Abstract

The constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) enhances transcription of specific target genes that regulate several metabolic pathways. CAR functions as an obligate heterodimer with the retinoid-X-receptor (RXR). Also part of the active receptor complex is the steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) which interacts with the receptor complex via specific receptor interaction domains (RIDs). A peptide derived from the SRC-1 RID2 is used to study the thermodynamic properties of the interaction with the CAR/RXR ligand binding domain (LBD) complex. In the absence of ligands for both CAR and RXR, coactivator peptide binding to the CAR/RXR heterodimer is characterized by favorable enthalpy change and unfavorable entropy change. The addition of the CAR agonist, TCPOBOP, increases affinity for coactivator by decreasing unfavorable entropy and increasing the favorable intrinsic enthalpy of the interaction. The RXR ligand, 9-cis RA, generates a second SRC-1 site on RXR and increases affinity by improving the entropic component of binding. There is an additional increase in affinity for one of the two sites in the presence of both ligands. The change in heat capacity (ΔCp) is also investigated. A twofold difference in ΔCp is observed between liganded and unliganded CAR/RXR. The observed thermodynamic parameters for SRC-1 peptide binding to liganded and apo CAR/RXR as well as the difference in the ΔCp data provide evidence that the apo CAR/RXR heterodimer is conformationally mobile. The more favorable enthalpic contribution for TCPOBOP-bound CAR/RXR indicates that pre-formation of the binding site improves the complementarity of the coactivator-receptor interaction.

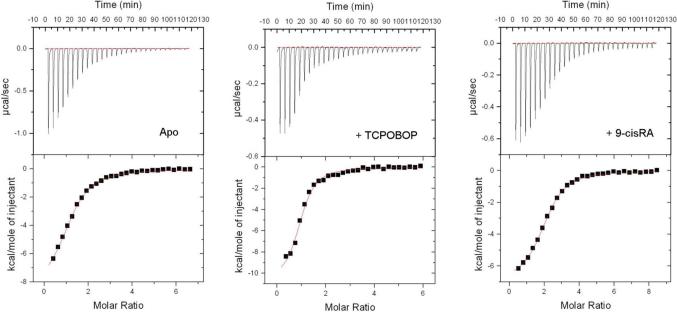

Activated nuclear receptors (NRs) recruit p160 transcriptional coactivators such as SRC-1/NCoA-1 and TIF2/GRIP/NCoA-2 and other coactivator proteins (Figure 1A) (1). These p160 coactivators in turn, can interact with CBP/p300 and associated molecules with histone acetyltransferase activity and activate the basal transcription machinery of the cell (2). When the NR binds agonist ligand, there is a conformational change in the C-terminus that results in a hydrophobic docking site for coactivator proteins such as SRC-1 (3). There are four unique receptor interaction domains (RIDs) in SRC-1 that can interact with the NR (4). Each RID contains a core amino acid motif that includes the sequence LXXLL (X=any amino acid). Since an NR can only bind a single RID at once, specificity of NRs for a particular RID on SRC-1 is determined by the amino acids that flank this LXXLL motif (5). Short peptides of up to thirteen amino acids based on the sequence of the RID have been observed to bind NRs through specific apolar, hydrogen bond and salt-bridge interactions in X-ray crystal structures (3, 6-9). In these structures, the conformation of these peptides is always helical, although the conformation of the RID within the free SRC-1 molecule is unknown.

Figure 1.

(A) Nuclear receptors are modular proteins containing an N-terminal DNA binding domain (DBD) which binds specific response elements (RE) upstream of the target gene and a C-terminal ligand binding domain (LBD) which binds small molecule ligands and recruits coactivator proteins such as SRC-1. The coactivator protein interacts with proteins which possess histone acetyltransferase activity (HATs) as well as the basal transcriptional machinery to enhance transcription of the target gene. (B) The sequence of the 13 residue peptide from SRC-1 used in the binding studies is shown. The LXXLL motif is underlined.

NR proteins share conserved domain architecture. X-ray structures of the ligand binding domains (LBDs) of all NRs determined to date, show a common three-dimensional fold. The LBD which is situated in the C-terminus of the NR encloses the ligand binding pocket within a 12 α-helical framework. Upon agonist binding, the C-terminal helix (H12) undergoes the largest conformational change thereby activating the ligand-dependent activation function 2 (AF2) domain. In the agonist bound active conformation, H12 is packed against the body of the LBD. In this position, H12 and residues from helix H3 create the hydrophobic cleft that interacts with the coactivator RID (10).

The constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) belongs to the NR superfamily and plays key roles in the clearance of both xenobiotics (11, 12) and endogenous toxins such as bilirubin (13). CAR is largely expressed in the liver and intestine where it controls the transcription of specific genes including P450 monoxygenases, phase II conjugating enzymes and xenobiotic transporters. This activity of CAR can also be deleterious as CAR mediated metabolism of acetaminophen results in a toxic reactive quinone metabolite (N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone). While classical NRs are inactive in the absence of ligand, CAR displays strong ligand-independent activity which implies that the H12/AF2 conformation in apo CAR is in the active-state conformation. As with many NRs, CAR functions as a heterodimeric partner of the retinoid X receptor-α (RXRα) and in the active state can recruit the coactivator protein SRC-1 by interacting specifically with RID2 of SRC-1 (14). CAR activity can be reversed by inverse agonists such as androstenol (5α-androst-16-en-3α-ol) (15). Although constitutively active, CAR activity can be enhanced by agonist ligands such as 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene (TCPOBOP) (16) and 6-(4-chlorophenyl(imidazol[2,1-b][1,3]thiazole-5-carbaldehyde O-(3,4-dichlorobenzyl)oxime (CITGO) (17), that are selective for murine and human CAR, respectively. CAR/RXR activity is also increased by the binding of RXR agonists such as 9-cis retinoic acid to RXR (18).

Crystal structures of CAR LBDs reveal that binding of ligand alters the conformation of helix 12 (AF2). The inverse agonist, androstenol, disrupts the H12/AF2 interactions with the LBD, while the agonists TCPOBOP and CITGO stabilize the active-state conformation of H12/AF2 so that coactivator binding is favored, in mCAR and hCAR respectively (7, 19, 20). Although, mutagenesis has shown that the same structural elements are required for ligand independent recruitment of coactivator proteins by CAR (14), less is known about the differences between coactivator binding to apo versus agonist-bound CAR/RXR. Because CAR can recruit coactivator without bound agonist, this nuclear receptor provides the rare opportunity to compare binding of coactivator proteins in the presence and absence of ligands. Here, we describe the thermodynamics of binding of a thirteen residue peptide based on RID2 of SRC-1 to the CAR/RXR heterodimer using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (Figure 1B). RID2 has been shown to be critical for SRC-1 binding to CAR and also binds RXR in the presence of RXR agonist (14, 21). ITC has been commonly used to analyze protein-peptide (22-24), protein-protein (25-27) and protein-ligand/substrate interactions (28). Previously, thermodynamic properties of coactivator binding to the androgen receptor have been determined using peptides derived from coactivator protein (29). In the present, study the mCAR/hRXR LBD heterodimer is used as the model system to characterize the thermodynamics of NR—coactivator interactions. Our data provide a detailed thermodynamic profile of the CAR/RXR interactions with SRC-1 peptide, including the changes in free energy, enthalpy, entropy and heat capacity. We have determined that the improved binding of SRC-1 peptide to agonist bound CAR in the heterodimer has both enthalpic and entropic components. We also show that the thermodynamic basis for agonist mediated enhancement of coactivator recruitment is different in the CAR monomer compared to CAR/RXR. Evidence is provided for allosteric communication between LBDs when both ligands are present. Finally, heat capacity changes and structural energetics are used to demonstrate that apo CAR/RXR is more conformationally mobile than CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR.

Experimental Procedures

Reagents

Purified SRC-1 peptide 687ERHKILHRLLQEG699 was purchased from the W.M. Keck Biotechnology Resource Center at Yale University. TCPOBOP was purchased from Calbiochem and 9-cis RA was purchased from MP Biomedicals.

Protein expression and purification

The murine CAR LBD (residues 117−358) was subcloned into pET15b with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag from mCAR cDNA kindly provided by Dr. Barry M. Forman. The human RXRα LBD (residues 225−462) was subcloned into the pACYC184 vector was a kind gift from Dr. Bruce Wisely (Glaxo Smith-Kline, Inc.). The two plasmids were cotransformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) Gold cells (Novagen). After induction with 0.5 mM IPTG the cells were grown 18−22 hrs at 20°C and harvested by centrifugation. The cells were lysed by French Press (two passes at 20,000 psi). The CAR/RXR heterodimer was first purified from the cleared lysate using Ni-NTA affinity (Qiagen) and subsequently by size-exclusion chromatography using Superdex 75 resin (GE Healthsciences). The concentration of protein was quantified using the Bio-Rad protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard. For use in ITC experiments, a more stable form of the CAR LBD was obtained by mutating a surface cysteine, distal from the SRC-1 binding site, to a serine residue. From cell-based transcription assays, this mutant form of CAR appears to have an identical transcriptional profile as wild-type CAR (data not shown). Henceforth, the CAR protein used in the assays below is the C221S mCAR LBD.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC experiments are performed using a VP_ITC microcalorimeter from Microcal, Inc. Purified CAR/RXR complex is dialyzed extensively against the buffer used in the ITC experiments. The following buffers are used: 50 mM HEPES, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM TCEP; 50 mM Tris-HCl, 75 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP and 50 mM Phosphate, 1 mM TCEP. The variation in NaCl concentration maintains a constant ionic strength for comparison of binding in different buffers. Stock solutions of ligand are prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Ligand concentrations are in fivefold molar excess of CAR/RXR, which is at least ten times the ligand:receptor dissociation constant in all titrations. Equivalent amounts of ligand are added to both protein and peptide solutions and the DMSO concentration is adjusted to 3.5% for all titrations including those in the absence of ligand. Titrations consist of 29 injections of 10 μL and were separated by 240 s. Each titration contains 2−40 μM CAR/RXR in the sample cell. Concentrations of SRC-1 peptide in the injection syringe ranged from 90 to 550 μM. For titrations using the CAR monomer the sample cell contained 25−40 μM protein and the injection syringe contains from 0.40 to 1.0 mM SRC-1 peptide. For all titrations the c values (c = KaMt, where Mt is the concentration of macromolecule binding sites (30)) ranges from 8 to 32. These values are within the ideal range for determining binding constants by ITC. In early experiments gel filtration was performed to verify that the quaternary state of the protein had not been altered during the titration (Supplementary S1).

All data are fit using Origin 5.0 (Microcal, Inc) to determine the binding constant (Ka), apparent stoichiometry (N), changes in binding free energy (ΔG), enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) (30).

The extent of binding-linked protonation is calculated using the equation:

| (1) |

where ΔHobs is the observed enthalpy change, ΔHint is the intrinsic enthalpy change, NH is the net number of protons taken up during the binding process and ΔHion is the ionization enthalpy of the buffer from reference (31). Extrapolation of ΔHobs to a value of zero buffer ionization (y-intercept) gives ΔHint .

The change in heat capacity is determined using the equation:

| (2) |

The ionization enthalpy for the individual buffers at each temperature are obtained from previous studies (31, 32). The extent of proton transfer and ΔHint is determined at each temperature using equation 3 and the resulting ΔHint values are plotted as a function of temperature to find ΔCp.

Solvent accessible surface area calculation and theoretical ΔCp

The access_surf program within the NMR_Refine module of Insight II® (Accelrys) is used to calculate solvent accessible surface area (1.4 Å solvent radius) from the structure of the CAR/RXR heterodimer with TCPOBOP, 9-cis RA and coactivator peptides bound (PDB ID: 1XLS). Surface areas are calculated for each atom and added to obtain the total polar and apolar solvent exposed surface areas. First, solvent accessible surface area is computed for the entire complex of liganded protein and bound coactivator peptides. Next, the solvent accessible surface area for the coactivator-free protein complex is computed by simply omitting the coordinates of the coactivator peptide from the structure. Finally, solvent accessible surface of the free peptide is determined by omitting the coordinates of CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR(9-cis RA). The change in polar and apolar solvent accessible surface area is determined by subtracting the values obtained from free heterodimer and free peptide from the values obtained from the heterodimer-peptide complex. For computation of the theoretical value of ΔCp from the structure, the equations developed by Murphy and Freire (33),

| (3) |

and Spolar et al.(34) are used.

| (4) |

In the above equations, ΔASA is the change in either apolar or polar solvent accessible surface area in Å2 and ΔCp is the change in heat capacity in cal K−1 mol−1.

Results and Discussion

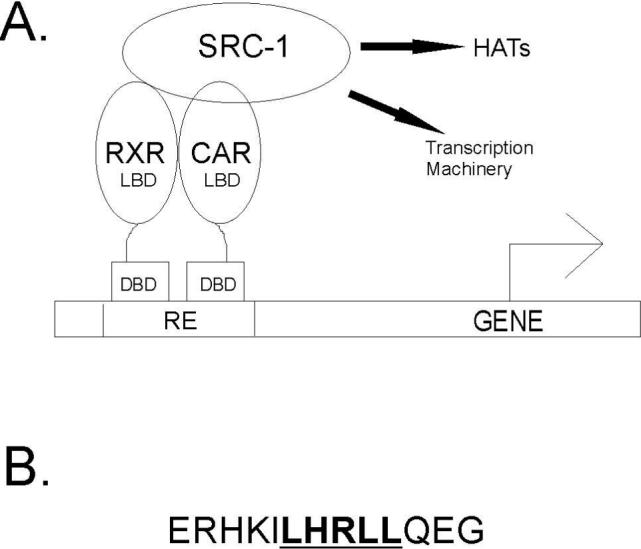

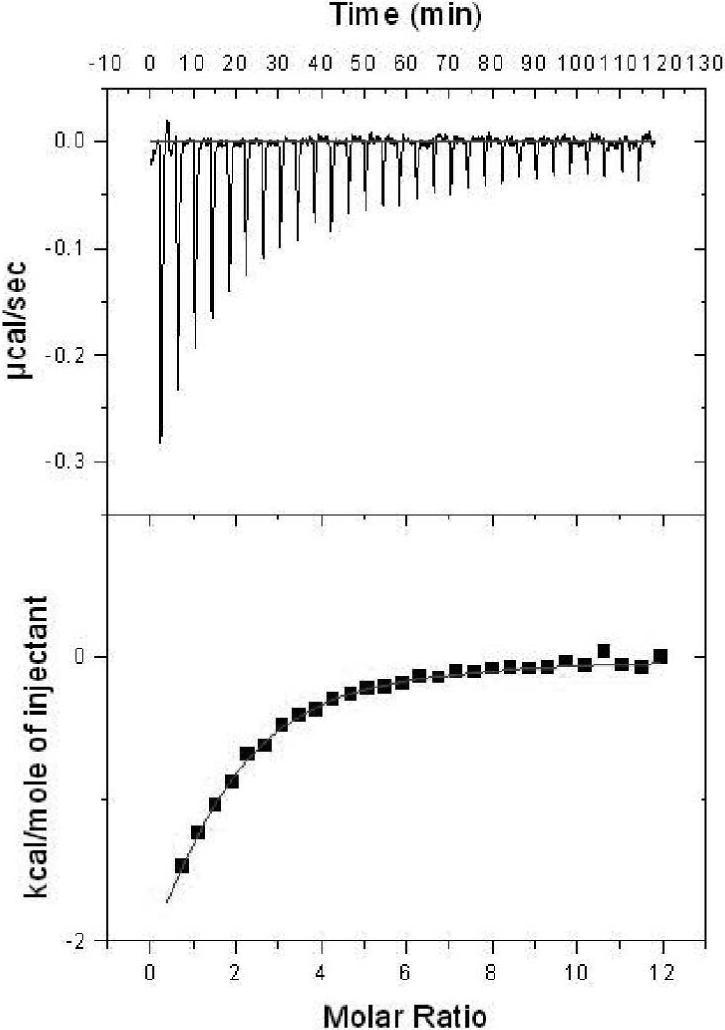

In the present study ITC is used to characterize the binding of coactivator to the LBDs of various CAR/RXR complexes including apo CAR/RXR, CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR, CAR/RXR(9-cis RA), CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR(9-cis RA), and monomeric CAR and CAR(TCPOBOP). Titrations in the presence of the inverse agonist, androstenol, could not be performed because of precipitation in the sample cell even at low ligand concentrations. Since the SRC-1 peptide binds both CAR and RXR, a total of two possible binding sites for this peptide are present on the CAR/RXR heterodimer. Peptides of similar length have been co-crystallized with other NRs (7, 9) and the peptide used in this study has been co-crystallized with the human CAR/RXR heterodimer (20). Amino acids flanking the 13-residue core do not appear to play a significant role in CAR/RXR binding since a SRC-1 RID2-based 21 amino acid peptide containing this 13 residue core shows no difference in affinity or enthalpy values from the 13 amino acid peptide (data not shown). Representative titrations for the 13 amino acid residue peptide binding to CAR/RXR complexes are shown in Figures 2 and 3. The data is summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

Representative titrations of SRC-1 peptide into CAR/RXR in the absence of ligand (left), in the presence of TCPOBOP (middle) and in the presence of 9-cis RA. Titrations contained 50 mM Phosphate buffer and 1 mM TCEP at pH 7.2.

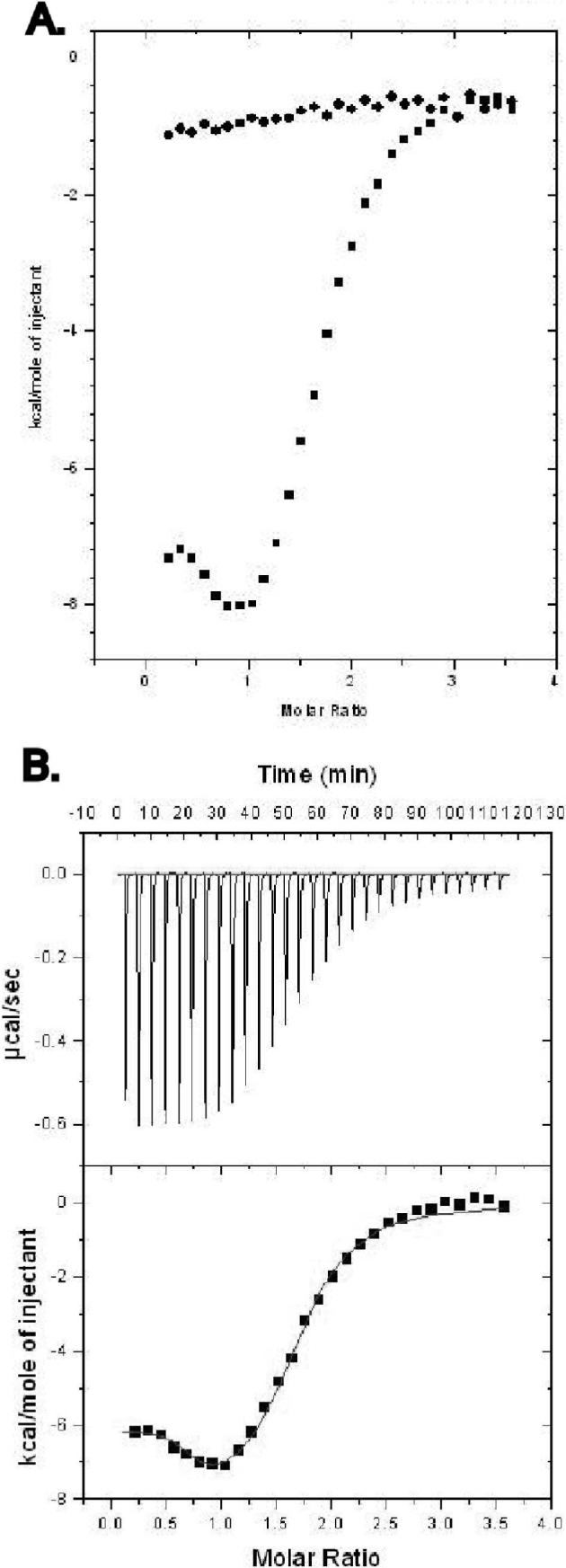

Figure 3.

(A) The titration of SRC-1 peptide into CAR/RXR in the presence of both TCPOBOP and 9-cis RA is shown. Data points represent the integration of the raw data for the titrations. Titrations of peptide into buffer and ligands were performed to determine background. (B) Data points resulting from subtraction of background and subsequent curve fitting to the data are shown.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for SRC-1 peptide binding to CAR/RXR in the presence of indicated ligandsa

| Ligand | Kd (μM) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | -TΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | Nb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEPES buffer | |||||

| TCPOBOP | 0.60 ± 0.1 | −10.0 ± 0.3 | 1.5 | −8.5 | 0.98 ± 0.07 |

| 9-cis RA | 1.5 ± 0.2 | −7.9 ± 0.3 | 0.0 | −7.9 | 2.04 ± 0.09 |

| None | 4.9 ± 0.7 | −10.0 ± 0.4 | 2.8 | −7.2 | 1.03 ± 0.06 |

| Phosphate buffer | |||||

| TCPOBOP | 0.62 ± 0.1 | −10.1 ± 0.2 | 1.6 | −8.5 | 1.01 ± 0.03 |

| 9-cisRA | 1.7 ± 0.1 | −7.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 | −7.9 | 1.98 ± 0.05 |

| None | 6.3 ± 0.5 | −9.2 ± 0.4 | 2.1 | −7.1 | 1.04 ± 0.05 |

| Tris buffer | |||||

| TCPOBOP | 0.63 ± 0.1 | −9.3 ± 0.2 | 1.2 | −8.5 | 0.96 ± 0.09 |

| 9-cisRA | 2.1 ± 0.3 | −8.1 ± 0.4 | 0.4 | −7.7 | 2.03 ± 0.09 |

| None | 5.4 ± 0.5 | −11.1 ± 0.2 | 3.9 | −7.2 | 1.02 ± 0.05 |

Determined at 25°C and pH 7.2 as described in materials and methods. The reported values are the average of three experiments and the errors are the standard deviation.

N is the apparent stoichiometry from the curve fitting data.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic parameters for SRC-1 peptide binding to CAR/RXR in the presence of 9-cisRA and TCPOBOPa

| Kd (μM) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | -TΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | Nb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site one | 0.10 ± 0.04 | −5.9 ± 0.4 | −3.7 | −9.6 | 0.93 ± 0.06 |

| Site two | 1.2 ± 0.2 | −9.2 ± 0.5 | 1.0 | −8.2 | 1.04 ± 0.08 |

Determined at 25°C and pH 7.2 in 50 mM HEPES, 0.1 M NaCl and 1 mM TCEP. The reported values are the average of five experiments and the errors are the standard deviation.

N is the apparent stoichiometry from the curve fitting data.

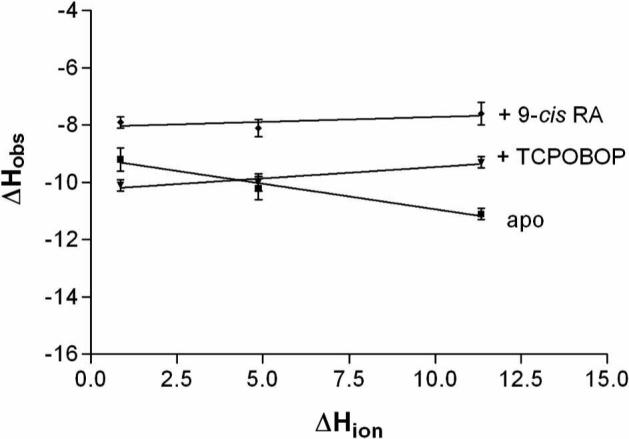

Binding linked protonation

The observed enthalpy change due to binding contains contributions from the protonation or deprotonation of the buffering system (35, 36). In this study binding of the SRC-1 peptide to CAR/RXR can result in a pKa shift for a residue on the peptide or macromolecule. To accommodate this change in pKa, protons are either taken up from or released to the buffer. To determine the extent of this phenomenon in the interaction between SRC-1 peptide and CAR/RXR heterodimer the titrations are performed in three separate buffers, each with a different heat of ionization. The observed enthalpy is plotted versus the heat of ionization of each buffer and the net uptake of protons determined from the slope (Figure 4). The net uptake is close to zero in the presence of either TCPOBOP (0.079) or 9-cis RA (0.033). In contrast, there is a small net release of protons when the SRC-1 peptide is titrated into apo CAR/RXR (−0.18) (Table 3). This net release is due to changes in the pKa of one or more ionizable groups on either SRC-1 peptide or CAR. Since the net uptake is different for apo compared to liganded CAR the contribution from buffer ionization to total enthalpy must be considered when comparing binding to the different CAR/RXR complexes.

Figure 4.

Enthalpy is plotted as a function of the heat of ionization of phosphate, HEPES, and Tris-HCl buffers at pH 7.2 to determine the extent of binding linked protonation.

Table 3.

Amount of net proton uptake by the CAR/RXR complexes resulting from SRC-1 peptide binding and the intrinsic enthalpy of the reactions.

| Complex | NH | ΔHint (kcal/ mol) |

|---|---|---|

| CAR/RXR | −0.18 | −9.1 |

| CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR | 0.079 | −10.2 |

| CAR/RXR(9-cis RA) | 0.033 | −8.0 |

Comparison of energetics of SRC-1 binding to apo and holo CAR in the CAR/RXR heterodimer

There is evidence that the CAR/RXR heterodimer can recruit SRC-1 leading to transcription of genes, in the absence of agonist (37). In the absence of an apo CAR:SRC-1/RXR complex structure, we have used ITC to characterize the recruitment of the SRC-1 13-amino acid peptide by the LBDs of apo CAR/RXR. As expected, the data for titrations of SRC-1 peptide into the apo heterodimer fit well to the one site binding model and the apparent stoichiometry for the interaction is one peptide molecule per CAR/RXR heterodimer (Figure 2). The affinity (Kd) ranges from 4.9 to 6.3 μM, depending on the buffer system used (Table 1). Furthermore, we note that the binding is enthalpically favorable (negative ΔH) but entropically unfavorable (negative TΔS). The measured enthalpy values of −9.2 kcal/mol, −10.0 kcal/mol and −11.1 kcal/mol most likely reflect the contributions from the four charged residues on CAR which directly interact with the coactivator (7). Lysine 187 of helix H3 and glutamate 355 of helix H12/AF2 in mCAR bind to residues at either end of the short, α-helical, coactivator peptide. These ‘charge clamp’ interactions are a common feature in NR:coactivator complexes (3). In the crystal structure, the E355 side chain forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone amide of the leucine immediately preceding the LXXLL motif (−1 position) in TIF2 (7). In SRC-1 this residue is an isoleucine. The K187 side chain H bonds with the backbone carbonyl of the leucine in the +5 position of the LXXLL motif (Supplementary Figure S2A). This residue is conserved in both, TIF2 and SRC-1. Additionally, E198 and K193 in CAR (helices H4 and H3′) salt-bridge with arginine (+2) and aspartic acid (+6) in TIF2, respectively (7). Positions +2 and +6 are histidine and glutamine in SRC-1 which can also H bond with E198 and R193 on CAR. ITC measures the global thermodynamic parameters of a system so the net ΔH is not merely the sum of these four hydrogen bonds, changes in protein-solvent and peptide-solvent interactions as well as changes in bonding within the protein and peptide also contribute. Nevertheless, the formation of these four hydrogen bonds will contribute significantly to ΔH. Besides these H bonding interactions, the interface of the SRC-1 peptide and CAR is predominantly apolar. While the burial of such exposed hydrophobic faces is expected to result in favorable entropy (positive TΔS), the observed change in entropy in our titration appears to be unfavorable (−2.8 kcal/mol). The observed TΔS can arise from two events, the burial of apolar surfaces (favorable TΔS) and a restriction of CAR mobility (unfavorable TΔS). There is accumulating evidence that NRs exist in a continuum of conformationally mobile states and the presence of ligand restricts this mobility (38). The most significant changes upon ligand binding are observed in the conformation of helix H12/AF2 (10). Binding of SRC-1 peptide can also restrict CAR mobility resulting in a decrease in entropy (unfavorable TΔS). Thus, the net loss in degrees of freedom in CAR:SRC-1 are larger than the favorable TΔS from burial of the apolar faces of CAR and the SRC-1 peptide.

Although constitutively active, CAR transcriptional activity can be enhanced by TCPOBOP approximately threefold with an EC50 of 0.1μM (39). The role of CAR agonist on SRC-1 recruitment was studied by performing the titration in the presence of saturating amounts of TCPOBOP. In this titration, SRC-1 peptide is expected to interact only with CAR since RXR is in the unliganded inactive form. As anticipated, this data fits well with the single site binding model with a stoichiometry of one SRC-1 peptide molecule per CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR complex. There is an almost tenfold increase in affinity (Kd = 0.6 μM) compared to apo CAR/RXR, a consequence of both, favorable enthalpy and favorable entropy (Figure 2, Table 1). The seemingly more favorable ΔH for apo over liganded CAR/RXR results from contributions of buffer ionization. Intrinsic ΔH is most favorable for CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR (ΔHint = −10.2 kcal/mol) compared to apo CAR/RXR (−9.1 kcal/mol) (Figure 4, Table 3).

In all three buffers used, the presence of TCPOBOP results in a decrease in the entropic penalty for the formation of the CAR:SRC-1 peptide complex. From a thermodynamic perspective, the binding of TCPOBOP reduces the difference in entropy between free CAR/RXR and CAR:SRC-1/RXR. Thus, the increased levels of transcription upon binding TCPOBOP may result predominantly from the stabilization of the CAR/RXR complex with an additional contribution from more favorable enthalpy.

Effect of 9-cis RA on SRC-1 binding to apo and TCPOBOP-bound CAR/RXR heterodimer

In the presence of 9-cis RA, the RXR AF2 domain adopts the active NR conformation and can recruit coactivator proteins (40). NR:RXR heterodimers respond differently to concurrent activation of both the NR and RXR and can be grouped into three broad categories. A permissive NR:RXR heterodimeric complex can be activated by agonists for either the NR or RXR, and the agonist activity is additive with both agonists present. Conditional heterodimers are activated by either the NR agonist or both NR and RXR agonists, but are unresponsive to RXR agonist alone. Non-permissive heterodimer association occurs when the complex is activated by NR agonist alone (41). The CAR constitutive activity makes it difficult to be categorized in the groups listed above. The effect of 9-cis RA on CAR activity in the absence of TCPOBOP depends on the nature of the response element on the target DNA. In ER-6 type response elements, RXR agonist alone has been shown to enhance transcription via CAR(apo)/RXR (18). To determine the effect of 9-cis RA on coactivator recruitment, SRC-1 peptide was titrated into the CAR/RXR(9-cis RA) complex. This SRC- 1 peptide also has a high affinity for RXR with a dissociation constant of 1.92 μM in the RAR/RXR heterodimer (21). As anticipated, the presence of the RXR agonist increases the apparent stoichiometry to two peptide molecules per CAR/RXR(9-cis RA) heterodimer complex, and the data fit well to a non-interacting sites model indicating that both NR LBDs can bind the SRC-1 peptide independently (Figure 2). Since the two sites have similar Kd's for the peptide, their individual thermodynamic parameters cannot be determined and the results reflect contributions from both sites. While the overall enthalpic contribution is less favorable here than with either the apo or TCPOBOP-bound CAR/RXR complexes, the entropic contribution is nearly neutral (close to zero) in CAR/RXR(9-cis RA) (Table 1). Unlike CAR which makes four H bonds with coactivator, RXR only forms two H bonds with the coactivator peptide (7). K284 and E453 in RXR H bond with the residues at each end of the α-helical coactivator peptide (Supplementary Figure S2B) (7). The remaining interactions between peptide and RXR are apolar. Although the ΔH is less favorable in the RXR:SRC-1 interaction which is most likely due to the fewer H bonds than CAR:SRC-1, the comparable Kd can be explained by the compensating neutral TΔS contribution.

Titrations were also performed in the presence of saturating concentrations of both TCPOBOP and 9-cis RA (Figure 3). The isotherm from these titrations has a unique shape relative to the other titrations with CAR/RXR complexes (Figure 3A). As with the CAR/RXR(9-cis RA) complex above, the stoichiometry indicates two SRC-1 peptide molecules per CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR(9-cis RA). Of the several models considered, the data fit best to a two sets of sites model, where each site has its own binding characteristics (Figure 3B). Interestingly, in the presence of both ligands, one of the sites has a significantly increased affinity for the SRC-1 peptide relative to the affinity with either single ligand. A similar pattern in coactivator binding to the two agonist-bound RAR/RXR heterodimers has been reported previously where a larger SRC-1 fragment with two intrinsic RIDs was used (42). The increase in coactivator recruitment by the RAR/RXR heterodimer was proposed to be mediated by the unimolecular nature of the coactivator fragment as binding of one RID to one receptor brings the second RID into increased proximity to bind the partner NR. However, in the current study the titrations are performed with independent peptide molecules which are capable of binding each receptor separately. Therefore, the improved binding observed here must be mediated by conformational changes within the CAR/RXR heterodimer. This binding data may also explain the additive increase in transcription measured in the presence of agonists for both CAR and RXR using DR-4 type response elements (18). However the additive effect is not observed with other response elements.

Allosteric contribution of RXR: SRC-1 binding to CAR monomer

RXR, the dimerization partner of CAR has been shown to be critical for CAR activity. In two-hybrid assays, while only a very weak association is observed between uncomplexed CAR and SRC-1, the addition of exogenous RXR increases the recruitment of SRC-1 by CAR over three-fold (14). Indeed, RXR has been observed to allosterically regulate the activity of other heterodimeric partners, notably the retinoic acid receptor, RAR (43, 44). To examine the role of RXR in CAR:SRC-1 interactions, we monitored global heat changes upon titration of the SRC-1 peptide into monomeric CAR. The binding isotherm suggests that the monomeric CAR:SRC-1 interaction (Kd = 21.3 μM) is substantially weaker than in the CAR/RXR heterodimer (Kd = 4.9 μM) (Figure 5, Table 4). In the presence of saturating amounts of TCPOBOP, the CAR:SRC-1 binding improves (Kd = 8.7 μM), as in CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR (Table 4). This affinity for SRC-1 peptide in the presence of TCPOBOP is lower than with both, apo CAR/RXR and CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR in the same buffering system. Also, the improvement in SRC-1 binding from apo to TCPOBOP-bound monomeric CAR is primarily enthalpic and the difference in ΔH is significantly large (>3 kcal/mol). This is in contrast to the effect of TCPOBOP on CAR/RXR, where entropic changes play a significant (unfavorable) role in SRC-1 peptide recruitment. Also in contrast to CAR/RXR, both, the CAR:SRC-1 and CAR(TCPOBOP):SRC-1 complexes are associated with favorable changes in entropy. It is likely that in monomeric CAR, distal regions of the protein can undergo conformational changes to compensate for the loss of entropy that accompanies binding to SRC-1 peptide. In the more conformationally restricted CAR/RXR heterodimer these regions may be restricted by RXR and the loss in entropy upon binding SRC-1 peptide is not adequately compensated for by conformational changes in CAR.

Figure 5.

SRC-1 binding to monomeric CAR in the absence of ligand in 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM TCEP at pH 7.2.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters for SRC-1 peptide binding to CARa

| Kd (μM) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | -TΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | Nb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCPOBOP | 8.7 ± 0.8 | −6.4 ± 0.5 | −0.4 | −6.8 | 0.96 ± 0.09 |

| Apo | 21.3 ± 2.4 | −5.8 ± 0.7 | −0.6 | −6.4 | 0.95 ± 0.10 |

Determined at 25°C and pH 7.2 in 50 mM HEPES, 0.1 M NaCl and 1 mM TCEP. The reported values are the average of three experiments and the errors are the standard deviation.

N is the apparent stoichiometry from the curve fitting data.

The overall lower Kd for SRC-1 binding to monomeric CAR, compared to the CAR/RXR heterodimer, is largely a consequence of significantly less favorable ΔH (Table 4). Thus, it is likely that the presence of RXR results in an optimal geometric orientation of the CAR binding site for the SRC-1 peptide resulting in higher affinity between CAR and coactivator in the CAR/RXR heterodimer.

Structural energetics and change in heat capacity associated with coactivator binding

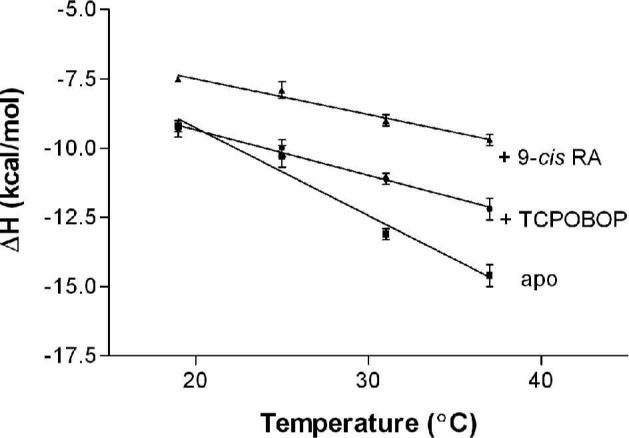

The change in heat capacity (ΔCp) in a protein-peptide interaction is analogous to protein unfolding, protein-ligand and protein-DNA interactions and depends primarily on the change in hydration due to the binding event (45); from ΔCp, the change in solvent exposure of polar and nonpolar surfaces can be estimated (33, 46, 47). To determine ΔCp for the binding of SRC-1 peptide to apo and liganded CAR/RXR heterodimers, titrations were performed at four different temperatures in HEPES and phosphate buffers. The heat capacity was determined from the slope of the linear regression fit when ΔH is plotted against the temperature at which the titration is performed (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Observed enthalpy is plotted as a function of temperature to determine ΔCp for SRC-1 peptide binding to apo CAR/RXR (ΔCp = −320 ± 30 cal mol−1 K−1), CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR (ΔCp = −160 ± 20 cal mol−1 K−1), and CAR/RXR(9-cis RA) (ΔCp = −120 ± 20 cal mol−1 K−1). Titrations contained 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl and 1 mM TCEP and the pH was adjusted to 7.2 at each temperature.

A negative ΔCp is observed in the formation all three CAR/RXR:coactivator complexes (Figure 6). There is very little change in affinity (δΔG/δT ≤ 0.1 kcal K−1mol−1) between the SRC-1 peptide and the CAR/RXR heterodimer at the different temperatures. The effect of temperature on binding energetics is manifested in the change in the thermodynamic parameters, ΔH and TΔS. As the temperature is increased, there is a proportionate increase in favorable ΔH, which is compensated by decreasing favorable entropy (Supplementary Figure S3).

Using the published structure of the CAR(TCPOBOP)(TIF2)/RXR(9-cis RA)(TIF2) complex (PDB code, 1XLX) (7) we have estimated the ΔCp upon coactivator binding to this complex. The two peptides used, TIF2 derived peptide in the structure, and the SRC-1 peptide in our titrations are highly homologous and share the LXXLL motif, thus the ΔASA calculated here should provide a very reasonable approximation of the apolar and polar exposed surface area. The calculated ΔASA values for coactivator peptide binding to CAR(TCPOBOP) are ΔASAapolar = −765 Å2 and ΔASApolar = −394 Å2. Using equations 3 and 4, the theoretical values for ΔCp = −310 cal K−1 mol−1 and ΔCp = −189 cal K−1 mol−1, respectively. Our experimentally determined value for ΔCp appears to agree with the theoretical treatment summarized in equation 4. The agreement of theoretical and experimental results suggests that the heat capacity change for this complex can be explained largely by the burial of solvent exposed surface at the interface of CAR and peptide and conformational changes distal to the SRC-1 binding site have minimal effect on binding energetics of the liganded complex. Binding of the SRC-1 peptide to apo CAR/RXR yields a significantly larger ΔCp (−320 cal K−1 mol−1). The absence of an apo CAR/RXR structure complexed with coactivator peptide precludes a similar structural analysis and comparison. The twofold increase in ΔCp when SRC-1 peptide binds apo heterodimer compared to CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR suggests significant differences in the conformations of the two complexes prior to coactivator binding. Since the surface area buried upon binding SRC-1 peptide is likely to be similar in apo and CAR(TCPOBOP), the significantly larger ΔCp for SRC-1 binding apo CAR reiterates earlier observations that unliganded CAR is substantially more conformationally mobile than CAR(TCPOBOP). SRC-1 binding presumably induces changes in structure such that apolar surfaces distal to the coactivator binding site that were once exposed to solvent are buried upon binding the peptide. The theoretical values derived using equation 3 would require an alternate explanation. However the entropy values described in Table 1 support the model described using equation 4.

The net energetic effects of structural changes within the free peptide and the bound, five-residue helical SRC-1 peptide should be similar in all titrations.

The calculated values for coactivator peptide binding to RXR are ΔASAapolar = −814 Å2 and ΔASApolar = −467 Å2. These values lead to a theoretical ΔCp of −318 cal K−1 mol−1 and −195 cal K−1 mol−1 using equations 7 and 8 respectively. The experimental value for ΔCp is −120 cal K−1 mol−1 which is also closer to the value predicted by equation 8. However, the experimentally determined ΔCp in this case reflects the two events of SRC-1 binding CAR and RXR in the heterodimer. This lower experimental ΔCp cannot accommodate the substantial changes in heat that accompany the relatively large conformational changes proposed by the ΔCp observed in SRC-1 peptide binding to apo CAR/RXR. This observation raises the interesting possibility that RXR ligand can induce CAR into a conformation with a pre-formed coactivator binding site. In this scenario, coactivator recruitment of the CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR(9-cis RA) complex will not differ significantly from apo CAR/RXR(9-cis RA). Cell-based transcriptional assays showing the effect of 9-cisRA on CAR/RXR mediated transcription activation in the absence of CAR agonist also support this model (18).

Conclusions

In coactivator recruitment by the CAR/RXR heterodimer, our results imply that while the specific interactions in the CAR:SRC-1 assembly are similar, the enhanced transcriptional activity of CAR(TCPOBOP) over apo CAR arises from a more effective recruitment of SRC-1 by a less conformationally ambiguous CAR(TCPOBOP). Additionally, the significance of RXR in coactivator recruitment is evident from the difference in the Kd and ΔH in the monomeric CAR versus the CAR/RXR heterodimer.

The observed allosteric effect of ligand of one receptor on the affinity at the coactivator binding site on the other NR in the heterodimer demonstrates that the increased transcription with both agonists is mediated by interactions between the two LBDs. Because of the complex nature of this data, additional experiments will be necessary to confirm this phenomenon. Titrations using mutants of RXR which are impaired in the ability to bind coactivator may be useful, but selection of mutations and data analysis can be complicated by the global effects of even a point mutation.

The ΔCp data for the complexes also provides insight into the entropic contribution of SRC-1 peptide binding to CAR/RXR. Two major components of the overall ΔS for a process are solvation and conformational entropy (48) . Differences in solvation entropy will result from changes in the exposure of hydrophobic surfaces to solvent. The twofold difference in ΔCp indicates that ΔSsolv would be more favorable in the unliganded heterodimer. Therefore, the more unfavorable ΔStotal observed in SRC-1 peptide binding to apo CAR/RXR compared to CAR(TCPOBOP) must result from more unfavorable ΔSconf. This reflects a smaller difference in degrees of freedom between CAR(TCPOBOP)/RXR and CAR(TCPOBOP):SRC-1/RXR than differences in the NR:SRC-1 complexes in the absence of ligand. The agonist TCPOBOP reduces the ensemble of conformations of CAR/RXR by making specific interactions with CAR and thus reducing the flexibility of the CAR/RXR heterodimer.

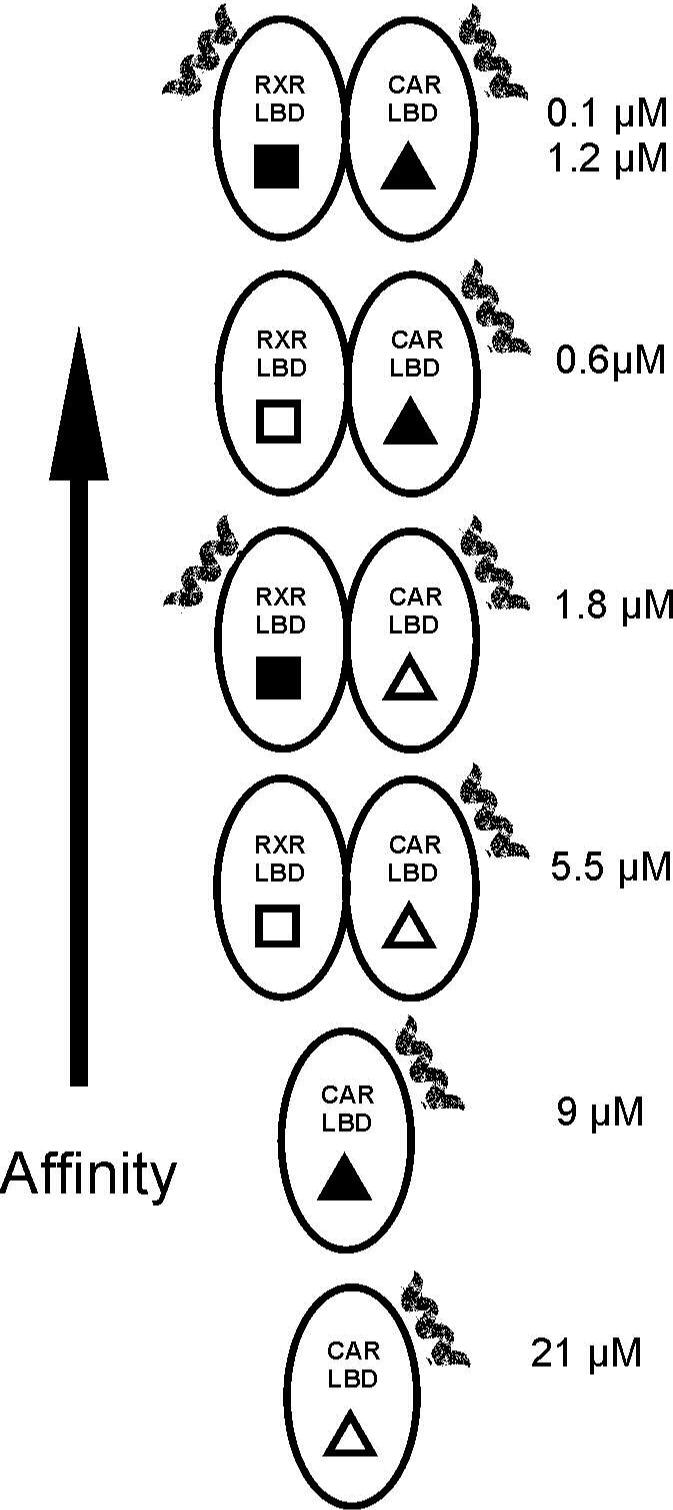

The affinity and stoichiometry of the SRC-1 peptide interactions with the various NR complexes are summarized in figure 7. While these results demonstrate that increasing affinity for coactivator and increased transcription follow the same trend, a direct numerical correlation is not established (e.g. a tenfold increase in peptide affinity only leads to a threefold increase in transcription). This discrepancy is probably due to the other events that occur after SRC-1 recruitment and prior to initiation of transcription.

Figure 7.

The effect of ligand and RXR on the affinity and stoichiometry of SRC-1 peptide is summarized. The short helix represents the bound peptide. The filled shapes indicate the presence of 9-cis RA (■) and TCPOBOP (▲). The numbers to the right of the diagrams indicate the dissociation constant for the interaction(s).

This study is likely to have general implications on the underlying mechanics of SRC-1 recruitment and RXR-mediated allosterism and may well be a common feature within the NR superfamily. The sequence of events in ligand binding, coactivator recruitment and the underlying interactions between heterodimeric partners, ligand-receptor and receptor-coactivator are remarkably conserved. Further studies with larger SRC-1 fragments and full-length NRs in the presence of specific RE-derived DNA fragments may reveal the mechanism of coactivator recruitment in even greater detail.

Supplementary Material

Acknowlegements

We thank Drs. Barry Forman, Elizabeth Howell, and Engin Serpersu for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful suggestions. We also thank Mr. Sumit Patel for protein preparation.

Abbreviations

- CAR

constitutive androstane receptor

- RXR

retinoid-X-receptor

- SRC-1

steroid receptor coactivator-1

- RID

receptor interaction domain

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- TCPOBOP

1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene

- 9-cis RA

9-cis retinoic acid

- NR

nuclear receptor

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- AF2

activation function 2

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

Footnotes

This research was supported by Grant R01-DK 066394 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Supporting Information Available

Chromatograms showing oligomeric states of CAR/RXR and monomeric CAR after ITC titrations (Figure S1), figures showing the hydrogen bonds formed between peptide and CAR/RXR (Figure S2), and graphs of ΔG and –TΔS as a function of temperature (Figure S3) are available as supplementary material. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Torchia J, Glass C, Rosenfeld MG. Co-activators and corepressors in the integration of transcriptional responses. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1998;10:373–83. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Onate SA, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily. Science. 1995;270:1354–7. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nolte RT, Wisely GB, Westin S, Cobb JE, Lambert MH, Kurokawa R, Rosenfeld MG, Willson TM, Glass CK, Milburn MV. Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Nature. 1998;395:137–43. doi: 10.1038/25931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalkhoven E, Valentine JE, Heery DM, Parker MG. Isoforms of steroid receptor co-activator 1 differ in their ability to potentiate transcription by the oestrogen receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17:232–43. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McInerney EM, Rose DW, Flynn SE, Westin S, Mullen TM, Krones A, Inostroza J, Torchia J, Nolte RT, Assa-Munt N, Milburn MV, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Determinants of coactivator LXXLL motif specificity in nuclear receptor transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3357–68. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watkins RE, Wisely GB, Moore LB, Collins JL, Lambert MH, Williams SP, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, Redinbo MR. The human nuclear xenobiotic receptor PXR: structural determinants of directed promiscuity. Science. 2001;292:2329–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1060762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suino K, Peng L, Reynolds R, Li Y, Cha JY, Repa JJ, Kliewer SA, Xu HE. The nuclear xenobiotic receptor CAR: structural determinants of constitutive activation and heterodimerization. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:893–905. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiau AK, Barstad D, Loria PM, Cheng L, Kushner PJ, Agard DA, Greene GL. The structural basis of estrogen receptor/coactivator recognition and the antagonism of this interaction by tamoxifen. Cell. 1998;95:927–37. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darimont BD, Wagner RL, Apriletti JW, Stallcup MR, Kushner PJ, Baxter JD, Fletterick RJ, Yamamoto KR. Structure and specificity of nuclear receptor-coactivator interactions. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3343–56. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moras D, Gronemeyer H. The nuclear receptor ligand-binding domain: structure and function. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1998;10:384–91. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80015-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei P, Zhang J, Egan-Hafley M, Liang S, Moore DD. The nuclear receptor CAR mediates specific xenobiotic induction of drug metabolism. Nature. 2000;407:920–3. doi: 10.1038/35038112. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Huang W, Chua SS, Wei P, Moore DD. Modulation of acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity by the xenobiotic receptor CAR. Science. 2002;298:422–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1073502. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang W, Zhang J, Moore DD. A traditional herbal medicine enhances bilirubin clearance by activating the nuclear receptor CAR. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113:137–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI200418385. [see comment] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dussault I, Lin M, Hollister K, Fan M, Termini J, Sherman MA, Forman BM. A structural model of the constitutive androstane receptor defines novel interactions that mediate ligand-independent activity. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:5270–80. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.15.5270-5280.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forman BM, Tzameli I, Choi HS, Chen J, Simha D, Seol W, Evans RM, Moore DD. Androstane metabolites bind to and deactivate the nuclear receptor CAR-beta. Nature. 1998;395:612–5. doi: 10.1038/26996. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzameli I, Pissios P, Schuetz EG, Moore DD. The xenobiotic compound 1,4-bis[2-(3,5-dichloropyridyloxy)]benzene is an agonist ligand for the nuclear receptor CAR. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:2951–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.2951-2958.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maglich JM, Parks DJ, Moore LB, Collins JL, Goodwin B, Billin AN, Stoltz CA, Kliewer SA, Lambert MH, Willson TM, Moore JT. Identification of a novel human constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) agonist and its use in the identification of CAR target genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:17277–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tzameli I, Chua SS, Cheskis B, Moore DD. Complex effects of rexinoids on ligand dependent activation or inhibition of the xenobiotic receptor, CAR. Nucl. Recept. 2003;1:2–9. doi: 10.1186/1478-1336-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shan L, Vincent J, Brunzelle JS, Dussault I, Lin M, Ianculescu I, Sherman MA, Forman BM, Fernandez EJ. Structure of the murine constitutive androstane receptor complexed to androstenol: a molecular basis for inverse agonism. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:907–17. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu RX, Lambert MH, Wisely BB, Warren EN, Weinert EE, Waitt GM, Williams JD, Collins JL, Moore LB, Willson TM, Moore JT. A structural basis for constitutive activity in the human CAR/RXRalpha heterodimer. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:919–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pogenberg V, Guichou JF, Vivat-Hannah V, Kammerer S, Perez E, Germain P, de Lera AR, Gronemeyer H, Royer CA, Bourguet W. Characterization of the interaction between retinoic acid receptor/retinoid X receptor (RAR/RXR) heterodimers and transcriptional coactivators through structural and fluorescence anisotropy studies. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:1625–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409302200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye H, Wu H. Thermodynamic characterization of the interaction between TRAF2 and tumor necrosis factor receptor peptides by isothermal titration calorimetry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:8961–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160241997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goto NK, Zor T, Martinez-Yamout M, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Cooperativity in transcription factor binding to the coactivator CREB-binding protein (CBP). The mixed lineage leukemia protein (MLL) activation domain binds to an allosteric site on the KIX domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:43168–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207660200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adhikari A, Sprang SR. Thermodynamic characterization of the binding of activator of G protein signaling 3 (AGS3) and peptides derived from AGS3 with G alpha i1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51825–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murphy KP, Freire E, Paterson Y. Configurational effects in antibody-antigen interactions studied by microcalorimetry. Proteins. 1995;21:83–90. doi: 10.1002/prot.340210202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raman CS, Allen MJ, Nall BT. Enthalpy of antibody--cytochrome c binding. Biochemistry. 1995;34:5831–8. doi: 10.1021/bi00017a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker BM, Murphy KP. Dissecting the energetics of a protein-protein interaction: the binding of ovomucoid third domain to elastase. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;268:557–69. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright E, Serpersu EH. Enzyme-substrate interactions with an antibiotic resistance enzyme: aminoglycoside nucleotidyltransferase(2”)-Ia characterized by kinetic and thermodynamic methods. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11581–91. doi: 10.1021/bi050797c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He B, Wilson EM. Electrostatic modulation in steroid receptor recruitment of LXXLL and FXXLF motifs. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;23:2135–50. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.6.2135-2150.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts JF, Lin LN. Rapid measurement of binding constants and heats of binding using a new titration calorimeter. Anal. Biochem. 1989;179:131–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldberg RN, Kishore N, Lennen RM. Thermodynamic Quantities for the Ionization Reactions of Buffers. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 2002;31:231–370. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukada H, Takahashi K. Enthalpy and heat capacity changes for the proton dissociation of various buffer components in 0.1 M potassium chloride. Proteins. 1998;33:159–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy KP, Freire E. Thermodynamics of structural stability and cooperative folding behavior in proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 1992;43:313–61. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60556-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spolar RS, Livingstone JR, Record MT., Jr. Use of liquid hydrocarbon and amide transfer data to estimate contributions to thermodynamic functions of protein folding from the removal of nonpolar and polar surface from water. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3947–55. doi: 10.1021/bi00131a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker BM, Murphy KP. Evaluation of linked protonation effects in protein binding reactions using isothermal titration calorimetry. Biophys. J. 1996;71:2049–55. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomez J, Freire E. Thermodynamic mapping of the inhibitor site of the aspartic protease endothiapepsin. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;252:337–50. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi HS, Chung M, Tzameli I, Simha D, Lee YK, Seol W, Moore DD. Differential transactivation by two isoforms of the orphan nuclear hormone receptor CAR. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:23565–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson BA, Wilson EM, Li Y, Moller DE, Smith RG, Zhou G. Ligand-induced stabilization of PPARgamma monitored by NMR spectroscopy: implications for nuclear receptor activation. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:187–94. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore LB, Parks DJ, Jones SA, Bledsoe RK, Consler TG, Stimmel JB, Goodwin B, Liddle C, Blanchard SG, Willson TM, Collins JL, Kliewer SA. Orphan nuclear receptors constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor share xenobiotic and steroid ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:15122–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heyman RA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Dyck JA, Stein RB, Eichele G, Evans RM, Thaller C. 9-cis retinoic acid is a high affinity ligand for the retinoid X receptor. Cell. 1992;68:397–406. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90479-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shulman AI, Larson C, Mangelsdorf DJ, Ranganathan R. Structural determinants of allosteric ligand activation in RXR heterodimers. Cell. 2004;116:417–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00119-9. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Germain P, Iyer J, Zechel C, Gronemeyer H. Co-regulator recruitment and the mechanism of retinoic acid receptor synergy. Nature. 2002;415:187–92. doi: 10.1038/415187a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurokawa R, DiRenzo J, Boehm M, Sugarman J, Gloss B, Rosenfeld MG, Heyman RA, Glass CK. Regulation of retinoid signalling by receptor polarity and allosteric control of ligand binding. Nature. 1994;371:528–31. doi: 10.1038/371528a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Forman BM, Umesono K, Chen J, Evans RM. Unique response pathways are established by allosteric interactions among nuclear hormone receptors. Cell. 1995;81:541–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sturtevant JM. Heat capacity and entropy changes in processes involving proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:2236–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.6.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spolar RS, Record MT., Jr. Coupling of local folding to site-specific binding of proteins to DNA. Science. 1994;263:777–84. doi: 10.1126/science.8303294. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myers JK, Pace CN, Scholtz JM. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 1995;4:2138–48. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041020. [erratum appears in Protein Sci 1996 May;5(5):981] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee KH, Xie D, Freire E, Amzel LM. Estimation of changes in side chain configurational entropy in binding and folding: general methods and application to helix formation. Proteins. 1994;20:68–84. doi: 10.1002/prot.340200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.