Abstract

The room temperature absorption and emission spectra of the 4-cis and all-trans isomers of 2,4,6,8,10,12,14-hexadecaheptaene are almost identical, exhibiting the characteristic dual emissions S1→S0 (21Ag− → 11Ag−) and S2→S0 (11Bu+ → 11Ag−) noted in previous studies of intermediate length polyenes and carotenoids. The ratio of the S1→S0 and S2→S0 emission yields for the cis isomer increases by a factor of ~15 upon cooling to 77 K in n-pentadecane. In contrast, for the trans isomer this ratio shows a two-fold decrease with decreasing temperature. These results suggest a low barrier for conversion between the 4-cis and all-trans isomers in the S1 state. At 77 K, the cis isomer cannot convert to the more stable all-trans isomer in the 21Ag− state, resulting in the striking increase in its S1→S0 fluorescence. These experiments imply that the S1 states of longer polyenes have local energy minima, corresponding to a range of conformations and isomers, separated by relatively low (2–4 kcal) barriers. Steady state and time-resolved optical measurements on the S1 states in solution thus may sample a distribution of conformers and geometric isomers, even for samples represented by a single, dominant ground state structure. Complex S1 potential energy surfaces may help explain the complicated S2→S1 relaxation kinetics of many carotenoids. The finding that fluorescence from linear polyenes is so strongly dependent on molecular symmetry requires a reevaluation of the literature on the radiative properties of all-trans polyenes and carotenoids.

INTRODUCTION

The optical spectroscopy of short, all-trans polyenes reveals an excited 21Ag− singlet state, into which absorption is forbidden by symmetry, lying at lower energy than the 11Bu+ state responsible for the characteristic strong visible absorption (S0 (11Ag−) → S2 (11Bu+)) in these C2h symmetric, linearly-conjugated π-electron systems.1,2 This explains several distinctive aspects of polyene optical spectroscopy, including the systematic differences in the transition energies of the strong absorption and the fluorescence (S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−)), the anomalously long radiative lifetimes, and the relative insensitivity of the fluorescence spectra to solvent polarizability.2 Theoretical analysis by Schulten and Karplus3 of short, all-trans polyenes rationalized the low lying S1 (21Ag−) state in terms of extensive configuration interaction between singly and multiply excited singlet configurations with the same symmetry. Extensions of this model to longer polyenes and carotenoids predict additional low-lying 1Ag− and 1Bu− excited states4,5, but these other states are not easily detected, either in conventional steady-state or time-resolved spectroscopic measurements.

The theoretical descriptions of all-trans polyene excited states have had considerable influence, not only in interpreting the spectroscopy and photophysics of all-trans polyenes, but also in explaining optical measurements on a variety of less symmetric polyenes and carotenoids. For example, Koyama, et al.6,7 assigned features in resonance Raman excitation profiles and in the fluorescence spectra of long carotenoids to low-lying 11Bu− states. This group also used ultrafast optical spectroscopy to detect transient absorption features, again attributed to the 11Bu− state.8,9 Cerullo et al.10 presented ultrafast spectroscopic evidence for an intermediate singlet state (Sx) in several carotenoids, which they postulated facilitates internal conversion between the S2 (11Bu+) and S1 (21Ag−) states. Van Grondelle and coworkers11 observed a wavelength dependence of the dynamics of spirilloxanthin that was interpreted in terms of another singlet electronic state, S*, thought to be an intermediate in the depopulation of S2 (11Bu+). Fast pump–probe optical techniques were applied to β-carotene by Larsen, et al.12, and the results suggested yet another carotenoid excited state (S‡) formed directly from S2 (11Bu+). The nature of these states remains uncertain, and recent work has called into question the assignments and suggested that at least some of the spectroscopic observations may be attributed to two-photon processes rather than additional electronic states.13,14

Advances in synthetic procedures coupled with improved purification and analytical techniques (HPLC, MS/APCI+, and NMR) have allowed us to revisit the electronic states of simple all-trans dimethyl polyenes and to extend optical experiments to their less symmetric cis counterparts. These studies reveal that the rates of radiative decay from the “S1 (21Ag−)” states of cis polyenes are significantly larger than radiative decay rates from the S1 (21Ag−) states of trans polyenes. Our experiments also suggest that trans ↔ cis conversion readily occurs on the S1 (21Ag−) potential surface. The photochemical formation of cis isomers from trans ground states requires a reevaluation of previous reports of fluorescence from trans polyenes and carotenoids. Many of these studies were carried out prior to the advent of sophisticated high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) techniques capable of achieving the high level of sample purity and analysis2,15–27 required to identify the source of fluorescence signals. The work presented here provides an alternate model for internal conversion following the excitation of S2 (11Bu+) and suggests that at least some of the electronic states postulated in recent years may be associated with different geometric isomers and/or conformers formed in the S1 (21Ag−) state. Many of the essential features of the simple “three state” scheme, E (S2 (11Bu+)) > E (S1 (21Ag−)) > E (S0 (11Ag−)), are preserved by invoking isomerization and/or conformational change on short time scales in the S1 (21Ag−) state.

EXPERIMENTAL

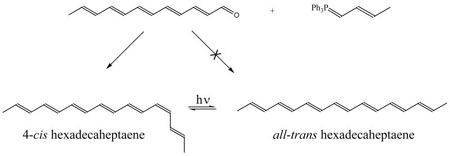

2,4,6,8,10,12,14-hexadecaheptaene was synthesized via a Wittig reaction between 2,4,6,8,10,12-dodecapentaenal and crotyltriphenylphosphonium bromide. The hexadecaheptaene products were isolated using silica gel chromatography and then photolyzed to convert the predominantly cis mixture into the all-trans isomer. HPLC (C18- reverse phase) was used to isolate the cis and trans isomers for spectroscopic analysis. Mass spectrometry (MS/APCI+) and NMR spectroscopy (2D 1H-1H COSY and NOESY) were used to identify the major product of the Wittig reaction as 4-cis hexadecaheptaene. The main photolysis product is the all-trans isomer, as summarized in the following reaction scheme:

Synthesis of 4-cis hexadecaheptaene

All-trans 2,4,6,8,10,12-dodecapentaenal was obtained by condensing crotonaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously.19,28,29 50 mg of the crotyl ylide (Fluka) was combined with 1 mL of anhydrous THF in a 5-mL flask. 17 mg of the dodecapentaenal was added and the mixture stirred for 30 minutes. The characteristic polyene absorption (300–400 nm) was used to follow the buildup of the heptaene product. Aqueous NaOH was added to quench the reaction and the hexadecaheptaene extracted using several aliquots of warm hexane. The crude hexadecaheptaene was purified on silica gel (Silica Gel 60 -EM Reagents) using hexane as a mobile phase.

Photoisomerization and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) of hexadecaheptaene

Hexadecaheptaene fractions collected from the silica gel column were evaporated and re-constituted in acetonitrile (Fisher Scientific, HPLC-grade) and placed in a 1-cm path length quartz spectrophotometer cell. The sample (Absorbance ~1.6) was exposed to 396 nm light with a 14.7 nm bandpass using a Jobin-Yvon Horiba Fluorolog-3 fluorescence spectrometer (see below). The illumination was interrupted every 5 minutes to mix the sample and to record the absorption spectrum. The total sample illumination time was 30 minutes. The photolyzed sample was analyzed using a Waters HPLC equipped with a 600S controller, a 616 pump and a 717plus autosampler. A Waters 996 photodiode array detector (PDA) monitored the absorption spectra of the peaks as they eluted from a Nova-Pak reverse-phase C18 column (3.9 × 300 mm, 60 Å pore size and 4 μm particle size of spherical amorphous silica). Acetonitrile was used as the mobile phase, and the system was run in isocratic mode at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min.

Characterization of hexadecaheptaene isomers by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

The dominant isomer in the unphotolyzed hexadecaheptaene sample (Fig. 1) was isolated by HPLC using a 250 × 4.6 mm YMC-Pak C18-A column (5-μm particle size, 12-nm pore size) and acetonitrile as the mobile phase. 1D and 2D 1H NMR spectra, including 1H-1H COSY and 1H-1H NOESY spectra, were recorded in chloroform-D at room temperature using a 600 MHz FT NMR spectrometer. Proton signals corresponding to the methyl groups showed distinct chemical shifts, indicating an asymmetric structure. Exploiting the 2D correlation peaks starting from the methyl protons, signals due to the ethylenic protons were assigned based on splittings, coupling constants, and COSY cross peaks between neighboring protons. These assignments are summarized in Figure S1 (Supporting Information). NOE correlations also proved useful in determining the isomeric configuration, e.g., the clear NOE correlation between 3H and 6H confirmed that the 4C=5C bond had a cis configuration. Other NOE correlations confirmed trans geometries for the other double bonds. The isomer thus was assigned unequivocally as 4-cis hexadecaheptaene.

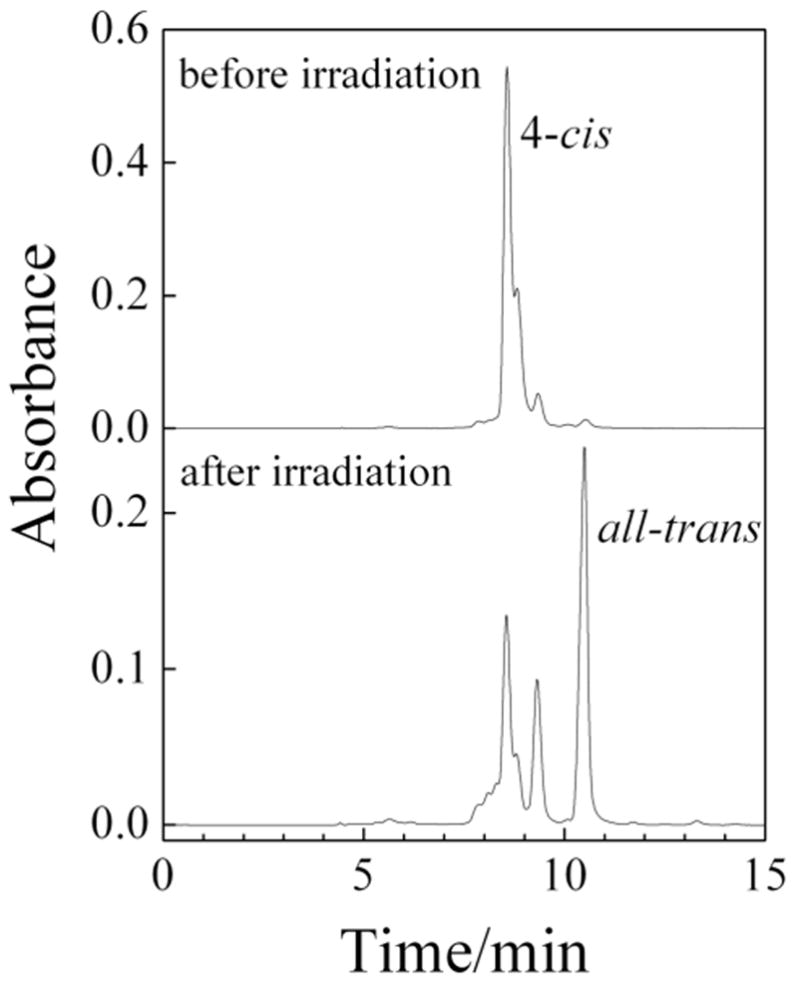

Figure 1.

HPLC of hexadecaheptaene before and after 396 nm irradiation. Chromatography was done on a C18 reverse phase column using acetonitrile as the mobile phase. Absorbance was monitored at 396 nm.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Individual HPLC peaks were collected, evaporated, and reconstituted in n-pentadecane for fluorescence and fluorescence excitation measurements. Samples were reinjected into the HPLC after spectroscopic experiments to verify their isomeric purity after exposure to light. Fluorescence spectra were acquired using a Jobin-Yvon Horiba Fluorolog-3 Model FL3-22 spectrometer equipped with double monochromators with 1200 grooves/mm gratings, a Hamamatsu R928P photomultiplier, and a 450 W OSRAM XBO xenon arc lamp. The emission was monitored using front-face detection for the low temperature experiments and right-angle detection for the room temperature measurements. A home-built, flowing gaseous N2 quartz cryostat maintained sample temperatures between 77 and 300 K. A gold-chromel thermocouple connected to an Air Products digital temperature controller monitored sample temperatures. For studies of the temperature dependence of fluorescence, purified samples were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and then transferred to the flowing N2 cryostat. The temperature was allowed to equilibrate for several minutes before taking each spectrum. Fluorescence spectra were collected systematically both with increasing and with decreasing temperature to understand the effects of photochemistry as well as temperature on the fluorescence intensities of samples that were initially highly-purified isomers. Emission spectra were corrected for the instrument response using a data file generated by a 200 W standard quartz tungsten-halogen filament lamp with spectral irradiance values traceable to NIST standards. For the display of spectra and the calculation of relative fluorescence yields, the emission spectra were converted to a wavenumber scale and intensities multiplied by λ2 to give relative emission intensities in photons/s cm−1.30

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Figure 1 shows the HPLC of the hexadecaheptaene sample before and after photoisomerization. One- and two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy (1H-1H COSY and 1H-1H NOESY) identify the peak eluting at ~8.5 min as the 4-cis isomer. This isomer dominates the products of the Wittig reaction, while the all-trans isomer is the major photochemical product. Irradiation of the pure all-trans isomer gives 4-cis hexadecaheptaene as the major photoproduct with the all-trans isomer dominating the photostationary state. The 4-cis and all-trans isomers thus are connected as major, but not exclusive photoisomerization products of each other. Extended irradiation indicates that, in addition to photoisomerization, there are a variety of other photochemical and thermal processes that lead to irreversible degradation of the samples.

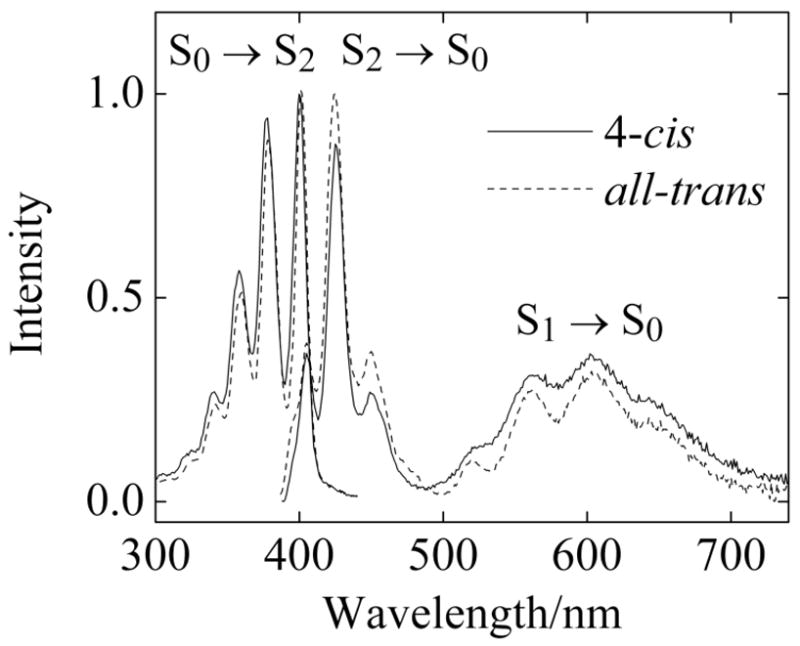

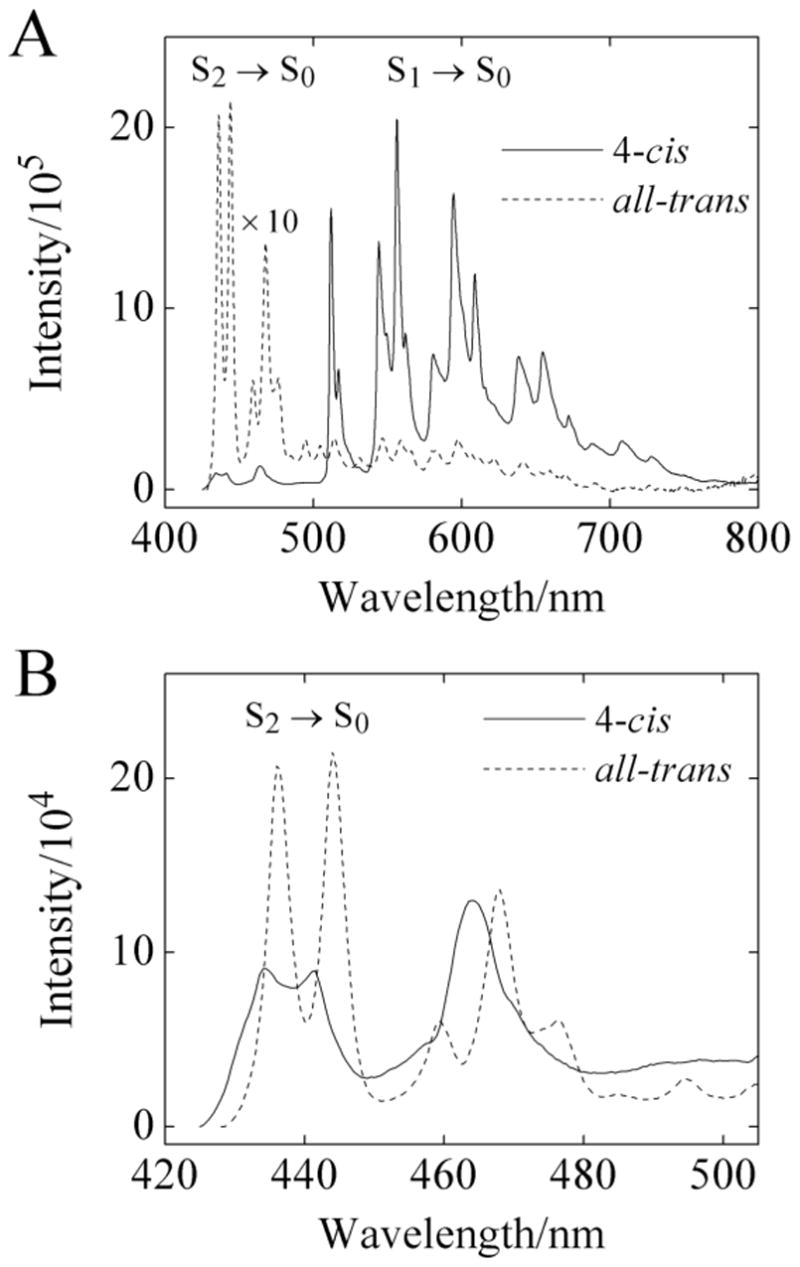

Collection of the 4-cis and all-trans fractions from the HPLC allows the comparison of their room temperature absorption and emission spectra in pentadecane (Fig. 2). As noted in previous studies of a wide range of polyenes and carotenoids in solution,31–33 the room temperature fluorescence spectra and fluorescence quantum yields of the cis and trans samples are very similar. Following S0 (11Ag−) → S2 (11Bu+) excitation, both isomers show dual emissions, S2 (11Bu+) → S0 (11Ag−) and S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−), a signature of polyenes and carotenoids with intermediate conjugation lengths (N ≈ 6–8).17,19,20,34,35 In n-pentadecane, the emission and absorption spectra of the heptaenes exhibit sufficient vibronic resolution to allow the identification of the (0–0) bands, providing an accurate measure of the energies of the S1 (21Ag−) and S2 (11Bu+) states of these isomers.

Figure 2.

Absorption and fluorescence spectra of 4-cis (378 nm excitation) and all-trans (377 nm excitation) hexadecaheptaene in n-pentadecane at room temperature. The absorption spectra are normalized to their maximum values. Maximum absorbances of ~0.10 minimized the effects of self-absorption. The fluorescence intensities have been corrected for the different room temperature absorbances of the two samples at the excitation wavelengths. Spectra were acquired with 1-nm bandpasses.

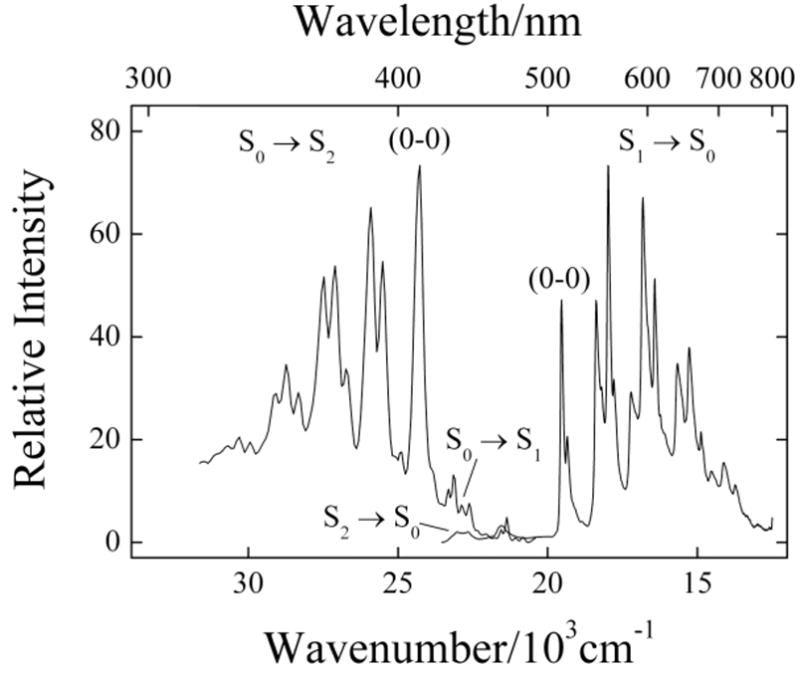

The 77 K fluorescence and fluorescence excitation spectra of 4-cis hexadecaheptaene in n-pentadecane are presented in Fig. 3. The high-resolution environment provided by the n-pentadecane matrix offer critical advantages in analyzing these spectra. The n-alkane mixed crystal selectively incorporates the polyene into a dominant substitutional site, providing well-defined, relatively homogeneous polyene-alkane interactions. This significantly decreases the inhomogeneous spectral broadening inherent to spectra obtained in solutions or low-temperature glasses. Although only the leading edge of the major 4-cis was collected from the HPLC (Fig. 1), the samples no doubt contain small amounts of other isomers. However, the high-resolution environments provided by the mixed crystals provide enhanced selectivity in exciting and detecting emission from the dominant 4-cis component in fluorescence emission and excitation spectra. The use of n-alkane host crystals36,37 has been exploited in several previous optical studies of simple polyenes,18,27,38–40 including 2,4,6,8,10,12,14,16-octadecaoctaene, the longest linear polyene studied using low-temperature, high-resolution mixed-crystal techniques.40

Figure 3.

Fluorescence excitation and emission spectra of 4-cis hexadecaheptaene in n- pentadecane at 77 K. The fluorescence spectrum was obtained by exciting at 411 nm, and the fluorescence excitation spectrum was monitored at 594 nm. Maximum absorbances of ~0.10 minimized the effects of self-absorption. Fluorescence intensities were corrected for the different room temperature absorbances of the two samples at the excitation wavelengths. Spectra were acquired with 1-nm bandpasses.

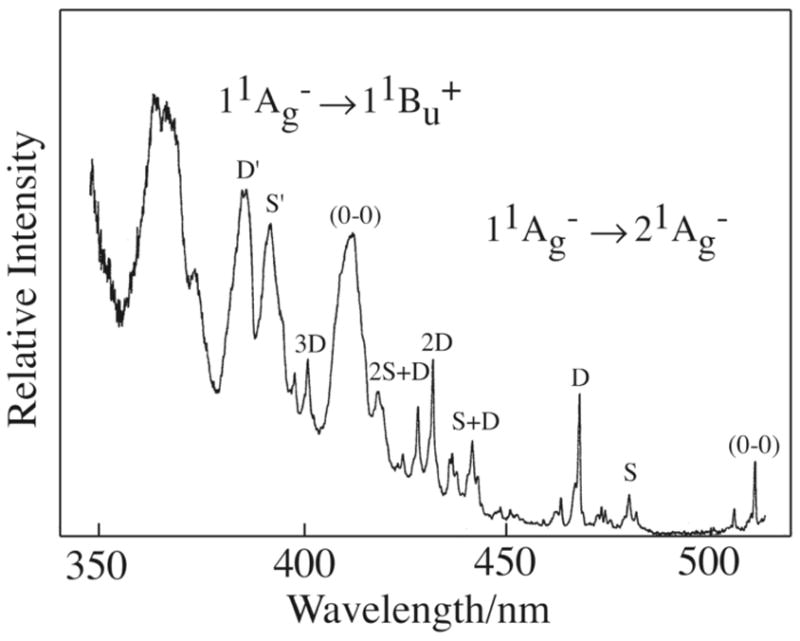

The spectra of 4-cis hexadecaheptaene presented in Fig. 3 exhibit well-resolved vibronic progressions in the S0 (11Ag−) → S2 (11Bu+) absorption and the S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) emission. As noted in previous studies on model polyenes,18,27,34,38–40 these progressions are dominated by combinations of totally symmetric carbon-carbon single and carbon-carbon double bond stretches built on easily identified electronic origins. The low temperature emission spectrum also shows features that can be identified with weak S2 (11Bu+) → S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence. In addition, the spectra allow the identification of relatively sharp vibronic bands due to the weak S0 (11Ag−) → S1 (21Ag−) transition on the low-energy tail of the strong S0 (11Ag−) → S2 (11Bu+) absorption. This transition is considerably more difficult to detect and identify in the much broader spectra of polyenes and carotenoids in room temperature solutions and low temperature glasses, illustrating another distinct benefit of the n-alkane matrices.

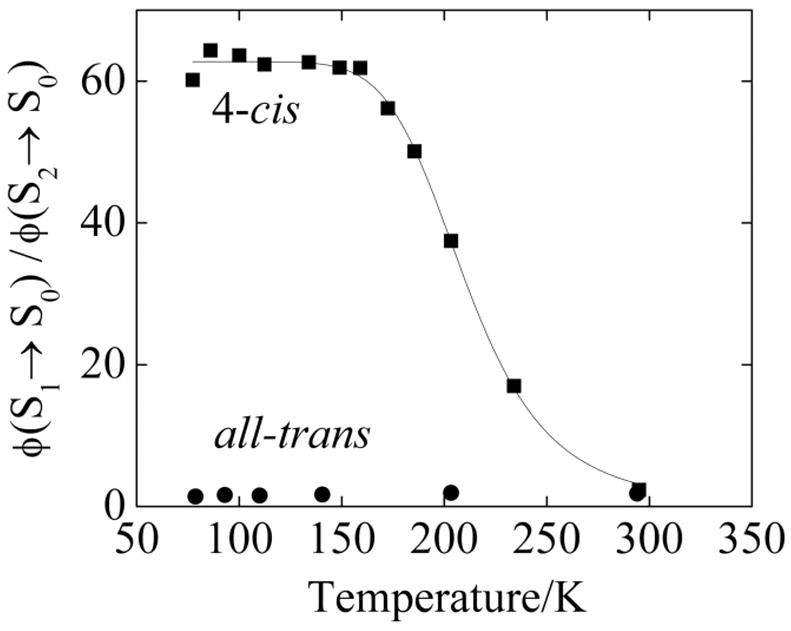

In contrast to the emission spectra obtained at room temperature, the 77 K fluorescence spectra (Fig. 4) of the 4-cis and all-trans isomers in n-pentadecane are remarkably different. The S2 (11Bu+) → S0 (11Ag−) emissions exhibit comparable intensities, with the all-trans isomer showing a small red shift in its somewhat better resolved spectrum (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, at 77 K the S1 (“21Ag−”) → S0 (“11Ag−”) emission of the 4-cis isomer is at least 20 times more intense than the S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) emission of the trans isomer (Fig. 4A). The dependence of the 4-cis emission yield on temperature is presented in Fig. 5. In order to compensate for fluctuations in fluorescence intensities in the flowing N2 cryostat, we compare the ratio of integrated fluorescence intensities, φ(S1→ S0)/φ(S2→ S0), for the two isomers. For the 4-cis isomer, the factor of ~15 change in this ratio is almost entirely due to the increase in S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence upon cooling to 77 K. The corresponding ratio in the all-trans isomer shows a two-fold decrease when the sample is cooled. It is important to note that the weak S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence observed for the trans isomer in part may be due to the photochemical production of highly fluorescent 4-cis and other cis impurities. The data indicated in Fig. 4 and 5 thus may underestimate the true difference between the low temperature S1 (21Ag) → S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence yields of the pure 4-cis and pure all-trans isomers.

Figure 4.

A) Comparison of fluorescence spectra of 4-cis and all-trans hexadecaheptaene in n-pentadecane at 77 K. The relative fluorescence intensities have been corrected for the difference in the room temperature absorbances of the two samples. Emission spectra were obtained by exciting into the S0 → S2 (0–0) bands (414 nm for all-trans, 411 nm for 4-cis). B) Expanded view of (A) showing the S2 → S0 fluorescence spectra of 4-cis hexadecaheptaene and all-trans hexadecaheptaene in n-pentadecane at 77 K. Emission bandpasses were 1 nm for all spectra.

Figure 5.

Ratios of integrated fluorescence yields (φ(S1→ S0)/φ(S2→ S0)) for 4-cis- (squares) and all-trans (circles) hexadecaheptaene as a function of temperature. The temperature dependence of the ratio for the 4-cis isomer was fit to Equation 1 assuming that kr, knr, and φ(S2→ S0) are independent of temperature. The four-parameter fit (solid line) gives Ea = 4.3 ± 1.4 kcal.

The n-alkane host offers a significant advantage for detecting the differences between S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence yields in the two isomers at low temperature. The n-pentadecane mixed crystal preserves the planar, symmetric (C2h) geometry of the all-trans heptaene, leading to relatively slow radiative decay for the symmetry-forbidden, S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) transition. Furthermore, the n-pentadecane environment provides sufficient optical resolution to differentiate between emissions due to the 4-cis and the all-trans species (Fig. 4). This is particularly important in distinguishing the weak emissions from the trans species from those of much more strongly emitting cis photochemical products. The differences between the fluorescence intensities of cis and trans samples are considerably less distinctive in the random environments provided by low temperature glasses (data not shown), which produce a distribution of distorted trans polyenes, many of which do not have C2h symmetry.

The current work recalls a previous controversy regarding the origin of the fluorescence signals (cis impurities versus the dominant trans species) in samples of cold, isolated octatetraene, the most highly studied and best-understood linear polyene. Buma et al.41 assigned the isolated molecule, S0 (11Ag−) → S1 (21Ag−) fluorescence excitation spectrum (obtained in a resonance-enhanced multiphoton ionization (REMPI) measurement) to a mono-cis isomer, arguing that the trans species would have insufficient oscillator strength for fluorescence detection. A subsequent study by Petek, et al.,42 on the high-resolution one- and two-photon fluorescence excitation spectra of octatetraene in supersonic jets, demonstrated that the oscillator strengths for the S0 (11Ag−) ↔ S1 (21Ag−) transitions in the trans isomer (induced by Herzberg-Teller vibronic coupling via low frequency bu promoting modes) were comparable to the corresponding oscillator strengths for cis isomers. This results in fluorescence intensities from the cis and trans isomers of isolated octatetraene that mirror their ground state abundances, i.e., the fluorescence spectra can be identified with the dominant trans isomer in typical samples. The identification of all-trans octatetraene as the dominant emitting species was confirmed by analysis of the rotationally resolved S0 (11Ag−) → S1 (21Ag−) fluorescence excitation spectrum by Pfanstiel, et al.43 These experiments established that the absorbing and emitting states both had all-trans, planar geometries and also demonstrated that the S0 (11Ag−) ↔ S1 (21Ag−) electronic transitions gain their intensities via vibronic coupling with the S2 (11Bu+) state.

The work presented here shows that, in contrast to octatetraene, the 4-cis isomer of hexadecaheptaene has a much higher S0 ↔ S1 oscillator strength than its all-trans counterpart. Under conditions where the trans isomer can be described by C2h symmetry, e.g., in low-temperature n-pentadecane, the vibronically induced, S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) radiative decay is relatively slow, and the fluorescence can be dominated by heptaenes with distorted, s-cis or cis conformations, even though these species may be present in relatively low concentrations. The ability of cis isomers to dominate the fluorescence systematically increases with increasing conjugation length (manuscript in preparation).

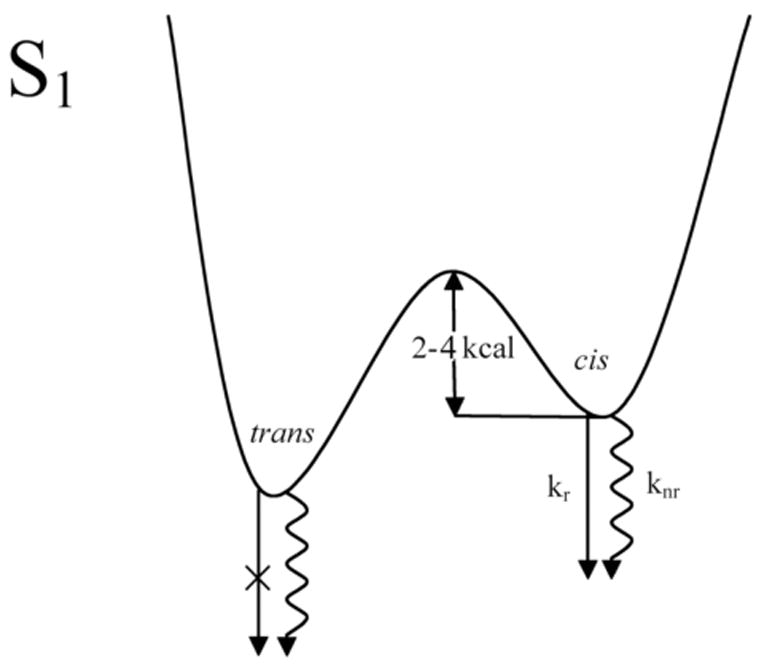

The striking difference in temperature dependence of the fluorescence from the two isomers (Fig. 5) leads to the simple, qualitative model presented in Fig. 6. The thermodynamically favored all-trans isomer is connected to the 4-cis isomer by a relatively low energy barrier in the S1 (21Ag−) state. Our preliminary photochemical studies (Fig. 1) indicate that additional cis isomers also are accessible on the S1 (21Ag−) potential surface. Theoretical considerations also implicate s-cis, as well as distorted trans isomers on a complicated, multi-dimensional potential surface with many local minima, connected by relatively low barriers. However, since the 4-cis and all-trans isomers are the two major products of all-trans and 4-cis photoisomerization, we only consider these isomers in a much-simplified model (Fig. 6). The lower energy, all-trans isomer dominates the photostationary state, a common theme in polyene and carotenoid photochemistry.44 Our model (Fig. 6) does not imply a mechanism for the isomerization; a detailed microscopic understanding of the chemistry would require additional experimental and theoretical work.

Figure 6.

Schematic potential energy surface for hexadecaheptaene in the S1 (21Ag−) state.

For the model presented in Figure 6, the S1 (21Ag−)→S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence quantum yield for the 4-cis isomer can be approximated by:

| (1) |

We assume that the radiative and nonradiative decay rates are independent of temperature and that the 4-cis → trans isomerization proceeds over an activation barrier Ea. We also assume that the S2 (11Bu+)→S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence yield does not depend on temperature in fitting the data presented in Figure 5 to Equation 1. The resulting four-parameter fit (see Fig. 5) yields an activation energy of 4.3 ± 1.4 kcal and a pre-exponential factor (A) of 1010–1012 s−1. The fit is poorly determined, e.g., the parameters for the activation energy and pre-exponential factor are highly correlated with large uncertainties. The fits are heavily influenced by the high temperature data points, which include the melting of the n-pentadecane crystal at 10 °C. In addition to the least squares analysis, we also have employed simulations to explore the parameter space and to better understand the data and the model (Equation 1). The determination of relative fluorescence yields as a function of temperature on samples undergoing photoisomerization is particularly challenging, especially for weakly emitting species. In spite of the limitations both of the model and the data, the parameters extracted from Equation 1 are consistent with thermally activated, 4-cis → trans isomerization in the S1 state.

An identical model was postulated to account for the temperature dependence of S1 lifetimes of cis and trans octatetraenes in different n-alkane solvents.45 The temperature-dependences of the octatetraene S1 lifetimes between 77 K and room temperature are comparable to the data presented in Fig. 5 and also were interpreted in terms of a thermally activated cis ⇆ trans isomerization in S1 with pre-exponential factors of 1010–1012 s−1 and activation energies of a few kcal/mol.45,46 For example, analysis of lifetime data indicated an S1 barrier of 1.1 kcal for the isomerization of cis, trans-1,3,5,7-octatetraene to the all-trans isomer47 and 2.5 kcal for the reverse process.45 The connections between the temperature dependence of the fluorescence lifetimes of octatetraene isomers and the fluorescent quantum yield data presented in Figure 5 with excited state isomerizations are buttressed by the temperature dependence of the photochemical quantum yields for trans→cis isomerizations in all-trans retinal. These studies indicate activation barriers of 1.6–3.2 kcal, depending on the solvent and the cis isomer formed.48 It also is important to note that the barriers to C=C isomerization in the S1 state are comparable to those for isomerization of carbon-carbon single bonds in polyene ground states.46,49 This reflects the significant rearrangement of the C-C and C=C π-bond orders in going from the ground to the S1 state.50

The low thermal barrier associated with the >20-fold increase in the S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence intensity with decreasing temperature cannot be explained by isomerization on the ground state S0 (11Ag−) potential energy surface. It also is not consistent with isomerization in the short-lived S2 state (11Bu+). If that were the case, we would expect a substantial change with temperature in the quantum yield of S2 (11Bu+) → S0 (11Ag−) emission, which is not observed. The increase in the ratio, φ(S1→ S0)/φ(S2→ S0), for the 4-cis isomer, thus is almost entirely due to the increase in S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence upon cooling. Furthermore, in solutions, trans ↔ cis isomerization in S1 (21Ag−) must compete with rapid nonradiative processes, which tend to dominate the excited state decay of longer polyenes and carotenoids.20

The all-trans heptaene S1→ S0 fluorescence yield shows a two-fold increase with temperature (Figure 5), suggesting that it crosses over a barrier in S1 to a more fluorescent species. It is tempting to ascribe this weak emission as due to adiabatic conversion to 4-cis heptaene in our simple model. This would account for the rather similar room temperature fluorescence spectra of the all-trans and 4-cis species (Fig. 2) and the fact that the 4-cis isomer is the dominant photoisomerization product of all-trans-hexadecaheptaene. However, the very small fluorescence yields of the all-trans isomer at all temperatures make it difficult to identify its fluorescence with a particular asymmetric species. Adiabatic pathways to other cis isomers, distorted trans conformers, as well as isomerization upon relaxation to the ground state all could induce fluorescence in samples of pure, C2h, all-trans hexadecaheptaene. It thus is much easier to make the case for 4-cis → all-trans adiabatic S1 conversion than for the reverse process.

The potential energy diagram presented in Fig. 6 is similar to that proposed by de Weerd et al.51 based on subpicosecond dynamics studies of all-trans β-carotene. However, those authors suggested that β-carotene became distorted in the S2 (11Bu+) state and relaxed back to the all-trans configuration upon decaying to S1 (21Ag−). This is not the case for hexadecaheptaene, and other investigators have argued that conformational twisting occurs in S1 (21Ag−) in β-carotene52 and other carotenoids.52–54

The relatively large oscillator strength for the S0 (11Ag−) ↔ S1 (21Ag−) transition in 4-cis hexadecaheptaene is confirmed by our ability to detect the S0 (11Ag−) → S1 (21Ag−) transition in the high-resolution fluorescence excitation spectrum (Fig. 7). The ~4700 cm−1 gap between the 11Bu+ and 21Ag− states provides a wide window for observing the vibronic development of the 21Ag− vibronic states built on the electronic origin (0-0) at 512 nm. Note also the coincidence between the 512 nm (0-0) bands in the S0 (11Ag−) → S1 (21Ag−) excitation spectrum (Fig. 7) and the S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) emission spectrum (Fig. 3). The overlap between electronic origins and the relatively strong S0 → S1 absorption indicate a symmetry-allowed electronic transition, as expected for the 4-cis isomer. A large S0 ↔ S1 oscillator strength explains the considerable enhancement in the 4-cis S1 → S0 fluorescence yield compared with that associated with the symmetry forbidden transition of the all-trans isomer. The excitation spectra for both the S0 → S1 and S0 → S2 absorptions show the classic pattern of vibronic intensities built on combinations of carbon-carbon single and double bond symmetric stretching modes. The vibronic spectrum shown in Fig. 7 previously was analyzed by Simpson et al. and assigned to the all-trans isomer.18 However, our current work shows that the vibronic states observed are due to 4-cis hexadecaheptaene.

Figure 7.

Fluorescence excitation spectra (11Ag− → 21Ag− and 11Ag− → 11Bu+) of 4-cis-2,4,6,8,10,12,14-hexadecaheptaene in 10 K n-pentadecane. Fluorescence was detected at 560 nm. Vibronic features labeled with S and D (and S′ and D′) indicate combinations of C-C and C=C symmetric stretching modes. This spectrum was obtained on a more concentrated sample than that used for the excitation spectrum presented in Fig. 3. This amplifies the 11Ag− → 21Ag− absorption. The excitation spectrum is not corrected for the wavelength dependence of the excitation system. (Figure adapted by the author, RLC, from Figure 3 of Reference 18).

CONCLUSIONS

The results presented here require a reinterpretation of fluorescence experiments previously carried out on all-trans isomers of longer polyenes and of related carotenoids. Several previous studies of longer linear polyenes (N>4) have assigned S1 → S0 fluorescence signals to all-trans isomers. Examples include the high-resolution work of Simpson et al. on hexadecaheptaene18 and of Kohler et al. on octadecaoctaene.40 The excitation and fluorescence spectra were assigned to all-trans species, but our work indicates that the S1 → S0 emission spectra of these longer polyenes most likely are due to cis isomers, present as impurities or formed as photochemical products in the S1 state. This is a significant finding, given that existing theoretical work (almost all on simple all-trans polyenes)4,5,55,56 has been compared with experimental work on what now must be assigned to cis species. Rapid isomerization in S1 (21Ag−) explains the typically small differences between the S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) emission spectra and quantum yields of cis and trans systems in room temperature solutions. The almost negligible S1 (21Ag−) → S0 (11Ag−) fluorescence yields from C2h, trans species and the relatively low resolution of solution and glass spectra prohibit a ready distinction between emissions due to trans isomers from those due to cis impurities or from trans molecules with conformational distortions that relax the rigorous selection rules. We thus conclude that, except for the very detailed studies of all-trans octatetraene, previous reports of S1 emissions from all-trans, C2h polyenes and carotenoids most likely are due to less symmetric species. These species may be present as ground state impurities, including photochemical products, or formed in the S1 (21Ag−) state following the excitation of all-trans polyenes.

Our results suggest that steady-state fluorescence experiments and time-resolved measurements, e.g., S1 → SN transient absorption experiments, detect different distributions of S1 (21Ag−) conformers and geometric isomers, even for samples with a single, all-trans, ground state structure. For example, the elegant S1 (21Ag−) → S2 (11Bu+) absorption experiments of Polívka et al.57 on several all-trans carotenoids, including spheroidene, zeaxanthin and violaxanthin, were compared with the transition energies for the strongly allowed S0 (11Ag−) → S2 (11Bu+) absorptions. The energy difference in the electronic origins ((0–0) bands) of these two symmetry-allowed transitions yields the S1 (21Ag−) energy. However, S1 electronic energies obtained in this manner were found to be consistently 500–1000 cm−1 lower than those from the fluorescence measurements. This is in accord with the model presented in Fig. 6. Fluorescence from these samples is from higher energy, distorted trans and/or cis carotenoids with S1 ↔ S0 oscillator strengths and radiative decay rates that are sufficiently large to compete with the rapid (~10 ps) nonradiative decays in these molecules. It should be noted that Polívka et al.58,59 suggested a similar model, though did not invoke isomerization, to explain the discrepancies between their results and the S1 (21Ag−) energies estimated by fluorescence techniques. Another conclusion from the current studies is that, at least for longer polyenes and related carotenoids, “forbidden” electronic transitions for molecules with C2h symmetries will be very difficult to detect. Optical techniques that exploit the selection rules for allowed transitions, e.g., S1 (21Ag−) → S2 (11Bu+) absorption, thus have obvious advantages in accurately locating the excited electronic energy levels of trans polyenes and carotenoids.

The low energy barriers to isomerization and conformational distortion in S1 (21Ag−) are consistent with significant rearrangements of the ground state C-C and C=C bond orders relative to the changes in S2 (11Bu+) and other low-energy excited states.3–5 This transposition of π-bond orders is a hallmark of polyene electronic structure and explains the unique ability of S1 states to promote rapid isomerization. Low barriers to isomerization and conformational change also may account for the complex kinetics of S2 (11Bu+) → S1 (21Ag−) nonradiative decay in carotenoids. As mentioned previously, Cerullo, et al.10 postulate the existence of an excited electronic state (Sx) between S2 (11Bu+) and S1 (21Ag−) that decays on a ~ 100 fs time scale, and van Grondelle et al.11 hypothesize that additional short-lived electronic singlet states (S* and S‡) provide alternate routes for internal conversion from S2. The current work strongly suggests that at least some of these proposed singlet electronic states instead may be manifestations of nonradiative decay on complicated S1 (21Ag−) potential surfaces. These surfaces provide multiple pathways for the zero-point level of S2 (11Bu +) to change its geometry to arrive at vibrationally relaxed, thermally equilibrated S1 (21Ag−).

Supplementary Material

1H chemical shifts and correlations of 1H-1H COSY and 1H-1H NOESY of 4-cis hexadecaheptaene. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tomáš Polívka and Robert Birge for fruitful discussions. RLC has been supported by the Bowdoin College Kenan and Porter Fellowship Programs and acknowledges funding from NSF-ROA (MCB-0314380 to HAF) and the Petroleum Research Fund, administered by the American Chemical Society. RLC also was supported in this work while serving at the National Science Foundation. This research is supported in the laboratory of HAF by the National Institutes of Health (GM-30353) and the University of Connecticut Research Foundation. HH and RF acknowledge grants-in-aid (# 17204026 and 17654083) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. HH and RF also acknowledge financial support from the Strategic International Cooperative Program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency. We also acknowledge the helpful comments of one of the referees in clarifying our understanding of the role of adiabatic photoisomerization in hexadecaheptaene.

References

- 1.Hudson B, Kohler B. Ann Rev Phys Chem. 1974;25:437–460. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudson BS, Kohler BE, Schulten K. Linear polyene electronic structure and potential surfaces. In: Lim ED, editor. Excited States. Vol. 6. Academic Press; New York: 1982. pp. 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schulten K, Karplus M. Chem Phys Lett. 1972;14:305–309. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tavan P, Schulten K. J Chem Phys. 1986;85:6602–6609. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tavan P, Schulten K. Phys Rev B: Condens Matter. 1987;36:4337–4358. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.36.4337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sashima T, Koyama Y, Yamada T, Hashimoto H. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:5011–5019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii R, Onaka K, Nagae H, Koyama Y, Watanabe Y. J Luminescence. 2001;92:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang JP, Inaba T, Watanabe Y, Koyama Y. Chem Phys Lett. 2000;332:351–358. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koyama Y, Rondonuwu FS, Fujii R, Watanabe Y. Biopolymers. 2004;74:2–18. doi: 10.1002/bip.20034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cerullo G, Polli D, Lanzani G, De Silvestri S, Hashimoto H, Cogdell RJ. Science. 2002;298:2395–2398. doi: 10.1126/science.1074685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gradinaru CC, Kennis JTM, Papagiannakis E, van Stokkum IHM, Cogdell RJ, Fleming GR, Niederman RA, van Grondelle R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2364–2369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051501298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen DS, Papagiannakis E, van Stokkum IHM, Vengris M, Kennis JTM, van Grondelle R. Chem Phys Lett. 2003;381:733–742. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kukura P, McCamant DW, Mathies RA. J Phys Chem A. 2004:108. doi: 10.1021/jp0482971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosumi D, Komukai M, Hashimoto H, Yoshizawa M. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95:213601–213604. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.213601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohler BE, Terpougov V. J Chem Phys. 1998;108:9586–9593. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensen RL, Kohler BE. J Phys Chem. 1976;80:2197–2200. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christensen RL, Barney EA, Broene RD, Galinato MGI, Frank HA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;430:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simpson JH, McLaughlin L, Smith DS, Christensen RL. J Chem Phys. 1987;87:3360–3365. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snyder R, Arvidson E, Foote C, Harrigan L, Christensen RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:4117–4122. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank HA, Josue JS, Bautista JA, van der Hoef I, Jansen FJ, Lugtenburg J, Wiederrecht G, Christensen RL. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:2083–2092. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shima S, Ilagan RP, Gillespie N, Sommer BJ, Hiller RG, Sharples FP, Frank HA, Birge RR. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107:8052–8066. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fujii R, Onaka K, Kuki M, Koyama Y, Watanabe Y. Chem Phys Lett. 1998;288:847–853. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Josue JS, Frank HA. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:4815–4824. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frank HA, Bautista JA, Josue JS, Young AJ. Biochemistry. 2000;39:2831–2837. doi: 10.1021/bi9924664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Onaka K, Fujii R, Nagae H, Kuki M, Koyama Y, Watanabe Y. Chem Phys Lett. 1999;315:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersson PO, Bachilo SM, Chen RL, Gillbro T. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:16199–16209. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Auerbach RA, Christensen RL, Granville MF, Kohler BE. J Chem Phys. 1981;74:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Amico KL, Manos C, Christensen RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:1777–1782. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer B, Jumper B, Hagan W, Baum JC, Christensen RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6907–6913. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 2. Kluwer Academic, Plenum Publishers; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bautista JA, Chynwat V, Cua A, Jansen FJ, Lugtenburg J, Gosztola D, Wasielewski MR, Frank HA. Photosyn Res. 1998;55:49–65. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andersson PA, Takaichi S, Cogdell RJ, Gillbro T. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;74:549–557. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074<0549:pconcc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank HA, Desamero RZB, Chynwat V, Gebhard R, van der Hoef I, Jansen FJ, Lugtenburg J, Gosztola D, Wasielewski MR. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:149–157. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christensen RL. The electronic states of carotenoids. In: Frank HA, Young AJ, Britton G, Cogdell RJ, editors. The Photochemistry of Carotenoids. Vol. 8. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 1999. pp. 137–159. [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeCoster B, Christensen RL, Gebhard R, Lugtenburg J, Farhoosh R, Frank HA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1102:107–114. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(92)90070-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shpol’skii EV. Sov Phys Usp. 1962;5:522–531. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shpol’skii EV. Sov Phys Usp. 1963;6:411–427. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christensen RL, Kohler BE. J Chem Phys. 1975;63:1837–1846. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andrews JR, Hudson BS. J Chem Phys. 1978;68:4587–4594. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohler BE, Spangler C, Westerfield C. J Chem Phys. 1988;89:5422–5428. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buma WJ, Kohler BE, Shaler TA. J Chem Phys. 1992;96:399–407. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petek H, Bell AJ, Choi YS, Yoshihara K, Tounge BA, Christensen RL. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:3777–3794. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pfanstiel JF, Pratt DW, Tounge BA, Christensen RL. J Phys Chem A. 1999;103:2337–2347. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zechmeister L. Cis-trans isomeric carotenoids, vitamin A, and arylpolyenes. Academic Press; New York: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kohler BE, Mitra P, West P. J Chem Phys. 1986;85:4436–4440. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kohler BE. Chem Rev. 1993;93:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ackerman JR, Kohler BE. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:3681–3682. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waddell WH, Chihara K. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:7389–7390. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ackerman JR, Kohler BE. J Chem Phys. 1984;80:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulten K, Ohmine I, Karplus M. J Chem Phys. 1976;64:4422–4441. [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Weerd FL, van Stokkum IHM, van Grondelle R. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;354:38–43. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kosumi D, Yanagi K, Nishio T, Hashimoto HMY. Chem Phys Lett. 2005;408:89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Billsten HH, Pan J, Sinha S, Pascher T, Sundström V, Polívka T. J Phys Chem A. 2005;109:6852–6859. doi: 10.1021/jp052227s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pendon ZD, Gibson GN, van der Hoef I, Lugtenburg J, Frank HA. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:21172–21179. doi: 10.1021/jp0529117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tavan P, Schulten K. J Chem Phys. 1979;70:5407–5413. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Head-Gordon M, Rico RJ, Oumi M, Lee TJ. Chem Phys Lett. 1994;219:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Polívka T, Herek JL, Zigmantas D, Akerlund HE, Sundström V. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4914–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Polívka T, Zigmantas D, Frank HA, Bautista JA, Herek JL, Koyama Y, Fujii R, Sundström V. J Phys Chem B. 2001;105:1072–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Polívka T, Sundström V. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2021–2071. doi: 10.1021/cr020674n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1H chemical shifts and correlations of 1H-1H COSY and 1H-1H NOESY of 4-cis hexadecaheptaene. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.