Abstract

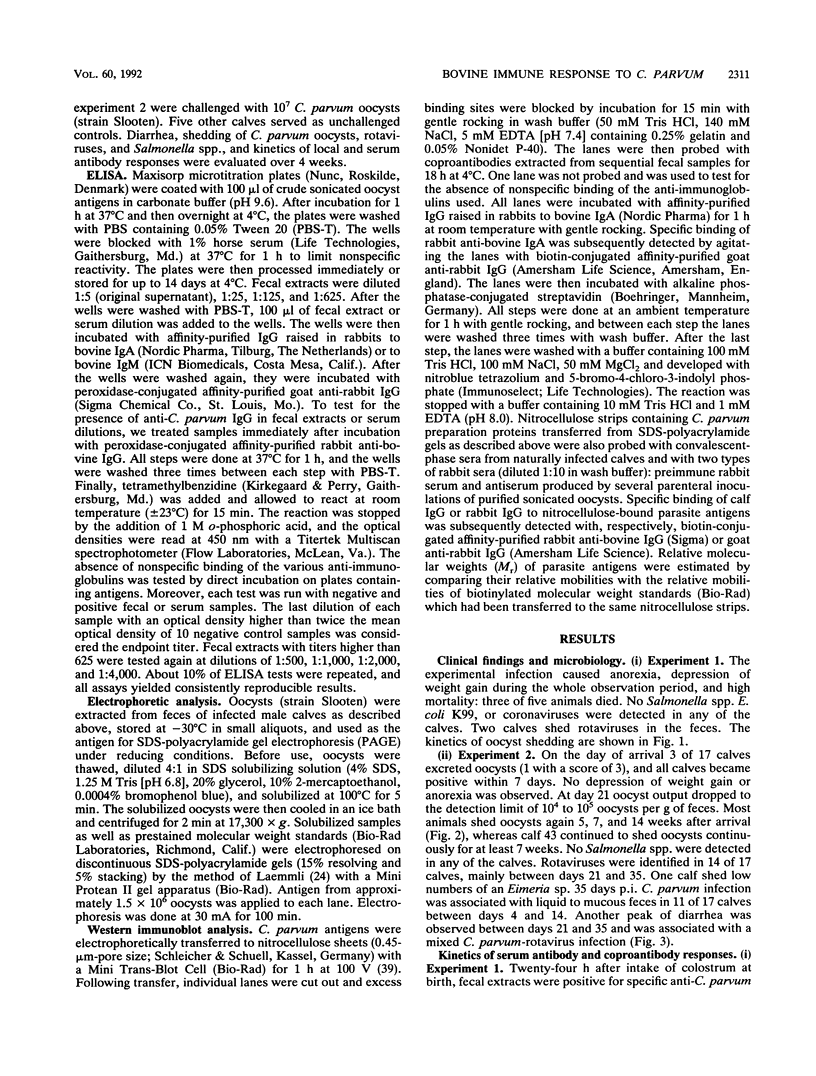

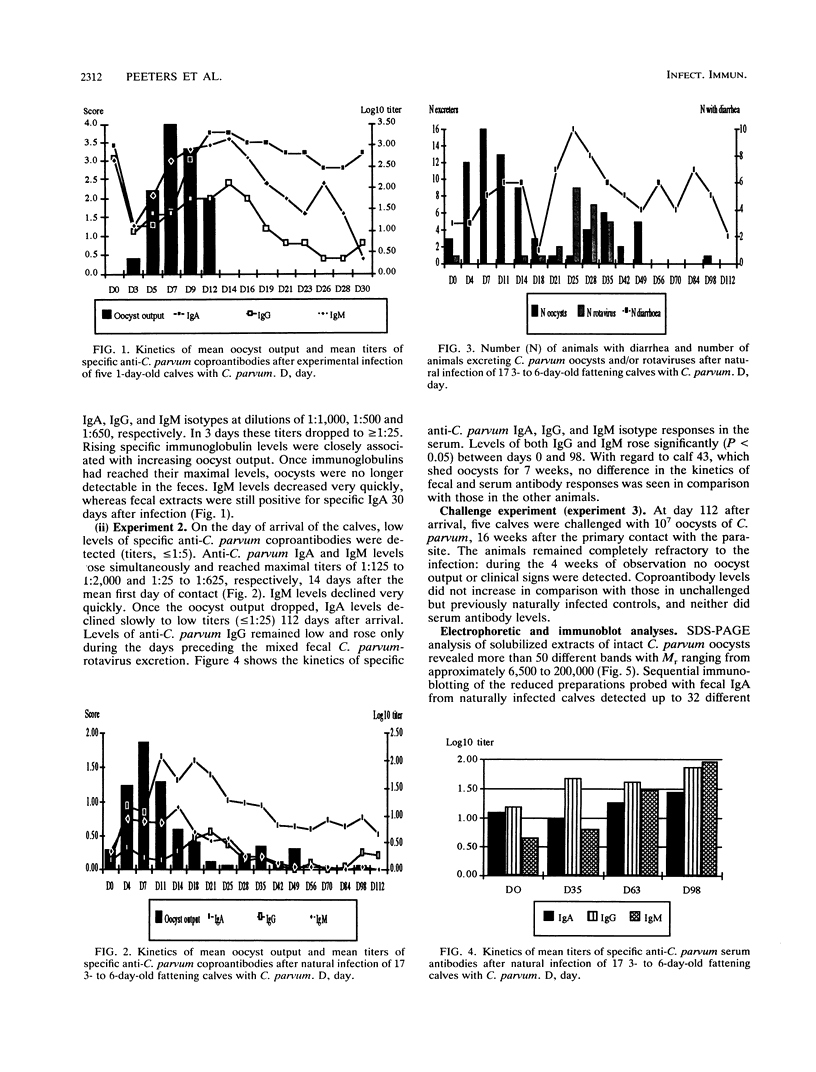

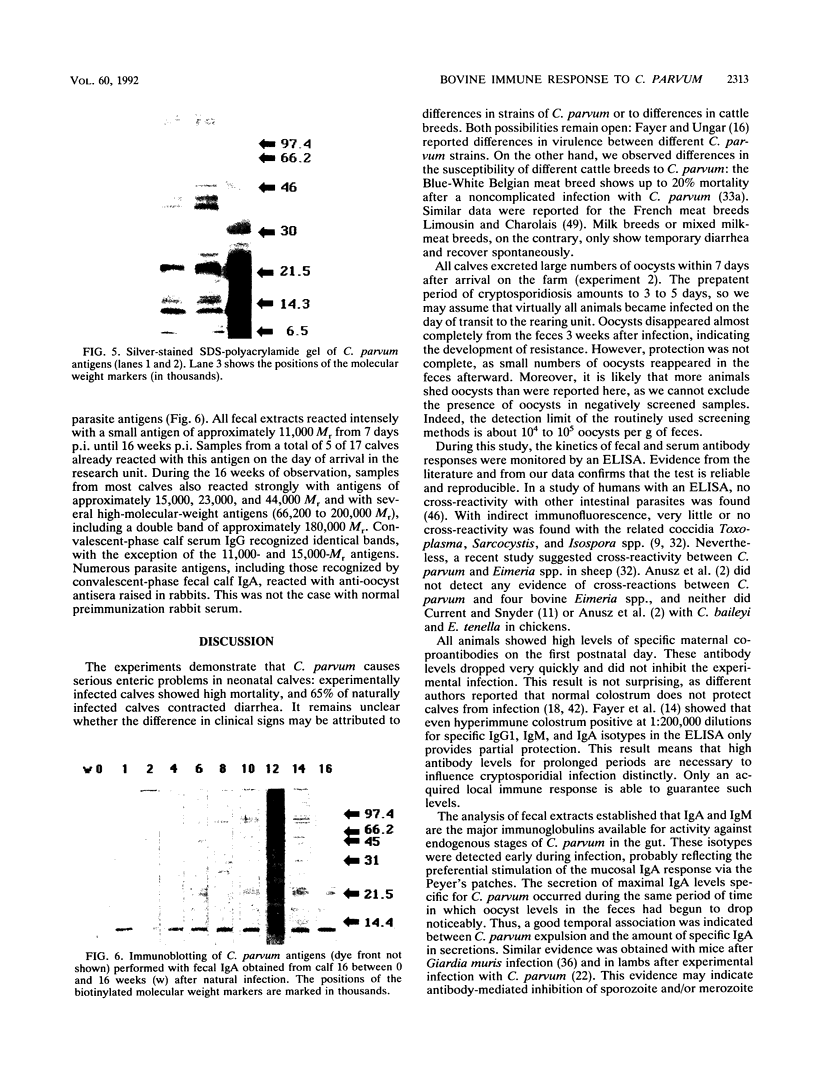

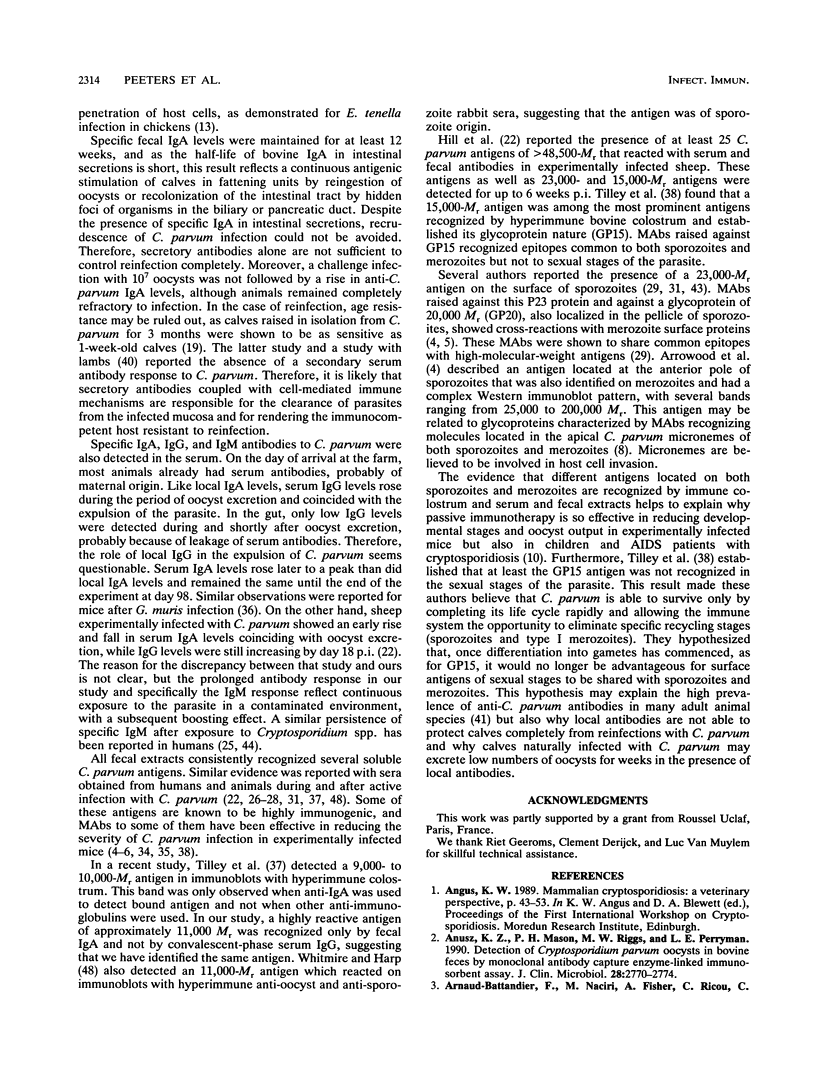

Fecal and serum anti-Cryptosporidium parvum immunoglobulin A (IgA), IgM, and IgG were monitored by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay after experimental and natural infection of calves with C. parvum. Although all experimentally infected calves showed high levels of colostral antibodies in the feces, they acquired C. parvum infection. Three of five animals died. Calves which acquired natural infection showed only diarrhea. Levels of colostral coproantibodies dropped quickly. Experimental infection was followed by a rise in local anti-C. parvum IgM levels from day 5 postinfection (p.i.). IgM peaked at day 14 p.i. and then disappeared quickly. Anti-C. parvum IgA levels rose between days 7 and 14 p.i. and decreased slowly. Rising levels of coproantibodies coincided with falling oocyst output. Fecal anti-C. parvum IgG levels rose slightly during oocyst output, and IgG disappeared 3 weeks p.i. Similar kinetics were established in naturally infected calves. Although fecal anti-C. parvum IgA levels declined slowly, reinfections were established 5, 7, and 14 weeks after the primary contact. Serum anti-C. parvum IgG levels rose during maximal oocyst excretion, whereas serum anti-C. parvum IgA levels peaked later than did local IgA levels. Challenge reinfection of naturally infected calves at day 112 was not followed by clinical signs or oocyst output or by a secondary antibody response. Sequential Western immunoblotting with fecal extracts revealed up to 32 different parasite antigens. Convalescent-phase sera recognized up to 23 antigens. Fecal IgA reacted intensely with antigens with relative molecular weights (M(r)) of approximately 11,000 and 15,000. These antigens were not recognized by convalescent-phase serum IgG. Both local IgA and serum IgG also showed strong reactions with 23,000- and 44,000-M(r) antigens and with several antigens of between 66,200 and 200,000 M(r). Most bands remained detectable for at least 16 weeks p.i.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anusz K. Z., Mason P. H., Riggs M. W., Perryman L. E. Detection of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in bovine feces by monoclonal antibody capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1990 Dec;28(12):2770–2774. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2770-2774.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud-Battandier F., Naceri M., Fischer A., Ricour C., Griscelli C., Yvore P. Cryptosporidiose intestinale : une cause nouvelle de diarrhée chez l'homme? Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1982 Dec;6(12):1045–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrowood M. J., Mead J. R., Mahrt J. L., Sterling C. R. Effects of immune colostrum and orally administered antisporozoite monoclonal antibodies on the outcome of Cryptosporidium parvum infections in neonatal mice. Infect Immun. 1989 Aug;57(8):2283–2288. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2283-2288.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorneby J. M., Hunsaker B. D., Riggs M. W., Perryman L. E. Monoclonal antibody immunotherapy in nude mice persistently infected with Cryptosporidium parvum. Infect Immun. 1991 Mar;59(3):1172–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1172-1176.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorneby J. M., Riggs M. W., Perryman L. E. Cryptosporidium parvum merozoites share neutralization-sensitive epitopes with sporozoites. J Immunol. 1990 Jul 1;145(1):298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnin A., Dubremetz J. F., Camerlynck P. Characterization of microneme antigens of Cryptosporidium parvum (Protozoa, Apicomplexa). Infect Immun. 1991 May;59(5):1703–1708. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.5.1703-1708.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P. N., Current W. L. Demonstration of serum antibodies to Cryptosporidium sp. in normal and immunodeficient humans with confirmed infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1983 Jul;18(1):165–169. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.1.165-169.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Current W. L., Garcia L. S. Cryptosporidiosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991 Jul;4(3):325–358. doi: 10.1128/cmr.4.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Current W. L., Snyder D. B. Development of and serologic evaluation of acquired immunity to Cryptosporidium baileyi by broiler chickens. Poult Sci. 1988 May;67(5):720–729. doi: 10.3382/ps.0670720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Antonio R. G., Winn R. E., Taylor J. P., Gustafson T. L., Current W. L., Rhodes M. M., Gary G. W., Jr, Zajac R. A. A waterborne outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in normal hosts. Ann Intern Med. 1985 Dec;103(6 ):886–888. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-6-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis P. J., Porter P. A mechanism for secretory IgA-mediated inhibition of the cell penetration and intracellular development of Eimeria tenella. Immunology. 1979 Mar;36(3):471–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R., Andrews C., Ungar B. L., Blagburn B. Efficacy of hyperimmune bovine colostrum for prophylaxis of cryptosporidiosis in neonatal calves. J Parasitol. 1989 Jun;75(3):393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R., Ungar B. L. Cryptosporidium spp. and cryptosporidiosis. Microbiol Rev. 1986 Dec;50(4):458–483. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.458-483.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harp J. A., Whitmire W. M. Cryptosporidium parvum infection in mice: inability of lymphoid cells or culture supernatants to transfer protection from resistant adults to susceptible infants. J Parasitol. 1991 Feb;77(1):170–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harp J. A., Woodmansee D. B., Moon H. W. Effects of colostral antibody on susceptibility of calves to Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Am J Vet Res. 1989 Dec;50(12):2117–2119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harp J. A., Woodmansee D. B., Moon H. W. Resistance of calves to Cryptosporidium parvum: effects of age and previous exposure. Infect Immun. 1990 Jul;58(7):2237–2240. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2237-2240.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes E. B., Matte T. D., O'Brien T. R., McKinley T. W., Logsdon G. S., Rose J. B., Ungar B. L., Word D. M., Pinsky P. F., Cummings M. L. Large community outbreak of cryptosporidiosis due to contamination of a filtered public water supply. N Engl J Med. 1989 May 25;320(21):1372–1376. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905253202103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine J. Eine einfache Nachweismethode für Kryptosporidien im Kot. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1982 May;29(4):324–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill B. D., Blewett D. A., Dawson A. M., Wright S. Analysis of the kinetics, isotype and specificity of serum and coproantibody in lambs infected with Cryptosporidium parvum. Res Vet Sci. 1990 Jan;48(1):76–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J. A. Economic impact of rotavirus and other neonatal disease agents of animals. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1978 Sep 1;173(5 Pt 2):573–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxer M. A., Alcantara A. K., Javato-Laxer M., Menorca D. M., Fernando M. T., Ranoa C. P. Immune response to cryptosporidiosis in Philippine children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990 Feb;42(2):131–139. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.42.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazo A., Barriga O. O., Redman D. R., Bech-Nielsen S. Identification by transfer blot of antigens reactive in the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in rabbits immunized and a calf infected with Cryptosporidium sp. Vet Parasitol. 1986 Aug;21(3):151–163. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(86)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luft B. J., Payne D., Woodmansee D., Kim C. W. Characterization of the Cryptosporidium antigens from sporulated oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum. Infect Immun. 1987 Oct;55(10):2436–2441. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.10.2436-2441.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumb R., Lanser J. A., O'Donoghue P. J. Electrophoretic and immunoblot analysis of Cryptosporidium oocysts. Immunol Cell Biol. 1988 Oct-Dec;66(Pt 5-6):369–376. doi: 10.1038/icb.1988.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumb R., Smith P. S., Davies R., O'Donoghue P. J., Atkinson H. M., Lanser J. A. Localization of a 23,000 MW antigen of Cryptosporidium by immunoelectron microscopy. Immunol Cell Biol. 1989 Aug;67(Pt 4):267–270. doi: 10.1038/icb.1989.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madore M. S., Rose J. B., Gerba C. P., Arrowood M. J., Sterling C. R. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium oocysts in sewage effluents and selected surface waters. J Parasitol. 1987 Aug;73(4):702–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead J. R., Arrowood M. J., Sterling C. R. Antigens of Cryptosporidium sporozoites recognized by immune sera of infected animals and humans. J Parasitol. 1988 Feb;74(1):135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters J. E., Mazás E. A., Masschelein W. J., Villacorta Martiez de Maturana I., Debacker E. Effect of disinfection of drinking water with ozone or chlorine dioxide on survival of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989 Jun;55(6):1519–1522. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.6.1519-1522.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perryman L. E., Riggs M. W., Mason P. H., Fayer R. Kinetics of Cryptosporidium parvum sporozoite neutralization by monoclonal antibodies, immune bovine serum, and immune bovine colostrum. Infect Immun. 1990 Jan;58(1):257–259. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.257-259.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs M. W., Perryman L. E. Infectivity and neutralization of Cryptosporidium parvum sporozoites. Infect Immun. 1987 Sep;55(9):2081–2087. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2081-2087.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider D. P., Underdown B. J. Quantitative and temporal analyses of murine antibody response in serum and gut secretions to infection with Giardia muris. Infect Immun. 1986 Apr;52(1):271–278. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.271-278.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley M., Fayer R., Guidry A., Upton S. J., Blagburn B. L. Cryptosporidium parvum (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) oocyst and sporozoite antigens recognized by bovine colostral antibodies. Infect Immun. 1990 Sep;58(9):2966–2971. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.2966-2971.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilley M., Upton S. J., Fayer R., Barta J. R., Chrisp C. E., Freed P. S., Blagburn B. L., Anderson B. C., Barnard S. M. Identification of a 15-kilodalton surface glycoprotein on sporozoites of Cryptosporidium parvum. Infect Immun. 1991 Mar;59(3):1002–1007. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.1002-1007.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H., Staehelin T., Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979 Sep;76(9):4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzipori S., Campbell I. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium antibodies in 10 animal species. J Clin Microbiol. 1981 Oct;14(4):455–456. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.4.455-456.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzipori S., Smith M., Halpin C., Angus K. W., Sherwood D., Campbell I. Experimental cryptosporidiosis in calves: clinical manifestations and pathological findings. Vet Rec. 1983 Feb 5;112(6):116–120. doi: 10.1136/vr.112.6.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar B. L., Burris J. A., Quinn C. A., Finkelman F. D. New mouse models for chronic Cryptosporidium infection in immunodeficient hosts. Infect Immun. 1990 Apr;58(4):961–969. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.961-969.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar B. L. Enzyme-linked immunoassay for detection of Cryptosporidium antigens in fecal specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990 Nov;28(11):2491–2495. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2491-2495.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar B. L., Gilman R. H., Lanata C. F., Perez-Schael I. Seroepidemiology of Cryptosporidium infection in two Latin American populations. J Infect Dis. 1988 Mar;157(3):551–556. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar B. L., Nash T. E. Quantification of specific antibody response to Cryptosporidium antigens by laser densitometry. Infect Immun. 1986 Jul;53(1):124–128. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.1.124-128.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villacorta I., Peeters J. E., Vanopdenbosch E., Ares-Mazás E., Theys H. Efficacy of halofuginone lactate against Cryptosporidium parvum in calves. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991 Feb;35(2):283–287. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.2.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmire W. M., Harp J. A. Characterization of bovine cellular and serum antibody responses during infection by Cryptosporidium parvum. Infect Immun. 1991 Mar;59(3):990–995. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.3.990-995.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]