Abstract

TGF-β is an important regulator of growth and differentiation in the pancreas and has been implicated in pancreatic tumorigenesis. We have recently demonstrated that TGF-β can activate protein kinase A (PKA) in mink lung epithelial cells (Zhang L, Duan C, Binkley C, Li G, Uhler M, Logsdon C, Simeone D. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2169–2180, 2004). In this study, we sought to determine whether TGF-β activates PKA in pancreatic acinar cells, the mechanism by which PKA is activated, and PKA's role in TGF-β-mediated growth regulatory responses. TGF-β rapidly activated PKA in pancreatic acini while having no effect on intracellular cAMP levels. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated a physical interaction between a Smad3/Smad4 complex and the regulatory subunits of PKA. TGF-β also induced activation of the PKA-dependent transcription factor CREB. Both the specific PKA inhibitor H89 and PKI peptide significantly blocked TGF-β's ability to activate PKA and CREB. TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition and TGF-β-induced p21 and SnoN expression in pancreatic acinar cells were blocked by H89 and PKI peptide. This study demonstrates that this novel cross talk between TGF-β and PKA signaling pathways may play an important role in regulating TGF-β signaling in the pancreas.

Keywords: sample keywords

transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is an important cytokine involved in the regulation of growth, differentiation and apoptosis in a wide variety of cell types (29, 34, 47). TGF-β has been demonstrated to be an important inhibitor of pancreatic growth and differentiation in vitro and in vivo. In cultured pancreatic acinar cells, TGF-β inhibited basal cell growth and growth stimulated by a variety of trophic factors, including CCK, FGF, and EGF (25, 58). TGF-β has also been shown to inhibit pancreatic duct cell proliferation (2). In a whole organ culture system, TGF-β inhibited acinar cell growth but also increased the number of islet cells differentiated from ductlike structures, indicating that TGF-β has effects on pancreatic differentiation (15, 37). Furthermore, in transgenic mice expressing a dominant negative TGF-β type II receptor targeted to acinar cells, which results in resistance to TGF-β-mediated signals, the pancreas showed increased proliferation and dedifferentiation of abnormally proliferating acinar cells into a more primitive ductal phenotype (4). More importantly, disruption of the TGF-β pathway in many organs, including the pancreas, appears to be important in cancer development (30). Smad4, which is the key component of TGF-β signaling pathway, has been identified as a tumor suppressor gene in pancreatic cancer (17).

To initiate signaling, a TGF-β ligand binds to and brings together type I and type II receptor serine/threonine kinases on the cell surface. This allows the type II receptor to phosphorylate the type I receptor kinase domain, which then propagates the signal through phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 proteins. Phosphorylated Smad2 or Smad3 can form heteromeric complexes with the co-Smad, Smad4. The activated Smad complexes are translocated into the nucleus and, in conjunction with other nuclear cofactors, regulate the transcription of target genes. Over the last a few years, the TGF-β signaling pathway has been intensely investigated at both cellular and molecular levels (41). In addition to the TGF-β canonical signaling pathway mediated by Smad proteins, cross talk between TGF-β and other signaling pathways, including MAP kinases, protein kinase A (PKA), and Wnt pathways has been identified (1, 3, 8, 12, 13, 18, 24, 32, 36, 43, 49, 54–56).

PKA signaling has been shown to play a role in a wide range of physiological processes, including growth, differentiation, and extracellular matrix production (53). Since many of these cellular effects are similar to those elicited by TGF-β, we postulated that PKA may mediate some of the physiological effects of TGF-β in pancreatic acinar cells. We have recently determined that TGF-β activates PKA in the TGF-β-responsive Mv1Lu mink lung epithelial cell line via a cAMP-independent mechanism (57). Since TGF-β is an important regulatory peptide in the pancreas, we sought to investigate whether TGF-β can activate PKA and the PKA-dependent transcription factor CREB in pancreatic acinar cells and its physiological role in regulating pancreatic acinar cell function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of acinar cells.

The preparation of pancreatic acini was performed as previously described (58) via a protocol approved by the University of Michigan UCUCA Committee. Briefly, pancreatic tissue was obtained from male Swiss Webster or C57Bl6 mice and digested with collagenase (100 U/ml) and incubated at 37°C for 45 min with shaking (120 cycles/min). Acini were then mechanically dispersed by trituration of tissue through polypropylene pipettes of decreasing orifice size (3.0, 2.4, and 1.2 mm) and filtration through a 150-μm mesh nylon cloth. Acini were purified by centrifugation at 50 g for 3 min through a solution containing 4% BSA and were resuspended in enhanced media that consisted of DMEM containing 0.5% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.5 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX), and 0.1 mg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor (SBTI). The dispersed acini were aliquoted in tissue culture dishes and treated with TGF-β and various treatments for specified times. Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air at 37°C during incubation times as previously described (58).

In vitro kinase assays for PKA activity.

Isolated acinar cells were treated with TGF-β (100 pM) for indicated periods of time, washed with PBS, and harvested with cold extraction buffer containing 25 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mg/ml leupeptin, 1 mg/ml aprotinin, and 0.5 mM PMSF. Protein concentrations of the crude lysates were measured, and equal amounts of protein were added to a reaction mixture containing 40 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 100 mM biotinylated PKA peptide substrate (Kemptide, Promega, Madison, WI), 3,000 Ci/mmol [γ32P]ATP, and 0.5 mM ATP per reaction. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 5 min at 30°C and then was terminated by the addition of 2.5 M guanidine hydrochloride. Five microliters of sample were spotted onto streptavidin-coated discs, washed repeatedly, dried in an oven, and placed in scintillation vials for radioactive counting. PKA assays were also performed by use of a PepTag nonradioactive cAMP-dependent protein kinase assay kit (Promega) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of cAMP.

The levels of intracellular cAMP were measured in acinar cells after treatment with TGF-β (100 pM; 5, 15, and 30 min) or forskolin (10 mM, 15 min) by use of a Biotrak cAMP enzyme immunoassay kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The cell precipitates were centrifuged, the supernatants were drawn off, and the extracts were dried in a vacuum oven. Extracts were resuspended in assay buffer, acetylated, and assayed for cAMP following the instructions supplied by the manufacturer. Acinar cells were assayed in the absence and presence of IBMX (100 mM) 10 min prior to the addition of TGF-β or forskolin.

Trypsin activity assay.

Pancreatic acini prepared from C57Bl6 mice were preincubated in HEPES Ringer (HR) buffer supplemented with 11.1 mM glucose, Eagle's minimal essential amino acids mixture, 0.1 mg/ml SBTI, and 1 mg/ml BSA and equilibrated with 100% O2 . After 30 min preincubation, acini were resuspended in fresh HR buffer solution, distributed in 1-ml aliquots, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min with the corresponding reagents. Acini were incubated with two different concentrations of caerulein (100 pM and 100 nM, Research Plus, Bayonne, NJ), with TGF-β at 100 pM, or with 100 pM caerulein + 100 pM TGF-β to test whether TGF-β would have an effect on the activation of intracellular trypsin in isolated acini. Acini samples were collected, washed with fresh HR buffer, and resuspended in MOPS homogenization buffer for homogenization. Homogenates were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min and supernatants were recovered for trypsin assay. As described by DiMagno et al. (10), trypsin activity was assayed fluorometrically by using the substrate Boc-Glu-Ala-Arg-methylcoumaryl-7-amide in a PerkinElmer LS-55 luminescence spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Wellesley, MA) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 380 and 440 nm, respectively. Trypsin activity was expressed as nanograms per milligram protein as determined by using a standard curve for purified trypsin. Supernatant protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay.

CREB ELISA assays.

Pancreatic acini prepared from C57Bl6 mice were incubated with H89 (3 μM) and PKI peptide (10 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with TGF-β (100 pM) for 30 min. Nuclear proteins were extracted and ELISA assays were performed to measure phosphorylated CREB according to manufacturer's instructions (TransAM Kit, Active Motif).

SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Dispersed acini were treated as described in the figure legends. Whole cell lysates were prepared by incubating cells in ice-cold RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM NaF, 5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 50 mM sodium, β-glycerophosphate, 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin, and 0.5 mM PMSF). Cells were sonicated for 8 s and then placed on ice for 15 min. The lysates were then centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 min at 4°C and assayed for protein quantification by use of the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent. Equal amounts of protein were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Anti-phospho-CREB and total CREB antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and anti-p21 and anti-SnoN antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used. Images were visualized by using the ECL detection system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).

Coimmunoprecipitation experiments.

Acinar cells were treated with 100 pM TGF-β for indicated time periods. Cells were lysed by sonication for 5 s in 1 ml of cell lysis buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4 containing 0.2% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.02% sodium azide, 1 mM iodoacetamide, 1 mM PMSF, 2 μg/ml leupeptin) at 4°C. The lysates were cleared by microcentrifuging for 15 min at 16,000 g at 4°C. Antibody-conjugated beads were prepared by combining 1 μg polyclonal antibodies with 10 μl 50% protein A-Sepharose bead slurry in 0.5 ml ice-cold PBS for 1 h at 4°C in a tube rotator and then were washed two times with 1 ml lysis buffer. The antibodies used for immunoprecipitation were rabbit polyclonal anti-PKA regulatory subunits Iβ and anti-PKA catalytic subunit α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Cell lysates (500 μg) were incubated with preprepared beads and 10 μl 10% BSA overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed four times with washing buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.02% sodium azide, 0.1% Triton X-100), followed by a single wash with ice-cold PBS. Proteins were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel and, after electrophoresis, Western blotting was performed with anti-Smad2, anti-Smad3 and anti-smad4 antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

[3H]thymidine incorporation assays.

The rate of DNA synthesis in cultured pancreatic acini was measured via a [3H]thymidine incorporation assay as previously described (58). Acini were exposed to TGF-β alone or with either H89 or PKI peptide for 2 days, after which 0.1 μCi/ml of [3H]thymidine was added for an additional 12 h. Subsequently, the medium was removed and cells were precipitated with 10% TCA for 15 min on ice. The cells were then rinsed twice in ice-cold 10% TCA and dissolved in 0.1 N NaOH. Radioactivity in the dissolved cell pellet was measured by liquid scintillation counting. [3H]thymidine incorporation was expressed as the percentage of total counts per minute observed in control cells.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between groups were tested by ANOVA followed by Student's t-test. Probability values of P < 0.05 were regarded as significant. Results are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

TGF-β activates PKA in pancreatic acinar cells.

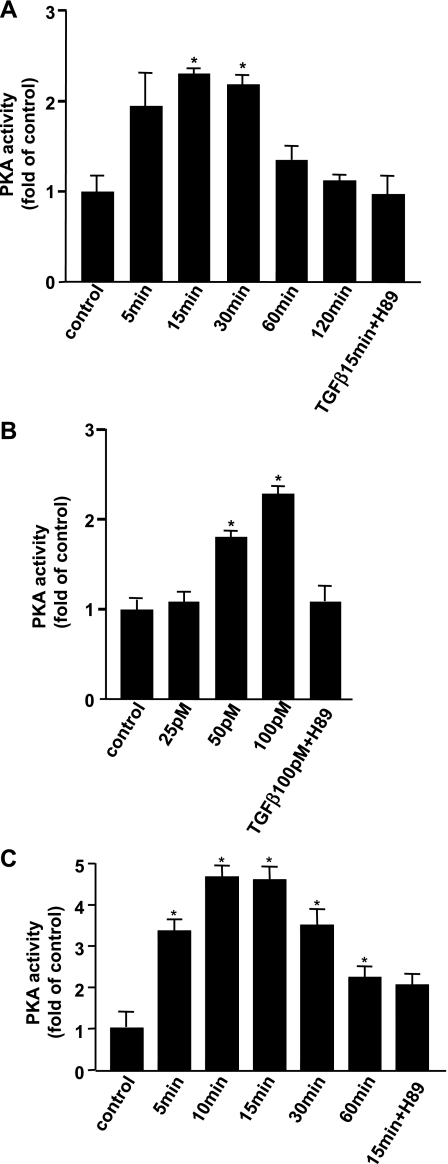

To investigate the ability of TGF-β to activate PKA, fresh isolated mouse pancreatic acinar cells were treated with TGF-β for specific times, and in vitro kinase assays were performed utilizing a biotinylated substrate for PKA (Fig. 1A). The reaction mixture was spotted onto avidin-coated paper discs to bind only the biotinylated peptide, thus increasing the specificity of the assay. It was observed that PKA activity was increased more than twofold within 15 min of administration of 100 pM TGF-β and remained elevated for 60 min. The activation of PKA by TGF-β was concentration dependent, with the greatest stimulation noted at the maximal tested concentration of 100 pM TGF-β (Fig. 1B). The level of PKA activation by TGF-β was ∼50% of that seen with forskolin, a highly potent pharmacological PKA activator (48), with a similar time course of activation of PKA noted with TGF-β and forskolin (Fig. 1C). Of note, the level of PKA activation induced by TGF-β is similar to that seen by secretagogues in both pancreatic acini and bile duct epithelial cells (28, 31). The ability of both TGF-β and forskolin to activate PKA was blocked by addition of H89 (3 μM), a specific PKA inhibitor. TGF-β's ability to activate PKA was independent of new protein synthesis, since it was not inhibited by pretreatment with the protein synthesis inhibitor cyclohexamide (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

TGF-β activates PKA in pancreatic acinar cells. Isolated pancreatic acini were treated with TGF-β (100 pM) for the indicated time periods (A) or at the indicated doses for 15 min (B). In vitro kinase assays for PKA activity were performed using a biotinylated PKA peptide substrate (Kemptide, Promega). A specific PKA inhibitor H89 (3 μM) was also used to pretreat cells for 30 min. Acinar cells were treated with 10 μM forskolin for indicated times, and PKA assays were performed (C). Results are expressed as fold increase of control from 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 vs. control).

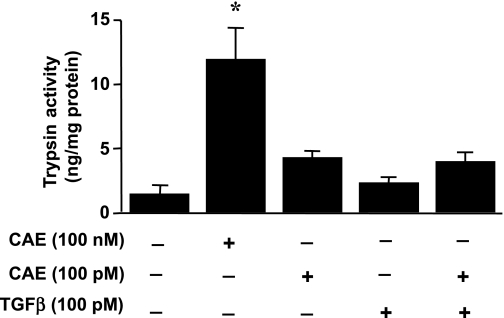

It has been previously shown that secretin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide (PACAP), ligands that increase pancreatic acinar cell cAMP levels and activation of PKA, can sensitize acinar cells to the effects of caerulein-induced zymogen activation (26). Supramaximal stimulation of acinar cells with caerulein (100 nM) is known to induce intracellular activation of trypsin and acinar cell injury in vitro and acute pancreatitis in vivo, whereas submaximal doses of caerulein (100 pM) do not induces these changes. Mouse pancreatic acinar cells were isolated and either not pretreated or pretreated with 100 pM TGF-β for 30 min and then stimulated with a supramaximal concentration of caerulein (100 nM) or with low-dose caerulein (100 pM) for 60 min and trypsin activation was measured. Supramaximal doses of caerulein produced a robust activation of trypsin in acinar cells, whereas addition of TGF-β alone had no effect on trypsin activation (Fig. 2). Treatment with low-dose caerulein did not produce a statistically significant effect on trypsin activation either alone or with pretreatment with TGF-β, demonstrating that TGF-β-induced PKA activation does not sensitize pancreatic acini to the effects of caerulein-induced zymogen activation.

Fig. 2.

TGF-β does not have sensitizing effect on caerulein (CAE)-induced trypsin activity, expressed as ng/mg protein, from isolated acini preparations incubated with caerulein at a submaximal dose (100 pM) or at supramaximal dose (100 nM), or with TGF-β at 100 pM, as indicated in methods. Control acini were incubated with the caerulein and the TGF-β vehicle (*P < 0.001 vs. untreated controls).

TGF-β activates CREB in pancreatic acinar cells.

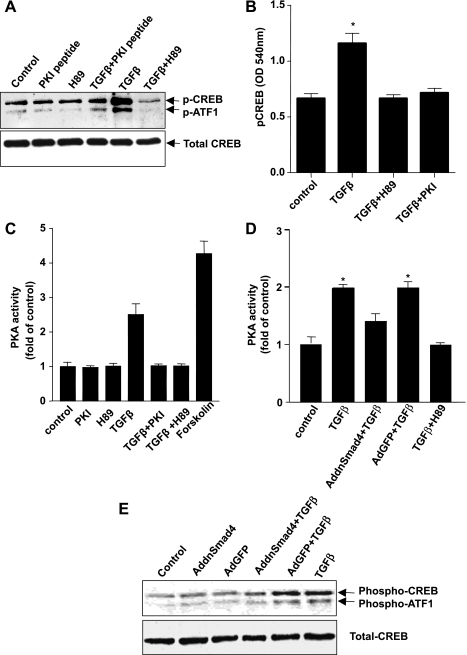

To determine the functional significance of TGF-β-induced PKA activation, we examined the ability of TGF-β to activate the transcription factor cyclic AMP-responsive element protein (CREB) in pancreatic acinar cells. CREB is a stimulus-induced transcription factor that is one of the best characterized nuclear substrates of PKA. Although CREB activation was initially characterized as mediating responses to cAMP, it has since been found to be activated by a wide range of diverse extracellular signals and protein kinases in all cells (40). CREB is phosphorylated and activated by PKA at serine-133. Enhanced CREB phosphorylation (upper bands) was observed in acinar cell lysates extracted from TGF-β-treated cells compared with control cells (Fig. 3A). Anti-phospho-CREB antibody is raised against the phosphoserine in a portion of the CREB protein that shares >95% homology with the phosphoserine site of the transcription factor ATF-1 (14); therefore, this protein may also be demonstrated on immunoblotting (lower bands). The level of phosphorylated ATF-1 after treatment with either TGF-β or forskolin was less than that of CREB. Since nuclear translocation is also a prerequisite for the function of CREB, we validated our results with Western blotting by extracting nuclear proteins from acinar cells either untreated or treated with 100 pM TGF-β and performing ELISA assays. We found an increase in nuclear phosphorylated CREB following TGF-β treatment (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

TGF-β-mediated activation of PKA and CREB is dependent on Smad4 in pancreatic acinar cells. PKA and CREB activities following TGF-β stimulation were measured in isolated mouse pancreatic acinar cells treated with PKI peptide (10 μM) or H89 (3 μM) for 30 min prior to TGF-β treatment (100 pM for 30 min). Western blot analysis of cell lysates (A), ELISA assay for phosphorylated CREB from nuclear extracts (B), and PKA activity assay (C) were performed. PKA activity and CREB activation following TGF-β stimulation were also measured in mouse pancreatic acinar cells that were infected with either AddnSmad4 virus or AdGFP control virus for 48 h. Cell lysates were then subjected to PKA activity assays and Western blot analysis (D and E). Results are representative of 4 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 vs. control).

TGF-β-induced PKA and CREB activation is blocked by PKI peptide and H89.

To further verify that TGF-β activates PKA, we investigated whether the activation of CREB could be blocked by the PKA pharmacological inhibitor H89 or a myristoylated, cell-permeable PKI peptide. The PKI peptide is a 16-amino acid sequence that contains a PKA pseudosubstrate sequence and specifically inhibits the catalytic subunits of PKA by binding the substrate binding site (16). Mouse pancreatic acinar cells were preincubated either with H89 (3 μM) or PKI peptide (10 μM) for 30 min followed by treatment of TGF-β (100 pM) for an additional 30 min. Cell lysates were prepared and subjected to PKA activity assay and immunoblot analysis of phospho-CREB. Phospho-CREB was also determined by phospho-CREB ELISA analysis of acini nuclear extracts. TGF-β-induced PKA activation and CREB phosphorylation were significantly blocked by both the specific PKA pharmacological inhibitor H89 and the PKI peptide (Fig. 3, A–C).

TGF-β-induced PKA and CREB activation is blocked by dnSmad4.

Since Smad4 is a critical component of TGF-β signaling, we evaluated whether TGF-β-induced activation of PKA was dependent on Smad4. Acinar cells were infected with an adenovirus expressing dominant negative mutant of Smad4 (AddnSmad4). dnSmad4 was generated by truncating 39 amino acids at the COOH terminal of wild-type Smad4, disrupting the ability of Smad4 to heterodimerize with other Smads (58). We chose to use adenoviral transfer because we have previously shown that primary cultures of pancreatic cells cannot be transfected by using standard techniques such as lipofectamine and require adenoviral-mediated gene transfer to achieve a high level of transfection efficiency (58). Acinar cells were infected with adenovirus at a titer of 106 pfu/ml for 16 h and then treated with TGF-β for 30 min. Cell lysates were prepared to measure expression of phosphorylated CREB and PKA activity. TGF-β's ability to activate PKA was significantly blocked by expression of AddnSmad4, whereas a control adenovirus expressing the marker green fluorescent protein (AdGFP) had no effect (Fig. 3D). This demonstrates that PKA activation by TGF-β is Smad4 dependent. dnSmad4 had no effect on the ability of forskolin to activate PKA (data not shown). To further support the role of Smad4 in TGF-β-induced activation of PKA, we also studied the role of Smad4 in the activation of CREB. Immunoblot analysis (Figs. 3E) showed that TGF-β-induced CREB activation was significantly blocked by dnSmad4. Thus CREB activation by TGF-β appears to be dependent on both Smad4 and the activation of PKA.

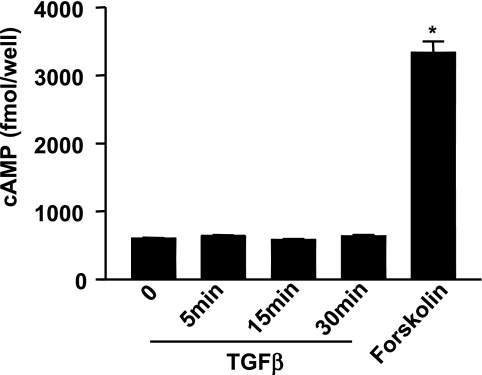

TGF-β does not increase intracellular cAMP levels in pancreatic acinar cells.

To examine whether TGF-β-induced PKA activation was due to increased levels in intracellular cAMP, acinar cells were treated with 100 pM TGF-β in the absence or presence of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX, and cAMP levels were determined. TGF-β did not increase cAMP levels when added alone (data not shown) or in the presence of IBMX (Fig. 4). In contrast, treatment with forskolin (10 μM), known to directly interact with adenylate cyclase, resulted in a significant increase in the level of intracellular cAMP. Therefore, the increase in PKA activity in TGF-β-treated pancreatic acinar cells was not dependent on changes in cAMP levels, in accord with our observations in mink lung epithelial cells (57) and what has been reported in a mesangial cell model (39).

Fig. 4.

cAMP levels are not increased with TGF-β treatment. In the presence of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX, 100 μM), cAMP levels were measured in acini after treatment with TGF-β (100 pM) or forskolin (10 μM) by using a Biotrak enzyme immunoassay assay kit. Results are from 3 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 vs. control).

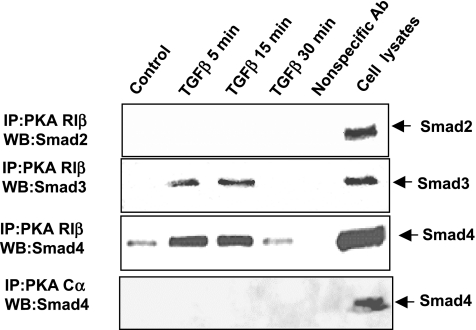

A TGF-β-induced Smad3/Smad4 complex interacts with the PKA regulatory subunits in pancreatic acinar cells.

Previously we have shown that a TGF-β-induced Smad3/Smad4 complex interacts with the PKA regulatory subunits and activates PKA in mink lung epithelial cells (28). To determine the mechanism of PKA activation by TGF-β in pancreatic acinar cells, cells were treated with 100 pM TGF-β for 5, 15, and 30 min, and coimmunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis were performed using acinar cell lysates. Cells untreated or treated with TGF-β (100 pM) were then harvested and immunoprecipitated with agarose-conjugated regulatory and catalytic subunit antibodies and subsequently blotted with anti-Smad2, anti-Smad3, or anti-Smad4 antibodies. Multiple isoforms of the regulatory (R) and catalytic (C) subunits exist (7). We specifically chose an antibody to the Cα isoform to evaluate binding to the catalytic subunit as Cα isoform has been shown to be ubiquitously expressed in mammalian tissues (51). Four R subunit isoforms have been identified and shown to have variable distribution among different tissues (7, 20, 38, 52). We chose an antibody to RIβ, which is present in pancreatic tissue, to specifically identify interaction with the Smad proteins. As shown in Fig. 5, both Smad3 and Smad4 interacted with the regulatory subunit of PKA in a TGF-β-dependent manner, whereas no interaction was observed with Smad2. No interaction between Smads and Cα subunit of PKA was detected. The time course of the observed Smad3/Smad4/PKA regulatory subunit interaction paralleled that for PKA activation after TGF-β treatment.

Fig. 5.

TGF-β induces the interaction of an activated Smad3/Smad4 complex with PKA regulatory subunits. Isolated acini were treated with 100 pM TGF-β for the indicated time periods. Cell lysate (500 μg) was used for immunoprecipitation (IP) with 1 μg of anti-PKA regulatory subunit Iβ and anti-PKA catalytic subunit α antibodies. Samples were subsequently immunoblotted with anti-Smad2, anti-Smad3 and anti-Smad4 antibodies. Cell lysates (50 μg) were run at the same time as positive controls. WB, Western blot. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments, which provided the same results.

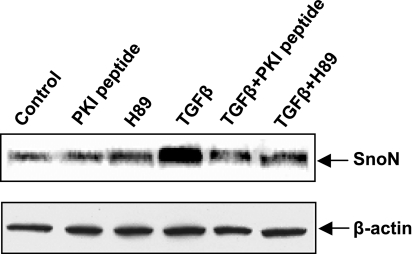

PKA mediates TGF-β-induced SnoN expression.

It has been reported that SnoN, a corepressor, is ubiquitously expressed in virtually all adult and embryonic tissues but at low levels (33, 35). Expression of SnoN is tightly controlled by TGF-β at levels of both protein stability and transcriptional activation (46). To investigate whether TGF-β was able to induce SnoN expression in mouse acinar cells and to determine whether PKA was involved in this process, mouse acinar cells were incubated either with H89 (3 μM) or PKI peptide (10 μM) for 30 min and then with TGF-β (100 pM) for further 3 h. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with SnoN antibody. As shown in Fig. 6, TGF-β induced a significantly increased SnoN expression with compared with control. Interestingly, both H89 and PKI peptide could significantly block this effect.

Fig. 6.

TGF-β-induced SnoN expression is mediated by the activation of PKA. Mouse acinar cells were preincubated either with PKI peptide (10 μM) or H89 (3 μM) for 30 min and TGF-β (100 pM) for 3 h. The cell lysates were examined for SnoN expression by Western blotting analysis. The membrane was also probed with β-actin antibody for loading control.

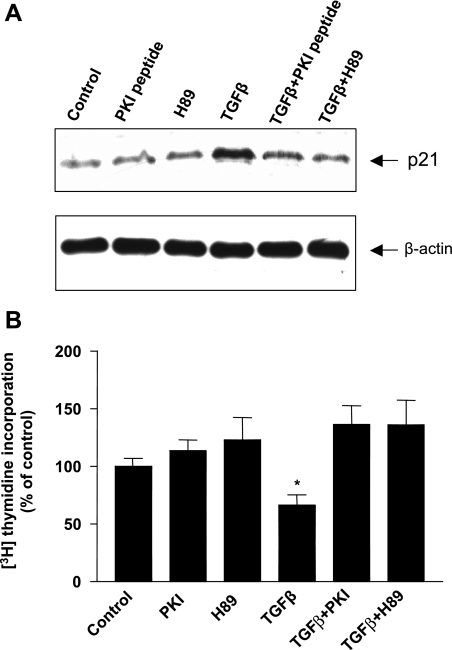

TGF-β-induced p21 expression and growth inhibition in pancreatic acinar cells is mediated by PKA.

The role of PKA in TGF-β signaling in the pancreas has not been previously studied. In many cell types, including pancreatic cells (58), TGF-β has been shown to inhibit cell growth by increasing expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21, which in turn inhibits the enzymatic activities of cyclin D-CDK4/6 and cyclin E-CDK2 complexes, leading to cell cycle arrest at the late phase of G1 (23). We have previously demonstrated that adenoviral-mediated gene transfer of dnSmad4 blocks TGF-β-induced growth inhibition in pancreatic acinar cells (58). To further explore the functional significance of PKA activation by TGF-β in pancreatic acinar cells, we examined the role of PKA in TGF-β's ability to regulate expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21. TGF-β induced a significant increase in p21 expression in acinar cells, and this inhibition was blocked by treatment with the PKA inhibitor H89 (3 μM) or PKI peptide (10 μM) (Fig. 7A). Next, we examined the role of PKA in TGF-β's ability to inhibit proliferation of pancreatic acinar cells grown in short-term cultures. Addition of TGF-β (100 pM) to short-term cultures of pancreatic acinar cells for 36 h inhibited pancreatic acinar cell growth by 60%, whereas treatment with either H89 or PKI peptide completely blocked TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition (Fig. 7B). Addition of H89 or PKI peptide alone had no effect on p21 expression or cell growth compared with controls. Together, these results suggest that TGF-β-mediated PKA activation by a Smad3/Smad4 complex is critical for activation of the transcription factor CREB. TGF-β-mediated PKA activation is also responsible for inducing p21 and SnoN expression and inhibiting pancreatic acinar cell growth.

Fig. 7.

TGF-β-induced p21 expression and growth inhibition is mediated by the activation of PKA. TGF-β-induced p21 expression can be blocked by PKI peptide and H89 (A). Acinar cells were pretreated with PKI peptide (10 μM) or H89 (3 μM) for 30 min. TGF-β (100 pM) was added for 16 h, and 30 μg of protein was used to perform Western blotting (top). The same membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-β-actin antibody to demonstrate equal loading (bottom). Experiments were repeated 3 times with essentially the same results. TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition was determined by [3H]thymidine incorporation assays (B). Acinar cells were treated with TGF-β (100 pM) for 60 h. Some cells were also treated with 10 μM PKI peptide or 3 μM H89. Results are expressed as a percentage of control from 4 separate experiments (*P < 0.01 vs. control).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate a novel cross talk mechanism by which TGF-β activates PKA in pancreatic acinar cells without increasing intracellular cAMP levels and by inducing an interaction between an activated Smad3/Smad4 complex and PKA regulatory subunits. We show that the ability of TGF-β to induce CREB activation and p21 and SnoN expression, and to inhibit growth in pancreatic acinar cells, is mediated through this novel interaction with PKA. This previously unrecognized cross talk between the important TGF-β/Smad and PKA/CREB pathways appears to play a central role in pancreatic growth control.

Interestingly, we did not observe that PKA activation by TGF-β played a role in sensitizing pancreatic acinar cells to caerulein-induced trypsin activation as has been reported by other ligands that increase cAMP and PKA in pancreatic acinar cells, such as secretin, VIP, and PACAP. The reason that PKA activation by TGF-β does not produce this sensitizing effect is not clear. It is possible that differences in the ability of TGF-β and other ligands to sensitize pancreatic acini may be due to the fact that TGF-β does not activate cAMP in the process of activating PKA, whereas the other ligands do increase intracellular levels of cAMP in the process of activating PKA. Alternatively, it has been shown that PKA may be compartmentalized in different subcellular locations through interactions with A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) (11). If TGF-β-activated PKA and PKA activated by the other ligands are compartmentalized in different subcellular locations because of interactions with different AKAPs, that may account for the differences observed in sensitization of acini to low-dose caerulein.

The role of PKA in mediating TGF-β-induced physiological responses is just beginning to be explored. An increasing number of reports in the literature have demonstrated a central role for PKA in mediating several important types of TGF-β-induced physiological responses among a variety of different cell types. For example, Sharma and colleagues (39) demonstrated that TGF-β-induced phosphorylation of the type I 1,4,5-inositol trisphosphate receptor in mesangial cells is mediated by PKA. Also, inhibition of PKA has been found to attenuate TGF-β-induced stimulation of CREB phosphorylation and laminin and fibronectin gene expression in mesangial cells (44). In vascular endothelial cells derived from bone, the ability of TGF-β to induce the expression of the receptor activator of NF-κB ligand is dependent on PKA (19). Furthermore, Kunzemann et al. found an additive effect of TGF-β and PKA in mediating CD4+ T cell suppression (22). Although a clear association between PKA and TGF-β signaling has been demonstrated in the above studies, none have delineated the specific molecular mechanisms by which PKA interacted with TGF-β signaling.

We have recently reported in a mink lung epithelial cell line (Mv1Lu) that TGF-β activates PKA independent of increased cAMP via interaction of an activated Smad complex and with the regulatory subunit of the PKA holoenzyme, with subsequent release of the active catalytic subunit from the PKA holoenzyme (57). However, it was unknown whether this previously unrecognized interaction between the TGF-β and PKA signaling pathways occurred in other cell systems and whether it was physiologically relevant to cell function. TGF-β has been shown to play a pivotal role in pancreatic development and differentiation, in acute and chronic inflammation in the pancreas, and in pancreatic cancer. Since the role of TGF-β in cellular responses has been previously found to highly dependent on cell type and cellular context, we sought to determine whether PKA activation by TGF-β was necessary in mediating TGF-β responses in the pancreas. In this study, we demonstrate that PKA activation by TGF-β played a critical role in mediating several important TGF-β responses in pancreatic acinar cells.

Alterations in the PKA signaling pathway have been linked to dysregulation in the cell cycle as well as neoplastic development in a number of different model systems. In normal cells, both cAMP and PKA levels in populations of synchronized cells oscillate during the cell cycle, with a surge during the G1 phase (5). CHO cells overexpressing the PKA regulatory subunit RIα were able to grow indefinitely in the absence of serum or growth factors, whereas parental cells or those overexpressing RIIβ or Cα were unable to grow in serum- free conditions (50). Several recent studies have demonstrated the role of PKA in tumorigenesis. Inherited mutations in the gene encoding RIα causes the multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome known as Carney complex (21). In addition, a link has been reported between the expression of PKA signaling with the natural history of breast cancer (45). In a separate set of studies, Cho-Chung and colleagues (6) examined the role of an antisense oligonucleotide targeting the RIα subunit of PKA in a variety of cancer cell lines in vitro and tumors in vivo. By downregulating RIα and thus increasing PKA activity in cancer cells, they demonstrated cancer cell growth arrest, apoptosis, and changes in cancer cell morphology. Moreover, genetic mutants of the RIα subunit, but not the C subunit, exhibit resistance to the anticancer agent cisplatin (9). Thus understanding the role of PKA in TGF-β signaling in pancreatic cells may have important clinical implication in understanding the development and progression of pancreatic cancer.

Escape of epithelial cells from TGF-β-mediated growth regulation is a hallmark of many cancers, including pancreatic cancers. It has been shown that Smad4 is a tumor suppressor gene and has high frequency of deletion or mutation in pancreatic cancer (17). We have previously shown that the ability of TGF-β to inhibit growth in normal pancreatic cells is dependent on Smad4 (58), and it is likely that the loss of TGF-β growth regulatory mechanisms in the pancreas is due, at least in part, to mutation or deletion of Smad4 in pancreatic cancer. We have recently shown that TGF-β cannot activate PKA in Smad4-null cells (57). In addition, TGF-β does not activate PKA in the Panc-1 and MiaPaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cell lines, which are not responsive to the growth-inhibitory effects of TGF-β (data not shown). Interestingly, these two pancreatic cancer cell lines do not have defined genetic defects in Smads or abnormal TGF-β receptors (42). The role of alterations in PKA signaling components has not yet been examined in these cell lines.

In our study, we demonstrate for the first time that PKA activation by TGF-β is required for TGF-β-induced SnoN upregulation in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. SnoN (ski-related novel gene N) belongs to ski family of nuclear proteins. Ski and SnoN have been shown to be important negative regulators of signaling elicited by TGF-β via their interactions with Smad proteins (27). Recent studies have demonstrated that the TGF-β regulated Smad2 and Smad3 as well as their common partner protein Smad4 interact with and recruit SnoN to the Smad binding element within the promoters of TGF-β-responsive genes. Overexpression of SnoN acts as a transcriptional repressor of TGF-β-induced target genes (27). As a result, overexpression of SnoN is able to render cells resistant to TGF-β-induced growth inhibition. This ability of SnoN to inactivate the tumor suppressor function of Smads may be partially responsible for the transforming ability of SnoN. The role of TGF-β-mediated activation of PKA and SnoN in pancreatic tumorigenesis remains to be explored.

In summary, we have shown that TGF-β activated PKA without increasing intracellular cAMP levels in pancreatic acinar cells. The mechanism of PKA activation by TGF-β was due to a direct interaction between an activated Smad3/Smad4 complex and PKA regulatory subunit. This interaction was specific and ligand dependent. We have also demonstrated that PKA activation by TGF-β was important in mediating several physiological responses elicited by TGF-β, including CREB activation, p21 and SnoN induction, and growth inhibition in pancreatic acinar cells. This study has provided new insight in understanding of the molecular cross talk between PKA and TGF-β signaling pathways in pancreatic acinar cells and has significant implications for understanding the role of TGF-β in pancreatic diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01 DK-061507 (D. M. Simeone).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bakin AV, Tomlinson AK, Bhowmick NA, Moses HL, Arteaga CL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase function is required for transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cell migration. J Biol Chem 275: 36803–36810, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya E, Panchal A, Wilkins TJ, de Ondarza J, Hootman SR. Insulin, transforming growth factors, and substrates modulate growth of guinea pig pancreatic duct cells in vitro. Gastroenterology 109: 944–952, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhowmick NA, Zent R, Ghiassi M, McDonnell M, Moses HL. Integrin beta 1 signaling is necessary for transforming growth factor-beta activation of p38MAPK and epithelial plasticity. J Biol Chem 276: 46707–46713, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bottinger EP, Jakubczak JL, Roberts IS, Mumy M, Hemmati P, Bagnall K, Merlino G, Wakefield LM. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant TGF-beta type II receptor in transgenic mice reveals essential roles for TGF-beta in regulation of growth and differentiation in the exocrine pancreas. EMBO J 16: 2621–2633, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyton AL, Whitfield JF. The role of cAMP in cell proliferation: a critical assessment of the evidence. In: Advances in Cyclic Nucleotide Research (vol. 15), edited by Greengard P and Robison GA. New York: Raven, 1983, p. 193–294.

- 6.Cho YS, Cho-Chung YS. Antisense protein kinase A RIalpha synergistically with hydroxycamptothecin to inhibit growth and induce apoptosis in human cancer cells: molecular basis for combinatorial therapy. Clin Cancer Res 9: 1171–1178, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clegg CH, Cadd GG, McKnight GS. Genetic characterization of a brain-specific form of the type I regulatory subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 3703–3707, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colwell AS, Krummel TM, Longaker MT, Lorenz HP. Wnt-4 expression is increased in fibroblasts after TGF-beta1 stimulation and during fetal and postnatal wound repair. Plast Reconstr Surg 117: 2297–2301, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cvijic ME, Yang WL, Chin KV. Cisplatin resistance in cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase mutants. Pharmacol Ther 78: 115–128, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiMagno MJ, Williams JA, Hao Y, Ernst SA, Owyang C. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is protective in the initiation of caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G80–G87, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards AS, Scott JD. A-kinase anchoring proteins: protein kinase A and beyond. Curr Opin Cell Biol 12: 217–221, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engel ME, McDonnell MA, Law BK, Moses HL. Interdependent SMAD and JNK signaling in transforming growth factor-beta-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem 274: 37413–37420, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giannouli CC, Kletsas D. TGF-β regulates differentially the proliferation of fetal and adult human skin fibroblasts via the activation of PKA and the autocrine action of FGF-2. Cell Signal 18: 1417–1429, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ginty DD, Kornhauser JM, Thompson MA, Bading H, Mayo KE, Takahashi JS, Greenberg ME. Regulation of CREB phosphorylation in the suprachiasmatic nucleus by light and a circadian clock. Science 260: 238–241, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gittes GK, Galante PE, Hanahan D, Rutter WJ, Debas HT. Lineage-specific morphogenesis in the developing pancreas: role of mesenchymal factors. Development 122: 439–447, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glass DB, Cheng HC, Kemp BE, Walsh DA. Differential and common recognition of the catalytic sites of the cGMP-dependent and cAMP-dependent protein kinases by inhibitory peptides derived from the heat stable inhibitor protein. J Biol Chem 261: 12166–12171, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn SA, Schutte M, Hoque AT, Moskaluk CA, da Costa LT, Rozenblum E, Weinstein CL, Fischer A, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, Kern SE. DPC4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at human chromosome 18q21.1. Science 271: 350–353, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartsough MT, Mulder KM. Transforming growth factor beta activation of p44mapk in proliferating cultures of epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 270: 7117–7124, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishida A, Fujita N, Kitazawa R, Tsuruo T. Transforming growth factor-beta induces expression of receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand in vascular endothelial cells derived from bone. J Biol Chem 277: 26217–26224, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jahnsen T, Hedin L, Kidd VJ, Beattie WG, Lohmann SM, Walter U, Durica J, Schultz TZ, Schiltz E, Browner M, Lawrence CB, Goldman D, Ratoosh SL, Richards JS. Molecular cloning, cDNA structure, and regulation of the regulatory subunit of type II cAMP-dependent protein kinase from rat ovarian granulosa cells. J Biol Chem 261: 12352–12361, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirschner LS, Carney JA, Pack SD, Taymans SE, Giatzakis C, Cho YS, Cho-Chung YS, Stratakis CA. Mutations of the gene encoding the protein kinase A type Ia regulatory subunit in patients with Carney complex. Nat Genet 26: 89–92, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunzmann S, Mantel PY, Wohlfahrt JG, Akdis M, Blaser K, Schmidt-Weber CB. Histamine enhances TGF-beta1-mediated suppression of Th2 responses. FASEB J 17: 1089–1095, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laiho M, DeCaprio JA, Ludlow JW, Livingston DM, Massague J. Growth inhibition by TGF-beta linked to suppression of retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Cell 62: 175–185, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Letamendia A, Labbe E, Attisano L. Transcriptional regulation by Smads: crosstalk between the TGF-beta and Wnt pathways. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83-A, Suppl 1: S31–S39, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logsdon CD, Keyes L, Beauchamp RD. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β1) inhibits pancreatic acinar cell growth. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 262: G364–G368, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Z, Kolodecik TR, Karne S, Nyce M, Gorelick F. Effect of ligands that increase cAMP on caerulein-induced zymogen activation in pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G822–G828, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luo K Ski and SnoN: negative regulators of TGF-β signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev 14: 65–70, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marino CR, Leach SD, Schaefer JF, Miller LJ, Gorelick FS. Characterization of cAMP-dependent protein kinase activation by CCK in the rat pancreas. FEBS Lett 316: 48–52, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massague J TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem 67: 753–791, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell 103: 295–309, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGill JM, Basavappa S, Gettys TW, Fitz JG. Secretin activates Cl− channels in bile duct epithelial cells through a cAMP-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 266: G731–G736, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Millar SE Smad7: licensed to kill beta-catenin. Dev Cell 11: 274–276, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Normura N, Saamoto S, Ishii S, Date T, Matsui M, Ishizaki R. Isolation of human cDNA clones of ski and the ski-related gene, sno. Nucleic Acids Res 17: 5489–5500, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patterson GI, Padgett RW. TGF beta-related pathways. Role of Caenorhabditis elegans development. Trends Genet 16: 27–33, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearson-White S, Crittenden R. Proto-oncogene Sno expression, alternative isoforms and immediate early serum response. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 2930–2937, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rousse S, Lallemand F, Montarras D, Pinset C, Mazars A, Prunier C, Atfi A, Dubois C. Transforming growth factor-beta inhibition of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 synthesis in skeletal muscle cells involves a c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 276: 46961–46967, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanvito F, Herrera PL, Montesano R, Orci L, Vassalli JD. TGF-β1 influences the relative development of the exocrine and endocrine pancreas in vitro. Development 120: 3451–3462, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott JD, Glaccum MB, Zoller MJ, Uhler MD, Helfman DM, McKnight GS, Krebs EG. The molecular cloning of a type II regulatory subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase from rat skeletal muscle and mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84: 5192–5196, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma K, Wang L, Zhu Y, Bokkala S, Joseph SK. Transforming growth factor-beta1 inhibits type I inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor expression and enhances its phosphorylation in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 272: 14617–14623, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. CREB: a stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu Rev Biochem 68: 821–861, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 113: 685–700, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simeone DM, Pham T, Logsdon CD. Disruption of TGF-β signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancer cells. Ann Surg 232: 73–80, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simeone DM, Zhang L, Graziano K, Nicke B, Pham T, Schaefer C, Logsdon CD. Smad4 mediates activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by TGF-beta in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C311–C319, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh LP, Green K, Alexander M, Bassly S, Crook ED. Hexosamines and TGF-β1 use similar signaling pathways to mediate matrix protein synthesis in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F409–F416, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srivastava RK, Srivastava AR, Seth P, Agrwawal S, Cho-Chung YS. Growth arrest and induction of apoptosis in breast cancer cells by antisense depletion of protein kinase A-RI alpha subunit: p53-independent mechanism of action. Mol Cell Biochem 195: 25–36, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stroschein SL, Wang W, Zhou S, Zhou Q, Luo K. Negative feedback regulation of TGF-beta signaling by the SnoN oncoprotein. Science 286: 771–774, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ten Dijke PT, Goumans MJ, Itoh F, Itoh S. Regulation of cell proliferation by Smad proteins. J Cell Physiol 191: 1–16, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tesmer JJ, Sprang SR. The structure, catalytic mechanism and regulation of adenylyl cyclase. Curr Opin Struct Biol 8: 713–719, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tobimatsu T, Kaji H, Sowa H, Naito J, Canaff L, Hendy GN, Sugimoto T, Chihara K. Parathyroid hormone increases β-catenin levels through Smad3 in mouse osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology 147: 2583–2590, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tortora G, Cho-Chung YS. Type II regulatory subunit of protein kinase restores cAMP-dependent transcription in a cAMP-unresponsive cell line. J Biol Chem 265: 18067–18070, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uhler MD, Chrivia JC, McKnight GS. Evidence for a second isoform of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 261: 15360–15363, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ventra C, Porcellini A, Feliciello A, Gallo A, Paolillo M, Mele E, Avvedimento VE, Schettini G. The differential response of protein kinase A to cAMP in discrete brain areas correlates with the abundance of regulatory subunit II. J Neurochem 66: 1752–1761, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walsh DA, Van Patten SM. Multiple pathway signal transduction by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. FASEB J 8: 1227–1236, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang FM, Hu T, Tan H, Zhou XD. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase affects transforming growth factor-β/Smad signaling in human dental pulp cells. Mol Cell Biochem 291: 49–54, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang L, Zhu Y, Sharma K. Transforming growth factor-beta1 stimulates protein kinase A in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 273: 8522–8527, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zavadil J, Bitzer M, Liang D, Yang YC, Massimi A, Kneitz S, Piek E, Bottinger EP. Genetic programs of epithelial cell plasticity directed by transforming growth factor-beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 6686–6691, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang L, Duan C, Binkley C, Li G, Uhler M, Logsdon C, Simeone D. A TGF-beta induced Smad3/Smad4 complex directly activates protein kinase A. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2169–2180, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L, Graziano K, Pham T, Logsdon CD, Simeone DM. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of dominant-negative Smad4 blocks TGF-beta signaling in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G1247–G1253, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]