Abstract

Thiobenzamide (TB) is hepatotoxic in rats causing centrolobular necrosis, steatosis, cholestasis and hyperbilirubinemia. It serves as a model compound for a number of thiocarbonyl compounds that undergo oxidative bioactivation to chemically reactive metabolites. The hepatotoxicity of TB is strongly dependent on the electronic character of substituents in the meta- and para- positions, with Hammett rho values ranging from −4 to −2. On the other hand ortho substituents which hinder nucleophilic addition to the benzylic carbon of S-oxidized TB metabolites abrogate the toxicity and protein covalent binding of TB. This strong linkage between the chemistry of TB and its metabolites and their toxicity suggests that this model is a good one for probing the overall mechanism of chemically-induced biological responses. While investigating the protein covalent binding of TB metabolites we noticed an unusually large amount of radioactivity associated with the lipid fraction of rat liver microsomes. Thin layer chromatography showed that most of the radioactivity was contained in a single spot more polar than the neutral lipids but less polar than the phospholipid fractions. Mass spectral analyses aided by the use of synthetic standards identified the material as N-benzimidoyl derivatives of typical microsomal phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) lipids. Quantitative analysis indicated that up to 25% of total microsomal PE became modified within 5 h after a hepatotoxic dose of TB. Further studies will be required to determine the contribution of lipid modification to the hepatotoxicity of thiobenzamide.

Introduction

Thiocarbonyl (>C=S) compounds exhibit a broad range of biological activities, often toxicological but sometimes useful. For example, thiourea (TU), phenylthiourea (PTU) and α-naphthylthiourea (ANTU) have long been known for their acute pneumotoxicity to rats, and ANTU was once widely used as a rodenticide (1, 2). In contrast to the pneumotoxic thioureas, thioamide derivatives such as thioacetamide (TA) (3–5) and thiobenzamide (TB, 1) (6–8) are hepatotoxic in rats. Both cause centrilobular necrosis along with a profound hyperbilirubinemia. Another thioamide, ethionamide (ETH, 2-ethyl-isothionicotinamide) is used clinically as a second line anti-tubercular drug which disrupts mycobacterial cell wall biosynthesis (9–11). A common theme in the biological activity of the above-mentioned compounds is that they all require S-oxidative biotransformation in order to elicit their biological effect. The primary metabolic fate of most thiocarbonyl compounds is to undergo “oxidative desulfurization” to the corresponding carbonyl (>C=O) compound (12). The fact that the latter generally possess none of the toxic properties of the parent sulfur compound suggests that S-oxidized intermediates en route from C=S to C=O are probably important in their toxicity.

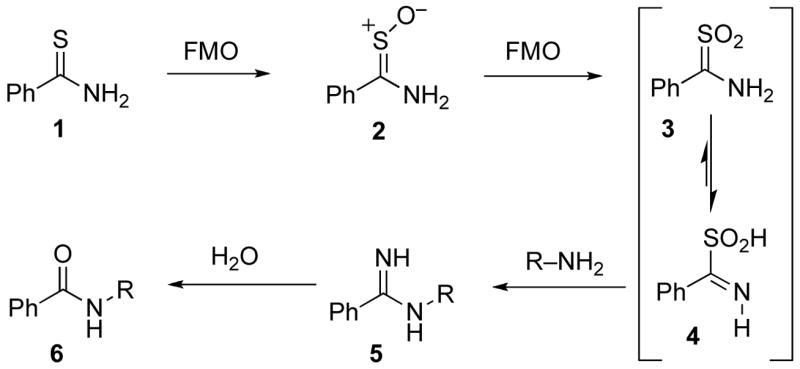

Many thiourea and thioamide compounds are excellent substrates for flavin-containing mono-oxygenase (FMO) enzymes in rat liver (13, 14), but cytochrome P450 2E1 (15) and possibly other P450s as well (16), can also oxidize thiocarbonyl compounds. Their oxidation is governed largely by the intrinsic chemistry of the thiocarbonyl group and its soft, highly polarizable and easily oxidized sulfur atom (Scheme 1) (12). Thioamide S-oxides such as 2 were first prepared and characterized by Walter in the 1950s (17), and in many cases they are relatively stable structures. S-Oxide metabolites of TA, TB and ETH have been isolated, but their further S-oxidation generates S,S-dioxides (e.g., 3) that are extremely reactive and not isolable as such. In solution they behave as acylating (imidoylating) agents. This is best rationalized by their tautomeric iminosulfinic acid forms such as 4, in which the oxidized sulfur moiety acts as a leaving group (18). For thioureas the situation is similar, except that three successive oxidations are required to generate an “acylating” type of metabolite (i.e., an aminoiminosulfonic acid). Both iminosulfinic acids and aminoiminosulfonic acids are highly reactive toward amine nucleophiles, and find use in the synthesis of amidines and guanidines, respectively (19).

Scheme 1.

Metabolic activation of thiobenzamide toward amine nucleophiles.

The toxicity of numerous small molecules has been strongly correlated with, and generally attributed to, the protein covalent binding of chemically reactive metabolites formed by oxidative biotransformation of a relatively inert parent (20–22). This pattern holds true for thioureas (23, 24) and thioamides (25–27) as well. In the case of TB, three lines of evidence implicate a role for S-oxidation as a critical bioactivation event. First, chemically synthesized thiobenzamide S-oxide (2) is a more potent, faster acting hepatotoxicant than TB (7). Second, consistent with a putative requirement for S-oxidative bioactivation, the toxicity of thiobenzamide is markedly increased or decreased, respectively, by electron donating or withdrawing substituents in the meta or para position (Hammett rho values range from −4 to −2) (6–8). Third, ortho substitution abrogates their toxicity (6), their covalent binding in vitro (25), and their chemical acylating activity (18). This is purely a steric effect of the ortho substituent impeding nucleophilic attack on the sp2 benzylic carbon and formation of the tetrahedral intermediate required for benzimidoyl transfer. Although ethionamide has an unhindered thioamide group, its relative lack of toxicity can probably be attributed to the pyridine ring, which has the electron withdrawing ability of a p-nitrophenyl group.

More recently the connection between the acute toxicity of many small molecules and the chemical reactivity of their biotransformation products has stimulated considerable interest in the identification of their cellular targets, particularly proteins, and the structural elucidation of the covalent adducts formed (28–32). In an earlier study of bromobenzene activation and covalent binding in vivo we used two dimensional gel electrophoresis (2DGE) to analyze microsomal proteins from the livers of rats treated with 14C-bromobenzene (33). In that work we observed a large streak of radioactive material in the low-pI, low-molecular weight (MW) region of the gel. Surprisingly, this material did not take up Coomassie stain like typical proteins, and no such material was present in 2D gels of cytosolic proteins from the same animals. Although the appearance of this radioactive but apparently non-proteinaceous material on the gel was unexpected, we did not pursue the observation at that time. In the present study we originally set out to identify hepatic protein targets for thiobenzamide. Using a similar approach of 2DGE coupled to mass spectrometry we again observed a large streak of non-proteinaceous radioactive material in the low-pI, low-MW region of the gel from the microsomal protein sample, but not in the gel from the cytosolic proteins. In this manuscript we report the isolation and characterization of this unexpected material as N-benzimidoyl derivatives of microsomal phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) lipids, and comment on the toxicological relevance of the formation of these adducts.

Material and Methods

Materials

Thiobenzamide, bromobenzene, Lawesson’s reagent and methyl benzimidate hydrochloride were purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI). Benzoic acid-d5 (99.6 atom-%) was obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA). 1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DPPE) was obtained from Avanti Polar lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). [14C] Bromobenzene (5.17 Ci/mol) was available from previous work in our laboratory (34, 35). [7-14C] Benzoic acid (57 Ci/mol) was obtained from Moravek (Brea, CA). All other chemicals and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers at the highest purity available.

Chromatography and Autoradiography

Flash chromatography was performed using Selecto Scientific silica gel (63-200 mesh). Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Analtech (Newark, DE) 0.25mm silica gel GF plates eluted with CHCl3/MeOH/NH3H2O (80/20/3 v/v/v). Lipids were visualized by spraying the plate with 10% CuSO4 solution in 10% H3PO4 followed by heating. Radioactivity on the TLC plate was detected by exposing it to a Molecular Dynamics phosphor screen (3 days at room temperature) and scanning the screen with a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX scanning unit. For preparative TLC, modified lipids were visualized by short-wavelength UV (254nm) and recovered by scraping the silica gel from the plate and eluting with CHCl3/MeOH (2:1). The eluate was filtered, dried under vacuum and reconstituted in CHCl3 for MS/MS analysis.

Thiobenzamide-d5

Benzoic acid-d5 (239 mg, 1.982 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of dry benzene in a 50 mL culture tube containing a magnetic stirring bar. Oxalyl chloride (0.25 mL, 2.86 mmol) was added and the tube was sealed with a teflon-lined screwcap. The bottom of the tube was immersed in an oil bath at 85 °C (so that the upper sides of the tube served as an air-cooled reflux condenser) and the contents were stirred and heated for 3 h. After cooling to room temperature, concentrated aqueous ammonia solution (1.5 mL, 23.6 mmol NH3) was added, whereupon a white precipitate formed. After stirring for 3 h the mixture was partitioned between water and ethyl acetate. The organic phase was dried and evaporated yielding 239 mg of benzamide-d5 (98%) as a white solid. The latter was combined with Lawesson’s reagent (36) (475 mg, 1.17 mmol) and dichloromethane (3 mL) and heated (2 h, 55 °C) in a culture tube as described above. After cooling in an ice bath, water was added and the product was extracted with ether and purified by flash chromatography eluting with dichloromethane. Yield: 244 mg of pale yellow solid (89% overall), confirmed by TLC and MS.

[14C]-Thiobenzamide

[7-14C]-Benzoic acid (12 mg, 0.097 mmol,10 mCi) was combined with 233 mg (1.83 mmol) of ordinary benzoic acid and converted to thiobenzamide as described above. Yield 144 mg (55% overall); specific activity 4.37 Ci/mol.

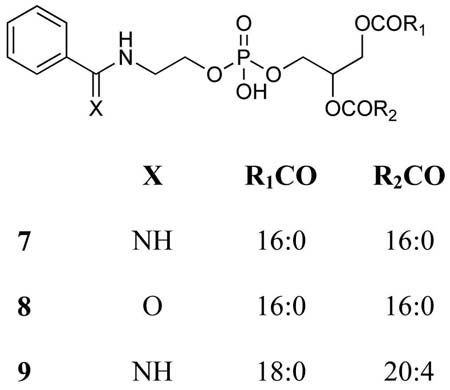

N-Benzimidoyl-(1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) (7)

To a mixture of methyl benzimidate hydrochloride (10.3 mg, 0.06 mmol) and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (21 mg, 0.03mmol) in ethanol (5.0 mL) was added triethylamine (6.06 mg, 0.06 mmol) in 1 mL ethanol. The resulting mixture was heated to reflux for 2 h, diluted with ethyl acetate (20 ml), washed with water (10 mL) and brine (10 mL) and the organic solution was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the residue was purified by column chromatography eluting with a 1:1 mixture of chloroform and methanol to give 18 mg (76%) of the title compound. TLC Rf 0.54 (80:20:3 CHCl3/MeOH/NH3H2O). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (6H, t), 1.25 (48H, m), 1.40 (4H, m), 2.26 (4H, t), 3.64 (2H, br), 3.90–4.10 (6H, br), 4.34 (1H, m), 5.20 (1H, s), 7.38–7.48 (3H, m), 7.85 (2H, d). HRMS, ESI: m/z found 795.5614 [M+H]+; 795.5652 calcd for C44H80N2O8P.

N-Benzoyl-(1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) (8)

A mixture of benzoic anhydride (3.4 mg, 0.015 mmol), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (10.5 mg, 0.015 mg) and triethylamine (3.03 mg, 0.03 mmol) in chloroform (2 mL) was stirred at room temperature overnight (37). The reaction mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate (20 ml) and washed with water (10 mL) and brine (10 mL). The organic solution was dried over anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under vacuum and the residue was purified by column chromatography eluting with a 1:1 mixture of chloroform and methanol to give 8.4 mg (70%) of the title compound. TLC Rf 0.54 (80:20:3 CHCl3/MeOH/NH3H2O). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.88 (6H, t), 1.25 (48H, m), 1.40 (4H, m), 2.13 (4H, br), 3.62 (2H, br), 3.86–3.98 (6H, m), 4.25 (1H, m), 5.20 (1H, s), 7.36 (2H, m), 7.83 (2H, m), 8.01 (1H, d). HRMS, ESI: m/z found 794.5319 [M-H]−; 794.5335 calcd for C44H77NO9P.

Treatment of Animals and Preparation of Cell Fractions

All animal husbandry protocols were in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication, Volume 25, 1996. http://grants1.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not96-208.html). Experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Commmittee of the University of Kansas. Ten male Sprague-Dawley rats (210–230 g, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were housed in a temperature and humidity controlled room with a 12 h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. After acclimating for at least 3 days, animals were given 3 daily ip injections of sodium phenobarbital (80 mg/kg) in 0.9% saline (1.0 mL/kg). After the third dose, food was withheld overnight and the next morning 4 rats were injected with [14C]thiobenzamide (0.86 mmol/kg, ip) in corn oil (2.5 mL/kg). The remaining six rats received [d0/d5]-thiobenzamide (1:1 mol/mol; 1.16 mmol TB/kg in 3.3 mL corn oil/kg, ip). (Note: Since thiobenzamide is not highly soluble in corn oil, it was first dissolved in a minimum volume of dichloromethane before adding the requisite amount of corn oil. The dichloromethane was then removed by rotary evaporation (or under a nitrogen stream at 45–50°) resulting in a homogeneous solution from which TB eventually started to crystallize. To prevent plugging of the needle, the corn oil solution was warmed gently to ca. 40–45° on a hotplate and used immediately for injection. The warmth of the solution caused no visible distress to the animals).

Five h after injection the animals were anesthetized by CO2 narcosis and killed by decapitation. Their livers were removed, rinsed with ice-cold 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 0.15 M KCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 0.1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (buffer A), minced with scissors and homogenized in buffer A (4 mL/g tissue). The homogenates were pooled and centrifuged at 11,000gavg for 20 min. The resulting pellet was discarded, and the supernatant was further centrifuged at 100,000gmax (60 min). The resulting pellet (microsomes) was resuspended by homogenization in 0.1 M sodium pyrophosphate buffer, pH 8.2 (1.3 mL/g original tissue weight), followed by centrifugation at 100,000g. The final microsomal pellet was resuspended in 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), 1.0 mM EDTA, 1.0 mM DTT, 20% glycerol (buffer B), aliquoted and stored at −70 °C. In a separate experiment, a group of six phenobarbital-pretreated rats received an ip dose of [14C] bromobenzene (2.0 mmol/kg) in corn oil (1 mL/kg). Four h later the rats were killed and the liver microsomal fraction was isolated as described earlier (33).

Analysis of Covalent Binding

To determine lipid-bound radioactivity, an aliquot of the aqueous microsomal suspension was subjected to Folch lipid extraction by adding 20 volumes of MeOH/CHCl3 (2:1 v/v) (38). An aliquot of the organic layer was removed for scintillation counting. The remainder was evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen stream and the residual lipid was weighed; the weight was then corrected for the fraction used for scintillation counting. Phospholipid phosphorous was determined according to Ames (39), and protein was determined by Bradford assay using a standard kit (Bio-Rad). To determine protein-bound radioactivity an aliquot of microsomal suspension was precipitated by adding an equal volume of 20% trichloroacetic acid solution. After brief centrifugation the precipitate was washed successively with acetone, methanol/water (80:20 v/v), acetone and diethyl ether, dried by rotary evaporation, dissolved in 1 M NaOH (1 mL) and then neutralized with 1 M HCl (1 mL) for scintillation counting.

Instrumental Analyses

1H NMR spectra of the synthesized compounds were recorded on a Bruker DRX 400 spectrometer. ESI CID spectra were acquired on a Quattro Ultima “triple” quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer (Micromass Ltd., Manchester, UK), acquiring data in continuum mode and scanning at 100 amu/sec. The resolution of quadrupoles 1 and 3 were tuned to 0.6 u FWHH. The collision gas (Ar) density was set to attenuate the precursor by 20% (6E-4 mBar on the guage in the collision gas supply line, a density optimized for precursor scans). Samples were dissolved in MeOH/CHCl3/300mM aqueous NH4OAc (665:300:35 v/v/v) and sprayed through a stainless steel needle set at 2800 V; ions were sampled though a cone set to 35 V. QTof-ESI spectra were acquired on a QTof2 hybrid mass spectrometer (Micromass Ltd., Manchester, UK). The cone voltage was 30eV and Ar was admitted to the collision cell at a pressure that attenuated the beam to about 20% (ca. 20 psi on the supply regulator or 5E-5 mBar on a Penning guage near the collision cell). Spectra were acquired at 11364 Hz pusher frequency covering the mass range 100 to 3000 amu and accumulating data for 5 seconds per cycle. Time-to-mass calibration was made with CsI cluster ions acquired under the same conditions. CID spectra were acquired by setting the MS1 quadrupole to transmit a precursor mass window of ± 1.5 amu centered on the most abundant isotopomer. The collision energy was varied from 20–35 eV to obtain a distribution of fragments from low to high mass. Spectra were acquired for 2–5 min in 5 sec cycles.

Results

Covalent binding of thiobenzamide metabolites in rat liver

In the present study we set out to identify hepatic protein targets for the metabolically-activated hepatotoxin thiobenzamide. Our approach was to use 2DGE followed by phosphorimaging and mass spectrometric analysis of in-gel digests of radioactive protein spots. In the 2D gels of microsomal proteins from the livers of rats treated with 14C-TB we observed1 a large streak of non-proteinaceous radioactive material in the low-pI, low-MW region of the gel. No such material was present in gels of the cytosolic fraction from the same animals. We hypothesized that this material might be comprised of phsophatidylethanolamine (PE) molecules that had been N-acylated by 4, the iminosulfinic acid tautomer of TBSO2 (Scheme 1). The formation of such adducts would be consistent with an earlier report of Hayden et al., who demonstrated thioacylation of mitochondrial PE by a reactive metabolite generated by the action of cysteine conjugate beta-lyase on S-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl)-L-cysteine (TFEC) (40), as well as several other isolated reports of covalent binding to lipids (41–43).

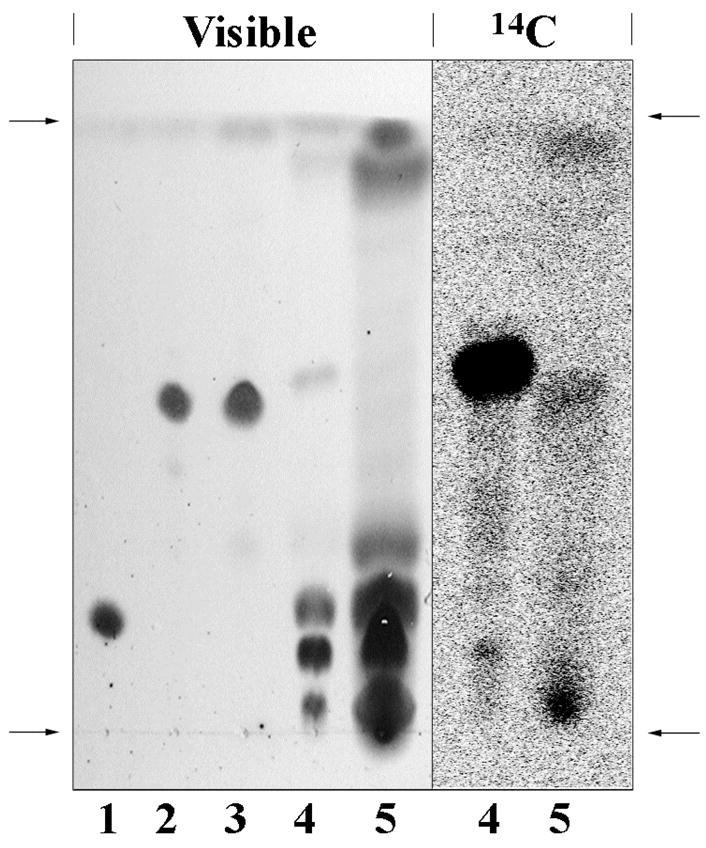

To explore this possibility we separated the lipid and protein fractions of liver microsomes from rats treated with 14C-BB or 14C-TB and analyzed them by scintillation counting and by TLC coupled with phosphorimaging. Despite the fact that the two groups of rats received comparably hepatotoxic doses of chemical, the covalent binding of TB to microsomal proteins and lipids was 10.5-fold and 42-fold greater, respectively, than that of bromobenzene (Table 1). The TLC analysis of these lipid extracts is depicted in Figure 1, which shows both the visible appearance of lipid materials (charred by heating with CuSO4 and H3PO4) and the corresponding phosphorimage of the same plate. The vast majority of the radioactivity in the lipid from the TB-treated animals (lane 4) is contained in a well-defined spot between Rf 0.55–0.62; a corresponding but much lighter spot is clearly visible among the charred lipids in lane 4. On the other hand the radioactivity in the microsomal lipid fraction from the BB-treated animals (lane 5) is much lower in amount (despite the much heavier loading of the plate as seen in the visible image), and is distributed among several regions of the plate with the majority being near the origin. Because of the rather small amount of BB-derived radioactivity in these extracts we pursued structure elucidation only for the TB-derived adducts.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of covalent binding in liver microsomes from phenobartbital induced rats treated in vivo with [14C]-bromobenzene or [14C]-thiobenzamide.

| BB | TB | |

|---|---|---|

| Microsomal protein | ||

| mg microsomal protein/g liver | 16.1a | 14.2 |

| nmol-equiv. 14C/mg microsomal protein | 3.5a | 36.8 |

| Microsomal lipid | ||

| mg microsomal lipid/g liver | 8.3 | 6.8 |

| μmol P/mg microsomal lipid | 8.0 | 6.7 |

| nmol-equiv. 14C/mg microsomal lipid | 1.6 | 66.9 |

| nmol-equiv. 14C/nmol microsomal lipid P | 0.0016 | 0.056 |

Data from ref. 33.

Figure 1.

Separation of microsomal lipids and standards on silica gel thin layer chromatography. The left portion marked “Visible” is a photograph of the TLC plate after heating with CuSO4 and H3PO4 to char the lipids. The right portion marked “14C” is the phosphorimage of the same TLC plate. Lane 1, standard of dipalmitoylphosphatidyl-ethanolamine (DPPE); Lane 2, synthetic standard of N-benzoyl-DPPE; Lane 3, synthetic standard of N-benzimidoyl-DPPE; Lane 4, lipids extracted from the liver microsomal fraction of rats treated with [14C]-thiobenzamide; Lane 5, lipids extracted from the liver microsomal fraction of rats treated with [14C]-bromobenzene. Arrows on the sides indicate the origin (bottom) and solvent front (top) of the plate. The major radioactive spot in lane 4 is centered on Rf 0.6. for comparison the Rf values of other standards (not shown) are TB, 0.79; benzamide, 0.69; benzoic acid, 0.21. These materials are absent from the lipid extracts.

As a guide for identifying PE lipids that might be N-acylated by TBSO2, we synthesized the N-benzimidoyl- and N-benzoyl- derivatives of dipalmitoyl-PE (compounds 7 and 8, respectively). Their thin layer chromatographic behavior is also shown in Figure 1 (lanes 2 and 3, respectively). Although these two N-acylated PE derivatives did not separate from each other under the chromatographic conditions employed, they are well separated from dipalmitoyl-PE (lane 1), and they chromatograph very similarly to the major radioactive spot in lane 4. The three major visible spots at the bottom of lane 4 are native liver microsomal phospholipids including (respectively, from top to bottom) PE, phosphatidylcholine (PC), and other more polar phospholipids (40, 42).

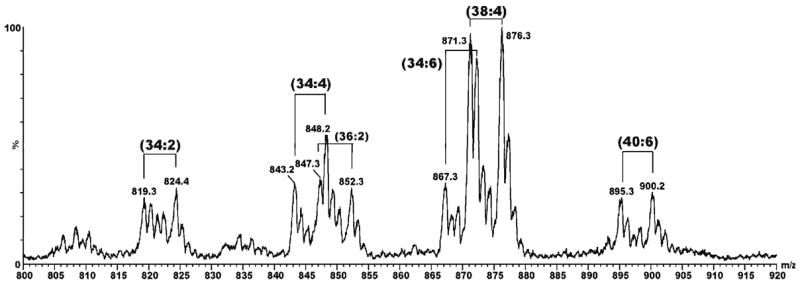

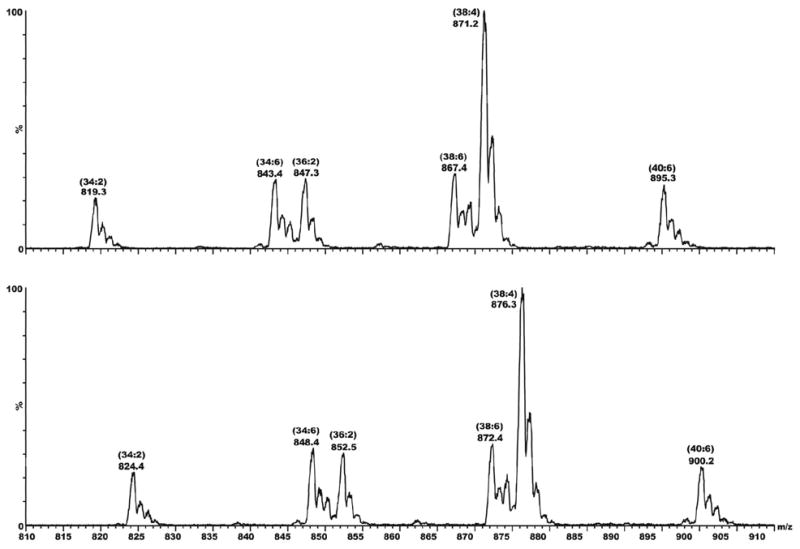

To test the hypothesis that the major radioactive spot in lane 4 contains N-acylated PEs we turned to mass spectrometric analysis of the lipids extracted from liver microsomes of rats that had been treated with a 1:1 mixture of TB and TB-d5 in order to impart a stable isotopic signature to any lipid adducts that might be formed. After TLC separation of the microsomal lipid extract, the Rf 0.55–0.60 region was scraped off the plate and extracted with methanol/chloroform (1:1, v/v). With no further fractionation the extract was analyzed directly on a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer using flow injection and electrospray ionization. Data were collected in the direct MS mode and analyzed manually looking for pairs of mass peaks separated by 5 mass units. Peaks of varying intensity were observed at almost every nominal mass value from 400 to 1000, but there also appeared to be several d0/d5 doublets, the major one occurring at m/z 871 and 876 (Figure 2). These masses are consistent with those expected for the d0/d5 variants of the N-benzimidoyl derivative of a PE species having fatty acyl moieties totaling 38 carbons and 4 double bonds. Considering the known abundances of fatty acids in rat liver phospholipids (44), and the biosynthetic tendency to install saturated fatty acids or oleic acid (18:1) at the sn-1 position of a phospholipid and longer unsaturated fatty acids at the sn-2 position [page 403 of ref. (45)], we hypothesized structure 9 (i.e., R1CO = stearoyl and R2CO = arachidonoyl) for the identity of the lipid material having m/z 871. To gain further support for this tentative assignment we turned to MS/MS analysis of the ion at m/z 871 and its putative d5 analog at m/z 876.

Figure 2.

Mass spectrum of lipids extracted from liver microsomes of rats treated with deuterated thiobenzamide (d0/d5 = 1:1). The lipid extract was subjected to preparative TLC as indicated in Figure 1 and the material extracted from the Rf 0.55–0.62 region was analyzed as described in the Experimental section. Pairs of peaks at m/z 819/824, 843/848, 847/852, 867/872, 871/876 and 895/900 corrrespond in mass to the d0/d5 variants of N-benzimidoyl-PE species having side chain compositions of 34:2, 36:4, 36:2, 38:4, 38:6 and 40:6, respectively.

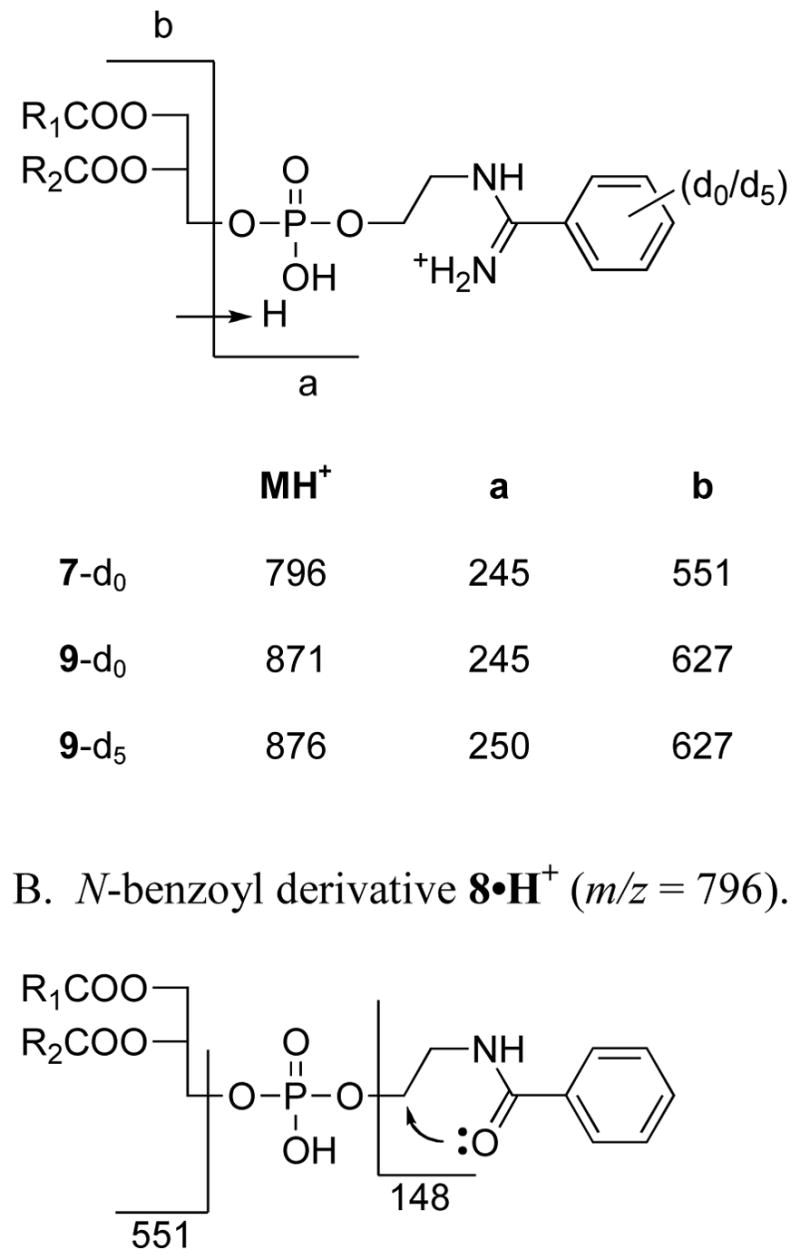

The MS/MS spectra of ions 871 and 876, collected over a range of collision energies, each consistently showed a single major fragment ion at m/z 245 and 250, respectively (Figure S1). A much weaker ion containing no deuterium was observed at m/z 627 in both cases. The 627 ion corresponds to the diacylglycerol moiety of 9, as indicated in Scheme 2. Examination of the MS/MS spectra of synthetic standards 7 and 8 provides further support for this proposal. The MS/MS spectrum of the N-benzimidoyl derivative 7 (Figure S2) shows a very strong fragment ion at m/z 245 and a weaker ion at m/z 551, the latter corresponding to the diacylglycerol moiety in 7. In contrast, the MS/MS of the N-benzoyl derivative 8 shows no peak at 245, but instead shows a single strong fragment ion at m/z 148, corresponding to the 2-phenyloxazolinium ion formed by the intramolecular cyclization shown in Scheme 2B. Such a cyclization is not possible with the amidine analogs (Scheme 2A) which are protonated due to their appreciable basicity.

Scheme 2.

MS/MS fragmentation of N-acyl PE derivatives. A. N-benzimidoyl derivatives.

Further evidence characterizing the adducts seen in Figure 1 as N-benzimidoyl-PE derivatives was obtained from MS/MS scans for precursors to m/z 245 and 250, as shown in Figure 3. Except for the 5 unit mass offset, these two scans are identical in all respects (including their 1:1 absolute intensity ratio, which corresponds to the 1:1 ratio of d0/d5 thiobenzamide administered to the animals). In addition, the sum of these two scans is extremely similar to the original MS1 scan shown in Figure 1, confirming that the adducts are N-benzimidoyl derivatives of typical PE species found in liver microsomes (46, 44), and not N-benzoyl derivatives (i.e., 5 and not 6 in Scheme 1).

Figure 3.

Mass spectral scans showing precursors of fragment ions at m/z 245 (top) and 250 (bottom). The sample here is the same as that examined in MS1 mode (Figure 2) and MS/MS mode (Figure S1).

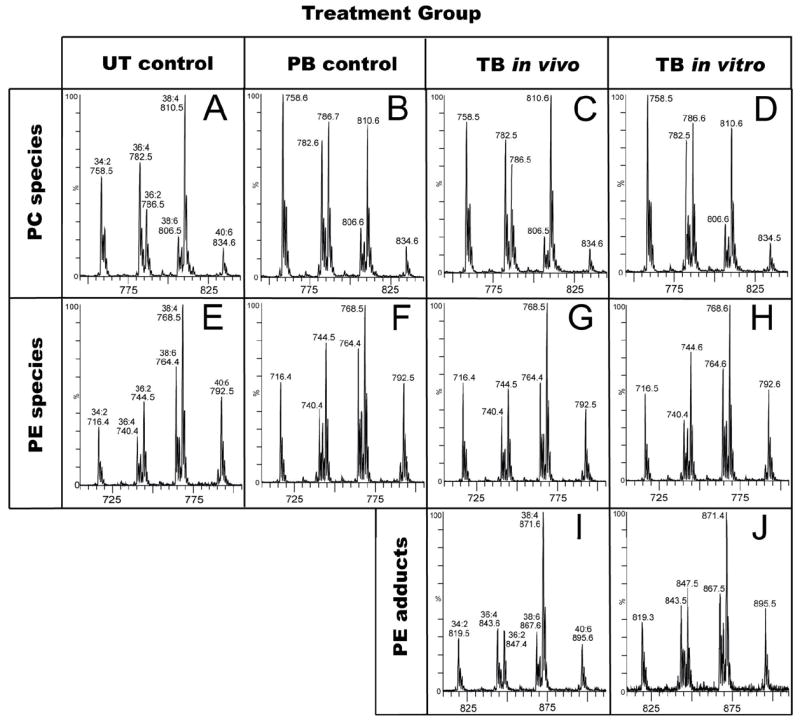

The covalent labeling of hepatocellular proteins by chemically reactive metabolites is a selective rather than random process, in that many abundant proteins acquire little if any radiolabel while some low-abundance proteins become highly labeled (33, 47). To determine whether the reactive metabolite of TB reacts preferentially with different PE species in rat liver microsomes we used mass spectrometric methods to compare the side chain profiles of the PE fractions of liver microsomes from untreated (UT) control rats, phenobarbital pretreated (PB) control rats and PB rats that were also treated with TB (Figure 4, panels E, F and G, respectively). These profiles, which are highly reproducible, show that the change in the PE side chain profile after TB treatment (Figure 4G vs. 4F) is no greater than that caused by PB induction alone (Figure 4F vs. 4E). Similarly, the profile of PE side chains in microsomes from TB-treated rats differs little from that of microsomes incubated in vitro with TB and NADPH (Figure 4G vs. 4H). The side chain profiles of adducted PEs formed in vivo vs. in vitro are also quite similar (Figure 4I vs. 4J). Finally, in these same bulk lipid extracts we also examined the side chain profiles of PC lipids, which do not form adducts, in order to have some frame of reference for the magnitude of differences seen (Figures 4A–4D). Differences among these side chain profiles are no larger than among any of the PE profiles, and again the largest difference is due the phenobarbital treatment, not to thiobenzamide treatment. Data for the quantitative integration of the profiles in Figures 4A–4J are given in Table S1 of the supporting information.

Figure 4.

Mass spectral profiles of lipid fractions from rat liver microsomes. To facilitate visual comparisons, these profiles are shown on appropriately offset mass scales. Panels A–D show precursor ion scans for m/z 184, a diagnostic fragment for PC species. The lipids were from untreated (UT) control rats (A), phenobarbital (PB)-treated control rats (B), PB rats treated with TB-d0 (C), or PB microsomes incubated in vitro with NADPH and TB-d0 (D). Panels E–H show scans for detecting the neutral loss of 141 mass units (aminoethyl phosphate), a diagnostic loss for unmodified PE species. The lipids were from UT control rats (E), PB control rats (F), PB rats treated with TB-d0 (G), or PB microsomes incubated in vitro with NADPH and TB-d0 (H). Panels I and J show precursor ion scans for m/z 245, a diagnostic fragment for N-benzimidoyl-PE species. The lipids were extracted from microsomes from PB rats treated with TB-d0 (panel I), or liver microsomes from PB rats incubated in vitro with NADPH and TB-d0 (panel J). For quantitative information from peak integrations see Supporting Information.

Discussion

The overall extent of lipid covalent binding by TB metabolites observed in these studies is simply extraordinary by comparison to levels reported for other metabolically-activated pro-toxins (Table 2). Bromobenzene and acetaminophen give rise to electrophilic arylating metabolites (epoxide and quinoid species) that strongly prefer sulfur over nitrogen or oxygen nucleophiles. These metabolites tend to show a high ratios of protein:lipid binding, perhaps because lipids contain no sulfur nucleophiles. On the other hand, TB, TFEC and DCVC form acylating or thioacylating metabolites having a strong preference for amine-type nucleophiles. Thus, like cyanate ion, their metabolites show decreased or even inverse protein:lipid binding ratios. Compared to bromobenzene metabolites, thiobenzamide metabolites are 4-fold to 10-fold more selective for binding to microsomal PE vs. microsomal protein. Since PEs comprise ca. 25% of cellular phospholipids (48, 46), the observed binding of 0.056 nmol-equiv TB/nmol P potentially equates to the adduction of ca. 23% of all PE molecules in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. In contrast, the typical binding of reactive metabolites of BB to microsomal protein (ca. 2 nmol-equiv/mg protein, in vivo or in vitro) is such that for an average 40 kDa protein, only about 1 molecule in 20 acquires a single adduct moiety.

Table 2.

Lipid vs. Protein Covalent Binding of Electrophilic Reactive Metaboliltes.

| Chemical | Experimental Conditions | Protein Binding (nmol/mg) | Lipid Binding (nmol/mg) | Ratio | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiobenzamide | PB-induced S-D rat 0.86 mmol/kg, 5 h | 36.8a | 66.9a | 0.55 | this work |

| NaNCO | 25 mM, red cell ghosts in vitro (1.5 mg protein/mL), 10 h | 2.5 | 4.0 | 0.63 | 42 |

| TFECd | 0.1 mM, rat kidney mitochondria in vitro (4 mg wet wt/mL), 60 min | 10.0 | 7.2 | 1.39 | 40 |

| DCVCc | 0.1 mM, rat kidney mitochondria in vitro (4 mg wet wt/mL), 60 min | 12.0 | 5.3 | 2.26 | 40 |

| Bromobenzene | PB-induced S-D rat 2.0 mmol/kg, 4 h | 3.5a | 1.6a | 2.2 | this work |

| Bromobenzene | PB-induced S-D rat 1.43 mmol/kg, 4 h | 1.31b | 0.24b | 5.45 | 41 |

| Acetaminophen | PB-induced mouse 2.45 mmol/kg, 3 h | 1.19b | 0.11b | 10.8 | 41 |

| Acetaminophen | 1 mM, 3MC-induced mouse liver microsomes in vitro (1 mg prot./mL) 15 min | 2.9 | 0.1 | 29 | 43 |

Sprague-Dawley rat liver microsomal fraction,

Whole liver homogenate.

S-(1,2-dichlorovinyl)-L-cysteine

S-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl)-L-cysteine

At first glance such extensive lipid modification in the endoplasmic reticulum of a rat hepatocyte would seem to be a huge perturbation potentially capable of significantly altering membrane properties and function. However, numerous observations in the literature tend to suggest otherwise. For example, in the absence of ethanolamine (EA) as a substrate for phospholipid synthesis, rat hepatocytes (49) and fibroblast cell lines (46, 50) readily incorporated EA analogs into membrane phospholipids. The extent of analog incorporation approached 50% in some cases, which decreased the proportion of normal PC and PE lipids in the cells from 48% to 12%, and from 28% to 13%, respectively. In these experiments the cells grew at normal rates for up to three days although some analogs failed to support further growth or even led to decreases in cell numbers after three days (46). Likewise manipulating the fatty acid content of the growth medium can vary the content of linoleic or saturated fatty acyl groups in cell phospholipids from 0–37% or 28–85%, respectively (50). In addition, many non-natural fatty acids become incorporated into lipid biosynthetic pathways (51), leading in some cases to accumulation of “xenobiotic residues” in tissues. Such changes in membrane lipids showed no effects on the activities of seven membrane-bound enzymes (46).

Of greater relevance here, perhaps, is the observation that N-acyl-PE derivatives (NAPEs) occur naturally in plants and animals. In plants they are hydrolyzed by phospholipase D enzymes to form N-acylethanolamines (NAEs) that in turn modify ion fluxes and activate defense gene expression (52). In mammalian brain N-arachidonoyl-PEs are hydrolyzed analogously to form anandamide, a partial agonist for cannnabinoid receptors. NAEs have also been suggested to be neuroprotective in cases of trauma, ischemia and neurodegenerative diseases (53). For long-chainNAPEs the N-acyl chain is bent back and inserted into the hydrophobic bilayer (37), but this is unlikey for steric reasons with N-benzimidoyl-PEs such as 7 or 9. Finally, whereas N-acylation converts the cationic (protonated ammonium) PE end group into a neutral amido group, N-benzimidoylation preserves the cationic character of the end group as a basic amidinium moiety (Scheme 2).

The apparent capacity of cells to tolerate major changes in the composition of their lipid membranes, at least over the short term, suggests the possibility that PE adduction by TB metabolites might actually be a detoxication event analogous to the trapping of reactive metabolites by glutathione. However, before rushing to this conclusion it must be remembered that even glutatione conjugates can sometimes be quite toxic. At this point, one cannot draw firm conclusions about the toxicological significance of PE adduction byTB metabolites; too many questions about the N-benzimidoyl-PEs formed remain unanswered. For example, the rates of clearance and the ultimate disposition of the N-benzimidoyl-PEs formed in the ER of TB-treated animals are unknown.2 Nor is it known if other membrane fractions such as plasma membrane or mitochondrial membrane are similarly affected, or what the long term effects of such changes in membrane composition might be if the adducts prove to be somewhat persistent. Answers to these questions must await further study.

In addition to the potential chemical mechanistic and toxicological implications of lipid adduction mentioned above, the formation of substantial amounts of PE adducts of reactive metabolites may also be of practical use as a natural “in situ” monitor for the formation of reactive metabolites in vivo or in vitro. It is now common to screen potential drug candidates for their ability to form reactive metabolites by incubating the compound with liver microsomes supplemented with glutathione and using LC/MS methods to detect glutathione adducts. Since reactive metabolites may differ in their preference for nitrogen vs. sulfur nucleophiles, and since LC/MS screening for lipid adducts is quite straightforward, it may be useful to search these screening incubations not only for the formation of GSH adducts but also for the formation of lipid adducts.

Supplementary Material

MS/MS spectra (Figures S1 and S2) and table of quantitative information from integration of peaks in Figure 4. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by NIH grant GM-21784 (to R.P.H). The Micromass Ultima and Q-TOF2 were purchased with funds from the Kansas NSF EPSCoR and the KU Research and Development Fund. TDW and SWE were supported through the Kansas Lipidomics Research Center by National Science Foundation’s EPSCoR program (EPS-0236913) with matching support from the State of Kansas through Kansas Technology Enterprise Corporation.

Footnotes

These gels are not shown here because they look generally similar to those from 14C-BB treated animals as shown in ref. 33. Pictures of the TB-derived gels will be presented in a separate manuscript dealing with identification of the numerous proteins that become adducted with TB metabolites.

One might speculate that they would be hydrolyzed by phospholipase D and ultimately oxidized and excreted as hippuric acid or its amidino analog N-benzimodoyl glycine.

References

- 1.Dieke SH, Allen G, Richter CP. The Acute Toxicity of Thioureas and Related Compounds to Wild and Domestic Norway Rats. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1947;90:490–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richter CP. The Development and Use of alpha-Naphthyl Thiourea (ANTU) as a Rat Poison. J Amer Med Assoc. 1945;129:927–931. doi: 10.1001/jama.1945.02860480007002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chilakapati J, Shankar K, Korrapati MC, Hill RA, Mehendale HM. Saturation Toxicokinetics of Thioacetamide: Role in Initiation of Liver Injury. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1877–1885. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neal RA, Halpert JA. Toxicology of Thiono-Sulfur Compounds. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1982;22:321–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nikolaev V, Kerimova M, Naydenova E, Dimov S, Savov G, Ivanov E. The Effect of Thioacetamide on Rat Liver Plasma Membrane Enzymes and its Potentiation by Fasting. Toxicology. 1986;38:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(86)90121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cashman JR, Parikh KK, Traiger GJ, Hanzlik RP. Relative Hepatotoxicity of ortho and meta Monosubstituted Thiobenzamides in the Rat. Chem-Biol Interactions. 1983;45:342–347. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(83)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanzlik RP, Cashman JR, Traiger GJ. Relative Hepatotoxicity of Substituted Thiobenzamides and Thiobenzamide-S-oxides in the Rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1980;55:260–272. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(80)90088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanzlik RP, Vyas KP, Traiger GJ. Substituent Effects on the Hepatotoxicity of Thiobenzamide Derivatives in the Rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1978;46:685–694. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(78)90313-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baulard AR, Betts JC, Engohang-Ndong J, Quan S, McAdam RA, Brennan PJ, Locht C, Besra GS. Activation of the Pro-Drug Ethionamide is Regulated in Mycobacteria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28326–28331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003744200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeBarber AE, Mdluli K, Bosman M, Bekker LG, Barry CE. Ethionamide Activation and Sensitivity in Multidrug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9677–9682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vannelli TA, Dykman A, Ortiz de Montellano PR. The Antituberculosis Drug Ethionamide is Activated by a Flavorprotein Monooxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12824–12829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanzlik RP. Prediction of Metabolic Pathways - Sulfur Functional Groups. In: Caldwell J, Paulson GD, editors. Foreign Compound Metabolism. Taylor & Francis; London: 1984. pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cashman JR, Hanzlik RP. Microsomal Oxidation of Thiobenzamide. A Photometric Assay for the Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;98:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(81)91881-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo WX, Poulsen LL, Ziegler DM. Use of Thiocarbamides as Selective Substrate Probes for Isoforms of Favin-Containing Monooxygenases. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44:2029–2037. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90106-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang T, Shankar K, Ronis MJJ, Mehendale HM. Potentiation of Thioacetamide Liver Injury in Diabetic Rats is due to CYP2E1. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2000;294:473–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanzlik RP, Cashman JR. Microsomal Metabolism of Thiobenzamide and Thiobenzamide-S-oxide. Drug Metab Dispos. 1983;11:210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walter W, Curts J. Oxydationsprodukte von Thiocarbonsäureamiden, III. Oxydationsprodukte primärer Thioamide. Chem Ber. 1960;93:1511–1517. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cashman JR, Hanzlik RP. Oxidation and Other Reactions of Thiobenzamide Derivatives of Relevance to Their Hepatotoxicity. J Org Chem. 1982;47:4745–4650. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maryanoff CA, Stanzione RC, Plampin JN, Mills JE. A Convenient Synthesis of Guanidines from Thioureas. J Org Chem. 1986;51:1882–1884. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liebler DC, Guengerich FP. Elucidating Mechanisms of Drug-Induced Toxicity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:410–420. doi: 10.1038/nrd1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LoPachin RM, DeCaprio AP. Protein Adduct Formation as a Molecular Mechanism in Neurotoxicity. Tox Sci. 2005;86:214–225. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park KB, Ketteringham NR, Maggs JL, Pirmohamed M, Williams DP. The Role of Metabolic Activation in Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:177–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.100058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyd MR, Neal RA. Studies on the Mechanism of Toxicity and of Development of Tolerance to the Pulmonary Toxin α-Naphthylthiourea (ANTU) 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hollinger MA, Giri SN, Hwang F. Binding of Radioactivity from [14C]Thiourea to Rat Lung Protein. Drug Metab Dispos. 1976;4:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanzlik RP. Chemistry of Covalent Binding: Studies with Bromobenzene and Thiobenzamide. Adv Exper Med Biol. 1986;197:31–40. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-5134-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter AL, Holscher MA, Neal RA. Thioacetamide-Induced Hepatic Necrosis. I. Involvement of the Mixed-Function Oxidase Enzyme System. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1977;200:439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter WR, Neal RA. Metabolilsm of Thioacetamide and Thioacetamide S-Oxide by Rat Liver Microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1978;6:379–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dennehy MK, Richards KAM, Wernke GR, Shyr Y, Liebler DC. Cytosolic and Nuclear Protein Targets of Thiol-Reactive Electrophiles. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:20–29. doi: 10.1021/tx050312l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin CY, Isbell MA, Morin D, Boland BC, Salemi MR, Jewell WT, Weir AJ, Fanucchi MV, Baker GL, Plopper CG, Buckpitt AR. Characterization of a Structurally Intact in Situ Lung Model and Comparison of Naphthalene Protein Adducts Generated in This Model vs Lung Microsomes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:802–813. doi: 10.1021/tx049746r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meier BW, Gomez JD, Zhou A, Thompson JA. Immunochemical and Proteomic Analysis of Covalent Adducts Formed by Quinone Methide Tumor Promoters in Mouse Lung Epithelial Cell Lines. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1575–1585. doi: 10.1021/tx050108y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers TG, Dietz EC, Anderson NL, Khairallah EA, Cohen SD, Nelson SD. A Comparative Study of Mouse Liver Proteins Arylated by Reactive Metabolites of Acetaminophen and its Nonhepatotoxic Regioisomer, 3′-Hydroxyacetanilide. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:403–413. doi: 10.1021/tx00045a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson SD, Pearson PG. Covalent and Noncovalent Interactions in Acute Lethal Cell Injury Caused by Chemicals. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1990;30:169–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.30.040190.001125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koen YM, Hanzlik RP. Identification of Seven Proteins in the Endoplasmic Reticulum as Targets for Reactive Metabolites of Bromobenzene. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:699–706. doi: 10.1021/tx0101898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bambal RB, Hanzlik RP. Bromobenzene-3,4-Oxide Alkylates Histidine and Lysine Side Chains of Rat Liver Proteins in Vivo. Chem Res Toxicol. 1995;8:729–735. doi: 10.1021/tx00047a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weller PE, Hanzlik RP. Synthesis of Substituted Bromobenzene Derivatives via Bromoanilines. A Moderately Selective ortho-Bromination of [14C]-Aniline. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 1988;25:991–998. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jesberger M, Davis TP, Barner L. Applications of Lawesson’s Reagent in Organic and Organometallic Synthesis. Synthesis. 2003:1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caramelo JJ, Forin-Christensen J, Delfino JM. Phosphplipase Activity on N-Acyl Phosphatidylethanolamines is Critically Dependent on the N-Acyl Chain Length. Biochem J. 2003;374:109–115. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A Rapid Method of Total Lipid Extraction and Purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ames BN. Assay of Inorganic Phosphate, Total Phosphate and Phosphatases. Meth Enzymol. 1966;8:115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hayden PJ, Welsh CJ, Yang Y, Schaefer WH, Ward AJI, Stevens JL. Formation of Mitochondrial Phospholipid Adducts by Nephrotoxic Cysteine Conjugate Metabolites. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:231–237. doi: 10.1021/tx00026a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith CV, Jughes H, Mitchell JR. Free Radical in Vivo. Covalent Binding to Lipids. Meth Pharmacol. 1984;26:112–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trepanier DJ, Thibert RJ. Carbamylation of Erythrocyte Membrane Aminophospholipids: an in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Clin Biochem. 1996;29:333–345. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wendel A, Hallbach J. Quantitative Assessment of the Binding of Acetaminop[hen Metabolites to Mouse Liver Microsomal Phospholipid. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35:385–389. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood R, Harlow RD. Structural Studies of Neutral Glycerides and Phosphoglycerides of Rat Liver. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1969;131:495–501. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(69)90421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glew RH. Lipid Metabolism II: Pathways of Metabolism of Special Lipids. In: Devlin TM, editor. Textbook of Biochemistry with Clinical Correlations. Wiley-Liss; New York: 1997. pp. 395–443. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schroeder F, Perlmutter JF, Glaser M, Vagelos PR. Isolation and Characterization of Subcellular Membranes with Altered Phospholipid Composition from Cultured Fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:5015–5026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koen YM, Yue W, Galeva NA, Williams TD, Hanzlik RP. Site-Specific Arylation of Rat Glutathione S-Transferase A1 and A2 by Bromobenzene Metabolites in Vivo. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006 doi: 10.1021/tx060142s. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dawson RMC. A Hydrolytic Procedure for the Identification and Estimation of Individual Phospholipids in Biological Samples. Biochem J. 1960;75:45–53. doi: 10.1042/bj0750045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sundler R, Åkesson B. Regulation of Phospholipid Biosynthesis in Isolated Rat Hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:3359–3367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spector AA, Yorek MA. Membrane Lipid Composition and Cellular Function. J Lipid Res. 1985;26:1015–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dodds PF. Xenobiotic Lipids: The Inclusion of Xenobiotic Compounds in Pathways of Lipid Biosynthesis. Prog Lipid Res. 1995;34:219–247. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(95)00007-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chapman KD. Emerging Physiological Roles for N-Acylphosphatidylethanolamine Metabolism in Plants: Signal Transduction and Membrane Protection. Chem Phys Lipids. 2000;108:221–230. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(00)00198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hansen HS, Moesgaard B, Petersen G, Hanses HK. Putative Neuroprotective Actions of N-Acyl-Ethanolamines. Pharmac Ther. 2002;95:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

MS/MS spectra (Figures S1 and S2) and table of quantitative information from integration of peaks in Figure 4. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.