Abstract

Heterologous expression systems have increased the feasibility of developing selective ligands to target nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) subtypes. However, the α6 subunit, a component in nAChRs that mediates some of the reinforcing effects of nicotine, is not easily expressed in systems such as the Xenopus oocyte. Certain aspects of α6-containing receptor pharmacology have been studied by using chimeric subunits containing the α6 ligand-binding domain. However, these chimeras would not be sensitive to an α6-selective channel blocker; therefore we developed an α6 chimera (α4/6) that has the transmembrane and intracellular domains of α6 and the extracellular domain of α4 We examined the pharmacological properties of α4/6-containing receptors and other important nAChR subtypes, including α7, α4β2, α4β4, α3β4, α3β2,and α3β2β3, as well as receptors containing α6/3 and α6/4 chimeras. Our data show that the absence or presence of the β4 subunit is an important factor for sensitivity to the ganglionic blocker mecamylamine, and that dihydro-β-erythroidine is most effective on subtypes containing the α4 subunit extracellular domain. Receptors containing the α6/4 subunit are sensitive to α-conotoxin PIA, while receptors containing the reciprocal α4/6 chimera are insensitive. In experiments with novel antagonists of nicotine-evoked dopamine release, the α4/6 chimera indicated that structural rigidity was a key element of compounds that could result in selectivity for noncompetitive inhibition of α6-containing receptors. Our data extend the information available on prototypical nAChR antagonists, and establish the α4/6 chimera as a useful new tool for screening drugs as selective nAChR antagonists.

Introduction

There are three major classes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) in mammals: muscle-type receptors, heteromeric neuronal-type receptors, and homomeric neuronal receptors. All nAChRs are believed to form pentameric complexes. Important elements of the agonist binding sites are part of the alpha subunits, but the binding sites are located at the interface between alpha and non-alpha subunits, and the non-alpha subunits contribute importantly to the pharmacological properties of the receptors (Luetje and Patrick, 1991), including β1 in regard to the relative insensitivity of muscle type receptors to ganglionic blockers (Webster et al., 1999).

Eight alpha subunit genes have been cloned from mammalian neuronal tissue (α2, α3, α4, α5, α6, α7, α8, α9, and α10), as well as three non-alpha subunits (β2, β3, and β4). The simplest of the neuronal nAChR to study in the oocyte expression system is the homomeric subtype, which in mammalian brain is composed of only α7 subunits (Gotti et al., 2006). The heteromeric neuronal type receptors form as various combinations of alpha and beta subunits, always containing at least one type of alpha (either α2, α3, α4, or α6) and at least one type of beta subunit. In the continued presence of agonist, heteromeric receptors convert to a desensitized state that binds nicotine and other agonists with high affinity; these receptors were first identified in radioligand binding studies with rat brain slices (Clarke et al., 1985).

Although there are many possible combinations of neuronal alpha and beta subunits, it has been shown that the majority of the high affinity nicotine binding sites in the brain contain combinations of just the α4 and β2 subunits. Co-injections of RNA for these two subunits into Xenopus oocytes readily result in the expression of receptors with pharmacological properties consistent with those of the brain's high affinity receptors (Nelson et al., 2003). Likewise, co-expression of α3 and β4 subunits, strongly expressed in the peripheral nervous system, yields receptors used to model ganglionic receptors. All pairwise combinations of α2, α3, or α4 with either β2 or β4 are easily characterized in the oocyte expression systems, and those results can be extended to model more complex subunit combinations through the analysis of the effects of systematic addition of other subunits (Gerzanich et al., 1998; Papke et al., 2007).

The first practical targeting of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) for a therapeutic indication came with the development of ganglionic blockers, such as hexamethonium and mecamylamine, for the treatment of hypertension (Stone et al., 1956). While the use of ganglionic blockers for the treatment of hypertension has been eclipsed by the subsequent development of more effective antihypertensive agents with better side-effect profiles, there is a renewed interest in antagonists that may inhibit nAChRs in brain (Dwoskin et al., 2004; Rose et al., 1994a; Rose et al., 1994b). Of necessity, for human studies this renewed interest has focused on the classical, and largely nonselective blocker, mecamylamine, since is it the only CNS active nAChR antagonist approved for use in humans. Mecamylamine has been shown to have usefulness as an adjunct therapy in the treatment of Tourette's syndrome (Sanberg et al., 1998) and, in combination with nicotine replacement therapy, to improve clinical effectiveness in smoking cessation therapy (Rose et al., 1994b).

As with any course of therapeutic development, the diversity of receptor subtypes associated with different indications has created a need for the development of subtype-selective drugs. Unfortunately, nAChRs in brain show diversity and subtlety of function that, arguably, is unsurpassed by any other receptor system in the CNS. Several subtype-selective agonists and partial agonists are now in clinical trails for various indications (Olincy et al., 2006; Potts and Garwood, 2007; Wilens et al., 2006). However, the development of subtype-selective antagonists has proven to be a more daunting challenge. One reason for this is that some complex subunit combinations that may exist in vivo are not easily recreated in artificial expression systems. This is particularly true for receptor subtypes containing the α6 subunit (Dowell et al., 2003; Kuryatov et al., 2000). Nonetheless, because α6-containing receptors are likely involved in nicotine dependence (Azam et al., 2007; Azam and McIntosh, 2006), they have been proposed to be a potentially useful target for therapies using nicotinic receptor antagonists (Dwoskin et al., 2004; Zoli et al., 2002). We have extended the characterization of the commonly used nAChR antagonists mecamylamine and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE), and herein report a new chimera that may be useful for identifying α6-selective noncompetitive antagonists. We utilize that chimera to test a series of bis-quaternary ammonium compounds, identifying structural rigidity of the analogs as a potentially important feature for selective inhibition of receptors containing the α6 intracellular and transmembrane domains.

Methods

Cloning of Chimeric subunits

Rat neuronal nAChR α4 and α6 clones were obtained from Dr. Jim Boulter (UCLA, Los Angeles, CA), and the rat α6/3 chimera has been previously characterized (Dowell et al., 2003; Papke et al., 2005). All three clones were subcloned into the pSGEM vector, obtained from Dr. Michael Hollmann (Ruhr University, Bochum, Germany), which contains Xenopus beta-globin untranslated regions to aid Xenopus oocyte expression. The α4 subunit was subcloned from pSP64 to pSGEM via Hind III. The α6 subunit was first mutated to make a silent change; an EcoR I restriction site which was within the open reading frame was removed in order to use EcoR I for the subcloning from pBS(SK-) to pSGEM. The α6/3 chimera was digested from pT7TS with Bgl II and BstE II to subclone into pSGEM digested with BamH I and BstE II.

The conserved amino acids isoleucine-arginine-arginine, located just before the first transmembrane domain (Table 3), are suitable for making the silent mutations to accommodate the BspE I restriction site. This is the same manner in which the α6/3 chimera was created by Dowell et al. (2003). This restriction site was also introduced in α4 and α6 Mutations were made using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene La Jolla, CA). Sequences were confirmed with automated fluorescent sequencing at the University of Florida core facility.

Table 3.

Alpha4 and alpha6 Sequences

| Signal sequence and extracellular domain | |

|---|---|

| Rat_alpha4 | MANSGTGAPPPLLLLPLLLLLGTGLLPASSHIETRAHAEERLLKRLFSGYNKWSRPVA 58 |

| Rat_alpha6 | MLNGWGRGDLRSGLCLWICGFLAFFKGSR-----GCVSEEQLFHTLFAHYNRFIRPVE 53 |

| Rat_alpha4 | NISDVVLVRFGLSIAQLIDVDEKNQMMTTNVWVKQEWHDYKLRWDPGDYENVTSIRIPSE 118 |

| Rat_alpha6 | NVSDPVTVHFELAITQLANVDEVNQIMETNLWLRHVWKDYRLCWDPTEYDGIETLRVPAD 113 |

| Rat_alpha4 | LIWRPDIVLYNNADGDFAVTHLTKAHLFYDGRVQWTPPAIYKSSCSIDVTFFPFDQQNCT 178 |

| Rat_alpha6 | NIWKPDIVLYNNAVGDFQVEGKTKALLKYDGVITWTPPAIFKSSCPMDITFFPFDHQNCS 173 |

| Rat_alpha4 | MKFGSWTYDKAKIDLVSMHSRVDQLDFWESGEWVIVDAVGTYNTRKYE 226 |

| Rat_alpha6 | LKFGSWTYDKAEIDLLIIGSKVDMNDFWENSEWEIVDASGYKHDIKYN 221 |

| Rat_alpha4 | CCAEIYPDITYAFI |

| Rat_alpha6 | CCEEIYTDITYSFY |

| Transmembrane* and intracellular domains | |

| Rat_alpha4 | IRRLPLFYTINLIIPCLLISCLTVLVFYLPSECG-EKVTLCIS 282 |

| Rat_alpha6 | IRRLPMFYTINLIIPCLFISFLTVLVFYLPSDCG-EKVTLCIS 277 |

| Rat_alpha4 | VLLSLTVFLLLITEIIPSTSLVIPLIGEYLLFTMIFVTLSIVITVFVLNVHHRSPRTHT 341 |

| Rat_alpha6 | VLLSLTVFLLVITETIPSTSLVIPLVGEYLLFTMIFVTLSIVVTVFVLNIHYRTPATHT 336 |

| Rat_alpha4 | MPAWVRRVFLDIVPRLLFMKRPSVVKDNCRRLIESMHKMANAPRFWPEPVGEPGILSDIC 401 |

| Rat_alpha6 | MPKWVKTMFLQVFPSILMMRRPLD------KTKEMDGVKDPK------------------ 372 |

| Rat_alpha4 | NQGLSPAPTFCNPTDTAVETQPTCRSPPLEVPDLKTSEVEKASPCPSPGSCPPPKSSSGA 461 |

| Rat_alpha6 | ------THTKRPAKVKFTHRKEPKLLKECRHCHKS----SEIAP--GKRLSQQPAQWVTE 420 |

| Rat_alpha4 | PMLIKARSLSVQHVPSSQEAAEDGIRCRSRSIQYCVSQDGAASLADSKPTSSPTSLKARP 521 |

| Rat_alpha6 | ------------------------------------------------------------ |

| Rat_alpha4 | SQLPVSDQASPCKCTCKEPSPVSPVTVLKAGGTKAPPQHLPLSPALTRAVEG 573 |

| Rat_alpha6 | --------------------------------------NSEHPPDVEDVIDS 434 |

| Rat_alpha4 | VQYIADHLKAEDTDFSVKEDWKYVAMVIDRIFLWMFIIVCLLGTVGLFLPP 624 |

| Rat_alpha6 | VQFIAENMKSHNETKEVEDDWKYMAMVVDRVFLWVFIIVCVFGTVGLFLQP 485 |

| Rat_alpha4 | WLAAC--- 629 |

| Rat_alpha6 | LLGNTGAS 493 |

Putative transmembrane domains are in bold. The two residues of sequence difference between α4 and α6 in the extracellular loop (ECL) between TM2 and TM3 are underlined. These residues were reversed in the ECL mutants (Figure 10).

The α6/4 chimera was created by digesting α6/3 and α6 with BspE I and Spe I and ligating the α6 N-terminal portion with the α4 carboxy terminal portion and vector. Alpha4/6 was created by digesting α4 and α6 with BspE I and Xba I and ligating the α4 N-terminal portion with the α6 carboxy terminal portion and vector.

Only two amino acids differ between α4 and α6 in the putative extracellular loop (ECL) between the second and third transmembrane domains (Table 3). These were exchanged using the QuikChange kit sequentially and confirmed with automated fluorescent sequencing to create α4(α6ECL) and α4/6(αECL).

Preparation of RNA

Additional rat nAChR clones were also obtained from Dr. Jim Boulter (UCLA). After linearization and purification of cloned cDNAs, RNA transcripts were prepared in vitro using the appropriate mMessage mMachine kit from Ambion Inc. (Austin, TX).

Expression in Xenopus oocytes

Mature (>9 cm) female Xenopus laevis African toads (Nasco, Ft. Atkinson, WI) were used as the source of oocytes. Prior to surgery, frogs were anesthetized by placing the animal in a 1.5 g/L solution of MS222 (3-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester; Sigma, St. Louis MO) for 30 min. Oocytes were removed from an abdominal incision.

In order to remove the follicular cell layer, harvested oocytes were treated with 1.25 mg/ml collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Freehold, NJ) for 2 hours at room temperature in calcium-free Barth's solution (88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 2.38 mM NaHCO3, 0.82 mM MgSO4, 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 12 g/l tetracycline). Subsequently, stage 5 oocytes were isolated and injected with 50 nl (5–20 ng) each of the appropriate subunit cRNAs. Recordings were made 2 to 7 days after injection. Although the absolute magnitude of the evoked current responses increased over time, the normalized values of the experimental responses did not vary significantly over time.

Chemicals

α-Conotoxin PIA was synthesized as previously reported (Dowell et al., 2003). The bis-azaaromatic quaternary ammonium compounds were synthesized at the University of Kentucky utilizing previously reported procedures (Ayers et al., 2002; Crooks et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2007). All other chemicals for electrophysiology were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Fresh acetylcholine (ACh) stock solutions were made daily in Ringer's solution and diluted.

Electrophysiology

Experiments were conducted using OpusXpress 6000A (Molecular Devices, Union City CA) (Stokes et al., 2004). OpusXpress is an integrated system that provides automated impalement and voltage clamp of up to eight oocytes in parallel. Cells were automatically perfused with bath solution, and agonist solutions were delivered from a 96-well plate. Both the voltage and current electrodes were filled with 3 M KCl. The agonist solutions were applied via disposable tips, which eliminated any possibility of cross-contamination. Drug applications alternated between ACh controls and experimental applications. Flow rates were set at 2 ml/min for experiments with α7 receptors and 4 ml/min for other subtypes. Cells were voltage-clamped at a holding potential of −60 mV. Data were collected at 50 Hz and filtered at 20 Hz. Drug applications were 12 seconds in duration followed by a 181 second washout periods with α7 receptors and 8 seconds with 241 second washout periods for other subtypes.

Experimental protocols and data analysis

Each oocyte received two initial control applications of ACh, an experimental drug application, and then a follow-up control application of ACh. The control ACh concentrations were 60 µM for α7, 10 µM for α4β2, α4β4, and α4/6β4 receptors and 100 µM for the other subunit combinations tested. The peak amplitude and the net charge (Papke and Papke, 2002) of experimental responses were calculated relative to the preceding ACh control responses in order to normalize the data, compensating for the varying levels of channel expression among the oocytes. After each experimental measurement cells were rechallenged with ACh at the control concentrations. This allowed for the determination of residual inhibitory effects or rundown. Cells which showed more than a 25% variation between two consecutive ACh-evoked responses were not used for further experimental treatments. Means and standard errors (SEM) were calculated from the normalized responses of at least four oocytes for each experimental concentration. Unless otherwise noted, data presented are based on measurements of net charge for α7 receptors and of peak currents for all other subtypes.

For concentration-response relationships, data were plotted using Kaleidagraph 3.0.2 (Abelbeck Software; Reading, PA), and curves were generated as the best fit of the average values to the Hill equation:

where Imax denotes the maximal response for a particular agonist/subunit combination, and n represents the Hill coefficient. For the calculation of IC50 values, negative Hill slopes were applied and Imax was constrained to equal 1. Error estimates of the IC50 values are the standard errors of the parameters based on the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm used for the generation of the fits (Press, 1988). T-tests were used to determine statistical significance between antagonist activity at specific concentrations between pairs of nAChR subunit combinations.

Results

Evaluation of the subtype selectivity of mecamylamine and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DH βE)

Mecamylamine is one of the most commonly used neuronal nAChR antagonists, believed to have some selectivity for ganglionic (i.e.,β4-containing) receptors (Papke et al., 2001b), while DHβE is a competitive antagonist, reportedly selective for α4-containing receptors (Chavez-Noriega et al., 1997). We tested these antagonists on the basic models for ganglionic (α3β4) nAChR, and brain heteromeric (α4β2) and homomeric (α7) nAChRs. As shown in Figure 1, experiments confirmed that α3β4 was the most sensitive to mecamylamine inhibition and α4β2 was the most sensitive to DHβE inhibition (IC50 values are given in Table 1).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal nAChR subunits by mecamylamine (upper panel) or DHβE (lower panel). Each panel shows raw data traces for α4β2 and α3β4 receptors on the left and on the right the averaged normalized responses (± SEM, n ≥ 4) from oocytes expressing α4β2, α3β4, or α7 subunits to the co-application ACh and increasing concentrations of antagonist. Each response to the co-application of ACh and antagonist was normalized based on the response of the same cell to the control application of ACh alone (see Methods for control ACh concentrations used).

Table 1.

Table 1A: IC50 values for DHβE and mecamylamine against various nAChR subunit combinations

| IC50 | ||

|---|---|---|

| subunits | DHβE | mecamylamine |

| α7 | 8 ± 1 µM | 15.6 ± 1.4 µM |

| α4β2 | 0.10 ± 0.01 µM | 3.6 ± 0.2 µM |

| α3β4 | 26 ± 2 µM | 0.39 ± 0.10 µM |

| α3β2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 µM | 7.6 ± 1.4 µM |

| α3β2β3 | 2.9 ± 0.3 µM | 1.0 ± 0.1 µM |

| α6/3β2β3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 µM | 11 ± 3 µM |

| α6/4β4 | 4.6 ± 0.5 µM | 0.50 ± 0.40 µM |

| α4β4 | 0.19 ± 0.01 µM | 0.33 ± 0.04 µM |

| α4/6β4 | 0.38 ± 0.03 µM | 1.0 ± 0.1 µM |

| Table 1B: IC50 values for DHβE, mecamylamine, tetracaine and novel synthetic quaternary ammonium analogs against α4β4 and α4/6β4 subunit combinations and the ECL mutants. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | α4β4 | α4/6β4 | Range of IC50 ratio* |

| tetracaine | 5 ± 1 µM | 2.3 ± 0.2 µM | 1.60 – 2.90 |

| bPiDDb | 0.7 ± 0.1 µM | 2.7 ± 0.5 µM | 0.19 – 0.36 |

| bPiPyB | 14.5 ± 2.8 µM | 5.2 ± 0.6 µM | 2.02 – 3.76 |

| bIQDDB | 0.8 ± 0.1 µM | 1.3 ± 0.3 µM | 0.44 – 0.90 |

| bIQPB | 2.1 ± 0.3 µM | 3.7 ± 0.7 µM | 0.41 – 0.80 |

| bIQPyB | 5.4 ± 0.2 µM | 2.3 ± 0.6 µM | 1.79 – 3.29 |

| bPiBB | 6.0 ± 0.6 µM | 2.0 ± 0.3 µM | 2.35 – 3.88 |

| bPiByB | 4.4 ± 0.3 µM | 0.8 ± 0.2 µM | 4.10 – 7.83 |

| α4(α6ECL)β4 | α4/6(α4ECL)β4 | ||

| bPiByB | 3.0 ± 0.1 µM | 1.4 ± 0.2 µM | 1.81 – 2.58 |

Given the estimated IC50 and their associated error estimates, this is the range for the likely ratios of IC50 values. For example for DHβE, (0.19 − 0.01)/(0.38+0.03) = 0.44 represents one bracket for the ratio range while (0.19 + 0.01)/(0.38−0.03) = 0.57 represents the other.

Chimeric subunits with the α6 extracellular domain

We adopted and extended the approach introduced by Dowell et al. (2003) to identify the effects of these classic antagonists on receptors containing the α6 extracellular domain by utilizing chimeric subunits. The first chimera, shown in Figure 2, is the previously published α6/3 chimera (Dowell et al., 2003; Papke et al., 2005). To further confirm that the α6 extracellular domain alone is sufficient to produce α6-like pharmacology regarding agonists and competitive antagonists, we constructed a second α6 chimera, α6/4, incorporating the transmembrane and intracellular domains of the rat α4 subunit. A human α6/4 chimera has also been described (Evans et al., 2003; Kuryatov et al., 2000). To provide a novel tool for evaluating the potential α6 selectivity of noncompetitive antagonists, we constructed an α4/6 chimera containing the extracellular domain of α4 and the transmembrane and intracellular domains of α6.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of wild-type and chimeric subunits used to study the influence of α6 subdomains of the pharmacological properties of neuronal nAChR. The putative transmembrane domains of α6 are identified in the Kyte-Doolittle plot (11/1 generated by DNA Strider) at the top of the figure. These domains are identified by the wide bars in the schematics below. All the schematics are at the same scale as the Kyte-Doolittle plot but omit the signal sequences. An expansion and overlay of Kyte-Doolittle hydrophobicity plots for the transmembrane domains of α6 (black) and α4 (gray) is shown at the bottom of the figure.

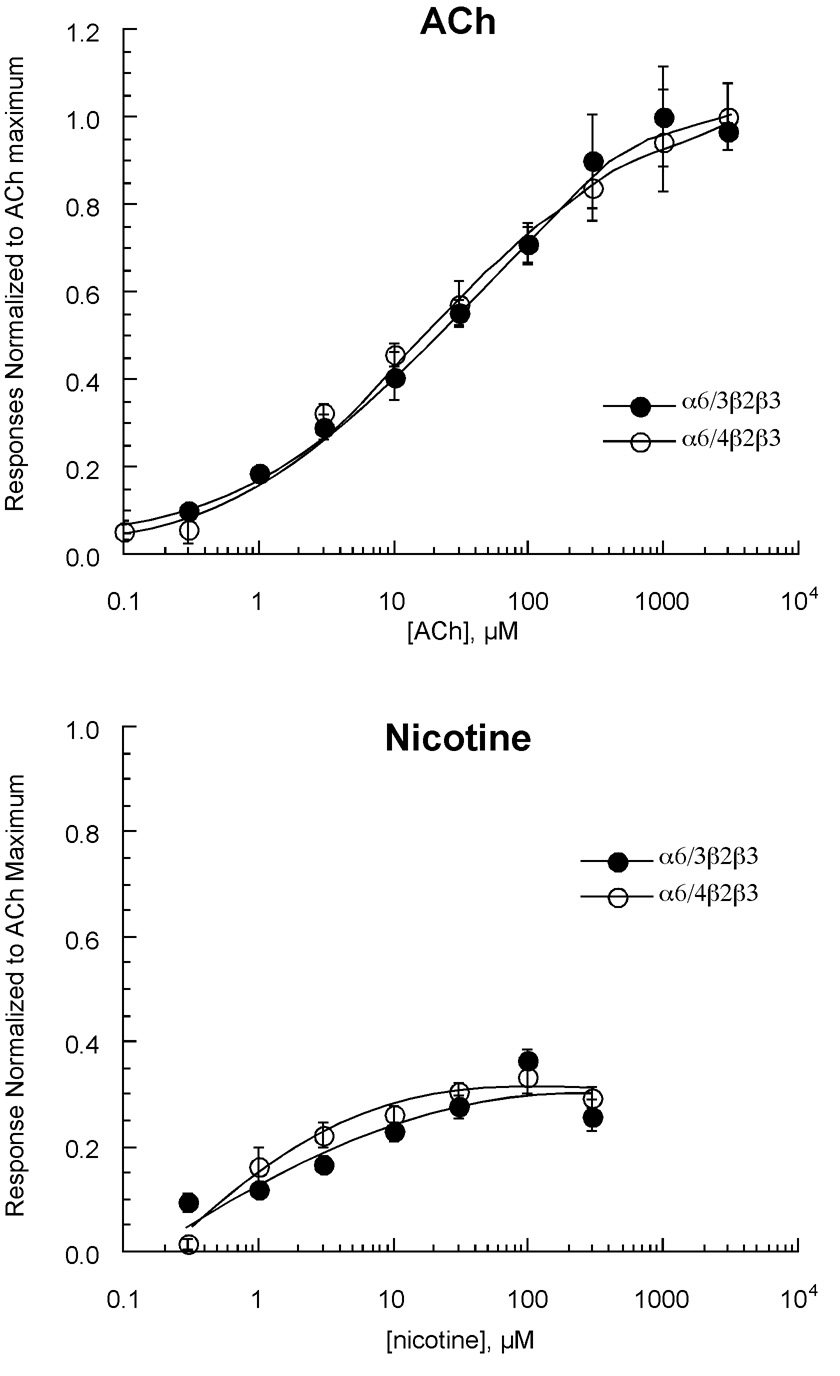

We first tested the hypothesis that the differing transmembrane and intracellular regions of the α6/3 and α6/4 would have relatively little effect on the concentration response relationships to agonists. Since some native α6 receptors assemble with both β2 and β3 subunits (Gotti et al., 2006), the α6/3 and α6/4 chimeras were co-expressed with β2 and β3. The receptors formed had essentially identical concentration-response relationships to the agonists ACh and nicotine (Figure 3). The ACh EC50 values for both chimeras were approximately 20 µM while we have previously reported (Papke et al., 2007) that the ACh EC50 for α3β2β3 receptors is approximately 90 µM. Our study of mecamylamine and DHβE was then extended to systematically evaluate the effects the β3 subunit and the α6 extracellular domains on the inhibitory effects of these compounds. Comparison of the responses of α3- and β2 expressing cells to those additionally expressing β3 indicated that the β3 subunit increased sensitivity to mecamylamine (Figure 4). However, cells expressing the α6/3 chimera along with β2 and β3 had lower sensitivity to mecamylamine than those expressing α3β2β3, suggesting an interaction between the way in which the α6 extracellular domain affected ACh activation and subsequent use-dependent block by mecamylamine. As shown in Figure 4, the α6 extracellular domain also led to a small increase in sensitivity to DHβE, while β3 expression did not affect the potency of this competitive antagonist.

Figure 3.

Concentration-response curves obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal nAChR α6/3β2β3 or α6/4β2β3 subunits given ACh (upper panel) or nicotine (lower panel). Each panel shows the averaged data (± SEM, n ≥ 4) normalized to the maximum ACh responses obtained from the same oocytes.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal nAChR subunits by mecamylamine (upper panel) or DHβE (lower panel). Each panel shows the averaged normalized data (± SEM, n ≥ 4) from oocytes expressing α3β2, α3β2β3, or α6/3β2β3 subunits to the co-application of ACh and antagonist. Each response to the co-application of ACh and antagonist was normalized based on the response of the same cell to the control application of ACh alone (see Methods for control ACh concentrations used). Significant (p<0.05) differences in inhibition were found between receptor subtypes at the concentrations indicated. ⊗ represents significant difference between α3β2 and α3β2β3 responses, # represents significant difference between α3β2β3 and α3/6β2β3 responses, and * represents significant difference between α3β2 and α3/6β2β3 responses.

A chimeric subunit with the α6 transmembrane and intracellular domains

The nicotinic noncompetitive antagonist mecamylamine has been shown to have some utility at increasing success in smoking cessation (Rose et al., 1994b). The selectivity of mecamylamine for neuronal nAChR compared to muscle-type nAChR is based on specific sequence elements in the transmembrane domains (Webster et al., 1999). However, as our current study shows, mecamylamine is most effective at inhibiting ganglionic (α3β4-containing) receptors, and these are not likely to be the best targets for treating nicotine dependence. The fact that α6 expression is typically high in dopaminergic neurons associated with reward suggests that antagonists with a selectivity for α6-containing receptors might be useful drugs for blocking nicotine-mediate reward in the brain. While the α6/3 chimera has been useful in identifying the selective competitive inhibition of α6-containing receptors by select conus toxins (Dowell et al., 2003; McIntosh et al., 2004), conus toxins are not good drug candidates. Moreover, it is unlikely that chimeras containing the α6 extracellular domain (i.e. α6/3 and α6/4) will be at all useful for identifying noncompetitive antagonists with selectivity for α6, due to the fact that the effectiveness of noncompetitive antagonists is expected to be dependent on sequence in the transmembrane domains, as was shown for mecamylamine. Therefore, we created an expressible construct (α6/4) that contained the α6 transmembrane and intracellular domains in combination with the α4 extracellular domain (see Methods).

Functional properties of the α4/6 chimera

The α4/6 chimera was co-expressed with various other subunits to identify a useful beta subunit partner. The α4/6 subunit did not function readily when co-expressed with β2 and β3 (data not shown) but did form functional receptors after several days when co-expressed with β4 Thus, we used α4β4 receptors for comparisons to determine the pharmacological effects associated with the presence of the α6 transmembrane and intracellular domains. Co-expression the of the α4/6 chimera with β4 had the additional advantage that functional receptors formed from this simple pairwise subunit combination reduced the variables that might arise with many different possible combinations of three subunits. The responses of α4β4 and α4/6β4 receptors were measured over a range of ACh concentrations (Figure 5). The EC50 for ACh with α4β4 receptors was 15 ± 1 µM. The responses of α4/6β4 receptors were fit with an EC50 of 6.3 ± 1.5 µM.

Figure 5.

Concentration-response curves obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal nAChR α4β4 or α4/6β4 subunits given ACh. Shown are the averaged data (± SEM, n ≥ 4) normalized to the maximum ACh responses obtained from the same oocytes.

In order to confirm that the receptors containing the α4/6 subunit retain α4-like functionality with competitive antagonists, we compared α4β4 receptors to α4/6β4 and α6/4β4 receptors in regard to their sensitivity to DHβE and the α6-selective α-conotoxin PIA (Dowell et al., 2003). As shown in Figure 6, α4/6β4 receptors were nearly as sensitive as α4β4 receptors to DHβE (IC50 values in Table 1), while the α6/4β4 receptors were more than 10-fold less sensitive. In contrast, when receptors were pre-incubated in 100 nM α-conus PIA toxin and then tested for their ACh responses in the continued presence of the toxin, both α4/6β4 and α4β4 receptors were relatively insensitive (Figure 6), while the α6/4β4 receptors were effectively blocked in a slowly reversible manner.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal α4β4, α6/4β4 or α4/6β4 nAChR subunits to competitive antagonists. The inhibition of responses to DHβE are shown in the upper panel. The lower panel illustrates the effects of 100 nM α-conotoxin PIA on ACh-evoked responses. Initial control responses to 100 µM ACh were obtained, then cells were incubated for 5 min in 100 nM toxin (plus 0.1 mg/ml protease-free BSA), and then ACh was applied in the continued presence of the toxin. Each response to the co-application of ACh and antagonist was normalized based on the response of the same cell to the control application of ACh alone (see Methods for control ACh concentrations used). Also shown are the Ach-evoked responses obtained after a 5 min washout of the toxin. Each panel shows the averaged normalized data (± SEM, n ≥ 4) from oocytes.

Two known nAChR noncompetitive antagonists, mecamylamine and the local anesthetic tetracaine, were tested on α4β4 and α4β4 receptors. As shown in Figure 7, cells with receptors containing the transmembrane and intracellular domains of α6 were less sensitive to mecamylamine than cells expressing wild-type α4β4. Tetracaine is a relatively unique noncompetitive antagonist, which has been shown to block both open and closed channels of muscle-type nAChR (Papke and Oswald, 1989). Cells with receptors containing the transmembrane and intracellular domains of α6 appeared somewhat more sensitive to tetracaine than cells expressing wild-type α4β4 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Inhibition of peak current responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal α4β4 or α4/6β4 nAChR subunits by mecamylamine (upper panel) or tetracaine (lower panel). Each panel shows the averaged normalized responses (± SEM, n ≥ 4) from oocytes expressing those subunits to the co-application of ACh and antagonist. Each response to the co-application of ACh and antagonist was normalized based on the response of the same cell to the control application of ACh alone (see Methods for control ACh concentrations used). Significant differences in inhibition were found at the concentrations indicated (* indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p <0.01).

Evaluation of compounds active at inhibiting nicotine-evoked dopamine release with the α4/6 chimera

Several classes of bis-azaaromatic quaternary ammonium compounds have recently been described which can produce potent partial inhibition of nicotine-evoked dopamine release from striatal slices (Crooks et al., 2004). One of the best characterized compounds from this large family of compounds is bPiDDB (Figure 8A), which has been shown to be active at decreasing dopamine-mediated behaviors including nicotine self-administration in rats (Neugebauer et al., 2006), and when delivered to the ventral tegmentum is able to inhibit the release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens stimulated by the systemic delivery of nicotine. The inhibitory activity of bPiDDB has been investigated on numerous AChR subtypes expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Rahman et al., 2008). In oocyte experiments, bPiDDB was most potent for inhibiting muscle type and β4-containing receptors (IC50 values 200 – 500 nM) and less potent for β2-containing receptors (IC50 values 10 – 20 µM). The mechanism of bPiDDB inhibition of nAChR expressed in Xenopus oocytes is apparently noncompetitive since the inhibition of α4β4 responses evoked by high concentrations of ACh is roughly comparable to the inhibition of responses evoked by low concentrations of ACh. In the upper plot of Figure 8A, 10 µM bPiDDB produced a 40% reduction in the Imax for ACh and only a relatively small change in the apparent EC50 values (16± 1 µM and 56±11 µM in the absence and presence of bPiDDB, respectively). Similar results have been obtained with the inhibition of α4β2 and α6/3β2β3 receptors by bPiDDB (data not shown).

Figure 8.

A) The structure of bPiDDB (N,N’-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-picolinium dibromide), a novel bis-azaaromatic quaternary ammonium compound which functions as a partial antagonist of nicotine-evoked dopamine release (Crooks et al., 2004), is shown at the top of the figure. The upper plot is a competition experiment, comparing responses evoked by ACh or ACh plus 10 µM bPiDDB. The lower plot illustrates the inhibition of peak current responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal α4β4 or α4/6β4 nAChR subunits by bPiDDB. B) The structure of bPiPyB (1,2-bis-[5-(3-picolinium)-pent-1-ynyl]-benzene dibromide) is shown at the top of the panel. The plot illustrates the inhibition of peak current responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal α4β4 or α4/6β4 nAChR subunits by bPiPyB. Each panel shows the averaged normalized responses (± SEM, n ≥ 4) from oocytes expressing those subunits to the co-application of ACh and antagonist. Each response to the co-application of ACh and antagonist was normalized based on the response of the same cell to the control application of ACh alone (see Methods for control ACh concentrations used). Significant differences in inhibition were found at the concentrations indicated (* indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p <0.01).

It has previously been reported (Rahman et al., 2008) that there is no significant difference in the IC50 values for the bPiDDB inhibition of α3β2β3 and α6/3β2β3 receptors (IC50 = 20 ± 2.5 and 34±10 µM, respectively). We therefore used the α4/6 chimera to determine if bPiDDB would selectively inhibit receptors based on the presence or absence of the α6 transmembrane and intracellular domains. As shown in Figure 8A (lower plot), bPiDDB was more potent (Table 1B) at inhibiting receptors containing the complete α4 subunit than at inhibiting those which contained the α4/6 chimera.

In screens of other bis-azaaromatic quaternary ammonium compounds at a probe concentration of 1 µM, we identified bPiPyB (Figure 8B) as an analog which produced more inhibition of α4/6β4 receptors than α4β4 This selectivity between α4/6β4 and α4β4.receptors was confirmed with concentration-response studies (Figure 8B). Both bPiDDB and bPiPyB contain two 3-picolinium head groups separated by a linker containing 12 carbons. The most salient differences between the two compounds are in regard to the rigidity of the linkers and the likely conformational orientation (i.e. the intra-molecular distance between the head groups). In the case of bPiPyB, the molecule is constrained to an angular or ‘folded’ conformation as a result of the presence of the structurally rigid 1,2-diynylphenyl moiety. In the bPiDDB molecule, the rigid 1,2-diynylphenyl moiety is absent, and the molecule is conformationally very flexible, due to the presence of the N,N’-1,12-dodecanyl linker; this allows bPiDDB to adopt a more extended or ‘linear’ conformation than the bPiPyB molecule. We investigated the relative significance of these conformational differences between bPiDDB and bPiPyB by testing three other related bis-azaaromatic quaternary ammonium compounds: bIQDDB (Figure 9A) and bIQPyB (Figure 9B), which are homologs of bPiDDB and bPiPyB, respectively, except that they incorporate isoquinolinium rather than 3-picolinium head groups into their structure, and bIQPB (Figure 9C) is an intermediate structure in which the 1,2-diynylphenyl moiety in bPiPyB has been replaced with the more conformationally flexible 1,2-diethylphenyl moiety. Thus, bIQPB lacks the triple bonds in the linker units, which confer significant rigidity to both bPiPyB and bIQPyB.

Figure 9.

A) The structure of bIQDDB (N,N’-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-isoquinolinium dibromide) is shown at the top of the panel. The plot illustrates the inhibition of peak current responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal α4β4 or α4/6β4.nAChR subunits by bIQDDB. B) The structure of bIQPB (1,2-bis-(5-isoquinolinium-pentyl)-benzene dibromide) is shown at the right of the panel. The plot illustrates the inhibition of peak current responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal α4β4 or α4/6β4 nAChR subunits by bIQPB. C) The structure of bIQPyB (1,2-bis-(5-isoquinolinium-pent-1-ynyl)-benzene dibromide) is shown at the right of the panel. The plot illustrates the inhibition of peak current responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal α4β4 or α4/6β4 nAChR subunits by bIQPyB. The data in each panel show the averaged normalized responses (± SEM, except where indicated, n ≥ 4) from oocytes expressing those subunits to the co-application of ACh and antagonist. Each response to the co-application of ACh and antagonist was normalized based on the response of the same cell to the control application of ACh alone (see Methods for control ACh concentrations used). Significant differences in inhibition were found at the concentrations indicated (* indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p <0.01).

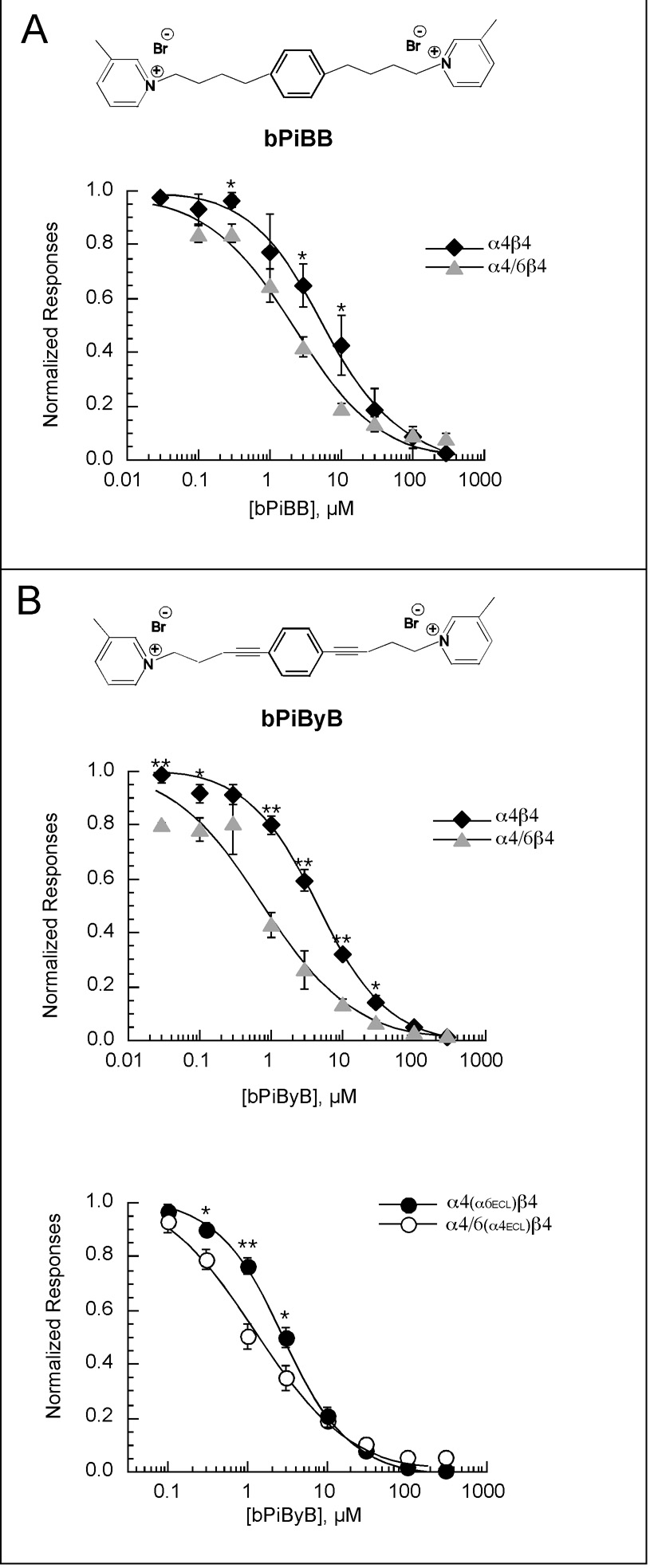

As shown in Figure 9, neither bIQDDB nor bIQPB showed any significant difference in their inhibition of α4β4 and α4/6β4 receptors. However, like bPiPyB, bIQPyB produced significantly more inhibition of receptors containing the α4/6 chimera. This observation suggested that conformational rigidity in the linker unit per se might be more important for inhibition of nAChRs containing the α6 transmembrane and intracellular domains than the presence of a centrally placed 1,2-substituted phenyl moiety in the linker unit. We therefore tested two additional analogs of bPiDDB, bPiBB and bPiByB (Figure 10), in which the linker incorporated a central 1,4-diethylphenyl (bPiBB) and 1,4-diynylphenyl (bPiByB) moiety to afford a more linear analog comparable to an extended conformation of the pPiDDB molecule. As shown in Figure 11, bPiBB showed some selectivity for the α4/6-containing receptors, and this selectivity was further improved by the presence of the rigid triple bonds in bPiByB.

Figure 10.

A) The structure of bPiBB (1,4-bis-[4-(3-picolinium)-butyl]-benzene dibromide) is shown at the top of the panel. The plot illustrates the inhibition of peak current responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal α4β4 or α4/6β4 nAChR subunits by bPiBB. B) The structure of bPiByB (1,4-bis-[4-(3-picolinium)-but-1-ynyl]-benzene dibromide) is shown at the top of the panel. The upper plot illustrates the inhibition of peak current responses obtained from oocytes expressing rat neuronal α4β4 or α4/6β4 nAChR subunits by bPiByB (n = 4 for the α4β4 data and n = 3 for the α4/6β4 data). The lower plot shows the inhibition produced by bPiByB of α4(α6ECL)β4 or α4/6(α4ECL)β4, double mutants which contain in α4 the two residues from α6 which differ in the extracellular loop between TM2 and TM3 (see Table 3) and in the α4/6 chimera, the two extracellular loop residues from α4, respectively. The data in each panel show the averaged normalized responses (± SEM) from oocytes expressing those subunits to the co-application of ACh and antagonist. Each response to the co-application of ACh and antagonist was normalized based on the response of the same cell to the control application of ACh alone (see Methods for control ACh concentrations used). Significant differences in inhibition were found at the concentrations indicated (* indicates p<0.05, ** indicates p <0.01).

A potentially important subdomain within the α6 portion of the α4/6 chimera is the putative extracellular loop (ECL) between the second and third transmembrane domains (Table 3). This region has been shown to be of crucial importance for the coupling of agonist binding to channel activation (Bouzat et al., 2004; Lummis et al., 2005) and may be accessible to noncompetitive antagonists. There are two amino acids that differ between α4 and α6 in the ECL (Table 3). At the start of the ECL α4 has an isoleucine where α6 has a threonine and 12 residues down α4 has an isoleucine where α6 has a valine. To determine whether these differences had significance for inhibition by bPiByB, we mutated α4 to have the α6 sequence at these sites (α4(α6ECL)) and the α4/6 chimera to have the α4 sequence at these sites (α4/6(α4ECL)). These mutations did appear to reduce the selectivity of bPiByB, but not to reverse it.

Discussion

Recent work with transgenic animals (Cordero-Erausquin et al., 2000) and new pharmacological tools (Nai et al., 2003) have been informative with respect to the complex nature of the nAChR subtypes involved in nicotine self-administration, and the α6 subunit is part of this rich mix. This gene is expressed at high levels in the ventral tegmental area and, compared to α4, α6 has a very restricted pattern of expression in the brain, being associated almost exclusively with dopaminergic neurons, including those that are the source of the nicotine reinforcement (Charpantier et al., 1998; Goldner et al., 1997; Le Novere et al., 1996). Toxins shown to have some selectivity for α6-containing receptors in heterologous expression systems, are also effective at blocking a significant fraction of agonist-evoked dopamine release from synaptosomes (Salminen et al., 2007; Salminen et al., 2004), providing strong support for the hypothesis that α6* receptors maybe an useful target for blocking the dopamine-mediated aspects of nicotine dependence. The conus toxins with α6 selectivity are competitive antagonists and therefore could be characterized with chimeras that contain the α6 extracellular domain (Dowell et al., 2003; McIntosh et al., 2004). However, since these molecules are proteins, they clearly are not good drug candidates. Alternative nAChR antagonists that do penetrate the brain when given systemically, such as mecamylamine and 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-4-yl heptanoate (TMPH) are noncompetitive antagonists (Damaj et al., 2005). Not only are these noncompetitive agents active in the CNS when given systemically, they may discriminate between nAChR subtypes based on single amino acid differences in the subunit sequences (Papke et al., 2005; Webster et al., 1999). These observations provide the rationale for seeking α6-selective noncompetitive antagonists.

Unfortunately, the pharmacological properties of α6-containing receptors have been difficult to characterize, since this subunit expresses poorly in heterologous systems and may even act as a dominant negative factor when expressed in combination with other subunits (Papke, unpublished observation). One successful approach for identifying properties of the α6 agonist binding site has been the chimeric subunit (α6/3), containing the α6 extracellular domain and the transmembrane and intracellular domains of α3 (Kuryatov et al., 2000) This chimera functions reasonably well when co-expressed with β2 and β3. A rat α6/3 chimera was used to confirm that the α-conotoxin PIA, which blocks a significant fraction of nicotine-evoked dopamine release from synaptosomes (Azam and McIntosh, 2006), is in fact selective for α6-containing nAChRs (Dowell et al., 2003).

In this paper, we report two new α6 chimeras based on combinations with the rat α4 subunit. We show that the α6/4 chimera is comparable to the α6/3 chimera in regard to the pharmacology of agonists and competitive antagonists, while the α4/6 chimera responds to these agents like the wild-type α4 However, when co-expressed with β4, the α4/6 chimera shows a pattern of sensitivity to antagonists different from that of α4β4 receptors, suggesting that this chimera will provide a useful tool in the further study of new potential drugs for treating nicotine dependence.

Our work supports and expands upon previous studies of the established pharmacological tools, mecamylamine, DHβE, and α-conotoxin PIA. High sensitivity to DHβE is clearly related to the presence of the extracellular domain of α4. We confirm, with a larger number of subtypes than previously tested, that mecamylamine shows selectivity for β4-containing receptors over β2-containing receptors. This was true regardless of which alpha subunit was co-expressed with β4 While the selectivity of mecamylamine between ganglionic and muscle-type receptors can be attributed to specific residues at the 6' and 10' sites of the second transmembrane domain (numbering within the second transmembrane domain alpha helix (TM2) as per Miller et al. (Miller, 1989), it is possible that the selectivity observed between β2 and β4 containing receptors may be related to a single site difference at the 13' position (Table 2).

Table 2.

TM2 domains

| α3 | VTLCISVLLSLTVFLLVITE |

| α4 | VTLCISVLLSLTVFLLLITE |

| α6 | VTLCISVLLSLTVFLLVITE |

| α7 | ISLGITVLLSLTVFMLLVAE |

| β2 | MTLCISVLLALTVFLLLISK |

| β4 | MTLCISVLLALTFFLLLISK |

| β3 | LSLSTSVLVSLTVFLLVIEE |

Several observations support the validity of using separate chimeras like α6/3, α6/4 and α4/6 to independently determine pharmacological properties provided by the ligand-binding and pore-forming domains. For example, the ACh and nicotine concentration-response curves shown in Figure 3 show essentially no difference that may be attributed to the α3 or α4 transmembrane and intracellular domains. Likewise, the competitive antagonists shown in Figure 6 effectively discriminate subtypes based on the presence or absence of the α6 extracellular domain.

We saw significant systematic differences in the activity of the noncompetitive antagonists tested with α4β4 and α4/6β4 receptors, confirming that this model system is sufficiently sensitive to aid in the development of truly α6-selective antagonists. Sequence identity between α4 and α6 is nearly 90% in the transmembrane domains, but the differences are enough to significantly impact the hydrophobicity profiles around the mouth of the TM2 and through the extracellular loop that connects TM2 and TM3 (Figure 2). Even single amino acid differences in these domains can result in very large differences in the responses to noncompetitive antagonists (Palma et al., 1998; Papke et al., 2005; Papke et al., 2001a; Webster et al., 1999).

Mecamylamine and the lidocaine derivative QX-222 are known to bind directly in the nAChR channel (Papke et al., 2001a; Webster et al., 1999), and these molecules are not much larger than the head groups of the bis-azaaromatic quaternary ammonium compounds in the present study, so it is perhaps a reasonable hypothesis that these compounds are binding at alternative sites above the membrane's electric field, as was shown to be the case for the similar bifunctional compound BTMPS, which contains two sterically hindered amino groups on piperidine rings joined by a 10-carbon aliphatic linker (Francis et al., 1998). The degree of conformational rigidity in the bis-azaaromatic quaternary ammonium molecules seemed to be a key factor for selective inhibition of receptors containing α6 transmembrane and intracellular domains. If in fact, these bifunctional agents bind to multiple sites in the receptor, our data suggest that the sites might be closer together in α4β4 receptors than in α4/6β4, requiring greater flexibility in the linker to effectively allow the putatively active cationic head groups to bind. Likewise, if the putative binding sites are further apart in α4/6β4 receptors than in α4β4 receptors, then an increase in the rigidity of the linkers might promote binding if the molecules are constrained to more fully extended or linear conformations. The observation that molecules restricted to a fully extended conformation, are favored for inhibiting α4/6 suggests that the head group separation distance in the extended conformation might be close to the distance between the sites on the separate subunits in the receptor. If this is so, then it is a somewhat confounding observation that rigidity is favored for both the linear and the folded molecules, since they cannot equally be templates for positioning the head groups to the same sites. However, if there are three α4/6 subunits per receptor, then these subunits and their associated binding sites will be juxtaposed as either adjacent subunits, or as subunits opposite to each other. It could be the case that if the head groups are binding to pairs of sites, each in single subunits, compounds with a folded conformation (bIQPyB and bIQPB) might bind best to sites in adjacent subunits within the pentamer, while bis-azaaromatic quaternary ammonium compounds with the extended linear conformation (bPiBB and bPiByB) might bind best to sites in subunits that are opposite to each other. Our results with the ECL mutants suggest that this portion of the protein may modulate inhibition by the relatively selective compound bPiByB, but that the sequence differences in this domain are in themselves insufficient to account for the selectivity. The ECL domain may partially contribute to a binding site or alternatively, the ECL differences may affect other domains of the protein important for the inhibition of function. The latter possibility seems likely, considering that the ECL is believed to be a hinge point affecting both the ligand binding and pore forming domains (Bouzat et al., 2004; Lummis et al., 2005).

While one effect of incorporating conformational rigidity into the structure of the bis-azaaromatc quaternary ammonium compounds will be to better define the relative spatial positions of the two head groups, alternatively, the linkers themselves may also contribute to the biological activity of the compounds. TMPH is a very potent and selective nAChR antagonist which contains a simple tetramethylpiperidine (TMP) head group attached to a long aliphatic chain. Although tetramethylpiperidine itself is a ganglionic blocker, the addition of the lipophilic aliphatic chain had the effect of significantly increasing the potency of TMPH compared to TMP (Papke et al., 1994).

Unfortunately, high resolution models of the membrane spanning and intracellular domains of neuronal nAChRs are not available; thus, future studies may have to rely on traditional site-directed mutations for further investigation of the significance of both the single residue differences and functional subdomains of the receptors. In the meantime, as demonstrated in the current study, the insertion of the several points of sequence divergence between α4 and α6 into the α4/6 chimera has made it a useful tool for the further development of agents which may selectively inhibit α6 receptors, and therefore ultimately prove useful as therapeutic agents for treating nicotine dependence.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grants DA 017548, GM57481, and MH53631. We thank Lisa B. Jacobs, Chad Brodbeck, Chris Coverdill, Adriane Argenio, Dolan Abu-Aouf, and Sara Braley for technical assistance and Drs. Nicole Horenstein, Michael Bardo and Paul Lockman for helpful comments. The University of Kentucky holds patents on the bis-azaaromatic quaternary ammonium compounds. A potential royalty stream to LPD and PAC may occur consistent with the University of Kentucky policy.

Abbreviations

- DHβE

dihydro-β-erythroidine

- bPiDDB

N,N’-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-picolinium dibromide

- bPiPyB

1,2-bis-[5-(3-picolinium]-pent-1-ynyl]-benzene dibromide

- bIQDDB

N,N’-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-isoquinolinium dibromide

- bIQPB

1,2-bis-(5-isoquinolinium-pentyl)-benzene dibromide

- bIQPyB

1,2-bis-(5-isoquinolinium-pent-1-ynyl)-benzene dibromide

- bPiBB

1,4-bis-[4-(3-picolinium)-butyl]-benzene dibromide

- bPiByB

1,4-bis-[4-(3-picolinium)-butyl-1-ynyl]-benzene dibromide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ayers JT, Dwoskin LP, Deaciuc AG, Grinevich VP, Zhu J, Crooks PA. bis-Azaaromatic quaternary ammonium analogues: ligands for alpha4beta2* and alpha7* subtypes of neuronal nicotinic receptors. Bioorganic Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2002;12(21):3067–3071. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00687-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam L, Chen Y, Leslie FM. Developmental regulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors within midbrain dopamine neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;144(4):1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam L, McIntosh JM. Characterization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that modulate nicotine-evoked [3H]norepinephrine release from mouse hippocampal synaptosomes. Molecular Pharmacology. 2006;70(3):967–976. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.024513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzat C, Gumilar F, Spitzmaul G, Wang HL, Rayes D, Hansen SB, Taylor P, Sine SM. Coupling of agonist binding to channel gating in an ACh-binding protein linked to an ion channel. Nature. 2004;430(7002):896–900. doi: 10.1038/nature02753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpantier E, Barneoud P, Moser P, Besnard F, Sgard F. Nicotinic acetylcholine subunit mRNA expression in dopaminergic neurons of the rat substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area. Neuroreport. 1998;9(13):3097–3101. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199809140-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Noriega LE, Crona JH, Washburn MS, Urrutia A, Elliott KJ, Johnson EC. Pharmacological characterization of recombinant human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors h alpha 2 beta 2, h alpha 2 beta 4, h alpha 3 beta 2, h alpha 3 beta 4, h alpha 4 beta 2, h alpha 4 beta 4 and h alpha 7 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experiment Therapeutics. 1997;280(1):346–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PBS, Schwartz RD, Paul SM, Pert CB, Pert A. Nicotinic binding in rat brain: autoradiographic comparison of [3H] acetylcholine [3H] nicotine and [125I]-alpha-bungarotoxin. Journal of Neuroscience. 1985;5:1307–1315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-05-01307.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Erausquin M, Marubio LM, Klink R, Changeux JP. Nicotinic receptor function: new perspectives from knockout mice. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2000;21(6):211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks PA, Ayers JT, Xu R, Sumithran SP, Grinevich VP, Wilkins LH, Deaciuc AG, Allen DD, Dwoskin LP. Development of subtype-selective ligands as antagonists at nicotinic receptors mediating nicotine-evoked dopamine release. Bioorganic Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2004;14(8):1869–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.10.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damaj MI, Wiley JL, Martin BR, Papke RL. In vivo characterization of a novel inhibitor of CNS nicotinic receptors. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2005;521(1–3):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell C, Olivera BM, Garrett JE, Staheli ST, Watkins M, Kuryatov A, Yoshikami D, Lindstrom JM, McIntosh JM. Alpha-conotoxin PIA is selective for alpha6 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(24):8445–8452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-24-08445.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwoskin LP, Sumithran SP, Zhu J, Deaciuc AG, Ayers JT, Crooks PA. Subtype-selective nicotinic receptor antagonists: potential as tobacco use cessation agents. Bioorganic Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2004;14(8):1863–1867. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans NM, Bose S, Benedetti G, Zwart R, Pearson KH, McPhie GI, Craig PJ, Benton JP, Volsen SG, Sher E, Broad LM. Expression and functional characterisation of a human chimeric nicotinic receptor with alpha6beta4 properties. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2003;466(1–2):31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis MM, Choi KI, Horenstein BA, Papke RL. Sensitivity to voltage-independent inhibition determined by pore-lining region of ACh receptor. Biophysical Journal. 74 May;:2306–2317. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77940-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerzanich V, Wang F, Kuryatov A, Lindstrom J. alpha 5 Subunit alters desensitization, pharmacology, Ca++ permeability and Ca++ modulation of human neuronal alpha 3 nicotinic receptors. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;286(1):311–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldner FM, Dineley KT, Patrick JW. Immunohistochemical localization of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha6 to dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area. Neuroreport. 1997;8(12):2739–2742. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199708180-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Zoli M, Clementi F. Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: native subtypes and their relevance. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2006;27(9):482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryatov A, Olale F, Cooper J, Choi C, Lindstrom J. Human alpha6 AChR subtypes: subunit composition, assembly, and pharmacological responses. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(13):2570–2590. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Novere N, Zoli M, Changeux JP. Neuronal nicotinic receptor alpha 6 subunit mRNA is selectively concentrated in catecholaminergic nuclei of the rat brain. European Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;8(11):2428–2439. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luetje CW, Patrick J. Both α- and β-subunits contribute to the agonist sensitivity of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11(3):837–845. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-03-00837.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lummis SC, Beene DL, Lee LW, Lester HA, Broadhurst RW, Dougherty DA. Cistrans isomerization at a proline opens the pore of a neurotransmitter-gated ion channel. Nature. 2005;438(7065):248–252. doi: 10.1038/nature04130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh JM, Azam L, Staheli S, Dowell C, Lindstrom JM, Kuryatov A, Garrett JE, Marks MJ, Whiteaker P. Analogs of alpha-conotoxin MII are selective for alpha6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;65(4):944–952. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.4.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C. Genetic manipulation of ion channels: a new approach to structure and mechanism. Neuron. 1989;2(3):1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nai Q, McIntosh JM, Margiotta JF. Relating neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes defined by subunit composition and channel function. Molecular Pharmacology. 2003;63(2):311–324. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Choi CH, Zhou Y, Lindstrom J. Alternate stoichiometries of alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 2003;63(2):332–341. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer NM, Zhang Z, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP, Bardo MT. Effect of a novel nicotinic receptor antagonist, N,N'-dodecane-1,12-diyl-bis-3-picolinium dibromide, on nicotine self-administration and hyperactivity in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184(3–4):426–434. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olincy A, Harris JG, Johnson LL, Pender V, Kongs S, Allensworth D, Ellis J, Zerbe GO, Leonard S, Stevens KE, Stevens JO, Martin L, Adler LE, Soti F, Kem WR, Freedman R. Proof-of-concept trial of an alpha7 nicotinic agonist in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(6):630–638. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma E, Maggi L, Miledi R, Eusebi F. Effects of Zn2+ on wild and mutant neuronal alpha7 nicotinic receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, U. S. A. 1998;95(17):10246–10250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Buhr JD, Francis MM, Choi KI, Thinschmidt JS, Horenstein NA. The effects of subunit composition on the inhibition of nicotinic receptors by the amphipathic blocker 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-4-yl heptanoate. Molecular Pharmacology. 2005;67(6):1977–1990. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Craig AG, Heinemann SF. Inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by BTMPS, (Tinuvin® 770), an additive to medical plastics. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994;268:718–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. The pharmacological activity of nicotine and nornicotine on nAChRs subtypes: relevance to nicotine dependence and drug discovery. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2007;101(1):160–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Horenstein BA, Placzek AN. Inhibition of wild-type and mutant neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by local anesthetics. Molecular Pharmacology. 2001a;60(6):1–10. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.6.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Oswald RE. Mechanisms of noncompetitive inhibition of acetylcholine-induced single channel currents. Journal of General Physiology. 1989;93:785–811. doi: 10.1085/jgp.93.5.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Papke JKP. Comparative pharmacology of rat and human alpha7 nAChR conducted with net charge analysis. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;137(1):49–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Sanberg PR, Shytle RD. Analysis of mecamylamine stereoisomers on human nicotinic receptor subtypes. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001b;297(2):646–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts LA, Garwood CL. Varenicline: the newest agent for smoking cessation. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2007;64(13):1381–1384. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press WH. Numerical Recipies in C: The art of Scientific Computing. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman S, Zhang Z, Papke RL, Crooks PA, Dwoskin LP, Bardo MT. Region-specific effects of bPiDDB on in vivo nicotine-induced increase in extracellular dopamine. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2008 doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707612. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J, Levin E, Behm F, Westman E, Stein R, Lane J, Ripka G. Concurrent mecamylamine/nicotine administration. In: Clarke PBS, Quik M, Thurau K, Adlkofer F, editors. International Symposium on Nicotine: The Effects of Nicotine on Biological Systems II. Montreal, Canada: Birkhauser Verlag; 1994a. p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Behm FM, Westman EC, Levin ED, Stein RM, Ripka GV. Mecamylamine combined with nicotine skin patch facilitates smoking cessation beyond nicotine patch treatment alone. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1994b;56(1):86–99. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Drapeau JA, McIntosh JM, Collins AC, Marks MJ, Grady SR. Pharmacology of alpha-conotoxin MII-sensitive subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors isolated by breeding of null mutant mice. 2007;71(6):1563–1571. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.031492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen O, Murphy KL, McIntosh JM, Drago J, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Grady SR. Subunit composition and pharmacology of two classes of striatal presynaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors mediating dopamine release in mice. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;65(6):1526–1535. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.6.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanberg PR, Shytle RD, Silver AA. Treatment of Tourette’s syndrome with mecamylamine. Lancet. 1998;352:705–706. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60822-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes C, Papke JKP, McCormack T, Kem WR, Horenstein NA, Papke RL. The structural basis for drug selectivity between human and rat nicotinic alpha7 receptors. Molecular Pharmacology. 2004;66(1):14–24. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone C, Torchiana M, Navarro A, Beyer K. Ganglionic blocking properties of 3-methyl-aminoisocamphane hydrochloride (mecamylamine): a secondary amine. Journal of Pharmacology and Experiemntal Therapeutics. 1956;117:169–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JC, Francis MM, Porter JK, Robinson G, Stokes C, Horenstein B, Papke RL. Antagonist activities of mecamylamine and nicotine show reciprocal dependence on beta subunit sequence in the second transmembrane domain. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;127:1337–1348. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Verlinden MH, Adler LA, Wozniak PJ, West SA. ABT-089, a neuronal nicotinic receptor partial agonist, for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: results of a pilot study. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59(11):1065–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Sumithran SP, Deaciuc AG, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. tris-Azaaromatic quaternary ammonium salts: Novel templates as antagonists at nicotinic receptors mediating nicotine-evoked dopamine release. Bioorganic Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2007;17(24):6701–6706. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoli M, Moretti M, Zanardi A, McIntosh JM, Clementi F, Gotti C. Identification of the nicotinic receptor subtypes expressed on dopaminergic terminals in the rat striatum. Journal of Neuroscience. 2002;22(20):8785–8789. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-20-08785.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]