Abstract

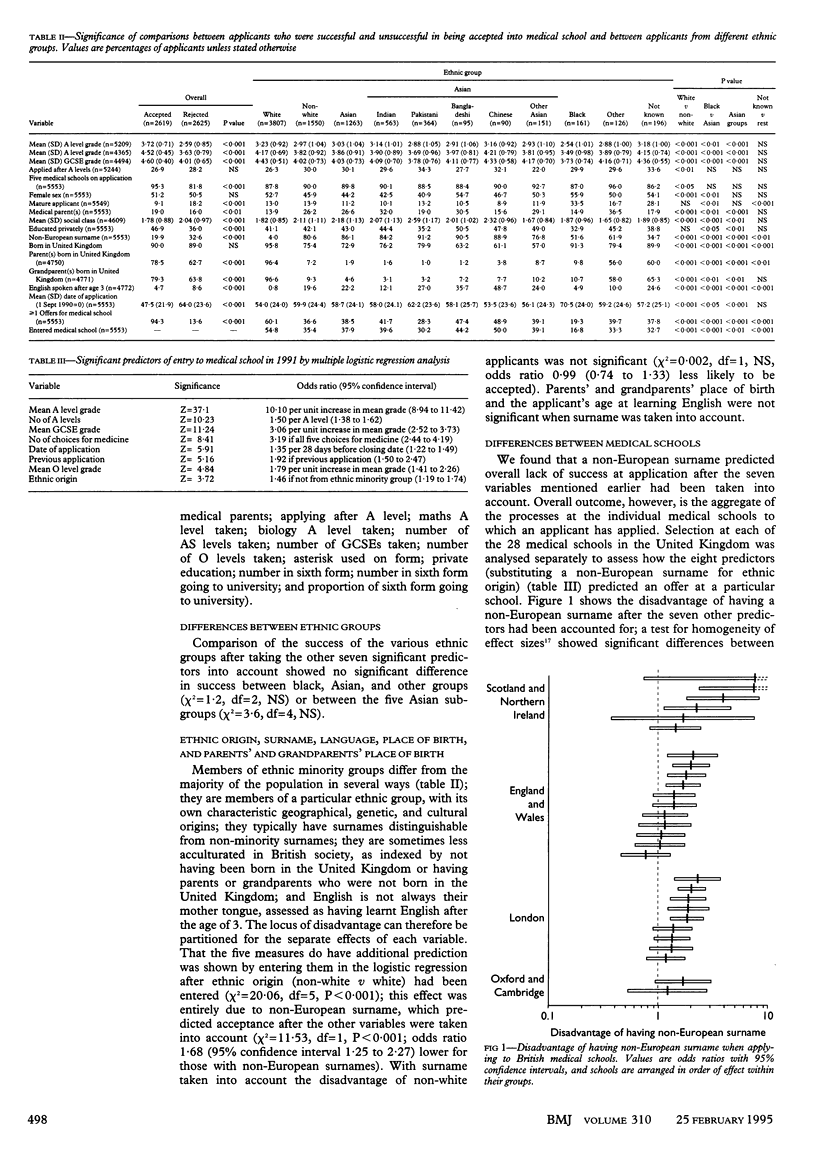

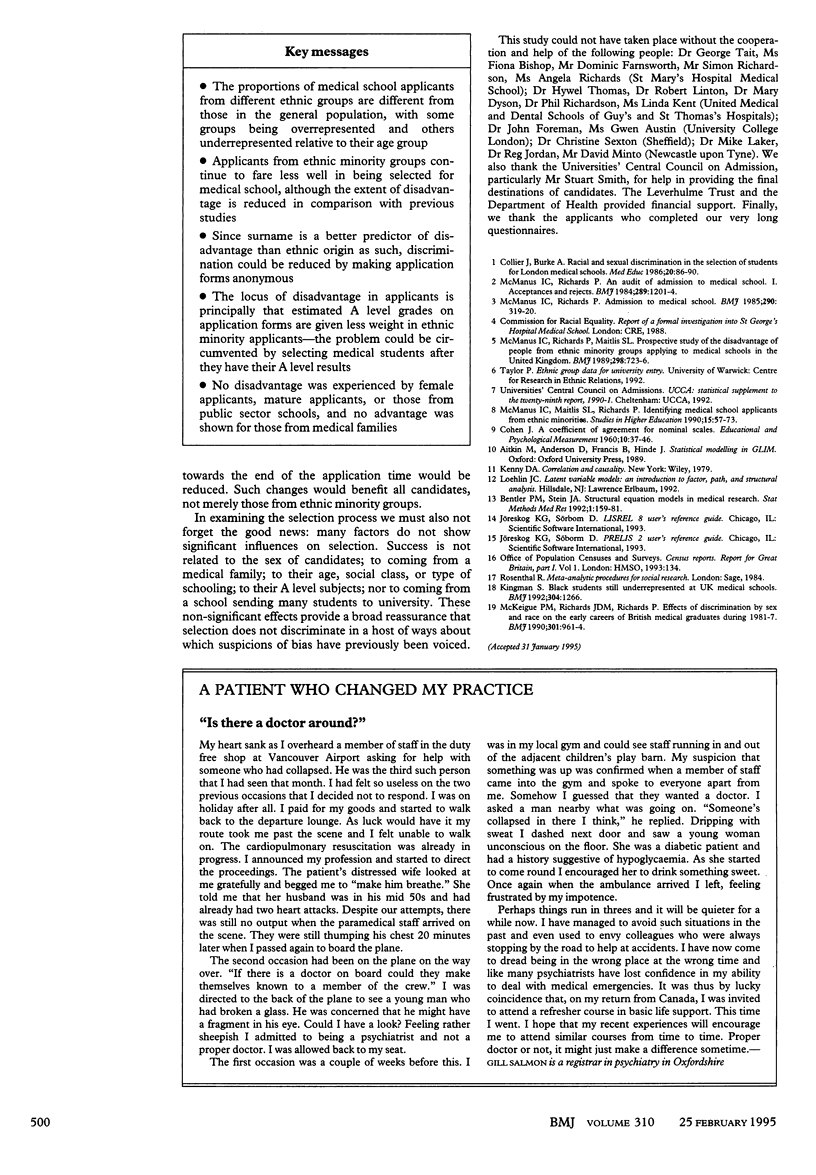

OBJECTIVE--To assess whether people from ethnic minority groups are less likely to be accepted at British medical schools, and to explore the mechanisms of disadvantage. DESIGN--Prospective study of a national cohort of medical school applicants. SETTING--All 28 medical schools in the United Kingdom. SUBJECTS--6901 subjects who had applied through the Universities' Central Council on Admissions in 1990 to study medicine. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Offers and acceptance at medical school by ethnic group. RESULTS--Applicants from ethnic minority groups constituted 26.3% of those applying to medical school. They were less likely to be accepted, partly because they were less well qualified and applied later. Nevertheless, taking educational and some other predictors into account, applicants from ethnic minority groups were 1.46 times (95% confidence interval 1.19 to 1.74) less likely to be accepted. Having a European surname predicted acceptance better than ethnic origin itself, implying direct discrimination rather than disadvantage secondary to other possible differences between white and non-white applicants. Applicants from ethnic minority groups fared significantly less well in 12 of the 28 British medical schools. Analysis of the selection process suggests that medical schools make fewer offers to such applicants than to others with equivalent estimated A level grades. CONCLUSIONS--People from ethnic minority groups applying to medical school are disadvantaged, principally because ethnic origin is assessed from a candidate's surname; the disadvantage has diminished since 1986. For subjects applying before A level the mechanism is that less credit is given to referees' estimates of A level grades. Selection would be fairer if (a) application forms were anonymous; (b) forms did not include estimates of A level grades; and (c) selection took place after A level results are known.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bentler P. M., Stein J. A. Structural equation models in medical research. Stat Methods Med Res. 1992;1(2):159–181. doi: 10.1177/096228029200100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier J., Burke A. Racial and sexual discrimination in the selection of students for London medical schools. Med Educ. 1986 Mar;20(2):86–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1986.tb01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeigue P. M., Richards J. D., Richards P. Effects of discrimination by sex and race on the early careers of British medical graduates during 1981-7. BMJ. 1990 Oct 27;301(6758):961–964. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6758.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus I. C., Richards P. Admission to medical school. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1985 Jan 26;290(6464):319–320. doi: 10.1136/bmj.290.6464.319-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus I. C., Richards P. Audit of admission to medical school: I--Acceptances and rejects. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Nov 3;289(6453):1201–1204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6453.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus I. C., Richards P., Maitlis S. L. Prospective study of the disadvantage of people from ethnic minority groups applying to medical schools in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 1989 Mar 18;298(6675):723–726. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6675.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]