Abstract

Salmonella enterica is a facultative intracellular pathogen that is able to modify host cell functions by means of effector proteins translocated by the type III secretion system (T3SS) encoded by Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 2 (SPI2). The SPI2-T3SS is also active in Salmonella after uptake by murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BM-DC). We have previously shown that intracellular Salmonella interfere with the ability of BM-DC to stimulate antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation in an SPI2-T3SS-dependent manner. We observed that Salmonella-mediated inhibition of antigen presentation could be restored by external addition of peptides on major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II). The processing of antigens in Salmonella-infected cells was not altered; however, the intracellular loading of peptides on MHC-II was reduced as a function of the SPI2-T3SS. We set out to identify the effector proteins of the SPI2-T3SS involved in inhibition of antigen presentation and demonstrated that effector proteins SifA, SspH2, SlrP, PipB2, and SopD2 were equally important for the interference with antigen presentation, whereas SseF and SseG contributed to a lesser extent to this phenotype. These observations indicate the presence of a host cell-specific virulence function of a novel subset of SPI2-effector proteins.

Salmonella enterica is frequent food-borne pathogen that causes a range of diseases ranging from mild and usually self-limiting gastroenteritis to a life-threatening systemic infection known as typhoid fever. The pathogenesis of typhoid fever is characterized by the uptake of Salmonella enterica with contaminated food or water, the penetration of the intestinal epithelium and systemic spread ultimately resulting in the massive replication of Salmonella in various organs. S. enterica is an invasive, facultative intracellular pathogen, and it is considered that the ability to survive and replicate inside eukaryotic host cells has a central role in the systemic pathogenesis. Infection of Slc11a1−/− (formerly Nramp−/−) mouse strains with S. enterica serovar Typhimurium is considered as a model system for human typhoid fever caused by S. enterica serovar Typhi.

Dendritic cells (DC) are phagocytic cells that form an important link between innate and adaptive immunity (reviewed in reference 24). DC sample antigens in peripheral tissues, transport the antigens to local lymph nodes, and act as antigen-presenting cells (APC) for the activation of T cells. Some of these features make DC attractive as target cells for pathogens, for example, to act as “Trojan horses” for the spread of the pathogen from the initial side of entry (40, 46).

We have recently characterized the intracellular fate of serovar Typhimurium in murine bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells (BM-DC) (17). We and others found that serovar Typhimurium forms a static nonreplication population in BM-DC and that virulence factors known for intracellular pathogenesis in other phagocytic cells have no contribution to the intracellular survival in BM-DC (17, 27). One of the multiple virulence determinants important for the intracellular phenotype of serovar Typhimurium is a type III secretion system (T3SS) encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI2) (reviewed in reference 22). T3SSs are complex molecular machines that mediate the translocation of a set of effector proteins into the eukaryotic host cell (reviewed in references 9 and 11). These effector proteins act as “injected toxins” and modify normal host cell functions in multiple ways for the benefit of the pathogen. The SPI2-T3SS is activated by intracellular Salmonella residing in a parasitophorous vacuole referred to as the “Salmonella-containing vacuole” (SCV). Previous work also indicated that intracellular S. enterica modifies host cell transport by means of the SPI2-T3SS, resulting in reduced vesicular traffic (38), protection of intracellular S. enterica against reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (6, 41), or redirection of exocytic transport (21). At present, 18 different effector proteins are known that are translocated by the SPI2-T3SS (13). Multiple cellular phenotypes have been associated with the function of the SPI2-T3SS, but a correlation between the phenotypes and the function of individual effector proteins has only been possible in a few cases (13, 22).

We previously observed that the SPI2-T3SS function of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium in BM-DC affects the ability of BM-DC to present antigens and the antigen-dependent stimulation of the T-cell proliferation (7). These studies were performed with model antigens that were internalized by BM-DC, together with the bacterial inoculum. Additional vaccination and challenge experiments indicated that the SPI2-T3SS function in vivo is important for the suppression of the development of an adaptive immune response against Salmonella. The role of SPI2 in inhibition of antigen presentation by DC was recently corroborated and extended by work of Tobar et al. (35).

The mechanism of antigen-processing in APC such as DC has been studied in great detail. It has been observed that peptides derived from phagocytosed antigens are loaded onto nascent major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules in a specialized compartment termed the MHC-II compartment (reviewed in reference 36). However, the precise nature of the compartments involved in delivery of peptides to the MHC-II molecules is not understood. The molecular mechanisms by which intracellular Salmonella inhibits antigen presentation in an SPI2-T3SS-dependent manner, however, have not been revealed yet. In the present study we set out to determine the molecular mechanisms of the interference of Salmonella with antigen processing and presentation and to define the effector proteins involved in this phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

For infection experiments, serovar Typhimurium NCTC 12023 was used as a wild-type (WT) strain, and various isogenic mutant strains were constructed in this strain background. One-step inactivation by the Red recombination approach was used for the deletion of target genes essentially as described previously (6) (oligonucleotide sequences are available from the authors). Strain designations and characteristics are listed in Table 1. Bacterial strains were routinely cultured to stationary phase (16 h of culture) in LB broth with aeration. Stationary-phase Salmonella was used to avoid host cell death induced by invasive bacteria. For the generation of plasmids for the complementation of mutations in individual effector genes, low-copy-number plasmids were constructed harboring effector genes under the control of their own promoter. The plasmids used in the present study are also listed in Table 1, and effector proteins expressed by plasmid-borne genes carried a C-terminal epitope tag, hemagglutinin (HA) or M45, for detection by immunofluorescence. If required for the selection of strains and in order to maintain plasmids, kanamycin or carbenicillin was added to a concentration of 50 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| NCTC 12023 | Wild type | Lab collection |

| HH104 | ΔsseC::aphT | 16 |

| HH107 | ΔsseF::aphT | 16 |

| HH108 | ΔsseG::aphT | 16 |

| MvP373 | ΔsscB sseFG::aph | 23 |

| MvP376 | ΔsspH2::aph | 6 |

| MvP389 | ΔsifB | 6 |

| MvP390 | ΔsspH1 | 6 |

| MvP392 | ΔsseJ | 6 |

| MvP393 | ΔsseI | 6 |

| MvP394 | ΔslrP | 6 |

| MvP498 | ΔpipB2::aph | This study |

| MvP505 | ΔsopD2::aph | This study |

| MvP509 | ΔsifA::aph | This study |

| MvP570 | ΔsseK1::aph | This study |

| MvP571 | ΔsseK2::aph | This study |

| MvP873 | ΔgogB | This study |

| MvP874 | ΔpipB | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pFPV25.1 | Constitutive GFP expression | 39 |

| pWSK29 | Low-copy-number vector | 44 |

| p2096 | PsseA sscB sseFG::M45 in pWSK29 | 12 |

| p2104 | PsifA sifA::M45 in pWSK29 | 12 |

| p2129 | PsseJ sseJ::M45 in pWSK29 | 12 |

| p2620 | PpipB pipB::M45 in pWSK29 | 20 |

| p2621 | PpipB2 pipB2::M45 in pWSK29 | 20 |

| p2643 | PsseA sscB sseF::HA in pWSK29 | 23 |

| p2644 | PsseA sscB sseFG::HA in pWSK29 | 23 |

| p2777 | PsseJ sseJ::HA in pWSK29 | 17 |

| p2797 | PsseI sseI::HA in pWSK29 | This study |

| p2798 | PslrP slrP::HA in pWSK29 | This study |

| p2800 | PsspH2 sspH2::HA in pWSK29 | This study |

| p2820 | PsspH1 sspH1::HA in pWSK29 | This study |

| p3172 | PsopD2 sopD2::HA in pWSK29 | This study |

Preparation and culture of DC and T cells.

DC were prepared from the bone marrow of 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice for proliferation assays (Charles Rivers Breeders) as previously described (7). For the T-cell proliferation assay the CD11c+-cell population was enriched by using MACS (Miltenyi Biotec), and a purity of ca. 95% was routinely obtained. The cells were allowed to adhere to cell culture plates for at least 6 h before infection.

Cells expressing OVA-specific T-cell receptor were prepared from cell suspensions of spleens of sex- and age-matched DO11.10 mice (JAX) by magnetic sorting (MACS) of CD4+ cells (Miltenyi Biotec). The antibodies used in the study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Antibodies used in this study

| Antibodya | Source or referenceb | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| Armenian hamster anti-mouse CD11c IgG1 | BD Bioscience | 1:500 |

| Goat anti-Armenian hamster Cy5 IgG | Dianova | 1:500 |

| Rat anti-mouse CD16/32 (Fc block) | BD Bioscience | 1:100 |

| FITC-conjugated rat-mouse (isotype control) | BD Bioscience | 1:500 |

| FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse I-A/I-E | BD Bioscience | 1:500 |

| R-PE-conjugated hamster anti-mouse CD11c | BD Bioscience | 1:500 |

| Biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse I-Ad/I-Ed | BD Bioscience | 1:25,000 |

| Mouse anti-M45 | 28 | 1:500 |

| Rat anti-hemagglutinin | Roche | 1:500 |

| Rat anti-mouse LAMP1 | DSHB | 1:500 |

| Rabbit anti-human Giantin | BD Bioscience | 1:500 |

| Mouse anti-chicken γ-tubulin | Sigma | 1:1,000 |

| Rabbit anti-p38 (MAPK 14) | CST | 1:500 |

| Rat anti-murine CD4 | BD Bioscience | 1:500 |

IgG1, immunoglobulin G1; PE, phycoerythrin; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

DSBH, The Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA; CST, Cell Signalling Technology, Frankfurt, Germany.

Bacterial infection of DC.

Bacteria were added to BM-DC at various multiplicities of infection (MOI) as indicated at the respective experiment and centrifuged onto DC for 5 min at 500 × g to synchronize the infection. Noninternalized bacteria were removed by two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To kill remaining extracellular bacteria, infected cells were incubated for 1 h in medium containing 100 μg of gentamicin/ml. After a washing step, medium containing 25 μg of gentamicin/ml was added, and antibiotics were present throughout the experiment. The absence of extracellular bacteria was tested by plating supernatants onto LB agar plates. When infections were performed in low adherence plates (Costar), cells were recovered by centrifugation (1,300 × g for 5 min), and the medium or PBS was carefully removed.

Quantification of T-cell proliferation.

The generation of T cells from DO11.10 mice and the quantification of antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation was performed by determination of [3H]thymidine incorporation as described previously (7). Briefly, 105 sorted DC per well of 96-well plates were gamma-irradiated (3,600 rad) prior to infection and stimulation. Bacterial infections and stimulation with 50 μg of ovalbumin (OVA; Sigma)/ml were performed in parallel for 2 h. The antigen was removed and the gentamicin concentration was reduced. Splenic CD4+ T cells isolated from DO11.10 mice were added at a DC/T-cell ratio of 1:1 in a final volume of 200 μl of medium containing 25 μg of gentamicin/ml. After incubation for 2 days, cells were pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Amersham) in 50 μl of medium for additional 24 h before cell harvesting and quantification of the thymidine incorporation (Inotech). For the extracellular loading of MHC-II complexes, the peptide ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR corresponding to amino acids 323 to 339 of OVA was synthesized. Various concentrations of the peptide OVA were added 16 h postinfection to BM-DC, and incubation with the peptide was performed for 1 h. Unbound peptide was removed by washing, DC were incubated with T-cell from DO11.10 mice, and T-cell proliferation was quantified.

Immunofluorescence and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS).

For immunofluorescence, infection and stimulation of BM-DC was performed with cells seeded on glass coverslips 6 h prior to infection. At various time points after infection or stimulation with antigens, BM-DC were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. For immunostaining of γ-tubulin, cells were fixed for 10 min in methanol at −20°C and subsequently rehydrated in PBS. Antibodies were diluted in PBS containing 2% goat serum and 2% bovine serum albumin and, for intracellular staining, 0.1% saponin was added for permeabilization of cells. Coverslips were washed three times with PBS after each staining step (1 h) and mounted on Fluoprep (bioMèrieux) and sealed with Entellan (Merck). Epifluorescence of cells was analyzed with a Leica TCS-NT laser-scanning confocal microscope. Alternatively, the Zeiss Axiovert 200M wide-field microscope equipped with an Apotome was used. Stacked Z-sections or single Z-sections were displayed as indicated.

For flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur (BD), cells were grown in low-adherence plates (Costar), fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, and stained with antibodies, which were diluted in PBS containing 10% fetal calf serum and 1% bovine serum albumin.

SDS stability assay.

To analyze the stability of MHC-II molecules, DC were stimulated with 50 μg of OVA/ml, followed by incubation for 24 h after infection with bacteria or stimulation with 1 μg of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/ml. Infected DC were sorted by cytometry on a MoFlow, and the population positive for CD11c and green fluorescent protein (GFP) (expressed by serovar Typhimurium) was collected and processed for further analyses. DC stimulated only with OVA or LPS were sorted by MACS. Equal numbers of cells were lysed by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with monoclonal antibody against murine MHC-II (biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse I-Ad/I-Ed) and enhanced chemiluminescence detection using a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate.

Antigen processing assays.

To follow antigen processing, DC were stimulated with 50 μg of Texas Red-conjugated OVA (Molecular Probes)/ml and infected in parallel with bacteria. To analyze degradation of DQ OVA (Molecular Probes), this substrate was added after 16 h postinfection for 1 h in a concentration of 50 μg/ml. At several time points after the addition fluorescence was determined by using confocal microscopy or flow cytometry (FACSCalibur) as a correlate of proteolytic processing of antigen.

Statistical analyses.

Data analyses were performed using Prism 4.0 software. Statistical significance was calculated by using a two-tailed unpaired Student t test.

RESULTS

Degradation of model antigens in BM-DC is not affected by Salmonella.

We set out to identify the mechanisms of SPI2-dependent reduction of MHC-II-dependent T-cell stimulation by intracellular Salmonella in DC. One explanation for this phenotype might be an interference of Salmonella with antigen uptake and proteolytic degradation by BM-DC. Although mature DC have a reduced phagocytotic capacity, the cells retain their pinocytotic activity and are able to internalize and degrade soluble antigens. We tested whether the uptake and proteolytic degradation of a soluble antigen was affected by intracellular Salmonella through the action of SPI2. The degradation of two model antigens was analyzed.

BM-DC were stimulated with Texas Red-OVA and/or infected in parallel with Salmonella WT or an ΔsseC mutant that was used as a translocation-deficient SPI2 strain. The processing of the fluorescent model antigen during 24 h was monitored by observing the change in fluorescence intensity of individual cells by confocal microscopy (Fig. 1A). For quantitative analyses, mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) for the antigen were determined by flow cytometry. At 2 h after infection, BM-DC in all assays contained equal amounts of Texas Red-OVA. During the incubation period of 24 h, the MFI continuously decreased to ca. 35% of the initial level in uninfected BM-DC (Fig. 1B). BM-DC infected with WT or SPI2-deficient Salmonella showed the same reduction in fluorescence intensity.

FIG. 1.

Analysis of antigen-processing in Salmonella-infected BM-DC. BM-DC from C56BL/6 mice were infected at an MOI of 25 with Salmonella WT or a strain deficient in sseC, encoding a translocon subunit of the SPI2-T3SS (SPI2) for 1 h, were stimulated by addition of 1 μg of LPS/ml or remained uninfected (mock). In addition, BM-DC were stimulated with fluorescently labeled endocytotic marker Texas Red-OVA (A and B) or DQ-OVA (C and D). Texas Red-OVA fluorescence (red) decreases with increased proteolytic degradation, while fluorescence of DQ-OVA (green) is induced by proteolysis. At the indicated time points after infection, cells were fixed and subjected to immunofluorescence analyses after staining for CD11c (blue) and Salmonella (green in panel A, red in panel C). For quantification of antigen degradation, Salmonella-infected, LPS-stimulated or uninfected BM-DC were subjected to flow cytometry and gated on the CD11c-positive population. The MFI and standard deviation for Texas Red fluorescence were determined at various time points of infection (B), and the MFI for DQ-OVA was determined at 16 h after infection (D). The data are representative of three analyses with similar outcomes. *, P < 0.05; ns (not significant), P > 0.05. Scale bar, 10 μm.

As a further model antigen, DQ-OVA was used that is a self-quenched fluorochrome-conjugate of OVA that exhibits bright green fluorescence upon proteolytic degradation. This allowed the quantification of proteolysis by flow cytometry or confocal microscopy. Uninfected BM-DC or cells infected with Salmonella WT or the SPI2 mutant strain were incubated with DQ-OVA and washed to remove noninternalized tracer. After incubation for 16 h, the fluorescence of BM-DC was analyzed by epifluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1C) and flow cytometry (Fig. 1D). Both analyses indicated that the ability of BM-DC to internalize soluble antigens and the proteolytic degradation of the internalized material was not affected by infection with Salmonella. Furthermore, there was no difference in proteolytic degradation detectable between cells infected with Salmonella WT or the SPI2 strain.

Extracellular loading of an OVA peptide on DC complements the SPI2-mediated phenotype.

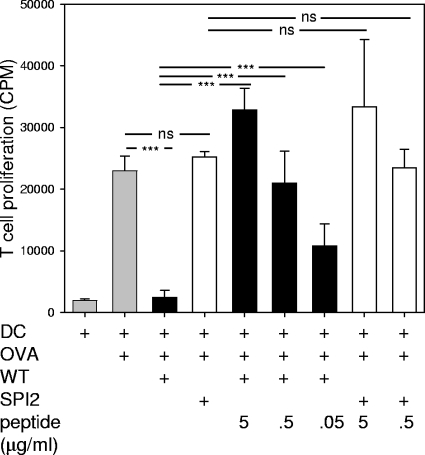

To characterize the effect of Salmonella on antigen processing in BM-DC in more details, we investigated whether antigen-dependent stimulation of T-cell proliferation could be restored by external loading with the cognate peptide. Small peptides are not processed by the default antigen-processing pathways for presentation on MHC-II complexes (reviewed in references 36 and 42). However, MHC-II complexes on the surface of DC can be loaded directly with suitable peptides, and these peptides may be presented to cognate T cells. We previously observed that in BM-DC the surface expression of MHC-II per se was not different after infection with Salmonella WT or a SPI2-deficient strain (7).

As a model system for antigen presentation and T-cell proliferation, we have previously established a model system of BM-DC that phagocytosed Salmonella along with the model antigen OVA. If OVA was processed and presented by the MHC-II complex, this stimulated the proliferation of T cells obtained from transgenic DO11.10 mice expressing the T-cell receptor that recognizes OVA peptide ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR in the context of MHC-II. In further assays, various amounts of OVA peptide ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR was added to uninfected BM-DC or to BM-DC infected with WT or SPI2-deficient Salmonella. The peptide was added 16 h after infection, and T-cell proliferation was quantified (Fig. 2). The addition of 0.5 μg of OVA peptide/ml to BM-DC infected with Salmonella WT restored antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation to the level obtained for uninfected cells. This effect was dependent on the concentration of the peptide. A higher concentration resulted in an increased rate of T-cell proliferation, indicating that a proportion of MHC-II complexes was available for uptake of externally added peptide.

FIG. 2.

Extracellular addition of OVA peptide restores antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation. Murine BM-DC (BALB/c) were mock infected (grey bars) or infected at an MOI of 25 with Salmonella WT (black bars) or a sseC-deficient strain (SPI2, open bars) as indicated. During infection for 2 h, OVA was added in a final concentration of 50 μg/ml. Noninternalized bacteria were killed by addition of gentamicin. In control experiments, BM-DC were not infected during stimulation with OVA or were neither infected nor stimulated. All assays were incubated for 16 h, and subsequently various amounts of the OVA peptide as indicated were added, followed by incubation for 1 h. After the unbound peptide was removed by washing, DO11.10 T cells were added, and antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation was assayed by measuring [3H]thymidine incorporation and quantification of the cell-bound radioactivity (in counts per minute [CPM]). The results shown are representative of three independent assays with similar results. The statistical significances were calculated between assays without or with the addition of various amounts of peptide. ***, P < 0.001; ns (not significant), P > 0.05.

These observations demonstrate that BM-DC infected with Salmonella WT are fully capable of antigen-dependent T-cell stimulation if a peptide can be presented on the cell surface. Despite the uptake and degradation of the antigen, intracellular Salmonella inhibit the processing and presentation of the antigen on BM-DC.

SPI2 function results in diminished peptide loading on MHC-II molecules.

We hypothesized that the interference with loading of proteolytically processed peptides onto MHC-II molecules prior to transport to the cell membrane of DC for presentation might be another possible form of interference leading to reduced antigen presentation. The formation of peptide-loaded MHC-II complexes can be assayed by determination of SDS stability (34). Peptide-loaded MHC-II molecules are usually stable as a αβ-peptide complex in the presence of SDS at room temperature and can be detected as a complex of ca. 60 kDa by Western blot analysis. In contrast, Ii and CLIP-associated MHC-II complexes, as well as nonloaded MHC-II molecules, disintegrate under these conditions into subunits that can be distinguished in Western blots. We determined the stability of MHC-II heterodimers toward SDS as a measure for peptide loading in uninfected BM-DC and cells infected with WT or SPI2 Salmonella (Fig. 3). Prior to cell lysis, the population of Salmonella-infected DC was isolated by FACS. In lysates of cells infected with the SPI2 strain, the 60-kDa band corresponding to the SDS-stable αβ-peptide complex was as intense as that in uninfected cells. In contrast, weaker band intensities were observed in lysates of Salmonella WT-infected cells. The band intensities were quantified by densitometry and compared to the band for p38, a constitutively expressed control protein.

FIG. 3.

Effect of Salmonella infection on the stability of MHC-II complexes. BM-DC from BALB/c mice were infected with GFP-expressing Salmonella WT or sseC-deficient (SPI2) strains as indicated at an MOI of 25. As controls, BM-DC were uninfected or were stimulated with LPS. If indicated, BM-DC were also stimulated with 50 μg of OVA/ml. To enrich Salmonella-infected BM-DC, 24 h after infection the cells were subjected to FACS for CD11c-positive and GFP-positive cells. BM-DC from the uninfected control assays were purified by MACS for CD11c-positive cells. About 6 × 105 cells were collected for each assay and subjected to the SDS stability assay as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Western blot analysis of SDS-stable MHC-II complexes (MHC-II) were performed with monoclonal antibody to mouse I-Ad/I-Ed. As loading controls, Western blots were stripped and reprobed with an antibody to p38. (B) For quantification, intensities for the MHC-II bands on Western blots were determined by densitometry and expressed as the percent transmission. Means and standard deviations of two blots are shown. The data shown are representative for three independent experiments with similar outcomes.

These data indicate that Salmonella interfere, in an SPI2-dependent manner, with the intracellular formation of peptide-loaded MHC-II complexes.

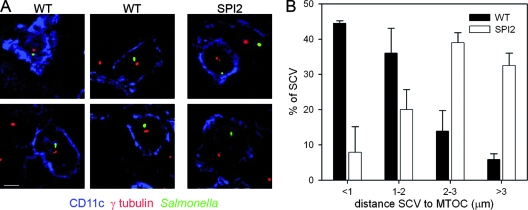

SPI2 function affects the subcellular localization of Salmonella within BM-DC.

Previous studies on the intracellular phenotype of serovar Typhimurium indicated that the SCV preferentially assumes a subcellular localization in juxtaposition of the Golgi apparatus and nucleus (1, 32). The role of the SPI2-T3SS and particular SPI2 effector proteins in this phenotype has been reported. We analyzed whether intracellular S. enterica can modify the positioning in the SCV within BM-DC. We observed that SCVs containing the WT strain were predominantly found in a subcellular localization adjacent to the trans-Golgi network (TGN) in BM-DC, while SCVs harboring the SPI2 strain were located at a larger distance to the TGN (data not shown). We found 65% of WT Salmonella and 39% of SPI2-deficient bacteria in close proximity of the TGN. Since the rather compact cell morphology of DC complicated the determination of the distance of the SCV to the TGN, we investigate the relative position of the SCV and the microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) as an organelle with a juxtanuclear position. BM-DC infected with WT or SPI2 strains were immunolabeled for γ-tubulin as a specific component of the MTOC, and the distance of various SCVs to the MTOC was determined (Fig. 4). In more than 85% of the infected DC, the distance between SCV containing WT Salmonella and the MTOC was <2 μm. In detail, ca. 45% of WT SCV were within a distance of 1 μm and ca. 40% of SCV were within a distance of 1 to 2 μm to the MTOC. However, in cells infected with the SPI2 strain, ca. 30% of SCV remained within 2 μm of the MTOC, with less than 9% in a range of 1 μm and ca. 20% in a range between 1 and 2 μm. The majority of SCVs containing the SPI2 mutant (ca. 70%) showed a distance of more than 2 μm to the MTOC. In detail, 40% of SCVs containing the SPI2 strain were found between 2 and 3 μm, and 30% were located at a distance of more 3 μm from the MTOC.

FIG. 4.

Intracellular localization of Salmonella in BM-DC is controlled by the function of the SPI2-T3SS. BM-DC from BALB/c mice were infected with Salmonella WT or an sseC-deficient strain (SPI2) at an MOI of 20. (A) Subcellular localization of intracellular Salmonella with respected to the MTOC. BM-DC were fixed 16 h after infection and processed for immunostaining of CD11c (blue), Salmonella (green), and γ-tubulin as a marker for the MTOC (red). Representative infected cells are shown. Note the distance between intracellular Salmonella and the MTOC. (B) Quantification of the distance between SCV and MTOC after infection of BM-DC with Salmonella WT and the SPI2 strain. At least 50 infected BM-DC are randomly selected, and the distance between MTOC and intracellular Salmonella was quantified by using Axiovision 4.5. Single Z sections of planes containing the SCV and the MTOC were used for these analyses. The mean and standard deviations of three independent experiments are shown.

The data indicate that intracellular Salmonella in DC can influence the positioning of the SCV in an SPI2-dependent manner. The phenotype is independent of the bacterial replication that is dependent on the SPI2 function in other cell types such as epithelial cells or macrophages (reviewed in reference 13).

Involvement of a subset of SPI2 effector proteins in interference with antigen presentation.

Our previous studies (7), as well as the data presented here, have shown that Salmonella deploy the SPI2-T3SS to interfere with antigen presentation by DC. The SPI2-T3SS translocates a complex cocktail of effector proteins, and the molecular functions have only been revealed for a small number of these proteins (reviewed in reference 13).

To test whether individual effectors or groups of the various SPI2-T3SS effectors are interfering with the antigen presentation by BM-DC, we generated isogenic strains harboring deletions of genes encoding individual effector proteins. This screen showed that mutant strains deficient in sifB, sspH1, sseJ, sseI, pipB, gogB, sseK1, and sseK2 did inhibit the antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation by infected BM-DC at a rate similar to that of the WT (Fig. 5A and B).

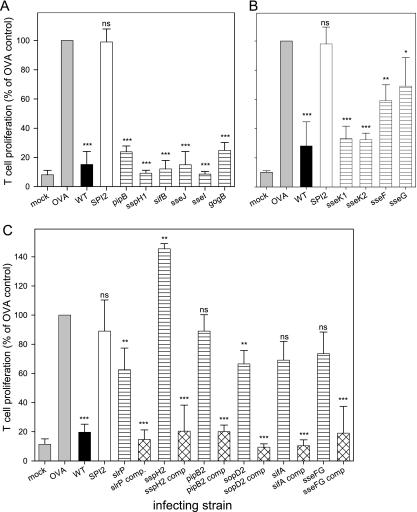

FIG. 5.

Role of SPI2 effector proteins in inhibition of T-cell proliferation by intracellular Salmonella. BM-DC from BALB/c mice were infected at an MOI of 20 with Salmonella WT (▪), a strain deficient in sseC (SPI2, □), or various mutant strains deficient in genes encoding effector proteins of the SPI2-T3SS as indicated (▤). BM-DC were stimulated with 50 μg of OVA/ml in parallel with infection. For controls, uninfected BM-DC with (OVA, ░⃞) or without (mock, ░⃞) stimulation by OVA were added to T cells. T-cell proliferation was assayed by measuring [3H]thymidine incorporation and quantification of cell-bound radioactivity and is expressed as the percentage and standard deviation of the T-cell proliferation stimulated by OVA-primed DC. (A to C) Data shown are separate analyses of groups of mutant strains defective in various effectors. (C) For mutant strains that showed defects in the inhibition of antigen-dependent stimulation of T-cell proliferation, complementation experiments with plasmid-borne effectors were performed (comp, ▩). The statistical significances between the OVA-stimulated, noninfected BM-DC and the various infected assays were calculated. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ns (not significant), P > 0.05.

A mutant strain deficient in spiC (alternative designation ssaB) showed a phenotype similar to that of the SPI2-T3SS-null mutant strain (data not shown). Since the role of SpiC/SsaB as a putative effector protein is controversial, we analyzed the intracellular characteristics of the spiC (ssaB) strain in BM-DC. As previously observed in other cell types, the spiC (ssaB) strain was incapable in translocation of the SPI2 effector proteins (data not shown). Other mutant strains defective in genes of effectors such as SseF or SifA remained capable of translocation of other SPI2 effector proteins. Therefore, SpiC/SsaB function in BM-DC cannot be distinguished from SPI2-T3SS-null mutant strains. For another subset of effector proteins, we observed strong effects on the capacity of BM-DC to stimulate antigen-specific T-cell stimulation. This subset of effectors consists of SifA, SseF, SseG, SspH2, SlrP, SopD2, and PipB2 (Fig. 5C). Strikingly, the level of T-cell proliferation for sifA, sspH2, slrP, sopD2, and pipB2 mutant strains defective in single effectors was comparable to that of the SPI2-T3SS-null mutant strain. This observation indicates that each of these effectors had an essential contribution to the SPI2 phenotype in DC. Strains with single mutations in sseF or sseG consistently showed an intermediate phenotype, while an sseFG mutant strain was highly reduced in inhibition of T-cell proliferation.

We also investigated the intracellular fate of the sifA strain. In contrast to a previous report (29), we did not observe that this mutant strain escapes into the cytoplasm of BM-DC with a higher frequency than does WT Salmonella. Analysis by electron microscopy showed that intracellular WT and sifA bacteria were within a membrane compartment in BM-DC (data not shown). Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that 82.5% ± 8.5% and 76.9% ± 0.14% of WT and sifA bacteria, respectively, colocalized with LAMP-1-positive membranes 16 h after infection.

To control the specificity of the mutations, complementation was performed with low-copy-number plasmids harboring effector genes expressed under the control of their natural promoter. The presence of a WT allele of the deleted effector gene restored the effect on T-cell proliferation, indicating the specificity of the observed phenotype (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the deletion of sspH2 resulted in rates of T-cell proliferation higher than those of BM-DC infected with the SPI2-null mutant. This effect was reproducible and could be restored by plasmid-borne sspH2.

Translocation of effector proteins by intracellular Salmonella into DC.

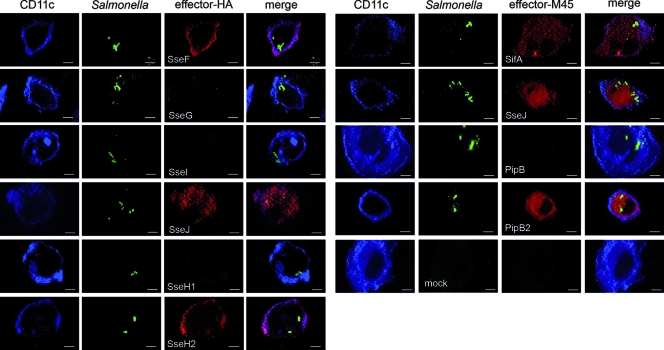

We next investigated whether the different contributions of effector proteins to the inhibition of antigen presentation by DC is a consequence of different efficiencies of translocation by intracellular Salmonella and followed the translocation of several SPI2 effector proteins. For a qualitative comparison of the amounts of translocated proteins, various effector proteins were labeled in a similar manner with epitope tags for detection with monoclonal antibody.

As previously described (17), the translocation of SseJ by intracellular Salmonella in DC was observed. Similarly, effector proteins SifA, SseF, SspH2, and PipB2 were detected in DC (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Translocation and subcellular localization of SPI2 effector proteins in BM-DC. BM-DC from C57BL/6 mice were infected at an MOI of 10 with Salmonella WT harboring plasmids for the expression of genes encoding various epitope-tagged effector protein. A mock-infected cell is shown as control. A subset of the effectors was tagged with the M45 epitope (SifA, PipB, PipB2, and SseJ); the other subset contained effectors fused to the hemagglutinin tag (SseF, SseG, SseI, SseJ, SspH1, and SspH2). At 16 h after infection, cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence of Salmonella LPS (green), the tag of the effector protein (red), and the CD11c (blue). Representative infected cells are shown for the specific effector proteins. Micrographs were acquired with a Zeiss Axiovert wide-field microscope equipped with an Apotome and show single Z-sections. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Interestingly, effectors SopD2 and SlrP were not detectable by immunofluorescence in infected DC (data not shown). However, as shown in Fig. 5, these effector proteins also contributed to the inhibition of antigen presentation. Further analyses in the epithelial cell line HeLa indicated that these proteins were translocated, yet detection by immunofluorescence was only possible if high numbers of intracellular Salmonella were present. In contrast, such high bacterial loads were not observed in DC under our experimental conditions. Based on these observations we conclude that the different contributions of SPI2 effector proteins is not due to the lack of translocation of one subset but rather to the interaction with specific host cell targets.

DISCUSSION

We have previously described the interference of intracellular Salmonella with antigen presentation by murine DC and the role of this process in a murine model of infection (7). In the present work, we focused on the molecular mechanisms of this interference. During our approaches to characterize the SPI2-mediated interference with antigen presentation in molecular detail, we found that the overall ability of infected BM-DC to degrade model antigens was not altered. Furthermore, we found that external loading of MHC-II complexes with the OVA peptide restored the SPI2-mediated inhibition of T-cell proliferation. These experiments demonstrate that the SPI2-T3SS function does not per se affect the transport and surface expression of MHC-II complexes in Salmonella-infected cells. Rather, MHC-II complexes are available for external loading with peptides. The assays further confirm our previous observation that Salmonella infection and intracellular activity of the SPI2-T3SS does not affect the expression of costimulatory molecules (7). This observation also argues against a SPI2-mediated defect in the formation of immunological synapses between Salmonella-infected BM-DC and T cells.

A phenotype linked to the function of the SPI2-T3SS is the modification of cellular transport and the biogenesis of the SCV as a parasitophorous vacuole with unique properties. Several recent studies indicate that Salmonella can actively manipulate the positioning of the SCV in infected epithelial cells (1, 30, 32). The SCVs containing Salmonella WT frequently assume a subcellular position in close proximity to the nucleus, Golgi apparatus, and the MTOC. We observed that a similar phenotype is evident in Salmonella-infected BM-DC. In a SPI2-T3SS-dependent manner, the majority of SCVs were located close to the MTOC of BM-DC. Thus, manipulation of SCV positioning and host cell transport by Salmonella is similar in DC and epithelial cells. However, this phenotype was not correlated with the bacterial proliferation in SCVs in juxtanuclear positions as reported for infected epithelial cells (1).

In DC, the formation of tubular endosomal compartments has been observed that are involved in the delivery of MHC-II complexes to the plasma membrane (3, 8, 43). These transport events require the function of microtubules, and the interference of Salmonella with microtubule-dependent exocytic transport by means of SPI2-T3SS effector proteins has been observed in other infection models (21).

We propose that intracellular Salmonella, by means of SPI2-T3SS effector proteins, alters the loading of antigen-derived peptides on MHC-II complexes. This effect may be due to redirection of the intracellular transport of membrane vesicles that contain peptides processed for loading onto MHC-II complexes. Although the cell biology of MHC-II presentation has been studied in great detail, the nature of compartments that deliver processed peptides to nascent MHC-II molecules is not well understood (36). One hypothesis is the interference of intracellular Salmonella with cellular transport processes that mediate the fusion of peptide-containing vesicles with MHC-II compartments. The involvement of microtubule-dependent transport has not been investigated but might be a possible cause of the observed modifications in DC. Our current model of the interference of intracellular Salmonella with antigen presentation by DC is summarized in Fig. 7.

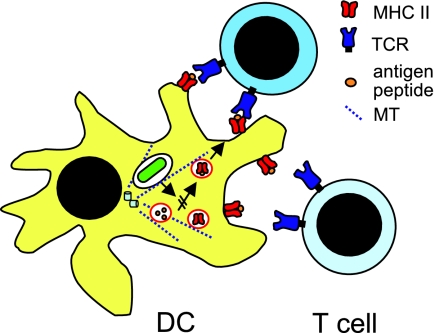

FIG. 7.

Model for intracellular events leading to the inhibition of antigen-presentation by intracellular Salmonella. After uptake by BM-DC, Salmonella resides in a membrane-bound compartment that is not permissive for intracellular replication. The SPI2-T3SS is expressed and translocates a set of effector proteins into the cytoplasm of BM-DC. By mechanisms unknown thus far, these effectors interfere with the delivery of processed peptides to compartments that contain MHC-II complexes competent for peptide loading. A putative point of manipulation is the microtubule (MT)-dependent intracellular transport. SPI2 effectors are known to modify MT-dependent transport in other host cells.

While our initial work was performed with SPI2 mutant strains deficient in the translocation of the entire set of SPI2 effector proteins (7), we extended this analysis here and tested the contribution of individual effector proteins. We observed that a novel subset of SPI2 effector proteins is required to inhibit stimulation of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation by BM-DC. We identified SifA, SspH2, SlrP, SopD2, and PipB2 as effector proteins with a strong effect on the stimulation of T-cell proliferation. A partial contribution of SseF and SseG was observed, but the SseFG double mutant was highly reduced in inhibition of T-cell proliferation. This subset of effectors is conserved between typhoidal and nontyphoidal salmonellae; only sopD2 appears to be a pseudogene in S. enterica serovar Typhi. Mutant strains lacking effectors PipB, SspH1, SifB, SseJ, SseI, GogB, SseK1, or SseK2 did not show a phenotype in BM-DC. Interestingly, SifA, SspH2, SlrP, and PipB2 were each equally required for the inhibition of T-cell proliferation, suggesting a nonredundant role of the effectors. A mutant strain deficient in spiC (alternative designation ssaB) had the same phenotype as a SPI2-null mutant (data not shown).

The presence of the complex set of 18 and possible more effector proteins of the SPI2-T3SS is a puzzling phenomenon. It has been proposed that several effectors may have cryptic or redundant functions. Our work gives the first indication that a subset of the SPI2-T3SS effectors has a cell type-specific function. We have now defined an effector subset that is responsible for the interference of Salmonella with DC functions. Cellular phenotypes have only been characterized in detail for one of the proteins in the subset. SifA is involved in Salmonella-induced filament (SIF) formation and required to maintain the integrity of the SCV (2). Recently, it was shown that SifA affects the recruitment of kinesin to the SCV (4). SseF and SseG also contribute to SIF formation and alterations of the microtubule cytoskeleton and affect the positioning of the SCV in infected host cells (1, 30). Our group also found that the function of SseF is required to redirect secretory transport of the host cell (21). SopD2 and PipB2 are further effectors that are targeted to late endosomal compartments and affect SIF formation (5, 19). A mutant strain deficient in SopD2 was reported to be attenuated in systemic virulence (18). PipB2 is present in detergent resistant microdomains or lipid rafts after translocation into host cells (20). SlrP is an effector protein that is translocated by both the SPI2-T3SS and the SPI1-T3SS involved in the invasion of nonphagocytic cells by Salmonella (37). SlrP contains leucine-rich repeats and shares 39% identity with SspH2 (26). A function of SlrP in Salmonella pathogenesis has not been defined to date. SspH2 has been shown to interfere with the actin cytoskeleton of host cells after translocation by the SPI2-T3SS. A binding of SspH2 to the F-actin cross-linking host cell protein filamin has been reported (25). However, SspH2 function is not required for the known SPI2-dependent virulence functions (systemic pathogenesis) or cellular phenotypes (intracellular replication).

A common characteristic of SifA, SseF, SseG, SopD2, and PipB2 is their association with endosomal membranes after translocation, the role in SIF formation in epithelial cells, and their interference with cellular transport of the host cell. In contrast, translocated SlrP and SspH2 are not reported to be associated with endosomal membranes, and no effect of these proteins on SIF formation or cellular transport has been reported. A previous study reported that the sifA strain exhibits similar characteristics in macrophages and DC, i.e., the loss of the membrane of the SCV and the escape into the host cell cytoplasm (29). We analyzed whether the reduced inhibition of antigen presentation of the sifA strain is linked to this phenotype. Interestingly, in our experimental setting we did not observe that the sifA strains loses the SCV membrane and subsequently escapes into the cytoplasm (data not shown). The reasons for these disparate results are unknown and await further investigation.

Inhibition of antigen presentation is a common mechanism in viral pathogenesis, and various viral proteins have been characterized that interfere with the activation of and processing and presentation of antigens by APC (for a review, see reference 15). The mechanisms of interference are less well understood for intracellular bacterial pathogens. For Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an interference with autophagosome formation has been reported that may also affect the processing and loading of mycobacterial antigens (reviewed in reference 10). The infection of DC by mycobacteria and the impairment of DC functions such as migration and antigen presentation has been observed in vivo (45). A recent study reported that Mycobacterium rapidly induces DC maturation and that this activity results in reduced presentation of peptides on MHC-II without affecting the CD1-dependent presentation of lipid antigens (14). Virulence factors secreted by intracellular Brucella abortus interfere with the maturation of infected DC, thus reducing the capacity of these cells in antigen presentation (33). The obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia spp. does not interfere with antigen presentation in DC (31). However, a secreted protease of Chlamydia trachomatis was reported to degrade host cell transcription factors that are required for the expression of MHC-I complexes (47). Thus far, the manipulation of DC function by T3SS effector proteins appear to be restricted to Salmonella and a unique mechanism to control the adaptive immune responses of the host. It will be of future interest to precisely define the molecular mechanisms by which Salmonella effector proteins interfere with transport events in DC.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grants HE1964/7-2 and 7-3 as part of the priority program Novel Strategies for Vaccination.

We thank Cédric Cheminay for the initial experiments on the role of SPI2 effectors and Roopa Rajashekar for stimulating discussions. The excellent technical support by Daniela Jäckel is gratefully acknowledged.

Editor: A. J. Bäumler

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahams, G. L., P. Müller, and M. Hensel. 2006. Functional dissection of SseF, a type III effector protein involved in positioning the Salmonella-containing vacuole. Traffic 7950-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beuzon, C. R., S. Meresse, K. E. Unsworth, J. Ruiz-Albert, S. Garvis, S. R. Waterman, T. A. Ryder, E. Boucrot, and D. W. Holden. 2000. Salmonella maintains the integrity of its intracellular vacuole through the action of SifA. EMBO J. 193235-3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boes, M., J. Cerny, R. Massol, M. Op den Brouw, T. Kirchhausen, J. Chen, and H. L. Ploegh. 2002. T-cell engagement of dendritic cells rapidly rearranges MHC class II transport. Nature 418983-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucrot, E., T. Henry, J. P. Borg, J. P. Gorvel, and S. Meresse. 2005. The intracellular fate of Salmonella depends on the recruitment of kinesin. Science 3081174-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brumell, J. H., S. Kujat-Choy, N. F. Brown, B. A. Vallance, L. A. Knodler, and B. B. Finlay. 2003. SopD2 is a novel type III secreted effector of Salmonella typhimurium that targets late endocytic compartments upon delivery into host cells. Traffic 436-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakravortty, D., I. Hansen-Wester, and M. Hensel. 2002. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 mediates protection of intracellular Salmonella from reactive nitrogen intermediates. J. Exp. Med. 1951155-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheminay, C., A. Möhlenbrink, and M. Hensel. 2005. Intracellular Salmonella inhibit antigen presentation by dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1742892-2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow, A., D. Toomre, W. Garrett, and I. Mellman. 2002. Dendritic cell maturation triggers retrograde MHC class II transport from lysosomes to the plasma membrane. Nature 418988-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornelis, G. R. 2006. The type III secretion injectisome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4811-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deretic, V. 2006. Autophagy as an immune defense mechanism. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18375-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galan, J. E., and H. Wolf-Watz. 2006. Protein delivery into eukaryotic cells by type III secretion machines. Nature 444567-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen-Wester, I., B. Stecher, and M. Hensel. 2002. Type III secretion of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium translocated effectors and SseFG. Infect. Immun. 701403-1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haraga, A., M. B. Ohlson, and S. I. Miller. 2008. Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 653-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hava, D. L., N. van der Wel, N. Cohen, C. C. Dascher, D. Houben, L. Leon, S. Agarwal, M. Sugita, M. van Zon, S. C. Kent, H. Shams, P. J. Peters, and M. B. Brenner. 2008. Evasion of peptide, but not lipid antigen presentation, through pathogen-induced dendritic cell maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10511281-11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hegde, N. R., M. S. Chevalier, and D. C. Johnson. 2003. Viral inhibition of MHC class II antigen presentation. Trends Immunol. 24278-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hensel, M., J. E. Shea, S. R. Waterman, R. Mundy, T. Nikolaus, G. Banks, A. Vazquez-Torres, C. Gleeson, F. Fang, and D. W. Holden. 1998. Genes encoding putative effector proteins of the type III secretion system of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 are required for bacterial virulence and proliferation in macrophages. Mol. Microbiol. 30163-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jantsch, J., C. Cheminay, D. Chakravortty, T. Lindig, J. Hein, and M. Hensel. 2003. Intracellular activities of Salmonella enterica in murine dendritic cells. Cell. Microbiol. 5933-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang, X., O. W. Rossanese, N. F. Brown, S. Kujat-Choy, J. E. Galan, B. B. Finlay, and J. H. Brumell. 2004. The related effector proteins SopD and SopD2 from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium contribute to virulence during systemic infection of mice. Mol. Microbiol. 541186-1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knodler, L. A., and O. Steele-Mortimer. 2005. The Salmonella effector PipB2 affects late endosome/lysosome distribution to mediate Sif extension. Mol. Biol. Cell 164108-4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knodler, L. A., B. A. Vallance, M. Hensel, D. Jäckel, B. B. Finlay, and O. Steele-Mortimer. 2003. Salmonella type III effectors PipB and PipB2 are targeted to detergent-resistant microdomains on internal host cell membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 49685-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhle, V., G. L. Abrahams, and M. Hensel. 2006. Intracellular Salmonella enterica redirect exocytic transport processes in a Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent manner. Traffic 7716-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhle, V., and M. Hensel. 2004. Cellular microbiology of intracellular Salmonella enterica: functions of the type III secretion system encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 2. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 612812-2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhle, V., D. Jäckel, and M. Hensel. 2004. Effector proteins encoded by Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 interfere with the microtubule cytoskeleton after translocation into host cells. Traffic 5356-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mellman, I., and R. M. Steinman. 2001. Dendritic cells: specialized and regulated antigen processing machines. Cell 106255-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miao, E. A., M. Brittnacher, A. Haraga, R. L. Jeng, M. D. Welch, and S. I. Miller. 2003. Salmonella effectors translocated across the vacuolar membrane interact with the actin cytoskeleton. Mol. Microbiol. 48401-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miao, E. A., C. A. Scherer, R. M. Tsolis, R. A. Kingsley, L. G. Adams, A. J. Bäumler, and S. I. Miller. 1999. Salmonella typhimurium leucine-rich repeat proteins are targeted to the SPI1 and SPI2 type III secretion systems. Mol. Microbiol. 34850-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niedergang, F., J. C. Sirard, C. T. Blanc, and J. P. Kraehenbuhl. 2000. Entry and survival of Salmonella typhimurium in dendritic cells and presentation of recombinant antigens do not require macrophage-specific virulence factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9714650-14655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obert, S., R. J. O'Connor, S. Schmid, and P. Hearing. 1994. The adenovirus E4-6/7 protein transactivates the E2 promoter by inducing dimerization of a heteromeric E2F complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 141333-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petrovska, L., R. J. Aspinall, L. Barber, S. Clare, C. P. Simmons, R. Stratford, S. A. Khan, N. R. Lemoine, G. Frankel, D. W. Holden, and G. Dougan. 2004. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium interaction with dendritic cells: impact of the sifA gene. Cell. Microbiol. 61071-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramsden, A. E., L. J. Mota, S. Munter, S. L. Shorte, and D. W. Holden. 2007. The SPI-2 type III secretion system restricts motility of Salmonella-containing vacuoles. Cell. Microbiol. 92517-2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rey-Ladino, J., X. Jiang, B. R. Gabel, C. Shen, and R. C. Brunham. 2007. Survival of Chlamydia muridarum within dendritic cells. Infect. Immun. 753707-3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salcedo, S. P., and D. W. Holden. 2003. SseG, a virulence protein that targets Salmonella to the Golgi network. EMBO J. 225003-5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salcedo, S. P., M. I. Marchesini, H. Lelouard, E. Fugier, G. Jolly, S. Balor, A. Muller, N. Lapaque, O. Demaria, L. Alexopoulou, D. J. Comerci, R. A. Ugalde, P. Pierre, and J. P. Gorvel. 2008. Brucella control of dendritic cell maturation is dependent on the TIR-containing protein Btp1. PLoS Pathog. 4e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tampe, R., D. Tyvoll, and H. M. McConnell. 1991. Reactions of the subunits of the class II major histocompatibility complex molecule IAd. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 8810667-10670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tobar, J. A., L. J. Carreno, S. M. Bueno, P. A. Gonzalez, J. E. Mora, S. A. Quezada, and A. M. Kalergis. 2006. Virulent Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium evades adaptive immunity by preventing dendritic cells from activating T cells. Infect. Immun. 746438-6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trombetta, E. S., and I. Mellman. 2005. Cell biology of antigen processing in vitro and in vivo. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23975-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsolis, R. M., S. M. Townsend, E. A. Miao, S. I. Miller, T. A. Ficht, L. G. Adams, and A. J. Bäumler. 1999. Identification of a putative Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium host range factor with homology to IpaH and YopM by signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 676385-6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uchiya, K., M. A. Barbieri, K. Funato, A. H. Shah, P. D. Stahl, and E. A. Groisman. 1999. A Salmonella virulence protein that inhibits cellular trafficking. EMBO J. 183924-3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valdivia, R. H., and S. Falkow. 1996. Bacterial genetics by flow cytometry: rapid isolation of Salmonella typhimurium acid-inducible promoters by differential fluorescence induction. Mol. Microbiol. 22367-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Kooyk, Y., and T. B. Geijtenbeek. 2003. DC-SIGN: escape mechanism for pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3697-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vazquez-Torres, A., Y. Xu, J. Jones-Carson, D. W. Holden, S. M. Lucia, M. C. Dinauer, P. Mastroeni, and F. C. Fang. 2000. Salmonella pathogenicity island 2-dependent evasion of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Science 2871655-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villadangos, J. A., P. Schnorrer, and N. S. Wilson. 2005. Control of MHC class II antigen presentation in dendritic cells: a balance between creative and destructive forces. Immunol. Rev. 207191-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vyas, J. M., Y. M. Kim, K. Artavanis-Tsakonas, J. C. Love, A. G. Van der Veen, and H. L. Ploegh. 2007. Tubulation of class II MHC compartments is microtubule dependent and involves multiple endolysosomal membrane proteins in primary dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 1787199-7210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, R. F., and S. R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing, and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wolf, A. J., B. Linas, G. J. Trevejo-Nunez, E. Kincaid, T. Tamura, K. Takatsu, and J. D. Ernst. 2007. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infects dendritic cells with high frequency and impairs their function in vivo. J. Immunol. 1792509-2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, L., and V. N. KewalRamani. 2006. Dendritic-cell interactions with HIV: infection and viral dissemination. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6859-868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong, G., P. Fan, H. Ji, F. Dong, and Y. Huang. 2001. Identification of a chlamydial protease-like activity factor responsible for the degradation of host transcription factors. J. Exp. Med. 193935-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]