Abstract

The LAR transmembrane tyrosine phosphatase associates with liprin-α proteins and co-localizes with liprin-α1 at focal adhesions. LAR has been implicated in axon guidance and liprins are involved in synapse formation and synapse protein trafficking. Several liprin mutants have reduced binding to LAR as assessed by yeast interaction trap assays and the in vitro and in vivo phosphorylation of these mutants were reduced relative to wild-type liprin-α1. Treatment of liprin-α1 with calf intestinal phosphatase reduced its interaction with recombinant GST-LAR. A liprin LH region mutant that reduced liprin phosphorylation did not bind to LAR as assessed by co-precipitation studies. Endogenous LAR was shown to bind phosphorylated liprin-α1 from MDA-486 cells labeled in vivo with [32P]orthophosphate. In further characterizing the phosphorylation of liprin, immunoprecipitates of liprin-α1 expressed in COS-7 cells were found to incorporate phosphate after washes of up to 4M NaCl. Additionally, purified liprin-α1 derived from Sf-9 insect cells retained the ability to incorporate phosphate in in vitro phosphorylation assays and a liprin-α1 truncation mutant incorporated phosphate after denaturation/renaturation in SDS gels. Finally, binding assays showed that liprin binds ATP-agarose and that the interaction is competed by free ATP, but not by free GTP. Moreover, liprin LH region mutations that reduce liprin phosphorylation stabilized the association of liprin with ATP-agarose. Taken together, our results suggest that liprin autophosphorylation regulates its association with LAR.

The founding member of the liprin protein family, liprin-α1, was originally identified by virtue of its ability to bind the cytoplasmic phosphatase domains of the transmembrane tyrosine phosphatase LAR (1). Liprin-α1 is made up of a tail domain consisting of a long NH2-terminal α-helical coiled-coil segment followed by three tandem sterile alpha motif (SAM)1 domains and ends with a 100 amino acid segment which contains a binding site for the protein GRIP (1, 2). Liprin-α1 binds the LAR phosphatase domains via its SAM domains and yeast interaction trap screens using this region of liprin also isolated a homologous protein that was termed liprin-β1 (3). Ultimately an extensive protein family in mammals consisting of liprin-α's 1-4 and liprin-β's 1 and 2 was isolated (3) and liprins were also identified in Drosophila and C. elegans (4, 5). The part of liprin that contains the 3 SAM domains is highly conserved among all family members and is termed the liprin homology (LH) region. Liprin-α's bind via their LH regions to the intracellular phosphatase domains of LAR and the related phosphatases PTP δ and PTP σ (1, 6). Liprin-α's and liprin-β's also interact via their LH regions and liprins of each subclass homodimerize via their coiled-coil tail domains (3).

Liprin-α1 colocalizes with LAR at focal adhesions and liprin-α2 was shown to crosslink LAR on the cell surface, suggesting that liprins may be involved in regulating LAR localization within the cell (1, 3). More recently, liprin-α's have been shown to bind several proteins present in the “active zone” of neurons including KIF1A, the ERC family of RIM-binding proteins, RIM itself and GIT1 (7-9). The association of liprin-α1 with KIF1A led to speculation that liprins act as an adaptor for that particular motor protein. The interaction between liprin and GRIP appears to be involved in regulating AMPA receptor trafficking (2, 10). Liprin-α1 and -α4 bind GIT1 and dominant negative constructs of GIT1 led to a reduction in dendritic and surface-clustering of AMPA receptors in cultured neurons, implying that liprins, GIT1 and GRIP may work together to coordinate AMPA receptor trafficking. Through these myriad interactions, a general role for liprins may be protein trafficking to the active zone of synapses. Deletion of the liprin homolog syd-2 from C.elegans led to lengthening of the presynaptic active zone and impairment of synaptic transmission (5). However, as previously noted, the localization of liprin-α's to regions in neurons other than synaptic zones suggests that it has additional roles in the cell beyond organizing synaptic multiprotein complexes (11).

Since liprin-α1 was already known to be a phosphoprotein (1), we studied the effect of liprin-α1 phosphorylation on its interaction with LAR. Through yeast interaction trap analysis, biochemical precipitation of expressed and endogenous protein and co-localization of expressed protein, we determined that the interaction between liprin-α1 and LAR requires specific liprin-α1 phosphorylation. Moreover, studies on liprin-α1 indicated that it binds ATP-agarose, possesses in vitro autophosphorylation activity after purification and also retains this activity after denaturation and renaturation in an SDS gel. These findings suggest that the ability to autophosphorylate is intrinsic to liprin-α1.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmid constructions

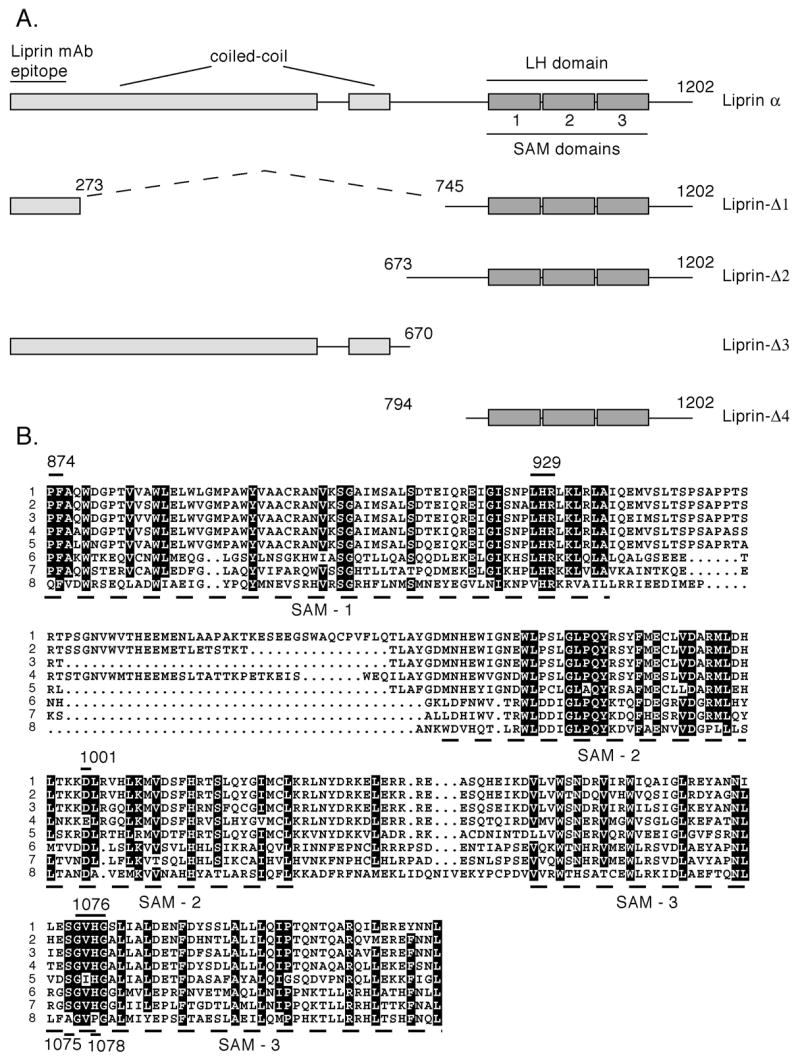

Liprin expression constructs were made using standard techniques and confirmed by restriction mapping and DNA sequencing. Liprin cDNA constructs were cloned into pMT or pMT.HA tag expression vectors which either use the liprin initiaiton methionine or a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope tag sequence immediately upstream of the cloning site. The liprin constructs used for this study are shown schematically in Fig. 1. Amino acid numbering of liprin is according to a full-length liprin-α1 of 1202 amino acids (Genbank accession number U22815), the liprin-Δ1 construct has residues 274 to 744 removed, liprin-Δ2 has residues 1-672 removed, liprin-Δ3 has residues 671-1202 removed and liprin-Δ4 has residues 1-793 removed. GST-tagged liprin-Δ2 was cloned into pFASTBAC (Invitrogen) and baculovirus was generated and propagated following manufacturer's instructions. For precipitation studies, the two intracellular phosphatase domains of LAR corresponding to residues 1275-1881 were fused to GST (6). GST-Tara consists of amino acids 12- 385 of Tara fused to GST as described (12). For immunofluorescence, pMT.LAR was used, encoding 1-1881 (13).

Figure 1.

Liprin-α1 and Liprin-α1 mutants. A) The structure of the 1202 amino acid liprin-α1 structure is shown schematically with the coiled-coil, the 3 SAM domains making up the liprin-homology region (LH region) and the liprin mAb epitope which was mapped to the region of amino acids 1-273. The residues encoding each construct are listed. Constructs containing an amino-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) tag will have the prefix HA. B) Liprin-α1 LH region homology. An alignment of the LH region of different liprin protein family members: 1. human liprin-α2 (gene accession number AF034799), 2. human liprin-α4 (AF034801), 3. human liprin-α1, (U22815), 4. human liprin-α3 (AF034800), 5. Drosophila liprin (AAN10596), 6. C.elegans liprin-α (Z50794), 7. human liprin-β1 (AF034802), 8. human liprin-β2 (AF034803) and 9. C.elegans liprin-β (Z78546). Identical residues are outlined in black and conserved in gray. Specific individual mutants in the LH region used in this study are shown with a line above the appropriate residue(s). These mutants are liprin.874PF875-AA, liprin.929LHR931-3A, liprin.D990-A, liprin.D1001-A, liprin.S1075-A, liprin.1076GVHG1079-4A and liprin.H1078-A.

Interaction trap assay

Plasmid DNAs and yeast strains used for the interaction trap assay were provided by Dr. R. Brent and colleagues (14) and used as described (1). The various liprin and LAR PTPase regions fused to LexA or the B42 transcription activation domain are given in Table I.

Table 1.

Interaction trap analysis between liprin and LAR. Shown is the ranking of colony growth on Leu-deficient media and blue color representing β-galactosidase activity of yeast colonies containing various pairs of liprin interaction-trap baits and interactors. The liprin-Δ4 constructs (amino acids 794-1202) are fused to the LexA DNA binding domain (the baits) and the LAR constructs are fused to the B42 transcription activation domains (the interactors). For each interaction pair, five clones were streaked for evaluation.

| pJG45/pLEX | LARD1D2 | LARD2 |

|---|---|---|

| Liprin.Δ4 | +++ | ++++ |

| Liprin.Δ4-H1078-AA | ++ | ++ |

| Liprin.Δ4-D1001-A | +++ | ++ |

| Liprin.Δ4-D990-A | + | + |

| Liprin.Δ4-GVHG1079-4A | - | - |

Cell transfections

COS-7 cell transient transfections were done by the DEAE-dextran/Me2SO method using approximately 2 μg of plasmid DNA/2 X 105 cells and cells were harvested approximately 20 hours after transfection. Proteins were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine labeling during the final 4 h prior to cell harvesting. COS-7 cells wer plated onto glass coverslips one day after transfection and fixed and stained the following day.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were stained essentially as described previously (15). Briefly cells were rinsed in PBS, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min and then permeabilized for 10 minutes in 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS containing 2% horse serum. Nonspecific ab-binding sites were blocked by a 30 min incubation in blocking buffer (10% normal goat serum in PBS). To detect liprin, either anti-liprin-α1 mAb 1.77 (1) or anti-HA mAb HA-11 (BabCO, Richmond, CA) were used and to detect LAR, anti-LAR mAb 11.1A was used (13). Primary antibodies were incubated for 1h, washed and detected after a 30 min incubation with Texas Red or fluorescein isothiocyanate-linked goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies. Slides were mounted in polyvinylalcohol medium and viewed on a Nikon E800 microscope equipped for epifluoresccnce.

Cell labeling and protein analysis

Cell proteins were metabolically labelled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine essentially as described previously (1). Following labelling, cells were washed in PBS, lysed in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA) containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride, 10 μg/mL leupeptin and 10 μg/mL aprotonin. Insoluble material was removed from the lysates by centrifugation in a microcentrifuge. Cell lysate were then precleared once with 25 μL of Protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) for 1 h. For immunoprecipitations, either 1 μg of anti-HA mAb Ha 11 or 1μg anti-liprin-α1 mAb anti-Lip.1.77 were used with 25 μL Protein A-Sepharose per mL of precleared lysate for 1-2h. Precipitates were washed with wash buffer containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 1 mM EDTA. Precipitates treated with calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) were suspended in 200 μL wash buffer adjusted with 5 mM MgCl2 and incubated 0.5 hr at 37 °C. The CIP was removed by centrifugation and washing the Protein A beads twice in wash buffer. Precipitations with GST-LAR were done with 5-10 μg of purified GST-LAR bound to glutathione-Sepharose and were washed as above. Precipitations with ATP-agarose (Sigma) used 50 μL of beads swollen and washed in lysis buffer. Precipitates were washed as above. Precipitated proteins were analysed using SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions followed by autoradiography. Autoradiographs were quantitated from scanned films using Un-Scan-It digitizing software from Silk Scientific, Inc. (Orem, UT). Proteins from cell lysates from non-labeled cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to Immobilon-P (Millipore, Bedford,MA) and immunoblots were probed with anti-HA mAb HA 11.

Human breast adenocarcinoma MDA-486 (ATCC HTB 132) cell lines were grown in DMEM containing 10% FCS, 50 μg/mL gentamicin sulfate and 2 mM L-glutamine. In vivo phosphorylation of COS-7 and MDA cells were performed as described (1). Briefly, two days following transfection (COS-7 cells), or one day following cell plating (MDA-486), cells were pre-incubated for 1 h in phosphate-free RPMI media (Life Technologies) containing 2% dialyzed FCS, 2 mM HEPES (pH 7.2) and then metabolically labelled with [32P]orthophosphate (9000 Ci/mmol); DuPont NEN) in the same media for 3 h at 37 °C (0.6 mCi [32P]orthophosphate/0.5-1 X 106 cells/mL). Following labelling, cells were washed in PBS and lysed as described above.

Expression in insect cells

Baculovirus expressing GST.liprin-Δ2 was created using the FASTBAC system (Invitrogen) and protein was expressed in Sf-9 insect cells. Cells were washed in PBS and lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (as above) and insoluble material removed by centifugation at 10 000g. 200 μL of glutathione-Sepharose was then added to the lysate and the sample was rotated 2h at 4 °C. Precipitates were washed extensively in a disposable Poly-prep column (BioRad) with 15 mL wash buffer (as above plus 500 mM NaCl) and 15 mL wash buffer. Resin was collected from the column and protein was eluted batchwise with 500 μL elution buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA) containing 3 mM glutathione. The glutathione was removed by dialysis for 0.5 h against 1L elution buffer on 0.025 μm MF filters (Millipore) and the purified protein stored on ice.

Phosphorylation assays

For the gel renaturation studies, approximately 0.5 μg of liprin constructs were subjected to SDS-PAGE and renaturated following incubation in 6 M guanidine HCl as described ((16), (17)). The gel was then incubated for 1 h at 25 °C with 3 mL of 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreiotol and 50 μM [γ-32P]ATP (0.5 Ci/mmol). Radioactivity was removed by extensive washing in 5% triocloroacetic acid, 1% sodium pyrophosphate. The gel was then stained with Coomassie Blue, dried and exposed to x-ray film. For in vitro phosphorylation assays, experiments used washed immunoprecipitates resuspended in 100 μL kinase buffer (20 mM Tris, pH7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM ATP [γ-32P]ATP and incubated 5 to 30 min at 37 °C. The kinase assay buffer was removed following centrifugation and the beads were boiled in SDS sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Peptide maps

Peptide maps were performed as described previously (18). Gel slices were hydrated, washed in MeOH to remove SDS and digested in 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate with 0.1 mg/mL Trypsin (Sigma) in minimal volume for 24 h at 37 °C. Liberated peptides were dried and separated in two dimensions by electrophoresis at pH 1.9 in acetic acid/formic acid/water (8:2:90 vol/vol) for 45 min at 800 V and by ascending chromatography in 1-butanol/pyridine/acetic acid/water (37.5/25/7.5/30 vol/vol). The plate was then dried and the labelled peptides visualized by autoradiography.

Results

Liprin constructs

For simplicity, liprin-α1 or liprin-α1 deletion constructs are termed liprin throughout. Liprin deletion constructs used in this study to characterize phosphorylation are depicted below the schematic drawing of full-length liprin (Figure 1A). An alignment of human liprin-α's and liprin-β's and Drosophila and C.elegans liprins reveals a high number of conserved residues in the liprin LH region (Figure 1B). Lines above the LH region alignment indicate conserved residues that were mutated to alanine for some liprin constructs used in these studies (Figure 1B). The liprin LH region mutations consist of mutations of individual residues (D990-A, D1001-A, S1075-A, H1078-A), or of short clusters of residues (874PF875-AA, 929LHR931-3A and 1076GVHG1079-4A). The numbering of these constructs correspond to that of human liprin-α1.

Reduced binding of liprin LH region mutants to LAR

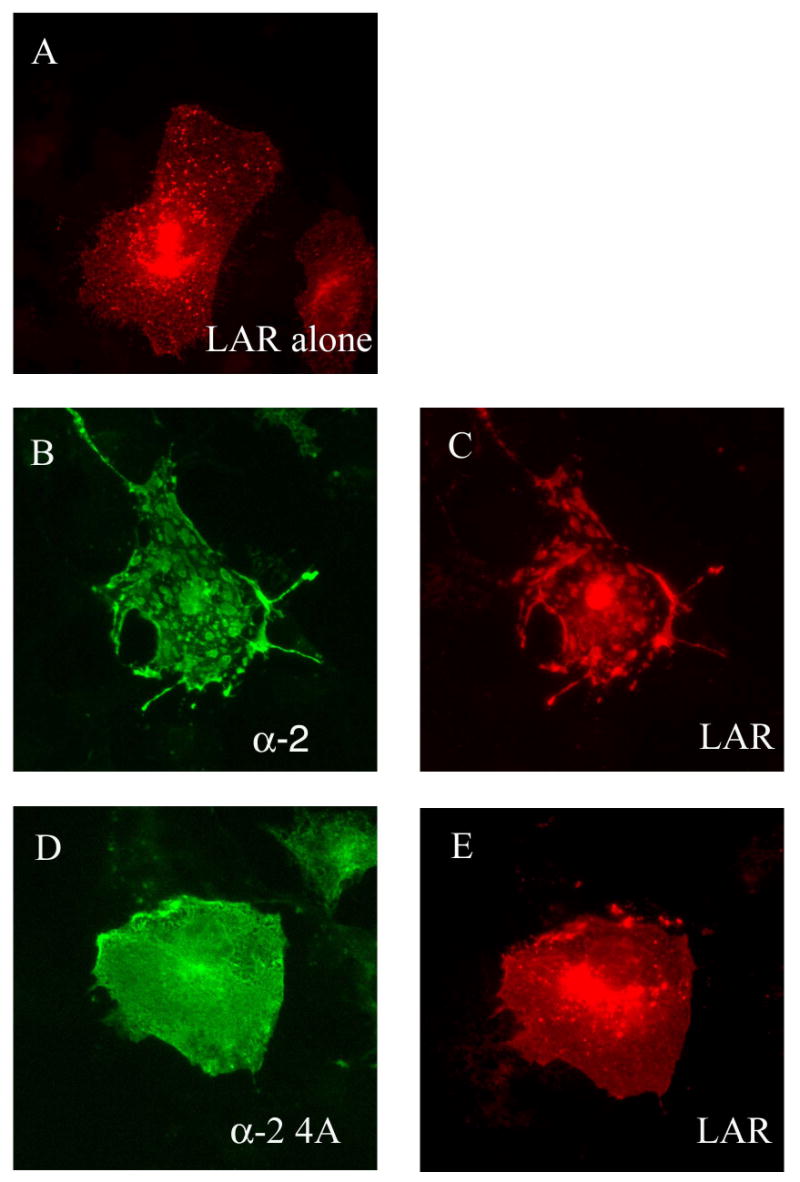

Using yeast interaction trap analysis, a series of liprin-Δ4 constructs were used as bait with the LAR intracellular region LARD1D2 as the interactor. In addition to wild-type liprin-Δ4, a series of constructs containing alanine substitutions in several of the most highly conserved regions of the liprin LH region were used. The 874PF875-AA and D990-A mutations each reduced binding of liprin to LAR and the 1076GVHG1079-4A mutation abolished binding (Table 1). The mutated amino acids should not fundamentally destabilize the SAM domains as they are predicted to reside in the loop regions. The GVHG-4A mutation was introduced into liprin-α2, as it is closely related to liprin-α1 and had been shown previously to crosslink LAR on the surface of cells (3). When wild-type liprin-α2 was co-expressed with LAR in COS-7 cells, it markedly clustered LAR at the cell surface as expected (Figure 2B and C). However, LAR that was co-expressed with liprin-α2.GVHG-4A was evenly distributed throughout the cell (Figure 2D and E) and indistinguishable from the staining observed in cells expressing LAR alone (Figure 2A). Unlike the punctate staining seen for wild-type liprin-α2, the localization of liprin-α2.GVHG-4A expressed alone (data not shown) or with LAR (Figure 2D) was evenly distributed throughout the cell.

Figure 2.

Expression of liprin-α2 but not liprin-α2-4A alters LAR cellular distribution. Immunofluorescence images of cells transiently transfected with LAR alone (A), liprin-α2 and LAR (B and C) or liprin-α2-4A and LAR (D and E). The cells were photographed for liprin (green, B and D) and LAR (red, A, C and E). All images are of identical magnification.

Liprin LH region mutants reduce liprin phosphorylation in vivo and in vitro

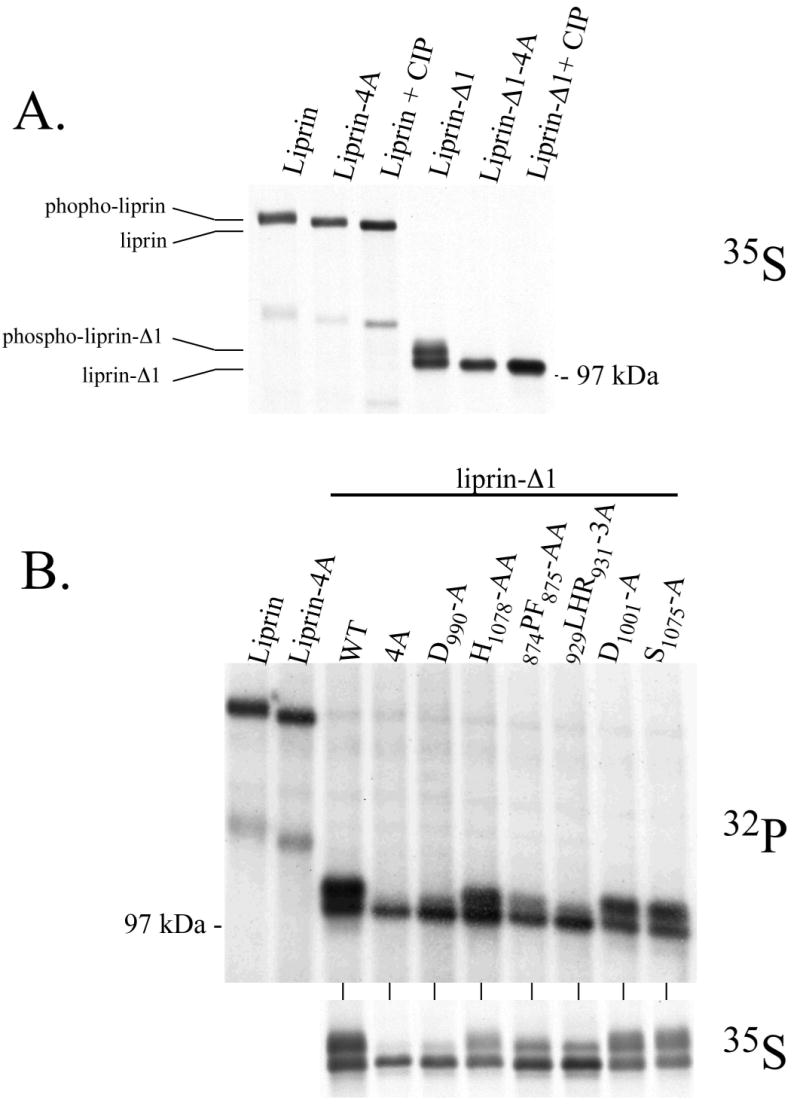

It was not expected that small mutations within the liprin LH region would have such drastic effects on the interaction between liprin and LAR. However, analysis of the electrophoretic mobility of wild-type liprin and the liprin.1076GVHG1079-4A construct on SDS-polyacryamide gels revealed phosphorylation differences between the proteins. COS-7 cells were transfected with full-length liprin, the liprin truncation construct liprin-Δ1 and 1076GVHG1079-4A mutant versions of each construct. The cells were labelled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine and the proteins immunoprecipitated with an anti-liprin monoclonal antibody. Liprin that had been incubated with calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) prior to electrophoresis had increased mobility on SDS-polyacrylamide gels relative to untreated liprin (Figure 3A). This suggests that liprin is constitutively phosphorylated when expressed in COS-7 cells. Additionally, the mobility of the liprin.1076GVHG1079-4A mutant was greater than that of wild-type liprin, suggesting that this mutation reduced the phosphorylation of liprin. The reduced gel mobility of wild-type liprin relative to the 1076GVHG1079-4A mutant and CIP-treated liprin was especially evident when the liprin-Δ1 construct was analyzed (Figure 3A). Liprin-Δ1 migrated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels as a doublet with a lower mobility form that is lost upon CIP treatment. Again. this result suggests that the lower mobility form of liprin results from phosphorylation. The lower mobility form of liprin-Δ1 was lost when the 1076GVHG1079-4A mutation was present, again suggesting that this mutation inhibits liprin phosphorylation.

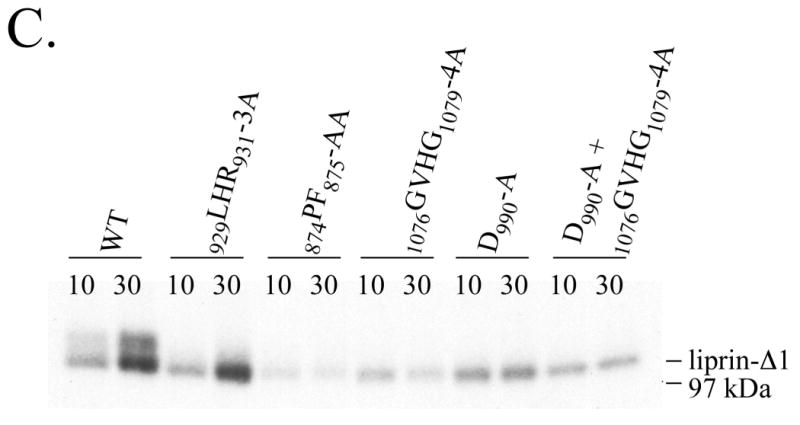

Figure 3.

Liprin is phosphorylated in vivo and in vitro. A) COS-7 cells were transfected with liprin constructs and metabolically labelled with 35S[Met] and 35S[Cys] and the liprin constructs immunoprecipitated as described in Experimental Procedures. Liprin, liprin-Δ1 and versions of each containing the 1076GVHG1079-4A mutation (shown in Fig. 1B) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Samples of liprin and liprin-Δ1 treated with CIP prior to electrophoresis are also present as indicated. B) COS-7 cells were transfected with liprin, liprin.1076GVHG1079-4A, liprin-Δ1 and liprin-Δ1 constructs containing LH region mutations. The cells were metabolically labelled with either 32P[orthophosphate] or 35S[Met] and 35S[Cys] and the liprin constructs immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography as described in Experimental Procedures. C) COS-7 cells were transfected with HA-tagged liprin-Δ1 and liprin-Δ1 constructs with mutations in the LH region. The liprin constructs were immunoprecipitated, washed extensively and assayed in an in vitro phosphorylation assay. After 10 and 30 minutes, samples were boiled with sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

To observe liprin phosphorylation in cells directly, COS-7 cells were transfected with full-length liprin or liprin-Δ1 constructs and labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine or [32P]orthophosphate prior to cell lysis and immunoprecipitation. Wild-type liprin and constructs containing liprin LH region mutations were used. The total phosphate incorporation into liprin and liprin.1076GVHG1079-4A construct was similar, although liprin.1076GVHG1079-4A had increased gel mobility as compared to the wild-type liprin (Figure 3B). Similarly, other liprin-Δ1 LH region mutants that had reduced binding to LAR also had less phosphorylated gel-shifted liprin when compared to wild-type protein. The lower mobility form of liprin-Δ1 is approximately 60% of the total liprin-Δ1 in the case of the wild-type, D1001-A and S1075-A constructs but only 35% for the 874PF875-AA construct and 25% for the D990-A and 1076GVHG1079-4A constructs. While the electrophoretic mobility of liprin was strongly affected by the LH region mutations, the total phosphorylation of the mutant liprin-Δ1 constructs were similar to that of wild-type protein when corrected for protein expression level. These results suggest that liprin LH region mutants inhibit liprin phosphorylation at key regulatory sites that affect gel mobility, rather than simply reducing total liprin phosphorylation.

In addition to altered gel mobility, a clear difference between wild-type liprin and liprin containing LH region mutations that inhibit binding to LAR was also observed in in vitro phosphorylation assays. Wild-type liprin-Δ1 and an LH region mutant with unaltered binding to LAR, liprin-Δ1.929LHR931-3A, were both phosphorylated in in vitro assays (Figure 3C). However, liprin mutations that reduced binding to LAR (874PF875-AA, D990-A or 1076GVHG1079-4A) inhibited phosphorylation in vitro. This suggests that in vitro liprin phosphorylation correlates to the formation of a phosphorylated form of liprin that binds LAR in vivo. Inclusion of EDTA in in vitro assays eliminated liprin phosphorylation whereas no obvious difference in liprin phosphorylation was observed using levels of MgCl2 from 2 to 10 mM (data not shown).

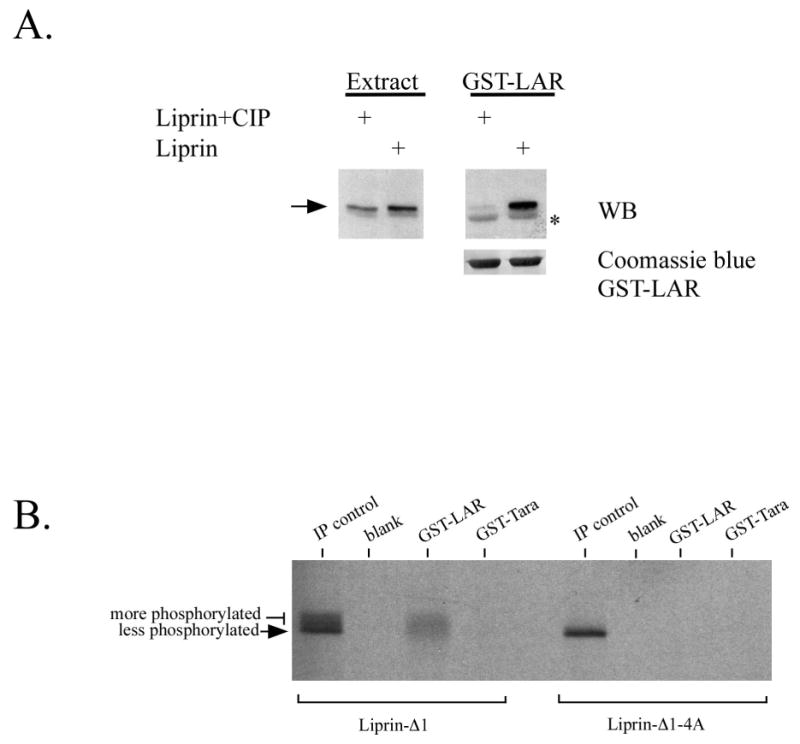

Liprin phosphorylation increases binding to LAR

We next tested the effect of CIP treatment on the ability of liprin to bind LAR. Treatment of cell lysates containing liprin with CIP prior to incubation with LAR largely abolished an interaction between liprin and LAR in co-precipitation studies (Figure 4A). The effect of constitutive liprin phosphorylation on LAR binding was further tested in precipitation assays. For these experiments, liprin-Δ1 was used as the phosphorylation state of the protein is more easily seen on gels. The two cytoplasmic phosphatase domains of LAR were expressed in bacteria as glutathione S-transferase fusion proteins (GST-LARD1D2) and used to precipitate liprin-Δ1 from lysates of COS-7 cells labelled with [35S]methionine an [35S]cysteine (Figure 4B). Liprin was not precipitated in control experiments using GST-Tara, a protein that binds to actin and to the LAR-associated protein Trio (12). SDS-PAGE of control immunoprecipitates revealed that although the customary lower mobility and higher mobility forms of liprin-Δ1 were present, GST-LARD1D2 precipitated the lower mobility, specifically phosphorylated form of liprin-Δ1 preferentially. The lower mobility form of liprin -Δ1 represents 1/3 of the total liprin-Δ1 precipitated by antibody, but 2/3 of the total liprin-Δ1 precipitated by LAR. The liprin-Δ1-4A immunoprecipitate contained little of the lower mobility phosphorylated protein and was not precipitated by LAR (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Liprin phosphorylation increases binding to LAR. A) Lysates of COS-7 cells transfected with HA-liprin were incubated either directly with GST-LARD1D2 on glutathione-Sepharose beads or first incubated with CIP for 30 minutes prior to addition of LAR. The precipitates were washed, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and western blotting analysis using anti-HA antibody. GST-LARD1D2 was detected non-specifically in the anti-HA western blot as a result of the large amount of protein present on the blot (indicated by *). (B) COS-7 cells transfected with HA.liprin-Δ1 or HA.liprin-Δ1.1076GVHG1079-4A were metabolically labelled with 35S[Met] and 35S[Cys] and cell lysates were used for precipitation by GST-LARD1D2 or control GST-Tara. The precipitates were washed, subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

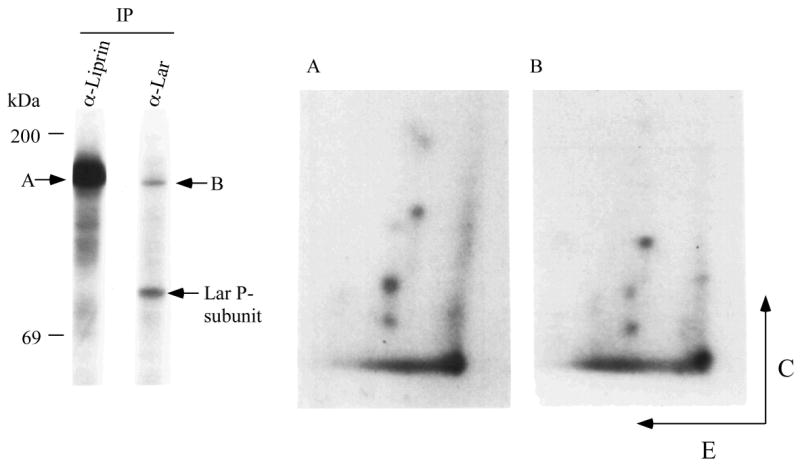

LAR binds phosphorylated liprin in cultured cells

The relevance of liprin phosphorylation to its interaction with LAR was seen through immunoprecipitation of endogenous LAR and liprin from MDA-486 cells that were in vivo labelled with [32P]orthophosphate. The liprin immunoprecipitate contained large amounts of a 32P-labelled 160 kDa protein (Figure 5) as reported previously (1). A 32P-labelled protein corresponding to the mobility of liprin was also present in LAR immunoprecipitates (Figure 5). The proteins (designated A and B, respectively) were excised from the gel, subjected to a limit trypsin digest and run on a two-dimensional peptide map for comparison. The two maps are very similar and indicate that the labelled protein in the LAR immunoprecipitate is liprin. This result is consistent with liprin phosphorylation positively regulating the interaction between liprin and LAR and suggests that it is an important regulatory process in vivo.

Figure 5.

LAR associates in vivo with phosphorylated liprin. MDA-486 cells were metabolically labelled with [32P]orthophosphate and subjected to precipitation using anti-liprin or anti-LAR mAb. The immunoprecipitates were washed, and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The precipitated liprin (A) and the protein with the mobility of liprin present in the LAR precipitate (B) were excised from the gel, subjected to a limit trypsin digest and run on peptide map (E denotes electrophoresis at pH 1.9 and C denotes chromatography).

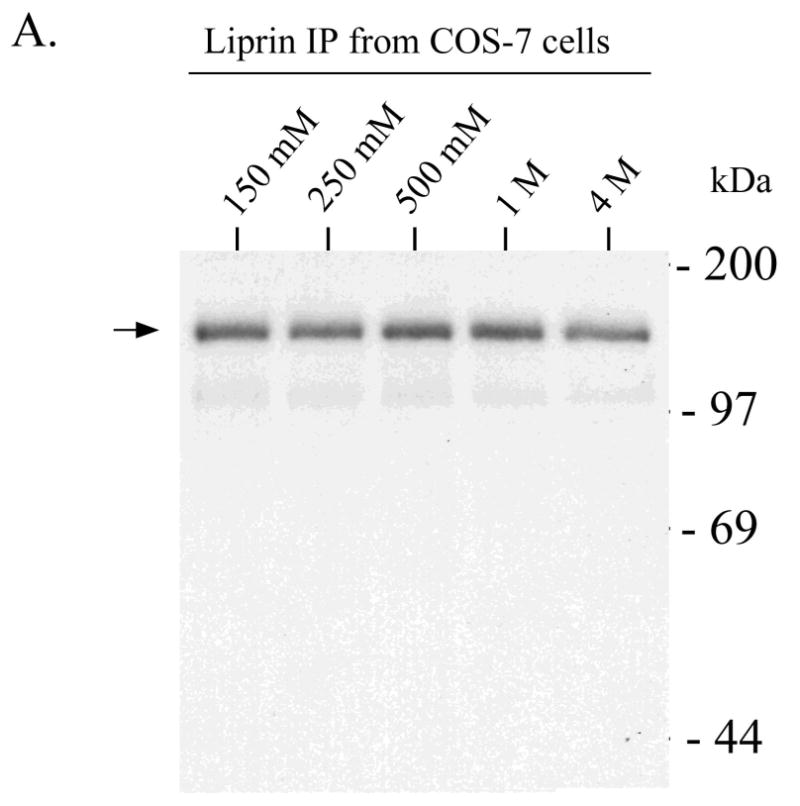

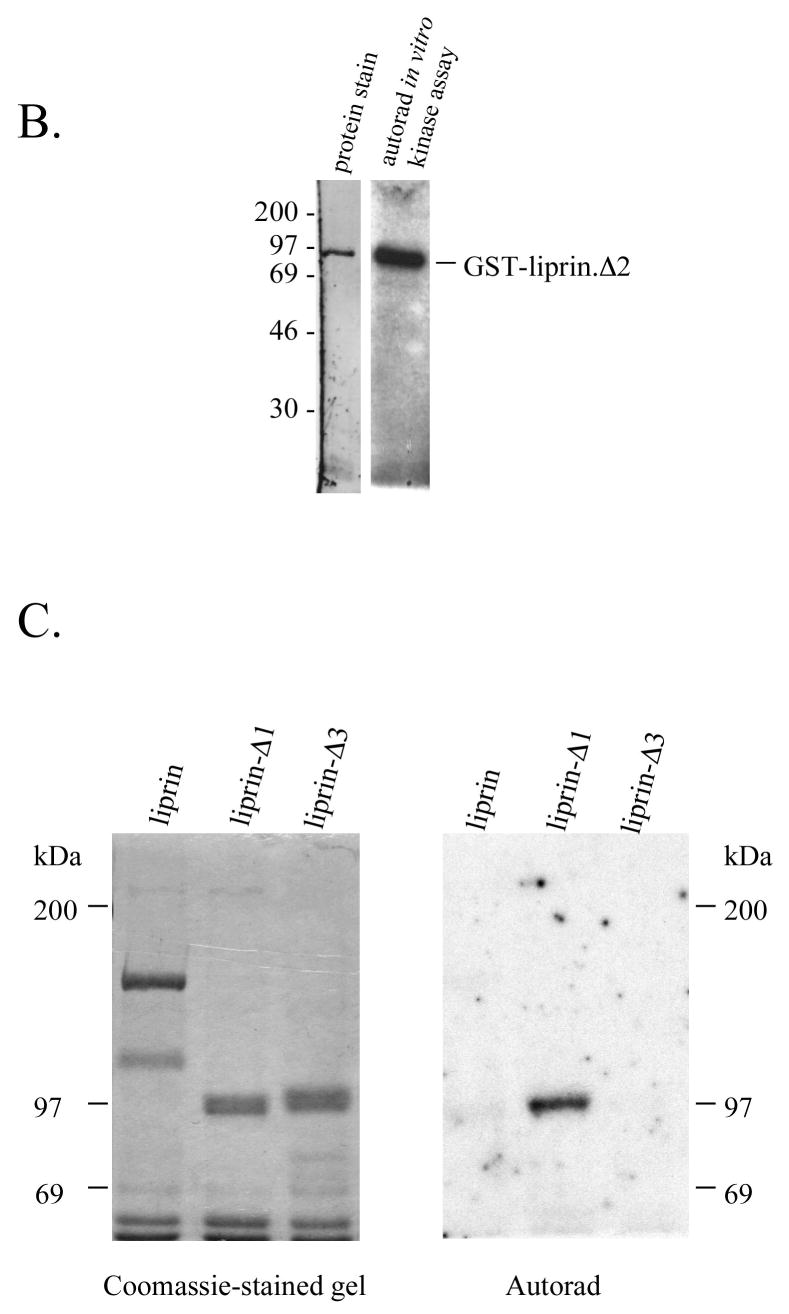

Autophosphorylation of purified liprin

To better characterize liprin phosphorylation, we assayed liprin after increasingly stringent purification procedures. Washing liprin immunoprecipitates with up to 4M NaCl had little effect on liprin phosphorylation in in vitro assays (Figure 6A). To obtain liprin that is not contaminated with associated proteins, bacterial expression of liprin was attempted but constructs containing the LH region appeared to be unstable. Liprin constructs that were tagged with GST or poly-His at the NH2- or COOH-terminal ends of the protein and also liprin that was targeted to the bacterial periplasmic space were not expressed in bacteria (data not shown). Bacteria transformed with liprin cDNA were boiled directly in SDS and subjected to Western blot analysis. No liprin protein was detected (data not shown) suggesting that the half-life of liprin in bacteria was extremely short. Consequently, baculovirus was used to express a GST-tagged version of liprin-Δ2 in Sf-9 insect cells. This particular liprin construct lacks any part of the liprin coiled-coil tail (Figure 1A) and was used in an attempt to reduce non-specific association of cellular proteins with liprin via its coiled-coil tail. Liprin-Δ2 was precipitated from the lysate with glutathione-Sepharose, washed extensively, eluted with free glutathione and dialyzed. The liprin preparation was highly pure and retained activity in in vitro phosphorylation assays (Figure 6B). Liprin purified further over a cationic exchange Uno S6 column (Bio-Rad) retained activity in in vitro phoshorylation assays (data not shown). In phosphorylation assays thus far, only liprin phosphorylation has been observed and common kinase substrate proteins were not phosphorylated in assays using purified liprin or stringently washed liprin immunoprecipitates (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Highly purified preparations of liprin undergo autophosphorylation. A) Liprin was expressed in COS-7 cells and liprin was immunoprecipitated and washed with up to 4M NaCl. The washed immunoprecipitates were subjected to an in vitro phosphorylation assay, SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Shown is the autoradiograph of samples washed with 150 mM, 250 mM, 500 mM, 1M or 4M NaCl. After higher salt washes, immunoprecipitates were washed once with normal wash buffer (150 mM NaCl) prior to assay. B) GST-tagged liprin-Δ2 in a baculovirus construct was expressed in Sf-9 insect cells. The GST.liprin-Δ2 was precipitated using glutathione-Sepharose, washed extensively and eluted with 3 mM free glutathione. The glutathione was removed by dialysis and the sample was subjected to an in vitro phosphorylation assay as described in Experimental Procedures. Shown is the gel stained for protein (SYPRO Orange. BioRad) and the corresponding autoradiograph. C) COS-7 cells transfected with liprin, liprin-Δ1 or liprin-Δ3 were lysed and the liprin constructs immunoprecipitated with anti-liprin mAb. The liprin immunoprecipitates were washed extensively, subjected to SDS-PAGE, renatured in the gel and incubated with [γ-32P]-ATP as described under Experimental Procedures and then stained with Coomassie Blue.

We next performed in vitro phosphorylation reactions with liprin, liprin-Δ1 and liprin-Δ3 after SDS-PAGE and gel denaturation/renaturation. While full-length liprin and liprin-Δ3 (lacking the LH region) were not active following renaturation, liprin-Δ1 was (Figure 6C). It is possible that the full-length liprin, with the entire coiled-coil region, renatured less efficiently than the smaller construct. Full-length myosin heavy chain kinase A, a member of the α-kinase protein kinase family that also possesses a long α-helical coiled-coil domain, also renatured less efficiently than shorter forms of the protein (17). It is also possible that an inhibitory domain not present in liprin-Δ1 reduces phosphorylation in renatured full-length liprin.

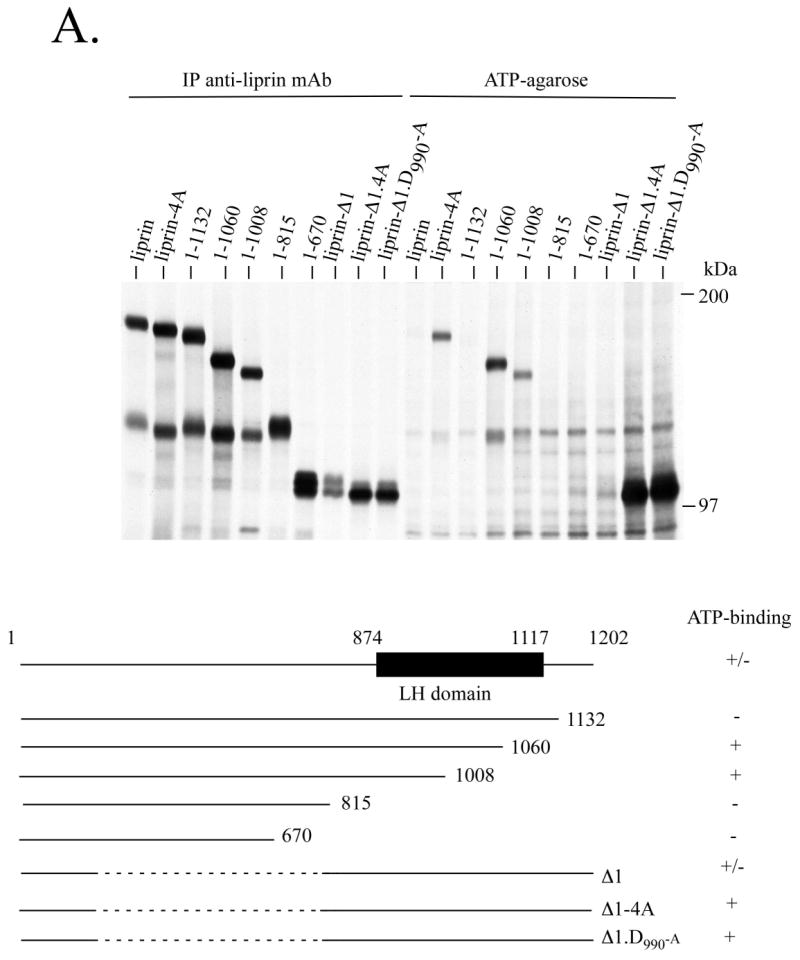

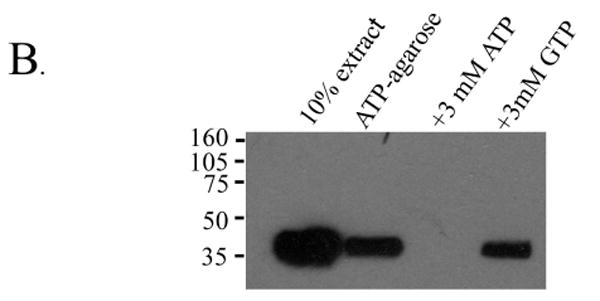

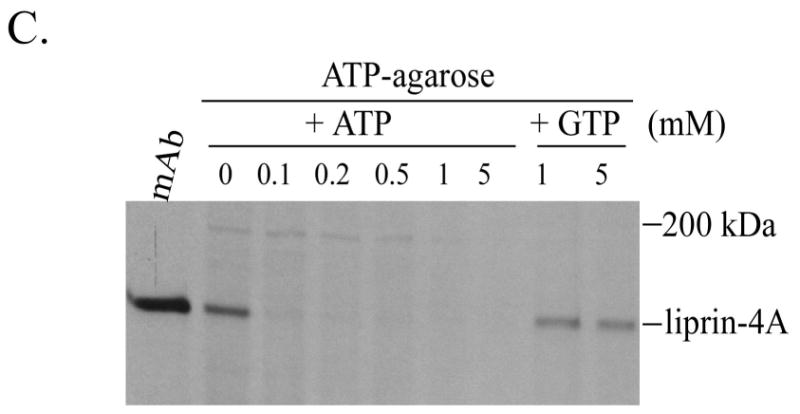

Liprin binds ATP

The ability of liprin to bind ATP was studied next. COS-7 cells were transfected with a series of liprin constructs that systematically truncated the LH region and with liprin and liprin-Δ1 constructs containing LH region mutations that inhibited liprin phosphorylation. Lysates from these cells were used in ATP-agarose binding studies. Liprin-(1-815) did not bind ATP-agarose indicating that the coiled-coil domain is not involved in ATP binding (Figure 7A). Other liprin constructs did bind ATP-agarose and the ATP-binding domain of liprin was mapped to the LH region between amino acids 854-1008. Interestingly, liprin or liprin-Δ1 constructs that contain the mutations 1076GVHG1079-4A or D990-A, both of which inhibited in vitro and in vivo liprin phosphorylation, bound ATP-agarose much more strongly than wild-type (Figure 7A). Deletion constructs that removed portions of the LH region also bound ATP-agarose more strongly than wild-type liprin. These results suggest that altering the LH region, either through small mutations or larger deletions, stabilized the interaction between liprin and ATP. Full-length liprin bound less well to ATP-agarose than liprin-Δ1, possibly suggesting the presence of an inhibitory domain in liprin.

Figure 7.

The liprin LH region binds ATP. A) COS-7 cells were transfected with various liprin and liprin-Δ1 constructs. The cells were metabolically labelled with 35S[Met] and 35S[Cys] and lysates were used for precipitation with either anti-liprin mAb or ATP-agarose. After extensive washes, samples were boiled in SDS sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Below is a table summarizing the results. Liprin binding to ATP-agarose is inhibited by free ATP but not free GTP. B) Lysates from COS-7 cells transfected with HA.liprin-Δ4 were used for precipitation with ATP-agarose alone or in the presence of 2 mM ATP or 2 mM GTP. The samples were washed, boiled in sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibody. C) Lysates from COS-7 cells transfected with liprin.1076GVHG1079-4A and metabolically labelled with 35S-(Met and Cys) were used for precipitation with either anti-liprin mAb or with ATP-agarose in the presence of 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1 or 5 mM free ATP or in the presence of 1 or 5 mM free GTP. The samples were washed, boiled in sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

To test the specificity of liprin for ATP, COS-7 cells were transfected with liprin. 1076GVHG1079-4A and the lysate was incubated with ATP-agarose in the presence of free ATP or GTP (Figure 7B). Under these conditions, 3 mM free ATP abolished binding to ATP-agarose while 3 mM free GTP had little effect. Titrating the amount of free ATP showed that as little as 0.1mM completely abolished binding to ATP-agarose whereas up to 5mM free GTP had little effect on binding to ATP-agarose (Figure 7C).

In summary, several liprin LH region mutations inhibit the formation of a phosphorylation-dependent gel-shifted form of liprin that binds LAR. These LH regions mutations also inhibit liprin phosphorylation in in vitro phosphorylation assays. Highly purified liprin retains activity in in vitro phosphorylation assays and following gel denaturation/renaturation. Additionally, liprin specifically binds ATP via its LH region and liprin LH region mutations that inhibit phosphorylation and LAR-binding also stabilized the interaction between liprin and ATP-agarose. Taken together, these characteristics suggest that liprin undergoes autophosphorylation and that this process regulates its binding to LAR.

Discussion

We report here that the interaction between the liprin-α's and the LAR protein tyrosine phosphatase is regulated by liprin-α autophosphorylation. In vitro co-precipitation experiments revealed that dephosphorylated liprin did not bind to LAR. Liprin LH region mutations that reduce liprin autophosphorylation also reduce the binding to liprin to LAR in yeast interaction trap studies and in biochemical pulldown experiments. A liprin-α2 LH region mutant also failed to cluster LAR when the proteins were co-expressed in heterologous cells, suggesting that mutations that affect liprin autophosphorylation alter the function of liprin in cells. Additionally, endogenous LAR precipitated phosphorylated liprin-α1 from cells that were labelled in vivo with [32P]orthophosphate.

It is not clear how liprin autophosphorylation promotes binding between liprin and LAR. It is possible that one or more of the liprin SAM domains are phosphorylated and that their binding properties are altered. Although the SAM domain of the ELK receptor protein tyrosine kinase is known to require tyrosine phosphorylation to bind grb2 and grb10 (19), this phosphorylation creates a binding site for the grb SH2 domains and does not appear to fundamentally alter the SAM domain binding characteristics. It is also possible that phosphorylation of a site within liprin results in a conformational change that allows greater access of LAR to the LH domain. Liprin is phosphorylated in vivo on serine residues and there are several cluster of serines between residues 680 and 790 of liprin between the coiled-coil tail and LH region. Phosphorylation in this region could alter the position of the LH region relative to the coiled-coil tail to promote binding to LAR. The binding of liprin to LAR correlates to the presence of phosphorylated liprin with reduced mobility on SDS-polyacrylamide gels, perhaps reflecting an alteration in the conformation of liprin monomers. In addition to LAR, liprin-α binds KIF, RIM and GIT 1 (1, 7, 8). It is unclear if liprin autophosphorylation would regulate binding to these proteins as they bind the coiled-coil region of liprin.

Based on amino acid sequence homology, there is little to suggest that liprin would bind ATP. The liprin ATP-binding site was mapped to the LH region which is composed of 3 tandem SAM domains. SAM domains were initially thought to be exclusively protein interaction domains but have recently been shown to be capable of remarkable versatility. They have been shown to dimerize or form oligomers (20), to bind SAM domains from other proteins (21, 22), to bind other proteins lacking SAM domains (1, 3) and to bind RNA (23-25) and lipid membranes (26). Moreover, there are numerous examples of proteins that were shown to possess physical properties that were unexpected based on their amino acid sequence. The synapsin protein family has little homology to ATP-clasp enzymes yet, when crystallized, displayed a remarkable similarity in conformation (27, 28). Similarly, the ATPase/kinase superfamily consists of proteins with similar catalytic domains structurally but with little amino acid sequence homology (reviewed in (29)) and includes diverse members such as hsp90, histidine kinases and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase. Finally, the α-kinase protein family was found to have strong structural similarities to conventional protein kinases when crystallized despite a lack of amino acid sequence homology to conventional kinases (30, 31).

Several characteristics of liprin phosphorylation suggest the possibility that liprin possesses the intrinsic ability to autophosphorylate: 1) Immunoprecipitated liprin is phosphorylated in vitro after stringent washing of the immunoprecipitates by up to 4M salt. 2) Highly purified preparations of liprin expressed in insect cells were phosphorylated in in vitro assays. 3) The liprin deletion construct liprin-Δ1 retains the ability to autophosphorylate after denaturation and renaturation in an SDS-polyacrylamide gel. 4) Binding studies with ATP-agarose indicate that liprin specifically binds ATP, but not GTP, and that the liprin mutations D990-A or 1076GVHG1079-4A stabilize the interaction between liprin and ATP-agarose. 5) Several short mutations within the liprin LH region (D990-A, 874PF875-AA or 1076GVHG1079-4A) resulted in the reduction of a phosphorylation-dependent form of liprin with reduced mobility on SDS-polyacrylamide gels when it was expressed in cells. These same mutations also reduce in vitro phosphorylation of liprin in assays using stringently washed immunoprecipitates. To eliminate the possibility of liprin preparations being contaminated by associated protein kinases, it will be necessary to assay bacterially-expressed liprin and efforts to produce liprin constructs that are stable in bacteria are ongoing.

The three LH region mutations that affected liprin phosphorylation: 874PF875-AA, D990-A and 1076GVHG1079-4A, are in each of the three separate SAM domains. The D990-A and 1076GVHG1079-4A mutations fall within the loop adjacent to helix 3 of SAM domain 2 and 3 respectively. This region was shown to be part of the binding surface and to be involved in oligomer formation for SAM domain from Tel (20). Since these liprin LH region mutations inhibit liprin autophosphorylation and increase binding to ATP-agarose, they may be involved in catalysis. Mutation of a catalytic residue could produce a form of liprin that binds but does not use ATP, analogous to catalytic mutations in tyrosine phosphatases that “trap” phosphorylated substrates (32). Alternatively, if liprin autophosphorylation reduces its affinity for ATP, the inhibition of autophosphorylation by these LH region mutants may increase binding to ATP-agarose. The inability of these liprin mutants to autophosphorylate efficiently may result from the alteration of interactions between liprin SAM domains, either within a single polypeptide chain or between SAM domains from separate liprin monomers. Although the liprin-α LH regions have little affinity for each other as assessed by interaction trap analysis, an interaction between LH regions could be stabilized by association of the liprin-α coiled-coil domains, which have been shown to dimerize (3). Full-length liprin bound less well to ATP-agarose than liprin-Δ1 and was less active in denaturation/renaturation experiments. These results may suggest the presence of an inhibitory domain within full-length liprin. The use of more comprehensive liprin deletion constructs for ATP-binding and autophosphorylation assays may allow a liprin inhibitory domain to be identified. We have also not observed phosphorylation of common kinase substrates by liprin (data not shown) suggesting that liprin either possesses a relatively high degree of specificity or is restricted to autophosphorylation.

While the experiments in this study are performed almost exclusively using liprin-α1, there is a high degree of homology between liprin-α1 and other liprin-α's and liprin-β's in the LH region. The high level of identity of these key LH region residues among all liprins suggests that other liprins may also be regulated by autophosphorylation. The inability of lipin-α2 containing the GVHG-4A mutation to crosslink LAR in cells indicates that findings for liprin-α1 may be generally applicable to other liprin-α's at least. Although liprin-β's do not bind LAR, phosphorylation may regulate the association between liprin-β and proteins associating with the its LH region, such as the small calcium binding protein S100A4 (33).

In conclusion, rather than being exclusively an adaptor protein, liprin appears to possess the ability to bind ATP and autophosphorylate. Liprin autophosphorylation regulates binding between liprin and LAR and liprin may represent a new class of adaptor proteins that self-regulate associations through an intrinsic enzymatic activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the expert assistance provided by Elizabeth Buchbinder, May Tang and Dan McLaughlin.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grants CA55547 and CA75091 from the National Institutes of Health.

The abbreviations used are: SAM, sterile alpha motif; LH, liprin homology; HA, hemeagglutinin; mAb, monoclonal antibody; GST, glutathione S-transferase; CIP, calf intestinal phosphatase.

References

- 1.Serra-Pages C, Kedersha NL, Fazikas L, Medley Q, Debant A, Streuli M. The LAR transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase and a coiled-coil LAR-interacting protein co-localize at focal adhesions. Embo J. 1995;14:2827–38. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wyszynski M, Kim E, Dunah AW, Passafaro M, Valtschanoff JG, Serra-Pages C, Streuli M, Weinberg RJ, Sheng M. Interaction between GRIP and liprin-alpha/SYD2 is required for AMPA receptor targeting. Neuron. 2002;34:39–52. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00640-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serra-Pages C, Medley QG, Tang M, Hart A, Streuli M. Liprins, a family of LAR transmembrane protein-tyrosine phosphatase-interacting proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15611–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufmann N, DeProto J, Ranjan R, Wan H, Van Vactor D. Drosophila liprin-alpha and the receptor phosphatase Dlar control synapse morphogenesis. Neuron. 2002;34:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhen M, Jin Y. The liprin protein SYD-2 regulates the differentiation of presynaptic termini in C. elegans. Nature. 1999;401:371–5. doi: 10.1038/43886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pulido R, Serra-Pages C, Tang M, Streuli M. The LAR/PTP delta/PTP sigma subfamily of transmembrane protein-tyrosine-phosphatases: multiple human LAR, PTP delta, and PTP sigma isoforms are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and associate with the LAR-interacting protein LIP.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:11686–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ko J, Na M, Kim S, Lee JR, Kim E. Interaction of the ERC family of RIM-binding proteins with the liprin-alpha family of multidomain proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42377–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoch S, Castillo PE, Jo T, Mukherjee K, Geppert M, Wang Y, Schmitz F, Malenka RC, Sudhof TC. RIM1alpha forms a protein scaffold for regulating neurotransmitter release at the active zone. Nature. 2002;415:321–6. doi: 10.1038/415321a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko J, Kim S, Valtschanoff JG, Shin H, Lee JR, Sheng M, Premont RT, Weinberg RJ, Kim E. Interaction between liprin-alpha and GIT1 is required for AMPA receptor targeting. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1667–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01667.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baran R, Jin Y. Getting a GRIP on liprins. Neuron. 2002;34:1–2. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shin H, Wyszynski M, Huh KH, Valtschanoff JG, Lee JR, Ko J, Streuli M, Weinberg RJ, Sheng M, Kim E. Association of the kinesin motor KIF1A with the multimodular protein liprin-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11393–401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seipel K, O'Brien SP, Iannotti E, Medley QG, Streuli M. Tara, a novel F-actin binding protein, associates with the Trio guanine nucleotide exchange factor and regulates actin cytoskeletal organization. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:389–99. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.2.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streuli M, Krueger NX, Ariniello PD, Tang M, Munro JM, Blattler WA, Adler DA, Disteche CM, Saito H. Expression of the receptor-linked protein tyrosine phosphatase LAR: proteolytic cleavage and shedding of the CAM-like extracellular region. Embo J. 1992;11:897–907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R. Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell. 1993;75:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medley QG, Serra-Pages C, Iannotti E, Seipel K, Tang M, O'Brien SP, Streuli M. The trio guanine nucleotide exchange factor is a RhoA target. Binding of RhoA to the trio immunoglobulin-like domain. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36116–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kameshita I, Fujisawa H. A sensitive method for detection of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. Anal Biochem. 1989;183:139–43. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Futey LM, Medley QG, Cote GP, Egelhoff TT. Structural analysis of myosin heavy chain kinase A from Dictyostelium. Evidence for a highly divergent protein kinase domain, an amino-terminal coiled-coil domain, and a domain homologous to the beta-subunit of heterotrimeric G proteins. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:523–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medley QG, Kedersha N, O'Brien S, Tian Q, Schlossman SF, Streuli M, Anderson P. Characterization of GMP-17, a granule membrane protein that moves to the plasma membrane of natural killer cells following target cell recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:685–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stein E, Cerretti DP, Daniel TO. Ligand activation of ELK receptor tyrosine kinase promotes its association with Grb10 and Grb2 in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23588–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim CA, Phillips ML, Kim W, Gingery M, Tran HH, Robinson MA, Faham S, Bowie JU. Polymerization of the SAM domain of TEL in leukemogenesis and transcriptional repression. Embo J. 2001;20:4173–82. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posas F, Witten EA, Saito H. Requirement of STE50 for osmostress-induced activation of the STE11 mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase in the high-osmolarity glycerol response pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5788–96. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimshaw SJ, Mott HR, Stott KM, Nielsen PR, Evetts KA, Hopkins LJ, Nietlispach D, Owen D. Structure of the sterile alpha motif (SAM) domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway-modulating protein STE50 and analysis of its interaction with the STE11 SAM. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2192–201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green JB, Gardner CD, Wharton RP, Aggarwal AK. RNA recognition via the SAM domain of Smaug. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1537–48. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green JB, Edwards TA, Trincao J, Escalante CR, Wharton RP, Aggarwal AK. Crystallization and characterization of Smaug: a novel RNA-binding motif. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:1085–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02327-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aviv T, Lin Z, Lau S, Rendl LM, Sicheri F, Smibert CA. The RNA-binding SAM domain of Smaug defines a new family of post-transcriptional regulators. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:614–21. doi: 10.1038/nsb956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barrera FN, Poveda JA, Gonzalez-Ros JM, Neira JL. Binding of the C-terminal sterile alpha motif (SAM) domain of human p73 to lipid membranes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46878–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esser L, Wang CR, Hosaka M, Smagula CS, Sudhof TC, Deisenhofer J. Synapsin I is structurally similar to ATP-utilizing enzymes. Embo J. 1998;17:977–84. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosaka M, Sudhof TC. Synapsins I and II are ATP-binding proteins with differential Ca2+ regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1425–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dutta R, Inouye M. GHKL, an emergent ATPase/kinase superfamily. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:24–8. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De la Roche MA, Smith JL, Betapudi V, Egelhoff TT, Cote GP. Signaling pathways regulating Dictyostelium myosin II. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2002;23:703–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1024467426244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi H, Matsushita M, Nairn AC, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the atypical protein kinase domain of a TRP channel with phosphotransferase activity. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1047–57. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flint AJ, Tiganis T, Barford D, Tonks NK. Development of “substrate-trapping” mutants to identify physiological substrates of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1680–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kriajevska M, Fischer-Larsen M, Moertz E, Vorm O, Tulchinsky E, Grigorian M, Ambartsumian N, Lukanidin E. Liprin beta 1, a member of the family of LAR transmembrane tyrosine phosphatase-interacting proteins, is a new target for the metastasis-associated protein S100A4 (Mts1) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5229–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]