Abstract

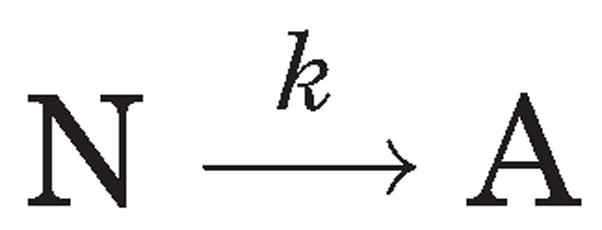

The physical phenomenon of aggregation can have profound impact on the stability of therapeutic proteins. This study focuses on the aggregation behavior of recombinant human FVIII (rFVIII), a multi-domain protein used as the first line of therapy for hemophilia A, a bleeding disorder caused by the deficiency or dysfunction of factor VIII (FVIII). Thermal denaturation of rFVIII was investigated using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The dependence of unfolding on heating rate indicated that the thermal denaturation of the protein was at least partly under kinetic control. The data was interpreted in terms of a simple two-state kinetic model, , where k is a first-order kinetic constant that changes with temperature, as given by the Arrhenius equation. Analysis of the data in terms of the above scheme suggested that under the experimental conditions used in this study, the rate-controlling step in the aggregation of rFVIII may be a unimolecular reaction involving conformational changes.

Keywords: rFVIII, physical instability, multi-domain, irreversible denaturation, kinetic control

INTRODUCTION

Protein aggregation is an important practical problem for the use of proteins as therapeutics. The physical phenomenon of aggregation can have profound impact on the stability of proteins.1 Not only may a loss of activity occur, but the presence of aggregates has been shown to often elicit a greater antibody mediated immune response2,3 which could be detrimental to the use of proteins as therapeutics.

The mechanisms of protein aggregation are complex. Proteins subjected to thermal stress can aggregate from the fully unfolded state4 but partially unfolded states have more frequently been implicated in aggregation processes;1,5 an example of the latter is the transition to molten globule states, in which proteins retain majority of their secondary structural features while losing most of their tertiary structure. Such partially unfolded states have more exposed apolar regions and are more prone to aggregation than native or unfolded conformations. For proteins such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ)6 and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF),7 it has been clearly demonstrated that extensive unfolding or formation of molten globule states is not a prerequisite for aggregation. Rather, aggregation seems to occur from an expanded state that more resembles the native protein than substantially disrupted structures.

Factor VIII (FVIII) is comprised of six structurally distinct domains: (NH2) –A1, A2, B, A3, C1, and C2– (COOH).8,9 It serves as a critical cofactor in the blood coagulation cascade. Deficiency of FVIII causes hemophilia A, a genetic bleeding disorder.10 Administration of recombinant human FVIII (rFVIII) that is structurally similar to plasma derived FVIII is the first line of therapy for hemophilia A. It has been reported that rFVIII can aggregate as a result of subtle conformational changes in the tertiary structure of the protein.11 Recently, it was shown that conformational changes in the lipid binding region that is localized to the C2 domain of rFVIII may be involved in the initiation of the aggregation process in rFVIII.12 Little is known, however, about the kinetics of rFVIII aggregation. Understanding the underlying kinetics could aid in designing strategies that interfere with the molecular events leading to aggregation of rFVIII. In the present study, the kinetics of rFVIII aggregation induced by thermal stress was investigated. Results from this study indicate that structural perturbation of rFVIII is a complex, kinetically controlled process in which the aggregation of the protein exhibits apparent first-order kinetics.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Purified full-length rFVIII expressed in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) was provided by Baxter Biosciences (Carlsband, CA). Buffer salts were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ) or Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Circular Dichroism Studies

CD spectra were acquired on a JASCO-715 spectropolarimeter calibrated with d-10 camphor sulfonic acid. The protein concentration used was ~20 or 250 μg/mL in quartz cuvettes with pathlengths of 10 or 1 mm, respectively. Samples were scanned in the range of 255 to 208 nm for secondary structure analysis. The unfolding of the protein was followed by monitoring the ellipticity at 215 nm over the temperature range of 20–80°C with a 2 min holding time every 5°C. The temperature dependent spectra were acquired using a Peltier 300 RTS unit and the profiles were generated using the software provided by the manufacturer.

Heating Rate Dependent Studies

Protein unfolding profiles were acquired at heating rates of 7, 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, and 240°C/h. To minimize the loss of buffer due to evaporation, the cuvette was sealed with a Teflon cap. The sample temperature was monitored by inserting a temperature probe in the sample cell holder close to the cuvette, as recommended by the manufacturer. For all heating rate dependent studies, the data were represented as δθ, (change in ellipticity) as a function of temperature. The data was represented in this manner to account for any variations in the starting protein concentration. δθ was computed as θt − θnative, where θnative is the ellipticity of the protein in the native state and θt is the ellipticity at any given temperature. θnative was estimated by computing the mean ellipticity at initial temperatures. The transition temperatures (Tm), for the unfolding profiles were determined by fitting the data to a sigmoid function using WinNonlin (Pharsight Corporation, Mountainview, CA):

| (1) |

where Yobserved is the ellipticity at 215 nm at any given temperature T, Ynative is the ellipticity value for the native state, Tm is the transition temperature, and gamma (γ) is the cooperativity function. Δm denotes the magnitude of the ellipticity change and is defined as (Ynative − Yunfolded), where Yunfolded is the ellipticity value of the unfolded state. For concentration-dependent studies the data was represented as percent change in θ at 215 nm and computed as:

| (2) |

where θnative is the ellipticity at 215 nm for the protein in its native state (20°C) and θt is the ellipticity at any given temperature.

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

High Performance Size Exclusion Chromatography (HP-SEC) was performed as described previously.12 Briefly, the analytical column used was a Biosep SEC S4000 of 4.6 mm × 300 mm. The column was maintained at 20°C. The chromatography system was equipped with a Waters 510 HPLC Pump, a Rheodyne injector with a 50 μL PEEK sample loop and a Hitachi F1050 fluorescence detector. Excitation wavelength was set at 285 nm and elution of the protein was monitored at 335 nm. Gel filtration was carried out under isocratic conditions at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min using an aqueous buffer consisting of 10 mM MOPS, 5 mM CaCl2, and 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.0. For studies of the heating dependence of unfolding, the protein was thermally disrupted at 15°C/h; samples were withdrawn at various temperatures, stored on ice, and analyzed within 3 h. We previously established that the column could resolve and detect the existence of as little as 1.4% aggregated protein (by weight) in the presence of native protein.12

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Kinetics of rFVIII Aggregation

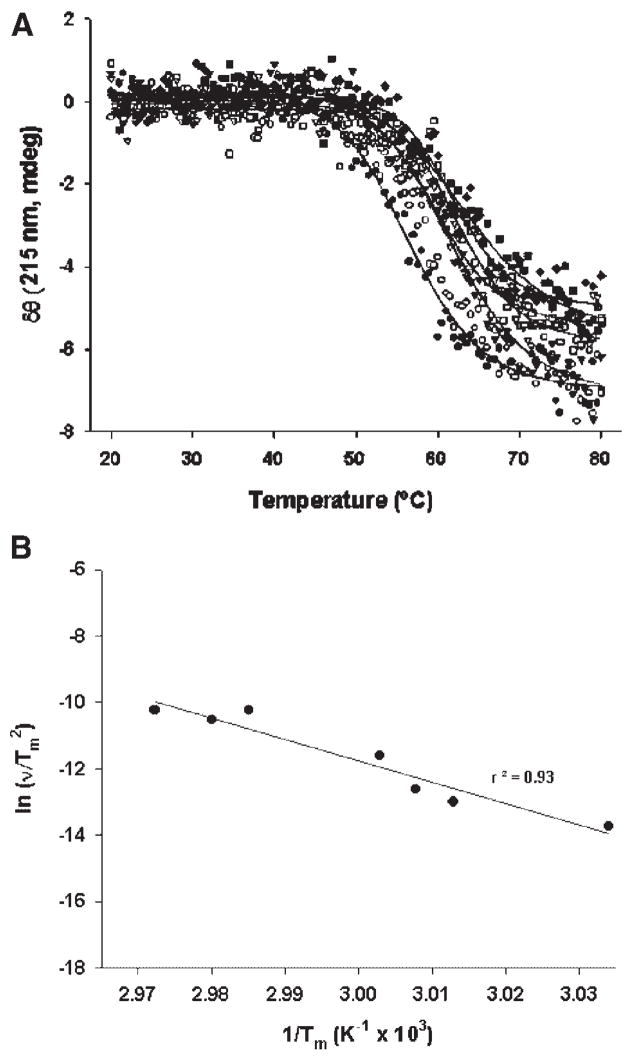

We previously reported that aggregation was observed during the unfolding of rFVIII following thermal perturbation of the protein and that this aggregation was irreversible.12 Based on thermal denaturation studies of multi-domain proteins like phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK)13 and thermolysin, Sanchez-Ruiz et al., demonstrated that irreversible denaturation defies analysis by standard equilibrium methods, and suggested that the unfolding may be a kinetically controlled process.14 To investigate whether kinetically controlled processes play a role in the thermal unfolding of rFVIII, we determined the unfolding profile of rFVIII at various heating rates. The data reported in Figure 1 show that the transition temperature (Tm) is strongly dependent on the heating rate. Thus the process of rFVIII unfolding appears to be kinetically determined. Such heating rate dependency on unfolding transitions has also been observed for other proteins including IFN-γ,15 Immunoglobulin G (IgG)16 and streptokinase.17

Figure 1.

(A) Change in ellipticity of rFVIII (in 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2, pH = 7.0) as a function of heating rate: The secondary structure transition of rFVIII was monitored at 215 nm over the temperature range of 20–80°C at different heating rates; ●, 7°C/h; ■, 15°C/h; ▼, 22°C/h; ▽, 60°C/h; □, 120°C/h; ◇, 180°C/h; ◆, 240°C/h. The protein concentration was ~20 μg/mL and the path length of quartz cuvette was 10 mm. The solid lines represent the fitting obtained using Equation 1. (B) Plot of versus 1/Tm.ν, heating rate; Tm, temperature at which 50% change in ellipticity at 215 nm is observed. Slope and intercept for the above plot is −Ea/R and ln (AR/Ea), respectively. Ea, activation energy; R, universal gas constant; A, frequency factor. Each data point corresponds to one of the seven heating rates used.

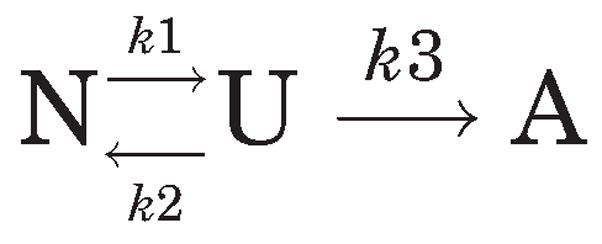

In general, the heating rate dependence of protein thermal structural perturbations can be understood in terms of the Lumry-Eyring model18 as shown below. According to this framework, a reversible unfolding step is followed by an irreversible event:

where A is the final (aggregated) state of the native protein N, irreversibly arrived at from the reversible altered form U. In this scheme, the first-order kinetic constants for each reaction j are represented by kj, which varies with temperature according to the Arrhenius equation. If k3 ≫ k2, then all of U will be converted into A, and the process can be represented by the simpler kinetic scheme 2 as discussed in detail by Sanchez-Ruiz et al.:14

Scheme 2.

Scheme 2 represents the limiting case of the Lumry-Eyring model consisting of only two populated states, the native (N) and the final aggregated state (A); This predicts that k is a first-order kinetic constant that varies with temperature, as given by the Arrhenius equation. Based on this simple kinetic model, Tm should vary with heating rate (ν) according to the equation:

| (3) |

where A is the frequency factor, Ea is the activation energy of the unfolding step and R is the gas constant. Therefore, a linear plot of versus 1/Tm should indicate a first-order reaction with slope of −Ea/R. Figure 1B shows the relevant data acquired using seven scan rates and expressed in terms of Eq. 2. The activation energy (Ea) for the transition was found to be ~535 kJ/mole (~128 kcal/mole) and compares well with the Ea associated with the two transitions observed for the multi-domain protein IgG (Ea for the two transitions were reported to be 456 kJ/mole (~109 kcal/mole) and 692 kJ/mole (~165 kcal/mole)).16 Thus, analysis of the data in terms of kinetic scheme 2 suggests that under the experimental conditions used in this study, the rate-controlling step in the aggregation of rFVIII may be a unimolecular reaction involving protein conformational changes.

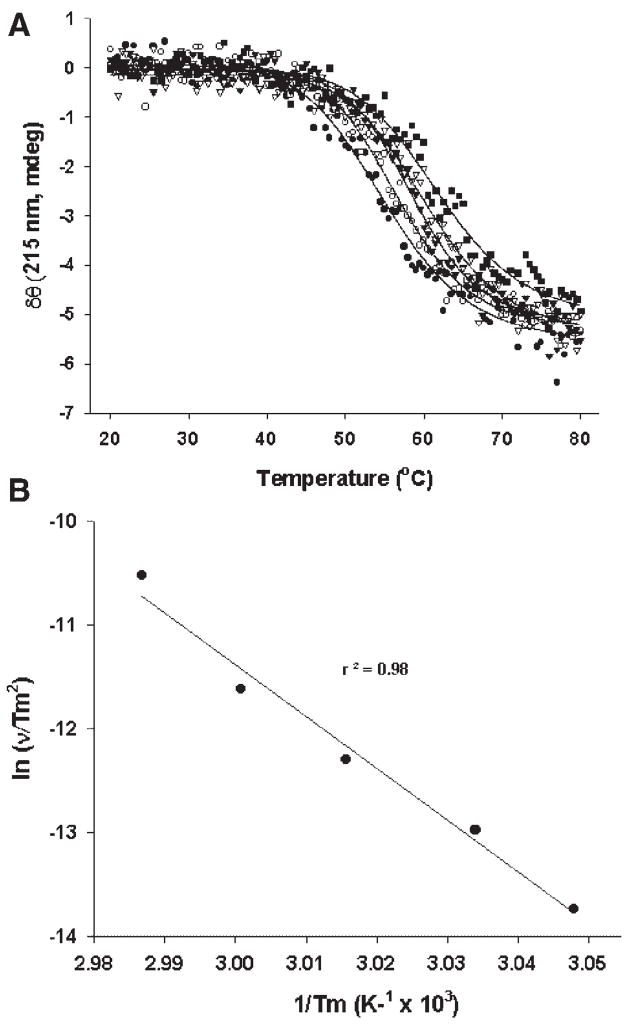

The heating rate dependent studies discussed above were carried out in buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2, pH 7, to minimize metal dependent effects. Tris, however, has a high temperature coefficient that will result in changes in pH as the temperature is increased1. Hence, the observed changes in Tm as a function of heating rate could be influenced by both pH and temperature. Therefore, heating rate studies were also carried out in buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM MOPS, 5 mM CaCl2, pH 6, since MOPS has a much lower temperature coefficient.19 As observed in Figure 2, the Tm was again found to be dependent on the heating rate, again suggesting that the denaturation of rFVIII is kinetically controlled, irrespective of the pH. Analysis of the data based on scheme 2 and plotting the data (Fig. 2B) in terms of Eq. 2 further confirmed that the rate-limiting step in the unfolding of rFVIII is probably a unimolecular reaction presumably involving conformational changes. The activation energy ofthe transition was ~414 kJ/mole (~99 kcal/mole), similar to that of the Tris case. Based on our previously reported observations,12 we believe that the conformational changes involve at least the lipid-binding region, 2303–2332 of the C2 domain.

Figure 2.

(A) Change in ellipticity of rFVIII (in 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM MOPS, 5 mM CaCl2, pH 6.0) as a function of heating rate: The secondary structure transition of rFVIII was monitored at 215 nm over the temperature range of 20–80°C at different heating rates; ●, 7°C/h; ■, 15°C/h; □, 30°C/h; ▼, 60°C/h; ▽, 180°C/h. The protein concentration was ~20 μg/mL and the path length of quartz cuvette was 10 mm. The solid lines represent the fitting obtained using equation 1. (B) Plot of versus 1/Tm.ν, heating rate; Tm, temperature at which 50% change in ellipticity at 215 nm is observed. Slope and intercept for the above plot is −Ea/R and ln (AR/Ea), respectively. Ea, activation energy; R, universal gas constant; A, frequency factor. Each data point corresponds to one of the five heating rates used.

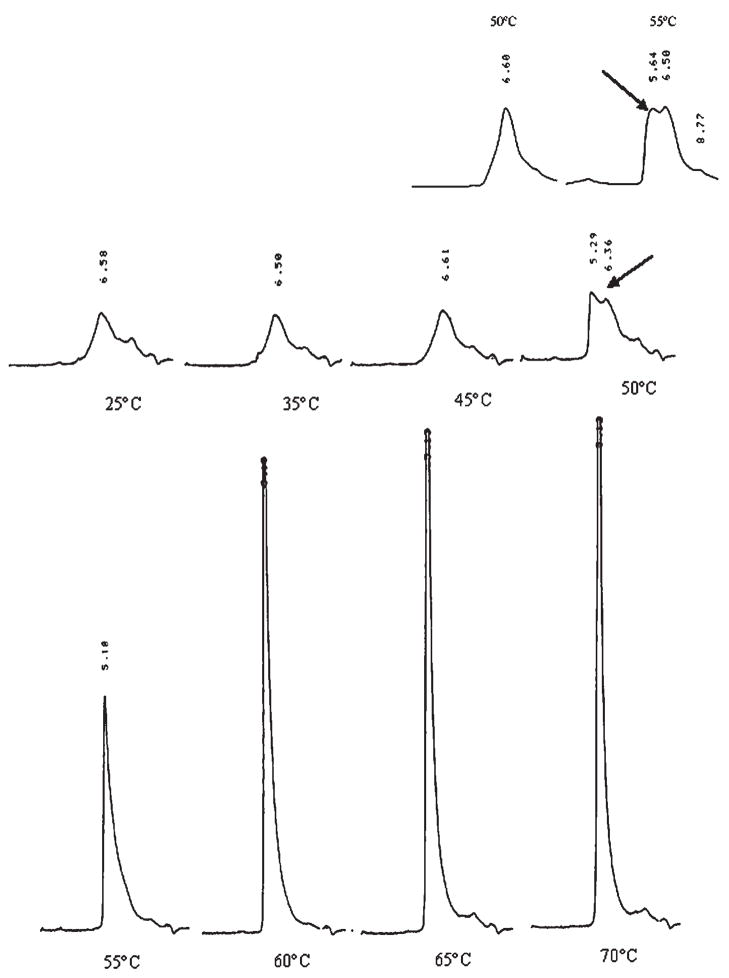

The effect of heating rate on the unfolding of rFVIII was also monitored using SEC. Figure 3 shows SEC profiles of rFVIII heated at 15°C/h (with a 2 min holding time) over the temperature of 25–75°C. Previously, we reported the SEC profiles of rFVIII subjected to unfolding at 60°C/h.12 While the native protein eluted as a broad peak at ~6.56 min (25°C), the aggregated rFVIII eluted at ~5.1–5.2 min (in the void volume). Following thermal unfolding of the protein at 60°C/h,12 the SEC chromatograms did not show any change up to 50°C. At 55°C, two peaks were observed in the chromatogram; one at ~5.64 min and the other at ~6.50 min suggesting the coexistence of small aggregates and native protein during the transition (Fig. 3 inset). On further heating, the elution time of the peak composed of protein aggregates progressively decreased and the concomitant decrease in peak width was attributed to the increase in size of the aggregates.12 In comparison, the SEC profiles on unfolding the protein at 15°C/h showed distinct differences (Fig. 3). While no changes in the chromatograms were observed from 25 to 45°C, the profile at 50°C displayed two peaks; one that eluted at ~5.29 min and the other at ~6.36 min. This suggests the existence of smaller aggregates at earlier temperatures following unfolding of rFVIII at the lower heating rate (compare the SEC chromatograms in the main figure and inset). Furthermore, unlike the SEC profiles obtained after heating the protein at 60°C/h, there was no apparent progressive decrease in elution time with increases in temperature. At elevated temperatures (55–70°C), the elution time of the peaks was comparable to that observed for completely aggregated protein which elutes at ~5.1 to ~5.2 min (void volume). The difference in elution profiles could be the result of a greater accumulation and increase in size of aggregates at a lower heating rate (see below).

Figure 3.

Size exclusion chromatographic profiles of rFVIII in 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.0) heated to various temperatures at a heating rate of 15°C/h. The elution times are indicated in min. Inset: SEC profiles of rFVIII at 50 and 55°C following unfolding at 60°C/h (from reference 12). Arrows indicate the peak containing aggregates that coexist with the native protein. The temperature of the column was maintained at 20°C.

Differences dependent upon heating rate were observed not only in Tm, but also in Δm, the magnitude of the spectral changes. At a heating rate of 7°C/h, the Δm value was ~7.05 ellipticity units, whereas for a heating rate of 240°C/h, Δm decreased ~5.67 units. As interpreted based on SEC studies12 (and Fig. 3), is that the unfolding transition of rFVIII involves the presence of native protein as well as aggregates; thus Δm reflects the relative population of these two species. The decrease in Δm at higher heating rates suggests that there is minimal accumulation of aggregates during the transition; the protein unfolds and reaches the final aggregated state rapidly, with less time spent in transition. In contrast, at a lower heating rate, the transition time of the protein is longer, resulting in greater accumulation and increase in size of aggregates before reaching the final aggregated state.

It is important to note that an equilibration time of 2 min was used in the experiments described above to investigate the unfolding profiles of rFVIII. When equilibration times were increased to 5 min, it was observed that the unfolding profile of the protein was distorted due to aggregation (data not shown), thereby confounding the determination of Tm. The effect of heating rate and incubation time at elevated temperatures emphasizes the impact of the aggregation kinetics of the protein on measurements of equilibrium unfolding; the unfolding of rFVIII is a kinetically controlled process in which the aggregation kinetics are influenced by the duration of time the protein spends in transition.

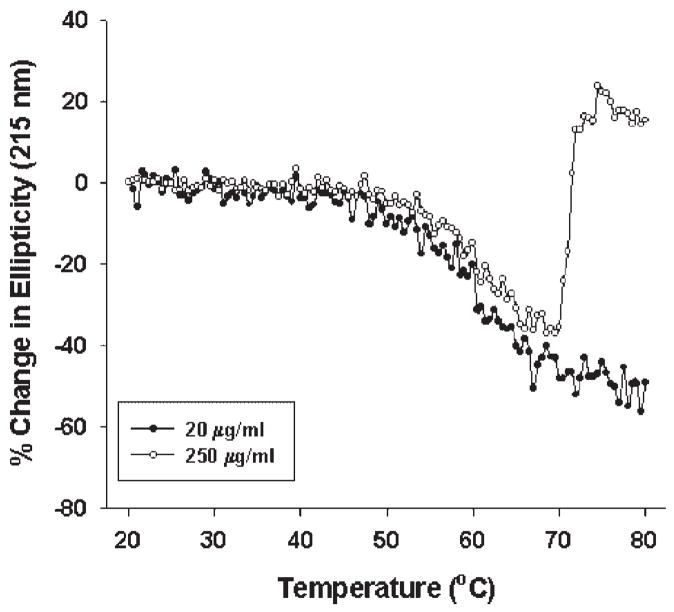

Effect of Protein Concentration

To determine whether the aggregation of rFVIII was influenced by concentration of the protein used, thermal perturbation studies (at 60°C/h) were carried out at protein concentrations of 20 and 250 μg/mL in MOPS buffer (300 mM NaCl, 10 mM MOPS, 5 mM CaCl2, pH 6). Shown in Figure 4 is the percent change in ellipticity at 215 nm as a function of temperature. At the lower protein concentration, the percent change in ellipticity was minimal over the temperature range of 20 to 50°C. At temperatures greater than 50°C, the change in ellipticity decreased and was consistent with an increase in negative ellipticity at 215 nm. Analysis of the unfolding profile suggests that the mid-point of the transition was ~60°C. At a higher protein concentration, however, the change in ellipticity was altered, with evidence of a marked transition, especially at elevated temperatures (>65°C). The decrease in change in ellipticity was manifested as a decrease in negative ellipticity at 215 nm. Unfortunately, it was not possible to ascertain a true Tm since this decrease in negative ellipticity is distorted by aggregation, as confirmed by SEC. The resultant aggregates appear to be stabilized by intermolecular beta strands as shown by previous CD and FTIR measurements.11,12 Most importantly, the above results clearly demonstrated that aggregation is more pronounced at higher protein concentration.

Figure 4.

Percent change in ellipticity of rFVIII (in 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM MOPS, 5 mM CaCl2, pH 6.0) as a function of protein concentration: Secondary structure transition of rFVIII was monitored at 215 nm over the temperature range of 20–80°C (at 60°C/h) at different concentrations. The pathlength of quartz cuvette was 1 cm (for 20 μg/mL) or 0.1 cm (for 250 μg/mL).

Equilibrium unfolding is often used to screen excipients for the development of protein formulations. However, minor conformational changes that resemble the native state can lead to aggregation4,6 interfering with the equilibrium unfolding measurements.14 In addition, usage of higher protein concentrations can accelerate the kinetically controlled aggregation process. Thus, formulation development requires the characterization of minor conformational changes or aggregation prone states and their kinetics. Previous findings on the molecular details of the aggregation prone state of rFVIII11,12 and their kinetics (present study) have contributed towards the rational design of a rFVIII–phosphoserine (PS) complex with improved physical stability.12

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the thermal unfolding of rFVIII is a kinetically controlled process that can simply be described by a two-state kinetic model under the experimental conditions employed.

Scheme 1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NHLBI, National Institute of Health grant R01 HL-70227 to SVB. The authors thank the Pharmaceutical Sciences Instrumentation Facility of the University at Buffalo (SUNY) for the use of the Circular Dichroism spectropolarimeter, which was obtained through Shared Instrumentation Grants RR13665 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- CD

circular dichroism

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- PGK

phosphoglycerate kinase

- rFVIII

recombinant human factor VIII

- rhGCSF

recombinant human granulocyte colony stimulating factor

- rhIFN-γ

recombinant human interferon gamma

- PS

phosphoserine

- SEC

size exclusion chromatography

Footnotes

The pH decreases approximately by 0.03 U/°C from 5 to 25°C and by 0.025 U/°C from 25 to 37°C. Based on the assumption that pH decreases linearly (by 0.025 U/°C) over the range of 25–80°C, the pH at elevated temperatures was estimated to be ~5.5 to 6. Hence subsequent heating rate dependent studies were carried out in MOPS buffer with the pH fixed at 6.0. Since MOPS displays a lower temperature coefficient, pH changes will be minimal over the temperature range employed in these thermal unfolding studies.

References

- 1.Manning MC, Patel K, Borchardt RT. Stability of protein pharmaceuticals. Pharm Res. 1989;6:903–918. doi: 10.1023/a:1015929109894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun A, Kwee L, Labow MA, Alsenz J. Protein aggregates seem to play a key role among the parameters influencing the antigenicity of interferon alpha (IFN-alpha) in normal and transgenic mice. Pharm Res. 1997;14:1472–1478. doi: 10.1023/a:1012193326789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schellekens H. Bioequivalence and the immunogenicity of biopharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nrd818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi EY, Krishnan S, Randolph TW, Carpenter JF. Physical stability of proteins in aqueous solution: Mechanism and driving forces in nonnative protein aggregation. Pharm Res. 2003;20:1325–1336. doi: 10.1023/a:1025771421906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fink AL. Protein aggregation: Folding aggregates, inclusion bodies and amyloid. Folding Design. 1998;3:R9–R23. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kendrick BS, Carpenter JF, Cleland JL, Randolph TW. A transient expansion of the native state precedes aggregation of recombinant human interferon-gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14142–14146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishnan S, Chi EY, Webb JN, Chang BS, Shan D, Goldenberg M, Manning MC, Randolph TW, Carpenter JF. Aggregation of granulocyte colony stimulating factor under physiological conditions: Characterization and thermodynamic inhibition. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6422–6431. doi: 10.1021/bi012006m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fay PJ. Factor VIII structure and function. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster PA, Zimmerman TS. Factor VIII structure and function. Blood Rev. 1989;3:180–191. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(89)90015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larner AJ. The molecular pathology of haemophilia. Q J Med. 1987;63:473–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grillo AO, Edwards KL, Kashi RS, Shipley KM, Hu L, Besman MJ, Middaugh CR. Conformational origin of the aggregation of recombinant human factor VIII. Biochemistry. 2001;40:586–595. doi: 10.1021/bi001547t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramani K, Purohit VS, Miclea RD, Middaugh CR, Balasubramanian SV. Lipid binding region (2303–2332) is involved in aggregation of recombinant human FVIII (rFVIII) J Pharm Sci. 2005;94:1288–1299. doi: 10.1002/jps.20340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galisteo ML, Mateo PL, Sanchez-Ruiz JM. Kinetic study on the irreversible thermal denaturation of yeast phosphoglycerate kinase. Biochemistry. 1991;30:2061–2066. doi: 10.1021/bi00222a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez-Ruiz JM, Lopez-Lacomba JL, Cortijo M, Mateo PL. Differential scanning calorimetry of the irreversible thermal denaturation of thermolysin. Biochemistry. 1988;27:1648–1652. doi: 10.1021/bi00405a039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kendrick BS, Cleland JL, Lam X, Nguyen T, Randolph TW, Manning MC, Carpenter JF. Aggregation of recombinant human interferon gamma: Kinetics and structural transitions. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87:1069–1076. doi: 10.1021/js9801384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vermeer AW, Norde W. The thermal stability of immunoglobulin: Unfolding and aggregation of a multi-domain protein. Biophys J. 2000;78:394–404. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76602-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azuaga AI, Dobson CM, Mateo PL, Conejero-Lara F. Unfolding and aggregation during the thermal denaturation of streptokinase. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:4121–4133. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lumry R, Eyring H. Conformation changes of proteins. J Phys Chem. 1954;58:110–120. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Derrick TS, Kashi RS, Durrani M, Jhingan A, Middaugh CR. Effect of metal cations on the conformation and inactivation of recombinant human factor VIII. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:2549–2557. doi: 10.1002/jps.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]