Abstract

The N-end rule is a degradation pathway conserved from bacteria to mammals that links a protein's stability in vivo to the identity of its N-terminal residue. In Escherichia coli, the components of this pathway directly responsible for protein degradation are the ClpAP protease and its adaptor ClpS. We recently demonstrated that ClpAP is able to recognize N-end motifs in the absence of ClpS although with significantly reduced substrate affinity. In this study, a systematic sequence analysis reveals new features of N-end rule degradation signals. To achieve specificity, recognition of an N-end motif by the protease-adaptor complex uses both the identity of the N-terminal residue and a free α-amino group. Acidic residues near the first residue decrease substrate affinity, demonstrating that the identity of adjacent residues can affect recognition although significant flexibility is tolerated. However, shortening the distance between the N-end residue and the stably folded portion of a protein prevents degradation entirely, indicating that an N-end signal alone is not always sufficient for degradation. Together, these data define in vitro the sequence and structural requirements for the function of bacterial N-end signals.

Regulated proteolysis is fundamental for cellular survival because it provides an irreversible control mechanism. For example, progression through the eukaryotic cell cycle requires timely turnover of cyclins to synchronize and order specific events, such as DNA replication and chromosome segregation (1). Proteolysis also initiates the SOS response to DNA damage in bacteria via degradation of the transcriptional repressor LexA (2, 3), thereby allowing expression of repair polymerases and checkpoint proteins (4). Defective protein turnover can initiate events as diverse as loss of competence in Bacillus subtilis (5) and angiogenesis via Hif1 (hypoxia-inducible factor) in mammals (6). The importance of proteolysis as a regulatory mechanism highlights the need to understand the mechanisms by which these proteases select the right substrates and avoid unintended protein destruction.

Energy-dependent proteases are composed of an oligomeric ATP-dependent unfolding enzyme and an enclosed proteolytic chamber (7). The architecture of this chamber requires that substrates pass through an axial entry gate that is too narrow to allow entry of folded proteins. The unfoldase harnesses the energy of ATP hydrolysis to drive mechanical unfolding of protein substrates and to translocate the resultant denatured polypeptide into the proteolytic chamber for peptide bond cleavage (8–10). In Escherichia coli, there are several proteolytic complexes; for example, the ClpX and ClpA ATPases unfold substrates and translocate the polypeptide chains into the ClpP proteolytic chamber for degradation (11–13).

Known bacterial degradation signals vary in sequence complexity and in length from a few amino acids to roughly 10 residues (14). Adaptor proteins also confer or enhance recognition by binding both the substrate and the unfoldase. For example, one region of the SspB adaptor binds to the ClpX unfoldase, and another domain recognizes a region of the ssrA degradation tag, facilitating tethering of ssrA-tagged substrates to ClpXP and the probability of productive engagement (15, 16). SspB and ClpX can bind the ssrA tag simultaneously, allowing SspB to hand off substrates to ClpX directly (17). The sequence determinants for the ssrA-SspB and ssrA-ClpX interactions have been characterized both structurally and biochemically (15, 18, 19). In contrast, the mechanism of adaptor-mediated delivery for substrates to ClpAP is not well understood.

ClpS is a multifaceted adaptor, which enhances ClpAP turnover of N-end rule substrates but also prevents ClpAP from degrading other classes of substrates (20–24). Because ClpS possesses both stimulatory and inhibitory activities, it can change the profile of ClpAP degradation dramatically. The evolutionarily conserved N-end rule relates the intracellular half-life of a protein to its N-terminal residue (25–27). In bacteria, proteins beginning with any of the three aromatic amino acids (Phe, Tyr, or Trp) or the aliphatic residue Leu are degraded by ClpAP with assistance from ClpS (21). Side chain hydrophobicity per se is not sufficient for N-end rule recognition, since Ile, Val, and Met do not target substrates for ClpAP degradation. Substrates with the same N-end rule residue but different adjacent sequences are also degraded with varying rates in vivo, indicating that residues beyond the N terminus affect degradation in the bacterial N-end rule (22). It is known that ClpS binds directly to both ClpAP and N-end rule substrates to enhance protein turnover. ClpAP also shows weak affinity for N-end substrates in the absence of ClpS. These observations raise several questions about the mechanism of N-end rule substrate recognition by ClpA and ClpS. What is the molecular basis of the sequence signal that determines how efficiently an N-end motif is recognized? What are the individual contributions of ClpA and ClpS in degrading N-end motif substrates?

To address these questions, we mutagenized an N-end pentapeptide (YLFVQ) that efficiently targets substrates for ClpAP degradation (22) and assayed the effects on in vitro degradation of GFP4 fusion proteins by ClpAP in the presence and absence of ClpS. We confirmed the importance of N-terminal Leu, Tyr, Trp, or Phe residues for robust ClpAPS degradation (26). Competition experiments also established that modification of the α-amino group substantially diminished ClpAPS recognition. The N-end rule thus uses the combination of the N-terminal residue's side chain and the α-amino group as the principal recognition determinants of the degradation signal. The positive contributions of these two determinants are antagonized by the presence of acidic residues adjacent to the motif, demonstrating that sequence adjacent to the N-terminal residue influences recognition by ClpAPS. Furthermore, N-end signals are not sufficient to promote degradation if the distance between the folded region of the protein and the N-terminal residue is too short, indicating that there is also a structural component to the N-end rule. Examination of individual contributions of ClpS and ClpAP revealed that ClpS bound poorly to acidic N-end motifs but well to short N-end motifs, whereas ClpAP degraded some acidic N-end substrates efficiently but could not degrade short N-end motifs. We conclude that both ClpS and ClpA are important in determining the efficacy of N-end substrate processing. These results dissect the bacterial N-end rule into components that are important for recognition in vitro and show how the presence of ClpS alters the sequence selectivity of ClpAP.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Proteins—GFP variants (GFPuv with serine at position 65 changed to threonine) and Y-titin were cloned into a pET23b.smt3 vector using AgeI and NotI sites (22). The N-terminal sequences of GFP variants are shown in Fig. 5A; “ASK” initiates the GFP sequence.

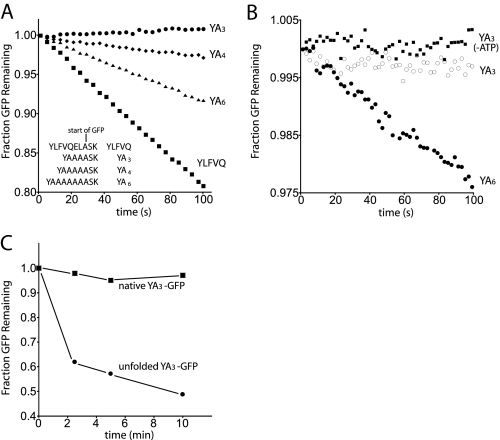

FIGURE 5.

ClpAPS requires a minimum tag length to degrade N-end motifs. A, degradation is reduced as the tag length is shortened. 10 nm GFP was incubated with 50 nm ClpAPS, and loss of GFP fluorescence was followed over time. B, YA3-GFP is not degraded at 8 μm using 100 nm ClpAPS. YA6-GFP (8 μm) is shown for comparison. C, unfolded but not native YA3-GFP is degraded rapidly by 800 nm ClpAPS. Protein was visualized by staining with Sypro Orange dye (Molecular Probes) and detecting fluorescence at 555 nm on a Typhoon imager.

For protein expression, substrates were subcloned into the isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside-inducible vector pET23b.his6-smt3 (pET23b from Novagen) and transformed into E. coli strain BL21 λDE3 (28). His6-SUMO-GFP fusions were purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic aid affinity chromatography as described (28) and were >85% pure. Most contaminants were His6-SUMO or full-length His6-SUMO-GFP. Some GFP variants were purified to >95% purity, using a low substitution phenyl-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) but were degraded at the same rate as GFP proteins not processed with this second purification step. ClpA, ClpP, ClpS, and 35S-YLFVQ-titin were purified as described (11, 20, 22, 23, 29). GFP (100 μm) was acid-denatured by adding hydrochloric acid to 25 mm for 5 min at room temperature (30).

GFP Degradation Assays—Loss of GFP fluorescence in degradation assays was monitored using a Photon Technology International fluorimeter (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 511 nm). ClpA6 (50 nm), (ClpP-His6)14 (100 nm), ClpS (450 nm), and GFP substrate (10 nm) were premixed as described at 30 °C (12). For degradation reactions lacking ClpS, 100 nm ClpA6 and 200 nm ClpP14 were used. In Fig. 3, GFP concentrations from 50 nm to 16 μm were used. To initiate degradation, ATP (4 mm) was added at time 0. Initial changes in fluorescence were calculated from the linear portion of the kinetic trace, typically over the first 3 min, and converted to initial rates of GFP protein degradation using a linear standard curve relating fluorescence at 511 nm to GFP concentrations. For determination of steady-state kinetic parameters in Fig. 3, the average initial rates from three independent experiments were plotted as a function of the total substrate concentration. Since [GFP substrate] was not always in excess of [ClpAPS], the data were fitted (R2 > 0.95) by a nonlinear least squares algorithm to a quadratic version of the Michaelis-Menten equation.

|

(Eq. 1) |

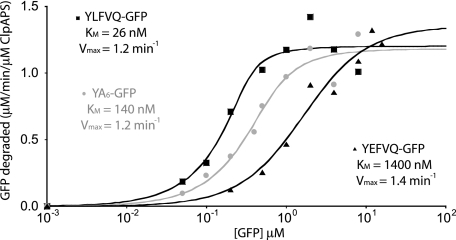

FIGURE 3.

The inhibition by acidic residues is caused by a reduction in affinity but not catalytic processing. Michaelis-Menten plot of initial degradation rates of YLFVQ-GFP at various GFP concentrations using 50 nm ClpAPS. The data represent the average of three experiments. YEFVQ-GFP is degraded with a 50-fold higher Km but with a similar Vmax.YA6-GFP is degraded efficiently by ClpAPS but with a Km value 6-fold higher than that of YLFVQ-GFP. Correlation coefficients (R2) for all three curve fits were greater than 0.95.

Degradation reactions of unfolded GFP were performed using ClpA6 (800 nm), (ClpP-His6)14 (1.6 μm), and ClpS (4.8 μm). ATP regeneration mixture (4 mm ATP, 50 mg/ml creatine kinase, and 5 mm creatine phosphate) was added prior to the addition of unfolded GFP, and the reaction was incubated at 30 °C for 2 min. Unfolded YA3-GFP (1.5 μm) was added at time 0 to initiate the reaction. At each time point, 10 μl of reaction mix was quenched by adding 2.5 μl of SDS loading buffer on ice. Samples were boiled and electrophoresed on a 15% Tris-glycine gel, which was stained with Sypro Orange (Molecular Probes) at a 1:5000 dilution in 7.5% acetic acid and scanned on a Typhoon 9400 imager (excitation, 488 nm; detection, 555 nm). Quantification was performed with ImageQuant 4.0, and intensities were normalized to the ClpP intensity in each lane. Three independent experiments were performed. A representative gel and quantification are shown in Fig. 5C.

Peptide Competition Assays—Peptide competition assays were performed by assaying loss of YLFVQ-GFP fluorescence. β-Galactosidase peptides were synthesized by the MIT Biopolymers facility and contained the first 21 residues of β-galactosidase fused to different N-terminal residues. These peptides were added to a final concentration of 50 μm in reactions containing 50/100/450 nm ClpA/P/S and 500 nm YLFVQ-GFP; degradation was started by adding ATP.

The YLFVQR peptide was acetylated by incubating 1 mm peptide in 10 mm Tris (pH 8.9) with 200 mm acetic anhydride overnight at room temperature. Acetyl-YLFVQR was purified by HPLC, lyophilized, and resuspended in H2O. The addition of a single acetyl group was verified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Acetyl-YLFVQR or unmodified YLFVQR peptide was added to degradation reactions containing 50/100/450 nm ClpA/P/S, 35 nm YLFVQ-GFP, and 3.3 or 6.6 μm peptide. The initial degradation rate in the absence of peptide was normalized to 1, and degradation rates in the presence of peptide competitor were determined relative to the initial rate and averaged (n = 3).

Fluorescent Labeling of Peptides—Peptides with the sequence H2N-XLFVQYH6C (where X represents different N-terminal residues) were synthesized using an Apex 396 solid phase instrument, dissolved in 100 mm Tris (pH 7.5), and incubated with 5 μg/ml maleimide-fluorescein (Pierce) for 2 h at room temperature. Fluorescein-labeled peptides were purified by HPLC, lyophilized, and resuspended in water. Fluorescence anisotropy was measured at 30 °C (excitation, 495 nm; emission, 520 nm) using 1.4 μm fluorescinated peptide and 1.4 μm ClpS.

Protein Competition Assays—Samples containing 50/100/450 nm ClpA/P/S and 2 μm 35S-YLFVQ-titin were premixed with GFP competitor substrate (10 μm except for untagged GFP (a gift of P. Chien), which was used at 40 μm). Degradation was initiated by the addition of 4 mm ATP, and 10-μl aliquots were withdrawn every 30 s and quenched by the addition of 10% trichloroacetic acid. Degradation rates were determined from the time-dependent accumulation of radiolabeled trichloroacetic acid-soluble peptides (11).

Surface Plasmon Resonance—ClpS binding experiments were performed using a Biacore 3000 instrument. ClpS was covalently bonded to a CM5 chip surface by amine coupling using the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. A 300-response unit surface of immobilized ClpS was used for the binding studies, and another flow cell immobilized with 7000 response units of anti-ClpS antibody was used as a nonspecific binding control surface. GFP (440 nm) binding injections of 400 s were performed at a 30-μl/min flow rate in running buffer (20 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 20 mm MgCl2, and 0.005% P20 surfactant). Each GFP injection was preceded by an identical buffer injection whose composition matched that of the GFP solution. The GFP-ClpS interaction responses were double-referenced by subtracting the SPR signal from the GFP injection over the control flow cell as well as the signal from the buffer injection over the ClpS surface.

RESULTS

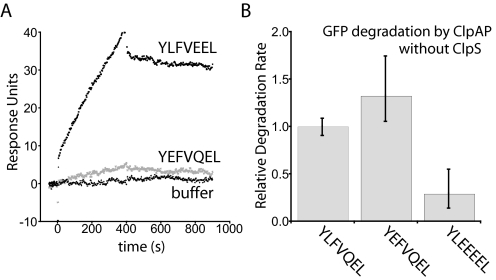

Specific Side Chains at the N-terminal Residue Are Critical for Recognition—To allow the N-terminal sequence of a model substrate (GFP) to be modified without constraints imposed by translational initiation or post-translational processing, we constructed and purified variants as His6-SUMO-X7-GFP fusions, cleaved these proteins with SUMO protease (28), and repurified the X7-GFP molecule to remove the protease and His6-SUMO fragment. The strong N-end motif YLFVQEL was used as a reference X7 sequence (22); the glutamate-leucine was encoded by a SacI restriction site to facilitate cloning. Variants with the first Tyr replaced by other N-end rule residues (Phe, Leu, or Trp), by aliphatic side chains (Ile or Val), or by Thr were also constructed and purified. At low substrate concentrations where the rate of degradation by ClpAPS (ClpAP plus ClpS) was determined by the second order rate constant (kcat/Km), only the N-end rule substrates were degraded efficiently (Fig. 1A) (data not shown), consistent with the reported selectivity of the N-end rule (26). Among good substrates, the variant with Phe at the N terminus was degraded most rapidly, whereas the variant with Tyr was degraded at the slowest rate. This difference arose from a ∼20% reduction in Km but not Vmax (not shown), suggesting modest differences in recognition of N-end residues by ClpAPS.

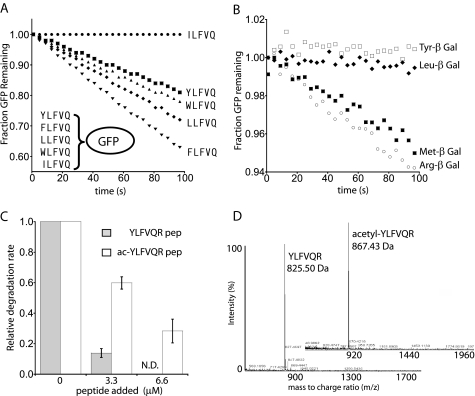

FIGURE 1.

The N-end rule depends on the identity of the first residue and the α-amino group. A, N-end GFP constructs are degraded, whereas the non-N-end ILFVQ-GFP is not. 50 nm ClpAPS was incubated with 10 nm GFP, and loss of GFP fluorescence was followed by excitation at 488 and detection at 511 nm. B, peptide competition of YLFVQ-GFP (500 nm) degradation by 50 nm ClpAPS. β-Galactosidase peptides (50 μm) with different N-terminal residues were added before initiation of degradation. C, peptide competition of YLFVQ-GFP (35 nm) degradation by 50 nm ClpAPS. YLFVQR peptide with a free or acetylated α-amino group (Ac-YLFVQR) was added before initiation of degradation, and rates were normalized to that of a reaction lacking peptide. N.D., the reaction using 6.6 μm YLFVQR peptide competitor was not performed. D, MALDI-TOF spectra of unmodified versus acetylated YLFVQR peptide.

As another probe of the importance of the N-terminal residue, we assayed ClpAPS degradation of YLFVQEL-GFP in the presence of a large excess of peptide competitor consisting of a variable N-terminal residue followed by the first 21 residues of E. coli β-galactosidase. Efficient competition was observed when the N-end rule residues Tyr or Leu were at the N terminus but not when Met or Arg occupied this position (Fig. 1B). Therefore, both direct degradation and competition assays can be applied to probe the sequence rules of the N-end signal.

The α-Amino Group Is a Recognition Element of the N-end Rule—The purified precursor His6-SUMO-YLFVQEL-GFP protein was not degraded by ClpAPS (not shown), suggesting that the lack of a free N-terminal Tyr and/or the presence of “upstream” residues prevents recognition. To test the importance of a free α-amino group, we compared inhibition of ClpAPS degradation of YLFVQEL-GFP by the hexapeptide YLFVQR before and after blocking its N terminus by treatment with acetic anhydride. The unmodified peptide was a good inhibitor, whereas competition by the acetylated peptide was reduced substantially but not eliminated (Fig. 1C). The latter result was not caused by incomplete acetylation, since MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry before and after chemical modification gave single species of the expected masses (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that the α-amino group is an important feature but is not an essential component of the N-end signal.

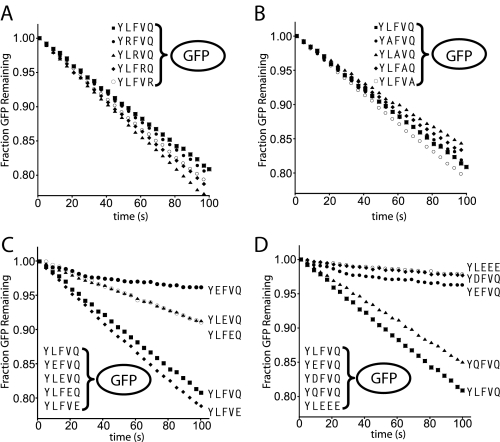

Acidic Residues near the N-end Residue Weaken ClpAPS and ClpS Binding—We previously found that substrates with the same N-end residue but different neighboring sequences were degraded with different Km values, suggesting that residues beyond the N terminus affect functional interactions with ClpAPS (22). To probe whether these effects are caused by packing or electrostatic interactions, we individually changed residues 2, 3, 4, and 5 of YLFVQEL-GFP to a basic residue (Arg), a small residue (Ala), or an acidic residue (Glu). When low concentrations of these substrates were tested for ClpAPS degradation, the Arg and Ala variants were degraded at rates similar to YLFVQEL-GFP (Fig. 2, A and B), indicating that ClpAPS does not require specific side chains at positions 2–5 for efficient N-end degradation. By contrast, changing residue 2, 3, or 4 to Glu slowed degradation (Fig. 2C), with the largest effect observed when Glu was adjacent to the N-end residue. Indeed, replacing residue 2 with either Glu or Asp slowed degradation more than 10-fold, whereas changing this residue to Gln had only a small effect (Fig. 2D). Thus, the negative charge and not the shape of the position 2 side chain causes poor degradation by ClpAPS. A variant with residues 3–5 replaced by Glu (YLEEEEL-GFP) was degraded very slowly, suggesting that a net negative charge near the N-end residue is poorly tolerated by ClpAPS (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Acidic residues near the N-end residue slow degradation. Single Arg (A) or Ala (B) variants have negligible effects on GFP degradation. Initial rates of degradation for 10 nm GFP by 50 nm ClpAPS are shown. C, inhibition of N-end substrate degradation by an acidic residue is stronger when placed closer to the N terminus. D, an acidic residue but not Gln at position 2 or multiple Glu residues at positions 3–5 inhibits degradation.

To determine if the deleterious effects of acidic residues arose from poor substrate binding or slower turnover by ClpAPS, we determined steady-state kinetic parameters for the parental substrate YLFVQEL-GFP (Km = 26 nm; Vmax = 1.2 min-1) and for YEFVQLE-GFP (Km = 1400 nm; Vmax = 1.4 min-1) (Fig. 3). These results show that the principal effect of the Leu2→Glu substitution is an approximately 50-fold weakening of apparent affinity of the substrate for ClpAPS. We conclude that acidic side chains at residues 2–4 of N-end degradation signals interfere with ClpAPS binding but not processing. The “N-end receptor sites” in ClpS and/or ClpA may have a negative electrostatic potential that interacts unfavorably with negatively charged residues in the N-end signal.

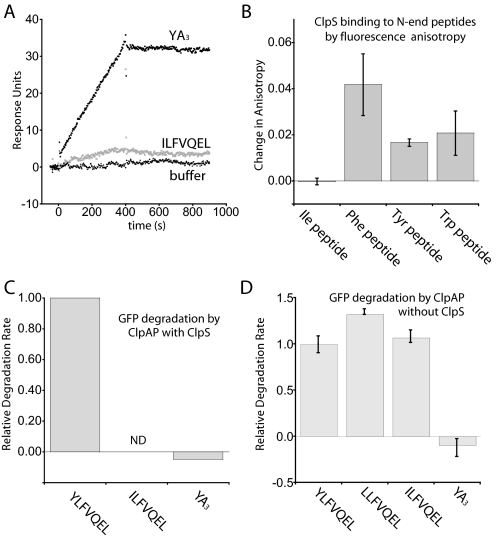

To examine the relative affinity of ClpS for acidic N-end signals, surface plasmon resonance was used to monitor binding of immobilized ClpS to YEFVQEL-GFP and YLFVEEL-GFP. The YEFVQEL-GFP protein, which was degraded slowly by ClpAPS, also bound poorly to ClpS (Fig. 4A). By contrast, YLFVEEL-GFP has the same net charge but was degraded 6-fold more rapidly by ClpAPS (Fig. 2C) and bound well to ClpS. These results show that acidic residues near the N-end residue influence ClpAPS degradation, at least in part, by weakening ClpS binding and also demonstrate that ClpS binding affinity is correlated with ClpAPS degradation activity of acidic N-end substrates.

FIGURE 4.

A single Glu mutation in position 2 decreases affinity with ClpS but not ClpAP. A, ClpS binds poorly to YEFVQEL-GFP but well to YLFVEEL-GFP by surface plasmon resonance. ClpS was immobilized to the chip surface, and each GFP substrate was injected from time 0 to 400 s. The buffer curve is a comparison of responses of the chip surface from two separate buffer injections. B, degradation of acidic GFP constructs by 100 nm ClpAP without ClpS. Initial rates were normalized to that of YLFVQEL-GFP, and the error bars show the error range of three independent reactions.

Is this ClpS binding defect entirely responsible for the slow degradation of YEFVQEL-GFP by ClpAPS? ClpAP can degrade N-end substrates without ClpS, but with 10–70-fold weaker apparent affinity than ClpAPS, depending on the sequence of the N-end signal (22). We found that ClpAP degraded both YEFVQEL-GFP and YLFVQEL-GFP at similar rates, indicating that ClpAP itself is not inhibited by an acidic residue at position 2 (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the presence of several acidic residues (YLEEEEL-GFP) near the N-end residue slowed substrate degradation by ClpAP. These results indicate that acidic N-end signals affect ClpAPS and ClpAP recognition differently.

Length Determinants of N-end Signals—Erbse et al. (21) found that ClpAPS degraded GFP with an N-end Phe followed by a 10-residue linker but not when the N-terminal Phe was placed adjacent to GFP. In our YLFVQEL-GFP construct, the N-terminal Tyr is seven residues from the alanine that begins the GFP sequence (YLFVQELASK; the lysine begins the folded region of GFP). To address the role of linker length, we determined rates of ClpAPS degradation of constructs with six alanines between the N-terminal Tyr and the first residue of GFP (YA6-GFP) and variants with the linker reduced by two (YA4-GFP) or three residues (YA3-GFP). The YA6-GFP substrate was degraded by ClpAPS with a Km of 140 nm, a value 6-fold higher than the Km for YLFVQEL-GFP (Fig. 3). This result is consistent with a modest contribution of residues beyond the N terminus to ClpAPS interactions. The YA4-GFP substrate was degraded about 5-fold more slowly than YA6-GFP (Fig. 5A), showing that linker length influences degradation. No degradation of YA3-GFP was detected even at high substrate concentrations (Fig. 5B). Thus, GFP N-end tags that are too short pose a problem for ClpAPS.

To determine if this defect is due to the proximity of a folded domain adjacent to the YA3 N-end signal, YA3-GFP was acid-denatured prior to the addition into a degradation reaction containing ClpAPS. Unfolded YA3-GFP was degraded rapidly, whereas native YA3-GFP was not turned over even using increased ClpAPS concentrations (Fig. 5C). This result indicates that N-end signals are not effective degradation motifs when located too close to the folded N-terminal region of the substrate. To establish whether ClpS or ClpAP is responsible for this observation, experiments were designed to test the roles of both recognition modules.

Dissecting the Individual Contributions of ClpS and ClpAP to Substrate Recognition—In principle, ClpAPS might fail to degrade native YA3-GFP either because ClpS does not bind this protein and/or because ClpA cannot accept this protein from ClpS or cannot unfold it after transfer. In surface plasmon resonance assays, immobilized ClpS bound YLFVEEL-GFP and YA3-GFP to comparable extents but bound very poorly to ILFVQEL-GFP, a non N-end rule protein (Fig. 4A,6A). To verify that ClpS is selective for N-end residues, fluorescinated peptides with N-terminal Phe, Tyr, Trp, and Ile were incubated with ClpS, and fluorescence anisotropy was measured (Fig. 6B). All peptides except for the Ile variant produced an increase in anisotropy when ClpS was added, indicating that ClpS does not recognize an N-terminal Ile. Together, these data show that the inability of ClpAPS to degrade YA3-GFP does not arise from a ClpS binding defect (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

ClpS and ClpA have distinct recognition specificities that contribute to the overall degradation efficiency of N-end substrates. A, ClpS binds to the protein containing a short N-end signal YA3-GFP but not the non-N-end signal ILFVQEL-GFP by surface plasmon resonance. B, fluorescence anisotropy with labeled peptides shows that ClpS can distinguish Ile from the N-end residues Phe, Tyr, and Trp. Error bars show the error range of two independent trials. C, quantification of degradation of YLFVQEL-GFP, ILFVQEL-GFP, and YA3-GFP by ClpAPS from Fig. 2, A and C. Rates are normalized to that of YLFVQEL-GFP. ND, not detectable. D, degradation rates of LLFVQEL-GFP, ILFVQEL-GFP, and YA3-GFP by 100 nm ClpAP without ClpS. Initial rates were normalized to that of YLFVQEL-GFP, and the error bars show the error range of three independent reactions.

We determined rates of ClpAP degradation of YA3-GFP, ILFVQEL-GFP, LLFVQEL-GFP, and YLFVQEL-GFP in the absence of ClpS (Fig. 6D). Under these conditions, the non N-end substrate (ILFVQEL-GFP) was degraded at a rate similar to the two good N-end rule substrates (LLFVQEL-GFP and YLFVQEL-GFP). However, ClpAP did not degrade the short tag variant YA3-GFP (Fig. 6D). Thus, N-end residues located too close to the folded region of GFP do not serve as degradation signals for ClpAP or for ClpAPS.

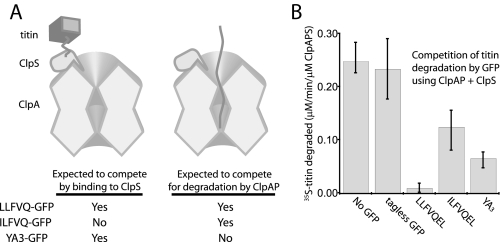

The preceding experiments suggest that the defect in YA3-GFP degradation arises after binding to ClpS. If this model is correct, then YA3-GFP should act as a competitor and inhibit ClpAPS degradation of another N-end rule substrate by blocking the N-end recognition site on ClpS. In contrast, because ILFVQEL-GFP is not recognized by ClpS but is degraded by ClpAP, this substrate may compete by occupying the degradation activity of ClpAP (Fig. 7A). Indeed, ClpAPS degradation of the characterized N-end substrate 35S-YLFVQMSHLA-titin (22) was inhibited by the addition of YA3-GFP, LLFVQEL-GFP, and ILFVQEL-GFP but not by tagless GFP (Fig. 7B). LLFVQEL-GFP was a much better competitor than YA3-GFP or ILFVQEL-GFP. These results can be rationalized if LLFVQEL-GFP competes with the 35S-substrate for binding ClpS but also competes for a binding site in ClpAP, thereby inhibiting both initial recognition and subsequent unfolding and degradation by ClpAP. By contrast, ILFVQEL-GFP is a weaker inhibitor, because it only competes for ClpAP binding, and YA3-GFP is a weaker inhibitor, because it only competes for ClpS binding. Together with the results from Fig. 6, these data suggest that the efficiency of ClpAPS in degrading N-end rule substrates depends on recognition of the substrate by both ClpS and by ClpAP.

FIGURE 7.

Efficient competition is achieved by an N-end substrate that is recognized by ClpS and degraded by ClpAP. A, schematic predicting how different GFP substrates may compete with the N-end titin substrate used below. Binding to ClpS (orange) by GFP substrate blocks initial recognition of titin (gray), and degradation of GFP by ClpAP (light blue) prevents degradation of titin. B, inhibition of 35S-labeled YLFVQMSHLA-titin degradation using 50 nm ClpAPS and 10 μm GFP competitor substrate (40 μm in the case of tagless GFP). Degradation was quantified by counting the release of acid-soluble 35S-peptides over time. Error bars for the bar graphs show the range of initial rates for three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The original discovery of the bacterial N-end rule identified four N-terminal residues (Leu, Phe, Trp, and Tyr) that target β-galactosidase for degradation (26). It is now known that the ClpA unfoldase and the ClpS adaptor participate in recognition of N-end rule signals (21, 22, 26). The results presented here further define the molecular basis for N-end rule sequence selectivity and the roles of ClpA and ClpS in recognition.

We confirmed that the expected N-end residues mediated ClpAPS degradation of GFP variants with modest differences in efficiency in the order Phe > Leu > Trp > Tyr. By contrast, GFP with an N-terminal Ile showed no detectable ClpAPS degradation at low concentrations, where N-end rule substrates were efficiently degraded. Thus, ClpAPS recognition is highly selective, discriminating between side chains as similar as Leu and Ile. In addition to the N-terminal side chain, we find that a free α-amino group contributes to but is not essential for ClpAPS binding. This finding is consistent with studies showing that blocking the N terminus of an otherwise good N-end rule signal reduced ClpS binding on a peptide blot (21). ClpS is required for high affinity interactions with N-end rule substrates (21, 22), and we find that ClpS alone discriminates between substrates with good N-end rule residues and those with Ile at the N terminus. Thus, ClpS enhances the degradation of N-end substrates by ClpAP by recognizing the α-amino group in combination with a Leu, Phe, Trp, or Tyr side chain at the N terminus (Fig. 8A).

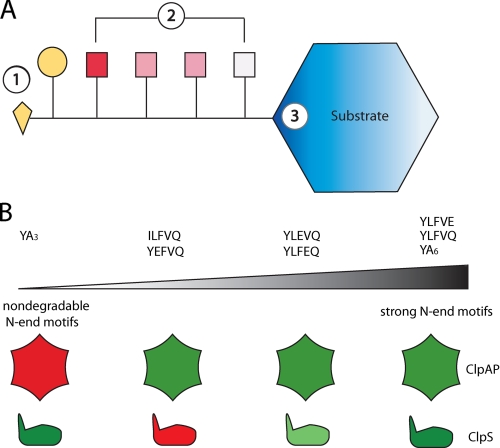

FIGURE 8.

A, components of an N-end signal. Recognition depends on the α-amino group and identity of the first residue (yellow diamond and circle, respectively; component 1) and is modulated by the neighboring amino acids (red and white squares; component 2). The residues immediately adjacent to the N-terminal residue modulate recognition more strongly than those further away. The structure of the folded region close to the N-end motif affects degradation of N-end substrates (blue; component 3). B, a gradient model for N-end motif strength. nondegradable N-end signals, such as YA3, are placed at the very left of the spectrum, and weak motifs are placed somewhere in the middle, depending on how efficiently they target substrates to ClpAPS for degradation. The relative affinities of ClpAP and ClpS to these degradation signals are represented by the red and green shapes below the spectrum. Red, negligible recognition; light green, moderate affinity; dark green, strong interaction.

Our results show that residues adjacent to the N-end residue influence the affinity of ClpAPS interactions. Specific side chains at these positions are not required. For example, changing the N-end signal of YLFVQEL-GFP to YAAAAAA-GFP increased the Km for degradation only 6-fold, indicating that residues make small contributions to apparent affinity. Notably, however, an acidic residue at position 2 (YEFVQEL-GFP) increased Km 50-fold; a variant with acidic residues at positions 3–5 (YLEEEEL-GFP) was also a very poor ClpAPS substrate. These effects are probably caused by repulsion between acidic residues in ClpAPS and those in these N-end signals, which is consistent with the slower in vivo degradation of substrates carrying acidic N-end sequences (22). Indeed, we found that ClpS alone bound YEFVQEL-GFP very poorly compared with YLFVEEL-GFP, and mutational studies suggest that Asp35 and Asp36 of ClpS form part of its binding site for N-end signals (21). Negative electrostatic potential in this binding site would help bind the positively charged α-amino group of N-end signals. Moreover, some endogenous N-end signals contain a basic residue at position 2, because aminoacyl transferase adds Leu or Phe to bacterial proteins with an N-terminal Lys or Arg (26). Hence, it seems likely that discrimination against acidic N-end sequences is a consequence of optimizing binding to N-end signals with an overall positive charge.

Importantly, our results and those of Erbse et al. (21) demonstrate that proteins with N-end signals bind ClpS but are not necessarily ClpAPS substrates. Specifically, in our work, ClpAPS and ClpAP did not degrade YA3-GFP, although ClpS bound this protein well. By contrast, ClpAPS degraded a variant with one extra residue between the N-end Tyr and GFP (YA4-GFP), although less rapidly than it degraded a substrate with a longer linker (YA6-GFP). Apparently, the distance between the N-end residue and the folded region of GFP must be sufficiently long to allow degradation, but this requirement is obviated when YA3-GFP is unfolded. This length dependence could arise because steric restrictions prevent access of short GFP N-end tags to a binding site in the ClpA hexamer. Alternatively, such tags might be engaged by ClpA but be too short to allow a strong enough grip to allow unfolding.

Based on our results, we propose that N-terminal sequences have a wide range of abilities to target native proteins for ClpAPS degradation (Fig. 8B). At one extreme are short tags like YA3, which do not target GFP for degradation, although they have an N-end residue and bind ClpS well. Next are tags like ILFVQEL that do not have an authentic N-end residue or acidic N-end signals, such as YEFVQEL, that do not bind ClpS but can be engaged by sites in ClpAP. In the middle of the spectrum are signals with N-end residues that that have weaker affinities for ClpAPS because of the presence of negatively charged residues; both the number and positions of acidic residues appear to determine precise affinity. At the other extreme are strong N-end signals, such as YLFVQEL, that allow efficient ClpAPS degradation at nanomolar substrate concentrations.

Our results also raise several questions regarding the eukaryotic N-end rule, which recognizes the additional N-end residues Ile (in some organisms), Arg, Lys, and His. The N-end signal receptor Ubr1 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that possesses a binding site for N-terminal Phe, Leu, Trp, Tyr, and Ile and a separate site for N-terminal Arg, Lys, and His (31). Interestingly, N-terminal Asp and Glu are recognized by the argininyl transferase Ate1p (32), which conjugates an Arg residue to these N termini. Is an N-terminal Arg residue recognized less efficiently when the second residue is acidic? If acidic residues in Ubr1 are important for docking the α-amino group and the Arg for this type of N-end signal, then electrostatic repulsion with acidic residues on the N-end signal may reduce binding affinity just as in the case of ClpS. Additionally, are shorter N-end sequences bound by Ubr1, and are these substrates ubiquitinated efficiently? Does the proteasome possess the same steric requirements for N-end signal length as ClpAP, although N-end substrates carry polyubiquitin chains as their proteasome localization determinants?

At present, it is not known how N-end substrates for ClpAPS are generated in the cell. Proteins with good N-end residues do not arise from translation and normal post-translational processing, because the initiator formyl-Met of proteins with second residues Phe, Leu, Trp, or Tyr is not removed by methionine aminopeptidase (33). The next challenge will be to isolate endogenous N-end substrates and to determine the extent and impact of sequence control in the N-end rule degradation.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Baker and Sauer laboratories for encouragement and helpful discussions, in particular J. Hou for purified ClpS protein, P. Chien for untagged GFP protein, and I. Levchenko and G. Roman for synthesizing peptides. We are grateful to C. Köhrer and U. Rajbhandary for use of the Biacore 3000 instrument and M. Pruteanu, A. Meyer, and S. Bell for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM-49224 and AI-16892. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: GFP, green fluorescent protein; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier; HPLC, high pressure liquid chromatography; MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight; E3, ubiquitin-protein isopeptide ligase.

References

- 1.Hershko, A. (1997) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 9788 -799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little, J. W. (1983) J. Mol. Biol., 167,791 -808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neher, S. B., Flynn, J. M., Sauer, R. T., and Baker, T. A. (2003) Genes Dev. 171084 -1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker, G. C., Marsh, L., and Dodson, L. (1985) Environ. Health Perspect. 62 115-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turgay, K., Hahn, J., Burghoorn, J., and Dubnau, D. (1998) EMBO J. 176730 -6738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willam, C., Masson, N., Tian, Y. M., Mahmood, S. A., Wilson, M. I., Bicknell, R., Eckardt, K. U., Maxwell, P. H., Ratcliffe, P. J., and Pugh, C. W. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 9910423 -10428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauer, R. T., Bolon, D. N., Burton, B. M., Burton, R. E., Flynn, J. M., Grant, R. A., Hersch, G. L., Joshi, S. A., Kenniston, J. A., Levchenko, I., Neher, S. B., Oakes, E. S., Siddiqui, S. M., Wah, D. A., and Baker, T. A. (2004) Cell 119 9-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benaroudj, N., Tarcsa, E., Cascio, P., and Goldberg, A. L. (2001) Biochimie (Paris) 83 311-318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh, S. K., Grimaud, R., Hoskins, J. R., Wickner, S., and Maurizi, M. R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 978898 -8903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, J., Hartling, J. A., and Flanagan, J. M. (1997) Cell 91447 -456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, Y. I., Burton, R. E., Burton, B. M., Sauer, R. T., and Baker, T. A. (2000) Mol. Cell 5 639-648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weber-Ban, E. U., Reid, B. G., Miranker, A. D., and Horwich, A. L. (1999) Nature 401 90-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gottesman, S., Roche, E., Zhou, Y., and Sauer, R. T. (1998) Genes Dev. 121338 -1347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flynn, J. M., Neher, S. B., Kim, Y. I., Sauer, R. T., and Baker, T. A. (2003) Mol. Cell 11 671-683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flynn, J. M., Levchenko, I., Seidel, M., Wickner, S. H., Sauer, R. T., and Baker, T. A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 9810584 -10589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wah, D. A., Levchenko, I., Rieckhof, G. E., Bolon, D. N., Baker, T. A., and Sauer, R. T. (2003) Mol. Cell 12 355-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolon, D. N., Grant, R. A., Baker, T. A., and Sauer, R. T. (2004) Mol. Cell 16 343-350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levchenko, I., Grant, R. A., Wah, D. A., Sauer, R. T., and Baker, T. A. (2003) Mol. Cell 12 365-372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song, H. K., and Eck, M. J. (2003) Mol. Cell 1275 -86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dougan, D. A., Reid, B. G., Horwich, A. L., and Bukau, B. (2002) Mol. Cell 9 673-683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erbse, A., Schmidt, R., Bornemann, T., Schneider-Mergener, J., Mogk, A., Zahn, R., Dougan, D. A., and Bukau, B. (2006) Nature 439753 -756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, K. H., Sauer, R. T., and Baker, T. A. (2007) Genes Dev. 21403 -408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katayama, Y., Gottesman, S., Pumphrey, J., Rudikoff, S., Clark, W. P., and Maurizi, M. R. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 26315226 -15236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hou, J. Y., Sauer, R. T., and Baker, T. A. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15 288-294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bachmair, A., Finley, D., and Varshavsky, A. (1986) Science 234179 -186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobias, J. W., Shrader, T. E., Rocap, G., and Varshavsky, A. (1991) Science 2541374 -1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Varshavsky, A. (1992) Cell 69 725-735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malakhov, M. P., Mattern, M. R., Malakhova, O. A., Drinker, M., Weeks, S. D., and Butt, T. R. (2004) J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 575 -86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenniston, J. A., Baker, T. A., Fernandez, J. M., and Sauer, R. T. (2003) Cell 114511 -520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoskins, J. R., Singh, S. K., Maurizi, M. R., and Wickner, S. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 978892 -8897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varshavsky, A. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 9312142 -12149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balzi, E., Choder, M., Chen, W. N., Varshavsky, A., and Goffeau, A. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 2657464 -7471 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flinta, C., Persson, B., Jornvall, H., and von Heijne, G. (1986) Eur. J. Biochem. 154193 -196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]