Abstract

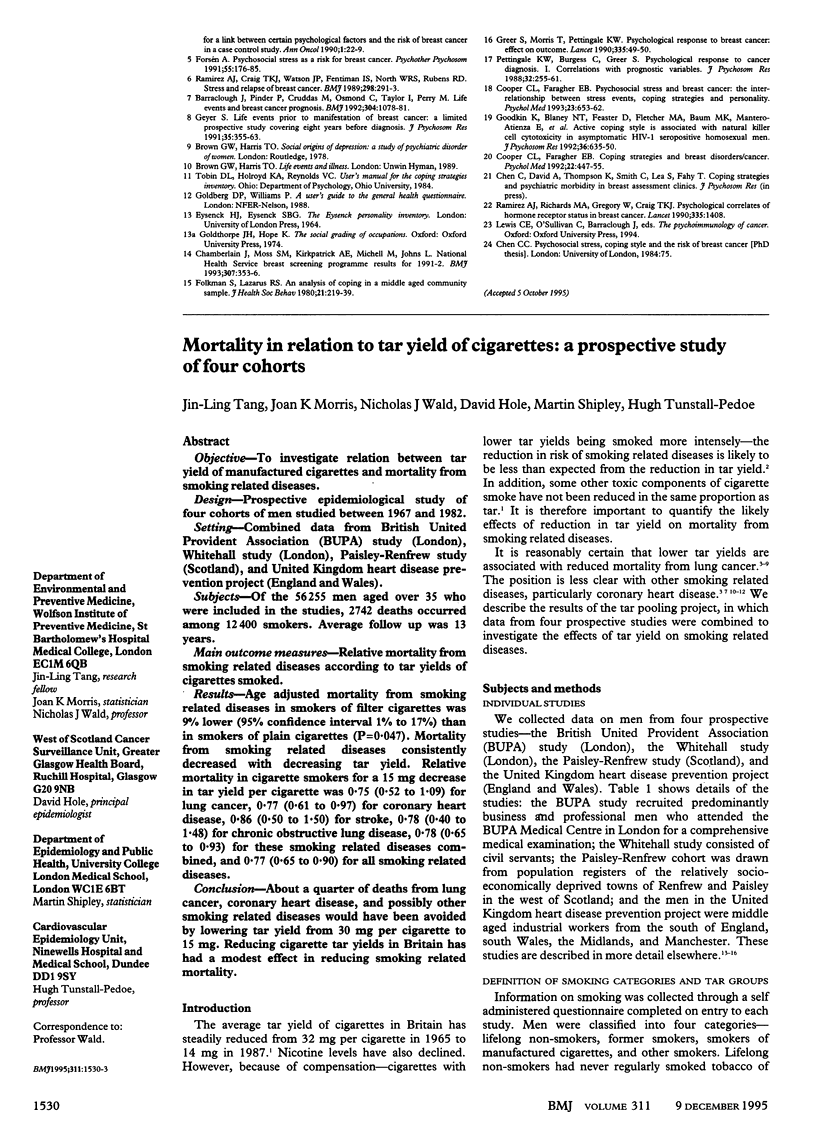

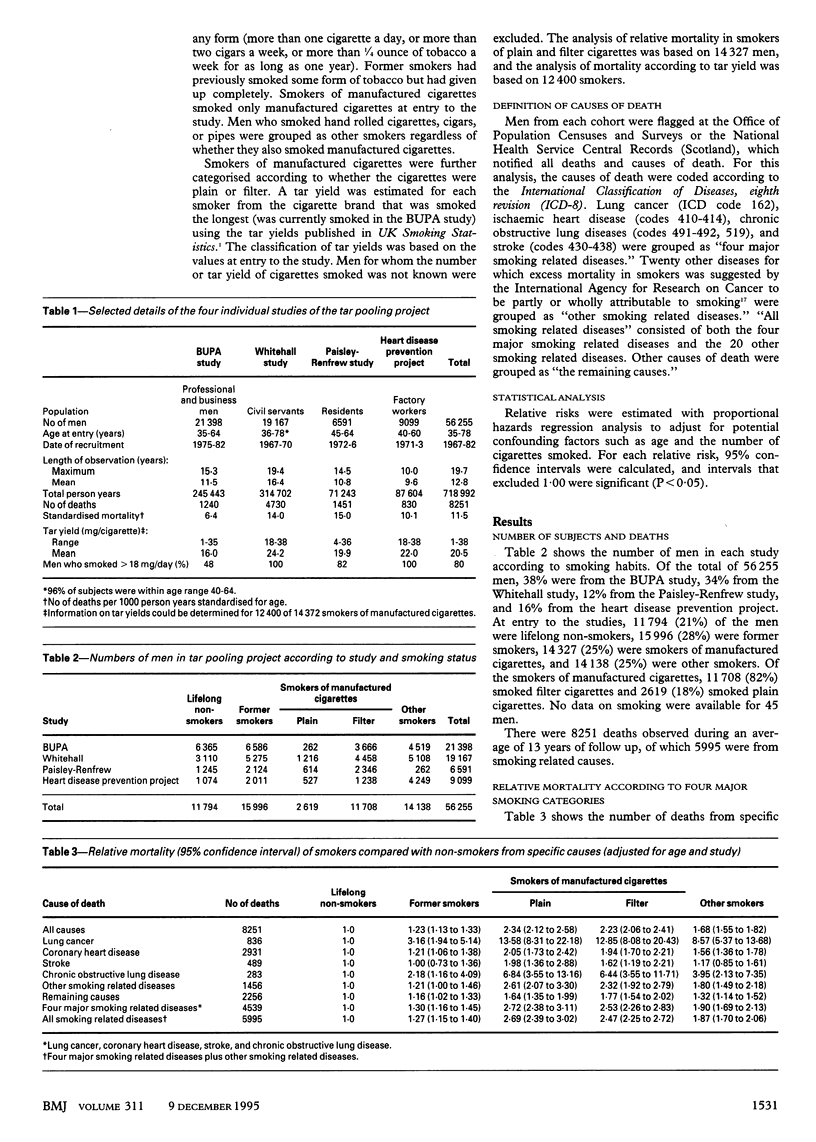

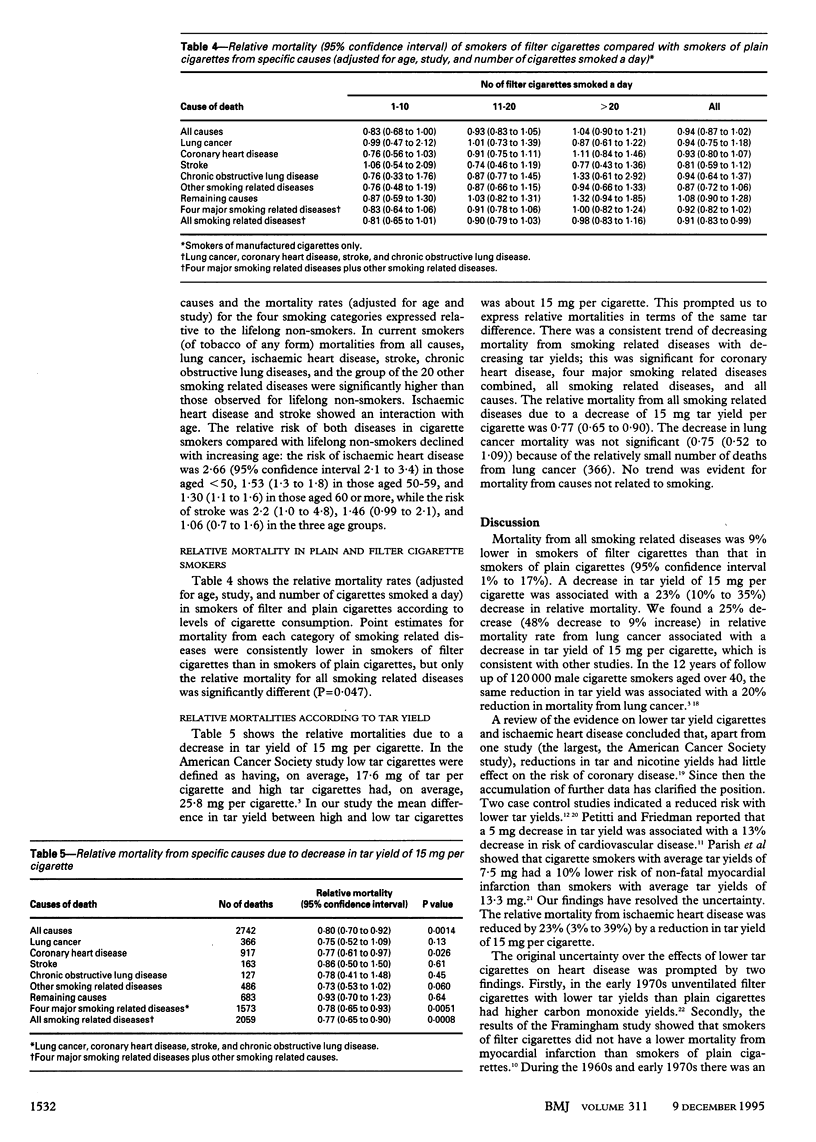

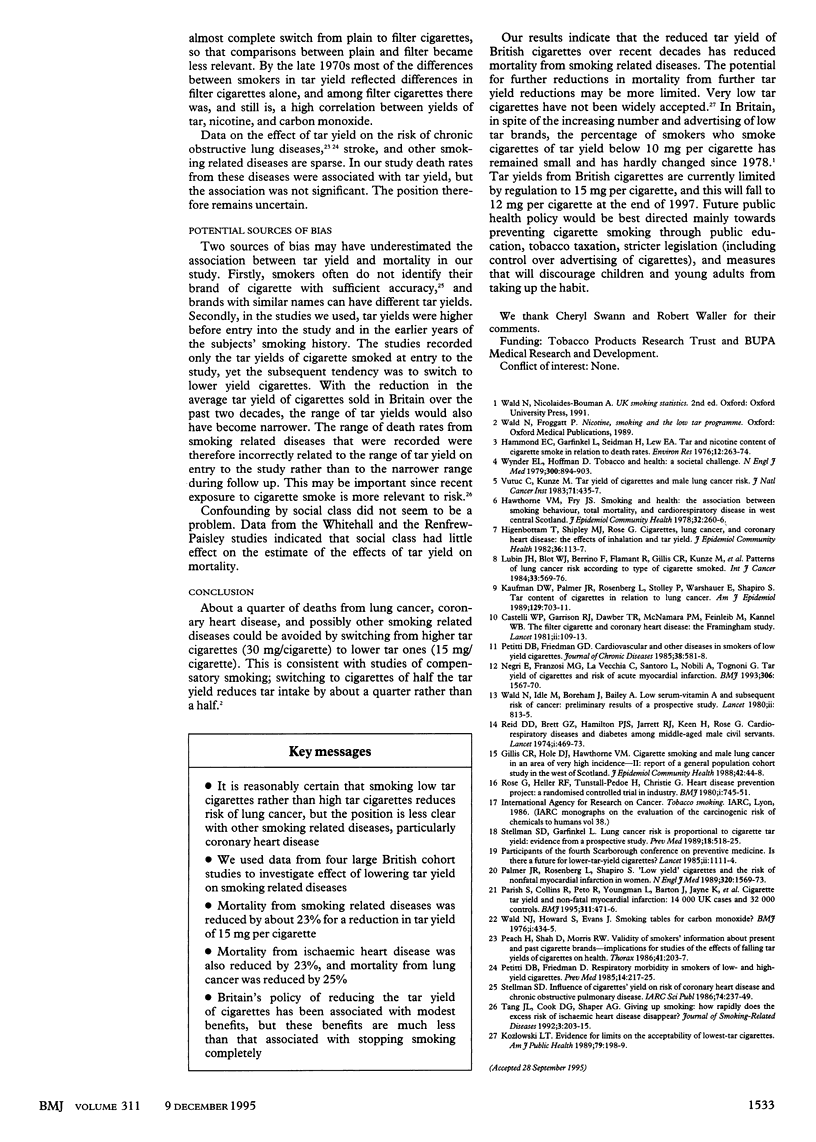

OBJECTIVE--To investigate relation between tar yield of manufactured cigarettes and mortality from smoking related diseases. DESIGN--Prospective epidemiological study of four cohorts of men studied between 1967 and 1982. SETTING--Combined data from British United Provident Association (BUPA) study (London), Whitehall study (London), Paisley-Renfrew study (Scotland), and United Kingdom heart disease prevention project (England and Wales). SUBJECTS--Of the 56,255 men aged over 35 who were included in the studies, 2742 deaths occurred among 12,400 smokers. Average follow up was 13 years. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Relative mortality from smoking related diseases according to tar yields of cigarettes smoked. RESULTS--Age adjusted mortality from smoking related diseases in smokers of filter cigarettes was 9% lower (95% confidence interval 1% to 17%) than in smokers related diseases consistently decreased with decreasing tar yield. Relative mortality in cigarette smokers for a 15 mg decrease in tar yield per cigarette was 0.75 (0.52 to 1.09) for lung cancer, 0.77 (0.61 to 0.97) for coronary heart disease, 0.86 (0.50 to 1.50) for stroke, 0.78 (0.40 to 1.48) for chronic obstructive lung diseases, 0.78 (0.65 to 0.93) for these smoking related diseases combined, and 0.77 (0.65 to 0.90) for all smoking related diseases. CONCLUSION--About a quarter of deaths from lung cancer, coronary heart disease, and possibly other smoking related diseases would have been avoided by lowering tar yield from 30 mg per cigarette to 15 mg. Reducing cigarette tar yields in Britain has had a modest effect in reducing smoking related mortality.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Castelli W. P., Garrison R. J., Dawber T. R., McNamara P. M., Feinleib M., Kannel W. B. The filter cigarette and coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. Lancet. 1981 Jul 18;2(8238):109–113. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis C. R., Hole D. J., Hawthorne V. M. Cigarette smoking and male lung cancer in an area of very high incidence. II. Report of a general population cohort study in the West of Scotland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1988 Mar;42(1):44–48. doi: 10.1136/jech.42.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond E. C., Garfinkel L., Seidman H., Lew E. A. "Tar" and nicotine content of cigarette smoke in relation to death rates. Environ Res. 1976 Dec;12(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(76)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne V. M., Fry J. S. Smoking and health: the association between smoking behaviour, total mortality, and cardiorespiratory disease in west central Scotland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978 Dec;32(4):260–266. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.4.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman D. W., Palmer J. R., Rosenberg L., Stolley P., Warshauer E., Shapiro S. Tar content of cigarettes in relation to lung cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1989 Apr;129(4):703–711. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski L. T. Evidence for limits on the acceptability of lowest-tar cigarettes. Am J Public Health. 1989 Feb;79(2):198–199. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubin J. H., Blot W. J., Berrino F., Flamant R., Gillis C. R., Kunze M., Schmahl D., Visco G. Patterns of lung cancer risk according to type of cigarette smoked. Int J Cancer. 1984 May 15;33(5):569–576. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910330504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri E., Franzosi M. G., La Vecchia C., Santoro L., Nobili A., Tognoni G. Tar yield of cigarettes and risk of acute myocardial infarction. GISSI-EFRIM Investigators. BMJ. 1993 Jun 12;306(6892):1567–1570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6892.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer J. R., Rosenberg L., Shapiro S. "Low yield" cigarettes and the risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction in women. N Engl J Med. 1989 Jun 15;320(24):1569–1573. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906153202401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish S., Collins R., Peto R., Youngman L., Barton J., Jayne K., Clarke R., Appleby P., Lyon V., Cederholm-Williams S. Cigarette smoking, tar yields, and non-fatal myocardial infarction: 14,000 cases and 32,000 controls in the United Kingdom. The International Studies of Infarct Survival (ISIS) Collaborators. BMJ. 1995 Aug 19;311(7003):471–477. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7003.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peach H., Shah D., Morris R. W. Validity of smokers' information about present and past cigarette brands--implications for studies of the effects of falling tar yields of cigarettes on health. Thorax. 1986 Mar;41(3):203–207. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.3.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitti D. B., Friedman G. D. Cardiovascular and other diseases in smokers of low yield cigarettes. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(7):581–588. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitti D. B., Friedman G. D. Respiratory morbidity in smokers of low- and high-yield cigarettes. Prev Med. 1985 Mar;14(2):217–225. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(85)90037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. D., Brett G. Z., Hamilton P. J., Jarrett R. J., Keen H., Rose G. Cardiorespiratory disease and diabetes among middle-aged male Civil Servants. A study of screening and intervention. Lancet. 1974 Mar 23;1(7856):469–473. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92783-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose F. L., Bergel F. Retroperitoneal fibrosis associated with atenolol. Br Med J. 1980 Sep 13;281(6242):745–745. doi: 10.1136/bmj.281.6242.745-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shun-Zhang Y., Miller A. B., Sherman G. J. Optimising the age, number of tests, and test interval for cervical screening in Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1982 Mar;36(1):1–10. doi: 10.1136/jech.36.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellman S. D., Garfinkel L. Lung cancer risk is proportional to cigarette tar yield: evidence from a prospective study. Prev Med. 1989 Jul;18(4):518–525. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(89)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellman S. D. Influence of cigarette yield on risk of coronary heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. IARC Sci Publ. 1986;(74):237–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vutuc C., Kunze M. Tar yields of cigarettes and male lung cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983 Sep;71(3):435–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald N. J., Howard S., Evans J. Smoking tables for carbon monoxide? Br Med J. 1976 Feb 21;1(6007):434–435. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6007.434-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald N., Idle M., Boreham J., Bailey A. Low serum-vitamin-A and subsequent risk of cancer. Preliminary results of a prospective study. Lancet. 1980 Oct 18;2(8199):813–815. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynder E. L., Hoffmann D. Tobacco and health: a societal challenge. N Engl J Med. 1979 Apr 19;300(16):894–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197904193001605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]