Abstract

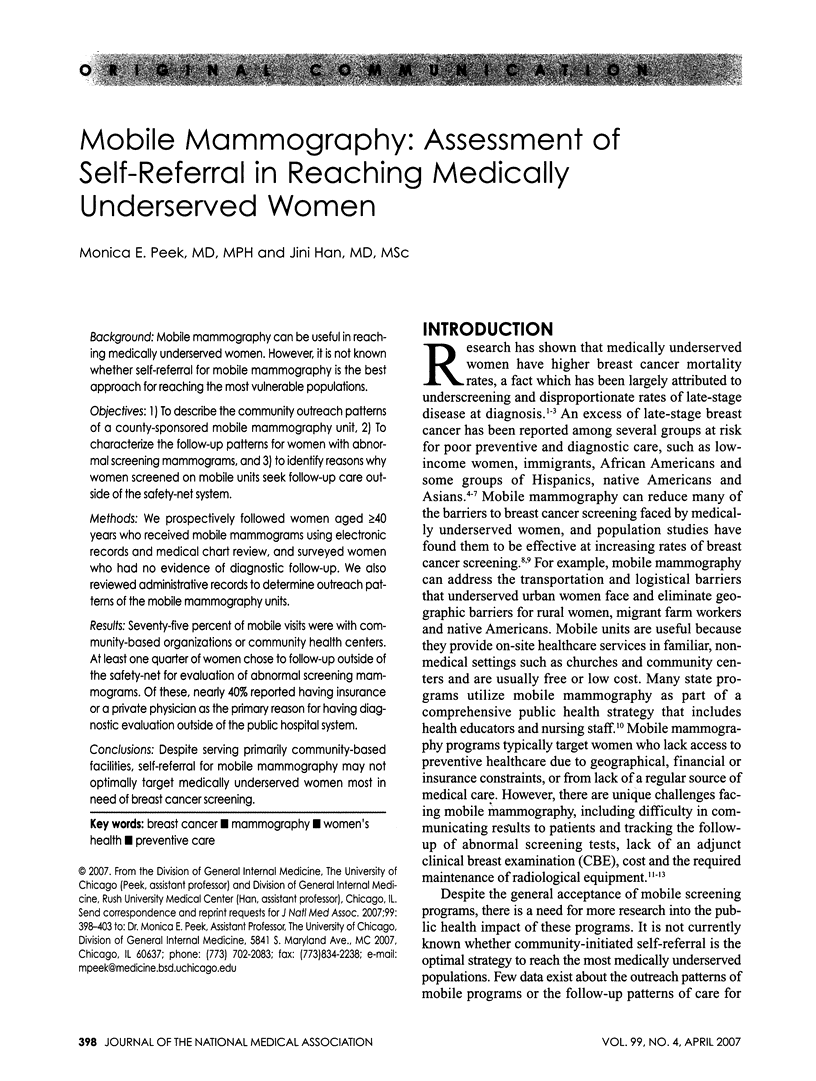

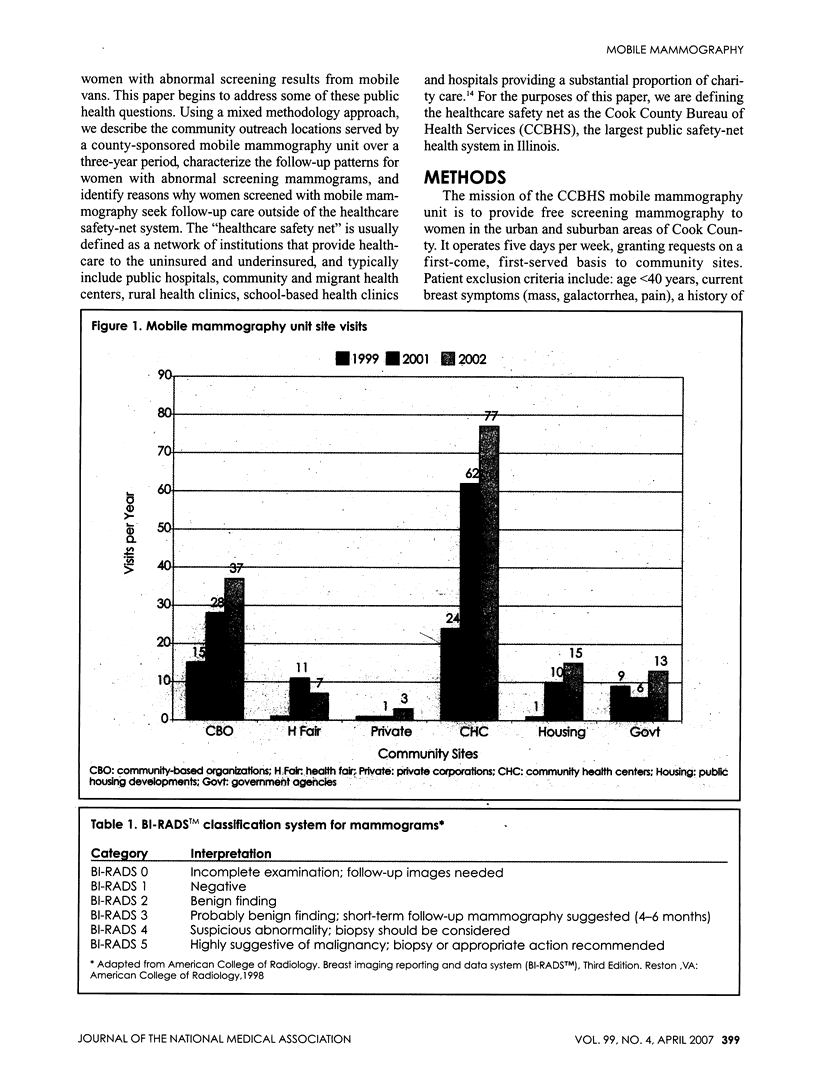

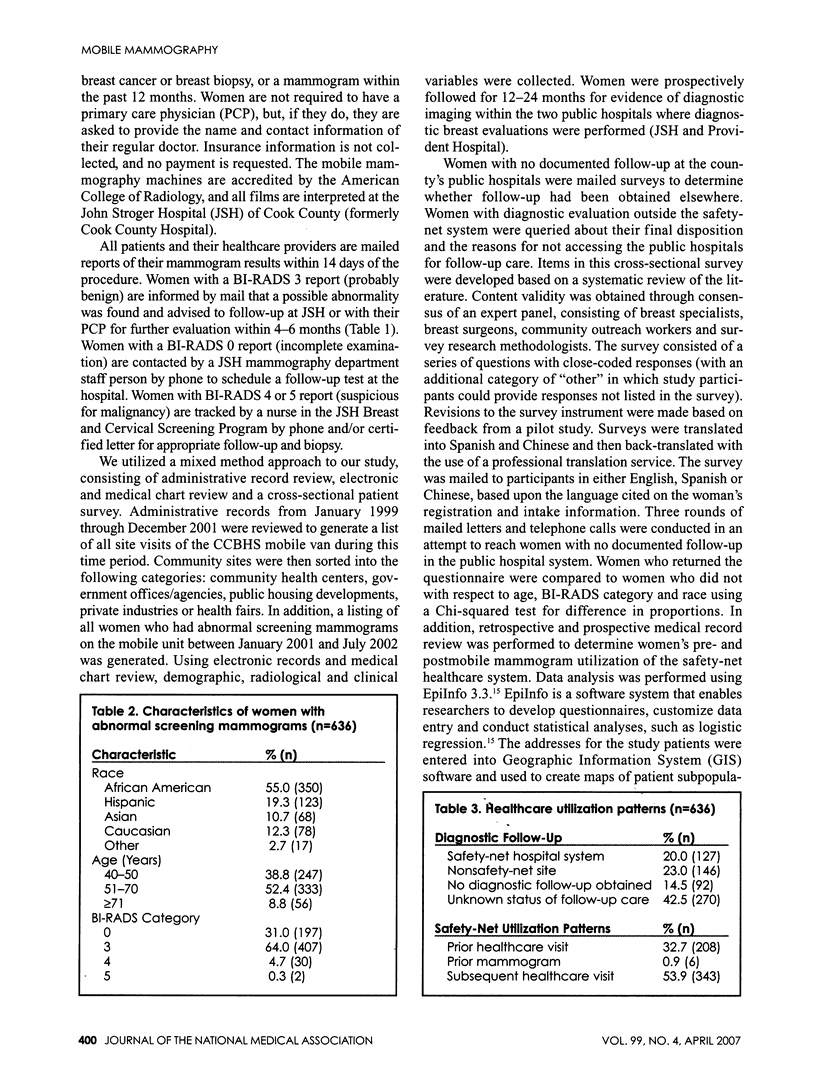

BACKGROUND: Mobile mammography can be useful in reaching medically underserved women. However, it is not known whether self-referral for mobile mammography is the best approach for reaching the most vulnerable populations. OBJECTIVES: 1) To describe the community outreach patterns of a county-sponsored mobile mammography unit, 2) To characterize the follow-up patterns for women with abnormal screening mammograms, and 3) to identify reasons why women screened on mobile units seek follow-up care outside of the safety-net system. METHODS: We prospectively followed women aged > or = 40 years who received mobile mammograms using electronic records and medical chart review, and surveyed women who had no evidence of diagnostic follow-up. We also reviewed administrative records to determine outreach patterns of the mobile mammography units. RESULTS: Seventy-five percent of mobile visits were with community-based organizations or community health centers. At least one quarter of women chose to follow-up outside of the safety-net for evaluation of abnormal screening mammograms. Of these, nearly 40% reported having insurance or a private physician as the primary reason for having diagnostic evaluation outside of the public hospital system. CONCLUSIONS: Despite serving primarily community-based facilities, self-referral for mobile mammography may not optimally target medically underserved women most in need of breast cancer screening.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blewett Lynn A., Beebe Timothy J. State efforts to measure the health care safety net. Public Health Rep. 2004 Mar-Apr;119(2):125–135. doi: 10.1177/003335490411900204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley Clare, Tamburini Marcello. Not-only-a-title. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003 Jan 6;1:1–1. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevarley F., White E. Recent trends in breast cancer mortality among white and black US women. Am J Public Health. 1997 May;87(5):775–781. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg Limin X., Li Frederick P., Hankey Benjamin F., Chu Kenneth, Edwards Brenda K. Cancer survival among US whites and minorities: a SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Program population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002 Sep 23;162(17):1985–1993. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn B. S., Gavin P., Worden J. K., Ashikaga T., Gautam S., Carpenter J. Community education programs to promote mammography participation in rural New York State. Prev Med. 1997 Jan-Feb;26(1):102–108. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeen A. N., White E. Breast cancer size and stage in Hispanic American women, by birthplace: 1992-1995. Am J Public Health. 2001 Jan;91(1):122–125. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeen A. N., White E., Taylor V. Ethnicity and birthplace in relation to tumor size and stage in Asian American women with breast cancer. Am J Public Health. 1999 Aug;89(8):1248–1252. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz Paula M., Keeton Kristie, Romano Leah, Degroff Amy. Case management in public health screening programs: the experience of the national breast and cervical cancer early detection program. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004 Nov-Dec;10(6):545–555. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200411000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Christopher I., Malone Kathleen E., Daling Janet R. Differences in breast cancer stage, treatment, and survival by race and ethnicity. Arch Intern Med. 2003 Jan 13;163(1):49–56. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy E. P., Burns R. B., Coughlin S. S., Freund K. M., Rice J., Marwill S. L., Ash A., Shwartz M., Moskowitz M. A. Mammography use helps to explain differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis between older black and white women. Ann Intern Med. 1998 May 1;128(9):729–736. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-9-199805010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisano E. D., Yankaskas B. C., Ghate S. V., Plankey M. W., Morgan J. T. Patient compliance in mobile screening mammography. Acad Radiol. 1995 Dec;2(12):1067–1072. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(05)80517-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer M. E., French M. T., Ullmann S. G., McCoy C. B. Cost-effectiveness of detecting breast cancer in lower socioeconomic status African American and Hispanic women through mobile mammography services. Med Care Res Rev. 1998 Mar;55(1):99–115. doi: 10.1177/107755879805500106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk R. B. Hidden costs of mobile mammography: is subsidization necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992 Jun;158(6):1243–1245. doi: 10.2214/ajr.158.6.1590115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]