Abstract

Nature routinely uses cooperative interactions to regulate cellular activity. For years, chemists have designed synthetic systems that aim toward harnessing the reactivity common to natural biological systems. By learning how to control these interactions in situ, one begins to allow for the preparation of man-made biomimetic systems that can efficiently mimic the interactions found in Nature. To this end, we have designed a synthetic protocol for the preparation of flexible metal-directed supramolecular cofacial porphyrin complexes which are readily obtained in greater than 90% yield through the use of new hemilabile porphyrin ligands with bifunctional ether–phosphine or thioether–phosphine substituents at the 5 and 15 positions on the porphyrin ring. The resulting architectures contain two hemilabile ligand–metal domains (RhI or CuI sites) and two cofacially aligned porphyrins (ZnII sites), offering orthogonal functionalities and allowing these multimetallic complexes to exist in two states, “condensed” or “open”. Combining the ether–phosphine ligand with the appropriate RhI or CuI transition-metal precursors results in “open” macrocyclic products. In contrast, reacting the thioether–phosphine ligand with RhI or CuI precursors yields condensed structures that can be converted into their “open” macrocyclic forms via introduction of additional ancillary ligands. The change in cavity size that occurs allows these structures to function as allosteric catalysts for the acyl transfer reaction between X-pyridylcarbinol (where X = 2, 3, or 4) and 1-acetylimidazole. For 3-and 4-pyridylcarbinol, the “open” macrocycle accelerates the acyl transfer reaction more than the condensed analogue and significantly more than the porphyrin monomer. In contrast, an allosteric effect was not observed for 2-pyridylcarbinol, which is expected to be a weaker binder and is unfavorably constrained inside the macrocyclic cavity.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, chemists have been designing synthetic systems that incorporate cofacial porphyrin entities.1–10 These systems are of particular interest owing to their unique photophysical properties,11–15 their ability to catalyze small molecule transformations,16–20 and their use in molecular recognition.21,22 Among these, cofacial porphyrin compounds exhibit unique properties attributed to their spatial arrangement with respect to each other, and therefore, the ability to control that arrangement via incorporation of multiple pophyrins in supramolecular arrays offers a potentially facile route to biomimetic structures with novel physicochemical properties.23,24 Taking inspiration from nature, a primary goal of our research has been to prepare supramolecular structures that exhibit allosteric behavior in the context of catalysis and small-molecule/ion sensing analgous to that displayed ubiquitously in natural enzymatic regulation.25–28 In this context, we reasoned that the ability to manipulate the distance between porphyrins by altering the shape and size of supramolecular cavities in which they reside, via external stimuli, may provide a means for designing abiotic allosteric mimics of biological systems. Indeed, a clear inspiration for this kind of allosteric control over the function of multi-porphyrin assemblies comes from perhaps the most famous example of allosteric control in biology, the cooperative homoallosteric protein hemoglobin, in which O2 binding at one subunit initiates conformational changes that facilitate subsequent O2 binding at other porphyrin domains.29

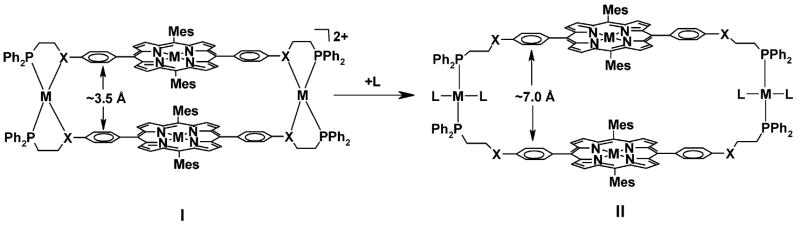

To design synthetic allosteric porphyrin-based structures, an attractive strategy entails the preparation of structures that provide facile control over both the orientation and distance of both porphyrins in the context of a small molecule-mediated reaction. To date, most approaches for the synthesis of cofacial porphyrins rely on the use of covalently attached organic molecules as spacers between the porphyrin units.6,9,21,30–32 As cofacial porphyrins have been prepared predominantly through synthetic organic approaches, only a few examples exist in which transition metals have been incorporated to facilitate the formation of cofacial porphyrins.24,33–36 Additionally, the backbones used to couple these cofacial porphyrins are often based upon rigid linker molecules, which restrict the overall flexibility of the molecule and make the incorporation of different substrates with varying size and shape challenging. To address this issue, several cofacial porphyrin structures have been designed which incorporate flexible linkages.22,37–40 However, few are able to specifically access a particular conformation via the introduction or removal of small-molecule effectors at a distal site (i.e., in an allosteric fashion). To this end, we hypothesized that coordination complexes of type I and II (Scheme 1), whose cavity size can be modified in situ with small molecules to form II would be very useful for designing stimulant-responsive porphyrin-based biomimetic systems.

Scheme 1. Design of Allosteric Porphyrin-Based Supramolecules Whose Cavity Sizes Can Be Modified by the Binding of a Ligand La.

a I: Condensed Macrocycle, II: Open Macrocycle. PPh2 = diphenylphosphine and MES = 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene.

Herein, we present a general, high-yielding synthetic methodology for the synthesis of cofacial porphyrin complexes that utilizes flexible porphyrin-based hemilabile ligands and MI precursors (where MI = RhI or CuI) to form macrocyclic products that can be chemically stimulated to change shape. Our strategy, based upon the Weak-Link Approach (WLA),41–43 provides rapid and convergent access to unique cofacial porphyrin systems because it relies on the use of metal-heteroatom interactions to facilitate the formation of the desired macrocyclic structures, thus allowing for the controlled and selective modification of the resulting structures in situ via introduction of specific external stimuli. Such stimulation can be used to tune the efficiency of a distance-dependent bimolecular acyl transfer reaction and discriminate geometric isomers of substituted pyridylcarbinol substrates.

General Methods and Instrument Details

All reactions were carried out under an inert atmosphere of nitrogen using standard Schlenk techniques or an inert atmosphere glovebox unless otherwise noted. Tetrahydrofuran (THF), diethyl ether (Et2O), dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), acetonitrile (CH3CN), and hexanes were purified according to published methods.44 All solvents were deoxygenated with nitrogen or argon prior to use. 1-Chloro-2-diphenylphos-phinoethane (Organometallics Inc.), deuterated solvents (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories Inc.), [Rh(NBD)Cl]2 (NBD = norbornadiene, Strem Chemicals), and 4-bromothiophenol (Alfa Aesar) were obtained from commercial sources and used as received. 4-(2-Chloroethoxy)-benzaldehyde,45 2-(4-bromophenylsulfanyl) ethyldiphenylphosphane,46 5-mesityldipyrromethane,47 and (2-(mesitylthio)ethyl)diphenylphosphine48 were prepared according to literature procedures. The synthesis of [5,10,15,20-tetraphenylporphyrinato]zincII (Zn(TPP))49 was adapted from a literature synthetic procedure. All other chemicals were used as received from Aldrich Chemical Co. 1H NMR (300.22 MHz) and 13C{1H} NMR (75.50 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury 300 MHz FT-NMR spectrometer and referenced relative residual proton resonances. 31P{1H} NMR (121.53 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury 300 MHz FT-NMR spectrometer and referenced relative to an external 85% H3PO4 standard. All chemical shifts are reported in ppm. Electrospray ionization mass spectra (ESIMS) were recorded on a Micromass Quatro II triple quadrapole mass spectrometer or a Micromass Q-Tof Ultima mass spectrometer. Electron impact mass spectra (EIMS) were recorded on a Fisions VG 70-250 SE mass spectrometer. Elemental analyses were performed by Quantitative Technologies Inc., Whitehouse, NJ. Gas chromatography (GC) analyses of reaction mixtures were carried out on a computer-interfaced Agilent Technologies 6890 Network instrument equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID). The column used was a 30-m HP-5 capillary column with a 0.32-mm inner diameter and a 0.25-μm film thickness. GC yields were determined through integration of the product peak against biphenyl (internal standard) using pre-established response factors. GC retention times of products were confirmed with analytically pure samples.

2-[4-(2-Chloroethoxy)-phenyl]-[1,3]dithiane (1)

Under ambient conditions, 4-(2-chloroethoxy)benzaldehyde (3.00 g, 16.3 mmol) and 1,3-propanedithiol (1.95 mL, 19.2 mmol) were combined with CH3-CN (100 mL) in a 250-mL round-bottom flask and allowed to stir at room temperature for 5 min at which point Y(OTf)3 (437 mg, 5 mol %) was added. The resulting solution was stirred for another 30 min when it gradually became turbid due to product precipitation. The mixture was dried on a rotary evaporator to give an oily residue which was then dissolved in CH2Cl2 (100 mL), washed with H2O (2 × 25 mL), dried over MgSO4, and concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified via column chromatography (1:1 v/v, CH2Cl2/hexanes as an eluent) to yield 1 as a white solid (3.38 g, 75% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.80 (m, 1H, CH2–CHAHB–CH2), 2.14 (m, 1H, CH2–CHAHB–CH2), 2.86 (m, 2H, SCH2), 2.92 (m, 2H, SCH2), 3.81 (t, 2H, CH2Cl), 4.21 (t, 2H, OCH2), 5.15 (s, 1H, S–CH–S), 6.87 (d, 2H, JH–H = 8.4 Hz, ArH), 7.37 (d, 2H, JH–H = 8.7 Hz, ArH). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3): δ 25.2 (CH2–CH2–CH2), 32.4 (CH2–CH2–CH2), 42.0 (ClCH2), 50.8 (S–CH–S), 68.2 (OCH2), 115.0 (ArC), 129.3 (ArC), 132.3 (CHCipso), 158.3 (OCipso). EIMS (m/z): Calcd. 274.03 [M]+. Found: 274.02. Elemental analysis for C12H15ClOS2: Calcd. C, 52.44; H, 5.50. Found: C, 52.35; H, 5.44.

[2-(4-[1,3]Dithian-2-yl-phenoxy)ethyl]diphenylphosphane (2)

In a 100-mL Schlenk round-bottom flask, 1 (1.00 g, 3.64 mmol) was dissolved in THF (50 mL). To this solution, KPPh2 (7.28 mL of a 0.5 M solution in THF, 3.64 mmol) was added over 10 min and allowed to stir for an additional 30 min. The solvent was removed, and the residue was extracted with degassed CH2Cl2/H2O. The solvent was removed from the organic fraction, yielding 2 as an off-white solid, which was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/hexanes (1.37 g, 86% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ1.83 (m, 1H, CH2–CHAHB–CH2), 2.11 (m, 1H, CH2–CHAHB–CH2), 2.54 (t, 2H, CH2P), 2.84 (m, 2H, SCH2), 3.01 (m, 2H, SCH2), 4.07 (q, 2H, OCH2), 5.12 (s, 1H, S–CH–S), 6.73 (d, 2H, JH–H = 8.7 Hz, ArH), 7.31–7.50 (br m, 12H, P(Ar–H)). 13C{1H}NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 25.3 (CH2–CH2–CH2), 28.3 (CH2–CH2–CH2), 28.5 (CH2–CH2–CH2), 32.3 (CH2P), 50.8 (S–CH–S), 65.5, 65.8, 114.8 (ArC), 128.7 (ArC), 128.8 (ArC), 129.0 (ArC), 129.0 (ArC), 131.9 (ArC), 132.7 (ArC), 133.0 (ArC), 138.3 (ArC), 138.4 (CHCipso), 158.7 (OCipso). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ −21.6 (s). EIMS (m/z): Calcd. 421.11 [M]+. Found: 421.10. Elemental analysis for C24H25OPS2: Calcd. C, 67.90; H, 5.94. Found: C, 67.02; H, 5.86.

2-{4-[2-(Diphenylphosphinothioyl)ethoxy]phenyl}-(1,3)dithiane (3)

In a 100-mL Schlenk round-bottom flask, 2 (1.18 g, 2.76 mmol) and elemental sulfur (88.5 mg, 2.76 mmol) were stirred in THF (50 mL) for 4 h at which point the solvent was removed in vacuo and recrystallized from CH2Cl2/hexanes to yield 3 as a light-yellow microcrystalline solid (1.23 g, 97% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.83 (m, 1H, CH2–CHAHB–CH2), 2.11 (m, 1H, CH2–CHAHB–CH2), 2.84 (m, 6H, (SCH2)2 and CH2P), 4.35 (m, 2H, OCH2), 5.11 (s, 1H, S–CH–S), 6.62 (d, 2H, JH–H = 8.7 Hz, ArH), 7.27 (d, 2H, JH–H = 8.4 Hz, ArH), 7.46–7.91 (br m, 10H, P(ArH)). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3): δ 25.2 (CH2–CH2–CH2), 32.4 (CH2–CH2–CH2), 33.0 (CH2–CH2–CH2), 50.9 (CH2P=S), 53.6 (S–CH–S), 62.5 (OCH2), 114.8 (ArC), 128.8 (ArC), 129.0 (ArC), 129.1 (ArC), 131.1 (ArC), 131.3 (ArC), 131.8 (ArC), 131.9 (ArC), 132.2 (ArC), 133.3 (ArC), 158.1 (OCipso). 31P-{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 39.3 (s). EIMS (m/z): Calcd. 456.08 [M+]. Found. 456.07. Elemental analysis for C24H25OPS3: Calcd. C, 68.84; H, 5.23. Found: C, 67.43; H, 4.90.

4-[2-(Diphenylphosphinothioyl)ethoxy]benzaldehyde (4)

Under ambient conditions, NaNO2 (226 mg, 3.27 mmol) and acetyl chloride (0.233 mL, 3.27 mmol) were stirred in in CH2Cl2 (10 mL) a 100-mL round-bottom flask at 0 °C for 10 min. A solution of 3 (500 mg, 1.09 mmol) in CH2Cl2 was added and stirred for an additional 5 min at 0°C. At this point, H2O (5 mL) was added and the reaction was brought to room temperature and allowed to stir for an hour. The reaction was neutralized with a saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3 and was extracted with CH2Cl2 (50 mL). The organic layer was washed with H2O (2 × 10 mL) and dried over MgSO4. After removing the solvent in vacuo, the crude product was purified via column chromatography (1:1 v/v, ethyl acetate/hexanes as eluent) yielding 4 as a light-yellow microcrystalline solid (352 mg, 88% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 2.98 (m, 2H, CH2P), 4.46 (m, 2H, OCH2), 6.78 (d, 2H, JH–H = 9 Hz, ArH), 7.48–7.91 (br m, 12H, P(ArH)), 9.84 (s, 1H, CHO). 13C{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 32.1 (d, JC–P = 56 Hz, CH2P=S), 63.0 (OCH2), 114.8 (ArC), 128.8 (CipsoCHO), 128.9 (ArC), 130.4 (ArC), 131.1 (ArC), 131.2 (ArC), 131.9 (ArC), 132.4 (ArC), 133.5 (ArC), 163.2 (CipsoO), 190.7 (CHO). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 39.2 (s). EIMS (m/z): Calcd. 366.08 [M+]. Found. 366.08. Elemental analysis for C21H19O2PS: Calcd. C, 63.13; H, 5.52. Found: C, 62.68; H, 5.22.

5,15-Bis-{4-[2-(diphenylphosphinothioyl)ethoxy]phenyl}-10,20-bis-(mesityl)porphyrin (5)

In an aluminum-foil-wrapped 1000-mL Schlenk round-bottom flask, 4 (1.47 g, 4 mmol), 5-mesityldipyrromethane (1.06 g, 4 mmol), and activated molecular sieves (4 Å) were stirred in CHCl3 (600 mL) and degassed under a stream of N2 for 15 min. BF3•OEt2 (0.420 mL) was added dropwise to this solution, and the resulting mixture was allowed to stir for 3 h under N2. DDQ (1.09 g, 4.8 mmol) was then added as a solid under a stream of N2, and the reaction was allowed to stir for an additional 30 min at which point NEt3 (4 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 min before being filtered through a pad of Celite to remove the sieves. The solution was concentrated in vacuo and the resulting residue was dissolved in a minimum amount CH2Cl2 and poured on top of a silica gel column and purified via flash chromatography (eluent CH2Cl2) to yield 5 as a purple microcrystalline solid (1.01 g, 41% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ −2.69 (s, 2H, NH), 1.82 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.66 (s, 6H, CH3), 3.16 (m, 4H, CH2P=S), 4.66 (m, 4H, OCH2), 7.07 (d, 4H, JH–H = 7.8 Hz, ArH), 7.30 (s, 4H), 7.59 (br s, 12H, ArH), 7.96 (m, 12H, ArH), 8.65 (d, 4H, JH–H = 5.1 Hz, ArH), 8.79 (d, 4H, JH–H = 4.5 Hz, ArH). 31P{1H}NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 39.5 (s). ESIMS (m/z): Calcd. 1219.4 [M+]. Found: 1219.3. Elemental analysis for C78H68N4O2P2S2: Calcd. C, 76.82; H, 5.62; N, 4.59. Found: C, 76.04; H, 5.18; N, 4.65.

[5,15-Bis-{4-[2-(diphenylphosphinothioyl)ethoxy]phenyl}-10,20-bis-(mesityl)porphyrinato]zinc (II) (6)

Under ambient conditions, 5 (500 mg, 0.399 mmol) and Zn(OAc)2•2H2O (700 mg, 3.19 mmol) were combined in a 500-mL round-bottom flask and stirred under reflux for 4 h in a CHCl3/CH3OH (4:1 v/v, 350 mL) solution. The solution was then washed with H2O (100 mL) and extracted with CHCl3 (2 × 100 mL). The organic layer was further washed with H2O (100 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated to give 6 as a purple microcrystalline solid (507 mg, 96% yield). 1H NMR (THF-d8): δ 1.83 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.60 (m, 6H, CH3), 2.79 (m, 4H, CH2P=S), 4.36 (m, 4H, OCH2), 7.16 (br m, 28H, ArH), 8.09 (d, 4H, JH–H = 8.4 Hz, ArH), 8.61 (d, 4H, JH–H = 4.5 Hz, ArH), 8.77 (d, 4H, JH–H = 4.5 Hz, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (THF-d8): δ 39.2 (s). ESIMS (m/z): Calcd. 1282.8 [M+]. Found: 1282.2. Elemental analysis for C78H66N4O2P2S2Zn: Calcd. C, 73.03; H, 5.19 H; N, 4.37. Found: C, 72.89; H, 5.23; N, 4.17.

[5,15-Bis-[4-(2-diphenylphosphanylethoxy)phenyl]-10,20-bis-(mesityl)porphyrinato]zinc(II) (7)

In a 50-mL Schlenk round-bottom flask, 6 (300 mg, 0.234 mmol) and Cp2ZrHCl (392 mg, 1.52 mmol) were stirred in THF under N2 (40 mL) at 60 °C for 4 h. The solvent was removed and the reaction was purified via column chromatography (silica gel, THF) in a glove box under an atmosphere of N2. The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield 7 as a purple microcrystalline solid (254 mg, 89% yield). 1H NMR (THF-d8): δ 1.83 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.60 (s, 6H, CH3), 2.77 (m, 4H, CH2P), 4.36 (m, 4H, CH2O), 7.17 (d, 4H, JH–H = 6.6 Hz, ArH), 7.30–7.61 (bm, 24H, ArH), 8.01 (d, 4H, JH–H = 8.7 Hz, ArH), 8.64 (d, 4H, JH–H = 4.5 Hz, ArH), 8.78 (d, 4H, JH–H = 4.5 Hz, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (THF-d8): δ −21.2 (s). ESIMS (m/z): Calcd. 1218.74 [M+]. Found: 1217.4. Elemental analysis for C78H66N4O2P2Zn: Calcd. C, 76.87; H, 5.46; N, 4.60. Found: C, 76.37; H, 5.18; N, 4.45.

[(7)RhCl(CO)]2 Macrocycle (8a)

A small vial was charged with [Rh(CO)2(Cl)]2 (4.80 mg, 0.0123 mmol) and CH2Cl2 (2 mL). The resulting solution was stirred for 1 min, at which point a solution of 7 (30.0 mg, 0.0246 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added dropwise over 1 min. The resulting solution was stirred for 3 h. The solvent was removed and the product was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/pentane (32.1 mg, 94% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.54 (s, 24H, CH3), 2.56 (s, 12H, CH3), 3.34 (br m, 8H, CH2P), 4.81 (br m, 8H, CH2O), 7.10 (br m, 22H, ArH), 7.47 (m, 22H, ArH), 7.90 (br m, 20H, ArH), 8.79 (br m, 16H, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 21.6 (d, JRh–P = 124 Hz). ESIMS (m/z) for [C156H132N8O4P4Rh2Zn2(CO)2]2+: Calcd. 1349.6. Found: 1349.3. Elemental analysis for C158H132Cl2N8O6P4Rh2Zn2: Calcd. C, 68.51; H, 4.80 H; N, 4.04. Found: C, 68.38; H, 4.91; N, 3.52.

[(7)Cu(CH3CN)2(PF6)]2 Macrocycle (8b)

A 50-mL Schlenk flask was charged with [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6 (29.8 mg, 0.0799 mmol) and CH2-Cl2 (5 mL). A THF solution of 7 (100 mg, 0.0799 mmol, 20 mL) was added to the “Cu” solution dropwise over 5 min at room temperature to give a red/purple solution, which was then allowed to stir for 3 h. The solvent was removed to yield a purple microcrystalline solid which was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/pentane (107 mg, 92% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.66 (s, 24H, CH3), 2.07 (s, 12H, CH3CN), 2.43 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.95 (br m, 8H, CH2P), 4.46 (br m, 8H, CH2O), 7.10 (s, 22H, ArH), 7.50 (s, 22H, ArH), 7.62 (12H, ArH), 8.00 (d, 8H, JH–H = 7.8 Hz, ArH), 8.64 (d, 8H, JH–H = 4.2 Hz, ArH), 8.78 (d, 8H, JH–H = 4.2 Hz, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ −11.5 (s). ESIMS (m/z) for [C156H132N8S4P4Cu2Zn2]2+: Calcd. 1282.2. Found: 1282.4. Elemental analysis for [C164H144N12O4P6F12Zn2Cu2]: Calcd. C, 65.25; H, 4.81; N, 5.57. Found: C, 65.32; H, 4.56; N, 6.35.

1-Bromo-4-[2-(diphenylphosphinothioyl)ethylsulfanyl]-benzene (9)

In a 100-mL Schlenk round-bottom flask, 2-(4-bromo-phenylsulfanyl)-ethyldiphenylphosphane (3.00 g, 7.48 mmol), and elemental sulfur (264 mg, 8.22 mmol) were stirred in THF (150 mL) under N2 for 3 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo, and the product was purified via column chromatography (1:1 v/v, CH2Cl2/hexanes). Compound 9 was isolated as an off-white microcrystalline solid (3.02 g, 92% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 2.68 (m, 2H, CH2P=S), 3.10 (m, 2H, SCH2), 7.12 (d, 2H, JH–H = 8.7 Hz, ArH), 7.39 (d, 2H, JH–H = 8.7 Hz, ArH), 7.48–7.79 (m, 10H, P(ArH)). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3): δ 26.9 (SCH2), 32.3 (d, CH2P=S, JC–P = 51.3 Hz), 128.9 (ArC), 129.1 (ArC), 131.0 (ArC), 131.1 (ArC), 131.2 (ArC), 131.6 (ArC), 132.0 (ArC), 132.3 (ArC). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 41.4 (s). EIMS (m/z): Calcd. 431.97 [M+]. Found: 431.97. Elemental analysis for C20H18-BrPS2: Calcd. C, 55.43; H, 4.19. Found: C, 55.59, H, 4.07.

4-[2-(Diphenylphosphinothioyl)ethylsulfanyl]benzaldehyde (10)

Compound 9 (3.00 g, 6.90 mmol) was dissolved in THF (60 mL) in a 100-mL Schlenk round-bottom flask and was cooled to −78 °C. n-BuLi (2.76 mL, 6.90 mmol, 2.5 M in hexanes) was added dropwise to the solution over 5 min and the mixture was allowed to stir for 30 min, before DMF (0.802 mL, 10.35 mmol) was added to the flask. This solution was cooled to −78 °C and allowed to stir for an additional 30 min before the temperature was allowed to rise back to room temperature. The mixture was quenched with H2O followed by extraction with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo to give a yellow crude product which was then recrystallized (CH2Cl2/pentane) to yield 10 as a light-yellow microcrystalline solid (2.35 g, 88% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 2.76 (m, 2H, CH2P=S), 3.23 (m, 2H, SCH2), 7.29 (d, 2H, JH–H = 6.6 Hz, ArH) 7.47 (m, 6H, P(ArH)), 7.73 (d, 2H, JH–H = 8.7 Hz, ArH), 7.79 (m, 4H, P(ArH)), 9.92 (s, 1H, CHO). 13C{1H} NMR (CDCl3): δ 25.0 (SCH2), 32.0 (d, CH2P=S, JC–P = 51.3 Hz), 126.8 (ArC), 129.0 (ArC), 129.1 (ArC), 130.4 (ArC), 131.1 (ArC), 131.3 (ArC), 132.1 (ArC), 132.5 (ArC), 191.4 (CHO). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 41.5 (s). EIMS (m/z): Calcd. 382.01 [M+]. Found. 382.06. Elemental analysis for C21H19-OPS2: Calcd. C, 65.94; H, 5.01. Found: C, 65.23; H, 4.71.

[5,15-Bis-[4-(2-diphenylphosphinothioylethylsulfanyl)phenyl]-10,-20-bis-(mesityl)porphyrin (11)

In an aluminum-foil-wrapped 1000-mL Schlenk flask, compound 10 (1.23 g, 3.20 mmol), 5-mesityldipyrromethane (848 mg, 3.20 mmol), and activated molecular sieves (4 Å) were stirred in CHCl3 (600 mL) and degassed under a stream of N2 for 15 min. BF3•OEt2 (0.350 mL) was added dropwise to this solution, and the resulting mixture was allowed to stir for 3 h under N2. DDQ (862 mg, 3.8 mmol) was then added as a solid under a stream of N2, and the reaction was allowed to stir for an additional 30 min at which point NEt3 (4 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 min before being filtered through a pad of Celite to remove the sieves. The solution was concentrated in vacuo and the resulting residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 and poured on top of a silica gel column (eluent CH2Cl2). Subsequent chromatography yielded 11 as a purple microcrystalline solid (879 mg, 44% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ −2.67 (s, 2H, NH), 1.84 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.63 (s, 6H, CH3), 3.03 (m, 4H, CH2P=S), 3.42 (m, 4H, SCH2), 7.31 (s, 4H, mesityl H), 7.55 (m, 16H, ArH), 7.89 (m, 8H, ArH), 8.13 (d, 4H, JH–H = 8.1 Hz, ArH), 8.69 (d, 4H, JH–H = 5.1 Hz, ArH), 8.82 (d, 4H, JH–H = 4.8 Hz, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 41.6 (s). ESIMS (m/z): Calcd. 1251.6 [M+]. Found: 1251.3. Elemental analysis for C78H68N4P2S4: Calcd. C, 74.85; H, 5.48; N, 4.48. Found: C, 74.35; H, 4.98; N, 4.43.

[5,15-Bis-[4-(2-diphenylphosphinothioylethylsulfanyl)phenyl]-10,-20-bis(mesityl)porphyrinato] zinc(II) (12)

In a 250-mL round-bottom flask, 11 (400 mg, 0.319 mmol) and Zn(OAc)2•2H2O (700 mg, 3.19 mmol) were refluxed for 3 h in a CHCl3/CH3OH (4:1 v/v, 200 mL) solution. The solution was washed with H2O (100 mL) and extracted with CHCl3 (2 × 50 mL). The organic layer was washed again with H2O (50 mL), dried over Na2SO4, and concentrated to give 12 as a purple microcrystalline solid (412 mg, 98% yield). 1H NMR (CD2-Cl2): δ 1.82 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.63 (s, 6H, CH3), 3.03 (m, 4H, CH2P=S), 3.41 (m, 4H, SCH2), 7.31 (s, 4H, ArH), 7.54 (m, 12H, ArH), 7.89 (m, 12H, ArH), 8.12 (d, 4H, JH–H = 8.4 Hz, ArH), 8.76 (d, 4H, JH–H = 5.1 Hz, ArH), 8.89 (d, 4H, JH–H = 4.8 Hz, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2-Cl2): δ 41.6 (s). ESIMS (m/z): Calcd. 1314.9 [M+]. Found: 1314.1. Elemental analysis for C78H66N4P2S4Zn: Calcd. C, 71.24; H, 5.06; N, 4.26. Found: C, 70.69; H, 4.97; N, 3.94.

[5,15-Bis-[4-(2-diphenylphosphanylethylsulfanyl)phenyl]-10,20-bis(mesityl)porphyrinato]zinc(II) (13)

In a 50-mL Schlenk flask, 12 (300 mg, 0.228 mmol) and Cp2ZrHCl (382 mg, 1.48 mmol) were stirred in THF (40 mL) at 60 °C for 3 h. The solvent was removed, and the product was purified via column chromatography (THF, silica gel) in a glove box under an atmosphere of N2. The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield 13 as a purple microcrystalline solid (251 mg, 88% yield). 1H NMR (THF-d8): δ 1.84 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.47 (m, 4H, CH2P), 2.61 (s, 6H, CH3), 3.23 (m, 4H, SCH2), 7.29 (br m, 28H, ArH), 8.09 (d, 4H, JH–H = 7.8 Hz, ArH), 8.64 (d, 4H, JH–H = 4.8 Hz, ArH), 8.79 (d, 4H, JH–H = 4.2 Hz, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (THF-d8): δ −15.2 (s). ESIMS (m/z): Calcd. 1250.8 [M+]. Found: 1249.4. Elemental analysis for C78H66N4P2S2Zn: Calcd. C, 74.90; H, 5.32; N, 4.48. Found: C, 73.15; H, 4.94; N, 4.16.

[(13)Rh(BF4)]2 Condensed Macrocycle (14a)

A small vial was charged with [Rh(NBD)Cl]2 (31.0 mg, 0.068 mmol), AgBF4 (26.0 mg, 0.135 mmol), and CH2Cl2 (4 mL). This solution was stirred for 1 h and then filtered dropwise through Celite into a Schlenk flask. The red solution was then diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) to give a clear yellow/orange solution. A solution of ligand 13 (170 mg, 0.135 mmol) in THF (20 mL) was added to the “Rh” solution dropwise over 5 min at room temperature to give a dark-purple solution, which was then stirred for an additional 3 h. The solvent was removed to yield 14a as a purple microcrystalline solid which was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/pentane (176 mg, 90% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.48 (br s, 24H, CH3), 2.44 (br s, 12H, CH3), 2.76 (br m, 8H, CH2P), 3.20 (br m, 8H, CH2S), 6.98 (br m, 8H, ArH), 7.37 – 7.59 (br m, 40H, ArH), 8.02 (br m, 16H, ArH), 8.50 (br m, 16H, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 64.1 (d, JRh–P = 162 Hz). ESIMS (m/z) for [C156H132N8S4P4Rh2Zn2]2+: Calcd.1353.7. Found: 1354.1. Elementalanalysisfor[C156H132B2F8N8S4P4-Rh2Zn2]: Calcd. C, 65.03; H, 4.62; N, 3.89. Found: C, 65.56; H, 4.11; N, 3.46.

[(13)Cu(PF6)]2 Condensed Macrocycle (14b)

A 50-mL Schlenk flask was charged with [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6 (29.8 g, 0.0799mmol). The CuI precursor was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (5 mL), and a THF solution of ligand 13 (100 mg, 0.0799 mmol, 20 mL) was added to the “Cu” solution dropwise over 5 min at room temperature to give a red/purple solution. The solution was then allowed to stir for 3 h. The solvent was removed to yield 14b as a purple microcrystalline solid which was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/pentane (105 mg, 90% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.75 (br s, 24H, CH3), 2.55 (br s, 12H, CH3), 3.00 (br m, 8H, CH2P), 3.65 (br m, 8H, CH2S), 7.24 – 7.82 (br m, 56H, ArH), 8.16 (br m, 8H, ArH), 8.76 (br s, 16H, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ1.0 (s). ESIMS (m/z) for [C156H132N8S4P4Cu2Zn2]2+: Calcd. 1314.4. Found: 1314.5. Elemental analysis for [C156H132N8S4P6F12Cu2Zn2]CH2-Cl2: Calcd. C, 62.78; H, 4.50; N, 3.73. Found: C, 61.95;H, 4.18; N, 3.31.

[(13)RhCl(CO)]2 Macrocycle (15a)

Compound 14a (20.0 mg, 0.00694 mmol) was dissolved in CD2Cl2 (1 g) and placed in an air-free NMR tube. PPNCl (Bis(triphenylphosphoranylidene) ammonium chloride, 2 equiv) was added and the NMR tube was then pressurized with CO (1 atm) for 30 s. Compound 14a was quantitatively converted to 15a as determined by 31P NMR spectroscopy. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.77 (br s, 24H, CH3), 2.54 (br s, 12H, CH3), 3.14 (br m, 8H, CH2P), 3.48 (br m, 8H, CH2S), 7.26 – 8.01 (br m, 124H, (C6H5)3PPN, P(C6H5)2, ArH), 8.65 – 8.80 (br m, 16H, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 22.1 (s, PPNCl), δ 25.1 (d, JRh–P = 123 Hz). ESIMS (m/z) for [C156H132N8S4P4-Rh2Zn2]2+ (M –2(Cl−/CO)): Calcd. 1353.7. Found: 1353.7.

[(13)Cu(pyridine-d5)2(PF6)]2 Macrocycle (15b)

Compound 14b (20.0 mg, 0.00640 mmol) was dissolved in CD2Cl2 (1 g) and placed in an air-free NMR tube. C5D5N (4 equiv.) was added to this solution and the conversion of 15b was quantitative as determined by 1H NMR and 31P NMR spectroscopy. 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 1.72 (br s, 24H, CH3), 2.45 (br s, 12H, CH3), 2.82 (br m, 8H, CH2P), 3.38 (br m, 8H, CH2S), 7.17 – 7.55 (br m, 56H, ArH), 8.04 (d, 8H, JH–H = 7.8 Hz, ArH), 8.64 (d, 8H, JH–H = 4.5 Hz, ArH), 8.70 (d, 8H, JH–H = 4.8 Hz, ArH). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ −8.0 (s). ESIMS (m/z) for [C156H132N8S4P4Cu2Zn2]2+: Calcd. 1314.4. Found: 1314.9.

[(Ph2PCH2CH2S–C6H2(CH3)3)2Rh]BF4 Condensed Tweezer-Type Complex (16a)

A 20-mL vial was charged with [Rh(NBD)Cl]2 (63.2 mg, 0.137 mmol), AgBF4 (53.4 mg, 0.274 mmol), and CH2Cl2 (4 mL). This solution was stirred for 1 h and then filtered dropwise through Celite into a Schlenk flask. The orange solution was then diluted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) to give a clear yellow solution. A solution of (2-(mesitylthio)ethyl)diphenylphosphine (200 mg, 0.549 mmol) in CH2-Cl2 (20 mL) was added to the “Rh” solution dropwise over 5 min at room temperature to give a clear yellow solution, which was then stirred for an additional 3 h. The solvent was removed to yield 16a as a yellow microcrystalline solid which was recrystallized from CH2Cl2/pentane (113 mg, 90% yield). 1H NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 2.22 (d, 12H, CH3), 2.51 (br s, 10H, CH3 and SCH2CH2P), 2.83 (br m, 4H, CH2P), 6.71 (s, 4H, ArH), 7.23 – 7.34 (br m, P(Ar–H)2, 20H). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 63.0 (d, JRh–P = 163 Hz). ESIMS (m/z) for [C46H50N8S2P2Rh]+: Calcd. 831.8. Found: 831.6.

(Ph2PCH2CH2S–C6H2(CH3)3)2RhCl(CO) Open Tweezer-Type Complex (16b)

Compound 16a (15.0 mg, 0.0163 mmol) was dissolved in CD2Cl2 (1 g) and placed in an air-free NMR tube. PPNCl (bis(triphenylphosphoranylidene)ammonium chloride, 9.38 mg, 0.0163 mmol) was added as a solid and the NMR tube was then pressurized with CO (1 atm) for 30 s. Compound 16a was quantitatively converted to 16b as determined by 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy. 1H NMR (CD2-Cl2): δ 2.25 (s, 6H, CH3), 2.37 (s, 12H, CH3), 2.67 (br m, 4H, CH2P), 2.82 (br m, 4H, CH2S), 6.90 (s, 4H, ArH), 7.34 – 7.65 (br m, 50H, (C6H5)3PPN, P(Ar–H)2). 31P{1H} NMR (CD2Cl2): δ 22.1 (s, PPNCl), δ 23.5 (d, JRh–P = 123 Hz). ESIMS (m/z) for [C46H50N8S2P2Rh]+ (M– (Cl−/CO)): Calcd. 831.8. Found: 831.2.

General Procedure for Catalysis Experiments

The formation of 2-, 3-, and 4-acetoxymethylpyridine were monitored by GC relative to an internal standard (biphenyl) and quantified using a previously established calibration curve. Experiments containing 14a, 15a, or a mixture of an analogous monomeric RhI complex (16a or 16b) and Zn(TPP) (as the control), respectively, were run concurrently in separate vials at room temperature in CH2Cl2 under an atmosphere of N2 inside a glove box.

GC Experiments for the Closed Macrocycle (14a)

Inside a glove box, CH2Cl2 stock solutions of complex 14a (0.58 mL of a 2.6 mM solution), biphenyl (0.5 mL of a 25 mM solution), and pyridylcarbinol (0.5 mL of a 90 mM solution) were added to a 20-mL vial. Fresh CH2-Cl2 was added to the vial bringing the total reaction volume up to 4.5 mL. After stirring for 5 min, 1-acetylimidazole (0.5 mL of a 60 mM solution) was added to the vial (t = 0). At various times, an aliquot (100 μL) was taken from the solution and added to diethyl ether (2 mL). This was then passed down a plug of Celite (3 cm × 0.5 cm) to remove the catalyst. The plug was further treated with fresh diethyl ether (5 mL). The combined organics were used for GC analysis.

GC Experiments for the Open Macrocycle (15a)

Inside a glove box, complex 14a (0.58 mL of a 2.6 mM solution) and benzyltriethylammonium chloride (0.5 mL of a 6.4 mM solution) were added to a 10-mL Schlenk flask. The flask was removed from the glove box and placed on a Schlenk line where CO (1 atm) was bubbled through the solution for 30 s resulting in the formation of 15a. The flask was brought back into the glove box and the contents were transferred into a vial. Fresh CH2Cl2 was added to the flask and transferred into the vial bringing the total reaction volume up to approximately 4 mL. Pyridylcarbinol (0.5 mL of a 90 mM solution) and biphenyl (0.5 mL of a 25 mM solution) were added to the vial and after stirring for 5 min, 1-acetylimidazole (0.5 mL of a 60 mM solution) was added to the flask (t = 0). At various times, an aliquot (100 μL) was taken from the solution and added to diethyl ether (2 mL). This was then passed down a plug of Celite (3 cm × 0.5 cm) to remove the catalyst. The plug was further treated with fresh diethyl ether (5 mL). The resulting samples were used for GC analysis.

GC Control Experiments for RhI-Monomer (16a) and Porphyrin Monomer (Zn(TPP))

Inside a glove box, CH2Cl2 stock solutions of complex 16a (0.892 mL of a 8.0 mM solution), biphenyl (0.5 mL of a 25 mM solution), Zn(TPP) (0.20 mL of a 15 mM solution), and pyridylcarbinol (0.5 mL of a 90 mM solution) were added to a 20-mL vial. Fresh CH2Cl2 was added to the vial bringing the total reaction volume up to 4.5 mL. After stirring for 5 min, 1-acetylimidazole (0.5 mL of a 60 mM solution) was added to the vial (t = 0). At various times, an aliquot (100 μL) was taken from the solution and added to diethyl ether (2 mL). This was then passed down a plug of Celite (3 cm × 0.5 cm) to remove the catalyst. The plug was further treated with fresh diethyl ether (5 mL). The combined organics were used for GC analysis.

GC Control Experiments for RhI-Monomer (16b) and Porphyrin Monomer

Inside a glove box, complex 16a (0.892 mL of a 8.0 mM solution), Zn(TPP) (0.20 mL of a 15 mM solution), and benzyltriethylammonium chloride (1.0 mL of a 6.4 mM solution) were added to a 10-mL Schlenk flask. The flask was removed from the glove box and placed on a Schlenk line where CO (1 atm) was bubbled through the solution for 30 s resulting in the formation of 16b. The flask was brought back into the glove box and the contents were transferred into a vial. Fresh CH2Cl2 was added to the flask and transferred into the vial bringing the total reaction volume up to approximately 4 mL. Pyridylcarbinol (0.5 mL of a 90 mM solution) and biphenyl (0.5 mL of a 25 mM solution) were added to the vial and after stirring for 5 min, 1-acetylimidazole (0.5 mL of a 60 mM solution) was added to the flask (t = 0). At various times, an aliquot (100 μL) was taken from the solution and added to diethyl ether (2 mL). This was then passed down a plug of Celite (3 cm × 0.5 cm) to remove the catalyst. The plug was further treated with fresh diethyl ether (5 mL). The combined organics were used for GC analysis.

Results and Discussion

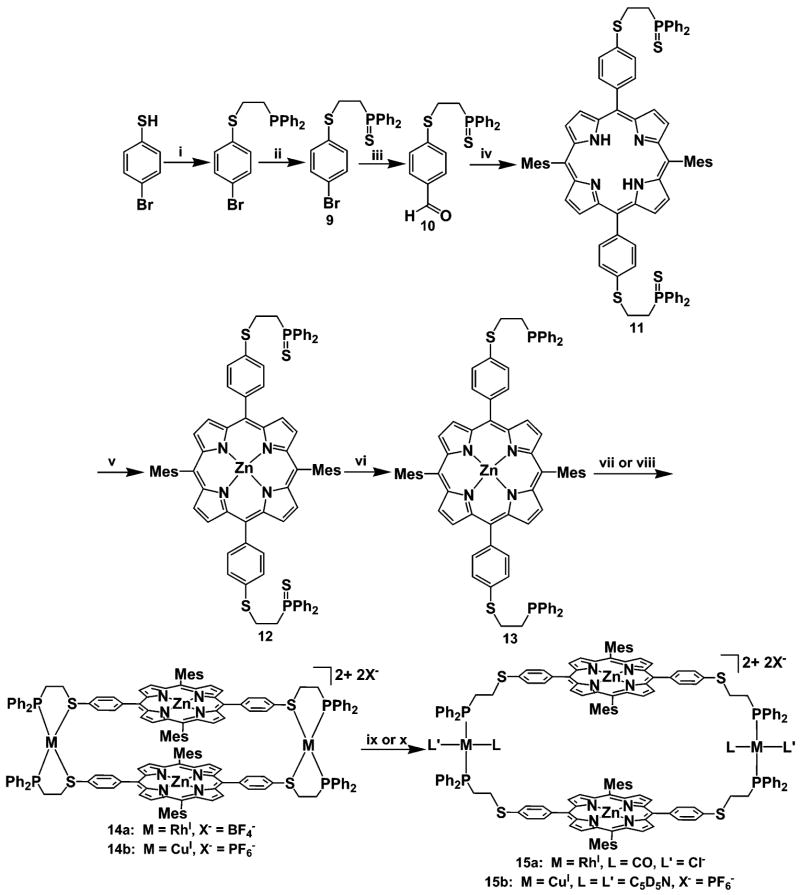

The Design of Ether–Phosphine Hemilabile Ligand 7

To design porphyrin-based supramolecular systems capable of in situ allosteric activity, flexibility must be engineered into the backbone of the framework as well as “weak” and “strong” binding structural domains. To this end, we synthesized two new hemilabile porphyrin ligands which incorporate “weak” ether or thioether functionalities in addition to “strong” phosphine binding sites. Ether-based ligand 7 was obtained in eight steps from 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (Scheme 2). 4-Hydroxy-benzaldehyde was alkylated with excess 1-bromo-2-chloroethane to yield 4-(2-chloroethoxy)benzaldehyde, which was transformed into 3 after a dithiane protection of the aldehyde, conversion of the chloride to the corresponding phosphine, and reaction with elemental sulfur. Deprotection of the dithiane moiety in 3, followed by condensation of the resulting aldehyde with 5-mesityldipyrromethane affords the freebase porphyrin 5 in gram quantities after column chromatography. Metalation with Zn(OAc)2•2H2O gave compound 6, and desulfurization with Schwartz’s reagent gave ligand 7 in 12% overall yield. The use of a sulfide as the protecting group for the phosphine moiety not only allowed for a convenient nonaqueous protection/deprotection sequence, but also significantly increased the scalability and the yield of the porphyrin synthesis while simplifying the complicated purification and isolation process that often accompanies porphyrin syntheses. Indeed, if one uses an oxide protecting group as opposed to the sulfide, the ligand adheres to the silica column used for chromatography and makes the isolation of the pure product difficult.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Ether-Based Ligand 7 and Macrocycles 8a and 8ba.

a (i) 1-bromo-2-chloroethane, K2CO3, Acetone, Reflux; (ii) 1,3-propanedithiol, Y(OTf)3 (5 mol %), CH3CN; (iii) KPPh2, THF; (iv) S8, THF;(v) NaNO2, AcCl/H2O, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → rt; (vi) 5-mesityldipyrromethane, BF3•OEt2, DDQ, NEt3, CHCl3, 4 Å Molecular Sieves; (vii) Zn(OAc)2•2H2O, 4:1 CHCl3/MeOH, Reflux; (viii) Cp2ZrHCl, THF, 60 °C; (ix) [Rh(CO)2(Cl)]2, CH2Cl2/THF; (x) [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6, CH2Cl2/THF.

Reactivity of Ligand 7 with RhI and CuI

Initially, our attention was focused on the design, synthesis, and isolation of RhI and CuI condensed intermediates of type I using ligand 7. Unfortunately, isolation of these products proved impossible under the conditions explored. However, we discovered that the “open” macrocyclic structure 8a can be obtained directly in quantitative yield upon reaction of ligand 7 with [Rh(CO)2(Cl)]2. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 8a exhibits a single resonance at δ 21.6 (d, JRh–P = 124 Hz), diagnostic of a highly symmetrical porphyrin complex with trans-phosphines and is consistent with the proposed structural formulation for 8a.50 ESIMS analysis of 8a shows a parent ion at m/z 1349.3, indicating the loss of each Cl− ligand bound to the RhI centers. RhI complexes with analogous coordination environments often lose these ligands during ESIMS.50

Similar to the reactivity exhibited with RhI, ligand 7 forms the analogous “open” macrocyclic product 8b when reacted with [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 8b exhibits a singlet at δ −11.5 consistent with a tetrahedral CuI–P environment.51 The resonance is substantially shifted downfield from the one observed for free ligand at δ −21.2. Characterization of this product via ESIMS leads to the observation of a parent ion at m/z 1282.4 which corresponds to the loss of two CH3CN molecules from each CuI metal center. This is consistent with the known lability of the bound CH3CN molecules, which has been observed in analogous systems.51

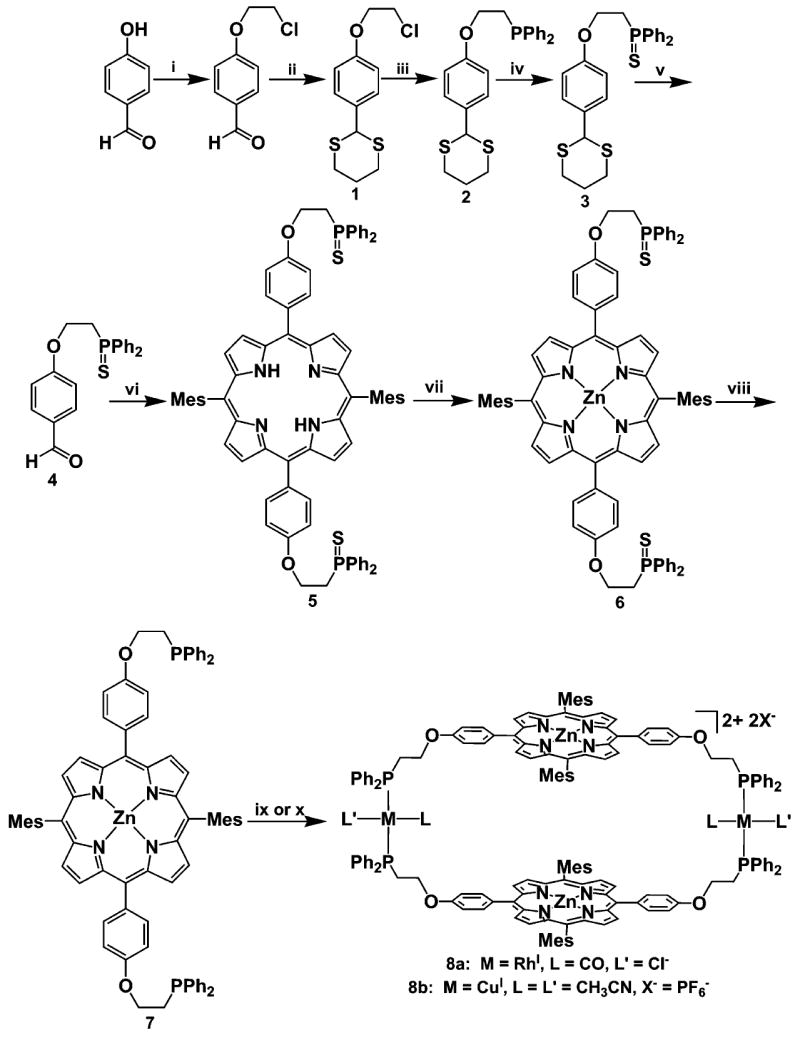

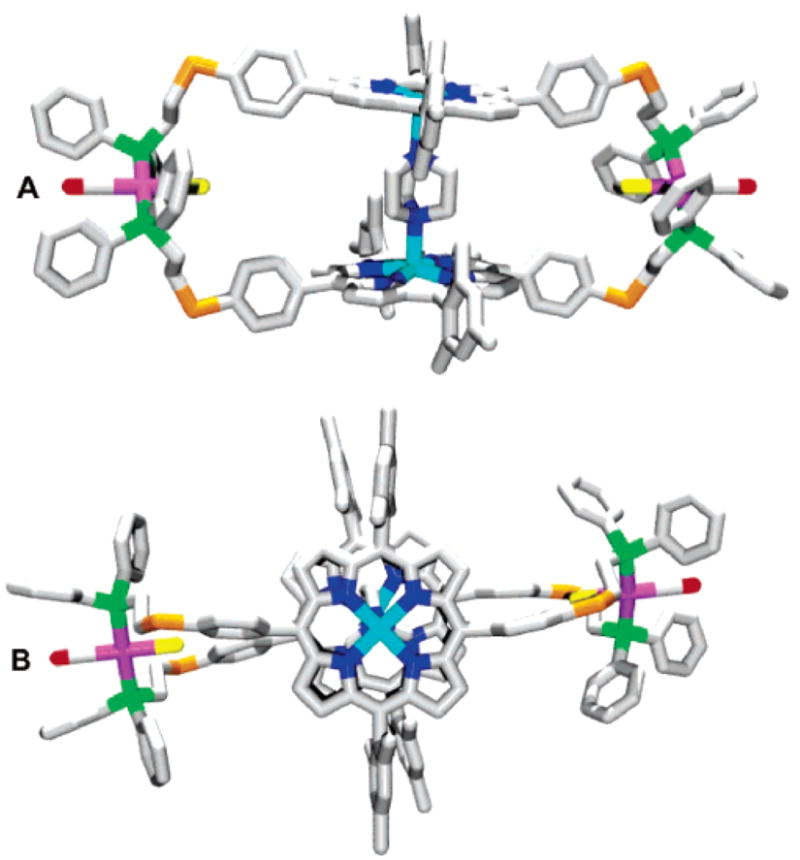

X-ray Structure Determination of 8a⊂DABCO and 8c⊂DABCO

Initial attempts to grow crystals of 8a in a variety of solvent mixtures proved unsuccessful, presumably due to the large free volume and flexibility of the cavity. We hypothesized that crystals of 8a could be obtained in the presence of a ligand that can span and coordinate to the two Zn-centers within the macrocycle, filling the free volume and rigidifying the overall structure. Indeed, X-ray quality crystals were obtained from vapor diffusion of pentane/diethyl ether (1:1 v/v) into a THF/CH2Cl2 (1:1 v/v) solution of 8a containing DABCO which was layered with acetonitrile. The 56-membered macrocyclic product 8a⊂DABCO contains two porphyrin moieties aligned and locked into a cofacial arrangement in the solid-state by a DABCO ligand (Figure 1). The Zn–Zn distance of 7.09 Å is significantly longer than the P–Rh–P distance of 4.64 which is made possible by the flexible (CH2)2O linkages between the porphyrin moieties and the RhI hinges. This large porphyrin–porphyrin distance allows for the mesityl arms of the porphyrin moieties to align in a near superimposable fashion.

Figure 1.

Graphical representations of the X-ray crystal structure of 8a⊂DABCO as viewed (A) from the side and (B) from the top containing a molecule of DABCO bridging both Zn atoms. Hydrogen atoms, disordered DABCO carbon atoms, and solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity. Pink = Rh, Red = O, Yellow = Cl, Green = P, Blue = N, Light Blue = Zn.

Attempts to crystallize 8b in a similar manner led to an unexpected reaction with the halogenated solvent. Because the solubility of 8b in pure THF is poor, a mixture of solvents proved to be the most effective for crystallization. Analytically pure samples of 8b were dissolved in a THF/CH2Cl2 solution containing DABCO which was first layered with acetonitrile following by a slow second layer of a solution of pentane/diethyl ether (1:1 v/v). X-ray quality crystals were obtained from this mixture after 1 day and subjected to single-crystal diffraction analysis at the Advanced Photon Source (APS, Argonne National Laboratory). Although 8b has been shown to contain four molecules of CH3CN and two PF6− counterions according to elemental analysis, the diffraction experiment yielded a structure with DABCO bridging both Zn-atoms and two Cl− anions bound to each tetrahedral Cu metal center, indicating an oxidation of the original CuI center to CuII forming 8c⊂DABCO (see Supporting Information). Such a compound could be formed from the dehalogenation of alkyl halide solvents (i.e., CH2Cl2 and CHCl3) by the CuI center in 8b, similar to that observed by Karlin et al. for (TMPA)CuI (TMPA= (tris-(2-pyridylmethyl)amine)) in CH2Cl2.52–54 That 8c⊂DABCO possesses the framework expected for 8b supports our assignment of an open macrocyclic structure for the product isolated from the reaction of 7 and [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6.

Synthesis of Thioether–Phosphine Hemilabile Ligand 13

Because type I structures are difficult to access from the ether–phosphine ligand 7, we hypothesized that isostructural ligands containing thioether linkages would be more effective at forming condensed structures as has been observed previously with analogous smaller molecules.50 To this end, we modified the synthesis of 7 to obtain the thioether-based porphyrin ligand 13 in six steps (Scheme 3). First, 4-bromothiophenol was stoichiometrically alkylated with 1-chloro-2-diphenylphosphinoethane to yield 2-(4-bromophenylsulfanyl)ethyldiphenyl phosphine. To protect the phosphine moiety from oxidation during the porphyrin synthesis, reaction with elemental sulfur yields phosphine sulfide 9, which was then formylated with n-BuLi and DMF. The resulting aldehyde 10 was subsequently condensed with 5-mesityldipyrromethane in the presence of BF3•OEt2 to yield porphyrin 11 in 44% yield after a very simple chromatographic separation. Freebase porphyrin 11 was metallated with Zn(OAc)2•2H2O to give 12 and followed by deprotection of the phosphine with Schwartz’s reagent to yield the phosphine derivative 13 in 33% overall yield.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Thioether-Based Ligand 13 and Macrocycles 14a–b, 15a–ba.

a (i) ClCH2CH2PPh2, Cs2CO3, CH3CN, Reflux; (ii) S8, THF; (iii) n-BuLi, DMF, THF, −78 °C; (iv) 5-mesityldipyrromethane, BF3•OEt2, DDQ, NEt3, CHCl3, 4 Å Molecular Sieves; (v) Zn(OAc)2•2H2O, 4:1 CHCl3/MeOH, Reflux; (vi) Cp2ZrHCl, THF, 60 °C; (vii) for 14a: [Rh(NBD)Cl]2, AgBF4, CH2Cl2/THF; (viii) for 14b: [Cu(CH3CN)4]PF6, CH2Cl2/THF; (ix) for 15a: PPNCl/CO (1 atm); (x) for 15b: C5D5N.

Reactivity of Hemilabile Ligand 13 with RhI and CuI

In contrast to the results obtained from ether ligand 7, thioether ligand 13 reacts cleanly with “Rh(NBD)BF4”55 to form the condensed intermediate 14a. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 14a exhibits a doublet at δ 64.5 (JRh–P = 162 Hz) which is highly diagnostic of its symmetrical structure and cis-Rh–P coordination centers.50 Additionally, ESIMS analysis shows a peak corresponding to the M2+ ion at 1354.1 m/z, indicating the formation of the desired condensed structure. Significantly, compound 14a can be opened into macrocycle 15a by introduction of benzyltriethyl ammonium chloride or by PPNCl (where PPNCl = bis(triphenylphosphoranylidene)ammonium chloride) and CO. This transformation can be followed by 31P{1H} NMR through the appearance of a doublet at δ 25.1 (d, JP–Rh = 123 Hz), significantly upfield from the resonance for 14a. This resonance is characteristic of a trans-phosphine environment about the RhI metal center and indicates a conversion from a condensed macrocyclic intermediate to the “open” macrocycle15a.50 The ESIMS spectrum of 15a exhibits a peak at 1353.7 m/z, corresponding to the M2+ ion without the Cl− and CO ligands and is consistent with ESIMS data for analogous structures.26

We observed condensed intermediate 14b as the sole product from the reaction between thioether-based ligand 13 and [Cu-(CH3CN)4]PF6. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 14b exhibits a singlet at δ 1.0 which is highly diagnostic of a tetrahedral environment at the CuI metal center.51 Additionally, ESIMS analysis yields a peak corresponding to the M2+ ion at 1314.5 m/z, indicating formation of the desired condensed structure. Notably, compound 14b can be converted into macrocycle 15b upon the addition of stoichiometric quantities of pyridine. Once again, the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum allows us to monitor this transformation through the appearance of a singlet at δ −8.0, which has shifted upfield from the resonance observed for 14b. The ESIMS analysis of 15b yields a peak at 1314.9 m/z which corresponds to the pyridine-free molecular ion.

X-ray Structure Determination of 15a⊂DABCO and 15c⊂DABCO

Similar to the problems encountered in crystallizing 8a, our attempts to isolate X-ray quality single crystals of 14a and 15a proved unfruitful. Based upon the more promising strategy of adding DABCO to pure samples of 8a, we hypothesized that crystals of 15a⊂DABCO could be obtained in a similar fashion. X-ray quality crystals were obtained from vapor diffusion of pentane/diethyl ether (1:1 v/v) into a THF/CH2Cl2 solution of 15a containing DABCO, which was initially layered with acetonitrile. Similar to the analogous structure 8a⊂DABCO, the 56-membered macrocyclic product 15a⊂DABCO represents one of the largest macrocycles ever prepared via the Weak-Link Approach. In this structure, the Zn atoms are separated by a distance of distance of 7.02 Å and are bridged by a DABCO ligand (Figure 2). The structure of 15a⊂DABCO is slightly puckered toward the Zn(porphyrin) centers, leading to a slightly staggered porphyrin–porphyrin geometry. As expected, the Rh–P and Zn–Zn distance in 8a⊂DABCO are comparable to those found for 15a⊂DABCO while the Rh–Rh distance differs significantly, presumably due to the presence of the four S atoms which have been incorporated in 15a⊂DABCO (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Graphical representations of the X-ray crystal structure of 15a⊂DABCO as viewed (A) from the side and (B) from the top containing a molecule of DABCO bridging both Zn atoms. Hydrogen atoms, disordered DABCO carbon atoms and solvent molecules have been omitted for clarity. Gray = Carbon, Pink = Rh, Red = O, Orange = S, Yellow = Cl, Green = P, Dark Blue = N, Light Blue = Zn.

Table 2.

Selected Distances for 8a⊂DABCO and 15a⊂DABCO

| selected distance | 8a⊂DABCO (Å) | 15a⊂DABCO (Å) |

|---|---|---|

| Rh–Rh | 24.8 | 22.5 |

| Rh–P | 2.32, 2.31 | 2.30 |

| Zn–Zn | 7.09 | 7.02 |

Contrary to 8b, 15b was quite soluble in pure THF; however, our efforts to crystallize 15b from THF only yielded microcrystalline powder. Attempts to crystallize 15b using the same conditions as used for 8b led to the formation of magenta single crystals of 15c⊂DABCO, which were confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis at APS (see Supporting Information). Macrocycle 15c⊂DABCO encapsulates a bridging DABCO ligand between two Zn porphyrins, flanked by tetrahedral CuCl2 centers, again indicating the oxidation of CuI to CuII via solvent dehalogenation as has been observed previously. As for 8c⊂DABCO, isolation of 15c⊂DABCO strongly suggests an open macrocyclic structure for 15b as shown in Scheme 3.

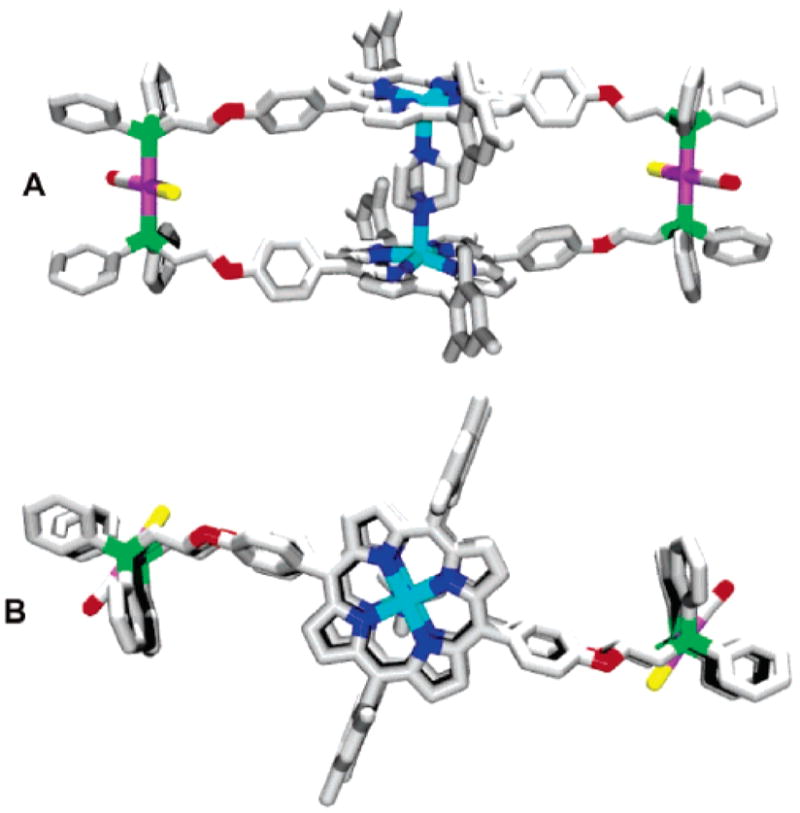

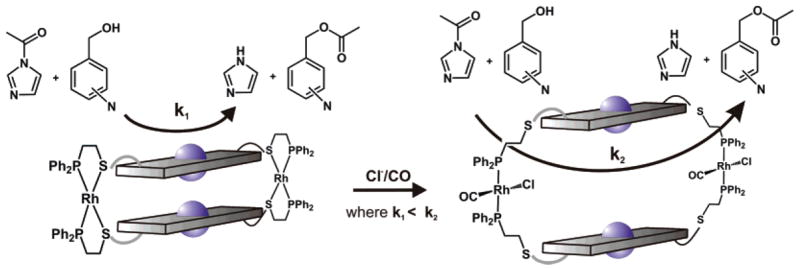

Acyl Transfer Catalytic Experiments

To demonstrate the ability of the ZnII–porphyrin moieties in 14a and 15a to act cooperatively in an allosterically controlled fashion, we employed a catalytic acyl transfer reaction that has been shown by Sanders and co-workers to accelerate in the presence of trimetallic Lewis acidic porphyrin assemblies.56 We hypothesized that the pyridylcarbinol and acetylimidazole substrates could be brought together within the cavity of 15a by cofacial ZnII metal centers and converted to the products in a catalytic fashion by virtue of their proximity (Figure 3). Furthermore, reactions involving 1-acetylimidazole and differentially substituted X-pyridylcarbinol (where X = 2, 3, or 4) can be used to evaluate the ability of 15a to act allosterically: only the combination of substrates with the right distance can span the cavity and react at an accelerated rate.

Figure 3.

Acyl transfer reactions catalyzed by (left) a closed macrocycle vs (right) the corresponding open macrocycle. The open macrocycle can preorganize the substrates within the cavity, thereby increasing the rate of the reaction (k2) in comparison to that (k1) observed in the presence of the closed macrocycle.

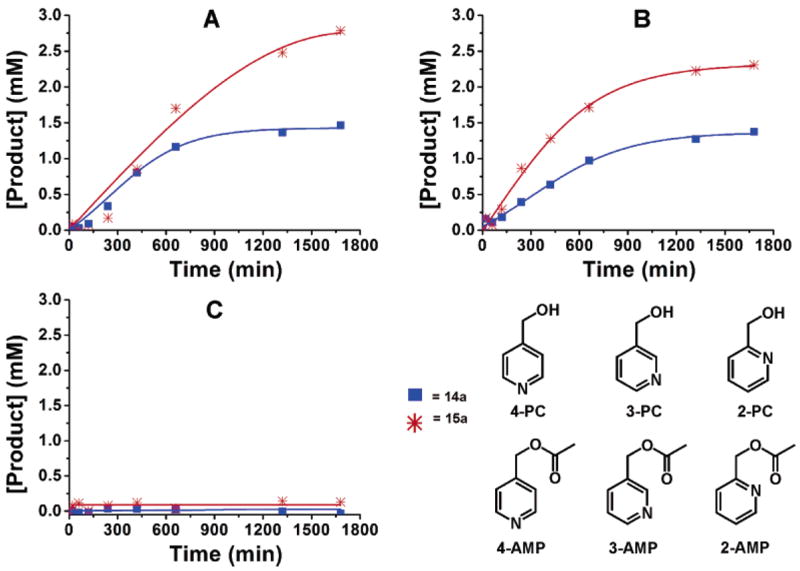

The efficiency of both the “closed” (14a) and “open” (15a) supramolecular catalysts in the acyl transfer reaction were evaluated against a control reaction consisting of the monomer Zn(TPP) and analogous monomeric RhI complexes 16a and 16b (see Supporting Information). For 4-pyridylcarbinol (4-PC), both 14a and 15a significantly accelerate the reaction rate, with the open macrocycle 15a being almost 14 times more active than the monomers and twice as fast as the closed macrocycle 14a (Figure 4a). While 14a is depicted as a rigid entity in Figure 3, its structure is probably dynamic when in solution and the observed catalytic activity may originate from the conformational flexibility around the S atoms and the low rotational barrier of the porphyrin ligand about the carbon-sulfur bond in the backbone of the ligand. For 3-pyridylcarbinol (3-PC), the background-corrected ratemacrocycle/ratemonomers ratio (ratemonomers = rate of the reaction in the presence of the [RhI monomer + Zn(TPP)] mixture) and the observed allosteric effect (rate15a/rate14a) only drops slightly (Figure 4b), suggesting that the cavities of 14a and 15a are still flexible enough to accommodate the change in transition state distance for acyl transfer from acetylimidazole upon binding. For 2-pyridylcarbinol (2-PC), both the ratemacrocycle/ratemonomers ratio and the observed allosteric effect (rate15a/rate14a) drop significantly with respect to 3- and 4-pyridylcarbinol and are similar to those observed for the monomers (Figure 4c). This may be explained by a simple geometry argument: if 2-pyridylcarbinol is bound to one of the Zn centers, the carbinol group will be pointed away from the imidazole N-acetyl group bound to the other side, resulting in an unfavorable transition state (in comparison to those for 4-and 3-pyridylcarbinol) for productive acyl transfer.

Figure 4.

Formation of the three X-(acetoxymethyl)pyridine (X = 2, 3, or 4) isomers by an acyl transfer reaction between 1-acetylimidazole and X-pyridylcarbinol, as catalyzed by Zn–porphyrin complexes 14a and 15a. Concentration vs time plots are shown for the formation of 4-(acetoxymethyl)-pyridine (A, 4-AMP), 3-(acetoxymethyl)pyridine (B, 3-AMP), and 2-(acetoxymethyl)pyridine (C, 2-AMP). All data were corrected for background reactions (see Supporting Information). Conditions: CH2Cl2, rt, 9 mM X-pyridylcarbinol, 6 mM 1-acetylimidazole, 2.5 mM biphenyl (GC reference standard), and 0.3 mM supramolecular catalyst (14a and 15a). CO (1 atm) and appropriate amounts of benzyltriethylammonium chloride when indicated.

Our catalytic data offers strong evidence that Cl−/CO can act as positive allosteric effectors in a RhI-based hemilabile supramolecular catalyst system, enhancing the efficiency of bimolecular acyl transfer reactions when the geometry is optimized. Significantly, these effectors operate cooperatively with each other and are incapable of effecting shape change if added independently to the RhI species. That 2-pyridylcarbinol can be selectively discriminated against 3- and 4-pyridylcarbinol provides an impetus for employing these supramolecular assemblies for chemical sensing and shape-selective recognition when coupled to catalytic processes that provide signal amplification.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a coordination chemistry-based synthetic approach for the quantitative preparation of flexible cofacial porphyrin assemblies in which the porphyrins act as functional sites within an allosteric framework that is tunable via modulation of peripheral structure control domains. Importantly, these architectures possess cavities whose sizes can be directly controlled in situ via the introduction of simple, cooperative ancillary ligands that bond to the structure control domains. This capability enables the cofacial porphyrin structures to act as allosteric catalysts capable of discriminating different substrate combinations and selectively transforming them into the desired products, two key steps in developing new biomimetic supramolecular systems. Most notably, our synthetic approach should allow for facile access to a range of systems with tunable cofacial porphyrin–porphyrin distances that are useful in studying distance-dependent electron-transfer phenomena, molecular switches, host–guest interactions, and catalysis. Efforts toward elaboration of these areas are currently underway.

Supplementary Material

Crystallographic data, X-ray crystal structures of 8c⊂DABCO and 15c⊂DABCO, and uncorrected and background reactions for 2-PC, 3-PC, and 4-PC. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Table 1.

X-ray Crystallographic Data for 8a⊂DABCO and 15a⊂DABCO

| 8a⊂DABCO | 15a⊂DABCO | |

|---|---|---|

| empirical formula | C181H166Cl4N12O8P4Rh2Zn2 | C172H142Cl2N10O4P4Rh2S4Zn2 |

| formula weight | 3239.5 | 3072.54 |

| Temperature | 153(2) K | 100(2) K |

| Wavelength | 0.71073 Å | 0.48595 Å |

| crystal system, space group | triclinic, P1̄ | monoclinic, C2/c |

| unit cell dimensions | a = 13.9395(13) Å α = 83.044(2)° | a = 17.0086(10) Å |

| b = 17.1623(17) Å β = 73.368(2)° | b = 44.661(3) Å β= 104.252(2)° | |

| c = 20.894(2) Å γ = 74.250(2)° | c = 23.0053(13) Å | |

| volume | 4604.5(8) Å3 | 16937.3(17) Å3 |

| Z, calculated density | 1, 1.168 Mg/m3 | 4, 1.205 Mg/m3 |

| absorption coefficient | 0.581 mm−1 | 0.342 mm−1 |

| F(000) | 1678 | 6336 |

| crystal size | 0.170 × 0.170 × 0.50 mm | 0.150 × 0.025 × 0.010 mm |

| theta range for data collection | 1.02 to 28.83° | 0.90 to 15.70° |

| reflections collected/unique | 42335/21291 [R(int) = 0.0712] | 123297/12229 [R(int) = 0.0780] |

| absorption correction | integration | empirical |

| max. and min. transmission | 0.9695 and 0.8265 | 1.000000 and 0.649500 |

| refinement method | full-matrix least-squares on F2 | full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| data/restraints/parameters | 21291/0/915 | 12229/0/921 |

| goodness-of-fit on F^2 | 0.912 | 1.063 |

| final R indices [I > 2sigma(I)] | R1 = 0.0910, wR2 = 0.2301 | R1 = 0.0937, wR2 = 0.2816 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.1924, wR2 = 0.2591 | R1 = 0.1199, wR2 = 0.3081 |

| largest diff. peak and hole | 1.378 and −0.747 e−/Å−3 | 2.236 and −0.800 e−/Å−3 |

Acknowledgments

C.A.M acknowledges the NSF and ARO for support of this research and is grateful for a NIH Director’s Pioneer Award. This work was also supported, in part, by the NSF-NSEC program under NSF Award Number EEC-0118025. Portions of this work were performed at the DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access Team (DND-CAT) Synchrotron Research Center located at Sector 5 of the Advanced Photon Source. DND-CAT is supported by the E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., the Dow Chemical Company, the U.S. National Science Foundation through Grant DMR-9304725 and the State of Illinois through the Department of Commerce and the Board of Higher Education Grant IBHE HECA NWU 96. ChemMat-CARS Sector 15 is principally supported by the National Science Foundation/Department of Energy under grant number CHE0087817 and by the Illinois Board of Higher Education. The Advanced Photon Source is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Science, under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38.

References

- 1.Cowan JA, Sanders JKM. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1985:1213–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fletcher JT, Therien MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:12393–12394. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collman JP, Bencosme CS, Durand RR, Jr, Kreh RP, Anson FC. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:2699–703. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feiters MC, Fyfe MCT, Martinez-Diaz MV, Menzer S, Nolte RJM, Stoddart JF, van Kan PJM, Williams DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:8119–8120. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yagi S, Yonekura I, Awakura M, Ezoe M, Takagishi T. Chem Commun. 2001:557–558. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CJ, Yeh CY, Nocera DG. J Org Chem. 2002;67:1403–1406. doi: 10.1021/jo016095k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jokic D, Asfari Z, Weiss J. Org Lett. 2002;4:2129–2132. doi: 10.1021/ol0258583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chng LL, Chang CJ, Nocera DG. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4075–4078. doi: 10.1021/jo026610u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collman JP, Tyvoll DA, Chng LL, Fish HT. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1926–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen WH, Yan JM, Tagashira Y, Yamaguchi M, Fujita K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:891–894. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faure S, Stern C, Guilard R, Harvey PD. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1253–1261. doi: 10.1021/ja0379823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Splan KE, Stern CL, Hupp JT. Inorg Chim Acta. 2004;357:4005–4014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajjaj F, Yoon ZS, Yoon MC, Park J, Satake A, Kim D, Kobuke Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4612–4623. doi: 10.1021/ja0583214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher JT, Therien MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4298–4311. doi: 10.1021/ja012489h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobuke Y. Struct Bonding. 2006;121:145–165. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collman JP, Fu L, Herrmann PC, Zhang X. Science. 1997;275:949–951. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang CJ, Loh ZH, Shi C, Anson FC, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10013–10020. doi: 10.1021/ja049115j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenthal J, Pistorio BJ, Chng LL, Nocera DG. J Org Chem. 2005;70:1885–1888. doi: 10.1021/jo048570v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collman JP, Wagenknecht PS, Hutchison JE. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1994;106:1620–39. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenthal J, Luckett TD, Hodgkiss JM, Nocera DG. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6546–6547. doi: 10.1021/ja058731s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brettar J, Gisselbrecht JP, Gross M, Solladie N. Chem Commun. 2001:733–734. doi: 10.1039/b106337p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jokic D, Boudon C, Pognon G, Bonin M, Schenk KJ, Gross M, Weiss J. Chem– Eur J. 2005;11:4199–4209. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merlau M, Grande WJ, Nguyen ST, Hupp JT. J Mol Cat A: Chem. 2000;156:79–84. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merlau ML, del Pilar Mejia M, Nguyen ST, Hupp JT. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:4239–4242. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011119)40:22<4239::AID-ANIE4239>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heo J, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:941–944. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gianneschi NC, Bertin PA, Nguyen ST, Mirkin CA, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:10508–10509. doi: 10.1021/ja035621h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gianneschi NC, Cho SH, Nguyen ST, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:5503–5507. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gianneschi NC, Nguyen ST, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:1644–1645. doi: 10.1021/ja0437306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stryer L. Biochemistry. 4. W.H. Freeman and Company; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brothers PJ, Collman JP. Acc Chem Res. 1986;19:209–15. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chng LL, Chang CJ, Nocera DG. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4075–4078. doi: 10.1021/jo026610u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guilard R, Burdet F, Barbe JM, Gros CP, Espinosa E, Shao J, Ou Z, Zhan R, Kadish KM. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:3972–3983. doi: 10.1021/ic0501622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slone RV, Hupp JT. Inorg Chem. 1997;36:5422–5423. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dinolfo PH, Hupp JT. Chem Mater. 2001;13:3113–3125. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dinolfo PH, Lee SJ, Coropceanu V, Bredas JL, Hupp JT. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:5789–5797. doi: 10.1021/ic050834o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benkstein KD, Stern CL, Splan KE, Johnson RC, Walters KA, Vanhelmont FWM, Hupp JT. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2002:2818–2822. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohsaki K, Konishi K, Aida T. Chem Commun. 2002:1690–1691. doi: 10.1039/b202970g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomohiro Y, Satake A, Kobuke Y. J Org Chem. 2001;66:8442–8446. doi: 10.1021/jo015852b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanders JKM. Chem Eur J. 1998;4:1378–1383. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pognon G, Boudon C, Schenk KJ, Bonin M, Bach B, Weiss J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3488–3489. doi: 10.1021/ja058132l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gianneschi NC, Masar MS, III, Mirkin CA. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:825–837. doi: 10.1021/ar980101q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farrell JR, Mirkin CA, Guzei IA, Liable-Sands LM, Rheingold AL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1998;37:465–467. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980302)37:4<465::AID-ANIE465>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holliday BJ, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:2022–2043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pangborn AB, Giardello MA, Grubbs RH, Rosen RK, Timmers FJ. Organometallics. 1996;15:1518–20. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mao PCM, Mouscadet JF, Leh H, Auclair C, Hsu LY. Chem Pharm Bull. 2002;50:1634–1637. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown AM, Ovchinnikov MV, Stern CL, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14316–14317. doi: 10.1021/ja045316b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laha JK, Dhanalekshmi S, Taniguchi M, Ambroise A, Lindsey JS. Org Process Res Dev. 2003;7:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown AM, Ovchinnikov MV, Mirkin CA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:4207–4209. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomizaki K-y, Yu L, Wei L, Bocian DF, Lindsey JS. J Org Chem. 2003;68:8199–8207. doi: 10.1021/jo034861c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dixon FM, Eisenberg AE, Farrell JR, Mirkin CA, Liable-Sands LM, Rheingold AL. Inorg Chem. 2000;39:3432–3433. doi: 10.1021/ic000062q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masar MS, III, Mirkin CA, Stern CL, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:4693–4701. doi: 10.1021/ic049658u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lucchese B, Humphreys KJ, Lee DH, Incarvito CD, Sommer RD, Rheingold AL, Karlin KD. Inorg Chem. 2004;43:5987–5998. doi: 10.1021/ic0497477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyeklar Z, Richard RR, Wei N, Murthy NN, Zubieta J, Karlin KD. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;43:5987–5988. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wei N, Murthy NN, Tyeklar Z, Karlin KD. Inorg Chem. 1994;33:1177–1183. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Formed by the reaction between [Rh(NBD)Cl2 and AgBF4 (NBD = norbornadiene).

- 56.Mackay LG, Wylie RS, Sanders JKM. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:3141–3142. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Crystallographic data, X-ray crystal structures of 8c⊂DABCO and 15c⊂DABCO, and uncorrected and background reactions for 2-PC, 3-PC, and 4-PC. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.