Abstract

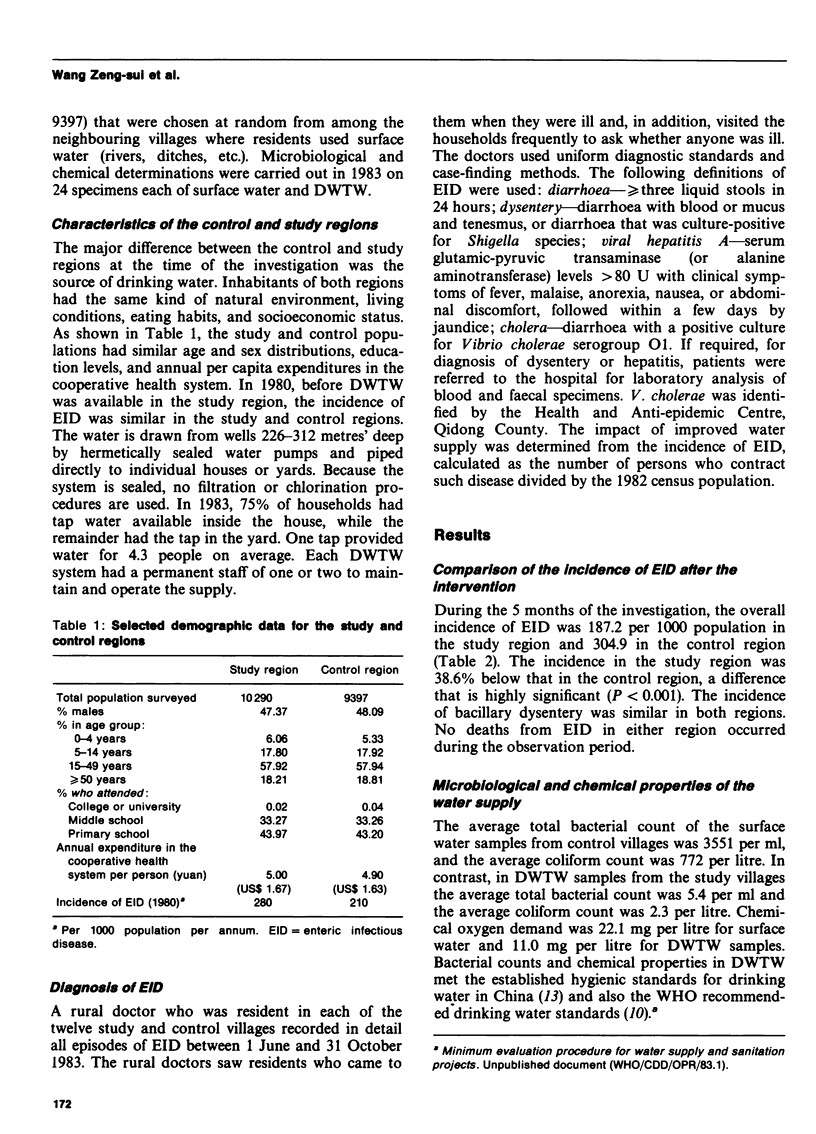

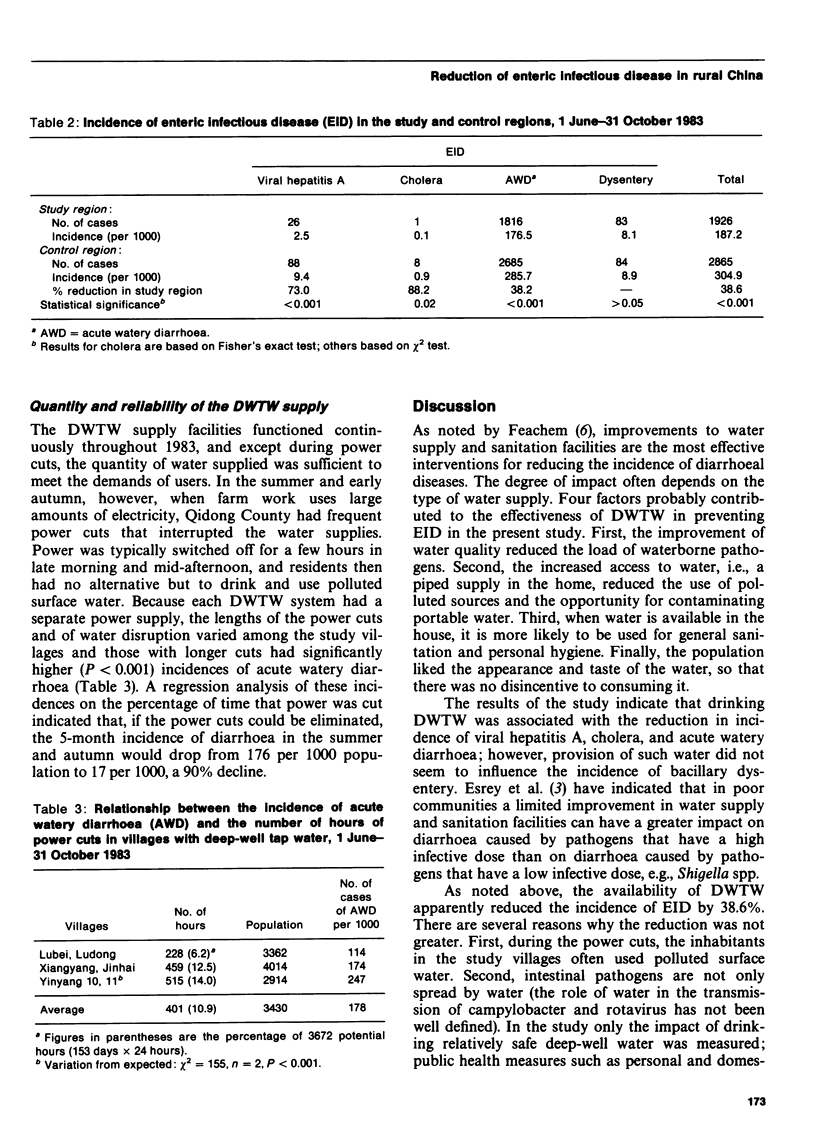

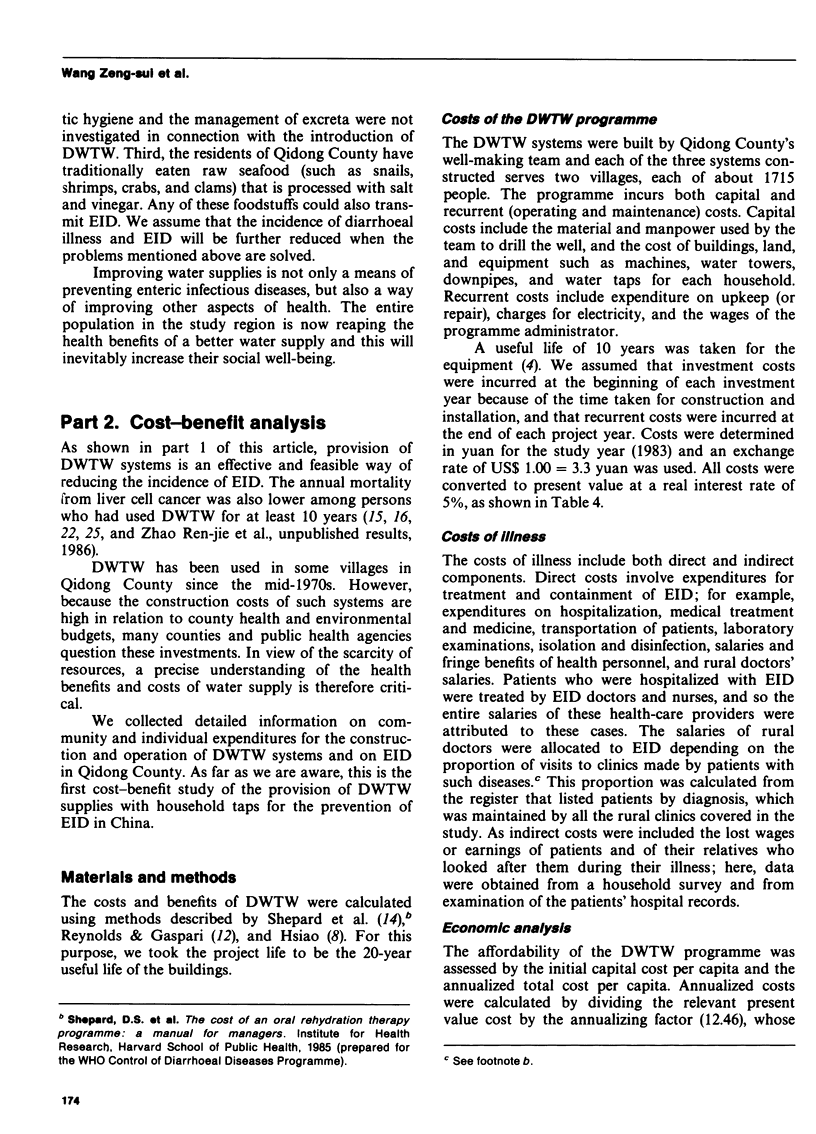

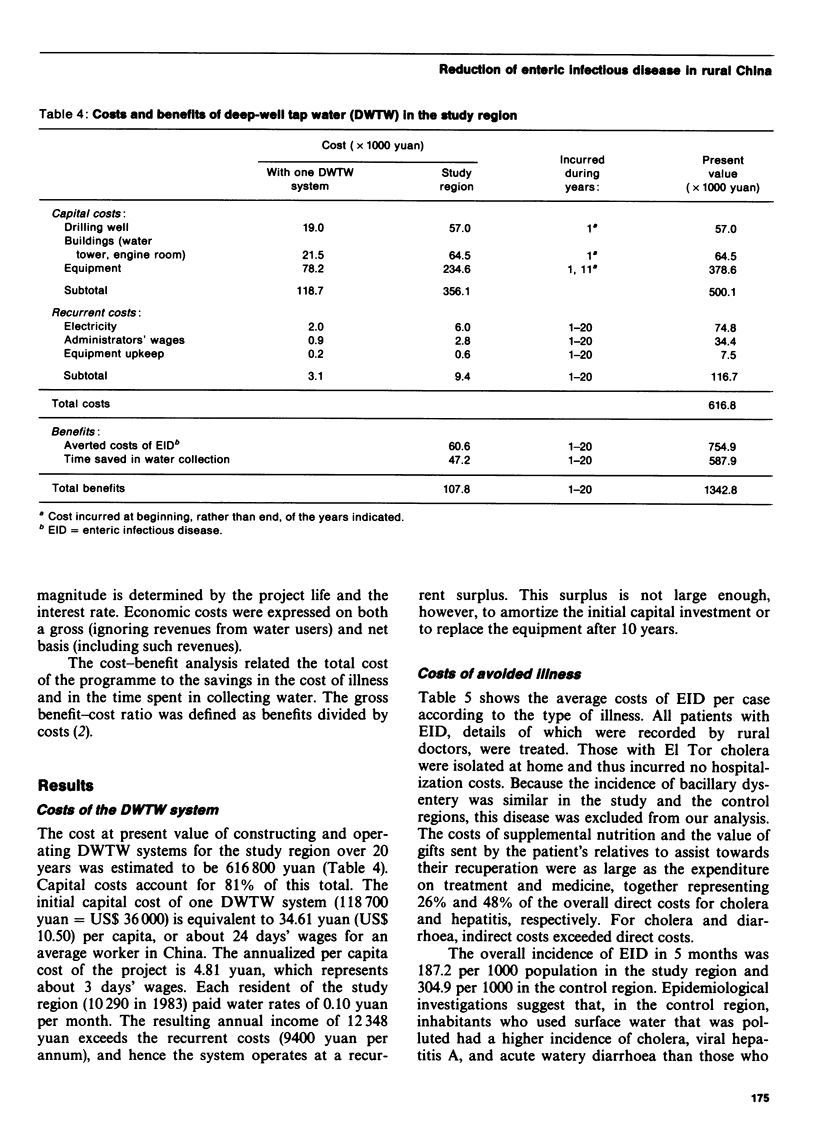

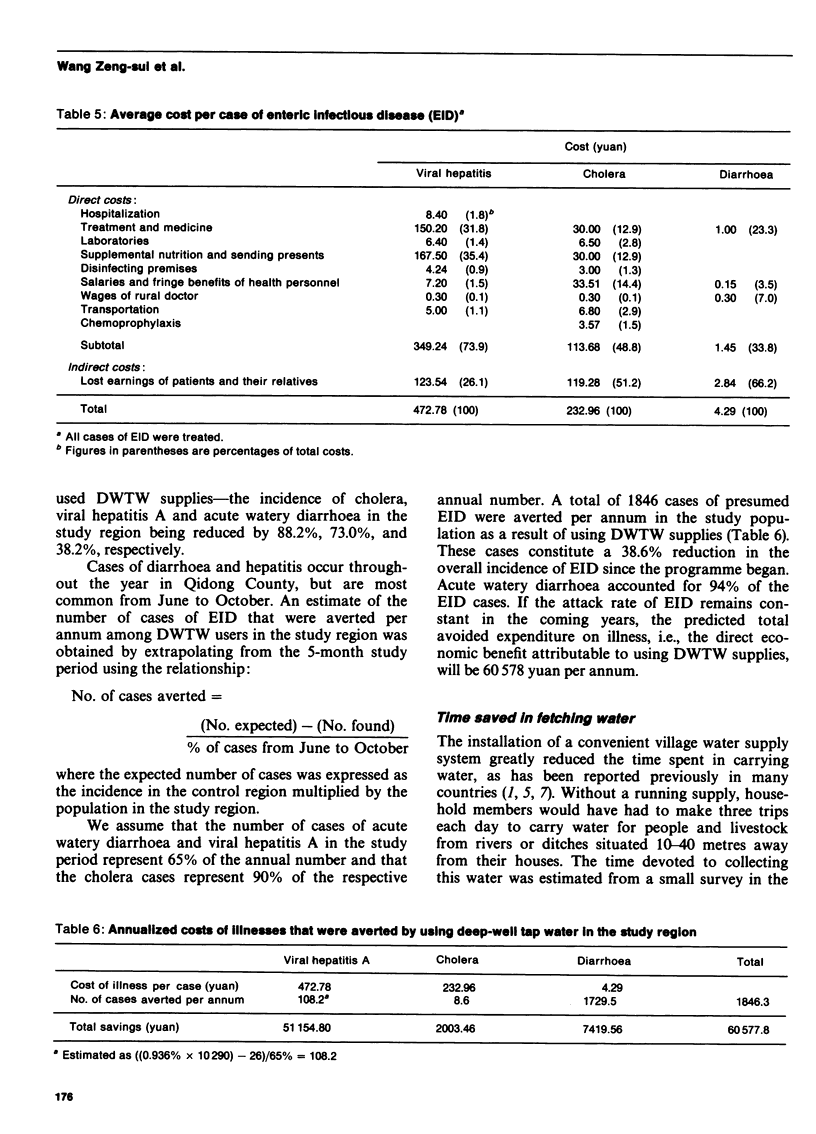

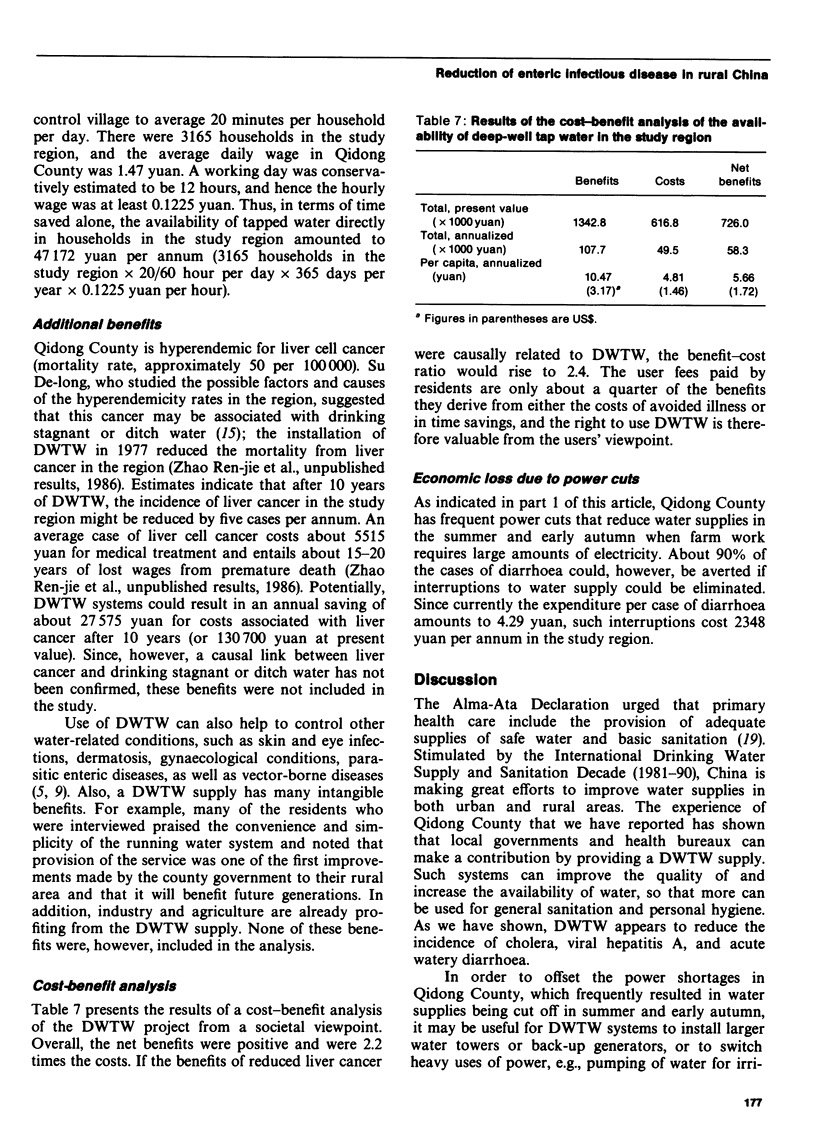

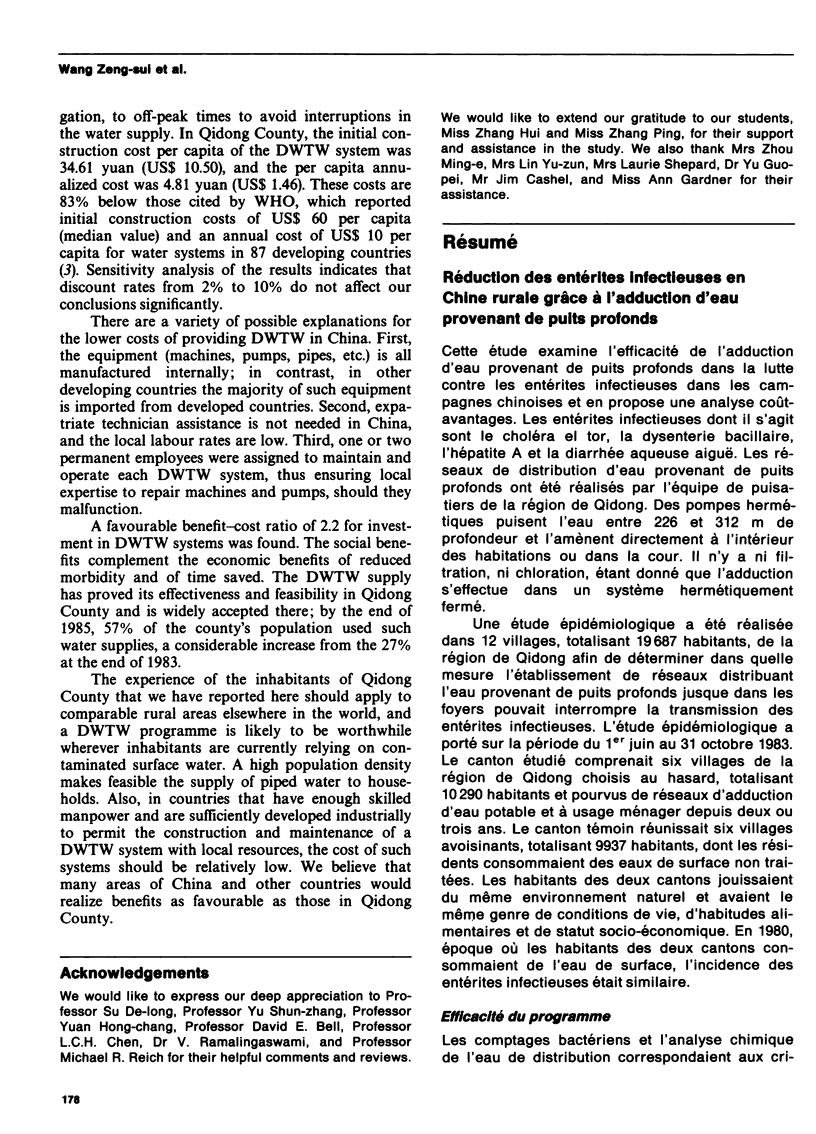

Enteric infectious disease (EID), defined here as bacillary dysentery, viral hepatitis A, El Tor cholera, or acute watery diarrhoea, is an important public health problem in most developing countries. This study assessed the impact on EID of providing deep-well tap water (DWTW) through household taps in rural China. For this purpose, we compared the incidence of EID in six study villages (population, 10,290) in Qidong County that had DWTW with that in six control villages (population 9397) that had only surface water. Both the bacterial counts and chemical properties of the DWTW met established hygiene standards for drinking water. The incidence of EID in the study region was 38.6% lower than in the control region; however, the introduction of DWTW supplies did not significantly affect the incidence of bacillary dysentery. These results indicate that the construction and use of DWTW systems with household taps is associated with decreased incidences of El Tor cholera, viral hepatitis A, and acute watery diarrhoea. Since high construction costs have led many authorities to question the value of DWTW, we carried out a cost-benefit analysis of the programme. The cost of constructing a DWTW system averaged US $36,000 at 1983 prices, or US $10.50 per capita. The combined capital and operating costs of a DWTW system were US $1.46 per capita per annum over its 20-year estimated life. The benefits derived from reductions in cost of illness and savings in time to fetch water were 2.2 times the costs at present values Capital outlays were recouped in a 3.6-year payback period and the provision of DWTW proved highly beneficial in both economic and social terms.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) National Reye syndrome surveillance--United States, 1982 and 1983. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1984 Feb 3;33(4):41–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esrey S. A., Feachem R. G., Hughes J. M. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: improving water supplies and excreta disposal facilities. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63(4):757–772. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry F. J. Environmental sanitation infection and nutritional status of infants in rural St. Lucia, West Indies. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1981;75(4):507–513. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su D. L. [Drinking water and liver cancer: an epidemiologic approach to the etiology of liver cancer in China (author's transl)]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1980 May;14(2):65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su D. Drinking water and liver cell cancer: an epidemiologic approach to the etiology of this disease in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 1979 Nov;92(11):748–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. L. [A water-borne outbreak of diarrhea]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1984 Aug;5(4):209–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. Q. [Epidemiological investigation on an outbreak of epidemic adult diarrhea in a coal mine area of Jinzhou]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 1983 Oct;4(5):281–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]