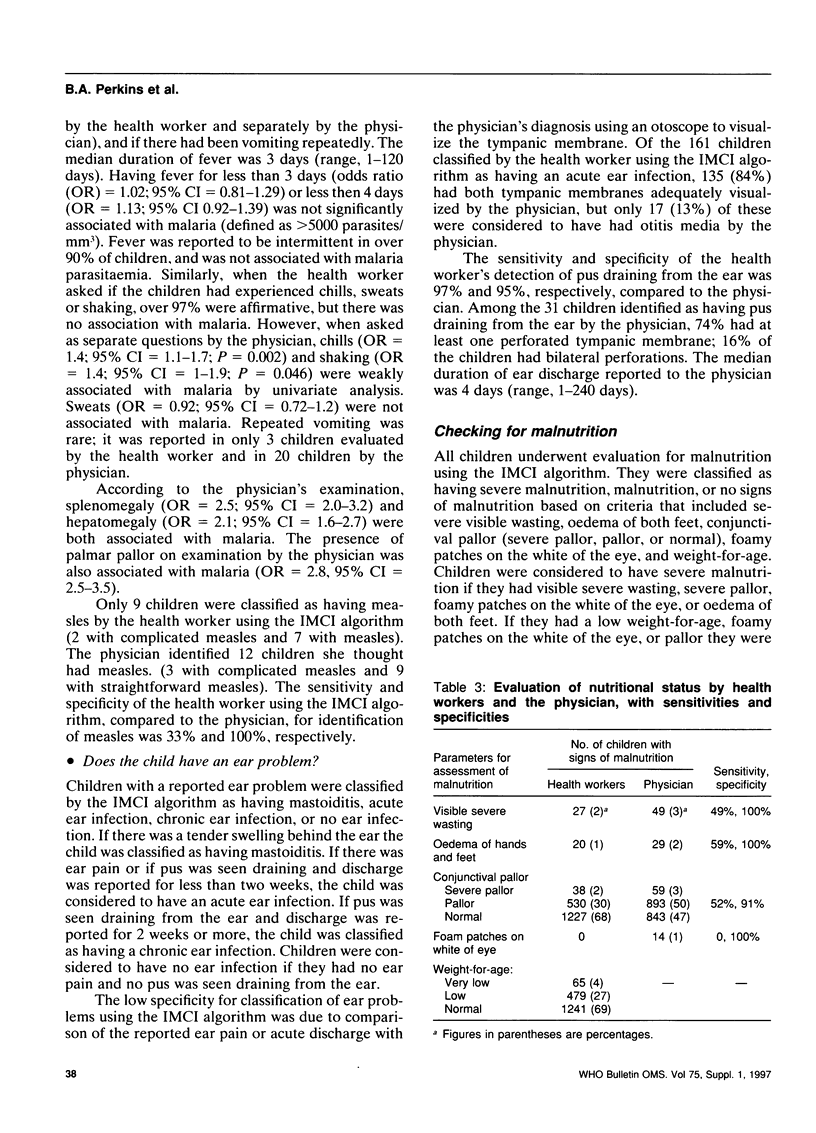

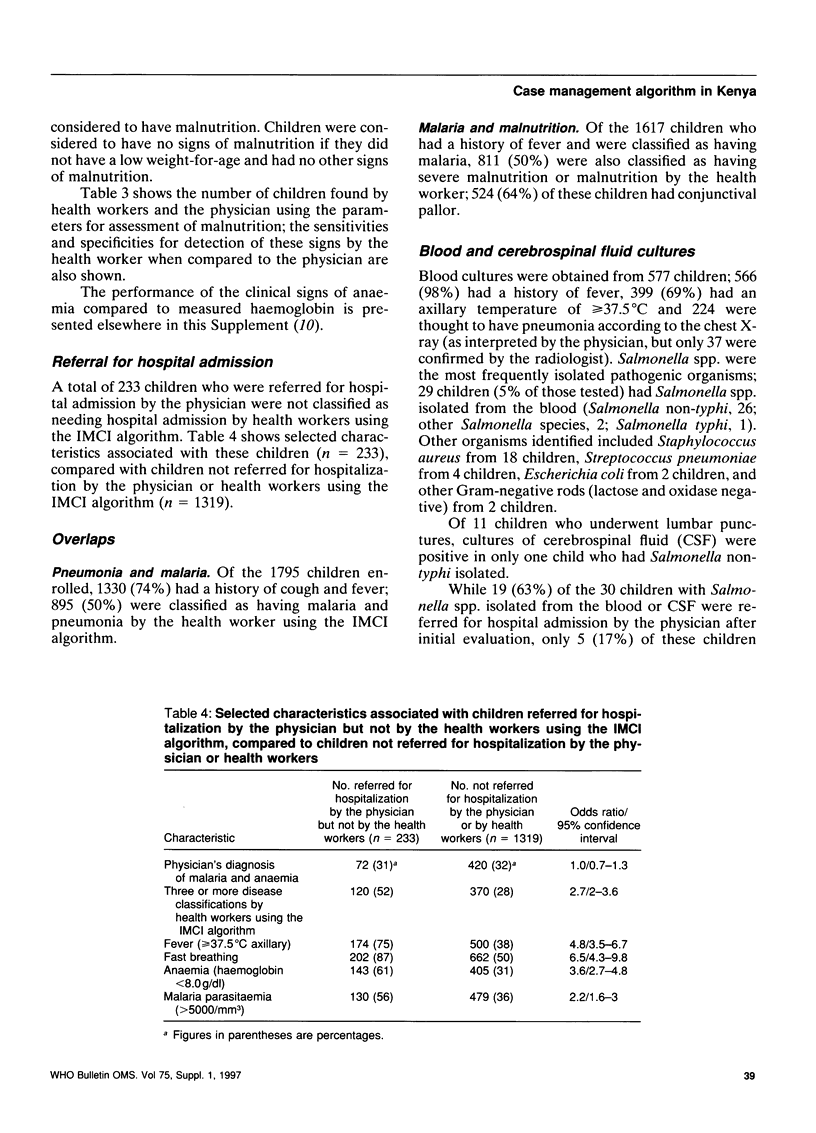

In 1993, the World Health Organization completed the development of a draft algorithm for the integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI), which deals with acute respiratory infections, diarrhoea, malaria, measles, ear infections, malnutrition, and immunization status. The present study compares the performance of a minimally trained health worker to make a correct diagnosis using the draft IMCI algorithm with that of a fully trained paediatrician who had laboratory and radiological support. During the 14-month study period, 1795 children aged between 2 months and 5 years were enrolled from the outpatient paediatric clinic of Siaya District Hospital in western Kenya; 48% were female and the median age was 13 months. Fever, cough and diarrhoea were the most common chief complaints presented by 907 (51%), 395 (22%), and 199 (11%) of the children, respectively; 86% of the chief complaints were directly addressed by the IMCI algorithm. A total of 1210 children (67%) had Plasmodium falciparum infection and 1432 (80%) met the WHO definition for anaemia (haemoglobin < 11 g/dl). The sensitivities and specificities for classification of illness by the health worker using the IMCI algorithm compared to diagnosis by the physician were: pneumonia (97% sensitivity, 49% specificity); dehydration in children with diarrhoea (51%, 98%); malaria (100%, 0%); ear problem (98%, 2%); nutritional status (96%, 66%); and need for referral (42%, 94%). Detection of fever by laying a hand on the forehead was both sensitive and specific (91%, 77%). There was substantial clinical overlap between pneumonia and malaria (n = 895), and between malaria and malnutrition (n = 811). Based on the initial analysis of these data, some changes were made in the IMCI algorithm. This study provides important technical validation of the IMCI algorithm, but the performance of health workers should be monitored during the early part of their IMCI training.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bloland P. B., Redd S. C., Kazembe P., Tembenu R., Wirima J. J., Campbell C. C. Co-trimoxazole for childhood febrile illness in malaria-endemic regions. Lancet. 1991 Mar 2;337(8740):518–520. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91299-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. C., Rahman M., D'Souza S., Chakraborty J., Sardar A. M., Yunus M. Mortality impact of an MCH-FP program in Matlab, Bangladesh. Stud Fam Plann. 1983 Aug-Sep;14(8-9):199–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falade A. G., Tschäppeler H., Greenwood B. M., Mulholland E. K. Use of simple clinical signs to predict pneumonia in young Gambian children: the influence of malnutrition. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73(3):299–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gove S. Integrated management of childhood illness by outpatient health workers: technical basis and overview. The WHO Working Group on Guidelines for Integrated Management of the Sick Child. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75 (Suppl 1):7–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gove S., Tulloch J., Cattani J., Schapira A. Usefulness of clinical case-definitions in treatment of childhood malaria or pneumonia. Lancet. 1993 Jan 30;341(8840):304–305. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92655-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klugman K. P. Pneumococcal resistance to antibiotics. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990 Apr;3(2):171–196. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masawe A. E., Nsanzumuhire H., Mhalu F. Bacterial skin infections in preschool and school children in coastal Tanzania. Arch Dermatol. 1975 Oct;111(10):1312–1316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnam A. V., Jayaraju K. Skin diseases in Zambia. Br J Dermatol. 1979 Oct;101(4):449–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redd S. C., Bloland P. B., Kazembe P. N., Patrick E., Tembenu R., Campbell C. C. Usefulness of clinical case-definitions in guiding therapy for African children with malaria or pneumonia. Lancet. 1992 Nov 7;340(8828):1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93160-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sazawal S., Black R. E. Meta-analysis of intervention trials on case-management of pneumonia in community settings. Lancet. 1992 Aug 29;340(8818):528–533. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91720-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherall D. J., Abdalla S. The anaemia of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Br Med Bull. 1982 May;38(2):147–151. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg G. A., Spitzer E. D., Murray P. R., Ghafoor A., Montgomery J., Tupasi T. E., Granoff D. M. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Haemophilus isolates from children in eleven developing nations. BOSTID Haemophilus Susceptibility Study Group. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68(2):179–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker J. R., Perkins B. A., Jafari H., Otieno J., Obonyo C., Campbell C. C. Clinical signs for the recognition of children with moderate or severe anaemia in western Kenya. Bull World Health Organ. 1997;75 (Suppl 1):97–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]