Abstract

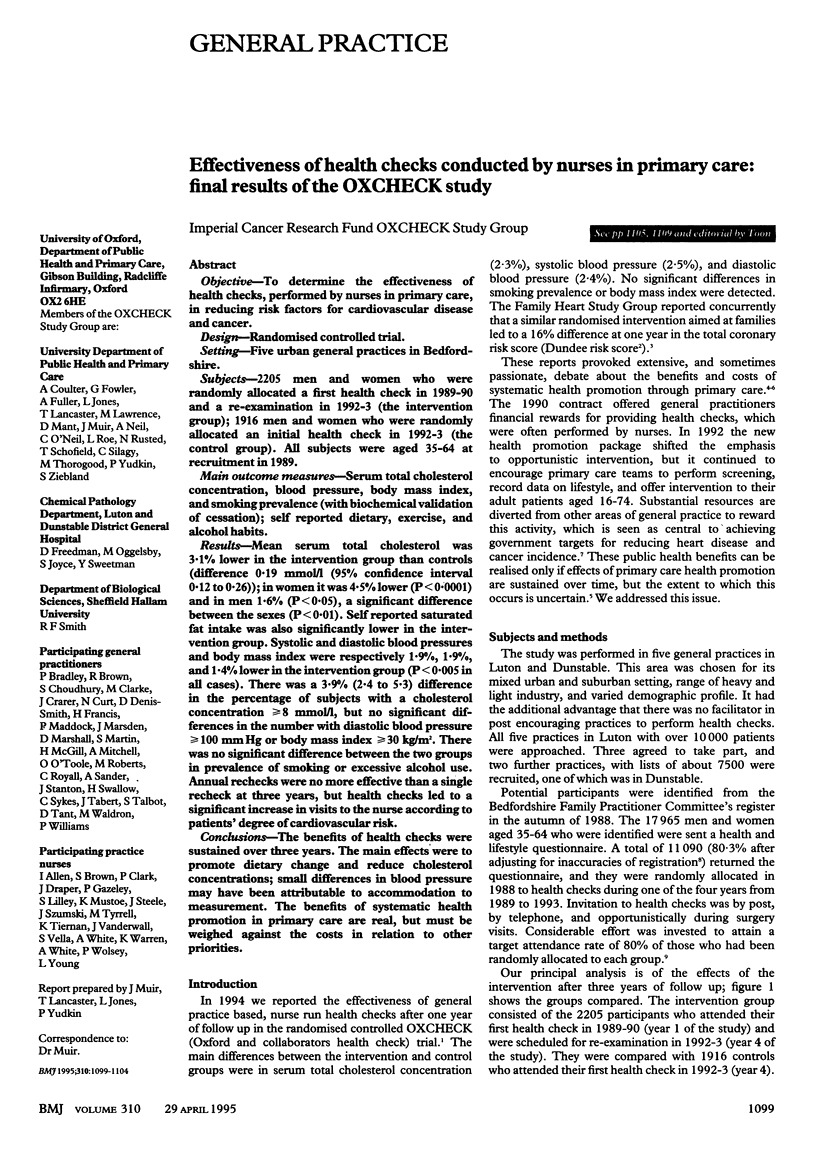

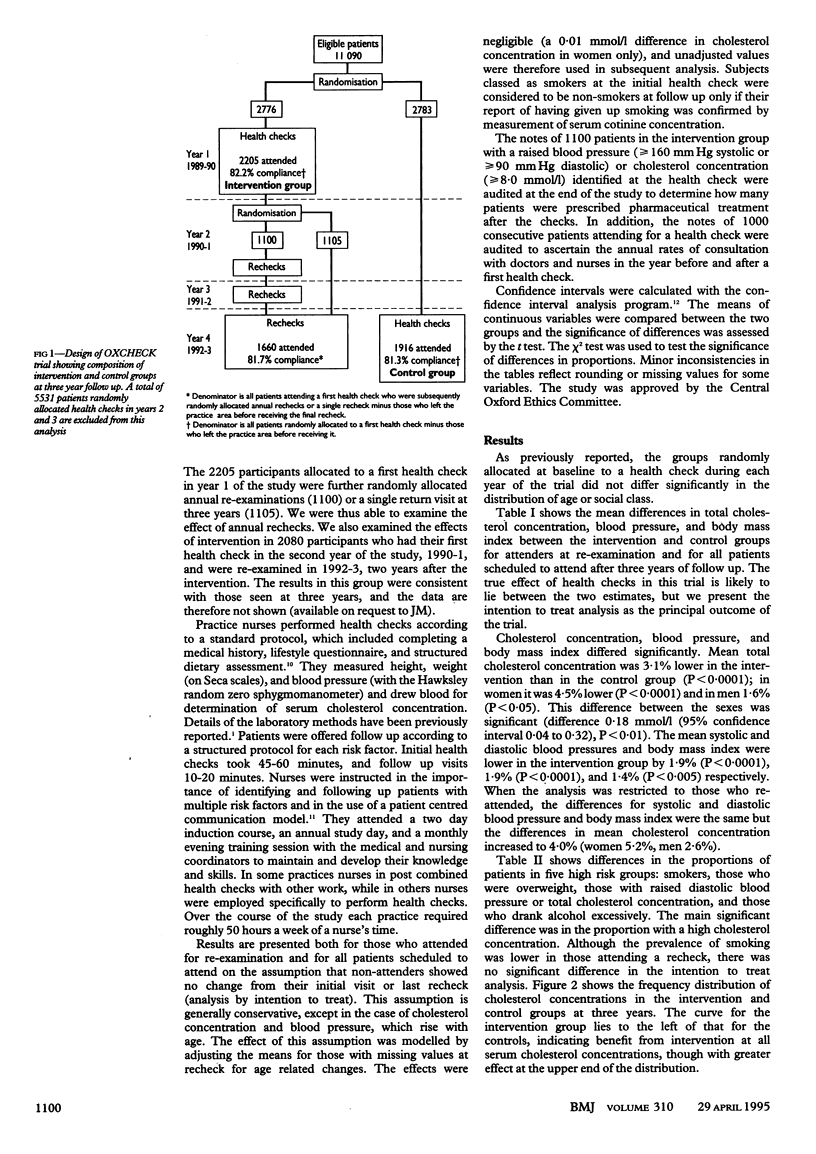

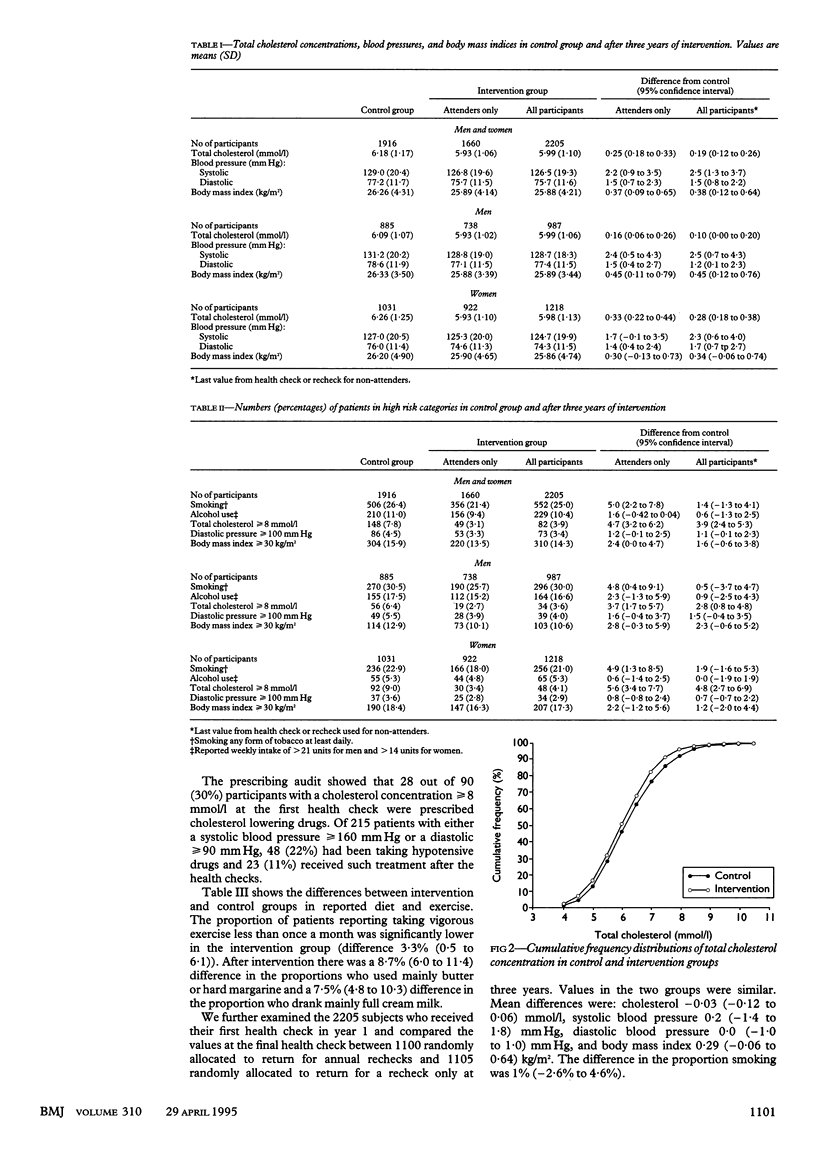

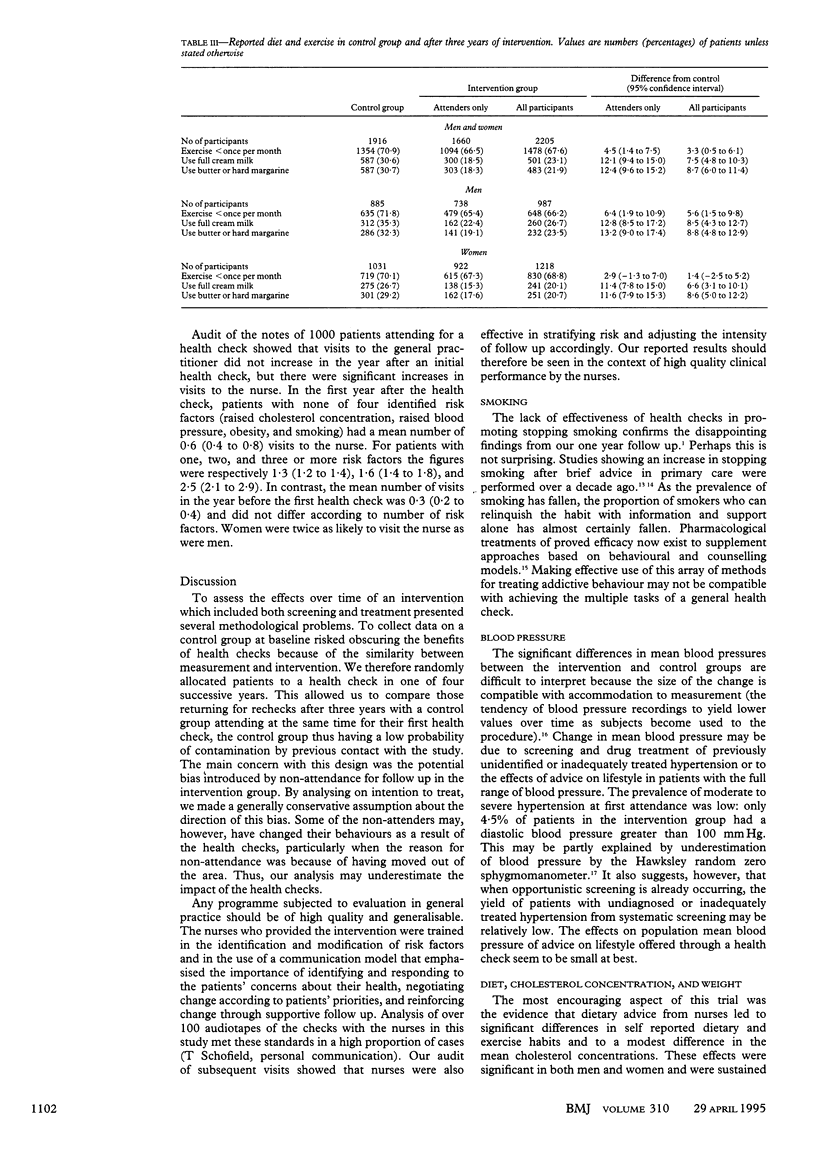

OBJECTIVE--To determine the effectiveness of health checks, performed by nurses in primary care, in reducing risk factors for cardiovascular disease and cancer. DESIGN--Randomised controlled trial. SETTING--Five urban general practices in Bedfordshire. SUBJECTS--2205 men and women who were randomly allocated a first health check in 1989-90 and a re-examination in 1992-3 (the intervention group); 1916 men and women who were randomly allocated an initial health check in 1992-3 (the control group). All subjects were aged 35-64 at recruitment in 1989. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES--Serum total cholesterol concentration, blood pressure, body mass index, and smoking prevalence (with biochemical validation of cessation); self reported dietary, exercise, and alcohol habits. RESULTS--Mean serum total cholesterol was 3.1% lower in the intervention group than controls (difference 0.19 mmol/l (95% confidence interval 0.12 to 0.26)); in women it was 4.5% lower (P < 0.0001) and in men 1.6% (P < 0.05), a significant difference between the sexes (P < 0.01). Self reported saturated fat intake was also significantly lower in the intervention group. Systolic and diastolic blood pressures and body mass index were respectively 1.9%, 1.9%, and 1.4% lower in the intervention group (P < 0.005 in all cases). There was a 3.9% (2.4 to 5.3) difference in the percentage of subjects with a cholesterol concentration > or = 8 mmol/l, but no significant differences in the number with diastolic blood pressure > or = 100 mm Hg or body mass index > or = 30 kg/m2. There was no significant difference between the two groups in prevalence of smoking or excessive alcohol use. Annual rechecks were no more effective than a single recheck at three years, but health checks led to a significant increase in visits to the nurse according to patients' degree of cardiovascular risk. CONCLUSIONS--The benefits of health checks were sustained over three years. The main effects were to promote dietary change and reduce cholesterol concentrations; small differences in blood pressure may have been attributable to accommodation to measurement. The benefits of systematic health promotion in primary care are real, but must be weighed against the costs in relation to other priorities.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Collins R., Peto R., MacMahon S., Hebert P., Fiebach N. H., Eberlein K. A., Godwin J., Qizilbash N., Taylor J. O., Hennekens C. H. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, Short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990 Apr 7;335(8693):827–838. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy R. M., O'Brien E., O'Malley K., Atkins N. Measurement error in the Hawksley random zero sphygmomanometer: what damage has been done and what can we learn? BMJ. 1993 May 15;306(6888):1319–1322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6888.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel S., Davison C., Smith G. D. Lay epidemiology and the rationality of responses to health education. Br J Gen Pract. 1991 Oct;41(351):428–430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R. B., Sackett D. L., Taylor D. W., Gibson E. S., Johnson A. L. Increased absenteeism from work after detection and labeling of hypertensive patients. N Engl J Med. 1978 Oct 5;299(14):741–744. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197810052991403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulley S. B., Walsh J. M., Newman T. B. Health policy on blood cholesterol. Time to change directions. Circulation. 1992 Sep;86(3):1026–1029. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.3.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M. R., Wald N. J., Thompson S. G. By how much and how quickly does reduction in serum cholesterol concentration lower risk of ischaemic heart disease? BMJ. 1994 Feb 5;308(6925):367–372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6925.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson J. E., Gaziano J. M., Jonas M. A., Hennekens C. H. Antioxidants and cardiovascular disease: a review. J Am Coll Nutr. 1993 Aug;12(4):426–432. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1993.10718332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mant D. Health checks--time to check out? Br J Gen Pract. 1994 Feb;44(379):51–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick J. Health promotion: the ethical dimension. Lancet. 1994 Aug 6;344(8919):390–391. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J. O., DiClemente C. C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983 Jun;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay L. E., Yeo W. W., Jackson P. R. Dietary reduction of serum cholesterol concentration: time to think again. BMJ. 1991 Oct 19;303(6808):953–957. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6808.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe L., Strong C., Whiteside C., Neil A., Mant D. Dietary intervention in primary care: validity of the DINE method for diet assessment. Fam Pract. 1994 Dec;11(4):375–381. doi: 10.1093/fampra/11.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell M. A., Wilson C., Taylor C., Baker C. D. Effect of general practitioners' advice against smoking. Br Med J. 1979 Jul 28;2(6184):231–235. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6184.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silagy C., Mant D., Fowler G., Lodge M. Meta-analysis on efficacy of nicotine replacement therapies in smoking cessation. Lancet. 1994 Jan 15;343(8890):139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90933-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silagy C., Muir J., Coulter A., Thorogood M., Roe L. Cardiovascular risk and attitudes to lifestyle: what do patients think? BMJ. 1993 Jun 19;306(6893):1657–1660. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6893.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott N. C., Kinnersley P., Rollnick S. The limits to health promotion. BMJ. 1994 Oct 15;309(6960):971–972. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6960.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott N. Screening for cardiovascular risk in general practice. BMJ. 1994 Jan 29;308(6924):285–286. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6924.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorogood M., Coulter A., Jones L., Yudkin P., Muir J., Mant D. Factors affecting response to an invitation to attend for a health check. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1993 Jun;47(3):224–228. doi: 10.1136/jech.47.3.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall-Pedoe H. The Dundee coronary risk-disk for management of change in risk factors. BMJ. 1991 Sep 28;303(6805):744–747. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6805.744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]