Abstract

This paper reports dissociation constants and “effective molarities” (Meff) for the intramolecular binding of a ligand covalently attached to the surface of a protein by oligo(ethylene glycol) (EGn) linkers of different lengths (n = 0, 2, 5, 10, and 20), and compares these experimental values with theoretical estimates from polymer theory. As expected, the value of Meff is lowest when the linker is too short (n = 0) to allow the ligand to bind noncovalently at the active site of the protein without strain, is highest when the linker (n = 2) is the optimal length to allow such binding to occur, and decreases monotonically as the length increases past this optimal value (but, only by a factor of approximately eight from n = 2 to n = 20). These experimental results are not compatible with a model in which the single bonds of the linker are completely restricted when the ligand has bound non-covalently to the active site of the protein, but are quantitatively compatible with a model that treats the linker as a random-coil polymer. Calorimetry revealed that enthalpic interactions between the linker and the protein are not important in determining the thermodynamics of the system. Taken together, these results suggest that the manifestation of the linker in the thermodynamics of binding is exclusively entropic. The values of Meff are, theoretically, intrinsic properties of the EGn linkers, and can be used to predict the avidities of multivalent ligands with these linkers for multivalent proteins. The weak dependence of Meff on linker length suggests that multivalent ligands containing flexible linkers that are longer than the spacing between the binding sites of a multivalent protein will be effective in binding, and that the use of flexible linkers with length somewhat greater than the optimal distance between binding sites is a justifiable strategy for use in the design of multivalent ligands.

Introduction

The primary motivation for this paper was to determine the influence of the “linker”—the structural element that connects the binding moieties in a multivalent ligand—on the binding of a multivalent ligand to a multivalent protein (Figure 1E). As our model system, we adopted a ligand covalently tethered to the surface of a protein by oligo(ethylene glycol) linkers (EGn) (Figure 1D), because this design allows us to interrogate the system without complications from separate binding events of the two ends of the ligand; complications that do arise when both ends are free. We report dissociation constants (and effective molarities, see below) for the intramolecular binding of the tethered ligand to the active site of the protein as a function of the linker length (n), and discuss the data in the context of four possible models (Figure 2). We find that only one of these models (Figure 2B) is consistent with the following results: the linker plays an exclusively entropic role in the thermodynamics of the system, and it has significant conformational mobility even after the ligand is bound at the active site of the protein. The results are quantitatively well-explained by a model that describes the linker as a random-coil polymer (Figure 3); this model is one originally proposed by Lees and coworkers for a related problem, and estimates the probability of intramolecular binding as the probability that the ends of the linker are separated by a distance (d) equal to the separation of the sites of covalent attachment and non-covalent binding of the ligand to the protein (Figure 1D).1

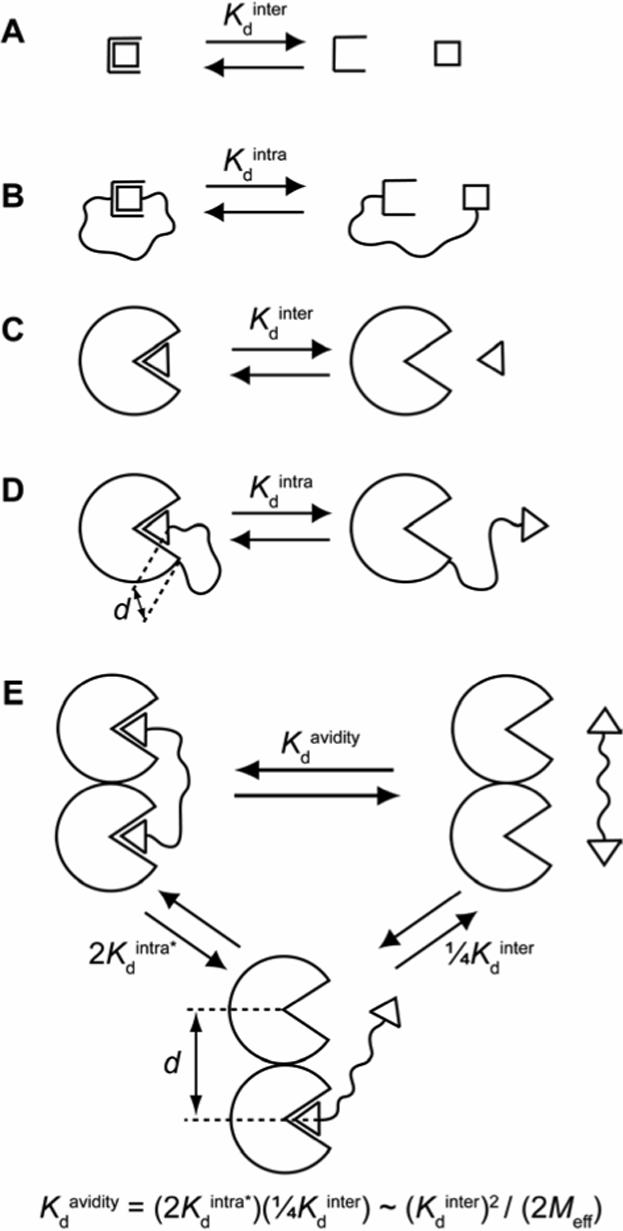

Figure 1.

(A) A monovalent binding event between a receptor and ligand is characterized by a dissociation constant (Kdinter) with units of concentration (M). (B) When the ligand is tethered to the receptor, the dissociation constant (Kdintra) is now dimensionless and is related to Kdinter by the effective molarity, Meff (eq 1). (C) Analogous to (A) for a binding event between a protein and ligand. (D) Analogous to (B) for an intramolecular protein-ligand binding event. In this case, however, the distance (d) between the two ends of the linker in the bound state is non-zero (unlike the case in (B)). (E) Dissociation of a bivalent ligand from a bivalent receptor. This process can be conceptualized as occurring in two steps: the first step (with dissociation constant 2Kdintra*) is intramolecular, and the second step (with dissociation constant ¼Kdinter) is intermolecular. The equation given provides a means of estimating Meff from the observed dissociation constant (Kdavidity) and the intermolecular dissociation constant (Kdinter) by assuming that the dissociation constant for the first step is equivalent to the product of a statistical factor of 2 and Kdintra (defined in (D); i.e., this procedure assumes that Kdintra* = Kdintra). This assumption is often quite poor because of complications arising from the influence of binding at one site on binding at the other site (e.g., cooperativity between binding sites, enthalpy/entropy compensation).4

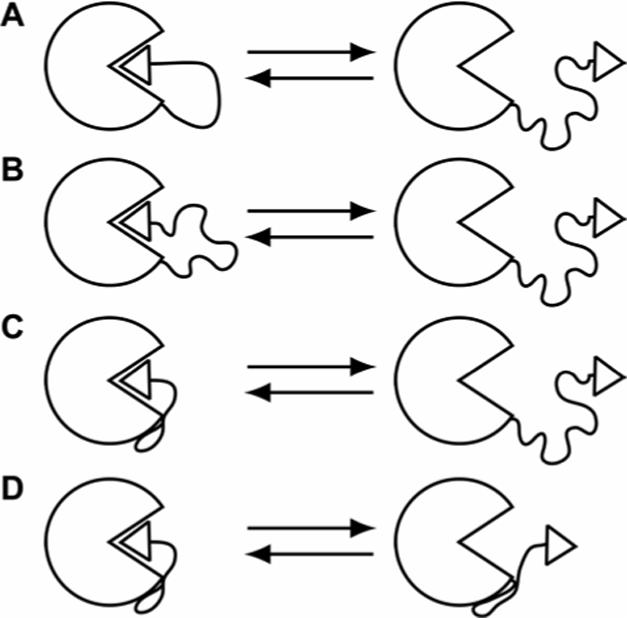

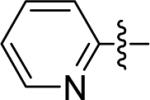

Figure 2.

Possible models to explain the binding of a ligand, covalently attached to the surface of a protein by the “linker”, to the active site of that protein. When the ligand is bound at the active site, the linker: (A) has low conformational mobility (i.e., free rotations of the bonds of the linker are significantly restricted), (B) has significant conformational mobility, or (C) and (D) makes stabilizing contacts with the surface of the protein. In (D), the linker makes contacts with the surface of the protein even when the ligand is not bound at the active site.

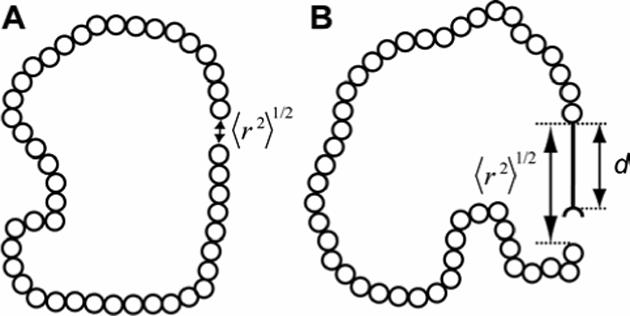

Figure 3.

Random-coil polymer with the number (n) of repeat units (represented as open circles) equal to 45. (A) The polymer forms a closed loop: the distance (〈r2〉1/2) between the ends of the polymer is near zero. (B) The polymer bears a physical pole of length (d) attached at one end. The distance (〈r2〉1/2) between the ends of the polymer is close to this defined distance (d).

Effective molarity (Meff) is an empirical term that is commonly used to relate the kinetics and equilibria of intramolecular and intermolecular reactions (both covalent and non-covalent) in chemistry (eq 1).2, 3 Kdinter, which has units of concentration (e.g., molarity), is the dissociation constant for an intermolecular reaction (Figure 1A) and Kdintra, which is dimensionless, is the dissociation constant for an analogous intramolecular reaction (Figure 1B). Meff depends on the length and flexibility of the “linker” between the two reactive groups.2, 3

| (1) |

Effective concentration (Ceff; units of concentration) is a theoretical parameter that allows the estimate of the rate and/or equilibrium for ring closure for intramolecular reactions (Figure 1B) by assuming that the linker between the two reactive groups behaves as a random-coil polymer (Figure 3A).3-7 It is essentially the probability that the two reactive groups (the two ends of the polymer) will be within an infinitesimal distance of one another (eq 2); NA is Avogadro's number and 〈r2〉1/2 is the root-mean-squared distance (in dm) between the ends of the polymer.

| (2) |

The parameter 〈r2〉1/2 can be estimated from polymer chemistry assuming a three-dimensional random flight (eq 3) where n is the number of segments in the chain and C is proportional to the distance (l) between two segments of the chain (this value is equal to the bond length for a freely-jointed polymer) and is characteristic of a given chain structure.5, 89 The proportionality constant C / l gives a measure of the stiffness of the chain and takes into account effects such as bond angles and rotational barriers; it typically varies from 1.5 for a very flexible chain to 5.5 for a very stiff one.5, 6

| (3) |

Winnik and Mandolini have reviewed the literature for ring closing (macrocyclization) reactions in small molecule systems, and concluded that Ceff and Meff are closely correlated for many of these reactions.3, 10

In many situations (and, in particular, in protein-ligand binding) we are not concerned with the probability that the two ends of the linker are an infinitesimal distance apart. Rather, we require the probability that the two ends are a distance (d) apart, where d is set by the system (Figures 1D,E and 3B). Lees and coworkers derived eq 4 for this case, where Ceff(0) is Ceff defined in eq 2.1 The parameter p arises because of the presence of the protein: the ligand cannot occupy the same space as the protein and because it is excluded from this volume, its Ceff increases (a so-called “excluded volume” effect). Lees and coworkers proposed a value of 2 for this term; this value assumes that the ligand has only a hemisphere of free access when constrained by the protein (Figure 1E), as compared to a sphere when it is free in solution.1

| (4) |

We have defined multivalency as multiple interactions (often of the same kind) between two different species.4, 11 Theoretical approaches to multivalency have assumed a step-wise pathway for dissociation, in which the first step is intramolecular (Figure 1E). The value of the dissociation constant (2Kdintra*) for this step has been challenging to estimate theoretically.4 Without an estimate for this parameter, we cannot predict multivalent avidities from component monovalent affinities (although the work by Lees, Reinhoudt, and others represents a significant advance toward this capability)1, 6, 7. The study presented here clarifies and simplifies this problem because we obtain empirical estimates for the dissociation constants for intramolecular protein-ligand binding that are applicable to the thermodynamics of the intramolecular step in multivalent binding (Figure 1D,E).

We have previously argued that flexible oligomers should not function effectively as linkers in multivalent ligands because of the severe loss in conformational entropy of the linker (TΔS○ ∼ RT ln 3 ∼ 0.7 kcal mol−1 per freely rotating single bond of the linker) when it is bound at both ends.4, 11, 12 Flexible linkers (e.g., oligo(ethylene glycol)) have, however, been used with success in multivalent ligands.4, 7, 11, 13 Determining how flexible linkers could work in multivalent ligands, when this simple theoretical model argues that they should not, was a key motivation for this paper.

Experimental Design

We selected the combination of human carbonic anhydrase II (HCA, EC 4.2.1.1) and p-substituted benzenesulfonamides as our model system, because it is the simplest one that we know for studying protein-ligand interactions: the conserved mode of binding of sulfonamides to HCA has been well-established by X-ray crystallography, there are a number of well-characterized assays to use in following binding, and there are a number of commercially available, high-affinity arylsulfonamides to use for competition experiments.14-17 Further, HCA is easy to over-express in, and purify from, E. coli culture in high yield; this ease allows the generation of HCA mutants with a chemical “handles” (i.e., reactive sites) to which to couple the ligands.18-20

An examination of crystal structures of HCA complexed with p-substituted benzenesulfonamides containing oligo(ethylene glycol) linkers (PDB: 1CNY, 1CNX, 1CNW)21 established that Lys-133 was spatially close to the terminus of the ligand but outside of the conical cleft of the enzyme (Figure 4). Mutating this residue to Cys would generate a chemical handle for thiol-selective coupling.18, 20 HCA has an endogenous Cys at position 206. In order to preclude side reaction at this site, we mutated it to Ser to generate a double mutant (Cys-206→Ser, Lys-133→Cys), which we refer to as HCA** in the remainder of this paper. Krebs and Fierke demonstrated that the C206S mutant of HCA is active,22 and Mårtensson et al. determined that this mutant is as stable as wild-type HCA.20

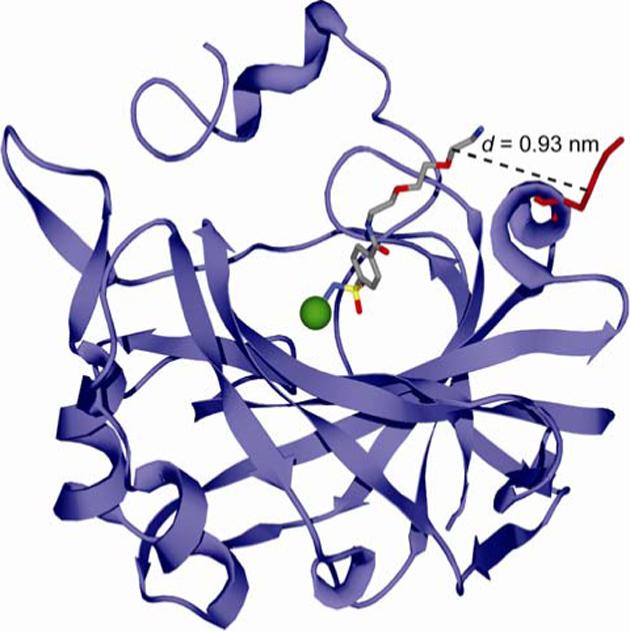

Figure 4.

Model for the interaction of p-H2NSO2C6H4CONH(CH2CH2O)2CH2CH2NH3+ (ArEG3NH3+) with HCA based on the deposited X-ray crystallographic coordinates (PDB: 1CNX).21 The arylsulfonamide ligand is rendered as a ball-and-stick model in CPK color scheme. HCA is depicted as a light blue ribbon diagram with the catalytically essential Zn2+ cofactor shown as a green sphere. Lys-133 of HCA II is represented as a red ball-and-stick model. The distance (d) between the last glycol unit of the ligand and the γ-CH2 group of Lys-133 (corresponding to the thiol in the Lys→Cys HCA** mutant) is indicated by the dashed line.

We decided to use p-substituted benzenesulfonamides with a conserved alkyl chain (p-H2NSO2C6H4CH2NHCO(CH2)4CO–) as our model ligands because benzenesulfonamides bind CA in an invariant orientation, and the alkyl chain should saturate the hydrophobic surface of the conical cleft of CA and orient the linker into solution.14, 21, 23-25 We selected oligo(ethylene glycol) (EGn) as the linker to tether the ligand to HCA** because it is one of the most common linkers in multivalent ligands.4, 11, 13 We wanted to understand how these flexible oligomers could be effective as linkers in multivalent ligands. Oligo(ethylene glycol) has been shown to be resistant to the non-specific adsorption of proteins when displayed on surfaces;26 this property should minimize complications from non-specific adsorption of the linker to the surface of the protein (Figure 2C,D).

We chose thiolate-disulfide interchange as a means of coupling the ligands to HCA** because this reaction is completely selective for thiols (vs. the various other chemical functionalities in proteins).27

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of Benzenesulfonamides Containing Activated Disulfides for Covalent Tethering to HCA**

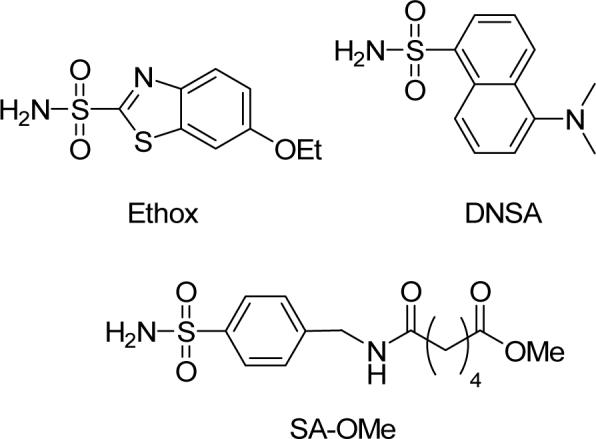

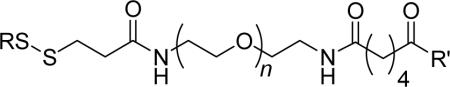

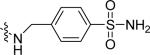

We synthesized disulfide-activated p-substituted benzenesulfonamides with oligo(ethylene glycol) linkers of different lengths (Pyr-SSEGnSA; n = 0, 2, 5, 10, and 20; Table 1) using conventional amide-bond coupling reactions (see Supporting Experimental Procedures for details). We used ligands containing disulfides activated with 2-pyridylthiol because the aromatic thiol is an excellent leaving group; thus, incubating the activated disulfide with HCA** should generate only the desired products (HCA**-SSEGnSA).28 We also synthesized two control molecules (Pyr-SSEGnCONH2 and SA-OMe) for our studies.

Table 1.

Chemical labels and modified HCA** proteins used in this study.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Name | R | R′ |

| Pyr-SSEGnSA |  |

|

| HCA**-SSEGnSA | HCA** |  |

| Pyr-SSEGnCONH2 |  |

NH2 |

| HCA**-SSEGnCONH2 | HCA** | NH2 |

Design and Purification of HCA II with a Surface-Accessible Cysteine Residue

We generated a vector encoding HCA** by conventional site-directed mutagenesis of the plasmid encoding the C206S mutant of HCA (pC206S), and inserted this mutated vector into the backbone of the plasmid encoding wild-type HCA (pACA; both pC206S and pACA were kind gifts of Professor Carol Fierke, University of Michigan).22, 29 We over-expressed HCA** in E. coli (BL21(DE3)) as described by Fierke and co-workers18 and purified it as described by Khalifah et al.19 We confirmed the purity of the enzyme by SDS-PAGE and its activity (∼100%) by measuring the amount of protein that could bind ethoxzolamide (Ethox), a specific inhibitor of CA (Figure S.1).17

Synthesis of Modified HCA** Proteins and Characterization of Conjugates

We treated HCA** with ∼5 equiv of one of five disulfide-activated ligands (Pyr-SSEGnSA, n = 0, 2, 5, 10, and 20) in Tris-sulfate buffer pH 8.0, and purified the conjugated proteins (HCA**-SSEGnSA, n = 0, 2, 5, 10, and 20) by exhaustive dialysis. We also synthesized two control proteins (HCA**-SSEG2CONH2 and HCA**-SCH2CO2−) by allowing HCA** to react with ∼10 equiv of Pyr-SSEG2CONH2 or iodoacetate (see the Experimental Section for details). The use of HCA**-SSEG2CONH2 established the influence of the linker minus the benzenesulfonamide moiety on binding. We used HCA**-SCH2CO2− for control studies (see below).

We characterized all of the modified proteins by ESI-MS and, in all cases, observed peaks corresponding to the combined masses of the protein and the reacted ligand (Table S.1). We examined the HCA**-SSEGnSA proteins by size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography (SE–HPLC) in order to determine whether a non-covalent dimer was present in any of the samples (Figure S.2). For HCA**-SSEGnSA with n = 2, 5, 10, and 20, we saw no evidence for a dimer at a concentration of protein of 20 μM. For HCA**-SSEG0SA (i.e., n = 0), we observed a peak (∼14% of total protein) corresponding in size to a dimer; this peak quantitatively dissociated in the presence of a large excess of Ethox (a high-affinity arylsulfonamide; see next section), and thus represents a non-covalent dimer that is stable on the time-scale of the analysis (∼25 min). As a stable, non-covalent dimer represents a minor contaminant for HCA**-SSEG0SA, and is not present for any of the other HCA**-SSEGnSA proteins, it should not complicate our analysis of dissociation constants (see next section).

We measured the affinity of a well-characterized fluorescent arylsulfonamide—dansylamide (DNSA)—for HCA**, HCA**-SCH2CO2−, and HCA**-SSEG2CONH2 (Figure S.3).16 The values of Kd for the three proteins were the same (Table 2); this observation suggests that the EGn linker itself has no effect on the binding of arylsulfonamides to the modified HCA** proteins, and that we can use HCA**-SCH2CO2− as a surrogate for HCA** for control studies because it is easier to handle (e.g., there is no need for added reductant and no possibility of dimer formation without the reductant).

Table 2.

Measured and calculated enthalpy and entropy values for intermolecular and intramolecular binding of sulfonamides to modified and unmodified HCA** proteins.

| Protein | Ligand | Kd × 106 | ΔGo kcal mol−1 | ΔHo kcal mol−1 | -TΔSo kcal mol−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCA** | DNSA | 0.30 ± 0.014a,b,c | −8.90 ± 0.15 | — | — |

| HCA**-SSEG2CONH2 | DNSA | 0.26 ± 0.008a,b,c | −8.98 ± 0.10 | — | — |

| HCA**-SCH2CO2− | DNSA | 0.23 ± 0.007a,b,c | −9.05 ± 0.10 | — | — |

| Ethox | 0.0002 ± 0.00004a,b,d | −13.2 ± 0.6 | −17.7 ± 0.4e,f | +4.5 ± 0.7 | |

| SA-OMe | 0.51 ± 0.018a,b | −8.58 ± 0.11 | — | — | |

| SA-OMe | 0.55 ± 0.03a,e | −8.54 ± 0.16 | −6.10 ± 0.12e,f | −2.4 ± 0.2 | |

| HCA**-SSEG10SA | Ethox | 6.1 ± 0.01a,e,g | −7.12 ± 0.08 | −11.0 ± 0.6e,f | +3.9 ± 0.6 |

| Intrah | 33 ± 7i | −6.1 ± 0.6 | −6.7 ± 0.7e,f | +0.6 ± 0.9 |

Units of M.

Measured by fluorescence either directly or through competition with DNSA.16, 17, 24, 25 Uncertainties are 95% confidence intervals from curve-fitting.

Compare to literature value of 0.3 μM for the binding of DNSA to a Cys-206→Ser mutant of HCA.22

Compare to literature value of 0.2 nM for the binding of Ethox to bovine carbonic anhydrase II.17

Measured by calorimetry.

Uncertainties were assumed to be due primarily to errors in the quantitation of titrant.30 An uncertainty of 2% of ΔHo was taken for the binding to HCA**-SCH2CO2− and 5% of ΔHo for the binding to HCA**-SSEG10SA.

Compare to value from fluorescence of 2.4 μM (Table 2).

Thermodynamic parameters are those for the intramolecular equilibrium shown in Figure 1D.

Dimensionless.

In order to determine the purity of the sulfonamide-conjugate proteins (HCA**-SSEGnSA), we examined the fluorescence of the protein (excitation wavelength = 290 nm, emission wavelength = 460 nm) when treated with 5 μM of DNSA; this concentration is ∼16-fold greater than the Kd of DNSA or HCA** (Table 2). The only fluorescent species under these conditions is the HCA**-DNSA complex. We assumed that any fluorescence observed was due to residual, unmodified HCA**, because all of the modified proteins have dissociation constants for DNSA too high to bind it at the concentration of DNSA used in the experiment (see below). We constructed a standard curve for the fluorescence of 5 μM of DNSA as a function of the concentration of HCA** and used it to interpolate the concentration of unmodified HCA** remaining in the coupling reactions (Figure S.4). Using these values and the concentrations of total HCA** protein from UV spectroscopy,31 we obtained purities of 90−95% for HCA**-SSEGnSA where n = 0, 2, 10, and 20 and ∼80% for n = 5 (see Supporting Experimental Procedures for details). This amount of contamination will not affect values of dissociation constants for these proteins (see next section).

For calorimetric studies where completely homogeneous protein was required, we purified the sulfonamide-conjugated protein (HCA**-SSEG10SA) over a column of benzenesulfonamide-conjugated agarose (see Supporting Experimental Procedures for details). Purities were ≥99% (assessed using the standard curve) after this procedure.

Measurement of Dissociation Constants of Ethoxzolamide (Ethox)

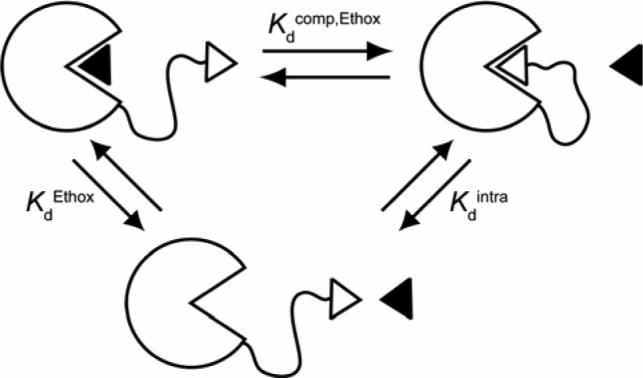

Ethox is a high-affinity ligand for CA that quenches ∼70% of the fluorescence of the Trp residues of the enzyme (so-called “intrinsic” protein fluorescence), and thus offers a spectrophotometric method of following binding and determining values of Kd (Figure S.1B).17 We treated HCA**-SSEGnSA (n = 0, 2, 5, 10, and 20) and HCA** (incubated with 2 equiv of SA-OMe) with different concentrations of Ethox and followed the fluorescence of the free, unbound protein (excitation wavelength = 290 nm, emission wavelength = 340 nm) to determine dissociation constants (Figure 5). Figure 6 shows the normalized data and fits to the data assuming a single-site binding model (see Experimental Section). As linker length (n) increased, Kdcomp,Ethox (Figure 5) for HCA**-SSEGnSA reached a peak when n = 2, and then decreased. The magnitude of the decrease in Kdcomp,Ethox was only weakly dependent on n (only a ∼8-fold decrease from n = 2 to n = 20; Table 3).

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram depicting the strategy for the measurement of Kdintra for HCA**-SSEGnSA using the observed dissociation constant (Kdcomp,Ethox) for a competing ligand, Ethox (shown as black triangle). For this thermodynamic cycle, Kdintra = KdEthox / Kdcomp,Ethox (eq 5).

Figure 6.

Decrease in fluorescence of modified HCA** proteins (HCA**-SSEGnSA, n = 0, 2, 5, 10, or 20) and HCA** (incubated with two equiv of SA-OMe) with increasing concentration of ethoxzolamide (Ethox). The intrinsic fluorescence of 200 nM of protein in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5 at 298 K with different concentrations of the fluorescence quencher Ethox was measured (excitation wavelength = 290 nm, emission wavelength = 340 nm). The data are shown after background subtraction, correction for the inner filter effect, and normalization to a maximum signal of unity (see Experimental Section). The solid curves are fits to the data using the full quadratic equation for binding (eq 7; this equation does not make the assumption that [Ethox]free ≈ [Ethox]total), and using a value for the minimum in fluorescence intensity of all samples of 0.3 (Figure S.1B). Error bars represent the maximum variation of an independent measurement from the mean of four experiments (duplicates from two independent experiments). Inset: The data on a logarithmic scale for the x-axis. The solid curves are fits to the data using a single-site Langmuir binding model (eq 8), which makes the assumption that [Ethox]free ≈ [Ethox]total — a poor assumption when n = 0 or 20 (see Experimental Section).

Table 3.

Experimental and theoretical values for the intermolecular and intramolecular binding of sulfonamides to sulfonamide-conjugated HCA** proteins (HCA**-SSEGnSA).

| n | Kdcomp,Ethox (μM)a | Kdintra × 105b | Meff(mM)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.31 ± 0.015 | 66 ± 14 | 0.8 ± 0.16 |

| 2 | 10 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 26 ± 5 |

| 5 | 5.6 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.8 | 14 ± 3 |

| 10 | 2.4 ± 0.17 | 8.3 ± 1.8 | 6.1 ± 1.3 |

| 20 | 1.2 ± 0.08 | 17 ± 4 | 3.1 ± 0.7 |

Observed dissociation constants for the binding of Ethox to HCA**-SSEGnSA (Figure 5). Uncertainties are 95% confidence intervals from curve-fitting.

Calculated dissociation constants for the binding of the tethered ligand to the active site of HCA (Figure 5). Uncertainties were propagated from uncertainties in Kdcomp,Ethox and KdEthox (see Table 2).

Calculated using eq 1. Uncertainties were propagated from uncertainties in Kdintra and Kdinter (see Table 2).

To account for the presence of unmodified HCA** in the HCA**-SSEG5SA sample (see previous section), we normalized the fluorescence data (Figure 6) to the intensity observed when [Ethox] = 40 nM (this concentration is sufficient to saturate the binding sites of all of the residual unmodified HCA**). Given the high value of Kdcomp,Ethox (5.6 μM) observed for this protein, <1% of the HCA**-SSEG5SA in the sample will bind Ethox at this concentration.

The fluorescence of HCA** that had been incubated with ∼2 equiv of SA-OMe (the ligand that was covalently tethered to HCA** in the modified proteins HCA**-SSEGnSA) decreased linearly with increasing concentrations of Ethox until a stoichiometric amount of Ethox was present (Figure 6). This result demonstrates that the presence of free, unbound SA-OMe could not explain the observation that the affinity of Ethox is much lower for HCA**-SSEGnSA than for HCA**, and that the value of KdEthox (Figure 5) for HCA** is too low to be determined directly by this method (i.e., the value of KdEthox for HCA** is much lower than the concentration of protein, ∼200 nM, required for a detectable signal from intrinsic fluorescence).

To determine the value of KdEthox, we allowed Ethox and DNSA (5 μM) to compete for the active site of HCA**-SCH2CO2− and measured the decrease in fluorescence of the HCA**-SCH2CO2−-DNSA complex (excitation wavelength = 290 nm, emission wavelength = 460 nm) with increasing concentration of Ethox (Figure S.5; Table 2).16, 24, 25 The value we obtained (KdEthox = 0.2 nM) was in good agreement with one from the literature (Table 2).17 We used the same competition experiment with DNSA to determine the value of the dissociation constant of SA-OMe (Kdinter = 0.51 μM; Figure 1C and eq 1) for HCA**-SCH2CO2− (Figure S.5; Table 2).

Measurement of Kdintra and Calculation ofMeff

Eq 5 gives the dissociation constant (Kdintra) for the intramolecular binding of the tethered ligand to the active site of HCA for HCA**-SSEGnSA from a thermodynamic cycle for the binding of Ethox to HCA**-SSEGnSA (Figure 5). Values of Kdcomp,Ethox (for HCA**-SSEGnSA) and KdEthox (for HCA**-SCH2CO2−) were measured as described in the previous section. Table 3 lists the calculated values of Kdintra.

| (5) |

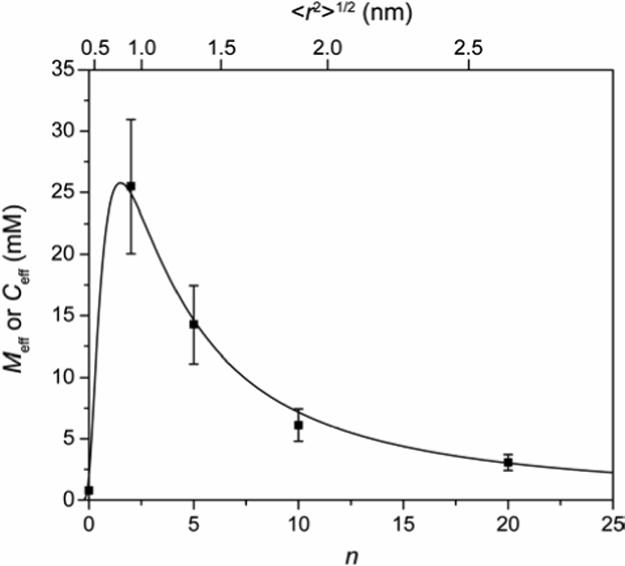

Table 3 also lists values of Meff calculated using eq 1, and values of Kdintra and Kdinter (the dissociation constant for the binding of SA-OMe to HCA**-SCH2CO2−; see previous section and Figure 1C,D). Meff was only weakly dependent on linker length (n) when n ≥ 2: a decrease of approximately a factor of 8 between n = 2 and n = 20. The model shown in Figure 2A anticipates a much greater dependence of Meff on n than that observed: the simplest model, which assumes that each single bond in an EG unit of the linker has three possible conformations before binding and only one after binding, anticipates a >10-fold decrease in Meff per EG unit (see Introduction).4, 11, 12 This model is inconsistent with the weak dependence of Meff on n observed experimentally, and can be eliminated.

Theoretical Values of Ceff for Intramolecular Binding of Sulfonamide-Conjugated HCA** (HCA**-SSEGnSA)

As mentioned in the section on Experimental Design, the “ligand” in HCA**-SSEGnSA consists of the benzenesulfonamide moiety and the alkyl chain that is directly attached to it (p-H2NSO2C6H4CH2NHCO(CH2)4CO–); thus, the linker consists of the EGn chain and the remainder of the alkyl chain (–NH(CH2CH2O)nCH2CH2NHCOCH2CH2S–). Treating the linker as a copolymer allowed us to estimate a value for 〈r2〉1/2 from the sum of the contributions from the EGn and the non-EGn portions of the linker (eq 6).8 For the EGn portion of the linker, we used a literature value of 0.58 nm for the parameter C in eq 3.32 We assumed that the non-EGn portion of the linker was “alkyl-like” and contributed a constant value of 0.40 nm to the linker length.33

| (6) |

In order to estimate Ceff (eq 4), we need a value for the distance (d) between the sites of covalent attachment of the ligand to the protein and of the ligand bound at the active site (Figure 1D). There are no reported X-ray crystal structures of complexes of HCA with p-substituted benzenesulfonamides with alkyl tails, so we examined the crystal structure of a complex of HCA with a p-substituted benzenesulfonamide having a tri(ethylene glycol) tail (ArEG3NH3+; Figure 4): we assumed that the alkyl chain of the ligand in HCA**-SSEGnSA interacts with the same hydrophobic patch of CA, and has the same orientation in the active site as the EG3 tail in ArEG3NH3+. From the crystal structure, we estimated a distance of ∼0.9 nm between the first methylene group of the third glycol unit of ArEG3NH3+—a position that should correspond to the –NH– group of the linker in HCA**-SSEGnSA—and the γ-carbon of Lys-133 of HCA—a position that should correspond to the thiol of HCA** (Figure 4).

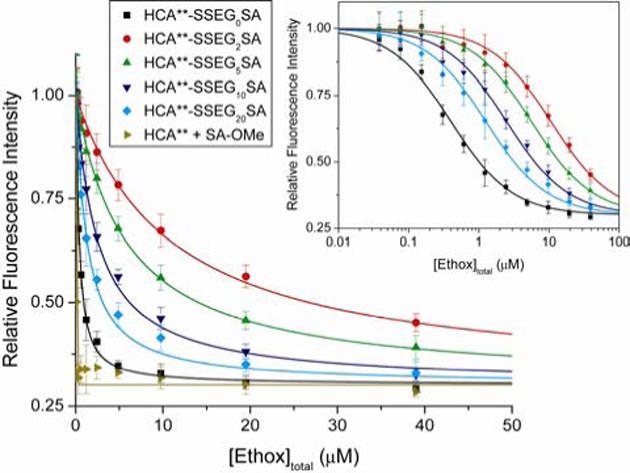

Figure 7 shows our experimental values of Meff (see previous section) and a fit to the data calculated using eq 4 for Ceff and eq 6 for 〈r2〉1/2. We allowed the values of d and p to vary in order to optimize the fit. The value of d (0.82 ± 0.03 nm) that gave the best least-squares fit to the data is very close to the value (0.9 nm) that we determined from analyzing the X-ray crystal structure of the HCA-ArEG3NH3+ complex (Figure 4). This observation, together with the excellent fit to the experimental data, suggests that the theoretical model based on polymer theory successfully (if unexpectedly) rationalizes the dependence of the intramolecular binding of the tethered ligand to the active site of the protein, as a function of the length of the variable part of the linker. Further, because the theory from which Ceff is derived explicitly ignores enthalpic contributions to ring closure, these observations suggest that entropy is dominant in intramolecular binding (see the next section for further discussion).

Figure 7.

Variation of effective concentration (Ceff) and effective molarity (Meff) with linker length (n; related to the root-mean-squared distance between the ends of the linker 〈r2〉1/2, see eq 6) for HCA**-SSEGnSA. The points are empirical values of Meff (eq 1) from this study (Table 3). The solid curve is a fit to the data using the definition of Ceff (eq 4) with estimates of 〈r2〉1/2 from eq 6. The best fit to the data was obtained with a value for d (the distance between the site of covalent attachment of the ligand to the protein and the active site of the protein; Figure 4) of 0.82 ± 0.03 nm, and for p of 0.12 ± 0.009.

The value of p (0.12 ± 0.009; eq 4) that gave the best fit to the data is significantly lower than the value of 2 proposed by Lees and coworkers for the bivalent protein-ligand complex (Figure 1E).1 Because the point of attachment of the benzenesulfonamide ligands to HCA for HCA**SSEGnSA is at the periphery of the conical cleft (Figure 1D and 4), the ligand will encounter less steric repulsion with the protein (when it is not bound at the active site of CA) than the unbound ligand in the intermediate state in a bivalent protein-ligand complex (Figure 1E). This effect can decrease the value of p to no less than unity—the unbound ligand has a full sphere of volume to explore, and is in a similar environment to a polymer that is free in solution. At present, we do not have a clear understanding of what effect could contribute the additional 8-fold decrease in p. We speculate that the geometry of the catalytic cleft of CA (∼1.5 nm deep and conical; Figure 4) could result in the polymer being excluded from the cleft because of steric interaction; this excluded volume effect would lower p (and Ceff).

Calorimetric Investigation to Determine Enthalpy and Entropy of Binding for Kdintra

Our previous work suggested that EGn tails interacted with a hydrophobic patch in the conical cleft of CA, albeit with no effect on the observed dissociation constants.21, 24 We have recently shown that increasing the length of these tails makes the enthalpy of association of these ligands with CA more favorable, and the entropy less favorable, in a way that perfectly balances to give no change in values of Kd.30 As mentioned in the section on Experimental Design, we designed HCA**-SSEGnSA to include a conserved alkyl chain to saturate this hydrophobic surface in the conical cleft of the enzyme. Thus, we would not anticipate that contacts between the EGn linker and the surface of HCA could occur (Figure 2C,D).

To test this idea, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to dissect the intramolecular dissociation constant (Kdintra; Figures 1D, 2, and 5) for HCA**-SSEG10SA into its enthalpic (ΔH○intra) and entropic (ΔS○intra) components. We examined the binding of Ethox to HCA**-SSEG10SA (Figure S.6) and to the control protein HCA**-SCH2CO2− (Figure S.7A). We calculated ΔH○intra and ΔS○intra for HCA**-SSEG10SA by making use of the thermodynamic cycle shown in Figure 5 (Table 2). The value of Kdcomp,Ethox that we measured by ITC for the binding of Ethox to HCA**-SSEG10SA was in good agreement (a difference of a factor of 2−3) to the one that we measured by fluorescence quenching (Tables 2 and 3).

The value of ΔH○intra for HCA**-SSEG10SA (−6.7 ± 0.7 kcal mol−1; Table 2) was the same, within error, as ΔH○obs for the binding of SA-OMe (a ligand containing the benzenesulfonamide moiety and alkyl chain of HCA**-SSEG10SA) to HCA**-SCH2CO2− (−6.1 ± 0.12 kcal mol−1; Figure S.7B and Table 2). This result suggests that there is little, if any, interaction of the EGn linker with the protein: our previous results suggested that any interaction of the EGn chain with CA should occur with a measurable change in enthalpy.30 Thus, this result serves to rule out the model shown in Figure 2C.

There remains the possibility that the linker makes stabilizing contacts with the protein whether the ligand is bound or not bound at the active site (Figure 2D), and thus there would be no change in enthalpy for these contacts between the two states. We cannot rigorously rule out this possibility. The fact that a theory from polymer chemistry that is based entirely on entropic terms fits the experimental data very well (Figure 7), however, persuades us to prefer the simpler model shown in Figure 2B.

Conclusions

This paper reports values of effective molarity (Meff) as a function of the length (n) of linkers of oligo(ethylene glycol) for a ligand covalently tethered to a protein (Figure 2). Values of Meff reach a maximum when the linker is the optimal length to allow the ligand to bind to the active site of the protein, and then decrease weakly with increasing linker length (decrease in Meff by only a factor of ∼8 over the range n = 2 to n = 20) beyond this value (Figure 7). The experimental data are well-explained by a theoretical, entropic model from polymer chemistry based on the probability that the ends of the linker are separated by the same distance as the sites of covalent attachment and of noncovalent binding of the tethered ligand. Calorimetry revealed that enthalpic contacts of the linker with the protein are not important in this system, and that entropy is dominant (Table 2; Figure 2C,D).

Our results suggest that, at least in the case of oligo(ethylene glycol) linkers, contacts of the linker with the surface of the protein (outside of the active site) can be safely ignored. These results are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated that surfaces displaying oligo(ethylene glycol) groups did not adsorb proteins non-specifically.26 These results can be reconciled with our previous findings that suggested an interaction of oligo(ethylene glycol) tails with CA: in these previous studies the tails interacted with a surface of the protein inside the conical cleft of CA.21, 30 This possibility is precluded for the ligands studied here (HCA**-SSEGnSA) because they have alkyl chains of sufficient length to saturate this hydrophobic surface.

Most importantly, our results are not consistent with a model in which the linker is completely restricted upon association of the ligand with the active site of the protein (when the linker is bound at both ends; Figure 2A). This model requires that Meff decrease sharply with the length of the linker (>10-fold decrease with each ethylene glycol unit); an expectation that is not met by the experimental results. Our results support a model in which the linker has significant conformational mobility when bound at both ends (Figure 2B).

The values of Meff reported here should be intrinsic properties of the oligo(ethylene glycol) linkers themselves. These values can, thus, be used to predict the avidities of multivalent ligands containing oligo(ethylene glycol) linkers for a multivalent protein, if the monovalent affinity is known (Figure 1E). Our results suggest, however, that the quantitative accuracy of these predictions is limited by difficulties in estimating the influence of such effects as the “excluded volume” term and the geometric and steric demands of the active site of the protein target on ligand binding (both of which appear in the parameter p in eq 4).

We did not anticipate the weak dependence of Meff on the length of the linker (when it is longer than the optimal length). This weak dependence suggests that the most effective strategy for the design of multivalent ligands will connect the ligand moieties by a flexible linker that is significantly longer than the spacing between the multivalent sites of the target protein (Figure 1E). Our results suggest that the penalty in conformational entropy for such a linker in the association of these multivalent ligands with their multivalent proteins will be low (and much lower than we previously hypothesized4, 11, 12). Indeed, the results presented here using oligo(ethylene glycol) linkers, which do not interact with the surfaces of proteins, can be seen as a worst-case scenario. Other types of linkers (e.g., alkyl chains) are likely to interact with the surfaces of proteins, and these interactions should effectively “shorten” the linker and make Meff even less sensitive to the length of the linker than in the results presented here (Figure 2C,D).

Finally, ligands with flexible linkers can adopt a number of conformations without steric strain (unlike ligands with rigid linkers); this flexibility should allow the multivalent ligand to sample conformational space to optimize its binding to the multiple binding sites. This sampling of conformational space reduces the possibility of a sterically obstructed fit, a circumstance that can occur readily with rigid linkers that are not perfectly designed.4

Experimental Section

General Methods

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), Aldrich Milwaukee, WI), or Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA) and used without further purification, unless otherwise noted. DNSA was recrystallized from ethanol prior to use. DNA sequencing was performed by the DNA sequencing facility at the Harvard University Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology. Fluorescence measurements were performed on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 for detection at 340 nm (intrinsic protein fluorescence for Ethox binding assays), and on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax Gemini XS for detection at 460 nm (for DNSA binding assays). Isothermal titration calorimetry was performed using a VP-ITC microcalorimeter from MicroCal (Northampton, MA). Varian Inova spectrometers operating at 400 MHz and 500 MHz (1H) were used for NMR experiments. UV-Vis spectroscopy was conducted on a Hewlett Packard 8453 spectrophotometer (Palo Alto, CA). UV spectroscopy was used to quantify HCA** proteins (ε280 = 54,000 M−1 cm−1)31 and DNSA (ε326 = 4640 M−1 cm−1)25. Ethox and SA-OMe were quantified by 1H NMR spectroscopy.24, 25, 30, 34

Preparation of Plasmid Encoding HCA**

The plasmids encoding wild-type HCA II (pACA) and a Cys-206→Ser mutant of HCA II (pC206S) were gifts from Professor Carol Fierke)22, 29 The Lys-133→Cys mutation was introduced into the pC206S plasmid using oligonucleotide site-directed mutagenesis with a Quickchange Mutagenesis Kit (Strategene) and following the manufacturer's directions. This plasmid was digested with the restriction enzymes BamHI and KasI (New England BioLabs), purified by agarose gel electrophoresis using a Quick Gel extraction kit (Qiagen), and ligated into the pACA backbone, which had been digested with BamHI and KasI, treated with CIP (calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase from New England BioLabs; to prevent re-circularization of the vector without the insert), and purified by gel electrophoresis. The presence of the desired mutation was verified by sequencing the entire HCA II gene using the method of Sanger et al.35

Expression and Purification of HCA**

BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with the HCA** plasmid and grown as described by Fierke and coworkers (see, for example, ref 18). Cell lysates were prepared as described by Krebs and Fierke,22 and the HCA** protein was purified using sulfonamide-conjugated agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) as described by Khalifah et al.19 The purified HCA** protein was stored at −80 °C in 50 mM Tris-sulfate buffer pH 8.0 with 0.2 mM ZnSO4 and 1 mM DTT (to prevent oxidation of the thiol).

Preparation of Modified HCA** Proteins

HCA** was desalted over a NAP-10 column (Amersham) into 50 mM Tris-sulfate buffer pH 8.0 from which oxygen had been removed by bubbling Ar through it for >1 h. HCA** (50−100 μM) was treated with 5−10 equiv of the appropriate modifying agent (Pyr-SSEGnSA, Pyr-SSEG2CONH2, or iodoacetate) to generate the desired modified HCA** (HCA**-SSEGnSA, HCA** -SSEG2CONH2, or HCA**-SCH2CO2−, respectively). The reaction was allowed to proceed for 1 h at 25 °C and then for ∼18 h at 4 °C. The reaction products were purified by exhaustive dialysis, and then characterized by ESI-MS (electrospray ionization mass spectrometry) to verify the appearance of a peak corresponding to the combined masses of HCA** and the chemical reactant (see Table S.1). For the HCA**-SSEGnSA proteins, contamination by unmodified HCA** was assessed by examining the binding of DNSA (see Supporting Experimental Procedures and Figure S.4).

Determination of Dissociation Constants (Kdcomp,Ethox) for the Binding of Ethox to HCA**-SSEGnSA

To the wells of a black microwell plate were added dilutions of Ethox and then the appropriate HCA** protein (200 nM) in a final volume of 200 μL of 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5. The plate was allowed to incubate at 25 °C for 2 h, and then its fluorescence was measured with an excitation wavelength of 290 nm and an emission wavelength of 340 nm (with a 325 nm cut-off filter). Wells were read ∼50 times. Fluorescence intensities were normalized to the fluorescence intensity of the protein with no added Ethox, and then corrected for the inner filter effect36 by using a control experiment where soybean trypsin inhibitor (a protein with no affinity for sulfonamides)37 was treated with Ethox. The corrected data were fit to eq 7 where [CA]total is the total concentration of modified HCA** in the assay (200 nM) and [Ethox]total is the total concentration of Ethox (the independent variable). Only the parameter Kdcomp,Ethox was allowed to vary to optimize the fit by non-linear least squares fitting (Origin), with the other parameters held constant at their known values.

| (7) |

Eq 7 assumes that Ethox quenches 70% of the fluorescence of HCA**; this value was determined by examining the fluorescence of HCA** in the presence of Ethox (Figure S.1B).

The data were also fit to eq 8, which assumes that the concentration of Ethox not bound by CA is equal to the total concentration of Ethox ([Ethox]total) and gives a sigmoid fit to the data when the concentration of Ethox is plotted on a logarithmic scale. This equality is not true for HCA**SSEG0SA and HCA**SSEG20SA, because in those cases Kdcomp,Ethox ∼ [CA]total (200 nM).

| (8) |

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

In order to determine values of ΔH○ and Kd, ∼6 μM HCA**-SCH2CO2− or ∼60 μM HCA**-SSEG10CA, which had been purified over sulfonamide-conjugated agarose (see Supporting Experimental Procedures), in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5 (with 0.6% DMSO-d6) was titrated with 120 or 440 μM, respectively, of Ethox in the same buffer at 25 °C. HCA**-SCH2CO2− (∼6 μM) was also titrated with 120 μM of SA-OMe. See Figures S.6 and S.7 for detailed information. After subtraction of background heats, the data were analyzed by a single-site binding model using the Origin software (provided by Microcal) and allowing the values of binding stoichiometry, ΔH○, and Kd to vary to optimize the fit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM30367). V.M.K. and P.J.B. acknowledge support from NDSEG and NSF pre-doctoral fellowships, respectively. V.S. acknowledges support from La Ligue Contre Le Cancer (France). We thank Professor Carol Fierke (University of Michigan) for the kind gift of the HCA-encoding plasmids, and Andrea Stoddard (Fierke group, Michigan) for helpful discussions about protein purification. We thank Dr. Julian P. Whitelegge (The Pasarow Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, University of California, Los Angeles) for ESI-MS analysis. We thank Professor Greg Verdine (Harvard University) for use of the Spectramax M5, and Marie Spong (Verdine group, Harvard) for helpful discussions about molecular biology. We acknowledge the Bauer Center for Genomics Research (Harvard University) for the use of the Spectramax Gemini XS and Perspective Biosystems Voyager-DE PRO for MALDI.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic procedures and characterization, assay protocols, SDS-PAGE and assessment of activity of HCA**, mass spectra and SE–HPLC chromatograms of modified HCA** proteins, fluorescence titration curves for the binding of DNSA to control HCA** proteins, fluorescence calibration plot for determining purity of HCA**-SSEGnSA proteins, fluorescence titration curves for determination of Kd of SA-OMe and Ethox to HCA**-SCH2CO2−, and ITC thermograms for the binding of Ethox and SA-OMe to HCA**-SCH2CO2− and to HCA**-SSEG10SA. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Gargano JM, Ngo T, Kim JY, Acheson DWK, Lees WJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12909–12910. doi: 10.1021/ja016305a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Page MI, Jencks WP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1971;68:1678–1683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.8.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Page MI. Chem. Soc. Rev. Vol. 2. 1973. pp. 295–323. [Google Scholar]; c Kirby AJ. In: Adv. Phys. Org. Chem. Gold V, Bethell D, editors. Vol. 17. Academic Press; London: 1980. pp. 183–278. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandolini L. In: Adv. Phys. Org. Chem. Gold V, Bethell D, editors. Vol. 22. Academic Press; London: 1986. pp. 1–111. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnamurthy VM, Estroff LA, Whitesides GM. In: Fragment-based Approaches in Drug Discovery. Jahnke W, Erlanson DA, editors. Vol. 34. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2006. pp. 11–53. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobson H, Stockmayer WH. J. Chem. Phys. 1950;18:1600–1606. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mulder A, Auletta T, Sartori A, Del Ciotto S, Casnati A, Ungaro R, Huskens J, Reinhoudt DN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6627–6636. doi: 10.1021/ja0317168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer RH, Karpen JW. Nature. 1998;395:710–713. doi: 10.1038/27227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flory PJ. Principles of Polymer Chemistry. Cornell University Press; Ithaca, NY: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 9.In order for the theory to apply, the polymer must be long enough to eliminate the possibility of non-ideal effects (e.g., the non-Gaussian nature of short chains, correlations between bond angles of different subunits, transannular steric effects; see refs 5 and 10). Jacobson and Stockmayer have argued that this minimum length is on the order of 15 atoms in the chain, but the exact length depends on the flexibility and structure of the polymer (see ref 10).

- 10.Winnik MA. Chem. Rev. 1981;81:491–524. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mammen M, Choi S-K, Whitesides GM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1998;37:2755–2794. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981102)37:20<2754::AID-ANIE2754>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mammen M, Shakhnovich EI, Whitesides GM. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3168–3175. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi S-K. Synthetic Multivalent Molecules: Concepts and Biomedical Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14.a Urbach AR, Whitesides GM. in preparation.; b Christianson DW, Fierke CA. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996;29:331–339. [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Supuran CT, Scozzafava A, Casini A. Med. Res. Rev. Vol. 23. 2003. pp. 146–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Supuran CT, Scozzafava A; In: Carbonic Anhydrase: Its Inhibitors and Activators. Supuran CT, Scozzafava A, Conway J, editors. Vol. 1. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2004. pp. 67–147. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen RF, Kernohan JC. J. Biol. Chem. 1967;242:5813–5823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kernohan JC. Biochem. J. 1970;120:26P. doi: 10.1042/bj1200026p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burton RE, Hunt JA, Fierke CA, Oas TG. Protein Sci. 2000;9:776–785. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.4.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalifah RG, Strader DJ, Bryant SH, Gibson SM. Biochemistry. 1977;16:2241–2247. doi: 10.1021/bi00629a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mårtensson L-G, Jonsson B-H, Freskgård P-O, Kihlgren A, Svensson M, Carlsson U. Biochemistry. 1993;32:224–231. doi: 10.1021/bi00052a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boriack PA, Christianson DW, Kingery-Wood J, Whitesides GM. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:2286–2291. doi: 10.1021/jm00013a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krebs JF, Fierke CA. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;269:948–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.a Gao J, Qiao S, Whitesides GM. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:2292–2301. doi: 10.1021/jm00013a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b King RW, Burgen ASV. Proc. R. Soc. London, B. 1976;193:107–125. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1976.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cappalonga Bunn AM, Alexander RS, Christianson DW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:5063–5068. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain A, Huang SG, Whitesides GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:5057–5062. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain A, Whitesides GM, Alexander RS, Christianson DW. J. Med. Chem. 1994;37:2100–2105. doi: 10.1021/jm00039a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.a Prime KL, Whitesides GM. Science. 1991;252:1164–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Prime KL, Whitesides GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:10714–10721. [Google Scholar]; c Mrksich M, Whitesides GM. In: Poly(ethylene Glycol): Chemistry and Biological Applications. 1st ed. Harris JM, Zalipsky S, editors. Vol. 680. American Chemical Society; Washington, D. C.: 1997. pp. 361–373. [Google Scholar]

- 27.a Gilbert HF. In: Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. Meister A, editor. Vol. 63. Wiley; New York: 1990. pp. 69–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lees WJ, Whitesides GM. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:642–647. [Google Scholar]; c Erlanson DA, Wells JA, Braisted AC. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2004;33:199–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.140409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Erlanson DA, Braisted AC, Raphael DR, Randal M, Stroud RM, Gordon EM, Wells JA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:9367–9372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Erlanson DA, Hansen SK. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlsson J, Drevin H, Axén R. Biochem. J. 1978;173:723–737. doi: 10.1042/bj1730723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nair SK, Calderone TL, Christianson DW, Fierke CA. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:17320–17325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krishnamurthy VM, Bohall BR, Semetey V, Whitesides GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5802–5812. doi: 10.1021/ja060070r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyman PO, Lindskog S. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1964;85:141–151. doi: 10.1016/0926-6569(64)90174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knoll D, Hermans J. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:5710–5715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.There are a seven single bonds in the non-EGn portion of the linker (between the thiol of the linker and the –NH– of the carboxamide closest to the alkyl chain of the ligand). Using eq 3 with an estimate for l of 0.153 nm (the C-C bond length) and assuming an ideal, random-flight polymer (C / l = 1), gives an estimate of ∼0.4 nm for the value of the non-EGn portion of the linker.

- 34.Krishnamurthy VM, Bohall BR, Kim C-Y, Moustakas DT, Christianson DW, Whitesides GM. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 2nd ed. Kluwer Academic/Plenum; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colton IJ, Carbeck JD, Rao J, Whitesides GM. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:367–382. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150190303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.