Abstract

In vitro treatment of Echinococcus multilocularis and Echinococcus granulosus larval stages with the antimalarials dihydroartemisinin and artesunate (10 to 40 μM) exhibited promising results, while 6 weeks of in vivo treatment of mice infected with E. multilocularis metacestodes (200 mg/kg of body weight/day) had no effect. However, combination treatments of both drugs with albendazole led to a substantial but statistically not significant reduction in parasite weight compared to results with albendazole alone.

Cystic echinococcosis, caused by Echinococcus granulosus, is distributed worldwide. Alveolar echinococcosis, caused by Echinococcus multilocularis, is generally confined to the northern hemisphere (2). Growth and/or proliferation of Echinococcus metacestodes, mainly in the liver but also in the lungs and other organs, leads to the development of space-occupying lesions and organ malfunction and will eventually cause death (10, 23). The preferred treatment option is radical resection of the parasitic mass. Surgery is accompanied by chemotherapy, and in inoperable cases, chemotherapy is the only option. Albendazole and mebendazole are currently used (8, 10). For alveolar echinococcosis, these compounds were shown to act parasitostatically rather than parasitocidally, with high recurrence rates after interruption of therapy. Improved drug treatments are needed (8, 24).

Most countries to which malaria is endemic have now adopted artemisinin-based combination therapy as a first-line treatment for Plasmodium falciparum infection (34), and activities of artemisinins against other protozoans have been reported (1, 12). Trematodes, including schistosomes (31) and others, have proven susceptible to artemisinins and semisynthetic derivatives (13-16, 26), and antitumor activities of artemisinins have been reported (11, 18, 35). E. multilocularis metacestodes also exhibit tumor-like properties, including potentially unlimited growth and proliferation (17). These findings have prompted us to investigate the potential of artemisinins for antiechinococcal treatment.

We first assessed the in vitro activities of artemisinin, artesunate, artemether, and dihydroartemisinin (DHA) against E. granulosus and E. multilocularis larval stages. These were evaluated in comparison to albendazole and nitazoxanide as reference drugs (8). All compounds were dissolved as stock solutions of 10 mM in dimethylsulfoxide.

E. granulosus protoscoleces were isolated, maintained, and tested in vitro as described earlier (21, 32). Compounds were added at 4, 10, and 40 μM. Viability of protoscoleces was assessed microscopically by using a trypan blue exclusion test (Fig. 1). At 40 μM, artesunate and DHA exhibited activities similar to that of nitazoxanide (32), but the action of DHA was delayed by 2 days (with a 90% reduction in viability occurring on day 6.) Artemisinin and artemether were ineffective (data not shown). At 10 μM, artesunate and DHA showed strongly decreased efficacies compared to that of nitazoxanide (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Protoscolicidal activity of artemisinin derivatives. E. granulosus protoscoleces were cultured in vitro in the presence of artesunate, DHA, and nitazoxanide (NTZ) as a positive control (10 and 40 μM). Note the dose-dependent killing of protoscoleces by both artesunate and DHA. This experiment was repeated three times with virtually identical outcomes. One representative result is shown. DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide.

E. multilocularis metacestode drug assays were carried out as previously described (7, 9, 21, 27, 28, 30). Artemisinins and albendazole were added to the cultures at a concentration of 40 μM. During the 12-day treatment, 200 μl of culture supernatant was collected daily and stored at −20°C to measure E. multilocularis alkaline phosphatase (EmAP) activity (30). Artesunate treatment led to a rapid increase of EmAP activity in medium supernatants within 4 days (Fig. 2). DHA exhibited a delayed effect, with an increased EmAP activity coming up at day 8. Artemisinin and artemether treatments did not result in a high-level EmAP release (Fig. 2), as earlier reported by Reuter et al. (25). No elevated EmAP levels were observed at 10 μM drug concentrations (data not shown). EmAP activity has been identified earlier as a marker indicating the loss of viability of in vitro drug-treated vesicles (28, 30). Our findings correlated well with scanning and transmission electron microscopy analyses (6), confirming that in vitro exposure of E. multilocularis metacestodes to artesunate and DHA resulted in profound tissue alterations and loss of the characteristic multicellular structure of the germinal layer (data not shown). Similar observations were made when E. granulosus metacestodes were exposed to these compounds (M. Spicher and A. Hemphill, unpublished).

FIG. 2.

EmAP activity in culture supernatant of drug-treated E. multilocularis metacestodes. Artesunate, DHA, artemisinin, and artemether were applied to in vitro-cultured vesicles at 40 μM, and EmAP activity was measured in culture supernatants at different time points as indicated. Albendazole (ABZ) and corresponding amounts of the solvent dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) were added as positive and negative controls, respectively.

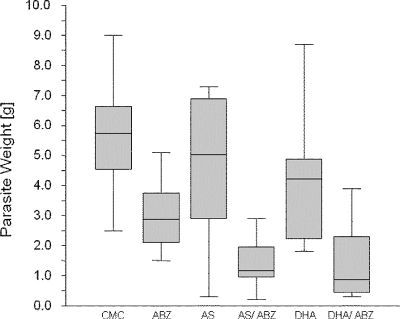

The effects of artesunate and DHA were further evaluated with the experimental BALB/c mouse model (27, 29). Mice were separated into 6 treatment groups of 10 animals each. Drug suspensions were prepared in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) and were applied as follows: (i) artesunate at 200 mg/kg of body weight (bw), (ii) a combination of artesunate (200 mg/kg bw) and albendazole (50 mg/kg bw), (iii) DHA (200 mg/kg bw, (iv) a combination of DHA (200 mg/kg bw) and albendazole (50 mg/kg bw), (v) albendazole at 200 mg/kg bw, and (vi) 0.5% CMC alone (control group). Treatment began at 8 weeks postinfection, and the drug and control suspensions were applied by intragastric inoculation (100 μl/mouse/day) for 6 weeks. Finally, mice were sacrificed by CO2 euthanasia, and parasite tissue removed from the peritoneal cavity, and the parasite weight was determined (Fig. 3). Parasite weights within the CMC control (5.71 ± 1.79 g), artesunate (4.60 ± 2.28 g), and DHA (4.11 ± 2.03 g) groups were consistently high, with minor differences. As expected, continuous treatment of mice with albendazole (2.96 ± 1.10 g) resulted in a significant reduction in parasite weight. In addition, the combination of artesunate and albendazole (1.39 ± 0.81 g) and the combination of DHA and albendazole (1.38 ± 1.25 g) resulted in an even more pronounced reduction of the parasite weights compared to the control (Fig. 3). The improvements obtained with albendazole, artesunate-albendazole, and DHA-albendazole were highly significant (in one-way analysis of variance, F = 44.66; P = 0.0000). The artesunate-albendazole and DHA-albendazole treatments resulted in lower mean parasite weights than were obtained with the albendazole treatment alone, but the differences narrowly missed statistical significance (Kruskal-Wallis multiple-comparison z-value test; differences were considered significant if the z value was >1.96; the z value for artesunate-albendazole was 1.89; the z value for DHA-albendazole was 1.92).

FIG. 3.

Experimental chemotherapy with E. multilocularis-infected mice. In vivo treatment of E. multilocularis-infected mice was carried out with albendazole (ABZ), artesunate (AS), dihydroartemisinin (DHA), and combinations of ABZ-AS and ABZ-DHA. CMC is the solvent control (0.5% CMC in phosphate-buffered saline). The box plots indicate the distribution of parasite weights in the different treatment groups. Significant reductions in parasite weights in relation to those in the CMC control group were achieved by treatment with ABZ, ABZ-AS, and ABZ-DHA. Although the combination treatments were the most efficient, the reduction in both groups in relation to ABZ alone was not significant (Kruskal-Wallis multiple-comparison z-value test; difference was significant with a z value of >1.96; z value for artesunate-ABZ was 1.89; z value for DHA-ABZ was 1.92).

No adverse effects were observed in the drug-treated groups, with the exception of one mouse that was found dead in the DHA-albendazole group at day 30 and one mouse that was found dead in the artesunate-albendazole group at day 32. The deaths of these two mice could potentially be attributed to the described toxicity and neurotoxicity of artemisinin derivatives in laboratory animals (3, 4, 20, 22). However, none of the mice exhibited any aberrant behavior during the treatments, and histopathological examination of liver, kidney, and brain tissue did not show any signs of toxicity, indicating that the deaths of these two mice could possibly be attributed to other causes.

The promising in vitro results that were achieved with artesunate and DHA (Fig. 1 and 2) could not be completely translated to the in vivo mouse model (Fig. 3). There are several potential explanations for this. First, artemisinins are primarily converted to DHA via ester hydrolysis and further to inactive metabolites by hepatic cytochrome P-450 and other enzyme systems (19, 34), and DHA exhibits a low bioavailability after oral administration, with a short elimination half-life (19, 34). Second, the ways of drug delivery to the parasite target tissue in vivo are obviously very different from those in in vitro situations. Third, Echinococcus metacestodes are surrounded by a highly glycosylated acellular laminated layer that exhibits immunomodulating properties (5), and it is not clear to what extent this barrier contributes to the action of antiparasitic drugs. Thus, the drugs and their metabolites used here were perhaps not delivered and accumulated in the parasite tissues in adequate quantities.

In contrast, the albendazole combination treatments resulted in consistently lower parasite weights than were found with albendazole monotherapy. This already represents a promising result. However, since the improvement narrowly missed statistical significance, there is ample room for optimization (modulation of application route, dosage, treatment duration, etc.). The slightly improved result after combination therapy could be due to the fact that the two drugs altered the pharmacokinetics of albendazole, thus retarding the metabolic conversion of the primary metabolite albendazole-sulfoxide to albendazole-sulfone. Similar findings were obtained during in vivo treatment of E. multilocularis-infected mice with albendazole-nitazoxanide combination therapy (29), albendazole-cimetidine (33), and albendazole-2-methoxyestradiol treatments (27). Novel synthetic artemisinin derivatives have been developed, which are characterized by improved pharmacokinetic profiles (16). Further studies are under way to elucidate the antiechinococcal efficacy of these and other molecules.

Acknowledgments

Norbert Mueller (Institute of Parasitology, University of Bern) is acknowledged for his great support and helpful comments and Britta Stadelmann for enthusiastic help in parasite cultivation. Artemisinins were a kind gift from the Swiss Tropical Institute in Basel or were purchased from Chemos GmbH (Regenstauf, Germany). We also acknowledge Christian Leumann (Dept. of Chemistry) for the synthesis of nitazoxanide.

This work was made possible through the Swiss National Science Foundation (31-111780) and the Novartis Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avery, M. A., K. M. Muraleedharan, P. V. Desai, A. K. Bandyopadhyaya, M. M. Furtado, and B. L. Tekwani. 2003. Structure-activity relationships of the antimalarial agent artemisinin. Design, synthesis, and CoMFA studies toward the development of artemisinin-based drugs against leishmaniasis and malaria. J. Med. Chem. 46:4244-4258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckert, J., and P. Deplazes. 2004. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:107-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golenser, J., J. H. Waknine, M. Krugliak, N. H. Hunt, and G. E. Grau. 2006. Current perspectives on the mechanism of action of artemisinins. Int. J. Parasitol. 36:1427-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordi, T., and E. I. Lepist. 2004. Artemisinin derivatives: toxic for laboratory animals, safe for humans? Toxicology Lett. 147:99-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottstein, B., and A. Hemphill. 14 March 2008, posting date. The host-parasite interplay. Exp. Parasitol. 119:447-452. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemphill, A., and S. L. Croft. 1997. Electron microscopy in parasitology, p. 227-268. In M. Rogan (ed.), Analytical parasitology. Springer-Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany.

- 7.Hemphill, A., and B. Gottstein. 1995. Immunology and morphology studies on the proliferation of in vitro cultivated Echinococcus multilocularis metacestodes. Parasitol. Res. 81:605-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hemphill, A., M. Spicher, B. Stadelmann, J. Mueller, A. Naguleswaran, B. Gottstein, and M. Walker. 2007. Innovative chemotherapeutical treatment options for alveolar and cystic echinococcosis. Parasitology 134:1657-1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemphill, A., M. Stettler, M. Walker, M. Siles-Lucas, R. Fink, and B. Gottstein. 2002. Culture of Echinococcus multilocularis metacestodes: an alternative to animal use. Trends Parasitol. 18:445-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemphill, A., and M. Walker. 2004. Drugs against echinococcosis. Drug Design Rev. 1:325-332. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiao, Y., C. M. Ge, Q. H. Meng, J. P. Cao, J. Tong, and S. J. Fan. 2007. Dihydroartemisinin is an inhibitor of ovarian cancer cell growth. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 28:1045-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones-Brando, L., J. D'Angelo, G. H. Poster, and R. Yolken. 2006. In vitro inhibition of Toxoplasma gondii by four new derivatives of artemisinin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:4206-4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keiser, J., R. Brun, B. Fried, and J. Utzinger. 2006. Trematocidal activity of praziquantel and artemisinin derivatives: in vitro and in vivo investigations with adult Echinostoma caproni. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:803-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keiser, J., X. Shu-Hua, X. Jian, C. Zhen-San, P. Odermatt, S. Tesana, M. Tanner, and J. Utzinger. 2006. Effect of artesunate and artemether against Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini in rodent models. Int. J. Antimocrob. Agents 28:370-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keiser, J., X. Shu-Hua, M. Tanner, and J. Utzinger. 2006. Artesunate and artemether are effective fasciolicides in the rat model and in vitro. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:1139-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keiser, J., and J. Utzinger. 2007. Food-borne trematodiasis: current chemotherapy and advances with artemisinins and synthetic trioxolanes. Trends Parasitol. 23:555-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klinkert, M. Q., and V. Heussler. 2006. The use of anticancer drugs in antiparasitic chemotherapy. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 6:131-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li, L. N., H. D. Zhang, S. J. Yuan, Z. Y. Tian, L. Wang, and Z. X. Sun. 2007. Artesunate attenuates the growth of human colorectal carcinoma and inhibits hyperactive Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Int. J. Cancer 121:1360-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, Q. G., J. O. Peggins, L. L. Fleckenstein, K. Masonic, M. H. Heiffer, and T. G. Brewer. 1998. The pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of dihydroartemisinin, arteether, artemether, artesunic acid and artelinic acid in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 50:173-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meshnick, S. R. 2002. Artemisinin: mechanisms of action, resistance and toxicity. Int. J. Parasitol.. 32:1655-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naguleswaran, A., M. Spicher, N. Vonlaufen, L. M. Ortega-Mora, P. Torgerson, B. Gottstein, and A. Hemphill. 2006. In vitro metacestodicidal activities of genistein and other isoflavones against Echinococcus multilocularis and Echinococcus granulosus. Antimicrb. Agents Chemother. 50:3770-3778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nontprasert, A., S. Pukrittayakamee, M. Nosten-Bertrand, S. Vanijanonta, and N. J. White. 2000. Studies of the neurotoxicity of oral artemisinin derivatives in mice. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62:409-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pawlowski, Z. S., J. Eckert, D. A. Vuitton, R. W. Ammann, P. Kern, P. S. Craig, K. F. Dar, F. De Rosa, C. Filice, B. Gottstein, F. Grimm, C. N. L. Macpherson, N. Sato, T. Todorov, J. Uchino, W. von Sinner, and H. Wen. 2001. Echinococcosis in humans: clinical aspects, diagnosis and treatment, p. 20-71. In J. Eckert, M. A. Gemmell, F. X. Meslin, and Z. S. Pawlowski (ed.), WHO/OIE manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals: a public health problem of global concern. World Organization for Animal Health and World Health Organization, Paris, France.

- 24.Reuter, S., A. Buck, B. Manfras, W. Kratzer, H. M. Seitz, K. Darge, S. N. Reske, and P. Kern. 2004. Structured treatment interruption in patients with alveolar echinococcosis. Hepatology 39:509-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reuter, S., B. Manfras, M. Merkle, G. Harter, and P. Kern. 2006. In vitro activities of itraconazole, methiazole, and nitazoxanide versus Echinococcus multilocularis larvae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2966-2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaohong, L., T. Kumagai., A. Qinghua, Y. Xiaolan, H. Ohmae, Y. Yabu, L. Siwen, W. Liyong, H. Maruyama, and N. Ohta. 2006. Evaluation of the anthelmintic effects of artesunate against experimental Schistosoma mansoni infection in mice using different treatment protocols. Parasitol. Int. 55:63-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spicher, M., A. Naguleswaran, L. M. Ortega, J. Mueller, B. Gottstein, and A. Hemphill. 2008. In vitro and in vivo effects of 2-methoxyestradiol, either alone or combined with albendazole, against Echinococcus metacestodes. Exp. Parasitol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Stettler, M., R. Fink, M. Walker, B. Gottstein, T. G. Geary, J. F. Rossignol, and A. Hemphill. 2003. In vitro parasiticidal effect of nitazoxanide against Echinococcus multilocularis metacestodes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:467-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stettler, M., J. F. Rossignol, R. Fink, M. Walker, B. Gottstein, M. Merli, R. Theurillat, W. Thormann, E. Dricot, R. Segers, and A. Hemphill. 2004. Secondary and primary murine alveolar echinococcosis: combined albendazole/nitazoxanide chemotherapy exhibits profound anti-parasitic activity. Int. J. Parasitol. 34:615-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stettler, M., M. Siles-Lucas, E. Sarciron, P. Lawton, B. Gottstein, and A. Hemphill. 2001. Echinococcus multilocularis alkaline phosphatase as a marker for metacestode damage induced by in vitro drug treatment with albendazole sulfoxide and albendazole sulfone. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2256-2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Utzinger, J., J. Keiser, X. Shuhua, M. Tanner, and B. H. Singer. 2003. Combination chemotherapy of schistosomiasis in laboratory studies and clinical trials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1487-1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker, M., J. F. Rossignol, P. Torgerson, and A. Hemphill. 2004. In vitro effects of nitazoxanide on Echinococcus granulosus protoscoleces and metacestodes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:609-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wen, H., R. R. New, M. Muhmut, J. H. Wang, Y. H. Wang, J. H. Zhang, Y. M. Shao, and P. S. Craig. 1996. Pharmacology and efficacy of liposome-entrapped albendazole in experimental secondary alveolar echinococcosis and effect of co-administration with cimetidine. Parasitology 113:111-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodrow, C. J., R. K. Haynes, and S. Krishna. 2005. Artemisinins. Postgrad. Med. J. 81:71-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou, H. J., W. Q. Wang, G. D. Wu, J. Lee, and A. Li. 2007. Artesunate inhibits angiogenesis and downregulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression in chronic myeloid leukemia K562 cells. Vasc. Pharmacol. 47:131-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]