Abstract

Dominant mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) are the most frequent molecular lesions so far found in Parkinson's disease (PD), an age-dependent neurodegenerative disorder affecting dopaminergic (DA) neuron. The molecular mechanisms by which mutations in LRRK2 cause DA degeneration in PD are not understood. Here, we show that both human LRRK2 and the Drosophila orthologue of LRRK2 phosphorylate eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)-binding protein (4E-BP), a negative regulator of eIF4E-mediated protein translation and a key mediator of various stress responses. Although modulation of the eIF4E/4E-BP pathway by LRRK2 stimulates eIF4E-mediated protein translation both in vivo and in vitro, it attenuates resistance to oxidative stress and survival of DA neuron in Drosophila. Our results suggest that chronic inactivation of 4E-BP by LRRK2 with pathogenic mutations deregulates protein translation, eventually resulting in age-dependent loss of DA neurons.

Keywords: 4E-BP, dopaminergic neurodegeneration, LRRK2, Parkinson's disease, protein translation

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disease that affects the maintenance of dopaminergic (DA) neurons. PD prevalence is estimated at ∼1% among people over the age of 65 years and is increased to 5% for people aged 85 years and older. Most PD cases are sporadic, with oxidative stress being one prominent pathological feature (Jenner, 2003). A small percentage of PD cases are inherited in a Mendelian manner, and several disease-causing genes have been identified (Moore et al, 2005). Although most of the familial cases are of early onset, mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) cause an autosomal-dominant form of familial PD late in life (Paisan-Ruiz et al, 2004; Zimprich et al, 2004). LRRK2 encodes a large protein with multiple domains, including GTPase and kinase domains. LRRK2-associated familial PD is largely indistinguishable from the more common sporadic PD in clinical and pathological aspects. Among the known familial PD genes, LRRK2 is most frequently mutated in sporadic cases, suggesting a general involvement of LRRK2 in PD pathogenesis (Taylor et al, 2006). So far, amino-acid substitutions associated with familial PD have been identified within the multiple domains (Mata et al, 2006). Some pathogenic mutations in the kinase domain, such as G2019S and I2020T, were shown to cause moderately enhanced kinase activity in vitro (West et al, 2005; Gloeckner et al, 2006). It is not clear whether mutations in other domains (e.g., R1441G and Y1699C) also affect kinase activity. The pathogenic function of LRRK2 mutations and the biochemical pathways involved are unknown. Key to addressing these important questions is the identification of the physiological substrate(s) of LRRK2.

Translational control is critical for early development of most metazoans and for cell survival under various stress (Holcik and Sonenberg, 2005). It allows an organism to quickly respond to physiological or environmental cues by controlling the expression of proteins from existing mRNAs. Although translation can be regulated at multiple steps, control of translation initiation represents a primary regulatory mechanism. The eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) subunit mediates the binding of eIF4F to the 5′ m7GpppX cap structure of mRNAs (Sonenberg et al, 1979; Gingras et al, 1999b). The activity of eIF4E is inhibited by eIF4E-binding protein (4E-BP), which sequesters eIF4E from the eIF4F complex (Gingras et al, 1999b; Richter and Sonenberg, 2005). In vivo, 4E-BP has an important function for survival under starvation stress, oxidative stress and unfolded protein stress, suggesting that control of translation initiation is closely linked to stress and lifespan (Teleman et al, 2005; Tettweiler et al, 2005; Yamaguchi et al, 2008). 4E-BP is regulated by phosphorylation. One pathway known to influence 4E-BP phosphorylation is the target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway, which integrates nutrient availability, growth factors and cellular energy status to control cell growth. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP causes its release from the eIF4E and relieves its inhibitory effect on translation (Gingras et al, 2001; Inoki et al, 2005). At least six phosphorylation sites have been identified in human 4E-BP1 (h4E-BP1), including T37, T46, S65, T70, S83 and S112 (Fadden et al, 1997; Heesom et al, 1998). A sequential phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 in the order of T37/T46>T70>S65 has been proposed (Gingras et al, 1999a, 2001). Although the regulatory mechanisms involved in 4E-BP phosphorylation are not fully understood, it appears that a combination of perhaps all phosphorylation events is required to dissociate 4E-BP from eIF4E (Gingras et al, 2001).

Here, we show that LRRK2 exerts an effect as a regulator of protein translation by phosphorylating 4E-BP at the T37/T46 sites in vitro and in vivo. These phosphorylation events appear to be functionally important for the in vivo pathogenic effects of the mutant Drosophila orthologue of LRRK2 (dLRRK) on stress sensitivity and DA neuron survival. Our results suggest a novel molecular mechanism linking deregulated protein translation to stress sensitivity and neurodegeneration in PD.

Results

dLRRK regulates DA neuron function and maintenance

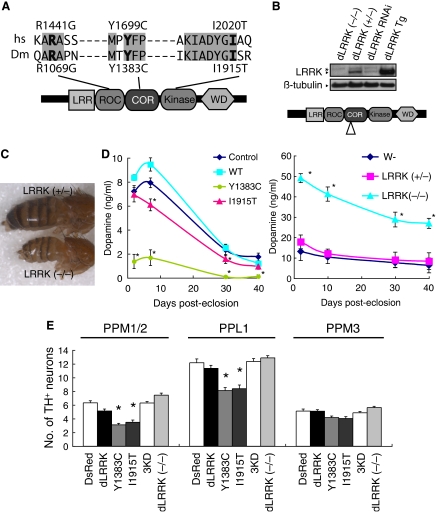

To understand the biological function and pathogenic function of human LRRK2 (hLRRK2), we have used Drosophila as a model system. Drosophila, which possesses a dopaminergic system regulating locomotor behaviour and has a short lifespan, is particularly suitable for modelling the late-onset PD caused by LRRK2 mutations. A single orthologue of LRRK2 (referred to as dLRRK hereafter) was identified in the Drosophila genome. We cloned full-length dLRRK cDNA by RT–PCR. It encodes a 2445 amino-acid protein containing the various domains found in hLRRK2. Critical residues disrupted in familial PD are conserved between hLRRK2 and dLRRK (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

dLRRK regulates function and maintenance of DA neuron. (A) A schematic of dLRRK and hLRRK2 domain structures. (B) Western blot analysis showing loss of dLRRK protein expression in dLRRK(−/−). Brain tissues of 3-day-old adult flies were analysed using anti-dLRRK antibody, which recognizes the N-terminal part of dLRRK. Diagram indicates the location of P-element insertion. (C) A phenotype of malformed abdomen observed with incomplete penetrance in dLRRK(−/−) females. dLRRK(+/−) female shows a normal phenotype. (D) Fly heads of dLRRK Tg driven by Ddc-Gal4 (left) or dLRRK mutant animals (right) were used to prepare tissue extracts for dopamine measurement. Ddc-Gal4/+ and w− serves as controls for Tg and dLRRK mutant, respectively. The values represent means±s.e. from five male fly heads in three independent measurements (Asterisk in left and right panels, P<0.01 and P<0.001, respectively). (E) Quantification of TH+ DA neuron number in the PPM 1 and 2, PPL1 and PPM3 clusters in 60-day-old males of the indicated Tg animals driven by TH-Gal4. PPM1 and PPM2 cluster neurons were counted together. Data were shown as means±s.d. (*P<0.01 versus TH-Gal4>DsRed control, n=12 for dLRRK(−/−); n=10 for the others).

To study the biological function of dLRRK, we analysed its gain-of-function (GOF) and loss-of-function (LOF) effects. For GOF analysis, we generated transgenic (Tg) flies expressing wild-type (WT) dLRRK or mutant dLRRK carrying point mutations found in human PD patients (Figure 1B and Supplementary Figure 1). The DA neuron-specific tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)- and dopa decarboxylase (Ddc)-Gal4 drivers, pan-neuronal elav-Gal4 driver or the ubiquitous daughterless (Da)-Gal4 driver were used to direct transgene expression. For LOF analysis, we obtained one P-element insertion line, in which the expression of full-length dLRRK protein is disrupted, as indicated by the lack of detectable full-length dLRRK protein expression (Figure 1B). In addition, there was no detectable expression of a truncated dLRRK (data not shown). By RT–PCR analysis, we determined that the expression levels of the two genes immediately flanking dLRRK were not affected in this dLRRK (−/−) mutant (Supplementary Figure 2). Mutant animals are viable, but have decreased fertility in females. In addition, malformed abdomen is often observed in females (Figure 1C), especially when nutritional status is compromised at the larval stage. Because mutants with this phenotype show higher sensitivity to various stress and have shortened lifespan, we excluded them in subsequent analyses.

To test whether dLRRK regulates the function and maintenance of DA neurons, we performed immunohistochemical and neurochemical analyses in Drosophila. Immunohistochemical analysis using an anti-dLRRK antibody showed that endogenous dLRRK protein expression is fairly ubiquitous in the fly brain (Supplementary Figure 1B and C). Double labelling with TH showed that it is expressed in DA neurons (Supplementary Figure 1M and N). In Tg animals, we estimated that exogenous WT and mutant dLRRK were expressed at 1.5- to 2.6-fold of endogenous level in TH+ neurons (Supplementary Figure 1M). At the cellular level, endogenous dLRRK was localized in a punctate pattern in the cytoplasmic part of the cell bodies and neurites (Supplementary Figure 1L). Transgenic WT and mutant dLRRK proteins derived from the transgenes were also localized to vesicular structures that co-stain with endosomal markers and partially overlap with synaptic vesicle markers (Supplementary Figure 1H–K and O–V).

In Tg flies expressing PD-related mutant dLRRK, brain dopamine content was significantly reduced compared with dLRRK WT Tg or control flies (Figure 1D, left). Conversely, dopamine content was elevated in dLRRK (−/−) flies, suggesting that dLRRK negatively regulates steady-state dopamine levels (Figure 1D, right). We tested whether this difference in DA content might reflect differential maintenance of DA neurons. In young flies (10-day-old), no difference in DA neuron number was observed when compared with a normal control (Supplementary Figure 3). In aged flies (60-day-old), however, animals expressing pathogenic dLRRK showed a significant reduction of DA neurons in the protocerebral posterior lateral (PPL) 1 and protocerebral posterior medial (PPM) 1 and 2 clusters (Figure 1E). Expression of a kinase-dead form (3KD) of dLRRK or WT dLRRK had no significant effect on DA neuron number (Figure 1E). In both young and aged dLRRK (−/−) flies, DA neurons appeared healthy and well maintained (Figure 1E and Supplementary Figure 3). The increase of brain dopamine level in dLRRK (−/−) flies is thus likely due to changes of dopamine transmission, storage or metabolism, but not to a change of TH+ neuron number.

Transgenic animals were morphologically normal when dLRRK was ubiquitously expressed. No gross brain degeneration other than DA neuron loss was observed when dLRRK was pan-neuronally expressed, and no neurodegeneration was observed when dLRRK was expressed in specific neuronal types (Supplementary Figure 4 and data not shown), indicating that the toxicity of mutant dLRRK is relatively specific to DA neurons.

Altered dLRRK expression affects organismal sensitivity to oxidative stress

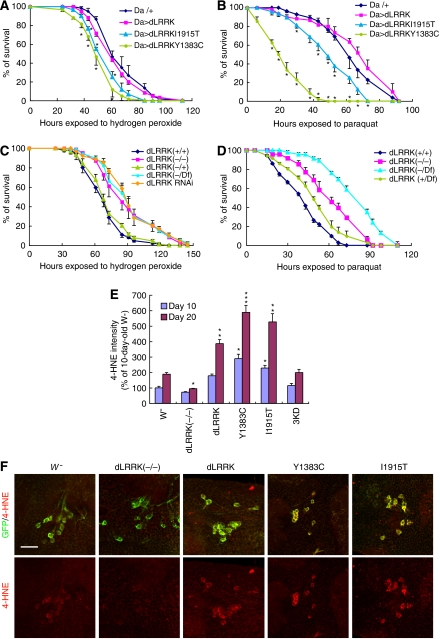

We further analysed animals with altered dLRRK activities to gain insight into the effect of dLRRK on DA neuron maintenance. Oxidative stress is suspected as one of the major causes of DA neuron degeneration in PD. We tested whether dLRRK Tg flies manifest altered response to oxidative stress. Compared with the controls, flies ubiquitously expressing dLRRK Y1383C and I1915T mutants showed significantly higher sensitivity to exogenous ROS inducers paraquat and H2O2 (Figure 2A and B). In contrast, dLRRK (−/−) or dLRRK RNAi animals were significantly more resistant (Figure 2C and D). Animals transheterozygous for dLRRK mutant and a chromosomal deficiency that covers dLRRK (Df/−) were also more resistant to H2O2 (Figure 2C and D).

Figure 2.

dLRRK regulates stress resistance. (A) Response of dLRRK Tg flies to H2O2 treatment. Error bars show s.d. from four repeated experiments. *P<0.05, Y1383C and I1915T versus Da-Gal4/+ control (all, n=60). (B) Response of dLRRK Tg to paraquat treatment. Error bars show s.d. from three repeated experiments. *P<0.05, Y1383C (n=48) and I1915T (n=48) versus Da-Gal4/+ (n=84). (C) Response of dLRRK(−/−) (n=85), dLRRK(Df/−) (n=84) and dLRRK RNAi flies (n=85) to H2O2 treatment. Error bars show s.d. from three repeated experiments. P<0.01 versus dLRRK(+/+) control (n=89) for all values at 61–128 h. Df/+ and dLRRK(+/+) serve as controls. Transgene and RNAi expressions were directed by Da-Gal4 in A–C. (D) Response of dLRRK(−/−) (n=48) and dLRRK(Df/−) flies (n=46) to paraquat treatment. Error bars show s.d. from three repeated experiments. P<0.001, versus dLRRK(+/+) (n=72) for all values at 24–73 h. (E) Statistical analysis of 4-HNE levels among the indicated genotypes crossed with a TH-Gal4>UAS-GFP line at 10- and 20-day of age raised at 29°C. 4-HNE levels from 25–30 TH+ neurons in the PPL1 clusters were quantified after normalization with GFP signal. *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 versus w− × TH-Gal4>GFP cross (w−). (F) Representative images of PPL1 clusters of the indicated genotypes double-stained for GFP (green) and 4-HNE (red). Scale bar=20 μm.

To investigate whether dLRRK is involved in cellular response to endogenous oxidative stress, we examined untreated flies for the extent of oxidative damage as measured by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE) immunostaining of lipid peroxidation. An age-dependent increase of 4-HNE level in DA neurons was evident in control flies (Figure 2E and F). In age-matched dLRRK(−/−) flies, 4-HNE level was significantly reduced (Figure 2E and F). In contrast, dLRRK Tg animals showed significantly increased 4-HNE levels (Figure 2E and F), with mutant dLRRK showing stronger effect than WT dLRRK. Changes of 4-HNE levels in dLRRK(−/−) and Tg animals were confirmed by dot blot analysis of 4-HNE adducts (Supplementary Figure 5A). We also used 2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate staining, which is an indicator of hydroxyl-free radical levels, to analyse dLRRK(−/−) and Tg flies. Hydroxyl-free radical levels were significantly reduced in dLRRK (−/−) and dLRRK(Df/−) flies, whereas an increase was observed in dLRRK Tg flies (Supplementary Figure 5B). These results suggest a physiological function of dLRRK in handling oxidative stress and a pathological function of heightened oxidative stress in mediating the toxicity of mutant LRRK2.

dLRRK genetically interacts with genes in the TSC/Rheb/TOR/4E-BP pathway

As our previous studies implicated altered PTEN/PI3K/Akt signalling in fly PD models (Yang et al, 2005), we tested possible genetic interaction of dLRRK with this pathway. dLRRK exhibited strong interaction with the TSC/Rheb/TOR/4E-BP pathway, a downstream branch of the PTEN/PI3K/Akt signalling network that regulates cell growth and cell size through protein synthesis. For instance, inhibition of TOR signalling through the co-overexpression of TSC1 and TSC2 inhibited cell growth in the fly eye (Gao and Pan, 2001; Potter et al, 2001). This was enhanced by the loss of dLRRK (Supplementary Figure 6C), although loss of dLRRK in an otherwise WT background had no effect (Supplementary Figure 6A and F). Conversely, stimulation of TOR signalling by Rheb overexpression enhanced cell growth (Saucedo et al, 2003), which was partially suppressed by the loss of dLRRK (Supplementary Figure 6E and G). Overexpression of a constitutively active form of d4E-BP (4E-BP(LL)), which has stronger affinity for eIF4E (Miron et al, 2001), caused a mild reduction of eye size (Supplementary Figure 6H). This effect was significantly enhanced by the loss of dLRRK (Supplementary Figure 6I). As the numbers of ommatidia per fly eye and rhabdomeres per ommatidium were not changed (Supplementary Figure 6J and K), the reduction of eye size was mostly due to a reduction of cell size, a measure of cell growth. The genetic interaction between dLRRK and 4E-BP was also evident in other tissues. Overexpression of 4E-BP(LL) in wing imaginal discs with the MS1096-Gal4 driver resulted in a moderate reduction of wing size (Miron et al, 2001), which was enhanced by the loss of dLRRK (Supplementary Figure 6L and N). The effect of removal of dLRRK on TSC1, TSC2 and Rheb overexpression was recapitulated by dLRRK knockdown and was rescued by the introduction of dLRRK WT but not 3KD transgenes (Supplementary Figure 7). These results suggest that dLRRK positively regulates cell growth through interaction with the TSC/Rheb/TOR/4E-BP pathway of protein translational control.

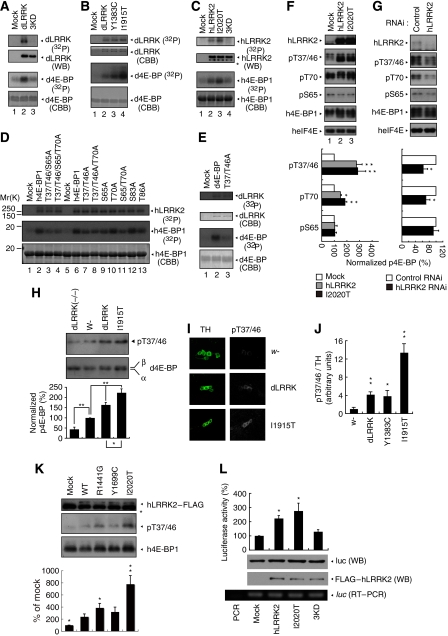

LRRK2 phosphorylates 4E-BP

We then sought to investigate the molecular mechanism underlying the effect of dLRRK on protein translation. To study its biochemical function, we purified dLRRK from transfected 293T cells by immunoprecipitation (IP). dLRRK purified this way possessed kinase activity, as shown by autophosphorylation (Figure 3A, upper panel in lane 2 compared with lane 1). As a control, we similarly purified a mutant dLRRK containing three point mutations (3KD), including the K1781 mutation predicted to disrupt ATP-binding (Greggio et al, 2006). The 3KD mutant exhibited no kinase activity, suggesting that the activity detected above was derived from dLRRK rather than some associated kinases in the IP complex (Figure 3A, lane 3). We also purified dLRRK containing PD-associated point mutations. The kinase activity of dLRRK containing the I1915T mutation was notably higher than WT dLRRK (Figure 3B, lane 4 compared with lane 2).

Figure 3.

dLRRK and hLRRK2 phosphorylate 4E-BP. (A–C) In vitro kinase assays using dLRRK and d4E-BP (A, B) or hLRRK2 and h4E-BP1 (C) as kinase–substrate pairs. Mock immunoprecipitate (IP) serves as control. Autoradiography (P32), western blot (WB) and Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) staining of the gels are shown. The asterisk in C marks a putative truncated form of hLRRK2 often observed in the IP fraction. (D, E) In vitro kinase assay using hLRRK2 (D) or dLRRK (E) as the kinase and a series of wild-type (WT) and mutant h4E-BP1 (D) or d4E-BP (E) as substrates. Mock IP serves as kinase control. CBB: protein loading control. The Ser or Thr residues mutated to Ala are indicated. (F, G) Western blot analysis showing effects of altered hLRRK2 activities on endogenous h4E-BP1 phosphorylation in 293T cells, which were starved for 24 h and then stimulated with 1 μg/ml insulin for 30 min. (F) Overexpression of WT and I2020T mutant hLRRK2 increased h4E-BP1 phosphorylation at T37/T46 and T70. Mock transfection serves as control. (G) Knockdown of hLRRK2 by RNAi reduced h4E-BP1 phosphorylation at T37/T46 and T70. Control: a non-targeting siRNA. Graphs show relative levels of p-T37/T46, p-T70 and p-S65 after normalization with total h4E-BP1 level. Values represent means±s.d. from three experiments (*P<0.05; **P<0.01 in Bonferroni/Dunn test). (H) dLRRK influences d4E-BP phosphorylation in vivo. d4E-BP protein was immunoprecipitated with a d4E-BP antibody from fly brain extracts of the indicated genotypes. Immunoprecipitated d4E-BP was detected by western blot with p-T37/T46 (upper) and total d4E-BP (lower) antibodies. Bands corresponding to phosphorylated (β) and non-phosphorylated forms (α) of d4E-BP are indicated in the total d4E-BP western. Graph shows relative level of p-T37/T46 after normalization with total d4E-BP level. Values represent means±s.d. from three experiments (*P<0.05; **P<0.01 in Bonferroni/Dunn test). (I, J) Immunohistochemical analysis showing that dLRRK promotes d4E-BP phosphorylation. Adult brain TH-positive neurons were co-stained with anti-TH and anti-p-T37/T46 in control w− or dLRRK Tg crossed with TH-Gal4. Representative images are shown in I. The p-T37/T46 signals were quantified after normalization with TH signals. Values represent means±s.d. from three independent experiments (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). (K) Western blot analysis showing effects of pathogenic hLRRK2 mutations on h4E-BP1 phosphorylation at T37/T46 sites in serum-starved 293T cells. The graph shows quantification of the relative level of p-T37/T46 after normalization with total h4E-BP1 level. Values represent means±s.d. from three independent experiments (*P<0.05; **P<0.01 versus hLRRK2 WT). (L) hLRRK2 stimulates protein synthesis in vitro in a kinase activity-dependent manner. Immunopurified FLAG–hLRRK2 WT, I2020T and 3KD proteins together with capped firefly luciferase mRNA were incubated in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (Promega) for 2.5 h at 30 °C. The activity of luciferase translated in the lysate was measured (graph, means±s.d. from three independent experiments). *P<0.05 versus mock. Western blot and RT–PCR was performed for estimation of protein and mRNA levels in the lysate. PCR without RT (PCR) serves as a negative control for RT–PCR.

Having obtained active dLRRK kinase, we next searched for its substrate(s). On the basis of the genetic interaction data, we tested candidate proteins in the TSC/Rheb/TOR/4E-BP signalling pathway. Robust phosphorylation of d4E-BP by dLRRK was detected (Figure 3A, lane 2). The activities of WT and I1915T mutant dLRRK towards d4E-BP correlated with their autophosphorylation activity (Figure 3B, lanes 2–4). eIF4E, the binding partner of 4E-BP and itself a phospho protein, was not phosphorylated by dLRRK (Supplementary Figure 8), supporting the specificity of dLRRK action towards d4E-BP. The situation holds true for the human proteins, with purified hLRRK2 robustly phosphorylating h4E-BP1 and the I2020T mutant possessing a higher activity (Figure 3C, lane 3 compared with lane 2).

To precisely map the phosphorylation site(s) in h4E-BP1, we made a series of Ser/Thr to Ala substitutions in h4E-BP1 and tested their effects on phosphorylation by hLRRK2 in vitro. Mutating T37/T46 and S65 reduced the amount of P32 incorporation, whereas mutating T70 and S83 had minimal effect (Figure 3D, lanes 7 and 9 compared with lanes 10 and 12). Combining T37/T46A and S65A mutations further reduced P32 incorporation (Figure 3D, lane 3). Addition of a T70A mutation into the T37/T46/S65A triple mutant background had no further effect (Figure 3D, lane 4 compared with lane 3). Western blot analysis of in vitro-phosphorylated h4E-BP1 with phospho-specific antibodies showed that the T37/T46 and S65 sites were directly phosphorylated by hLRRK2 (Supplementary Figure 9). Similarly, T37/T46A mutations in Drosophila 4E-BP reduced its phosphorylation by dLRRK (Figure 3E, lane 3 compared with lane 2). These in vitro results suggest that T37/T46 and S65 in 4E-BP represent major LRRK2 target sites.

To verify the in vitro phosphorylation result, we examined the effect of overexpression or knockdown of hLRRK2 on h4E-BP1 phosphorylation. A clear increase of h4E-BP1 phosphorylation at T37/T46 was observed in cells transfected with WT or mutant hLRRK2 (I2020T) (Figure 3F, lanes 2 and 3 compared with lane 1). In contrast, p-T37/T46 level was reduced in cells transfected with hLRRK2 siRNA, which effectively knocked down hLRRK2 expression (Figure 3G), whereas a control siRNA had no effect. As mTOR is known to affect 4E-BP phosphorylation, we tested whether hLRRK2 might exert an effect through mTOR. No change in mTOR phosphorylation or protein level was observed when hLRRK2 activity was altered (Supplementary Figure 10). Thus, the T37/T46 sites in h4E-BP1 appeared to be physiological hLRRK2 target sites. Despite the fact that T70 was not directly modified by hLRRK2 in vitro, its phosphorylation was affected by alterations of hLRRK2 in the cultured cells (Figure 3F and G). This is consistent with the notion that p-T37/T46 may prime subsequent T70 phosphorylation (Gingras et al, 2001) by other kinases. Alternatively, T70 could be a direct target of dLRRK in vivo. On the other hand, although S65 was modified by hLRRK2 in vitro, its phosphorylation was not affected by hLRRK2 in cultured cells (Figures 3F and G). The S65 site may be more tightly regulated by other kinases or phosphatases in vivo.

We sought for further in vivo evidence that LRRK2 is a 4E-BP kinase. Western blot and immunostaining of dLRRK Tg and mutant flies showed that phosphorylation of d4E-BP at T37/T46 sites was increased in dLRRK Tg but decreased in dLRRK(−/−) flies, supporting the fact that T37/T46 in d4E-BP are in vivo dLRRK target sites (Figure 3H–J). Note that, in dLRRK(−/−) mutant flies, phosphorylation of d4E-BP at T37/T46 sites was reduced but not abolished, suggesting that there exist other kinase(s) that exert an effect on these sites. Both WT and a pathogenic LRRK2 effectively stimulated the phosphorylation of T37/T46 sites of 4E-BP1 to similar levels upon insulin treatment (Figure 3F). Under starvation (serum-free) condition, however, some pathogenic mutants exhibit higher kinase activity than WT LRRK2 (Figure 3K). These data suggested that LRRK2 interacts with the insulin/IGF signalling pathway to regulate 4E-BP phosphorylation, but the kinase activity of some pathogenic mutants is not dependent on insulin/IGF stimulation.

The genetic interaction between LRRK2 and the TSC/Rheb/TOR/4E-BP pathway of growth control and the phosphorylation of 4E-BP by LRRK2 suggest that LRRK2 is a positive regulator of protein translation. Consistent with this notion, direct addition of purified hLRRK2 WT and I2020T proteins to an in vitro translation system effectively stimulated the translation of a luciferase reporter mRNA, whereas hLRRK2 3KD had no effect (Figure 3L).

Activities of 4E-BP and eIF4E are important for cellular stress response and DA neuron maintenance

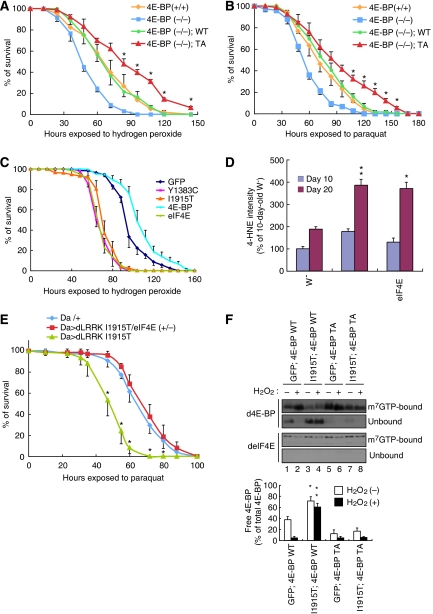

Previous studies revealed a function for d4E-BP in conferring resistance against starvation and oxidative stress (Teleman et al, 2005; Tettweiler et al, 2005). We asked whether phosphorylation of 4E-BP at T37/T46 residues, which is promoted by dLRRK kinase activity, affects resistance to oxidative stress in vivo. For this purpose, we generated Tg flies expressing d4E-BP T37/T46A (TA) mutant protein. Whereas expression of d4E-BP WT restored oxidative stress resistance in d4E-BP(−/−), expression of similar levels of d4E-BP TA resulted in higher resistance against oxidative stress (Figure 4A and B, and Supplementary Figure 11). This suggests that complete blockage of 4E-BP T37/T46 phosphorylation and the consequent tighter binding and stronger inhibition of eIF4E lead to higher stress resistance. To test this idea further, we asked whether manipulation of eIF4E is sufficient to alter oxidative stress response. Overexpression of deIF4E significantly sensitized animals to oxidative stress treatments, similar to the effect induced by mutant dLRRK overexpression (Figure 4C). Furthermore, deIF4E Tg animals showed a significant increase of 4-HNE in the absence of stress (Figure 4D), suggesting that excessive eIF4E activity altered endogenous stress response and resulted in more oxidative damages.

Figure 4.

The eIF4E/4E-BP pathway is important for handling oxidative stress. (A, B) d4E-BP TA confers H2O2 (A) and paraquat (B) resistance. d4E-BP WT or TA mutant were expressed in the d4E-BP(−/−) background under DA-Gal4 control. *P<0.05, d4E-BP(−/−); TA (n=76 in A; n=78 in B) versus d4E-BP(−/−); WT (n=80 in A; n=82 in B). (C) Oxidative stress responses of dLRRK, deIF4E and d4E-BP Tg flies driven by Da-Gal4. deIF4E Tg (n=72) and the dLRRK Y1383C (n=72) or I1915T (n=85) Tg were more sensitive to H2O2 treatment than the GFP Tg control (n=90) (P<0.01 for all values at 72–120 h), whereas d4E-BP Tg (n=90) was more resistant than the control (P<0.05 versus GFP Tg for the values at 72–144 h). (D) Overexpression of deIF4E or dLRRK increases 4-HNE levels in DA neurons. TH-Gal4>GFP was crossed with the indicated genotypes as shown in Figure 2E. Values represent means±s.d. (*P<0.05; **P<0.01 versus age-matched w−, n=25–30). Error bars in (A–D) show s.d. from three repeated experiments. (E) Reduction of deIF4E function suppresses vulnerability of dLRRK I1915T to oxidative stress induced by paraquat. dLRRK I1915T was expressed in the deIF4E(+/+) or deIF4E(+/−) background with DA-Gal4. *P<0.006, Da>dLRRK I1915T/deIF4E (+/−) (n=74) versus Da>dLRRK I1915T (n=75). (F) m7GTP pull-down assay showing the effect of dLRRK I1915T on free eIF4E levels. eIF4E was precipitated using m7GTP-sepharose from the brain tissues of flies with or without 5% H2O2 treatment for 24 h. eIF4E-bound (m7GTP-bound) and free (unbound) 4E-BP were estimated. Graph shows the percentage of free 4E-BP in total 4E-BP after normalization with m7GTP-bound eIF4E level. Values represent means±s.d. from three experiments (*P<0.05; **P<0.01 versus GFP; 4E-BP WT in corresponding treatment).

Consistent with the above findings, removal of one copy of deIF4E in dLRRK I1915T Tg flies increased resistance against oxidative stress (Figure 4E). We further tested whether the co-expression of d4E-BP TA mutant, by inhibiting the release of d4E-BP from deIF4E, rendered dLRRK I1915T flies more resistant to oxidative stress. This was indeed the case (Supplementary Figure 12). We next used 7-methyl GTP (m7GTP) sepharose-binding assay to biochemically assess the level of 4E-BP-free eIF4E, an indicator of translation efficiency, in the various genetic backgrounds. In vivo, eIF4E protein level is fairly constant and both the 4E-BP-bound and 4E-BP-free forms of eIF4E bind to m7GTP sepharose beads. By measuring the amount of 4E-BP-bound eIF4E, we can get an estimate of 4E-BP-free, active eIF4E. As shown in Figure 4F, in d4E-BP WT Tg animals co-expressing GFP, a significant portion of d4E-BP WT was released from deIF4E under normal conditions; however, under oxidative stress condition, almost all d4E-BP WT was bound to deIF4E (Figure 4F, lanes 1 and 2). The amount of d4E-BP WT released from deIF4E was increased in the presence of dLRRK I1915T under both normal and oxidative stress conditions (Figure 4F, lanes 3 and 4). In contrast, d4E-BP TA was tightly bound to eIF4E in the presence or absence of dLRRK I1915T, and under normal or stress conditions (Figure 4F, lanes 5–8). These results suggested that dLRRK releases the inhibition of eIF4E by 4E-BP, enabling free eIF4E to engage in translation.

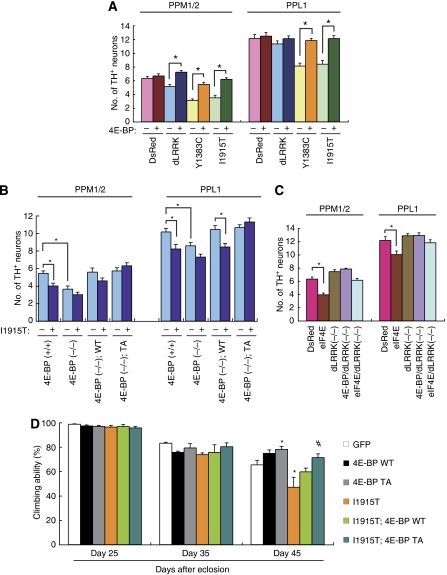

We next tested whether d4E-BP and deIF4E influence dLRRK-mediated DA neurodegeneration in the flies. Whereas overexpression of d4E-BP had no effect on DA neuron number in control Tg flies, it partially suppressed the DA neuron loss phenotype seen in dLRRK Tg flies (Figure 5A). Introduction of d4E-BP TA fully protected against DA neuron loss caused by dLRRK I1915T (Figure 5B). Furthermore, introduction of d4E-BP WT rescued DA neuron loss seen in d4E-BP(−/−) flies (Figure 5B). Supporting a function for deregulation of the eIF4E/4E-BP pathway in inducing DA neuron loss, overexpression of deIF4E alone caused a reduction of DA neurons; however, in dLRRK(−/−) background, this effect of deIF4E was suppressed (Figure 5C). Given that DA neuron loss was observed in aged dLRRK Tg flies, we searched for evidence of motor dysfunction caused by DA degeneration. As shown in Figure 5D, dLRRK I1915T expression caused locomotor dysfunction with age, which was improved by the co-expression of d4E-BP TA (Figure 5D). Taken together, these results indicate that the interaction between dLRRK and the eIF4E/4E-BP pathway is intimately involved in the maintenance of DA neurons.

Figure 5.

4E-BP overexpression suppresses dysfunction and degeneration of DA neuron induced by mutant dLRRK. (A) d4E-BP co-expression rescues dLRRK overexpression-induced DA neuron loss (*P<0.01 in Student's t-test, n=12). TH-Gal4 was used to direct transgene expression and 60-day-old flies aged at 25 °C were analysed. (B) d4E-BP TA protects against DA neuron loss in dLRRK I1915T Tg flies. TH-Gal4 was used to direct transgene expression and 30-day-old flies aged at 29 °C were analysed. *P<0.05, n=14. (C) dLRRK LOF rescues deIF4E overexpression-induced DA neuron loss (*P<0.01, n=12). TH-Gal4 crosses were analysed as in (A). (D) Pan-neuronal expression of dLRRK I1915T under elav-Gal4 control leads to gradual motor defect with age. The loss of climbing ability in dLRRK I1915T-expressing flies was rescued by 4E-BP TA expression. GFP serves as control. The values represent means±s.d. from 20 trials (n=30; *P<0.05 versus GFP; #P<0.01 versus I1915T by one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni/Dunn test). The genotypes are as follows: elav-Gal4>UAS-GFP (GFP), elav-Gal4>UAS-4E-BP WT (4E-BP WT), elav-Gal4>UAS-4E-BP TA (4E-BP TA), elav-Gal4>UAS-dLRRK I1915T (I1915T), elav-Gal4>UAS-dLRRK I1915T/UAS-4E-BP WT (I1915T; 4E-BP WT), elav-Gal4>UAS-dLRRK I1915T/UAS-4E-BP TA (I1915T; 4E-BP TA). Male flies were used for the assay.

Discussion

In this study, we used Drosophila as a model system to understand the normal physiological function of LRRK2 and how its dysfunction leads to DA neurodegeneration. We provide genetic and biochemical evidence that dLRRK modulates the maintenance of DA neuron by regulating protein synthesis. We demonstrate that LRRK2 primes phosphorylation of 4E-BP and that this event has an important function in mediating the pathogenic effects of mutant dLRRK. These results for the first time link deregulation of the eIF4E/4E-BP pathway of protein translation with DA degeneration in PD.

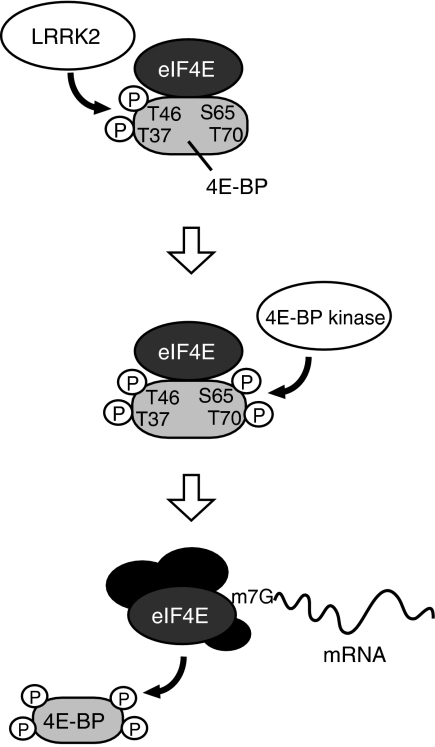

eIF4E is a key component of the eIF4F complex that initiates cap-dependent protein synthesis. It has long been recognized that a key mechanism regulating eIF4E function is through phosphorylation-induced release of 4E-BP from eIF4E. A number of candidate kinases, including mTOR, have been implicated on the basis of in vitro or cell culture studies, but the physiological kinases remain to be identified. We show here that LRRK2 is one of the physiological kinases for 4E-BP. LRRK2 exerts an effect on 4E-BP primarily at the T37/T46 sites. Phosphorylation at T37/T46 by LRRK2 likely facilitates subsequent phosphorylation at T70 and S65 in vivo by other kinase or LRRK2 itself. 4E-BP phosphorylation by LRRK2, therefore, could serve as an initiating event in an ordered, multisite phosphorylation process to generate hyperphosphorylated 4E-BP (Figure 6), similar to the phosphorylation of the Alzheimer's disease-associated tau (Nishimura et al, 2004). Our results show that LRRK2 is not the only kinase that phosphorylates 4E-BP T37/T46 sites (Figure 3H). Similarly, 4E-BP is unlikely the only substrate of LRRK2. A recent study showed that human LRRK2 phosphorylates moesin (Jaleel et al, 2007), the physiological relevance of which remains to be determined.

Figure 6.

A model depicting 4E-BP phosphorylation by dLRRK. Phosphorylation of 4E-BP at T37/T46 residues by LRRK2 (upper) facilitates subsequent phosphorylation at T70 and S65 (middle). Hyperphosphorylated 4E-BP is released from mRNA cap-binding protein eIF4E, which leads to the formation of an initiation factor complex including eIF4E for protein translation (lower).

The role of 4E-BP in regulating eIF4E function has been well established in vitro. Recent studies in Drosophila, however, have revealed the complexity of the in vivo function of 4E-BP. Loss of the only d4E-BP gene does not affect cell size or animal viability (Bernal and Kimbrell, 2000), suggesting that it is dispensable for cell growth or survival under normal conditions. However, d4E-BP mutant flies are defective in responses to various stress stimuli (Bernal and Kimbrell, 2000; Teleman et al, 2005; Tettweiler et al, 2005). d4E-BP has also been proposed to exert an effect as a metabolic brake for fat metabolism under stress conditions (Teleman et al, 2005). Whether this role of 4E-BP is relevant to dLRRK function in stress resistance and DA neuron maintenance remains to be tested. eIF4E, the target of 4E-BP, functions primarily in regulating general protein translation in vitro. It has been suggested that overactivation of eIF4E is linked to the aging process and lifespan regulation in vivo (Ruggero et al, 2004; Syntichaki et al, 2007). We observed that overexpression of eIF4E as well as dLRRK leads to an aging-related phenotype in DA neurons, which strongly suggested that chronic attenuation of 4E-BP activity promotes oxidative stress and consequent aging in DA neurons. This is consistent with the finding of similar patterns of gene expression under oxidative stress and aging conditions (Landis et al, 2004), and the fact that PD caused by LRRK2 mutations is of late onset, with aging being a major risk factor.

We analysed effects of removing dLRRK activity using a transposon insertion allele (dLRRK−), a chromosomal deletion allele (dLRRK Df) and gene knockdown (dLRRK RNAi). dLRRK(−/−), dLRRK (Df/−) and dLRRK RNAi flies are all resistant to oxidative stress treatments and show reduced endogenous ROS damages. In the paraquat treatment assay, dLRRK (Df/−) appeared more resistant than dLRRK(−/−) (Figure 2D). It is possible that dLRRK(−/−), which contains a transposon insertion in the COR domain of dLRRK, is not a null allele, although we have not been able to detect a truncated protein product using an antibody against the N-terminus of the protein. Alternatively, the chromosomal deletion in dLRRK (Df) may include other gene(s) relevant to stress sensitivity. One candidate is the gene for PI3K Dp110 subunit. A recent study reported that dLRRK(−/−) animals are slightly sensitive to hydrogen peroxide but are comparable to control animals in response to paraquat (Wang et al, 2008). It is possible that the different genetic backgrounds and the nutrient conditions may account for the divergent results. In our studies, we backcrossed the mutant chromosome to w− WT background for six generations in an effort to eliminate potential background mutations. A consistent finding from our study and two other studies of dLRRK(−/−) animals is that dLRRK is dispensable for the maintenance of DA neurons (Lee et al, 2007; Wang et al, 2008), although in one study it was reported that dLRRK(−/−) animals show reduced TH immunoreactivity and shrunken morphology of DA neurons (Lee et al, 2007). In contrast, overexpression of hLRRK2 containing a pathogenic G2019S mutation (Liu et al, 2008), or overexpression of mutant dLRRK as reported here, caused DA neuron degeneration, supporting the fact that the pathogenic mutations cause disease by a GOF mechanism.

The pathogenesis caused by mutations in LRRK2 could be partially explained by their higher kinase activity. Indeed, some pathogenic mutants of both hLRRK2 and dLRRK show elevated kinase activity towards 4E-BP. However, other mutants (e.g., hLRRK2 Y1699C and dLRRK Y1383C) did not show elevated kinase activity in vivo. Therefore, these pathogenic hLRRK2 mutations might confer cellular toxicity through mechanisms other than protein translation. For example, some hLRRK2 mutants are prone to aggregation in cultured cells (Smith et al, 2005; Greggio et al, 2006). Consistently, dLRRK Y1383C mutant appeared as more prominent vesicular aggregates in fly DA neurons (data not shown). Nevertheless, the facts that overexpression of eIF4E is sufficient to confer hypersensitivity to oxidative stress and DA neuron loss and that co-expression of 4E-BP suppresses the dopaminergic toxicity caused by more than one pathogenic dLRRK mutants provide compelling evidence that the eIF4E–4E-BP axis has an important function in mediating the pathogenic effects of overactivated LRRK2. The more downstream events that lead to DA neurotoxicity remain to be elucidated. So far, we have found no clear evidence of altered autophagy, caspase activation or DNA fragmentation (data not shown).

There are several possibilities of how elevated protein translation could contribute to PD pathogenesis. First, given that protein synthesis is a highly energy-demanding process, stimulation of protein translation by LRRK2 could perturb cellular energy and redox homoeostasis. This could be especially detrimental in aged cells or stressed post-mitotic cells such as DA neurons. Second, increased protein synthesis could lead to the accumulation of misfolded or aberrant proteins, overwhelming the already compromised ubiquitin proteasome and molecular chaperone systems in aged or stressed cells. Third, altered LRRK2 kinase activity may affect synapse structure and function, which is known to involve local protein synthesis. Deregulation of this process could lead to synaptic dysfunction and eventual neurodegeneration.

Materials and methods

Drosophila genetics

See Supplementary data for details.

RT–PCR, plasmids and siRNAs

See Supplementary data for details.

Cell culture, immunopurification, western blot analysis and m7GTP pull-down assay

Transfection of 293T cell, immunopurification of FLAG-protein from the transfected cell lysate and western blot analysis were performed as described previously (Imai et al, 2000, 2001). For preparation of fly samples for western blot analysis, fly heads were directly homogenized in 20 μl of SDS sample buffer per head using a motor-driven pestle. After centrifugation at 16 000 g for 10 min, the supernatant was used in SDS–PAGE. For immunoprecipitation or m7GTP pull-down assay, fly heads were homogenized in 10 μl of lysis buffer per head (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM DTT, 60 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 20 mM NaF and complete inhibitor cocktail (Roche)). After centrifugation at 16 000 g for 30 min, the supernatant was subjected to the assays. For m7GTP pull-down assay, the supernatant of each lysate from 15 fly heads was incubated with 15 μl of m7GTP-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 2 h. The precipitates were washed four times with lysis buffer. The precipitates (m7GTP-bound) and the flow through (unbound) were analysed by western blot. Densitometry was analysed using Image J software from the US National Institute of Health (http//rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Antibodies

See Supplementary data for details of antibodies resources.

In vitro phosphorylation assay

FLAG–dLRRK or FLAG–hLRRK2 immunopurified from transfected 293T cells and mock fractions processed by the same procedures were used as kinase sources. Five micrograms of His–d4E-BP or His–h4E-BP1 were incubated with FLAG–dLRRK or FLAG–hLRRK2 in a kinase reaction buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 15 mM MgCl2, 5 mM EGTA, 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM β-glycerolphosphate and 2.5 μCi [γ-32P]-ATP) for 30 min at 30 °C. The reaction mixture was suspended in SDS sample buffer and then subjected to SDS–PAGE and autoradiography.

Dopamine measurement

Monoamine measurement was performed as described previously (Yang et al, 2005), with investigators blind to the genotypes during the measurement.

Whole-mount immunostaining

Counting of TH-positive neurons was performed by whole-mount immunostaining of brain samples as described previously (Yang et al, 2006). Immunohistochemical analysis for 4-HNE was carried out in whole-mount brain samples of animals originated from TH-Gal4>UAS-GFP crossed to the indicated genotypes. Anti-4HNE signals were normalized with GFP signals derived from the UAS-GFP transgene expressed in the same TH-positive neurons. Image J software was used for signal quantification. For dot blot analysis of 4-HNE, total lysates made from fly heads were spotted onto a PVDF membrane and subsequently incubated with anti-4HNE (1:15) overnight. As a control, we used western blot analysis of β-tubulin from the same extracts. Properties of the 4-HHE antibody are described on the manufacturer's Web site: http://www.jaica.com/biotech/e/. Immunohistochemical analyses were performed using a Carl Zeiss laser scanning microscope system.

Oxidative stress assay

The survival rate of 10-day-old male adult flies (n=15–20 per vial) kept in a vial containing a tissue paper socked with 0.5% H2O2 or 2 mM paraquat prepared in Schneider's insect medium was measured as described (Yang et al, 2005). To control for isogeny, dLRRK(−/−), 4E-BP(−/−), UAS-4E-BP and the Da-Gal4 driver were backcrossed to w− background for six generations. For studies in transgenic overexpression, the UAS-dLRRK transgenes, UAS-dLRRK RNAi and UAS-d4E-BP TA transgenic lines were generated in w− background and thus have a matched genetic background. For the analysis in Figures 4 and 5, Thor1 (4E-BP null) and its revertant served as 4E-BP(−/−) and 4E-BP(+/+), respectively. UAS-d4E-BP WT and UAS-d4E-BP TA transgenics, which shows similar protein expression of d4E-BP, were backcrossed to 4E-BP(−/−) background for five generations.

Climbing assay

The climbing assay was performed similarly to a previously described protocol (Feany and Bender, 2000). Thirty flies were placed in a plastic vial (18.6 cm in height × 3.5 cm2 in area) and gently tapped to bring them down to the bottom of the vial. Flies were given 18 s to climb, and the number of flies above 6 cm from the bottom was counted. Twenty trials were performed for each time point for the same set of flies.

Statistical analysis

Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was performed in multiple groups unless otherwise indicated. If positive (P<0.05), the means between the control and the specific groups were analysed using the Dunnett's test.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary Figure Legends

Supplementary Figures

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs B Edgar, DA Kimbrell, P Lasko, D Pan, N Sonenberg, Z Zhang, T Xu and the Drosophila Stock centers for flies; Drs NJ Dyson, P Lasko, N Sonenberg and J Sierra, and RH Wharton for antibodies; Drs P Bitterman and V Polunovsky for plasmids; and Dr S Guo for reading the manuscripts. Special thanks go to J Quach, Y Zhang and W Lee for technical supports and members of the Lu lab for discussions. Supported by the NIH (R21 NS056878-01, R01 AR054926-01), the McKnight, Beckman and Sloan Foundations (BL), the Naito Foundation, JSPS Postdoctoral Fellowships for Research Abroad and Program for Young Researchers from Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology commissioned by MEXT in Japan (YI).

References

- Bernal A, Kimbrell DA (2000) Drosophila Thor participates in host immune defense and connects a translational regulator with innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6019–6024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadden P, Haystead TA, Lawrence JC Jr (1997) Identification of phosphorylation sites in the translational regulator, PHAS-I, that are controlled by insulin and rapamycin in rat adipocytes. J Biol Chem 272: 10240–10247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feany MB, Bender WW (2000) A Drosophila model of Parkinson's disease. Nature 404: 394–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Pan D (2001) TSC1 and TSC2 tumor suppressors antagonize insulin signaling in cell growth. Genes Dev 15: 1383–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Gygi SP, Raught B, Polakiewicz RD, Abraham RT, Hoekstra MF, Aebersold R, Sonenberg N (1999a) Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: a novel two-step mechanism. Genes Dev 13: 1422–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Raught B, Gygi SP, Niedzwiecka A, Miron M, Burley SK, Polakiewicz RD, Wyslouch-Cieszynska A, Aebersold R, Sonenberg N (2001) Hierarchical phosphorylation of the translation inhibitor 4E-BP1. Genes Dev 15: 2852–2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N (1999b) eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem 68: 913–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloeckner CJ, Kinkl N, Schumacher A, Braun RJ, O'Neill E, Meitinger T, Kolch W, Prokisch H, Ueffing M (2006) The Parkinson disease causing LRRK2 mutation I2020T is associated with increased kinase activity. Hum Mol Genet 15: 223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greggio E, Jain S, Kingsbury A, Bandopadhyay R, Lewis P, Kaganovich A, van der Brug MP, Beilina A, Blackinton J, Thomas KJ, Ahmad R, Miller DW, Kesavapany S, Singleton A, Lees A, Harvey RJ, Harvey K, Cookson MR (2006) Kinase activity is required for the toxic effects of mutant LRRK2/dardarin. Neurobiol Dis 23: 329–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heesom KJ, Avison MB, Diggle TA, Denton RM (1998) Insulin-stimulated kinase from rat fat cells that phosphorylates initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 on the rapamycin-insensitive site (serine-111). Biochem J 336 (Part 1): 39–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcik M, Sonenberg N (2005) Translational control in stress and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 318–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Soda M, Inoue H, Hattori N, Mizuno Y, Takahashi R (2001) An unfolded putative transmembrane polypeptide, which can lead to endoplasmic reticulum stress, is a substrate of Parkin. Cell 105: 891–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai Y, Soda M, Takahashi R (2000) Parkin suppresses unfolded protein stress-induced cell death through its E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase activity. J Biol Chem 275: 35661–35664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Corradetti MN, Guan KL (2005) Dysregulation of the TSC-mTOR pathway in human disease. Nat Genet 37: 19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaleel M, Nichols RJ, Deak M, Campbell DG, Gillardon F, Knebel A, Alessi DR (2007) LRRK2 phosphorylates moesin at threonine-558: characterization of how Parkinson's disease mutants affect kinase activity. Biochem J 405: 307–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P (2003) Oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol 53 (Suppl 3): S26–S36; discussion S28–S36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis GN, Abdueva D, Skvortsov D, Yang J, Rabin BE, Carrick J, Tavare S, Tower J (2004) Similar gene expression patterns characterize aging and oxidative stress in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 7663–7668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SB, Kim W, Lee S, Chung J (2007) Loss of LRRK2/PARK8 induces degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in Drosophila. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 358: 534–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Wang X, Yu Y, Li X, Wang T, Jiang H, Ren Q, Jiao Y, Sawa A, Moran T, Ross CA, Montell C, Smith WW (2008) A Drosophila model for LRRK2-linked parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 2693–2698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata IF, Wedemeyer WJ, Farrer MJ, Taylor JP, Gallo KA (2006) LRRK2 in Parkinson's disease: protein domains and functional insights. Trends Neurosci 29: 286–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miron M, Verdu J, Lachance PE, Birnbaum MJ, Lasko PF, Sonenberg N (2001) The translational inhibitor 4E-BP is an effector of PI(3)K/Akt signalling and cell growth in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol 3: 596–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, West AB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM (2005) Molecular pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci 28: 57–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura I, Yang Y, Lu B (2004) PAR-1 kinase plays an initiator role in a temporally ordered phosphorylation process that confers tau toxicity in Drosophila. Cell 116: 671–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simon J, van der Brug M, Lopez de Munain A, Aparicio S, Gil AM, Khan N, Johnson J, Martinez JR, Nicholl D, Carrera IM, Pena AS, de Silva R, Lees A, Marti-Masso JF, Perez-Tur J, Wood NW et al. (2004) Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson's disease. Neuron 44: 595–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter CJ, Huang H, Xu T (2001) Drosophila Tsc1 functions with Tsc2 to antagonize insulin signaling in regulating cell growth, cell proliferation, and organ size. Cell 105: 357–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD, Sonenberg N (2005) Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins. Nature 433: 477–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggero D, Montanaro L, Ma L, Xu W, Londei P, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP (2004) The translation factor eIF-4E promotes tumor formation and cooperates with c-Myc in lymphomagenesis. Nat Med 10: 484–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saucedo LJ, Gao X, Chiarelli DA, Li L, Pan D, Edgar BA (2003) Rheb promotes cell growth as a component of the insulin/TOR signalling network. Nat Cell Biol 5: 566–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WW, Pei Z, Jiang H, Moore DJ, Liang Y, West AB, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ross CA (2005) Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) interacts with parkin, and mutant LRRK2 induces neuronal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 18676–18681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenberg N, Rupprecht KM, Hecht SM, Shatkin AJ (1979) Eukaryotic mRNA cap binding protein: purification by affinity chromatography on sepharose-coupled m7GDP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 76: 4345–4349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syntichaki P, Troulinaki K, Tavernarakis N (2007) eIF4E function in somatic cells modulates ageing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 445: 922–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JP, Mata IF, Farrer MJ (2006) LRRK2: a common pathway for parkinsonism, pathogenesis and prevention? Trends Mol Med 12: 76–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teleman AA, Chen YW, Cohen SM (2005) 4E-BP functions as a metabolic brake used under stress conditions but not during normal growth. Genes Dev 19: 1844–1848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettweiler G, Miron M, Jenkins M, Sonenberg N, Lasko PF (2005) Starvation and oxidative stress resistance in Drosophila are mediated through the eIF4E-binding protein, d4E-BP. Genes Dev 19: 1840–1843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Tang B, Zhao G, Pan Q, Xia K, Bodmer R, Zhang Z (2008) Dispensable role of Drosophila ortholog of LRRK2 kinase activity in survival of dopaminergic neurons. Mol Neurodegener 3: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AB, Moore DJ, Biskup S, Bugayenko A, Smith WW, Ross CA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM (2005) Parkinson's disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 16842–16847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S, Ishihara H, Yamada T, Tamura A, Usui M, Tominaga R, Munakata Y, Satake C, Katagiri H, Tashiro F, Aburatani H, Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Miyazaki J, Sonenberg N, Oka Y (2008) ATF4-mediated induction of 4E-BP1 contributes to pancreatic beta cell survival under endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab 7: 269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Gehrke S, Haque ME, Imai Y, Kosek J, Yang L, Beal MF, Nishimura I, Wakamatsu K, Ito S, Takahashi R, Lu B (2005) Inactivation of Drosophila DJ-1 leads to impairments of oxidative stress response and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 13670–13675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Gehrke S, Imai Y, Huang Z, Ouyang Y, Wang JW, Yang L, Beal MF, Vogel H, Lu B (2006) Mitochondrial pathology and muscle and dopaminergic neuron degeneration caused by inactivation of Drosophila Pink1 is rescued by Parkin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 10793–10798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, Lichtner P, Farrer M, Lincoln S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Uitti RJ, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ, Pfeiffer RF, Patenge N, Carbajal IC, Vieregge P, Asmus F, Muller-Myhsok B, Dickson DW, Meitinger T, Strom TM et al. (2004) Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron 44: 601–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary Figure Legends

Supplementary Figures