Abstract

Life is that which replicates and evolves. The origin of life is also the origin of evolution. A fundamental question is when do chemical kinetics become evolutionary dynamics? Here, we formulate a general mathematical theory for the origin of evolution. All known life on earth is based on biological polymers, which act as information carriers and catalysts. Therefore, any theory for the origin of life must address the emergence of such a system. We describe prelife as an alphabet of active monomers that form random polymers. Prelife is a generative system that can produce information. Prevolutionary dynamics have selection and mutation, but no replication. Life marches in with the ability of replication: Polymers act as templates for their own reproduction. Prelife is a scaffold that builds life. Yet, there is competition between life and prelife. There is a phase transition: If the effective replication rate exceeds a critical value, then life outcompetes prelife. Replication is not a prerequisite for selection, but instead, there can be selection for replication. Mutation leads to an error threshold between life and prelife.

Keywords: prelife, replication, selection, mutation, mathematical biology

The attempt to understand the origin of life has inspired much experimental and theoretical work over the years (1–10). Many of the basic building blocks of life can be produced by simple chemical reactions (11–15). RNA molecules can both store genetic information and act as enzymes (16–24). Fatty acids can self-assemble into vesicles that undergo spontaneous growth and division (25–28). The defining feature of biological systems is evolution. Biological organisms are products of evolutionary processes and capable of undergoing further evolution. Evolution needs a generative system that can produce unlimited information. Evolution needs populations of information carriers. Evolution needs mutation and selection. Normally, one thinks of these properties as being derivative of replication, but here, we formulate a generative chemistry (“prelife”) that is capable of selection and mutation before replication. We call the resulting process “prevolutionary dynamics.” Replication marks the transition from prevolutionary to evolutionary dynamics, from prelife to life.

Let us consider a prebiotic chemistry that produces activated monomers denoted by 0* and 1*. These chemicals can either become deactivated into 0 and 1 or attach to the end of binary strings. We assume, for simplicity, that all sequences grow in one direction. Thus, the following chemical reactions are possible:

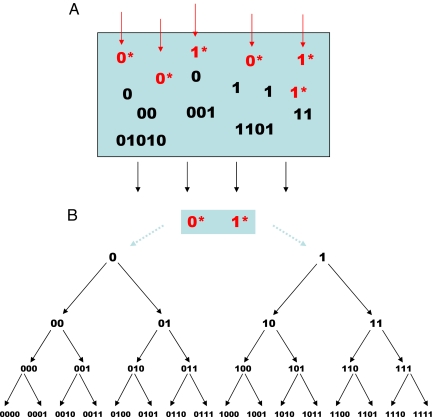

Here i stands for any binary string (including the null element). These copolymerization reactions (29, 30) define a tree with infinitely many lineages. Each sequence is produced by a particular lineage that contains all of its precursors. In this way, we can define a prebiotic chemistry that can produce any binary string and thereby generate, in principle, unlimited information and diversity. We call such a system prelife and the associated dynamics prevolution (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A binary soup and the tree of prelife. (A) Prebiotic chemistry produces activated monomers, 0* and 1*, which form random polymers. Activated monomers can become deactivated, 0* → 0 and 1* → 1 or attach to the end of strings, for example, 00 + 1* → 001. We assume that all strings grow only in one direction. Therefore, each string has one immediate precursor and two immediate followers. (B) In the tree of prelife, each sequence has exactly one production lineage. The arrows indicate all of the chemical reactions of prelife up to length n = 4.

Each sequence, i, has one precursor, i′, and two followers, i0 and i1. The parameter ai denotes the rate constant of the chemical reaction from i′ to i. At first, we assume that the active monomers are always at a steady state. Their concentrations are included in the rate constants, ai. All sequences decay at rate, d. The following system of infinitely many differential equations describes the deterministic dynamics of prelife:

The index, i, enumerates all binary strings of finite length, 0,1,00,…. The abundance of string i is given by xi and its time derivative by ẋi. For the precursors of 0 and 1, we set x0′ = x1′ = 1. If all rate constants are positive, then the system converges to a unique steady state, where (typically) longer strings are exponentially less common than shorter ones. Introducing the parameter bi = ai/(d + ai0 + ai1), we can write the equilibrium abundance of sequence i as xi = bi bi′ bi″… bσ. The product is over the entire lineage leading from the monomer, σ (= 0 or 1), to sequence i. The total population size converges to X = (a0 + a1)/d. The rate constants, ai, of the copolymerization process define the “prelife landscape.” We will now discuss three different prelife landscapes.

For “supersymmetric” prelife, we assume that a0 = a1 = α/2, and ai = a for all other i. Hence, all sequences grow at uniform rates. In this case, all sequences of length n have the same equilibrium abundance given by xn = [α/2a][a/(2a + d)]n. Thus, longer sequences are exponentially less common. The total equilibrium abundance of all strings is X = α/d. The average sequence length is n̄ = 1 + 2a/d.

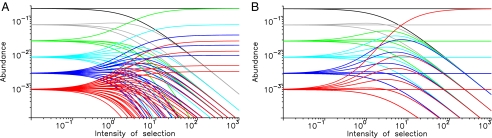

Selection emerges in prelife, if different reactions occur at different rates. Consider a random prelife landscape, where a fraction p of reactions are fast (ai = 1 + s), whereas the remaining reactions are slow (ai = 1). Fig. 2A shows the equilibrium distribution of all sequences as a function of the selection intensity, s. For larger values of s, some sequences are selected (highly prevalent), whereas the others decline to very low abundance. The fraction of sequences that are selected out of all sequences of length n is given by (1 − p)2[1 − p(1 − p)]n−1. See supporting information (SI) for all detailed calculations.

Fig. 2.

Selection can occur in prelife without replication. The equilibrium abundances of all sequences of length 1 to 6 are shown as a function of the intensity of selection, s. There are 2n sequences of length n. (A) In a random prelife landscape, half of all reactions occur at rate 1 + s, the other half at rate 1. As s increases, a small subset of sequences is selected, whereas the others decline to very low abundance. (B) All reactions leading to the one “master sequence” of length 6 occur at rate b = 1 + s, all others at rate a = 1. As s increases, the master sequence is selected. Lineages that share sequences with the master sequence are suppressed, whereas other lineages are unaffected. Color code: black, gray, green, light blue, blue, and red for sequences of length 1 to 6, respectively. Other parameters: a0 = a1 = 1/2 and d = 1.

Another example of an asymmetric prelife landscape contains a “master sequence” of length n (Fig. 2B). All reactions that lead to that sequence have an increased rate b, while all other rates are a. The master sequence is more abundant than all other sequences of the same length. But the master sequence attains a significant fraction of the population (= is selected) only if b is much larger than a. The required value of b grows as a linear function of n. In this prelife landscape, we can also discuss the effect of “mutation.” The fast reactions leading to the master sequence might incorporate the wrong monomer with a certain probability, u, which then acts as a mutation rate in prelife. We find an error threshold: The master sequence can attain a significant fraction of the population, only if u is less than the inverse of the sequence length, 1/n.

Let us now assume that some sequences can act as a templates for replication. These replicators are not only formed from their precursor sequences in prelife but also from active monomers at a rate that is proportional to their own abundance. We obtain the following differential equation

As before, the index i enumerates all binary strings of finite length. The first part of the equation describes prelife (exactly as in Eq. 2). The second part represents the standard selection equation of evolutionary dynamics (28). The fitness of sequence i is given by fi. All sequences have a frequency-dependent death rate, which represents the average fitness, φ = Σifixi/Σixi and ensures that the total population size remains at a constant value.

The parameter r scales the relative rates of template-directed replication and template-independent sequence growth. These two processes are likely to have different kinetics. For example, their rates could depend differently on the availability of activated monomers. In this case, r could be an increasing function of the abundance of activated monomers. Template-directed replication requires double-strand separation. A common idea is that double-strand separation is caused by temperature oscillations, which means that r is affected by the frequency of those oscillations. The magnitude of r determines the relative importance of life versus prelife. For small r, the dynamics are dominated by prevolution. For large r, the dynamics are dominated by evolution.

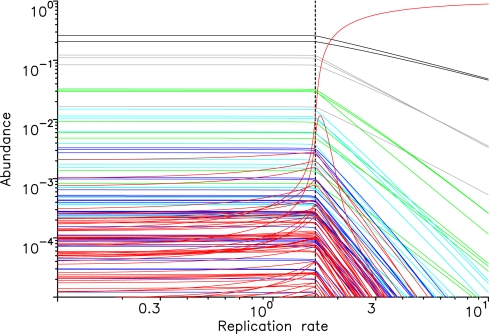

Fig. 3 shows the competition between life (replication) and prelife. We assume a random prelife landscape where the ai values are taken from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1. All sequences of length n = 6 have the ability to replicate. Their relative fitness values, fi, are also taken from a uniform distribution on [0,1]. For small values of r, the equilibrium structure of prelife is unaffected by the presence of potential replicators; longer sequences are exponentially less frequent than shorter ones. There is a critical value of r, where a number of replicators increase in abundance. For large r, the fastest replicator dominates the population, whereas all other sequences converge to very low abundance. In this limit, we obtain the standard selection equation of evolutionary dynamics with competitive exclusion.

Fig. 3.

The competition between life and prelife results in selection for (or against) replication. The equilibrium abundances of all sequences of length 1 to 6 are shown versus the relative replication rate, r. We assume a random prelife landscape, where the reaction rates ai are taken from a uniform distribution on [0,1]. All sequences of length n = 6 can replicate. Their fitness values are also taken from a uniform distribution on [0,1]. For small values of r, prelife prevails. For large values of r, the fastest replicator dominates the population. As r increases, there is a phase transition at the critical value rc. The fitness of the fastest replicator is given by fi = 0.999, its extension rates are ai0 = 0.4418 ai1 = 0.1284. The death rate is d = 1. We have rc = (d + ai0 + ai1)/fi = 1.572, which is indicated by the broken vertical line and is in perfect agreement with the numerical simulation. The color code is the same as in Fig. 2.

Between prelife and life, there is a phase transition. The critical replication rate, rc, is given by the condition that the net reproductive rate of the replicators becomes positive. The net reproductive rate of replicator i can be defined as gi = r(fi − φ) − (d + ai0 + ai1). For r < rc, the abundance of replicators is low, and therefore, φ is negligibly small. In Fig. 3, we have d = 1 and ai0 + ai1 = 1 on average. For the fastest replicator, we expect fi ≈ 1. Thus, the phase transition should occur around rc ≈ 2, which is the case. Using the actual rate constants of the fastest replicator in our system, we obtain the value rc = 1.572, which is in perfect agreement with the exact numerical simulation (see broken vertical line in Fig. 3).

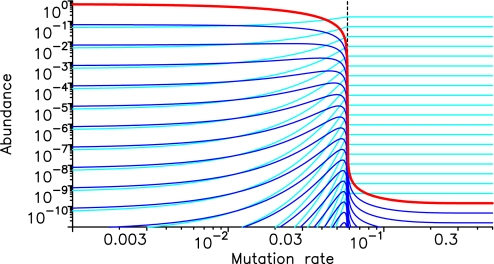

Replication can be subject to mistakes. With probability u, a wrong monomer is incorporated. In Fig. 4, we consider a “single-peak” fitness landscape: One seqence of length n can replicate. The probability of error-free replication is given by q = (1 − u)n. The net reproductive rate of the replicator is now given by gi = r(fiq − φ) − (d + ai0 + ai1). The replicator is selected if the replication accuracy, q, is greater than a certain value, given by q > (d + ai0 + ai1)/rfi. Thus, mutation leads to an error threshold for the emergence of life. Replication is selected only if the mutation rate, u, is less than a critical value that is proportional to the inverse of the sequence length, 1/n. This finding is reminiscent of classical quasispecies theory (3, 4), but there, the error threshold arises when different replicators compete (“within life”). Here, we observe an error threshold between life and prelife.

Fig. 4.

There is an error threshold between life and prelife. We assume a “single-peak” fitness landscape, where one sequence of length n = 20 can replicate, but no other sequence replicates. Replication is subject to mutation. The mutation rate, u, denotes the error probability per base. Error-free replication of the entire sequence occurs with probability q = (1 − u)n. We show all sequences that belong to the lineage of the replicator. The replicator is shown in red; shorter sequences are light blue, and longer ones dark blue. For small mutation rates, the replicator dominates the population, and the equilibrium structure is given by the mutation-selection balance of life. There is a critical error threshold. The theoretical prediction for this threshold, uc = 1 −[ (d + 2a)/r]1/n = 0.058, is illustrated by the vertical broken line and is in perfect agreement with the numerical simulation. For larger mutation rates, we obtain the normal prelife equilibrium: Longer sequences (including the replicator) are exponentially less common than shorter ones. Parameter values: a0 = 1/2, a = 1, d = 1; supersymmetric prelife; r = 10, f20 = 1.

Traditionally, one thinks of natural selection as choosing between different replicators. Natural selection arises if one type reproduces faster than another type, thereby changing the relative abundances of these two types in the population. Natural selection can lead to competitive exclusion or coexistence. In the present theory, however, we encounter natural selection before replication. Different information carriers compete for resources and thereby gain different abundances in the population. Natural selection occurs within prelife and between life and prelife. In our theory, natural selection is not a consequence of replication, but instead natural selection leads to replication. There is “selection for replication” if replicating sequences have a higher abundance than nonreplicating sequences of similar length. We observe that prelife selection is blunt: Typically small differences in growth rates result in small differences in abundance. Replication sharpens selection: Small differences in replication rates can lead to large differences in abundance.

We have proposed a mathematical theory for studying the origin of evolution. Our aim was to formulate the simplest possible population dynamics that can produce information and complexity. We began with a “binary soup” where activated monomers form random polymers (binary strings) of any length (Fig. 1). Selection emerges in prelife, if some sequences grow faster than others (Fig. 2). Replication marks the transition from prelife to life, from prevolution to evolution. Prelife allows a continuous origin of life. There is also competition between life and prelife. Life is selected over prelife only if the replication rate is greater than a certain threshold (Fig. 3). Mutation during replication leads to an error threshold between life and prelife. Life can emerge only if the mutation rate is less than a critical value that is proportional to the inverse of the sequence length (Fig. 4). All fundamental equations of evolutionary and ecological dynamics assume replication (31–33), but here, we have explored the dynamical properties of a system before replication and the emergence of replication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by the John Templeton Foundation, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (H.O.), the National Science Foundation/National Institutes of Health joint program in mathematical biology (NIH Grant R01GM078986), and J. Epstein.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0806714105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Crick FH. The origin of the genetic code. J Mol Biol. 1968;38:367–379. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller SL, Orgel LE. The Origins of Life on the Earth. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eigen M, Schuster P. The hyper cycle. A principle of natural self-organization. Part A: Emergence of the hyper cycle. Naturwissenschaften. 1977;64:541–565. doi: 10.1007/BF00450633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eigen M, McCaskill J, Schuster P. The molecular quasi-species. Adv Chem Phys. 1989;75:149–263. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein DL, Anderson PW. A model for the origin of biological catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1751–1753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.6.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kauffman SA. Autocatalytic sets of proteins. J Theor Biol. 1986;119:1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(86)80047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orgel LE. Molecular replication. Nature. 1992;358:203–209. doi: 10.1038/358203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontana W, Buss LW. The arrival of the fittest: Toward a theory of biological organization. B Math Biol. 1994;56:1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fontana W, Buss LW. What would be conserved if the tape were played twice? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:757–761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyson F. Origins of Life. Cambridge, UK/NY: Cambridge Univ Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller SL. A production of amino acids under possible primitive earth conditions. Science. 1953;117:528–529. doi: 10.1126/science.117.3046.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szostak JW, Bartel DP, Luisi PL. Synthesizing life. Nature. 2001;409:387–390. doi: 10.1038/35053176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benner SA, Caraco MD, Thomson JM, Gaucher EA. Planetary biology: Paleontological, geological, and molecular histories of life. Science. 2002;296:864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1069863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricardo A, Carrigan MA, Olcott AN, Benner SA. Borate minerals stabilize ribose. Science. 2004;303:196–196. doi: 10.1126/science.1092464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benner SA, Ricardo A. Planetary systems biology. Mol Cell. 2005;17:471–472. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joyce GF. Evolution in an RNA world. Origins Life Evol B. 2005;36:202–204. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellington AD, Szostak JW. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartel DP, Szostak JW. Isolation of new ribozymes from a large pool of random sequences. Science. 1993;261:1411–1418. doi: 10.1126/science.7690155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cech TR. The efficiency and versatility of catalytic RNA: Implications for an RNA world. Gene. 1993;135:33–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sievers D, von Kiedrowski G. Self-replication of complementary nucleotide-based oligomers. Nature. 1994;369:221–224. doi: 10.1038/369221a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferris JP, Hill AR, Liu R, Orgel LE. Synthesis of long prebiotic oligomers on mineral surfaces. Nature. 1996;381:59–61. doi: 10.1038/381059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joyce GF. RNA evolution and the origins of life. Nature. 1989;338:217–224. doi: 10.1038/338217a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston WK, Unrau PJ, Lawrence MS, Glasner ME, Bartel DP. RNA-catalyzed RNA polymerization: Accurate and general RNA-templated primer extension. Science. 2001;292:1319–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.1060786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joyce GF. The antiquity of RNA-based evolution. Nature. 2002;418:214–221. doi: 10.1038/418214a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hargreaves WR, Mulvihill S, Deamer DW. Synthesis of phospholipids and membranes in prebiotic conditions. Nature. 1977;266:78–80. doi: 10.1038/266078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanczyc MN, Fujikawa SM, Szostak JW. Experimental models of primitive cellular compartments: Encapsulation, growth, and division. Science. 2003;302:618–622. doi: 10.1126/science.1089904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen IA, Roberts RW, Szostak JW. The emergence of competition between model protocells. Science. 2004;305:1474–1476. doi: 10.1126/science.1100757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen IA, Szostak JW. A kinetic study of the growth of fatty acid vesicles. Biophys J. 2004;87:988–998. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.039875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flory PJ. Principles of Polymer Chemistry. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ Press; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szwarc M, van Beylen M. Ionic Polymerization and Living Polymers. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nowak MA. Evolutionary Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hofbauer J, Sigmund K. Evolutionary Games and Population Dynamics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.May RM. Stability and Complexity in Model Ecosystems. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.