Abstract

Hyperinsulinemia plays a major role in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. Restenosis occurs at an accelerated rate in hyperinsulinemia and is dependent on increased vascular smooth muscle cell movement from media to neointima. PDGF plays a critical role in mediating neointima formation in models of vascular injury. We have reported that PDGF increases the levels of protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B and that PTP1B suppresses PDGF-induced motility in cultured cells and that it attenuates neointima formation in injured carotid arteries. Others have reported that insulin enhances the mitogenic and motogenic effects of PDGF in cultured smooth muscle cells and that hyperinsulinemia promotes vascular remodeling. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that insulin amplifies PDGF-induced cell motility by suppressing the expression and function of PTP1B. We found that chronic but not acute treatment of cells with insulin enhances PDGF-induced motility in differentiated cultured primary rat aortic smooth muscle cells and that it suppresses PDGF-induced upregulation of PTP1B protein. Moreover, insulin suppresses PDGF-induced upregulation of PTP1B mRNA levels, PTP1B enzyme activity, and binding of PTP1B to the PDGF receptor-β, and it enhances PDGF-induced PDGF receptor phosphotyrosylation. Treatment with insulin induces time-dependent upregulation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase)-δ and activation of Akt, an enzyme downstream of PI3-kinase. Finally, inhibition of PI3-kinase activity, or its function, by pharmacological or genetic means rescues PTP1B activity in insulin-treated cells. These observations uncover novel mechanisms that explain how insulin amplifies the motogenic capacity of the pivotal growth factor PDGF.

Keywords: vascular pathology, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-δ, Akt, primary culture

type 2 diabetes, involving hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia, is strongly associated with the occurrence of atherosclerosis in experimental models (57). Restenosis, an event dependent on neointimal enlargement, occurs frequently after coronary angioplasty, especially in humans manifesting insulin resistance (32). Moreover, plasma insulin levels in the U.S. population have reportedly increased by ∼35% during the last decade (35).

Several studies (2, 11, 52, 56, 62) have reported that chronic hyperinsulinemia, even in absence of hyperglycemia, constitutes an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and restenosis in humans. A recent study (26) found that chronically elevated insulin levels may be more important for induction of experimental neointima than elevated glucose levels. Indeed, hyperglycemia alone has been reported to decrease vascular smooth muscle proliferation (9, 51) and neointima formation in vascular injury (26).

PDGF is thought to be a pivotal mediator of neointimal enlargement that occurs in experimental vascular injury on the basis of reports (15, 16, 34, 38, 61) indicating that treatment with PDGF antagonists, or the use of agents that decrease endogenous PDGF levels, attenuates neointimal enlargement and that treatment with PDGF enhances the formation of neointima (28). Moreover, PDGF mRNA levels have been reported to be increased in human atherosclerotic plaques (58), and the PDGF receptor (PDGFR) is upregulated in vascular injury (1, 44).

PDGF appears to enhance neointima formation by stimulating vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation as well as migration from media to neointima (38). Tyrosyl phosphorylation of PDGFR is thought to be an obligatory event for activation of PDGF-induced signaling in cultured cells (24, 33). Furthermore, balloon injury, or treatment in vivo with PDGF, induces PDGFR tyrosyl phosphorylation in vascular smooth muscle (1, 38, 60), a finding consistent with observations in vitro. Studies (13, 18, 39, 47, 49) have reported that PDGFR-β but not PDGFR-α mediates neointimal expansion in rodents and nonhuman primates. We recently reported that PDGF, among several other polypeptide growth factors, induces upregulation of PTP protein levels, including that of PTP1B (6) and that PTP1B then targets the PDGFR, inducing tyrosyl dephosphorylation of the receptor, followed by attenuation of cell proliferation and motility (5).

Insulin and PDGF appear to interact functionally in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Thus acute treatment with insulin attenuates PDGF-induced cell motility (27), whereas prolonged treatment enhances the mitogenic effectiveness of PDGF (19, 59). We have reported that treatment of differentiated cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells with PDGF, or induction of vascular injury in rat carotid arteries, elicits upregulation of the protein levels of nonreceptor protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP1B (6) and that PTP1B, in turn, attenuates PDGF-induced cell motility and that it appears to play a counter-regulatory role in vivo by suppressing injury-induced neointima formation in rat carotid arteries (5).

The aim of the present study was to test the overall hypothesis that chronic insulin treatment of differentiated cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells attenuates the counter-regulatory effectiveness of PTP1B directed against PDGF by decreasing the expression and function of the tyrosine phosphatase, thereby amplifying the motogenic effect of PDGF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The studies were performed via a protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Department of Health and Human Services, NIH Publication No. 86-23, Revised 1996).

Materials.

Male rats of the Sprague-Dawley strain were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Primaria tissue culture plates were from Falcon/Becton-Dickinson (Oxnard, CA); DMEM and DMEM:Ham's F-12 (1:1) medium were from Cellgro Mediatech (Herndon, VA); porcine pancreatic elastase and clostridium histolyticum collagenase were from Worthington Biochemical (Lakewood, NJ); soybean trypsin inhibitor, FBS, and BSA (fraction V) were from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA); bovine pancreatic insulin, protease inhibitor cocktail, isotype control mouse IgG2a, and p-nitrophenyl phosphate were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); phosphatase inhibitor cocktail set I was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA); recombinant human PDGF-BB was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); LY294002 was from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA); wortmannin was from Biosource (Camarillo, CA); purified mouse anti-PTP1B monoclonal antibody was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA); antibody directed against p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) was from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY); protein G-Sepharose beads were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotechnology (Piscataway, NJ); goat polyclonal antibody against PDGFR-β and goat polyclonal phospho-specific antibody against PDGFR β (Y770) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); and antibodies against PI3-kinase p110 subunits (α, β, γ, and δ) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Replication deficient (E1-deleted) recombinant type 5 adenovirus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein, human sequence wild-type PTP1B, or dominant negative PTP1B (C215S-PTP1B) were prepared as described previously (50). Adenovirus expressing the mutated PI3-kinase adapter protein Δp85 was generously donated by Barry I. Posner (McGill University, Montreal, Canada). The deletion mutant of mutated p85 (Δ478–513) lacks the binding site for the catalytic unit p110 and has been demonstrated to function in dominant negative manner in cultured cells (31). It should also be noted that we have previously found that treatment with adenovirus at multiplicity of infection (MOI) values used in the present study does not induce cytotoxicity, as determined by the lack of trypan blue staining (data not shown).

Performance of cell culture.

Vascular smooth muscle cells were isolated from thoracic aortas of Sprague-Dawley rats (weighing 100–120 g) and cultured in a manner that minimizes cellular dedifferentiation, as we have previously reported (3, 22). All experiments in the present study were performed using primary and confluent cultures that were serum starved for 24–48 h before experiments. Moreover, each individual experiment represents results from one such independent cell isolate.

Performance of Western blot analysis.

To determine the levels of tyrosyl phosphorylated PDGFR-β, cells were subjected to lysis using RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% SDS, and 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.2), supplemented with 2 mM sodium vanadate, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.4 μM aprotinin, 10.5 μM leupeptin, 18 μM bestatin, 7.5 μM pepstatin A, and 7 μM E-64. Blots were probed using phospho-specific antibodies directed against phosphotyrosyl residue 770 in the PDGFR-β. After being blotted for Y770 phosphotyrosyl levels, blots were stripped and reprobed with antibody directed against PDGFR-β protein.

To determine PTP1B protein levels by direct Western blot analysis, cells were subjected to lysis using the following buffer: 188 mM Tris·HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 15% glycerol, and 3% SDS, pH 6.8, further supplemented with 1 mM sodium vanadate, 0.25 mM PMSF, 0.2 μM aprotinin, 5.25 μM leupeptin, 9 μM bestatin, 3.75 μM pepstatin A, and 3.5 μM E-64. Lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis, and band densities were measured by using National Institutes of Health Image software.

Measurement of cell motility.

Aortic smooth muscle cell motility was measured by way of a monolayer wounded-culture assay via the use of National Institutes of Health Image 1.62 software, involving migration of cells into the breach, as described in detail in previous publications (4, 12, 50, 63). Motility experiments were performed in the presence of 5 mM hydroxyurea to prevent cell proliferation, as described previously (4). The motility index was expressed as distance migrated in 24 h.

Measurement of PTP1B mRNA levels via semiquantitative real-time PCR.

Cells were pretreated with 100 nM insulin for 48 h and then treated without or with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB for 8 h (in the continued absence or presence of insulin), followed by isolation of total RNA via a commercial kit (Aurum, total RNA sample pack) from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). Messenger RNA was transcribed into cDNA via Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit from Roche (Indianapolis, IN), followed by performance of real-time PCR for PTP1B or cyclophilin mRNA levels, using an LC 480 Real-Time PCR instrument (Roche Diagnostics). Cyclophilin was chosen to normalize mRNA levels on the basis of published work (14, 54). Real-time PCR was performed by using the following probes, derived via the Universal probe library software (universalprobelibrary.com; Roche Applied Science): PTP1B sense primer: GGAACAGGTACCGAGATGTCA (residues 247-267); PTP1B antisense primer: AGTCATTATCTTCCTGATGCAATTT (residues 291-315); cyclophilin sense primer: ACCTTCCACAGGGTCATCC (residues 306-324); and cyclophilin antisense primer: ACCTTCCACAGGGTCATCC (residues 306-324).

Measurement of PTP1B activity.

Confluent aortic smooth muscle cells were exposed for 24 h to adenovirus expressing PTP1B (at MOI of 10 to 15), followed by rinsing to remove residual virus and further incubation for 48 h in the absence or presence of 100 nM insulin. Cells were then subjected to lysis using ice-cold HEPES buffer of the following composition: 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (0.5 mM PMSF, 0.4 μM aprotinin, 10.5 μM leupeptin, 18 μM bestatin, 7.5 μM pepstatin A, and 7 μM E-64) and serine/threonine phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (25 μM p-bromotetramisole oxalate, 5 μM cantharidin, and 5 nM microcystin). PTP1B was immunoprecipitated using anti-PTP1B for 3 h at 4°C, followed by incubation of immunocomplexes with protein G-Sepharose beads (50%) for 2 h at 4°C, followed by rinsing twice with ice-cold HEPES buffer (25 mM HEPES, 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM DTT and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.2). To measure enzyme activity, immunoprecipitated PTP1B was incubated with 10 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate as substrate for 10 min at 37°C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 10 M NaOH followed by measurement of enzyme activity via the increase of absorbance at 405 nm, due to the generation of p-nitrophenol by enzymatic hydrolysis. The specificity of this method was verified in a previous study in which we showed that at least 80% of the immunoprecipitated phosphatase activity corresponds with PTP1B, as determined via an in-gel phosphatase assay (23).

Coimmunoprecipitation of PDGFR-β and catalytically inactive PTP1B.

Cells were infected with control adenovirus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein or with adenovirus expressing catalytically inactive PTP1B (C215S-PTP1B) at MOI values of 10–15 in the absence or presence of 100 nM insulin for 48 h. Cells were then rinsed to remove residual virus, followed by incubation for 24 h, in the continued absence or presence of 100 nM insulin. Cells were then subjected to lysis using RIPA buffer of the following composition: 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% SDS, and 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.2, further supplemented with 2 mM sodium vanadate, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.4 μM aprotinin, 10.5 μM leupeptin, 18 μM bestatin, 7.5 μM pepstatin A, and 7 μM E-64, and the lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-PTP1B or nonspecific IgG as control. Coimmunoprecipitated PDGFR-β levels were measured by Western blot analysis by using anti-PDGFR-β, whereas PTP1B protein levels were measured by using anti-PTP1B.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses of multiple comparisons were performed by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's protected least significant difference test. Single comparisons were performed via unpaired Student's t-test. Statistical significance was assumed for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Insulin suppresses PDGF-induced PTP1B expression and amplifies PDGF-induced cell motility.

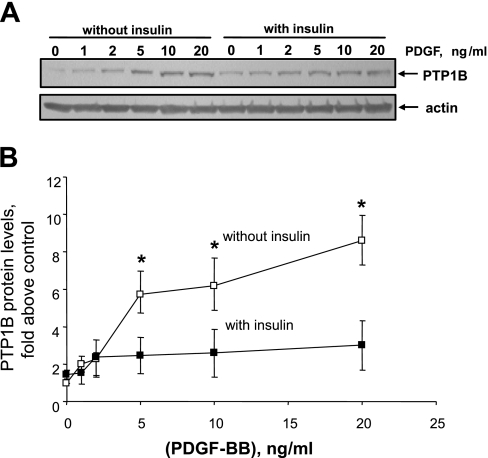

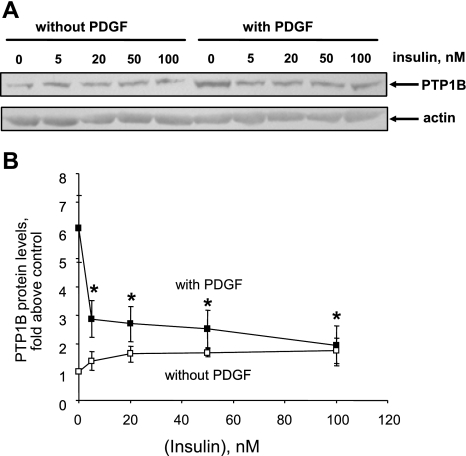

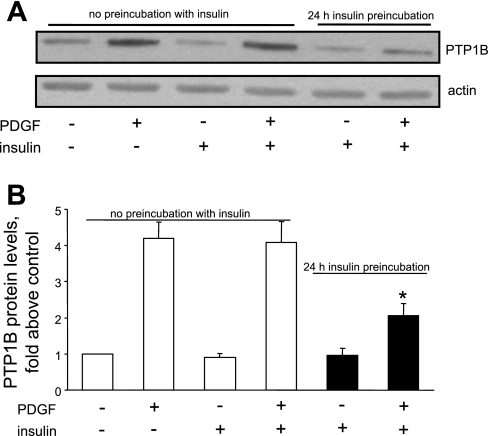

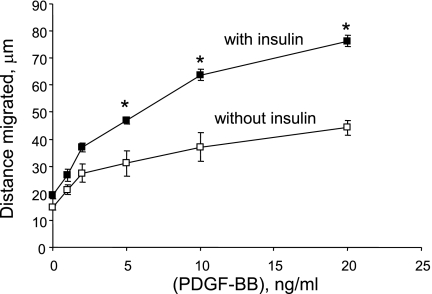

Publications (27, 29) have reported that acute treatment with insulin attenuates PDGF-induced smooth muscle cell motility or proliferation, whereas other reports (19, 59) indicate that prolonged treatment with insulin enhances the mitogenic effect of PDGF. We have reported that PDGF increases PTP1B protein levels (6), that ectopic overexpression of PTP1B attenuates PDGF-induced motility in cultured smooth muscle cells (5), that vascular injury increases PTP1B levels (6), and that expression of dominant-negative PTP1B enhances neointima formation in injured rat carotid arteries (5). These studies support the existence of a negative regulatory feedback loop involving PTP1B, downstream of PDGFR activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. The purpose of the present study was to determine if pretreatment of cells with insulin would suppress PDGF-induced upregulation of PTP1B function, which would provide a mechanism that would explain amplification of PDGF-induced cell motility by insulin. We used highly differentiated primary cultured aortic smooth muscle cells obtained from adult rats to mimic the differentiation state of medial cells in blood vessels as closely as possible. As shown in Fig. 1, pretreatment of cells for 48 h with 100 nM insulin virtually abrogated the increase of PTP1B protein levels induced by PDGF. Data given in Fig. 2 show that treatment of cells with insulin at a concentration as low as 5 nM (with change of culture media twice a day to attenuate insulin degradation) also yielded virtually complete suppression of PDGF-induced PTP1B upregulation. Data provided in Fig. 3 indicate that the suppressive effect of insulin fails to occur without preincubation with insulin, indicating that chronic but not acute treatment has the capacity to suppress PDGF-induced elevation of PTP1B levels. Data shown in Fig. 4 represent the functional correlate of biochemical experiments presented in Fig. 1 and indicate that pretreatment with insulin for 48 h enhances the motogenic effect of PDGF in cultured smooth muscle cells. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 5, this effect occurs at an insulin concentration as low as 5 nM. To determine whether prolonged pretreatment with insulin would be required for the comotogenic effect of insulin, we preincubated cells with insulin for periods ranging from 0 to 48 h and found that preexposure to insulin for 24 to 48 h is required for manifestation of the comotogenic effect (Fig. 6).

Fig. 1.

Pretreatment with insulin suppresses PDGF-induced upregulation of PTP1B protein levels. Cells were preincubated without or with 100 nM insulin for 48 h and then treated with a range of PDGF-BB concentrations for 24 h in the continued absence or presence of 100 nM of insulin. PTP1B and actin protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis. A: results of a representative Western blot. B: means ± SE of 3 experiments. Data are expressed as the ratio of PTP1B to actin protein levels, further normalized to values from the control treatment category. *P < 0.05, compared with values obtained in presence of insulin by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's protected least significant difference test (PLSD).

Fig. 2.

Suppression of PDGF-induced PTP1B upregulation by near pathophysiological levels of insulin. Cells were preincubated without or with indicated insulin concentrations for 48 h and then treated with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB for 24 h in the continued absence or presence of insulin. Culture media were replaced twice a day to attenuate the potential effect of insulin degradation. PTP1B and actin protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis. A: representative Western blot. B: summary of 4 experiments (means ± SE). *P < 0.05, compared with values from cells treated with PDGF in absence of insulin by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's PLSD.

Fig. 3.

Suppression of PTP1B levels requires preincubation with insulin. Cells were preincubated without or with 100 nM insulin for 24 h and then treated for 24 h without or with 20 ng/ml PDGF in the continued absence or presence of 100 nM insulin. PTP1B protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis (A). Results are means ± SE of 3 independent experiments (B). *P < 0.05, compared with PDGF treatment category by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's PLSD test.

Fig. 4.

Pretreatment with insulin enhances PDGF-induced cell motility. Cells were preincubated for 48 h without or with 100 nM insulin followed by treatment for 24 h with a range of PDGF concentrations in the continued absence or presence of 100 nM of insulin. Cell motility was measured by using National Institutes of Health Image software. Results are means ± SE of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with “no insulin” treatment category at the same concentration of PDGF by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's PLSD test.

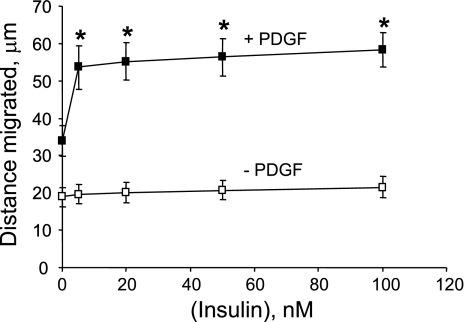

Fig. 5.

Enhancement of PDGF-induced cell motility by near pathophysiological levels of insulin. Cells were preincubated for 48 h in the absence or presence of a range of insulin concentrations, followed by treatment for 24 h with 20 ng/ml PDGF in the continued absence or presence of insulin. Culture media were replaced twice a day to attenuate the potential effect of insulin degradation. Cell motility was measured by using National Institutes of Health Image software. Results are means ± SE of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with “zero insulin plus PDGF” treatment category by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's PLSD test.

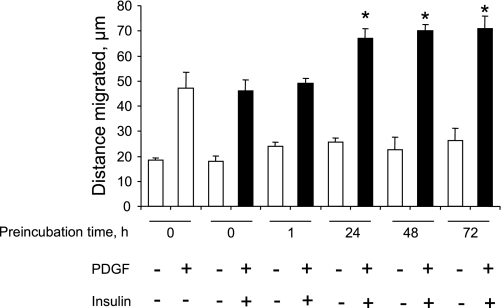

Fig. 6.

Enhancement of PDGF-induced motility by insulin requires prolonged preincubation with insulin. Cells were preincubated without or with 100 M insulin for 0, 1, 24, 48, or 72 h and then treated without or with PDGF (20 ng/ml) in the continued presence or absence of insulin for 24 h. Results are means ± SE of 3 experiments. *P < 0.001, compared with PDGF treatment in absence of preincubation by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's test.

Pretreatment with insulin suppresses PDGF-induced elevation of PTP1B mRNA levels.

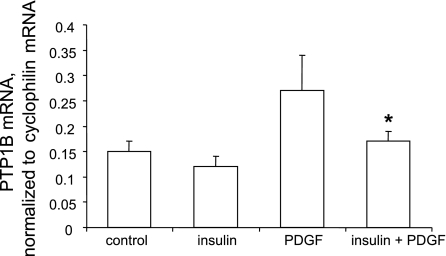

Our next experiments were performed to identify a mechanism that might explain the suppression of PTP1B protein expression by insulin. Accordingly, we tested the hypothesis that pretreatment with insulin would suppress the capacity of PDGF to induce upregulation of PTP1B mRNA levels. We first determined the time course of PDGF-induced elevation of PTP1B mRNA levels and found that a 2- to 8-h time period optimally induced a 1.5- to 2-fold increase (data not shown). We then measured PTP1B mRNA levels via semiquantitative RT-PCR in cells pretreated without or with insulin and subsequently treated without or with PDGF in the continued absence or presence of insulin. As shown in Fig. 7, treatment of cells with PDGF for 8 h induced a significant increase of PTP1B mRNA levels. Moreover, pretreatment of cells with insulin for 48 h abrogated the capacity of PDGF to induce upregulation of PTP1B mRNA levels.

Fig. 7.

Pretreatment with insulin suppresses PDGF-induced PTP1B mRNA elevation. Cells were treated without or with 100 nM insulin for 48 h, followed by treatment without or with 20 ng/ml PDGF-BB for 8, in the continued absence or presence of insulin, followed by isolation of total RNA. After generation of cDNA by reverse transcription, mRNA levels were quantitated via real-time PCR. Messenger RNA levels for PTP1B were normalized to mRNA levels of cyclophilin and are means ± SE of 6 experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with values from cells treated with PDGF in absence of insulin by Student's t-test.

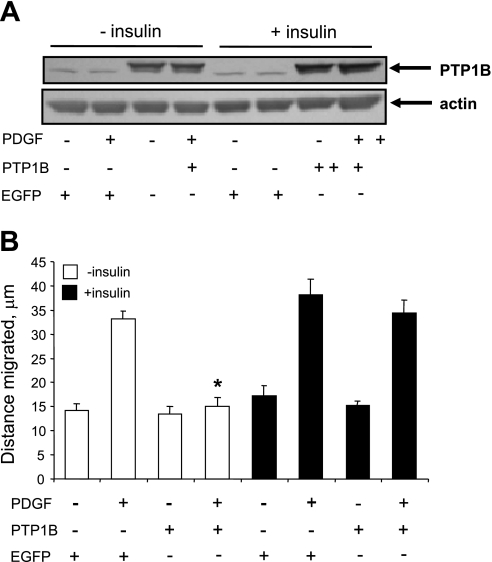

Insulin attenuates the anti-motogenic effect of ectopically expressed PTP1B.

We next tested the hypothesis that insulin would suppress the function of PTP1B in aortic smooth muscle cells, independently of its effect on PTP1B expression. To test this hypothesis, we induced ectopic expression of PTP1B via an adenoviral vector whereby expression of the enzyme was directed by the constitutively active cytomegalovirus enhancer/promoter, with the expectation that insulin would not have a significant effect on expression driven by this promoter. It should also be noted that we took care to perform these experiments using a relatively low concentration of PDGF (2 ng/ml) to avoid significant upregulation of endogenous PTP1B levels by PDGF.

As expected, insulin did not significantly alter the expression of ectopic PTP1B induced by infection with PTP1B-expressing adenovirus (Fig. 8A). As shown in Fig. 8B, treatment of cells with 2 ng/ml PDGF induced a twofold increase of cell motility. Moreover, overexpression of PTP1B blocked PDGF-induced motility in insulin-naïve cells, confirming earlier results from our laboratory (5). However, pretreatment of cells with 100 (Fig. 8) or 5 nM insulin (data not shown) rescued the motogenic effect of PDGF in PTP1B-treated cells, without significantly altering baseline motility. In this regard, it should also be noted that insulin treatment alone does not alter cell number, as we have previously reported (12).

Fig. 8.

Pretreatment with insulin suppresses the antimotogenic effect of ectopic PTP1B. Cells were treated for 24 h without or with 100 nM insulin and with control virus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) or with virus expressing PTP1B at multiplicity of infection values of 10–15. Cells were then rinsed to remove residual virus and further incubated for 48 h to allow time for PTP1B expression in the continued absence or presence of insulin. Cells were treated without or with 2 ng/ml PDGF-BB during the last 24 h of incubation. A: PTP1B levels as determined by Western blot analysis. The doublet of bands for PTP1B represents endogenous and ectopic PTP1B, the latter of which has a slightly greater mass than the endogenous protein, due to the addition of a hemagglutinin tag. B: effect of insulin on the capacity of ectopic PTP1B to suppress PDGF-induced cell motility. Results are means ± SE of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with “EGFP + PDGF” treatment category by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's PLSD.

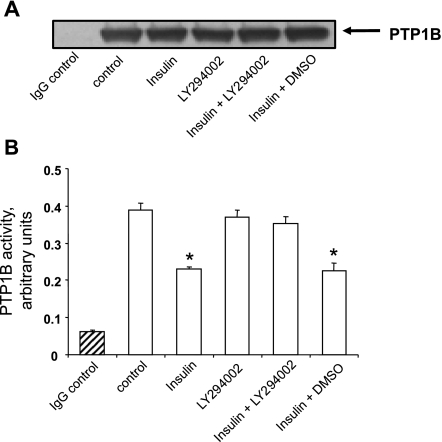

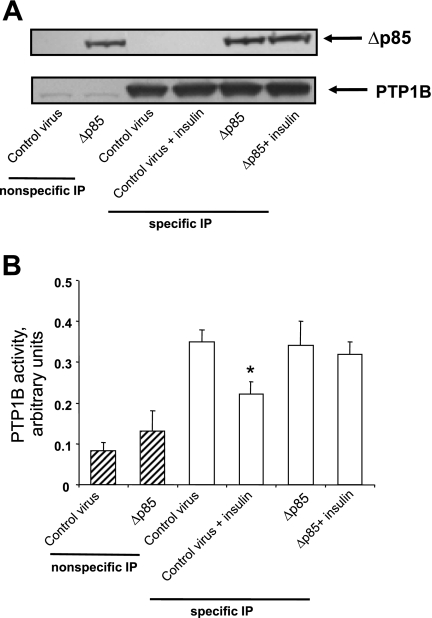

Insulin decreases the enzyme activity of ectopic or endogenous PTP1B.

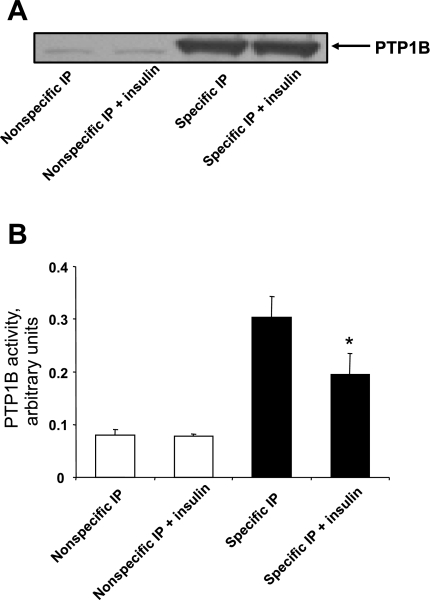

The aforementioned experiments are consistent with the notion that insulin may decrease the enzyme activity of PTP1B. However, the effect of insulin on PTP1B activity is controversial, with one study having reported increased enzyme activity, but several others having reported the opposite finding (8, 36, 37, 53). We therefore performed the next experiments to test the hypothesis that suppression of PTP1B function by insulin could be attributed, at least in part, to decreased enzyme activity. As shown in Fig. 9B, insulin induced a ∼50% decrease of ectopically expressed PTP1B activity, uncovering an additional mechanism by which insulin induces suppression of the counter-regulatory activity of PTP1B. These data are further supported by Fig. 9A, indicating specificity of immunoprecipitation as well as equivalency of immunoprecipitated PTP1B levels in different treatment categories.

Fig. 9.

Treatment with insulin decreases enzyme activity of ectopically expressed PTP1B. Cells were treated for 24 h with adenovirus expressing PTP1B, in absence or presence of 100 nM insulin. Cells were then rinsed and incubated for 48 h in the continued absence or presence of 100 nM insulin followed by lysis. PTP1B was immunoprecipitated (IP) using control IgG (open bars; nonspecific IP) or antibody directed against PTP1B (solid bars; specific IP) and immunoprecipitates were incubated with p-nitrophenyl phosphate as the substrate. A: results from a representative Western blot indicating specificity and equivalency of immunoprecipitation in different treatment categories. B: PTP1B activity as means ± SE of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with values from insulin-naïve cells subjected to specific immunoprecipitation by Student's t-test.

To verify the aforementioned findings in which we used ectopically expressed PTP1B, we also performed experiments to determine the effect of insulin on the enzyme activity of endogenous PTP1B. As shown in Fig. 10B, PDGF increased the activity of PTP1B, whereas insulin blocked the effect of PDGF. Insulin did not decrease baseline PTP1B activity, presumably due to the low levels of activity in cells not treated with PDGF. Data shown in Fig. 10A indicate equivalent levels of PTP1B in the specific immunoprecipitates, a result that was obtained by adding excess protein to immunobeads to induce equivalent immunoprecipitation in different treatment categories.

Fig. 10.

Pretreatment with insulin induces suppression of endogenous PTP1B enzyme activity in PDGF-treated cells. Cells were treated for 48 h without or with 100 nM insulin, followed by treatment without or with 20 ng/ml PDGF for 24 h, in the continued absence or presence of insulin. It should be noted that immunoprecipitation was performed using protein in excess, relative to protein G-Sepharose beads to allow equivalent immunoprecipitation of PTP1B in all treatment categories. A: results from a representative Western blot indicating specificity and equivalency of immunoprecipitation in different treatment categories. B: PTP1B activity as the means ± SE of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with values from insulin-naïve cells treated with PDGF followed by specific IP by Student's t-test.

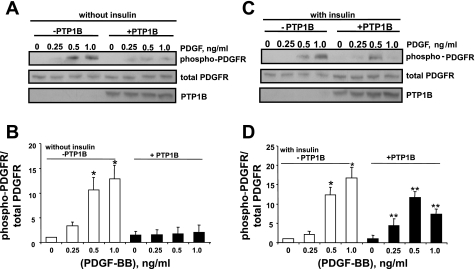

Insulin suppresses PTP1B-induced PDGFR-β phosphotyrosyl dephosphorylation.

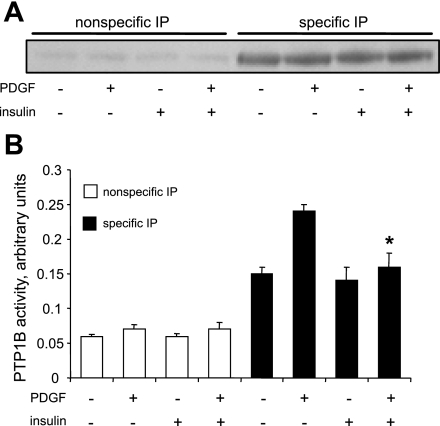

Recent publications (5, 20) have indicated that PTP1B has the capacity to decrease the levels of phosphotyrosyl in PDGFRs, an effect that is consistent with the antimotogenic influence of PTP1B directed against PDGF-induced motility. These findings prompted us to test the hypothesis that insulin would suppress PTP1B-induced phosphotyrosyl dephosphorylation of PDGFRs. As expected, treatment of control cells with PDGF-BB, at concentrations that do not elicit significant upregulation of endogenous PTP1B, induced a significant increase of phosphotyrosyl levels in residue Y770 of PDGFR-β in both the absence and presence of insulin (Fig. 11). Moreover, overexpression of PTP1B essentially abrogated PDGF-induced tyrosyl phosphorylation of PDGFR-β in insulin-naïve cells, confirming previous findings (Fig. 11, A and B). However, in cells that were pretreated with insulin, the capacity of PTP1B to decrease phosphotyrosyl levels of PDGFR-β was markedly attenuated compared with that in insulin-naïve cells (Fig. 11, C and D).

Fig. 11.

Pretreatment with insulin suppresses PTP1B-induced PDGFR-β phosphotyrosyl dephosphorylation. Cells were preincubated without (A and B) or with 100 nM insulin (C and D) for 48 h, followed by treatment with control adenovirus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein or adenovirus expressing PTP1B, for 24 h in the continued absence or presence of insulin, followed by treatment with a range of PDGF-BB concentrations for 10 min. Levels of phospho-PDGFR-β and total PDGFR-β were measured by sequential Western blot analyses using anti-phospho-PDGFR-β (Y770) and anti-PDGFR. A and C: results from representative Western blots. B and D: summary of 3 experiments expressed as means ± SE of the densitometric ratio of phospho-PDGFR-β to PDGFR-β levels, normalized to control values (no insulin treatment and no overexpression of PTP1B). A and B: results in insulin-naïve cells. C and D: results in cells treated with insulin. *P < 0.05, compared with values from cells treated with control virus. **P < 0.05, compared with values from cells treated with PTP1B-expressing adenovirus by analysis of variance, followed by Fisher's PLSD test.

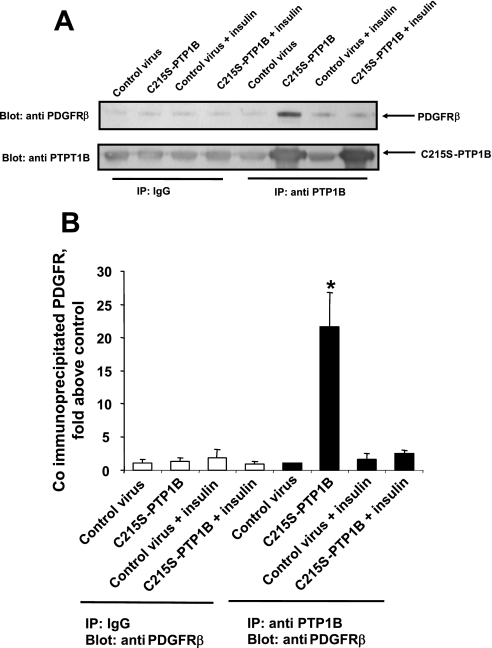

Insulin antagonizes the association of PTP1B with PDGFR-β.

The next experiments were performed to further probe the mechanism underlying insulin-induced inhibition of PTP1B function. We thus tested the hypothesis that insulin would attenuate the binding of PTP1B with its substrate, PDGFR-β. To perform this experiment, we used adenovirus expressing a substrate-trapping mutant of PTP1B, C215S-PTP1B, lacking catalytic activity, rather than wild-type PTP1B, on the basis of a report (17) indicating that wild-type PTP1B binds to substrates in a transient manner that is unlikely to be suitable for determination of interaction between enzyme and substrate in a biochemical assay, whereas catalytically inactive PTP1B has the capacity to bind substrate in stable manner. To implement this aim, we measured the extent of specific coimmunoprecipitation of PDGFR-β with C215S-PTP1B (the latter being expressed via an adenoviral vector) in protein lysates from cells treated without or with insulin. As depicted in Fig. 12, treatment of cells with insulin essentially abrogated the capacity of C215S-PTP1B to induce coimmunoprecipitation of PDGFR-β.

Fig. 12.

Pretreatment with insulin attenuates the binding of PTP1B and PDGFR-β. Cells were treated for 48 h without or with 100 nM insulin, followed by treatment for 24 h with control adenovirus expressing EGFP or adenovirus expressing catalytically inactive mutant PTP1B (C215S-PTP1B), in the continued absence or presence of insulin. Cells were then subjected to lysis and lysates were immunoprecipitated using nonspecific IgG as control (nonspecific IP) or anti-PTP1B (specific IP). Coimmunoprecipitated PDGFR-β levels were measured by Western blot analysis. A: results from a representative Western blot. B: means ± SE from 3 experiments, normalized to control values (specific IP, control virus). *P < 0.05, compared with values from cells treated with mutant virus plus insulin followed by specific IP by Student's t-test.

Treatment with insulin enhances PI3-kinase-δ levels in time-dependent manner.

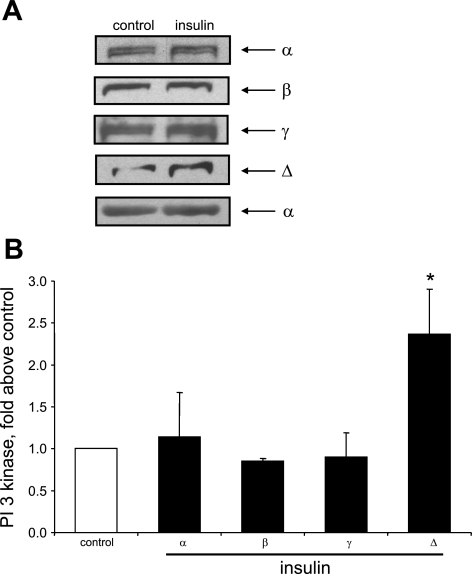

Several studies (40, 42, 43) have reported that hyperinsulinemia is associated with increased PI3-kinase activity in liver or skeletal muscle. Moreover, other recent studies found that hyperinsulinemia induces upregulation of PI3-kinase expression in rat aorta (55) and that PI3-kinase-δ levels are specifically upregulated in this model (30). These findings prompted us to investigate whether chronic, but not acute, insulin treatment would induce upregulation of PI3-kinase-δ in cultured primary aortic smooth muscle cells. As shown in Fig. 13, treatment of cells for 72 h with insulin increased the levels of PI3-kinase-δ but not the levels of PI3-kinase-α, -β, or -γ. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 14, PI3-kinase-δ levels increased in cells preincubated with insulin for 24 h to 72 h but not in cells not preincubated with insulin.

Fig. 13.

Chronic treatment with insulin induces specific upregulation of PI3-kinase-δ isoform. Cells were treated without or with 100 nM insulin for 72 h. PI3-kinase protein levels were measured by Western blot analysis, using specific antibody directed against p110 subunit. Results were normalized to control and are expressed as means ± SE of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with control by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's PLSD test.

Fig. 14.

Upregulation of PI3-kinase-δ requires chronic insulin treatment. Cells were treated without or with 5 or 100 nM insulin for 24, 48, or 72 h. PI3-kinase-δ levels were determined by Western blot analysis. Control represents 72 h incubation without insulin. Results were normalized to control and are means ± SE from 4 experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with control by ANOVA followed by Fisher's test.

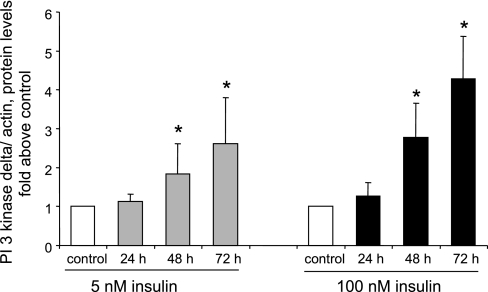

Insulin induces phosphorylation of Akt.

It is well established that PI3-kinase is a pivotal mediator of insulin signaling (48). On the basis of this and the aforementioned findings, we tested the hypothesis that the PI3-kinase pathway may be activated by insulin treatment in cultured smooth muscle cells, as manifested by phosphorylation of Akt on amino acid residue seryl 473, a well-accepted marker of Akt and PI3-kinase pathway activity (25). As shown in Fig. 15, insulin induced a marked increase of S473 phosphorylation level of Akt, indicative of PI3-kinase-Akt pathway activation.

Fig. 15.

Induction of Akt phosphorylation by insulin treatment. Cells were treated without or with 100 nM insulin for 72 h. Cell lysates were then subjected to Western blot analysis of phosphorylated Akt (S473) via the use of a phosphospecific antibody (A, top). A separate Western blot was performed to document equivalent levels of total Akt (A, middle) and equivalent actin levels among treatment categories (A, bottom). B: summary of means ± SE of 3 experiments, expressed as the ratio of phospho-Akt/total Akt. *P < 0.05, compared with control values by Student's t-test.

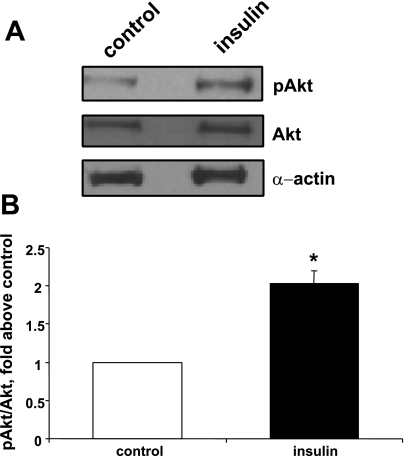

Attenuation of PI3-kinase activity/function via pharmacological or genetic means rescues the activity of PTP1B in insulin-treated cells.

The next experiments were designed to test the hypothesis that PI3-kinase activity is necessary for insulin-induced inhibition of PTP1B activity. For this purpose, we used two well-established and relatively selective pharmacological antagonists of PI3-kinase, namely LY294002 and wortmannin (10). As shown in Fig. 16, LY294002 rescued the activity of PTP1B in insulin-treated cells and similar results were obtained via the use of wortmannin (data not shown). To confirm these findings, we utilized a genetic approach via the use of an adenovirus expressing a deletion mutant of the p85 adaptor subunit (Δ478–513) of PI3-kinase, reported to act in dominant negative manner against endogenous PI3-kinase (31). Figure 17A indicates expression levels of ectopic dominant negative p85 subunit of PI3-kinase as well as immunoprecipitated PTP1B levels. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 17B, treatment of cells with adenovirus expressing dominant negative p85 regulatory subunit rescued insulin-suppressed PTP1B activity, supporting the results obtained via the use of pharmacological PI3-kinase antagonists.

Fig. 16.

PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 rescues PTP1B activity in insulin-treated cells. Cells were treated for 24 h with adenovirus expressing PTP1B and for 48 h without or with 100 nM insulin and without or with 20 μM LY294002 (delivered in DMSO). A: expression of PTP1B levels as determined by Western blot analysis. B: PTP1B activity as measured by immunophosphatase assay. Results are means ± SE of 3 experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with control by ANOVA, followed by Fisher's PLSD test.

Fig. 17.

Dominant-negative p85 regulatory subunit of PI3-kinase rescues PTP1B activity in insulin-treated cells. Cells were treated for 24 h with adenovirus expressing PTP1B, followed by infection with control adenovirus expressing EGFP or with adenovirus expressing dominant negative p85 (deletion mutant) adapter subunit (Δp85) for 48 h at MOI of 10–15. A: representative Western blot for expression levels of Δp85 (top) as well as PTP1B levels in immunoprecipitation experiments. B: summary of means ± SE of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05, compared with control virus treatment, followed by specific IP, by Student's t-test.

DISCUSSION

Hyperinsulinemia is a well-established factor for the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (2, 11, 52, 56). Moreover, several studies (15, 21, 34, 38, 61) have reported that PDGF plays a major role in vascular remodeling that occurs in response to injury by activating the PDGFR-β isoform. Studies (44) have reported that PDGFR-β expression and phosphorylation are markedly increased during the peak of vascular smooth muscle cell migration into the neointima. In the present study, we report the novel findings that pretreatment of differentiated cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells with insulin enhances PDGF-induced motility by decreasing the counter-regulatory effectiveness of PTP1B against the PDGFR via two distinct mechanisms: suppression of PTP1B mRNA and protein levels and decrease of PTP1B enzyme activity, the latter via a mechanism dependent on PI3-kinase function. Both functional and biochemical effects of insulin require chronic treatment, and they are manifested at a concentration of insulin as low as 5 nM, indicating that these effects are likely to be mediated via the insulin receptor, rather than the IGF-I receptor.

We reached our conclusions on the basis of findings indicating that pretreatment with insulin suppresses the capacity of PDGF to induce upregulation of PTP1B mRNA and protein levels. Furthermore, we found that insulin decreases PTP1B activity and that it attenuates substrate recognition by the enzyme, together with upregulation of Akt activity, indicating PI3-kinase activation. Activation of PI3-kinase by insulin is consistent with studies reporting association of hyperinsulinemia and increased PI3-kinase activity in rat liver and skeletal muscle (41–43). Moreover, recent studies (55) reported that hyperinsulinemia induced by insulin infusion induces specific upregulation of PI3-kinase-δ in rat aorta. We have now verified upregulation of PI3-kinase-δ, also confirming that PI3-kinase-α, -β, or -γ are not upregulated, and we find that this event occurs in time-dependent manner, implicating the δ-isoform in mediating the effect of chronic insulin treatment. These results are further supported by findings that pharmacological inhibitors of PI3-kinase, as well as a dominant negative allele of p85 targeted against PI3-kinase function, oppose insulin-induced attenuation of PTP1B activity.

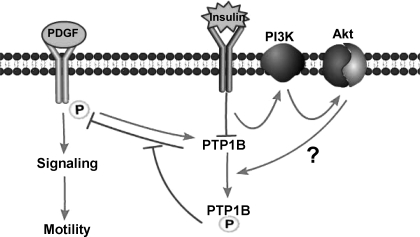

Mechanism(s) mediating insulin-induced attenuation of PTP1B activity downstream of PI3-kinase have not yet been fully elucidated. However, we speculate that they may involve activation of Akt, followed by seryl phosphorylation of PTP1B, on the basis of our findings of Akt activation and a report (46) from another laboratory indicating that activated Akt induces seryl phosphorylation of PTP1B, leading to decreased PTP1B enzyme activity. A second potential mechanism that might explain suppression of PTP1B activity would be hydrogen peroxide-mediated oxidation of the catalytically essential cysteine residue in the active site of the enzyme, as has been reported to occur in a transient manner by several groups (36, 37). Although our data do not rule out redox regulation of PTP1B by long-term insulin treatment, the fact that the catalytic activity of PTP1B was found to be decreased in assays containing sulfhydryl agents (a treatment that would be expected to rescue reduced activity induced by oxidation of catalytic cysteine residue) and the finding that insulin treatment blocks the association of a mutant of PTP1B lacking the catalytic cysteine with the PDGFR indicate the existence of a novel, redox-independent, mechanism that can explain reduced PTP1B catalytic activity. These findings support a mechanism outlined in Fig. 18, summarizing the effects of insulin treatment on the signaling and function of PDGF via suppression of PTP1B.

Fig. 18.

Schematic representation of interactions among PDGF, insulin, and PTP1B-mediated pathways. Arrows indicate stimulatory or positive effects whereas blocked lines indicate inhibitory or negative effects. Question mark refers to mechanism, the existence of which has been reported in other cells (Ref. 46) but is presently hypothetical in vascular smooth muscle cells.

The effects of insulin on cultured smooth muscle cell motility and proliferation appear to be diverse. Thus, acute treatment with insulin reportedly opposes PDGF-induced cell motility, at least in part, via a mechanism mediated by nitric oxide and cGMP (7, 27, 29). In the present study, insulin induced a modest increase (∼10%) of motility. However, insulin virtually doubled the motogenic effect of PDGF. Because PDGF induces upregulation of PTP1B levels and because PTP1B induces suppression of PDGF-induced cell motility, as reported by our group (6) and as verified in the present study, the co-motogenic effect of insulin is directly attributable to its capacity to suppress the counter-regulatory influence of PTP1B. We have also reported that PTP1B levels are upregulated in vascular injury and that PTP1B suppresses the formation of neointima in injured carotid arteries. Thus the present findings provide a novel framework to explain how hyperinsulinemia enhances experimental neointima formation (19, 26, 45, 59) and vascular disease in humans with type 2 diabetes (2, 11, 52, 56).

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-63886 and HL-72902.

Acknowledgments

Present address of Y. Chang: Department of Pharmacology, A.T. Still University, 800 W. Jefferson St., Kirksville, MO 63501.

Present address of B. Ceacareanu: 8315 Trinity Rd, Memphis, TN 38018.

Present address of M. Dixit: Department of Biotechnology, Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IIT Madras), Chennai 600036, India.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe J, Deguchi J, Matsumoto T, Takuwa N, Noda M, Ohno M, Makuuchi M, Kurokawa K, Takuwa Y. Stimulated activation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor in vivo in balloon-injured arteries: a link between angiotensin II and intimal thickening. Circulation 96: 1906–1913, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonora E, Tessari R, Micciolo R, Zenere M, Targher G, Padovani R, Falezza G, Muggeo M. Intimal-medial thickness of the carotid artery in nondiabetic and NIDDM patients. Relationship with insulin resistance. Diabetes Care 20: 627–631, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown C, Pan X, Hassid A. Nitric oxide and C-type atrial natriuretic peptide stimulate primary aortic smooth muscle cell migration via a cGMP-dependent mechanism: relationship to microfilament dissociation and altered cell morphology. Circ Res 84: 655–667, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang Y, Ceacareanu B, Dixit M, Sreejayan N, Hassid A. Nitric oxide-induced motility in aortic smooth muscle cells: role of protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 and GTP-binding protein Rho. Circ Res 91: 390–397, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang Y, Ceacareanu B, Zhuang D, Zhang C, Pu Q, Ceacareanu AC, Hassid A. Counter-regulatory function of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B in platelet-derived growth factor- or fibroblast growth factor-induced motility and proliferation of cultured smooth muscle cells and in neointima formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 501–507, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang Y, Zhuang D, Zhang C, Hassid A. Increase of PTP levels in vascular injury and in cultured aortic smooth muscle cells treated with specific growth factors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2201–H2208, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cirri P, Taddei ML, Chiarugi P, Buricchi F, Caselli A, Paoli P, Giannoni E, Camici G, Manao G, Raugei G, Ramponi G. Insulin inhibits platelet-derived growth factor-induced cell proliferation. Mol Biol Cell 16: 73–83, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dadke S, Kusari A, Kusari J. Phosphorylation and activation of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) 1B by insulin receptor. Mol Cell Biochem 221: 147–154, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlfors G, Chen Y, Gustafsson B, Arnqvist HJ. Inhibitory effect of diabetes on proliferation of vascular smooth muscle after balloon injury in rat aorta. Int J Exp Diabetes Res 1: 101–109, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J 351: 95–105, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Pergola G, Ciccone M, Pannacciulli N, Modugno M, Sciaraffia M, Minenna A, Rizzon P, Giorgino R. Lower insulin sensitivity as an independent risk factor for carotid wall thickening in normotensive, non-diabetic, non-smoking normal weight and obese premenopausal women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 24: 825–829, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dixit M, Zhuang D, Ceacareanu B, Hassid A. Treatment with insulin uncovers the motogenic capacity of nitric oxide in aortic smooth muscle cells: dependence on Gab1 and Gab1-SHP2 association. Circ Res 93: e113–123, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Englesbe MJ, Davies MG, Hawkins SM, Hsieh PC, Daum G, Kenagy RD, Clowes AW. Arterial injury repair in nonhuman primates-the role of PDGF receptor-beta. J Surg Res 119: 80–84, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faber JE, Yang N. Balloon injury alters alpha-adrenoceptor expression across rat carotid artery wall. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 33: 204–210, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferns GA, Raines EW, Sprugel KH, Motani AS, Reidy MA, Ross R. Inhibition of neointimal smooth muscle accumulation after angioplasty by an antibody to PDGF. Science 253: 1129–1132, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fishbein I, Waltenberger J, Banai S, Rabinovich L, Chorny M, Levitzki A, Gazit A, Huber R, Mayr U, Gertz SD, Golomb G. Local delivery of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-specific tyrphostin inhibits neointimal formation in rats. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 667–676, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flint AJ, Tiganis T, Barford D, Tonks NK. Development of “substrate-trapping” mutants to identify physiological substrates of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 1680–1685, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giese NA, Marijianowski MM, McCook O, Hancock A, Ramakrishnan V, Fretto LJ, Chen C, Kelly AB, Koziol JA, Wilcox JN, Hanson SR. The role of alpha and beta platelet-derived growth factor receptor in the vascular response to injury in nonhuman primates. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19: 900–909, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goalstone ML, Natarajan R, Standley PR, Walsh MF, Leitner JW, Carel K, Scott S, Nadler J, Sowers JR, Draznin B. Insulin potentiates platelet-derived growth factor action in vascular smooth muscle cells. Endocrinology 139: 4067–4072, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haj FG, Markova B, Klaman LD, Bohmer FD, Neel BG. Regulation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B. J Biol Chem 278: 739–744, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart CE, Kraiss LW, Vergel S, Gilbertson D, Kenagy R, Kirkman T, Crandall DL, Tickle S, Finney H, Yarranton G, Clowes AW. PDGFbeta receptor blockade inhibits intimal hyperplasia in the baboon. Circulation 99: 564–569, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassid A, Arabshahi H, Bourcier T, Dhaunsi GS, Matthews C. Nitric oxide selectively amplifies FGF-2-induced mitogenesis in primary rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H1040–H1048, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassid A, Yao J, Huang S. NO alters cell shape and motility in aortic smooth muscle cells via protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H1014–H1026, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heldin CH, Ostman A, Ronnstrand L. Signal transduction via platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1378: F79–113, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imai Y, Clemmons DR. Roles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in stimulation of vascular smooth muscle cell migration and deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis by insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocrinology 140: 4228–4235, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Indolfi C, Torella D, Cavuto L, Davalli AM, Coppola C, Esposito G, Carriero MV, Rapacciuolo A, Di Lorenzo E, Stabile E, Perrino C, Chieffo A, Pardo F, Chiariello M. Effects of balloon injury on neointimal hyperplasia in streptozotocin-induced diabetes and in hyperinsulinemic nondiabetic pancreatic islet-transplanted rats. Circulation 103: 2980–2986, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacob A, Molkentin JD, Smolenski A, Lohmann SM, Begum N. Insulin inhibits PDGF-directed VSMC migration via NO/cGMP increase of MKP-1 and its inactivation of MAPKs. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C704–C713, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jawien A, Bowen-Pope DF, Lindner V, Schwartz SM, Clowes AW. Platelet-derived growth factor promotes smooth muscle migration and intimal thickening in a rat model of balloon angioplasty. J Clin Invest 89: 507–511, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahn AM, Allen JC, Seidel CL, Zhang S. Insulin inhibits migration of vascular smooth muscle cells with inducible nitric oxide synthase. Hypertension 35: 303–306, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi T, Hayashi Y, Taguchi K, Matsumoto T, Kamata K. ANG II enhances contractile responses via PI3-kinase p110-δ pathway in aortas from diabetic rats with systemic hyperinsulinemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H846–H853, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong M, Mounier C, Wu J, Posner BI. Epidermal growth factor-induced phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation and DNA synthesis. Identification of Grb2-associated binder 2 as the major mediator in rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem 275: 36035–36042, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kornowski R, Mintz GS, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Bucher TA, Hong MK, Popma JJ, Leon MB. Increased restenosis in diabetes mellitus after coronary interventions is due to exaggerated intimal hyperplasia. A serial intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation 95: 1366–1369, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kundra V, Escobedo JA, Kazlauskas A, Kim HK, Rhee SG, Williams LT, Zetter BR. Regulation of chemotaxis by the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta. Nature 367: 474–476, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levitzki A PDGF receptor kinase inhibitors for the treatment of restenosis. Cardiovasc Res 65: 581–586, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C, Ford ES, McGuire LC, Mokdad AH, Little RR, Reaven GM. Trends in hyperinsulinemia among nondiabetic adults in the U.S. Diabetes Care 29: 2396–2402, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahadev K, Zilbering A, Zhu L, Goldstein BJ. Insulin-stimulated hydrogen peroxide reversibly inhibits protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1b in vivo and enhances the early insulin action cascade. J Biol Chem 276: 21938–21942, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng TC, Buckley DA, Galic S, Tiganis T, Tonks NK. Regulation of insulin signaling through reversible oxidation of the protein-tyrosine phosphatases TC45 and PTP1B. J Biol Chem 279: 37716–37725, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myllarniemi M, Calderon L, Lemstrom K, Buchdunger E, Hayry P. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation. FASEB J 11: 1119–1126, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noiseux N, Boucher CH, Cartier R, Sirois MG. Bolus endovascular PDGFR-beta antisense treatment suppressed intimal hyperplasia in a rat carotid injury model. Circulation 102: 1330–1336, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogihara T, Asano T, Ando K, Chiba Y, Sakoda H, Anai M, Shojima N, Ono H, Onishi Y, Fujishiro M, Katagiri H, Fukushima Y, Kikuchi M, Noguchi N, Aburatani H, Komuro I, Fujita T. Angiotensin II-induced insulin resistance is associated with enhanced insulin signaling. Hypertension 40: 872–879, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogihara T, Asano T, Ando K, Chiba Y, Sekine N, Sakoda H, Anai M, Onishi Y, Fujishiro M, Ono H, Shojima N, Inukai K, Fukushima Y, Kikuchi M, Fujita T. Insulin resistance with enhanced insulin signaling in high-salt diet-fed rats. Diabetes 50: 573–583, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Onishi Y, Honda M, Ogihara T, Sakoda H, Anai M, Fujishiro M, Ono H, Shojima N, Fukushima Y, Inukai K, Katagiri H, Kikuchi M, Oka Y, Asano T. Ethanol feeding induces insulin resistance with enhanced PI 3-kinase activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 303: 788–794, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pagliassotti MJ, Kang J, Thresher JS, Sung CK, Bizeau ME. Elevated basal PI 3-kinase activity and reduced insulin signaling in sucrose-induced hepatic insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 282: E170–E176, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Panek RL, Dahring TK, Olszewski BJ, Keiser JA. PDGF receptor protein tyrosine kinase expression in the balloon-injured rat carotid artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17: 1283–1288, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park SH, Marso SP, Zhou Z, Foroudi F, Topol EJ, Lincoff AM. Neointimal hyperplasia after arterial injury is increased in a rat model of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Circulation 104: 815–819, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ravichandran LV, Chen H, Li Y, Quon MJ. Phosphorylation of PTP1B at Ser(50) by Akt impairs its ability to dephosphorylate the insulin receptor. Mol Endocrinol 15: 1768–1780, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sano H, Sudo T, Yokode M, Murayama T, Kataoka H, Takakura N, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa SI, Kita T. Functional blockade of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta but not of receptor-alpha prevents vascular smooth muscle cell accumulation in fibrous cap lesions in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation 103: 2955–2960, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shepherd PR Mechanisms regulating phosphoinositide 3-kinase signalling in insulin-sensitive tissues. Acta Physiol Scand 183: 3–12, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sirois MG, Simons M, Edelman ER. Antisense oligonucleotide inhibition of PDGFR-beta receptor subunit expression directs suppression of intimal thickening. Circulation 95: 669–676, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sreejayan N, Lin Y, Hassid A. NO attenuates insulin signaling and motility in aortic smooth muscle cells via protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B-mediated mechanism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 1086–1092, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki LA, Poot M, Gerrity RG, Bornfeldt KE. Diabetes accelerates smooth muscle accumulation in lesions of atherosclerosis: lack of direct growth-promoting effects of high glucose levels. Diabetes 50: 851–860, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takagi T, Yoshida K, Akasaka T, Kaji S, Kawamoto T, Honda Y, Yamamuro A, Hozumi T, Morioka S. Hyperinsulinemia during oral glucose tolerance test is associated with increased neointimal tissue proliferation after coronary stent implantation in nondiabetic patients: a serial intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol 36: 731–738, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tao J, Malbon CC, Wang HY. Insulin stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation and inactivation of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B in vivo. J Biol Chem 276: 29520–29525, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Taylor AM, Hanchett R, Natarajan R, Hedrick CC, Forrest S, Nadler JL, McNamara CA. The effects of leukocyte-type 12/15-lipoxygenase on Id3-mediated vascular smooth muscle cell growth. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 2069–2074, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toba H, Gomyo E, Miki S, Shimizu T, Yoshimura A, Inoue R, Sawai N, Tsukamoto R, Asayama J, Kobara M, Nakata T. Hyperinsulinaemia increases the gene expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/akt pathway in rat aorta. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 33: 440–447, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang PW, Liou CW, Wang ST, Eng HL, Liu RT, Tung SC, Chien WY, Lu YC, Kuo MC, Hsieh CJ, Chen CH, Chen JF, Chu JW, Reaven GM. Relative impact of low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol concentration and insulin resistance on carotid wall thickening in nondiabetic, normotensive volunteers. Metabolism 51: 255–259, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watson KE, Peters Harmel AL, Matson G. Atherosclerosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus: the role of insulin resistance. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 8: 253–260, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilcox JN, Smith KM, Williams LT, Schwartz SM, Gordon D. Platelet-derived growth factor mRNA detection in human atherosclerotic plaques by in situ hybridization. J Clin Invest 82: 1134–1143, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamada H, Tsushima T, Murakami H, Uchigata Y, Iwamoto Y. Potentiation of mitogenic activity of platelet-derived growth factor by physiological concentrations of insulin via the MAP kinase cascade in rat A10 vascular smooth muscle cells. Int J Exp Diabetes Res 3: 131–144, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamasaki Y, Miyoshi K, Oda N, Watanabe M, Miyake H, Chan J, Wang X, Sun L, Tang C, McMahon G, Lipson KE. Weekly dosing with the platelet-derived growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor SU9518 significantly inhibits arterial stenosis. Circ Res 88: 630–636, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yamasaki Y, Miyoshi K, Oda N, Watanabe M, Miyake H, Chan J, Wang X, Sun L, Tang C, McMahon G, Lipson KE. Weekly dosing with the platelet-derived growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor SU9518 significantly inhibits arterial stenosis. Circ Res 88: 630–636, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zavaroni I, Ardigo D, Zuccarelli A, Pacetti E, Piatti PM, Monti L, Valtuena S, Massironi P, Rossi PC, Reaven GM. Insulin resistance/compensatory hyperinsulinemia predict carotid intimal medial thickness in patients with essential hypertension. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 16: 22–27, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhuang D, Ceacareanu AC, Lin Y, Ceacareanu B, Dixit M, Chapman KE, Waters CM, Rao GN, Hassid A. Nitric oxide attenuates insulin- or IGF-I-stimulated aortic smooth muscle cell motility by decreasing H2O2 levels: essential role of cGMP. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H2103–H2112, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]