Abstract

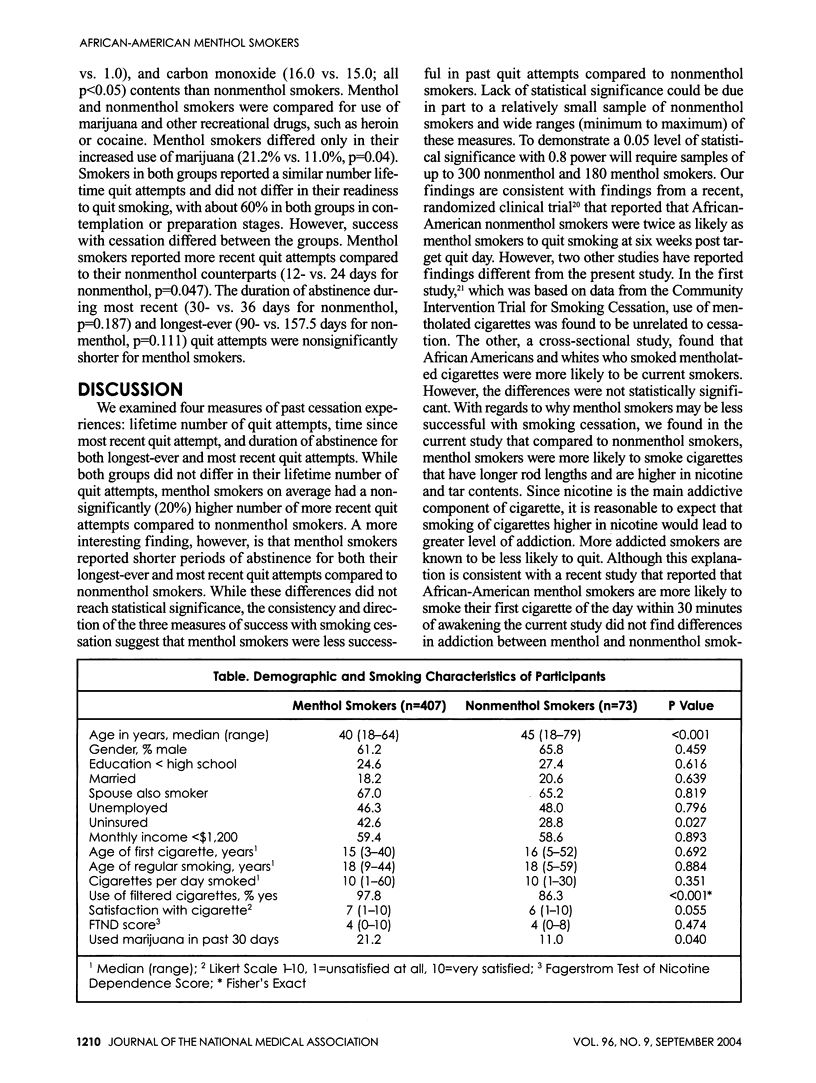

BACKGROUND: Despite smoking fewer cigarettes per day, African Americans have lower cessation rates and experience disproportionately higher rates of smoking-related health consequences. Because of their high preference for menthol cigarettes, it has been suggested that smoking menthol cigarettes may contribute to the excess smoking-related morbidity experienced by African Americans. Smoking menthol cigarettes could increase health risks from smoking if smokers of menthol cigarettes have lower cessation rates and thereby have longer duration of smoking compared to smokers of nonmentholated cigarettes. Few studies have examined associations between smoking of mentholated cigarettes and smoking cessation among African Americans. This study examined the smoking patterns of menthol cigarette smokers and their smoking cessation experiences. METHODS: A cross-sectional survey of 480 African-American smokers at an inner-city health center. Survey examined sociodemographics, smoking characteristics, and smoking cessation experiences of participants. Menthol smokers (n = 407) were compared to nonmenthol smokers (n = 73) in these characteristics. RESULTS: Menthol smokers were younger and more likely to smoke cigarettes with longer rod length, with filters, and those high in nicotine and tar. Although both groups did not differ by number of past quit attempts, time since most recent quit attempt was shorter for menthol smokers. The durations of most recent and longest-ever quit attempts were nonsignificantly shorter for menthol, compared to nonmenthol smokers. CONCLUSIONS: These data suggest that African-American menthol smokers are less successful with smoking cessation. Prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and examine mechanisms underlying such differences.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ahluwalia Jasjit S., Harris Kari Jo, Catley Delwyn, Okuyemi Kolawole S., Mayo Matthew S. Sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation in African Americans: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002 Jul 24;288(4):468–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo R. S., Giovino G. A., Pechacek T. F., Mowery P. D., Richter P. A., Strauss W. J., Sharp D. J., Eriksen M. P., Pirkle J. L., Maurer K. R. Racial and ethnic differences in serum cotinine levels of cigarette smokers: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1991. JAMA. 1998 Jul 8;280(2):135–139. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter C. L., Jarvik M. E., Morgenstern H., McCarthy W. J., London S. J. Mentholated cigarette smoking and lung-cancer risk. Ann Epidemiol. 1999 Feb;9(2):114–120. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caskey N. H., Jarvik M. E., McCarthy W. J., Rosenblatt M. R., Gross T. M., Carpenter C. L. Rapid smoking of menthol and nonmenthol cigarettes by black and white smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993 Oct;46(2):259–263. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90350-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström K. O. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3(3-4):235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M. C., Novotny T. E., Pierce J. P., Hatziandreu E. J., Patel K. M., Davis R. M. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. The changing influence of gender and race. JAMA. 1989 Jan 6;261(1):49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovino G. A., Schooley M. W., Zhu B. P., Chrismon J. H., Tomar S. L., Peddicord J. P., Merritt R. K., Husten C. G., Eriksen M. P. Surveillance for selected tobacco-use behaviors--United States, 1900-1994. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1994 Nov 18;43(3):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris R. E., Zang E. A., Anderson J. I., Wynder E. L. Race and sex differences in lung cancer risk associated with cigarette smoking. Int J Epidemiol. 1993 Aug;22(4):592–599. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland A., Garten S., Giovino G. A., Cummings K. M. Mentholated cigarettes and smoking cessation: findings from COMMIT. Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation. Tob Control. 2002 Jun;11(2):135–139. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabat G. C., Morabia A., Wynder E. L. Comparison of smoking habits of blacks and whites in a case-control study. Am J Public Health. 1991 Nov;81(11):1483–1486. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okah Felix A., Choi Won S., Okuyemi Kolawole S., Ahluwalia Jasjit S. Effect of children on home smoking restriction by inner-city smokers. Pediatrics. 2002 Feb;109(2):244–249. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi Kolawole S., Ahluwalia Jasjit S., Ebersole-Robinson Maiko, Catley Delwyn, Mayo Matthew S., Resnicow Ken. Does menthol attenuate the effect of bupropion among African American smokers? Addiction. 2003 Oct;98(10):1387–1393. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J. O., DiClemente C. C. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983 Jun;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeltz I., Schlotzhauer W. S. Benzo(a)pyrene, phenols and other products from pyrolysis of the cigarette additive, (d,1)-menthol. Nature. 1968 Jul 27;219(5152):370–371. doi: 10.1038/219370b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidney S., Tekawa I. S., Friedman G. D., Sadler M. C., Tashkin D. P. Mentholated cigarette use and lung cancer. Arch Intern Med. 1995 Apr 10;155(7):727–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]