Abstract

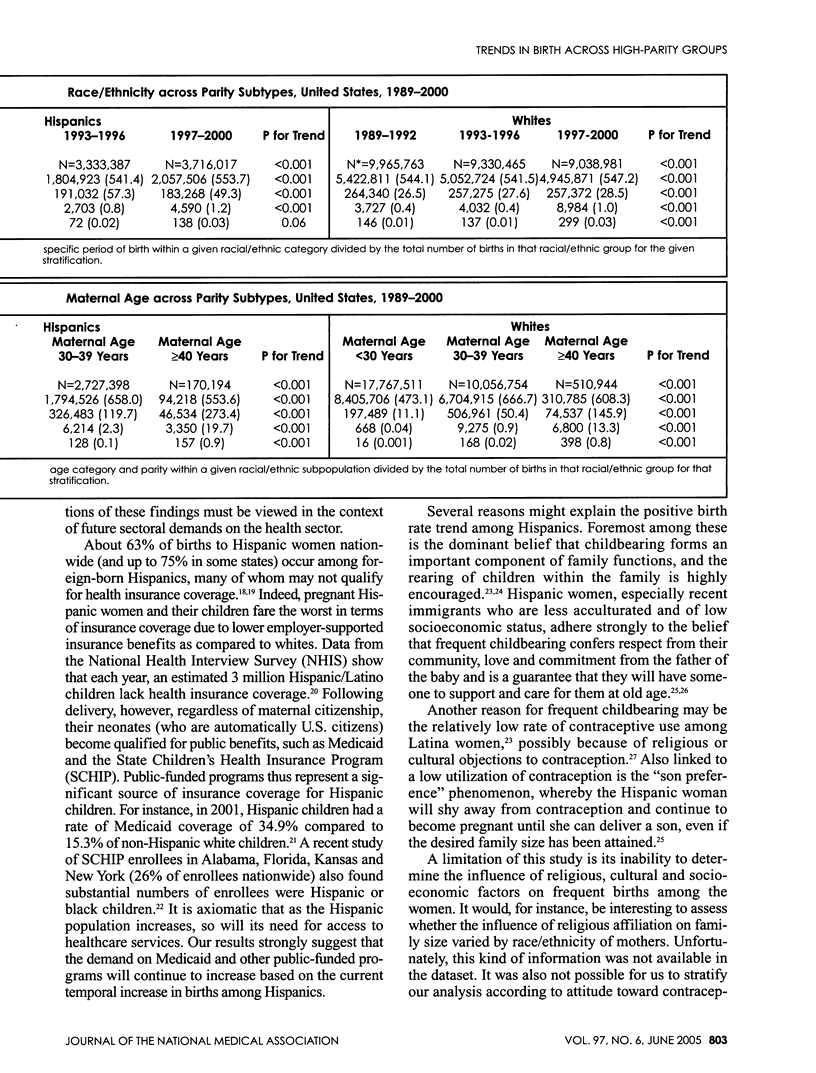

BACKGROUND: The changing racial and ethnic diversity of the U.S. population along with delayed childbearing suggest that shifts in the demographic composition of gravidas are likely. It is unclear whether trends in the proportion of births to parous women in the United States have changed over the decades by race and ethnicity, reflecting parallel changes in population demographics. METHODS: Singleton deliveries > or = 20 weeks of gestation in the United States from 1989 through 2000 were analyzed using data from the "Natality data files" assembled by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). We classified maternal age into three categories; younger mothers (aged < 30 years), mature mothers (30-39 years) and older mothers (> or = 40 years) and maternal race/ethnicity into three groups: blacks (non-Hispanic), Hispanics and whites (non-Hispanic). We computed birth rates by period of delivery across the entire population and repeated the analysis stratified by age and maternal race. Chi-squared statistics for linear trend were utilized to assess linear trend across three four-year phases: 1989-1992, 1993-1996 and 1997-2000. In estimating the association between race/ethnicity and parity status, the direct method of standardization was employed to adjust for maternal age. RESULTS: Over the study period, the total number of births to blacks and whites diminished consistently (p for trend < 0.001), whereas among Hispanics a progressive increase in the total number of deliveries was evident (p for trend < 0.001). Black and white women experienced a reduction in total deliveries equivalent to 10% and 9.3%, respectively, while Hispanic women showed a substantial increment in total births (25%). Regardless of race or ethnicity, birth rate was associated with increase in maternal age in a dose-effect fashion among the high (5-9 previous live births), very high (10-14 previous live births) and extremely high (> or = 15 previous live births) parity groups (p for trend < 0.001). After maternal age standardization, black and Hispanic women were more likely to have higher parity as compared to whites. CONCLUSIONS: Our findings demonstrate substantial variation in parity patterns among the main racial and ethnic populations in the United States. These results may help in formulating strategies that will serve as templates for optimizing resource allocation across the different racial/ethnic subpopulations in the United States.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brunner J., Melander E., Krook-Brandt M., Thomassen P. A. Grand multiparity as an obstetric risk factor; a prospective case-control study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992 Dec 28;47(3):201–205. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(92)90152-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A., Larkin P., Esler E. J., Condie R., Morrison J. The obstetric performance of the grand multipara. Med J Aust. 1977 Mar 5;1(10):330–332. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1977.tb76717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonston B., Passel J. S. Immigration and immigrant generations in population projections. Int J Forecast. 1992 Nov;8(3):459–476. doi: 10.1016/0169-2070(92)90058-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Afflick E., Hessol N. A., Pérez-Stable E. J. Maternal birthplace, ethnicity, and low birth weight in California. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998 Nov;152(11):1105–1112. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.11.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Afflick E., Hessol N. A., Pérez-Stable E. J. Maternal birthplace, ethnicity, and low birth weight in California. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998 Nov;152(11):1105–1112. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.11.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman G. A., Kaplan B., Neri A., Hecht-Resnick R., Harel L., Ovadia J. The grand multipara. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995 Aug;61(2):105–109. doi: 10.1016/0301-2115(95)02108-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Brady E., Martin Joyce A., Sutton Paul D., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Births: preliminary data for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2003 Jun 25;51(11):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip E. W., Collins R. J., Cheung A. N., Srivastava G. Prevalence of low and high risk human papillomavirus types in cervical cells from Hong Kong pregnant Chinese using filter in situ hybridization. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1991;249(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02390700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson Stefan Hrafn, Rendall Michael S. The fertility contribution of Mexican immigration to the United States. Demography. 2004 Feb;41(1):129–150. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Joyce A., Hamilton Brady E., Sutton Paul D., Ventura Stephanie J., Menacker Fay, Munson Martha L. Births: final data for 2002. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2003 Dec 17;52(10):1–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Joyce A., Hamilton Brady E., Ventura Stephanie J., Menacker Fay, Park Melissa M., Sutton Paul D. Births: final data for 2001. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002 Dec 18;51(2):1–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oron T., Sheiner E., Shoham-Vardi I., Mazor M., Katz M., Hallak M. Risk factors for antepartum fetal death. J Reprod Med. 2001 Sep;46(9):825–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman Horace, Robillard Pierre-Yves, Verspyck Eric, Hulsey Thomas C., Marpeau Loïc, Barau Georges. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes in grand multiparity. Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jun;103(6):1294–1299. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000127426.95464.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romo Laura F., Berenson Abbey B., Segars Amanda. Sociocultural and religious influences on the normative contraceptive practices of Latino women in the United States. Contraception. 2004 Mar;69(3):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salihu Hamisu M., Kinniburgh Brooke A., Aliyu Muktar H., Kirby Russell S., Alexander Greg R. Racial disparity in stillbirth among singleton, twin, and triplet gestations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Oct;104(4):734–740. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000139944.15133.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salihu Hamisu M., Shumpert M. Nicole, Slay Martha, Kirby Russell S., Alexander Greg R. Childbearing beyond maternal age 50 and fetal outcomes in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Nov;102(5 Pt 1):1006–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00739-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott Gulnur, Ni Hanyu. Access to health care among Hispanic/Latino children: United States, 1998-2001. Adv Data. 2004 Jun 24;(344):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger J. B., Molina G. B. Desired family size and son preference among Hispanic women of low socioeconomic status. Fam Plann Perspect. 1997 Nov-Dec;29(6):284–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]