Abstract

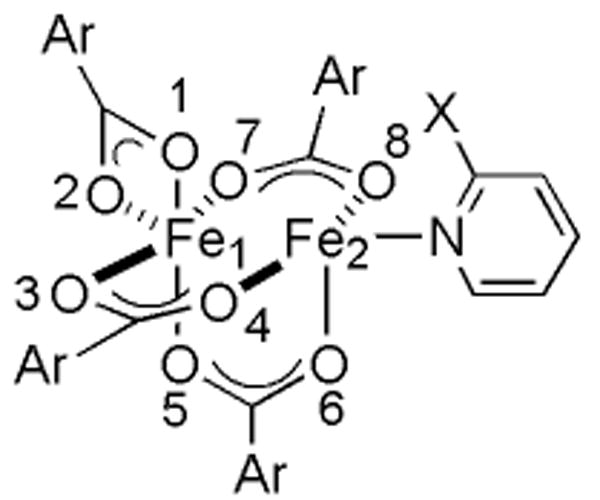

Progress toward the development of functional models of the carboxylate-bridged diiron active site in soluble methane monooxygenase is described in which potential substrates are introduced as substituents on bound pyridine ligands. Thiol, sulfide, sulfoxide, and phosphine moieties incorporated into a pyridine ligand were allowed to react with the preassembled diiron(II) complex [Fe2(μ-O2CArR)2(O2CArR)2(THF)2], where -O2CArR is a sterically hindered 2,6-di(p-tolyl)- or 2,6-di(p-fluorophenyl)benzoate (R = Tol or 4-FPh). The resulting diiron(II) complexes were characterized crystallographically. Triply- and doubly-bridged compounds [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-MeSpy)] (4) and [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(2-MeS(O)py)2] (5) resulted when 2-methylthiopyridine (2-MeSpy) and 2-pyridylmethylsulfoxide (2-MeS(O)py), respectively, were employed. Another triply-bridged diiron(II) complex, [Fe2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)3(O2CAr4-FPh)(2-Ph2Ppy)] (3), was obtained containing 2-diphenylphosphinopyridine (2-Ph2Ppy). Use of 2-mercaptopyridine (2-HSpy) afforded the mononuclear complex [Fe(O2CArTol)2(2-HSpy)2] (6a). Together with that of previously reported [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-PhSpy)] (2) and [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-Ph2Ppy)] (1), the dioxygen reactivity of these iron(II) complexes was investigated. A dioxygen-dependent intermediate (6b) formed upon exposure of 6a to O2, the electronic structure of which was probed by various spectroscopic methods. Exposure of 4 and 5 to dioxygen revealed both sulfide and sulfoxide oxidation. Oxidation of 3 in CH2Cl2 affords [Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)(O2CAr4-FPh)3(OH2)(2-Ph2P(O)py)] (8), which contains the biologically relevant {Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CR)}3+ core. This reaction is sensitive to the choice of carboxylate ligands, however, since the p-tolyl analog 1 yielded a hexanuclear species, 7, upon oxidation.

Introduction

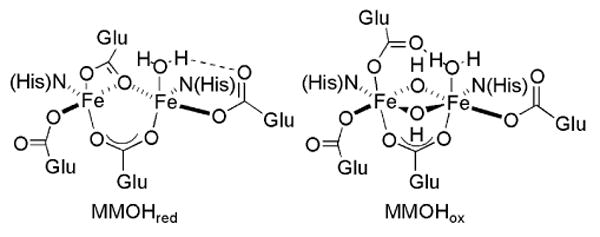

Dioxygen activation and O-atom transfer reactions promoted by iron-containing metalloenzymes are of considerable interest both for ecological and industrial applications.1,2 Soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO) is one such enzyme system that is used by methanotropic bacteria to catalyze the selective conversion of methane to methanol.3 In addition to saturated hydrocarbons, olefins, methanethiol, amines, and sulfides can act as substrates.3-6 A carboxylate-bridged non-heme diiron active site, housed in the hydroxylase component (MMOH) of sMMO, is responsible for the binding and reductive activation of dioxygen.7-10 In the reduced state (MMOHred), the diiron(II) centers are bridged by two carboxylates and each contains an additional monodentate carboxylate ligand. One of the latter is involved in hydrogen bonding with a coordinated water molecule. In the oxidized, resting state of the enzyme (MMOHox), the diiron(III) center is bridged by two hydroxide ions and a single carboxylate group. The other three carboxylate residues are monodentate, one of which is hydrogen bonded to a coordinated water molecule. Representations of MMOHred and MMOHox are provided in Chart 1.

Chart 1.

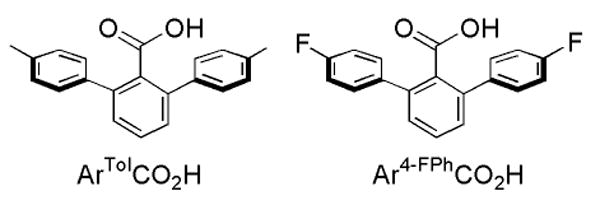

The preparation and study of structural, spectroscopic, and functional models for the active sites in metalloproteins have provided insight into the mechanisms of their oxidation chemistry, enhancing and extending our understanding of the natural systems.11 A variety of symmetric diiron complexes carrying N-donor and assorted O-donor ligands have been reported as mimics for the diiron sites in MMOH and related enzymes.12-14 Complexes having two carboxylate ligands per iron atom are necessary to provide an accurate representation of the MMOH active site. Self-assembly of discrete dinuclear centers with such carboxylate ligands is challenged by their tendency to form oligomers.15-20 Terphenyl-based carboxylate ligands facilitate the assembly of discrete dinuclear complexes and mimic to some degree the hydrophobic pocket present at the protein active sites (Chart 2).21-23

Chart 2.

In addition to four carboxylate ligands, two nitrogen donors are required to replicate the stoichiometry of the diiron core at the MMOH active site. One approach to emulate enzyme functionally is to tether a substrate to the N-donor ligand, increasing its chances of reacting with a dioxygen-activated dimetallic core. Introduction of dioxygen into solutions of the diiron(II) complexes [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(N,N-Bn2en)2],24,25 where -O2CArTol is 2,6-di(p-tolyl)-benzoate and N,N-Bn2en is N,N-dibenzylethylenediamine, [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)4(BAp-OMe)2],26 where BAp-OMe is p-methoxybenzylamine, and [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)4(NH2(CH2)2SBn)2],27 led to the evolution of benzaldehyde. This chemistry is formally the result of intramolecular benzylic hydroxylation followed by dealkylation. The strategy has been extended to include benzyl- or ethyl-derivatized pyridine ligands, which react to form the corresponding alcohol and/or ketone.27,28

In addition to C–H activation, the carboxylate-rich diiron center in MMOH is capable of oxidizing alkyl sulfides and thiols.3,6 We therefore extended our studies to examine carboxylate-bridged diiron(II) complexes with pyridine ligands incorporating thiol, sulfide, sulfoxide, and phosphine as tethered substrates. Upon exposure to dioxygen, these complexes react to form the corresponding sulfoxide, sulfone and phosphine oxide. The results of this study, a portion of which has been previously communicated,28 are reported here.

Experimental Section

General Considerations

All reagents were obtained from commercial suppliers and used as received, unless otherwise noted. Dichloromethane and pentane were saturated with nitrogen and purified by passage through activated Al2O3 columns under argon.29 Dioxygen (99.994%, BOC Gases) was dried by passing the gas stream through a column of Drierite. The synthesis and characterization of [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(THF)2], [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-Ph2Ppy)] (1), and [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-PhSpy] (2) were reported previously.21,28 2-Phenylthiopyridine (2-PhSpy), 2-phenylpyridylsulfoxide (2-PhS(O)py), 2-methylthiopyridine (2-MeSpy), 2-methylpyridylsulfoxide (2-MeS(O)py), and 2-methylpyridylsulfone (2-MeS(O)2py) were prepared by modified literature procedures, and their purity was confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy.30 2-Pyridyldiphenylphosphine oxide (2-Ph2P(O)py) was synthesized according to a published procedure,31 and the purity was checked by 1H and 31P NMR spectroscopy. Air-sensitive manipulations were carried out under nitrogen in an Mbraun drybox. All samples were pulverized and dried under vacuum at 60 °C to remove solvent prior to determining their elemental composition.

[Fe2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)3(O2CAr4-FPh)(2-Ph2Ppy)] (3)

To a CH2Cl2 (4 mL) solution of [Fe2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)2(O2CAr4-FPh)2(THF)2] (150 mg, 0.100 mmol), 2-Ph2Ppy (28.5 mg, 0.108 mmol) was added to form an orange solution that was stirred for 20 min. Diffusion of pentane into the reaction mixture yielded orange block crystals (151 mg, 93%) of 3. FT-IR (KBr, cm-1): 3062 (w), 2954 (w), 2863 (w), 1891 (w), 1604 (s), 1560 (m), 1510 (s), 1455 (s), 1406 (s), 1380 (s), 1299 (w), 1221 (s), 1158 (s), 1093 (m), 1049 (w), 1015 (m), 841 (m), 833 (m), 806 (s), 791 (m), 767 (m), 747 (w), 701 (m), 582 (w), 554 (s), 528 (s), 502 (w), 463 (w), 417 (w). Anal. Calcd. for C93H58NFe2O8F8P: C, 69.29; H, 3.63; N, 0.87; P, 1.92. Found: C, 68.92; H, 3.70; N, 1.11; P, 1.68.

[Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-MeSpy)] (4)

In a CH2Cl2 (4 mL) solution, [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(THF)2] (114 mg, 0.782 mmol) was allowed to react with 2-MeSpy (21.6 mg, 0.173 mmol) for 15 min. Removal of the solvent under reduced pressure left a residue that was extracted into 2 mL of dichloroethane. Diffusion of pentane vapor into the bright orange-yellow solution afforded yellow block crystals (0.106 mg, 94%) of 4 suitable for X-ray crystallography. FT-IR (KBr, cm-1): 3050 (w), 3023 (w), 2918 (w), 2860 (w), 1601 (s), 1576 (m), 1559 (m), 1513 (s), 1453 (s), 1406 (s), 1382 (s), 1304 (w), 1283 (w), 1185 (w), 1149 (w), 1109 (w), 1071 (w), 1019 (m), 970 (w), 832 (w), 817 (s), 799 (s), 765 (s), 737 (m), 702 (s), 641 (m), 608 (w), 583 (m), 557 (w), 523 (m), 465 (m), 410 (w). Anal. Calcd. for C90H75NO8SFe2·0.5C2H4Cl2: C, 73.27; H, 5.20; N, 0.94. Found: C, 73.29; H, 5.45; N, 1.12.

[Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(2-MeS(O)py)2] (5)

A bright red-orange solution was produced upon the addition of 2-MeS(O)py (28.2mg, 0.200 mmol) to [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(THF)2] (98.9 mg, 0.0677 mmol) in 6 mL of CH2Cl2 and a red powder (91.8 mg, 85%) was isolated after diffusion of pentane into the reaction mixture. Red block crystals of 5 suitable for X-ray diffraction studies were obtained by diffusing pentane vapor into a chlorobenzene solution of 5. FT-IR (KBr, cm-1): 3053 (w), 3022 (w), 2917 (w), 2862 (w), 1588 (s), 1562 (s), 1540 (s), 1514 (s), 1454 (s), 1410 (s), 1376 (s), 1304 (w), 1263 (w), 1186 (w), 1147 (w), 1109 (w), 1088 (w), 1020 (m), 1008 (s), 967, 818 (s), 800 (s), 785 (s), 765 (s), 737 (m), 711 (m), 703 (m), 637 (m), 608 (w), 584 (m), 542 (w), 520 (m), 450 (w), 411 (w). Anal. Calcd. for C96H82N2Fe2O10S2: C, 72.09; H, 5.17; N, 1.75. Found: C, 71.71; H, 4.85; N, 1.81.

[Fe(O2CArTol)2(2-HSpy)2] (6a)

A solution of [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(THF)2] (174 mg, 0.119 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was combined with 2-mercaptopyridine (2-HSpy) (62.9 mg, 0.566 mmol) and stirred for 15 min. Vapor diffusion of pentane into this orange solution afforded orange blocks of 6a (199 mg, 95%) suitable for X-ray crystallography. FT-IR (KBr, cm-1): 3195 (w), 3114 (w), 3053 (w), 2916 (w), 2862 (w), 1591 (s), 1539 (s), 1514 (s), 1446 (s), 1410 (s), 1375 (s), 1269 (w), 1130 (s), 1085 (w), 1020 (w), 995 (m), 916 (w), 847 (w), 818 (m), 801 (s), 786 (m), 755 (s), 726 (m), 707 (m), 619 (w), 584 (w), 539 (w), 521 (m), 486 (w), 442 (m). Anal. Calcd. for C52H44N2FeO4S2: C, 70.90; H, 5.03; N, 3.18. Found: C, 71.81; H, 4.91; N, 3.32.

[Fe6(μ4-O)2(μ-OH)6(μ-O2CArTol)4Cl4(2-Ph2P(O)py)2] (7)

An orange 6.0 mM CH2Cl2 solution of 1 (95.3 mg, 0.0603 mmol) was bubbled with O2 for 10 min and stirred for 50 additional min under an atmosphere of dioxygen. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the remaining residue was extracted into 1.5 mL of CH2Cl2. Vapor diffusion of pentane into the solution yielded orange crystalline clusters of 7, one of which was used for X-ray diffraction studies. Although the structure of 7 could be determined, bulk samples could not be obtained.

[Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)(O2CAr4-FPh)3(OH2)(2-Ph2P(O)py)] (8)

A bright yellow 5.80 mM toluene solution of 3 (mg, mmol) was bubbled with dry dioxygen for 10 min and allowed to stir for 50 additional min under an atmosphere of O2. The solvent was then reduced under vacuum leaving a residue that was extracted into 1.5 mL of CH2Cl2. Bright yellow block crystals of 8 (49.3 mg, 25%) suitable for X-ray diffraction studies were isolated by diffusing pentane into the solution. FT-IR (KBr, cm-1): 3572 (m), 3432 (br), 3057 (w), 1735 (w), 1604 (s), 1511 (s), 1455(s), 1407 (m), 1345 (s), 1222 (s), 1159 (s), 1136 (m), 1095 (w), 1009 (w), 839 (s), 808 (s), 791 (s), 771 (m), 736 (w), 698 (s), 555 (s), 536 (s), 460 (w), 414 (w). Anal. Calcd. for C93H62NFe2O12F8P: C, 66.48; H, 3.72; N, 0.83; P, 1.84. Found: C, 66.23; H, 3.69; N, 0.76; P, 1.58.

Physical Measurements

FT-IR spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet Avatar 360 spectrometer with OMNIC software. 1H NMR data recorded on a Varian 300 spectrometer and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 500 spectrometer, both housed in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Chemistry Instrument Facility (MIT DCIF). Chemical shifts were referenced to the residual solvent peaks for proton experiments and to an external standard, H3PO4, for 31P experiments. All spectra were recorded at ambient probe temperature, 293 K.

X-ray Crystallographic Studies

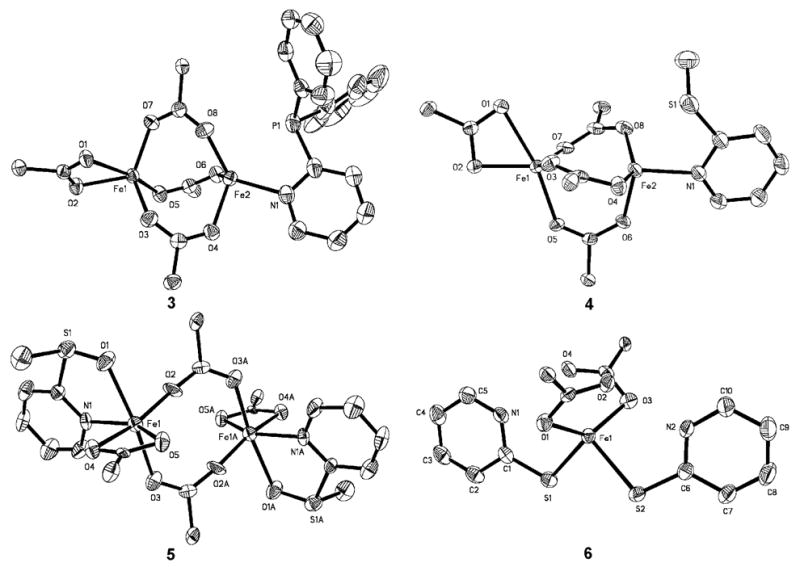

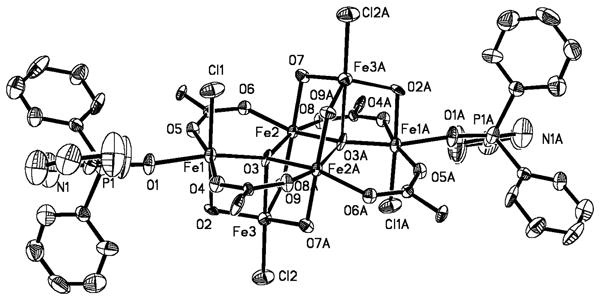

Intensity data were collected on a Bruker (formerly Siemens) APEX CCD diffractometer with graphite-monochromated Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å), controlled by a Pentium-based PC running the SMART software package.32 Single crystals were mounted on the tips of glass fibers, coated with paratone-N oil, and cooled to −100 °C under a stream of N2 maintained by a KRYO-FLEX low-temperature apparatus. Data collection and reduction protocols are described elsewhere.33 The structures were solved by direct methods and refined on F2 by using the SHELXTL-97 software34 incorporated in the SHELXTL software package.35 Empirical absorption corrections were applied with SADABS,36 part of the SHELXTL program package, and the structures were checked for higher symmetry by using the PLATON software.37 All non-hydrogen atoms were located and their positions refined with anisotropic thermal parameters by least-squares cycles and Fourier syntheses. In general hydrogen atoms were assigned to idealized positions and given thermal parameters equivalent to either 1.5 (methyl hydrogen atoms) or 1.2 (all other hydrogen atoms) times the thermal parameter of the carbon atom to which they were attached. The structure of 3 has one dichloroethane molecule in the lattice in which one of the chlorine atoms is disordered over two positions and was refined with a 70/30 occupancy. Four carbon atoms in one of the p-fluorophenyl rings were disordered over two positions and were refined at 50% occupancy. In the structure of 4, one of the -O2CArTol ligands was disordered and was modeled over two positions with 50% occupancy. A pentane and 1.5 dichloroethane molecules are present in the unit cell of 4. The pentane molecule is severely disordered, and each carbon atom was modeled over three positions using identical anisotropic displacement parameters. The half dichloroethane molecule lies on a center of symmetry; the chlorine atom is disordered and was refined with the atoms distributed equally over two positions. Compound 5 has a chlorobenzene molecule in the crystal lattice. The structure of 7 has four CH2Cl2 molecules in the lattice. The structure of 8 has three CH2Cl2 molecules in the lattice. The structures of 3 – 8 are shown in Figures 1 – 3 and S1 – S6 (Supporting Information). Data collection and experimental details are summarized in Table S1; those for 1 and 2 were reported previously.28 Selected bond lengths and angles for 1 – 8 are provided in Tables 1, 2, and S2 – S4.

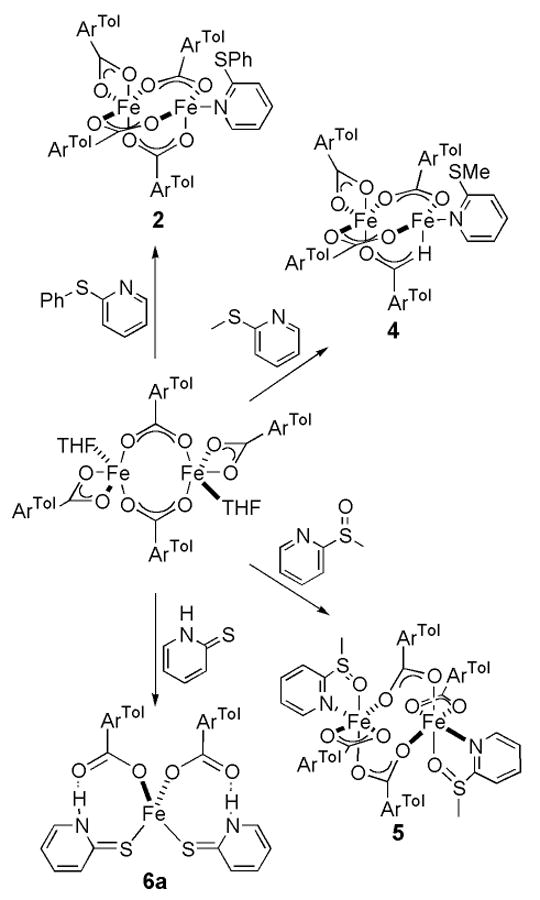

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagrams of [Fe2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)3(O2CAr4-FPh)(2-Ph2Ppy)] (3), [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-MeSpy)] (4), [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(2-MeS(O)py)2] (5), and [Fe(O2CArTol)2(2-HSpy)2] (6a) showing 50 % probability thermal ellipsoids for all non-hydrogen atoms. The aromatic rings of carboxylate ligands are omitted for clarity.

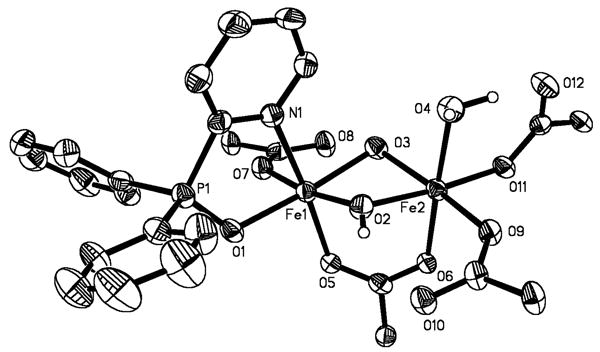

Figure 3.

ORTEP drawing of [Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)(O2CAr4-FPh)3(OH2)(2-Ph2P(O)py)] (8) illustrating 50% probability thermal ellipsoids for all non-hydrogen atoms. The aromatic rings of the -O2CAr4-FPh ligands are omitted for clarity.

Table 1.

Selected Interatomic Distances (Å) and Angles (deg) for [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-Ph2Ppy)] (1), [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-PhSpy)] (2), [Fe2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)3(O2CAr4-FPh)(2-Ph2Ppy)] (3), and [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-MeSpy)] (4)a

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Fe1…Fe2 | 3.3094(6) | 3.2712(8) | 3.4534(8) | 3.2496(7) |

| Fe2…X | 2.8322(7) | 3.0897(9) | 2.9551(13) | 2.9091(10) |

| Fe1–O1 | 2.2162(13) | 2.2013(16) | 2.297(3) | 2.256(2) |

| Fe1–O2 | 2.0826(13) | 2.0869(15) | 2.068(3) | 2.059(2) |

| Fe1–O3 | 2.0512(13) | 2.0610(16) | 2.000(3) | 2.055(2) |

| Fe1–O5 | 2.0342(12) | 2.0266(15) | 2.054(3) | 2.026(2) |

| Fe1–O7 | 2.0602(12) | 2.0484(15) | 2.017(3) | 2.046(14) |

| Fe2–N1 | 2.1314(16) | 2.1024(18) | 2.127(3) | 2.077(3) |

| Fe2–O4 | 1.9892(12) | 1.9767(16) | 2.022(3) | 1.977(2) |

| Fe2–O6 | 2.0570(12) | 2.0155(15) | 1.985(2) | 2.034(2) |

| Fe2–O8 | 1.9981(13) | 1.9786(15) | 1.998(3) | 1.982(12) |

| O1–Fe1–O2 | 61.35(5) | 61.19(6) | 60.07(9) | 60.8(15) |

| O1–Fe1–O3 | 91.81(5) | 88.64(6) | 86.96(10) | 87.4(16) |

| O1–Fe1–O5 | 167.13(5) | 109.45(6) | 166.37(10) | 168.1(15) |

| O1–Fe1–O7 | 87.81(5) | 92.77(6) | 91.98(10) | 91.7(16) |

| O2–Fe1–O3 | 111.56(5) | 109.83(7) | 104.65(11) | 109.4(17) |

| O2–Fe1–O5 | 107.01(5) | 169.04(6) | 106.30(10) | 108.4(16) |

| O2–Fe1–O7 | 110.11(6) | 114.07(6) | 118.47(11) | 111.3(18) |

| O3–Fe1–O5 | 98.07(5) | 89.61(6) | 97.32(11) | 92.2(16) |

| O3–Fe1–O7 | 131.95(5) | 130.35(6) | 129.17(12) | 132.5(17) |

| O5–Fe1–O7 | 91.65(5) | 95.59(6) | 95.25(11) | 97.3(16) |

| O4–Fe2–N1 | 103.14(6) | 106.40(7) | 88.53(12) | 110(2) |

| O6–Fe2–N1 | 91.33(5) | 97.36(7) | 122.81(12) | 95.8(18) |

| O8–Fe2–N1 | 111.28(6) | 99.52(7) | 120.56(12) | 100(2) |

| O4–Fe2–O6 | 100.35(5) | 104.73(6) | 103.10(11) | 102.1(17) |

| O4–Fe2–O8 | 139.10(5) | 138.73(7) | 122.18(11) | 102.4(18) |

| O6–Fe2–O8 | 100.29(5) | 103.10(6) | 99.91(11) | 102.4(18) |

Numbers in parentheses are estimated standard deviations of the last significant figure. Atoms are labeled as indicated Figures 1, S2, and S3.

Table 2.

Selected Interbond Lengths and Angles for 8a

| Bond length (Å) | Interbond Angle (deg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe1…Fe2 | 2.9725(11) | Fe1–O2–Fe2 | 98.10(19) |

| Fe2–O3–Fe1 | 97.35(18) | ||

| Fe1–N1 | 2.210(4) | O1–Fe1–N1 | 80.49(15) |

| Fe1–O1 | 2.023(3) | O2–Fe1–N1 | 84.76(17) |

| Fe1–O2 | 1.954(4) | O3–Fe1–N1 | 92.34(17) |

| Fe1–O3 | 1.981(4) | O5–Fe1–N1 | 172.91(15) |

| Fe1–O5 | 2.003(3) | O7–Fe1–N1 | 92.17(15) |

| Fe1–O7 | 1.947(3) | O1–Fe1–O2 | 97.51(16) |

| Fe2–O2 | 1.981(4) | O1–Fe1–O3 | 172.11(17) |

| Fe2–O3 | 1.977(4) | O1–Fe1–O5 | 93.26(14) |

| Fe2–O4 | 2.097(4) | O1–Fe1–O7 | 89.81(14) |

| Fe2–O6 | 2.017(3) | O2–Fe1–O3 | 78.40(17) |

| Fe2–O9 | 1.974(3) | O2–Fe1–O5 | 92.81(17) |

| Fe2–O11 | 1.976(3) | O2–Fe1–O7 | 171.47(17) |

| O3–Fe1–O5 | 93.68(16) | ||

| O2…O10 | 2.708(6) | O3–Fe1–O7 | 93.80(16) |

| O3…O8 | 2.803(6) | O5–Fe1–O7 | 91.14(14) |

| O4…O12 | 2.537(6) | O2–Fe2–O3 | 77.85(17) |

| O2–Fe2–O4 | 89.52(19) | ||

| O2–Fe2–O6 | 91.58(16) | ||

| O2–Fe2–O9 | 91.96(16) | ||

| O2–Fe2–O11 | 174.61(17) | ||

| O3–Fe2–O4 | 88.81(17) | ||

| O3–Fe2–O6 | 93.02(15) | ||

| O3–Fe2–O9 | 168.94(16) | ||

| O3–Fe2–O11 | 97.06(15) | ||

| O4–Fe2–O6 | 178.02(16) | ||

| O4–Fe2–O9 | 86.77(17) | ||

| O4–Fe2–O11 | 88.61(17) | ||

| O6–Fe2–O9 | 91.55(14) | ||

| O6–Fe2–O11 | 90.43(14) | ||

| O9–Fe2–O11 | 92.97(14) |

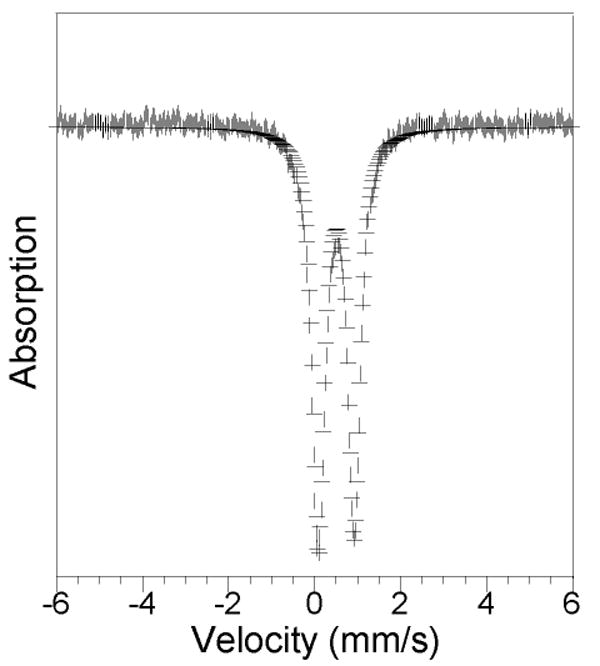

Mössbauer Spectroscopy

Mössbauer spectra were recorded on an MSI spectrometer (WEB Research Co.) with a 57Co source in a Rh matrix maintained at room temperature in the MIT DCIF. Solid samples of 6 and 8 were prepared by suspending ∼0.024 mmol of the yellow powdered material in Apeizon N grease and coating the mixture on the lid of a nylon sample holder. Data were collected at 4.2 K, and the isomer shift (δ) values are reported with respect to natural iron foil that was used for velocity calibration at room temperature. The spectra were fit to Lorentzian lines by using the WMOSS plot and fit program.38

Oxidation Product Analyses

Oxidation reactions were performed by exposing CH2Cl2 solutions of the diiron(II) complex to dioxygen at room temperature over a period of time, and in the case of 1 and 3, also in the presence of added 2-Ph2Ppy. During workup, Chelex was added to the reaction solutions to remove the iron salts. The resulting slurry was stirred for 2 h, after which the Chelex was removed by filtration. The resin was washed with CH2Cl2 twice more and the filtrates were combined. The solvent was removed in vacuo to afford the N-donor species for analysis. The products were identified by NMR spectroscopy and GC-MS by comparing their NMR spectra and retention times and mass spectral patterns to those of authentic samples. The amount of oxidized ligand obtained was quantitated by 31P NMR spectroscopy, using triphenylphosphine oxide as an internal standard for 1 and 3, and by GC-MS using 1,2-dichlorobenzene as an internal standard for 2, 4, and 5. All samples were prepared in an anaerobic glove box prior to bubbling with dried dioxygen. Control experiments established that, in the absence of the diiron(II) complexes, neither dioxygen saturated CH2Cl2 nor the workup procedure induces significant ligand oxidation.

GC-MS Analyses

Analyses were carried out on a Hewlett-Packard HP-5890 gas chromatograph connected to a HP-5971 mass analyzer. An Alltech Econo-cap EC-1 capillary column of dimensions (30 m × 0.53 mm × 1.2 μm) was employed with the following program to effect all separations: initial temperature = 100 °C; initial time = 4 min; temperature ramp = 100 – 210 °C at 20 deg/min; and final time = 4.5 min. Quantitations were made by comparison of the total ion count of 2-PhSpy, 2-PhS(O)py, 2-MeSpy, 2-MeS(O)py and 2-MeS(O)2py with that of 1,2-dichlorobenzene present as an internal standard. Calibration plots for the detector response were prepared for authentic samples of 2-PhSpy, 2-PhS(O)py, 2-MeSpy, 2-MeS(O)py, 2-MeS(O)2py and 1,2-dichlorobenzene standard by using stock solutions of known concentrations.

Oxygenation of 6a

In a typical reaction compound 6a was dissolved in CH2Cl2 to ∼1 mM and loaded into a vessel fitted with a rubber septum. The solution was cooled to −10 °C in an ice/acetone bath. Dioxygen was gently bubbled into the solution, resulting in a color change from pale orange to dark blue that signaled formation of 6b.

UV-visible Spectroscopy

UV-vis spectra were recorded on a Hewlett-Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer. Low temperature UV-vis experiments were performed with a custom made quartz cuvette, 1 cm path length, fused into a vacuum jacketed dewar. A solution of 6a, 1.1 mM in CH2Cl2 (6 mL), under N2 was cooled to −10 °C. Dry O2 was gently purged through the solution for 30 s, and the UV-vis spectra were recorded at various time intervals.

EPR Spectroscopy

EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Model 300 ESP X-band spectrometer operating at 9.42 GHz. Temperatures were maintained with an Oxford Instruments liquid helium EPR 900 cryostat. X-band EPR samples were prepared by making a 0.513 mM solution of 6a in CH2Cl2. Aliquots of ∼300 μL were transferred to the EPR tubes in the drybox; the tubes were septum-sealed. One of the samples was frozen at 77 K. Another was cooled to 4 °C under N2, treated with O2 for 45 s, and then frozen at 77 K.

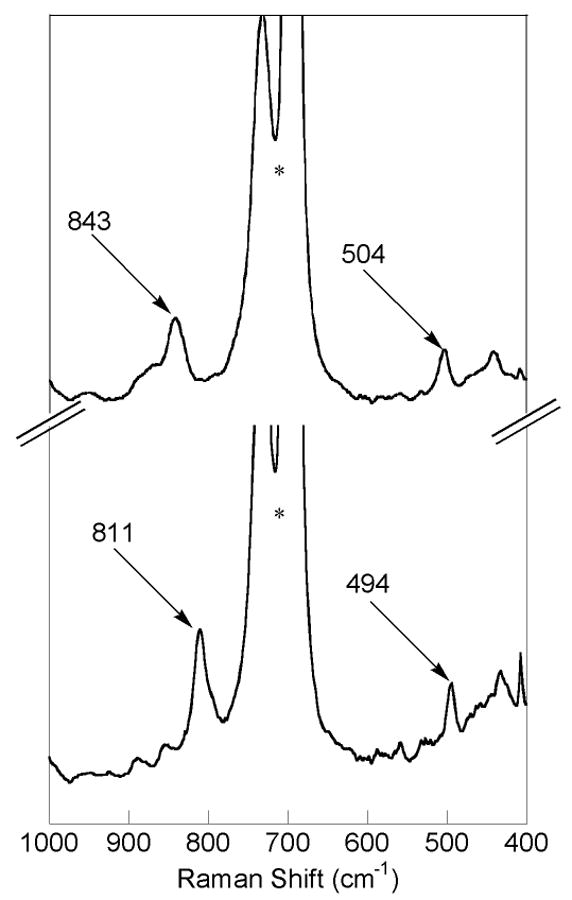

Resonance Raman Spectroscopy

Solutions of 6a in a J-Young NMR tube were oxygenated with either 16O2 or 18O2 at −78 °C and subsequently warmed to room temperature for the measurement. The sample was excited at 647.1nm using a Coherent Innova 90C Kr+ ion laser. Plasma lines for the laser were rejected using a holographic band pass (Kaiser Optical) to obtain a clean background. Approximately 16 mW were focused to a ∼100 μm spot. The resulting Raman light was filtered with a holographic notch filter (Kaiser Optical Systems) to attenuate the Rayleigh scattered light and focused into a 150 μm slit of a single stage spectrograph(An Acton Spectro Pro SP300i). The spectrograph has a 300 mm focal length and is equipped with a 1200 grooves/nm grating giving a linear dispersion of 2.7 nm/mm. The spectral resolution is approximately 5.8 cm-1. Spectra were recorded on a thermoelectrically-cooled back-illuminated CCD. Cooling the CCD to −70 °C significantly reduces the dark current (< 0.1 e/p/s).

Prior to each measurement, the Raman system was initially optimized using frozen CH2Cl2. The exposure time was adjusted to yield a signal with ∼ 40,000 counts per accumulation, and the total number of exposures taken was adjusted to yield a 5 min gathering. Methylene chloride bands at 1156 cm-1, 897 cm-1, 704 cm-1, and 286 cm-1 were used as a wavelength calibration standard. The sample concentrations were between 2 – 4 mM, and each measurement was made on more than one freshly prepared sample and in triplicate to ensure the authenticity of the results. Data were processed by using WinSpec 3.2.1 (Princeton Instruments, Inc.), and the resultant ASCII files were further manipulated using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Diiron(II) Complexes with 2-Diphenylphosphinopyridine as the N-donor Ligand: [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-Ph2Ppy)] (1) and [Fe2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)3(O2CAr4-FPh)(2-Ph2Ppy)] (3)

Compounds 1 and 3 were prepared by displacement of THF from [Fe2(μ-O2CArR)2(O2CArR)2(THF)2] with 2-Ph2Ppy, Scheme 1, where R = Tol and 4-FPh, respectively. The structure of 1 was previously reported, but for comparison purposes selected bond lengths and angles are provided in Table 1.28Figures 1 and S1 show the structure of 3, and Table 1 lists selected bond lengths and angles. The solid state structures of 1 and 3 reveal triply carboxylate-bridged diiron(II) centers with Fe…Fe separations of 3.3094(6) and 3.4517(9) Å, respectively. A fourth chelating carboxylate is bound to one of iron atoms to complete its coordination sphere. On the other metal center, the 2-Ph2Ppy coordinates through the pyridine nitrogen atom. The Fe…P distance is longer in 3, 2.9551(13) Å, than in 1, 2.8322(7) Å. The IR spectrum of 3, displayed in Figure S7, exhibits features associated with aromatic and carboxylate groups. In addition, the C–F stretches originating from the -O2CAr4-FPh ligands are visible at 1221 cm-1.39

Scheme 1.

Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Diiron(II) Complexes with Pendant Sulfur-Containing Substrates [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-PhSpy)] (2), [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-MeSpy)] (4), and [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(2-MeS(O)py)2] (5)

Compounds 2 and 4 differ only in the sulfide substituent. Combination of 2-PhSpy or 2-MeSpy with [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(THF)2] led to the isolation of [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-PhSpy)] (2) or [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-MeSpy)] (4), respectively (Scheme 2). The structure of 2 was previously reported, but for comparison purposes selected bond lengths and angles are provided in Table 1.28 The structure of 4 is shown in Figures 1 and S2, and selected bond lengths and angles are provided in Table 1. Both 2 and 4 contain triply carboxylate-bridged diiron(II) centers with Fe…Fe separations of 3.2712(8) and 3.2496(7) Å, respectively. The Fe…S distance is longer in 2, 3.0897(9) Å, compared to 2.9091(10) Å in 4. A fourth bidentate carboxylate ligand completes the metal coordination sphere of the iron atom not bound to a pyridine moiety.

Scheme 2.

Bright red crystals of 5 were obtained from the reaction of [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(THF)2] with 2-MeS(O)py, Scheme 2. Figures 1 and S3 show the structure of 5, and selected bond lengths and angles are tabulated in Table S2. The compound is a doubly carboxylate-bridged diiron(II) species with an Fe…Fe separation of 4.585(3) Å. The coordination sphere of each iron atom is completed by an additional bidentate carboxylate ligand and an N-donor 2-MeS(O)py ligand that is ligated through both the N and O atoms, rendering each iron atom 6-coordinate. A five-membered ring is formed involving Fe1-N1-C1-S1-O1, with an Fe1–O1 distance of 2.234(5) Å. A comparison of the IR spectra of 4 and 5 (Figure S8) shows the vibrations of two compounds to be nearly identical, with the exception of the S=O stretch at 1008 cm-1 in 5.39

Isolation of Mononuclear [Fe(O2CArTol)2(2-HSpy)2] (6a)

Combining one equiv of [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(THF)2] with 4 equiv of 2-HSpy, as indicated in Scheme 2, resulted in the formation of the mononuclear iron(II) complex, [Fe(O2CArTol)2(2-HSpy)2] (6a). Its structure is shown in Figures 1 and S4 and selected bond lengths and angles are provided in Table S3. This pseudo-tetrahedral iron(II) complex is coordinated by two monodentate carboxylates and two thioamides bound to the metal center through the sulfur atoms. The largest of the metal-centered bond angles is the O–Fe–O angle of 133.35(9)° and the smallest is the S–Fe–S angle of 92.04(2)°. The other four angles are closer to the ideal tetrahedral value of 109.5°, averaging 105.96(6)°. There is hydrogen bonding between the non-coordinated carboxylate oxygen atoms and the thioamide protons at distances of 2.767(14) Å for O1…N1 and 2.709(18) Å for O3…N2. The characteristic S–H stretching absorption in the range of ∼2600 − 2550 cm-1 is absent from the solid state IR spectrum of 2, depicted in Figure S9, but the N–H modes are observed at 3196 cm-1.39 This result is consistent with the X-ray structure.

Mössbauer Spectroscopic Properties of 3

The Mössbauer spectrum, measured at 4.2 K, of a solid sample of 3 is pictured in Figure S10. Although the two iron(II) sites differ in coordination environment, there is no evidence for two overlapping signals. The single sharp quadrupole doublet (Γ = 0.37 – 0.39 mm s-1) reveals that the iron centers are indistinguishable by Mössbauer spectroscopy. The quadrupole splitting (ΔEQ = 2.66(2) mm s-1) and isomer shift (δ = 1.22(2) mm s-1) parameters are consistent with those of high-spin iron(II) complexes having oxygen-rich coordination environments, indicating that 3 has a high spin S = 2 ground state.23,40

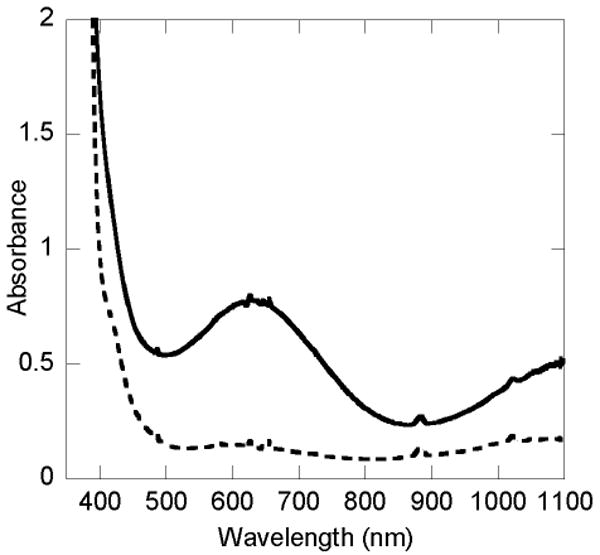

Reactions of 6a with Dioxygen

When a CH2Cl2 or toluene solution of 6a reacts with dioxygen at −10 °C, a deep blue intermediate (6b) develops over a period of 10 min. Absorptions in the UV-vis spectrum, presented in Figure 4, include maxima at 378 nm (ε = 3000 M-1 cm-1), 627 nm (ε = 800 M-1 cm-1), and >1100 nm (ε ∼ 500 M-1 cm-1). Both the ferrous starting material, 6a, and the blue intermediate, 6b, are EPR silent.

Figure 4.

UV-vis spectra of [Fe(O2CArTol)2(2-HSpy)2] (1a) (---) and the intermediate 1b (—) in CH2Cl2 at −10 °C.

Resonance Raman spectroscopy revealed that 6b contains bound oxygen. Characteristic resonances observed in the Raman spectra of (μ-peroxo)diiron(III) moieties arise from O–O (800 – 900 cm-1) and Fe–O (450 – 550 cm-1) stretching vibrations.23,41,42 Raman spectra were obtained for 6b in CH2Cl2 at room temperature. Upon excitation at 647.1 nm, two Raman active bands appear at 843 and 504 cm-1. These features are absent both in Raman spectra of 6a and the decomposition product of 6b. When the blue intermediate is prepared by reacting 6a with 18O-labeled dioxygen (6b*), the peak positions shift to 811 and 494 cm-1. A comparison of the two spectra is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Resonance Raman spectra of a CH2Cl2 solution of 1b derived from the oxygenation [Fe(O2CArTol)2(2-Hspy)2] (6a) with 16O2 (top spectrum) and 18O2 (bottom spectrum). The asterisk indicates a solvent band.

Tethered Ligand Oxidation in 2, 4 and 5

Oxidation of the substrates appended to the N-donor ligand was investigated by product analysis following introduction of O2 into solutions of 2, 4, and 5. A summary of the conditions and amount of oxidation product recovered is provided in Table 3. A pale yellow CH2Cl2 solution of 4 reacts with dioxygen at room temperature and immediately turns golden brown. Workup of the mixture and analysis by GC-MS revealed 58% conversion to 2-pyridylmethylsulfoxide (2-MeS(O)py). The unmodified sulfido ligand was quantitatively recovered. The peaks were assigned by comparing the retention times of the M+ = 125 and 141 signals with those of authentic samples of 2-methylthiopyridine and 2-methylpyridylsulfoxide. No other products, such as the corresponding pyridylsulfones, were evident in the GC traces. The analogous oxidation of 2, analyzed by GC-MS, converts only 29 % of the sulfide to the sulfoxide.28

Table 3.

Summary of the Conditions and Amount of Oxidation Product Isolated for the Reaction of Compounds 2, 4, and 5 with Dioxygen in CH2Cl2.

| Compound | [Fe2] (mM) | Reaction Time (h) | % Oxidized Ligand Recovereda |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 8.6 | 1.5 | 29 |

| 4 | 8.2 | 1.5 | 58 |

| 5 | 5.1 | 16 | 40 |

Based on [Fe2]

The bright red CH2Cl2 solution of 5 becomes dark red-brown upon exposure to dioxygen. Analysis of the products using GC-MS revealed 40% conversion of the 2-MeS(O)py to the sulfone, based on 5. This assignment was confirmed by comparison of the M+ = 157 signal in the GC-MS with an authentic sample of 2-MeS(O)2py. The remaining material recovered was identified as unaltered pyridylsulfoxide ligand.

Stoichiometric and Catalytic Phosphine Oxidation of the Tethered Phosphine Unit in 1 and 3

Oxidation of the diphenylphosphino group appended to the pyridine ligand was investigated by product analysis following introduction of dioxygen into solutions of 1 and 3. Quantitative formation of 2-Ph2P(O)py occurs within 30 min after exposure of 1 to dioxygen,28 and the same conversion occurs in the corresponding reaction of 3 in 30 min, with quantitative recovery of the pyridine ligand. Control experiments established that, in the absence of 3, neither O2-saturated CH2Cl2 nor the workup process induced ligand oxidation over the same time interval (∼ 1 h). 31P NMR spectroscopy with Ph3PO as an internal standard was used to analyze the products of the reaction and monitor the recovery of all species.

Catalytic formation of 2-Ph2P(O)py ensues when a CH2Cl2 solution of 1 is supplied with additional equivalents of 2-Ph2Ppy. Results from several experiments show that 4 equiv are converted in an hour and slightly more than 13 equiv over a period of 12 h at a metal complex concentration of 1.5 mM. A 5-fold dilution of the concentration of 1 leads to 17 equiv being oxidized in 17 h. When a phosphine that did not contain a pendant coordinating ligand, such as triphenylphosphine, is added to the reaction mixture, the extent of oxidation is >20-fold less than that from the 2-pyridyl-derivatized phosphine ligand under the same conditions. Catalytic oxidation is not observed to the same degree in MeCN or C6H6. In both cases, 2 equiv of 2-Ph2Ppy are converted to the phosphine oxide overnight. When a CH2Cl2 solution of 3 is provided with more of the pyridine ligand, catalytic phosphine oxidation similarly transpires. A 14 h reaction resulted in conversion of 3 out of almost 9 equiv of 2-Ph2Ppy to the phosphine oxide. This result is comparable to the 13 out of 50 equiv of 2-Ph2Ppy oxidized under the same conditions by the corresponding -O2CArTol complex, 1. A summary of the reaction conditions used and the products recovered is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of Conditions and Amount of Oxidation Product Isolated for the Reaction of 1 and 3 with Additional Equivalents of Phosphine and Dioxygen

| [Fe2] (mM) | Compound | Equiv 2-Ph2Ppy Added | Reaction Time (h) | Equiv 2-Ph2P(O)py Recovereda |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 1 | 8.44 | 1 | 3.98 |

| 1.4 | 1 | 47.0 | 13 | 13.4 |

| 0.31 | 1 | 51.5 | 17 | 17.0 |

| 3.2 | 3 | 8.55 | 17 | 2.95 |

|

| ||||

| Equiv PPh3 Added | Equiv (O)PPh3 Recovered | |||

|

| ||||

| 0.42 | 1 | 5.62 | 14 | 0.70 |

Including 1 equiv of 2-Ph2Ppy from [Fe2].

Isolation and Structural Characterization of Iron(III) Complexes [ F e6(μ4-O)2(μ-OH)6(μ-O2CArTol)4Cl4(2-Ph2P(O)py)2] (7) and [Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)(O2CAr4-FPh)3(OH2)(2-Ph2P(O)py)] (8)

The hexairon(III) species 7 was isolated as one of the final products from the reaction of 1 with dioxygen (Scheme 2). The structure is best described by the diagrams in Figures 2 and S5, and a list of selected interatomic distances and angles is included in Table S4. The structure of 7 consists two (μ3-oxo)triiron(III) units that are related by an inversion center and linked through two O2-, two OH-, and two -O2CArTol bridging groups. Four octahedral and two distorted trigonal bipyramidal iron(III) sites result. A noteworthy feature in the structure of 1 is that two octahedral and two trigonal bipyramidal iron centers are coordinated by chloride ions. Their origin is thought to be a result of solvent oxidation, because no comparable material could be obtained when toluene was used as a solvent for this reaction. The two outside iron centers are bound to 2-Ph2P(O)py, the oxidized N-donor ligand, through the oxygen atom of the phosphine oxide.

Figure 2.

ORTEP drawing of [Fe6(μ4-O)2(μ-OH)6(μ-O2CArTol)4Cl4(2-Ph2P(O)py)2] (7) illustrating 50% probability thermal ellipsoids for all non-hydrogen atoms. The aromatic rings of the -O2CArTol ligands are omitted for clarity.

Pentane diffusion into the yellow-orange CH2Cl2 or toluene solution generated upon oxygenation of 3 afforded [Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)(O2CAr4-FPh)3(OH2)(2-Ph2P(O)py)] (8) (Scheme 1) in 25% yield. The structure of 8 is depicted in Figures 3 and S6, and selected interatomic distances and angles are listed in Table 2. Two distorted octahedral iron(III) atoms are bridged by two hydroxides and one carboxylate ligand. The largest deviations from ideal 90° interbond angles are 11.60(2)° and 12.15(2)° for Fe1 and Fe2, respectively, and occur at the O–Fe–O angle of the bent four-membered Fe2(μ-OH)2 ring. The Fe1–O2–Fe2 unit has Fe1–O2 and Fe2–O2 distances of 1.954(4) and 1.981(4) Å, respectively, and a 98.10(19)° bridging angle. The Fe–O bond lengths in the Fe1–O3–Fe2 unit are slightly longer at 1.981(4) and 1.977(4) Å for Fe1–O3 and Fe2–O3, respectively, but the bridging angle is smaller, 97.35(18)°. The longest Fe–O distances are those to the oxygen atoms of the bridging carboxylate ligand, 2.003(3) and 2.017(3) Å. The Fe…Fe separation of 2.972(1) Å is similar to those reported for the {Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CR)}3+ core in the resting state of MMOHox43,44 and two other synthetic analogues.21,24,45

In addition to the bridging ligands, one iron atom (Fe1) is coordinated by a monodentate carboxylate oxygen. The other two coordination sites are occupied by O- and N-atoms from the oxidized N-donor ligand, 2-Ph2P(O)py, generating a five-membered Fe1-N1-C1-P1-O1 ring. The other iron center (Fe2) has two monodentate carboxylate ligands and a coordinated water molecule to complete its coordination sphere. Notwithstanding the bridging hydroxide groups, the three monodentate carboxylate ligands provide the shortest Fe–O distances, 1.947(3), 1.974(3), and 1.976(3) Å. The Fe–O bond to the terminally bound water molecule is longer than to the O-atom of 2-Ph2P(O)py, 2.099(4) vs 2.023(3) Å. The Fe–N distance of 2.210(4) Å is ∼0.1 Å longer than that in the diferrous starting material, 3.

The three terminal carboxylate ligands are involved in hydrogen bonding interactions with the bridging hydroxides, O2…O10, 2.712(5) Å and O3…O8, 2.801(6) Å, and the coordinated water molecule, O4…O12, 2.537(5) Å. The IR spectrum of 8, depicted in Figure S7, shows the hydrogen-bonded and non-hydrogen-bonded hydroxide stretches as a broad band centered around 3400 cm-1 and a sharper peak at 3572 cm-1, respectively.39

Mössbauer Spectroscopic Properties of 8

The Mössbauer spectrum, recorded 4.2 K, of a solid sample of 8 is presented in Figure 6. A single sharp quadrupole doublet is observed (δ = 0.50(2) mm s-1, ΔEQ = 0.83(2) mm s-1). The isomer shift (δ) falls in the range typical of the high-spin Fe(III) complexes.46,47 Although the two iron(III) sites differ, having O6 and NO5 donoratom sets, there is no evidence for two overlapping doublets. The line widths (Γ = 0.31 – 0.32 mm s-1) are close to natural line widths, indicating that the two ferric atoms are indistinguishable by Mössbauer spectroscopy.

Figure 6.

Zero-field Mössbauer spectrum (experimental data (|), calculated fit (–)) recorded at 4.2 K for [Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CAr4-FPh)(O2CAr4-FPh)3(2-Ph2P(O)py)(OH2)] (8) in the solid state. See text for derived Mössbauer parameters.

Bond Valence Sum Analysis of 7 and 8

The bond valence sum (BVS) is an empirical quantity that has been used to determine the oxidation state of metal ions in coordination complexes based on crystallographically determined metal-ligand bond distances.48 Bond valences, sij between cation i and anion j, are calculated according to eq 1, where r is the observed bond distance and ro and B are empirically determined parameters. The summation of the bond valences for a particular metal cation yields the oxidation state, Vi. Bond valence sum analysis of both 7 and 8 supports the assignment of the six metal centers in 7 and the two in 8 as iron(III). The calculation of the individual bond valences as well as their summation is available in Table S5.

| (1) |

Discussion

In addition to methane to methanol, MMOH can accept a variety of oxidizable substrates including methanethiol.3 We therefore investigated 2-mercaptopyridine as an ancillary ligand at the oxygen-rich core of the m-terphenyl carboxylate diiron(II) complexes. MMOH also catalyzes the conversion of sulfides to sulfoxides, amines to amine oxides, and olefins to epoxides.3,6 The first of these transformations inspired the selection of 2-phenylthiopyridine and 2-methylthiopyridine as N-donor ligands. Although as yet unprecedented in the natural system, the oxidation of dimethylsulfoxide is thermodynamically more favorable than that of dimethylsulfide,49 so 2-pyridylmethysulfoxide was installed at the {Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2} core. The oxidation of triphenylphosphine is even more thermodynamically facile, ΔH° being −67 kcal/mol vs −33 kcal/mol for dimethyl sulfide.49 Although not a known substrate of the native enzyme, this potentially more reactive species was provided as a 2-diphenylphosphinopyridine ancillary ligand in the carboxylate-rich diiron(II) centers to gain further insight into the chemistry.

Despite the differing substituents on the pyridine and carboxylate ligands, the iron atoms in 1 – 4 have nearly identical coordination environments. It was initially thought that steric bulk provided by diphenylphosphino and phenylthio moieties at the ortho position of the pyridine ring was responsible for only one pyridine ligand being accommodated at the diiron cores in 1 – 3. Such also proved to be the case in 4, however, where the heteroatom substituent is a less sterically demanding methyl group. In all four structures the Fe–O bonds of the three bridging carboxylate ligands are on average 0.05 Å shorter for the iron atom to which the pyridine moiety is coordinated, 2.0191(12) vs 2.0485(13) Å in 1, 1.9903(15) vs 2.0453(16) Å in 2, 2.002(3) vs 2.024(3) Å in 3, and 1.994(2) vs 2.044(2) Å in 4. The Fe–O bonds of the terminal carboxylate ligand are the longest and asymmetric, being ∼2.07 and ∼2.25 Å. This result reflects the greater electron releasing character of a pyridine N-donor compared with a bidentate carboxylate, since the lower-coordinate iron atom would be expected to have the shorter bond lengths, all other things being equal.

When 2-MeS(O)py rather than 2-MeSpy was employed as the N-donor ligand, a more open, doubly carboxylate-bridged structure is adopted for the resulting diiron(II) complex 5. Two N-donors are now accommodated, compared to only one in the triply-bridged complexes 1 – 4. The four Fe–O bond distances range from 1.961(5) to 2.267(5) Å. The Fe…Fe distance of 4.585(3) Å in 5 is >1 Å greater than those observed in the triply-bridged structures 1 – 4 of ∼3.3 Å and quite long, reflecting the syn,anti binding mode of the bridging carboxylates.50

Instead of the carboxylate-bridged dimetallic unit anticipated upon displacement of the THF molecules in [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(THF)2] by 2-mercaptopyridine, a mononuclear species is isolated. The Cambridge Structural Database reports no other structures of four-coordinate iron containing only sulfur and oxygen ligands; 6a appears to be the first. The hydrogen bonding between the carboxylate oxygen atoms and the thioamide protons is most likely stabilizing this unique mononuclear structure. The iron atom is coordinated by a thioamido ligand, the tautomer of 2-mercaptopyridine (Scheme S1), in which the nitrogen atom is protonated and a carbon-sulfur double bond is present. The C1–S1 and C6–S2 distances of 1.716(3) and 1.717(3) Å are characteristic of C=S double bonds,51 and the bond lengths of the pyridine ring similarly reflect this assignment.

A single sharp quadrupole doublet occurs in the Mössbauer spectrum of 3, the quadrupole splitting (ΔEQ = 2.66(2) mm s-1) and isomer shift (δ = 1.22(2) mm s-1) values of which are consistent with those of high spin diiron(II) complexes in oxygen-rich coordination environments.23 The isomer shift is among the lowest reported for five-coordinate, and slightly higher than those observed for four-coordinate, iron(II) sites (1.0 – 1.1 mm s-1).52 The quadrupole splitting and isomer shift parameters obtained for 3 are slightly lower than those of MMOHred, 3.01 and 1.3 mm s-1, respectively.52 This disparity is ascribed to fewer nitrogen ligands for 3 compared to the MMOHred active site.

Clues to the identity of the blue intermediate observed upon oxygenation of 6a are provided by resonance Raman and EPR spectroscopic measurements. The electronic absorption spectrum of 6b is similar to those of paramagnetic FeIIFeIII cations formed by other {Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)4} systems, which display intervalence charge transfer transitions and have a characteristic g = 10 signal in their EPR spectra.53 However, both the ferrous starting material, 6a, and the blue intermediate, 6b, are EPR silent. The UV-vis spectrum of the latter also resembles those of (μ-peroxo)diiron(III) units in both synthetic analog and biological systems.11,23,54-58 Although 6a is a mononuclear compound, oxygenation of mononuclear iron(II) can result in diiron(II) complexes, possibly via an {Fe2(O2)} intermediate.45 Theoretically from a simple harmonic oscillator calculation the downshift upon 18O2-labeling (Δ18O) should be −48 cm-1 for an O–O stretch and −23 cm-1 for the Fe–O stretch. For 6b the Δ18O values are slightly less (−32 cm-1, −10 cm-1) for the O–O and Fe–O vibrations, respectively, suggesting coupling with other modes in the molecule or possibly an Fe–O–O–X unit.

Oxidation of diphenyl sulfide is slightly more energetically favorable than oxidation of dimethyl sulfide (ΔH° −36 vs −33 kcal/mol),59,60 which is inconsistent with greater conversion of 2-MeSpy (58 %) than 2-PhSpy (29%) to the sulfoxide in 4 and 2, respectively. The higher activity of 4, despite its carrying the less energetically favorable substrate, may be a result of increased access to the O2-activated at the diiron center because of the smaller methyl substituent compared to the phenyl group of 2-PhSpy in 2.

In a study involving Δ9-desaturase, which has a carboxylate-bridged diiron site similar to that in MMOH,43,61,62 reaction of 10-thiasterarate-ACP with the reconstituted soluble stearoyl-ACP Δ9-desaturase complex produced the 10-sulfoxide as the sole product.63 The comparable reaction with 9-thiasearoyl-ACP desaturase, however, gave the 9-sulfoxide as ∼5% of the total products. It was concluded that the relative reactivity of the 9- and 10-thia-substituted acyl-ACPs is controlled by the proximity of two positions to the O2-activated diiron center in the transition state. The reactivity of compound 4 supports this view. Exposure of 4 to dioxygen leads only to the formation of the sulfoxide. No C–H bond activation of the methyl substituent was observed. Oxidation of an ethyl moiety tethered to pyridine in [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(2-Etpy)2] affords only α-methyl-2-pyridinemethanol, a result that also may be a consequence of proximity to the O2-activated diiron center.27

Although the two iron atoms in 5 are coordinatively saturated, the compound readily reacts at room temperature following exposure to dioxygen. The observed ligand oxidation may require carboxylate shifts or partial dissociation of the sulfoxide ligand.21 The 40% conversion of the sulfoxide to the corresponding sulfone is, to the best of our knowledge, unprecedented in small molecule model compounds, but not surprising from a thermodynamic perspective.11,23,64 The ΔH° for oxidation of dimethylsulfide to dimethylsulfoxide is −27 kcal/mol compared to −52 kcal/mol for oxidation of dimethylsulfoxide to dimethylsulfone.49 Despite the fact that compound 5 is more sterically hindered than 4, once dioxygen can access the diiron center and become activated, the ligand oxidation reaction will be more favorable.

The catalytic ligand oxidation exhibited by 1 is difficult to rationalize. Previously we reported the catalytic oxidation of PPh3 in the presence of dioxygen by the diiron(II) complex [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(Me3TACN)2(MeCN)](OTf)2, where Me3TACN = 1,4,7-trimethyl-1,4,7-triazacyclononane.65 This phenomenon was only observed when THF was used as the solvent. Further studies revealed that the corresponding diiron(III) complex, [Fe2(μ-O)(μ-O2CArTol)2(Me3TACN)2](OTf)2, the only detectable iron-containing species during the reaction, could itself promote the catalysis.66 Furthermore, it was determined that phosphine oxidation is coupled to catalytic oxidation of the THF solvent, affording a C–C bond cleavage product, which occurs until the phosphine is consumed. For 1, although autoxidation has not been eliminated, substituting the added 2-Ph2Ppy with PPh3 dramatically decreased the reactivity, >20-fold, which suggests that the metal center not only initiates the catalysis but that substrate binding and intramolecular oxygenation most likely occur. The reactivity of [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)3(O2CArTol)(2-Ph2Ppy)2] also differs from the previous catalytic system because the reaction also occurs in MeCN and C6H6, albeit with lower conversion which we attribute to the limited solubility of the starting diiron(II) complex.

A small difference in the remote carboxylate substituents, -O2CArTol (1) vs -O2CAr4-FPh (3), leads to pronounced differences in dioxygen reactivity. Previous work revealed that carboxylate ligands with p-tolyl substituents form more reactive diiron(II) centers than the p-fluorophenyl analogs, for both 2-benzyl- and 2-ethylpyridine derivatives.27 This situation also obtains for the present 2-diphenylphosphinopyridine complexes, because 1 catalytically oxidizes five times the amount of phosphine as 3. The steric properties of these two terphenyl carboxylate groups are similar, so the decrease in catalytic activity between the -O2CArTol and -O2CAr4-FPh systems is attributed to electronic factors. The pKa values of HO2CAr4-FPh and HO2CArTol are 6.14 and 6.50, respectively,67 but there are four such ligands, which may be sufficient to alter the properties of the O2-generated, catalytically active species and decrease the turnover number.

The effect of different carboxylates is also manifest in the results of oxygenation reactions of 1 and 3, as measured by the final product isolated. Whereas oxidation of 3 leads to the formation of a discrete dinuclear {Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CR)}3+ core, a hexanuclear complex, 7, is recovered from the reaction of 1 with O2. Most notably, the structure of 7 contains coordinated chloride ions. Decomposition of the solvent, CH2Cl2, could generate Cl-, which may drive the formation of the hexanuclear compound 7. An analogous hexanuclear complex with coordinated chloride ligands was isolated following oxygenation of [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)4(4-CNpy)2], where 4-CNpy is 4-cyanopyridine.52 Oxidation of CH2Cl2 also occurs in MMOH,3 the product formed being unstable and decomposing to formaldehyde and HCl, so the present results may relate to the enzyme system. Solvent oxidation by 1 would provide the chloride ions observed in the final species isolated, 7. Our observations of increased C–H activation with more electron releasing ligands at the diiron(II) center suggests that the MMOH active site may be similarly activated.

The synthesis of complexes with a {Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CR)}3+ core has been challenging because of the tendency of iron(III) salts to form oligo- or polynuclear clusters. The first such compound to be isolated, [Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CArTol)(O2CArTol)3(N-Bnen)(N,N-Bn2en)] (9), was generated by oxygenation of [Fe2(μ-O2CArTol)2(O2CArTol)2(N,N-Bn2en)2].24,25 This approach mimics the chemistry occurring at the enzyme active sites. A second route to the {Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CR)}3+ core was discovered during oxygenation of mononuclear [Fe(O2CArTol)2(Hdmpz)2], where Hdmpz is dimethylpyrazole, which afforded [Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CArTol)(O2CArTol)(OH2)(Hdmpz)2] (10).45 Representations of 9 and 10 are provided in Chart S1. In the present work, exposure of 3 to dioxygen led to 8, which has the {Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CR)}3+ unit and is only the third structural mimic of the MMOHox core structure. There was no evidence for solvent oxidation in this reaction. The Fe…Fe and Fe–Ohydroxide distances of 2.972(1) and 1.954(4) – 1.981(4) Å, respectively, in 8 are similar to those of MMOHox, in which the Fe…Fe distance is 2.99 Å and the Fe–Ohydroxide distances are 1.7 – 2.2 Å.44 In the protein two histidine and three carboxylate terminal ligands, a bridging carboxylate, and solvent-derived molecules complete the NO5 donor-atom sets at each metal. A slightly different ligand combination is adopted by 8, which has an NO5 set for one iron atom and an O6 set for the other. One of the O-donors is a terminally bound water molecule, exactly like that observed in all structurally characterized forms of MMOH to date.43,44 Hydrogen bonding interactions between axial carboxylate ligands and bridging hydroxide ligands in 8 also are observed in MMOHox.43,44

The single sharp quadrupole doublet exhibited in the Mössbauer spectrum of 8 differs from the results obtained for MMOHox from both M. capsulatus (Bath) and M. trichosporium OB3b, both of which have Mössbauer spectra indicating the presence of two slightly inequivalent high-spin iron(III) sites.54,68 The isomer shift (δ = 0.50(2) mm s-1) of 8 falls in the range associated with high-spin Fe(III) complexes,46,47 and is analogous to those reported for MMOHox. As indicated in Table 5, the quadrupole splitting parameter (ΔEQ = 0.83(2 mm s-1) in 8 lies in between that of the structurally related compounds 9 and 10.24,45 Their Mössbauer parameters, along with those of 8, are compared to values of MMOHox in Table 5. The ΔEQ values obtained for these three compounds are significantly different, despite similar octahedral coordination geometries at the iron(II) sites. Most reported hydroxo-bridged diiron(III) complexes have quadrupole splitting values ∼0.5 mm s-1.46 Notably, 8 and 10 have more O-rich coordination environments than 9, with a H2O (O-donor) ligand instead of an N-donor ligand on the second iron atom. The {Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CR)}3+ core in MMOHox, which also has one terminally bound water molecule,43,44 displays the similar ΔEQ values, 0.79(3), 1.12(3) mm s-1 and 0.87, 1.16 mm s-1 for M. capsulatus (Bath) and M. trichosporium OB3b, respectively.54,68 An O-rich metal coordination environment may be the source of the similar ΔEQ (∼1 mm s-1) values in 8, 10, and the diiron sites of MMOHox.

Table 5.

Mössbauer Parameters for 8, 9, 10, and MMOHox

| Coordinate Atoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe1 | Fe2 | δ (mm s-1) | ΔEQ (mm s-1) | ref | |

| 8 | NO5 | O6 | 0.50(2) | 0.83(2) | a |

| 9 | N2O4 | NO5 | 0.48(2) | 0.61(2) | 24 |

| 10 | NO5 | O6 | 0.45(2) | 1.21(2) | 45 |

| MMOHox | NO5 | NO5 | 0.51(2), 0.50(2)b | 0.79(3), 1.12(3)b | 54 |

| 0.50, 0.51c | 0.87, 1.16c | 68 | |||

This work.

M. capsulatus (Bath).

M. trichosporium OB3b

Conclusion

Tethered thiol, sulfide, sulfoxide, and phosphine moieties on pyridine ligands serve as excellent substrates for oxidation at O2-activated, carboxylate-bridged diiron(II) centers. Intramolecular oxidation of the heteroatoms in these groups further demonstrates that proximity is important for oxidation. Only the group adjacent to the diiron center is oxidized, since no methyl group oxidation occurred for the case of 2-methylthiopyridine complex. The reactivity of these compounds is not only affected by the N-donor ligand, but also by the remote substituents on the carboxylate ligands. The more electron-releasing carboxylate groups showed increased C–H activation, in agreement with results for related systems having tethered benzyl- and ethylpyridine ligands.27 When the less electron-releasing carboxylate group was used, subsequent solvent oxidation did not occur; instead, the {Fe2(μ-OH)2(μ-O2CR)}3+core of MMOHox was recovered having structural and Mössbauer spectroscopic properties analogous to those observed in the enzyme. These observations provide valuable information to guide future work on more advanced MMOH synthetic analogs.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information Available. Table S1 summarizing X-ray crystallographic information for 3 – 8; Tables S2, S3, and S4 providing geometric parameters for 5, 6, and 7; Table S5 describing bond valence sum analyses for 7 and 8; Chart S1 picturing 9 and 10; Scheme S1 picturing the tautomer of 2-mercaptopyridine; Figures S1 – S6 showing ORTEP diagrams of 3 – 8; Figures S7 – S9 containing FT-IR spectra of 3 – 6 and 8; Figure S10 illustrating Mössbauer data and fits for 3; and corresponding X-ray crystallographic files in CIF format for 3 – 8. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant GM-32134 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Raman spectra were obtained at the George R. Harrison Spectroscopy Lab Raman Facilities supported by NIH under the Biomedical Research Technology Program (P41RR02594) and by NSF Grant 0111370-CHE. We thank Ms. Mi Hee Lim for assistance with the 18O2-labeling experiments, Ms. Liz Nolan and Dr. Joe Gardecki for performing the resonance Raman experiments, Dr. Peter Müller for assistance with X-ray crystallography, and Dr. Sungho Yoon for help in acquiring the Mössbauer spectra.

References

- 1.Erwin DP, Erickson IK, Delwiche ME, Colwell FS, Strap JL, Crawford RL. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:2016–2025. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.4.2016-2025.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vardar G, Wood TK. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:3253–3262. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3253-3262.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colby J, Stirling DI, Dalton H. Biochem J. 1977;165:395–402. doi: 10.1042/bj1650395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green J, Dalton H. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17698–17703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox BG, Borneman JG, Wackett LP, Lipscomb JD. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6419–6427. doi: 10.1021/bi00479a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuse H, Ohta M, Takimura O, Murakami K, Inoue H, Yamaoka Y, Oclarit JM, Omori T. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1998;62:1925–1931. doi: 10.1271/bbb.62.1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feig AL, Lippard SJ. Chem Rev. 1994;94:759–805. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallar BJ, Lipscomb JD. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2625–2657. doi: 10.1021/cr9500489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merkx M, Kopp DA, Sazinsky MH, Blazyk JL, Müller J, Lippard SJ. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2001;40:2782–2807. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010803)40:15<2782::AID-ANIE2782>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baik MH, Newcomb M, Friesner RA, Lippard SJ. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2385–2419. doi: 10.1021/cr950244f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kryatov SV, Rybak-Akimova EV. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2175–2226. doi: 10.1021/cr030709z., and refs cited therein.

- 12.Que L, Jr, Dong Y. Acc Chem Res. 1996;29:190–196. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Que L., Jr J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1997:3933–3940. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Bois J, Mizoguchi TJ, Lippard SJ. Coord Chem Rev. 2000;200–202:443–485. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippard SJ. Chemistry in Britain. 1986;22:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lippard SJ. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1988;27:344–361. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee D, Sorace L, Caneschi A, Lippard SJ. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:6774–6781. doi: 10.1021/ic010726b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandal SK, Young VG, Jr, Que L., Jr Inorg Chem. 2000;39:1831–1833. doi: 10.1021/ic9912676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herold S, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:145–156. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldberg DP, Telser J, Bastos CM, Lippard SJ. Inorg Chem. 1995;34:3011–3024. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee D, Lippard SJ. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:2704–2719. doi: 10.1021/ic020186y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tolman WB, Que L., Jr J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 2002:653–660. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tshuva EY, Lippard SJ. Chem Rev. 2004;104:987–1012. doi: 10.1021/cr020622y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee D, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:4611–4612. doi: 10.1021/ja0100930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee D, Lippard SJ. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:827–837. doi: 10.1021/ic011008s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon S, Lippard SJ. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:8606–8608. doi: 10.1021/ic0350133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carson EC, Lippard SJ. 2005 Manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carson EC, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3412–3413. doi: 10.1021/ja031806c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pangborn AB, Giardello MA, Grubbs RH, Rosen RK, Timmers FJ. Organometallics. 1996;15:1518–1520. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furukawa N, Ogawa S, Matsumura K, Fujihara H. J Org Chem. 1991;56:6341–6348. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newkome GR, Hager DC. J Org Chem. 1978;43:947–949. [Google Scholar]

- 32.SMART v5.626: Software for the CCD Detector System. Bruker AXS; Madison, WI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuzelka J, Mukhopadhyay S, Spingler B, Lippard SJ. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:6447–6457. doi: 10.1021/ic0345976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheldrick GM. SHELXTL97-2: Program for Refinement of Crystal Structures. University of Göttingen; Germany: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.SHELXTL v5.10: Program Library for Structure Solution and Molecular Graphics. Bruker AXS; Madison, WI: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheldrick GM. SADABS: Area-Detector Absorption Correction. University of Göttingen; Germany: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spek AL. PLATON, A Multipurpose Crystallographic Tool. Utrecht University; Utrecht, The Netherlands: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kent TA. WMOSS v2.5: Mössbauer Spectral Analysis Software. WEB Research Co.; Minneapolis: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silverstein RM, Webster FX. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. Sixth. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Münck E. In: Physical Methods in Bioinorganic Chemistry: Spectroscopy and Magnetism. Que L Jr, editor. University Science Books; Sausalito, CA: 2000. pp. 287–319. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chavez FA, Ho RYN, Pink M, Young VG, Jr, Kryatov SV, Rybak-Akimova EV, Andres H, Münck E, Que L, Jr, Tolman WB. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:149–152. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020104)41:1<149::aid-anie149>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costas M, Cady CW, Kryatov SV, Ray M, Ryan MJ, Rybak-Akimova EV, Que L., Jr Inorg Chem. 2003;42:7519–7530. doi: 10.1021/ic034359a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whittington DA, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:827–838. doi: 10.1021/ja003240n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elango N, Radhakrishnan R, Froland WA, Wallar BJ, Earhart CA, Lipscomb JD, Ohlendorf DH. Protein Sci. 1997;6:556–568. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoon S, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:2666–2667. doi: 10.1021/ja031603o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kurtz DM., Jr Chem Rev. 1990;90:585–606. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu T, Lovell T, Han WG, Noodleman L. Inorg Chem. 2003;42:5244–5251. doi: 10.1021/ic020640y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown ID, Altermatt D. Acta Cryst. 1985;B41:244–247. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harlan EW, Berg JM, Holm RH. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:6992–7000. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rardin RL, Tolman WB, Lippard SJ. New J Chem. 1991;15:417–430. [Google Scholar]

- 51.CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Vol. 60 CRC Press, Inc.; Boca Raton, FL: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoon S, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8386–8397. doi: 10.1021/ja0512531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee D, DuBois JL, Pierce B, Hedman B, Hodgson KO, Hendrich MP, Lippard SJ. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:3172–3182. doi: 10.1021/ic011050n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu KE, Valentine AM, Wang D, Huynh BH, Edmonson DE, Salifoglou A, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:10174–10185. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Broadwater JA, Ai J, Loehr TM, Sanders-Loehr J, Fox BG. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14664–14671. doi: 10.1021/bi981839i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Valentine AM, Stahl SS, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:3876–3887. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee SK, Lipscomb JD. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4423–4432. doi: 10.1021/bi982712w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bollinger JM, Jr, Tong WH, Ravi N, Huynh BH, Edmondson DE, Stubbe J. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:8015–8023. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mackle H, O'Hare PAG. Tetrahedron. 1963;19:961–971. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Douglas TB. J Am Chem Soc. 1946;68:1072–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Logan DT, Su XD, Åberg A, Regnström K, Hajdu J, Eklund H, Nordlund P. Structure. 1996;4:1053–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenzweig AC, Nordlund P, Takahara PM, Frederick CA, Lippard SJ. Chem Biol. 1995;2:409–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.White RD, Fox BG. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7828–7835. doi: 10.1021/bi030082e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Punniyamurthy T, Velusamy S, Iqbal J. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2329–2363. doi: 10.1021/cr050523v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tshuva EY, Lee D, Bu W, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2416–2417. doi: 10.1021/ja017890i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moreira RF, Tshuva EY, Lippard SJ. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:4427–4434. doi: 10.1021/ic049460+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen CT, Siegel JS. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:5959–5960. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fox BG, Hendrich MP, Surerus KK, Andersson KK, Froland WA, Lipscomb JD, Münck E. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:3688–3701. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Available. Table S1 summarizing X-ray crystallographic information for 3 – 8; Tables S2, S3, and S4 providing geometric parameters for 5, 6, and 7; Table S5 describing bond valence sum analyses for 7 and 8; Chart S1 picturing 9 and 10; Scheme S1 picturing the tautomer of 2-mercaptopyridine; Figures S1 – S6 showing ORTEP diagrams of 3 – 8; Figures S7 – S9 containing FT-IR spectra of 3 – 6 and 8; Figure S10 illustrating Mössbauer data and fits for 3; and corresponding X-ray crystallographic files in CIF format for 3 – 8. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.