Abstract

The substrate and active site residues of the low-spin hydroxide complex of the protohemin complex Neisseria meningitidis heme oxygenase, HO, NmHO, have been assigned by saturation transfer between the hydroxide and previously characterized aquo complex. The available dipolar shifts allowed the quantitation of both the orientation and anisotropy of the paramagnetic susceptibility tensor. The resulting positive sign, and reduced magnitude of the axial anisotropy relative to the cyanide complex, dictate that the orbital ground state is the conventional ‘dπ’ (dxy 2(dxz, dyz)3); and not the unusual ‘dxy’ (dxz 2dyz 2dxy) orbital ground state reported for the hydroxide complex of the homologous heme oxygenase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, (Caignan, G., Deshmukh, R., Zeng, Y., Wilks, A., Bunce, R.A., Rivera, M.; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 11842-11852) and proposed as a signature of the HO distal cavity. The conservation of slow labile proton exchange with solvent from pH 7.0 to 10.8 confirms the extraordinary dynamic stability of NmHO complexes. Comparison of the diamagnetic contribution to the labile proton chemical shifts in the aquo and hydroxide complexes reveals strongly conserved bond strengths in the distal H-bond network, with the exception of the distal His53 Nε1H. The iron-ligated water is linked to His53 primarily by a pair of non-ligated, ordered water molecules which transmit the conversion of the ligated H-bond donor (H2O) to a H-bond acceptor (OH-), thereby increasing the H-bond donor strength of the His53 side chain.

Keywords: N. meningitidis heme oxygenase, magnetic anisotropy, heme electronic ground state, H-bonding

INTRODUCTION

Heme oxygenase, HO1, is a non-metal enzyme that uses protohemin, PH, as both cofactor and substrate to generate biliverdin, iron and CO.1-6 HOs are widely distributed. In mammals they maintain iron homeostasis,7 produce the precursor to the powerful antioxidant,4, 8 biliverdin, and generate CO as a potential neural messenger.8, 9 In plants and cyanobacteria, HOs generate the linear tetrapyrroles as precursors to light-harvesting pigments. 10 The HOs identified for a number of pathogeneic bacteria11-13 appear to have as their major role the “mining” of iron to infect a host. 3, 5 Two such HOs of interest here are Neisseria meningitidis, NmHO (also called HemO 12, 14, 15) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, PaHO 13, 16, 17. A common mechanism, worked out on the mammalian HOs, appears operative in the various HOs.2-4, 18 The resting-state substrate complex, HO-PH-H2O, is first reduced, after which O2 is ligated.19 Upon adding another electron and a proton, the ferric hydroperoxy species (Figure 1A) is formed 20-22 which attacks one of the meso-carbons to yield the initial meso-hydroxy-PH intermediate. The hydroperoxy species as the hydroxylation agent in HO is in contrast to the active ferryl species in cytochromes P450 and peroxidases.4, 20 The structural basis for stabilizing the hydroperoxy species and destabilizing O-O bond cleavage is of considerable current interest.22-24 While mechanistic studies are consistent with electrophilic rather than nucleophilic attack on the meso carbon, 20 a free radical contribution has not been ruled out. 6, 25

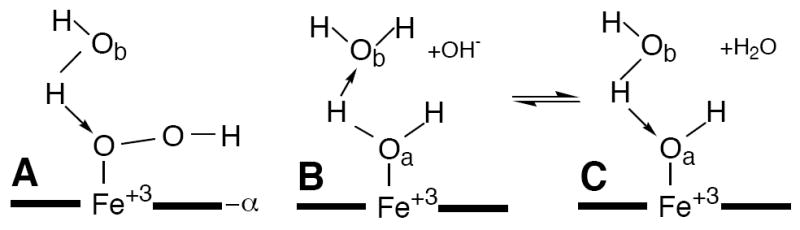

Figure 1.

Geometry of a ferric porphyrin ligated: (A) hydroperoxide; (B) neutral water molecule a; and (C) hydroxide. The latter two species are at equilibrium at any solution pH value; this equilibrium shifts to the right with increasing pH. Non-ligated water molecule (b) in the distal pocket provides the major interaction for the axially ligated water molecule 14 serving as a donor to molecule b (B). Both the hydroperoxide (A), and hydroxide (C) serve as acceptors to water b.

Due to the instability of the oxy and hydroperoxy species at ambient temperatures,22-24, 26 structural characterization by crystallography or 1H NMR, with one exception, 26 has had to resort to model complexes, ferrous HO-PH-NO15, 27 and HO-PH-CO28 and ferric HO-PH-N3 and HO-PH-CN28 for X-ray crystallography and the ferric HO-PH-CN16, 29-34 (or HO-PH-N3) complexes for NMR as models for ferrous HO-PH-O2 complex. The diverse crystal structures of mammalian27, 28, 35, 36 and bacterial14, 15, 17, 26, 37 HOs reveal a common fold where the placement of the distal helix close to the heme plane blocks three of the four meso-positions from attack by Fe+3-OOH, and steric interaction of the ligand directly with the distal helix backbone “orients/tilts” the axial ligand towards the fourth, unblocked meso-position. The crystal structures, moreover, locate a set of three conserved, non-ligated, ordered water molecules in the distal pocket that are implicated in stabilizing the Fe+3-OOH species and likely serve as the proton conduit to the active site.15, 26, 27, 36 Solution 1H NMR studies have shown31-34 that HOs possess an extended H-bond network in the distal pocket with some stronger than usual H-bonds which serve as a scaffold for not only the three “catalytically” implicated water, but also to numerous other ordered water molecules. Based on the sum rule for g values applied to the ENDOR-detected HO ferric hydroperoxy species 22 and comparison to structurally characterized model compounds, 38, 39 it has been proposed that, due to the unusual distal H-bonding interaction,6 the low-spin HO-PH-OOH complex exists in a ‘dxy’ (dxz 2dyz 2dxy) rather than the more conventional ‘dπ’ (dxy 2(dxz,dyz)3) orbital ground state, with the PH exhibiting significant ruffling.38-40 This “ruffling” in the ‘dxy’ ground state could result in large unpaired spin density (observed by 13C NMR) appearing at the meso-carbons. Such a ‘dxy’ ground state has been viewed as a unique self-activating role of PH in HOs. 6, 40

The reactive HO-PH-OOH species is sufficiently stable for spectroscopic study only at cryogenic temperatures.22-24 However, solution 13C NMR studies on PaHO-PH-OH containing 13C labeled PH revealed 40 large meso-carbon spin densities indicative 38, 39 of the dxy orbital ground state, suggesting that the HO-PH-OH complex may serve as a valid model for the unusual distal H-bond interaction that stabilizes the ‘dxy’ ground state in PaHO-PH-OOH. Confirming the dxy ground state by 13C NMR, however, requires selective 13C labeling that is readily achievable for PH,40 but would require total synthesis for modified substrates whose altered basicity would modulate41-44 the axial ligand H-bonding interaction between the distal water molecules and H-bonding network. The ‘dxy’ ground state, however, possesses additional magnetic resonance signatures which have more general applicability to diverse HO complexes. Thus the ‘dπ’ and ‘dxy’ orbital ground states differ characteristically 38, 39, 45, 46 in the sign of their axial anisotropy, Δχax. While low-spin iron(III) in either orbital state exhibits a rhombic χ tensor (or g tensor), the axial Δχax is always much larger than Δχrh by factors ~3 and dominates the dipolar fold of the iron. The determination of the sign of the axial anisotropy could be most directly determined by EPR, but would require single crystals that should allow detection at ambient temperatures. The former is difficult, the latter not possible because of the rapid electron spin relaxation at all but cryogenic temperatures. However, the sign (and magnitude) of anisotropy of χ can be directly determined by solution 1H NMR using experimental dipolar shifts, δdip, induced in the protein matrix by the anisotropic χ tensor. This shift is given by: 47-49

| (1) |

where x’, y’, z’ (R, θ’, Ω’) are proton positions in an arbitrary, iron-centered coordinate system, Δχax and Δχrh are the axial (χzz- 1/2(χxx + χyy)) and rhombic anisotropies (χxx-χyy), and Γ(α, β, γ) is the Euler rotation that converts the reference coordinates, x’, y’, z’, into the magnetic coordinate system, x, y, z, where χ is diagonal. The anisotropies and orientation of χ can be determined experimentally if sufficient experimental dipolar shifts can be assigned and valid crystal coordinates are available to generate x’, y’, z’. The anisotropy and orientation of numerous low-spin ferrihemoproteins in the conventional S = 1/2, dπ ground state have been determined and they have the common property38, 49 of large positive Δχax > 2 × 10-8 m3/mol, and much smaller rhombic anisotropies with |χax/Δχrh | ~3-4.

We have been engaged in a study of the functionally relevant molecular and electronic structural information-content of the NMR spectra for a range of paramagnetic substrate complexes of both mammalian 30-32 and bacterial 33, 34, 50 HOs. A particularly attractive candidate is the HO from the pathogeneic bacterium Neisseriae meningitidis, NmHO, a ~210 residue enzyme.3, 12 The distal ligand in NmHO complex interacts with the distal water molecules14, 15 that, in turn, interact with a series of amino acid residues, either as acceptor or donors. NmHO has the desirable properties of populating essentially a single PH orientation about the α-,γ-meso axis, that is the same in both solution 6, 34, 50 and crystals 14, 15 and which displays superior resolution that has allowed 1H NMR characterization of a significant fraction of the complex in both the low-spin34, NmHO-PH-CN, and the high-spin,50 NmHO-PH-H2O, complexes. 1H NMR spectra of only one hydroxide HO complex, PaHO-PH-OH, have been reported40 for which the heme signals were assigned by 13C labeling. No information was provided on the protein matrix that could shed light on the sign or magnitude of the magnetic anisotropy.

We report here on the thermodynamics and dynamics of the NmHO-PH-H2O ⇔ NmHO-PH-OH interconversion and provide the characterization of the electronic/magnetic properties of the latter complex. The results indicate that NmHO-PH-OH possesses large positive axial anisotropy that dictates it exists in the ‘dπ’ ground state. In addition to characterizing the electronic/magnetic properties of the NmHO-PH-OH complex, we investigate the manner in which the H-bond donor in the distal pocket responds to conversion of the axial H-bond donor, ligated water (water a in Figure 1B) to a non-ligated water b, to an axial H-bond acceptor OH- that serves as a H-bond acceptor to water b.

EXPERIMENTAL

Sample preparation

The apo-NmHO samples used in this study are the same as described in detail previously. 34 Stoichiometric amounts of protohemin, PH (Figure 2), dissolved in 0.1 M KOH in 1H2O were added to apo-NmHO in phosphate buffered (50 mM, pH 7.0). The substrate complex was purified by column chromatography on Sephadex G25 and yielded samples ~3 mM in NmHO-PH-H2O at pH 7.0. Samples in 1H2O were converted to 2H2O by column chromatography. 51 Sample pH for reference spectra in range 7.0 to 10.8 was altered by adding incremental 0.1 M KO2H in 2H2O solution to NmHO-PH-2H2O in 2H2O, 50 mM phosphate at 25°C. For long-term (>~24 h) 2D NMR spectra, samples were buffered at the desired pH with phosphate (pH 7.0 to 8.7) or bicarbonate (pH 9.1 to 10.8). The pH values in 2H2O are uncorrected for isotope effects.

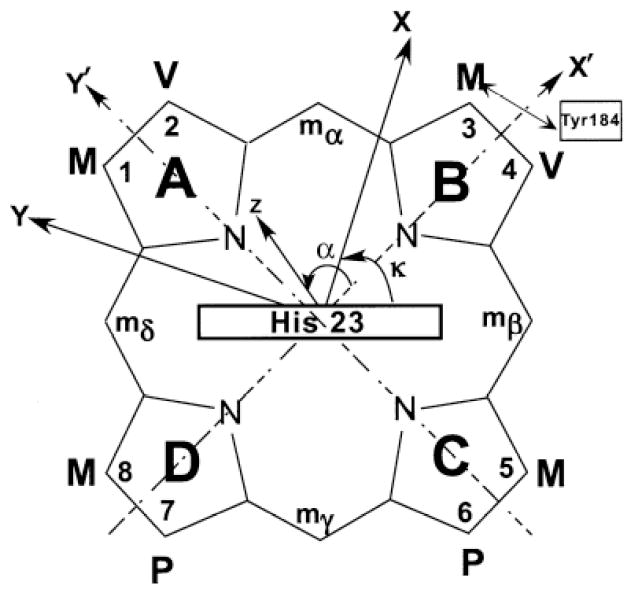

Figure 2.

Schematic structure of the heme pocket of NmHO-PH-H2O, viewed from the proximal side, showing the numbering of the protoheme (PH) skeleton, the orientation of the axial His23 imidazole plane, and the position of Tyr184 relative to pyrrole B. Also shown is the arbitrary, iron-centered reference coordinate system, x’, y’, z’, where x’, y’ are in the heme plane passing through pyrrole NB, NA, respectively and z’ points to the proximal side. The magnetic coordinate system, x, y, z, for an axially anisotropic paramagnetic susceptibility tensor, χ, where χ is diagonal, is defined by a tilt from the unique or z axis from the heme normal (z’ axis) by an angle β (not shown), and in a direction defined by the angle α between the projection of z on the x’, y’ plane and the x’ axis.

NMR spectroscopy

1H NMR data were collected on a Bruker AVANCE 500 and 600 spectrometers operating at 500 and 600 MHz, respectively. Reference spectra were collected in 2H2O over the temperature range 15-35°C at both a repetition rate of 1 s-1 over 40 ppm spectral width and at 5 s-1 over a 200 ppm band width. Steady-state, magnetization-transfer (NOE or exchange) difference spectra were generated from spectra with on-resonance, and off-resonance saturation of the desired signals; to detect exchange with H2O, selective 3:9:19 excitation was used.52 Chemical shifts are referenced to 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS) through the water resonance calibrated at each temperature. Non-selective T1s were determined by the standard inversion-recovery pulse sequence and estimated from the null point. 600 MHz NOESY 53 spectra (mixing time 40 ms; repetition rate 2 s-1) and 500 MHz Clean-TOCSY (to suppress ROESY response 54) spectra (25°, 35°C, spin lock 25 ms) using MLEV-17 55 were recorded over a bandwidth of 25 KHz (NOESY) and 12 KHz (TOCSY) with recycle times of 500 ms and 1s, using 512 t1 blocks of 128 and 256 scans each consisting of 2048 t2 points. 2D data sets were processed using Bruker XWIN software on a Silicon Graphics Indigo workstation. The processing consisted of 30°- or 45°-sine-squared-bell-apodization in both dimensions, and zero-filling to 2048 × 2048 data points prior to Fourier transformation.

Magnetic axes determination

The location of the magnetic axes was determined by finding the Euler rotation angles, Γ(α,β,γ), that rotate the crystal-structure based, iron-centered reference coordinate system, x’, y’, z’, into the magnetic coordinate system, x, y, z, where the paramagnetic susceptibility tensor, χ, is diagonal where α, β, γ are the three Euler angles. 34, 47-50 The angle β dictates the tilt of the major magnetic axis, z, from the heme normal z’, α reflects the direction of this tilt, and is defined as the angle between the projection of the z axis on the heme plane and the x’ axis (Figure 2), and κ ~ α+γ is the angle between the projection of the x, y axes onto the heme plane and locates the rhombic axes (Figure 2). In the present case, we consider the tensor to be axially symmetric, so that Δχrh = 0, and γ becomes irrelevant. The magnetic axes were determined by a least-square search for the minimum in the error function, F/n: 34, 47-50

| (2) |

with observed dipolar shift, δdip(obs) given by:

| (3) |

where δDSS(obs) and δDSS(dia) are the chemical shifts, in ppm, referenced to DSS, for the paramagnetic NmHO-PH-OH complex and an isostructural diamagnetic complex, respectively. In the absence of an experimental δDSS(dia) for the latter, it may be reasonably estimated 56, 57 from the available molecular structure 14 and available computer programs, 56, 57 as described previously for NmHO-PH-CN 34 and NmHO-PH-H2O. 50

RESULTS

pH titration

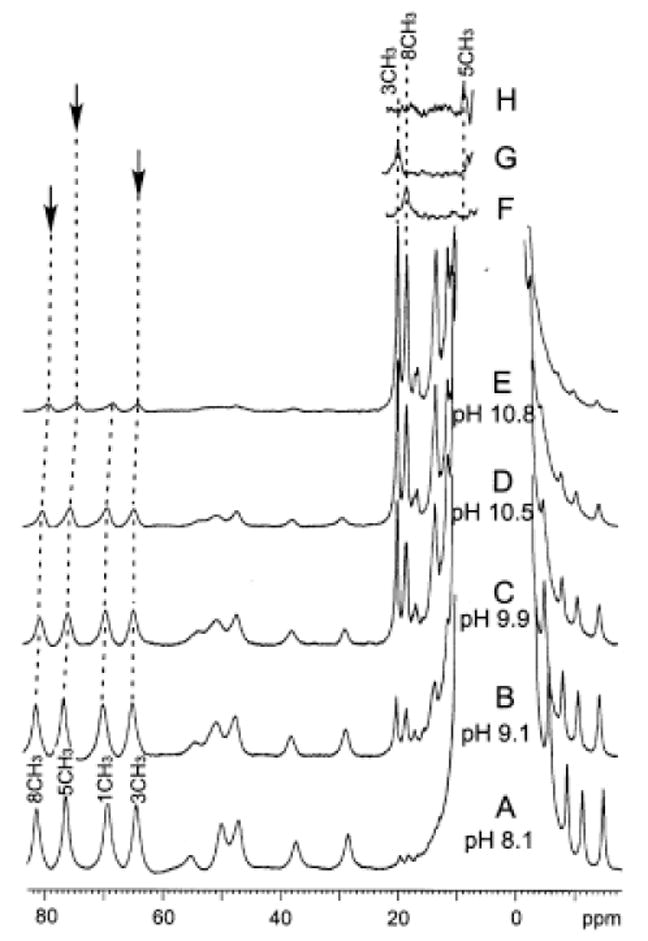

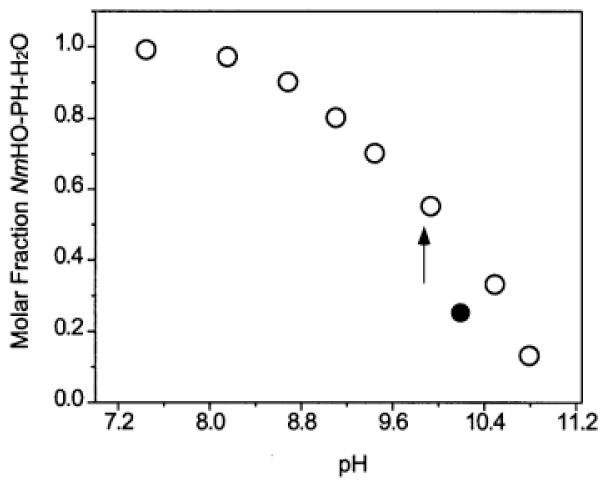

The influence of solution pH on the resolved portions of the 500 MHz 1H NMR spectra of NmHO-PH-H2O in 2H2O in the pH range 8.0-10.8 is illustrated in Figure 3. The loss of intensity in Figure 3A-3E, without concomitant line-broadening, of the assigned 50 heme methyl peaks in the 60-80 ppm window for high-spin NmHO-PH-H2O, and the appearance of two resolved, apparent heme methyl peaks in the 18-20 ppm window typical for the expected low-spin NmHO-PH-OH complex, 49 dictate that the deprotonation/protonation of the exogenous ligand is slow on the NMR time scale. 58 In concert with this observation, all signals, including ones for inconsequentially relaxed protons and with only 0.1 ppm shift difference in the two species, similarly exhibited slow exchange, indicating the exchange rate is <103 s-1. The sum of the intensities of an assigned 50 low-field heme methyl peak of NmHO-PH-H2O and that of the proposed (see below) heme methyl peak of NmHO-PH-OH in the pH titration in 2H2O remained constant relative to the intensity of the diamagnetic envelope, within the experimental uncertainty of ~15%. This dictates that only two species are detectably populated, and leads to the Henderson-Hasselbalch plot in Figure 4 (open circles). The data of the strongly alkaline pH are likely suspect due to generation of a detectable third species above pH 10.2. However, the integration of the spectra in Figure 4 in the pH range 9.1 to 10.5 allows the estimate of the pK as 9.8 in 2H2O. The single spectrum at pH 10.2 in 1H2O, results in the filled marker in Figure 4, and indicates that the pK in 1H2O is ~0.4 units lower on the pH scale, or pK(1H2O) ~9.4.

Figure 3.

Resolved portions of the 500 MHz 1H NMR spectrum of NmHO-PH-H2O/OH at 25°C as a function of solution pH. The predominant NmHO-PH-H2O complex with its assigned residues is shown at (A) pH 8.1; (B) pH 9.1; (C) pH 9.9; (D) pH 10.5 (6%:94% NmHO-PH-H2O:NmHO-PH-OH) and (E) pH 10.8. The magnetization-transfer difference spectra for NmHO-PH-OH upon saturating the assigned NmHO-PH-H2O heme methyl 50 (as indicated by vertical arrow) are shown for the (F) 8-CH3, (G) 3-CH3; and (H) 5-CH3.

Figure 4.

A Henderson-Hasselbalch plot (mole fraction NmHO-PH-OH in NmHO-PH-H2O/NmHO-PH-OH mixtures as a function of pH) in 2H2O solution, at 25°C, as determined from the relative intensities of the heme 3-CH3 signal in the two complexes. Data in 2H2O are shown as open circles. The estimated pK ~9.8 in 2H2O is shown by a vertical arrow. The single data point recorded in 1H2O solution at pH 10.2 is shown as a closed circle.

The dominant NmHO-PH-OH complex at pH 10.5 and 10.8 exhibited T1s ~8-9 ms for the two resolved low-field heme methyl peaks, and T1s ~7-10 ms for the apparent composite peak centered near 15 ppm (data not shown), which is assumed to arise from α-protons from the propionates and vinyl groups. At these alkaline pH values, exchange-transfer contributes negligibly to the effective T1s, dictating that they are the true T1s in the hydroxide complex. The upfield shoulder of the NmHO-PH-OH spectrum at pH 10.5 exhibits one rapidly relaxed single proton peak with T1s ~12 ms (not shown, see Supporting Information) that has no detectable NOESY cross peak. The upfield resonance position and relaxation rate are consistent with expectations for a vinyl Hβ.49

Heme methyl assignments for NmHO-PH-OH

Saturation of the assigned low-field methyl peaks50 for the high-spin NmHO-PH-H2O complex in 2H2O at pH 8.9 results in the saturation-transfer-difference58 spectra illustrated in Figures 3F-3H. These lead to the unambiguous assignment of the resolved 8CH3 (Figure 3F) and 3CH3 (Figure 3G) signals of NmHO-PH-OH, and locate the 5CH3 signal (Figure 3H) at the low-field edge of the aromatic envelope. Saturation of the 1CH3 peak in NmHO-PH-H2O failed to reveal any clear signal attributable to 1CH3 in NmHO-PH-H2O and it is likely under the weak off-resonance saturation of the diamagnetic envelope resulting from the strong saturation field necessary to saturate the high-spin complex peak. Hence we conclude 1CH3 is located within the 1-7 ppm window.

The effect of temperature (not shown, see Supporting Information) on the chemical shifts for the resolved NmHO-PH-OH methyl peak reveals weak Curie behavior for 3CH3 peak (apparent intercept at T-1 = 0 of 19 ppm), and weak anti-Curie behavior for the 8CH3 peak (apparent intercept at T-1 = 0 of 30 ppm).

Residue assignment protocols

All 2D spectra (both NOESY and TOCSY) with more than ~10% NmHO-PH-OH present (above pH ~8.5) exhibited cross peaks that were strongly dominated by chemical exchange between NmHO-PH-H2O and NmHO-PH-OH. This strong dominance of exchange cross peaks is obvious for resolved resonances where such cross peaks are instantly recognizable, as illustrated for the low-field spectral window in Figure 5. Brackets above the reference trace over the 2D map in Figure 5 connect the two sets of resonances (relative intensities ~3:1) for NmHO-PH-OH and NmHO-PH-H2O, where the resonances of the latter complex have been assigned previously.50 In Figure 5, as in the following Figures 6-8, direct exchange cross peaks are labeled by asterisks (*), with the NmHO-PH-OH and NmHO-PH-H2O frequencies marked by solid and dashed lines, respectively. Peaks are labeled by residue number and position, except for peptide NHs, which are labeled solely by residue number. Exchange-transferred NOESY cross peaks (i.e., an NOE to a NmHO-PH-H2O proton i, that it is transferred to the same proton, i, in the NmHO-PH-OH complex), are labeled by the pound marker (#). The NOESY spectrum in Figure 5 is dominated not only by direct exchange cross peaks (marked *), but also by exchange-transferred NOESY cross peaks (marked #) in 1H2O solution. For example, the NmHO-PH-OH His141 NδH signal at 13.35 ppm (solid lines in Figure 5A) exhibits a direct exchange cross peak not only to the Nδ1H in the NmHO-PH-OH complex at ~10.8 ppm, but also to the 141NH of NmHO-PH-H2O (marked by #) at 10.4 ppm.

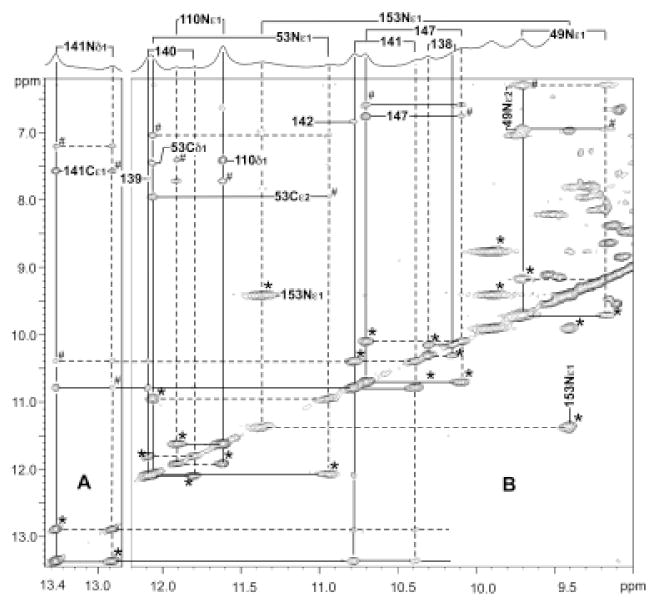

Figure 5.

Low-field resolved portion of the 600 MHz 1H NMR reference spectrum of ~20% NmHO-PH-H2O; ~80% NmHO-PH-OH in 1H2O at pH 10.2 and 25°C with bars to connect the position of the two exchanging peaks, as previously assigned for the NmHO-PH-H2O complex. (A, B) provide the pertinent portion of the 600 MHz NOESY/EXSY spectrum (mixing time 40 ms, repetition rate 2 s-1) illustrating the NOESY, and exchange (EXSY; peaks marked by *) and exchange-transferred NOESY peaks (marked by #) among the low-field labile protons. The unambiguous assignment of the labeled peaks for NmHO-PH-OH is completely dependent on the previous unambiguous assignments carried out on essentially pure NmHO-PH-H2O. 50 Again, protons in NmHO-PH-H2O are shown by dashed lines, while those in NmHO-PH-OH are shown by solid lines. Signals are identified by residue number and position, except peptide NHs, which are labeled solely by residue number.

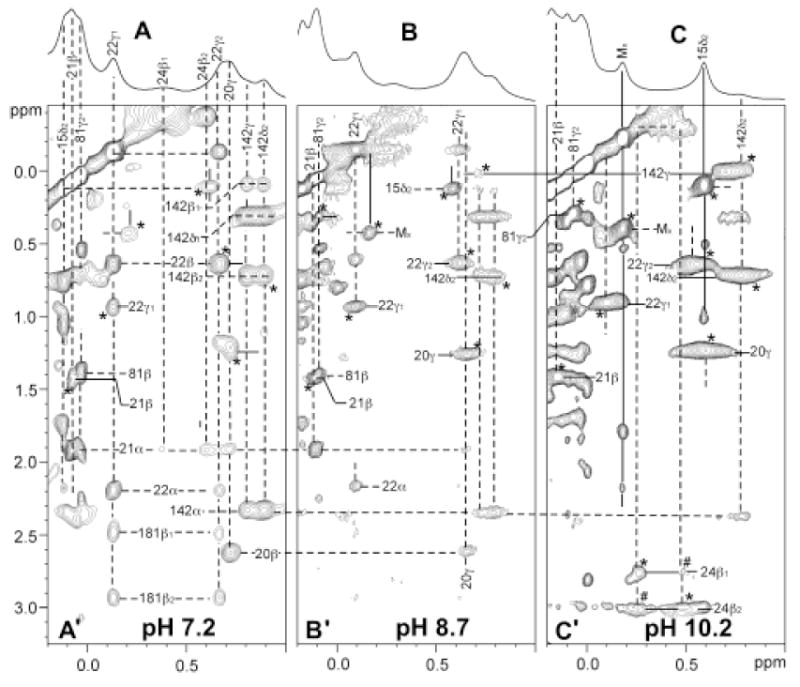

Figure 6.

Resolved upfield portion of the 600 MHz 1H NMR spectrum of NmHO-PH-H2O/OH in 2H2O at 25°C at: (A) pH 7.2; (B) pH 8.7; and (C) pH 10.2 illustrating the conversion of primarily NmHO-PH-H2O in A to primarily NmHO-PH-OH in C. The pertinent portions of the 600 MHz 1H NMR NOESY(EXSY) spectra (mixing time 40 ms, repetition rate 2 s-1) are shown in (A’), (B’), (C’) at the pH values corresponding to the reference spectra in A, B, C, respectively. Proton frequencies are labeled by residue number and position; peptide NHs are labeled solely by number. Dashed lines identify protons in NmHO-PH-H2O assigned previously, while solid lines identify newly assigned protons in NmHO-PH-OH. Asterisks identify exchange peaks and # identify exchange-transferred NOEs. Note weak exchange peak Leu15 Cδ2H3 and MX (unassigned methyls) even at pH 7.2 (A’), which become stronger at both pH 8.7 (B’) and 10.2 (C’). Also note diminishing intensity of intramolecular NOESY cross peaks within NmHO-PH-H2O, and increasing intensity of exchange cross peak between NmHO-PH-H2O and NmHO-PH-OH with increasing pH.

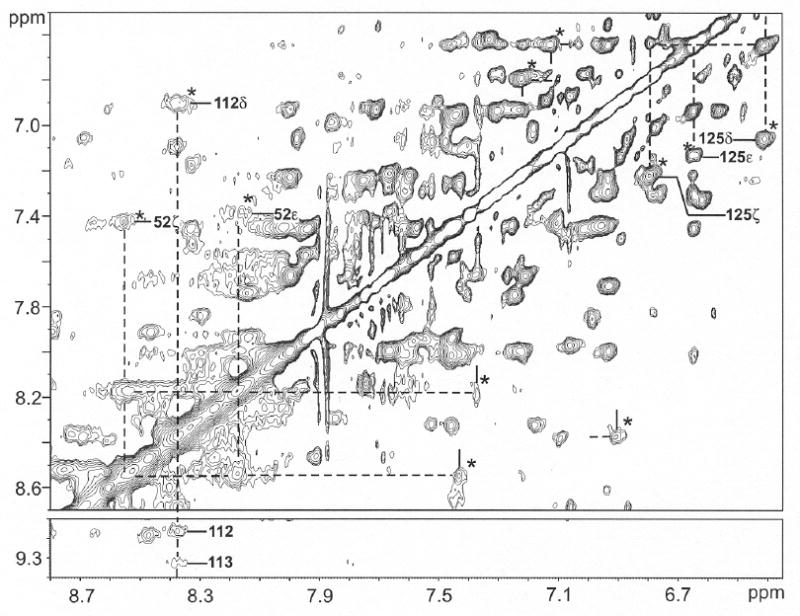

Figure 8.

Low-field portion of the 1H NMR NOESY/EXSY spectrum (mixing time 40 ms; repetition rate 2 s-1) of ~20% NmHO-PH-H2O, ~80% NmHO-PH-OH in 2H2O, 100 mM bicarbonate, at pH 10.5 and 25°C illustrating exchange (EXSY) cross peaks (marked by *) between NmHO-PH-H2O and NmHO-PH-OH for slowly exchanging labile protons Tyr112-Gln115 and Ala182-Tyr184 (A), for the His53 ring Cδ1H and Cε2H (A), Tyr184 ring proton (A) and His141 Cδ2H (C). The proton frequencies of NmHO-PH-H2O and NmHO-PH-OH are marked by dashed and solid lines, respectively. Note that the sequential Ni-Ni+1 cross peaks within NmHO-PH-OH are clearly observed for both helical fragments with slowly exchanging NHs. Panel (B) shows the intra-NmHO-PH-OH Tyr184 ring NOESY cross peaks and the expected Tyr184 CδHs to peptide NH NOESY cross peak (A). Panel (D) represents the steady-state 1D NOE difference spectrum within the NmHO-PH-OH complex resulting upon saturating the 3-CH3 of the NmHO-PH-OH complex at 20 ppm, and yields the expected NOEs to the ring of Tyr184. The NOE to the Phe52 CδH arises primarily from a very strong secondary NOE via the Tyr184 ring. Note that even at this extreme alkaline pH, EXSY cross peaks are as intense as most NOESY cross peaks.

Figures 6A-6C present the reference spectra and the pertinent portions of the NOESY spectra for the upfield resolved spectral window as a function of increasing pH. Even at pH 7.2 (~3% NmHO-PH-OH), exchange cross peaks can be detected (Figure 6A’), while at pH 8.7 (~12% NmHO-PH-OH) exchange cross peaks are as intense as any intramolecular NOESY cross peaks (Figure 6B’). At pH 10.2 (~75-80% NmHO-PH-OH; see Figure 6C’), by far the strongest cross peaks still originate from exchange. Thus with significant population of both isomers, a typical 2D map was dominated by exchange cross peaks that strongly obscure intramolecular NOESY cross peaks. It was not possible to identify a set of conditions (pH, temperature, mixing time) which provided a map that is dominated by the desired intramolecular cross peaks for the NmHO-PH-OH complex. However, the above results suggest an approach where we inspect 2D maps as a function of pH, in which the appearance of new cross peaks with increasing pH can be uniquely attributed to exchange peaks to the same proton in the NmHO-PH-OH complex.

Low-field resolved resonances in the H-bond network

Since the NmHO-PH-H2O cross peaks have been uniquely assigned50 in NmHO-PH-H2O at a sufficiently low pH that exchange cross peak intensity is negligible, the identical assignments are trivially achieved for NmHO-PH-OH complex, as shown in Figure 5. It is noted that, while most backbone NHs exhibit small to modest chemical shift differences between the two complexes, those of several side chains, particularly the His53 Nε1H and Trp153 NεH, exhibit substantial chemical shift differences. The chemical shifts for labile protons in NmHO-PH-OH are listed in Table 1, where they can be compared to the previously reported 34 values for NmHO-PH-H2O.

Table 1.

Comparison of labile proton chemical shifts for NmHO-PH-OH and NmHO-PH-H2O

|

NmHO-PH-OH

|

NmHO-PH-H2O

|

Comparison

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δDSS(obs)a | δdip(calc)b | δDSS(dia*)c | δDSS(dia*)e | Δδdip(calc)d | ΔδDSS(dia*)f | |

| Peptide NHs | ||||||

| Ala12 | 9.15 | -0.09 | 9.24 | 9.31 | 0.29 | 0.07 |

| Tyr112 | 8.36 | -0.22 | 8.58 | 8.68 | 0.72 | 0.10 |

| Cys113 | 7.75 | -0.40 | 8.15 | 8.40 | 1.35 | 0.25 |

| Ala114 | 8.70 | -0.40 | 9.10 | 9.00 | 1.33 | -0.10 |

| Gln115 | 9.40 | -0.27 | 9.67 | 9.50 | 0.78 | -0.17 |

| Gly138 | 10.30 | 0.05 | 10.25 | 10.28 | -0.18 | 0.03 |

| Ala139 | 7.67 | 0.08 | 7.59 | 7.58 | -0.30 | -0.01 |

| Arg140 | 12.10 | 0.11 | 11.99 | 12.04 | -0.37 | 0.05 |

| His141 | 10.78 | 0.15 | 10.63 | 10.75 | -0.52 | 0.12 |

| Leu142 | 6.82 | 0.27 | 6.55 | 6.68 | -0.92 | 0.13 |

| Asp147 | 10.70 | 0.12 | 10.58 | 10.60 | -0.39 | 0.02 |

| Ala180 | 8.39 | -0.11 | 8.50 | 8.42 | 0.44 | -0.08 |

| Phe181 | 8.04 | -0.12 | 8.16 | 8.03 | 0.57 | -0.13 |

| Ala182 | 7.77 | -0.02 | 7.79 | 7.97 | 0.20 | 0.12 |

| Phe183 | 8.61 | -0.08 | 8.69 | 8.65 | 0.35 | -0.04 |

| Tyr184 | 8.15 | -0.19 | 8.34 | 8.51 | 0.73 | 0.17 |

| Sidechain NHs | ||||||

| Gln49 Nε1H | 9.70 | 0.14 | 9.56 | 9.76 | -0.72 | 0.20 |

| Gln49 Nε2H | 6.97 | 0.17 | 6.80 | 7.04 | -1.00 | 0.26 |

| His53 Nε1H | 12.07 | 0.10 | 11.97 | 11.48 | -0.66 | -0.51 |

| Trp110 NεH | 11.60 | -0.08 | 11.68 | 11.70 | 0.29 | 0.02 |

| His141 Nδ1H | 13.35 | 0.12 | 13.23 | 13.24 | -0.48 | 0.01 |

| Trp153 NεH | 9.40 | -0.36 | 9.76 | 10.54 | 1.25 | 0.82 |

δDSS(obs), in ppm, referenced to DSS via the solvent signal, in 1H2O, 100 mM bicarbonate at 25°C and pH 10.2.

Dipolar shift predicted by the determined magnetic axes described in Figure 8.

The diamagnetic shift that reflects H-bonding differences between OH- and H2O complexes, as given by Eq. (4).

Δδdip(calc) = δdip(calc; NmHO-PH-H2O) - δdip(calc; NmHO-PH-OH)

As reported previously.50

High-field resolved hyperfine shifted residues

The upfield portion of the NOESY spectrum with increasing pH (Figure 6) clearly leads to the assignment in NmHO-PH-OH of each of the resolved upfield signals that had been previously assigned 50 in NmHO-PH-H2O. It is noted that in some cases, the exchange peak (marked by *) partially overlaps an intramolecular NOESY cross peak for NmHO-PH-H2O (i.e., Val22 γ2/β NOESY cross peak (Figure 6A’) and Val22 γ2 exchange cross peaks to NmHO-PH-OH (Figures 6B’, 6C’)). Moreover, the appearance of very weak cross peak at pH 7.2 (Figure 6A), which increase strongly at higher pH (Figures 6B’, and 6C’), allows the connection between the two complexes of the two resolved methyls in the NmHO-PH-OH complex (Leu15 Cδ2H3 and MX), with an unassigned methyl peak (designated Mx) at -0.22 ppm in NmHO-PH-OH, but 0.37 ppm in NmHO-PH-H2O. Since MX in NmHO-PH-OH exhibits insignificant hyperfine shifts (negligible temperature dependence), its assignment was not pursued further. The chemical shifts for residues with significant dipolar shifts (>|0.25| ppm) in NmHO-PH-OH are listed in Table 2, and the data for the remaining assigned residues are listed in Supporting Information.

Table 2.

Chemical and dipolar shift data for strongly dipolar-shifted residues in NmHO-PH-OH, NmHO-PH-H2O and NmHO-PH-CN

|

NmHO-PH-OH

|

NmHO-PH-H2O

|

NmHO-PH-CN

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δDSS(obs)a | δDSS(dia)b | δdip(obs)c | δdip(obs)d | δdip(obs)e | ||

| Ala12 | CαH | 3.39 | 3.82 | -0.42 | 0.21 | -0.52 |

| CβH3 | 1.24 | 1.45 | -0.23 | 0.42 | -0.47 | |

| Thr20 | CγH3 | 1.30 | 0.09 | 1.21 | -1.76 | 2.18 |

| Ala21 | CβH3 | 1.47 | 0.80 | 0.67 | -0.65 | 1.24 |

| Val22 | Cγ1H3 | 0.70 | -0.07 | 0.77 | -0.57 | 1.57 |

| Cγ2H3 | 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.34 | -0.48 | 1.06 | |

| Asp24 | Cβ1H | 2.82 | 2.14 | 0.58 | -2.51 | 1.51 |

| Cβ2H | 3.08 | 2.00 | 1.08 | -2.60 | 2.30 | |

| Phe52 | CεHs | 7.43 | 7.53 | -0.10 | 0.62 | -0.82 |

| CζH | 7.31 | 7.55 | -0.24 | 1.00 | -0.15 | |

| Tyr112 | CδHs | 6.90 | 7.37 | -0.47 | 0.31 | -1.16 |

| CεHs | - | - | - | 1.00 | -1.15 | |

| Cys113 | Cβ1H | 2.72 | 3.05 | -0.31 | 1.31 | -0.71 |

| Cβ2H | 2.76 | 3.29 | -0.35 | 1.01 | -0.64 | |

| Asn118 | Cβ1H | 3.12 | 2.42 | -0.70 | -2.70 | 1.50 |

| Cβ2H | 3.02 | 2.30 | -0.62 | -2.62 | 1.30 | |

| Ala121 | CβH3 | 2.30 | 0.70 | 1.60 | -4.10 | 4.8 |

| Leu142 | Cδ2H3 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.78 | -0.77 | (1.88)f |

| CγH | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.05 | -0.85 | (0.94) | |

| Trp153 | Cδ1H | 6.95 | 7.11 | -0.16 | 0.71 | -0.14 |

| Val157 | CαH | 2.85 | 3.24 | -0.39 | (0.30)g | -0.36 |

| CβH | 1.55 | -2.01 | -0.46 | (0.26) | -0.35 | |

| Cγ1H3 | 0.37 | 1.02 | -0.65 | (0.29) | -0.38 | |

| Cγ2H3 | -0.02 | 0.12 | -0.14 | (0.45) | 0.55 | |

| Phe181 | Cβ1H | 3.57 | 3.12 | 0.43 | -0.17 | 0.15 |

| Cβ2H | 3.03 | 2.84 | 0.18 | 0.32 | 0.73 | |

| Phe183 | CαH | 4.53 | 4.26 | -0.27 | 0.25 | (-0.15)g |

| Cβ1H | 3.68 | 3.37 | -0.29 | 0.30 | (-0.22) | |

| Cβ2H | 3.42 | 3.26 | -0.16 | 0.40 | (-0.14) | |

| CδHs | 7.64 | 7.75 | -0.11 | 0.21 | -0.61 | |

| CεHs | 7.37 | 7.62 | -0.25 | 0.02 | -0.26 | |

| Tyr184 | CδHs | 6.18 | 6.92 | -0.74 | 0.62 | -1.13 |

| CεHs | 6.48 | 7.07 | -0.63 | 1.00 | -1.15 | |

δDSS(obs) in ppm referenced to DSS via the solvent resonance, in 2H2O at pH 9.1, 100 mM in bicarbonate at 25°C.

Diamagnetic chemical shift in ppm, at 25°C, calculated by the ShiftX program 56 and the NmHO-PH-H2O crystal structure.

Given by Eq. (3).

As reported in Ref. 50, and converted to δdip(obs) using Eq. (3) and the same δDSS(dia) as for NmHO-PH-OH.

As previously reported in Ref. 34, and converted to δdip(obs) by Eq. (3) and the same δDSS(dia) as for NmHO-PH-OH.

Not assigned in NmHO-PH-CN; given in parentheses is the δdip(calc) from the published magnetic axes. 34

Not assigned in NmHO-PH-H2O; given in parentheses is the δdip(calc) from the published magnetic axes.50

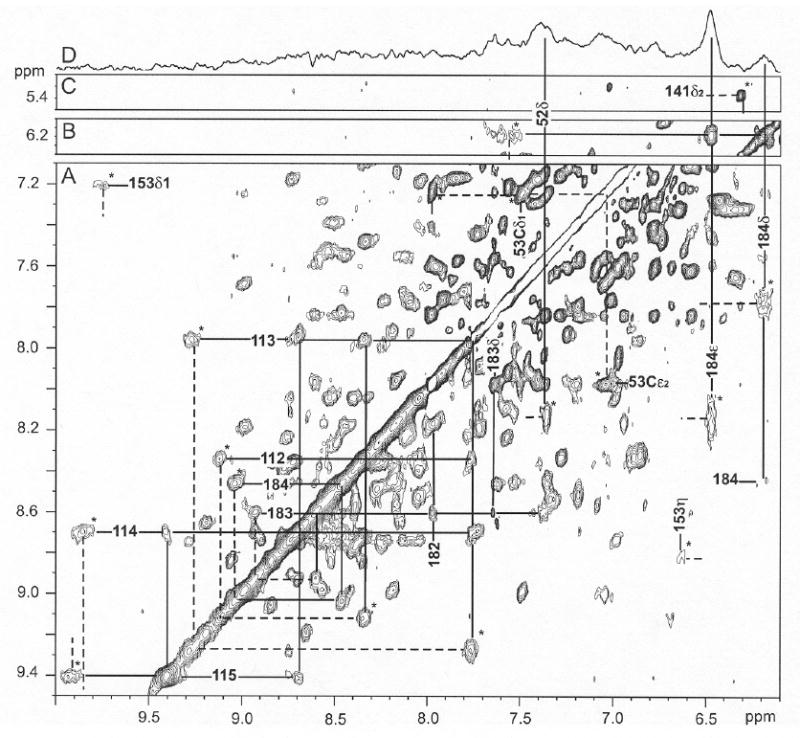

Non-resolved hyperfine-shifted resonances

Increasing the pH toward the alkaline region in 2H2O results in the detection of new cross peaks (due to exchange), and intensity increases with pH, for three key, dipolar shifted, aromatic residues assigned34 in NmHO-PH-H2O, as illustrated at pH 8.7 in Figure 7. Exchange cross peaks (marked *) from the well-resolved ring protons of Phe125 in NmHO-PH-H2O identify all of the protons in NmHO-PH-OH. Similar cross peaks are also observed for the CζH and CεHs of Phe52 (marked by *); the CδHs peak was found34 very broad in NmHO-PH-H2O, which accounts for its undetectability in Figure 7. Lastly, an exchange cross peak also identifies the Tyr112 CδH cross peak (marked by *). It is noteworthy that the various ring chemical shifts for each Phe52 and Phe125 in the NmHO-PH-OH complex are sufficiently close to each other so as to preclude the resolution of the intra-ring NOESY cross peaks in the pure NmHO-PH-OH complex. The chemical shift for residues in NmHO-PH-OH with significant dipolar shifts (> |0.25| ppm) are listed in Table 2, and the data for the remaining assigned residues are listed in Supporting Information.

Figure 7.

Aromatic proton portion of the 600 MHz 1H NMR NOESY/EXSY spectrum (mixing time 40 ms; repetition rate 2 s-1) for ~85% NmHO-PH-H2O and ~15% NmHO-PH-OH at pH 8.7 in 2H2O solution, 50 mM in phosphate at 25°C. New exchange peaks are marked by * for assigned aromatic rings in NmHO-PH-H2O and labeled for Phe52, Tyr112 and Phe125. Protons in NmHO-PH-H2O and NmHO-PH-OH are shown by dashed and solid lines, respectively.

Tyr184 ring protons exhibited very broad signals whose NOESY cross peak was marginally detectable in the NmHO-PH-H2O complex. 50 Its exchange cross peaks to NmHO-PH-OH are not detectable at pH 8.7, but at pH 10.5, where NmHO-PH-OH with narrower lines, is the dominant species, the ring exchange peaks are readily detected (Figure 8A). Seven assigned50 slowly exchanging peptide NHs of NmHO-PH-H2O in 2H2O solution (residues 112-113, 182-184) also exhibit exchange peaks at pH 10.5 to their counterparts in NmHO-PH-OH (Figure 8).

Dipolar contacts within NmHO-PH-OH

NOESY contacts among protons within the NmHO-PH-OH complex are most readily identified for protons first identified by magnetization exchange from NmHO-PH-H2O. The sequential Ni-Ni+1 contacts at pH 10.5 within the NmHO-PH-OH complex for Tyr112-Glu115 and Ala182-Tyr184 are observed (Figure 8A), once the exchange cross peaks between the H2O and OH- complexes are identified (Figure 7). Hence, these peptide NHs exhibit long 1H → 2H exchange lifetimes of over a period of several days even at pH 10.5. Also shown in Figure 8 are the exchange cross peaks for the nearly degenerate His53 ring Cδ1H and Cε2H (in NmHO-PH-H2O50) to their well-resolved positions in NmHO-PH-OH (Figure 8A), and the exchange cross peaks for the key His141 Cδ2H (Figure 8C).

The separate exchange cross peaks for the Tyr184 ring (Figure 8A), when projected to the diagonal (Figure 8B), identify the intramolecular NOESY cross peak for the Tyr184 ring within the NmHO-PH-OH complex, as well as the expected intramolecular Tyr184 CδHs to NH cross peaks (Figure 8A). Saturation of the resolved 3CH3 peak of the NmHO-PH-OH complex at pH 10.5 (Figure 8D) yields the NOE difference-spectrum with the expected cross peaks to both ring protons of Tyr184, as well as to the CδH of Phe52, whose exchange cross peak with the same ring proton in NmHO-PH-H2O (marked*) is now also observed. The 3CH3 exhibited very similar NOE patterns in both NmHO-PH-CN 34 and NmHO-PH-H2O. 50

Anisotropy and orientation of the paramagnetic susceptibility tensor χ

The magnetic anisotropy of dπ, low-spin iron(III) is large, positive 38, 45, 49 and primarily axial (|Δχax/Δχrh|~3), with Δχax ~2.5 × 10-8 m3/mol. In contrast, the magnetic anisotropy of high-spin NmHO-PH-H2O is also largely axial, 50 but negative with Δχax ~-2.0 × 10-8 m3/mol. In Table 2 we list the observed dipolar shift, δdip(obs), obtained via Eq. (1) for protons on residues with δdip(obs) > |0.25| ppm for NmHO-PH-OH, and compare these data with the previously reported data for the high-spin 50 NmHO-PH-H2O with negative Δχax, and low-spin 34 NmHO-PH-CN with positive Δχax. It is apparent that in each case the sign of the dipolar shift in NmHO-PH-OH is the same as that in NmHO-PH-CN, and opposite in sign to that in NmHO-PH-H2O, dictating that Δχax is positive in NmHO-PH-OH.

We first address the relative importance of the Δχax and Δχrh term in describing the observed dipolar shift for NmHO-PH-CN. The strong dominance of the axial anisotropy over the observed dipolar shifts in NmHO-PH-CN is evidenced by the fact that the change in Δχax and its orientation are only weakly affected by setting Δχrh = 0. Thus, a five-parameter search (Δχax, Δχrh, α, β and κ = α + γ) (not shown; see Supporting Information) for NmHO-PH-CN yields Δχax = 2.48 × 10-8 m3/mol, Δχrh = -0.52 × 10-8 m3/mol, α = 280 ±10°, β = 8±1°, κ = 40 ± 10°. When Δχrh is set equal to zero for NmHO-PH-CN (making γ or κ irrelevant), the resulting three-parameter search (Δχax, α and β) yields: Δχax = 2.40 × 10-8 m3/mol, α = 260±10° and β = 4 ±1°; (data not shown; see Supporting Information). This relative insensitivity of the axial anisotropy and its orientation to Δχrh in NmHO-PH-CN is due to the fact that the heme occupies most of the space that is strongly influenced by the rhombic term in Eq. (1), such that the δdip for non-ligated residues are reasonably well modeled by a solely Δχax value insignificantly different from the true Δχax. It is reasonable that Δχax will similarly dominate the dipolar shifts in NmHO-PH-OH.

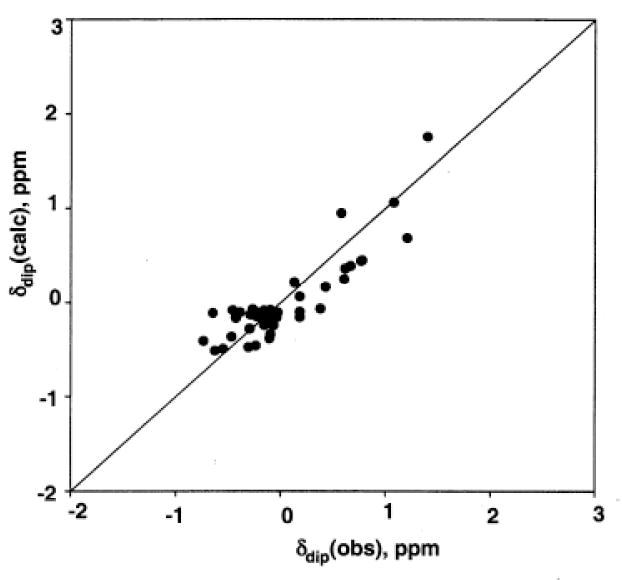

Using the δdip(obs) for assigned protons for NmHO-PH-OH listed in Table 2 as input for a least-square determination, of initially Δχax (Δχrh = 0, α = β = 0) normal to the heme, yielded a good fit with Δχax = 1.04 ± 0.10 × 10-8 m3/mol (not shown). Relaxing the restriction of the major magnetic axis normal to the heme, the three-parameter fit (Δχax, α, β) yielded essentially the same Δχax = 1.05 ± 0.10 × 10-8 m3/mol, with a very small tilt β = 4±1° in a direction with α = 260 ±15°, an inconsequentially reduced residual error function, and a reasonable correlation between δdip(obs) and δdip(calc), as shown in Figure 9. Moreover, the optimized magnetic axes do not predict any hyperfine shifted signal which should partially resolved either on the diamagnetic envelope edges or in the small window between the aromatic and aliphatic protons. Hence we conclude that the magnetic anisotropy of NmHO-PH-OH is predominantly axial, clearly positive in sign, and ~40% of the magnitude of that in NmHO-PH-CN.34 These results are consistent only with the primary population of the dπ (or dxy 2(dxz,dyz)3)ground state.

Figure 9.

Plot of δdip(obs) versus δdip(calc) for the optimized anisotropy and orientation of axially symmetric paramagnetic susceptibility tensor χ of NmHO-PH-OH at 25°C, with α = 260 ±15°, β = 4 ± 1° and Δχax = 1.04 ±0.14 × 10-8 m3/mol. The residual error function, F/n = 0.20 ppm2.

Influence on H-bond strength

Low-field bias of labile proton diamagnetic chemical shifts has been shown to correlate with H-bond length, and hence H-bond strength. 59, 60 However, in order to compare the different derivatives of NmHO, the observed chemical shift, δDSS(obs), must be corrected for the contribution from the paramagnetism, δdip(calc), obtained via the magnetic axes derived above. Hence δDSS(dia*) is obtained via:

| (4) |

where δDSS(dia*) reflects the H-bond effects. The δDSS(obs) and δDSS(dia*) values obtained for assigned labile protons in NmHO-PH-OH are listed in Table 1, where they can be compared to previously reported 50 δDSS(dia*) values for the NmHO-PH-H2O complex.

DISCUSSION

Resonance assignments

The dominance of exchange cross peaks at all pHs at which there is more than ~10% NmHO-PH-OH dramatically limits the de-novo assignment of residues within the NmHO-PH-OH complex at any pH where the sample is reasonably stable to degradation over 24 h. However, because the exchange cross peaks appear only upon increasing the pH above pH 7.0, it is possible to transfer to NmHO-PH-OH, by exchange, the assignment of peaks previously50 assigned which are resolved or exhibit large dipolar shifts in the NmHO-PH-H2O complexes.50 This naturally restricts residue assignments in NmHO-PH-OH to those residues which in NmHO-PH-H2O exhibited significant dipolar shifts or exhibited stronger than usual H-bonds. Fortunately, these are precisely the target residues for describing the magnetic properties and H-bond interactions in NmHO-PH-OH. While assignment of residues in the homologous PaHO complex have not been reported, the heme signals exhibit 40 similarly slow exchange between the H2O and OH- complexes, such that a similar assignment strategy would be applicable.

Thermodynamics/dynamics of the H2O ⇔ OH- transition

The integration of heme methyl peaks in the H2O and OH- complexes leads to the Henderson-Hasselbach plot in Figure 4. Integration of a high-spin and low-spin resolved methyl peak indicate that 1:1 population occurs at pH 9.8 in 2H2O (uncorrected for isotope effect), and about 0.4 units lower in 1H2O, ~9.4 (based on integration of the pH 10.2 spectra in 1H2O). The apparent pK for NmHO is some 1.5-1.8 units higher than values reported for the homologous PaHO complex (~8.0-8.3).13, 40 The obvious conclusion is that the H2O complex is stabilized, and/or the OH- complex is destabilized,41 in NmHO relative to PaHO substrate complexes. Comparison of the axial field strengths via Δχax and D, 61 the zero-field splitting parameter, 50 in the two HO-PH-H2O complexes would shed some light on potential differences in ligated water H-bonding with the protein matrix for the high-spin complexes of PaHO and NmHO. Such data are available for the NmHO complex, 50 but not yet for the PaHO complex. The estimated rate of exchange <103 s-1 for the NmHO-PH complex is somewhat slower than estimated for the PaHO-PH complex.40 Similarly slow exchange has been reported for the PaHO-PH-H2O/OH pair,40 but such slow exchange is not typical for all such HO complexes, as hHO exhibits slow exchange (Zhu, W; Ogura, H; Wong, J.-L.; Ortiz de Montellano, P. R.; La Mar, G.N.; unpublished data).

Magnetic properties and orbital ground state for NmHO-PH-OH

The comparison of the sign of δdip(obs) for assigned signals of NmHO-PH-OH, with the reported sign of δdip(obs) for S = 1/2, dπ NmHO-PH-CN 34 (Δχax > 0), and S = 5/2 NmHO-PH-H2O 50 (Δχax < 0), in Table 2 establishes that the axial anisotropy of NmHO-PH-OH is clearly positive. Quantitation of Δχax leads to Δχax = 1.04±0.10 × 10-8 m3/mol. The retained sign but reduced magnitude of the axial anisotropy in NmHO-PH-CN relative to NmHO-PH-OH is consistent with the pattern of the g-values in the EPR spectra of the same metglobin complexes. 45 The sign and magnitude of Δχax in NmHO-PH-OH therefore support only a predominantly ‘dπ’ orbital ground state38, 45

The resolved NmHO-PH-OH heme 3CH3 and 8CH3 peaks exhibit deviations from the general Curie behavior of the low-field methyl peak in the ‘dπ’ orbital ground state of low-spin cyanoferrihemoprotein 49, 62, 63 complexes. However, hydroxide is a significantly weaker axial field strength ligand than cyanide, and the majority of metglobin hydroxide complexes with the dominant ‘dπ’, S = 1/2 ground state, exhibit similar deviations from Curie behavior 49 because of the weak thermal population of the high-spin ferric state with its much larger methyl contact shifts.

The present results for NmHO-PH-OH with a dπ ground state are in contrast to the ‘dxy’ orbital ground state proposed6, 40 for the homologous PaHO-PH-OH complex on the basis of the 13C contact shift pattern of the PH substrate. The significant difference in the pKs for the acid-alkaline transition in PaHO and NmHO complexes would allow for significant differences in the effective axial field strength of the OH- ligand, such that different orbital ground states could, in principle, be populated for the two complexes. The relative values for the pKs for the two complexes are consistent with, but not proof for, stronger H-bond stabilization of the ligated OH- by proton donation by a non-ligated water in PaHO than NmHO (see Figure 1C). At this time, the 13C analysis of PH contact shifts40 has not been performed on NmHO-PH-OH, and the sign and magnitude of the axial anisotropy have not been reported for PaHO-PH-OH. Similar studies on both HOs may resolve this apparent paradox. The present data, however, indicate emphatically that, the ‘dxy’ orbital ground state of the HO-PH-OH complex is clearly not a signature of the general distal HO environment.

Dynamic stability of NmHO-PH-OH

It is remarkable that essentially all of the labile proton signals characterized50 at pH 7.0 in NmHO-PH-H2O are still detectable at pH 10.2, since they usually exhibit base-catalyzed exchange.64 Even more remarkable is the observation that saturation factors in 3:9:19 difference-spectra 52 between on-resonance and off-resonance saturation of the water signal at pH 10.2 (not shown; see Supporting Information) leads to small, and essentially the same (or smaller), saturation factors at pH 10.2 as observed at pH 7.0, where their exchange rate with bulk solvent was shown to be extremely slow.34 Thus the high dynamic stability, as reflected in very slow exchange rates of NHs, observed near neutral pH, appears to be retained even in strongly alkaline medium.

Effect of H2O to OH- conversion on the distal H-bond network

Correlations of δDSS(obs) for δdip(calc) for assigned NmHO-PH-OH labile protons are listed in Table 1. Also included are δdip(calc) values for NmHO-PH-OH which allow determination of δDSS(dia*), and the differences in δdip(calc) between the two complex: Δδdip(calc) = δdip(calc:NmHO-PH-H2O) - δdip(calc:NmHO-PH-OH), where δdip(calc:NmHO-PH-H2O) values have been published previously.50, and δdip(calc) for NmHO-PH-OH are estimated by the magnetic axes described above. It must be noted, since both the NmHO-PH-H2O and NmHO-PH-OH magnetic axes determination are based on only Δχax ≠ 0) (i.e., Δχrh = 0), and the magnetic axes for NmHO-PH-OH on the basis of significantly fewer experimental δdip(obs) than from NmHO-PH-H2O, 50 the uncertainties of Δδdip(calc) increase with increasing δdip(calc) for either complex. Hence, we conclude that differences in δDSS(dia*) between the H2O and OH- complex are significant only if this difference is comparable to the magnitude of Δδdip(calc).

Inspection of Table 1 shows that, while δDSS(obs) differs by as much as 1.6 ppm between the two complexes, correction for δdip(calc) for each complex reduces the difference in δDSS(dia*) to well under 0.2 ppm for all but a few labile protons. Hence the strength of the majority of the H-bonds is strongly conserved upon deprotonating the axial water. Among those NHs with significant (>0.2 ppm) differences in δDSS(dia*) in Table 1, Gln49 NεHs, and Cys113 NH, each exhibit large |Δδdip(calc)| ~1.0 to 1.3, rendering the interpretation of ΔδDSS(dia*) questionable. On the other hand, His53 Nε1H and Trp153 NεH exhibit lower field bias in the OH- than H2O complex, by amounts that are close to the Δδdip(calc), and hence can be considered significant. The data in Table 1 lead to the conclusion that the diamagnetic chemical shift, and hence H-bond donor strengths for His53 Nε1H and Trp153 NεH, is significantly modulated by the H2O ⇔ OH- conversion, with both H-bond donor strengths slightly greater in the OH- than H2O complex.

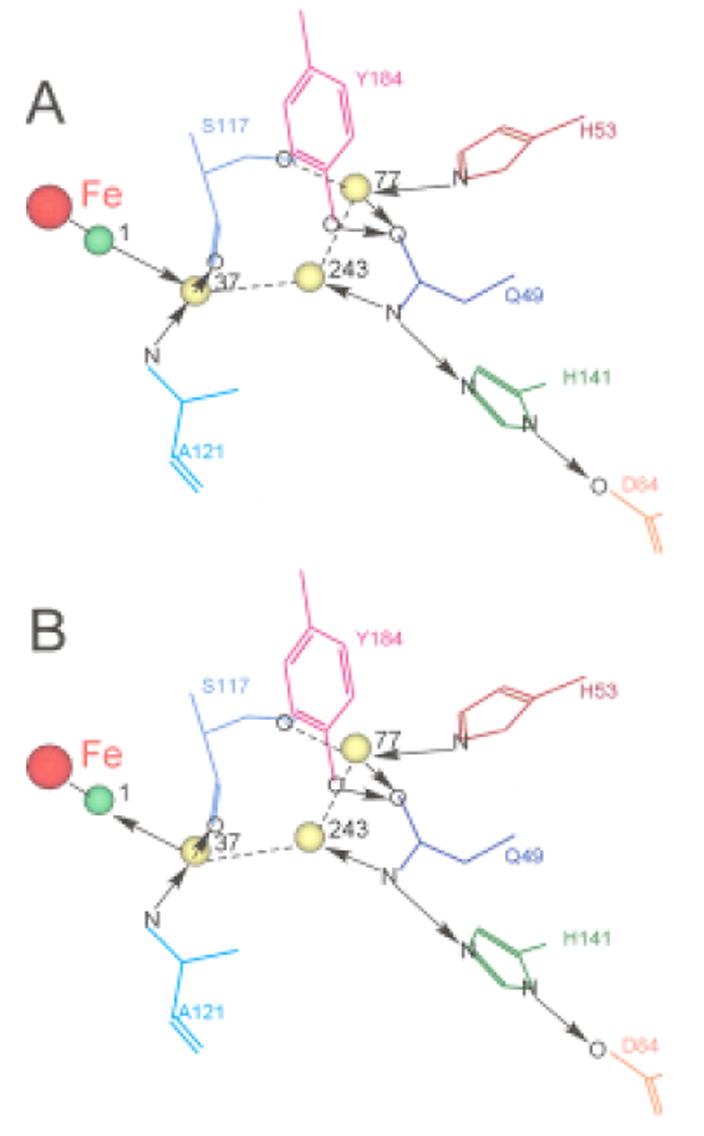

Figure 10 presents a schematic of the active site of NmHO-PH-H2O 14 that depicts the ligated H2O (Figure 10A) or OH- (Figure 10B) (both green spheres) and the three non-coordinated, catalytically implicated ordered water molecules (yellow spheres), as well as the residues (specifically His53) that interact directly, or indirectly, with these water molecules. The side chains of both Gln49 and His53 are rotated 180° about the β-γ bonds from that in the crystal structures 14, 15, as confirmed by solution NOESY cross peaks in both NmHO-PH-CN 34 and NmHO-PH-H2O.50 Arrows depict H-bond direction for cases where the position of the donor and acceptor atoms are clear. Dashed lines represent the other H-bonds for which it is not possible, based on either crystallography or 1H NMR, to uniquely ascertain the direction of the proton donation. Conversion of the necessarily H-bond donor (Figures 1B and 10A) ligated water#1 to a necessarily H-bond acceptor hydroxide molecule (Figures 1C and 10B) logically leads to a stronger H-bond donation by His53 Nε1H for the ligated OH- as observed.

Figure 10.

(A) Schematic structure of the distal cavity of NmHO-PH-H2O showing the relative position of the ligated water, H2O#1 (green sphere), the three conserved catalytically relevant, non-ligated water molecules, H2O#243, H2O#37 and H2O#77 (yellow spheres) and several key residues involved in the H-bond stabilization of these water molecules based on the NmHO-PH-H2O crystal structure and the previously documented 180° rotation about the β–γ bond for the Gln49 and His53 side chain.34, 50 The direction of H-bonds (donor → acceptor) are shown in solid arrows between the two heteroatoms. For cases where neither the crystal structure nor solution 1H NMR uniquely locates the position of the proton, and hence the direction of the H-bond cannot be definitively determined, the presence of the H-bond is shown as a dashed line. (B) Structure of NmHO-PH-H2O retained for the NmHO-PH-OH complex, except that the H-bond direction between water #1 and water #37 is reversed from that in A. The changed direction of the axial ligand (green sphere) in converting H2O (A) to OH (B) is consistent with the His53 Nε1H serving as a strong donor upon deprotonating the water.

Trp153 NεH in NmHO-PH-H2O serves as a H-bond donor primarily to an ordered water molecule #44, which, in turn, H-bonds to another ordered water molecule #32 that is a donor to the carboxylate of the 6-propionate. 14 Increasing the negative change on the heme by deprotonating the axial water could lead to the propionate anion carboxylate serving as a stronger H-bond acceptor to the ordered water #32, with the effect further transmitted to the Trp153 NεH. The δDSS(dia*) values for Gln49 NδHs chemical shifts, and hence H-bond strength of the side chain, appear also to respond to H2O → OH- conversion, but the chemical shift difference is much less than the Δδdip(calc). The further quantitation of Δχrh for NmHO-PH-OH would assist in more accurately defining the change in H-bond strength. While additional assignments in NmHO-PH-OH by 1H NMR may be problematical due to the high pK and the inability to predominantly populate the NmHO-PH-OH complex, the use of electron withdrawing substitutions is known42-44 to markedly lower the acid-alkaline pK, and hence could allow a complete conversion to the hydroxide complex below pH 10 without danger of degradation at the extreme pH. Similar 1H NMR studies of the hydroxide complex of a formyl-substituted substrate are planned.

The data show that the state of the axial water is transmitted to the His53 side chain Nε1H some 10Å from the iron. Since the primary interaction of the iron ligand is with one (#37) of the ordered water molecules, which is linked to His53 by an additional two ordered water molecules (#243 and #77), it is reasonable that this “link” between the ligand and His53 is transmitted via the water-chain. The small effect on His53 Nε1H, and the absence of clear perturbations of other H-bonds in the distal network (i.e., His141, Gln49) by the H2O to OH- conversion may be considered surprising, in view of the dramatic acid/base properties of the alternate heme iron ligands. However, each of these residues, as well as the catalytic water molecules shown in Figure 10, are members of a much more extended network of H-bonds, and ordered water molecules, 15, 34 such that this highly coupled network may compensate for a single strong perturbation within the network. The further characterization of the H-bond/ordered water network must await planned 15N-labeling of NmHO.

CONCLUSIONS

The assignment of active site residues in ferric, low-spin, NmHO-PH-OH reveals a pattern of dipolar shifts for active site residues that is consistent with only positive axial anisotropy for the paramagnetic susceptibility tensor. Quantitation of the tensor yields an axial anisotropy with ~40% of the magnitude found in the well-characterized ferric, low-spin NmHO-PH-CN complex.34 Hence the dominant orbital ground state for NmHO-PH-OH is the common dπ, and not the unusual ‘dxy’ orbital state suggested to be a signature of the HO active site. The conversion of the H-bond donor ligated water to the H-bond acceptor ligated hydroxide leads to a detectable strengthening of the His53 side chain H-bond, which is linked to the ligated water/hydroxide through three ordered water molecules.

Supplementary Material

Four figures (partially relaxed spectra for NmHO-PH-OH, Curie plot for heme methyls and comparison of magnetic axes determination for NmHO-PH-CN with and without considerations of rhombic anisotropies, and labile proton saturation factors) and one Table (chemical shifts for assigned NmHO-PH-OH residues), total 5 pages.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health, GM62830 (GNL) and a grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (16570102) from the Ministry of Education and Sports, Science and Teaching, Japan (T.Y.)

Footnotes

ABBREVIATIONS: HO, heme oxygenase; NmHO, Neisseria meningitidis heme oxygenase; NOESY, two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser spectroscopy; TOCSY, two-dimensional total correlation spectroscopy; Dss, 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate; PH, protohemin;

References

- 1.Tenhunen R, Marver HS, Schmid R. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:6388–6394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida T, Migita CT. J Inorg Biochem. 2000;82:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(00)00156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilks A. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4:603–614. doi: 10.1089/15230860260220102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ortiz de Montellano PR, Auclair K. In: The Porphryin Handbook. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 12. Elsevier Science; San Diego, CA: 2003. pp. 175–202. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frankenberg-Dinkel N. Antoxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:825–834. doi: 10.1089/ars.2004.6.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivera M, Zeng Y. J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99:337–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uzel C, Conrad ME. Seminars in Hematology. 1998;35:27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maines MD. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:517–554. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma A, Hirsch DJ, Glatt CE, Ronnett GV, Snyder SH. Science. 1993;259:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.7678352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beale SI. Ciba Found Symp. 1994;180:156–168. doi: 10.1002/9780470514535.ch9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilks A, Schmitt MP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:837–841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu W, Willks A, Stojiljkovic I. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6783–6790. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6783-6790.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ratliff M, Zhu M, Deshmukh R, Wilks A, Stojiljkovic I. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6394–6403. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6394-6403.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuller DJ, Zhu W, Stojiljkovic I, Wilks A, Poulos TL. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11552–11558. doi: 10.1021/bi0110239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman JM, Lad L, Deshmukh R, Li HY, Wilks A, Poulos TL. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34654–34659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302985200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caignan GA, Deshmukh R, Wilks A, Zeng Y, Huang H-W, Moenne-Loccoz P, Bunce RA, Eastman MA, Rivera M. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14879–14892. doi: 10.1021/ja0274960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedman J, Lad L, Li H, Wilks A, Poulos TL. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5239–5245. doi: 10.1021/bi049687g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortiz de Montellano PR, Wilks A. Adv Inorg Chem. 2001;51:359–407. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida T, Noguchi M, Kikuchi G. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4418–4420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilks A, Torpey J, Ortiz de Montellano PR. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29553–29556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ortiz de Montellano PR. Acct Chem Res. 1998;31:543–549. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davydov RM, Yoshida T, Ikeda-Saito M, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:10656–10657. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davydov R, Kofman V, Fujii H, Yoshida T, Ikeda-Saito M, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:1798–1808. doi: 10.1021/ja0122391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davydov R, Chemerisov S, Werst DE, Rajh T, Matsui T, Ikeda-Saito M, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15960–15961. doi: 10.1021/ja044646t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamachi T, Shestakov AF, Yoshizawa K. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3672–3673. doi: 10.1021/ja030393c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unno M, Matsui T, Chu GC, Coutoure M, Yoshida T, Rousseau DL, Olson JS, Ikeda-Saito M. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21055–21061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lad L, Wang J, Li H, Friedman J, Bhaskar B, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Poulos TL. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:527–538. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sugishima M, Sakamoto H, Noguchi M, Fukuyama K. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9898–9905. doi: 10.1021/bi027268i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorst CM, Wilks A, Yeh DC, Ortiz de Montellano PR, La Mar GN. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:8875–8884. [Google Scholar]

- 30.La Mar GN, Asokan A, Espiritu B, Yeh DC, Auclair K, Ortiz de Montellano PR. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15676–15687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Syvitski RT, Auclair K, Wilks A, Ortiz de Montellano PR, La Mar GN. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33018–33031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204216200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y, Syvitski RT, Auclair K, Ortiz de Montellano PR, La Mar GN. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13392–13403. doi: 10.1021/ja036176t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Syvitski RT, Chu GC, Ikeda-Saito M, La Mar GN. J Biol Chem. 2003;279:6651–6663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211249200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Zhang X, Yoshida T, La Mar GN. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10112–10126. doi: 10.1021/bi049438s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schuller DJ, Wilks A, Ortiz de Montellano PR, Poulos TL. Nature Struct Biol. 1999;6:860–867. doi: 10.1038/12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugishima M, Sakamoto H, Higashimoto Y, Omata Y, Hayashi S, Noguchi M, Fukuyama K. J Biol Chem. 2002:45086–45090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hirotsu S, Chu GC, Unno M, Lee D-S, Yoshida T, Park S-Y, Shiro Y, Ikeda-Saito M. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11937–11947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker FA. In: The Porphyrin Handbook. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 5. Academic Press; Boston: 2000. pp. 1–183. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rivera M, Caignan GA, Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM, Shokhireva TK, Walker FA. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6077–6089. doi: 10.1021/ja017334o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Caignan GA, Deshmukh R, Zeng Y, Wilks A, Bunce RA, Rivera M. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11842–11852. doi: 10.1021/ja036147i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Caughey WS. In: Hemes and Hemoproteins. Chance B, Estabrook RW, Yonetani T, editors. Academic Press; New York: 1966. pp. 276–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunori M, Amiconi G, Antonini E, Wyman J, Zito R, Rossi-Fanolli A. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1968;154:315–322. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(68)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cowgill RW, Clark WM. J Biol Chem. 1952;198:33–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McGrath TM, La Mar GN. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;534:99–111. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(78)90480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palmer G. In: The Porphyrins. Dolphin D, editor. IV. Academic Press; New York: 1979. pp. 313–353. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walker FA, Simonis U. Biol Magn Reson. 1993:12. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Williams G, Clayden NJ, Moore GR, Williams RJP. J Mol Biol. 1985;183:447–460. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emerson SD, La Mar GN. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1556–1566. doi: 10.1021/bi00458a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.La Mar GN, Satterlee JD, de Ropp JS. In: The Porphyrins Handbook. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 5. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. pp. 185–298. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Y, Zhang X, Yoshida T, La Mar GN. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6409–6422. doi: 10.1021/ja042339h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnston PD, Figueroa N, Redfield AG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:3130–3134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piotto M, Sandek V, Sklenar V. J Biomol NMR. 1992;2:661–666. doi: 10.1007/BF02192855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeener J, Meier BH, Bachmann P, Ernst RR. J Chem Phys. 1979;71:4546–4553. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Griesinger C, Otting G, Wüthrich K, Ernst RR. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:7870–7872. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bax A, Davis DG. J Magn Reson. 1985;65:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neal S, Nip AM, Zhang H, Wishart DS. J Biomol NMR. 2003;26:215–240. doi: 10.1023/a:1023812930288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cross KJ, Wright PE. J Magn Reson. 1985;64:220–231. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sandström J. Dynamic NMR Spectroscopy. Academic Press; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wagner G, Pardi A, Wüthrich K. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:5948–5949. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harris TK, Mildvan AS. Prot: Struct Funct Genet. 1999;35:275–282. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990515)35:3<275::aid-prot1>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brackett GC, Richards DL, Caughey WS. J Chem Phys. 1971;54:4383–4401. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turner DL. (A).J Magn Reson. 1993;104:197–202. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shokhirev NV, Walker FA. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:17795–17804. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Englander SW, Kallenbach NR. Quart Rev Biophys. 1984;16:521–655. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500005217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Four figures (partially relaxed spectra for NmHO-PH-OH, Curie plot for heme methyls and comparison of magnetic axes determination for NmHO-PH-CN with and without considerations of rhombic anisotropies, and labile proton saturation factors) and one Table (chemical shifts for assigned NmHO-PH-OH residues), total 5 pages.