Abstract

Oncogenic tyrosine kinases, such as BCR-ABL, TEL-ABL, TEL-PDGFβR, and FLT3-ITD, play a major role in the development of hematopoietic malignancy. They activate many of the same signal transduction pathways. To identify the critical target genes required for transformation in hematopoietic cells, we used a comparative gene expression strategy in which selective small molecules were applied to 32Dcl3 cells that had been transformed to factor-independent growth by these respective oncogenic alleles. We identified inhibitor of DNA binding 1 (Id1), a gene involved in development, cell cycle, and tumorigenesis, as a common target of these oncogenic kinases. These findings were prospectively confirmed in cell lines and primary bone marrow cells engineered to express the respective tyrosine kinase alleles and were also confirmed in vivo in murine models of disease. Moreover, human AML cell lines Molm-14 and K562, which express the FLT3-ITD and BCR-ABL tyrosine kinases, respectively, showed high levels of Id1 expression. Antisense and siRNA based knockdown of Id1-inhibited growth of these cells associated with increased p27Kip1 expression and increased sensitivity to Trail-induced apoptosis. These findings indicate that Id1 is an important target of constitutively activated tyrosine kinases and may be a therapeutic target for leukemias associated with oncogenic tyrosine kinases.

Introduction

An emerging theme underlying human hematologic malignancies is the important role that oncogenic tyrosine kinases play in disease pathogenesis. In most cases, these activated kinases have been identified through the cloning of acquired recurring chromosomal translocations associated with leukemias. Examples include (1) the BCR-ABL,1–4 TEL-ABL,5,6 TEL-PDGFβR7–9 and TEL-JAK210–12 fusion proteins associated with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and chronic myelomonocytic (CMML) disease; (2) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) phenotypes associated with the BCR-ABL and the TEL-TRKC fusion proteins13; and (3) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) disease associated with TEL-JAK2.10 Moreover, constitutively activating internal tandem duplication (ITD) mutations within the juxtamembrane domain of the FLT3 receptor tyrosine kinase (FLT3-ITD) represent the single most common mutation in AML, emphasizing the importance of activated tyrosine kinases in hematopoietic neoplasms.14,15 In addition, activating mutations in tyrosine kinases play an important role in the pathogenesis of solid tumors including fibrosarcomas associated with TEL-TRKC,16 gastrointestinal stromal cell tumors,17,18 and non–small-cell lung cancer associated with mutations in EGFR.19,20 Structure-function relationships that are shared among tyrosine kinase fusion proteins include an amino terminal fusion partner that contains an oligomerization motif that is fused in frame to a carboxy-terminal tyrosine kinase domain. The amino terminal oligomerization motif may be contributed by a diverse group of partners that includes the coiled-coil domain in BCR and the SAM domain of TEL/ETV6. The respective tyrosine kinases are equally diverse and include both receptor tyrosine kinases such as PDGFβR and TRKC, as well as non-receptor tyrosine kinases such as ABL and JAK2. In each case, the amino terminal oligomerization domains result in constitutive activation of the tyrosine kinase fusion partner. Another shared feature among tyrosine kinase fusions is their cytoplasmic localization. Although the localization of the fusion proteins may be quite different from their native counterparts, all of the tyrosine kinase fusions are relocalized to the same subcellular compartment and presumably have access to a similar set of downstream targets for transformation.

Mutational analysis of each of the tyrosine kinase fusions has demonstrated that tyrosine kinase activation is required for transformation in vivo.6,8,12,16 Retroviral transduction of TEL-PDGFβR, TEL-JAK2, or TEL-TRKC into murine bone marrow cells results in a myeloproliferative disorder when transduced cells are transplanted into lethally irradiated syngeneic recipient mice.12,16,21 Introduction of point mutations that ablate tyrosine kinase activity of the TEL-PDGFβR, TEL-JAK2, or TEL-TRKC fusion abrogate the development of leukemia in bone marrow transplant (BMT) models. Collectively, these data demonstrate that kinase activation is critical for transformation.

Oncogenic tyrosine kinases activate many of the same signal transduction pathways. These include, but are not limited to, activation of the RAS/MAPK pathway, activation of members of the STAT family of transcription factors, activation of survival pathways including the PI3-K/AKT pathway, and recruitment of molecules that serve, in part, as scaffolds for assembly of signaling intermediates such as CRKL, CBL, and GAB2. Although activation of these signal transduction pathways has been studied extensively, few downstream target genes have been identified. For example, target genes that are expressed as a consequence of activation of Stat5 include Oncostatin M (OSM), Pim-1, Bcl-xL, and cyclin D1.22–24 Since Stat5 is a frequent target of activated tyrosine kinases, each of these Stat5 target genes has the potential to contribute to disease pathogenesis. For example, Oncostatin M is a cytokine that stimulates proliferation of myeloid lineage cells22,23; Pim-1 and Bcl-xL are survival factors whose expression is capable of potentiating a myeloproliferative phenotype25,26; and cyclin D1 overexpression has been reported in association with hematologic malignancies, especially those in which translocations occur at or near the cyclin D locus.27,28 Given the frequent involvement of oncogenic tyrosine kinases in hematopoietic malignancy, novel therapies designed to inhibit aberrantly activated tyrosine kinases and their downstream signaling pathways have been rapidly developing with much promise.

To identify target genes that are consistently up- or down-regulated by a comprehensive group of oncogenic tyrosine kinases, we transduced a murine myeloid progenitor cell line (32Dcl3) with retroviral vectors that expressed BCR-ABL, TEL-ABL, TEL-PDGFβR, or FLT3-ITD. These transduced cells were treated with specific kinase inhibitors (imatinib for BCR-ABL, TEL-ABL, TEL-PDGFβR; MLN518 for FLT3-ITD) and, using Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) oligonucleotide arrays, we compared the expression profiles of transduced cells treated with or without a specific kinase inhibitor, as well as cells treated with a nonspecific kinase inhibitor. Using this approach we identified Id1, a member of the helix-loop-helix (HLH) transcription factor family that lacks the basic domain,29–35 as a common downstream target of oncogenic tyrosine kinases. To determine the functional importance of Id1 in activated tyrosine kinase transduced hematopoietic cells, we knocked down the expression of Id1 by transfecting either Molm-14 or K562 cells with an antisense-Id1 retroviral construct or an Id1 siRNA lentiviral construct. Our results indicate that Id1 contributes to the proliferation and survival of oncogenic tyrosine kinase–transduced leukemia cells, and that Id1 may be important in the pathogenesis of hematologic malignancy caused by oncogenic tyrosine kinases.

Methods

Cell lines and cell culture

BaF3, 32Dcl3, K562, HL-60, and Molm-14 cells were maintained in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 1.0 ng/mL interleukin (IL)–3 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). TonB/BCR-ABL (gift from Dr George Daley, Children's Hospital, Boston, MA) and TonB/FLT3-ITD (gift from Dr James Griffin, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) were maintained in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS, 1 mg/mL G418, and 1.0 ng/mL IL-3.

DNA constructs and generation of cell lines stably expressing constitutively activated tyrosine kinases

Subcloning details of MSCV/BCR-ABL/neo, MSCV/TEL-ABL/neo, MSCV/TEL-PDGFβR/neo and MSCV/FLT3-ITD/neo constructs will be provided upon request. Stably expressing cell lines of each activated tyrosine kinase were generated by either electroporation or retroviral transduction.16 Transduced cells were selected in the absence of IL-3 and cultured in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS and 1 mg/mL G418. Full-length cDNA coding for mouse Id1 was cloned into an MSCV-puro retroviral vector as an HpaI fragment. The construct was sequenced to confirm its orientation. pBabe-Id1-AS plasmid, which contains a full-length Id1 cDNA in reverse orientation, was kindly provided by Dr Yong-Chuan Wong (The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China). An empty pBabe vector and a pBabe vector containing a full-length Id1 cDNA (pBabe-Id1-S) were used as controls. Stable transfectants of Molm14-Id-1AS, K562-Id-1AS, or HL60-mId1 were selected by limiting dilution in 96-well plates with 1 μg/mL puromycin. Lentiviral vectors expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) and a short hairpin RNA against Id1 (si-Id1) and luciferase (si-GL) were kindly provided by Dr Katharina Wagner (Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany).

Preparation of labeled cRNA and oligonucleotide microarray

To completely inhibit kinase activity in a short period of time (4 hours), a concentration of inhibitor that was at least 10 times higher than the IC50 for its respective activated tyrosine kinase was used (5 μM for imatinib,36 0.5 μM for MLN51837). Total RNA (10 μg) was reverse-transcribed with Superscript Choice System cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) in the presence of an oligodT-T7 primer (GENSET, La Jolla, CA). The cDNA then used for in vitro transcription with the BioArray Highyield RNA Transcript Labeling Kit (ENZO Diagnostics, Farmingdale, NY). Fifteen micrograms of labeled cRNA were fragmented by incubation at 95°C for 35 minutes in fragmentation buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate [pH 8.1], 100 mM KOAc and 30 mM MgOAc). The fragmented cRNA was hybridized against the Affymetrix Murine Genome U74v2 set oligonucleotide arrays at the MIT CCR HHMI Biopolymers Laboratory (MIT, Cambridge, MA). The arrays were analyzed using GeneCluster 2.0 software (Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard Center for Genome Research, Cambridge, WA).

Data were preprocessed so that absolute values were between 20 and 16 000. A variation filter was applied to the data so that the ratio of maximum value to minimum value was greater than 3, and the difference between maximum value and minimum value was greater than 100 in the same row. The filtered datasets were then analyzed by neighborhood analysis to identify genes of interest. The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE11794.38 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi.acc-GSE11794; accessed on July 12, 2008).

RT-PCR analysis

To quantify the expression of Id1 and Id2 mRNA, quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was carried out using the iCycler System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with Quantitect SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Each cDNA was normalized against glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), which served as an internal control. The primer sequences will be provided upon request.

Antibodies

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to Id1 (C-20), Id2 (C-20), FLT3 (M-20), Stat5b (C-17), and p27 (C-19), as well as mouse monoclonal antibodies to c-Abl (24-11) and RACK1 (B-3), were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit polyclonal antibody to PDGFβR (C-terminus) was from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to Phospho-Stat5 (Tyr694) and PARP were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Secondary antibodies used were HRP-conjugated anti–rabbit IgG and HRP-conjugated anti–mouse IgG from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom).

Assays for cell proliferation

Cells were plated at a density of 105 cells/mL in 24-well plates. Cell proliferation assays were carried out using a Benchmark Microplate Reader (Bio-Rad) with the CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell-cycle and apoptosis measurements

Cell-cycle analysis was performed using CycleTEST plus DNA Reagent Kit according to manufacturer's instructions (BD Pharmingen) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Flow data were analyzed by ModFit LT software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME).

Apoptosis analysis was performed using the Annexin-V-Fluos Staining Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

Results

Specific inhibition of oncogenic tyrosine kinases by imatinib or MLN518

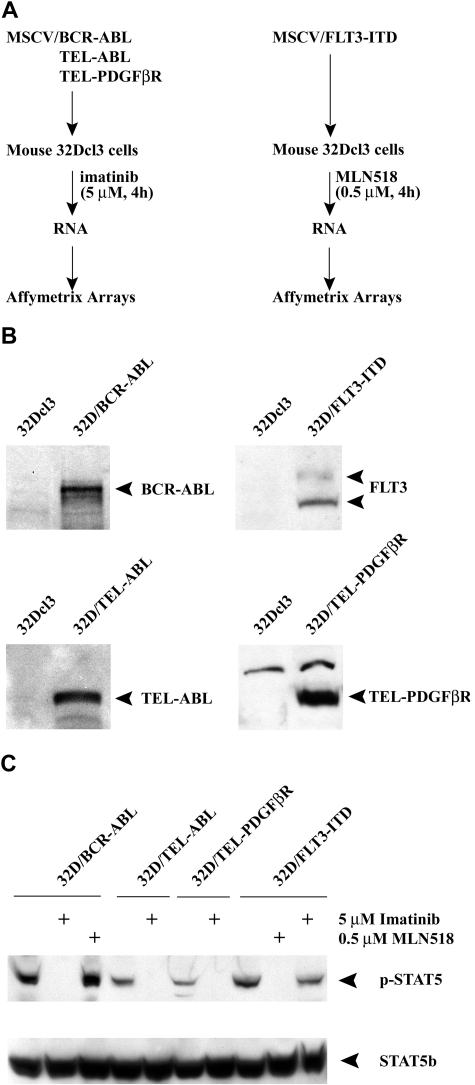

To identify common target genes regulated by constitutively activated tyrosine kinases, we transfected murine 32Dcl3 cell lines with MSCV-neo retroviral vectors expressing BCR-ABL, TEL-ABL, TEL-PDGFβR, or FLT3-ITD. Stable expression of each activated tyrosine kinase was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 1B). Cell lines transfected with each of these tyrosine kinases conferred IL-3–independent growth. In contrast, parental 32Dcl3 cells underwent apoptosis in the absence of IL-3 (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors specifically block the activity of oncogenic tyrosine kinases. (A) The experimental design to evaluate the common target genes of oncogenic tyrosine kinases by specific inhibitors (imatinib and MLN518) is shown schematically. (B) Western blot analysis of murine 32Dcl3 cells transduced with various oncogenic tyrosine kinases using c-Abl, FLT3, or PDGFβR antibodies. Untransduced 32Dcl3 cells were used as a negative control. (C) Western blot analysis of transduced 32Dcl3 cells treated with either imatinib or MLN518 using a Phospho-Stat5 (Tyr694; top panel) or Stat5b antibody (bottom panel). 32D/BCR-ABL cells treated with MLN518 or 32D/FLT3-ITD cells treated with imatinib were used as a negative control.

Stat5, a frequent target of activated tyrosine kinases,10,12,39,40 was used as a surrogate marker to confirm the specificity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Since phosphorylation on residue Tyr694 is obligatory for Stat5 activation,41,42 we performed Western blot analysis with phospho-specific STAT5 (Tyr694) or STAT5b-specific antibodies on whole cell lysates harvested from cells expressing each activated tyrosine kinase treated with either imatinib (a selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor for BCR-ABL, TEL-ABL and TEL-PDGFβR) or MLN518 (a selective inhibitor of FLT3 and PDGFR tyrosine kinases, but not ABL37; Figure 1C). Imatinib inhibited phosphorylation of Stat5 in cells transfected with BCR-ABL, TEL-ABL, or TEL-PDGFβR, but not in cells stably transfected with FLT3-ITD. In contrast, MLN518 selectively inhibited phosphorylation of Stat5 in cells transfected with FLT3-ITD.

Identification of target genes regulated by tyrosine kinase inhibitors

To study the early events in transcriptional regulation after tyrosine kinase inhibition, we harvested RNA samples 4 hours after treatment with inhibitors (Figure 1A). Genes that were up- or down-regulated by treatment with inhibitors based on experiments performed in triplicate are shown in Table 1. Genes repressed by treatment with inhibitors were considered as potential target genes that are up-regulated by activated tyrosine kinases. Within this list, there were several known transcriptional targets of activated tyrosine kinases, including c-Myc, Bcl-xL, Pim1, and Pim2.

Table 1.

Genes regulated by tyrosine kinase inhibitors

| Gene | Accession no. | Fold change (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| imatinib (32D/BCR-ABL) | MLN518 (32D/FLT3-ITD) | ||

| Genes induced by inhibitors | |||

| Topoisomerase-inhibitor suppressed | D86344 | 5.5 (0.3) | 6.7 (0.8) |

| Mad4 | U32395 | 4.3 (0.3) | 3.9 (0.2) |

| Cdk4 and Cdk6 inhibitor p19 | U19597 | 2.0 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.6) |

| Eyes absent 2 homolog | U81603 | 2.9 (0.6) | 2.9 (0.5) |

| Mnk2 | Y11092 | 2.1 (0.4) | 2.4 (0.3) |

| cyclin G2 | U95826 | 10.1(4.6) | 6.0 (2.2) |

| Mbd4 | AF072249 | 2.2 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.5) |

| Ecotropic viral integration site 2 | M34896 | 3.7 (1.3) | 2.8 (0.9) |

| G protein signaling regulator RGS2 | U67187 | 3.3 (1.3) | 6.5 (1.9) |

| Hemopoietic cell phosphatase | M68902 | 1.5 (0.2) | 2.2 (0.2) |

| Genes repressed by inhibitors | |||

| Cytokine inducible SH2-containing protein | D89613 | −7.0 (1.0) | −4.3 (0.6) |

| Inhibitor of DNA binding1 | M31885 | −49.0 (6.4) | −4.8 (0.9) |

| eIF-1A | AF026481 | −3.1 (0.6) | −3.1 (0.6) |

| Myelocytomatosis oncogene | L00039 | −11.8 (4.8) | −5.5 (0. 9) |

| Bcl2-like | L35049 | −3.2 (0.6) | −2.2 (0.3) |

| SIK similar protein | AF053232 | −2.6 (0.7) | −3.2 (0.6) |

| schlafen2 | AF099973 | −4.0 (0.5) | −2.8 (0.5) |

| cyclin D2 | M83749 | −7.0 (1.8) | −6.9 (1.7) |

| Proviral integration site 1 | M13945 | −7.8 (3.3) | −14.0 (2.9) |

| interleukin-4 receptor (secreted form) | M27960 | −2.2 (0.2) | −4.8 (0.5) |

| proliferation-associated protein 1 | U43918 | −2.6 (0.3) | −2.9 (0.6) |

| protein-serine/threonine kinase (pim-2) | L41495 | −5.0 (2.0) | −7.4 (1.3) |

Murine 32Dcl3 cells transduced with BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD were treated with either imatinib or MLN518 for 4 hours. Transcriptional profiles were analyzed using Affymetrix U74 oligonucleotide arrays. Data are from 3 independent experiments. Gene selection criteria: (1) Gene cluster software analysis showed P < .005. (2) Gene is among the top 200 most differentially expressed genes.

“Fold change” indicates the average change in gene expression between samples treated with specific inhibitors and samples treated with nonspecific inhibitors or without any inhibitors; and SD, standard deviation.

Expression of Id1 is down-regulated by specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors

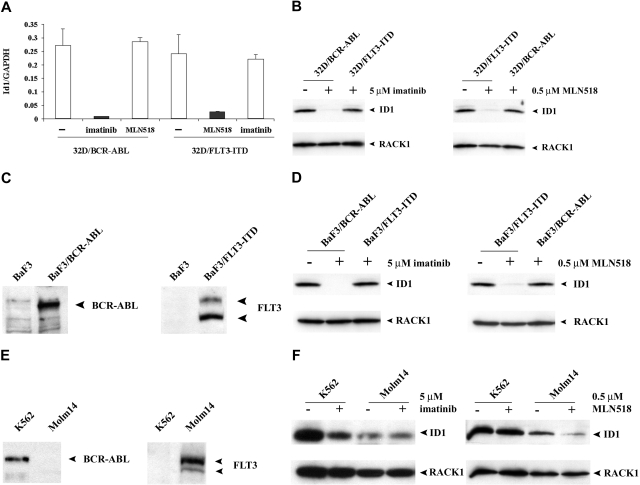

We observed that expression of the transcriptional repressor Id1 was significantly decreased after treatment of either 32D/BCR-ABL with imatinib or 32D/FLT3-ITD with MLN518. Id1 is a member of the Id family of proteins that are involved in cell growth, differentiation, and tumorigenesis.34,35 To verify the results observed in the oligonucleotide arrays, we analyzed the change in gene expression using real-time RT-PCR to quantify the levels of Id1 (Figure 2A). Similar down-regulation of Id1 was observed when comparing RT-PCR with microarray data (29.2-fold for imatinib and 8.5-fold for MLN518, respectively). Consistent with RT-PCR results, Western blot analysis also showed significantly decreased expression of Id1 protein in cells treated with specific inhibitors (Figure 2B). To determine whether down-regulation of Id1 by inhibitors was observed in cellular contexts other than 32Dcl3 cells, stable Ba/F3 cell lines were generated by retroviral transduction with MSCV-neoretroviral vectors expressing either BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD, respectively. Stable expression of BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 2C). As expected, treatment of either Ba/F3-BCR-ABL with imatinib or Ba/F3-FLT3-ITD with MLN518 resulted in markedly decreased expression of Id1 protein by Western blot analysis (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Expression of Id1 is specifically down-regulated by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. (A) Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis of transduced 32Dcl3 cells treated with either imatinib or MLN518 using Id1-specific primer. Results were normalized against the expression level of GAPDH. 32D/BCR-ABL cells treated with MLN518 or 32D/FLT3-ITD cells treated with imatinib were used as a negative control. (B) Western blot analysis of transduced 32Dcl3 cells treated with either imatinib or MLN518 using Id1 antibody. 32D/BCR-ABL cells treated with MLN518 or 32D/FLT3-ITD cells treated with imatinib were used as a negative control. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with a RACK1 antibody as a loading control. (C) Western blot analysis of murine BaF3 cells transduced with either BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD using c-Abl or FLT3 antibody. Untransduced BaF3 cells were used as a negative control. (D) Western blot analysis of transduced BaF3 cells treated with either imatinib or MLN518 using Id1 antibody. BaF3/BCR-ABL cells treated with MLN518 or BaF3/FLT3-ITD treated with imatinib were used as a negative control. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading control. (E) Western blot analysis of K562 cells and Molm-14 cells using c-Abl or FLT3 antibody. (F) Western blot analysis of K562 cells treated with imatinib or Molm-14 cells treated with MLN518 using Id1 antibody. K562 cells treated with MLN518 or Molm-14 cells treated with imatinib were used as a negative control. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading control.

To extend this finding to human leukemia cell lines, we next examined expression of Id1 in response to specific inhibitors in either K562 or Molm-14 cells that express the BCR-ABL fusion protein or FLT3-ITD, respectively.43,44 Expression of the respective oncogenic tyrosine kinases in each cell line was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 2E). Treatment of K562 cells with imatinib or Molm-14 cells with MLN518 resulted in markedly decreased expression of Id1 proteins (Figure 2F). Taken together, these findings indicate that Id1 is a target gene of both BCR-ABL and FLT3-ITD in human AML cells.

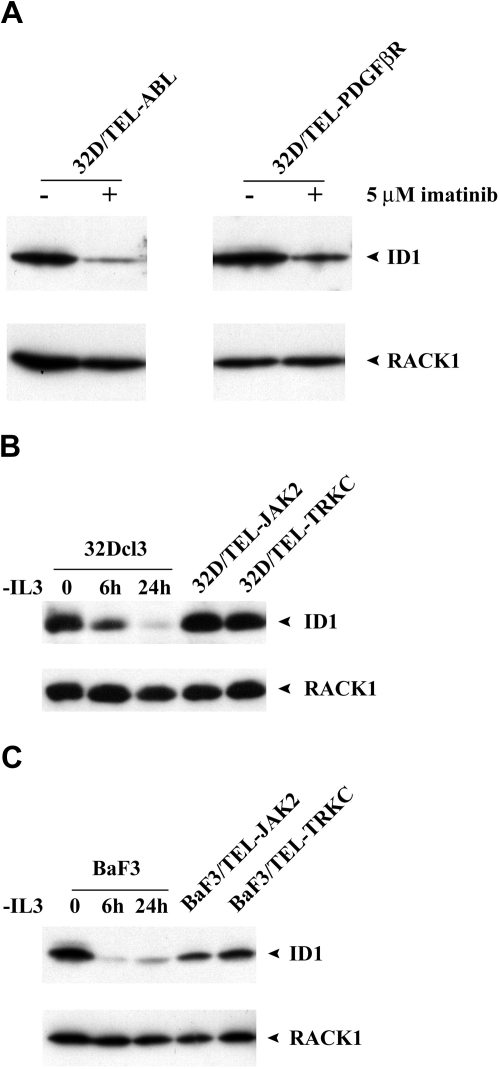

Id1 is a common downstream target of various oncogenic tyrosine kinases

To assess the expression of Id1 by other activated tyrosine kinases, we treated 32D/TEL-ABL or 32D/TEL-PDGFβR with imatinib (5 μM, 4 hours). Western blot analysis showed decreased expression of Id1 upon treatment of imatinib (Figure 3A). We next transfected 32Dcl3 cells with either TEL-JAK2 or TEL-TRKC. Stable expression of each activated tyrosine kinase was confirmed by Western blot (data not shown). Each of these conferred IL-3–independent growth. As shown in Figure 3B, expression of Id1 in a 32Dcl3 cell line expressing either TEL-JAK2 or TEL-TRKC was significantly higher than that of parental 32Dcl3 cells after withdrawal of IL-3 for either 6 or 24 hours. We observed similar results when we compared the expression of Id1 in Ba/F3 cells expressing either TEL-JAK2 or TEL-TRKC to that of parental Ba/F3 cells after withdrawal of IL-3 for either 6 or 24 hours (Figure 3C). Our data thus indicate that Id1 is a common downstream target for various activated tyrosine kinases.

Figure 3.

Expression of Id1 is up-regulated in other activated tyrosine kinases. (A) Western blot analysis of either BaF3/TEL-ABL or BaF3/TEL-PDGFβR cells treated with imatinib using Id1 antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading control. (B) Comparison of Id1 expression between parental 32Dcl3 cells deprived of IL3 for 6 or 24 hours and 32D/TEL-JAK2 or 32D/TEL-TRKC cells by Western blot analysis using Id1 antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading control. (C) Comparison of Id1 expression between parental BaF3 cells deprived of IL3 for 6 or 24 hours and BaF3/TEL-JAK2 or BaF3/TEL-TRKC cells by Western blot analysis using Id1 antibody. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading control.

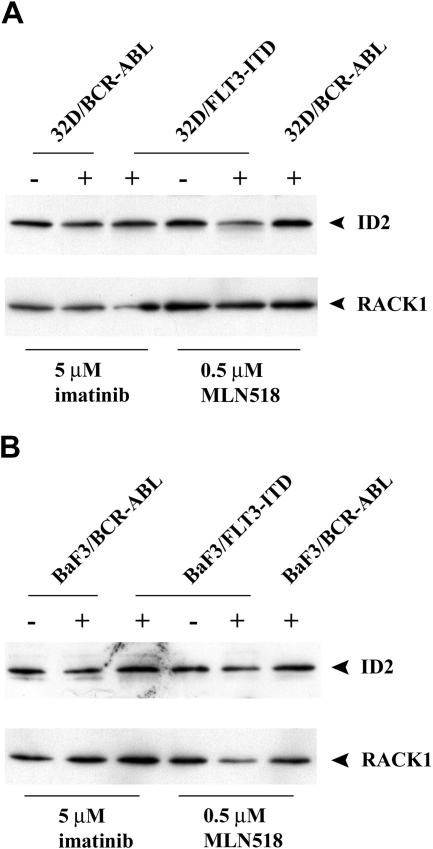

In contrast to Id1, we did not see a consistent change in Id2 levels in cell lines expressing different oncogenic tyrosine kinases. As shown in Figure 4A,B, treatment of 32D or Ba/F3 cells expressing BCR-ABL with imatinib did not change the level of Id2 protein, but inhibition of FLT3-ITD activity with MLN518 in 32D or Ba/F3 cells resulted in somewhat decreased Id2 expression. When we queried ID2 expression levels in public oncomine databases, we did not observe an increase, but rather a decrease in ID2 mRNA level in human leukemic patients harboring FLT3-ITD mutations as compared with patients with other non–FLT3-ITD mutations (P = .001; data not shown). It should be noted other as yet unknown kinase mutations may be present in the non–FLT3-ITD patient group that could potentially influence expression of either ID1 or ID2. Nonetheless, in a comparison of ID1 and ID2 levels in FLT3-ITD AML patients compared with all others, we observed a statistically significant difference only in the ID1 levels.

Figure 4.

Treatment of tyrosine kinase inhibitors on expression of Id2. (A) Western blot analysis of transduced 32Dcl3 cells treated with either imatinib or MLN518 using Id2 antibody. 32D/BCR-ABL cells treated with MLN518 or 32D/FLT3-ITD cells treated with imatinib were used as a negative control. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading control. (B) Western blot analysis of transduced BaF3 cells treated with either imatinib or MLN518 using Id2 antibody. BaF3/BCR-ABL cells treated with MLN518 or BaF3/FLT3-ITD treated with imatinib were used as a negative control. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading control.

Id1 expression is increased by oncogenic tyrosine kinases

The foregoing analysis was restricted to assessing patterns of gene expression after inhibition of constitutively activated tyrosine kinases with specific small molecule inhibitors. To determine whether these respective activated tyrosine kinases directly up-regulate the expression of Id1, we generated Ba/F3 cells that inducibly expressed either BCR-ABL (TonB/BCR-ABL) or FLT3-ITD (TonB/ FLT3-ITD) under the control of a tetracycline responsive element. Ba/F3 requires IL-3 for growth and viability, and undergoes apoptosis after IL-3 withdrawal for more than 24 hours.45 We observed that IL-3 could also up-regulate the expression of Id1 in Ba/F3 cells (Figure 3C). In control experiments, we determined that IL-3 withdrawal for 15 hours, followed by induction of BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD expression with doxycycline, was optimal to achieve basal levels of Id1 expression without induction of apoptotic cell death (data not shown). As indicated in the top panel of Figure 5A, we observed doxycycline-inducible expression of either BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD at 24 and 48 hours after addition of doxycycline. To confirm that the expressed proteins were functional, Western blot analysis of STAT5, a known target for phosphorylation by the spectrum of constitutively activated tyrosine kinases, with phospho-specific Stat5 (Tyr694) showed increased phosphorylation of Stat5 at Tyr694 (Figure 5A bottom panel).

Figure 5.

Id1 expression is increased after inducible expression of either BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD. (A) TonB/BCR-ABL or TonB/FLT3-ITD cells were deprived of IL-3 for 15 hours before adding doxycycline (2 μg/mL). Whole cell lysates were harvested at the time point indicated and analyzed by Western blot using either c-Abl or FLT3 antibody (top panel). The membranes were reblotted with a Phospho-Stat5 (Tyr694) antibody (bottom panel). (B) Total RNA and whole cell lysates were harvested at 48 hours after addition of doxycycline (2 μg/mL). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Id1 expression in inducible cell lines using Id1 specific primers (left). The results were normalized against the expression level of GAPDH. The corresponding Western blot analysis using Id1 antibody is listed on the right. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading controls. (C) Total RNA and whole cell lysates were harvested at 48 hours after addition of doxycycline (2 μg/mL). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis of Id2 expression in inducible cell lines using Id2 specific primers (left). The results were normalized against the expression level of GAPDH. The corresponding Western blot analysis using Id2 antibody is listed on the right. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading control. (D) Total RNA was isolated from spleens of mice that developed myeloproliferative disease. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed using Id1-specific primers. The results were normalized against the expression level of GAPDH. Total RNA from normal spleen was used as a negative control. (E) Total RNA was isolated from FACS-sorted GFP-positive primary murine bone marrow cells transduced with retroviral vectors coexpressing GFP alone, or GFP with either BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD.

We next investigated whether induced expression of either BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD resulted in up-regulation of Id1 expression. First, we used real-time RT-PCR to quantify the level of Id1 mRNA (Figure 5B left panel). There was a 6.3-fold or 3.0-fold increased expression of Id1 mRNA for TonB/BCR-ABL or TonB/FLT3-ITD, respectively, after doxycycline induction. In concordance with RT-PCR results, Western blot analysis also showed increased expression of Id1 protein (Figure 5B right panel). However, inducible expression of either BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD did not have a consistent change in either mRNA or protein levels of Id2 (Figure 5C). These data indicate that Id1 is indeed a bona fide downstream target of these activated tyrosine kinases.

We next assessed Id1 expression in vivo in primary cells from mice with myeloproliferative disease induced by the aforementioned oncogenic tyrosine kinases in bone marrow transplantation (BMT) assays. Bone marrow transplantations were performed after transduction of murine bone marrow cells with retrovirus containing BCR-ABL, TEL-PDGFβR or FLT3-ITD, respectively. As previously reported, all animals developed a characteristic myeloproliferative disease.4,16,21,46 Total RNA was prepared from single cell suspensions from diseased spleens derived from these animals, and real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed. As shown in Figure 5D (left panel), there was approximately a 5- to 10-fold increase in the expression of Id1 in diseased spleens as compared with normal spleen. To further demonstrate that Id1 is up-regulated in primary bone marrow cells that express oncogenic tyrosine kinases, we analyzed Id1 expression by RT-PCR from sorted GFP positive primary bone marrow cells that coexpress GFP and either BCR-ABL or FLT3-ITD (Figure 5D right panel). Consistent with the result in Figure 5D (left panel), primary bone marrow cells expressing BCR-ABL or FL3-ITD demonstrated a 6-fold increase in Id1 levels as compared with the control (Figure 5D right panel). All of these results indicated that oncogenic tyrosine kinases result in expression of Id1 in vivo.

We also queried several gene-expression data sets to assess a potential correlation between the presence of constitutively activated tyrosine kinases and ID1 expression levels in primary human myeloid leukemia samples. These analyses revealed significantly higher ID1 expression levels in FLT3-ITD positive cases among AML patients with normal cytogenetics (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article),47 as well as a strong trend toward increased ID1 expression levels in FLT3-ITD positive patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia, the AML subtype with the highest incidence of activating FLT3 mutations (Figure S2; L.B., unpublished results, June 2008). Furthermore, ID1 mRNA levels are higher in patients with advanced-stage CML as compared with patients with chronic-phase CML.48 Together, these observations support the conclusion that various constitutively activated tyrosine kinases are associated with increased expression of ID1 in human myeloid leukemia. Finally, the hypothesis that ID1 may have a role in myeloid leukemogenesis is also supported by the recent finding that the ID1 gene is recurrently amplified and overexpressed in AML patients with complex cytogenetic abnormalities.49

Inhibition of Id1 expression by an antisense Id1 construct results in growth inhibition of human leukemia cells

We next tested the functional consequence of increased ID1 protein expression in 2 human leukemia cell lines, Molm-14 and K562, by generating stable cell lines that expressed an antisense Id1, or cell lines that expressed a siRNA-Id1. As shown in Figure 6A, 2 clones of each stable cell line were isolated with an approximately 60% to 70% reduction of ID1 protein expression compared with the parental cell line or the pBabe vector control cells (Figure 6A left and middle panels). Molm-14 and K562 cell lines transduced with lentivirus expressing siRNA-ID1 resulted in 80% to 90% reduction of ID1 protein expression from more than 95% of the infected cells (Figure 6A right panel; Figure S3). The siRNA-ID1 did not affect ID2 expression (Figure 6A right panel). Inhibition of ID1 expression resulted in a significant decrease in the rate of cell growth, which correlated with a reduction in ID1 expression levels (Figure 6B). Cell-cycle analysis showed that each antisense ID1 clone became arrested primarily in G1, as determined by propidium iodide staining and FACS analysis (Figure 6C left and middle panels). Cell-cycle arrest in G1 phase was more prominent in the cells with acute ID1 down-regulation by lentiviral siRNA-ID1 measured 4 days after infection (Figure 6C right panel).

Figure 6.

Effect of Id1 down-regulation on the growth of human leukemia cell lines. (A) Id1 expression in Molm-14 and K562 cells by Western blot analysis. The protein level of Id1 in stable antisense transfectant clones or transient si-RNA Id1 transfectant was expressed relative to that of parental cells by densitometry analysis. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading controls, or reblotted with ID2 antibody as nonspecific controls. (B) Growth curve of Molm-14 and K562 cells measured by CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay. Note that M1, M2 and Molm14-siId1 inhibit growth of Molm-14 cells, K1, K2, and K562-siId1 inhibit growth of K562 cells. Results shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Cell-cycle analysis of Molm-14 cells. Note that M1, M2, and Molm14-siId1 showed an increase in the G1 population. Representative experiments are shown here. (D) Western blot analysis of Molm-14 and K562 cells using p27Kip1 antibody. There is an approximately 2- to 3-fold increase of p27Kip1 protein in antisense transfectant clones, compared with parental cells or cells transduced with pBabe empty vector. The membrane was stripped and reblotted with RACK1 antibody as loading control.

Id1 has been demonstrated to oppose Ets-mediated activation of p16INK4a.50 The p16INK4a tumor suppressor protein functions as an inhibitor of Cdk4 and Cdk6, the cyclin-dependent kinases that initiate the phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein, pRb.51,52 We hypothesized that inhibition of Id1 would release its inhibitory effect on p16INK4a, with subsequent inhibition of cell-cycle progression. However, we did not detect expression of p16INK4a in both Molm-14 and K562 cells by Western blot analysis and real-time PCR experiments (data not shown). This is in consonance with reports that many leukemia cell lines contain homozygous p16INK4a gene deletions.53 We thus tested the possibility that Id1 might affect the levels of expression of other cell-cycle regulatory genes, such as the CDK inhibitor p27Kip1, which acts as a critical negative regulator of the cell cycle by inhibiting the activity of cyclin/cdk complexes during G0 and G1. Western blot analysis showed an increase of approximately 2- to 3-fold in p27Kip1 protein levels in antisense transfectant clones compared with the parental cell line or the pBabe vector control cells (Figure 6D). Thus, down-regulation of Id1 expression results in a decreased growth rate in human leukemia cell lines stably expressing an Id1 antisense oligonucleotide or transiently expressing a siRNA against Id1 that is associated with G0/G1 arrest and up-regulation of p27Kip1. Taken together, these data suggest that activated tyrosine kinases may promote cell proliferation by inhibiting protein expression of p27Kip1 through up-regulation of Id1.

Expression of Id1 protects leukemia cells from apoptosis

The K562 erythroleukemia cell line is normally resistant to Trail-induced apoptosis.54 To determine whether down-regulation of ID1 leads to increased sensitivity to Trail-induced apoptosis in K562 cells, we treated each of 2 antisense ID1 clones and the cells coexpressing siRNA-ID1 and GFP with the Trail ligand (5 ng/mL, 24 hours). Annexin V staining followed by flow analysis showed increased apoptosis in 2 Id1 knockdown clones compared with the parental cell line or pBabe vector control cells (Figure 7A left panel). Moreover, the percentage of GFP positive si-RNA-ID1 expressing cells decreased from 95% to 75% upon Trail ligand treatment as compared with cells without Trail ligand or cells expressing control siRNA-GL. These data further support the hypothesis that ID1 may protect K562 cells from Trail-induced apoptosis (Figure 7A right panel). In cells undergoing apoptosis, the 116-kDa polypolymerase (PARP) protein is specifically cleaved by caspase-3 and caspase-6 into a signature 85-kDa apoptotic fragment.55 Western blot analysis confirmed increased expression of 85-kDa PARP fragment only in ID1 stable knockdown clones (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Expression of Id1 protects leukemia cells from apoptosis. (A) Induction of apoptosis in K562 cells by Trail (5 ng/mL). Cells that exhibited annexin V staining were considered to be apoptotic. Percentage of GFP positive cells were shown in cells transiently transduced with lentiviral vectors coexpressing GFP and either siRNA-GL or siRNA-Id1. Results were derived from 2 independent experiments. (B) Western blot analysis of K562 cells using PARP antibody. An increased amount of 85-kDa fragment of PARP was observed in K1 and K2, compared with parental K562 cells or cells transduced with pBabe empty vector. (C) ID1 expression in HL60 cells by Western blot analysis. Note that ID1-transfected cells (H1 and H2) showed a significant increase in Id1 expression. (D) Induction of apoptosis in HL60 cells by serum starvation. Cells that displayed annexin V staining were considered to be apoptotic. Representative experiments are shown here. (E) Western blot analysis of HL60 cells (serum-starved for 72 hours) using PARP antibody. An increased amount of 85-kDa fragment of PARP was observed in parental HL60 cells and cells transduced with MSCV empty vector, compared with H1 or H2.

Recently, ID1 expression has been shown to promote cell survival in prostate cancer cells.56 To determine whether ID1 overexpression confers similar properties on leukemia cells, we stably transduced HL60 cells (that express very low endogenous levels of ID1; data not shown) with MSCV-neoretroviral vectors expressing murine Id1. As shown in Figure 7C, 2 clones that expressed high levels of murine Id1 protein were isolated. Cells expressing Id1 were resistant to apoptosis induced by serum starvation for 48 or 72 hours, respectively, as assessed by annexin V staining followed by flow cytometric analysis, compared with either the parental cell line or MSCV vector control cells (Figure 7D). Consistent with flow data, Western blot analysis confirmed the increased expression of 85-kDa PARP fragment only in the parental cell line and the MSCV vector control cells (Figure 7E). Taken together, these data indicate that up-regulation of Id1 by activated tyrosine kinases may protect cells from external stimuli that normally induce apoptosis.

Discussion

Oncogenic tyrosine kinases are frequently implicated in the pathogenesis of leukemia and other human cancers. Constitutive tyrosine kinase activation is essential for transformation by tyrosine kinase fusions in both cell culture systems and murine models of leukemia. Although there is overlap in the signaling pathways that are activated by oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases, relatively little is known about the key downstream target genes in hematopoietic cells.

In this study, we used specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors to identify critical target genes that are regulated by oncogenic tyrosine kinases. Using oligonucleotide microarrays, we identified genes that are either up- or down-regulated by selective small molecule inhibitors that target the ABL, PDGFβR, or FLT3 kinases. Genes induced by these inhibitors are presumably repressed by activated tyrosine kinases. Among them are Mad4, a Max-interacting transcriptional repressor,46 and MBD-4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene that acts as a caretaker of genomic fidelity at CpG sites.57 Conversely, genes repressed by inhibitors are likely to be activated by oncogenic tyrosine kinases. For example, we observed consistent down-regulation of c-Myc, Pim-1, Pim-2, and Bcl-xL upon treatment with inhibitors, suggesting that they may play a role in the pathogenesis of human hematologic malignancies. Among these genes, we detected a 5- to 50-fold reduction in Id1 expression when the cancer cells were treated with inhibitors. More importantly, we found that Id1 is up-regulated in all oncogenic tyrosine kinases tested, including BCR-ABL, Tel-ABL, Tel-PDGFβR, Tel-Jak2, Tel-TRKC, and Flt3-ITD. This suggests that Id1 may be a common downstream target of oncogenic tyrosine kinases. Our observation is consistent with other microarray studies in which Id1 expression is up-regulated in CML patients both in chronic phase and blast phase,58 as well as AML patients harboring AML-ETO59 and Flt3-ITD. It is noteworthy that patients with AML-ETO recurrently show activating mutations of the receptor tyrosine kinases such as Flt3, c-kit, or PDGFβR60–62

How might Id1 be commonly targeted by oncogenic tyrosine kinases? The up-regulation of Id1 by Flt3-ITD in the TonB cell line is impaired by small molecule inhibition of either the PI3K/AKt pathway with LY294002 or the JAK-STAT pathway (Figure S5), suggesting that downstream targets of Jak-Stat or PI3 kinase signaling may be involved in the regulation of Id1. Recently, Id1 was found to be a direct target of Foxo3a,63 a downstream effector of PI3 kinase signaling. Unphosphorylated Foxo3a is transcriptionally active and suppresses several genes involved in cellular proliferation and survival.64 Upon growth factor stimulation, Foxo3a is inactivated by phosphorylation via the PI3K/PKB signaling pathway, leading to the activation of the repressed target genes. Because expression of oncogenic tyrosine kinases often results in growth factor–independent activation of PI3K/AKT signal cascades,65 Id1 may be a key downstream effector to provide proliferative and survival advantage to leukemic cells. It is noteworthy that Id1 can be up-regulated by IL-3 signaling and that IL-3–independent growth is a hallmark of leukemic cell transformation.

Id proteins have been implicated in a variety of cellular processes, including cell growth, differentiation, angiogenesis, and neoplastic transformation.34,35,66 A growing body of work indicates that Id proteins are involved in the control of hematopoiesis. In murine bone marrow, the Id1 gene is down-regulated as cells mature, suggesting that the Id1 protein regulates the differentiation of immature hematopoietic cells to more mature forms.67 Up-regulation of ID1 in primary human CD34+ cells has been shown to correlate with inhibition of erythrocyte differentiation and induction of granulocyte differentiation.68 This is in agreement with previous observations that the enforced expression of ID1 protein blocks differentiation of K562 and murine erythroleukemia (MEL) cells.69 More recently, 2 studies indicated that Id1 is important for the maintenance of the long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells.70,71 It will be of interest to determine whether Id1 may play a role in sustaining the leukemic stem cell population.

To determine the biologic significance of activation of ID1 by oncogenic tyrosine kinases, we repressed the expression of ID1 protein in 2 leukemia cell lines expressing either BCR-ABL (K562) or FLT3-ITD (Molt-14). We observed growth inhibition in both cell lines when they were transduced with either an antisense ID1 construct or a siRNA-ID1 construct. This indicates that Id1 is important for cell proliferation mediated by oncogenic tyrosine kinases. Since many leukemia cells contain homozygous deletion of p16INK4a,53 down-regulation of Id1 could inhibit cell proliferation by affecting the expression of other cell-cycle regulating genes. It has been shown that inducible expression of p27Kip1 can inhibit proliferation of K562 cells.72 Our data demonstrate that down-regulation of the Id1 protein may release the repression of p27Kip1, thereby contributing to the growth inhibition we observed in our study. Furthermore, we also showed that activation of Id1 by oncogenic tyrosine kinases protects cells from apoptosis induced by Trail ligand or by serum starvation. These data may explain why K562 cells, which express high levels of ID1 protein, are normally resistant to apoptosis induced by death receptor ligands, such as Fas and Trail ligand.54,73 Our results also suggest a mechanism for leukemia cells to achieve clonal dominance in the bone marrow through relative resistance to normal death signals in the marrow milieu.

The identification of Id1 as a common target gene of oncogenic tyrosine kinase-dependent signaling in proliferation and cell survival strongly suggests that Id1 might serve as a novel therapeutic target in leukemia involving oncogenic tyrosine kinases. Repressing the expression of Id may render certain leukemia cells becoming sensitive to chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge valuable discussions with members of the Gilliland laboratory.

This work was supported in part by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (D.G.G.), and National Institutes of Health grants CA66996 and DK50654 (D.G.G.). D.G.G. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: W.F.T. and T.-L.G. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. J.C., B.H.L., and A.W. analyzed and interpreted the data. L.B., S.F., S.M., and T.R.G. contributed analytical tools and statistical analysis. D.G.G. designed research, analyzed data, and revised the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: D. Gary Gilliland, PhD, MD, Brigham & Women's Hospital, Children's Hospital Research Building, 1 Blackfan Circle, 5th Floor, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: ggilliland@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Daley GQ, Van Etten RA, Baltimore D. Induction of chronic myelogenous leukemia in mice by the P210bcr/abl gene of the Philadelphia chromosome. Science. 1990;247:824–830. doi: 10.1126/science.2406902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daley GQ, Van Etten RA, Baltimore D. Blast crisis in a murine model of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:11335–11338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Etten RA, Jackson P, Baltimore D. The mouse type IV c-abl gene product is a nuclear protein, and activation of transforming ability is associated with cytoplasmic localization. Cell. 1989;58:669–678. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elefanty AG, Hariharan IK, Cory S. bcr-abl, the hallmark of chronic myeloid leukaemia in man, induces multiple haemopoietic neoplasms in mice. EMBO J. 1990;9:1069–1078. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okuda K, Golub TR, Gilliland DG, Griffin JD. p210BCR/ABL, p190BCR/ABL, and TEL/ABL activate similar signal transduction pathways in hematopoietic cell lines. Oncogene. 1996;13:1147–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golub TR, Goga A, Barker GF, et al. Oligomerization of the ABL tyrosine kinase by the Ets protein TEL in human leukemia. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4107–4116. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golub TR, Barker GF, Lovett M, Gilliland DG. Fusion of PDGF receptor beta to a novel ets-like gene, tel, in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with t(5;12) chromosomal translocation. Cell. 1994;77:307–316. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll M, Tomasson MH, Barker GF, Golub TR, Gilliland DG. The TEL/platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor (PDGF beta R) fusion in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia is a transforming protein that self-associates and activates PDGF beta R kinase-dependent signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:14845–14850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jousset C, Carron C, Boureux A, et al. A domain of TEL conserved in a subset of ETS proteins defines a specific oligomerization interface essential to the mitogenic properties of the TEL-PDGFR beta oncoprotein. EMBO J. 1997;16:69–82. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lacronique V, Boureux A, Valle VD, et al. A TEL-JAK2 fusion protein with constitutive kinase activity in human leukemia. Science. 1997;278:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peeters P, Raynaud SD, Cools J, et al. Fusion of TEL, the ETS-variant gene 6 (ETV6), to the receptor-associated kinase JAK2 as a result of t(9;12) in a lymphoid and t(9;15:12) in a myeloid leukemia. Blood. 1997;90:2535–2540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwaller J, Frantsve J, Aster J, et al. Transformation of hematopoietic cell lines to growth-factor independence and induction of a fatal myelo- and lymphoproliferative disease in mice by retrovirally transduced TEL/JAK2 fusion genes. EMBO J. 1998;17:5321–5333. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eguchi M, Eguchi-Ishimae M, Tojo A, et al. Fusion of ETV6 to neurotrophin-3 receptor TRKC in acute myeloid leukemia with t(12;15)(p13;q25). Blood. 1999;93:1355–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakao M, Yokota S, Iwai T, et al. Internal tandem duplication of the flt3 gene found in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:1911–1918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokota S, Kiyoi H, Nakao M, et al. Internal tandem duplication of the FLT3 gene is preferentially seen in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome among various hematological malignancies. A study on a large series of patients and cell lines. Leukemia. 1997;11:1605–1609. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Q, Schwaller J, Kutok J, et al. Signal transduction and transforming properties of the TEL-TRKC fusions associated with t(12;15)(p13;q25) in congenital fibrosarcoma and acute myelogenous leukemia. EMBO J. 2000;19:1827–1838. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.8.1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279:577–580. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 2003;299:708–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1079666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomasson MH, Sternberg DW, Williams IR, et al. Fatal myeloproliferation, induced in mice by TEL/PDGFbetaR expression, depends on PDGFbetaR tyrosines 579/581. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:423–432. doi: 10.1172/JCI8902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chauhan D, Kharbanda SM, Ogata A, et al. Oncostatin M induces association of Grb2 with Janus kinase JAK2 in multiple myeloma cells. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1801–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grenier A, Dehoux M, Boutten A, et al. Oncostatin M production and regulation by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Blood. 1999;93:1413–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Groot RP, Raaijmakers JA, Lammers JW, Koenderman L. STAT5-Dependent CyclinD1 and Bcl-xL expression in Bcr-Abl-transformed cells. Mol Cell Biol Res Commun. 2000;3:299–305. doi: 10.1006/mcbr.2000.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moroy T, Grzeschiczek A, Petzold S, Hartmann KU. Expression of a Pim-1 transgene accelerates lymphoproliferation and inhibits apoptosis in lpr/lpr mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10734–10738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lilly M, Sandholm J, Cooper JJ, Koskinen PJ, Kraft A. The PIM-1 serine kinase prolongs survival and inhibits apoptosis-related mitochondrial dysfunction in part through a bcl-2-dependent pathway. Oncogene. 1999;18:4022–4031. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaandrager JW, Kluin P, Schuuring E. The t(11;14) (q13;q32) in multiple myeloma cell line KMS12 has its 11q13 breakpoint 330 kb centromeric from the cyclin D1 gene. Blood. 1997;89:349–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nanjangud G, Naresh KN, Nair CN, et al. Translocation (11;14)(q13;q32) and overexpression of cyclin D1 protein in a CD23-positive low-grade B-cell neoplasm. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1998;106:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(98)00033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benezra R, Davis RL, Lockshon D, Turner DL, Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christy BA, Sanders LK, Lau LF, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Nathans D. An Id-related helix-loop-helix protein encoded by a growth factor-inducible gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1815–1819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun XH, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Baltimore D. Id proteins Id1 and Id2 selectively inhibit DNA binding by one class of helix-loop-helix proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:5603–5611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.11.5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riechmann V, van Cruchten I, Sablitzky F. The expression pattern of Id4, a novel dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein, is distinct from Id1, Id2 and Id3. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:749–755. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.5.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Norton JD, Atherton GT. Coupling of cell growth control and apoptosis functions of Id proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2371–2381. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yokota Y, Mori S. Role of Id family proteins in growth control. J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:21–28. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruzinova MB, Benezra R. Id proteins in development, cell cycle and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:410–418. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carroll M, Ohno-Jones S, Tamura S, et al. CGP 57148, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, inhibits the growth of cells expressing BCR-ABL, TEL-ABL, and TEL-PDGFR fusion proteins. Blood. 1997;90:4947–4952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kelly LM, Yu JC, Boulton CL, et al. CT53518, a novel selective FLT3 antagonist for the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Cancer Cell. 2002;1:421–432. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: WCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ilaria RL, Jr, Van Etten RA. P210 and P190(BCR/ABL) induce the tyrosine phosphorylation and DNA binding activity of multiple specific STAT family members. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31704–31710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.49.31704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilbanks AM, Mahajan S, Frank DA, Druker BJ, Gilliland DG, Carroll M. TEL/PDGFbetaR fusion protein activates STAT1 and STAT5: a common mechanism for transformation by tyrosine kinase fusion proteins. Exp Hematol. 2000;28:584–593. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gouilleux F, Wakao H, Mundt M, Groner B. Prolactin induces phosphorylation of Tyr694 of Stat5 (MGF), a prerequisite for DNA binding and induction of transcription. EMBO J. 1994;13:4361–4369. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06756.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakao H, Gouilleux F, Groner B. Mammary gland factor (MGF) is a novel member of the cytokine regulated transcription factor gene family and confers the prolactin response. EMBO J. 1994;13:2182–2191. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06495.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuo Y, MacLeod RA, Uphoff CC, et al. Two acute monocytic leukemia (AML-M5a) cell lines (MOLM-13 and MOLM-14) with interclonal phenotypic heterogeneity showing MLL-AF9 fusion resulting from an occult chromosome insertion, ins(11;9)(q23;p22p23). Leukemia. 1997;11:1469–1477. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Florio M, Hernandez MC, Yang H, Shu HK, Cleveland JL, Israel MA. Id2 promotes apoptosis by a novel mechanism independent of dimerization to basic helix-loop-helix factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5435–5444. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daley GQ, Baltimore D. Transformation of an interleukin 3-dependent hematopoietic cell line by the chronic myelogenous leukemia-specific P210bcr/abl protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:9312–9316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kelly LM, Liu Q, Kutok JL, Williams IR, Boulton CL, Gilliland DG. FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations associated with human acute myeloid leukemias induce myeloproliferative disease in a murine bone marrow transplant model. Blood. 2002;99:310–318. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valk PJ, Verhaak RG, Beijen MA, et al. Prognostically useful gene-expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1617–1628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radich JP, Dai H, Mao M, et al. Gene expression changes associated with progression and response in chronic myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2794–2799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rucker FG, Bullinger L, Schwaenen C, et al. Disclosure of candidate genes in acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotypes using microarray-based molecular characterization. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3887–3894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohtani N, Zebedee Z, Huot TJ, et al. Opposing effects of Ets and Id proteins on p16INK4a expression during cellular senescence. Nature. 2001;409:1067–1070. doi: 10.1038/35059131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ruas M, Peters G. The p16INK4a/CDKN2A tumor suppressor and its relatives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1378:F115–177. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Quesnel B, Preudhomme C, Fenaux P. p16ink4a gene and hematological malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996;22:11–24. doi: 10.3109/10428199609051724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Pietro R, Secchiero P, Rana R, et al. Ionizing radiation sensitizes erythroleukemic cells but not normal erythroblasts to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)–mediated cytotoxicity by selective up-regulation of TRAIL-R1. Blood. 2001;97:2596–2603. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Ottaviano Y, Davidson NE, Poirier GG. Specific proteolytic cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase: an early marker of chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3976–3985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ling MT, Wang X, Ouyang XS, Xu K, Tsao SW, Wong YC. Id-1 expression promotes cell survival through activation of NF-kappaB signalling pathway in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:4498–4508. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bellacosa A. Role of MED1 (MBD4) Gene in DNA repair and human cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:137–144. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nowicki MO, Pawlowski P, Fischer T, Hess G, Pawlowski T, Skorski T. Chronic myelogenous leukemia molecular signature. Oncogene. 2003;22:3952–3963. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mulloy JC, Jankovic V, Wunderlich M, et al. AML1-ETO fusion protein up-regulates TRKA mRNA expression in human CD34+ cells, allowing nerve growth factor-induced expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4016–4021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404701102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuchenbauer F, Feuring-Buske M, Buske C. AML1-ETO needs a partner: new insights into the pathogenesis of t(8;21) leukemia. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1716–1718. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.12.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schnittger S, Kohl TM, Haferlach T, et al. KIT-D816 mutations in AML1-ETO-positive AML are associated with impaired event-free and overall survival. Blood. 2006;107:1791–1799. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grisolano JL, O'Neal J, Cain J, Tomasson MH. An activated receptor tyrosine kinase, TEL/PDGFbetaR, cooperates with AML1/ETO to induce acute myeloid leukemia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9506–9511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531730100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Birkenkamp KU, Essafi A, van der Vos KE, et al. FOXO3a induces differentiation of Bcr-Abl-transformed cells through transcriptional down-regulation of Id1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:2211–2220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lam EW, Francis RE, Petkovic M. FOXO transcription factors: key regulators of cell fate. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:722–726. doi: 10.1042/BST0340722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kharas MG, Fruman DA. ABL oncogenes and phosphoinositide 3-kinase: mechanism of activation and downstream effectors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2047–2053. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lasorella A, Uo T, Iavarone A. Id proteins at the cross-road of development and cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:8326–8333. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cooper CL, Brady G, Bilia F, Iscove NN, Quesenberry PJ. Expression of the Id family helix-loop-helix regulators during growth and development in the hematopoietic system. Blood. 1997;89:3155–3165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cammenga J, Mulloy JC, Berguido FJ, MacGrogan D, Viale A, Nimer SD. Induction of C/EBPalpha activity alters gene expression and differentiation of human CD34+ cells. Blood. 2003;101:2206–2214. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lister J, Forrester WC, Baron MH. Inhibition of an erythroid differentiation switch by the helix-loop-helix protein Id1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17939–17946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jankovic V, Ciarrocchi A, Boccuni P, DeBlasio T, Benezra R, Nimer SD. Id1 restrains myeloid commitment, maintaining the self-renewal capacity of hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1260–1265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607894104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perry SS, Zhao Y, Nie L, Cochrane SW, Huang Z, Sun XH. Id1, but not Id3, directs long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Blood. 2007;110:2351–2360. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-069914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Drexler HC, Pebler S. Inducible p27(Kip1) expression inhibits proliferation of K562 cells and protects against apoptosis induction by proteasome inhibitors. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:290–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Landowski TH, Shain KH, Oshiro MM, Buyuksal I, Painter JS, Dalton WS. Myeloma cells selected for resistance to CD95-mediated apoptosis are not cross-resistant to cytotoxic drugs: evidence for independent mechanisms of caspase activation. Blood. 1999;94:265–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.