Abstract

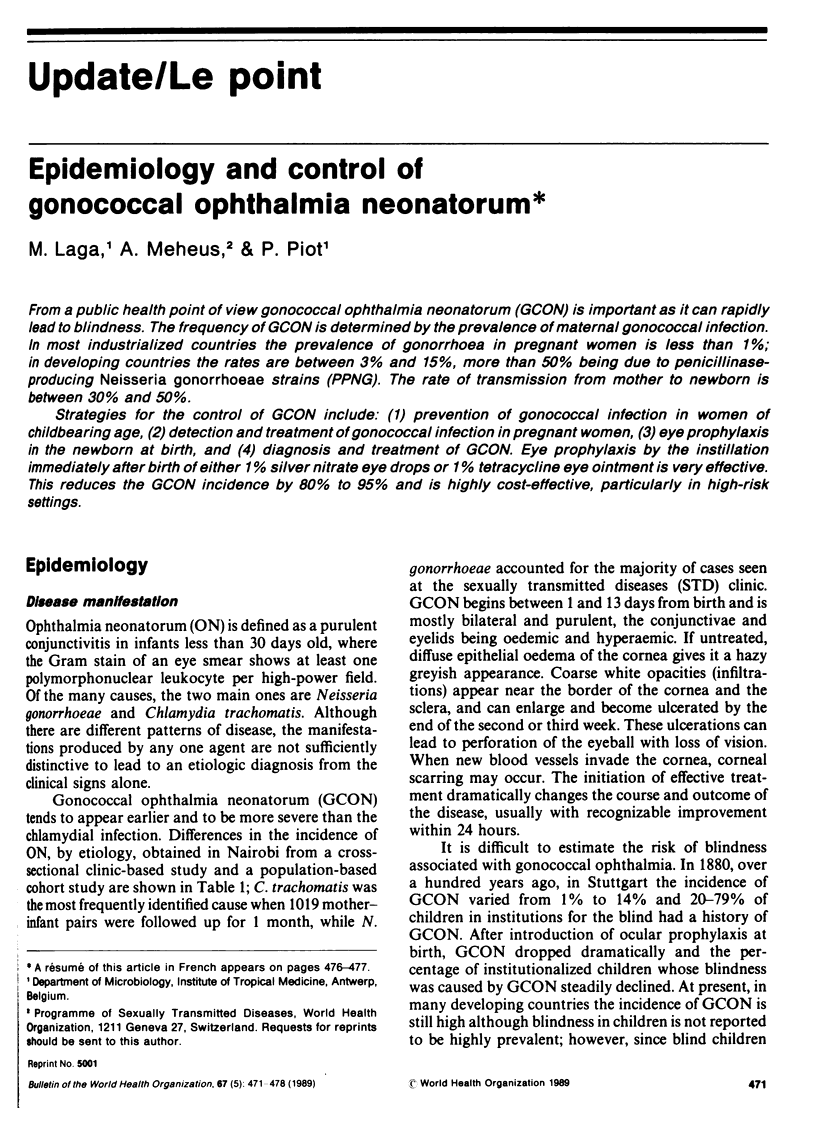

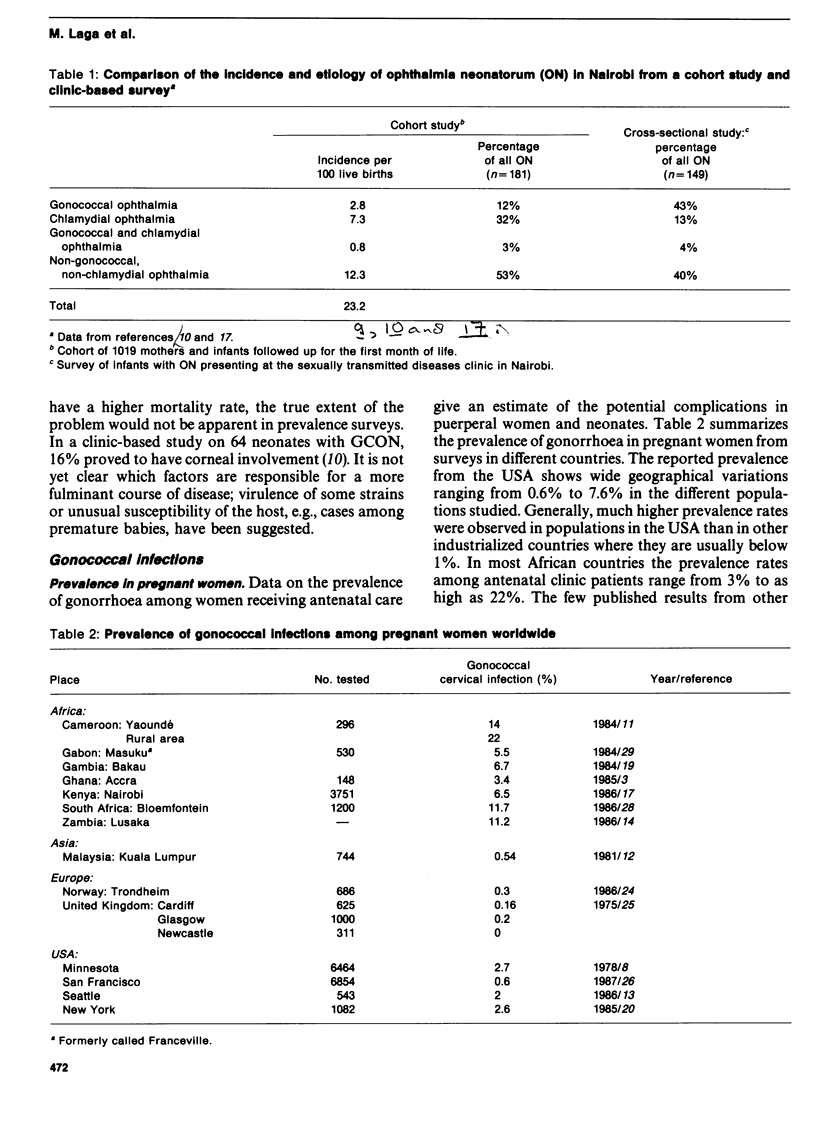

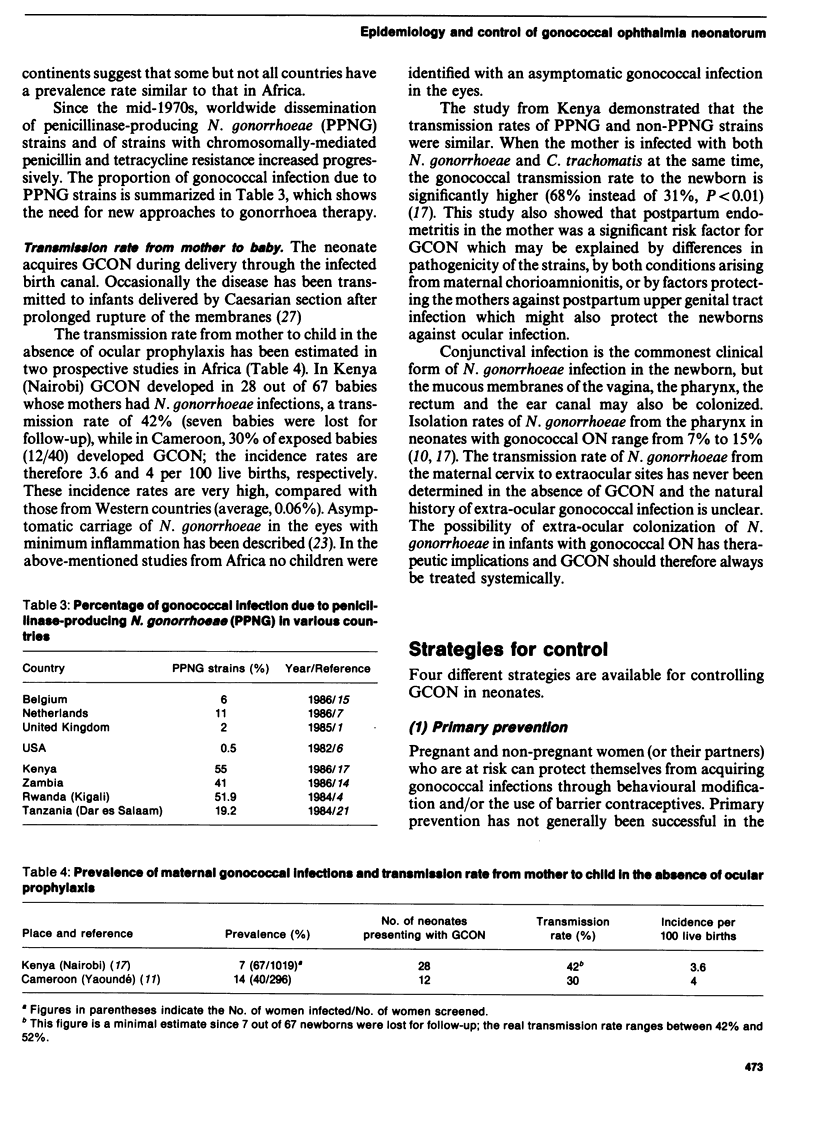

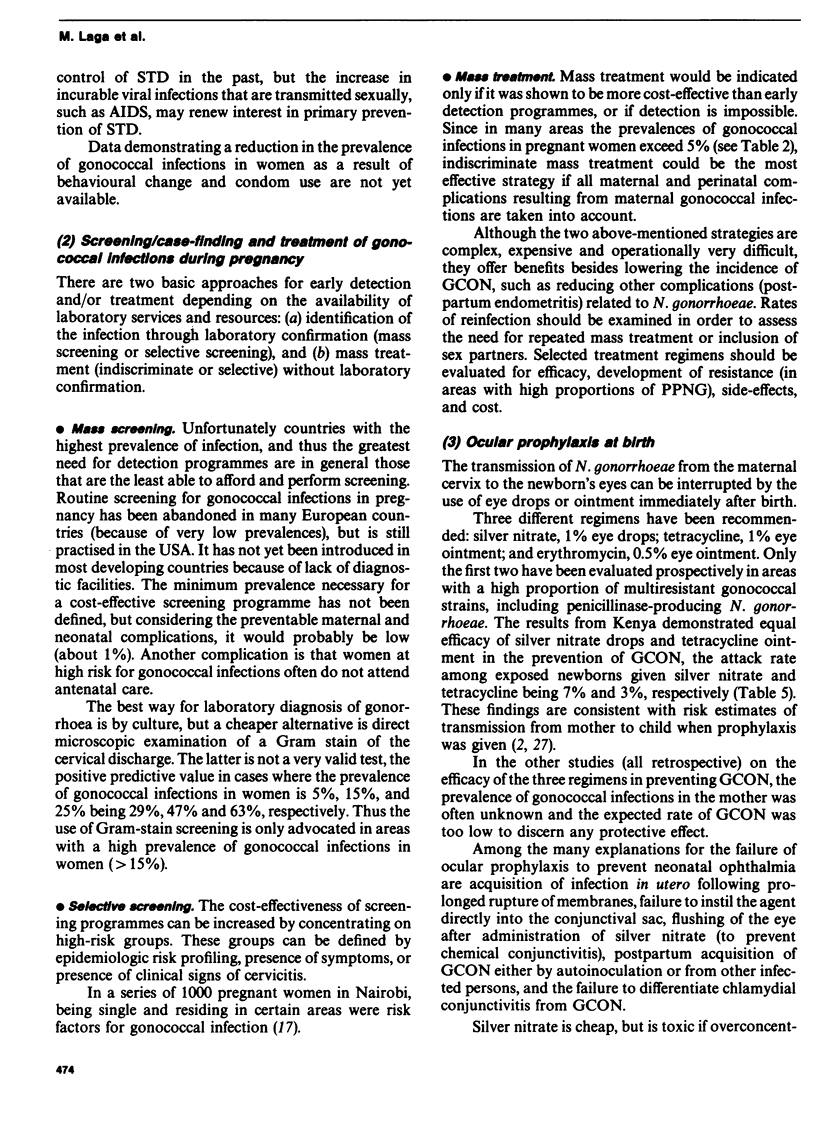

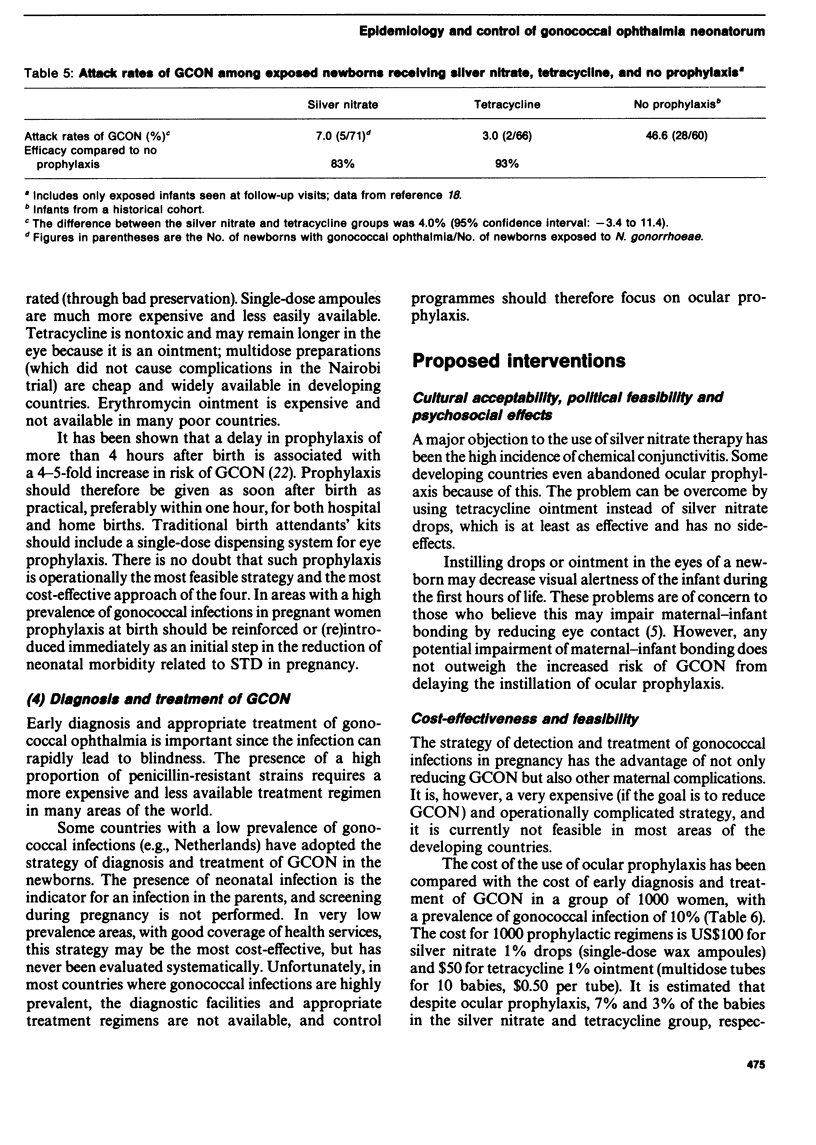

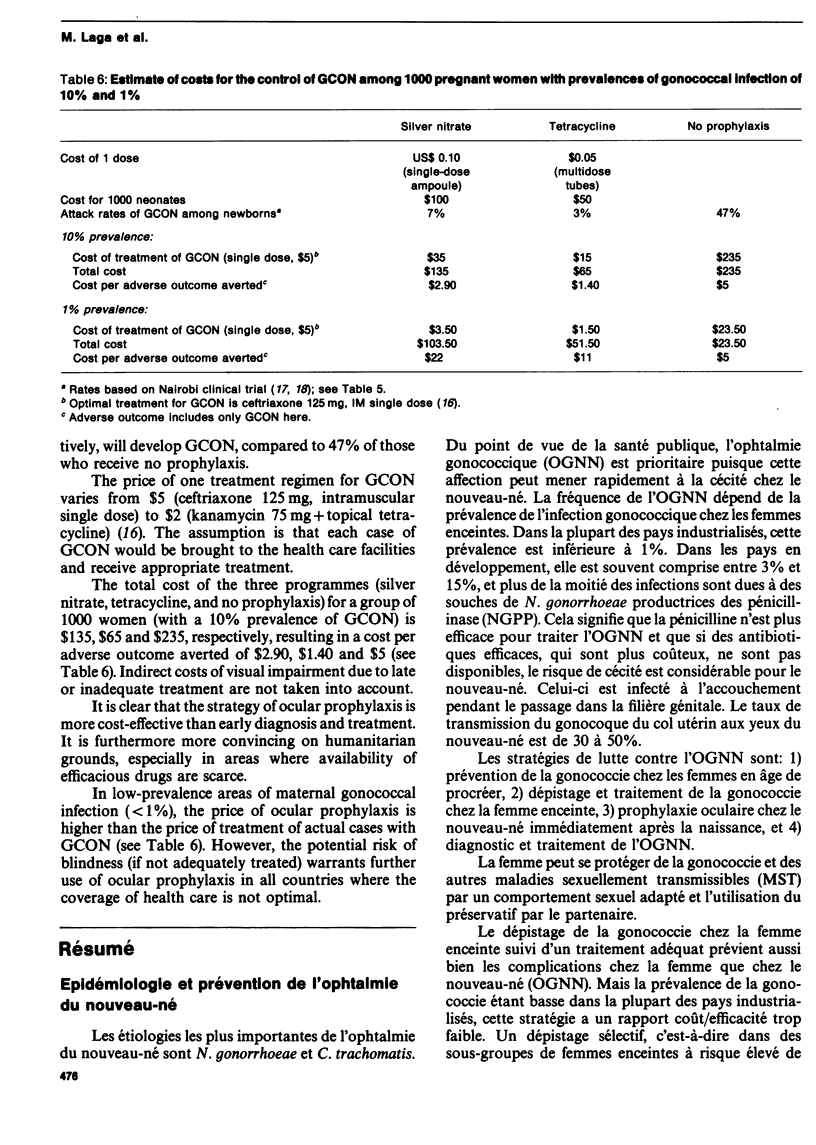

From a public health point of view gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum (GCON) is important as it can rapidly lead to blindness. The frequency of GCON is determined by the prevalence of maternal gonococcal infection. In most industrialized countries the prevalence of gonorrhoea in pregnant women is less than 1%; in developing countries the rates are between 3% and 15%, more than 50% being due to penicillinase-producing Neisseria gonorrhoeae strains (PPNG). The rate of transmission from mother to newborn is between 30% and 50%. Strategies for the control of GCON include: (1) prevention of gonococcal infection in women of childbearing age, (2) detection and treatment of gonococcal infection in pregnant women, (3) eye prophylaxis in the newborn at birth, and (4) diagnosis and treatment of GCON. Eye prophylaxis by the instillation immediately after birth of either 1% silver nitrate eye drops or 1% tetracycline eye ointment is very effective. This reduces the GCON incidence by 80% to 95% and is highly cost-effective, particularly in high-risk settings.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Armstrong J. H., Zacarias F., Rein M. F. Ophthalmia neonatorum: a chart review. Pediatrics. 1976 Jun;57(6):884–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogaerts J., Vandepitte J., Van Dyck E., Vanhoof R., Dekegel M., Piot P. In vitro antimicrobial sensitivity of Neisseria gonorrhoeae from Rwanda. Genitourin Med. 1986 Aug;62(4):217–220. doi: 10.1136/sti.62.4.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield P. M., Ende R. N., Platt B. B. Effects of silver nitrate on initial visual behavior. Am J Dis Child. 1978 Apr;132(4):426–426. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1978.02120290098023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards L. E., Barrada M. I., Hamann A. A., Hakanson E. Y. Gonorrhea in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978 Nov 15;132(6):637–641. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(78)90856-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransen L., Nsanze H., Klauss V., Van der Stuyft P., D'Costa L., Brunham R. C., Piot P. Ophthalmia neonatorum in Nairobi, Kenya: the roles of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Dis. 1986 May;153(5):862–869. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh T. H., Ngeow Y. F., Teoh S. K. Screening for gonorrhea in a prenatal clinic in Southeast Asia. Sex Transm Dis. 1981 Apr-Jun;8(2):67–69. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laga M., Naamara W., Brunham R. C., D'Costa L. J., Nsanze H., Piot P., Kunimoto D., Ndinya-Achola J. O., Slaney L., Ronald A. R. Single-dose therapy of gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum with ceftriaxone. N Engl J Med. 1986 Nov 27;315(22):1382–1385. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198611273152203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laga M., Plummer F. A., Nzanze H., Namaara W., Brunham R. C., Ndinya-Achola J. O., Maitha G., Ronald A. R., D'Costa L. J., Bhullar V. B. Epidemiology of ophthalmia neonatorum in Kenya. Lancet. 1986 Nov 15;2(8516):1145–1149. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90544-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laga M., Plummer F. A., Piot P., Datta P., Namaara W., Ndinya-Achola J. O., Nzanze H., Maitha G., Ronald A. R., Pamba H. O. Prophylaxis of gonococcal and chlamydial ophthalmia neonatorum. A comparison of silver nitrate and tetracycline. N Engl J Med. 1988 Mar 17;318(11):653–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198803173181101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabey D. C., Lloyd-Evans N. E., Conteh S., Forsey T. Sexually transmitted diseases among randomly selected attenders at an antenatal clinic in The Gambia. Br J Vener Dis. 1984 Oct;60(5):331–336. doi: 10.1136/sti.60.5.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhe L., Tafari N. Is there a critical time for prophylaxis against neonatal gonococcal ophthalmia? Genitourin Med. 1986 Oct;62(5):356–357. doi: 10.1136/sti.62.5.356-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podgore J. K., Holmes K. K. Ocular gonococcal infection with minimal or no inflammatory response. JAMA. 1981 Jul 17;246(3):242–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks R. A., Williams G. L., Boyce J. M., Fitzgerald T. C., Shelley G. Antenatal screening for candidiasis, trichomoniasis, and gonorrhoea. Br J Vener Dis. 1975 Apr;51(2):110–115. doi: 10.1136/sti.51.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet R. L., Landers D. V., Walker C., Schachter J. Chlamydia trachomatis infection and pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Apr;156(4):824–833. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T. R., Swanson R. E., Wiesner P. J. Gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Relationship of time of infection to relevant control measures. JAMA. 1974 Apr 8;228(2):186–188. doi: 10.1001/jama.228.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]