Abstract

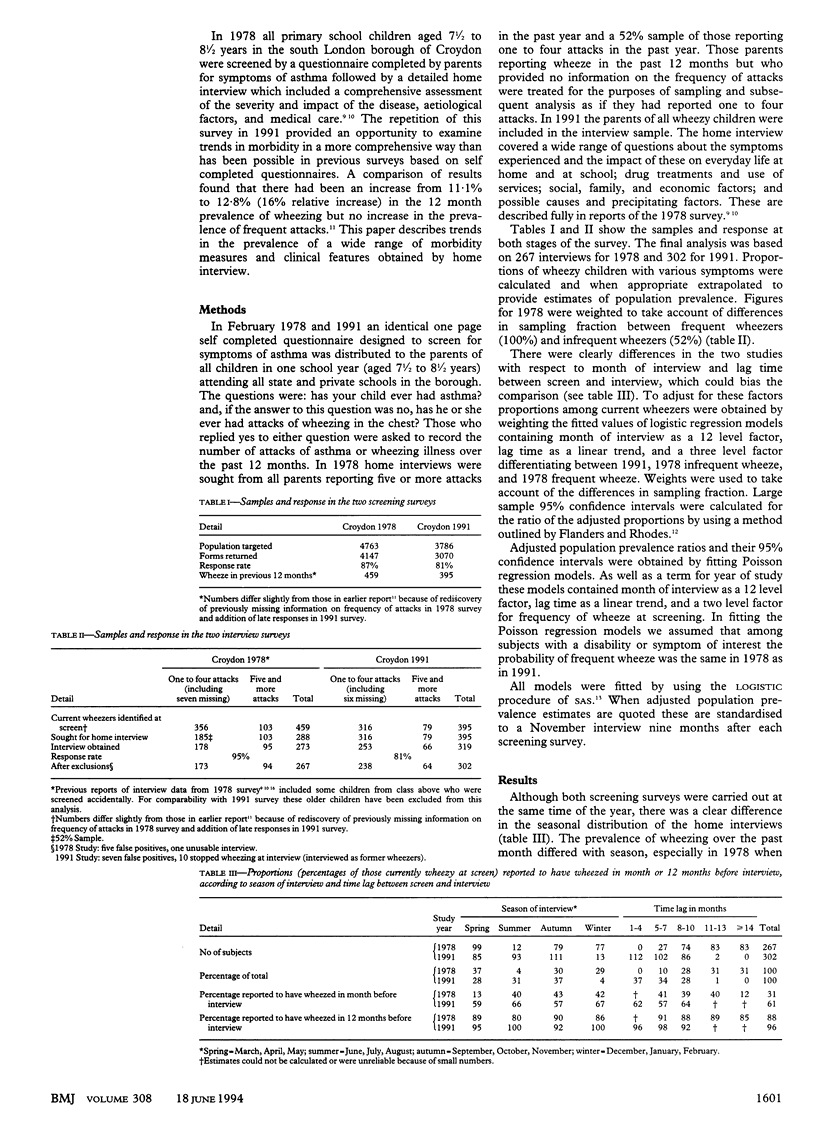

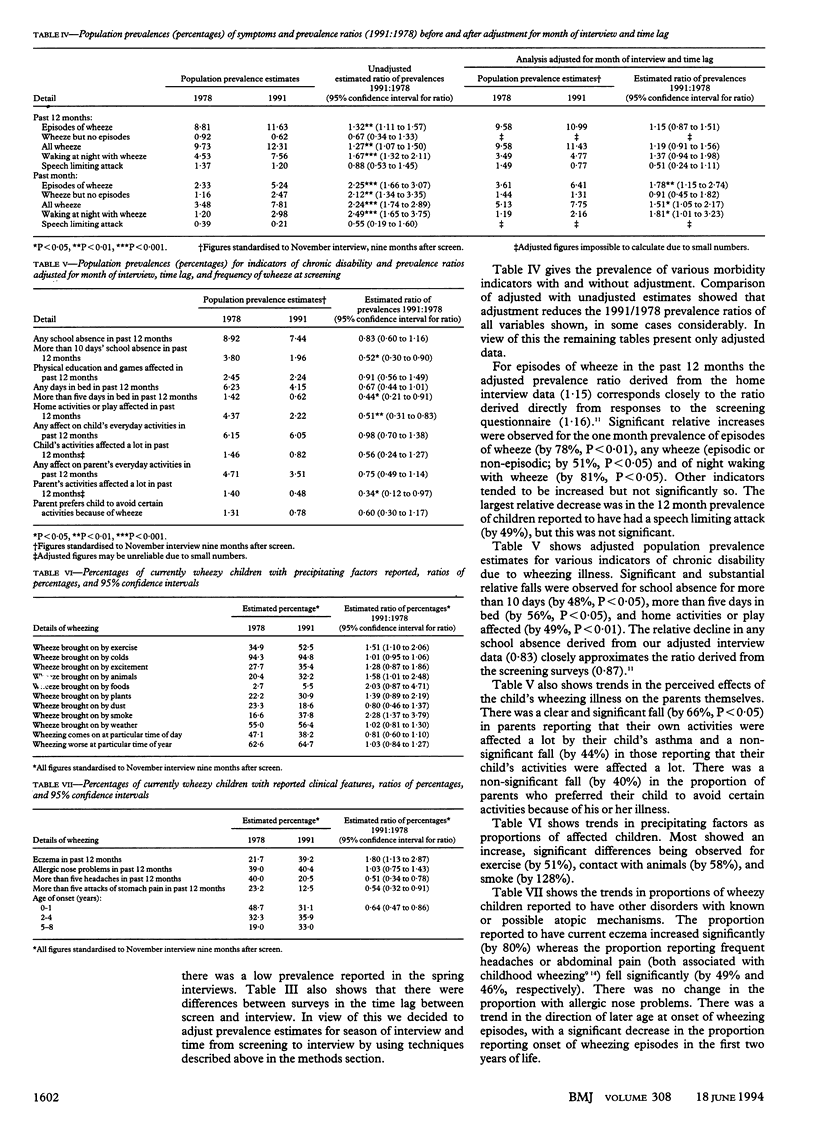

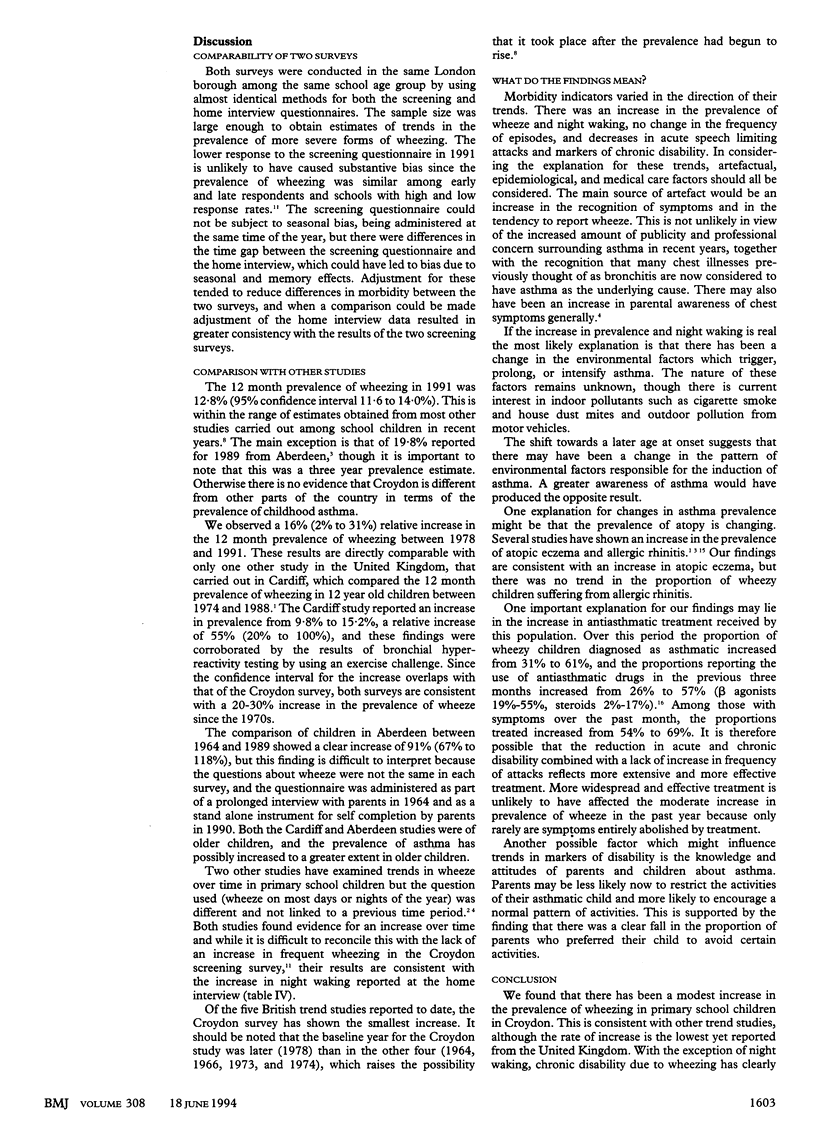

OBJECTIVE--To test the null hypothesis that there has been no change in the prevalence or severity of childhood asthma over recent years. DESIGN--Repeated population prevalence survey with questionnaires completed by parents followed by home interviews with parents. SETTING--London borough of Croydon, 1978 and 1991. SUBJECTS--All children in one year of state and private primary schools aged 7 1/2 to 8 1/2 years at screening survey. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Trends in symptoms, acute severe attacks, and chronic disability. RESULTS--For 1978 and 1991 respectively, the response rates were 4147/4763 and 3070/3786, and home interviews were obtained from 273/288 and 319/395 parents of currently wheezy children. Between 1978 and 1991 there were significant relative increases in prevalence ratios in the 12 month prevalence of attacks of wheezing or asthma (1.16; 95% confidence interval 1.02 to 1.31), the one month prevalence of wheezing episodes (1.78; 1.15 to 2.74), and the one month prevalence of night waking (1.81; 1.01 to 3.23) but not in frequent (> or = 5) attacks over the past year (1.05; 0.79 to 1.40). There were substantial and significant decreases in the 12 month prevalence of absence from school of more than 10 days due to wheezing (0.52; 0.30 to 0.90), any days in bed (0.67; 0.44 to 1.01), and restriction of activities at home (0.51; 0.31 to 0.83) and an equivalent but not significant fall in speech limiting attacks (0.51; 0.24 to 1.11). CONCLUSION--The small increase in the prevalence of wheezy children and relatively greater increase in persistent wheezing suggests a change in the environmental determinants of asthma. In contrast and paradoxically the frequency of wheezing attacks remains unchanged and there are indications that severe attacks and chronic disability have fallen by about half; this may be due to an improvement in treatment received by wheezy children.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson H. R., Bailey P. A., Cooper J. S., Palmer J. C., West S. Medical care of asthma and wheezing illness in children: a community survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1983 Sep;37(3):180–186. doi: 10.1136/jech.37.3.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson H. R., Bailey P. A., Cooper J. S., Palmer J. C., West S. Morbidity and school absence caused by asthma and wheezing illness. Arch Dis Child. 1983 Oct;58(10):777–784. doi: 10.1136/adc.58.10.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson H. R., Bland J. M., Patel S., Peckham C. The natural history of asthma in childhood. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1986 Jun;40(2):121–129. doi: 10.1136/jech.40.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson H. R. Increase in hospital admissions for childhood asthma: trends in referral, severity, and readmissions from 1970 to 1985 in a health region of the United Kingdom. Thorax. 1989 Aug;44(8):614–619. doi: 10.1136/thx.44.8.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres J. G., Noah N. D., Fleming D. M. Incidence of episodes of acute asthma and acute bronchitis in general practice 1976-87. Br J Gen Pract. 1993 Sep;43(374):361–364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burney P. G., Chinn S., Rona R. J. Has the prevalence of asthma increased in children? Evidence from the national study of health and growth 1973-86. BMJ. 1990 May 19;300(6735):1306–1310. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6735.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr M. L., Butland B. K., King S., Vaughan-Williams E. Changes in asthma prevalence: two surveys 15 years apart. Arch Dis Child. 1989 Oct;64(10):1452–1456. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.10.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanders W. D., Rhodes P. H. Large sample confidence intervals for regression standardized risks, risk ratios, and risk differences. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(7):697–704. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming D. M., Crombie D. L. Prevalence of asthma and hay fever in England and Wales. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Jan 31;294(6567):279–283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6567.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninan T. K., Russell G. Respiratory symptoms and atopy in Aberdeen schoolchildren: evidence from two surveys 25 years apart. BMJ. 1992 Apr 4;304(6831):873–875. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6831.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninan T. K., Russell G. Respiratory symptoms and atopy in Aberdeen schoolchildren: evidence from two surveys 25 years apart. BMJ. 1992 Apr 4;304(6831):873–875. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6831.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B., Wadsworth J., Wadsworth M., Peckham C. Changes in the reported prevalence of childhood eczema since the 1939-45 war. Lancet. 1984 Dec 1;2(8414):1255–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92805-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whincup P. H., Cook D. G., Strachan D. P., Papacosta O. Time trends in respiratory symptoms in childhood over a 24 year period. Arch Dis Child. 1993 Jun;68(6):729–734. doi: 10.1136/adc.68.6.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]