Abstract

Transcriptional coactivators that regulate the activity of human RNA polymerase III (Pol III) in the context of chromatin have not been reported. Here, we describe a completely defined in vitro system for transcription of a human tRNA gene assembled into a chromatin template. Transcriptional activation and histone acetylation in this system depend on recruitment of p300 by general initiation factor TFIIIC, thus providing a new paradigm for recruitment of histone-modifying coactivators. Beyond its role as a chromatin-modifying factor, p300 displays an acetyltransferase-independent function at the level of preinitiation complex assembly. Thus, direct interaction of p300 with TFIIIC stabilizes binding of TFIIIC to core promoter elements and results in enhanced transcriptional activity on histone-free templates. Additional studies show that p300 is recruited to the promoters of actively transcribed tRNA and U6 snRNA genes in vivo. These studies identify TFIIIC as a recruitment factor for p300 and thus may have important implications for the emerging concept that tRNA genes or TFIIIC binding sites act as chromatin barriers to prohibit spreading of silenced heterochromatin domains.

It is well established that assembly of regulatory DNA sequences into nucleosomes represses transcription by restricting access of the transcriptional machinery to DNA (reviewed in reference 28). Thus, overcoming nucleosomal repression through alteration of chromatin structure is essential for gene activation. Eukaryotic cells contain at least two general classes of chromatin-modifying factors, the ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes (43) and histone-modifying enzymes that effect histone acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination (63). Whereas the function and mechanism of action of both types of factors have been extensively studied on genes transcribed by RNA polymerase II (Pol II), much less is known about chromatin-modifying factors involved in the regulation of Pol III-dependent genes.

Pol III synthesizes small structural RNAs such as 5S RNA, tRNA, adenovirus VA1 RNA, and U6 RNA. Accurate and specific transcription of DNA templates by Pol III requires the assistance of the general initiation transcription factors TFIIIB and TFIIIC and, in some cases, various gene-specific factors such as the 5S gene-specific factor TFIIIA (for review, see references 15 and 53). In the case of tRNA and VA1 genes (subclass 2 genes), gene-internal core promoter elements (A and B boxes) are recognized directly by TFIIIC, which in turn directs the sequential binding of TFIIIB and Pol III. Human TFIIIC has been chromatographically separated into two distinct activities, TFIIIC1 and TFIIIC2 (74). TFIIIC2 is a stable complex of six subunits (220, 110, 102, 90, 63, and 35 kDa) that binds directly to the B box (10a, 30, 75). TFIIIC1 displays no strong DNA-binding activity on its own but stabilizes TFIIIC2 binding to A and B boxes (66, 74). Other factors derived from TFIIIC preparations, such as coactivator PC4, also stabilize TFIIIC binding throughout promoter and terminator regions (64). A recent study has provided evidence that TFIIIC1 is identical to a TFIIIB subunit, Bdp1, that is only weakly associated with other TFIIIB components (68).

Human cells contain two functionally distinct TFIIIB activities (reviewed in reference 55). TFIIIB, which is specific for genes with internal promoter elements (e.g., 5S RNA, tRNA, and VA1 RNA), is composed of a stable TATA-binding protein (TBP)-Brf1 complex that associates reversibly with the SANT domain protein Bdp1 (for a description of a universal nomenclature for TFIIIB components, see reference 70). Full-length human Bdp1 is a large protein of 2,254 amino acids (aa) (27), the N-terminal portion of which has homology to yeast Bdp1. Unique structural features of the human protein include nine repeats of an acidic 55-aa motif with unknown function and a C-terminal domain (aa 1328 to 2254) displaying sequence motifs found in topoisomerase II and elongation factor 1β. Although full-length human Bdp1 was first described as the “transcription factor-like nuclear regulator” (TFNR) (27), its transcriptional activity has not been characterized to date. However, two shorter splice variants of the gene were shown to reconstitute in vitro transcription of both U6/7SK (subclass 3) and VA1 (subclass 2) genes. One form, TFIIIB150, contains the N-terminal 846 aa of Bdp1 (60). A second form, hB″, contains the N-terminal 1,388 aa of the full-length protein (56).

Early in vitro studies with 5S RNA genes demonstrated that preassembly of Pol III-transcribed genes into chromatin blocks transcription, whereas prebinding of accessory factors can prevent this repression (5, 12, 17, 61). However, transcriptionally active tRNA genes are highly resistant to repression by histones in vivo (reviewed in reference 52). Since nucleosome formation can be observed with promoter mutations that prevent binding of the transcription machinery, the lack of nucleosome structure apparently reflects successful competition of transcription factor binding over chromatin assembly (41). A key role for TFIIIC in overcoming nucleosome formation and transcriptional repression was first demonstrated for the yeast U6 gene, which contains intragenic A-box and B-box elements (7). Subsequently, human TFIIIC was found to contain at least two subunits (TFIIIC110 and TFIIIC90) with intrinsic histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activities and to bind to promoter elements in chromatin templates (23, 34). Addition of purified TFIIIC to HeLa nuclear extracts was shown to alleviate chromatin-mediated repression of a human tRNA gene assembled within a chromatin template (34), but a direct role for the TFIIIC HAT activities in these assays or in vivo has not been demonstrated.

Consistent with the notion that highly acetylated histones are a hallmark of transcriptionally active chromatin (28), the Pol III-transcribed 5S RNA genes are associated with hyperacetylated histones in active, but not inactive, states (22). Related, 5S gene-containing nucleosomal arrays with hyperacetylated histones have been reported to show enhanced transcription by Pol III relative to corresponding nucleosomal arrays with hypoacetylated histones, possibly due to the more unfolded state of the hyperacetylated template (62). Although histone acetylation has been reported to enhance binding of the 5S gene-specific transcription factor TFIIIA to a 5S gene-containing nucleosome (36), this applies only to a small subset of specifically positioned nucleosomes on 5S genes (21, 51). These observations leave open the possibility that acetylated histones act subsequent to TFIIIA binding and also raise the question as to how the histone modifications arise on active Pol III-transcribed genes. This is an especially interesting issue in the case of Pol III-transcribed genes (e.g., tRNA genes) that do not employ gene-specific activators.

Although the HATs involved in Pol III-mediated transcription are unknown, p300 and its close homolog, CBP, are global transcriptional coactivators that are among the most potent and versatile ATs (reviewed in reference 58). They are known to stimulate transcription of specific Pol II-transcribed genes by interacting with numerous promoter-binding transcription factors that include CREB, p53, nuclear hormone receptors, and oncoprotein-related activators such as c-Fos, c-Jun, and c-Myb. The HAT function of p300/CBP was shown to be required for transcription activation in vivo (29, 39) and in vitro (1, 2, 19, 31, 33). While p300/CBP has also been implicated in the stimulation of Pol I activity (20), no function in Pol III transcription has been reported to date.

Although TFIIIC was found to harbor an intrinsic HAT activity, the previous in vitro study of TFIIIC function in chromatin transcription did not demonstrate a role for this HAT activity in overcoming nucleosomal repression because the assays utilized crude nuclear extracts with undefined factors (34). To define the minimal complement of factors necessary for transcription of human tRNA genes from chromatin templates, we have established a completely defined in vitro transcription system that also tests, for the first time, the function of full-length human Bdp1. In the present study, we identify p300 as a TFIIIC coactivator that displays both HAT-dependent and HAT-independent functions. The p300 HAT activity is indispensable for transcription activation from chromatin templates, whereas a p300-mediated stabilization of the TFIIIC-DNA complex that enhances transcription from histone-free DNA templates does not require the AT activity. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses verify that p300 is targeted to different classes of actively transcribed Pol III genes in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression and purification of recombinant human TFNR.

A full-length human TFNR cDNA was obtained from the Kazusa DNA Research Institute (clone identification no. KIAA1689) and subcloned into baculovirus vector pVL1392 (Pharmingen) for expression in Sf9 insect cells. The vector was modified to add an N-terminal FLAG epitope. Recombinant baculovirus was produced according to the manufacturer's instructions (BaculoGold DNA; Pharmingen). FLAG-TFNR was purified using M2 agarose (Sigma). Briefly, 2.5 × 108 High Five cells (Invitrogen) were infected with recombinant virus for 72 h. Protein lysates were prepared in BC buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 20% glycerol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing 500 mM KCl and 0.1% NP-40 (BC500-0.1% NP-40). Incubation on M2 agarose was for 4 h at 4°C. After washing in BC200-0.1% NP-40, recombinant TFNR was eluted with 0.25 mg/ml FLAG peptide in BC100-0.1% NP-40.

Plasmids and protein expression.

Full-length FLAG-tagged p300 and FLAG-tagged p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) (72) were purified from Sf9 cells using M2 agarose. Histidine-tagged full-length p300 and p300 mutant MutAT2 (32) with six amino acid substitutions within the AT domain were purified from Sf9 cells as described. The FLAG-tagged p300 HAT domain (aa 1195 to 1810) (47) was expressed in Escherichia coli and immunopurified on M2 agarose (18). Five overlapping p300 derivatives encoding residues 1 to 602, 579 to 1161, 1141 to 1631, 1611 to 2047, and 2030 to 2414 were generated by PCR from plasmid p300/pCMV and subcloned into pcDNA 3.1/myc-His (Invitrogen). FLAG-p300 HAT(1195-1810) was subcloned into pcDNA 3.1, followed by removal of the N-terminal FLAG epitope by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene).

Reconstitution of a purified Pol III transcription system.

RNA Pol III was immunopurified from the BN51 cell line that expresses the FLAG-tagged 53-kDa subunit of human Pol III (67). TFIIIC was immunopurified from the Cβ31 cell line that expresses the FLAG-tagged 110-kDa subunit of human TFIIIC2 (34). Both complexes were purified from nuclear extracts through incubation with M2 agarose in BC buffer containing 300 mM KCl and 0.1% NP-40. Nuclear extract was prepared as described previously (9). Bacterially expressed histidine-tagged TBP was purified through sequential Ni-NTA agarose and heparin-Sepharose chromatography (13). PC4 was expressed in bacteria and purified by heparin-Sepharose and P11 column chromatography (37). FLAG-B150 and FLAG-Brf1 (B90) were expressed in insect cells and purified using M2 agarose (60, 65).

Chromatin assembly and chromatin acetylation.

HeLa core histones were purified from HeLa nuclear pellet as described previously (50). FLAG-tagged human DNA topoisomerase I for relaxation of supercoiled DNA was expressed in Sf9 cells and purified using M2 agarose (64). Expression and purification of recombinant ACF and NAP-1 and procedures for chromatin assembly, supercoiling assay, and micrococcal nuclease (MNase) analysis were essentially as described previously (3). Reaction mixtures (70 μl) contained 0.35 μg relaxed plasmid DNA tRNAMet (34) and 0.6 μg core histones. Chromatin acetylation assays were performed as described previously (3). Reaction mixtures contained 650 ng histones (as assembled chromatin), 100 ng TFIIIC, and 20 ng p300.

In vitro transcription assays.

In vitro transcription reactions were conducted with 20 ng of Pol III, 20 ng of TFIIIC, 5 ng of Brf1, 2.5 ng of TBP, 5 ng of TFNR, and 25 ng of PC4. Alternatively, 2 μl HeLa nuclear extract (8 to 10 mg/ml protein) was used. For transcription from naked DNA, reaction mixtures in a final volume of 25 μl contained 40 ng (see Fig. 2B, 3A, and Fig. 3D) or 200 ng (Fig. 3C) of pVA1 template, 60 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 8% glycerol, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 0.6 mM ATP, CTP, and UTP, and 0.025 mM GTP with 2.5 μCi of [α-32P]GTP. Reactions were allowed to proceed for 60 min before addition of 75 μl of stop buffer (0.2 M NaCl, 30 mM EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 150 mg/ml yeast tRNA). Labeled RNA products were extracted with 100 μl phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1), precipitated with ethanol, and resolved on 7% polyacrylamide-7 M urea gels. Products were visualized by autoradiography and quantified with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

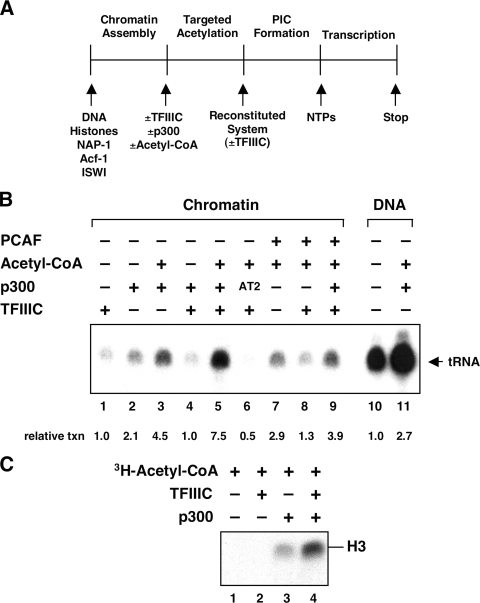

FIG. 2.

Transcription of chromatin templates by Pol III requires targeted acetylation by p300. (A) Schematic representation of the in vitro transcription protocol. PIC, preinitiation complex. (B) Transcription of the tRNAMet gene from chromatin templates and naked DNA. Chromatin templates (40 ng, lanes 1 to 9) were incubated with or without 20 ng of TFIIIC, 20 ng of full-length p300, 10 ng of PCAF, and acetyl-CoA before addition of the reconstituted transcription system. When TFIIIC was added during the preincubation step, it was subsequently omitted from the reconstituted system. When TFIIIC was not included in the preincubation step, it was added along with the reconstituted system. Histone-free template DNA (40 ng, lanes 10 and 11) was preincubated with or without p300 and acetyl-CoA and transcribed under identical conditions. AT2, AT mutant of p300. (C) HAT assay on chromatin templates. Chromatin templates (650 ng of histones) were incubated in the presence of [3H]acetyl-CoA with 100 ng of TFIIIC and 20 ng of p300 as indicated. Labeled histones were resolved by 15% SDS-PAGE and detected by fluorography.

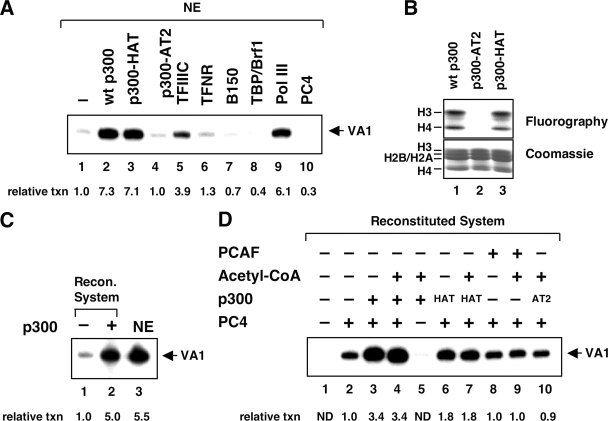

FIG. 3.

Transcription of DNA templates by Pol III is stimulated by p300. (A) Ectopic addition of purified p300 to nuclear extracts stimulates Pol III activity. In vitro transcription of the VA1 gene was performed with 20 μg of nuclear extract supplemented with purified p300 proteins and Pol III factors, as indicated. wt, wild type. (B) Characterization of purified full-length and mutant p300 proteins by HAT assay. Core histones (10 μg) were incubated with 20 ng of the indicated p300 protein in the presence of [3H]acetyl-CoA. The upper and lower panels show fluorography and Coomassie blue staining, respectively. (C) p300 stimulates transcriptional activity of the reconstituted (Recon.) system. Transcription of the VA1 gene was reconstituted with the purified transcription system in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lane 2) of 20 ng of purified full-length p300 or with HeLa nuclear extract (NE; lane 3). (D) Transcriptional stimulation by p300 on naked DNA does not require AT activity. Transcription reaction mixtures with the reconstituted system contained 20 ng of purified wild-type p300, the p300-HAT domain (amino acids 1195 to 1810) or p300 mutant AT2, and 10 ng of PCAF in the absence or presence of acetyl-CoA, as indicated. ND, not determined.

For transcription from chromatin templates, 8 μl reconstituted chromatin template (containing 40 ng DNA) or an equimolar amount of histone-free DNA was incubated with or without purified TFIIIC (20 ng) and/or p300 (20 ng) in assembly buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.6], 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 7 mM KCl, 4.8 mM MgCl2). Acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) (10 μM) was added as indicated. After incubation for 30 min at 30°C, the reconstituted system (Pol III, Brf1, TBP, TFNR, and PC4, with or without TFIIIC) was added to allow preinitiation complex formation for 30 min. Reaction volumes were adjusted to 20 μl with BC100. Finally, 5 μl reaction mixture containing labeled nucleotides and MgCl2 (6 mM final concentration in 25 μl reaction mixture) was added, and the reaction was continued for 30 min at 30°C. Transcription was terminated by addition of 75 μl stop buffer containing 0.5 μl proteinase K (20 mg/ml). Reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37°C before extraction of RNA as described above.

Protein-protein interactions.

For protein-protein interaction assays, approximately 2 μg FLAG-tagged p300 HAT domain was immobilized on M2 agarose (15 μl) and incubated overnight at 4°C with 250 μl of a phosphocellulose (P11)-0.6 M KCl fraction dialyzed against BC100. Beads were washed five times with 1 ml BC200-0.1% NP-40. Bound material was eluted by boiling in SDS sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies against TFIIIC220 (35), TFIIIC102, TFIIIC63 (24), and Pol II subunit RPB1 (Santa Cruz).

To test the interaction between purified TFIIIC complex and full-length p300, FLAG-tagged TFIIIC from 1 ml nuclear extract of cell line Cβ31 was immobilized on M2 agarose and incubated overnight at 4°C with approximately 400 ng of purified histidine-tagged full-length p300. Incubation was in 200 μl BC200-0.1% NP-40 containing 0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA). Beads were washed in BC150-0.1% NP-40, followed by analysis of bound material by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with polyclonal antibodies against p300 (Santa Cruz).

For TFIIIC interactions with p300 fragments, each reaction mixture contained TFIIIC purified from 500 μl nuclear extract from the Cβ31 cell line and 10 μl of the TNT translation reaction mixture. Reactions were carried out in buffer BC200-0.1% NP-40 containing 0.5 mg/ml BSA for 2 h at 4°C. Beads were washed in binding buffer. Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and fluorography.

For analysis of p300 interactions with individual TFIIIC subunits, purified TFIIIC was resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were washed three times for 10 min at room temperature in wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.3], 154 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20), followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with indicated [35S]methionine-labeled p300 fragments in gelatin buffer (wash buffer containing 0.2% [wt/vol] gelatin and 1 mM DTT). Blots were washed four times for 30 min in gelatin buffer and dried, and bound proteins were visualized by fluorography.

EMSA.

For the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), the probe was prepared by end labeling a 120-bp fragment containing the human tRNAMet gene (nucleotide positions −6 to +114) with [α-32P]dATP and Klenow fragment. Reactions contained 100 ng or 20 ng of TFIIIC, 20 ng of p300, 15 ng of TFNR, 6 ng of B150, and 50 ng of PC4 (as indicated) in 25 μl binding buffer [20 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 75 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM EDTA, 4% glycerol, 3 mM DTT, 5 μg bovine serum albumin, and 100 ng poly(dI-dC)]. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at room temperature followed by addition of 15 fmol of labeled probe for 20 min at 30°C. Samples were loaded onto a 4% polyacrylamide gel (37.5:1 acrylamide-bisacrylamide) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA and electrophoresed at 130 V for 2 h at room temperature. The gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film.

Immobilized template assays.

A 1,200-bp biotinylated PCR product containing a single copy of the human tRNAMet gene was amplified from plasmid tRNAMet (34) using a biotinylated 3′ primer positioned ∼920 bp downstream of the TFIIIC binding site (B box). DNA was bound to M280-streptavidin Dynabeads (Dynal) as suggested by the manufacturer. After blocking in BC100 containing 1 mg/ml BSA, beads containing 350 ng of DNA were sequentially incubated with 100 ng of affinity-purified TFIIIC complex and 20 ng of purified p300 for 30 min at room temperature in 60 μl binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 75 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.025% NP-40, 0.2 mg/ml BSA, 3 mM DTT, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The immobilized template was washed in binding buffer containing 100 mM KCl and 0.05% NP-40, and bound material was eluted with SDS sample buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG and anti-p300 antibodies. In order to detect cooperative binding of TFIIIC and p300 to promoter DNA, 30 ng of TFIIIC was coincubated with 20 ng of p300.

ChIP assays.

HeLa S cells were growth arrested by cultivation in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 0.1% fetal bovine serum for 72 h. Resting cells were stimulated to grow by the addition of 20% fetal bovine serum for 21 h. ChIP assays were performed essentially as described in the Upstate Biotechnology protocols using 1 × 106 cells for each antibody. Antibodies directed against p300 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), the 53-kDa subunit of Pol III (RPC53) (67), TFIIIB90 (67), TFIIIC63 (24), PC4 (14), and acetylated histones H3 and H4 (Upstate Biotechnology) were employed. The recovered DNA was analyzed with primers for the human tRNAGln (TRQ1) gene (positions −71 to +139; 5′ primer, 5′-TGACGGGTGTGGAAGACACG-3′; 3′ primer, 5′-AGGAGTATCCCCTCTGTGAAAATC-3′) and the human U6 snRNA promoter (positions −249 to +2; 5′ primer, 5′-GAGGGCCTATTTCCCATGATTC-3′; 3′ primer, 5′-ACGGTGTTTCGTCCTTTCCAC-3′). For control, primers for the p21 promoter region were used (5′ primer, 5′-CCAGCCCTTTGGATGGTTTG-3′; 3′ primer, 5′-GCCTCCTTTCTGTGCCTGAAAC-3′).

RESULTS

Reconstitution of RNA Pol III activity with a completely defined in vitro transcription system.

To identify potential chromatin-modifying factors involved in the regulation of RNA Pol III, we reconstituted transcription of a human tRNA gene with a completely defined in vitro system. The multisubunit Pol III and TFIIIC complexes were affinity purified from cell lines expressing FLAG-tagged subunits. Recombinant TBP and general coactivator PC4 were produced in E. coli, and recombinant TFIIIB subunits Brf1 and Bdp1 were produced in insect cells from baculovirus vectors and affinity purified on M2 agarose. Of the three different splice variants reported for human Bdp1 to date, only two forms, TFIIIB150 (60) and human hB″ (56), have been characterized with respect to transcriptional activity in vitro. No study has examined the activity of the full-length human Bdp1 protein that was originally described as TFNR (27). Since we expected that additional domains in the longer TFNR protein might be functionally important for transcription from chromatin templates, we produced recombinant TFNR in insect cells. FLAG-TFNR was affinity purified on M2 agarose, resulting in one major protein band of 250 kDa after SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining (Fig. 1A, lane 3). An analysis of all purified components is shown in Fig. 1A.

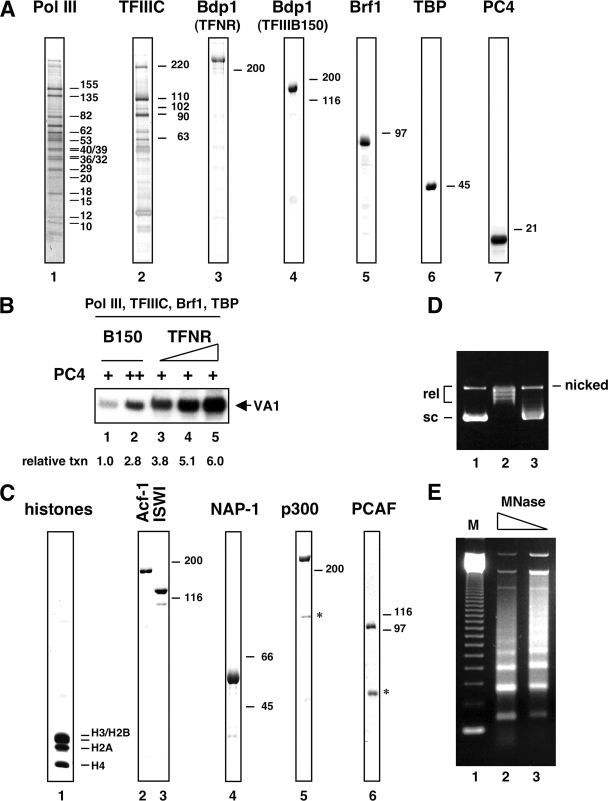

FIG. 1.

Pol III in vitro transcription system for chromatin templates. (A) Analysis of purified Pol III factors by SDS-PAGE. Immunopurified Pol III (lane 1) and TFIIIC (lane 2) were separated by gradient (4 to 20%) SDS-PAGE and visualized by silver staining. Molecular sizes (kDa) of the subunits are indicated to the right. Recombinant TFNR, B150, Brf1, TBP, and PC4 (lanes 3 to 7, indicated on top) were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. Bars on the right indicate protein markers in kDa. (B) Functional characterization of recombinant TFNR (human full-length Bdp1). In vitro transcription of the VA1 gene from DNA templates was reconstituted with 20 ng of Pol III, 20 ng of TFIIIC, 5 ng of Brf1, 2.5 ng of TBP, 25 ng (lanes 1 and 3 to 5) or 150 ng (lane 2) of PC4, and either 3 ng of TFIIIB150 (lanes 1 and 2) or increasing amounts of TFNR (5, 10, and 20 ng, lanes 3 to 5). Transcription data were quantified by PhosphorImager and are expressed as relative transcription (txn). (C) Analysis of purified HeLa core histones, chromatin assembly factors, and coactivators by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Asterisks indicate breakdown products. (D) DNA supercoiling assay. CsCl-purified plasmid tRNAMet (lane 1), topoisomerase I-relaxed DNA used for chromatin assembly (lane 2), and DNA purified from reconstituted chromatin (lane 3) were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. Supercoiled (sc), relaxed (rel), and nicked circular DNAs are indicated. (E) MNase analysis of chromatin assembled with components in panel C. Chromatin was digested with 1 mU MNase (lane 2) or 0.5 mU MNase (lane 3) for 7 min at 27°C and analyzed by 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidum bromide staining. A 123-bp DNA ladder was used as a size marker (M; lane 1).

In an initial experiment, the activity of the purified system was tested on histone-free DNA templates. Figure 1B shows transcription of the VA1 gene using either recombinant TFIIIB150 or recombinant TFNR. At limiting concentrations of PC4 (25 ng, lanes 1 and 3 to 5), the smallest amount of TFNR tested (20 fmol, lane 3) was markedly more active than larger amounts of TFIIIB150 (30 fmol, lane 1). Increasing amounts of TFNR (40 fmol, lane 4, and 80 fmol, lane 5) resulted in little further increase in activity. The lower transcriptional activity of TFIIIB150 could be partially compensated for by an increased amount of PC4 (150 ng, lane 2). Optimal activity of both TFIIIB150 and TFNR depended upon the presence of PC4 (see Fig. 3D for TFNR). Omission of any of the components in the reconstituted system either totally eliminated (in the case of TFNR, TFIIIB150, Brf1, TBP, TFIIIC, or Pol III) or strongly reduced (in the case of PC4) the level of transcription (data not shown). Our data confirm that TFNR is a general Pol III transcription factor and further show that full-length human Bdp1 is more active than its shorter splice variant(s) in vitro. Hence, all subsequent functional studies were carried out with full-length Bdp1.

Pol III transcription from chromatin templates is activated by p300 in an acetyl-CoA-dependent manner.

An earlier study with in vitro reconstituted chromatin templates has shown that addition of purified TFIIIC to HeLa nuclear extracts could partially relieve chromatin-mediated repression of Pol III transcription (34). Because this study utilized crude nuclear extracts with undefined factors, the contribution of such factors to the observed effect was not clear. In the case of Pol II, in vitro transcription from chromatin templates requires recruitment of the HAT p300 (2, 19, 33). Therefore, we explored the possibility that p300 functions as a coactivator on Pol III genes. To this end, a chromatin template was prepared via the recombinant ACF system (26). Chromatin was assembled by incubation of a relaxed 3-kb plasmid containing a single copy of the human initiator methionine tRNA gene with HeLa core histones and recombinant assembly factors Acf-1, ISWI, and NAP1 (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 to 4). A supercoiling assay showed that chromatin assembly was essentially complete (Fig. 1 D), and MNase digestion indicated regular spacing of nucleosomes (Fig. 1E).

The protocol for analyzing transcription of the reconstituted chromatin template by Pol III, general initiation factors (TFIIIC and TFIIIB), and various cofactors (PC4 and p300) is shown in Fig. 2A. When assayed according to this schema, the reconstituted system showed only very marginal activity on the chromatin template (Fig. 2B, lane 1), whereas an equimolar amount of the corresponding DNA template was actively transcribed (Fig. 2B, lane 10). Preincubation with TFIIIC before addition of the remaining factors did not increase transcription, as compared to simultaneous addition of all factors, regardless of whether acetyl-CoA was present or not (not shown). Likewise, increasing the amount of TFIIIC above the concentrations necessary for optimal transcription from DNA did not relieve the chromatin-mediated repression (not shown). However, when the chromatin template was first incubated with TFIIIC plus p300 and acetyl-CoA, strong transcriptional activation was observed (lane 5). This high activity was nearly completely dependent upon the presence of acetyl-CoA (lane 4). In accord with this finding, p300 mutant AT2 with six point mutations within the conserved AT domain (32) and no AT activity (Fig. 3B) was completely unable to stimulate transcription (Fig. 2B, lane 6). (For an alternative interpretation of results with this mutant, see below.) We noted that p300-dependent activation was less efficient when the template was incubated with p300 and acetyl-CoA before TFIIIC was added as part of the transcription machinery (Fig 2B, lane 3), suggesting that under the conditions tested p300 might compete with other Pol III components, notably TFIIIB, for efficient recruitment by TFIIIC. In order to address whether the observed effects were specific for p300, we tested PCAF for its ability to activate Pol III transcription from chromatin templates. When added together with TFIIIC and acetyl-CoA, PCAF showed no activity above that observed with TFIIIC alone (lane 8). Likewise, addition of PCAF along with TFIIIC, p300, and acetyl-CoA resulted in an inhibition of p300-mediated gene activation rather than cooperative stimulation (compare lanes 5 and 9).

Since TFIIIC is the primary DNA-binding factor and has been shown to bind to promoter elements within chromatin templates (34), we analyzed whether p300 might be targeted to the chromatin template by TFIIIC. When we assayed for histone acetylation on the chromatin template, TFIIIC alone did not exhibit detectable HAT activity. Since Kundu et al. (34) showed HAT activity of affinity-purified TFIIIC on free histones, this likely reflects the very weak HAT activity of TFIIIC compared to the more potent activity of HATs like p300. In fact, enhanced acetylation of histone H3 was only evident after preincubation of the template with TFIIIC and p300 (Fig. 2C, lane 4). This indicates that TFIIIC is involved in targeting p300-mediated histone H3 acetylation at the tRNA promoter.

AT-independent functions of p300 on Pol III-transcribed genes.

In control experiments for p300-dependent transcription on chromatin templates, we noticed that p300 also stimulated Pol III activity on a naked DNA template (Fig. 2B, lane 11). No such effect of p300 has been reported for Pol II transcription of DNA templates (2, 19, 23, 33). In order to further examine this observation, we first analyzed transcription of a histone-free DNA template containing the VA1 gene in nuclear extracts and investigated whether addition of recombinant wild-type and mutant p300 proteins could enhance transcriptional activity. As shown in Fig. 3A, full-length p300 led to a 7.3-fold increase in transcription (lane 2). A recombinant p300 fragment containing residues 1195 to 1810, including a functional HAT domain (47) (Fig. 3B, lane 3), was as active as wild-type protein (lane 3). However, p300 mutant AT2, with no HAT activity (Fig. 3B, lane 2), failed to activate transcription. For comparison, addition of exogenous Pol III components to the extract was tested. Only supplementation with additional TFIIIC and Pol III resulted in increased activities (lanes 5 and 9), whereas addition of TFIIIB components or PC4 had no stimulatory effect. These results indicate that TFIIIC and Pol III are the main limiting components in the extract.

Next, we analyzed transcription of a DNA template containing the VA1 gene either in the reconstituted system with or without addition of p300 or in HeLa nuclear extract (Fig. 3C). Addition of p300 to the purified system increased dramatically (fivefold) the activity, reaching a level of transcription comparable to that achieved with nuclear extract. The fact that the p300 effect was observed in the absence of acetyl-CoA suggested that the p300 HAT activity was not required for the observed activity on a DNA template, in apparent contrast to the suggestion from the analysis of the p300 AT2 mutant in nuclear extracts (Fig. 3A, lane 4). Therefore, we systematically assayed for possible effects of acetyl-CoA in the reconstituted system (Fig. 3D). Transcription of the VA1 gene was significantly (3.4-fold) enhanced by full-length p300 (compare lanes 2 and 3), as described above, but this activation did not require and was unaffected by addition of ectopic acetyl-CoA (lanes 3 and 4). Activation of Pol III transcription by p300 was strongly dependent on the presence of PC4 (lane 5), which was also the case for p300-independent basal levels of transcription (lane 1 versus 2). In contrast to the results obtained with nuclear extracts, the p300 fragment comprising the HAT domain was less active than full-length p300 in the reconstituted system. Again, however, this activity was unaffected by addition of acetyl-CoA (lanes 6 and 7). Consistent with the results on chromatin templates and indicative of specificity for p300, PCAF showed no activity (lanes 8 and 9 versus lane 2). Likewise, p300 mutant AT2 was not active when tested with the reconstituted system (lane 10). It is therefore possible that amino acid substitutions in mutant AT2 alter the structure of the protein and compromise functions other than the AT activity. In summary, these results suggest that, beyond its activity as a histone-modifying factor, p300 can enhance Pol III transcription on a DNA template through an AT-independent mechanism.

p300 directly interacts with TFIIIC and stabilizes binding of TFIIIC to the promoter.

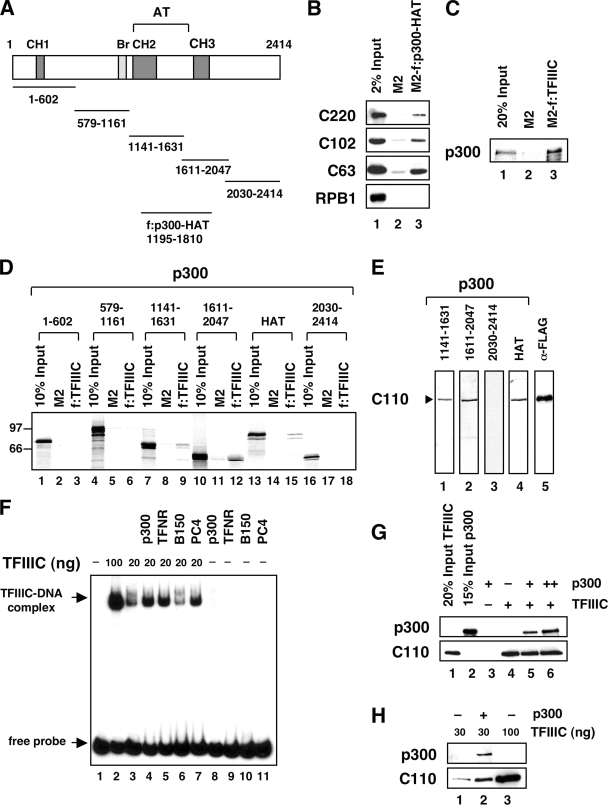

The results of chromatin acetylation assays suggested that p300 is recruited to Pol III-transcribed promoters through promoter-bound TFIIIC and imply a potential interaction between p300 and TFIIIC. To test for a physical interaction between p300 and TFIIIC, a FLAG-p300-HAT fragment (residues 1195 to 1810) (Fig. 4A) was immobilized on M2 agarose and incubated with a HeLa nuclear extract-derived chromatographic fraction (0.6 M KCl, phosphocellulose P11 column) enriched for TFIIIC activity. Analysis by immunoblotting revealed binding of TFIIIC2 (monitored by antibodies to subunits TFIIIC220, TFIIIC102, and TFIIIC63), whereas no binding of Pol II (monitored by antibody to subunit RPB1) was observed (Fig. 4B). To determine whether the interaction between TFIIIC and p300 is direct, affinity-purified TFIIIC was immobilized on M2 agarose and incubated with recombinant full-length p300 that was purified via a histidine tag from insect cells (Fig. 4C). Purified p300 showed strong binding to the purified TFIIIC complex, indicating that the physical interaction between the two factors is direct and not mediated by other proteins. To map TFIIIC-interacting domains in p300 more precisely, the p300 HAT domain and five overlapping p300 fragments that cover the entire protein (Fig. 4A) were labeled with [35S]methionine by in vitro transcription/translation and used in binding assays (Fig. 4D). Consistent with binding of TFIIIC in nuclear extracts to the p300 HAT fragment (Fig. 4B), p300 HAT(1195-1810) and the slightly shorter fragment, p300(1141-1631), showed specific, albeit weak, interactions with the intact affinity-purified TFIIIC complex (Fig. 4D, lanes 9 and 15). However, the strongest binding was observed with the overlapping p300(1611-2047) fragment (lane12), suggesting that residues 1811 to 2047 of p300 are able to enhance the association with purified TFIIIC in vitro. Interaction with p300(1141-1631), p300(1611-2047), and p300 HAT was also confirmed by a blot binding assay following resolution of TFIIIC subunits by SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes (Fig. 4E). Thus, all three positive p300 fragments reacted strongly with the 110-kDa subunit of TFIIIC (lanes 1, 2, and 4). Consistent with results from solution assays, no binding was detected with the C-terminal fragment p300(2030-2414). We conclude that p300 interacts with TFIIIC via a central region that spans its CH2 and CH3 domains and comprises the AT domain.

FIG. 4.

p300 directly interacts with TFIIIC and promotes its binding to the tRNA promoter. (A) Schematic representation of p300 and derived fragments. (B) Binding of TFIIIC to the FLAG-tagged p300 HAT domain (f:p300-HAT). Immobilized FLAG-p300 HAT domain (residues 1195 to 1810) was incubated with a HeLa nuclear extract-derived fraction eluted from a phosphocellulose (P11) column at 0.6 M KCl. Bound TFIIIC subunits (indicated to the left) were analyzed by immunoblotting. RPB1, largest subunit of RNA Pol II. (C) Interaction of purified full-length p300 with immunopurified TFIIIC. FLAG-tagged TFIIIC complex (f:TFIIIC) was immobilized on M2 agarose and incubated with purified histidine-tagged p300. Binding of p300 was scored by anti-p300 immunoblotting. (D) Interaction of in vitro-translated, [35S]methionine-labeled p300 fragments (indicated at the top) with immunopurified TFIIIC complex. (E) Blot binding assay. Purified TFIIIC (containing FLAG-tagged TFIIIC110) was resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Identical membrane stripes were incubated separately with the indicated [35S]methionine-labeled p300 fragments. Bound proteins were visualized by fluorography (lanes 1 to 4). The detected 110-kDa polypeptide was confirmed as TFIIIC110 by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG (α-FLAG) antibodies (lane 5). (F) p300 enhances binding of TFIIIC to the tRNA promoter. Shown are the results of an EMSA with 15 fmol of tRNAMet probe (residues −6 to +114) following incubation with 100 ng (lane 2) and 20 ng (lanes 3 to 7) of purified TFIIIC complex and indicated proteins (20 ng of p300, 15 ng of TFNR, 6 ng of B150, and 50 ng of PC4). (G) TFIIIC recruits p300 to immobilized templates. One hundred nanograms of purified TFIIIC and 20 ng (lanes 3 and 5) or 40 ng (lane 6) of purified full-length p300 were incubated with M280-streptavidin Dynabeads carrying a biotinylated DNA fragment with one copy of the tRNAMet gene. Bound proteins were detected by immunoblotting. Data are shown only for C110 subunit of TFIIIC; consistent results were obtained for TFIIIC subunits C220, C102, and C63 (data not shown). (H) Cooperative binding of TFIIIC and p300 to immobilized templates. Immobilized templates as in panel G were incubated with 100 ng (lane 3) or 30 ng (lanes 1 and 2) of purified TFIIIC complex with or without addition of p300 (20 ng) as indicated. Bound proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Next, employing the human tRNAMet gene as a probe, we performed EMSAs with affinity-purified TFIIIC and recombinant p300 (Fig. 4F). Binding of TFIIIC to the probe resulted in formation of a single DNA-TFIIIC complex (lane 2). When the amount of TFIIIC was reduced fivefold, the signal intensity of the shifted complex decreased accordingly. The addition of full-length p300 to this limiting amount of TFIIIC promoted TFIIIC binding to DNA, as evidenced by the clear increase in signal intensity (compare lanes 3 and 4). Although p300 enhanced binding of TFIIIC to DNA, we failed to detect a change in mobility of the resulting complex. This suggests that the ternary DNA-TFIIIC-p300 complex, unlike the enhanced DNA-TFIIIC complex, is not stable during the electrophoretic resolution. Identical results were obtained with other factors that are known to interact with promoter-bound TFIIIC (see below). Stabilization of the TFIIIC-promoter complex by p300 was not altered by addition of acetyl-CoA (not shown), indicating that the observed effect does not require acetylation by p300. This result strongly supports the conclusion that p300 interacts with TFIIIC in an acetyl-CoA-independent fashion to activate transcription on a naked DNA template. PC4 and the TFNR component of TFIIIB, both described for their roles in stabilizing the binding of TFIIIC2 to the promoter (64, 66), showed the same effect as p300 (lanes 5 and 7). Interestingly, TFIIIB150, which contains only 37% of the residues in TFNR, did not promote binding of TFIIIC to DNA. This result might explain the differences in transcriptional activity between TFNR and TFIIIB150 on DNA templates shown in Fig. 1B. Unlike TFIIIC, none of the proteins tested was able to bind DNA on its own (lanes 8 to 11).

Since the EMSA failed to show a stable ternary DNA-TFIIIC-p300 complex, we employed an immobilized-template assay to obtain further evidence for recruitment of p300 to promoter-bound TFIIIC. A biotinylated template containing a single copy of the tRNAMet gene was immobilized on magnetic beads and incubated sequentially with affinity-purified TFIIIC and purified full-length p300. A clear dose-dependent recruitment of p300 to the template was evident only in the presence of TFIIIC (Fig. 4G, compare lane 3 with lanes 5 and 6). When the template was coincubated with p300 and subsaturating amounts of TFIIIC (30 ng instead of 100 ng), p300 led to a clear increase in binding of TFIIIC to DNA (Fig. 4H). In summary, our results indicate that p300 physically interacts with TFIIIC, resulting in reinforcement of the TFIIIC-promoter complex.

p300 is recruited to Pol III-dependent genes in vivo.

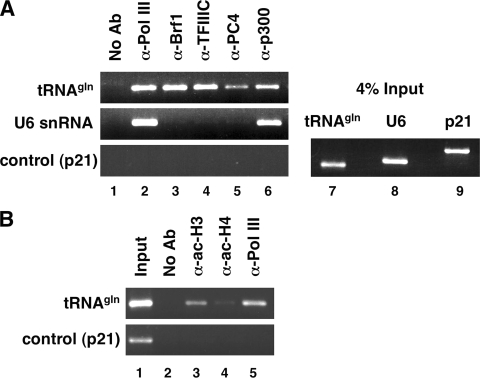

To gain support for the physiological relevance of the in vitro transcription and interaction data, we tested whether p300 is associated with actively transcribed Pol III genes in vivo. When ChIP analysis was performed with exponentially growing HeLa cells, Pol III (monitored by RPC53) was found at promoters of both the tRNAGln gene and the U6 gene (Fig. 5A). As expected (15, 55), Brf1 and TFIIIC2 (TFIIIC63) were detected only at the tRNA promoter, verifying the specificity of the ChIP analysis. Likewise, PC4 was detected on the tRNA gene but not on the U6 gene, suggesting a gene-selective in vivo function on Pol III genes. The finding that PC4 is not recruited to the U6 gene promoter in vivo is in line with previously published data from in vitro studies, in which transcription of the U6 gene was achieved with a purified system devoid of PC4 (25). Strikingly, p300 was detected at the promoters of both the tRNAGlu gene and the U6 gene. As a control, p300 and all Pol III factors tested were absent from the Pol II-transcribed p21 promoter region, which is known to be activated by the tumor suppressor p53 in response to DNA damage (6). Results for the tRNAGln gene were corroborated for other (tRNAMet and tRNALeu) tRNA genes (not shown). Occupancy of p300 at the tRNAGln gene correlated with acetylation of histone H3, whereas acetylation of histone H4 was much less pronounced and almost undetectable under the same experimental conditions (Fig. 5B). We conclude that p300 is associated with actively transcribed Pol III genes in vivo, consistent with its role as a general coactivator for a subset of Pol III-transcribed genes.

FIG. 5.

p300 is targeted to Pol III promoters in vivo. (A) Exponentially growing HeLa cells were subjected to ChIP analysis with specific antibodies (Ab) against the proteins (α-Pol III, α-Brf1, etc.) indicated at the top (left panel, lanes 1 to 6). Promoter occupancy was analyzed by PCR with oligonucleotides for the tRNAGln gene (top), the U6 snRNA gene (middle), and the p21 gene (bottom). Material subjected to ChIP analysis (4% input of reactions in left panel) was analyzed in parallel (right panel, lanes 7 to 9). The sizes of the amplified PCR products are 210 bp for tRNAGln, 251 bp for U6 snRNA, and 420 bp for p21. (B) Chromatin from dividing HeLa cells as in panel A was subjected to ChIP analysis with antibodies against Pol III and acetylated histones H3 and H4.

DISCUSSION

The present study identifies p300 as a coactivator for Pol III with functions in both chromatin remodeling and preinitiation complex assembly. Both functions appear to be mediated by direct interactions of p300 with TFIIIC. Thus, general transcription factor TFIIIC plays a key role in transcription of chromatinized tRNA genes by recruiting the potent and versatile HAT p300, whereas p300 can also stabilize TFIIIC binding to facilitate preinitiation complex assembly on histone-free templates. To our knowledge, this is the first documentation of p300 recruitment by a general transcription initiation factor, and serves as a paradigm for this novel mode of histone-modifying coactivator recruitment. ChIP analyses indicate that p300 is targeted not only to class III promoters with binding sites for TFIIIC, such as tRNA genes, but also to U6 RNA genes that utilize different promoter recognition factors. Thus, the recruitment of p300 appears to be a common mechanism in gene regulation by RNA polymerases II and III.

Targeted histone acetylation by p300 is required for activation of Pol III transcription from chromatin.

Most tRNA genes are constitutively active and highly resistant to repression by histones in vivo, reflecting the dominant effect of transcription factor binding over chromatin assembly (see the introduction). It is well established that highly acetylated histones are linked to gene activation, and incorporation of acetylated histones into 5S gene-containing chromatin was shown to stimulate TFIIIA binding and transcription of the 5S gene (see the introduction). However, HAT-containing coactivators that operate at Pol III genes have not been described. The only known factor that is involved in Pol III transcription and that contains a HAT activity is initiation factor TFIIIC itself, which is able to bind to cognate promoter recognition sites within chromatin templates (34). The present study has employed a completely defined in vitro transcription assay system in conjunction with a chromatin template assembled with recombinant ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling factors and histone chaperones (26). The defined assay system contains affinity-purified Pol III and TFIIIC from human cells, recombinant TFIIIB (containing TBP, Brf1, and Bdp1) and PC4. The advantage of this approach over previous assays with crude extracts is the elimination of possible contributions to transcription of unknown factors.

The first important finding from this study is that binding of TFIIIC to the promoter is not sufficient to overcome nucleosome-mediated repression. This result contrasts with results of previous studies of TFIIIC function in chromatin transcription (34) and indicates that the transcriptional activity observed with crude assay systems was also dependent upon an undefined factor(s) in the extract. In principle, the previously described TFIIIC HAT activity might fulfill such a role, similar to that of the HAT-containing TAFII250 subunit of TFIID in the Pol II transcription complex (40). In both cases, a HAT-containing factor is intimately associated with the primary DNA binding step in preinitiation complex assembly and probably facilitates this process. However, faithful transcription activation still requires the function of additional coactivators. Studies of TAFII250 mutants suggest that the TAFII250 HAT activity is required for transcription at only a subset of promoters (11, 46). However, a direct correlation between TFIIIC HAT activity and transcription activation remains to be shown.

In searching for factors that are able to derepress the tRNA chromatin template, we have found that transcriptional activation and concomitant histone acetylation depend on p300 and acetyl-CoA. Other HATs tested in this study, including PCAF and the nuclear receptor coactivator SRC1 (data not shown), had no effect. Importantly, histone acetylation by p300 was dependent on TFIIIC, indicating that TFIIIC is responsible for recruiting p300 to the promoter. These results demonstrate that targeted histone acetylation is at least part of the underlying mechanism for p300-mediated gene activation of the tRNA gene. The additional observation that the TFIIIB subunit Brf1 is specifically acetylated by p300 in vitro (data not shown) raises the possibility that optimal activation of the chromatin template might also require acetylation of Brf1, although this possibility has not yet been tested.

In relation to the large group of activators that have been shown to interact physically and functionally with p300 at Pol II promoters (16), this is the first example for promoter targeting of p300 by a general transcription initiation factor. The physical basis for the functional interactions between p300 and TFIIIC—involving direct interactions and formation of a stable p300-TFIIIC-promoter complex—is clearly documented by protein-protein interaction, EMSA, and immobilized-template assays (discussed below). Importantly, ChIP analyses showed that, in cells, p300 is targeted to actively transcribed tRNA genes, as well as to U6 RNA genes that do not contain binding sites for TFIIIC. It is possible, therefore, that promoter recognition factor SNAPc/PTF (42, 54, 73) or Oct-1 (55, 59) is involved in recruiting p300 to the U6 gene.

The earlier demonstration that p300-dependent acetylation of histones in ACF-assembled chromatin depends upon ACF (2, 26) makes it likely that ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling (by ACF) is also required in the present study. Studies in yeast indicate that different classes of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes are associated with Pol III genes in vivo. The first documentation came from a genome-wide location study of the yeast RSC complex showing that this SWI/SNF-related remodeling complex is localized to tRNA genes (44). Furthermore, yeast Bdp1 was found to be required for targeting of the chromatin-remodeling complex Isw2 to tRNA genes (4). Thus, the involvement of mammalian chromatin-remodeling complexes in Pol III transcription seems to be likely.

HAT-independent function of p300 at Pol III promoters.

In contrast to the main histone acetylation-related coactivator function for p300 on Pol II (and Pol III)-transcribed genes, p300 was also found to stimulate Pol III transcription through direct stabilization of TFIIIC binding to DNA. This function in preinitiation complex assembly was found to be independent of the AT activity. Similar functions in enhancing TFIIIC binding to the promoter have been reported for coactivators PC4 and DNA topoisomerase I, which were found to enhance and extend interactions of TFIIIC with downstream promoter and terminator sequences and to mediate multiple-round transcription (64). EMSAs presented in this study demonstrate that p300 and PC4 have indistinguishable effects in stabilizing the binding of TFIIIC to DNA. We conclude that p300 is likely involved in two distinct functions at the tRNA promoter: the formation of a stable preinitiation complex and histone modifications leading to an altered chromatin structure.

TFIIIC as a general recruitment factor for p300.

The finding that TFIIIC recruits the potent HAT p300 has important implications not only for the production of tRNAs but also for an understanding how tRNA genes function as barrier elements to restrict the spreading of silenced heterochromatin. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the silenced HMR domain is restricted from spreading by a unique tRNAThr gene (10). A recent study analyzed the effects of specific mutations on the in situ activity of the tRNAThr barrier at HMR (48). Single mutations that affected a HAT or the tRNAThr promoter alone did not result in increased spreading of Sir3 protein, a marker for silenced chromatin. Disruption of the barrier required a combination of two mutations: one in the tRNAThr promoter to eliminate the nucleosome-free gap and a second one in one of the ada2, eaf3, and sas2 genes that encode histone ATs. However, there is no report of these HATs being specifically recruited to tRNA promoters. An active tRNA gene can also act as barrier to restrict spreading of silenced chromatin at the centromere in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyce pombe), although the mechanism of action is not yet known (57).

In contrast to the examples mentioned above, a recent study has shown that clusters of B-box elements at the silent mating locus of S. pombe can prevent spreading of heterochromatin into neighboring euchromatic regions by recruiting TFIIIC without Pol III (45). A genome-wide analysis of the distribution of TFIIIC revealed dispersed loci, throughout euchromatic regions of the genome that contained high levels of TFIIIC in the absence of Pol III. It was suggested that TFIIIC bound to B boxes might play a general role in eukaryotic genomes by restricting the spread of heterochromatin. The conservation of TFIIIC and B boxes implies that the barrier function may extend across species. In support of this notion, the B box of an Alu element that flanks the human keratin 18 gene has also been implicated in barrier function (71). Increasing evidence suggests that the recruitment of factors with HAT activity correlates with barrier activity in multiple organisms (8, 49, 69). Our finding that TFIIIC specifically recruits p300 might represent a key mechanism for the establishment of B-box or tRNA barrier activities. The general paradigm established by these results, recruitment of a histone-modifying coactivator by a general initiation factor, may also be relevant to recent observations of paused RNA polymerases that accumulate on the promoters of inactive genes in the potential absence of corresponding transcriptional activators (reviewed in reference 38).

Reconstitution of complete TFIIIB.

It is noteworthy that the transcription system used in this study contains recombinant human full-length Bdp1 (TFNR) instead of the previously characterized shorter hB″ (56) or TFIIIB150 (60) splice variants. The N-terminal portion of Bdp1 was found to be sufficient to reconstitute in vitro transcription from naked DNA templates (56, 60). However, we found that TFNR was more active than TFIIIB150 in transcription from DNA templates. Furthermore, TFNR, but not TFIIIB150, was able to stabilize binding of TFIIIC to the promoter. The latter result is in line with data from a recent study demonstrating that TFNR and the structurally undefined TFIIIC1 activity are identical (68). These results suggest that TFNR/full-length Bdp1 is likely the most active form of Bdp1 in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zhengxin Wang and Martin Teichmann for Pol III reagents, Annika E. Wallberg for chromatin assembly in initial pilot experiments, Michael Carey and Joshua C. Black for advice with immobilized-template assays, James T. Kadonaga for ACF and p300 MutAT2 baculovirus expression vectors, Yoshihiro Nakatani for p300-HAT domain expression vector and PCAF baculovirus expression vector, and the Kazusa DNA Research Institute for TFNR cDNA.

C.M. was supported by a fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health to R.G.R.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 July 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.An, W., J. Kim, and R. G. Roeder. 2004. Ordered cooperative functions of PRMT1, p300, and CARM1 in transcriptional activation by p53. Cell 117735-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An, W., V. B. Palhan, M. A. Karymov, S. H. Leuba, and R. G. Roeder. 2002. Selective requirements for histone H3 and H4 N termini in p300-dependent transcriptional activation from chromatin. Mol. Cell 9811-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An, W., and R. G. Roeder. 2004. Reconstitution and transcriptional analysis of chromatin in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 377460-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachman, N., M. E. Gelbart, T. Tsukiyama, and J. D. Boeke. 2005. TFIIIB subunit Bdp1p is required for periodic integration of the Ty1 retrotransposon and targeting of Isw2p to S. cerevisiae tDNAs. Genes Dev. 19955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogenhagen, D. F., W. M. Wormington, and D. D. Brown. 1982. Stable transcription complexes of Xenopus 5S RNA genes: a means to maintain the differentiated state. Cell 28413-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunz, F., A. Dutriaux, C. Lengauer, T. Waldman, S. Zhou, J. P. Brown, J. M. Sedivy, K. W. Kinzler, and B. Vogelstein. 1998. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science 2821497-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnol, A. F., F. Margottin, J. Huet, G. Almouzni, M. N. Prioleau, M. Mechali, and A. Sentenac. 1993. TFIIIC relieves repression of U6 snRNA transcription by chromatin. Nature 362475-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu, Y. H., Q. Yu, J. J. Sandmeier, and X. Bi. 2003. A targeted histone acetyltransferase can create a sizable region of hyperacetylated chromatin and counteract the propagation of transcriptionally silent chromatin. Genetics 165115-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dignam, J. D., R. M. Lebovitz, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 111475-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donze, D., and R. T. Kamakaka. 2001. RNA polymerase III and RNA polymerase II promoter complexes are heterochromatin barriers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 20520-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Dumay-Odelot, H., C. Marck, S. Durrieu-Gaillard, O. Lefebvre, S. Jourdain, M. Prochazkova, A. Pflieger, and M. Teichmann. 2007. Identification, molecular cloning, and characterization of the sixth subunit of human transcription factor TFIIIC. J. Biol. Chem. 28217179-17189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunphy, E. L., T. Johnson, S. S. Auerbach, and E. H. Wang. 2000. Requirement for TAFII250 acetyltransferase activity in cell cycle progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 201134-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felts, S. J., P. A. Weil, and R. Chalkley. 1990. Transcription factor requirements for in vitro formation of transcriptionally competent 5S rRNA gene chromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 102390-2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge, H., E. Martinez, C. M. Chiang, and R. G. Roeder. 1996. Activator-dependent transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II: in vitro reconstitution with general transcription factors and cofactors. Methods Enzymol. 27457-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge, H., and R. G. Roeder. 1994. Purification, cloning, and characterization of a human coactivator, PC4, that mediates transcriptional activation of class II genes. Cell 78513-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geiduschek, E. P., and G. A. Kassavetis. 2001. The RNA polymerase III transcription apparatus. J. Mol. Biol. 3101-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman, R. H., and S. Smolik. 2000. CBP/p300 in cell growth, transformation, and development. Genes Dev. 141553-1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gottesfeld, J., and L. S. Bloomer. 1982. Assembly of transcriptionally active 5S RNA gene chromatin in vitro. Cell 28781-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu, W., and R. G. Roeder. 1997. Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell 90595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guermah, M., V. B. Palhan, A. J. Tackett, B. T. Chait, and R. G. Roeder. 2006. Synergistic functions of SII and p300 in productive activator-dependent transcription of chromatin templates. Cell 125275-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschler-Laszkiewicz, I., A. Cavanaugh, Q. Hu, J. Catania, M. L. Avantaggiati, and L. I. Rothblum. 2001. The role of acetylation in rDNA transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 294114-4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howe, L., and J. Ausió. 1998. Nucleosome translational position, not histone acetylation, determines TFIIIA binding to nucleosomal Xenopus laevis 5S rRNA genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 181156-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howe, L., T. A. Ranalli, C. D. Allis, and J. Ausio. 1998. Transcriptionally active Xenopus laevis somatic 5 S ribosomal RNA genes are packaged with hyperacetylated histone H4, whereas transcriptionally silent oocyte genes are not. J. Biol. Chem. 27320693-20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh, Y.-J., T. K. Kundu, Z. Wang, R. Kovelman, and R. G. Roeder. 1999. The TFIIIC90 subunit of TFIIIC interacts with multiple components of the RNA polymerase III machinery and contains a histone-specific acetyltransferase activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 197697-7704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsieh, Y.-J., Z. Wang, R. Kovelman, and R. G. Roeder. 1999. Cloning and characterization of two evolutionarily conserved subunits (TFIIIC102 and TFIIIC63) of human TFIIIC and their involvement in functional interactions with TFIIIB and RNA polymerase III. Mol. Cell. Biol. 194944-4952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu, P., S. Wu, and N. Hernandez. 2003. A minimal RNA polymerase III transcription system from human cells reveals positive and negative regulatory roles for CK2. Mol. Cell 12699-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito, T., M. E. Levenstein, D. V. Fyodorov, A. K. Kutach, R. Kobayashi, and J. T. Kadonaga. 1999. ACF consists of two subunits, Acf1 and ISWI, that function cooperatively in the ATP-dependent catalysis of chromatin assembly. Genes Dev. 131529-1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelter, A. R., J. Herchenbach, and B. Wirth. 2000. The transcription factor-like nuclear regulator (TFNR) contains a novel 55-amino-acid motif repeated nine times and maps closely to SMN1. Genomics 70315-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornberg, R. D., and Y. Lorch. 1999. Twenty-five years of the nucleosome, fundamental particle of the eukaryote chromosome. Cell 98285-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korzus, E., J. Torchia, D. W. Rose, L. Xu, R. Kurokawa, E. M. McInerney, T. M. Mullen, C. K. Glass, and M. G. Rosenfeld. 1998. Transcription factor-specific requirements for coactivators and their acetyltransferase functions. Science 279703-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovelman, R., and R. G. Roeder. 1992. Purification and characterization of two forms of human transcription factor IIIC. J. Biol. Chem. 26724446-24456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraus, W. L., and J. T. Kadonaga. 1998. p300 and estrogen receptor cooperatively activate transcription via differential enhancement of initiation and reinitiation. Genes Dev. 12331-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraus, W. L., E. T. Manning, and J. T. Kadonaga. 1999. Biochemical analysis of distinct activation functions in p300 that enhance transcription initiation with chromatin templates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 198123-8135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kundu, T. K., V. B. Palhan, Z. Wang, W. An, P. A. Cole, and R. G. Roeder. 2000. Activator-dependent transcription from chromatin in vitro involving targeted histone acetylation by p300. Mol. Cell 6551-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kundu, T. K., Z. Wang, and R. G. Roeder. 1999. Human TFIIIC relieves chromatin-mediated repression of RNA polymerase III transcription and contains an intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 191605-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lagna, G., R. Kovelman, J. Sukegawa, and R. G. Roeder. 1994. Cloning and characterization of an evolutionarily divergent DNA-binding subunit of mammalian TFIIIC. Mol. Cell. Biol. 143053-3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, D. Y., J. J. Hayes, D. Pruss, and A. P. Wolffe. 1993. A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosomal DNA. Cell 7273-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malik, S., and R. G. Roeder. 2003. Isolation and functional characterization of the TRAP/mediator complex. Methods Enzymol. 364257-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Margaritis, T., and F. C. Holstege. 2008. Poised RNA polymerase II gives pause for thought. Cell 133581-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez-Balbas, M. A., A. J. Bannister, K. Martin, P. Haus-Seuffert, M. Meisterernst, and T. Kouzarides. 1998. The acetyltransferase activity of CBP stimulates transcription. EMBO J. 172886-2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mizzen, C. A., X. J. Yang, T. Kokubo, J. E. Brownell, A. J. Bannister, T. Owen-Hughes, J. Workman, L. Wang, S. L. Berger, T. Kouzarides, Y. Nakatani, and C. D. Allis. 1996. The TAFII250 subunit of TFIID has histone acetyltransferase activity. Cell 871261-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morse, R. H., S. Y. Roth, and R. T. Simpson. 1992. A transcriptionally active tRNA gene interferes with nucleosome positioning in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 124015-4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murphy, S., J.-B. Yoon, T. Gerster, and R. G. Roeder. 1992. Oct-1 and Oct-2 potentiate functional interactions of a transcription factor with the proximal sequence element of small nuclear RNA genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 123247-3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neely, K. E., and J. L. Workman. 2002. The complexity of chromatin remodeling and its links to cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 160319-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng, H. H., F. Robert, R. A. Young, and K. Struhl. 2002. Genome-wide location and regulated recruitment of the RSC nucleosome-remodeling complex. Genes Dev. 16806-819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noma, K., H. P. Cam, R. J. Maraia, and S. I. Grewal. 2006. A role for TFIIIC transcription factor complex in genome organization. Cell 125859-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Brien, T., and R. Tjian. 2000. Different functional domains of TAFII250 modulate expression of distinct subsets of mammalian genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 972456-2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogryzko, V. V., R. L. Schiltz, V. Russanova, B. H. Howard, and Y. Nakatani. 1996. The transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP are histone acetyltransferases. Cell 87953-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oki, M., and R. T. Kamakaka. 2005. Barrier function at HMR. Mol. Cell 19707-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oki, M., L. Valenzuela, T. Chiba, T. Ito, and R. T. Kamakaka. 2004. Barrier proteins remodel and modify chromatin to restrict silenced domains. Mol. Cell. Biol. 241956-1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Owen-Hughes, T., R. T. Utley, D. J. Steger, J. M. West, S. John, J. Cote, K. M. Havas, and J. L. Workman. 1999. Analysis of nucleosome disruption by ATP-driven chromatin remodeling complexes. Methods Mol. Biol. 119319-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panetta, G., M. Buttinelli, A. Flaus, T. J. Richmond, and D. Rhodes. 1998. Differential nucleosome positioning on Xenopus oocyte and somatic 5 S RNA genes determines both TFIIIA and H1 binding: a mechanism for selective H1 repression. J. Mol. Biol. 282683-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paule, M. R., and R. J. White. 2000. Survey and summary: transcription by RNA polymerases I and III. Nucleic Acids Res. 281283-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Roeder, R. G. 1998. Role of general and gene-specific cofactors in the regulation of eukaryotic transcription. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 63201-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sadowski, C. L., R. W. Henry, S. M. Lobo, and N. Hernandez. 1993. Targeting TBP to a non-TATA box cis-regulatory element: a TBP-containing complex activates transcription from snRNA promoters through the PSE. Genes Dev. 71535-1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schramm, L., and N. Hernandez. 2002. Recruitment of RNA polymerase III to its target promoters. Genes Dev. 162593-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schramm, L., P. S. Pendergrast, Y. Sun, and N. Hernandez. 2000. Different human TFIIIB activities direct RNA polymerase III transcription from TATA-containing and TATA-less promoters. Genes Dev. 142650-2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scott, K. C., S. L. Merrett, and H. F. Willard. 2006. A heterochromatin barrier partitions the fission yeast centromere into discrete chromatin domains. Curr. Biol. 16119-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sterner, D. E., and S. L. Berger. 2000. Acetylation of histones and transcription-related factors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64435-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sturm, R. A., G. Das, and W. Herr. 1988. The ubiquitous octamer-binding protein Oct-1 contains a POU domain with a homeo box subdomain. Genes Dev. 21582-1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teichmann, M., Z. Wang, and R. G. Roeder. 2000. A stable complex of a novel transcription factor IIB-related factor, human TFIIIB50, and associated proteins mediate selective transcription by RNA polymerase III of genes with upstream promoter elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9714200-14205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tremethick, D., K. Zucker, and A. Worcel. 1990. The transcription complex of the 5 S RNA gene, but not transcription factor IIIA alone, prevents nucleosomal repression of transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2655014-5023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tse, C., T. Sera, A. P. Wolffe, and J. C. Hansen. 1998. Disruption of higher-order folding by core histone acetylation dramatically enhances transcription of nucleosomal arrays by RNA polymerase III. Mol. Cell. Biol. 184629-4638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vaquero, A., A. Loyola, and D. Reinberg. 2003. The constantly changing face of chromatin. Sci. Aging Knowledge Environ. 2003RE4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang, Z., and R. G. Roeder. 1998. DNA topoisomerase I and PC4 can interact with human TFIIIC to promote both accurate termination and transcription reinitiation by RNA polymerase III. Mol. Cell 1749-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang, Z., and R. G. Roeder. 1995. Structure and function of a human transcription factor TFIIIB subunit that is evolutionarily conserved and contains both TFIIB- and high-mobility-group protein 2-related domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 927026-7030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang, Z., and R. G. Roeder. 1996. TFIIIC1 acts through a downstream region to stabilize TFIIIC2 binding to RNA polymerase III promoters. Mol. Cell. Biol. 166841-6850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang, Z., and R. G. Roeder. 1997. Three human RNA polymerase III-specific subunits form a subcomplex with a selective function in specific transcription initiation. Genes Dev. 111315-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weser, S., C. Gruber, H. M. Hafner, M. Teichmann, R. G. Roeder, K. H. Seifart, and W. Meissner. 2004. Transcription factor (TF)-like nuclear regulator, the 250-kDa form of Homo sapiens TFIIIB″, is an essential component of human TFIIIC1 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 27927022-27029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.West, A. G., S. Huang, M. Gaszner, M. D. Litt, and G. Felsenfeld. 2004. Recruitment of histone modifications by USF proteins at a vertebrate barrier element. Mol. Cell 16453-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Willis, I. M. 2002. A universal nomenclature for subunits of the RNA polymerase III transcription initiation factor TFIIIB. Genes Dev. 161337-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Willoughby, D. A., A. Vilalta, and R. G. Oshima. 2000. An Alu element from the K18 gene confers position-independent expression in transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 275759-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang, X. J., V. V. Ogryzko, J. Nishikawa, B. H. Howard, and Y. Nakatani. 1996. A p300/CBP-associated factor that competes with the adenoviral oncoprotein E1A. Nature 382319-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoon, J.-B., S. Murphy, L. Bai, Z. Wang, and R. G. Roeder. 1995. Proximal sequence element-binding transcription factor (PTF) is a multisubunit complex required for transcription of both RNA polymerase II- and RNA polymerase III-dependent small nuclear RNA genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 152019-2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yoshinaga, S. K., P. A. Boulanger, and A. J. Berk. 1987. Resolution of human transcription factor TFIIIC into two functional components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 843585-3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yoshinaga, S. K., N. D. L'Etoile, and A. J. Berk. 1989. Purification and characterization of transcription factor IIIC2. J. Biol. Chem. 26410726-10731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]