Abstract

A triplet spin system (S = 1) is detected by low-temperature electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy in samples of diol dehydrase and the functional adenosylcobalamin (AdoCbl) analog 5′-deoxy-3′,4′-anhydroadenosylcobalamin (anAdoCbl). Different spectra are observed in the presence and absence of the substrate (R,S)-1,2-propanediol. In both cases, the spectra include a prominent half-field transition (ΔMS = 2) that is a hallmark of strongly-coupled triplet spin systems. The appearance of 59Co-hyperfine splitting in the EPR signals as well as the positions (g-values) of the signals in the spectra show that half of the triplet spin is contributed by the low spin Co2+ of cob(II)alamin. Linewidth effects from isotopic labeling (13C and 2H) in the 5′-deoxy-3′,4′-anhydroribosyl ring demonstrate that the other half of the spin triplet is from an allylic 5′-deoxy-3′,4′-anhydroadenosyl (anhydroadenosyl) radical. The zero-field splitting (ZFS) tensors describing the magnetic dipole-dipole interactions of the component spins of the triplets have rhombic symmetry because of electron spin delocalization within the organic radical component and nearness of the radical to the low spin Co2+. The dipole-dipole interaction was modeled as a summation of point-dipole interactions involving the spin-bearing orbitals of the anhydroadenosyl radical and cob(II)alamin. Geometries which are consistent with the ZFS tensors in the presence and absence of substrate position the 5′-carbon of the anhydroadenosyl radical 3.5 Å and 4.1 Å and from Co2+, respectively. Homolytic cleavage of the cobalt-carbon bond of the analog in the absence of substrate indicates that, in diol dehydrase, binding of the coenzyme to the protein weakens the bond prior to binding of substrate.

A common characteristic of AdoCbl1-dependent enzymes is the generation and utilization of enzyme-bound organic radicals (1–3). The Co–C5′ bond of AdoCbl is relatively weak having a bond dissociation energy of ~ 30 kcal mol−1 (4). A prevalent mechanism for AdoCbl-dependent enzymes begins with the homolytic cleavage of the Co–C5′ bond to give cob(II)alamin and the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (1). The 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical being an unstabilized, primary alkyl radical is expected to have a short lifetime, low concentration, and a high reactivity towards H atom abstraction. Thus far, these properties of the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical have precluded direct observation of the radical by EPR spectroscopy. Cleavage of the Co–C5′ bond is kinetically coupled to H atom abstraction from a substrate molecule in the reactions of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (5), glutamate mutase (6), ethanolamine ammonia-lyase (7), and diol dehydrase (8). These kinetic experiments have highlighted the transient nature of the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical species. In the case of the AdoCbl-dependent Class II ribonucleoside triphosphate reductase the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical abstracts an H atom from the thiol of Cys408 of the protein (9). An allosteric effector-dependent epimerization of chiral [5′-2H1]AdoCbl by the C408A and C408S mutant forms of the enzyme requires the transient existence of the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (10).

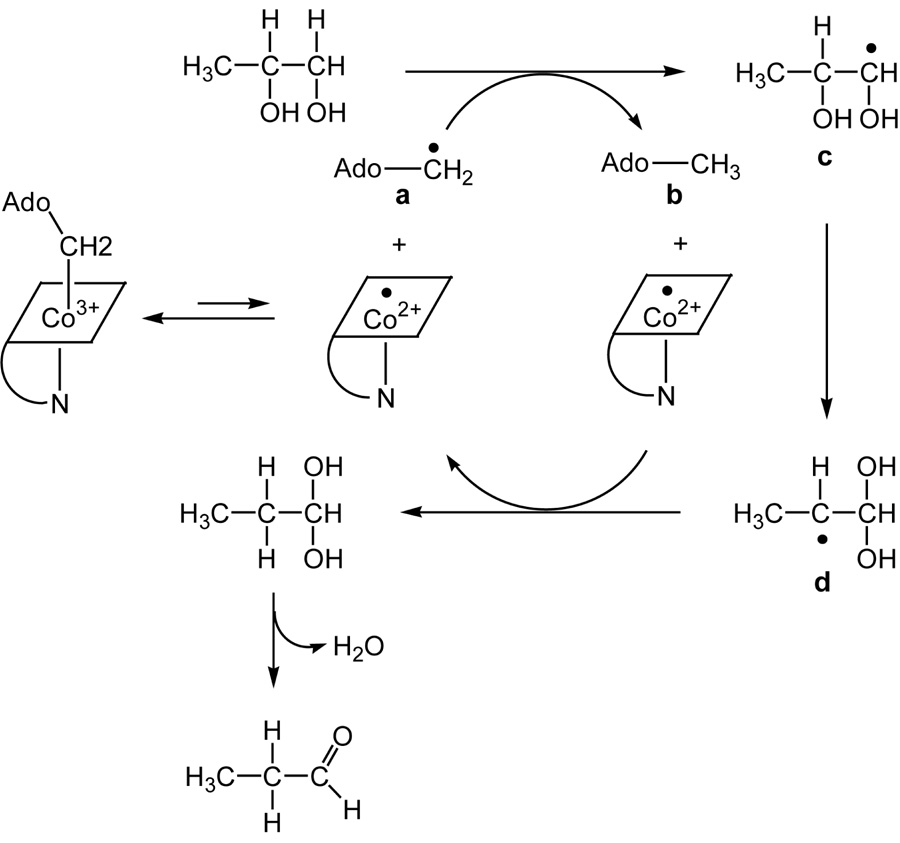

DDH (diol dehydrase, EC:4.2.1.28) uses 2- and 3-carbon vicinal diols as substrates and catalyzes their transformation into aldehydes (8, 11). The minimal mechanism for DDH with 1,2-propanediol as the substrate is depicted in Scheme 1. Reversible cleavage of the Co–C5′ bond of AdoCbl generates the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical a, which abstracts a hydrogen atom from C1 of 1,2-propanediol to produce 5′-deoxyadenosine b and the substrate radical c. The substrate radical undergoes isomerization to the product-related radical d by an unknown mechanism. Hypothetical mechanisms for the radical rearrangement include the formation of a radical cation (12) or a radical anion intermediate (13). Concerted mechanisms having transition state stabilization by partial proton transfer or deprotonation of the spectator −OH group have also been discussed (14, 15). Crystal structures of DDH reveal that the vicinyl −OH groups of 1,2-propanediol are coordinated to K+, and K+ may be involved in catalysis (16, 17). Magnetic interactions between active site radicals and the nuclear spins of 39K and 203,205Tl have, however, escaped detection by EPR and ENDOR (18). Moreover, site directed mutagenesis has revealed essential roles of Glu-α170 and Asp-α335 (19) in putative H-bonding contacts with the vicinal −OH groups of the substrate. Hydrogen transfer from 5′-deoxyadenosine b to the radical d regenerates the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical, which recombines with cob(II)alamin. The enzyme catalyzes the dehydration of the gem-diol to complete the reaction (20). Reactions of the DDH-AdoCbl complex with substrates or inhibitors elicit EPR signals corresponding to organic radicals spin coupled to the low spin Co2+ of cob(II)alamin (18, 21–26).

Scheme 1.

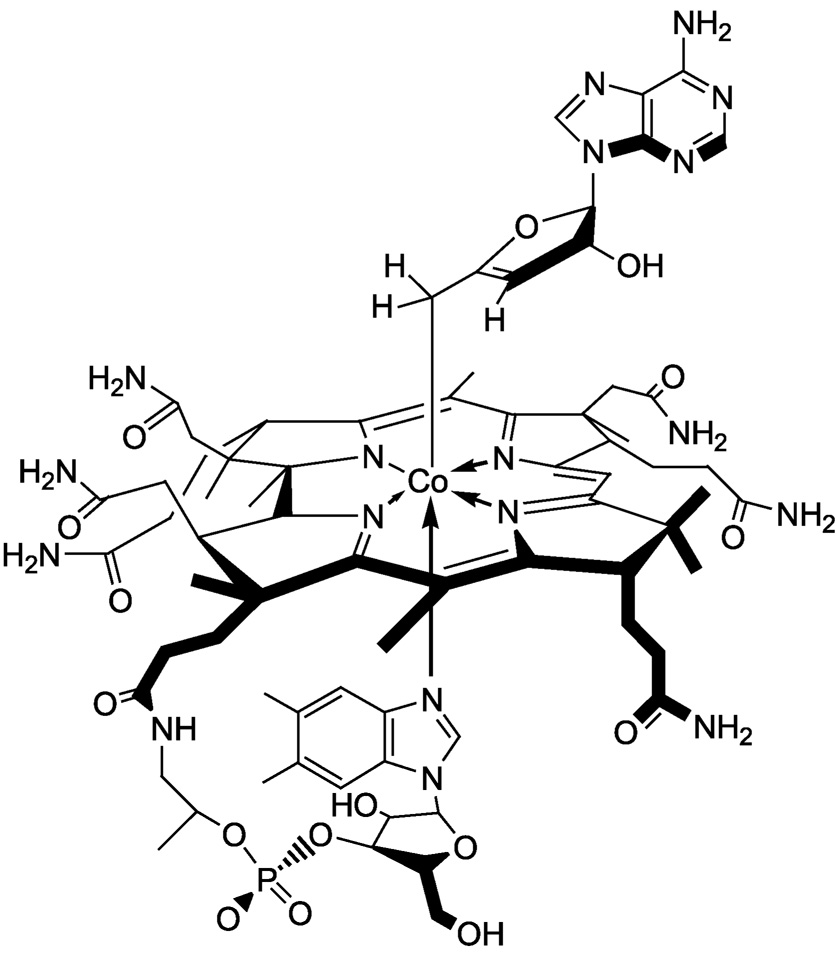

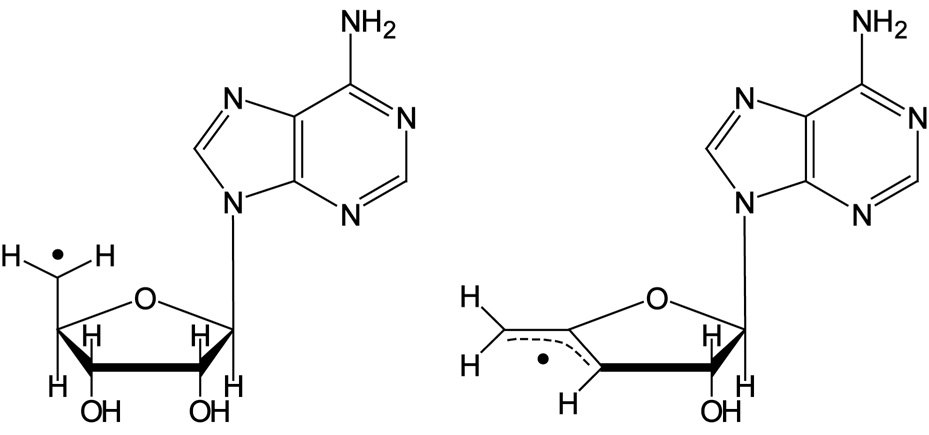

AnAdoCbl, shown in Scheme 2, is an analog of AdoCbl. AnAdoCbl has a Co–C5′ bond dissociation energy which is ~ 6 kcal mol−1 weaker than the corresponding bond in AdoCbl (27). The weakened Co–C5′ bond in anAdoCbl is attributed to allylic stabilization in the anhydroadenosyl radical relative to the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical. Structures of the two radicals are compared in Scheme 3. AnAdoCbl is a functional coenzyme for DDH, displaying a turnover rate 0.02% of that with AdoCbl as coenzyme (28). Binding of anAdoCbl to DDH induces Co–C5′ bond cleavage. The Co–C5′ bond cleavage is observed spectrophotometrically as the formation of cob(II)alamin either in the presence or absence of the substrate (28). However, the enzyme undergoes slow inactivation as observed by the formation of cob(III)alamin, irrespective of the presence of the substrate. Inactivation is a consequence of electron transfer from cob(II)alamin to the anhydroadenosyl radical and subsequent quenching of the allylic anion by a solvent derived proton (28).

Scheme 2.

Scheme 3.

Cleavage of the Co–C5′ bond of anAdoCbl generates the anhydroadenosyl radical and cob(II)alamin in the active site of DDH. The present paper presents EPR evidence for the presence of strongly-coupled spin-triplets involving the anhydroadenosyl radical and the low spin Co2+ of cob(II)alamin in complexes of DDH with the cofactor analog in the presence and absence of substrate. Analysis of the spin-triplet EPR spectra by simulation and interpretation of the ZFS in terms of molecular geometries is presented.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Sodium cholate and AdoCbl were from Sigma; (R,S)-1,2-propanediol was from Aldrich; and (R,S)-1,2-[2H6]propanediol (99.5 % 2H) was from CDN Isotopes. All other solvents, buffers and chemicals were obtained either from Fisher or Aldrich and used as supplied. anAdoCbl and [13C5-ribosyl]-anAdoCbl were synthesized as described elsewhere (27). The 13C-labeled compound was prepared from the [13C5-ribosyl]-anATP precursor, the synthesis of which is described elsewhere (29). Recombinant DDH from Salmonella typhimurium was produced in E. coli and purified and assayed as described previously (28, 30).

Sample Preparation

Samples were prepared from solutions that were kept within a Coy anaerobic chamber. The samples contained 0.2 mM DDH in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 8, 0.5 % sodium-cholate buffer in a final volume of 0.25 mL, with either anAdoCbl (0.32 mM) or [13C5-ribosyl]-anAdoCbl (0.3 mM) as coenzyme. Samples prepared with substrate contained either 0.12 M (R,S)-1,2-propandiol or 0.12 M (R,S)-1,2-[2H6]propanediol. Substrate-free samples were pre-incubated for 20 min with 1 µM AdoCbl before addition of coenzyme. This pretreatment with substoichiometric quantities of the normal cofactor ensured that residual traces of substrate, used to stabilize the enzyme during isolation and storage, would be converted to the product aldehyde. Samples were incubated at 25 °C for 1–10 min, transferred to EPR tubes and frozen by immersion of the tubes into cold isopentane (−135 °C).

EPR Spectroscopy

EPR spectra were obtained at cryogenic temperatures with a Varian spectrometer equipped with an E102 X-band microwave bridge, an Oxford Instruments ESR-900 continuous-flow helium cryostat, and an Oxford 3120 temperature controller. A Varian NMR gaussmeter, a Hewlett-Packard 5255A frequency converter and a 5245L electronic counter were used to measure the magnetic field strength and microwave frequency, respectively. The spectrometer was interfaced with a computer for data acquisition. Spin concentrations were estimated by double integration and comparison with a CuEDTA standard in water/glycerol.

Spectral Simulations

Fourier filtering methods (31, 32) were used to enhance resolution in the EPR spectra. The spectra were analyzed using the following spin Hamiltonian:

| (1) |

The first two terms in Equation 1 represent the Zeeman interaction of the low-spin Co2+ of cob(II)alamin and the anhydroadenosyl radical with the external magnetic field, respectively; the third and fourth terms represent the magnetic dipole-dipole2 (ZFS) and isotropic exchange interactions between cob(II)alamin and the anhydroadenosyl radical, respectively; and Hnuc represents the nuclear hyperfine interactions:

| (2) |

In general, Euler rotations (33) are needed to bring each of the tensors in Equation 1 and Equation 2 into a common frame of reference, in this case the g-axis system of Co2+. However, the g-tensors of organic radicals, such as the anhydroadenosyl radical, are very nearly isotropic and thus Euler angles are not required to align the two g-tensors. Also, the nuclear hyperfine interactions of the anhydroadenosyl radical and of cob(II)alamin, other than the 59Co-nucleus, are small relative to the ZFS and are safely neglected. The g-tensor and 59Co-hyperfine tensor of cob(II)alamin are collinear. Therefore, the Euler angles aligning the ZFS tensor with the g-tensor of cob(II)alamin (i.e., the angles relating the inter-spin vector to the g-axis system of Co2+) were the only angular variables in the fitting procedure. Energy levels and transition energies were obtained by diagonalization of the energy matrix. Field-swept powder EPR spectra were calculated as described previously (34). In this analysis, the 59Co-hyperfine interaction was treated to first-order, effectively reducing the energy matrix to a block diagonal form in the 59Co nuclear quantum number, mI. Initial estimates of the ZFS parameters were taken from the measured turning points in the experimental spectra, and the Co2+ g-values and hyperfine parameters were obtained from previously reported values of cob(II)alamin bound to methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (35). These values were refined (changed slightly) by trial-and-error until reasonable fits were obtained.

The triplet state spectra in the present study fall into the strongly exchange coupled regime, and in this regime |J| does not influence the positions of transitions in the spectra (36). Likewise, simulations were not sensitive to the sign of J. Based on the observation that the signals were much weaker at 77 K than at 4 K and the implied (large ZFS) short inter-spin distances, the exchange coupling is likely ferromagnetic. An “operational” value of |J| of 40–50 cm−1 was used in the simulations. Given that the g tensor of the low-spin Co2+ is anisotropic and the inter-spin distances are short, there is a potential for anisotropic contributions from the exchange interaction (36, 37). Given the modest Δg of low-spin Co2+, complications from delocalized unpaired spins are likely more significant than anisotropic exchange in this system. The anisotropy has been treated exclusively as arising from the dipole-dipole interaction.

Analysis and Decomposition of the ZFS Tensor

Due to the delocalization of spin within the anhydroadenosyl radical, the size of the dz2 orbital of Co2+, and the proximity of these two paramagnetic centers, the commonly invoked point-dipole approximation (relating the ZFS to the distance between the spins) is not adequate for this system. To overcome the limitations of the point-dipole approximation, and to exploit the structural information implicit in the ZFS tensor, a multipoint model known as the point-charge model was used (37-39). In this model, fractional spins are assigned to individual atoms or orbital lobes. The resulting ensemble of fractional spins is treated by summing the multiple dipole-dipole interactions occurring between the two paramagnetic centers in order to generate the ZFS tensor (Equation 3):

| (3) |

In Equation 3, δij is the Kronecker delta, ρ1(m) and ρ2(n) are the spin densities of the mth and nth fractional spin of cob(II)alamin and the anhydroadenosyl radical, respectively, and r1(m) and r2(n) are the corresponding position vectors (39). The relative position of the two paramagnetic centers was obtained by minimizing (with the aid of a simulated annealing algorithm) the sum of the squared differences between the experimental ZFS tensor elements and those calculated with equation 3 (40, 41). The search for reasonable local minima was guided by including in the objective function penalties to avoid unfavorable van der Waals contacts (42).

| (4) |

In Equation 4, FD has the form:

where the sum includes the six independent ZFS tensor elements (defined by D, E and the Euler angles ς, η, and ξ). fvdw has the form:

where σij is the van der Waals collision diameter between the ith atom of the anhydroadenosyl radical and the jth atom of cob(II)alamin, and rij is the corresponding distance.

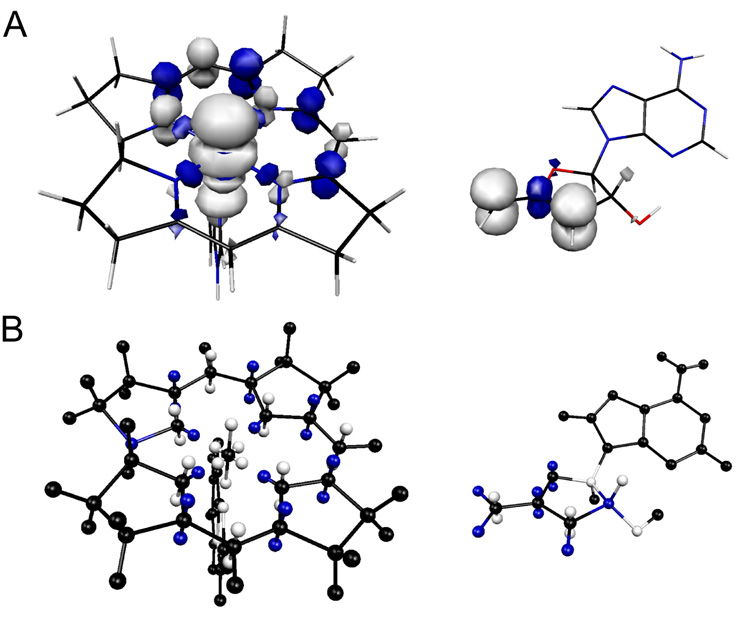

The spin densities used in equation 3 (see Supporting Information) were obtained from single-point energy calculations on the anhydroadenosyl radical and a truncated cob(II)alamin structure using Gaussian 98 (43). The geometries of the paramagnetic centers were optimized using Becke-style 3-Parameter Density Functional Theory (DFT) with the Lee-Yang-Parr correlation functional (B3LYP) and Pople’s polarized double-ζ 6-31G* basis set. Single-point calculations were performed on the optimized structures using the B3LYP hybrid functional in combination with the DFT-optimized valence triple-ζ basis set, TZVP. Isosurface plots of the spin densities of the anhydroadenosyl radical and the truncated cob(II)alamin are given in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Comparison of isosurface spin densities obtained from Gaussian98 calculations A) and the point charge models used in the calculation of the ZFS tensor of the cob(II)alamin-anhydroadenosyl radical.triplet system B). Positive spin density is in white, negative spin density in blue. In the point charge model, π-orbital lobes are positioned 0.7 Å above and below the molecular planes (37), σ-orbital lobes of the equatorial ring nitrogens are 0.5 Å from the nucleus along the Co-N bonds, and the dz2 orbital lobes are positioned 1.1 Å above and below and 0.6 Å within the plane of the corrin ring.

To better mimic the location of spin within the anhydroadenosyl radical, the spin density at each of the atoms in the π-system was divided in two and positioned at equal distances above and below the plane of the anhydroribosyl ring (38). The atoms in the π-system of the corrin ring of cob(II)alamin were treated in an analogous fashion. The spin of the corrin ring nitrogen atoms was split into an additional point corresponding to the σ-orbital coordinating the low-spin Co2+. The distribution of spin density within the dz2 orbital of Co2+, which can be expressed as a linear combination of d(z2− x2) and d(z2− y2) orbitals, was approximated by dividing the spin into six points, two equidistant above and below the plane, and four equidistant within the plane of the corrin ring. The point-charge models of the anhydroadenosyl radical and cob(II)alamin that resulted in the best-fit ZFS tensors are illustrated in Figure 1B.

The starting coordinates for the analysis were obtained by placing the geometry optimized cob(II)alamin fragment and the adenine ring of the anhydroadenosyl radical in the positions observed in the crystal structure of DDH complexed with adeninylpentylcobalamin (44). The position of the anhydroribosyl moiety was varied by rotation about the glycosidic bond and small overall rotations and translations of the anhydroadenosyl radical were performed to find the best match of the experimentally observed and calculated ZFS tensors in the global minimization. The structure corresponding to the minimum in the analysis is not necessarily unique in its ability to reproduce the ZFS tensor. However, it represents the structure that best reproduces the ZFS tensor and while minimizing changes in the geometry from that expected from the crystallographic data (44).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

EPR with anAdoCbl as Coenzyme

EPR spectra of DDH with anAdoCbl as coenzyme in the presence or absence of saturating 1,2-propanediol are shown in Figure 2 and 3, respectively. These EPR spectra bear a resemblance to the strongly-coupled triplet spectra detected in the AdoCbl-dependent enzymes ribonucleotide reductase (45), glutamate mutase (46), and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (47–49), in that the signals are centered at g-values midway between that of low-spin Co2+ and typical organic radicals and contain 59Co-hyperfine splittings that are contracted from that observed in magnetically isolated cob(II)alamin (23, 36). However, the width of the EPR spectra in Figure 2 and 3 are much greater than any of the aforementioned triplet spectra, indicating that the distance separating the two paramagnetic centers comprising the spin triplets in the present case is much smaller, resulting in a larger ZFS. The percentage of active sites hosting the triplet was determined from double integrations to be ~70% in both cases. This value is consistent with the extent of Co-C bond cleavage from similar samples estimated from UV-Vis spectroscopy after the same time period of incubation (28).

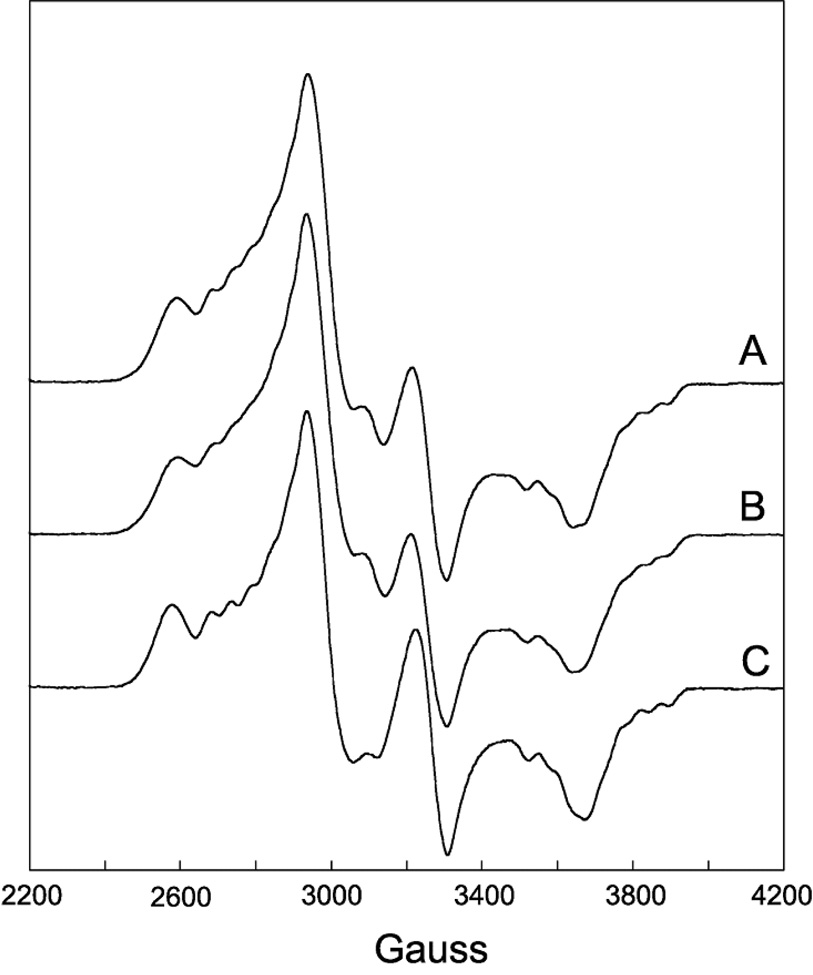

Figure 2.

EPR spectra of DDH with anAdoCbl as coenzyme in the presence of (R,S)-1,2-propanediol. The samples were frozen in cold isopentane 10 min after mixing within an anaerobic chamber. (A) Unlabeled coenzyme. (B) [13C5-ribosyl]-anAdoCbl. (C) anAdoCbl and (R,S)-1,2-[2H6]propanediol. Deuterium labeling at C5′ of the coenzyme occurs upon reaction with substrate. Experimental conditions: temperature, 4.5 K; modulation amplitude, 12 G; microwave power 0.2 mW; spectrometer frequency, 9.233 GHz (g=2.0 at 3,299 G). All spectra are an average of four 8 min scans.

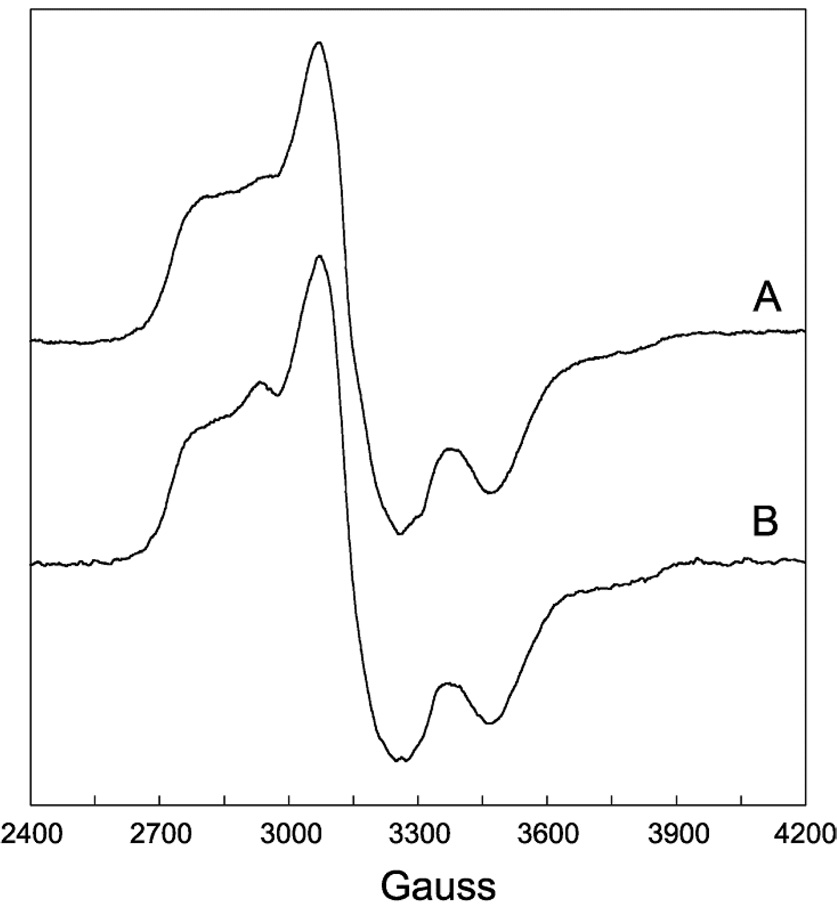

Figure 3.

EPR spectra of DDH with anAdoCbl as coenzyme in the absence of substrate. The samples were frozen in cold isopentane ~1 min after mixing within an anaerobic chamber. (A) Unlabeled coenzyme. (B) [13C5-ribosyl]-anAdoCbl. Experimental conditions: temperature, 4.5 K; modulation amplitude, 12 G; microwave power 0.2 mW; spectrometer frequency, 9.233 GHz. Both spectra are an average of four 8 min scans.

To establish the identity of the radical species spin-coupled to cob(II)alamin, EPR spectra were acquired with isotopically labeled coenzyme or substrate. Introduction of 13C (I = 1/2) at each position of the anhydroribosyl moiety of anAdoCbl ([13C5-ribosyl]-anAdoCbl) leads to inhomogeneous broadening of the EPR signals both in the presence and absence of substrate (Figure 2B and 3B, respectively). Only modest 13C-induced broadening effects are observed due to the large overall width of the EPR spectra and the hyperfine splitting contraction characteristic of strongly coupled triplet spin systems. The EPR spectrum obtained with unlabeled anAdoCbl and (R,S)-1,2-[2H6]propanediol is given in Figure 2C. A subtle line narrowing effect is observed due to incorporation of 2H into the 5′-position of the coenzyme. Both these effects are more readily visible in the half-field (ΔMS = 2) transitions wherein the intrinsic line widths are narrower (Figure 4 and Figure 5). The responses of the line widths to the magnetic isotope substitutions demonstrate that the anhydroadenosyl radical is the other half of the triplet spin system both in the presence and absence of substrate.

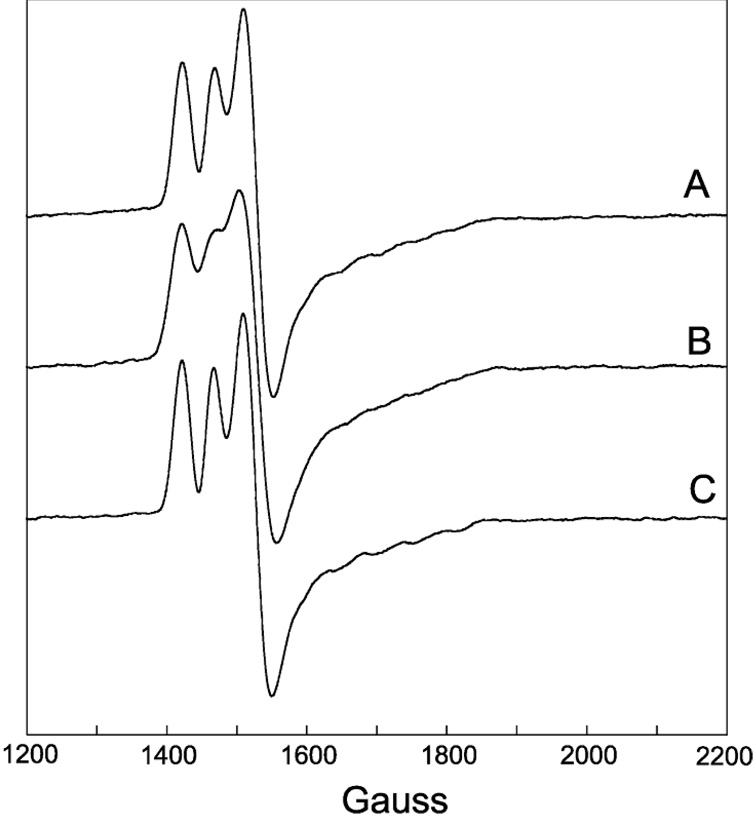

Figure 4.

EPR spectra of the half-field (ΔMS = 2) transition for the same samples as described in Figure 2. Experimental conditions: temperature, 4.5 K; modulation amplitude, 12 G; microwave power 2 mW; spectrometer frequency, 9.233 GHz. All spectra are an average of four 8 min scans.

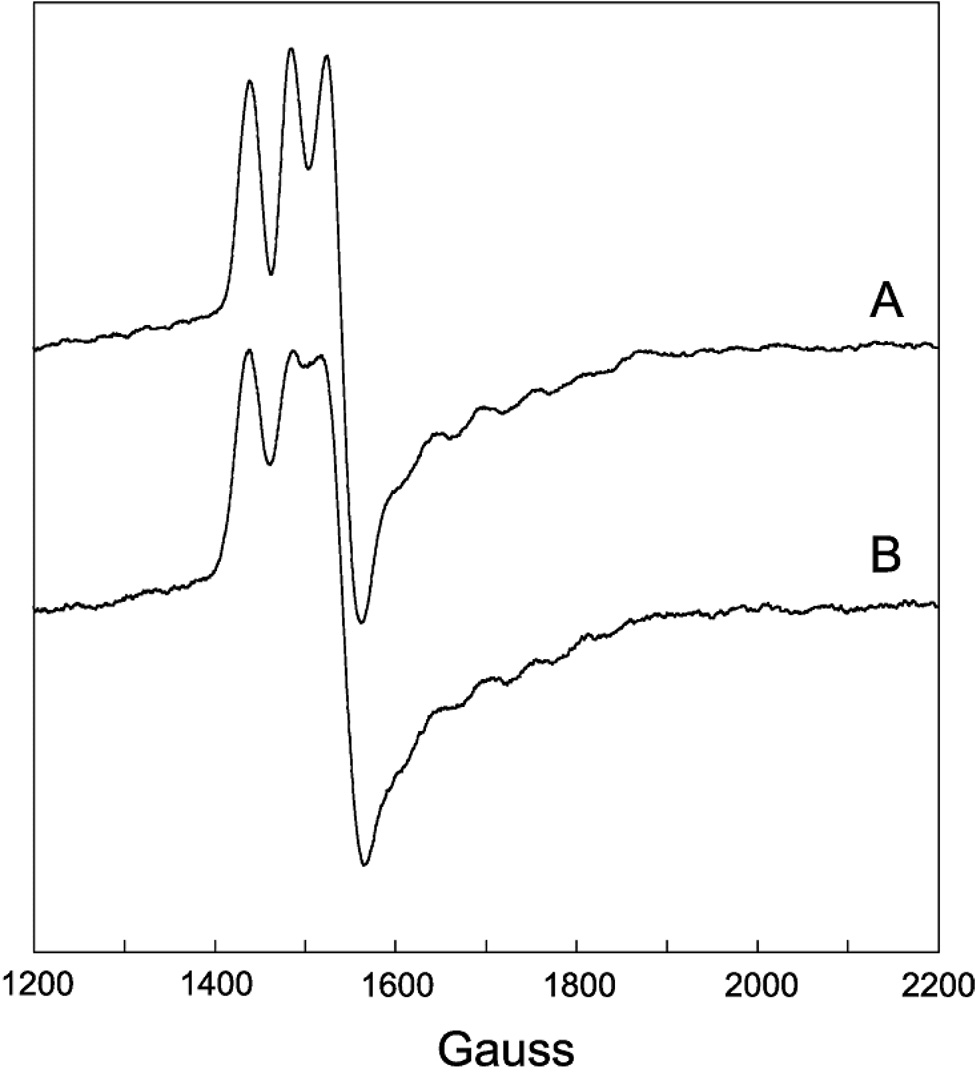

Figure 5.

EPR spectra of a half-field (ΔMS = 2) transition for the same samples as described in Figure 3. Experimental conditions: temperature, 4.5 K; modulation amplitude, 12 G; microwave power 2 mW; spectrometer frequency, 9.233 GHz. All spectra are an average of four 8 min scans.

A weakly allowed half-field (ΔMS = 2) transition is a spectroscopic signature of strongly-coupled triplet spin systems (35, 50). Such transitions are observed in the EPR spectra of DDH with anAdoCbl, both in the presence and absence of substrate (Figure 4 and 5, respectively). Incubation of DDH with [13C5-ribosyl]-anAdoCbl (Figure 4B and 5B) or unlabeled anAdoCbl and (R,S)1,2-[2H6]propanediol (Figure 4C) cause line width effects in the half-field transitions analogous to those seen in the ΔMS = 1 portion of the EPR spectra.

Analysis of the EPR Spectra

Spectral simulations were performed to better understand the complicated EPR spectra of DDH with anAdoCbl as coenzyme. The parameters used in the simulations are summarized in Table 1. Comparisons of the simulated and resolution enhanced experimental EPR spectra in the presence and absence of (R,S)-1,2-propanediol, are shown in Figure 6 and 7, respectively. The g-values used in the simulations were gx = 2.30, gy = 2.21, and gz = 2.00 for Co2+ and giso = 2.00 for the anhydroadenosyl radical, which are typical for cob(II)alamin and organic radicals (23, 36, 49). The only hyperfine interaction included in the spectral simulations was that derived from 59Co (I = 7/2; Ax = 15 G, Ay = 5 G, Az = 113 G); all other hyperfine interactions contribute only to the line widths of the signals in EPR spectra.

Table 1.

Parameters used in the simulation of the EPR spectra of DDH with anAdoCbl in the presence and absence of (R,S)-1,2-propanediol.

| (R,S)-1,2-propanediol | Present | Absent |

|---|---|---|

| Co2+ g-values | gx = 2.30, gy = 2.21, gz= 2.00 | gx = 2.30, gy = 2.21, gz = 2.00 |

| Radical g-values | giso = 2.00 | giso = 2.00 |

| 59Co-hyperfine tensor | Ax = 15G, Ay = 5G, Az = 113G | Ax = 15G, Ay = 5G, Az = 113G |

| ZFS parameters | D = −522G, E = −91G | D = −335G, E = −87G |

| Euler angles | ζ = 75°, η = 10°, ξ = 54° | ζ = 71°, η = −10°, ξ = 90° |

| Exchange coupling | |J| ~ 40–50 cm−1 | |J| ~ 40–50 cm−1 |

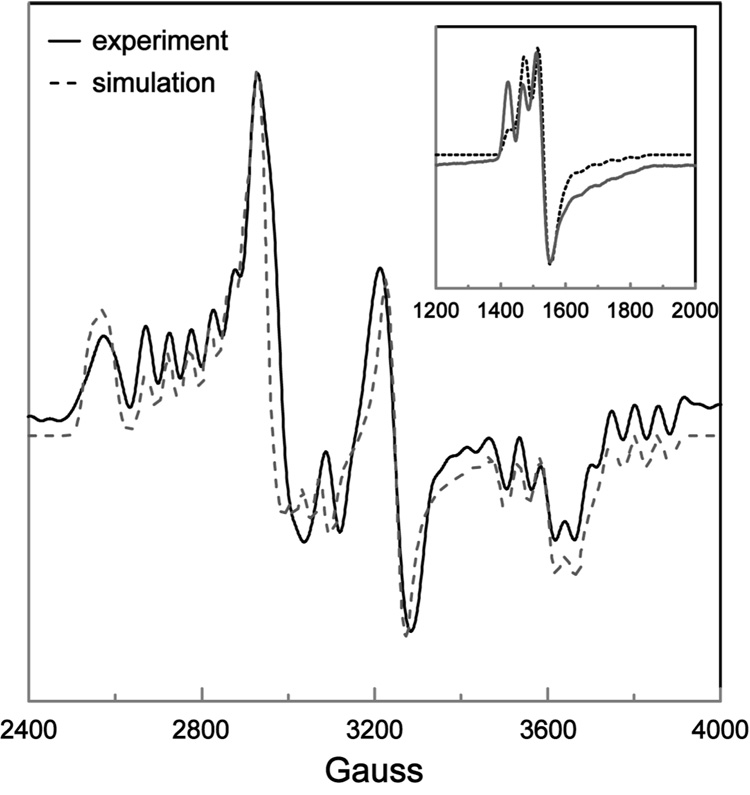

Figure 6.

Comparison of the simulated and resolution enhanced experimental EPR spectrum of DDH with anAdoCbl in the presence of saturating (R,S)-1,2-propanediol. The ZFS parameters were D = −522 G and E = −91 G, with Euler angles ζ = 75°, η = 10°, and ξ = 54°. The g-values for cob(II)alamin and the anhydroadenosyl radical gx = 2.30, gy = 2.21, gz = 2.00 and giso = 2.00, respectively. The 59Co-hyperfine splittings were Ax = 15 G, Ay = 5 G and Az = 113 G. Lorentzian line shapes were used with isotropic line widths of 15 G. The inset compares the simulated and experimental EPR spectrum of the half-field transition, obtained with the same parameter set.

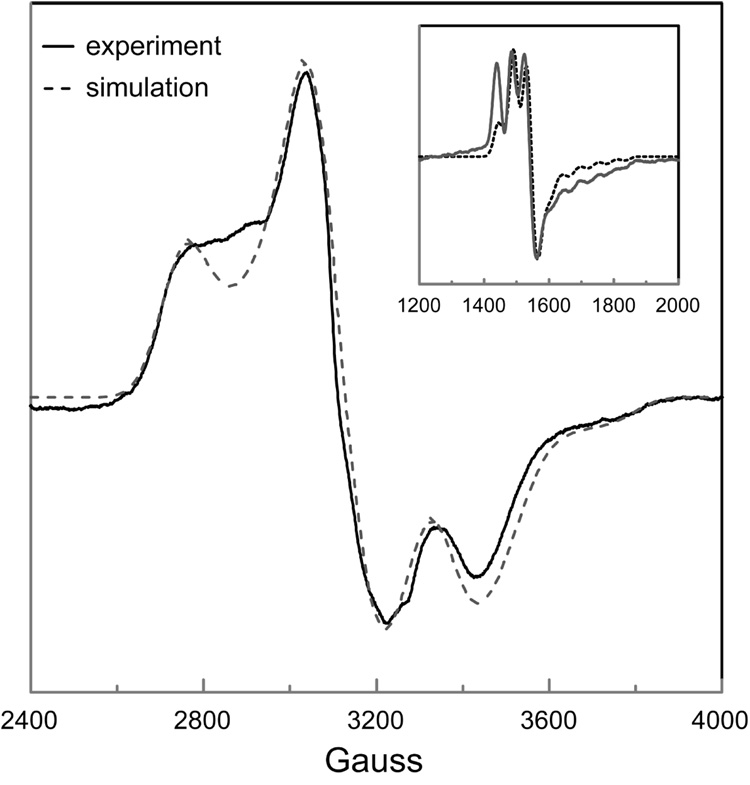

Figure 7.

Comparison of the simulated and experimental EPR spectrum of DDH with anAdoCbl in the absence of (R,S)-1,2-propanediol. The ZFS parameters were D = −335 G and E = −87 G, with Euler angles ζ = 71°, η = −10°, and ξ = 90°. The g-values for cob(II)alamin and the anhydroadenosyl radical gx = 2.30, gy = 2.21, gz = 2.00 and giso = 2.00, respectively. The 59Co-hyperfine splittings were Ax = 15 G, Ay = 5 G and Az = 113 G. Lorentzian line shapes were used with isotropic line widths of 55 G. The inset compares the simulated and experimental EPR spectrum of the half-field transition, obtained with the same parameter set.

The ZFS interactions between cob(II)alamin and the anhydroadenosyl radical are highly rhombic both in the presence (D = −522 G, E = −91 G, E/D = 0.17) and absence (D = −335 G, E = −87 G, E/D = 0.26) of substrate, indicating that the electron spin density within the paramagnetic centers are highly delocalized, making the commonly invoked point dipole approximation invalid (39). Euler rotations were required to align the principal axis systems of the ZFS tensors with that of the g-tensor (or equivalently, the hyperfine splitting tensor) of Co2+, both in the presence (ζ = 75°, η = 10°, ξ = 54°) and absence (ζ = 71°, η = −10°, ξ = 90°) of substrate. This non-collinearity of tensor axes has a significant influence on the appearance of EPR spectra of strongly-coupled triplet systems in that it shifts the apparent g-values of turning points and transfers hyperfine splittings between turning points (3, 39).

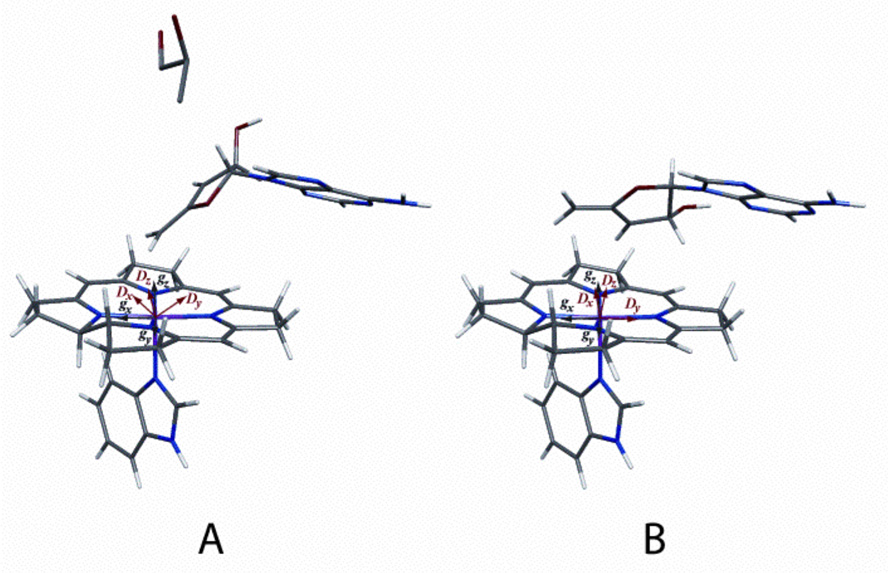

Figure 8 shows the geometries derived from the decomposition of the ZFS tensors obtained from the simulations of the EPR spectra of DDH with anAdoCbl in the presence (Figure 8A) and absence (Figure 8B) of (R,S)-1,2-propanediol, respectively. A comparison of these two structures reveals that upon substrate binding, there is only a slight perturbation in the position of the adenine ring (RMSD 0.53 Å). The position of the adenine ring of the anhydroadenosyl radical in both the presence and absence of substrate is very similar to that observed in the crystal structure of DDH complexed with adeninylpentylcobalamin (RMSD 0.67 Å and 0.84 Å, respectively3) (44). In addition, upon substrate binding, there is a rotation of the anhydroribosyl moiety by ~60° about the glycosidic bond, which postions the 5′-carbon of the anhydroadenosyl radical closer to Co2+ (3.5 Å vs. 4.1 Å). This structure is consistent with the larger ZFS observed in the EPR spectrum when substrate is present (D = −522 G vs. D = −335 G). The basis for the greater rhombicity of the ZFS in the absence of substrate (E/D = 0.26 vs. E/D = 0.17) is also evident from a comparison of the two structures. The vector between C-5′ and C-3′ of the anhydroadenosyl radical (the two atoms with the greatest spin density in the radical) is very nearly perpendicular to the inter-spin vector with cob(II)alamin in the absence of substrate. In the substrate bound structure, the C-5′-C-3′ vector and the inter-spin vector are closer to being parallel. In the case of electron delocalization about two points, the rhombicity in the ZFS is maximal when these two vectors are orthogonal and vanishes when they are collinear (39).

Figure 8.

Model of cob(II)alamin and the anhydroadenosyl radical in the active site of DDH in the presence A) and absence B) of (R,S)-1,2-propanediol. A) The distance between C5′ and Co2+ is 3.5 Å. The position of the adenine ring is very similar to that observed in the crystal structure of the DDH- adeninylpentylcobalamin complex (RMSD, 0.67 Å) (44). B) The distance between C5′ and Co2+ is 4.1 Å. The position of the adenine ring is perturbed slightly (RMSD, 0.53 Å) and the anhydroribosyl moiety rotates ~60° relative to their positions when substrate is bound. The positions of the g and D axes are labeled in the corin ring.

Conclusions

Rotation around the glycosidic bond of the anhydroadenosyl radical would position C5′ of the radical in close proximity to C1 of the substrate. Such a rotation mechanism for propagation of the radical was proposed earlier by Toraya and co-workers based on the crystal structure of the enzyme from K. oxytoca (44). The two positions of the anhydroadenosyl radical observed in the presence and absence of substrate in the current study provides direct evidence in support of this rotation mechanism.

The enzyme may be able to cleave the Co-C5′ bond of AdoCbl without substrate present, but due to the instability of the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical, the equilibrium for the bond homolysis reaction would favor the intact coenzyme. This scenario is supported by the results of this study, in which the equilibrium for Co-C5′ bond homolysis of anAdoCbl is shifted towards formation of the cleavage products, due to the stability of the resulting allylic radical. Observation of the anhydroadenosyl radical supports the mechanism of DDH, where a transient 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical intermediate functions as the direct hydrogen atom abstractor from substrate. In the case of the anAdoCbl, the cofactor derived radical resides very close to its cob(II)alamin partner in the absence and presence of the substrate.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1S showing numbering of atoms used in the DFT calculation; Tables 1S and 2S showing DFT calculated spin densities and/or hyperfine splitting constants; discussion of agreement between calculated and experimentally observed hyperfine splitting constants. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AdoCbl, 5′-deoxyadenosylcobalamin; anAdoCbl, 5′-deoxy-3′,4′-anhydroadenosylcobalamin; anATP, 3′,4′-anhydroadenosine triphosphate; anhydroadenosyl radical, 5′-deoxy-3′,4′-anhydroadenosyl radical; BDE, bond dissociation energy; DMB, dimethylbenzimidazole; DDH, diol dehydrase; EPR, electron paramagnetic resonance; ENDOR, electron nuclear double resonance; SAM, S-adenosyl-L-methionine; ZFS, zero-field splitting; RMSD, root-mean-square deviation.

The ZFS tensor used in the spin Hamiltonian has the form, D = g1·D′·g2, where D′ is the ZFS tensor expressed in the principal axis system of g1 divided by the square of the free electron g-value. Using this formalism, contributions to the rhombicity of the ZFS from gxy-anisotropy are considered directly and separately from the contributions due to electron spin delocalization.

The orientation of the adenine ring has little effect on the calculated ZFS tensor. However, its position is constrained by the orientation of the glycosidic bond. The dihedral angle used to position the adenine ring was chosen so as to minimize the RMSD.

This research was supported by NIH grants GM35752 (G.H.R.) and DK28607 (P.A.F). S.O.M. was supported in part by NIH Predoctoral Training Grant T32 GM08293 in Molecular Biophysics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banerjee R. Radical peregrinations catalyzed by coenzyme B12-dependent enzymes. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6191–6198. doi: 10.1021/bi0104423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marsh ENG, Drennan CL. Adenosylcobalamin-dependent isomerases: new insights into structure and mechanism. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:499–505. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00238-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed GH. Radical mechanisms in adenosylcobalamin-dependent enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finke RG. Thermolysis of adenosylcobalamin: A product, kinetic, and Co-C5′sociation energy study. Inorg. Chem. 1984;23:3041–3043. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padmakumar R, Padmakumar R, Banerjee R. Evidence that cobalt-carbon bond homolysis is coupled to hydrogen atom abstraction from substrate in methylmalonyl-CoA mutase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3713–3718. doi: 10.1021/bi962503g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsh ENG, Ballou DP. Coupling of cobalt-carbon bond homolysis and hydrogen atom abstraction in adenosylcobalamin-dependent glutamate mutase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11864–11872. doi: 10.1021/bi980512e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandarian V, Reed GH. Isotope effects in the transient phases of the reaction catalyzed by ethanolamine ammonia-lyase: Determination of the number of exchangeable hydrogens in the enzyme-cofactor complex. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12069–12075. doi: 10.1021/bi001014k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toraya T. Radical catalysis in coenzyme B12-dependent isomerization (eliminating) reactions. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2095–2128. doi: 10.1021/cr020428b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booker S, Licht S, Broderick J, Stubbe J. Coenzyme B12-dependent ribonucleotide reductase: Evidence for the participation of five cysteine residues in ribonucleotide reduction. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12676–12685. doi: 10.1021/bi00208a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen D, Abend A, Stubbe J, Frey PA. Epimerization at carbon-5′-[5′-2H] adenosylcobalamin by ribonucleoside triphosphate reductase: Cysteine 408-independent cleavage of the Co-C5′ bond. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4578–4584. doi: 10.1021/bi030018x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toraya T. Diol dehydratase and glycerol dehydratase. In: Banerjee, editor. Chemistry and Biochemistry of B12. NY: Wiley-Interscience; 1999. pp. 783–809. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walling C, Johnson RA. Fenton's reagent. Rearrangements during glycol oxidations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:2405–2407. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golding BT, Buckel W. Corrin-dependent reactions. In: Sinnott ML, editor. Comprehensive Biological Catalysis. London: Academic Press; 1997. pp. 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith DM, Golding BT, Radom L. Understanding the mechanism of B12-dependent diol dehydratase: A synergistic retro-push-pull proposal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:1664–1675. doi: 10.1021/ja001454z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamachi T, Toraya T, Yoshizawa K. Catalytic roles of active-site amino acid residues of coenzyme B12-dependent diol dehyratase: protonation state of histidine and pull effect of glutamate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:16207–16216. doi: 10.1021/ja045572o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibata N, Masuda J, Tobimatsu T, Toraya T, Suto K, Morimoto Y, Yasuoka N. A new mode of B12 binding and the direct participation of a potassium ion in enzyme catalysis: X-ray structure of diol dehydratase. Structure Fold. Des. 1999:997–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toraya T, Yoshizawa K, Eda M, Yamabe T. Direct participation of potassium ion in the catalysis of coenzyme B(12)-dependent diol dehydratase. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 1999;126:650–654. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz P, LoBrutto R, Reed GH, Frey PA. Suicide Inactivation of Dioldehydrase by 2-Chloroacetaldehyde: Formation of the cis-ethanesemidione radical, and the role of a Monovalent Cation. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2003;86:3764–3775. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawata M, Kinoshita K, Takahashi S, Ogura K, Komoto N, Yamanishi M, Tobimatsu T, Toraya T. Survey of catalytic residues and essential roles of glutamate-α 170 and aspartate-α 335 in coenzyme B12-dependent diol dehyratase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:18327–18334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601910200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Retey J, Umani-Ronchi A, Seibl J, Arigoni D. On the mechanism of the propanediol dehydrase reaction. Experientia. 1966;22:502–503. doi: 10.1007/BF01898652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finlay TH, Valinsky J, Mildvan AS, Abeles RH. Electron spin resonance studies with dioldehydrase: evidence for radical intermediates in reactions catalyzed by coenzyme B12. J. Biol. Chem. 1973;248:1285–1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valinsky JE, Abeles RH, Fee JA. Electron spin resonance studies on diol dehydrase III. Rapid kinetic studies on the rate of formation of radicals in the reaction with propanediol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:4709–4710. doi: 10.1021/ja00821a077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilbrow JR. EPR of B12-dependent enzyme reactions and related systems, in B12. In: Dolphin D, editor. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1982. pp. 431–463. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valinsky JE, Abeles RH, Mildvan AS. Electron spin resonance studies of diol dehydrase II. The hyperfine structure of proposed radical intermediates derived from isotopic substitution in 2-chloroacetaldehyde. J. Biol. Chem. 1974;249:2751–2755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abend A, Bandarian V, Reed GH, Frey PA. Identification of cis-ethanesemidione as the organic radical derived from glycolaldehyde in the suicide inactivation of dioldehydrase and of ethanolamine ammonia-lyase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6250–6257. doi: 10.1021/bi992963k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamanishi M, Hirofumi I, Murakami Y, Toraya T. Identification of the 1,2-propanediol-1-yl radical as an intermediate in adenosylcobalamin-dependent diol dehydratase reaction. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2113–2118. doi: 10.1021/bi0481850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnusson OT, Frey PA. Synthesis and characterization of 3′,4′-anhydroadenosylcobalamin: A coenzyme B12 analogue with unusual properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:8807–8813. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magnusson OT, Frey PA. Interactions of diol dehydrase and 3′,4′-anhydroadenosylcobalamin: Suicide inactivation by electron transfer. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1695–1702. doi: 10.1021/bi011947w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magnusson OT, Reed GH, Frey PA. Characterization of an allylic analogue of the 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical: An intermediate in the reaction of lysine 2,3-aminomutase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7773–7782. doi: 10.1021/bi0104569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poznanskaja AA, Tanizawa K, Soda K, Toraya T, Fukui S. Coenzyme B12-dependent diol dehydrase: purification, subunit heterogeneity, and reversible association. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1979;194:379–386. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90630-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kauppinen JK, Moffaatt DJ, Mantsch HH, Cameron DG. Fourier self-deconvolution: A method for resolving intrinsically overlapped bands. Appl. Spectrosc. 1981;35:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Latwesen DG, Poe M, Leigh JS, Reed GH. Electron paramagnetic resonance studies of a ras p21-MnIIGDP complex in solution. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4946–4950. doi: 10.1021/bi00136a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein H, Poole CP, Jr, Safko JL. Classical Mechanics. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Addison Wesley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandarian V, Reed GH. Hydrazine cation radical in the active site of ethanolamine ammonia-lyase: Mechanism-based inactivation by hydroxyethylhydrazine. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12394–12402. doi: 10.1021/bi990620g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wertz JE, Bolton JR. Electron Spin Resonance. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerfen GJ. EPR spectroscopy of B12-dependent enzymes. In: Banerjee R, editor. Chemistry and Biochemistry of B12. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1999. pp. 165–195. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bencini A, Gatteschi D. EPR of Exchange Coupled Systems. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukai K, Sogabe A. ESR studies of radical pairs of galvinoxyl radical in corresponding phenol matrix. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:598–601. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mansoorabadi SO, Reed GH. Effects of electron spin delocalization and non-collinearity of interaction terms in EPR triplet powder patterns. In: Telser J, editor. Paramagnetic resonance of metallobiomolecules. Washington, D. C.: American Chemical Society; 2003. pp. 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goffe WL, Ferrier GD, Rogers J. Global optimization of statistical functions with simulated annealing. J. Econometrics. 1994;60:65–100. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Press WH, Flannery BP, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT. Numerical Recipes. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leach AR. Molecular Modeling Principles and Applications. Second ed. London: Prentice Hall; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Zakrzewski VG, Montgomery JJA, Stratmann RE, Burant JC, Dapprich S, Millam JM, Daniels AD, Kudin KN, Strain MC, Farkas O, Tomasi J, Barone V, Cossi M, Cammi R, Mennucci B, Pomelli C, Adamo C, Clifford S, Ochterski J, Petersson GA, Ayala PY, Cui Q, Morokuma K, Malick DK, Rabuck AD, Raghavachari K, Foresman JB, Cioslowski J, Ortiz JV, Baboul AG, Stefanov BB, Liu G, Liashenko A, Piskorz P, Komaromi I, Gomperts R, Martin RL, Fox DJ, Keith T, Al-Laham MA, Peng CY, Nanayakkara A, Gonzalez C, Challacombe M, Gill PMW, Johnson B, Chen W, Wong MW, Andres JL, Head-Gordon M, Replogle ES, Pople JA. Gaussian 98. Pittsburg: Gaussian, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masuda J, Shibata N, Morimoto Y, Toraya T, Yasuoka N. How a protein generates a catalytic radical from coenzyme B12: X-ray structure of a dioldehydratase-adeninylpentylcobalamin complex. Structure Fold Des. 2000;8:775–788. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerfen GJ, Licht S, Willems JP, Hoffman BM, Stubbe J. Electron paramagnetic resonance investigations of a kinetically competent intermediate formed in ribonucleotide reduction - evidence for thiyl radical-cob(II)alamin interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8192–8197. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bothe H, Darley DJ, Albracht SP, Gerfen GJ, Golding BT, Buckel W. Identification of the 4-glutamyl radical as an intermediate in the carbon skeleton rearrangement catalyzed by coenzyme B12-dependent glutamate mutase from Clostridium cochlearium. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4105–4113. doi: 10.1021/bi971393q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Y, Abend A, Kunz M, Such P, Retey J. Electron paramagnetic resonance studies of the methylmalonyl-CoA mutase reaction. Evidence for radical intermediates using natural and artificial substrates as well as the competitive inhibitor 3-carboxypropyl-CoA. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;225:891–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.0891b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Padmakumar R, Banerjee R. Evidence from electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy of the participation of radical intermediates in the reaction catalyzed by methylmalonyl-coenzyme A mutase. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:9295–9300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mansoorabadi SO, Padmakumar R, Fazliddinova N, Vlasie M, Banerjee R, Reed GH. Characterization of a succinyl-CoA radical-cob(II)alamin spin triplet intermediate in the reaction catalyzed by adenosylcobalamin-dependent methylmalonyl-CoA mutase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:3153–3158. doi: 10.1021/bi0482102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eaton GR, Eaton SS. Resolved electron-electron spin-spin splittings in EPR spectra. Biol. Magn. Reson. 1989;8:650. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure 1S showing numbering of atoms used in the DFT calculation; Tables 1S and 2S showing DFT calculated spin densities and/or hyperfine splitting constants; discussion of agreement between calculated and experimentally observed hyperfine splitting constants. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.