Abstract

Helicobacter pylori adherence in the human gastric mucosa involves specific bacterial adhesins and cognate host receptors. Here, we identify sialyl-dimeric-Lewis × glycosphingolipid as a receptor for H. pylori and show that H. pylori infection induced formation of sialyl-Lewis × antigens in gastric epithelium in humans and in a Rhesus monkey. The corresponding sialic acid–binding adhesin (SabA) was isolated with the “retagging” method, and the underlying sabA gene (JHP662/HP0725) was identified. The ability of many H. pylori strains to adhere to sialylated glycoconjugates expressed during chronic inflammation might thus contribute to virulence and the extraordinary chronicity of H. pylori infection.

Helicobacter pylori persistently infects the gastric mucosa of more than half of all people worldwide, causes peptic ulcer disease, and is an early risk factor for gastric cancer (1). Many H. pylori strains express adhesin proteins that bind to specific host-cell macromolecule receptors (2). This adherence may be advantageous to H. pylori by helping to stabilize it against mucosal shedding into the gastric lumen and ensuring good access to nourishing exudate from gastric epithelium that has been damaged by the infection. The best defined H. pylori adhesin-receptor interaction found to date is that between the Leb blood group antigen binding adhesin, BabA, a member of a family of H. pylori outer membrane proteins, and the H, Lewis b (Leb), and related ABO antigens (3-5). These fucose-containing blood group antigens are found on red blood cells and in the gastrointestinal mucosa (6). Blood group–O individuals suffer disproportionately from peptic ulcer disease, suggesting that bacterial adherence to the H and Leb antigens affects the severity of infection (7). Additional H. pylori–host macromolecule interactions that do not involve Leb-type antigens have also been reported (8).

H. pylori is a genetically diverse species, with strains differing markedly in virulence. Strains from persons with overt disease generally carry the cag-pathogenicity island (cag-PAI) (9, 10), which mediates translocation of CagA into host cells, where it is tyrosine phosphorylated and affects host cell signaling (11). Leb antigen binding is most prevalent among cag+ strains from persons with overt disease (4, 12). Separate studies using transgenic mice that express the normally absent Leb antigen suggest that H. pylori adherence exacerbates inflammatory responses in this model (13). Taken together, these results point to the pivotal role of H. pylori adherence in development of severe disease.

Leb antigen–independent binding

Earlier studies identified nearly identical babA genes at different H. pylori chromosomal loci, each potentially encoding BabA. The babA2 gene encodes the complete adhesin, whereas babA1 is defective because sequences encoding the translational start and signal peptide are missing (4). Our experiments began with analyses of a babA2–knockout mutant derivative of the reference strain CCUG17875 (hereafter referred to as 17875). Unexpectedly, this 17875 babA2 mutant bound to gastric mucosa from an H. pylori–infected patient with gastritis.

A 17875 derivative with both babA genes inactivated (babA1A2) was constructed (14). This babA1A2 mutant also adhered (Fig. 1, B and C), which showed that adherence was not due to recombination to link the silent babA1 gene with a functional translational start and signal sequence. Pretreatment with soluble Leb antigen (structures in table S1) resulted in >80% lower adherence by the 17875 parent strain (Figs. 1E and 3C) but did not affect adherence by its babA1A2 derivative (Figs. 1F and 3C).

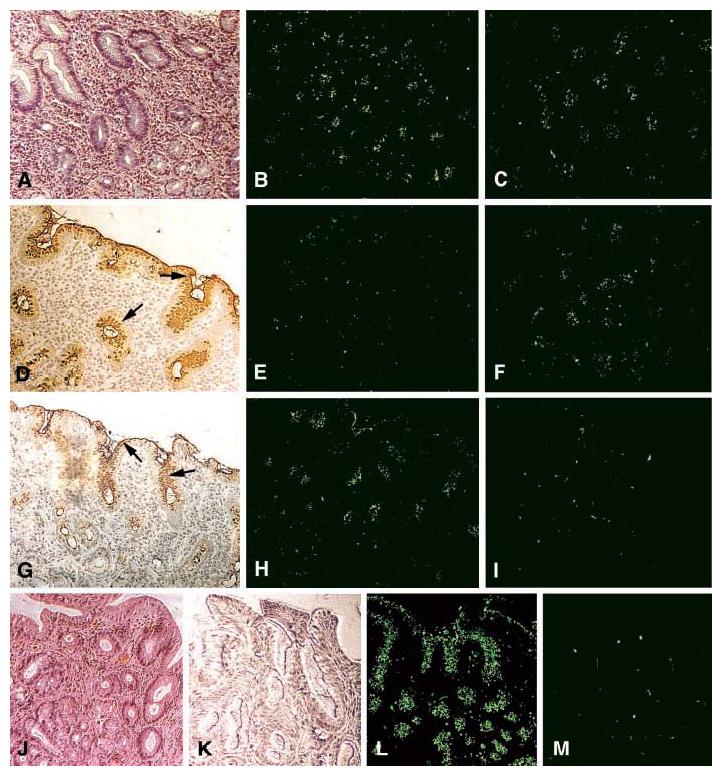

Fig. 1.

The sLex antigen confers adherence of H. pylori to the epithelium of H. pylori–infected (strain WU12) human gastric mucosa (Fig. 3A). H/E staining reveals mucosal inflammation (A). The 17875 parent strain (B) and the babA1A2 mutant (C) both adhere to the gastric epithelium. The surface epithelium stains positive (arrows) with both the Leb mAb (D) and sLex mAb (G) [AIS described in (14)]. The 17875 strain and babA1A2 mutant responded differently after pretreatment (inhibition) with soluble Leb antigen [(E) and (F), respectively)], or with soluble sLex antigen [(H) and (I), respectively)]. In conclusion, the Leb antigen blocked binding of the 17875 strain, whereas the sLex antigen blocked binding of the babA1A2 mutant. H/E-stained biopsy with no H. pylori infection (J). No staining was detected with the sLex mAb (K). Here, strain 17875 adhered (L), in contrast to the babA1A2 mutant (M), because noninflamed gastric mucosa is low in sialylation (K).

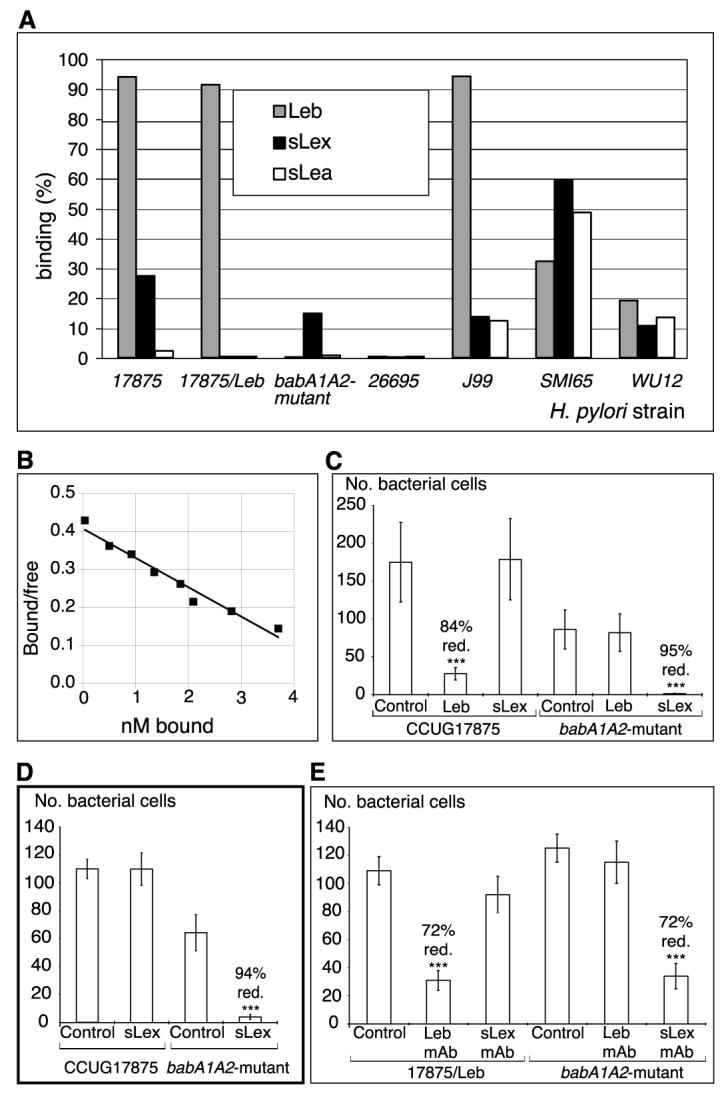

Fig. 3.

H. pylori binds sialylated antigens. (A) H. pylori strains and mutants (14) were analyzed for binding to different 125I-labeled soluble fucosylated and sialylated (Lewis) antigen-conjugates [RIA in (14)]. The bars give bacterial binding, and conjugates used are given in the diagram. (B) For affinity analyses (16), the sLex conjugate was added in titration series. The babA1A2 mutant was incubated for 3 hours with the s(mono)Lex conjugate to allow for equilibrium in binding, which demonstrates an affinity (Ka) of 1 × 108 M−1. (C) Adherence of strain 17875 (sLex and Leb-antigen binding) and babA1A2 mutant to biopsy with inflammation and H. pylori infection, as scored by the number of bound bacteria after pretreatment with soluble Leb (Fig. 1, E and F) or sLex antigen (Fig. 1, H and I) (14). The Leb antigen reduced adherence of strain 17875 by >80%, whereas the sLex antigen abolished adherence of the babA1A2 mutant. (D) Adherence of strain 17875 and babA1A2 mutant to biopsy of Leb mouse gastric mucosa was scored by the number of bound bacteria after pretreatment with sLex conjugate. Adherence by the babA1A2 mutant was abolished (Fig. 2A, vi), while adherence by strain 17875 was unperturbed (Fig. 2A, v). (E) Adherence of spontaneous phase variant strain 17875/Leb (Leb-antigen binding only in Fig. 3A) and babA1A2 mutant was analyzed after pretreatment of histo-sections of human gastric mucosa with mAbs recognizing the Leb antigen or the sdiLex antigen (FH6), with efficient inhibition of adherence of both strain 17875/Leb and the babA1A2 mutant, respectively. Value P < 0.001 (***), value P < 0.01 (**), value P < 0.05 (*).

In contrast to binding to infected gastric mucosa (Fig. 1, A to I), the babA1A2 mutant did not bind to healthy gastric mucosa from a person not infected with H. pylori (Fig. 1, J to M), whereas the 17875 parent strain bound avidly (Fig. 1, M versus L). These results implicated another adhesin that recognizes a receptor distinct from the Leb antigen and possibly associated with mucosal inflammation.

Adherence was also studied in tissue from a special transgenic mouse that produces Leb antigen in the gastric mucosa, the consequence of expression of a human-derived α1,3/4 fucosyltransferase (FT) (15). Strain 17875 and the babA1A2 mutant each adhered to Leb mouse gastric epithelium (Fig. 2A, ii and iii), whereas binding of each strain to the mucosa of nontransgenic (FVB/N) mice was poor and was limited to the luminal mucus. Thus, Leb mice express additional oligosaccharide chains (glycans), possibly fucosylated, but distinct from the Leb antigen that H. pylori could exploit as a receptor.

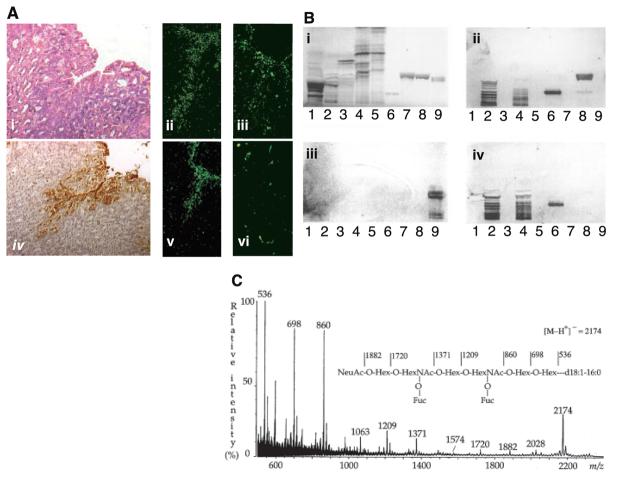

Fig. 2.

(A) The sLex antigen confers adherence of H. pylori to the transgenic Leb mouse gastric mucosa. H/E-stained biopsy of Leb mouse gastric mucosa (i). The 17875 strain (ii) and babA1A2 mutant (iii) both adhered to the surface epithelium, which stained positive with the sLex mAb (iv). Adherence by the babA1A2 mutant was lost (vi), while adherence by the 17875 strain was unperturbed (v), after pretreatment of the bacteria with soluble sLex antigen. (B) H. pylori binds to fucosylated gangliosides such as the sLex GSL. GSLs were separated on TLC and chemically stained (i) (14). Chromatograms were probed with sLex mAb (ii), the 17875 strain (iii), and the babA1A2 mutant (iv). Lanes contained acid (i.e., sialylated) GSLs of calf brain, 40 μg; acid GSLs of human neutrophil granulocytes, 40 μg; sample number 2 after desialylation, 40 μg; acid GSLs of adenocarcinoma, 40 μg; sample number 4 after desialylation, 40 μg; sdiLex GSL, 1 μg; sLea GSL, 4 μg; s(mono)Lex GSL, 4 μg; and Leb GSL, 4 μg. Binding results are summarized in table S1. (C) The high-affinity H. pylori GSL receptor was structurally identified by negative ion fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry. The molecular ion (M-H+)− at m/z 2174 indicates a GSL with one NeuAc, two fucoses, two N-acetylhexosamines, four hexoses, and d18 :1-16:0; and the sequence NeuAcHex(Fuc)HexNAc-Hex(Fuc)HexNAcHexHex was deduced. 1H-NMR spectroscopy resolved the sdiLex antigen; NeuAcα2.3Galβ1.4(Fucα1.3)GlcNAcβ1.3Galβ1.4(Fucα1.3) GlcNAcβ1.3Galβ1.4Glcβ1Cer (14).

sdiLex antigen–mediated binding

To search for another receptor, thin-layer chromatography (TLC)–separated glycosphingolipids (GSLs) were overlaid with H. pylori cells and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), as appropriate. These tests (i) showed that the babA1A2 mutant bound acid GSLs (Fig. 2B, iv, lanes 2 and 4), (ii) confirmed that it did not bind Leb GSL (lane 9), (iii) showed that its binding was abrogated by desialylation (lanes 3 and 5), and (iv) revealed that it did not bind sialylated GSLs of nonhuman origin (lane 1) [table S1, numbers 2 to 5, in (16)] (indicating that sialylation per se is not sufficient for adherence). In addition, the binding pattern of the babA1A2 mutant matched that of the mAb against sLex (Fig. 2B, ii versus iv), except that sLex-mono-GSL was bound more weakly by the babA1A2 mutant than by the mAb (Fig. 2B, iv) and no binding to sialyl-Lewis a-GSL was detected (table S1). Thus, the babA1A2 mutant preferably binds sialylated gangliosides, possibly with multiple Lex (fucose-containing) motifs in the core chain (thus, slower migration on TLC).

The babA1A2-mutant strain was next used to purify a high-affinity binding GSL from human adenocarcinoma tissue (14). The H. pylori–binding GSL was identified by mass spectrometry and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) as the sialyl-dimeric-Lewis × antigen, abbreviated as the sdiLex antigen (Fig. 2, B and C) (14).

Further tests with soluble glycoconjugates showed that the 17875-parent strain bound both sLex and Leb antigens, whereas its derivative bound only sLex (Fig. 3A). Pretreatment of the babA1A2 mutant with sLex conjugate reduced its in situ adherence by more than 90% (Figs. 1I and 3C) (14) but did not affect adherence of the 17875 parent strain (Figs. 1H and 3C). Similarly, pretreatment of tissue sections with an mAb that recognizes sdiLex reduced adherence by the babA1A2 mutant by 72% (Fig. 3E).

Titration experiments showed that the babA1A2 mutant exhibited high affinity for the sdiLex GSLs, with a level of detection of 1 pmol (Fig. 2B, iv) (table S1, number 8). At least 2000-fold more (2 nmol) of the shorter sialyl-(mono)-Lewis × GSL was needed for binding (table S1, number 7). In contrast, its affinity (Ka) for soluble conjugates was similar for mono and dimeric forms of sLex, 1 × 108 M−1 and 2 × 108 M−1, respectively (Fig. 3B) (16). These patterns suggest that the sialylated binding sites are best presented at the termini of extended core chains containing multiple Lewis × motifs, such as GSLs in cell membranes. Such optimization of steric presentation would be less important for soluble receptors.

The Scatchard analyses (16) also estimated that 700 sLex-conjugate molecules were bound per babA1A2-mutant bacterial cell (Fig. 3B), a number similar to that of Leb conjugates bound per cell of strain 17875.

Clinical isolates

A panel of 95 European clinical isolates was analyzed for sLex binding (14). Thirty-three of the 77 cagA+ strains (43%) bound sLex, but only 11% (2 out of 18) of cagA− strains (P < 0.000). However, deletion of the cagPAI from strain G27 did not affect sLex binding, as had also been seen in studies of cagA and Leb-antigen binding. Out of the Swedish clinical isolates, 39% (35 out of 89) bound sLex, and the great majority of these sLex-binding isolates, 28 out of 35 (80%), also bound the Leb antigen. Fifteen of the 35 (43%) sLex-binding isolates also bound the related sialyl-Lewis a antigen (sLea) (table S1, number 6), whereas none of the remaining 54 sLex-nonbinding strains could bind to sLea. The clinical isolates SMI65 and WU12 (the isolate from the infected patient in Fig. 1, A to M) illustrate such combinations of binding modes (Fig. 3A). Of the two strains with sequenced genomes, strain J99 (17) bound sLex, sLea, and Leb antigens, whereas strain 26695 (18) bound none of them (Fig. 3A).

Binding to inflamed tissue

Gastric tissue inflammation and malignant transformation each promote synthesis of sialylated glycoconjugates (19), which are rare in healthy human stomachs (20). Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the sialylated antigens were located to the apical surfaces of the surface epithelial cells (fig. S2). To study gastric mucosal sialylation in an H. pylori context, gastric biopsies from 29 endoscopy patients were scored for binding by the babA1A2 mutant and by the 17875 strain in situ, and for several markers of inflammation (table S2A) (14). Substantial correlations were found between babA1A2-mutant adherence and the following parameters: (i) levels of neutrophil (PMN) infiltration, 0.47 (P < 0.011); (ii) lymphocyte/plasma cell infiltration, 0.46 (P < 0.012); (iii) mAb staining for sLex in surface epithelial cells and in gastric pit regions, 0.52 (P < 0.004); and (iv) histological gastritis score, 0.40 (P < 0.034). In contrast, there was no significant correlation between babA1A2-mutant binding in situ and H. pylori density in biopsies from natural infection (0.14, P < 0.47), nor between any inflammatory parameter and in situ adherence of strain 17875 (Leb and sLex binding). The series of 29 patient biopsies was then compared to a series of six biopsies of H. pylori–noninfected individuals, and a considerable difference was found to be due to lower adherence of the babA1A2 mutant (P < 0.000) (table S2B), whereas strain 17875 showed no difference.

Binding to infected tissue

Biopsy material from a Rhesus monkey was used to directly test the view that H. pylori infection stimulates expression of sialylated epithelial glycosylation patterns that can then be exploited by H. pylori for adherence [monkey biopsies in (14)]. This monkey (21) had been cleared of its natural H. pylori infection, and gastritis declined to baseline. Gastric biopsies taken at 6 months post-eradication showed expression of sLex in the gastric gland region (Fig. 4A) and no expression in the surface epithelium (Fig. 4A). In situ adherence of the babA1A2 mutant was limited to gastric glands and was closely matched to the sLex expression pattern (Fig. 4B). No specific adherence to the surface epithelium was seen (Fig. 4B).

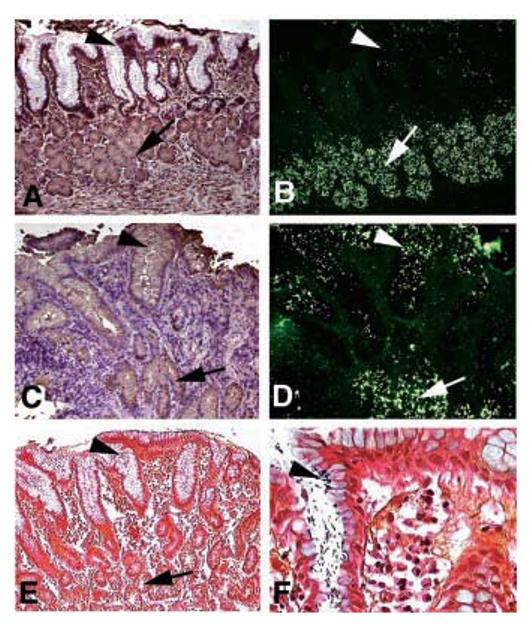

Fig. 4.

Infection induces expression of sLex antigens that serve as binding sites for H. pylori adherence. (A) and (B) came from a Rhesus monkey with healthy gastric mucosa. (C)to(F) came from the same Rhesus monkey 9 months after established reinfection with virulent clinical H. pylori isolates. Sections were analyzed with the sLex mAb (A) and (C) and by adherence in situ with the babA1A2 mutant (B) and (D). In the healthy animal, both the sLex mAb staining and adherence of the babA1A2 mutant is restricted to the deeper gastric glands [(A) and (B), arrows] [i.e., no mAb-staining of sLex antigens and no babA1A2-mutant bacteria present in the surface epithelium (A) and (B), arrowhead]. In contrast, in the H. pylori–infected and inflamed gastric mucosa, the sLex antigen is heavily expressed in the surface epithelium [(C), arrowhead with brownish immunostaining], in addition to the deeper gastric glands [(C), arrow]. The up-regulated sLex antigen now supports massive colocalized adherence of the babA1A2 mutant in situ [(D), ar- rowhead] in addition to the constant binding to the deeper gastric glands [(B) and (D), arrow]. The established infection was visualized by Genta stain, where the H. pylori microbes were present in the surface epithelium [(E) and (F), arrowhead; (F) is at a higher magnification], while no microbes were detected in the deeper gastric glands [(E), arrow].

At 6 months post-therapy, this gastritis-free animal had been experimentally infected with a cocktail of H. pylori strains, of which the J166 strain (a cagA-positive, Leb and sLex binding isolate) became predominant a few months later. This led to inflammation, infiltration by lymphocytes [Fig. 4C, bluish due to hematoxyline/eosine (H/E)–staining], and microscopic detection of H. pylori infection (Fig. 4, E and F) (21). The virulent H. pylori infection led to strong sLex-antigen expression in the surface epithelium (Fig. 4C) and maintained expression in the deeper gastric glands (Fig. 4C); thus, a bi-layered expression mode supported strong binding of the babA1A2 mutant to both regions (Fig. 4D). Bacterial pretreatment with sLex conjugate eliminated surface epithelial adherence and reduced gastric gland adherence by 88%. Thus, persistent H. pylori infection up-regulates expression of sLex antigens, which H. pylori can exploit for adherence to the surface epithelium.

Binding to Leb transgenic mouse gastric epithelium

We analyzed gastric mucosa of Leb mice for sLex antigen–dependent H. pylori adherence in situ [AIS, in (14)]. Pretreatment with the sLex conjugate reduced binding by babA1A2-mutant bacteria by more than 90% (Figs. 2A, vi, and 3D) but did not affect binding by its 17875 parent (Figs. 2A, v, and 3D). In comparison, pretreatment with soluble Leb antigen decreased adherence by >80% of the 17875 strain (Leb and sLex binding), whereas binding by the babA1A2 mutant was not affected. mAb tests demonstrated sLex antigen in the gastric surface epithelium and pits of Leb mice (Fig. 2A, iv). That is, these mice are unusual in producing sialyl as well as Leb glycoconjugates (even without infection), which each serve as receptors for H. pylori.

A finding that H. pylori pretreatment with Leb conjugate blocked its adherence to Leb mouse tissue, whereas sLex pretreatment did not, had been interpreted as indicating that H. pylori adherence is mediated solely by Leb antigen (22). However, because strain 17875 and its babA1A2 mutant bound similar levels of soluble sLex conjugate (Fig. 3A), soluble Leb seems to interfere sterically with interactions between sLex-specific H. pylori adhesins and sLex receptors in host tissue (see also Fig. 1, E versus F). Because an excess of soluble sLex did not affect H. pylori binding to Leb receptors [Figs. 1H and 3C (in humans) and Figs. 2A, v, and 3D (in Leb-mice)], the steric hindrance is not reciprocal. Further tests showed that liquid phase binding is distinct. A 10-fold excess of soluble unlabeled Leb conjugate (3 μg) along with 300 ng of 125I-sLex conjugate did not affect strain 17875 binding to soluble sLex glycoconjugate.

Thus, soluble Leb conjugates interfere with sLex-mediated H. pylori binding specifically when the sLex moieties are constrained on surfaces. The lack of reciprocity in these Leb-sLex interference interactions contributes to our model of receptor positioning on cell surfaces.

SabA identified

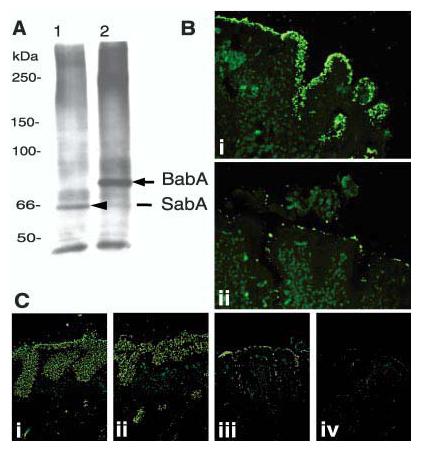

We identified the sLex-binding adhesin by “retagging.” This technique exploits a receptor-bound multifunctional biotinylated crosslinker, and ultraviolet (UV) irradiation to mediate transfer of the biotin tag to the bound adhesin (4). Here, we added the crosslinker to sLex conjugate and used more UV exposure (14) than had been used to isolate the BabA adhesin (4) to compensate for the lower affinity of the sLex-than the Leb-specific adhesin for cognate soluble receptors (Fig. 3B). Strain J99 was used, and a 66-kDa protein was recovered (Fig. 5A). Four peptides identified by mass spectrometry (MS)–matched peptides encoded by gene JHP662 in strain J99 (17) (gene HP0725 in strain 26695) (18). Two of the four peptides also matched those from the related gene JHP659 (HP0722) (86% protein level similarity to JHP662) (fig. S1).

Fig. 5.

Retagging of SabA and identification of the corresponding gene, sabA. After contact-dependent retagging (of the babA1A2 mutant) with crosslinker labeled sLex conjugate, the 66-kDa biotin-tagged adhesin SabA [(A), lane 1] was identified by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis/steptavidin-blot, magnetic-bead-purified, and analyzed by MS for peptide masses (14). As a control, the Leb conjugate was used to retag 17875 bacteria, which visualized the 75-kDa BabA adhesin [(A), lane 2] (4). (B) The J99/JHP662::cam (sabA) mutant does not bind the sLex antigen but adheres to human gastric epithelium [(B), i], due to the BabA-adhesin, because pretreatment with soluble Leb antigen inhibited binding to the epithelium [(B), ii]. (C) The J99 wild-type strain (which binds both Leb and sLex antigens) [(C), i] and the J99 sabA mutant (which binds Leb antigen only) [(C), ii] both exhibit strong adherence to the gastric mucosa. In comparison, the J99 babA mutant binds by lower-affinity interactions [(C), iii], while the J99 sabAbabA mutant, which is devoid of both adherence properties, does not bind to the gastric mucosa [(C), iv].

To critically test if JHP662 or JHP659 encodes SabA, we generated camR insertion alleles of each gene in strain J99. Using radiolabeled glycoconjugates, we found that both sLex and sLea antigen–binding activity was abolished in the JHP662 (sabA) mutant, but not in the JHP659 (sabB) mutant. Thus, the SabA adhesin is encoded by JHP662 (HP0725). This gene encodes a 651-aa protein (70 kDa) and belongs to the large hop family of H. pylori outer membrane protein genes, including babA (17, 18). The sabA gene was then identified by PCR in six sLex-binding and six non–sLex-binding Swedish isolates, which suggests that sabA is present in the majority of H. pylori isolates (14).

Parallel studies indicated that the sabA inactivation did not affect adherence mediated by the BabA adhesin (Fig. 5B, i) and that pretreatment of the J99sabA mutant with soluble Leb antigen prevented its binding to gastric epithelium (Fig. 5B, ii). This implies that the SabA and BabA adhesins are organized and expressed as independent units. Nevertheless, Leb conjugate pretreatment of J99 (BabA+ and SabA+) might have interfered with sLex antigen–mediated adherence (see Fig. 1E). To determine if this was a steric effect of the bulky glycoconjugate on exposure of SabA adhesin, single babA and sabA mutant J99 derivatives were used to further analyze Leb and sLex adherence (Fig. 5C, i to iv). Both single mutants adhered to the inflamed gastric epithelial samples, whereas the babAsabA (double) mutant was unable to bind this same tissue.

Instability of sLex binding

When screening for SabA mutants, we also analyzed single colony isolates from cultures of parent strain J99 (which binds both sLex and Leb antigens) (Fig. 3A), which indicated that 1% of colonies had spontaneously lost the ability to bind sLex. Similar results were obtained with strain 17875 (Fig. 3A) with an OFF (non–sLex-binding) variant called 17875/Leb. In contrast, each of several hundred isolates tested retained Leb antigen–binding capacity.

Upstream and within the start of the sabA gene are poly T/CT tracts that should be hotspots for ON/OFF frameshift regulation [see HP0725 in (18)], which might underlie the observed instability of sLex-binding activity. Both strains' genome sequences, 26695 and J99, demonstrate CT repeats that suggest sabA to be out of frame (six and nine CTs, respectively) (17, 18). Four sLex-binding and four non–sLex-binding Swedish isolates, and in addition strain J99, were analyzed by PCR for CT repeats, and differences in length were found between strains. Ten CT repeats [as compared to nine in (17)] were found in the sLex-binding J99 strain, which puts this ORF in frame, and could thus explain the ON bindings. These results further support the possibility for a flexible locus that confers ON/OFF binding properties (23).

Dynamics of sialylation during health and disease

Our analyses of H. pylori adherence provide insight into human responses to persistent infections, where gastritis and inflammation elicit appearance of sdiLex antigens and related sialylated carbohydrates in the stomach mucosa, which cag+ (virulent) H. pylori strains by adaptive mechanisms exploit as receptors in concert with the higher affinity binding to Leb. These two adherence modes may each benefit H. pylori by improving access to nutrients leached from damaged host tissues, even while increasing the risk of bactericidal damage by these same host defenses (Fig. 6). In the endothelial lining, sialylated Lewis-glycans serve as receptors for selectin cell adhesion proteins that help guide leukocyte migration and thus regulate strength of response to infection or injury (24). For complementary attachment, the neutrophils themselves also express sialylated Lewis glycans, and such neutrophil glycans allow binding and infection by human granulocytic erlichiosis (25). However, sialylated glycoconjugates are low in healthy gastric mucosa but are expressed during gastritis. This sialylation was correlated with the capacity for SabA-dependent, but not BabA-dependent, H. pylori binding in situ. Our separate tests on Rhesus monkeys for experimental H. pylori infection confirmed that gastric epithelial sialylation is induced by H. pylori infection. In accord with this, high levels of sialylated glycoconjugates have been found in H. pylori–infected persons, which decreased after eradication of infection and resolution of gastritis (26). Thus, a sialylated carbohydrate used to signal infection and inflammation and to guide defense responses can be co-opted by H. pylori as a receptor for intimate adherence.

Fig. 6.

H. pylori adherence in health and disease. This figure illustrates the proficiency of H. pylori for adaptive multistep mediated attachment. (A) H. pylori (in green) adherence is mediated by the Leb blood group antigen expressed in glycoproteins (blue chains) in the gastric surface epithelium (the lower surface) (3, 32). H. pylori uses BabA (green Y's) for strong and specific recognition of the Leb antigen (4). Most of the sLex-binding isolates also bind the Leb antigen (SabA, in red Y's). (B) During persistent infection and chronic inflammation (gastritis), H. pylori triggers the host tissue to retailor the gastric mucosal glycosylation patterns to up-regulate the inflammation-associated sLex antigens (red host, triangles). Then, SabA (red Y structures) performs Selectin-mimicry by binding the sialyl-(di)-Lewis x/a glycosphingolipids, for membrane close attachment and apposition. (C) At sites of vigorous local inflammatory response, as illustrated by the recruited activated white blood cell (orange “bleb”), those H. pylori subclones that have lost sLex-binding capacity due to ON/OFF frameshift mutation might have gained local advantage in the prepared escaping of intimate contact with (sialylated) lymphocytes or other defensive cells. Such adaptation of bacterial adherence properties and subsequent inflammation pressure could be major contributors to the extraordinary chronicity of H. pylori infection in human gastric mucosa.

High levels of sialylated glycoconjugates are associated with severe gastric disease, including dysplasia and cancer (27, 28). Sialylated glycoconjugates were similarly abundant in parietal cell–deficient mice (22). sLex was also present in the gastric mucosa of transgenic Leb mice (Fig. 2A). Whether this reflects a previously unrecognized pathology stemming from the abnormal (for mice) gastric synthesis of α1.3/4FT or Leb antigen, or from fucosylation of already sialylated carbohydrates, is not known.

Persons with blood group O and “nonsecretor” phenotypes (lacking the ABO blood group–antigen synthesis in secretions such as saliva and milk) are relatively common (e.g., ∼45 and ∼15%, respectively, in Europe), and each group is at increased risk for peptic ulcer disease (29). The H1 and Leb antigens are abundant in the gastric mucosa of secretors (of blood group O) (6), but not in nonsecretors, where instead the sLex and sLea antigens are found (30). The blood group O–disease association was postulated to reflect the adherence of most cag+ H. pylori strains to H1 and Leb antigens (3). We now suggest that H. pylori adherence to sialylated glycoconjugates contributes similarly to the increased risk of peptic ulcer disease in nonsecretor individuals.

Adaptive and multistep–mediated attachment modes of H. pylori

Our findings that the SabA adhesin mediates binding to the structurally related sialyl-Lewis a antigen (sLea, in table S1) is noteworthy because sLea is an established tumor antigen (31) and marker of gastric dysplasia (27), which may further illustrate H. pylori capacity to exploit a full range of host responses to epithelial damage. The H. pylori BabA adhesin binds Leb antigen on glycoproteins (32), whereas its SabA adhesin binds sLex antigen in membrane glycolipids, which may protrude less from the cell surface. Thus, H. pylori adherence during chronic infection might involve two separate receptor-ligand, interactions—one at “arm's length” mediated by Leb, and another, more intimate, weaker, and sLex-mediated adherence. The weakness of the sLex-mediated adherence, and its metastable ON/OFF switching, may benefit H. pylori by allowing escape from sites where bactericidal host defense responses are most vigorous (Fig. 6C). In summary, we found that H. pylori infection elicits gastric mucosal sialylation as part of the chronic inflammatory response and that many virulent strains can exploit Selectin mimicry and thus “home in” on inflammation-activated domains of sialylated epithelium, complementing the baseline level of Leb receptors. The spectrum of H. pylori adhesin–receptor interactions is complex and can be viewed as adaptive, contributing to the extraordinary chronicity of H. pylori infection in billions of people world-wide, despite human genetic diversity and host defenses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Clouse, H.M.T. El-Zimaity, D. Graham, and I. Anan for human biopsy material; J. Gordon and P. Falk for sections of Leb and FVB/N mouse stomach; L. Engstrand and A. Covacci for H. pylori strains; H. Clausen for the FH6 mAb; the Swedish NMR Centre, Göteborg University; P. Martin and Ö. Furberg for digital art/movie work; and J. Carlsson for critical reading of the manuscript. Supported by the Umeå University Biotechnology Fund, Swedish Society of Medicine/Bengt Ihre's Fund, Swedish Society for Medical Research, Lion's Cancer Research Foundation at Umeå University, County Council of Västerbotten, Neose Glycoscience Research Award Grant ( T.B.), Swedish Medical Research Council [11218 ( T.B.), 12628 (S.T.), 3967 and 10435 (K.-A.K.), 05975 (L.H.), and 04723 ( T.W.)], Swedish Cancer Society [4101-B00-03XAB ( T.B.) and 4128-B99-02XAB (S.T.)], SSF programs “Glycoconjugates in Biological Systems” ( T.B., S.T., and K.-A.K.), and “Infection and Vaccinology” ( T.B. and K.-A.K.), J. C. Kempe Memorial Foundation (J. M., L. F., and M.H.), Wallenberg Foundation (S.T. and K.-A.K), Lundberg Foundation (K.-A.K.), ALF grant from Lund University Hospital (T.W.), and grants from the NIH [RO1 AI38166, RO3 AI49161, RO1 DK53727 (D.B.)] and from Washington University (P30 DK52574). These experiments were conducted according to the principles in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,” Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, NRC, HHS/NIH Pub. No. 85–23. The opinions and assertions herein are private ones of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the DOD, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or the Defense Nuclear Agency.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material

www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/297/5581/573/DC1

Materials and Methods

References and Notes

- 1.Cover TL, et al. In: Principles of Bacterial Pathogenesis. Groisman EA, editor. Academic Press; New York: 2001. pp. 509–558. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerhard M, et al. In: Helicobacter pylori: Molecular and Cellular Biology. Suerbaum S, Achtman M, editors. Horizon Scientific Press; Norfolk, UK: 2001. chap. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borén T, et al. Science. 1993;262:1892. doi: 10.1126/science.8018146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ilver D, et al. Science. 1998;279:373. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurtig M, Borén T. in preparation.

- 6.Clausen H, Hakomori S. i. Vox Sang. 1989;56:1. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1989.tb03040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borén T, Falk P. Science. 1994;264:1387. doi: 10.1126/science.264.5164.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson KA. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:1. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Censini S, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:14648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akopyants NS, et al. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;28:37. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Segal ED, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:14559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerhard M, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:12778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guruge JL, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:3925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strains and culture, adherence in situ (AIS), H. pylori overlay to TLC, isolation and identification of the s-di-Lex GSL, apical localization of sLex antigen expression (fig. S2), retagging and identification of SabA/sabA, alignment of JHP662/JHP659 (fig. S1), construction of adhesin gene mutants, analyses of sabA by PCR, RIA and Scatchard analyses, gastric biopsies from patients and monkeys analyzed for H. pylori binding activity and inflammation, and a summary of H. pylori binding to glycosphingolipids (table S1) are available as supporting online material.

- 15.Falk PG, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:1515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scatchard G. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1949;51:660. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alm RA, et al. Nature. 1999;397:176. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomb JF, et al. Nature. 1997;388:539. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hakomori S. i. In: Gangliosides and Cancer. Oettgen HF, editor. VCH Publishers; New York: 1989. pp. 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madrid JF, et al. Histochemistry. 1990;95:179. doi: 10.1007/BF00266591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubois A, et al. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:90. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Syder AJ, et al. Mol. Cell. 1999;3:263. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnqvist A, et al. in preparation.

- 24.Alper J. Science. 2001;291:2338. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herron MJ, et al. Science. 2000;288:1653. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5471.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ota H, et al. Virchows Arch. 1998;433:419. doi: 10.1007/s004280050269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sipponen P, Lindgren J. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. Scand. 1986;94:305. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1986.tb02999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amado M, et al. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:462. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sipponen P, et al. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1989;24:581. doi: 10.3109/00365528909093093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakamoto J, et al. Cancer Res. 1989;49:745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Magnani JL, et al. Science. 1981;212:55. doi: 10.1126/science.7209516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falk P, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993;90:2035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.