Summary

Juvenile hormone (JH) and 20-hydroxy-ecdysone (20E) are highly versatile hormones, coordinating development, growth, reproduction, and aging in insects. Pulses of 20E provide key signals for initiating developmental and physiological transitions, while JH promotes or inhibits these signals in a stage-specific manner. Previous evidence suggests that JH and 20E might modulate innate immunity, but whether and how these hormones interact to regulate the immune response remains unclear. Here we show that JH and 20E have antagonistic effects on the induction of antimicrobial peptide (AMP) genes in Drosophila melanogaster. 20E pretreatment of S2* cells promoted the robust induction of AMP genes, following immune stimulation. On the other hand, JH III, and its synthetic analogs (JHa) methoprene and pyriproxyfen, strongly interfered with this 20E-dependent immune potentiation, although these hormones did not inhibit other 20E-induced cellular changes. Similarly, in vivo analyses in adult flies confirmed that JH is a hormonal immuno-suppressor. RNA silencing of either partner of the ecdysone receptor heterodimer (EcR or Usp) in S2* cells prevented the 20E-induced immune potentiation. In contrast, silencing methoprene-tolerant (Met), a candidate JH receptor, did not impair immuno-suppression by JH III and JHa, indicating that in this context MET is not a necessary JH receptor. Our results suggest that 20E and JH play major roles in the regulation of gene expression in response to immune challenge.

Keywords: Drosophila, innate immunity, humoral immune response, antimicrobial peptides, juvenile hormone, ecdysone, hormone receptors

Introduction

To defend themselves against infectious pathogens, insects like Drosophila use an innate immune system, a primary defense response evolutionarily conserved among metazoans (Janeway, 1989; Medzhitov and Janeway, 1998; Hoffmann and Reichhart, 2002; Tzou et al., 2002; Hoffmann, 2003). Insects have multiple effector mechanisms to combat microbial pathogens. Infection or wounding stimulates proteolytic cascades in the host, causing blood clotting and activation of a prophenoloxidase cascade leading to melanization. Cellular immunity involves haemocytes (blood cells) which mediate phagocytosis, nodulation, and encapsulation of pathogens. Systemic and local infections also induce a robust antimicrobial peptide (AMP) response. For example, in a systemic infection, AMPs are rapidly produced in the fat body (the equivalent of the mammalian liver) and secreted into the hemolymph (blood stream) (Gillespie et al., 1997; Kimbrell and Beutler, 2001; Hoffmann, 2003).

The molecular events initiating the transcriptional induction of AMP genes are well characterized (Silverman and Maniatis, 2001; Tzou et al., 2002; Hoffmann, 2003; Kaneko and Silverman, 2005). Upon infection, Drosophila recognizes pathogens using microbial pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as peptidoglycan recognition proteins (PGRPs) and gram-negative binding proteins (GNBPs). Binding of pathogen-derived molecules to these receptors activates two signaling cascades, the Toll pathway and the immune deficiency (IMD) pathway. While the Toll pathway responds to many gram-positive bacteria and fungal pathogens and activates the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factors Dorsal and Dif (Dorsal-related immunity factor), the IMD pathway responds to gram-negative bacteria, activating the NF-κB homolog Relish. Subsequently, these NF-κB factors induce the expression of a broad range of AMP genes effective against gram-negative and -positive bacteria (e.g., Attacin, Cecropin, Diptericin) and fungi (e.g., Drosomycin, Metchnikowin) (Engström, 1999; Lehrer and Ganz, 1999; Silverman and Maniatis, 2001; Tzou et al., 2002; Hoffmann, 2003). Because the immune system of insects has much in common with the innate immune response of mammals, Drosophila is an excellent model for studying the mechanisms of innate immunity (Silverman and Maniatis, 2001; Hoffmann and Reichhart, 2002).

Increasing evidence suggests that hormones and nuclear hormone receptors (NRs) systemically regulate adaptive and innate immunity in vertebrates (Rollins-Smith et al., 1993; Rollins-Smith, 1998; Webster et al., 2002; Glass and Ogawa, 2006; Pascual and Glass, 2006; Chow et al., 2007). In mammals, several NRs have been implicated in regulating innate immunity and proinflammatory gene expression, including peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), liver X receptors (LXRs), vitamin D receptors (VDRs), estrogren receptors (ERs), and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (Ricote et al., 1998; Beagley and Gockel, 2003; Joseph et al., 2003; Smoak and Cidlowski, 2004; Glass and Ogawa, 2005; Ogawa et al., 2005). For example, GR represses proinflammatory NF-κB targets, and VDR and its ligand 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 induce expression of the human AMPs cathelicidin (camp) and defensin β2 (defB2) (Wang et al., 2004; Glass and Ogawa, 2006; Schwab et al., 2007; Chow et al., 2007).

In contrast, little is known about the hormonal regulation of immunity in invertebrates such as insects. Several findings suggest that the steroid hormone 20-hydroxy-ecdysone (20E), an important regulator of development, metamorphosis, reproduction, and aging in insects (Nijhout, 1994; Kozlova and Thummel, 2000; Tu et al., 2006), modulates cellular and humoral innate immunity. In the mosquito Anopheles gambiae, 20E induces expression of prophenoloxidase 1 (PPO1), a gene containing ecdysteroid regulatory elements (Ahmed et al., 1999; Müller et al., 1999). In Drosophila melanogaster, 20E causes mbn-2 cells, a tumorous blood cell line, to differentiate into macrophages and to increase their phagocytic activity (Dimarcq et al., 1997), and injection of mid-third instar larvae with 20E increases the phagocytic activity of plasmatocytes (Lanot et al., 2001). 20E signaling is also required for Drosophila lymph gland development and hematopoiesis, both necessary for pathogen encapsulation (Sorrentino et al., 2002), and in flesh fly larvae (Neobelliera bullata), 20E promotes the nodulation reaction (Franssens et al., 2006). In terms of humoral immunity, 20E renders D. melanogaster mbn-2 cells and flies competent to induce AMP genes such as Diptericin (Dpt) and Drosomycin (Drs) (Meister and Richards, 1995; Dimarcq et al., 1997; Silverman et al., 2000). The ability to express Dpt in fly larvae depends on the developmental stage; Dpt expression could be induced by infection only after 3rd instar larvae were mature enough to produce sufficient 20E (Meister and Richards, 1995). 20E also promotes expression of the immunoglobin hemolin in the fat body of diapausing pupae of the Cecropia moth (Hyalophora cecropia) (Roxström-Lindquist et al., 2005). In contrast, 20E may also counteract immune function, since the Toll-ligand dorsal, the Toll-effector spätzle, and several AMPs were downregulated at the onset of Drosophila metamorphosis in a 20E-dependent manner in gene profiling studies (Beckstead et al., 2005). Similarly, 20E downregulates antibacterial activity in diapausing larvae of the blowfly (Calliphora vicina) (Chernysh et al., 1995). Thus, 20E might either induce or suppress innate immunity, depending on the developmental stage and immune response assayed.

While pulses of 20E provide signals for initiating developmental and physiological transitions (Kozlova and Thummel, 2000), juvenile hormone (JH) specifically promotes or inhibits 20E signaling in a stage-specific manner (Nijhout, 1994; Riddiford, 1994; Berger and Dubrovsky, 2005; Flatt et al., 2005). Recent results suggest that JH— like 20E —might modulate immunity in insects. In the tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta), JH inhibits granular phenoloxidase (PO) synthesis and thus prevents cuticular melanization (Hiruma and Riddiford, 1998); likewise, JH reduces PO levels and suppresses encapsulation in the mealworm beetle (Tenebrio molitor) (Rolff and Siva-Jothy, 2002; Rantala et al., 2003). In honeybees (Apis mellifera), JH-mediated downregulation of the yolk precursor vitellogenin reduces haemocyte number (Amdam et al., 2004), and in flesh fly larvae (Neobelliera bullata), JH suppresses the 20E induced nodulation reaction (Franssens et al., 2006). These findings suggest that 20E is typically a positive regulator of innate immunity, while JH acts as an immuno-suppressor (Flatt et al., 2005). Although JH induces expression of the AMP Ceratotoxin A in female accessory glands of the medfly (Ceratitis capitata), this peptide is not induced by bacterial infection (Manetti et al., 1997). Thus, it remains unclear how JH affects the expression of pathogen-inducible AMPs in humoral immunity. Furthermore, whether and how 20E and JH interact to regulate AMP expression has not been investigated.

Here we demonstrate that 20E promotes humoral immunity by potentiating AMP induction in D. melanogaster, but that this 20E-induced response is specifically and strongly inhibited by JH and juvenile hormone analogs (JHa). We further show that immune induction by 20E requires ecdysone receptor (EcR) / ultraspiracle (USP), but that immune suppression by JH is independent of the putative JH receptor methoprene-tolerant (MET).

Materials and methods

Hormones

For hormone application in S2* cells and flies we used the following compounds: 20-hydroxy-ecdysone [20E = (2β,3β,5β,22R)-2,3,14,20,22,25-hexahydroxycholest-7-en-6-one], Sigma, 1 mM stock solution in water; juvenile hormone III [JH III = “methyl epoxy farnesoate” = 10-epoxy-3,7,11-trimethyl-trans, trans-2,6-dodecadienoic acid methyl ester], isolated from Manduca sexta, Sigma, 3.7 mM stock in ethanol (for cell culture) and 187 mM stock in acetone (for topical treament of flies); the JH analog (JHa) methoprene [isopropyl-(2E,4E)-11-methoxy-3,7,11-trimethyl-2,4-dodeacdieonate], Sigma (PESTANAL, racemic mixture), 7.9 mM stock in ethanol; and the JHa pyriproxyfen [2-[1-methyl-2-(4-phenoxyphenoxy)-ethoxy]-pyridine], ChemService Inc., 6.4 mM stock in ethanol. For dose-response experiments, hormones were freshly prepared as stock solutions in ethanol; final dilutions in cell culture were in water with 0.01% ethanol. The JHa methoprene and pyriproxyfen are better soluble, more potent, and more resistant to in vivo degradation than JH III; JHa can act as faithful JH agonists, both in vivo and in vitro (Cherbas et al., 1989; Riddiford and Ashburner, 1991; Wilson, 2004; Zera and Zhao, 2004; Flatt and Kawecki, 2007). For details on hormone delivery, see below.

Drosophila stocks and culture

We used the yellow white (y, w) strain for the microarray experiment and the Northern blot on Diptericin mRNA (courtesy of Eric Rulifson); for the GFP reporter assays, we used the Drosomycin-GFP reporter strain DD1 ((y, w, P(ry+, Dpt-lacZ), P(w+, Drs-GFP); cn, bw) (Reichhart et al., 1992; Ferrandon et al., 1998; courtesy of Dominique Ferrandon) and the Diptericin-GFP reporter strain DIG (w; P(Dpt- GFP, w+)D3-2, P(Dpt-GFP, w+)D3-4) (Vodovar et al., 2005; courtesy of Bruno Lemaitre). Flies were reared on a standard fly food medium consisting of cornmeal/sugar/yeast/agar at 25°C, 40% relative humidity, and a 12-hour light-dark cycle.

Microarrays

To examine the transcriptional response of y, w flies to treatment with exogenous JH, we performed a microarray experiment on uninfected females treated with JH or solvent (control). Since the physiological effects of JH are better understood in females than males, we only used females in this experiment. Flies were grown on regular yeast diet, switched to no-yeast food within one hour of eclosion, and yeast-starved for 5 days posteclosion to lower their endogenous JH titer and to synchronize their physiology (cf. Tu and Tatar, 2003; Gershman et al., 2007). Subsequently, flies were anesthetized on ice and topically treated with 0.1 µl of 187 mM JH III in acetone or with 0.1 µl 100% acetone (control) using a 1 µl Hamilton syringe with a repeating dispenser. 12 hours after hormone administration, samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Total RNA from whole flies was isolated from samples (2 JH samples, 2 control samples, each with 30 females) by lysis, as previously described (Gershman et al., 2007). cDNA products were hybridized at the Brown University Genomics Core Facility to Affymetrix GeneChip Drosophila_1 Genome Arrays (2 replicate chips per treatment). The dataset consisted of 14,009 probe sets, with 6,142 probe sets annotated. Expression data were analyzed for significant over- or underrepresentation of gene ontology (GO) terms with the web application FatiGO (Al-Shahrour et al., 2004), using a two-fold change criterion. To test whether JH treatment significantly suppresses expression of AMPs we used t-tests implemented in JMP IN 5.1. (SAS Institute; Sall et al., 2004). The microarray dataset has been deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession number GSE9001. Results of the microarray experiment were confirmed by analyzing two additional, independent microarray experiments: one experiment on JH and solvent treated y, w females, following the time-course design of Gershman et al. (2007); the other experiment with S2* cells treated with solvent, JHa (methoprene), 20E, or both 20E and JHa (3 replicates each) (data not shown).

Fly GFP reporter experiments

To test whether the JHa methoprene suppresses AMP expression in vivo we used a whole fly green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter assay of the DD1 (Drs-GFP) and the DIG (Dpt-GFP) strains, combining hormonal manipulation (JHa application vs. control) with manipulation of infection status (unjabbed control; sterile, ethanol jabbed control; and bacteria jabbed). Each of the 2 (JHa, control) × 3 (unjabbed; EtOH jabbed; bacteria jabbed) treatment groups consisted of 15 three-day old females (total N = 90 females). Prior to manipulating infection status, flies were exposed for 24 hours in vials to vaporized JHa methoprene (10 µl at 7.9 mM) or 70% ethanol (control; 10 µl). The next day, flies were lightly anesthetized with moist CO2 and jabbed at the abdomen intersegment with a fine (0.2 mm diameter) Minuten pin needle (Fisher Scientific), dipped in live gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, strain 1106; bacterial pellets made by centrifugation of a liquid overnight culture in LB growth medium), in 70% ethanol (sterile jabbed control), or left unjabbed. 24 hours after infection, flies were anesthetized using CO2 and their GFP expression visualized under fluorescent (FITC) light with a Zeiss Stemi SV11 dissecting scope; images of individual flies were taken with an AxioCam MRm camera (Zeiss; exposure time: 5 seconds) and processed with AxioVision LE Rel. 4.3. software. For analysis, images were imported into ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). After thresholding images, surface areas of flies were estimated using the polygon selection tool. Image exposure time and threshold parameters were kept constant for all images. Data were analyzed with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) implemented JMP IN 5.1. (SAS Institute; Sall et al., 2004), using infection status and hormone treatment as fixed factors.

S2* cell culture and cell induction

For cell culture experiments we used an embryonic haemocyte- or macrophage-like Drosophila cell line known as Schneider S2* cells (Samaklovis et al., 1992). S2*cells were maintained at 25°C in Schneider S2 Drosophila medium (Gibco, Invitrogen) or Schneider’s Insect media (Sigma), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone), 1% GlutaMax-1 (Invitrogen), and 0.2% Penicillin-Streptomycin (Pen-Strep, Invitrogen). The Diptericin-luciferase cell line (Dpt-luc) was a stable S2* transfectant containing the reporter plasmid pJM648 (Tauszig et al., 2000; Kaneko et al., 2004); at each passage, cells were selected with Geneticin (G418 Sulfate, Gibco, Invitrogen, 800 µg/mL). Cell counts were made with a Fuchs-Rosenthal Ultraplane Counting Chamber (1/16 mm2; 2/10 mm deep; Hausser Scientific). For experiments, cells were immune stimulated with 1 µg/ml E. coli peptidoglycan (PGN; InvivoGen, 1 mg/ml stock) for 5–6 hours or left untreated (control). In one experiment (Fig. 5A), we used crude lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from E. coli (0111:B4; Sigma); the active Drosophila immune stimulating component of crude LPS has been shown to be PGN (Kaneko et al., 2004). For Northern or Western blotting without RNAi, cells were plated at 106 cells/ml in 6-well tissue culture plates (3 ml of cells per well); after 24 hours, cells were split to 106 cells/ml in 6-well plates (3 ml cells/well) and incubated with hormones (no hormone; 20E; JH or JHa; JH or JHa plus 20E). For each hormone, we added 3 µl of stock solution per well (see above; 1000x dilution). After 24 hours of hormone incubation, cells were stimulated with PGN for 5–6 hours or left unstimulated (control). For experiments with Dpt-luc cells, procedures were identical, except that cells were plated at 103 cells/µl in 96-well plates (100 µl cells/well); hormones were administered as 1 µl of stock per well (1000x dilution). Each cell culture experiment was replicated at least 4 times.

RNAi

To study the genetics of the hormonal response we performed RNAi-mediated silencing of Drosophila ecdysone receptor (EcR), ultraspiracle (Usp), and methoprene-tolerant (Met). Double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) were synthesized from a PCR-amplified template, with T7 promoter sequences flanking a ~ 500 base pair fragment of the gene of interest, using the Ribomax kit (Promega), as previously described (Silverman et al., 2000). dsRNA was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. As RNAi controls, we used dsRNA for E. coli LacZ (encoding β-galactosidase) or E. coli MalE (encoding maltose binding protein, MBP). Primers used to generate dsRNA are described in Supplementary Table S1. dsRNA for MalE was generated using the HiScribe RNAi Transcription Kit (New England BioLabs); a 808 bp (Bgl II - EcoR I) fragment of MalE was inserted into the Litmus 28i vector and amplified using the T7 minimal primer. For RNAi-mediated silencing, cells were plated at 106 cells/ml (see above) and then soaked with 30 µg of dsRNA in 1 ml FBS-free medium for 30 minutes, followed by addition of 2 ml of complete medium. 24 hours later, cells were split to 106 cells/ml in 6-well plates (for Northern and Western blotting) or plated at 103 cells/µl in 96-well plates (for luciferase assays); subsequently, cells were treated with hormones and immune stimulated, as described above.

Luciferase reporter assays

To examine how hormones affect Dpt promoter activity, we performed luciferase assays with Dpt-luc reporter cells in 96-well plates, using 100 µl cells per well (103 cells/µl; see above). 5–6 hours after induction with PGN, samples on experimental plates were transferred to black 96-well assay plates (BD Falcon) and lysed for 2 minutes in Bright-Glo Assay Reagent (Promega; 100 µl per well). Luciferase activity (relative luciferase units, RLU) of samples was assayed with a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader and SoftMax Pro 4.8. software (Molecular Devices); samples were automixed for 5 seconds and luciferase activity determined using the luminescence read mode (top read, 3 points/well, integration time 1000 milliseconds). For each experiment we used a minimum of 3 replicate wells per treatment; each experiment was repeated at least 4 times. Assays combined with RNAi were analyzed with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) implemented JMP IN 5.1. (SAS Institute; Sall et al., 2004), using RNAi (RNAi vs. control) and hormone (20E vs. 20E plus JHa) as fixed factors.

Northern and Western blotting

For Northern blotting, dsRNA, DNA or dsRNA plus DNA were transfected into S2* cells using a standard calcium phosphate method. dsRNA and DNA were prepared into 2x BBS (BES-buffered saline; 50mM N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)2-aminoethane-sulfonic acid (Sigma), 0.28M NaCl, 1.5mM Na2HPO4, at pH 6.95), followed by addition of CaCl2. Transfection mixtures were vortexed thoroughly and, after 15 minutes of incubation at room temperature, added dropwise to the S2* cells. After 24 hours, transfected cells were split, treated with hormone, and immune stimulated as described above. As controls we used untransfected and mock transfected S2* cells (transfected with the transfection mixture only, without dsRNA or DNA). Total RNA from cultured cells was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and expression of Dpt and control Rp49 (encoding ribosomal protein RP49) was analyzed by RNA blotting as previously described (Silverman et al., 2000). Relative quantification of Dpt expression was performed by comparing intensities of the experimental bands and the Rp49 control bands. For the Northern blot on y, w flies for Dpt mRNA, we followed standard procedures, as previously described (Silverman et al., 2000).

For Western blot analysis of USP, cell lysates from S2* cells transfected with Usp RNAi were prepared and 50 µg of protein per lane was applied on a 10% SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Nonspecific binding was blocked with TBS (25 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 7.5), supplemented with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with a 1:100 dilution of the mouse monoclonal antibody AB11 (courtesy of Carl Thummel) directed against USP (Christianson et al., 1992). After 3 × 15 minutes washes in TBST (TBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100), blots were incubated for 1 hour in peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Amersham) diluted at 1:2500 in TBS and washed three times for 15 minutes with TBST. Proteins were visualized with West Pico SuperSignal (Pierce).

MET protein was examined with Western blotting performed on S2*cells transfected with Met dsRNA, Met plasmid expression vector, or double transfected with Met dsRNA and Met expression vector. Transfection with Met expression vector (pAC5.1(C) MET-V5-6xHis; estimated molecular weight 82.2 kD; courtesy of Thomas G. Wilson) was used because endogenous MET levels in S2* cells were low (data not shown). Transfection was performed using a standard calcium phosphate method; 24 hours after transfection, cells were split, treated with hormones, and immune stimulated as described above. 24 hours later, whole-cell extracts were prepared with lysis buffer and 50 µg of protein extract per lane was applied on a 8% SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane and nonspecific binding was blocked with TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST), supplemented with 10% nonfat dry milk overnight at room temperature. The next day, blots were incubated for 3 hours at room temperature with rabbit polyclonal MET antibody (courtesy of Thomas G. Wilson; Pursley et al., 2000), at a concentration of 1:2500 in 10% milk-TBS, followed by 3 × 15 minutes washes in TBST. Blots were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Bio Rad) diluted at 1:10000 in 10% milk in TBS and washed three times for 15 minutes with TBST. Proteins were visualized with West Pico SuperSignal (Pierce).

Results

JH functions as an immuno-suppressor in vivo

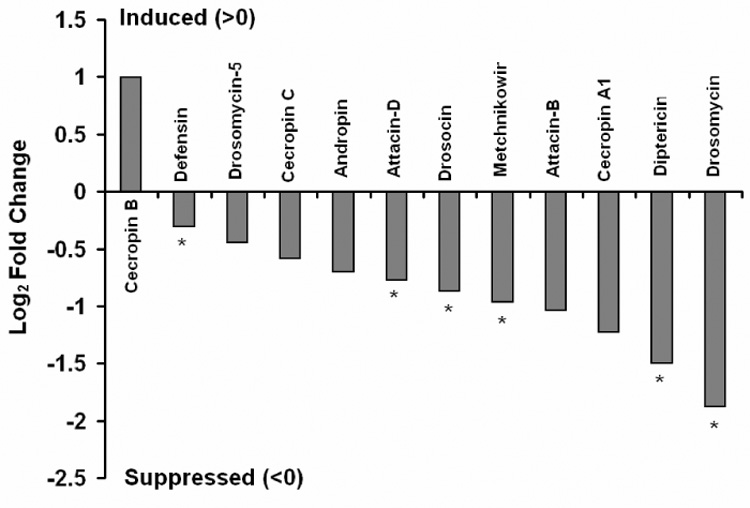

To examine the transcriptional effects of JH in the fly, we performed a microarray experiment using total RNA from whole bodies of uninfected adult D. melanogaster females topically treated with JH III or with solvent (control). FatiGO gene ontology analysis revealed that JH affected the expression of 270 genes by at least two-fold, with 110 genes being upregulated and 160 genes downregulated. Remarkably, among the 270 genes regulated by JH, 35 (13.04%) were annotated as genes involved in response to biotic stimuli such as bacteria, fungi, oxidative stress, and starvation (GO:0009607; Supplementary Table S2). These genes were significantly overrepresented in JH-treated flies relative to chance expectation (observed: 13.04%, expected: 7.55%, Fisher’s Exact Test, P = 0.0051). Within this GO category, genes responsive to pests, pathogens, and parasites (GO:0051707) were significantly enriched (observed: 3.91%, expected: 1.25%, Fisher’s Exact Test, P = 0.004). Among the 160 genes downregulated by JH, 17.65% (28 genes) were genes responsive to biotic stimuli, whereas among the 110 genes upregulated by JH only 6.32% (7 genes) belonged to this category. The difference between these percentages was significant (Fisher’s Exact Test, P = 0.0159), suggesting that the majority of the 35 biotic response genes regulated by JH are suppressed rather than induced by JH. In particular, JH significantly suppressed the basal expression of several antimicrobial peptides by more than two-fold (Table S2). In a separate analysis, relaxing the two-fold change criterion, we found that 6 out of 12 AMP genes, including Diptericin (Dpt) and Drosomycin (Drs), were significantly suppressed by JH III treatment (Fig. 1; t-tests, all P < 0.05). Thus, JH suppresses the transcription of immunity genes in vivo, even in the absence of infection (Fig. 1). To verify these expression data we analyzed two additional, independent microarray experiments, one using y, w females flies, the other S2* cells: in both experiments, JH III or JHa treatment reduced the expression of the majority of AMPs (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

JH III suppresses basal AMP expression in whole flies. Shown are log2-fold change values (JH/control) for 12 AMP transcripts from microarray analyses performed in duplicate. *P<0.05 (t-test). Since the physiological role of JH is not well understood in males, we only used females in this array experiment. We suggest that microarrays might be a particularly useful tool when studying whole organism effects of hormonal signaling: hormones can be topically applied or injected, are taken up into the circulation, act on responsive target tissues, and elicit a systemic, whole organism response (e.g., immune modulation).

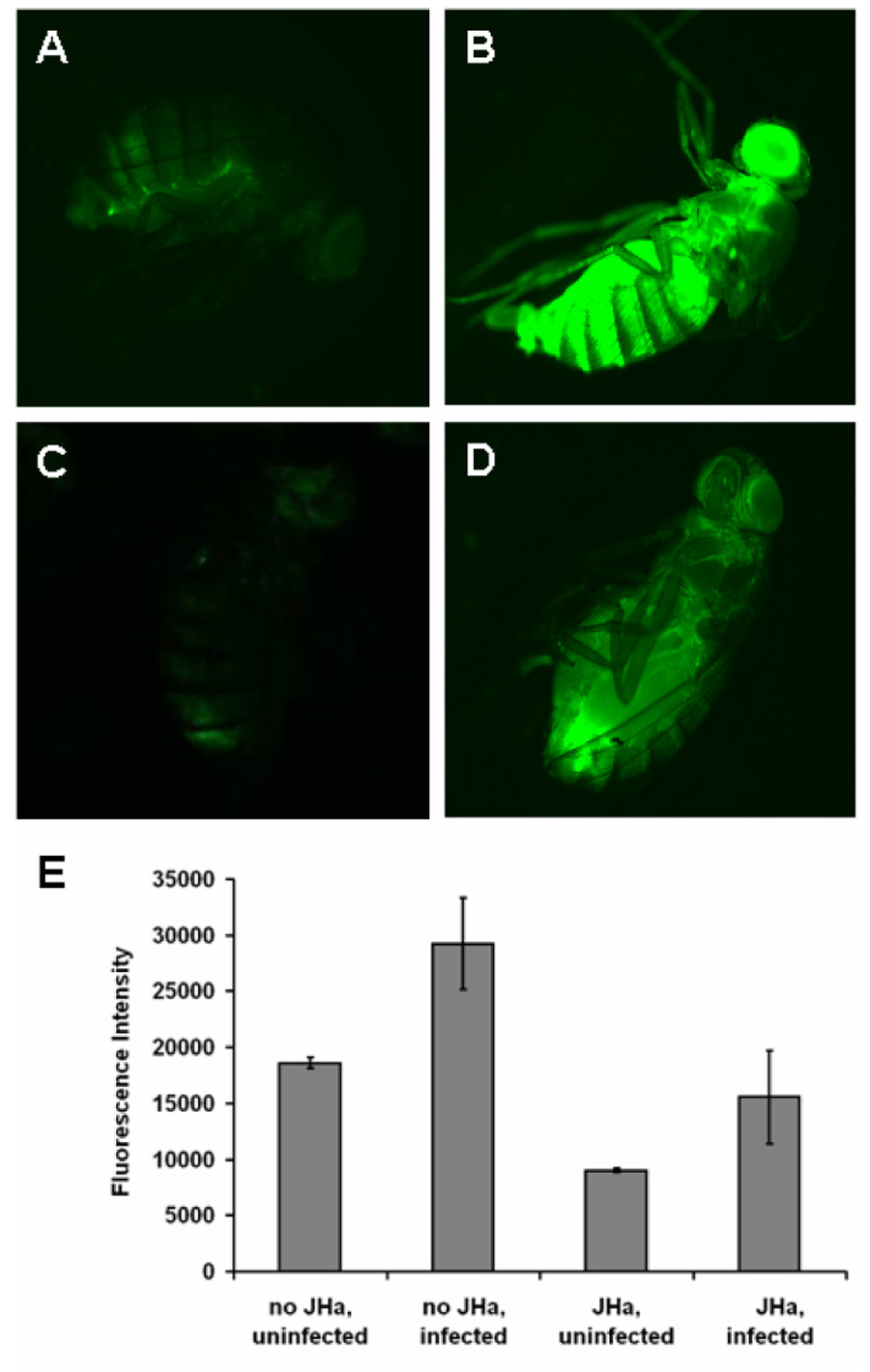

To confirm that JH/JHa suppresses AMP expression in vivo, we analyzed Drosomycin (Drs)- GFP reporter expression in DD1 females (Fig. 2) and Diptericin (Dpt-) GFP reporter expression in DIG females (data not shown). For both reporters, we observed substantial variation among individuals in GFP expression intensity, both within and among treatments, as well as among replicate experiments. Therefore, to test whether JH/JHa treatment suppresses GFP induction upon infection, we estimated Drs-GFP expression using quantitative image analysis. Infection with gram-negative E. coli strongly increased Drs-GFP expression (Figs. 2A, B; two-way ANOVA, F1,7 = 7.09, P = 0.03), while treatment with JHa methoprene significantly reduced expression (Figs. 2A, B; F1,7 = 6.6, P = 0.0375), both in uninfected (Figs. 2A, C, E) and infected flies (Figs. 2B, D, E; infection × hormone interaction effect: F1,7 = 0.008, P = 0.93). Qualitatively similar results were obtained in independent repeats of this experiment and in trials using flies infected with gram-positive M. luteus (data not shown). To further confirm the JH-mediated suppression of AMP induction in vivo we performed Northern blotting on y, w females and found that infection-induced Diptericin (Dpt) expression is reduced ~2-fold in females treated with JHa (methoprene) vapor relative to controls exposed to solvent only (data not shown). Thus, JH/JHa suppresses the expression of genes involved in innate immunity, including several AMPs (Fig. 1, Fig 2, Table S2).

Fig. 2.

JHa methoprene reduces expression of Drosomycin (Drs) in females of the Drs-GFP reporter strain DD1. (A) uninfected (EtOH jabbed), no JHa, (B) infected (E. coli jabbed), no JHa, (C) uninfected (EtOH jabbed), JHa, (D) infected (E. coli jabbed), JHa, (E) quantification of GFP signals from images; shown are means ± 1 standard error; sample size per group, N = 3. Note the strong autofluorescence in the ovaries (C, E). Qualitatively similar results were obtained with a GFP reporter for Diptericin (Dpt-GFP; DIG) and in a Northern blot on Dpt mRNA in y, w females (data not shown), suggesting that JH/JHa acts as a suppressor of AMP induction in vivo.

20E and JH antagonistically regulate AMPs in S2* cells

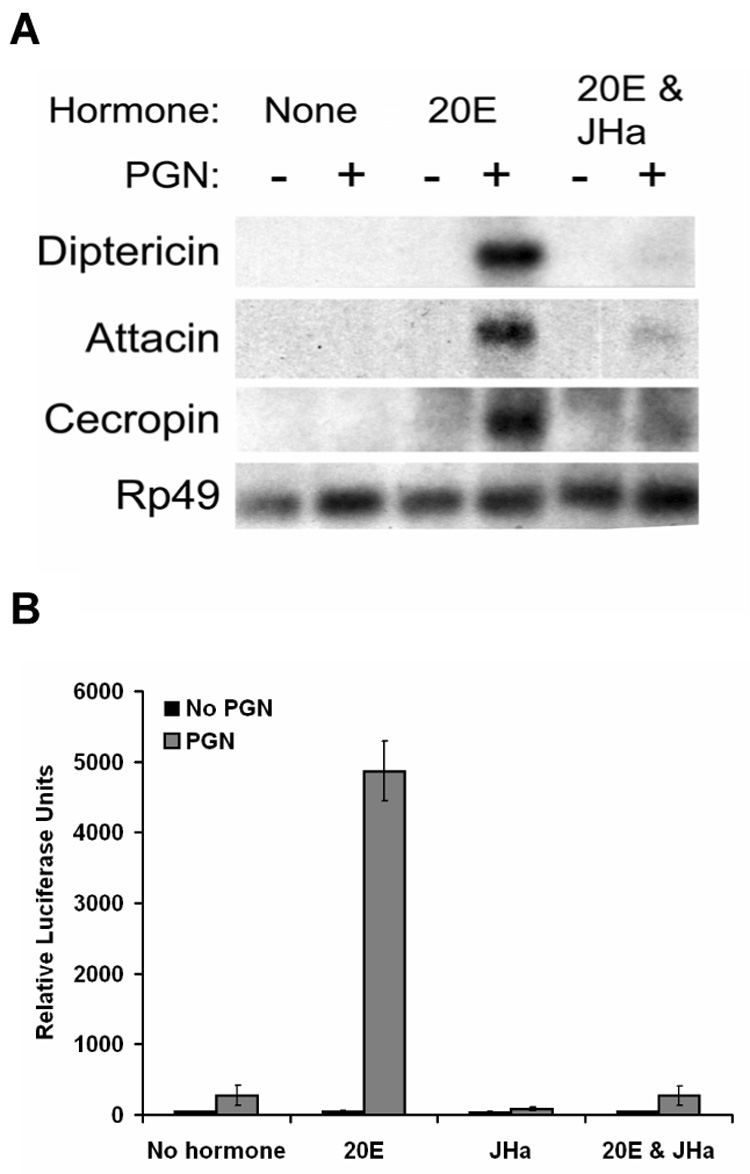

20E promotes AMP expression when whole insects or insect cells in culture are exposed to bacterial stimuli (e.g., Meister and Richards, 1995; Dimarcq et al., 1994, 1997; Silverman et al., 2000). Since JH often counteracts 20E-dependent responses (Riddiford, 1994; Dubrovsky, 2005) and might function as an immuno-suppressor (see above; Flatt et al., 2005), we first verified that pretreatment with 20E is required for efficient AMP transcription upon immune challenge and then examined whether JHa could repress this response. To monitor AMP gene induction, we performed Northern blotting on RNA extracted from S2* cells, using probes for the AMP genes Diptericin (Dpt), Cecropin (Cec), and Attacin (Att) (Fig. 3). S2* cells not exposed to 20E showed little or no AMP gene induction in response to PGN immune stimulation (Fig 3A; left lanes). In contrast, S2* cells pretreated with 20E 24 hours prior to immune challenge robustly and strongly expressed AMPs upon PGN stimulation (Fig 3A, middle lanes). Similarly, treatment of immune stimulated Dpt-luc cells with 20E caused a dramatic increase in Dpt promoter activity (80-fold increase), whereas PGN treatment in absence of 20E had a markedly lesser effect on activation of the Dpt promoter (5-fold increase) (Fig. 3B). Thus, the effects on Dpt mRNA transcript levels, as monitored by Northern blotting (Fig. 3A), are also reflected at the level of Dpt promoter activity, as monitored in luciferase assays.

Fig. 3.

20E and JHa methoprene have antagonistic effects on AMP expression. (A) Northern blot monitoring expression of AMPs Diptericin, Attacin, and Cecropin in S2* cells treated with or without PGN and with different combinations of hormones. (B) Luciferase assay in S2* cells stably transfected with a Dpt-luciferase reporter construct; shown are means ± 1 standard error.

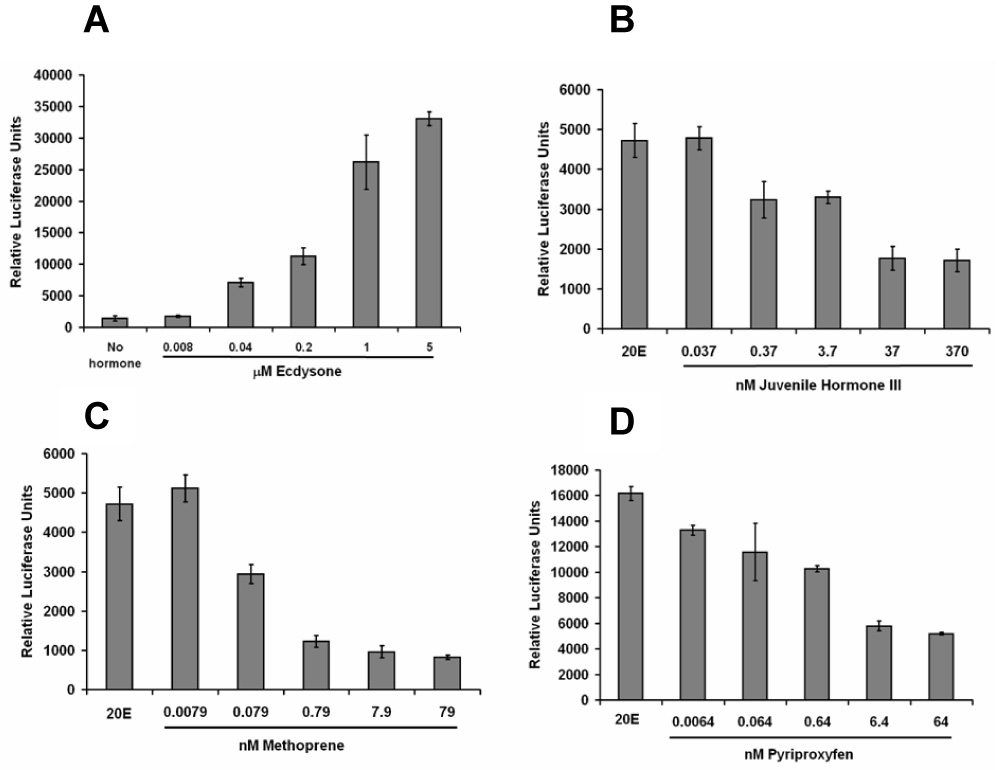

We found that cells treated with both JHa (methoprene) and 20E did not gain the immune capacity of cells treated with 20E alone (Fig. 3A, right lanes; and Fig. 3B, 17-fold decrease as compared to 20E alone), confirming our in vivo observation that JH functions as an immuno-suppressor. JHa in absence of 20E, on the other hand, only weakly suppressed immune capacity of PGN stimulated cells (3.4-fold suppression by JHa as compared to no hormone control) (Fig. 3B). This suggests that JHa is an antagonist of 20E. Dose-response experiments with 20E alone and with JH (or its synthetic analogs methoprene and pyriproxyfen) in presence of 20E confirmed that JH and JHa antagonize the 20E response (Fig. 4). Increasing concentrations of 20E upon immune stimulation strongly increased Dpt reporter activity (Fig. 4A), but JH and its synthetic analogs decreased this response in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 4B, C, D).

Fig. 4.

20E potentiates Dpt induction in a dose-dependent manner (A); JH III (B) and the JHa methoprene (C) and pyriproxyfen (D) suppress the 20-mediated response dose-dependently. Results are from luciferase assays with Dpt-luc cells, immune stimulated with PGN; all JH/JHa treatments were performed in combination with 20E; plotted are means ± 1 standard error.

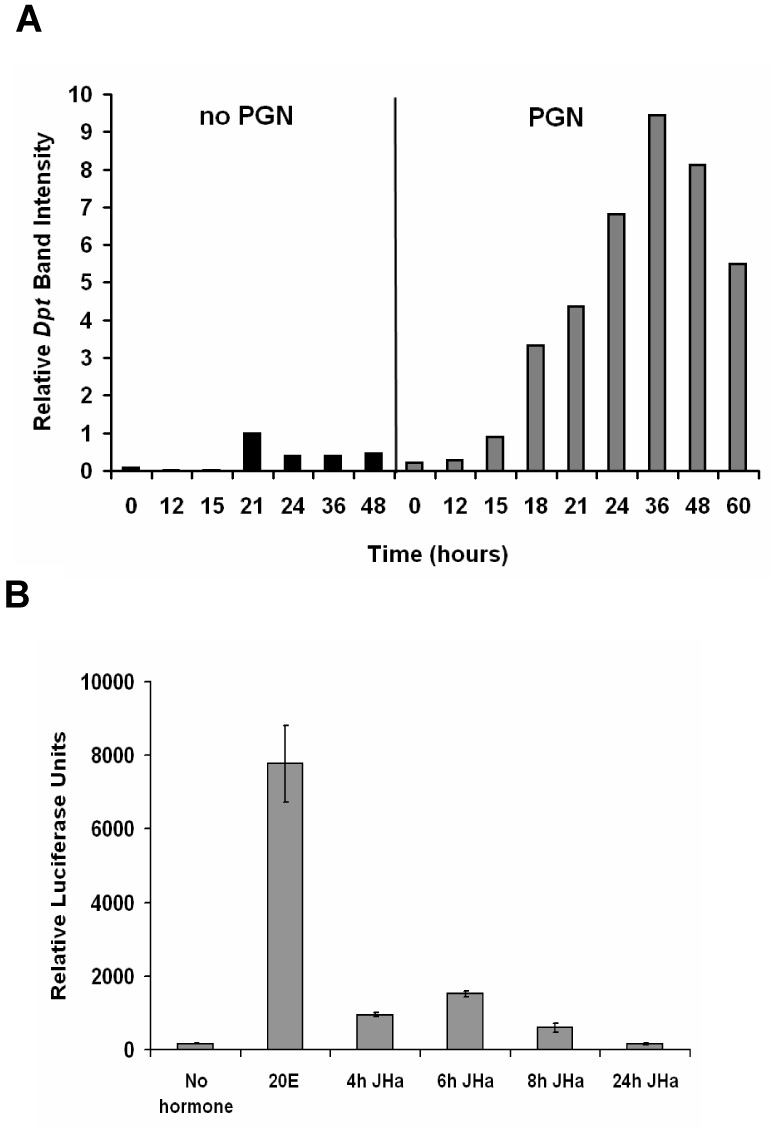

To determine the time course of 20E-mediated potentiation, we assayed Dpt reporter activity in response to a range of 20E incubation times. 20E-mediated potentiation of immune response required at least 18 hours of pretreatment with 20E (Fig. 5A; and data not shown). Similarly, to determine the timing of JHa suppression of 20E-mediated potentiation, Dpt reporter activity was assayed across a range of JHa incubation times. Cells were incubated with 20E for a total of 24 hours; the time at which JHa was added to cell culture varied among treatments. 20E induced Dpt reporter activity was rapidly suppressed by JHa within 4 hours of JHa exposure; exposure of cells to JHa for more than 4 hours did not markedly enhance inhibition of the 20E response (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Dpt potentiation by 20E requires at least 18 hours of hormone exposure in presence of PGN (A), but suppression by JHa methoprene is rapid and does not depend on preincubation (B). Results in (A) are from a Northern blot, with quantification of Dpt expression normalized to that of a Rp49 control (Northern blot not shown). The x-axis displays the period (in hours) during which cells were exposed to 20E; crude PGN contaminated LPS preparations were used to stimulate the immune response. Results in (B) are from a luciferase assay with Dpt-luc cells, immune stimulated with PGN; all JH/JHa treatments were performed in combination with 20E. The x-axis displays the different hormone treatments: no hormone, 20E only (for 24 hours), or 20E (for 24 hrs) in presence of JHa added to cell culture at hours 4, 6, 8, or 24 prior to the luciferase assay. Shown are means ± 1 standard error.

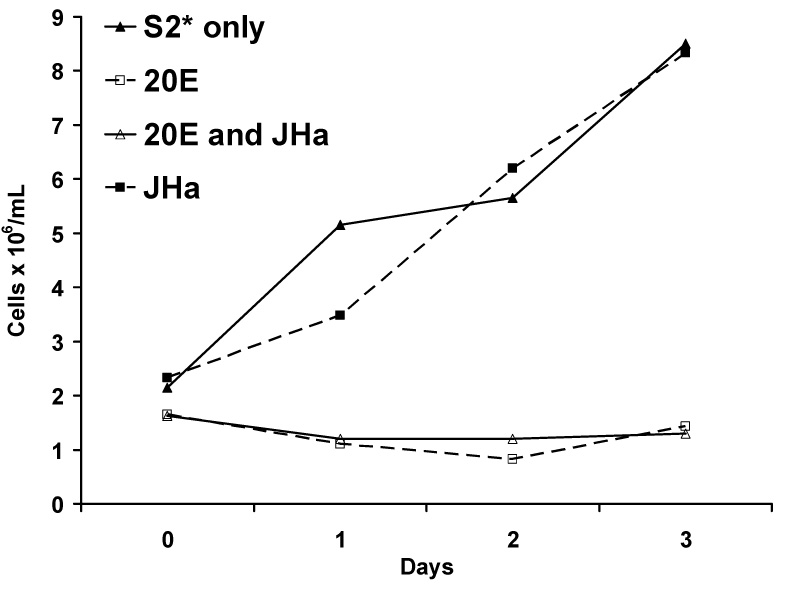

In addition to modulating the immune responsiveness of S2* cells, 20E also induced growth arrest (Fig. 6) and changes in cellular morphology in these cultured cells (data not shown), as previously reported (reviewed in Echalier, 1997). However, the JHa methoprene did not affect these 20E-mediated developmental phenotypes. Cells treated with both 20E and JHa stopped proliferating and morphologically differentiated, just as cells treated with 20E alone (Fig. 6 and data not shown). Thus, JHa appears to be a rapid and specific inhibitor of the ability of 20E to increase immune capacity.

Fig. 6.

20E blocks S2* cell proliferation, but proliferation is unaffected by JHa methoprene; JHa treatment does not prevent the 20E-mediated block in cell proliferation. Cells were left untreated (filled triangles), exposed to 20E (squares), JHa (filled squares), or both hormones (triangles); cell counts were monitored every 24 hours over the next three days. Shown are cell counts (in units of 106 cells/ml cell culture media) over time. The result shown is representative of 3 independent experiments (data not shown).

20E induction of AMPs requires EcR/USP

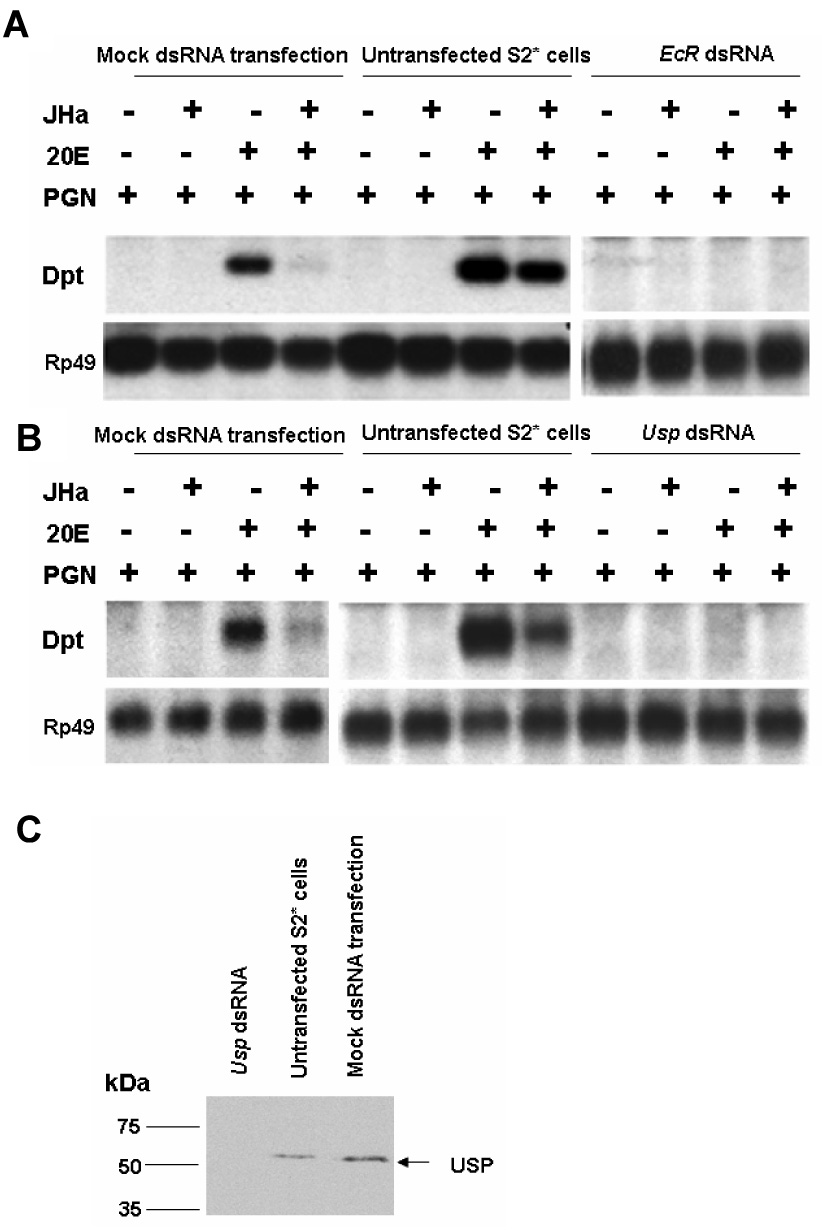

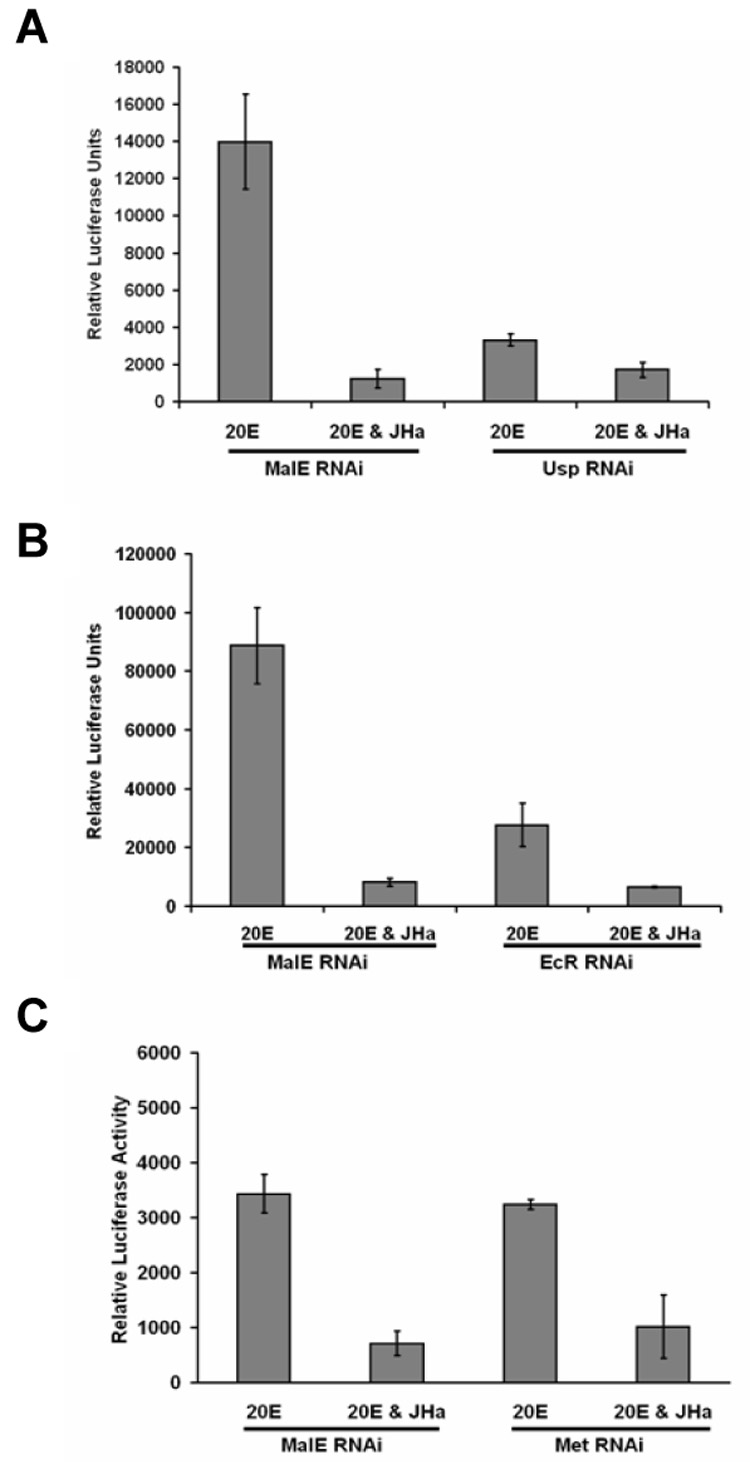

20E signaling typically requires binding of the hormone to a heterodimer formed by two nuclear hormone receptor family members, ecdysone receptor (EcR) and ultraspiracle (USP) (Koelle et al., 1991; Thomas et al., 1992; Yao et al., 1993; Hall and Thummel, 1998). We therefore tested whether 20E potentiation of Dpt requires EcR and Usp (Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Supplementary Table S3). RNAi directed against EcR completely prevented 20E-mediated potentiation of Dpt mRNA expression and reporter activity (Fig. 7A, Fig. 8A, Table S3). Similarly, RNAi directed against Usp abolished 20E potentiation (Fig. 7B, Fig. 8B, Table S3); Western blot analysis confirmed effectiveness of Usp RNAi (Fig. 7C). Although 20E-mediated potentiation of Dpt reporter activity was markedly decreased by RNAi targeting of EcR and Usp, the residual level of reporter activity was still inhibited by JHa (Figs. 8A, B), but this suppression was not statistically significant (Table S3; interaction contrasts analysis). Thus, it is difficult to firmly conclude whether or not USP is required for the JHa-mediated suppression of immune inducibility. Similar results were obtained when using JH III (data not shown). However, it is very clear that 20E regulates Dpt expression and promoter activity by signaling through EcR/USP.

Fig. 7.

(A–B) Northern blotting for Dpt induction shows that EcR and Usp are both required for the potentiation of Dpt induction by 20E, as determined by RNAi-mediated silencing using dsRNA. (C) Western blot with mouse monoclonal antibody AB11 against USP; the Western blot was performed on the same samples used in the Northern blot; RNAi successfully silenced Usp.

Fig. 8.

Dpt promoter activity with RNAi-mediated silencing (dsRNA) directed against EcR (A), Usp (B), and Met (C). Silencing EcR and Usp abolishes the 20E response; JHa methoprene seems to suppress the weak Dpt induction that occurs in EcR or Usp knock-down cells; however, this effect is not significant (Table S3). In contrast, silencing Met does not impair the 20E response, and JHa is fully effective in suppressing immune induction by 20E. Results are from luciferase assays with Dpt-luc cells, immune stimulated with PGN; all JH/JHa treatments were performed in combination with 20E; plotted are means ± 1 standard error.

JH repression of AMPs is independent of MET

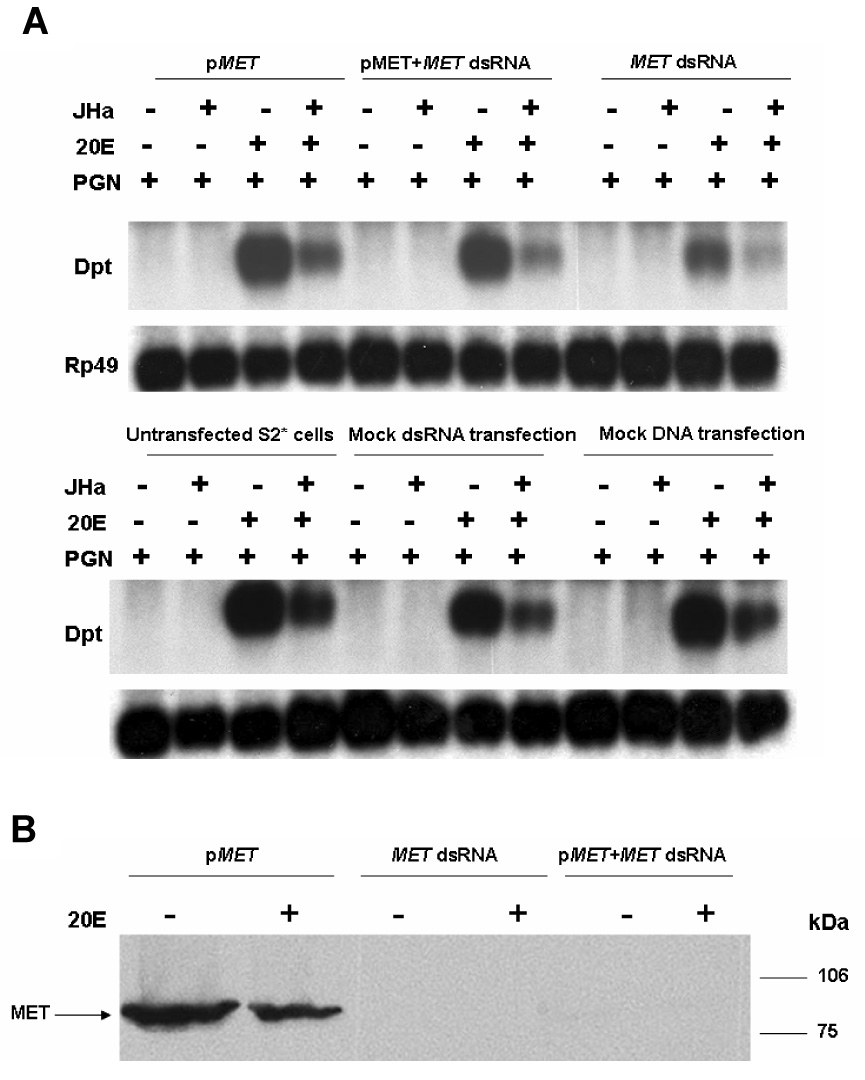

In contrast to 20E, the mechanisms underlying signal transduction downstream of JH remain unknown (Wilson, 2004; Berger and Dubrovsky, 2005; Dubrovsky, 2005; Flatt et al., 2005). Therefore, to understand how JH down-modulates immune function, we asked whether repression of the 20E response by JH and JHa depends on methoprene-tolerant (Met), a candidate receptor for JH (Wilson and Fabian, 1986; Shemshedini and Wilson, 1990; Shemshedini et al., 1990; Wilson and Ashok, 1998; Pursley et al., 2000). RNAi-mediated silencing of Met did not affect 20E potentiation of Dpt promoter activity and mRNA expression (Fig. 8C, Fig.9A, Table S3), suggesting that Met is not involved in 20E signaling. To confirm the effectiveness of Met RNAi, we performed Western blot analysis with rabbit polyclonal antibody against MET. Since endogenous MET levels were low (data not shown), we overexpressed Met with a plasmid expression vector (pMET) and found that RNAi successfully silenced Met (Fig. 9B). Remarkably, when directing RNAi against Met, the JHa methoprene was still able to fully suppress Dpt activity, suggesting that Met does not function in the JH modulation of immunity in Drosophila (Fig. 8C, Fig. 9A, Table S3); experiments using JH III yielded similar results (data not shown).

Fig. 9.

(A) Northern blotting for Dpt shows that Met is not required for induction of Dpt expression by 20E; notably, JHa methoprene in presence of 20E is able to fully suppress Dpt expression even when Met function is silenced; pMET refers to cells transfected with Met expression vector plasmid. (B) Western blot with rabbit polyclonal antibody against MET; the Western blot was performed on the same samples used in the Northern blot; RNAi successfully silenced Met.

Discussion

In insects, 20E and JH coordinate many aspects of growth, development, reproduction, behavior, and lifespan (Nijhout, 1994; Riddiford, 1994; Kozlova and Thummel, 2000; Dubrovsky, 2004; Berger and Dubrovsky, 2005; Flatt et al., 2005, 2006; Tu et al., 2006). Previous evidence indicates that both hormones can individually modulate immunity (Meister and Richards, 1995; Dimarcq et al., 1997; Rolff and Siva-Jothy, 2002; Beckstead et al., 2005). Here, using experiments in Drosophila S2* cells and whole flies, we have shown that 20E and JH exert antagonistic effects on mRNA expression and promoter activity of AMP genes. This is similar to 20E and JH action during midgut remodeling where the JHa methoprene suppresses the expression of genes involved in 20E signaling and 20E-mediated programmed cell death (Parthasarathy and Palli, 2007; Parthasarathy et al., 2008a).

We found that 20E potentiates expression of several AMPs, as previously observed (Meister and Richards, 1995; Dimarcq et al., 1994, 1997; Silverman et al., 2000). We extend previous findings by showing that 20E is a specific hormonal potentiator of AMP induction: upon immune stimulation, 20E enables, in a dose- and time-dependent manner, Dpt induction following immune stimulation. Interestingly, immune potentiation by 20E required at least 18 hours of hormone exposure. 20E is known to transcriptionally regulate target genes through enhancers that contain ecdysone receptor (EcR) response elements (EcREs). Since this level of transcriptional activation occurs rapidly and since many EcR targets are transcription factors (Thummel, 2002; Yin and Thummel, 2005), it seems likely that 20E mediates the increase in immune responsiveness through secondary or tertiary targets of 20E/EcR signaling.

Although JH has been previously implied in modulating immunity (Manetti et al., 1997; Hiruma and Riddiford, 1998; Rolff and Siva-Jothy, 2002; Rantala et al., 2003), JH effects on AMP expression have not been investigated. We found that potentiation of Dpt activity by 20E was strongly suppressed by compounds with JH activity (juvenoids). Inhibitory effects were not only obtained by using the JHa methoprene and pyriproxyfen, but, importantly, also by the natural hormone JH III (methyl epoxy farnesoate). In addition, another product of the larval ring gland and adult corpus allatum (tissues producing JH), the JH precursor methyl farnesoate (MF; Jones et al. 2006; Jones and Jones, 2007), also strongly suppresses 20E induction of Dpt activity (unpublished data). While we consistently observed robust JH- or JHa-mediated suppression of AMP induction in S2* cells, quantitative levels of suppression were quite variable among experiments, presumably due to slight variations in the physiological state of the cells or in luciferase assay conditions. Our dose-response experiments with JH III, MF, and JHa suggest that these inhibitory effects are specific hormonal effects; all compounds caused strong suppression of the 20E response at concentrations below 10−10 M. The specificity of these effects is further suggested by our observation that JHa did not block S2* cells from attaining 20E-induced growth arrest and morphological differentiation (also see Wyss, 1976; Cherbas et al., 1989; Echalier, 1997). In contrast to induction by 20E, immune suppression by juvenoids was rapid and did not require preincubation, suggesting that the repression is the result of a primary hormone response. Moreover, inhibitory effects of juvenoids seen in S2* cells were faithfully mirrored in the fly: in microarrays, GFP reporter assays, and Northern blot experiments performed on adult flies, JH/JHa acted as powerful immuno-suppressors of AMP expression in vivo. Both JH and 20E act on many target tissues in the fly, including brain, gonads, and fat body, the equivalent of the mammalian liver and a major endocrine target tissue (Nijhout, 1994; Riddiford, 1994; Flatt et al., 2005). Since upon systemic infection AMPs are mainly produced in the fat body, it is likely that JH/20E modulation of AMP induction normally takes place in this tissue. Together, our findings suggest that 20E and JH interact antagonistically to regulate immunity in Drosophila.

To understand the mode of JH/20E signaling action in immunity we used RNA interference in S2* cells. We focused on three key genes involved in 20E and JH signaling: ecdysone receptor (EcR), ultraspiracle (Usp), and methoprene-tolerant (Met). 20E signaling requires 20E binding to a heterodimer between EcR and USP (Koelle et al., 1991; Thomas et al., 1992; Yao et al., 1993; Hall and Thummel, 1998). However, 20E signals can also be mediated by EcR homodimers (in vitro, cf. Lezzi et al., 1999, 2002; Grebe et al., 2003), heterodimers between hormone-receptor 38 (DHR38) and USP (Baker et al., 2003), or non-genomic actions (Wehling et al., 1997; Elmogy et al., 2004; Srivastava et al., 2005). Confirming the classical model of 20E signal transduction, we found that 20E potentiation of Dpt induction requires both EcR and USP function. When EcR and Usp were silenced with RNAi, JHa still appeared to be able to suppress the residual Dpt induction (cf. Figs. 8A, B), however, this effect was not statistically significant (Table S3). Thus, it is possible that the EcR/USP heterodimer is not involved in the JH-mediated immune suppression. On the other hand, we cannot exclude the possibility that EcR/USP integrate both 20E and JH signaling (Fang et al., 2005); under such a model, the EcR/USP heterodimer would be required for both Dpt activation by 20E and its suppression by JH/JHa.

Indeed, the USP part of EcR/USP might be an important mediator of JH signaling since JH can act as a USP ligand and suppress or potentiate 20E-dependent EcR signaling responses (Jones and Sharp, 1997; Jones et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2002; Henrich et al., 2003; Maki et al., 2004; Wozniak et al., 2004; Fang et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2006). For example, JH and 20E can synergistically activate a JH esterase reporter gene (Fang et al., 2005). While both hormones can activate transcription independently, activation is greater than additive if both hormones are present. In absence of 20E, activation by JH is through the USP homodimer, whereas activation by 20E in absence of JH is mediated by EcR/USP (Fang et al., 2005). Notably, when both hormones are present, EcR/USP mediates integration of JH and 20E signaling, with JH signaling being mediated by the USP part of the 20E-liganded heterodimer (Fang et al., 2005). Thus, our results suggest that EcR/USP is required for 20E signaling in Drosophila immunity, but we cannot rule out the interesting possibility that JH exerts its inhibitory effects by signaling through the USP part of EcR/USP. Future work will be needed to test the requirement of EcR/USP for fat body-specific induction of AMPs in vivo, using dominant negative (DN) or RNAi constructs.

Another candidate for the elusive JH receptor is encoded by methoprene-tolerant (Met), a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)-Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) transcription factor (Wilson and Fabian, 1986; Shemshedini and Wilson, 1990; Shemshedini et al. 1990; Wilson and Ashok, 1998; Pursley et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 2003). While MET is not a nuclear hormone receptor like EcR or USP, MET binds JH with higher affinity than USP and functions as a JH-dependent transcription factor (Miura et al., 2005). Moreover, Met genetically interacts with the 20E-regulated transcription factor Broad-Complex (BR-C) (Wilson et al., 2006), an important mediator of 20E signaling downstream of EcR, and MET protein interacts with both EcR and USP in GST pull-down assays (Li et al., 2007). However, while Met controls entry into metamorphosis in the beetle Tribolium castaneum, as one would expect if Met encodes a JH receptor (Konopova and Jindra, 2007), Drosophila Met null mutants show normal development (Wilson and Fabian, 1986; Wilson and Ashok, 1998; Flatt and Kawecki, 2004).

To further examine the role of MET in JH signal transduction we directed RNAi against Met in Dpt-luc S2* cells and found that silencing Met does not impair 20E induction of Dpt. Remarkably, we also found that RNAi against Met does not abolish the immuno-suppressive action of JH/JHa, despite the involvement of MET in certain JH responses (Miura et al. 2005; Konopova and Jindra, 2007). Similarly, despite its involvement in JH signaling, MET does not seem to be required for JH suppression of 20E action in Tribolium (Parthasarathy and Palli 2008; Parthasarathy et al., 2008b). We conclude that MET does not function in the JH regulation of immunity in Drosophila. Thus, it appears that JH suppression of 20E action may be mediated by USP (as part of the ECR/USP heterodimer or as monomer/homodimer) or by another, yet unidentified mechanism. While the identity of the JH receptor remains unresolved, the endocrine regulation of Drosophila immunity might provide a powerful model system for studying regulatory crosstalk between JH/20E and for dissecting the elusive JH signaling pathway. Moreover, given the common endocrine-based trade-off between reproduction and immunity in mammals, birds, and invertebrates (Muehlenbein and Bribiescas, 2005; Harshman and Zera, 2007; Lawniczak et al., 2007; Miyata et al., 2008), it will be of major interest to study how the reproductive insect hormones JH and 20E interact to co-regulate reproduction and immune function (Flatt et al., 2005).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Johannes Bauer, Alan Bergland, Boris Gershman, Jakub Godlewski, Damudar Kethidi, Sarah Morris, Lynn Riddiford, Carl Thummel, and Thomas G. Wilson for helpful advice and discussion; Kamna Aggarwal, Jim Cypser, Deniz Erturk Hasdemir, Nicholas Paquette, Diana Wentworth for help in the laboratory; Carl Thummel for USP antibody; Thomas G. Wilson for MET antibody and expression vector; Eric Rulifson for the y, w strain, Dominique Ferrandon for the DD1 strain, and Bruno Lemaitre for the DIG strain; Lynn Riddifrod, Grace Jones and Davy Jones for MF; and Jason Hodin and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. Supported by postdoctoral fellowships from Swiss National Science Foundation and Roche Research Foundation to T.F.; grants from NIH (R01 AG024360 and R01 AG021953) and a Senior Scholar Award from Ellison Medical Foundation to M.T.; a NIH grant (AI060025) to N.S.; and a NSF grant (IBN-0421856) to S.R.P.

List of abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AMPs

antimicrobial peptides

- camp

cathelicidin

- DD1

Drosomycin-GFP strain

- defB2

defensin β2

- Dif

Dorsal-related immunity factor

- Dpt

Diptericin

- Drs

Drosomycin

- 20E

20-hydroxy-ecdysone

- EcR

ecydsone receptor

- EcREs

EcR response elements

- Ers

estogren receptors

- GNBPs

gram-negative binding proteins

- GO

gene ontology

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- IMD

immune deficiency pathway

- JH

juvenile hormone

- JHa

juvenile hormone analog

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LXRs

liver X receptors

- Met

methoprene-tolerant

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- NR

nuclear hormone receptor

- PGN

peptidoglycan

- PGRPs

peptidoglycan recognition proteins

- PPARs

peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors

- PRRs

pattern recognition receptors

- RNAi

RNA interference

- S2* cells

Scheider S2* cells

- Usp

ultraspiracle

- VDRs

vitamin D receptors

References

- Ahmed A, Martin D, Manetti AGO, Han SJ, Lee WJ, Mathiopoulos KD, Muller HM, Kafatos FC, Raikhel A, Brey PT. Genomic structure and ecdysone regulation of the prophenoloxidase 1 gene in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:14795–14800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahrour F, Diaz-Uriarte R, Dopazo J. FatiGO: a web tool for finding significant associations of Gene Ontology terms with groups of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:578–580. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amdam GV, Simoes ZLP, Hagen A, Norberg K, Schroder K, Mikkelsen O, Kirkwood TBL, Omholt SW. Hormonal control of the yolk precursor vitellogenin regulates immune function and longevity in honeybees. Exp. Geront. 2004;39:767–773. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KD, Shewchuk LM, Kozlova T, Makishima M, Hassell A, Wisely B, Caravella JA, Lambert MH, Reinking JL, Krause H. The Drosophila orphan nuclear receptor DHR38 mediates an atypical ecdysteroid signaling pathway. Cell. 2003;113:731–742. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beagley KW, Gockel CM. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by the female sex hormones oestradiol and progesterone. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2003;38:13–22. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead RB, Lam G, Thummel CS. The genomic response to 20-hydroxyecdysone at the onset of Drosophila metamorphosis. Genome Biol. 2005;6:R99. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-12-r99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger EM, Dubrovsky EB. Juvenile hormone molecular actions and interactions during development of Drosophila melanogaster. Vitam. Horm., 2005;73:75–215. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(05)73006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherbas L, Koehler MMD, Cherbas P. Effects of juvenile hormone on the ecdysone response of Drosophila Kc cells. Dev. Genet. 1989;10:177–188. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernysh SI, Simonenko NP, Braun A, Meister M. Developmental variability of the antibacterial response in larvae and pupae of Calliphora vicina (Diptera, Calliphoridae) and Drosophila melanogaster (Diptera, Drosophilidae) Europ. J. Entom. 1995;92:203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Chow EK-H, Razani B, Cheng G. Innate immune system regulation of nuclear hormone receptors in metabolic diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007;82:187–195. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson AMK, King DL, Hatzivassiliou E, Casas JE, Hallenbeck PL, Nikodem VM, Mitsialis SA, Kafatos FC. DNA binding and heteromerization of the Drosophila transcription factor chorion factor 1/Ultraspiracle. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:11503–11507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimarcq JL, Hoffmann D, Meister M, Bulet P, Lanot R, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. Characterization and transcriptional profiles of a Drosophila gene encoding an insect defensin. A study in insect immunity. Europ. J. Biochem. 1994;221:201–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimarcq J-L, Imler J-L, Lanot R, Ezekowitz RAB, Hoffmann JA, Janeway CA, Lagueux M. Treatment of l(2)mbn Drosophila tumorous blood cells with the steroid hormone ecdysone amplifies the inducibility of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol. 1997;27:877–886. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrovsky EB. Hormonal cross talk in insect development. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;16:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echalier G. Experimental models of gene regulation: 2. Cell responses to hormone. In: Echalier G, editor. Drosophila Cells in Culture. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 393–438. [Google Scholar]

- Elmogy M, Iwami M, Sakurai S. Presence of membrane ecdysone receptor in the anterior silk gland of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:3171–3179. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engström Y. Induction and regulation of antimicrobial peptides in Drosophila. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 1999;23:345–358. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(99)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang F, Xu Y, Jones D, Jones G. Interactions of ultraspiracle with ecdysone receptor in the transduction of ecdysone- and juvenile hormone-signaling. FEBS Journal. 2005;272:1577–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandon D, Jung AC, Criqui M, Lemaitre B, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Michaut L, Reichhart J, Hoffmann JA. A drosomycin-GFP reporter transgene reveals a local immune response in Drosophila that is not dependent on the Toll pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:1217–1227. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatt T, Kawecki TJ. Pleiotropic effects of methoprene-tolerant (Met), a gene involved in juvenile hormone metabolism, on life history traits in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetica. 2004;122:141–160. doi: 10.1023/b:gene.0000041000.22998.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatt T, Kawecki TJ. Juvenile hormone as a regulator of the trade-off between reproduction and life span in Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution. 2007;61:1980–1991. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatt T, Tu MP, Tatar M. Hormonal pleiotropy and the juvenile hormone regulation of Drosophila development and life history. BioEssays. 2005;27:999–1010. doi: 10.1002/bies.20290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatt T, Moroz LL, Tatar M, Heyland A. Comparing thyroid and insect hormone signaling. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2006;46:777–794. doi: 10.1093/icb/icl034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franssens V, Smagghe G, Simonet G, Claeys I, Breugelmans B, De Loof A, Vanden Broeck J. 20-hydroxyecdysone and juvenile hormone regulate the laminarin-induced nodulation reaction in larvae of the flesh fly, Neobellieria bullata. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2006;30:735–740. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershman B, Puig O, Hang L, Peitzsch RM, Tatar M, Garofalo RS. High-resolution dynamics of the transcriptional response to nutrition in Drosophila: a key role for dFOXO. Physiol. Genom. 2007;29:24–34. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00061.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JP, Kanost MR, Trenczek T. Biological mediators of insect immunity. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 1997;42:611–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.42.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebe M, Przibilla S, Henrich VC, Spindler-Barth M. Characterization of the ligand binding domain of the ecdysteroid receptor from Drosophila melanogaster. Biol. Chem. 2003;384:105–116. doi: 10.1515/BC.2003.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BL, Thummel CS. The RXR homolog ultraspiracle is an essential component of the Drosophila ecdysone receptor. Development. 1998;125:4709–4717. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harshman LG, Zera AJ. The cost of reproduction: the devil in the details. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich VC, Burns E, Yelverton DP, Christensen E, Weinberger C. Juvenile hormone potentiates ecdysone receptor-dependent transcription in a mammalian cell culture system. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;33:1239–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiruma K, Riddiford LM. Granular phenoloxidase involved in cuticular melanization in the tobacco hornworm: regulation of its synthesis in the epidermis by juvenile hormone. Dev. Biol. 1988;130:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JA. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature. 2003;426:33–38. doi: 10.1038/nature02021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JA, Reichhart JM. Drosophila innate immunity: an evolutionary perspective. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:121–126. doi: 10.1038/ni0202-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway CA., Jr. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1989;54:1–13. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D, Jones G. Farnesoid secretions of dipteran ring glands: What we do know and what we can know. Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol. 2007;37:771–798. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Sharp PA. Ultraspiracle: An invertebrate nuclear receptor for juvenile hormones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13499–13503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Wozniak M, Chu Y, Dhar S, Jones D. Juvenile hormone III-dependent conformational changes of the nuclear receptor ultraspiracle. Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol. 2001;32:33–49. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Jones D, Teal P, Sapa A, Wozniak M. The retinoid-X receptor ortholog, ultraspiracle, binds with nanomolar affinity to an endogenous morphogenetic ligand. FEBS J. 2006;273:4983–4996. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph SB, Castrillo A, Laffitte BA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P. Reciprocal regulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism by liver X receptors. Nature Med. 2003;9:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nm820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Silverman N. Bacterial recognition and signalling by the Drosophila IMD pathway. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:461–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Goldman WE, Mellroth P, Steiner H, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Harley W, Fox A, Golenbock D, Silverman N. Monomeric and polymeric gram-negative peptidoglycan but not purified LPS stimulate the Drosophila IMD pathway. Immunity. 2004;20:637–649. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00104-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrell DA, Beutler B. The evolution and genetics of innate immunity. Nature Rev. Genet. 2001;2:256–267. doi: 10.1038/35066006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelle MR, Talbot WS, Segraves WA, Bender MT, Cherbas P, Hogness DS. The Drosophila EcR gene encodes an ecdysone receptor, a new member of the steroid receptor family. Cell. 1991;67:59–77. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90572-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopova B, Jindra M. Juvenile hormone resistance gene methoprene-tolerant controls entry into metamorphosis in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:10488–10493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703719104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlova T, Thummel CS. Steroid regulation of postembryonic development and reproduction in Drosophila. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2000;11:276–280. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00282-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanot R, Zachary D, Holder F, Meister M. Postembryonic hematopoiesis in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2001;230:243–257. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawniczak MK, Barnes AI, Linklater JR, Boone JM, Wigby S, Chapman T. Mating and immunity in invertebrates. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007;22:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer RI, Ganz T. Antimicrobial peptides in mammalian and insect host defence. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1999;11:23–27. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezzi M, Bergman T, Mouillet JF, Henrich VC. The ecdysone receptor puzzle. Arch. Insect. Biochem. Physiol. 1999;41:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lezzi M, Bergman T, Henrich VC, Vögtli M, Frömel C, Grebe M, Przibilla S, Spindler-Barth M. Ligand-induced heterodimerization between the ligand binding domains of the Drosophila ecdysteroid receptor and ultraspiracle. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:3237–3245. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang Z, Robinson GE, Palli SR. Identification and Characterization of a Juvenile Hormone Response Element and Its Binding Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:37605–37617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704595200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki A, Sawatsubashi S, Ito S, Shirode Y, Suzuki E, Zhao Y, Yamagata K, Kouzmenko A, Takeyama K-I, Kato S. Juvenile hormones antagonize ecdysone actions through co-repressor recruitment to EcR/USP heterodimers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2004;320:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manetti AGO, Rosetto M, de Filippis T, Marchini DT, Baldari C, Dallai R. Juvenile hormone regulates the expression of the gene encoding ceratotoxin A, an antibacterial peptide from the female reproductive accessory glands of the medfly Ceratitis capitata. J. Insect Physiol. 1997;43:1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(97)00052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R, Janeway CA. An ancient system of host defense. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1998;10:12–15. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister M, Richards G. Ecdysone and insect immunity: the maturation of the inducibility of the diptericin gene in Drosophila larvae. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1996;26:155–160. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(95)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Oda M, Makita S, Chinzei Y. Characterization of the Drosophila Methoprene-tolerant gene product. Juvenile hormone binding and ligand-dependent gene egulation. FEBS J. 2005;272:1169–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata S, Begun J, Troemel ER, Ausubel FM. DAF-16-Dependent Suppression of Immunity During Reproduction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2008;178:903–918. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.083923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenbein MP, Bribiescas RG. Testosterone-Mediated Immune Functions and Male Life Histories. Am. J. Human Biol. 2005;17:527–558. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller H-M, Dimopoulos G, Blass C, Kafatos FC. A hemocyte-like cell line established from the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae expresses six prophenoloxidase genes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:11727–11735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhout HF. Insect hormones. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Lozach J, Benner C, Pascual G, Tangirala RK, Westin S, Hoffmann A, Subramaniam S, David M, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK. Molecular determinants of crosstalk between nuclear receptors and Toll-like receptors. Cell. 2005;122:707–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy R, Palli SR. Developmental and hormonal regulation of midgut remodeling in a lepidopteran insect, Heliothis virescens. Mech. Dev. 2007;124:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy R, Palli SR. Proliferation and differentiation of intestinal stem cells during metamorphosis of the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Dev. Dyn. 2008;237:893–908. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy R, Tan A, Bai H, Palli SR. Transcription factor broad suppresses precocious development of adult structures during larval-pupal metamorphosis in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Mech. Dev. 2008a;125:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy R, Tan A, Palli SR. bHLH-PAS family transcription factor methoprene-tolerant plays a key role in JH action in preventing the premature development of adult structures during larval-pupal metamorphosis. Mech. Develop. 2008b doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.03.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual G, Glass CK. Nuclear receptors versus inflammation: mechanisms of transrepression. Trends Endocrinol. Metabol. 2006;17:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pursley S, Ashok M, Wilson TG. Intracellular localization and tissue specificity of the Methoprene-tolerant (Met) gene product in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol. 2000;30:839. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(00)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantala MJ, Vainikka A, Kortet R. The role of juvenile hormone in immune function and pheromone production trade-offs: a test of the immunocompetence handicap principle. Proc. Roy. Soc. London B. 2003;270:2257–2261. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichhart JM, Meister M, Dimarcq JL, Zachary D, Hoffmann D, Ruiz C, Richards G, Hoffmann JA. Insect immunity: developmental and inducible activity of the Drosophila diptericin promoter. EMBO J. 1992;11:1469–1477. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricote M, Li AC, Willson TM, Kelly CJ, Glass CK. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391:79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddiford LM. Cellular and molecular actions of juvenile hormone. I. General considerations and premetamorphic actions. Advanc. Insect Physiol. 1994;24:213–274. [Google Scholar]

- Riddiford LM, Ashburner M. Effects of juvenile hormone mimics on larval development and metamorphosis of Drosophila melanogaster. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1991;82:172–183. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(91)90181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolff J, Siva-Jothy MT. Copulation corrupts immunity: a mechanism for a cost of mating in insects. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:9916–9918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152271999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins-Smith LA. Metamorphosis and the amphibian immune system. Immunol. Rev. 1998;166:221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollins-Smith LA, Davis AT, Blair PJ. Effects of thyroid hormone deprivation on immunity in postmetamorphic frogs. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 1993;17:157–164. doi: 10.1016/0145-305x(93)90025-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxström-Lindquist K, Assefaw-Redda Y, Rosinska K, Faye I. 20-hydroxyecdysone indirectly regulates Hemolin gene expression in Hyalophora cecropia. Insect Mol. Biol. 2005;14:645–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2005.00593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sall J, Creighton L, Lehman A. JMP start statistics. 3rd ed. Cary, NC: Thomson Learning, SAS Institute; Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Samakovlis C, Åsling B, Boman HG, Gateff E, Hultmark D. In vitro induction of cecropin genes - an immune response in a Drosophila blood cell line. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;188:1169–1175. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91354-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab M, Reynders V, Shastri Y, Loitsch S, Stein J, Schroder O. Role of nuclear hormone receptors in butyrate-mediated up-regulation of the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin in epithelial colorectal cells. Molec. Immunol. 2007;44:2107–2114. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemshedini L, Wilson TG. Resistance to juvenile hormone and insect growth regulator in Drosophila is associated with altered cytosolic juvenile hormone-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:2072–2076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemshedini L, Lanoue M, Wilson TG. Evidence for a juvenile hormone receptor involved in protein synthesis in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:1913–1918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman N, Maniatis T. NF-kappa B signaling pathways in mammalian and insect innate immunity. Genes Develop. 2001;15:2321–2342. doi: 10.1101/gad.909001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman N, Zhou R, Stöven S, Pandey N, Hultmark D, Maniatis T. A Drosophila IκB kinase complex required for Relish cleavage and antibacterial immunity. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2461–2471. doi: 10.1101/gad.817800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smoak KA, Cidlowski JA. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid receptor signaling during inflammation. Mech. Ageing Develop. 2004;125:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino RP, Carton Y, Govind S. Cellular immune response to parasite infection in the Drosophila lymph gland is developmentally regulated. Develop. Biol. 2002;243:65–80. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava DP, Yu EJ, Kennedy K, Chatwin H, Reale V, Hamon M, Smith T, Evans PD. Rapid, nongenomic responses to ecdysteroids and catecholamines mediated by a novel Drosophila G-protein-coupled receptor. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6145–6155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1005-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauszig S, Jouanguy E, Hoffmann JA, Imler JL. Toll-related receptors and the control of antimicrobial peptide expression in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:10520–10525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180130797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas HE, Stunnenberg HG, Stewart AF. Heterodimerization of the Drosophila ecdysone receptor with retinoid X receptor and ultraspiracle. Nature. 1993;362:471–475. doi: 10.1038/362471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel CS. Ecdysone-regulated puff genes 2000. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002;32:113–120. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu MP, Tatar M. Juvenile diet restriction and the aging and reproduction of adult Drosophila melanogaster. Aging Cell. 2003;2:327–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu M-P, Flatt T, Tatar M. Juvenile and steroid hormones in Drosophila melanogaster longevity. In: Masoro EJ, Austad SN, editors. Handbook of the Biology of Aging. 6th edition. San Diego: Academic Press (Elsevier); 2006. pp. 415–448. [Google Scholar]

- Tzou P, De Gregorio E, Lemaitre B. How Drosophila combats microbial infection: a model to study innate immunity and host-pathogen interactions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2002;5:102–110. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodovar N, Vinals M, Liehl P, Basset A, Degrouard J, Spellman PT, Boccard F, Lemaitre B. Drosophila host defense after oral infection by an entomopathogenic Pseudomonas species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11414–11419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502240102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TT, Nestel FP, Bourdeau W, Nagai Y, Wang QY, Liao J, Tavera-Mendoza L, Lin R, Hanrahan JH, Mader S, White JH. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3 is a direct inducer of antimicrobial peptide gene expression. J. Immunol. 2004;173:2909–2912. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster JI, Tonelli L, Sternberg EM. Neuroendocrine regulation of immunity. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2002;20:125–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.082401.104914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehling M. Specific, nongenomic actions of steroid hormones. Ann. Rev. Physiol. 1997;59:365–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TG. The molecular site of action of juvenile hormone and juvenile hormone insecticides during metamorphosis: how these compounds kill insects. J. Insect Physiol. 2004;50:111–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TG, Ashok M. Insecticide resistance resulting from an absence of target-site gene product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:14040–14044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TG, Fabian J. A Drosophila melanogaster mutant resistant to a chemical analog of juvenile hormone. Develop. Biol. 1986;118:190–201. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TG, DeMoor S, Lei J. Juvenile hormone involvement in Drosophila melanogaster male reproduction as suggested by the methoprene-tolerant27 mutant phenotype. Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol. 2003;33:1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TG, Yerushalmi Y, Donnell DM, Restifo LL. Interaction between hormonal signaling pathways in Drosophila melanogaster as revealed by genetic interaction between Methoprene-tolerant and Broad-Complex. Genetics. 2006;172:253–264. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.046631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak M, Chu Y, Fang F, Xu Y, Riddiford L, Jones D, Jones G. Alternative farnesoid structures induce different conformational outcomes upon the Drosophila ortholog of the retinoid X receptor, ultraspiracle. Insect Biochem. Molec. Biol. 2004;34:1147–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Parthasarathy R, Bai H, Palli SR. Mechanisms of midgut remodeling: juvenile hormone analog methoprene blocks midgut metamorphosis by modulating ecdysone action. Mech. Develo. 2006;123:530–547. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Fang F, Chu Y, Jones D, Jones G. Activation of transcription through the ligand-binding pocket of the orphan nuclear receptor ultraspiracle. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:6026–6036. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao T-P, Forman BM, Jiang Z, Cherbas L, Chen JD, McKeown M, Cherbas P, Evans RM. Functional ecdysone receptor is the product of EcR and Ultraspiracle genes. Nature. 1993;366:476–479. doi: 10.1038/366476a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin VP, Thummel CS. Mechanisms of steroid-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005;16:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zera AJ, Zhao Z. Effect of a juvenile hormone analogue on lipid metabolism in a wing-polymorphic cricket: implications for the endocrine-biochemical bases of life-history trade-offs. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2004;77:255–266. doi: 10.1086/383500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.