Abstract

Many studies have investigated the physical cues that influence face preferences. By contrast, relatively few studies have investigated the effects of facial cues to the direction and valence of others' social interest (i.e. gaze direction and facial expressions) on face preferences. Here we found that participants demonstrated stronger preferences for direct gaze when judging the attractiveness of happy faces than that of disgusted faces, and that this effect of expression on the strength of attraction to direct gaze was particularly pronounced for judgements of opposite-sex faces (study 1). By contrast, no such opposite-sex bias in preferences for direct gaze was observed when participants judged the same faces for likeability (study 2). Collectively, these findings for a context-sensitive opposite-sex bias in preferences for perceiver-directed smiles, but not perceiver-directed disgust, suggest gaze preference functions, at least in part, to facilitate efficient allocation of mating effort, and evince adaptive design in the perceptual mechanisms that underpin face preferences.

Keywords: gaze direction, facial expression, facial attractiveness, mate preference

1. Introduction

Most previous studies of face preferences have focused on identifying physical characteristics that influence the attractiveness of faces, such as sexual dimorphism, symmetry and averageness (see Rhodes (2006) for a meta-analytic review of these studies). By contrast, relatively few studies have investigated the effects of social signals, such as gaze direction, on face preferences. Mason et al. (2005) recently found that men showed significant preferences for direct (versus averted) gaze in women's faces with neutral expressions, but that women's attractiveness ratings of direct and averted gaze versions of women's neutral faces did not differ significantly.1 Although Mason et al. (2005) interpreted these findings as reflecting an opposite-sex bias in attraction to direct gaze, without assessing responses to male faces their study can reveal only sex differences in gaze preferences for female faces. In other words, the possibility that men generally demonstrate stronger attraction to direct gaze than women do cannot be discounted (i.e. men may rate direct gaze as more attractive than women do for judgements of both men's and women's faces). Additionally, since Mason et al. (2005) tested only preferences for direct gaze in women's faces, it is unclear whether both men and women demonstrate opposite-sex biases in attraction to direct gaze or if the opposite-sex bias in gaze preference is significantly stronger in men and/or potentially absent in women. Since gaze direction signals the direction of others' social attention (Adams & Kleck 2003; Mason et al. 2005; Jones et al. 2006), an opposite-sex bias in the strength of preferences for direct gaze may function to facilitate efficient allocation of mating effort. Mating effort is a finite resource that should be allocated judiciously (Low 2000) and preferences for direct gaze in opposite-sex faces would increase the likelihood of allocating mating effort to potential mates who are most likely to reciprocate (i.e. those who are already allocating social attention to the perceiver, Clark 2005; Mishra et al. 2007).

Although gaze direction signals the direction of others' attention, it provides little information about the valence of their attitudes and intentions (Jones et al. 2006). Interpreting others' intentions from facial cues may, therefore, require integrating information about the direction of their social attention and their emotional state/intentions (Adams & Kleck 2003; Clark 2005; Jones et al. 2006, 2007; Mishra et al. 2007). Indeed, Clark (2005) found that both men and women preferred video clips of proceptive (i.e. inviting) behavioural displays in opposite-sex individuals to unreceptive behavioural displays, particularly when the behaviour appeared to be directed at the viewer. Thus, if preferences for direct gaze function to facilitate efficient allocation of mating effort, preferences for direct gaze may be modulated not only by the sex of the face (opposite-sex versus own-sex) but also by cues to the valence of the target's attitudes and intentions (Clark 2005; Mishra et al. 2007). For example, preferences for direct gaze may be stronger when the target is smiling (signalling positive interest in the viewer) than when they appear disgusted (signalling contempt for the viewer). Furthermore, this effect of expression on the strength of preferences for direct gaze may be more pronounced for judgements of opposite-sex faces than for judgements of own-sex faces.

While previous studies have shown that gaze direction influences both the perceived intensity of facial expressions (Adams & Kleck 2003; Conway et al. 2007) and the reward value of attractive faces (Kampe et al. 2001; Jones et al. 2006), the effects of gaze direction in these studies were equivalent for judgements of own-sex and opposite-sex faces. Indeed, we know of no studies that have tested whether the strength of preference for direct gaze is modulated not only by the sex of the face judged (opposite-sex versus own-sex) but also by cues to the target individual's emotional state/intentions (unreceptive versus proceptive). Jones et al. (2006) found that preferences for colour and texture cues associated with attractiveness were stronger when judging faces that were smiling at the viewer than those that were smiling away from the viewer or were looking at the viewer with a neutral expression. As mentioned previously, Jones et al. (2006) found no evidence for a sex difference in this effect. Crucially, however, the forced-choice nature of Jones et al.'s paradigm meant that participants' preferences for direct versus averted gaze were never measured.2 Thus, although Jones et al.'s findings showed interactions among physical attractiveness and the direction and valence of others' social interest when forming face preferences, since preferences for gaze direction were not assessed and only female faces were judged, their findings are unable to offer any insight into possible opposite-sex biases in attraction to perceiver-directed versus other-directed smiles.

In light of the above, we compared the strength of preferences for direct gaze under four different conditions when judging own-sex faces with happy expressions, own-sex faces with disgusted expressions, opposite-sex faces with happy expressions, and opposite-sex faces with disgusted expressions. If preferences for direct gaze function to facilitate efficient allocation of mating effort, we predicted that both men and women would show stronger preferences for direct gaze in happy faces than in disgusted faces. Moreover, we predicted that this effect of expression on the strength of preferences for direct gaze would be stronger for judgements of opposite-sex faces (i.e. mate-choice relevant stimuli) than for judgements of own-sex faces (i.e. mate-choice irrelevant stimuli).

While many researchers have noted that opposite-sex biases in attraction to facial cues suggest adaptive design in face preferences (e.g. Little & Jones 2003; Rhodes 2006), context sensitivity in attractiveness judgements can also suggest adaptive design (Little et al. 2002; DeBruine 2005). For example, preferences for facial masculinity (Little et al. 2002) and aversions to facial cues of kinship (DeBruine 2005) are stronger when women judge men's faces for contexts that primarily consist of a strong sexual or mating component and for which pro-social regard is thought to be relatively unimportant (e.g. attractiveness for a short-term relationship) than when women judge men's faces for contexts that include both strong components of pro-social regard and sexual attraction (e.g. attractiveness for a long-term relationship). Attraction to direct gaze could reflect a mechanism for allocating mating effort efficiently and/or for efficient allocation of more general social effort. Context sensitivity of gaze preferences, whereby direct gaze preferences are stronger for contexts with a sexual component than those without, would suggest that allocation of mating effort has exerted selection pressure on the development of gaze preferences (although a lack of context specificity would not be evidence against such a selection pressure). Consequently, in study 1 we assessed the strength of participants' preferences for direct gaze using attractiveness judgements of faces (which can include a strong sexual or mating component when judging opposite-sex faces, Rhodes (2006)), while in study 2 we assessed the strength of participants' preferences for direct gaze using likeability judgements (which do not necessarily include such a strong sexual or mating component when judging opposite-sex faces and may be driven primarily by pro-social regard rather than sexual attraction, Mason et al. 2005). Mason et al. (2005) have previously shown that both men and women perceived women with neutral expressions and direct gaze as more likeable than those with averted gaze, but that only men judged women with direct gaze as more attractive than those with averted gaze. If preferences for direct gaze function to facilitate efficient allocation of mating effort, we predicted that the effects of sex of face judged and facial expression described above would occur when faces were judged for attractiveness, but that the opposite-sex bias would not necessarily occur when faces were judged for likeability.

2. Study 1

In study 1 we compared attraction to direct gaze when judging own-sex faces with happy expressions, own-sex faces with disgusted expressions, opposite-sex faces with happy expressions and opposite-sex faces with disgusted expressions. We undertook these comparisons in two different samples of participants. One sample was tested in the laboratory and the other was tested online.

(a) Material and methods

(i) Stimuli

First we manufactured male and female composite (i.e. averaged) faces with disgusted and happy expressions. Using well-established methods for manufacturing composite faces that have been used in many previous studies of face perception (e.g. Perrett et al. 2002; DeBruine et al. 2005; Jones et al. 2005), we averaged the shape, colour and texture information from full-face photographs of six males and six females randomly selected from the Karolinska Directed Emotional Faces (KDEF) image set (Lundqvist & Litton 1998) to produce male and female composites (see Tiddeman et al. (2001) for technical details of this method). This was done separately for each expression (disgusted and happy) using the same 12 identities. All images used to manufacture these expression composites had direct gaze.

Following Jones et al. (2006), versions of each of the expression composites with averted gaze were manufactured by transforming the position of the irises by 100% of the differences in shape between an average of 20 faces with direct gaze and an average of the same faces in which the position of the irises had been shifted to the left. This method for manipulating gaze direction in face images ensures that the magnitude of the change in gaze direction is identical for each expression and that versions of the same expression with direct and averted gaze differ only in the position of the irises (Jones et al. 2006). Examples of face images used in the study are shown in figure 1. Four pairs of composite faces were manufactured in total (each pair consisting of two face images differing only in gaze direction), representing the following conditions: male happy; female happy; male disgusted; and female disgusted. These stimuli have been used in a previous study of the intensity of facial expressions (Conway et al. 2007).

Figure 1.

Examples of smiling faces with direct and averted gaze and the interface used to assess preferences.

(ii) Stimuli calibration A (perceived emotionality)

To establish whether our composite images reliably captured the expected perceived emotionality, 46 participants (ages: M=26.09 years, s.d.=7.67; 28 women) were shown each of the eight composite images in a fully randomized order and, for each image, were asked to indicate whether the face looked disgusted, happy, fearful, sad or angry. The proportion of participants who chose the ‘correct’ emotion label (i.e. disgust for the disgusted composites and happy for the happy composites) for each image was then compared with what would be expected by chance alone using a binomial test. For each image, the proportion of participants who chose the correct label was significantly greater than chance (all p<0.001, all proportions>0.8). These findings confirm that our composite images captured facial cues to the desired emotions (disgust and happiness, respectively).

(iii) Stimuli calibration B (perceived direction of emotions)

To establish whether participants perceived the direct gaze images as directing the emotion towards the viewer, 40 participants (ages: M=25.97 years, s.d.=8.09; 22 women) were shown four pairs of images (each pair consisting of pairs of composite faces that differed only in gaze direction and were matched in terms of expression and sex) in a fully randomized order and were asked to click on the face that was ‘happier with you’ (for pairs of happy composites) or that was ‘more disgusted with you’ (for pairs of disgusted composites). The side of the screen on which any particular image was shown was also fully randomized. For each pair of images, a binomial test revealed that the proportion of participants who chose the direct gaze image was significantly greater than the chance value of 0.5 (all p<0.001, all proportions>0.77), confirming that participants perceived the direct gaze images as directing the emotion towards the viewer.

(iv) Stimuli calibration C (perceived gaze direction)

Using the same procedure we had used to test the perceived direction of emotions (stimuli calibration B), 30 participants (ages: M=25.07 years, s.d.=9.14; 19 women) were instructed to choose the face in each pair that was shown with direct gaze. For each pair of images, a binomial test showed that the proportion of participants who chose the direct gaze image was significantly greater than the chance value of 0.5 (all p<0.001, all proportions>0.95). This confirms that participants could correctly identify the images with direct gaze.

(v) Procedure

Participants in both the laboratory (N=85, age: M=19.46 years, s.d.=2.51; 57 women) and the online (N=380, age: M=21.16 years, s.d.=5.77; 279 women) samples viewed pairs of composite faces that differed only in gaze direction and that were matched in terms of sex and expression. For each pair of faces, participants were asked to choose the more attractive face. Participants were also instructed to indicate the strength of this attraction by choosing from the options ‘slightly more attractive’, ‘somewhat more attractive’, ‘more attractive’ and ‘much more attractive’ (as shown in figure 1). Trial order and the side of the screen on which any particular image was shown were fully randomized. This paradigm has been used to assess face preferences in many previous studies (e.g. Jones et al. 2005, 2006; DeBruine et al. in press). For participants in the laboratory sample, each pair of composite faces was presented twice (totalling eight trials). For participants in the online sample, each pair of composite faces was presented once (totalling four trials). All participants in the laboratory sample were undergraduate students at the University of Aberdeen. Participants in the online sample were recruited by following links from lists of online psychology studies.

(vi) Initial processing of data

Responses on the face preference test were coded using the following 0–7 scale:

0=averted gaze was judged much more attractive,

1=averted gaze was judged more attractive,

2=averted gaze was judged somewhat more attractive,

3=averted gaze was judged slightly more attractive,

4=direct gaze was judged slightly more attractive,

5=direct gaze was judged somewhat more attractive,

6=direct gaze was judged more attractive,

7=direct gaze was judged much more attractive.

The average strength of attraction to direct gaze when judging happy own-sex faces, disgusted own-sex faces, happy opposite-sex faces and disgusted opposite-sex faces was then calculated separately for each participant. Responses were coded in terms of own sex versus opposite sex for our main analyses, following previous studies that have tested for opposite-sex biases in face perception (e.g. DeBruine 2004). Additional analyses with sex of face judged coded as male versus female are reported in our electronic supplementary material.

(b) Results

One-sample t-tests comparing the strength of attraction to direct gaze with what would be expected by chance alone (i.e. 3.5) when judging own-sex faces with happy expressions, own-sex faces with disgusted expressions, opposite-sex faces with happy expressions and opposite-sex faces with disgusted expressions showed that participants judged direct gaze as being more attractive than averted gaze in each condition (laboratory sample: all t84>2.87, all p<0.006; online sample: all t379>2.08, all p<0.038).3

(i) Laboratory sample

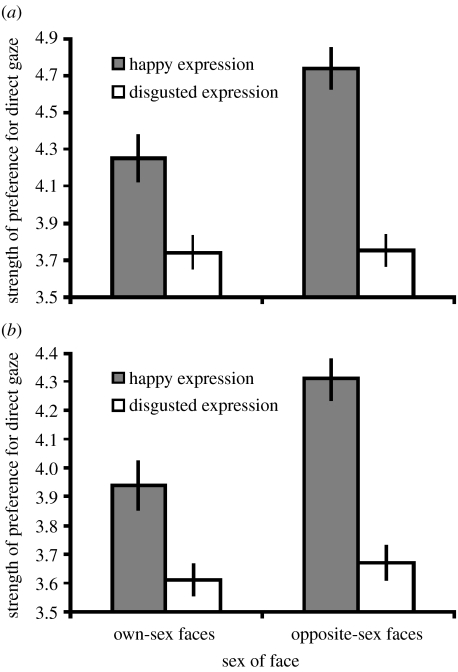

A mixed-design ANOVA (dependent variable, strength of attraction to direct gaze; between-subjects factor, sex of participant (male, female); within-subjects factors, sex of face judged (own sex, opposite sex) and expression (disgusted, happy)) was used to compare the strength of attraction to direct gaze in each condition for the laboratory sample. This analysis revealed significant main effects of sex of face judged (F1,83=6.04, p=0.016, partial η2=0.068) and expression (F1,83=69.24, p<0.001, partial η2=0.455), whereby attraction to direct gaze was generally stronger when judging opposite-sex faces than own-sex faces and when judging faces with happy expressions than faces with disgusted expressions. However, these main effects were qualified by the predicted interaction between sex of face judged and expression (F1,83=7.91, p=0.006, partial η2=0.087; figure 2a). There was no sex difference in this effect, as the three-way interaction among sex of face judged, expression and sex of participant was not significant (F1,83=0.37, p=0.546, partial η2=0.004). There was a significant two-way interaction between sex of participant and expression (F1,83=6.64, p=0.012, partial η2=0.074). The mixed-design ANOVA revealed no other significant effects (all F<0.640, all p>0.426, all partial η2<0.009).

Figure 2.

Significant interactions between sex of face judged and expression in the (a) laboratory and (b) online samples. Attraction to perceiver-directed smiles was stronger for judgements of opposite-sex than own-sex faces. There was no such opposite-sex bias in attraction to direct gaze for judgements of faces with disgusted expressions. In the y-axes, 3.5=chance (i.e. direct and averted gaze were equally attractive) and larger numbers indicate stronger attraction to direct gaze. Bars show means and s.e.m.s.

Paired-samples t-tests were then used to interpret the interaction between sex of face judged and expression. Attraction to direct gaze was stronger for judgements of happy faces than for disgusted faces in both own- (t84=3.70, p<0.001) and opposite-sex faces (t84=8.15, p<0.001). However, attraction to direct gaze in happy faces was stronger when judging opposite-sex faces than own-sex faces (t84=3.38, p=0.001). In contrast to this latter finding, there was no significant difference in the strength of attraction to direct gaze when judging own- and opposite-sex faces with disgusted expressions (t84=−0.13, p=0.899). Collectively, these analyses show that attraction to direct gaze was stronger for judgements of happy faces than disgusted faces, and that this effect of expression on the strength of attraction to direct gaze was particularly pronounced for judgements of opposite-sex faces.

We also carried out paired-samples t-tests to interpret the interaction between sex of participant and expression. Both men (paired-samples t-test: t27=7.31, p<0.001) and women (t56=4.81, p<0.001) demonstrated stronger attraction to direct gaze when judging happy faces than disgusted faces. However, this difference was greater in men than in women (independent-samples t-test: t83=2.58, p=0.012).

(ii) Online sample

To compare the strength of attraction to direct gaze in each condition in the online sample, we used an ANOVA identical to that described above. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of expression (F1,378=44.52, p<0.001, partial η2=0.105) identical to that observed in the laboratory sample. Participants also tended to demonstrate stronger attraction to direct gaze in opposite-sex faces than in own-sex faces (F1,378=2.96, p=0.086, partial η2=0.008). As in the laboratory sample, these main effects were qualified by the predicted interaction between sex of face judged and expression (F1,378=4.92, p=0.027, partial η2=0.013; figure 2b). As was also the case in the laboratory sample, this interaction was not qualified by a three-way interaction among sex of face, expression and sex of participant (F1,378=0.01, p=0.907, partial η2<0.001). There was also a significant interaction between sex of face and sex of participant (F1,378=7.77, p=0.006, partial η2=0.020). The mixed-design ANOVA revealed no other significant effects (all F<0.65, all p>0.42, partial η2<0.002).

As in the laboratory sample, paired-samples t-tests showed that attraction to direct gaze was stronger for judgements of happy faces than for that of disgusted faces in both own-sex (t379=3.60, p<0.001) and opposite-sex (t379=7.63, p<0.001) faces. Consistent with our findings from the laboratory sample, attraction to direct gaze in happy faces was also stronger when judging opposite-sex faces than own-sex faces (t379=3.78, p<0.001), but there was no opposite-sex bias when judging faces with disgusted expressions (t379=−0.74, p=0.459).

We also carried out paired-samples t-tests to interpret the interaction between sex of face and sex of participant. When the effects of facial expression were not considered (i.e. when responses were averaged across happy and disgusted expressions), women demonstrated stronger attraction to direct gaze in opposite-sex faces than in own-sex faces (paired-samples t-test: t278=−4.35, p<0.001), while the averaged strength of attraction to direct gaze in own-sex and opposite-sex faces did not differ for male participants (t100=0.63, p=0.529).

(iii) Additional analyses

Additional analyses, in which face preferences were coded in terms of male versus female rather than as own-sex versus opposite-sex, are reported in our electronic supplementary material. To summarize the findings from these additional analyses, mixed-design ANOVAs revealed significant three-way interactions among sex of face judged, expression and sex of participant in both samples. Subsequent analyses that were undertaken to interpret these three-way interactions showed that preferences for direct gaze were most pronounced when judging opposite-sex faces with happy expressions. These effects were significant for both male and female participants analysed separately in the laboratory sample and for female participants in the online sample. For male participants in the online sample, however, preferences for direct gaze were stronger for judgements of smiling faces than disgusted faces, but this effect of expression did not interact with sex of face.

3. Study 2

In study 1 we found that attraction to direct gaze was stronger for judgements of happy faces than disgusted faces and that this effect of expression on the strength of attraction to direct gaze was particularly pronounced for judgements of opposite-sex faces. These effects were observed in both the laboratory and online samples. In separate analyses for male and female participants in the online and laboratory samples (see electronic supplementary material), these effects were significant except in the case of men in the online sample. It is important to note, however, that our main analysis for the online sample (see study 1) showed the interaction between expression and sex of face was not qualified by a three-way interaction including sex of participant (p=0.907, partial η2<0.001). Consequently, we cannot conclude that the pattern of results for male participants in the online sample was significantly different from that observed for female participants.

In study 2 we assessed the strength of participants' preferences for direct gaze using likeability judgements. If attraction to direct gaze functions to facilitate efficient allocation of mating effort, then the effect of sex of face judged on the strength of preferences for direct gaze in happy faces that was observed when participants made attractiveness judgements (which can include a strong sexual or mating component) would not necessarily be expected to occur for likeability judgements (which do not include such a strong sexual or mating component when judging opposite-sex faces and that are thought to be driven primarily by pro-social regard).

(a) Material and methods

The stimuli and procedure used in study 2 were identical to those used in study 1 (online sample) except that participants (N=242, age: M=21.59 years, s.d.=4.26; 148 women) made likeability, rather than attractiveness, judgements. Study 2 was run online. Responses were coded using the same algorithm that was used in study 1 (i.e. 0, averted gaze was judged much more likeable; 7, direct gaze was judged much more likeable).

(b) Results

One-sample t-tests comparing gaze preferences with what would be expected by chance alone (i.e. 3.5) when judging own-sex faces with happy expressions, own-sex faces with disgusted expressions, opposite-sex faces with happy expressions and opposite-sex faces with disgusted expressions showed that people perceived faces with direct gaze as being more likeable than those with averted gaze in each condition (all t241>3.56, all p<0.001).4

As in study 1, a mixed-design ANOVA (dependent variable, likeability of direct gaze; between-subjects factor, sex of participant (male, female); within-subjects factors, sex of face judged (own sex, opposite sex) and expression (disgusted, happy)) was used to compare the strength of preference for direct gaze in each condition. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of expression (F1,240=67.39, p<0.001, partial η2=0.219), whereby direct gaze had a stronger positive effect on perceptions of likeability when judging happy faces than disgusted faces, and no other significant effects (all F<1.31, all p>0.25, partial η2<0.005). Importantly, the interaction between sex of face judged and expression (which was significant in both the online and laboratory samples in study 1) was not significant here (F1,240=0.006, p=0.939, partial η2<0.001).

Repeating this analysis with sex of face judged coded in terms of male versus female (rather than own sex versus opposite sex) did not alter our findings, revealing only a significant main effect of expression and no other significant effects (see electronic supplementary material).

4. Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses, participants demonstrated stronger attraction to direct gaze in happy faces than disgusted faces, particularly when judging the attractiveness of opposite-sex individuals (study 1). By contrast, there was no such opposite-sex bias in preferences for perceiver-directed smiles when judging individuals' likeability5 (study 2). Since perceiver-directed smiles signal positive social interest in the viewer (Adams & Kleck 2003; Jones et al. 2006), our findings for a context-sensitive opposite-sex bias in attraction to perceiver-directed smiles suggest that preferences for direct gaze function, at least in part, to facilitate efficient allocation of mating effort. In separate analyses for male and female participants in the online and laboratory samples in study 1, these effects for a context-sensitive opposite-sex bias in attraction to perceiver-directed smiles were significant except in the case of male participants in the online sample. In the online sample, however, the interaction between expression and sex of face judged was not qualified by a significant interaction with sex of participant (p=0.907, partial η2<0.001). Consequently, we cannot conclude that the pattern of results for male participants in the online sample in study 1 was different from the pattern of results for female participants in that sample.

Perceptual bias accounts of face preferences propose that facial attractiveness is a functionless by-product of the visual recognition system (e.g. Enquist et al. 2002; Winkielman et al. 2006). However, many researchers have noted that opposite-sex biases in preferences for facial cues are difficult to explain in terms of perceptual bias alone (e.g. Penton-Voak et al. 2001; Little & Jones 2003), but are a strong prediction of accounts of face preferences that propose attractiveness judgements may function to maximize the benefits of mate choice (e.g. Little & Jones 2003; Rhodes 2006). Similarly, context-sensitive effects on face preferences, whereby preferences for facial cues of mate quality or kinship differ depending on the extent to which the question asked is interpreted in a primarily sexual manner or is interpreted as also including a pro-social component, have also been interpreted as evidence against the proposal that face preferences are functionless by-products of visual recognition system6 (Little et al. 2002; DeBruine 2005). Attractiveness judgements (study 1) can include a strong sexual or mating component (Rhodes 2006), while likeability judgements (study 2) do not include such a strong sexual or mating component and may be driven more by pro-social regard (Mason et al. 2005). Consequently, our findings for a context-sensitive opposite-sex bias in attraction to perceiver-directed smiles are difficult to explain as functionless by-products of the perceptual system and suggest that gaze preferences may function to facilitate efficient allocation of mating effort.

In both of our studies, participants preferred direct gaze to a greater extent in happy faces than in disgusted faces when judging both own- and opposite-sex faces. This general tendency to prefer direct gaze more in happy faces may partly reflect greater visibility of gaze direction in happy faces, which are characterized by ‘wide open’ eyes, than in disgusted faces, which are characterized by ‘narrowed’ eyes. While greater visibility of gaze direction in happy faces than disgusted faces may contribute to stronger general preferences for direct gaze when judging happy faces, it is important to note that it cannot explain the opposite-sex bias in attraction to perceiver-directed smiles that was observed in study 1. It also cannot explain why this opposite-sex bias occurred when faces were judged for attractiveness but not when the same faces were judged for likeability.

Collectively, our findings show that the combination of sex of face (own-sex versus opposite-sex), context (attractiveness versus likeability) and facial expression (smiling versus disgusted) can modulate the strength of preferences for direct gaze, emphasizing the complex integrative processes that underpin face preferences. Furthermore, our findings suggest that these integrative processes function, at least in part, to facilitate efficient allocation of mating effort, and evince adaptive design in face-processing mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

The procedures used in our studies were approved by the School of Psychology (University of Aberdeen) Ethics Committee.

Endnotes

Intriguingly, Mason et al. (2005) observed these effects for dynamic shifts in gaze direction but not for static faces.

Participants in Jones et al.'s study were asked to choose the more attractive face in pairs of images where the faces in each pair differed in attractiveness of colour and texture cues but were shown with identical gaze directions and expressions. Thus, Jones et al. did not assess the strength of participants' preferences for direct versus averted gaze.

In the online sample, Binomial tests showed that the proportion of participants who chose the direct gaze image as the more attractive was significantly greater than chance in each condition (all p<0.001). Corresponding analyses for the laboratory sample also showed significant preferences for the direct gaze images in each condition (p<0.001).

Binomial tests showed that the proportion of participants who chose the direct gaze image as the more likeable was significantly greater than chance in each condition (all p<0.001).

The effect sizes (partial η2) for the interactions between sex of face judged and expression in our study 1 (attractiveness) were 0.087 in the laboratory sample and 0.013 in the online sample. By contrast, the effect size (partial η2) for this interaction in study 2 (likeability) was <0.001.

We note, however, that the absence of context-sensitivity or opposite-sex biases in preferences would not be evidence against adaptationist or mate-choice explanations of facial attractiveness (e.g. Rhodes 2006) but may imply that domain-general non-sex-specific preferences are relatively low cost.

Supplementary Material

Analyses of figure 1 and figure 2

References

- Adams R.B, Jr, Kleck R.E. Perceived gaze direction and the processing of facial displays of emotion. Psychol. Sci. 2003;141:644–647. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1479.x. doi:10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1479.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, A. P. 2005 Cues of receptivity influence judgements of attractiveness. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Human Behavior and Evolution Society, Austin, Texas, June 2005

- Conway C.A, Jones B.C, DeBruine L.M, Welling L.L.M, Law Smith M.J, Perrett D.I, Sharp M, Al-Dujaili E.A.S. Salience of emotional displays of danger and contagion in faces is enhanced when progesterone levels are raised. Horm. Behav. 2007;51:202–206. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.10.002. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBruine L.M. Facial resemblance increases the attractiveness of same-sex faces more than other-sex faces. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2004;271:2085–2090. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2824. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBruine L.M. Trustworthy but not lust-worthy: context-specific effects of facial resemblance. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:919–922. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3003. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.3003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBruine L.M, Jones B.C, Perrett D.I. Women's attractiveness judgments of self-resembling faces change across the menstrual cycle. Horm. Behav. 2005;47:379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.006. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBruine, L. M., Jones, B. C., Unger, L., Little, A. C. & Feinberg, D. R. In press. Dissociating averageness and attractiveness: attractive faces are not always average. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform [DOI] [PubMed]

- Enquist M, Ghirlanda S, Lundqvist D, Wachtmeister C.A. An ethological theory of attractiveness. In: Rhodes G, Zebrowitz L.A, editors. Facial attractiveness: evolutionary, cognitive, and social perspectives. Ablex; Westport, CT: 2002. pp. 127–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.C, et al. Menstrual cycle, pregnancy and oral contraceptive use alter attraction to apparent health in faces. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:347–354. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2962. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.C, DeBruine L.M, Little A.C, Conway C, Feinberg D.R. Integrating gaze direction and expression in preferences for attractive faces. Psychol. Sci. 2006;17:588–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01749.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01749.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.C, DeBruine L.M, Little A.C, Burriss R.P, Feinberg D.R. Social transmission of face preferences among humans. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2007;274:899–903. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0205. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.0205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampe K.K, Frith C.D, Dolan R.J, Frith U. Reward value of attractiveness and gaze. Nature. 2001;413:589. doi: 10.1038/35098149. doi:10.1038/35098149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little A.C, Jones B.C. Evidence against perceptual bias views for symmetry preferences in human faces. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2003;279:1759–1763. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2445. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little A.C, Jones B.C, Penton-Voak I.S, Burt D.M, Perrett D.I. Partnership status and the temporal context of relationships influence human female preferences for sexual dimorphism in male face shape. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2002;269:1095–1103. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1984. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low B.S. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2000. Why sex matters. [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist D, Litton J.-E. Psychology section, Karolinska Institute; Stockholm, Sweden: 1998. The averaged Karolinska directed emotional faces—AKDEF. AKDEF CDROM. [Google Scholar]

- Mason M.F, Tatkow E.P, Macrae C.N. The look of love—gaze shifts and person perception. Psychol. Sci. 2005;16:236–239. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00809.x. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00809.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Clark A, Daly M. One woman's behavior affects the attractiveness of others. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2007;28:145–149. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.11.001 [Google Scholar]

- Penton-Voak I.S, Jones B.C, Little A.C, Baker S, Tiddeman B.P, Burt D.M, Perrett D.I. Symmetry and sexual dimorphism in facial proportions and male facial attractiveness. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2001;268:1617–1623. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1703. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrett D.I, Penton-Voak I.S, Little A.C, Tiddeman B.P, Burt D.M, Schmidt N, Oxley R, Barrett L. Facial attractiveness judgements reflect learning of parental age characteristics. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2002;269:873–880. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.1971. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G. The evolutionary psychology of facial beauty. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006;57:199–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190208. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiddeman B.P, Burt D.M, Perrett D.I. Prototyping and transforming facial textures for perception research. IEEE Comput. graphics Appl. 2001;21:42–50. doi:10.1109/38.946630 [Google Scholar]

- Winkielman P, Halberstadt J, Fazendeiro T, Catty S. Prototypes are attractive because they are easy on the mind. Psychol. Sci. 2006;17:799–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01785.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Analyses of figure 1 and figure 2