Abstract

Increased rates of diabetes have been reported with thiazide diuretics and beta-blockers, but not with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers or calcium channel blockers. These observations are important because significant glycemic effects of drugs may be a source of accelerated cardiovascular risk that is not detectable during restricted clinical trial follow-up periods. The extent to which diabetes is affected by these medications remains unclear, as is the precise mechanism by which diabetes is promoted. However, several plausible theories are presented herein. Although drug-induced diabetes has been a concern for several years, not enough is information is available to influence prescribing for the majority of patients. The number one priority should be controlling blood pressure in a timely manner.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Hypertension

Abstract

Une augmentation des taux de diabète a été signalée avec les diurétiques thiazidiques et les bêta-bloquants, mais non avec les inhibiteurs de l’enzyme de conversion de l’angiotensine, les bloqueurs des récepteurs de l’angiotensine ou les anticalciques. Le phénomène est important puisque les effets glycémiques marqués de ces médicaments peuvent entraîner une exacerbation du risque cardiovasculaire difficilement décelable compte tenu de la brièveté des suivis lors des essais cliniques. On ignore encore quelle est la portée exacte de ces médicaments sur le diabète et par quel mécanisme précis ce dernier serait ainsi favorisé. Par contre, plusieurs théories plausibles sont présentées ici. Bien que le diabète d’origine médicamenteuse suscite déjà l’inquiétude depuis quelques années, les données dont on dispose actuellement sont encore insuffisantes pour que l’on puisse modifier les prescriptions remises à la majorité des patients, l’objectif numéro un du traitement demeurant l’obtention dans les meilleurs délais d’une bonne maîtrise de la tension artérielle.

The cardiovascular benefits of reducing blood pressure (BP) have been well documented (1–4) and usually occur independently of the specific antihypertensive agent used (3–7). As a result, clinical practice guidelines suggest that several antihypertensive classes are acceptable first-line agents for the management of uncomplicated hypertension. These classes include thiazide diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers (8,9). Despite their similar cardiovascular benefits, however, antihypertensive agents clearly exhibit distinct adverse effects.

One major difference among antihypertensive agents is the potential to adversely affect glucose homeostasis. Certain agents have been associated with insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus, which are independent predictors of cardiovascular morbidity (10–13). Two reports (14,15) have suggested that elevated serum glucose concentrations during antihypertensive treatment predicts future cardiovascular events, while another report (16) has found that diabetes occurring during antihypertensive therapy is inconsequential. Of course, patients who develop diabetes mellitus may require more intensive monitoring and more medications to achieve strict glycemic, cholesterol and BP targets (8,10,17,18).

In this narrative review, we will summarize the various mechanisms by which antihypertensive medications may cause diabetes, report on the results of several notable clinical trials and review the potential long-term implications of developing diabetes due to antihypertensive therapy. For a comprehensive summary of available evidence, we refer readers to an excellent systematic review that has been recently published (19).

MECHANISMS OF ADVERSE GLYCEMIC EFFECTS

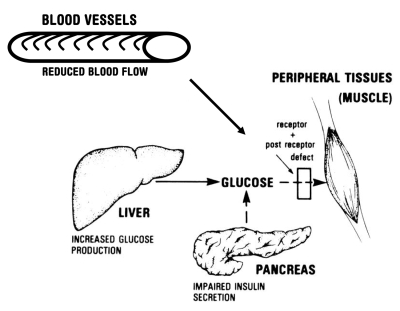

Various theories about the mechanisms of antihypertensive-induced glycemic defects have been postulated. Few of these theories have been confirmed and some are conflicting. In general, postulated mechanisms can be classified into four categories: effects on peripheral blood flow, effects on the insulin receptor, effects on the liver and effects on insulin release (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Summary of the metabolic abnormalities that contribute to hyperglycemia. Reduced blood flow to tissues, increased hepatic glucose production, impaired insulin secretion, and insulin resistance caused by receptor and postreceptor defects all combine to generate the hyper-glycemic state. Reproduced with permission from The American Diabetes Association (personal communication)

Improved peripheral blood flow to skeletal muscles is thought to facilitate glucose disposal to the tissues. In this way, medications such as alpha-blockers, which promote peripheral vasodilation, may improve insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake (20). Through the same mechanism, ACEIs or ARBs may improve insulin sensitivity by reducing angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction and/or increasing vasodilators such as bradykinin, prostaglandins or nitric oxide (21,22).

Conversely, medications that reduce peripheral blood flow could direct blood away from sites of glucose uptake, reducing glucose disposal (20). Nonselective beta-blockers limit peripheral blood flow by reducing cardiac output, a beta-1-mediated effect, and preventing peripheral vasodilation, a beta-2-mediated effect (20,23). Beta-blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity are less likely than nonselective agents to reduce peripheral blood flow because of neutral or stimulatory effects on beta-2 receptors (20,23). Therefore, these agents may have a reduced impact on glucose disposal and insulin sensitivity compared with nonselective beta-blockers. Cardioselective beta-blockers are also less likely to reduce peripheral blood flow than nonselective agents; however, cardioselective beta-blockers still exhibit some glycemic adverse effects (23). In support of the blood flow hypothesis is the observation that reduced capillary density in skeletal muscle places individuals at a greater risk for beta-blocker-induced glycemic effects (20,23).

Insulin sensitivity may also be altered through effects on the insulin receptor or downstream signalling. Although few studies have directly examined changes to the insulin receptor, it appears that some antihypertensive agents may modify its activity. Hypokalemia has been linked to reduced insulin-receptor sensitivity (24), but this theory has not been consistently supported (25,26). Various antihypertensive agents could alter glucose transport proteins (GLUT 1 and GLUT 4), tyrosine kinase activity, or insulin receptor binding affinity. However, more information is needed to evaluate these effects (21,27).

Two other potential sources of altered glucose control include hepatic insulin resistance and impaired insulin release. It has been suggested that thiazide diuretics promote hepatic insulin resistance, resulting in continued hepatic glucose production despite rising serum glucose or insulin levels (24,28). Although this effect has been observed with high-dose thiazide diuretics, it is less apparent with lower doses (12.5 mg to 25 mg of hydrochlorothiazide daily) used in current practice (28). Inhibition of insulin release can lead to hyperglycemia, and beta-blockers have long been considered to inhibit insulin release through pancreatic beta-receptor blockade (29). Similarly, diuretic therapy has also been associated with impaired insulin release through depletion of serum potassium (30). However, because insulin levels are higher than normal in most patients with diabetes (23), this mechanism is unlikely to be of major importance.

INCIDENCE OF DIABETES DURING ANTIHYPERTENSIVE TREATMENT

Beta-blockers

In observational studies, thiazides (15,31,32) and beta-blockers (25,29,31–34) have been most commonly linked to the development of diabetes mellitus. In one notable study suggesting the harmful effects of beta-blockers, the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study (29), over 12,000 nondiabetic subjects were identified and followed prospectively. Among subjects with hypertension at baseline, beta-blockers were associated with an increased risk of diabetes development (hazard ratio 1.28, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.57), while thiazide diuretics, ACEIs and calcium channel blockers did not exhibit such effects. Three studies (25,33,34) have reached similar conclusions about the relative effects of beta-blockers and thiazide diuretics, but these studies are less robust and provide no additional information. In a post hoc analysis of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) clinical trial (chlorthalidone versus placebo), the addition of atenolol to chlorthalidone increased the rate of new-onset diabetes by 40% (16.4% versus 11.8% for chlorthalidone- and placebo-treated patients, respectively) (16). There are, however, exceptions. In a recent study of elderly patients (at least 66 years of age) receiving antihypertensive therapy (35), new-onset diabetes was not increased with any medication class.

Although most studies suggest that beta-blockers exhibit significant glycemic effects, there is little information on the differences between cardioselective and nonselective beta-blockers. Most reports only examine nonselective agents such as propranolol (8,33,34), and others do not distinguish between agents with and without beta-1 selectivity (15,29,31,32,35). In addition, many of these studies neglect to closely document the extent of drug exposure.

Several clinical trials have evaluated the short-term effects of beta-blockers with intrinsic sympathomimetic activity (dilevalol [36] and pindolol [37]) or alpha-blocking effects (carvedilol [38,39]). Consistent with the blood flow hypothesis, these agents appear to have a reduced impact on insulin sensitivity compared with nonselective (37) and cardioselective agents (36,38,39), presumably because of favourable effects on peripheral blood flow. Considering the fact that cardioselective beta-blockers are used extensively in uncomplicated hypertension, further study is needed to quantify their glycemic effects.

Thiazide diuretics

In 1981, a randomized, controlled trial from the Medical Research Council (40) suggested that thiazide diuretics exhibited significant adverse glycemic effects. Patients receiving bendrofluazide developed more impaired glucose tolerance than those receiving propranolol (15.4 versus 4.8 cases per 1000 patient-years, respectively). Although this difference was striking, the dose of bendrofluazide was extremely high at 5 mg twice daily. Currently used thiazide diuretics are administered at a fraction of this dose.

To examine the effect of lower doses, Harper et al (28) randomly assigned 15 hypertensive patients to high-dose (5 mg) or low-dose (1.25 mg) bendrofluazide for 12 weeks in a double-blind, crossover study. No differences were observed for fasting glucose, serum lipid values or peripheral insulin sensitivity; however, endogenous (hepatic) glucose production was significantly greater in the high-dose group, suggesting that a reduction in hepatic insulin sensitivity had occurred.

Although high-dose thiazide diuretics are no longer used to manage hypertension, glycemic adverse effects may still be a consequence of low-dose agents. Recently, Verdecchia et al (15) reported an increased rate of diabetes development in patients receiving low-dose thiazides but not other antihypertensive agents, including beta-blockers. Also, three large, prospective clinical trials have demonstrated definite adverse effects of thiazides on glucose homeostasis (1,4,7). In the SHEP trial (1), three years of low-dose chlorthalidone, 12.5 mg to 25 mg daily, was associated with a significant elevation in fasting glucose compared with placebo (0.51 mmol/L versus 0.31 mmol/L, respectively; P<0.01) and a significant increase in the incidence of diabetes (13.0% versus 8.7%, respectively; P<0.001) (16). In the recently published Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering treatment to prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) (7), over 42,000 hypertensive patients were randomly assigned to one of four groups: chlorthalidone, amlodipine, lisinopril or doxazosin. Of the three arms remaining after four years, the incidence of diabetes was significantly higher in the chlorthalidone arm (11.6%) than in the amlodipine arm (9.8%; P=0.04) and the lisinopril arm (8.1%; P<0.001). Atenolol was allowed as add-on therapy and may have influenced this outcome, but the proportion of patients receiving it was not specified. A similar study of hypertensive patients (4) reported a higher rate of new-onset diabetes in patients receiving low-dose diuretic therapy than in those receiving long-acting nifedipine (5.6% versus 4.3%, respectively; P=0.02).

Many of these studies do not address the impact of initial antihypertensive selection because most patients had previously received antihypertensive therapy. Also, comparator groups are clouded by the use of various agents as adjuvant therapy. Although thiazide diuretics provide similar cardiovascular benefits to other antihypertensive classes over the short-term (7), some have expressed concern that new-onset diabetes accelerates cardiovascular risk over the long-term (14,15).

Other agents

Three additional classes of medications – ACEIs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and ARBs – are also considered acceptable first-line agents in the management of patients with uncomplicated hypertension (8). In contrast with beta-blockers and thiazide diuretics, these agents have not been associated with glycemic adverse effects. Calcium channel blockers are generally thought to exhibit negligible effects on glucose metabolism (35,41), and ACEIs/ARBs may actually have beneficial effects.

Support for a protective effect of ACEIs/ARBs comes from the results of several prospective clinical trials. In the Captopril Prevention Project (CAPP) (3), a randomized trial comparing captopril with beta-blockers or diuretics in 11,000 patients with hypertension, the incidence of diabetes was reduced by 20% in patients treated with captopril. Because there was no placebo group, it is not clear whether the difference in diabetes development was a result of a protective effect of captopril or a harmful effect of beta-blockers or diuretics. A more recently published trial (42), the International Verapamil-Trandolapril Study (INVEST), compared verapamil- and atenolol-based regimens in hypertensive patients with stable coronary artery disease. In a post hoc analysis of new diabetes occurring during this study, the addition of trandolapril appeared to confer a protective effect against diabetes development. Another recent trial (43) in hypertensive patients, the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial, enrolled 15,245 hypertensive patients and demonstrated a lower rate of diabetes in patients receiving valsartan than in those receiving amlodipine (13.1% versus 16.4%, respectively; P<0.0001). Other studies (44,45) have also indicated the protective effects of ACEIs or ARBs in patients without hypertension.

Short-term studies have confirmed that ACEIs are less likely to impair glucose metabolism than beta-blockers (26,46), and some ACEIs have shown a protective effect compared with placebo (21,47,48). Three similar studies by Fogari et al demonstrated the protective effects of lisinopril (47), perindopril (48) and trandolapril (21) compared with placebo and losartan, which had little impact on glycemic indexes. However, it is unclear whether differences in dosing intensity or BP control confounded the comparisons with losartan. In contrast, losartan was associated with a reduction in new-onset diabetes compared with atenolol in the prospective Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension (LIFE) study (49); 241 (6%) and 319 (8%) new-onset diabetes cases were reported for losartan and atenolol over an average follow-up period of 4.8 years, respectively (hazard ratio 0.75, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.88; P=0.001).

It should be noted that hypertension itself is often an insulin-resistant state, and that the incidence of diabetes in the untreated hypertensive population is elevated (20). Therefore, it is difficult to say whether beta-blockers and thiazides accelerate the development of diabetes, or whether ACEIs and angiotensin receptor antagonists confer a protective effect. Several ongoing studies are evaluating the use of ACEIs or ARBs in patients with impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance. Ramipril is currently being studied in the Diabetes Reduction Assessment with ramipril and rosiglita-zone Medication (DREAM) trial, valsartan in the Nateglinide And Valsartan in Impaired Glucose Tolerance Outcomes Research (NAVIGATOR) trial, and irbesartan in the Irbesartan in the Treatment of Hypertensive Patients with Metabolic syndrome trial. In addition, further analyses of the ALLHAT study are expected to shed more light on the differences observed between lisinopril, amlodipine and chlorthalidone.

IMPLICATIONS OF GLYCEMIC ADVERSE EFFECTS IN HYPERTENSIVE PATIENTS

It seems clear that glycemic adverse events occur with certain beta-blockers or thiazide diuretics, at least to some extent. However, it is not known whether these adverse effects are responsible for new cases of diabetes in patients who would have otherwise remained euglycemic, or whether the additional cases are observed in those who are already predisposed to developing diabetes. In the latter case, the incremental cardiovascular risk may be small because predisposed patients, such as those with metabolic syndrome, already have a constellation of risk factors that confer a significant cardiovascular risk, even when their sugar concentrations are below the diabetic range (50). This theory would explain why differences in new-onset diabetes rates became smaller over the course of the ALLHAT study (51). In the other scenario, the consequences of new-onset diabetes may also be small if new cases of diabetes are a result of isolated blood sugar elevations without the associated metabolic abnormalities, such as dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and abdominal obesity.

Few studies have attempted to evaluate the consequences of glycemic adverse effects caused by antihypertensive medications. Of the available reports, none have reduced confounding factors sufficiently to allow for firm conclusions about the danger of this adverse effect. Dunder et al (14) found that elevated levels of blood glucose were an independent predictor of myocardial infarction in patients receiving antihypertensive therapy, but not in normotensive patients. Although the authors controlled for several important confounders, the effect of antihypertensive medication was not clearly distinguished from hypertension because the control group was normotensive. Verdecchia et al (15) also found a link between new-onset diabetes and cardiovascular events. In their observational study of hypertensive patients, the cardiovascular event rate of those developing new-onset diabetes during antihypertensive therapy was almost identical to those patients with established diabetes at baseline. Both groups (new-onset and established diabetes) exhibited cardiovascular event rates that were significantly higher than the rate for patients who remained euglycemic. Assuming that many of these patients exhibited signs of the metabolic syndrome, it is not surprising their cardiovascular risk was high, even before the development of diabetes. In contrast, long-term follow-up results of a previously published clinical trial comparing chlorthalidone with placebo (SHEP) suggested that new-onset diabetes occurring during active therapy was not associated with increased mortality over a period of 14 years (16). Data from this report are also preliminary because drug use was unknown for the majority of the follow-up period.

SUMMARY

There is evidence indicating that thiazide diuretics and certain beta-blockers exhibit adverse glycemic effects. In theory, these effects may be associated with an accelerated risk for cardiovascular events in the long term, beyond the follow-up of prospective clinical trials. However, the extent to which these adverse effects increase long-term cardiovascular safety remains theoretical, and the mechanisms have not been confirmed. Furthermore, avoiding valuable antihypertensive agents like thiazide diuretics may be risky if this means delaying the time taken to achieve BP control. A recently published trial (43) provides evidence for the importance of prompt control of BP, and we have found that low-dose thiazides, at least in combination, are often required to achieve BP control in the majority of our patients. Accordingly, avoidance of thiazides could delay or prevent adequate BP control in many patients and unnecessarily increase cardiovascular risk over the short term. As for the long-term consequences of glycemic adverse effects, it is our view that these effects are small and limited to blood glucose only. It is doubtful to us that these effects influence the constellation of metabolic risk factors that play a significant role in a patient’s cardiovascular risk. Future prospective trials may shed more light on the consequences of antihypertensive-induced glycemic effects and their complications; however, current evidence suggests that prompt BP control with established agents is of paramount importance.

Footnotes

NOTE: Since the acceptance of this manuscript, the results of Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial – Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA) (52) have been published. In this prospective study, almost 20,000 hypertensive patients were randomly assigned to either a beta-blocker/thiazide diuretic or a calcium channel blocker/ACEI-based regimen. During a median follow-up of 5.5 years, the beta-blocker/thiazide group developed new-onset diabetes at a higher rate than the calcium channel blocker/ACEI group (8.3% versus 5.9%, respectively [hazard ratio 0.70, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.78, P<0.0001]). However, blood glucose elevations were not associated with increased mortality and morbidity over the length of the trial. These findings are consistent with previously published reports described in the present article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Savage PJ, Pressel SL, Curb JD, et al. Influence of long-term, low-dose, diuretic-based, antihypertensive therapy on glucose, lipid, uric acid, and potassium levels in older men and women with isolated systolic hypertension: The Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:741–51. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.7.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahlof B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Schersten B, Ekbom T, Wester PO. Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension (STOP-Hypertension) Lancet. 1991;338:1281–5. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92589-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansson L, Lindholm LH, Niskanen L, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition compared with conventional therapy on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in hypertension: The Captopril Prevention Project (CAPPP) randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:611–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)05012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown MJ, Palmer CR, Castaigne A, et al. Morbidity and mortality in patients randomised to double-blind treatment with a long-acting calcium-channel blocker or diuretic in the International Nifedipine GITS study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT) Lancet. 2000;356:366–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02527-7. (Erratum in 2000;356:514) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber MA, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Blood pressure dependent and independent effects of antihypertensive treatment on clinical events in the VALUE Trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2049–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black HR, Elliott WJ, Grandits G, et al. CONVINCE Research Group. Principal results of the Controlled Onset Verapamil Investigation of Cardiovascular End Points (CONVINCE) trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2073–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288:2981–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. (Erratum in 2003;289:178) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evidenced Based Recommendations Task Force of the Canadian Hypertension Education Program. 2005 Canadian Hypertension Education Program Recommendations: The bottom line version. < http://www.hypertension.ca/recommendations_2005/execsummary2005.pdf> (Version current at January 13, 2006)

- 10.American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, American College of Endocrinology. Medical guidelines for the management of diabetes mellitus: The AACE system of intensive diabetes self-management – 2002 update. Endocr Pract. 2002;8(Suppl 1):40–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nathan DM. Clinical practice. Initial management of glycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1342–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp021106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Karasik A, Laakso M STOP-NIDDM Trail Research Group. Acarbose for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus: The STOP-NIDDM randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2072–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08905-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunder K, Lind L, Zethelius B, Berglund L, Lithell H. Increase in blood glucose concentration during antihypertensive treatment as a predictor of myocardial infarction: Population based cohort study. BMJ. 2003;326:681. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verdecchia P, Reboldi G, Angeli F, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of new diabetes in treated hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2004;43:963–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000125726.92964.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kostis JB, Wilson AC, Freudenberger RS, Cosgrove NM, Pressel SL, Davis BR SHEP Collaborative Research Group. Long-term effect of diuretic-based therapy on fatal outcomes in subjects with isolated systolic hypertension with and without diabetes. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fodor JG, Frohlich JJ, Genest JJ, Jr, McPherson PR. Recommendations for the management and treatment of dyslipidemia. Report of the Working Group on Hypercholesterolemia and Other Dyslipidemias. CMAJ. 2000;162:1441–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padwal R, Laupacis A. Antihypertensive therapy and incidence of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:247–55. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reaven GM, Lithell H, Landsberg L. Hypertension and associated metabolic abnormalities – the role of insulin resistance and the sympathoadrenal system. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:374–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602083340607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fogari R, Zoppi A, Preti P, Fogari E, Malamani G, Mugellini A. Differential effects of ACE-inhibition and angiotensin II antagonism on fibrinolysis and insulin sensitivity in hypertensive postmenopausal women. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14:921–6. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyazaki Y, Murakami H, Hirata A, et al. Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor temocapril on insulin sensitivity and its effects on renal sodium handling and the pressor system in essential hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 1998;11:962–70. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollare T, Lithell H, Selinus I, Berne C. Sensitivity to insulin during treatment with atenolol and metoprolol: A randomised, double blind study of effects on carbohydrate and lipoprotein metabolism in hypertensive patients. BMJ. 1989;298:1152–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6681.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter SJ, Harper R, Ennis CN, et al. Effects of combination therapy with an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and thiazide diuretic on insulin action in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1998;16:103–9. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helgeland A, Leren P, Foss OP, Hjermann I, Holme I, Lund-Larsen PG. Serum glucose levels during long-term observation of treated and untreated men with mild hypertension. The Oslo study. Am J Med. 1984;76:802–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90990-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reneland R, Alvarez E, Andersson PE, Haenni A, Byberg L, Lithell H. Induction of insulin resistance by beta-blockade but not ACE-inhibition: Long-term treatment with atenolol or trandolapril. J Hum Hypertens. 2000;14:175–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominguez LJ, Barbagallo M, Jacober SJ, Jacobs DB, Sowers JR. Bisoprolol and captopril effects on insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity in essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:1349–55. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harper R, Ennis CN, Sheridan B, Atkinson AB, Johnston GD, Bell PM. Effects of low dose versus conventional dose thiazide diuretic on insulin action in essential hypertension. BMJ. 1994;309:226–30. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6949.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gress TW, Nieto FJ, Shahar E, Wofford MR, Brancati FL. Hypertension and antihypertensive therapy as risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:905–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan JC, Cockram CS, Critchley JA. Drug-induced disorders of glucose metabolism. Mechanisms and management. Drug Saf. 1996;15:135–57. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199615020-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lundgren H, Bjorkman L, Keiding P, Lundmark S, Bengtsson C. Diabetes in patients with hypertension receiving pharmacological treatment. BMJ. 1988;297:1512. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6662.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mykkanen L, Kuusisto J, Pyorala K, Laakso M, Haffner SM. Increased risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in elderly hypertensive subjects. J Hypertens. 1994;12:1425–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samuelsson O, Hedner T, Berglund G, Persson B, Andersson OK, Wilhelmsen L. Diabetes mellitus in treated hypertension: Incidence, predictive factors and the impact of non-selective beta-blockers and thiazide diuretics during 15 years treatment of middle-aged hypertensive men in the Primary Prevention Trial Goteborg, Sweden. J Hum Hypertens. 1994;8:257–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. Propranolol or hydrochlorothiazide alone for the initial treatment of hypertension. IV. Effect on plasma glucose and glucose tolerance. Hypertension. 1985;7:1008–16. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.7.6.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Padwal R, Mamdani M, Alter DA, et al. Antihypertensive therapy and incidence of type 2 diabetes in an elderly cohort. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2458–63. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haenni A, Lithell H. Treatment with a beta-blocker with beta 2-agonism improves glucose and lipid metabolism in essential hypertension. Metabolism. 1994;43:455–61. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lithell H, Pollare T, Vessby B. Metabolic effects of pindolol and propranolol in a double-blind cross-over study in hypertensive patients. Blood Press. 1992;1:92–101. doi: 10.3109/08037059209077499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacob S, Rett K, Wicklmayr M, Agrawal B, Augustin HJ, Dietze GJ. Differential effect of chronic treatment with two beta-blocking agents on insulin sensitivity: The carvedilol-metoprolol study. J Hypertens. 1996;14:489–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bakris GL, Fonseca V, Katholi RE, et al. GEMINI Investigators. Metabolic effects of carvedilol vs metoprolol in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:2227–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.18.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Report of Medical Research Council Working Party on Mild to Moderate Hypertension. Adverse reactions to bendrofluazide and propranolol for the treatment of mild hypertension. Lancet. 1981;2:539–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sowers JR. Effects of calcium antagonists on insulin sensitivity and other metabolic parameters. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:24–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Cooper-DeHoff RM, et al. INVEST Investigators. A calcium antagonist vs a non-calcium antagonist hypertension treatment strategy for patients with coronary artery disease. The International Verapamil-Trandolapril Study (INVEST): A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2805–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.21.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, et al. VALUE trial group. Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: The VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2022–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, et al. CHARM Investigators and Committees. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: The CHARM-Alternative trial. Lancet. 2003;362:772–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Malmqvist K, Kahan T, Isaksson H, Ostergren J. Regression of left ventricular mass with captopril and metoprolol, and the effects on glucose and lipid metabolism. Blood Press. 2001;10:101–10. doi: 10.1080/08037050152112087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fogari R, Zoppi A, Corradi L, Lazzari P, Mugellini A, Lusardi P. Comparative effects of lisinopril and losartan on insulin sensitivity in the treatment of non diabetic hypertensive patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:467–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fogari R, Zoppi A, Lazzari P, et al. ACE inhibition but not angiotensin II antagonism reduces plasma fibrinogen and insulin resistance in overweight hypertensive patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;32:616–20. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199810000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dahlof B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. LIFE Study Group. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): A randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2005;365:1415–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whelton PK, Barzilay J, Cushman WC, et al. ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Clinical outcomes in antihypertensive treatment of type 2 diabetes, impaired fasting glucose concentration, and normoglycemia: Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1401–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dahlof B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. ASCOT Investigators. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): A multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]