Abstract

Neuronal activity is critically important for development and plasticity of dendrites, axons and synaptic connections. Although Ca2+ is an important signal molecule for these processes, not much is known about the regulation of the dendritic Ca2+ concentration in developing neurons. Here we used confocal Ca2+ imaging to investigate dendritic Ca2+ signalling in young and mature hippocampal granule cells, identified by the expression of the immature neuronal marker polysialated neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM). Using the Ca2+-sensitive fluorescent dye OGB-5N, we found that both young and mature granule cells showed large action-potential evoked dendritic Ca2+ transients with similar amplitude of ∼200 nm, indicating active backpropagation of action potentials. However, the decay of the dendritic Ca2+ concentration back to baseline values was substantially different with a decay time constant of 550 ms in young versus 130 ms in mature cells, leading to a more efficient temporal summation of Ca2+ signals during theta-frequency stimulation in the young neurons. Comparison of the peak Ca2+ concentration and the decay measured with different Ca2+ indicators (OGB-5N, OGB-1) in the two populations of neurons revealed that the young cells had an ∼3 times smaller endogenous Ca2+-binding ratio (∼75 versus∼220) and an ∼10 times slower Ca2+ extrusion rate (∼170 s−1versus∼1800 s−1). These data suggest that the large dendritic Ca2+ signals due to low buffer capacity and slow extrusion rates in young granule cells may contribute to the activity-dependent growth and plasticity of dendrites and new synaptic connections. This will finally support differentiation and integration of young neurons into the hippocampal network.

Neuronal activity is critically important for the development of neuronal circuits during postnatal development (Katz & Shatz, 1996; Hensch, 2005), and the intracellular Ca2+ concentration was shown to play a major role in the activity-dependent growth and remodelling of neuronal processes (Wong & Ghosh, 2002; Spitzer, 2006). A global increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration may activate nuclear protein kinases and transcription factors like CaM kinase IV (CaMKIV), cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), and the Ca2+-responsive transactivator (CREST), which in turn activate transcription to promote neuronal outgrowth (Aizawa et al. 2004; Konur & Ghosh, 2005). On the other hand, local dendritic Ca2+ signalling might activate CaMKII and interact with RhoGTPases and the cytoskeleton to promote growth cone turning, as well as retraction and stabilization of new dendritic branches (Jin et al. 2005; Konur & Ghosh, 2005). Although the amplitude and precise time course of the Ca2+ signals may be critically important for these processes, not much is known about the regulation of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration in immature neurons.

The hippocampal dentate gyrus is one of the few regions in the mammalian brain where neuronal development continues into adulthood, with most of the dentate gyrus granule cells (GCs) generated postnatally (Lledo et al. 2006). In rodents, it was shown that the synaptic integration and survival of the young GCs is strongly dependent on the experience of the animal during a critical period of about 3 weeks after birth of the neurons (Tashiro et al. 2007). Synaptic integration of the young neurons follows a specific sequence with the formation of GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses starting during the first and second week after cell birth, respectively (Espósito et al. 2005; Ge et al. 2006; Zhao et al. 2006; Bischofberger & Schinder, 2008).

The synaptic activity during these early developmental stages has a major impact on neuronal differentiation, dendritic growth and survival of the young neurons (Tozuka et al. 2005; Ge et al. 2006; Tashiro et al. 2006). During the first 2–3 weeks, GABA appears to be excitatory due to a high intracellular Cl− concentration. Furthermore, the young GCs express a high density of T-type Ca2+-channels supporting the generation of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes and boosting of suprathreshold action potentials (APs) with very small excitatory currents (Ambrogini et al. 2004; Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004; Couillard-Despres et al. 2006). As a consequence, GABAergic excitation leads to Ca2+ influx which appears to be important for neuronal differentiation and dendritic outgrowth of the young neurons (Tozuka et al. 2005; Ge et al. 2006). In addition to GABA, glutamatergic synapses seem to be important as well, because the survival of the young neurons is dependent on the presence of functional postsynaptic glutamate receptors (Tashiro et al. 2006).

Although excitatory synaptic activity and Ca2+ influx are critically important for the development of young GCs, nothing is known about intracellular Ca2+ signalling mechanisms. Here we used confocal Ca2+ imaging to investigate the properties of AP-induced Ca2+ transients in young and mature hippocampal GCs identified by the expression or the absence of the immature neuronal marker polysialated neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM) in rat and mouse hippocampal slices. Both young and mature GCs showed large AP-evoked dendritic Ca2+ signals with similar amplitude. However, Ca2+ signals were substantially prolonged in the young neurons due to differential activity of Ca2+ pumps including plasma membrane and smooth endoplasmatic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases.

Methods

Slice preparation

Transverse 300–400 μm-thick slices were cut from the hippocampus of 18- to 25-day-old Wistar rats or 2- to 3-month-old adult mice (C57BL/6) with a custom-built vibrating microtome (Geiger et al. 2002; Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2007). The animals were anaesthetized with isoflurane added to the inspiration airflow (4–5%; Abbott, Ludwigshafen, Germany) and killed by decapitation, in accordance with national and institutional guidelines. Slices were kept at 35°C for 30 min after slicing and then stored at room temperature in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mm): 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 25 glucose or, in the case of adult animals, in sucrose-based solution containing 87 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 75 sucrose, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2 and 25 glucose (equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2).

Electrophysiology

For electrophysiological experiments, slices were continuously superfused with ACSF. Patch pipettes (4–7 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass tubing with 2.0 mm outer diameter and 0.5 mm wall thickness (Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany). The pipettes were filled with a solution containing 115 mm potassium gluconate, 20 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 2 mm K2ATP, 0.3 mm NaGTP, 2 mm sodium ascorbate, 2–10 mm Na2-phosphocreatine and 10 mm Hepes. The pH was adjusted to 7.3 by adding KOH. Recordings were performed either at room temperature (∼23°C) or, for some experiments shown in Fig. 7, at physiological temperature (∼34°C) as indicated. Voltage signals were measured with an Axopatch 200B or a MultiClamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) in current-clamp mode (I-clamp fast in the case of the Axopatch 200B), filtered at 10 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz using a CED Power1401 interface (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). Data acquisition and analysis were achieved using custom software (FPulse, U. Fröbe, Physiological Institute Freiburg) running under IGOR Pro 5.02 (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA) and C-Stimfit (C.S.-H.). The seal resistance was at least 5 times larger than the input resistance Rin. The neurons chosen in this study had a resting membrane potential between −85 and −70 mV and generated overshooting APs during injection of depolarizing current. The membrane potential was adjusted to ∼–80 mV throughout the experiment by small depolarizing or hyperpolarizing current injection. The input resistance (Rin) was estimated either in current-clamp mode by injection of small current pulses (500 ms) resulting in a hyperpolarization of the membrane potential of about 2–5 mV or in voltage-clamp mode by applying hyperpolarizing voltage pulses (−5 mV, 100 ms) from the holding potential of −80 mV within the first 10 min in whole-cell configuration. To determine the membrane time constant, the membrane potential was also hyperpolarized by 2–5 mV (500–800 ms current pulses) and 100–300 voltage traces were averaged. The decay after the end of the current injection was transformed logarithmically and the transformed traces were analysed by linear regression (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004).

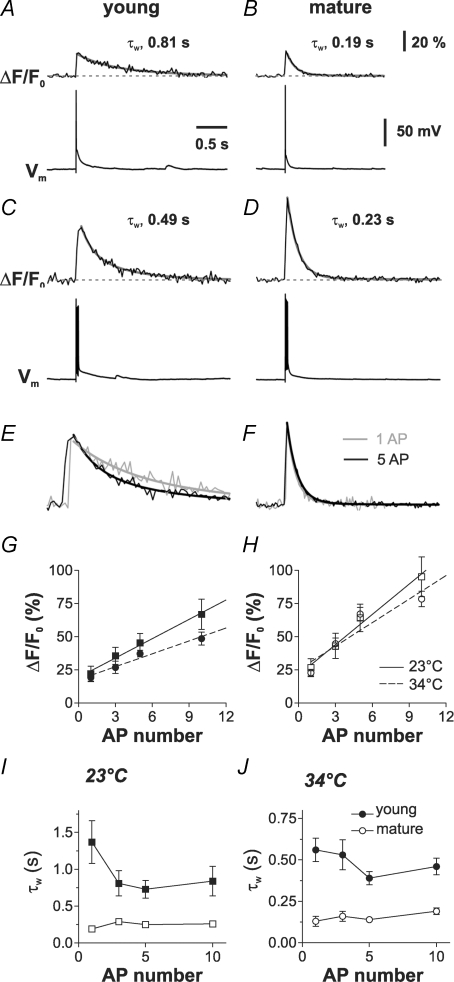

Figure 7. Acceleration of decay kinetics during high-frequency burst firing in young GCs.

A–D, traces show ΔCa2+(t) measured with OGB-5N evoked by single APs (A and B) and a burst of 5 APs at 100 Hz (C and D) in two GCs. E and F, averaged ΔCa2+(t) traces evoked by a single AP (grey) were scaled and superimposed to the traces evoked by the burst of 5 APs (black). In the young GC, the decay kinetics became faster with increased number of APs (E) as shown by the scaled and superimposed traces. G and H, the peak amplitude (ΔF/F0) was plotted against AP number in young (G) and mature GCs (H). Recordings were performed at 23°C (squares) and 34°C (circles) as indicated. Stimulation frequency during the burst was 100 Hz throughout. Data obtained at different temperatures were fitted by linear regression (continuous lines: 23°C; dashed lines: 34°C). I and J, The decay time constant τw in young (filled symbols) and mature cells (open symbols) obtained at 23°C (I) or 34°C (J) was plotted against AP number, showing that Ca2+ signals in young GCs are slower than in mature cells independent of AP number and recording temperature.

Calcium imaging

Dendritic Ca2+ signals were recorded either on proximal dendrites, ∼40–100 μm from the centre of the soma, or, in a subset of experiments, on distal dendrites more than 100 μm from the soma, as indicated. Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB-1, 100 μm), or the low-affinity dye Oregon Green BAPTA-5N (OGB-5N, 500 μm, Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) were added to the intracellular solution (Sabatini et al. 2002). Furthermore, the fluorescent dye Alexa 594 (100–200 μm, Invitrogen) was added to the internal solution to facilitate visualization of thin dendrites and the localization of the regions of interest (ROI). The intracellular solution containing the dye was always kept on ice. Ca2+ measurements were performed with a confocal microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss, Jena, Germany), using a 60× water immersion objective (NA 0.9, LUMPlanFl/IR; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and started at about 40 min after breakthrough to ensure homogeneous distribution of the dyes within the cell. Alternatively, in some experiments (e.g. Fig. 6) a bolus-loading approach was used to minimize washout of diffusible Ca2+ buffers. In these experiments, neurons were first preloaded with OGB-5N/Alexa 594 for 1–1.5 min, then the pipette was slowly withdrawn to obtain an outside-out patch. After about 1 h, the cell was patched again and Ca2+ measurements were started within a few minutes in whole-cell configuration.

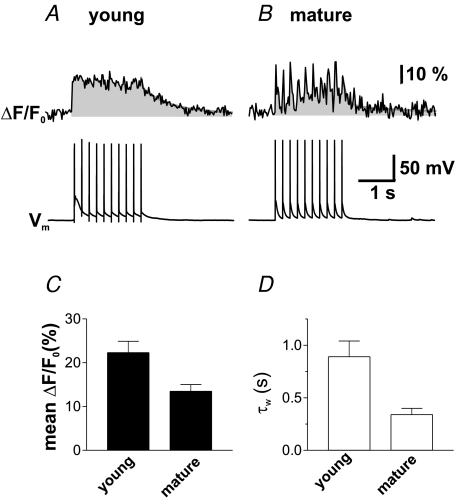

Figure 6. Young GCs show a larger increase in [Ca2+]i during theta-frequency stimulation.

A and B, averaged traces of ΔCa2+(t) during trains of 10 APs repeated at a frequency of 5 Hz in a young (A) and a mature GC (B) measured with OGB-5N. The grey region outlines the area under the curve representing the time integral of the Ca2+ signal. C, bar graphs demonstrate that young GCs (n = 8) showed significantly larger mean amplitude of the Ca2+ signal during theta-frequency stimulation as compared to mature cells (n = 6, P < 0.05). D, similarly, the decay time course after the train was significantly larger in the young GCs (P < 0.05).

OGB-1 and OGB-5N were excited at a wavelength of 488 nm using an argon ion laser. The emitted epifluorescence was measured using a 505 nm long-pass filter and a dichroic mirror with a cut-off wavelength of 570 nm. In order to select dendritic regions of interest, the fluorescence of Alexa 594 was acquired separately using a HeNe laser (543 nm) and a 620–680 nm emission band-pass filter. Increases in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) were induced by back-propagating APs which were evoked by somatic current injections of 5 ms duration. Images of the dendritic regions with a size of 25 × 2 μm or 25 × 12.5 μm were acquired at a rate of 40–200 Hz. All filters and dichroics were from Zeiss.

Calibration of Ca2+ measurements

The affinity of the Ca2+-sensitive dyes was obtained in vitro by measuring the fluorescence (F) of solutions with different Ca2+ concentrations using the equation:

| (1) |

with the minimal fluorescence Fmin, the maximal fluorescence Fmax and the dissociation constant KD (Helmchen, 2005). These values were determined with internal solutions containing 10 mm EGTA (0 Ca2+), 10 mm CaCl2 (max. Ca2+) or a mixture of 7.05 mm CaEGTA and 2.95 mm EGTA (Ca2+-calibration kit, Invitrogen), resulting in a free Ca2+ concentration of 400 nm. Using these solutions, we obtained a KD of 0.201 μm and 25.8 μm for OGB-1 and OGB-5N, respectively. Furthermore, the maximal dynamic range (Rf=Fmax/Fmin) of the two dyes was 9.60 and 33.77, respectively.

The Ca2+-dependent increase in fluorescence was measured in ROIs and expressed as relative change in fluorescence (ΔF/F0), after background subtraction. Furthermore, we estimated the change in intracellular Ca2+ concentration from ΔF/F0 values by converting eqn (1) to:

| (2) |

(Helmchen, 2005). The resting Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]rest) in granule cells (48 ± 4 nm, n = 5) was measured with a CCD camera system using the ratiometric dye Fura-2, as previously described (Normann et al. 2000; Aponte et al. 2008). Therefore, we assumed a similar resting concentration of 50 nm during our confocal Ca2+ measurements using OGB-1 and OGB-5N. The maximal relative increase of the fluorescence (ΔF/F0)max= (Fmax–F0)/F0 was calculated for OGB-1 and OGB-5N as 2.54 and 30.75, respectively, using Rf and KD values obtained from the in vitro calibration.

Single compartment model of dendritic Ca2+ buffering

To analyse the dendritic Ca2+ buffering properties in granule cells, a single-compartment model was used as previously described (Helmchen et al. 1996; Aponte et al. 2008). The fraction of Ca2+ which binds to endogenous Ca2+ buffers (S) during a short AP-evoked Ca2+ influx can be quantified by the Ca2+-binding ratio defined as:

| (3) |

where Δ[SCa] represents the increase in buffer-bound Ca2+ and Δ[Ca2+] the increase in free Ca2+ concentration (Neher & Augustine, 1992). Similarly, the Ca2+-binding ratio of OGB-1 (at a certain concentration B) can be expressed as κB=Δ[BCa]/Δ[Ca2+]. Assuming that the intracellular Ca2+ concentration within a dendritic compartment corresponding to a recorded ROI is homogeneously elevated during an AP from a resting level [Ca2+]1 to the peak level [Ca2+]2, this binding ratio can be calculated as:

| (4) |

with BT and KD representing the total concentration and the Ca2+ dissociation constant of the Ca2+ sensitive dyes, respectively (Neher & Augustine, 1992). By using this relationship, it is possible to estimate the endogenous Ca2+-binding ratio via competition of the endogenous Ca2+ buffers with OGB-1 and OGB-5N. If we assume that the Ca2+ ions (Ca2+tot) entering a dendritic compartment with the volume V rapidly bind to intracellular buffers, they will partially increase the Ca2+-bound fraction of Ca2+ sensitive dyes (Δ[BCa]), and the Ca2+-bound fraction of the endogenous Ca2+ buffers (Δ[SCa]), and will also appear as an increase in free Ca2+ concentration:

This relationship can be expressed as:

| (5) |

with , Therefore, the increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration is linearly related to the Ca2+-binding ratio κB:

| (6) |

As a consequence of eqn (6), the inverse of the peak amplitude A−1= 1/Δ[Ca]i should follow a straight line when plotted against κB:

| (7) |

and cross the x-axis at κB=–(1 +κS) resulting in a direct estimate of the endogenous Ca2+-binding ratio κS (Neher & Augustine, 1992).

As the buffered Ca2+ ions are subsequently released during the decay time course of the transient, increasing κB is also expected to affect the decay time course. If the decay of the Ca2+ concentration back to baseline levels is mediated by a linear extrusion mechanism with the rate γ, the total Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]tot would decrease according to:

| (8) |

According to eqn (6), the left side of eqn (8) can be replaced by:

| (9) |

This differential equation for [Ca2+]i(t) is solved by a simple exponential function with the time constant τ corresponding to:

| (10) |

Thus, τ should also follow a straight line crossing the x-axes at κB=–(1 +κS) when plotted against κB. The analysis of the decay time course therefore results in a second independent estimate of the endogenous Ca2+-binding ratio κS (Helmchen et al. 1996).

When measured with OGB-5N, the decay time course of Ca2+ transients in GC dendrites was dependent on the peak Ca2+ concentration and could not be fitted with a single exponential function similar to what was reported for some other preparations (Kim et al. 2005; Aponte et al. 2008). This indicates that the extrusion rate γ might not be constant, but rather depends on the Ca2+ concentration. Therefore, we used a linear approximation by focusing on the extrusion rate close to resting Ca2+ concentration. We analysed the limiting exponential decay τ0, which was estimated by fitting a straight line to the slow component of the decay time course in a semilogarithmic plot of Ca2+ concentration against time. As the decay was analysed at similar Ca2+ concentrations close to resting values, γ should be constant and the decay time course is only dependent on κB introduced by the indicator dye. Therefore, this analysis reveals a reliable estimate of κS in granule cells.

Morphology and immunohistochemistry

Morphological and immunohistochemical analysis of GCs was performed as previously described (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004). Briefly, cells were filled with biocytin (1 mg ml−1) during whole-cell recording, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and then incubated overnight with 0.3% Triton X-100 and the primary antibody mouse anti-PSA-NCAM (clone 2–2B, monoclonal IgM, Chemicon, 1: 400). A secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 546 goat anti-mouse IgM, 1: 200, Invitrogen) was applied together with FITC-conjugated avidin-D (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 24 h at 4°C. After washing, the slices were embedded in Prolong Antifade (Invitrogen).

Fluorescence labelling was analysed with a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510, Zeiss). Excitation of FITC and Alexa 546 was achieved using an argon (488 nm) and a He–Ne laser (543 nm), respectively. The PSA-NCAM immunofluorescence was measured in 1 μm optical sections using a 40× objective (oil, NA 1.3) and quantified as intensity per pixel near the somatic cell membrane (± 0.5 μm) of the biocytin-labelled cell. Background intensity was subtracted, and the signal was divided by the average fluorescence intensity per pixel within a large region surrounding the filled cell (∼100 000 μm2). As the mean fluorescence intensity represents the average signal generated by the total pool of PSA-NCAM positive and negative cells, the intensity of individual young cells should be above and that of mature cells below the mean value (100%). Previous reports indicate that most of the newly generated neurons are PSA-NCAM positive within 7 days after cell division. The PSA-NCAM expression markedly declines after 3 weeks and is largely absent in 4-week-old cells (Seki, 2002a,b).

The total dendritic length was measured as the sum of the lengths of the dendritic branches in the merged image from 50 to 100 single optical sections. Only cells with intact dendrites were used.

Pharmacology

Stock solutions of thapsigargin, carboxyeosin (CE) and KB-R7943 mesylate (Tocris, Bristol, UK) were prepared in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich), kept below −20°C for a maximum of 4 weeks and diluted to their final concentration shortly before use. The final DMSO concentration was ≤ 0.1%. All drugs were bath-applied after 10–15 min stable baseline. Drug effects were calculated by comparing responses at steady-state about 10 min after application to a control period recorded during 5 min preceding the application. Thapsigargin slightly decreased the peak amplitude of the transients in young and mature cells by ∼20–30%, which might be due to an unspecific effect on voltage-gated Ca2+ channels as reported previously (Markram et al. 1995). Therefore, the Ca2+ transients were scaled to the respective peak amplitude for display purposes.

Data analysis

To estimate the peak values of Ca2+ transients, the amplitudes were extrapolated to the midpoint of the rising phase using the fitted decay time course (Helmchen et al. 1996). In order to analyse the decay kinetics of dendritic Ca2+ transients (ΔCa2+(t)), the averaged fluorescence signals were fitted with either a mono- or a biexponential function. Except for the estimation of endogenous Ca2+-binding ratios, mostly biexponential fits were preferred and an amplitude-weighted time constant (τw) was calculated. Traces shown in the figures represent averages of 4–20 sweeps. All values were expressed as means ±s.e.m. Statistical significance was tested using a Mann–Whitney or Student's paired t test, implemented in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

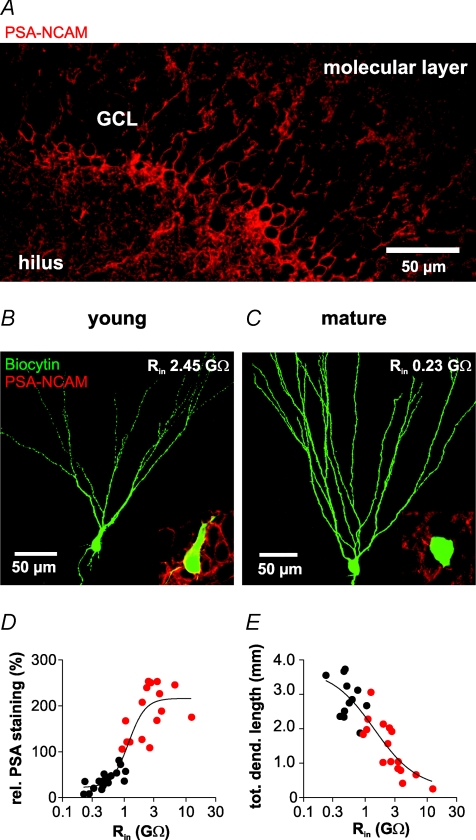

Previously we have shown that young and mature granule cells (GCs) in the adult hippocampus can be identified according to their input resistance (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004). Immature granule cells expressing the polysialated neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM) were shown to have a substantially higher input resistance (Rin≥ 1.5 GΩ) than mature granule cells (Rin≤ 0.4 GΩ; Spruston & Johnston, 1992; Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004, 2007). In order to study the properties of developing GCs during postnatal development, we measured the electrical input resistance and assessed the maturational stage of GCs in juvenile animals by analysing the expression levels of PSA-NCAM (Fig. 1). In 3-week-old animals, PSA-NCAM expression is preferentially localized to the inner part of the granule cell layer, similar to what was reported for the adult dentate gyrus (Fig. 1A; Seki, 2002a; Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004). This is consistent with the notion that although the maturation of newly generated GCs is faster during postnatal development, the anatomical location and functional properties of immature neurons are similar in the postnatal and adult hippocampus (Namba et al. 2005; Overstreet-Wadiche et al. 2006a).

Figure 1. PSA-NCAM-positive hippocampal granule cells show high input resistance and immature dendritic morphology.

A, confocal images showing the immunostaining of PSA-NCAM positive granule cells (A) in the dentate gyrus; note their prevalent localization at the border towards the hilus. B and C, biocytin-filled young (B) and mature (C) granule cell (green; merged images from 100 single optical sections of 1 μm). Insets: superposition of single confocal images of biocytin labelling and PSA-NCAM immunostaining in the same cells. Note the high PSA-NCAM expression in the young cell in B (yellow rim). Inset width: 15 μm (B) and 30 μm (C). D and E, relative PSA-NCAM staining (D) and total dendritic length (E) are plotted against input resistance. The relative PSA-NCAM staining was obtained by normalizing the fluorescence intensities of individual cells to the average fluorescence intensity of the dentate gyrus (see Methods). Cells with expression levels above 100% are represented by red dots. Continuous curves represent Boltzmann functions fitted to the data.

Cells were filled with biocytin during whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, and subsequently stained with FITC-conjugated avidin for morphological identification (Fig. 1B and C). In contrast to the outer part of the GC layer, most cells in the inner part express PSA-NCAM and show a high input resistance. PSA-NCAM negative neurons showed the typical morphology of mature GCs with multiple long apical dendrites, no basal dendrites and a total dendritic length of ∼2000–3800 μm (Rihn & Claiborne, 1990). By contrast, PSA-NCAM-positive GCs often showed multiple short basal dendrites and a short and immature dendritic tree (Lübbers & Frotscher, 1988; Rao & Shetty, 2004). Correlation of the relative immunofluorescence of individual GCs with their input resistance revealed that all cells with an input resistance larger than Rin≥ 1 GΩ were not only positive for PSA-NCAM, but also had a relatively short total dendritic length with a mean value of 1431 ± 195 μm (n = 16; Fig. 1D and E, red dots). On the other hand, cells with an input resistance below 0.4 GΩ consistently showed a large and elaborated dendritic tree and a low PSA-NCAM signal close to background values. Based on these morphological and immunohistochemical data, we classified neurons according to their input resistance as young (Rin≥ 1 GΩ) or mature (Rin≤ 0.4 GΩ) granule cells, respectively.

Different kinetics of dendritic Ca2+ transients in young and mature GCs

To study Ca2+ signalling, we recorded AP-evoked Ca2+ transients in proximal (∼40–100 μm) and distal apical dendrites (∼100–150 μm) of young and mature hippocampal GCs at 23°C using the high-affinity Ca2+-sensitive dye OGB-1 (100 μm; Fig. 2). Brief somatic current injections evoked overshooting APs in young and mature GCs with similar amplitude of 124 ± 3 mV (n = 14) and 132 ± 2 mV (n = 10; P > 0.05), respectively. The half-duration was slightly longer in young cells (2.3 ± 0.2 ms) as compared to mature GCs (1.9 ± 0.1 ms; P > 0.05). These somatic APs evoked large dendritic Ca2+ transients and corresponding fluorescence changes (ΔF/F0) in dendritic regions of interest (ROIs; white rectangles in Fig. 2A and C) in all GCs, consistent with axonal initiation and active backpropagation of APs within the GC dendritic tree (Jefferys, 1979; Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2008).

Figure 2. Long-lasting dendritic Ca2+ transients in young GCs evoked by single APs.

A, confocal image of a young GC. Regions delimited by the white rectangles show the regions of interest (ROIs) where the calcium transients (ΔCa2+(t)) were recorded. B, average of 6 individual Ca2+ transients (ΔF/F0) evoked by single APs (Vm) recorded in the proximal (middle trace) and distal dendritic region (upper trace) indicated in A. C, confocal image of a mature GC. D, average of 7 individual sweeps following a single AP recorded in the proximal and distal ROI indicated in C. The decay time course was fitted with a biexponential function (grey lines) and the amplitude-weighted time constants (τw) were calculated as indicated. The transients were recorded with the high-affinity Ca2+-sensitive dye OGB-1 (100 μm, KD= 0.2 μm).

The amplitude of the Ca2+ transients in young cells was slightly smaller (55.6 ± 7.4%; n = 15) than in mature cells (77.3 ± 5.8%; P < 0.05; n = 21; Fig. 2B and D) for both proximal and distal dendritic compartments (57.7 ± 11.6%; n = 6, versus 77.2 ± 8.3%, n = 6). Comparing the proximal with the distal transients revealed that the amplitude is not significantly different in young or in mature granule cells (P > 0.5). Most importantly, the decay of the Ca2+ concentration back to resting values was remarkably different in young and mature granule cells. When fitted with a biexponential function, the amplitude-weighted time constant τw in proximal dendrites was on average ∼4 times slower in young cells (τw= 4.9 ± 0.5 s, n = 15) than in mature GCs (τw= 1.3 ± 0.1 s, n = 21, P < 0.001). Likewise, in distal dendritic compartments the decay time course was also ∼4 times slower (τw= 5.2 ± 0.8 s versus 1.2 ± 0.1 s in mature GCs, P < 0.01) than in mature cells. The data show that backpropagating APs evoke large dendritic Ca2+ transients in proximal (40–100 μm) and distal dendritic compartments (100–150 μm) in young and mature dentate gyrus GCs. However, the decay time course appears to be substantially slower in young neurons.

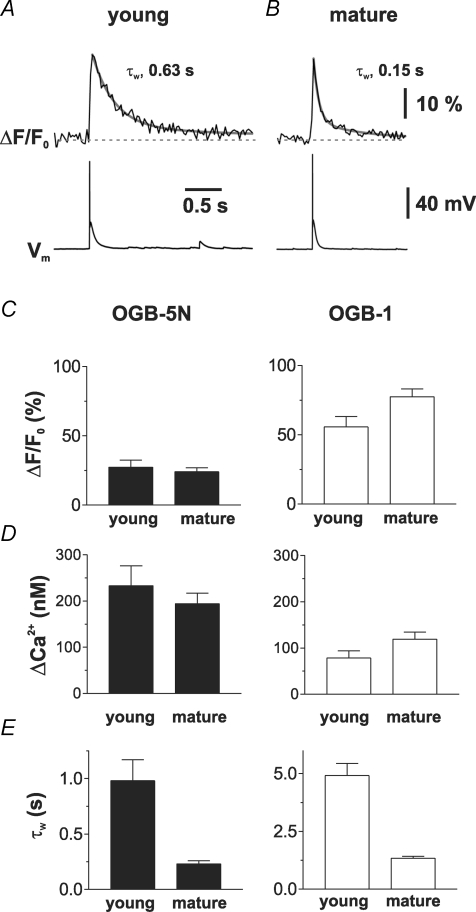

Different Ca2+-binding ratios and extrusion rates in young and mature GCs

Calcium indicators act as exogenous mobile buffers inside the cell and may significantly affect intracellular calcium dynamics depending on their concentration and affinity for Ca2+ (Helmchen et al. 1996). In particular, high-affinity calcium indicators, like OGB-1 (KD= 0.201 μm; see Methods), may prolong the decay of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) back to resting levels. To minimize these effects, we measured AP-evoked Ca2+ transients using the low-affinity dye OGB-5N (500 μm; KD= 25.8 μm, Fig. 3). As expected from the OGB-5N Ca2+-binding properties, the amplitude of the relative fluorescence change ΔF/F0 was smaller in both groups of cells with an amplitude of 27.4 ± 5.0% in young (n = 11) and 24.1 ± 2.9% in mature neurons (Fig. 3A–C; n = 11; P > 0.5). Furthermore, the decay kinetics of the Ca2+ transient (ΔCa2+(t)) was faster than the kinetics measured with OGB-1, regardless of the maturational stage of the GCs. Most importantly, the decay of Ca2+ transients in young GCs was on average about 4 times slower than in mature neurons with τw= 1.00 ± 0.19 s (n = 11) versus 0.23 ± 0.03 s (n = 11; P < 0.001; Fig. 3E). These data show that Ca2+ signalling in young and mature GCs is substantially different, even when Ca2+ buffering is nearly undisturbed by exogenous Ca2+ buffers.

Figure 3. Long-lasting dendritic Ca2+ transients in young GCs measured with a low-affinity Ca2+ indicator.

A and B, dendritic Ca2+ transients recorded in proximal dendrites of a young (A) and a mature GC (B) with the low-affinity dye OGB-5N (500 μm, KD= 25.8 μm). C, summary bar graphs showing the average values of the peak amplitudes of the fluorescence transients (ΔF/F0) in proximal dendrites (∼40–100 μm) evoked by a single AP and recorded with OGB-5N (n = 11 and 11) or OGB-1 (n = 15 and 21) in young and mature cells as indicated. D, summary bar graphs showing the peak amplitudes of the dendritic Ca2+ transients calculated from the ΔF/F0 values shown in (C) using eqn (2). E, summary bar graphs showing the average values of the decay time constant τw obtained in young and mature cells with OGB-5N and with OGB-1. The decay time course was significantly slower in young cells with both dyes (P < 0.001).

The relative fluorescence changes of OGB-5N can be converted into Ca2+ concentrations using eqn (2) (see Methods), resulting in a peak amplitude of 233 ± 43 nm and 194 ± 23 nm in young and mature cells, respectively (Fig. 3D, left). Comparison of the peak Ca2+ concentrations of the Ca2+ transients measured with the two different dyes (Fig. 3D) indicated that 100 μm OGB-1 substantially interferes with the Ca2+ buffering in granule cells. Most importantly, the effect appears to be larger in the young neurons, suggesting that the endogenous Ca2+ buffering properties might be different in young and mature neurons. Therefore we estimated the endogenous Ca2+-binding ratio κS by plotting the inverse amplitudes of the Ca2+ transients against the exogenous binding ratio introduced by 500 μm OGB-5N (κB≈ 19) or 100 μm OGB-1 (κB≈ 250; Fig. 4A and B). Fitting the data with a straight line according to eqn (7) (see Methods) indicates a binding ratio of κS= 98 for young and κS= 303 for mature GCs. Similarly, we estimated κS from fitting the time course of the slow component of the Ca2+ transients with a time constant τ0. The slowing of τ0 by introduction of the large exogenous Ca2+-binding ratio of OGB-1 as compared to OGB-5N indicates an endogenous binding ratio of 51 in young and 142 in mature GCs (Fig. 4C and D; eqn (10)). Thus, the endogenous Ca2+-binding ratio appears to be smaller in the young neurons (κS= 50–100) and increases with maturation to values of about 150–300. Assuming an average binding ratio of 75 and 220 for young and mature cells, the decay time constant of 1.00 s and 0.23 s would correspond to an ∼10 times smaller extrusion rate γ of 95 s−1 in young versus 1044 s−1 in mature GCs (according to eqn (10)).

Figure 4. Smaller Ca2+-binding ratio κS in young than in mature granule cells.

A and B, the inverse amplitudes of the Ca2+ transients recorded with OGB-5N (500 μm; small κB) and OGB-1 (100 μm; large κB) were plotted against the exogenous binding ratio κB introduced by the Ca2+-sensitive dyes and κS was estimated from the x-axis intercept of an extrapolated straight line fitted to the data. According to eqn (7), these data indicate a κS of 98 and 303 for young (n = 26) and mature GCs (n = 32), respectively. C and D, the slow component of the decay time course τ0 of the Ca2+ transients was plotted against κB. κS was estimated from the x-axes intercept of the extrapolated straight line fitted to the data. According to eqn (10), this analysis indicates a κS of 51 and 142 for young (n = 26) and mature GCs (n = 32), respectively.

As the imaging experiments were performed after 40 min of whole-cell recordings the different endogenous buffer capacities of young and mature granule cells might be due to differential washout of diffusible Ca2+-binding proteins (Müller et al. 2005). Therefore, we performed some experiments using a bolus loading approach. Granule cells were filled with OGB-5N for about 1 min. After 1 h the cells were patched for a second time and recordings of AP-evoked dendritic Ca2+ transients were started within a few minutes after whole-cell recording was established. Using the bolus-loading approach, the amplitude of the Ca2+ transients was similar in young (24.0 ± 3.2%, n = 6) and mature GCs (26.1 ± 4.2%, n = 6; P > 0.5) corresponding to a mean amplitude of 203 nm and 221 nm, respectively. These values are not significantly different from the values obtained after 40 min in whole-cell recording (P > 0.5). Furthermore, the decay time course after bolus loading was not significantly different as compared to long whole-cell recordings in young cells (τw= 0.94 ± 0.12 s versusτw= 1.00 ± 0.19 s; P > 0.1) and in mature GCs (τw= 0.20 ± 0.03 versus 0.23 ± 0.03 s; P > 0.1). These data show that diffusible buffers in granule cells do not significantly affect dendritic Ca2+ transients evoked by single backpropagating APs. Thus, the different endogenous Ca2+ buffer capacities in young and mature cells are mainly determined by non-diffusible Ca2+ buffers.

Taken together, these experiments suggest that backpropagating APs generate large dendritic Ca2+ transients in both young and mature hippocampal GCs. Whereas the peak amplitude appears to be similar at different developmental stages (∼200 nm), the data indicate that the endogenous Ca2+ binding is smaller and Ca2+ extrusion is substantially slower in immature neurons.

Low-threshold Ca2+ spikes induce dendritic Ca2+ transients

Newly generated young granule cells generate low-threshold Ca2+ spikes dependent on the amplitude and time course of the excitatory current (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004). These spikes are generated at a threshold of ∼−56 mV by the opening of low-voltage activated T-type Ca2+ channels (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004), which have been suggested to play an important role in the differentiation of developing neurons (Perez-Reyes, 2003; Spitzer, 2006).

Since T-type channels are characterized by a low conductance and transient activation, they may generate a small increase in [Ca2+]i (Perez-Reyes, 2003). Therefore, we used OGB-1 to improve the signal to noise ratio. Small depolarizations of the membrane potential from resting values of −80 mV to values up to −60 mV did not induce measurable changes in dendritic Ca2+ concentration (ΔF/F0= 1.6 ± 0.5%, n = 4; Fig. 5A). However, when current injections (∼6–18 pA, 500 ms) depolarized the membrane to values more positive than ∼−55 mV, a low-threshold spike was evoked, which always generated a large dendritic Ca2+ transient with an average amplitude of ΔF/F0= 49.4 ± 6.0% (n = 5; Fig. 5B and D). The efficient dendritic propagation of low-threshold spikes might be supported by the slow membrane time constant in young cells (102 ± 8 ms; range 84–135 ms; n = 7) as compared to mature GCs (56 ± 2 ms; n = 4; P < 0.01) indicative of a higher specific membrane resistance and a lower density of open ion channels at the resting membrane potential.

Figure 5. Dendritic Ca2+ transients during low-threshold Ca2+ spikes.

A, dendritic Ca2+ concentration measured with OGB-1 (100 μm) in a proximal dendritic ROI of a young GC (see inset) indicated by the white rectangle (∼60 μm distance from soma), during a 500 ms current pulse with an amplitude of 5.5 pA leading to a subthreshold depolarization to ∼−60 mV. The simultaneously recorded membrane potential Vm is shown below at the same time scale (middle trace) or at an expanded scale (lower trace). Resting membrane potential: −80 mV. B and C, traces show ΔCa2+(t) evoked by isolated Ca2+ spikes (B) and overshooting Na+/Ca2+ spikes (C) from the same cell and the same dendritic ROI as shown in A. The simultaneously recorded membrane potential Vm is shown below. D, summary bar graph showing the different average peak amplitudes of ΔCa2+(t) induced by passive depolarization, Ca2+ spikes and Ca2+/Na+ spikes evoked by current injections ranging from 5 to 25 pA in the same GCs (n = 5). E, the decay time constants of Ca2+ transients were not significantly different in the two conditions (P > 0.05).

For comparison, we evoked overshooting action potentials in the same cells with slightly larger stimulation currents (ΔI = 7 pA; Fig. 5C and D). We found that the amplitude of Ca2+ transients evoked by low-threshold Ca2+ spikes (ΔF/F0= 49.4 ± 6.0%) was about half of the amplitude generated by overshooting APs within the same cells (101.8 ± 16.0%, n = 5, P < 0.01; Fig. 5D). By contrast, the decay kinetics in the two cases was comparable, with τ= 3.6 ± 0.6 s and 4.3 ± 1.1 s during Ca2+ spikes and Na+ spikes, respectively (P > 0.05; Fig. 5E). These findings show that small excitatory inputs generating low-threshold Ca2+ spikes are able to induce large and long-lasting increases in dendritic Ca2+ concentration with a time course similar to AP-induced Ca2+ transients.

Young GCs show larger Ca2+ signals during low-frequency stimulation

We have previously shown that young GCs exhibit enhanced synaptic plasticity during theta-frequency stimulation (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004). Since [Ca2+]i plays a pivotal role in the induction of synaptic plasticity, we investigated the characteristics of Ca2+ transients elicited by trains of APs similar to the ones inducing long-term synaptic changes in young GCs (Fig. 6). GCs were filled with the low-affinity dye OGB-5N using the bolus loading approach, and APs were evoked using a theta-frequency stimulation protocol (10 APs at 5 Hz).

In order to quantify the size of the Ca2+ signal induced by this protocol, we calculated the mean amplitude of [Ca2+]i during the stimulation (Fig. 6C). The mean elevation of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration in young cells was 22.2 ± 2.6% above baseline (n = 8) corresponding to an average concentration of ∼240 nm, significantly larger than in mature cells (13.5 ± 1.5%, n = 6, P < 0.05; corresponding to ∼160 nm; Fig. 6C). The Ca2+ transients had similar decay kinetics as transients evoked by single APs with τw= 0.89 ± 0.15 s and 0.34 ± 0.06 s in young and in mature cells, respectively (P < 0.01, Fig. 6D). Therefore, the difference in intracellular Ca2+ regulation finally leads to a larger integral of the Ca2+ signal over time. Taken together, the slower Ca2+ extrusion in young GCs allows efficient temporal summation of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration during repetitive low-frequency firing.

Decay kinetic in young GCs depends on peak Ca2+ concentration

To further characterize AP-induced dendritic Ca2+ signals, we studied the dynamics of Ca2+ transients during high-frequency trains of APs. Ca2+ transients were elicited by 1, 3, 5 and 10 APs generated at a frequency of 100 Hz (Fig. 7). The amplitude of ΔCa2+(t) increased with the number of APs in both young and mature GCs in a linear manner as shown by linear regression analysis (Fig. 7G and H, P < 0.05). However, the slope of this ΔCa2+–AP relationship appears to be smaller in young cells than in mature neurons (5.0 ± 0.5% per AP in young versus 7.9 ± 0.8% per AP in mature cells). Most remarkably, the dynamics of Ca2+ extrusion was very different in the two cell groups (Fig. 7E, F, I and J). Whereas the decay of the Ca2+ transient in mature cells was largely independent of the number of APs, the decay was significantly shorter with increasing number of APs in the young cells with τw= 1.37 ± 0.29 s and 0.73 ± 0.12 s for one and five APs, respectively (n = 5; P < 0.05; Fig. 7I). Nevertheless, the decay kinetics in young cells was consistently slower than in mature cells.

As the activity of Ca2+ pumps is believed to be temperature dependent, we also recorded Ca2+ transients at physiological temperature (Figs 7G, H and J). At 34°C, the peak amplitude of dendritic Ca2+ transients was similar in young and mature cells, comparable to what was found at room temperature (19.3 ± 3.1%, n = 6, and 22.8 ± 2.5%, n = 5, P > 0.3, corresponding to a peak amplitude of 163 nm and 193 nm). However, the decay time course was substantially different in the two cell types with a time constant of 545 ± 84 ms and 130 ± 25 ms (P < 0.01), respectively. Assuming that the endogenous binding ratios in young (κs≈ 75) and mature cells (κs≈ 220) are relatively independent of temperature, these decay time courses would correspond to an average extrusion rate of 174 s−1 and 1846 s−1 at 34°C. Furthermore, the peak amplitude of the undisturbed Ca2+ transients without 500 μm OGB-5N, corresponding to κB= 19, would be 207 nm and 211 nm in young and mature GCs, respectively. Finally, whereas the decay time course was relatively constant in the mature cells, there was a significant acceleration of the decay with increasing number of APs in the young GCs also at physiological temperatures (P < 0.05; Fig. 7J).

These data suggest that young GCs have slower Ca2+-extrusion rates than mature GCs, independent of the AP number and recording temperature. Furthermore, in contrast to mature cells, in young neurons the extrusion rate is accelerated during high-frequency electrical activity. This shows that Ca2+ extrusion mechanisms in mature and immature hippocampal granule cells have substantially different functional properties.

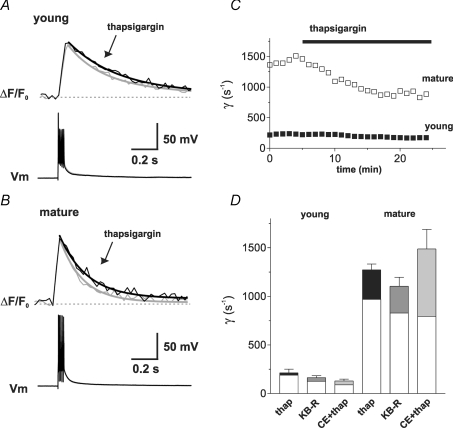

Contribution of different Ca2+ pumps to the decay kinetics of Ca2+ transients

To analyse the mechanisms contributing to Ca2+ extrusion in young and mature granule cells, we used a pharmacological approach and investigated the role of the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) and the plasma-membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) at room temperature (Markram et al. 1995).

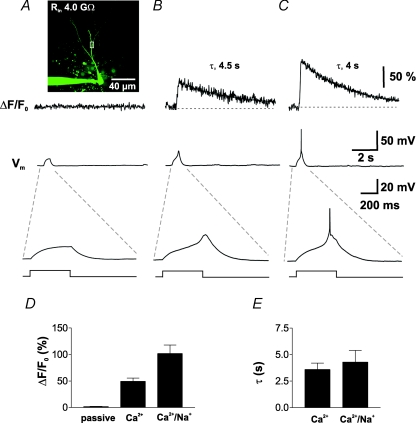

Trains of five APs at 100 Hz were evoked, leading to Ca2+ transients with a decay time constant of τw= 0.54 ± 0.10 s and 0.19 ± 0.01 s in young (n = 6) and mature GCs (n = 4; Fig. 8A and B), corresponding to an extrusion rate of 213 ± 38 s−1 and 1273 ± 60 s−1, respectively. To analyse the effect of the different blockers, we plotted the extrusion rate against time and compared the mean values 5 min before and 10 min after drug application. The SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin (5 μm) slowed the extrusion rate of the Ca2+ transients in young GCs by 24 ± 7 s−1 as compared to control (n = 6, P < 0.05; Fig. 8A and C). By contrast, in mature GCs, we observed a slowing of the extrusion rate by 304 ± 61 s−1 (n = 4, P < 0.05, Fig. 8B and C). These data indicate that Ca2+ uptake into the smooth endoplasmatic reticulum (ER) contributes to the decay of Ca2+ transients in both young and mature GCs. However, the absolute contribution to Ca2+ extrusion is substantially larger in mature cells.

Figure 8. Contribution of different Ca2+-ATPases to the decay of Ca2+ transients.

A and B, superimposed averaged traces in control (grey traces) and in the presence of thapsigargin (5 μm, black traces) in a young (A) and a mature GC (B) evoked by 5 APs at 100 Hz with peak amplitudes scaled to control. C, the extrusion rate constants γ of the transients in the two cells shown in A and B were calculated and plotted against time. D, summary of the rate constants in control and after application of thapsigargin (5 μm), KB-R7943 (10 μm) and thapsigargin plus carboxyeosin (CE, 20–30 μm, grey bars). Transients were measured with OGB-5N.

Furthermore, we studied the contribution of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) to Ca2+ extrusion in granule cells. Application of the NCX blocker KB-R7943 (10 μm; Iwamoto, 2007) significantly slowed the decay of the Ca2+ transients in young and mature neurons by 38 ± 2 s−1 and 275 ± 13 s−1, respectively (P < 0.001 for n = 5 and 5, respectively), showing that the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger also differentially contributes to Ca2+ extrusion in these neurons.

Finally, the contribution of the PMCA was tested by application of carboxyeosin (CE, 20–30 μm). As CE blocks both the PMCA and the SERCA, we applied CE after preceding application of thapsigargin (5 μm), which prolonged the decay of the Ca2+ transient in both young and mature cells relative to control. Subsequent application of CE further reduced the extrusion rate by 20 ± 12 s−1 and 488 ± 97 s−1 in young and mature cells (n = 3 and 4, Fig. 8D). Comparing the reduction of Ca2+ extrusion by thapsigargin, KBR and CE between cell types shows that the effects of the drugs were 13-, 7- and 24-times larger, respectively, in mature cells (P < 0.001). Thus, the data indicate that all the major Ca2+ extrusion systems, i.e. SERCA, NCX and PMCA, are much less active in young as compared to mature granule cells.

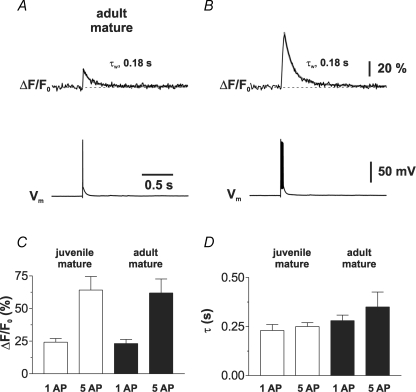

Ca2+ transients in mature and young neurons were studied in the juvenile rat hippocampus. Although the mature GCs are PSA-NCAM negative and show large dendritic trees similar to what was published for adult rats (Rihn & Claiborne, 1990) they might not be fully mature at this age. Therefore, we also recorded Ca2+ transients with OGB-5N in hippocampal slices from 2- to 3-month-old adult mice (Fig. 9, Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2007). Single APs evoked dendritic Ca2+ transients with large amplitude (ΔF/F0= 23.1 ± 3.3% and rapid decay (τw= 0.28 ± 0.03 s; n = 5), similar to what was observed in mature cells from juvenile animals (24.1 ± 2.9%, P > 0.5 and 0.23 ± 0.03 s, P > 0.1). These data indicate that after development of the dendritic tree and down-regulation of PSA-NCAM expression, the mature GCs show rapid Ca2+ signalling largely independent of animal age.

Figure 9. Rapid Ca2+ transients in mature GCs from the adult hippocampus.

A and B, dendritic Ca2+ transients recorded in a proximal dendrite of a mature GC in a hippocampal slice from a 2-month-old adult mouse evoked with 1 (A) or 5 APs (B). Ca2+ transients were measured with the low-affinity dye OGB-5N (500 μm). C, summary bar graphs showing the average values of the peak amplitudes of the fluorescence transients (ΔF/F0) evoked by a single AP and 5 APs. The Ca2+ signals were recorded in proximal dendrites (∼40–100 μm) of mature GCs in juvenile (open bars; n = 11 and 4) and adult hippocampus (filled bars; n = 5 and 5) using OGB-5N. D, summary bar graphs showing that the average decay time constant τw obtained in mature GCs from juvenile and adult hippocampus is not significantly different after 1 AP (P > 0.1) and after 5 APs (P > 0.1). Same cells as in (C).

Taken together, the results suggest that young and mature hippocampal GCs show efficient activation of dendritic Ca2+ channels by single backpropagating APs. Developing GCs apparently generate long lasting Ca2+ transients due to slow Ca2+ extrusion. By contrast, the abundant expression and strong activity of extrusion mechanisms in mature granule cells support rapid Ca2+ signalling within the mature dendritic tree.

Discussion

The present results provide a detailed analysis of dendritic Ca2+ signalling in dentate gyrus granule cells. We characterized intracellular Ca2+ transients induced by backpropagating APs and low-threshold Ca2+ spikes at different developmental stages. Whereas the amplitude of AP-evoked dendritic Ca2+ transients is similar in young and mature cells, the decay kinetics of [Ca2+]i is much slower in young neurons, becoming 3 to 4 times faster with maturation. Furthermore, analysis of Ca2+ transients revealed an ∼3-times smaller Ca2+-buffering capacity and an ∼10 times slower Ca2+ extrusion rate in the young cells. According to our data, this leads to efficient temporal summation of [Ca2+]i transients during repetitive stimulation in young neurons and to rapid Ca2+ signalling in mature hippocampal granule cells.

Active dendritic backpropagation in dentate gyrus granule cells

In dentate gyrus granule cells, not much is known about dendritic excitability, because direct dendritic voltage recordings are difficult. Recently it was shown that APs are initiated in the proximal GC axon and propagate orthodromically along the axon as well as antidromically towards the soma and apical dendrites (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2008). Furthermore, field potential recordings suggest active backpropagation of APs into distal GC dendrites (Jefferys, 1979). Consistent with these previous suggestions, we provide further direct evidence for dendritic propagation of APs in mature and developing hippocampal granule cells at least up to ∼150 μm from the soma.

In neocortical and hippocampal pyramidal cells, APs are also generated near the axon initial segment and actively propagate back into the dendritic tree of these neurons (Häusser et al. 2000). Because of a lower Na+-channel density and the expression of A-type K+ channels, however, the amplitude of the dendritic APs decreases with distance from the soma (Magee et al. 1998). Nevertheless, the depolarization provided by backpropagating APs is large enough in hippocampal pyramidal cells to relieve voltage-dependent Mg2+ block of NMDA receptors and to open voltage-gated Ca2+ channels over a large extent of the dendritic tree (Spruston et al. 1995; Markram et al. 1995; Magee & Johnston, 1997). The resulting Ca2+ transients serve as important associative signals for the induction of synaptic plasticity such as long-term potentiation (LTP) and depression (LTD; Dan & Poo, 2006).

In granule cells, the amplitude of AP-evoked dendritic Ca2+ transients does not significantly decrease with distance from the soma. As the granule cell dendrites are powerful low-pass filters for transient voltage signals (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2007), APs will be heavily attenuated by passive dendritic filtering. Therefore, the large dendritic Ca2+ transients suggest that active conductances support dendritic propagation of APs. Furthermore, the similar results in young and mature neurons show that the dendritic excitability appears, remarkably early during development. Whenever a somatic AP could be evoked in a PSA-NCAM-positive young neuron, a large dendritic Ca2+ transient was observed as well. In support of this view, it was shown that LTP induction in both young and mature granule cells depends on the coincident activation of synaptic NMDA receptors and somatic APs (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004; Ge et al. 2007).

Dendritic Ca2+ signalling in dentate gyrus granule cells

Dendritic Ca2+ transients in granule cells recorded with the low affinity dye OGB-5N had a similar amplitude (∼200 nm) as reported for AP-induced Ca2+ transients in proximal apical dendrites in neocortical and hippocampal pyramidal cells (150–250 nm; Helmchen et al. 1996, 2005). However, whereas the Ca2+-binding ratio of the young GCs is similar to pyramidal cells (∼50–100) the binding ratio of mature GCs appears to be larger and more similar to GABAergic interneurons (∼200–300; Helmchen, 2005; Aponte et al. 2008). The binding ratio of mature GC dendrites is also substantially larger than in the mossy fibre terminals (MFBs) forming output synapses of granule cells onto CA3 pyramidal cells (∼20, Jackson & Redman, 2003). As a consequence, Ca2+ transients in MFBs appear to be larger (∼1 μmversus∼200 nm) and faster than in GC dendrites (τ≈ 40 ms versusτ≈ 130 ms at 34°C; Jackson and Redman, 2003; this study). This suggests that the expression of intracellular Ca2+ buffers in GCs is up-regulated with development and spatially segregated in different subcellular compartments.

It was previously reported that dentate gyrus granule cells express different types of high-voltage activated (HVA) and low-voltage activated Ca2+ channels (LVA, Eliot & Johnston, 1994). Furthermore, local application of Ca2+ or Cd2+ revealed that HVA and LVA Ca2+-channels are expressed at the soma as well as in granule cell dendrites (Blaxter et al. 1989). The precise gating properties of dendritic Ca2+ channels in young and mature GCs are not known. However, our data suggest that these Ca2+ channels are efficiently activated by single backpropagating action potentials throughout the granule cell dendritic tree.

Apparently, the young GCs have slightly smaller AP amplitudes than mature GCs (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004; this study) which might interfere with efficient dendritic propagation. However, this might be counterbalanced by the longer half-duration of the APs. Moreover, the slow membrane time constant in the young cells might further facilitate propagation of dendritic voltage signals, finally leading to efficient activation of dendritic voltage gated Ca2+ channels. As most of the incoming Ca2+ ions bind to endogenous buffers with a binding ratio of 75 and 220 in young and mature GCs, respectively, a Ca2+ influx corresponding to Δ[Ca2+]tot= 15 μm and 44 μm is necessary to generate an amplitude of ∼200 nm in young and mature cells, respectively, during a single AP, indicating that dendritic Ca2+-channel density is substantially up-regulated during granule cell differentiation.

Prolonged Ca2+ signals in developing granule cells

The expression of different Ca2+ extrusion systems including the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases increases during postnatal brain development (Jensen et al. 2004; Kip et al. 2006). Furthermore, the rate of Ca2+ extrusion in human neuroblastoma cells was shown to increase during neuronal differentiation (Usachev et al. 2001). Consistent with these findings, we found that the extrusion of Ca2+ by the plasma membrane and endoplasmatic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases strongly increases in hippocampal granule cells during maturation. Most importantly, we provide the first evidence that the lower extrusion rate in young neurons results in prolonged AP-induced Ca2+ transients (τw≈ 550 ms at 34°C) and efficient temporal summation of dendritic Ca2+ signals.

Whereas single APs induced Ca2+ transients with remarkably slow decay kinetics, the decay was faster after a larger Ca2+ load induced by a brief high-frequency burst of 5–10 action potentials in young cells. By contrast, the decay time constant in mature granule cells was always fast (τw≈ 130 ms at 34°C). Although all major Ca2+ extrusion pathways contribute to Ca2+ regulation in young and mature GCs, the functional differences might arise from the different expression levels of Ca2+ pumps and expression of Ca2+-ATPase subtypes with different Ca2+ affinities (Strehler & Zacharias, 2001; Dode et al. 2002; Periasamy & Kalyanasundaram, 2007).

A major consequence of the slow decay after single APs is the enhanced temporal summation of the Ca2+ concentration during low frequency activity. The mean Ca2+ concentration during theta frequency stimulation is twice as large in young as in mature GCs. This might facilitate the induction of synaptic plasticity in young hippocampal granule cells and thereby support the preferential recruitment of newly generated young neurons during hippocampal memory processing (Bischofberger, 2007; Kee et al. 2007). The rapid extrusion in mature cells, on the other hand, might be important to confine the activation of Ca2+-dependent processes and the induction of synaptic plasticity after maturation, as reported previously (Schmidt-Hieber et al. 2004).

Functional significance of prolonged Ca2+ signals in young granule cells

It has been shown that synaptic excitation of newly generated young granule cells promotes dendritic outgrowth, synapse formation and survival of the young neurons (Tozuka et al. 2005; Ge et al. 2006; Tashiro et al. 2006). However, synaptic currents during early GC development are small (Tozuka et al. 2005; Ge et al. 2006). Our data provide strong evidence that small excitatory currents might be sufficient for the generation of large intracellular Ca2+ transients either via low-threshold Ca2+ spikes or via overshooting APs.

How can Ca2+ ions promote neuronal outgrowth and survival? In newly generated immature olfactory bulb and dentate gyrus GCs it was shown that phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB is important for differentiation and survival of these neurons (Fujioka et al. 2004; Giachino et al. 2005). It is well established that phosphorylation of CREB depends on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration and the activity of CaMKIV (Deisseroth et al. 2003; Konur & Ghosh, 2005). Consistent with its role in cell differentiation, it was reported that the total dendritic length and the number of dendritic branches is strongly reduced in newly generated olfactory bulb granule cells after block of CaM kinases (Giachino et al. 2005). The sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i which occurs for example during theta stimulation might be well suited to support global Ca2+ signals that effectively activate transcription factors like CREB and CREST to promote neuronal development (Konur & Ghosh, 2005). This might finally enable the tight control of dendritic differentiation and synapse formation in newly generated GCs by network activity (Ge et al. 2006; Overstreet-Wadiche et al. 2006b).

In conclusion, young dentate gyrus GCs show large AP-evoked dendritic Ca2+ transients which might be important for the regulation of dendritic growth and synaptic plasticity in an activity-dependent manner to finally support differentiation and integration of young neurons into the hippocampal network.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Jonas, Dieter Chichung Lie and Guilherme Lepski for helpful discussions and thoughtful comments on the manuscript. We also thank S. Becherer and K. Winterhalter for technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Bi 642/2, SFB 505 and SFB 780).

References

- Aizawa H, Hu SC, Bobb K, Balakrishnan K, Ince G, Gurevich I, Cowan M, Ghosh A. Dendrite development regulated by CREST, a calcium-regulated transcriptional activator. Science. 2004;303:197–202. doi: 10.1126/science.1089845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrogini P, Lattanzi D, Ciuffoli S, Agostini D, Bertini L, Stocchi V, Santi S, Cuppini R. Morpho-functional characterization of neuronal cells at different stages of maturation in granule cell layer of adult rat dentate gyrus. Brain Res. 2004;1017:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte Y, Bischofberger J, Jonas P. Efficient Ca2+ buffering in fast spiking basket cells of rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2008;586:2061–2075. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofberger J. Young and excitable: New neurons in memory networks. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:273–275. doi: 10.1038/nn0307-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofberger J, Schinder A. Maturation and functional integration of new granule cells into the adult hippocampus. In: Gage FH, Song H, Kempermann G, editors. Adult Neurogenesis. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2008. pp. 299–319. Chap. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter TJ, Carlen PL, Niesen C. Pharmacological and anatomical separation of calcium currents in rat dentate granule neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 1989;412:93–112. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillard-Despres S, Winner B, Karl C, Lindemann G, Schmid P, Munding M, Aigner R, Wachs F, Laemke J, Kunz-Schughart L, Bogdahn U, Winkler J, Bischofberger J, Aigner L. Targeted transgene expression in neuronal precursors: watching young neurons in the old brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1535–1545. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan Y, Poo MM. Spike timing-dependent plasticity: from synapse to perception. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1033–1048. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deisseroth K, Mermelstein PG, Xia H, Tsien RW. Signaling from synapse to nucleus: the logic behind the mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:354–365. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dode L, Vilsen B, Van Baelen K, Wuytack F, Clausen JD, Andersen JP. Dissection of the functional differences between sarco(endo)plasmatic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) 1 and 3 isoforms by steady-state and transient kinetic analysis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45579–45591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot LS, Johnston D. Multiple components of calcium current in acutely dissociated dentate gyrus granule neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:762–777. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espósito MS, Piatti VC, Laplagne DA, Morgenstern NA, Ferrari CC, Pitossi FJ, Schinder AF. Neuronal differentiation in the adult hippocampus recapitulates embryonic development. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10074–10086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3114-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka T, Fujioka A, Duman RS. Activation of cAMP signaling facilitates the morphological maturation of newborn neurons in adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2004;24:319–328. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1065.03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Goh EL, Sailor KA, Kitabatake Y, Ming G, Song H. GABA regulates synaptic integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Nature. 2006;439:589–593. doi: 10.1038/nature04404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Yang CH, Hsu KS, Ming GL, Song H. A critical period for enhanced synaptic plasticity in newly generated neurons of the adult brain. Neuron. 2007;54:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger JRP, Bischofberger J, Vida I, Fröbe U, Pfitzinger S, Weber HJ, Haverkampf K, Jonas P. Patch-clamp recording in brain slices with improved slicer technology. Pflugers Arch. 2002;443:491–501. doi: 10.1007/s00424-001-0735-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachino C, De Marchis S, Giampietro C, Parlato R, Perroteau I, Schutz G, Fasolo A, Peretto P. cAMP response element-binding protein regulates differentiation and survival of newborn neurons in the olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10105–10118. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3512-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häusser M, Spruston N, Stuart GJ. Diversity and dynamics of dendritic signaling. Science. 2000;290:739–744. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F. Calibration of fluorescent calcium indicators. In: Yuste R, Konnerth A, editors. Imaging in Neuroscience and Development. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2005. pp. 253–263. Chap 31. [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F, Imoto K, Sakmann B. Ca2+ buffering and action potential-evoked Ca2+ signaling in dendrites of pyramidal neurons. Biophys J. 1996;70:1069–1081. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79653-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:877–888. doi: 10.1038/nrn1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto T. Na+/Ca2+ exchange as a drug target – insights from molecular pharmacology and genetic engineering. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1099:516–528. doi: 10.1196/annals.1387.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MB, Redman SJ. Calcium dynamics, buffering, and buffer saturation in the boutons of dentate granule-cell axons in the hilus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1612–1621. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01612.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferys JG. Initiation and spread of action potentials in granule cells maintained in vitro in slices of guinea-pig hippocampus. J Physiol. 1979;289:375–388. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TP, Buckby LE, Empson RM. Expression of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase family members and associated synaptic proteins in acute and cultured organotypic hippocampal slices from rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;152:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M, Guan CB, Jiang YA, Chen G, Zhao CT, Cui K, Song YQ, Wu CP, Poo MM, Yuan XB. Ca2+-dependent regulation of rho GTPases triggers turning of nerve growth cones. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2338–2347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4889-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee N, Teixeira CM, Wang AH, Frankland PW. Preferential recruitment of adult generated granule cells into spatial memory networks in the dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:355–362. doi: 10.1038/nn1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Korogod N, Schneggenburger R, Ho W, Lee S. Interplay between Na+/Ca2+ exchangers and mitochondria in Ca2+ clearance at the calyx of Held. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6057–6065. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0454-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kip SN, Gray NW, Burette A, Canbay A, Weinberg RJ, Strehler EE. Changes in the expression of plasma membrane calcium extrusion systems during the maturation of hippocampal neurons. Hippocampus. 2006;16:20–34. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konur S, Ghosh A. Calcium signaling and the control of dendritic development. Neuron. 2005;46:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lledo PM, Alonso M, Grubb MS. Adult neurogenesis and functional plasticity in neuronal circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:179–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lübbers K, Frotscher M. Differentiation of granule cells in relation to GABAergic neurons in the rat fascia dentata. Combined Golgi/EM and immunocytochemical studies. Anat Embryol. 1988;178:119–127. doi: 10.1007/BF02463645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee J, Hoffman D, Colbert C, Johnston D. Electrical and calcium signaling in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:327–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Johnston D. A synaptically controlled, associative signal for Hebbian plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Science. 1997;275:209–213. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Helm PJ, Sakmann B. Dendritic calcium transients evoked by single back-propagating action potentials in rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 1995;485:1–20. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller A, Kukley M, Stausberg P, Beck H, Müller W, Dietrich D. Endogenous Ca2+ buffer concentration and Ca2+ microdomains in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:558–565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3799-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba T, Mochizuki H, Onodera M, Mizuno Y, Namiki H, Seki T. The fate of neural progenitor cells expressing astrocytic and radial glial markers in the postnatal rat dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1928–1941. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E, Augustine GJ. Calcium gradients and buffers in bovine chromaffin cells. J Physiol. 1992;450:273–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normann C, Peckys D, Schulze CH, Walden J, Jonas P, Bischofberger J. Associative long-term depression in the hippocampus is dependent on postsynaptic N-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8290–8297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08290.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet-Wadiche LS, Bensen AL, Westbrook GL. Delayed development of adult-generated granule cells in dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2006a;26:2326–2334. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4111-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet-Wadiche LS, Bromberg DA, Bensen AL, Westbrook GL. Seizures accelerate functional integration of adult-generated granule cells. J Neurosci. 2006b;26:4095–4103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5508-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated T-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:117–161. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy M, Kalyanasundaram A. SERCA pump isoforms: their role in calcium transport and disease. Muscle Nerve. 2007;35:430–442. doi: 10.1002/mus.20745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MS, Shetty AK. Efficacy of doublecortin as a marker to analyse the absolute number and dendritic growth of newly generated neurons in the adult dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:234–246. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2003.03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rihn LL, Claiborne BJ. Dendritic growth and regression in rat dentate granule cells during late postnatal development. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;54:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini BL, Oertner TG, Svoboda K. The life cycle of Ca2+ ions in dendritic spines. Neuron. 2002;33:439–452. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00573-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Hieber C, Jonas P, Bischofberger J. Enhanced synaptic plasticity in newly generated granule cells of the adult hippocampus. Nature. 2004;429:184–187. doi: 10.1038/nature02553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Hieber C, Jonas P, Bischofberger J. Subthreshold dendritic signal processing and coincidence detection in dentate gyrus granule cells. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8430–8441. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1787-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Hieber C, Jonas P, Bischofberger J. Action potential initiation and propagation in hippocampal mossy fibre axons. J Physiol. 2008;586:1849–1857. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.150151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T. Hippocampal adult neurogenesis occurs in a microenvironment provided by PSA-NCAM-expressing immature neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2002a;69:772–783. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T. Expression patterns of immature neuronal markers PSA-NCAM, CRMP-4 and NeuroD in the hippocampus of young adult and aged rodents. J Neurosci Res. 2002b;70:327–334. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer NC. Electrical activity in early neuronal development. Nature. 2006;444:707–712. doi: 10.1038/nature05300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruston N, Johnston D. Perforated patch-clamp analysis of the passive membrane properties of three classes of hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1992;67:508–529. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.67.3.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruston N, Schiller Y, Stuart G, Sakmann B. Activity-dependent action potential invasion and calcium influx into hippocampal CA1 dendrites. Science. 1995;268:297–300. doi: 10.1126/science.7716524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehler EE, Zacharias DA. Role of alternative splicing in generating isoform diversity among plasma membrane calcium pumps. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:21–50. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Makino H, Gage FH. Experience-specific functional modification of the dentate gyrus through adult neurogenesis: a critical period during an immature stage. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3252–3259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4941-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Sandler VM, Toni N, Zhao C, Gage FH. NMDA-receptor-mediated, cell-specific integration of new neurons in adult dentate gyrus. Nature. 2006;442:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature05028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozuka Y, Fukuda S, Namba T, Seki T, Hisatsune T. GABAergic excitation promotes neuronal differentiation in adult hippocampal progenitor cells. Neuron. 2005;47:803–815. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usachev YM, Toutenhoofd SL, Goellner GM, Strehler EE, Thayer SA. Differentiation induces up-regulation of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase and concomitant increase in Ca2+ efflux in human neuroblastoma cell line IMR-32. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1756–1765. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong RO, Ghosh A. Activity-dependent regulation of dendritic growth and patterning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:803–812. doi: 10.1038/nrn941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Teng EM, Summers RG, Ming G, Gage FH. Distinct morphological stages of dentate granule neuron maturation in the adult mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3648-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]