Abstract

AlaXp is a widely distributed (from bacteria to humans) genome-encoded homolog of the editing domain of alanyl-tRNA synthetases. Editing repairs the confusion of serine and glycine for alanine through clearance of mischarged (with Ser or Gly) tRNAAla. Because genome-encoded fragments of editing domains of other synthetases are scarce, the AlaXp redundancy of the editing domain of alanyl-tRNA synthetase is thought to reflect an unusual sensitivity of cells to mistranslation at codons for Ala. Indeed, a small defect in the editing activity of alanyl-tRNA synthetase is causally linked to neurodegeneration in the mouse. Although limited earlier studies demonstrated that AlaXp deacylated mischarged tRNAAla in vitro, the significance of this activity in vivo has not been clear. Here we describe a bacterial system specifically designed to investigate activity of AlaXp in vivo. Serine toxicity, experienced by a strain harboring an editing-defective alanyl-tRNA synthetase, was rescued by an AlaXp-encoding transgene. Rescue was dependent on amino acid residues in AlaXp that are needed for its in vitro catalytic activity. Thus, the editing activity per se of AlaXp was essential for suppressing mistranslation. The results support the idea that the unique widespread distribution of AlaXp arises from the singular difficulties, for translation, poised by alanine.

The editing activities of tRNA synthetases provide a major safeguard against mistranslation, the insertion of the wrong amino acid at a specific codon (1–4). This insertion arises from small amounts of tRNA mischarging, a phenomenon that is intrinsic to the active sites of many of the synthetases. This mischarging results from the inherent inability of the enzyme binding pockets to discriminate rigorously between closely similar amino acid side chains, especially to achieve the level of discrimination needed for the high accuracy of the genetic code. Examples include the synthesis of Val-tRNAIle by isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (3, 5), Thr-tRNAVal by valyl-tRNA synthetase (6, 7), Val-tRNALeu by leucyl-tRNA synthetase (8–10), Ala-tRNAPro by prolyl-tRNA synthetase (11, 12), Ser-tRNAThr by threonyl-tRNA synthetase (13), Ile-tRNAPhe by phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase (4), and Ser- or Gly-tRNAAla by alanyl-tRNA synthetase (AlaRS)2 (14, 15). Normally, the mischarged tRNAs are cleared by a distinct editing activity, specific to each synthetase. This activity is able to distinguish the correct from the incorrect amino acid fused to its cognate tRNA. In addition to the editing activity that is part of the synthetase and encoded as a separate domain (16–18), there are a few instances of free-standing editing domain homologs encoded by various genomes (12, 19–22). The most widespread (through all three kingdoms of life) of these is AlaXp, a small protein that is a homolog of the editing domain of AlaRS and has been shown to edit Ser-tRNAAla and Gly-tRNAAla in vitro (21–24). Not clear, however, is whether AlaXp plays a role in vivo in guarding against mistranslation.

The importance of editing for the (conditional) survival of bacteria is well established (7, 25, 26). The connection of editing defects to disease in mammalian systems has also been demonstrated from investigations in vivo of the editing activities of valyl-tRNA synthetase (ValRS) and AlaRS. For example, in the case of ValRS, inducing the expression of a transgene encoding an editing-defective ValRS in mammalian cells creates a transdominant, pathological phenotype (27). In the mouse, a mild editing defect in AlaRS leads to neurodegeneration characterized by ataxia and disintegration of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum (28). The editing-defective murine AlaRS synthesizes small amounts of Ser-tRNAAla, and the tiny amount of incorporation of Ser at codons for Ala eventually triggers the unfolded protein response and cellular markers for apoptosis.

Thus, the need for editing to guard against mistranslation is now recognized, but the contribution of components like AlaXp remains unanswered because activity in vivo has never been demonstrated. Because Escherichia coli is an exception to the usual case where AlaXp is present, it offers an opportunity to investigate an AlaXp in vivo in circumstances where the bacterium has an editing-defective AlaRS. Previous work showed that serine was toxic to E. coli when it harbored an editing-defective AlaRS (14), thus giving an example, in bacteria, of the significance of mistranslation at codons for alanine. Given these circumstances, the question we posed was whether a transgene encoding an AlaXp could rescue an editing-defective strain of E. coli and, if so, whether that rescue depended on determinants in AlaXp that were essential for its editing function.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of tRNA—E. coli tRNAAla(UGC) was prepared in vitro as described previously (14), except the transcription was done using a MEGAshortscript kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Misacylated [3H]Ser-tRNAAla was produced in vitro using E. coli AlaRS C666A/Q584H as described previously (14).

Protein Expression and Purification—E. coli AlaRS and Methanosarcina mazei AlaXp proteins used in activity assays were prepared by expression from plasmid pET21b (Novagen, Madison, WI) as described previously (24).

Aminoacylation Assay—Aminoacylation was performed at room temperature in assay buffer (50 mm HEPES (pH 7.5), 20 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 2 mm dithiothreitol) with ATP (4 mm) and tRNAAla transcript (5 μm). Alanine charging was done in the presence of wild-type or mutant AlaRS (50 nm) and [3H]Ala (100 μm). Mischarging was done with wild-type or mutant AlaRS (5 μm) and [3H]Ser (100 μm). Aliquots were quenched and precipitated in 96-well Multiscreen filter plates (Millipore) as described previously (29). After washing and elution by NaOH, samples were counted in a MicroBeta plate reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

Deacylation Assay—[3H]Ser-tRNAAla (∼5 μm) was incubated at room temperature with AlaRS (50 nm) or AlaXp (10 nm) in assay buffer before being quenched into 96-well Multiscreen filter plates as described previously (29). Liberated [3H]Ser was collected by centrifugation into 96-well flexible plates, and radioactive counts were measured on a MicroBeta plate reader.

Strain Construction—Unless otherwise noted, cells were grown in M9 minimal media (30) with 0.4% glycerol, 0.002% l-arabinose, 0.01 mg/ml thiamine, and some or all of the following antibiotics: kanamycin (50 μg/ml), ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml). The pBAD18/21 and pBAD33/21 plasmids consist of an insertion of a pET21b XbaI/StyI fragment into pBAD18 (Ampr, pBR origin) and pBAD33 (Cmr, pACYC origin) (31), respectively. E. coli strain W3110 (lacIq recA Δ1 Kanr alaSΔ2 pMJ901[Tetr]) (32) was transformed with pBAD18/21-AlaRS(C666A/Q584H). The pMJ901 maintenance plasmid bears the alaS gene (encoding wild-type AlaRS) and a temperature-sensitive replicon, which fails to replicate at 42 °C. Transformants were selected on LB-Kan (25 μg/ml)/Amp (50 μg/ml)/Tet (50 μg/ml) at 30 °C. Colonies were grown on M9-Kan/Amp plates at 42 °C to clear the maintenance plasmid, leaving growth dependent on the editing-defective AlaRS. The resulting editing-defective AlaRS strain was made chemically competent by the rubidium chloride method and then transformed with pBAD33/21, pBAD33/21-AlaXp, or pBAD33/21-AlaXp(K251A/K253A).

Halo Assay—Media for the halo assay was made with 15 g/liter agar, and each plate contained 25 ml. 10 μl of an overnight culture was diluted into 1 ml of sterile water and spread on a M9-Kan/Amp/Cm plate. 100 μl of 1 m l-serine was added to a well cut into the center of the plate and allowed to diffuse into the agar, creating a radial gradient. Plates were incubated at 37 °C and imaged after 48 h.

Direct Growth Assay—To confirm the serine sensitivity of AlaRS C666A/Q584H, M9-Kan/Amp plates were poured with 0 or 5 mm l-serine. 10 μl of an overnight culture was streaked on the plates and incubated at 37 °C for 40 h. For testing AlaXp, M9-Kan/Amp/Cm plates were poured with 0, 5, 7.5, or 10 mm l-serine. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100, and 5 μl was streaked on the plate. Plates were incubated at 37 °C and imaged after 72 and 96 h.

Immunoblotting—The primary antibody used was α-His (HIS.H8) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:10000 dilution.

Nitrocellulose Filter Binding Assay—In vitro transcribed tRNAAla was end-labeled with 32P using a KinaseMax kit (Ambion). The filter binding assays were carried out as described previously (33). Briefly, [32P]tRNAAla (20 nm) was incubated with AlaXp (0–3.75 μm) in 60 mm KH2PO4 (pH 5), 10 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin for 10 min at 25 °C. Reactions were spotted onto nitrocellulose filters (Millipore) soaked in 5% trichloroacetic acid and washed over a vacuum with assay buffer. Filters were dried, and captured [32P]tRNAAla was measured by scintillation counting.

RESULTS

Overall Experimental Strategy—The challenge was to find a way to test in vivo for the activity of AlaXp in isolation from any contribution of editing activity from endogenous AlaRS. For this purpose, we needed a strain of bacteria that harbored an AlaRS with completely ablated editing activity. Because the sites for aminoacylation and editing are discrete, the activity for editing can in principle be abolished without disrupting the essential aminoacylation function. To abolish the editing function, two mutations were placed in the editing domain of AlaRS. The purpose of this mutant was to have total elimination of the editing function while maintaining aminoacylation function. The double mutant was introduced into a bacterial strain carrying a deletion of the endogenous AlaRS gene. With the endogenous editing activity from AlaRS completely abolished, we then set out to test AlaXp function by introducing an AlaXp-encoding transgene into the editing-defective strain.

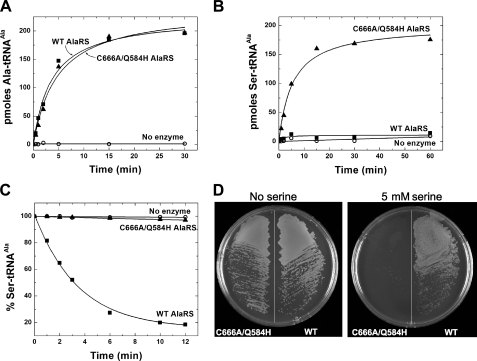

Construction and Testing Editing-defective C666A/Q584H AlaRS—Cys-666 in the editing domain is conserved through evolution for all AlaRSs. It is important for editing, because substitution of Cys-666 with Ala severely diminishes the ability of AlaRS to edit mischarged Ser-tRNAAla or Gly-tRNAAla (14). As a consequence, C666A AlaRS misacylates tRNAAla with Ser or Gly. (In work reported below, we focused on Ser-tRNAAla to study editing activities of mutant and wild-type proteins.) Separately, the Q584H mutation was serendipitously discovered to further enhance mischarging by C666A AlaRS in vitro (14). To further investigate the properties of C666A/Q584H AlaRS, we first established that its aminoacylation activity with alanine was unchanged from that of wild-type AlaRS (Fig. 1A). However, in contrast to the wild-type enzyme, C666A/Q584H AlaRS mischarged Ser onto tRNAAla (Fig. 1B). Consistent with this mischarging, deacylation of Ser-tRNAAla by C666A/Q584H AlaRS was undetectable (at the level of background) (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Editing defect of C666A/Q584H AlaRS. A, aminoacylation of tRNAAla by wild-type (▪) and C666A/Q584H (▴) AlaRS (50 nm). B, misacylation of tRNAAla with serine by wild-type and C666A/Q584H AlaRS (5 μm). C, deacylation of [3H]Ser-tRNAAla by wild-type and C666A/Q584H AlaRS (50 nm). D, ΔalaS strain complemented by wild-type or editing-defective C666A/Q584H AlaRS. Cells were streaked onto minimal media containing no amino acid or 5 mm serine and incubated at 37 °C for 40 h.

Next, we tested the ability of C666A/Q584H AlaRS to sustain cell growth. For this purpose, we used E. coli strain W3110 (lacIq recA Δ1 Kanr alaSΔ2) that harbors a chromosomal deletion of alaS (32). This ΔalaS strain is maintained by a plasmid bearing wild-type alaS and a temperature-sensitive replicon. The maintenance plasmid is lost at 42 °C, and growth can then be sustained only by introduction of a second plasmid that expresses a functional AlaRS and is not lost at the higher temperature. Thus, the question was whether a plasmid encoding C666A/Q584H AlaRS (under the control of the arabinose operon pBAD promoter) could rescue growth of the null strain after ejection of the maintenance plasmid.

We found that W3110 (lacIq recA Δ1 Kanr alaSΔ2) harboring the gene for editing-defective C666A/Q584H AlaRS was able to grow on minimal media containing no additional amino acids but failed to grow on plates containing 5 mm serine (Fig. 1D). By contrast, a strain containing a plasmid encoding wild-type AlaRS, under the control of the same promoter, was able to grow on plates containing serine. This sensitivity of C666A/Q584H AlaRS to high concentrations of serine is consistent with its inability to edit mischarged Ser-tRNAAla and to prevent misincorporation of serine at codons for alanine.

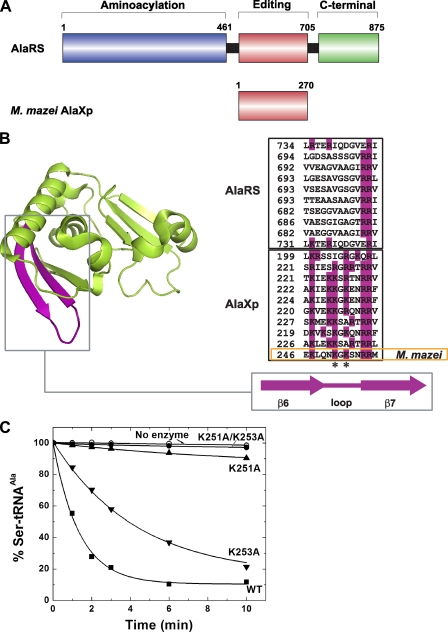

In Vitro Editing Activity of M. mazei AlaXp and Its Dependence on Two Conserved Lysines—M. mazei AlaXp is a 270-amino acid polypeptide that is homologous to the editing domain of AlaRS (Fig. 2A). Like AlaXps from other sources (21, 23), M. mazei AlaXp edits tRNAAla mischarged with Ser or Gly in vitro (24).3 We selected M. mazei AlaXp (a “type I” AlaXp) because it is small and, from earlier work, was shown to be soluble when expressed in E. coli (24). In eukaryotes, including mammals, AlaXp is extended by inclusion of the C-terminal domain of AlaRS (to give a “type II” AlaXp) that contributes nonspecific RNA binding elements (24). For the shorter AlaXps, such as the one from M. mazei, the sequence divergence (between AlaXp and the core editing domain of AlaRS) in a loop between two β strands (β6 and β7 in Fig. 2B) is thought to compensate for the determinants in the C-terminal domain of AlaRS that are missing in the type I AlaXps.

FIGURE 2.

Features of AlaRS and AlaXp. A, domain structure of AlaRS and M. mazei AlaXp. AlaRS residues are numbered according to the E. coli sequence. B, structure of P. horikoshii AlaXp with the basic strand-loopstrand highlighted in purple. A representative alignment of this region from AlaRSs and type I AlaXps is on the right. Sequences are, from top to bottom: P. horikoshii, Roseovarius nubinhibens, Ralstonia metallidurans, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Sinorhizobium medicae, Oceanicola granulosus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Bacillus cereus, Burkholderia pseudomallei, M. mazei AlaRS and then the same species in the same order for AlaXp. Lys-251 and Lys-253 in M. mazei AlaXp are marked with asterisks. C, deacylation of [3H]Ser-tRNAAla by wild-type and mutant forms of M. mazei AlaXp (10 nm).

Key among those in the abovementioned loop is Lys-251 and Lys-253 (Fig. 2B). The double mutant K251A/K253A M. mazei AlaXp was shown previously to be inactive for editing in vitro (24). Our interest in this mutant was based on the idea that, if AlaXp was shown to be active in vivo by rescue of an editing-defective host strain, then finding that expression of an inactive (in vitro) mutant version of AlaXp did not rescue growth (of the editing-defective strain) would confirm that it was the editing activity per se of AlaXp that was needed for cell survival.

Pursuant to this line of investigation, we wanted to learn more about the basis for the lack of activity of K251A/K253A M. mazei AlaXp. From molecular modeling based on the structures of Pyrococcus horikoshii AlaXp and the threonyl-tRNA synthetase–tRNAThr co-crystal (the editing domains of ThrRS and AlaRS are homologous) (22), these lysines (Lys-251 and Lys-253) within the basic loop come into close contact with the acceptor stem of tRNAAla. Individual K251A and K253A mutant AlaXps were constructed, and each single mutant, the double mutant, and the wild-type protein was tested for activity toward Ser-tRNAAla (Fig. 2C). The K253A AlaXp had a modest decrease in editing activity, whereas K251A AlaXp had a more severe editing defect. Importantly, K251A/K253A AlaXp had an even further reduction in editing activity, to nearly background levels. Thus, most of the previously observed defect in K251A/K253A AlaXp is due to the mutation of Lys-251. Consistent with this finding, of the two lysines, Lys-251 is the most conserved (Fig. 2B).

We postulated that the basic loop of M. mazei AlaXp contributed to tRNA binding affinity. However, when wild-type and mutant AlaXps were assayed for tRNAAla binding by the nitrocellulose filter binding method, the dissociation constants were similar for all the AlaXp proteins. The Kd values were 77 nm (wild-type), 71 nm (K253A), 48 nm (K251A), and 45 nm (K251A/K253A). Because the filter binding assays were done at pH 5.0, we wondered whether the lack of difference in the Kd values was a consequence of the low pH. For that reason, we did a kinetic analysis at pH 7.5 to determine relative values of Km for the wild-type and mutant proteins. The relative Km values were 1 (wild-type), 5.4 (K253A), 11.0 (K251A), and 11.4 (K251A/K253A). Thus, under these conditions, the wild-type protein associates (as defined by Km) 5–10-fold more strongly. Still, most of the difference (over 500-fold) in catalytic activity (kcat/Km) of the wild-type versus the K251A/K253A mutant protein is in the kcat parameter. Thus, we conclude that the basic loop containing Lys-251 and Lys-253 may have an interaction with tRNAAla that includes a component affecting kcat, such as anchoring the acceptor stem to facilitate positioning of the CCA-3′ end in the catalytic site for editing.

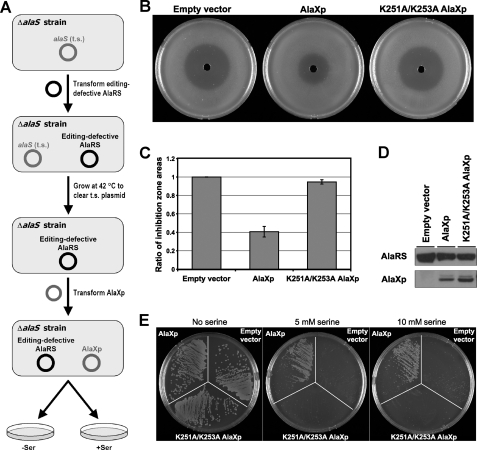

M. mazei AlaXp Rescues Serine Toxicity of Editing-defective Strain—To investigate the biological function of AlaXp in vivo, we transformed a plasmid carrying M. mazei AlaXp into the editing-defective C666A/Q584H AlaRS-bearing strain. The flow of these experiments is shown in Fig. 3A. First, the editing-defective strain was established by introducing a maintenance plasmid encoding C666A/Q584H AlaRS into a ΔalaS strain. Next the plasmid encoding M. mazei AlaXp was introduced. Both plasmids were under the control of pBAD arabinose-inducible promoters (31), with distinct markers and origins of replication to allow for co-transformation.

FIGURE 3.

Rescue of serine sensitivity in editing-defective AlaRS strain by AlaXp. A, experimental overview for rescue of AlaRS editing defect. The ΔalaS strain was transformed with a plasmid carrying editing-defective AlaRS, grown at 42 °C to clear the temperature-sensitive maintenance plasmid, then transformed with a second plasmid carrying empty vector, M. mazei wild-type AlaXp, or K251A/K253A AlaXp. B, growth of editing-defective E. coli C666A/Q584H AlaRS strain containing empty vector, wild-type AlaXp, or K251A/K253A AlaXp, in the presence of a radial gradient of serine on minimal media. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. C, relative areas of growth inhibition in the presence of a radial gradient of serine. The bars represent two independent experiments. D, expression of C666A/Q584H AlaRS and AlaXps in E. coli. Cultures were inoculated from the halo assay plates, and cell lysates were probed for expression using an α-His tag antibody. E, editing-defective AlaRS strain containing empty vector, wild-type AlaXp, or K251A/K253A AlaXp was streaked onto minimal media containing no amino acid or varying amounts of serine. The no serine and 5 mm serine plates were imaged after incubation at 37 °C for 72 h. The 10 mm serine plate was imaged after 96 h of incubation.

To determine whether AlaXp expressed from the transgene was able to rescue the serine toxicity experienced by the editing-defective AlaRS strain, cells were subjected to high concentrations of serine. For this purpose, a radial gradient was generated by diffusion of serine from a central well cut into the agar media. Sensitivity to serine was seen as a “halo” of cell toxicity around the central well. The zone of growth inhibition in the strain containing wild-type AlaXp was markedly smaller in size compared with that of a strain carrying the empty vector (Fig. 3B). The reduction in halo size (Fig. 3C) showed that the presence of AlaXp allows editing-defective AlaRS to sustain growth at much higher concentrations of serine.

To confirm that the editing activity per se of AlaXp is responsible for this phenomenon, another strain was created with the K251A/K253A AlaXp double mutant that, as noted previously, is defective in its editing activity in vitro (Fig. 2C). Growth of this strain in the presence of the radial serine gradient was only marginally better than that of the empty vector control (Fig. 3, B and C). No toxicity was observed in any of the strains when water or alanine was added to the central well in place of serine. Thus, the editing activity of AlaXp is able to rescue serine toxicity in the editing-defective AlaRS strain by preventing mistranslation at alanine positions.

To determine whether results seen in the halo assays were due to disparate levels of one or more of the proteins (C666A/Q584H AlaRS, AlaXp, K251A/K253A AlaXp) expressed from the introduced plasmids, cultures were inoculated from the plates at the conclusion of the halo assays. Cell lysates were separated on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with an α-His tag antibody. (The introduced plasmids encoding C666A/Q584H AlaRS and the AlaXps also encode a C-terminal His tag for each.) Expression of C666A/Q584H AlaRS was similar for all three strains (with slightly stronger expression in the strain bearing an empty vector in place of the plasmid encoding one of the AlaXps) (Fig. 3D). This result shows that rescue by AlaXp of the growth defect of the strain harboring C666A/Q584H AlaRS was not due to higher levels of C666A/Q584H AlaRS expression that, in turn, could have conferred a higher aminoacylation activity and faster growth rate. In addition, expression of wild-type and K251A/K253A AlaXps were comparable, with slightly stronger expression of the mutant AlaXp (Fig. 3D). Thus, the rescue seen with wild-type AlaXp was due to its catalytic activity rather than to a difference in expression levels.

To further confirm the ability of AlaXp to rescue the serine toxicity of the editing-defective strain, plates with various amounts of serine were prepared, and instead of a halo assay, colony growth was observed directly. The C666A/Q584H AlaRS strain, which failed to grow in the presence of 5 mm serine (Fig. 1D), was able to grow when transformed with wild-type AlaXp (Fig. 3E). Growth of the strain encoding wild-type AlaXp was also observed at 7.5 and 10 mm serine (although the growth rate was diminished at these higher concentrations). In contrast, strains carrying either the empty vector or K251A/K253A AlaXp failed to grow at the same serine concentrations (Fig. 3E). The data in Fig. 3 strongly support the conclusion that the free-standing editing domain homolog, AlaXp, is functional for clearance of mischarged tRNAAla in vivo.

DISCUSSION

The genetic complementation assay here was able to provide a clear demonstration of the activity in vivo of AlaXp. When challenged with serine, cells harboring an editing-defective AlaRS could only survive by expression of AlaXp in trans. The results demonstrate the significance of “post-transfer” editing; that is, clearance of mischarged tRNA after the aminoacyl group has been transferred from the adenylate (as aminoacyl-AMP) to the 3′-end of the tRNA. (In pre-transfer editing, the adenylate is hydrolyzed before the amino acid is transferred to the tRNA.) Interestingly, AlaXp was able to capture and hydrolyze Ser-tRNAAla before the mischarged tRNA was bound and protected by EF-Tu and carried to the ribosome. It is possible that AlaXp weakly associates with AlaRS to improve the efficiency of clearance. On that point, the Ybak protein binds to ProRS to clear Cys-tRNAPro (19).

It is also of interest to note that M. mazei AlaXp deacylates E. coli Ser-tRNAAla in vivo, just as it does in vitro (24). This cross-species ability to recognize tRNAAla in vivo is most likely because the domain for editing, like that for aminoacylation (34), recognizes the G3:U70 base pair that is common to almost all tRNAAla sequences (24).

An unanswered question from earlier work was the rationale for the need for genome-encoded, free-standing homologs of editing domains. The work here provides a direct demonstration that, indeed, one example of these free-standing domains can provide the editing function in a way that ensures cell survival. That survival is dependent on AlaXp, in this particular experimental system, places further emphasis on the sensitivity of cells to mistranslation. In particular, the results stimulate further interest in the question of why a small, 2-fold defect in the editing activity of murine AlaRS should be sufficient to cause neurodegeneration in the sti mouse (28). In addition to neurodegeneration, these mice have other pathologies, such as substantially reduced body mass and altered fur. These pathologies are present even though the sti mouse encodes wild-type AlaXp. Thus, mistranslation appears to be near a “tipping point” presented by the singular difficulties of discriminating, in this instance, glycine and serine from alanine.

We can also raise the question of why AlaXp is the most widespread of these genome-encoded editing domains. No examples are known of separate, genome-encoded CP1 editing domains of IleRS, LeuRS, or ValRS, and only a limited evolutionary distribution of the ThrXp domain (that is closely related to AlaXp) is seen (20, 21). ProXp (and the related Ybak) is also widely distributed and has been shown to clear Ala-tRNAPro (12, 21). Thus, the precise insertion of alanine into proteins (not confusing Gly or Ser for Ala, and not confusing Ala for Pro) seems to present a major problem for many species through evolution. The “alanine problem” may be more difficult to overcome than other examples of amino acid misrecognition, such as the confusion of valine for isoleucine, threonine for valine, or serine for threonine. Whether the singular effects associated with mistranslation of alanine codons is due to the greater impact on protein folding of serine (or glycine) substitutions for alanine, or alanine substitutions for proline, is not clear but remains a formal possibility.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 23562. This work was also supported by a fellowship from the National Foundation for Cancer Research. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: AlaRS, alanyl-tRNA synthetase; ValRS, valyl-tRNA synthetase; ThrRS, threonyl-tRNA synthetase.

Y. E. Chong, unpublished observation.

References

- 1.Jakubowski, H., and Goldman, E. (1992) Microbiol. Rev. 56 412-429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schreier, A. A., and Schimmel, P. R. (1972) Biochemistry 11 1582-1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eldred, E. W., and Schimmel, P. R. (1972) J. Biol. Chem. 247 2961-2964 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarus, M. (1972) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 69 1915-1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fersht, A. R. (1977) Biochemistry 16 1025-1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fersht, A. R., and Kaethner, M. M. (1976) Biochemistry 15 3342-3346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doring, V., Mootz, H. D., Nangle, L. A., Hendrickson, T. L., de Crecy-Lagard, V., Schimmel, P., and Marliere, P. (2001) Science 292 501-504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Englisch, S., Englisch, U., von der Haar, F., and Cramer, F. (1986) Nucleic Acids Res. 14 7529-7538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J. F., Guo, N. N., Li, T., Wang, E. D., and Wang, Y. L. (2000) Biochemistry 39 6726-6731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinis, S. A., and Fox, G. E. (1997) Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 36 125-128 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beuning, P. J., and Musier-Forsyth, K. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97 8916-8920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong, F. C., Beuning, P. J., Silvers, C., and Musier-Forsyth, K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 52857-52864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dock-Bregeon, A.-C., Sankaranarayanan, R., Romby, P., Caillet, J., Springer, M., Rees, B., Francklyn, C. S., Ehresmann, C., and Moras, D. (2000) Cell 103 877-884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beebe, K., Ribas de Pouplana, L., and Schimmel, P. (2003) EMBO J. 22 668-675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsui, W. C., and Fersht, A. R. (1981) Nucleic Acids Res. 9 4627-4637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schimmel, P., and Ribas de Pouplana, L. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25 207-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larkin, D. C., Williams, A. M., Martinis, S. A., and Fox, G. E. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30 2103-2113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jasin, M., Regan, L., and Schimmel, P. (1983) Nature 306 441-447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An, S., and Musier-Forsyth, K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 34465-34472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korencic, D., Ahel, I., Schelert, J., Sacher, M., Ruan, B., Stathopoulos, C., Blum, P., Ibba, M., and Soll, D. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 10260-10265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahel, I., Korencic, D., Ibba, M., and Soll, D. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 15422-15427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sokabe, M., Okada, A., Yao, M., Nakashima, T., and Tanaka, I. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 11669-11674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukunaga, R., and Yokoyama, S. (2007) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 63 390-400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beebe, K., Mock, M., Merriman, E., and Schimmel, P. (2008) Nature 451 90-93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bacher, J. M., de Crecy-Lagard, V., and Schimmel, P. R. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102 1697-1701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nangle, L. A., de Crecy-Lagard, V., Doring, V., and Schimmel, P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 45729-45733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nangle, L. A., Motta, C. M., and Schimmel, P. (2006) Chem. Biol. 13 1091-1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, J. W., Beebe, K., Nangle, L. A., Jang, J., Longo-Guess, C. M., Cook, S. A., Davisson, M. T., Sundberg, J. P., Schimmel, P., and Ackerman, S. L. (2006) Nature 443 50-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beebe, K., Waas, W., Druzina, Z., Guo, M., and Schimmel, P. (2007) Anal. Biochem. 368 111-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, J. H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics, p. 431, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- 31.Guzman, L. M., Belin, D., Carson, M. J., and Beckwith, J. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177 4121-4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jasin, M., and Schimmel, P. (1984) J. Bacteriol. 159 783-786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regan, L., Bowie, J., and Schimmel, P. (1987) Science 235 1651-1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hou, Y. M., and Schimmel, P. (1988) Nature 333 140-145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]