Abstract

The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor/channel (IP3R) is a major regulator of intracellular Ca2+ signaling, and liberates Ca2+ ions from the endoplasmic reticulum in response to binding at cytosolic sites for both IP3 and Ca2+. Although the steady-state gating properties of the IP3R have been extensively studied and modeled under conditions of fixed [IP3] and [Ca2+], little is known about how Ca2+ flux through a channel may modulate the gating of that same channel by feedback onto activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites. We thus simulated the dynamics of Ca2+ self-feedback on monomeric and tetrameric IP3R models. A major conclusion is that self-activation depends crucially on stationary cytosolic Ca2+ buffers that slow the collapse of the local [Ca2+] microdomain after closure. This promotes burst-like reopenings by the rebinding of Ca2+ to the activating site; whereas inhibitory actions are substantially independent of stationary buffers but are strongly dependent on the location of the inhibitory Ca2+ binding site on the IP3R in relation to the channel pore.

INTRODUCTION

The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) is a Ca2+ release channel that liberates Ca2+ ions from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) into the cytoplasm upon the binding of both inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and Ca2+ itself (1–4). The biphasic positive and negative feedback of Ca2+ ions on IP3R gating underlies the complexity of Ca2+ signals observed in intact cells, including Ca2+ “blips” that may represent openings of individual channels (5–7), local transients (Ca2+ “puffs”) restricted to clusters containing several IP3Rs (5,8,9), as well as global Ca2+ waves that propagate throughout the cell (10,11). An understanding of the Ca2+ feedback actions at the single channel level is crucial, since they underlie the complex hierarchy of local cytosolic calcium signals and global oscillations seen in cell types as diverse as smooth muscle and neurons (3,5,11). Correspondingly, however, this complexity makes it difficult to elucidate the functional properties of single IP3R under conditions where Ca2+ feedback is active (4,12). Instead, most of our detailed knowledge of IP3R gating derives from patch-clamp and bilayer recording of single IP3R channels under conditions where ions other than Ca2+ serve as the charge carrier, and where [Ca2+] on the cytosolic face is “clamped” at fixed levels by buffers (4,13,14). Another difficulty to study blip events is that the opening of one IP3R channel usually triggers openings of multiple adjacent channels in the cluster on ER membrane.

In addition to the IP3R dynamics, endogenous Ca2+ binding buffers also play a key role in determining the magnitude, kinetics, and spatial distribution of cytosolic Ca2+ signals (15,16). Different cell types selectively express mobile Ca2+ binding proteins with differing properties (17), suggesting that cells likely utilize buffers to shape Ca2+ signals for their specific function (15,16).

Models of IP3R play an important role not only for understanding single channel kinetics, but also as building blocks for constructing larger-scale models of cellular Ca2+ signaling. Different IP3R models have been suggested (18–23) and the calcium release dynamics have also been discussed accordingly, which are mainly at the level of local Ca2+ puffs (24–27) or at the level of global Ca2+ waves (28–32). However, due to the paucity of experimental data on blips, there are few modeling studies of single IP3R function within a cellular environment (33,34). Swillens et al. (33) proposed a monomeric IP3R model to account for the electrophysiological data obtained with an IP3R channel incorporated in a planar bilayer, and then explored the Ca2+ blip dynamics that result by placing the channel model in a realistic physiological environment. The simulated blip exhibited bursts of activity, arising from repetitive channel openings caused by the Ca2+ rebinding to the activating site due to the high Ca2+ concentration at the channel mouth just after closure. Furthermore, they noted that the amplitudes and rising times of the simulated blips are highly sensitive to buffering by the Ca2+ indicator dye.

The effects of endogenous Ca2+ buffers have also been investigated analytically and numerically (35–38). It was suggested that the rapid buffer could be approached by a rapid buffering approximation near a point source on timescales that are comparable to the equilibration times for Ca2+ buffers (36,37). With a stochastic IP3R model, the effects of slow buffer on the intracellular Ca2+ waves have been investigated, indicating that the high concentration of slow buffer can lead to an oscillatory behavior by repetitive wave nucleation for high Ca2+ content of the ER (38).

Here, we explore in detail the dynamics of blips and their modulation by immobile cytosolic Ca2+ buffers using an IP3R model proposed recently (39). This study represents an intermediate step toward our long-term goal to bridge the gap between single-channel studies and whole-cell Ca2+ imaging by using theoretical simulations to develop a unified model of IP3/Ca2+ signaling. We focus on the Xenopus oocyte as a model cell system, owing to the wealth of published experimental data on both single-IP3R properties (14) and cellular imaging studies (6,9). As a first step, we recently described a stochastic IP3R model (39) that satisfactorily replicated the steady-state gating kinetics of the Xenopus IP3R under conditions of fixed cytosolic [Ca2+]. We now extend this model to explore the effects of Ca2+ feedback, whereby Ca2+ flux through a single channel modulates the gating of that same channel via binding to activating and inhibitory sites on the IP3R molecule.

Our full IP3R model (39) is composed of four independent, identical subunits, each of which bears one IP3 binding site, one activating Ca2+ binding site, and one inhibitory Ca2+ binding site (Fig. 1 A). A subunit may enter an “active” conformation when the IP3 and activating (but not inhibitory) Ca2+ binding sites are occupied, and the channel opens when either three or four subunits are active. Two features of this model are of particular importance with regard to the ability of Ca2+ ions passing through the channel to bind to receptor sites on the cytosolic face and thereby modulate channel gating. First, transition to the active state of a subunit incorporates a conformational change such that the active state is “locked” to ligand binding: that is to say, Ca2+ cannot bind to or dissociate from either the activating or inhibitory sites of an active subunit. Ca2+ flux through an IP3R channel cannot, therefore, directly act on active subunits while the channel is open. Secondly, the assumption that only three subunits need to be active for the channel to open leads to an additional and more subtle modulation, because the high local [Ca2+] around the pore of an open channel results in a high probability of binding to the low-affinity inhibitory site of the remaining inactive subunit.

FIGURE 1.

IP3R subunit model and the multiple-grid-size method. (A) Schematic diagram of the IP3R channel subunit model. The subunit has an IP3 binding site, an activating Ca2+ binding site, and an inhibitory Ca2+ binding site. Bold arrows indicate the binding of ligands to different sites, and the shaded regions indicate conformations referred to as active, inactive (without Ca2+ bound to the inhibitory site), and inhibited (with Ca2+ bound to the inhibitory site). (B) In the model, we use a multiple-grid-size method to discretize the cytosolic space. An overlap region is used to connect the concentration in different regions. So concentration  at

at  is an average of the concentration

is an average of the concentration  at

at  and

and  at

at

Openings of single IP3R channels are believed to underlie “fundamental” IP3-mediated signals, such as Ca2+ blips (5,6) and trigger events (40,41) that serve a crucial role in initiating larger scale local and global responses through Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from neighboring channels. Our results provide important insights into the generation of these fundamental events, particularly regarding the effect of immobile cytosolic Ca2+ buffers in modulating feedback onto the IP3R by enhancing the activating Ca2+ rebinding actions, whereas the inhibitory binding dynamics are substantially independent of stationary buffers but are strongly dependent on the location of the inhibitory Ca2+ binding site on the IP3R in relation to the channel pore. The model, moreover, serves as a necessary stepping stone to construct stochastic models of the interactions among IP3Rs within a cluster.

METHODS

The IP3R subunit model

Our IP3R model (39) is derived from the original DeYoung-Keizer formulation (18), and is composed of four independent, identical subunits, each bearing one IP3 binding site, one activating Ca2+ binding site, and one inhibitory Ca2+ binding site (Fig. 1 A). A conformational step is introduced before a subunit becomes active. The subunit state is denoted (i j k), where i represents the IP3 binding site, j the activating Ca2+ binding site, and k the inhibitory Ca2+ binding site. The number 1 represents an occupied site and 0 a nonoccupied site. Bold arrows in Fig. 1 A indicate the binding of ligands to different sites, and the shaded regions indicate conformations referred to as “active”, “inactive” (without Ca2+ bound to the inhibitory site), and “inhibited” (with Ca2+ bound to the inhibitory site).

In our simulations, we begin by considering a simplified “toy” model wherein channel opening requires only a single active subunit so as to gain a better intuitive understanding of the actions of Ca2+ feedback, and then progress to a more realistic tetrameric model in which channel opening requires 3 or 4 active subunits.

Stochastic simulations and Ca2+ current of the IP3R channel

We simulated the stochastic dynamics of the nine-state IP3R subunit model by a Markov process, updating the state of the system at small time steps  μs. For example, a channel subunit in the (110) state at time t could transition to states (010), (100), (111), or to the active state at the next time step

μs. For example, a channel subunit in the (110) state at time t could transition to states (010), (100), (111), or to the active state at the next time step  with respective transition probabilities of

with respective transition probabilities of  or

or  otherwise it would remain in the same state. Random numbers homogeneously distributed in [0,1] were generated at each time step and compared with these transition probabilities to determine the state of the channel subunit at the next time step.

otherwise it would remain in the same state. Random numbers homogeneously distributed in [0,1] were generated at each time step and compared with these transition probabilities to determine the state of the channel subunit at the next time step.

A constant Ca2+ current  flows through an open channel from the ER into cytosolic space. The Ca2+ flux is expressed as

flows through an open channel from the ER into cytosolic space. The Ca2+ flux is expressed as

|

(1) |

where  and

and  is the spherical volume around the channel pore with radius

is the spherical volume around the channel pore with radius

In the model, we assume a constant Ca2+ current (flux) through an open IP3R channel, i.e.,  pA. The single-channel IP3R Ca2+ current that we assume here is within the range of 0.2–0.5 pA estimated in our previously published article (42), in which a detailed modeling study was presented for the fluorescence signals that would result from Ca2+ flux through a single IP3R, taking into account factors including diffusion, binding to indicator dye and cytosolic buffers, and the point-spread function of the confocal microscope, to provide good agreement with experimental imaging data.

pA. The single-channel IP3R Ca2+ current that we assume here is within the range of 0.2–0.5 pA estimated in our previously published article (42), in which a detailed modeling study was presented for the fluorescence signals that would result from Ca2+ flux through a single IP3R, taking into account factors including diffusion, binding to indicator dye and cytosolic buffers, and the point-spread function of the confocal microscope, to provide good agreement with experimental imaging data.

An alternative approach is to assume a Ca2+ flux that is proportional to the difference of free Ca2+ concentrations between the ER pool and the cytosolic space around the channel pore. Local depletion of Ca2+ in the ER pool may then reduce the Ca2+ flux throughout an open channel, as proposed for sparks in cardiac and skeletal muscle. However, such luminal depletion appears to be minimal for isolated puffs released from a few open channels in Xenopus oocytes, as observations of sequential puffs at intervals of a few hundred ms show little diminution in amplitude of the second puffs (43). Thus, a simple assumption is to consider a fixed ER Ca2+ concentration (e.g., 500 μM). In that case, our simulations indicate the Ca2+ current approaches an almost constant value within 1 ms after channel opening, which can be well approximated by a constant Ca2+ flux as used in our model.

Cytosolic Ca2+ diffusion

In this article, our goal was to study the dynamics of the single IP3R channel within a cytosolic-like environment. In that regard, we made several simplifying assumptions; neglecting Ca2+ pump dynamics (which are slow on the timescales considered here) and endogenous mobile buffers. Specifically, the model includes the following species in the cytosolic space: free Ca2+ ions ([Ca2+]), stationary buffer in free and Ca2+-bound ([SCa]) forms, and mobile buffer in free and Ca2+-bound ([MCa]) forms. In comparison to the large cytosolic volume, we treat the ER pool as an ideal point source occupying no volume.

A further simplification is that we calculate the transition probabilities of binding kinetics as functions of the calcium concentration at one grid point. Because of the exceedingly small volume with  nm associated with each grid point, the mean numbers of Ca2+ ions within that volume will typically be <1, introducing large stochastic fluctuations. However, it is computationally impracticable to undertake a particle simulation considering every individual ion. Instead, we justify our method of deterministic reaction-diffusion treatment for Ca2+ concentration by considering that characteristic binding times to sites on IP3R and buffers are of the order of milliseconds or even hundreds of milliseconds, whereas diffusional exchange of free Ca2+ ions within a grid volume with

nm associated with each grid point, the mean numbers of Ca2+ ions within that volume will typically be <1, introducing large stochastic fluctuations. However, it is computationally impracticable to undertake a particle simulation considering every individual ion. Instead, we justify our method of deterministic reaction-diffusion treatment for Ca2+ concentration by considering that characteristic binding times to sites on IP3R and buffers are of the order of milliseconds or even hundreds of milliseconds, whereas diffusional exchange of free Ca2+ ions within a grid volume with  nm will occur within only about

nm will occur within only about  0.125 μs for diffusion coefficient

0.125 μs for diffusion coefficient  μm2/s, thereby averaging out fluctuations on the timescales of interest (34).

μm2/s, thereby averaging out fluctuations on the timescales of interest (34).

The diffusion equation for free Ca2+ ions ([Ca2+]) with diffusion coefficient D is described as follows:

|

(2) |

in which the function  at the origin point represents the channel location; otherwise,

at the origin point represents the channel location; otherwise,  The total concentrations of Ca2+ stationary buffer and mobile buffer are

The total concentrations of Ca2+ stationary buffer and mobile buffer are  and

and  respectively, and

respectively, and  is the Ca2+ bound rate and

is the Ca2+ bound rate and  the Ca2+ unbound rate for buffers. For Ca2+-bound stationary buffer ([SCa]) with diffusion coefficient

the Ca2+ unbound rate for buffers. For Ca2+-bound stationary buffer ([SCa]) with diffusion coefficient

|

(3) |

For Ca2+-bound mobile buffer ([MCa]) with diffusion coefficient

|

(4) |

We simulate the propagation of Ca2+ throughout a homogeneous three-dimensional cytosolic space. Following from the spherical symmetry around the channel pore, Ca2+ diffusion can be described in spherical coordinates with the Laplacian operator

|

(5) |

Thus, we calculate the time-dependent distribution of Ca2+ concentration along the radial direction.

The numerical method for Ca2+ diffusion

The finite difference method proposed by Smith et al. (37) was used to solve the partial differential equations. Considering a time increment  and spatial grid distance

and spatial grid distance  an explicit numerical scheme for the calcium diffusion that is second-order accurate in space and first-order accurate in time is then given by

an explicit numerical scheme for the calcium diffusion that is second-order accurate in space and first-order accurate in time is then given by

|

(6) |

where  represents the free calcium concentration at location

represents the free calcium concentration at location  and time

and time  and

and  denote the contribution of the reaction terms with stationary buffer and mobile buffer at location

denote the contribution of the reaction terms with stationary buffer and mobile buffer at location  and time

and time  respectively:

respectively:

|

(7) |

where  and

and  represent the concentrations of Ca2+-bound stationary buffer and mobile buffer at location

represent the concentrations of Ca2+-bound stationary buffer and mobile buffer at location  and time

and time  respectively. For stationary buffer

respectively. For stationary buffer  we have

we have

|

(8) |

For mobile buffer  at location

at location  and time

and time  the difference equations are similar as given in Eq. 6.

the difference equations are similar as given in Eq. 6.

The total radius of the simulated cytosolic space is  μm. To enhance the computation speed, we applied a multiple-grid-size method to discretize the cytosolic space as follows: for the first regime at

μm. To enhance the computation speed, we applied a multiple-grid-size method to discretize the cytosolic space as follows: for the first regime at  μm,

μm,  nm with 20 grids that are marked as

nm with 20 grids that are marked as  with the superscript “[1]” corresponding to the smallest grid region; for the second regime at

with the superscript “[1]” corresponding to the smallest grid region; for the second regime at  μm,

μm,  nm with 20 grids marked as

nm with 20 grids marked as  for

for  μm,

μm,  nm with 20 grids; for

nm with 20 grids; for  μm,

μm,  nm with 20 grids; and for

nm with 20 grids; and for  μm,

μm,  nm with 25 grids. Thus there is an overlap between each two connected regions. Overlap regions are used to ensure that the calcium concentrations at the same position, but with different grid sizes, are connected correctly. For example, as shown in Fig. 1 B, the calcium concentration

nm with 25 grids. Thus there is an overlap between each two connected regions. Overlap regions are used to ensure that the calcium concentrations at the same position, but with different grid sizes, are connected correctly. For example, as shown in Fig. 1 B, the calcium concentration  at

at  is an average of the concentration

is an average of the concentration  at

at  and

and  at

at  with different volume weight. Thus we have

with different volume weight. Thus we have

|

(9) |

Here the superscript in brackets corresponds to the different grid refinement  considered and the subscript corresponds to the ordering i within the grid set. We can write out the similar equation for

considered and the subscript corresponds to the ordering i within the grid set. We can write out the similar equation for  and then we have

and then we have

|

(10) |

These two equations are used for the determination of boundary condition of free Ca2+ concentration at different grid-size regions. Similar equations can be given for stationary buffer and mobile buffer.

The resting concentration of free Ca2+ ions  μM. Then the resting concentrations of stationary buffer and mobile buffer are

μM. Then the resting concentrations of stationary buffer and mobile buffer are  and

and  respectively. At the boundaries of the system, the concentrations of all signal species are held constant at their resting states. Because the smallest grid size

respectively. At the boundaries of the system, the concentrations of all signal species are held constant at their resting states. Because the smallest grid size  nm, the calcium concentration is updated with time step

nm, the calcium concentration is updated with time step  μs.

μs.

Parameter values

The parameter values used in the model are given in the Table 1. For the IP3R channel kinetics, dissociation constants  with

with  on-binding rate and

on-binding rate and  off-binding rate. Due to the thermodynamic constraint, we have

off-binding rate. Due to the thermodynamic constraint, we have  The binding and unbinding rates of the IP3R channel are taken mainly from our earlier study (39), excepting that the rate constant

The binding and unbinding rates of the IP3R channel are taken mainly from our earlier study (39), excepting that the rate constant  for activating Ca2+ binding was reduced to 30 μM−1s−1 to match recent experimental measurements of long first-opening latencies of IP3R channels in Sf9 cell nuclei at [IP3] = 10 μM after step increases in [Ca2+] from 0 to 2.5 μM (44). It was shown that the channel activation by a jump from low (<10 nM) to optimal (2 μM) [Ca2+] had a mean latency of 40 ms, and the channel deactivation when Ca2+ was returned to <10 nM from 2 μM had a mean latency of 160 ms (44). For the current model with the modified

for activating Ca2+ binding was reduced to 30 μM−1s−1 to match recent experimental measurements of long first-opening latencies of IP3R channels in Sf9 cell nuclei at [IP3] = 10 μM after step increases in [Ca2+] from 0 to 2.5 μM (44). It was shown that the channel activation by a jump from low (<10 nM) to optimal (2 μM) [Ca2+] had a mean latency of 40 ms, and the channel deactivation when Ca2+ was returned to <10 nM from 2 μM had a mean latency of 160 ms (44). For the current model with the modified  the mean latency for Ca2+ activation binding is 20 ms and the mean latency for Ca2+ deactivation unbinding is 170 ms. As a comparison, the previous IP3R model gave the mean latencies of 80 ms and 280 ms for activation and deactivation, respectively (39).

the mean latency for Ca2+ activation binding is 20 ms and the mean latency for Ca2+ deactivation unbinding is 170 ms. As a comparison, the previous IP3R model gave the mean latencies of 80 ms and 280 ms for activation and deactivation, respectively (39).

TABLE 1.

Parameter values used in the model

| Parameter | Value (unit) | |

|---|---|---|

| System size | R | 3.2 μm |

| Free Ca2+ | [Ca2+]Rest | 0.05 μM |

| D | 200 μm2/s | |

| Stationary Ca2+ buffer |  |

0 ∼ 10,000 μM |

| αS | 400 μM−1s−1 | |

|

800 s−1 | |

| Mobile Ca2+ buffer |  |

0 ∼ 1000 μM |

|

1 ∼ 200 μm2/s | |

| αS | 150 μM−1s−1 | |

|

300 s−1 | |

| IP3 concentration | [IP3] | 0.001 ∼ 50 μM |

| Channel current |  |

0.2 pA |

| Conformation change rate |  |

540 s−1 |

|

80 s−1 | |

| Channel IP3 binding site |  |

0.0036 μM |

|

60 μM−1s−1 | |

|

0.8 μM | |

|

5 μM−1s−1 | |

| Channel activating Ca2+ binding site |  |

0.8 μM |

|

30 μM−1s−1 | |

| Channel inhibitory Ca2+ binding site |  |

16 μM |

|

0.04 μM−1s−1 | |

|

0.072 μM | |

|

0.5 μM−1s−1 |

RESULTS

The Ca2+ microdomain around an IP3R channel pore

The ability of Ca2+ ions that have passed through an IP3R channel to bind to modulatory sites on the cytosolic domain of that channel depends crucially on the spatial and temporal dynamics of the local cytosolic microdomain of Ca2+ around the channel pore. We thus began by making deterministic simulations of this local Ca2+ distribution during and after channel openings, and explored the effects of stationary Ca2+ buffer on the microdomain.

Fig. 2 A plots the radial [Ca2+] distribution around the pore immediately before the end of a 20 ms channel opening, and at different times after the channel closes. Fig. 2 B shows the corresponding time courses of [Ca2+] at different distances from the pore. In this example, no buffers are present, and Ca2+ ions diffuse freely in aqueous medium with a diffusion coefficient of 200 μm2/s. The main qualitative results are that an extremely steep Ca2+ gradient is established very quickly after the channel opens, and that this subsequently collapses rapidly after channel closing to leave a residual microdomain extending over a few μm that persists for several ms (Fig. 2 A). For example, the local [Ca2+] in the grid element at the channel pore rises as high as 400 μM while the channel is open, but at a distance of 15 nm (corresponding to the dimensions of the IP3R molecule (2)), the concentration is only ∼27 μM. Once the channel closes, [Ca2+] at the pore drops precipitously to 0.5 μM within 0.5 ms, and the radial gradient collapses such that concentrations in the residual microdomain are almost the same at the pore and the channel edge.

FIGURE 2.

[Ca2+] distribution around the channel mouth. (A and B) Spatial and temporal distributions of cytosolic [Ca2+] around the pore of an IP3R channel in the absence of any Ca2+ buffer. The channel is assumed to open for 20 ms, carrying a Ca2+ current of 0.2 pA. (A) Spatial [Ca2+] distribution as a function of distance from the channel pore at the instant before channel closes (T = 0) and at different times (indicated in ms) after closing. (B) Temporal changes in [Ca2+] at the channel pore ( ) and at different distances (indicated in nm) from the pore. (C and D) Corresponding simulations with stationary Ca2+ buffer in the cytosolic space. (C) Spatial [Ca2+] distributions at T = 0 and at different times after the channel closed, for a stationary buffer concentration

) and at different distances (indicated in nm) from the pore. (C and D) Corresponding simulations with stationary Ca2+ buffer in the cytosolic space. (C) Spatial [Ca2+] distributions at T = 0 and at different times after the channel closed, for a stationary buffer concentration  μM. (D) Temporal traces of [Ca2+] at channel pore for different stationary buffer concentrations as indicated in μM.

μM. (D) Temporal traces of [Ca2+] at channel pore for different stationary buffer concentrations as indicated in μM.

This residual microdomain plays a key role in modulating IP3R function in our model, since Ca2+ cannot bind to regulatory sites of active subunits in an open channel. Immobile cytosolic Ca2+ buffer exerts two prominent effects on the spatiotemporal properties of the microdomain (Fig. 2, C and D). There are two prominent effects. i), The spread of free [Ca2+] around an open or recently closed channel narrows from several μm to <1 μm because of the reduction in effective diffusion coefficient for Ca2+ (Fig. 2 C). ii), The decay of local free [Ca2+] after channel closure becomes greatly slowed because the buffer acts as a reservoir, continuing to release free Ca2+ ions that had become bound while the channel was open (Fig. 2 D). Fig. 2 D further shows how the free [Ca2+] decay rate at the channel pore slows as a function of increasing concentration of immobile buffer. For example, whereas free [Ca2+] at the pore drops to 100 nM within 8 ms after the channel closes in the absence of buffering, the same fall in concentration requires >140 ms in the presence of 1 mM immobile buffer.

The simplified monomeric IP3R model

To gain an intuitive understanding of how IP3R gating is modulated by Ca2+ feedback from Ca2+ passing through the channel, we first consider a simplified monomeric toy model, wherein gating is controlled by only a single subunit; i.e., a channel that has only a single functional subunit and opens when that subunit is in the active state.

Bursting behavior of the monomeric IP3R model

For purposes of comparison, we first discuss the channel open/close dynamics when cytosolic [Ca2+] is fixed at the resting concentration of 0.05 μM (Fig. 3 A), and then consider how these dynamics are modified by feedback of Ca2+ flowing through the channel in the absence (Fig. 3 B) or presence of stationary Ca2+ buffer (Fig. 3 C). In these examples, no mobile buffers are present. Fig. 3 A illustrates typical channel dynamics for [IP3] = 10 μM when Ca2+ is not the charge carrier and cytosolic free [Ca2+] is fixed at 0.05 μM, so as to simulate typical conditions in patch-clamp experiments (14). The channel gating shows a bursting characteristic (top panel in Fig. 3 A), dominated by the binding and unbinding Ca2+ to the activating site (bottom panel in Fig. 3 A), since the affinity for inhibitory Ca2+ binding is low (K2 = 16 μM) in comparison to the basal [Ca2+] and the subunit is primarily in IP3-bound states. The dynamics within a burst result largely from fast, ligand-independent transitions between the active state and (110) states, with longer interburst intervals largely reflecting dwell times in the (100) state with durations =  for [Ca2+] = 50 nM. Fig. 4 A (solid curve) shows the dependence of PO on [IP3], derived by the transition matrix theory (see Appendix A).

for [Ca2+] = 50 nM. Fig. 4 A (solid curve) shows the dependence of PO on [IP3], derived by the transition matrix theory (see Appendix A).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Representative dynamics of the monomeric model with [Ca2+] clamped at 0.05 μM and [IP3] = 10 μM. The upper panel illustrates bursting behavior of channel states (0 = closed, 1 = open) on a slow timescale, and the second panel shows channel gating during a single burst on an expanded timescale. The third panel shows local [Ca2+] at the channel pore, and the lower panel shows transitions between different subunit states during the burst. (B) Corresponding examples of channel, [Ca2+] and subunit dynamics for the case where Ca2+ ions flow through the channel. No Ca2+ buffers are present. [IP3] = 10 μM. (C) Monomeric IP3R model dynamics with Ca2+ flux in the presence of stationary buffer  μM in the cytosolic compartment. [IP3] = 10 μM.

μM in the cytosolic compartment. [IP3] = 10 μM.

FIGURE 4.

Statistical dynamics of the monomeric IP3R model. (A) Channel open probability  as a function of [IP3]. The solid line is obtained with [Ca2+] clamped at 0.05 μM; the squares are simulation results with Ca2+ feedback in the absence of any Ca2+ buffers, and the stars are results with Ca2+ feedback in the presence of immobile cytosolic buffer

as a function of [IP3]. The solid line is obtained with [Ca2+] clamped at 0.05 μM; the squares are simulation results with Ca2+ feedback in the absence of any Ca2+ buffers, and the stars are results with Ca2+ feedback in the presence of immobile cytosolic buffer  μM. (B and C) Cumulative probabilities of Ca2+ binding to the activating Ca2+ site (B) and to the inhibitory Ca2+ site (C) of the monomeric model at increasing times latency after the channel closes. [IP3] = 10 μM. In both panels, the dashed lines are obtained with [Ca2+] clamped at 0.05 μM; the solid curves are calculated with Ca2+ feedback in the absence of buffer; and the dotted curves are with Ca2+ feedback in the presence of stationary buffer

μM. (B and C) Cumulative probabilities of Ca2+ binding to the activating Ca2+ site (B) and to the inhibitory Ca2+ site (C) of the monomeric model at increasing times latency after the channel closes. [IP3] = 10 μM. In both panels, the dashed lines are obtained with [Ca2+] clamped at 0.05 μM; the solid curves are calculated with Ca2+ feedback in the absence of buffer; and the dotted curves are with Ca2+ feedback in the presence of stationary buffer  μM.

μM.

Ca2+ feedback effect on the monomeric IP3R in the absence of any buffers

Next, we consider how the dynamics of the simplified, monomeric IP3R model are modified when Ca2+ ions flow through the channel, creating a cytosolic Ca2+ microdomain in which Ca2+ ions may bind to the activating and inhibitory sites in the absence of any Ca2+ buffers. We numerically solve Ca2+ diffusion by a finite difference method and initially consider only free aqueous diffusion, unmodified by the presence of any Ca2+ buffers. An example of the resulting channel dynamics is given in Fig. 3 B for [IP3] = 10 μM, which can be directly compared to the corresponding dynamics with fixed cytosolic [Ca2+] (Fig. 3 A). A surprising result is that the IP3R displays qualitatively similar burst-type dynamics (top panels in Fig. 3, A and B) irrespective of whether local cytosolic [Ca2+] is clamped (third panel in Fig. 3 A) or changes with Ca2+ flux through the channel (third panel in Fig. 3 B). As shown in Fig. 4 A, the close similarity of simulation results obtained with Ca2+ as the flux carrier (square symbols) with clamped Ca2+ (solid line) further shows that Ca2+ feedback has little quantitative effect on the dependency of Po as a function of [IP3], even though the activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites are located at the channel pore where they experience maximal changes in [Ca2+]. Thus, in the absence of Ca2+ buffers, Ca2+ feedback has little influence on Po.

The explanation for this arises principally from our assumption that subunit activation requires a preceding conformational step, so that when the channel is open (i.e., the single subunit in the monomeric model is in the active conformation), Ca2+ cannot bind to the inhibitory site or dissociate from activating site (Fig. 1 A). Thus, Ca2+ ions fluxing through the pore cannot modify the IP3R dynamics while the channel is open, and any feedback is limited to whatever residual Ca2+ remains in the microdomain after the channel has closed and the subunit has exited the active state. Immediately after the channel closes, [Ca2+] at the pore mouth falls precipitously; e.g., from 400 μM to 1 μM within 0.1 ms and then to 0.1 μM after ∼5 ms. To elucidate why this “tail” of [Ca2+] does not change the channel dynamics significantly, we then calculated (see Appendix B for details) the cumulative probabilities of Ca2+ binding to the activating site and inhibitory sites as functions of time after channel closure (solid curves, Fig. 4, B and C, respectively), and compared these with corresponding binding probabilities for the case of a fixed cytosolic [Ca2+] of 0.05 μM (dashed curves, Fig. 4, B and C). Although the activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding probabilities in the case of Ca2+ ion as the flux carrier are greater than those in the case of clamped Ca2+, the absolute differences between them are slight (increased probability of ∼0.025 for binding to the activating site and 0.0008 for inhibitory binding), so that the likelihood of Ca2+-dependent activation or inhibition is minimal during the brief time before the local [Ca2+] collapses down to the basal resting level.

Modulation of Ca2+ feedback by stationary buffer

Given that the persistence of the Ca2+ microdomain after channel closure is critical for determining whether Ca2+ flux can significantly modulate the channel gating, we then considered the effects of immobile Ca2+ buffer in modifying the dynamics of the Ca2+ microdomain. Fig. 3 C shows an example of channel dynamics with the monomeric model under identical conditions to those considered above, except that immobile cytosolic buffer is introduced at a concentration  μM. This results in a dramatic increase in open probability and a prolongation of burst durations. For example, for [IP3] > 0.05 μM, PO is ∼3 times greater in the presence of 300 μM stationary buffer than without buffer (Fig. 4 A, dotted curve).

μM. This results in a dramatic increase in open probability and a prolongation of burst durations. For example, for [IP3] > 0.05 μM, PO is ∼3 times greater in the presence of 300 μM stationary buffer than without buffer (Fig. 4 A, dotted curve).

The reason why stationary buffer increases PO is given as follows. Once the channel closes when the subunit transitions from the active state to state (110), free [Ca2+] collapses extremely rapidly around the channel pore (e.g., to 3 μM within ∼0.5 ms) at an initial rate that is not appreciably slowed by the presence of buffer. The probability of Ca2+ binding to the low-affinity inhibitory binding site during this brief period is very small, so the subunit typically goes to the state (100). However, as shown in Fig. 2, C and D, increasing concentrations of stationary buffer promote a biphasic decay of local free [Ca2+], and greatly prolong the time for which Ca2+ concentrations then remain elevated at a few hundred nM. This Ca2+ tail greatly increases the probability that Ca2+ will bind to the high-affinity activating site, causing the channel to return to the (110) state and thus reopen (Fig. 4 B, dotted curve). Although the probability of binding to the inhibitory site is concurrently potentiated, the absolute value remains very small (0.003: Fig. 4 C, dotted curve), so inhibition is negligible.

These dynamics do not occur for DeYoung-Keizer-type models of the IP3R (18), which lack the A-state. When such a channel is open (i.e., in 110-state), the local high concentration of Ca2+ resulting from flux through the open channel promotes binding to the inhibitory site, forcing the channel into an inhibited state (111) with a long characteristic time (e.g., 0.25 s with  μM−1s−1 and [Ca2+] = 100 μM). Once in (111) state, the residual Ca2+ tail remaining after the channel closes will have little effect on the channel dynamics. The channel closing in a model without A-state will predominantly involve dissociation of activating Ca2+, i.e., from the open state(110) to the state (100) with a short characteristic time 0.04 s at b5 = 24 s−1, before inhibitory Ca2+ has time to bind. Furthermore, the fast transient dynamics between the open state (110) and the state (100) (i.e., the dissociation of activating Ca2+) result again in a bursting behavior.

μM−1s−1 and [Ca2+] = 100 μM). Once in (111) state, the residual Ca2+ tail remaining after the channel closes will have little effect on the channel dynamics. The channel closing in a model without A-state will predominantly involve dissociation of activating Ca2+, i.e., from the open state(110) to the state (100) with a short characteristic time 0.04 s at b5 = 24 s−1, before inhibitory Ca2+ has time to bind. Furthermore, the fast transient dynamics between the open state (110) and the state (100) (i.e., the dissociation of activating Ca2+) result again in a bursting behavior.

The complete tetrameric IP3R model with four subunits

Finally, we consider a complete, multimeric IP3R model composed from four subunits. A notable functional difference from the single-subunit model results from the assumption that the channel can open when only three subunits are in the active state. Thus, Ca2+ binding to the fourth, inactive subunit may now occur as a result of the very high local [Ca2+] established while the channel is open. Similarly, for purposes of comparison, we first discuss the channel dynamics when cytosolic [Ca2+] is fixed at 0.05 μM (Fig. 5, A and B), and then consider how these dynamics are modified by feedback of Ca2+ flowing through the channel in the absence or presence of stationary and mobile Ca2+ buffers.

FIGURE 5.

Dynamics of the complete, multimeric IP3R model. (A) Representative channel kinetics with [Ca2+] clamped at 0.05 μM. The upper panel illustrates bursting behavior of channel states on a slow timescale; the second panel shows local [Ca2+] at the channel pore and, in gray overlay, channel openings during a single burst at an expanded timescale; the lower panel shows the number of subunits in the active state before, during, and after the burst. (B) Panels represent the states of the four subunits corresponding to the burst shown in A. (C and D) Corresponding examples of channel gating, local [Ca2+], and subunit states with Ca2+ feedback in the absence of any Ca2+ buffer. (E and F) Corresponding examples of channel gating, local [Ca2+], and subunit states with Ca2+ feedback in the presence of stationary buffer  μM. In all examples, [IP3] = 10 μM.

μM. In all examples, [IP3] = 10 μM.

Multimeric channel with fixed cytosolic [Ca2+]

For the multimeric IP3R with [Ca2+] clamped at 0.05 μM, the channel open probability  mean open time

mean open time  and mean closed time

and mean closed time  are depicted in Fig. 6, A–C (solid squares), as functions of [IP3], derived by transition matrix theory (see Appendix C). In comparison to the monomeric model at the equivalent [IP3], the tetrameric IP3R model shows a low

are depicted in Fig. 6, A–C (solid squares), as functions of [IP3], derived by transition matrix theory (see Appendix C). In comparison to the monomeric model at the equivalent [IP3], the tetrameric IP3R model shows a low  since at least three subunits must be in the active state for the channel to open. The channel shows bursting dynamics, with a bimodal distribution of closed times composed from relatively long interburst intervals and shorter closings within bursts. The close time distribution shows a local minimum around 20 ms, and we thus used a criterion of 20 ms to discriminate inter- from intraburst closings. We plot in Fig. 6, D–F (squares), the mean burst duration (

since at least three subunits must be in the active state for the channel to open. The channel shows bursting dynamics, with a bimodal distribution of closed times composed from relatively long interburst intervals and shorter closings within bursts. The close time distribution shows a local minimum around 20 ms, and we thus used a criterion of 20 ms to discriminate inter- from intraburst closings. We plot in Fig. 6, D–F (squares), the mean burst duration ( ) and inter- (

) and inter- ( ) and intraburst (

) and intraburst ( ) intervals as functions of [IP3]. A short

) intervals as functions of [IP3]. A short  ∼ 2 ms is obtained, which is determined mainly by

∼ 2 ms is obtained, which is determined mainly by  corresponding to fast transitions between the active state and the closed state (110).

corresponding to fast transitions between the active state and the closed state (110).

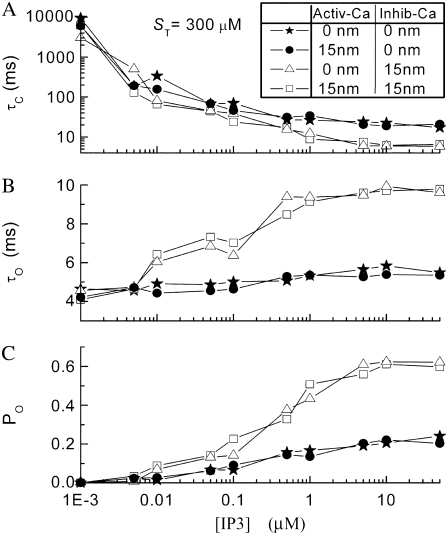

FIGURE 6.

Statistical dynamics of the multimeric IP3R channel in the absence of Ca2+ buffer, exploring separately the effects of Ca2+ feedback on the activating and inhibitory binding sites located at the channel pore. (A–C) Panels show, respectively, the mean channel closed time  the mean open time

the mean open time  and the open probability

and the open probability  as functions of [IP3]. (D–F) Burst dynamics of the channel, derived by setting a criterion of 20 ms to discriminate between short interburst closings and longer intraburst intervals. Panels show, respectively, mean interburst durations, mean intraburst intervals, and mean burst durations as functions of [IP3]. In all panels, the families of curves were obtained by either fixing [Ca2+] at the activating and/or inhibitory binding sites at the resting level, or by allowing Ca2+ feedback via flux through the channel. Specifically, squares represent both activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites clamped at [Ca2+] = 0.05 μM; stars represent inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites clamped; triangles represent Ca2+ feedback on inhibitory sites with activating sites clamped; and circles represent Ca2+ feedback on both activating and inhibitory binding sites.

as functions of [IP3]. (D–F) Burst dynamics of the channel, derived by setting a criterion of 20 ms to discriminate between short interburst closings and longer intraburst intervals. Panels show, respectively, mean interburst durations, mean intraburst intervals, and mean burst durations as functions of [IP3]. In all panels, the families of curves were obtained by either fixing [Ca2+] at the activating and/or inhibitory binding sites at the resting level, or by allowing Ca2+ feedback via flux through the channel. Specifically, squares represent both activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites clamped at [Ca2+] = 0.05 μM; stars represent inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites clamped; triangles represent Ca2+ feedback on inhibitory sites with activating sites clamped; and circles represent Ca2+ feedback on both activating and inhibitory binding sites.

Dynamics of the tetrameric channel with free Ca2+ feedback

Next, we consider the dynamics of the multimeric channel with Ca2+ as the flux carrier in the absence of any Ca2+ buffer. Fig. 5 C illustrates channel gating dynamics at [IP3] = 10 μM, together with an expanded view of local [Ca2+] changes and subunit states during a single burst; and Fig. 5 D shows the corresponding conformations of each subunit. For this simulation, both the activating and inhibitory binding sites are located at the channel pore, and hence experience maximal changes in [Ca2+] when the channel is open.

During the initial part of the burst, all four subunits are predominantly in the active state, and closings are relatively rare as transition of any single subunit from the active state leaves the channel open. However, after a brief time, one subunit does become Ca2+-inhibited, as marked by arrows (Fig. 5, C and D). This happens when the channel is open with one subunit in an inactive state, so that the high local [Ca2+] resulting from flux through the open channel results in Ca2+ binding to its inhibitory site. Given that the rate of dissociation from the inhibitory site is slow ( ), only three subunits then remain available to continue the burst, which ultimately terminates as discussed above for the monomeric channel model. In particular, there is a very low probability that termination results from two or more subunits becoming inhibited, because transition of any of the three remaining active subunits to an inactive state causes the channel to close, resulting in a rapid collapse of the local Ca2+ microdomain, leaving little chance for Ca2+ to bind to an inactive subunit.

), only three subunits then remain available to continue the burst, which ultimately terminates as discussed above for the monomeric channel model. In particular, there is a very low probability that termination results from two or more subunits becoming inhibited, because transition of any of the three remaining active subunits to an inactive state causes the channel to close, resulting in a rapid collapse of the local Ca2+ microdomain, leaving little chance for Ca2+ to bind to an inactive subunit.

The resulting steady-state channel dynamics and bursting kinetics are plotted as open circles in, respectively, Fig. 6, A–C and D–F, as functions of [IP3]. Notably, feedback of Ca2+ ions flowing through the channel to act on binding sites located at the pore produces only small changes in behavior from the situation when cytosolic [Ca2+] is clamped at the resting level (compare data marked by squares and circles in Fig. 6).

To help understand this lack of effect, we separately considered the effects of Ca2+ feedback on only the activating sites or only the inhibitory sites by clamping [Ca2+] at the other set of sites at 0.05 μM. That is to say, for those sites with clamped [Ca2+], a fixed calcium concentration of  μM was used to compute their Ca2+-binding probabilities, whereas for those sites with feedback [Ca2+], a kinetic calcium concentration obtained from the reaction-diffusion equations was used to calculate their Ca2+-binding probabilities. Although biologically unrealistic, this is a useful modeling exercise to help dissect out the otherwise intertwined actions of activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites; and is equivalent to functionally “knocking out” one or other type of site.

μM was used to compute their Ca2+-binding probabilities, whereas for those sites with feedback [Ca2+], a kinetic calcium concentration obtained from the reaction-diffusion equations was used to calculate their Ca2+-binding probabilities. Although biologically unrealistic, this is a useful modeling exercise to help dissect out the otherwise intertwined actions of activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites; and is equivalent to functionally “knocking out” one or other type of site.

The open triangles in Fig. 6 show that feedback exclusively on inhibitory binding sites promotes a slight decrease of PO (Fig. 6 C) and shortening of burst duration (Fig. 6 F). This is expected, since one subunit would rapidly become Ca2+-inhibited so that subsequent openings involve three out of three “activatable” subunits, rather than three out of four for the case without any Ca2+ feedback. More dramatically, however, Ca2+ feedback operating exclusively on the activating binding sites results in a roughly 10-fold increase in PO and lengthening of burst duration (stars in Fig. 6). This may be readily understood by first considering the channel in an open state with all four subunits active. Transition of any one subunit to an inactive state and subsequent dissociation of activating Ca2+ will very rapidly result in rebinding of Ca2+, since the activating site is exposed to high local [Ca2+] as the remaining three active subunits maintain the channel in the open state. Thus, any subunit that becomes inactive will rapidly reactivate, thereby greatly prolonging bursts of channel openings (Fig. 6 F) and correspondingly enhancing PO (Fig. 6 C). This effect is negated, however, when Ca2+ feedback is permitted at inhibitory as well as activating binding sites (circles in Fig. 6). As soon as a subunit becomes inhibited, it can no longer participate in channel openings, so that transition of any one of the remaining three subunits to an inactive state causes the channel to close. The probability that an inactive subunit will then bind Ca2+ from the (100) state and reactivate is small because, as discussed above, this is determined by the lingering tail of [Ca2+] as the microdomain collapses, rather than by the very high local [Ca2+] around an open channel. Due to the fast collapse, the Ca2+ tail has little probability of reopening the channel, so that similar dynamics are observed either with [Ca2+] clamped or with Ca2+ feedback (squares and circles in Fig. 6).

Modulation of Ca2+ feedback on the tetrameric IP3R by stationary Ca2+ buffer

In this section, we consider the dynamics of the multimeric IP3R model when the local Ca2+ microdomain is modulated by stationary buffer. First, we discuss an example with [IP3] = 10 μM and  μM (Fig. 5, E and F). The presence of stationary buffer results in a marked increase in open probability and a prolongation of burst durations. The distributions of open time duration and close time duration are given in Fig. 7, A and B, giving an open probability of 0.2 with a mean open time of 5.8 ms and a mean closed time of 25.3 ms. The open and closed times in Fig. 7 are short, presumably reflecting flickering between the A-state and (110) state. Experimental records would probably not resolve these brief transitions, so the apparent blip duration would primarily reflect the longer burst durations.

μM (Fig. 5, E and F). The presence of stationary buffer results in a marked increase in open probability and a prolongation of burst durations. The distributions of open time duration and close time duration are given in Fig. 7, A and B, giving an open probability of 0.2 with a mean open time of 5.8 ms and a mean closed time of 25.3 ms. The open and closed times in Fig. 7 are short, presumably reflecting flickering between the A-state and (110) state. Experimental records would probably not resolve these brief transitions, so the apparent blip duration would primarily reflect the longer burst durations.

FIGURE 7.

Distribution of open (A) and closed time durations (B) for the multimeric IP3R model with Ca2+ feedback in the presence of immobile buffer.  μM and [IP3] = 10 μM.

μM and [IP3] = 10 μM.

The actions of stationary buffer likely arise through two principal mechanisms: 1), because the stationary Ca2+ buffer causes a slowly decaying tail of free Ca2+ after channel closure, there will be an increased likelihood of binding to activating Ca2+ sites; and 2), the change in spatial distribution of Ca2+ around an open channel may differentially affect binding to the inhibitory sites depending on their distance from the channel pore.

The binding of Ca2+ to sites on an inactive subunit of an open channel is expected to be highly sensitive to the location of the sites on the IP3R in relation to the pore. For example, if a binding site were closely adjacent to the pore, it would sense the peak of the [Ca2+] microdomain (∼400 μM), whereas if it were at the edge of the IP3R molecule at a distance R ∼ 15 nm from the pore, the resulting [Ca2+] would be only ∼30 μM. On the other hand, the spatial gradient of [Ca2+] equilibrates rapidly after closure of the channel, so that the [Ca2+] sensed by binding sites at the pore or edge of the IP3R would be closely similar during the tail of residual Ca2+ as the microdomain collapses.

We show in Fig. 8 how the channel dynamics are affected by the presence of stationary buffer ST when the activating and inhibitory binding sites are located at either the pore or the edge of the IP3R. Fig. 8, A–C, plots simulation data as functions of ST with [IP3] fixed at 10 μM. One general result is that the mean channel closed time τc shortens markedly as ST is raised from ∼100 to 1000 μM (Fig. 8 A), resulting in a corresponding increase in Po (Fig. 8 C), since the mean open time To shows only slight dependence on buffer concentration (Fig. 8 B). The multimeric IP3R model thus shows qualitatively similar behavior to the simplified monomeric model, in that the slowing of [Ca2+] decay after channel closure promotes binding to activating Ca2+ sites and hence increases the probability of reopening. A second major finding is that, at any given ST, the channel dynamics are highly sensitive to the location of the inhibitory Ca2+ binding site, but are almost independent on the location of the activating site. This follows because inhibition is manifest primarily by the steep spatial gradient of Ca2+ around an open channel acting on an inactive subunit In contrast, the lack of sensitivity of channel dynamics to the position of the activating Ca2+ binding site may be explained by two reasons: 1), during a burst, the reopening of the channel results mainly as subunits transition from the (110) state to the active state, independent of [Ca2+]; and 2), initiation of new bursts typically occurs after relatively long interburst intervals when the Ca2+ microdomain has collapsed so that little spatial gradient of [Ca2+] remains around the channel.

FIGURE 8.

Modulation of multimeric IP3R model dynamics by stationary buffer. (A–C) Panels show, respectively, the mean closed time  mean open time

mean open time  and mean open probability

and mean open probability  as functions of

as functions of  (D–F) Corresponding changes in channel dynamics as functions of Ca2+ binding rate to immobile buffer at

(D–F) Corresponding changes in channel dynamics as functions of Ca2+ binding rate to immobile buffer at  μM. Here [IP3] = 10 μM. In all cases, Ca2+ feedback is operational, with the activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites located either at the channel pore (

μM. Here [IP3] = 10 μM. In all cases, Ca2+ feedback is operational, with the activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites located either at the channel pore ( ) or at the edge of the IP3R (

) or at the edge of the IP3R ( ). Specifically, stars represent both activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites at

). Specifically, stars represent both activating and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites at  nm; circles represent activating binding sites at

nm; circles represent activating binding sites at  nm and inhibitory sites at

nm and inhibitory sites at  nm; squares represent activating sites at

nm; squares represent activating sites at  nm and inhibitory sites at

nm and inhibitory sites at  nm; and triangles represent both active and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites at

nm; and triangles represent both active and inhibitory Ca2+ binding sites at  nm.

nm.

In Fig. 8, D–F, the channel dynamics are plotted as functions of binding and unbinding rates of immobile buffer with ST fixed at 300 μM. The dissociation constant  is fixed at 2 μM while the on and off binding rates are correspondingly altered. Our simulation results indicate that the channel dynamics are relatively insensitive to the changes in immobile buffer kinetics across a range of binding rates.

is fixed at 2 μM while the on and off binding rates are correspondingly altered. Our simulation results indicate that the channel dynamics are relatively insensitive to the changes in immobile buffer kinetics across a range of binding rates.

Fig. 9, A–C, shows the channel dynamics as a function of [IP3] at the presence of ST = 300 μM. The open probability increases with the increase of [IP3], reaching saturation at about [IP3] = 5 μM. As a comparison, Fig. 6 C (open circles) indicates that the open probability becomes saturating at about [IP3] = 0.5 μM in the absence of any Ca2+ buffers. Fig. 9 also shows that a larger Po is obtained for the channel with all Ca2+ binding sites at channel edge.

FIGURE 9.

Tetrameric IP3R model dynamics as a function of [IP3] in the presence of stationary buffer. (A–C) Panels show, respectively, the mean closed time  mean open time

mean open time  and mean open probability

and mean open probability  as functions of [IP3] at

as functions of [IP3] at  μM. The same notations as in Fig. 8 are used here.

μM. The same notations as in Fig. 8 are used here.

Modulation of Ca2+ feedback on the tetrameric IP3R by mobile Ca2+ buffer

We finally discuss how the dynamics of the tetrameric IP3R model are modulated by introduction of mobile buffer in the presence of stationary buffer for cases where the activating and inhibitory binding sites are located at either the pore or the edge of the IP3R. Fig. 10 shows simulation data as functions of the diffusion coefficient of the mobile buffer  for a fixed concentration MT = 300 μM (Fig. 10, A–C), and as functions of MT with

for a fixed concentration MT = 300 μM (Fig. 10, A–C), and as functions of MT with  μm2/s (Fig. 10, D–F). In the simulation, [IP3] = 10 μM and

μm2/s (Fig. 10, D–F). In the simulation, [IP3] = 10 μM and  μM.

μM.

FIGURE 10.

Modulation of multimeric IP3R model dynamics by mobile buffer. (A–C) Panels show, respectively, the mean closed time  mean open time

mean open time  and mean open probability

and mean open probability  as functions of diffusion coefficient of the mobile buffer

as functions of diffusion coefficient of the mobile buffer  for

for  = 300 μM. (D–F) Corresponding changes in channel dynamics as functions of mobile buffer concentration

= 300 μM. (D–F) Corresponding changes in channel dynamics as functions of mobile buffer concentration  for

for  = 15 μm2/s. [IP3] = 10 μM. The same notations as in Fig. 8 are used here.

= 15 μm2/s. [IP3] = 10 μM. The same notations as in Fig. 8 are used here.

Fig. 10, A–C, shows that the mobile buffers with increasing  causes a progressive increase of mean open and closed times. Because the effect on closed time is greater, the open probability decreases with increasing

causes a progressive increase of mean open and closed times. Because the effect on closed time is greater, the open probability decreases with increasing  While the channel is open, Ca2+ ions that have permeated the channel may bind to either the immobile buffers or the mobile buffers. As a result of its immobility, a much steeper gradient will be established for Ca2+-bound immobile buffers than for Ca2+-bound mobile buffers. Once the channel closes, the lingering tail of [Ca2+] around the channel will result mainly from the release of Ca2+ ions from Ca2+-bound immobile buffers. Conversely, mobile buffers will act as a “‘shuttle”, tending to distribute free Ca2+ more homogeneously in the cytosolic space. Thus, mobile buffers with greater diffusion coefficient will cause the [Ca2+] tail to collapse more rapidly, generating a smaller open probability (Fig. 10 C).

While the channel is open, Ca2+ ions that have permeated the channel may bind to either the immobile buffers or the mobile buffers. As a result of its immobility, a much steeper gradient will be established for Ca2+-bound immobile buffers than for Ca2+-bound mobile buffers. Once the channel closes, the lingering tail of [Ca2+] around the channel will result mainly from the release of Ca2+ ions from Ca2+-bound immobile buffers. Conversely, mobile buffers will act as a “‘shuttle”, tending to distribute free Ca2+ more homogeneously in the cytosolic space. Thus, mobile buffers with greater diffusion coefficient will cause the [Ca2+] tail to collapse more rapidly, generating a smaller open probability (Fig. 10 C).

Fig. 10, D–E, show that increasing mobile buffer concentrations are associated with increasing mean open and closed times. However, in contrast to the effects of stationary buffer, the effects on open and closed times more closely parallel one another, so that the open probability changes only slightly (Fig. 10 F).

DISCUSSION

We describe stochastic simulations aimed at understanding how the gating of a single IP3R channel is modulated by feedback of Ca2+ ions that pass through the channel and bind to activating and inhibitory sites on the cytosolic face of the receptor. There are rather few published experimental observations of blips, and in particular no quantitative data are available regarding their kinetics. Thus, our object was not to generate a model that replicated experimental data, but principally to gain an understanding of the mechanisms that underlie their generation.

As with any simulation study (20,21), our conclusions are highly dependent upon the initial premises regarding the structure of the model: in particular that ligand binding to IP3R subunits is locked when they are in an active configuration, and that opening of the tetrameric receptor/channel may occur when either three or four subunits are active. Nevertheless, these assumptions appear well grounded (34,39), and predictions of how the channel dynamics are affected by Ca2+ feedback may be tested by comparing experimental single-channel data obtained using Ca2+ or other ions as the charge carrier.

To facilitate analysis, we first considered a simple IP3R model composed from a single subunit, and show that freely diffusing Ca2+ ions exert negligible effects on channel dynamics despite the very high local Ca2+ concentrations attained while the channel is open. The reason lies in our assumption that channel opening involves a conformational change of the subunit to an active state wherein it is locked to binding or dissociation of ligands so that Ca2+ binding cannot occur to either the activating or inhibitory sites while the channel is open. This conformational step is analogous to the well-characterized behavior of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (45), and is consistent with observations of ligand-independent flickering of the IP3R channel to the closed state (22) and the lack of effect of changes in Ca2+ concentration on gating of already open IP3R channels (46).

Feedback by permeating Ca2+ ions is thus restricted to whatever residual Ca2+ remains adjacent to the IP3R after the channel has closed and the subunit has transitioned to an inactive state. If Ca2+ ions diffuse freely, the residual microdomain collapses so rapidly that the probability of binding is slight. However, in an intracellular environment, typically only a few percent of cytosolic Ca2+ ions are free, with a large fraction being bound reversibly to immobile buffers (47). Addition of immobile buffer to the cytosolic space of our model greatly slows the decline of local [Ca2+] after channel closure, since it acts as a sink to absorb Ca2+ while the channel is open, but subsequently as a source after the channel closes. The lingering tail of residual Ca2+ thus promotes long bursts of channel activity with reopenings triggered by binding to the high-affinity activating site, whereas the local concentration of [Ca2+] during the tail is too small to cause appreciable binding to the low-affinity inhibitory site. Thus, the overall effect of stationary buffer is to produce a pronounced increase in mean open probability.

The results obtained with the above simplified monomeric model would be generally applicable also to the known tetrameric structure of the IP3R (4) if channel opening required that all four subunits be in the active conformation. However, we have argued previously (39) that experimental data are best accounted for by assuming that the channel may open if either three or four subunits are active. That property introduces further complexity into the actions of Ca2+ feedback on the receptor, because openings that involve only three subunits now expose the activating and inhibitory sites on the remaining (inactive) subunit to binding driven by the extremely high local [Ca2+] around the open pore. The resulting dynamics depend on the balance between binding to the activating and inhibitory sites, which, in turn, depends on their distances from the channel pore.

Distinct from the effect of immobile buffer to increase the channel open probability by building up a lingering [Ca2+] tail, we show that freely mobile buffer acts as a shuttle tending to distribute Ca2+ ions more homogeneously and causing the residual [Ca2+] tail to collapse more rapidly after channel closure, thereby decreasing the channel open probability.

Since the molecular architecture of the receptor is poorly characterized with respect to the locations of Ca2+ binding sites (4), we explored the extreme cases of locating each site either immediately adjacent to the pore, or at a distance of 15 nm corresponding roughly to the radius of the IP3R molecule (2). Our results indicate that Ca2+ feedback on the multimeric IP3R model is highly sensitive to the location of the inhibitory Ca2+ binding site. Because of its low affinity, Ca2+ binding is appreciable only within the peak of the microdomain around an open channel, and is negligible after channel closure. An inhibitory site located near the pore of an inactive subunit thus rapidly binds Ca2+ while the channel is open and, coupled with the slow rate for dissociation, ensures that one subunit in the tetramer is predominantly in an inhibited state. On the other hand, location of the inhibitory site at the edge of the IP3R appreciably reduces the likelihood of inhibitory Ca2+ binding, thereby increasing the probability that a subunit that enters the (100) state while the channel is still open will rapidly bind Ca2+ at the activating site and return to the active configuration rather than becoming inhibited.

The multimeric IP3R model thus displays two forms of Ca2+ feedback activation: i), feedback by residual Ca2+ by binding to activating sites on inactive subunits after the channel has closed, which is significant only in the presence of stationary buffers; and ii), feedback on the activating site of a single inactive subunit of an open channel by Ca2+ ions directly flowing through that channel. In both of these cases, the location of the activating Ca2+ site—in contrast to the inhibitory site—is inconsequential. This follows because the affinity of the activating site is sufficiently high so that binding is effectively saturated over distances of many tens of nm from the pore while a channel is open; whereas after closure the spatial gradient of the residual microdomain rapidly flattens, so there is little difference in [Ca2+] across the dimensions of a single IP3R molecule.

Swillens et al. (33) previously considered the behavior of a monomeric IP3R model within a cytosol-like environment, and proposed that the relatively long durations of single-IP3R blip events observed by intracellular imaging (6) could be reconciled with the much shorter open channel times recorded in bilayer and patch-clamp systems (13,48) because the high concentration of Ca2+ at the channel mouth just after closure promotes rebinding that leads to prolonged bursts of activity. Our simulations show that the burst dynamics can still be observed even for the IP3R model in which a conformational change has been considered before the IP3R opens. Furthermore, we demonstrate the crucial importance of stationary intracellular buffers in modulating the calcium feedback, and reveal further complexities in channel function when considering a full, tetrameric IP3R structure.

The cellular environment contains, of course, not just a single IP3R, but myriad receptors, packed in a densely clustered organization (4). Ca2+-mediated interactions between these receptors underlie the complex patterns of local Ca2+ puffs and global cellular waves signals, and will differ markedly from self-feedback on an isolated IP3R in that neighboring closed channels will be sensitive to Ca2+ flux through an open channel that is insensitive to its own Ca2+. Such complex spatiotemporal interactions are the focus of our current efforts using finite element algorithms (34) to extend our IP3R model to the multiscale environments of channel clusters, aimed at explaining phenomena including the recruitment (25) and termination of IP3R (49) during Ca2+ puffs and the lateral inhibition of IP3R (46).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM65830 and GM48071. J.S. also acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation of China under grant No. 10775114.

APPENDIX A: THE DEPENDENCE OF PO ON [IP3] FOR THE MONOMERIC IP3R MODEL

The probability of the monomeric IP3R existing in state (ijk) or (A) is denoted by  or

or  with

with  By the mass action kinetics, the equations describing the subunit dynamics are written (39):

By the mass action kinetics, the equations describing the subunit dynamics are written (39):

|

(A1) |

where Q is the generator matrix of transition rates and P is the vector of probability of subunits. The open probability for an IP3R is then given by:

|

(A2) |

Mathematically, the equilibrium state is defined by  The equilibrium vector w satisfies

The equilibrium vector w satisfies  according to the transition matrix theory (50). Detailed balance is imposed so we can solve for w by inspection (51). This is done by calculating all probabilities in terms of their probability relative to state (000). These unnormalized probabilities are denoted

according to the transition matrix theory (50). Detailed balance is imposed so we can solve for w by inspection (51). This is done by calculating all probabilities in terms of their probability relative to state (000). These unnormalized probabilities are denoted  with

with  Then

Then

|

(A3) |

where each component ( ) gives the equilibrium probability for state (ijk). Z is the normalization factor defined by

) gives the equilibrium probability for state (ijk). Z is the normalization factor defined by  The equilibrium probability (

The equilibrium probability ( ) of state (ijk) relative to that of state (000) is just the product of forward to backward rates along any path connecting (000) to (ijk). Thus we can write

) of state (ijk) relative to that of state (000) is just the product of forward to backward rates along any path connecting (000) to (ijk). Thus we can write

|

(A4) |

Thus the open probability is expressed as

|

(A5) |

with

|

(A6) |

resulting in a dependence of PO on [IP3] as shown by the solid curve in Fig. 4 A.

APPENDIX B: THE CUMULATIVE PROBABILITY FOR THE MONOMERIC IP3R MODEL

To calculate the cumulative probabilities of Ca2+ binding to the activating sites or inhibitory sites (Fig. 4, B and C), we compute the time duration of the IP3R channel from the moment of channel closing (i.e., from state A to state 110) to the moment of the first event that a Ca2+ ion binds to the activating binding site (i.e., from state 100 to state 110, or from state 000 to state 010) or binds to the inhibitory binding site (i.e., jumping to state 111, 101, 011, or 001). In the simulation  events are simulated and the statistical distributions of time duration for Ca2+ activation and inhibition can be calculated. The cumulative probabilities of activation and inhibition are then obtained with an integral process for the time duration distributions from duration 0 to a certain time interval.

events are simulated and the statistical distributions of time duration for Ca2+ activation and inhibition can be calculated. The cumulative probabilities of activation and inhibition are then obtained with an integral process for the time duration distributions from duration 0 to a certain time interval.

In the case of clamped [Ca2+], we have fixed [Ca2+] at 0.05 μM. In the case of considering Ca2+ feedback with or without buffer, we simply assume that a steady state of Ca2+ distribution has always been achieved before the channel closes. Thus, once the channel closed, the Ca2+ concentration collapses with time along a fixed path in the absence or in the presence of buffer, respectively

APPENDIX C: THE DEPENDENCE OF PO ON [IP3] FOR THE TETRAMERIC IP3R MODEL

For the tetrameric IP3R model, the channel opens when three out of four subunits are in the active state, so

|

(A7) |

Because channel states (A, A, A, not-A) are the only open states that connect to closed channel states by any one of three A-states changing to the closed state 110 with rate  we can directly write the equilibrium probability flux between open and closed states as follows:

we can directly write the equilibrium probability flux between open and closed states as follows:

|

(A8) |

The mean open and closed times are given by

|

(A9) |

The mean  (∼4.5 ms given in Fig. 6 B with solid squares) remains almost constant because at [Ca2+] = 0.05 μM,

(∼4.5 ms given in Fig. 6 B with solid squares) remains almost constant because at [Ca2+] = 0.05 μM,  is given by

is given by  and is thus very small in comparison to

and is thus very small in comparison to  ms.

ms.

Editor: Arthur Sherman.

References

- 1.Bezprozvanny, I. 2005. The inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Cell Calcium. 38:261–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor, C. W., P. C. da Fonseca, and E. P. Morris. 2004. IP3 receptors: the search for structure. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:210–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge, M. J. 1993. Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling. Nature. 361:315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foskett, J. K., C. White, K. H. Cheung, and D. O. Mak. 2007. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol. Rev. 87:593–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bootman, M., E. Niggli, M. Berridge, and P. Lipp. 1997. Imaging the hierarchical Ca2+ signalling system in HeLa cells. J. Physiol. 499:307–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker, I., J. Choi, and Y. Yao. 1996. Elementary events of InsP3-induced Ca2+ liberation in Xenopus oocytes: hot spots, puffs and blips. Cell Calcium. 20:105–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker, I., and Y. Yao. 1996. Ca2+ transients associated with openings of inositol trisphosphate-gated channels in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 491:663–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker, I. and Y. Yao. 1991. Regenerative release of calcium from functionally discrete subcellular stores by inositol trisphosphate. Proc. R. Soc. Lon. B. 246:269–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun, X. P., N. Callamaras, J. S. Marchant, and I. Parker. 1998. A continuum of InsP3-mediated elementary Ca2+ signalling events in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 509:67–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callamaras, N., J. S. Marchant, X. P. Sun, and I. Parker. 1998. Activation and co-ordination of InsP3-mediated elementary Ca2+ events during global Ca2+ signals in Xenopus oocytes. J. Physiol. 509:81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bootman, M. D., M. J. Berridge, and P. Lipp. 1997. Cooking with calcium: the recipes for composing global signals from elementary events. Cell. 91:367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dellis, O., S. G. Dedos, S. C. Tovey, R. Taufiq Ur, S. J. Dubel, and C. W. Taylor. 2006. Ca2+ entry through plasma membrane IP3 receptors. Science. 313:229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bezprozvanny, I., J. Watras, and B. E. Ehrlich. 1991. Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature. 351:751–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mak, D. O., S. McBride, and J. K. Foskett. 1998. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate activation of inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ channel by ligand tuning of Ca2+ inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:15821–15825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dargan, S. L., and I. Parker. 2003. Buffer kinetics shape the spatiotemporal patterns of IP3-evoked Ca2+ signals. J. Physiol. 553:775–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dargan, S. L., B. Schwaller, and I. Parker. 2004. Spatiotemporal patterning of IP3-mediated Ca2+ signals in Xenopus oocytes by Ca2+-binding proteins. J. Physiol. 556:447–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]