Abstract

Molecular function is often predicated on excursions between ground states and higher energy conformers that can play important roles in ligand binding, molecular recognition, enzyme catalysis, and protein folding. The tools of structural biology enable a detailed characterization of ground state structure and dynamics; however, studies of excited state conformations are more difficult because they are of low population and may exist only transiently. Here we describe an approach based on relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy in which structures of invisible, excited states are obtained from chemical shifts and residual anisotropic magnetic interactions. To establish the utility of the approach, we studied an exchanging protein (Abp1p SH3 domain)–ligand (Ark1p peptide) system, in which the peptide is added in only small amounts so that the ligand-bound form is invisible. From a collection of 15N, 1HN, 13Cα, and 13CO chemical shifts, along with 1HN-15N, 1Hα-13Cα, and 1HN-13CO residual dipolar couplings and 13CO residual chemical shift anisotropies, all pertaining to the invisible, bound conformer, the structure of the bound state is determined. The structure so obtained is cross-validated by comparison with 1HN-15N residual dipolar couplings recorded in a second alignment medium. The methodology described opens up the possibility for detailed structural studies of invisible protein conformers at a level of detail that has heretofore been restricted to applications involving visible ground states of proteins.

Keywords: Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG), dynamics, excited state structure, residual dipolar couplings, chemical exchange

Much of structural biology focuses on the generation of static structures of biomolecules, with less consideration of how such structures change in time. This, in part, reflects the sample requirements that are imposed by the different structural methods. In the case of studies using x-ray diffraction, for example, molecular dynamics are minimized due to the crystalline nature of the sample itself, which traps the molecule in a single conformation, and by the liquid nitrogen temperatures that are used in most experiments. In the case of solution NMR spectroscopy, sample conditions are sought that give rise to the “highest quality spectra” that often derive from the most stable form of the protein, and conformational heterogeneity that reflects excursions between different states is thus minimized. Certainly, initial focus on a single static representation is a wise choice, as much can be learned from these high-resolution pictures. However, function is often predicated on excursions between different conformers (1, 2), and it is therefore of interest to obtain detailed structural information about the many different states of a biomolecule that populate its energy landscape.

Of the different conformers that one wishes to study, it is clear that those belonging to the low energy ground state are the most easily probed, because they are populated to the greatest extent. Higher energy states (referred to as excited states in what follows) are often much more recalcitrant to study using existing biophysical approaches because their populations can be small. For example, molecular conformers that are above the ground state in energy by only 3kBT (<2 kcal/mol) are populated to less than 5% and often have very short (micro- to millisecond) lifetimes, rendering them essentially invisible to many of the tools of structural biology.

Solution-based NMR spectroscopy can, in principle, provide detailed information about excited, invisible states so long as they are populated to at least 0.5% and they exchange on the millisecond time-scale with a highly populated, and therefore “visible,” state (3, 4). In these cases, exchange increases the line widths of peaks in spectra of the visible conformer, and this increase can be quantified from so-called Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) relaxation dispersion experiments (3). The kinetics of the exchange process, the populations of the exchanging states, and the absolute values of chemical shift differences between ground and the excited state(s) can be extracted from fits of relaxation dispersion data. The sign of the shift difference and hence the chemical shifts of the excited state can subsequently be obtained by a comparison of peak positions in a series of simple two-dimensional spectra, as described previously (5). We have recently shown that accurate 15N, 1HN, 13Cα, and 13CO chemical shifts of an invisible state corresponding to the bound conformer of a protein–ligand exchanging system could be obtained from fits of relaxation dispersion data (6). It has also recently been shown that variants of the standard CPMG-based relaxation dispersion experiments can be designed for samples dissolved in small amounts of alignment media (7, 8) so that anisotropic interactions, including residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) and residual chemical shift anisotropies (RCSAs) of the invisible state, can be measured. Based on these approaches, accurate values of 1HN-15N, 1Hα-13Cα, and 1HN-13CO RDCs and 13CO RCSAs have been reported in an exchanging protein system (7, 9, 10).

It is well known that protein chemical shifts are related closely to structure (11, 12), and a number of powerful protocols have recently been developed for the calculation of protein structures using only backbone chemical shifts as experimental restraints (13, 14). It is unclear, however, whether the dataase approach used is generally appropriate for the calculation of structures of low populated excited states that may, in some cases, have different structural preferences than those found in well folded proteins. It is therefore important to supplement chemical shifts with both RDCs and RCSAs that are also rich in structural information (15, 16). Thus, with the development of robust methods for the measurement of both chemical shifts and anisotropic interactions in invisible protein states, it is now possible to contemplate structural studies of these “elusive” conformers. Here we study the invisible bound state that is formed on the addition of a small mole fraction (≈5%) of a 17-residue Ark1p peptide (17) to a solution of the Abp1p SH3 domain (18), an exchanging system that we have investigated by CPMG relaxation dispersion methods and for which large amounts of chemical shift (6) and RDC/RCSA data have been recorded (7, 9, 10). We show that restraints available from relaxation dispersion data alone permit the calculation of a well defined ensemble of structures of the invisible bound state, with a pairwise root mean square deviation of backbone atoms of 0.33 ± 0.08 Å. Cross-validation using 1H-15N RDC values measured in a second “orthogonal” alignment frame establishes the accuracy of the structure. This work demonstrates that detailed structural information of low populated, transiently formed conformers can be obtained from restraints measured directly from relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy, and sets the stage for structural studies of invisible protein states in a large variety of exchanging systems.

Results and Discussion

Structural Restraints from Relaxation Dispersion NMR.

The binding of the Abp1p SH3 domain to a 17-residue, positively charged peptide from the yeast protein Ark1p can be well described by a two-site exchange model,

|

with Kd = 0.55 ± 0.05 μM (7). This system has proven to be extremely useful for establishing the methodology necessary for probing structure in invisible excited states because of the ease with which it can be manipulated simply by the addition of different amounts of peptide. For example, for small mole fractions of added peptide, L, P and PL are the “visible, ground” and “invisible, excited states”, respectively. In contrast, when saturating amounts of L are added, PL becomes the visible state. It is thus possible to validate measurements that probe the invisible PL state with those made directly on state PL when it is the dominant conformer using conventional, well established NMR experiments. Here, we focus on the Abp1p–Ark1p system under conditions where PL is invisible (5–10% mole fraction of L) and show that it is possible to calculate ensembles of structures corresponding to the invisible bound conformation based exclusively on structural information from relaxation dispersion experiments.

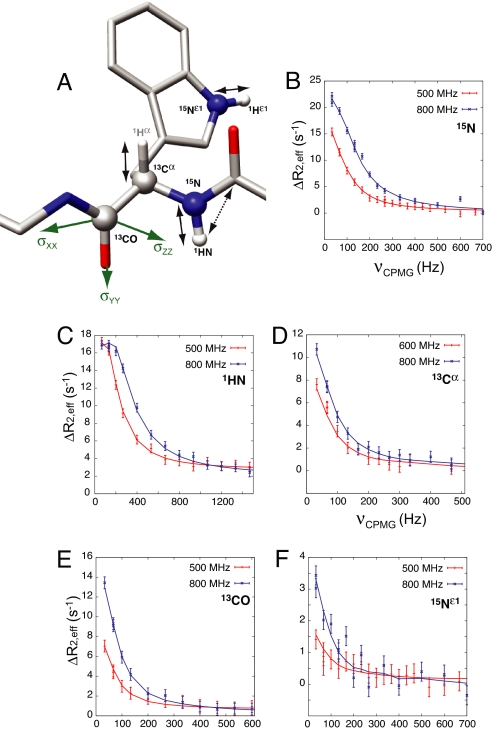

Fig. 1A shows a polypeptide chain trace highlighting the probes that are available in the present study. Relaxation dispersion profiles have been recorded that focus on 15N, 1HN, 13Cα, and 13CO nuclei using previously published experiments (6, 19–21). Data from a given nucleus-type is fitted together to extract absolute values of chemical shift differences between ground (P) and excited (PL) states, |Δϖ| (ppm) or |Δω| (rad/sec), along with the global parameters, kex = kon[L] + koff and pPL, the population of the excited state (3, 7). For each of the four nuclei indicated above, the sign of Δω can be obtained in many cases and hence the chemical shifts of the excited state, following the approach of Skrynnikov et al. (5). Fig. 1 B–F shows examples of dispersion profiles, ΔR2,eff = R2,eff(νCPMG) − R2,eff(∞), where R2,eff is the relaxation rate at a given νCPMG = 1/(2δ) value, and δ is the time between successive refocusing pulses during the CPMG pulse train. In addition to the experiments that are sensitive to |Δω| described above, a second class of dispersion experiment can be performed that “carries” the information about dipolar couplings (7, 8). Here dispersion profiles quantifying the relaxation of nucleus X (15N, 13Cα, 13CO) coupled to nucleus Y in the up or down spin-state are measured; such profiles are sensitive to |Δω ± πΔD|, where ΔD (= DG − DE) is the difference in the XY dipolar coupling in the ground and excited states. The sign of ΔD is obtained once the sign of Δω is known, and because dipolar couplings can be measured readily in the visible ground state (16), values of D in the excited state can be calculated directly from −ΔD + DG. In a third class of experiment, changes in chemical shifts of 13CO nuclei in the excited state upon alignment can be obtained by analysis of relaxation dispersion experiments recorded with and without molecular alignment, as described previously (9). This orients the components of the 13CO chemical shift tensor (Fig. 1A, green), and hence the peptide plane, with respect to the alignment axis, providing another source of structural information. Supporting information (SI) Tables S1–S7 summarize the chemical shift, RDC, and RCSA data of the invisible, ligand-bound state that are used in subsequent structure calculations. A histogram of the distribution of normalized 1HN-15N, 1Hα-13Cα, and 1HN-13CO RDC values is presented in Fig. S1.

Fig. 1.

Probing chemical shifts and residual anisotropic interactions in the invisible, excited state. (A) Stick model of a polypeptide chain fragment highlighting the dipolar (1HN-15N, 1Hα-13Cα, 1HN-13CO) and chemical shift anisotropy (13CO) interactions of the invisible, excited state that are probed (arrows), as well as the chemical shifts (1HN, 15N, 13Cα and 13CO) that are measured (balls) by the relaxation dispersion NMR experiments that were recorded for the present work. (B–F) Typical relaxation dispersion profiles recorded on samples of 15N,2H- (B, C, and F), 13Cα- (D), or 15N,13CO,2H- (E) labeled Abp1p SH3 domain and substoichiometric amounts of Ark1p peptide (≈5–10% by mole fraction, depending on the sample) at static magnetic field strengths of 500 and 800 MHz (red and blue points, respectively), 25°C, along with global fits of the data to a model of two-site chemical exchange (solid lines).

Structure Determination Protocol.

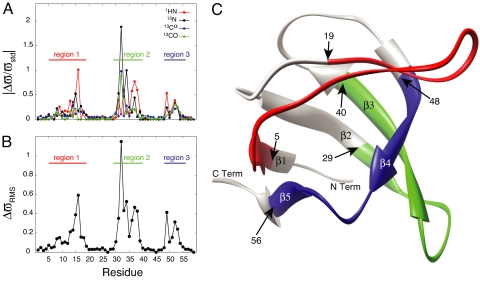

As described above relaxation dispersion data are sensitive to changes in chemical shifts between exchanging states. Fig. 2A plots the changes in 1HN, 15N, 13Cα and 13CO chemical shifts between free (“ground”) and bound (“excited”) conformations of the Abp1p SH3 domain as a function of residue. Values of Δϖ have been normalized by nucleus-specific values, ϖstd, corresponding to the range of shift values (1 standard deviation) that are observed in a database of protein chemical shifts (www.bmrb.wisc.edu). Non-zero values of Δϖ cannot be interpreted as evidence for a change in structure at the site of the measurement because fluctuating magnetic fields due to proximal mobile spins can account for such changes in Δϖ. However, if values of Δϖ ≈ 0 are obtained for all four measured chemical shifts, then this is a strong indicator of little structural change between ground and excited states. Fig. 2B plots

as a function of residue, where the summation is over the n = 4 measured chemical shift differences illustrated in Fig. 2A; for a few residues, n < 4 in cases where dispersion profiles could not be quantified. It is clear that there are continuous segments of polypeptide chain where there are essentially no changes in chemical shifts between states, ΔϖRMS < 0.05, whereas other portions of the structure, denoted by regions 1, 2 and 3 in Fig. 2B and corresponding to approximately twothirds of the protein sequence, show more pronounced changes. Fig. 2C plots these 3 regions on the x-ray-derived structure of the apo form of the Abp1p SH3 domain (1jo8) (22); they were allowed to vary in a restrained molecular dynamics protocol that calculates structures of the invisible, bound state while the remaining residues (gray) were constrained to the same conformation as in the ground, free form of the domain throughout the calculations (see below). It is clear that the choice of ΔϖRMS < 0.05 is somewhat arbitrary; larger values lead to improved rates of convergence of structures because more residues are constrained. However, because the structures presented in this work are the first calculated for an excited state from relaxation dispersion data exclusively, we favor the low value used here as it provides a particularly stringent test of the experimental restraints.

Fig. 2.

|

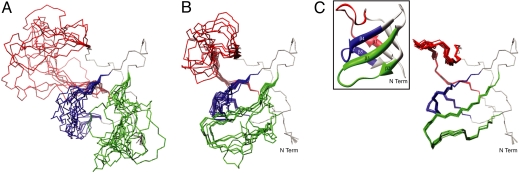

Structure calculations were performed using the Xplor-NIH software package (23) and made use of 1HN-15N, 1Hε1-15Nε1 (Trp), 1Hα-13Cα, and 1HN-13CO RDC and 13CO RCSA restraints as well as (φ, ψ) torsion angle restraints that were obtained from 1HN, 15N, 13Cα and 13CO chemical shifts using the program TALOS (24) (all dihedral restraints obtained in this way are reported in Table S8). “Randomized” starting structures were generated from the x-ray coordinates of the apo form of the Abp1p SH3 domain (22) by high-temperature molecular dynamics in which residues within regions 1, 2, and 3 (denoted in red, green, and blue, respectively in Fig. 2C) were unconstrained, with all other regions of the molecule fixed to the x-ray structure. The 10 starting structures generated in this way are shown in Fig. 3A; average pairwise rmsd values for the backbone (N, Cα and CO) atoms in regions 1–3 are 4.6 ± 0.9 Å within this ensemble and 8.6 ± 1 Å between members of the ensemble and the x-ray structure, ensuring a wide variety of starting structural models that were not biased by the structure of the ground state (rmsd values calculated as described in the legend to Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Solution structure of the invisible, Ark1p-peptide bound conformation of the Abp1p SH3 domain. (A) Ensemble of 10 starting structures generated from high temperature molecular dynamics of the apo-Abp1p SH3 domain x-ray structure (22), as described in the text. Regions in gray are fixed to the x-ray structure, because ΔϖRMS ≈ 0. The pair-wise rmsd values of the backbone Cα, CO and N atoms of regions 1 (red), 2 (blue) and 3 (green) are 5.8 ± 1.6, 3.7 ± 1.0, 2.6 ± 0.7 Å, respectively (10.4 ± 1.6, 8.6 ± 1.2, 3.8 ± 0.6 Å with respect to the apo-Abp1p1 SH3 domain x-ray coordinates). (B) Ensemble of the 10 lowest energy structures generated using (φ, ψ) restraints exclusively, as described in the text. Pair-wise rmsd values of regions 1, 2 and 3 are 3.1 ± 1.4, 3.8 ± 2.4 and 1.2 ± 0.7 Å, respectively. (C) As in B, but including restraints from residual anisotropic interactions as measured using a single alignment media (Pf1). The rmsd values of 0.39 ± 0.12, 0.30 ± 0.11 and 0.20 ± 0.06 Å are calculated for regions 1–3 (0.47 ± 0.10, 0.76 ± 0.14 and 0.53 ± 0.07 Å to the reference structure of the bound form). Inset, ribbon diagram of the apo-Abp1p SH3 domain x-ray structure; all conformers in the figure are in the same orientation. All of the rmsd values reported are calculated by superimposing the “fixed” regions (gray in Fig. 2C); the fixed regions are not included in the computation.

Initially we were interested in evaluating the quality of structures that could be generated by using only the (φ, ψ) restraints from TALOS based on the chemical shifts that were obtained for the excited state from relaxation dispersion measurements. Thus, the 10 starting structures generated above (with regions 1–3 randomized, Fig. 3A) were subsequently refined by inclusion of only (φ, ψ) restraints using a standard torsion angle molecular dynamics (TAMD) protocol (23). Fig. 3B shows an ensemble of the 10 lowest energy structures of the invisible, excited state generated in this manner. The structural quality is marginal at best, with a pairwise rmsd value of 3.2 ± 1.2 Å. It is clear that additional restraints are required, and these are provided in the form of RDCs and RCSAs, as described below.

Initial structure calculations that included both torsion angle and anisotropic restraints (for regions 1–3 in Fig. 2C) had a poor convergence rate, however, and a two-stage protocol with improved efficiency was therefore developed. In stage 1, initial starting structures were generated from the conformers in Fig. 3A that contained only one of regions 1–3, with the other two removed. Following a TAMD protocol [with (φ, ψ) and anisotropic restraints], described in detail in SI Text, mean values of (φ, ψ) dihedral angles averaged over the resulting 10 lowest energy structures were calculated and subsequently used as backbone angle restraints for every residue in the segment of interest (the red, green, or blue regions in Fig. 2C) in stage 2 of the protocol (see below). The process was repeated for each of the additional two segments to generate a near-complete list of (φ, ψ) restraints; note that before this set of computations torsion angle restraints were available for only ≈60% of the variable residues from chemical shift data/TALOS. Of interest, both the mean and the distribution of (φ, ψ) values change very little whether 10 or 20 structures are used, with differences in the mean less than 1° on average (6° maximum). In stage 2, TAMD calculations were repeated on the intact molecule using (φ, ψ) restraints obtained for all residues in regions 1–3 from the previous dynamics runs and the full set of RDC and RCSA values. Here, convergence was much higher than initial calculations on the intact molecule because torsion angle restraints for almost every residue in regions 1–3 were available (restraints were not included if their standard deviations were >50°). Fig. 3C shows an ensemble of the 10 lowest energy structures of the invisible state obtained with both (φ, ψ) and anisotropic restraints. It is clear that inclusion of RDC and RCSA values leads to significant improvements in the structures (compare Fig. 3 B and C) with pairwide rmsd values decreasing from 3.2 ± 1.2 (B) to 0.33 ± 0.08 Å (C). Fig. S2 plots the total energy of each structure versus the rmsd to the lowest energy structure, showing that a large number of structures converge using the protocol described above.

Validation of Structures.

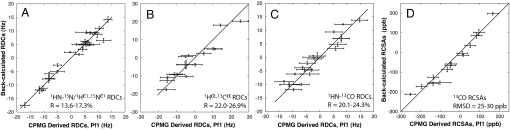

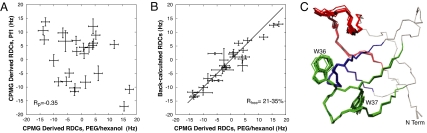

Fig. 4 shows a comparison between experimental RDC and RCSA values and those predicted from the 10 lowest energy structures. The goodness of fit to the RDC data was evaluated by the R factor defined by Clore et al. (25), with values between 0.14 and 0.27 obtained. Low values of R, such as those generated here, indicate that the experimental data are well fit by the structural models. However, to get additional verification that the models are correct, we recorded 1H-15N RDC values in the excited state using a different alignment media. Fig. 5A shows a comparison of 1HN-15N RDC values obtained with alignment in Pf1 phage particles (26) and in a medium composed of PEG/hexanol (27); the correlation between the data sets is poor (Pearson correlation coefficient of −0.35), consistent with very different molecular alignment frames. The PEG/hexanol data do, however, fit well to values predicted on the basis of the calculated structures of the invisible, ligand-bound state as shown in Fig. 5B, where the correlation between experimental and calculated RDC values is presented (Rfree = 0.21–0.35 for the 10 lowest energy structures).

Fig. 4.

Goodness of fit between experimental and calculated anisotropic restraints. Correlation between calculated (y axis) and experimentally derived (x axis) 1HN-15N (A), 1Hα-13Cα (B), 1HN-13CO (C) RDC and 13CO chemical shift anisotropy (D) restraints for the 10 lowest energy structures of Fig. 3C, along with the range of calculated R values (A–C based on the 10 structures), as defined by Clore et al. (25). Average R values changed by less than 1% when the number of included structures was increased to 20. In D, the rmsd between the experimental and predicted RCSA values is given.

Fig. 5.

Cross-validation of the calculated structure of the invisible, Ark1p-bound form of the Abp1p SH3 domain. (A) Correlation between 1H-15N RDCs of the invisible, bound state measured in Pf1 phage (y axis) and PEG/hexanol (x axis) alignment media. A poor correlation is obtained indicating that the molecular alignment frames in each medium are significantly different (Pearson's correlation coefficient of −0.35). (B) Correlation plot of 1H-15N RDCs measured on an aligned system in PEG/hexanol vs. values predicted based on the structures of Fig. 3C that were not calculated using these restraints. Rfree values ranged from 21% to 35% for the 10 lowest energy structures. (C) Ten lowest energy structures calculated using (φ, ψ) and residual anisotropic restraints obtained from two alignment media (Pf1 phage and PEG/hexanol; only 1H-15N RDCs were measured in PEG/hexanol). The rmsd values of 0.27 ± 0.12, 0.21 ± 0.07, and 0.17 ± 0.07 Å are calculated for regions 1–3, respectively (0.46 ± 0.07, 0.32 ± 0.03, 0.48 ± 0.07 Å to the reference structure of the bound form, determined as described in the legend to Fig. 3).

After the 1H-15N RDC values recorded in the second alignment medium were used to cross-validate the ensemble of SH3 domain structures corresponding to the invisible, ligand-bound conformation, they were also included in the structure determination protocol, leading to further improvements in the quality of the structures (compare Fig. 3C and Fig. 5C). For example, pairwise rmsd values of 0.39 ± 0.12, 0.30 ± 0.11, and 0.20 ± 0.06 Å are calculated for regions 1–3 of the set of 10 lowest energy structures determined using anisotropic restraints from a single media, whereas the corresponding values decrease to 0.27 ± 0.12, 0.21 ± 0.07, and 0.17 ± 0.07 Å when refinements are based on restraints from both alignment media. In addition, the orientations of the Trp 36 and Trp 37 side-chains become better defined when Hε1-Nε1 RDCs are included from both alignment media.

A high-resolution structure of the Ark1p ligand-bound form of the Abp1p SH3 domain is not available presently to compare with the calculated structures of the invisible bound state produced here. With this in mind, we have generated a structural model of the bound conformation using the protocol described by Chou et al. (28), starting from the x-ray structure of the apo-state and refining with 1HN-15N, 1Hα-13Cα and 1HN-13CO RDC restraints measured directly on the fully bound form of the protein. An average pairwise rmsd of 0.43 ± 0.04 Å is obtained between the backbone atoms of the 10 lowest energy excited state structures (calculated from anisotropic restraints measured from relaxation dispersion experiments conducted in both alignment media) and the structural model of the bound conformation derived from the apo form of the x-ray structure (the corresponding value is 0.60 ± 0.09 Å when anisotropic restraints from only one medium are used). It is clear that the restraints obtained from relaxation dispersion methods are, at least in this case, sufficient to define the backbone protein fold of the invisible state.

We have also compared the structures of the invisible, bound state derived here with the x-ray structure of the apo SH3 domain (1jo8) (22). The average pairwise rmsd is small (<0.4 Å for regions 1–3), as expected based on the small chemical shift differences measured (Fig. 1). It is important to note that the structure-determination approach described here would work equally well in cases where large differences in conformation exist between the states. Indeed, regions 1–3 of the starting structures were ≈9 Å from the apo x-ray structure (Fig. 3A) (and also from the bound state), so that little bias is introduced from the starting conformers.

In summary, we have provided a detailed structural characterization of an invisible, excited state conformer, based on structural restraints measured exclusively by means of relaxation dispersion NMR methods. It is anticipated that additional relaxation dispersion methodology can be developed extending to other interactions, such as those in side-chains of proteins, leading to further improvements in the quality of obtainable structures.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation.

The preparation of samples for the measurement of relaxation dispersion profiles from which 15N, 1HN, 13Cα, and 13CO chemicals shifts and 1HN-15N, 1Hα-13Cα, 1HN-13CO RDCs and 13CO RCSA values are measured has been described earlier (6, 7, 9, 10, 20). Briefly, alignment was achieved using Pf1 phage (≈25 mg/ml, 25 Hz D2O splitting; 15 mg/ml, 15 Hz splitting; 45 mg/ml, 55 Hz splitting) (ALSA Biotech) for measurement of 1HN-15N RDCs; 1Hα-13Cα RDCs; 1HN-13CO RDCs and 13CO RCSAs or PEG (C12E5)/hexanol media (21 Hz D2O splitting). All experiments were carried out on suitably labeled samples of ≈1.5 mM concentration in protein dissolved in 50 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM NaN3 pH 7.0 buffer, 25°C.

NMR Spectroscopy and Data Analysis.

Values of 15N, 13Cα, and 13CO chemical shifts of the invisible, bound state of the Abp1p SH3 domain have been derived from relaxation dispersion CPMG-based experiments, as reported previously (6). Only |Δω| 1HN values were available [from an analysis of 1HN single-quantum (SQ) CPMG relaxation dispersion profiles]. The signs of 1HN Δω values have been determined by fits of 1HN-15N zero- and double-quantum relaxation dispersion profiles measured at 500 and 800 MHz on an unaligned sample, using the sign information of 15N Δω values, as discussed previously (29).

1HN-15N, 1Hα-13Cα, and 1HN-13CO RDC and 13CO RCSA values of the invisible state measured in Pf1 phage used in this study have been reported previously (7, 9, 10). 1HN-15N RDCs for the invisible bound state aligned with PEG/hexanol media were determined by recording constant-time 15N TROSY, anti-TROSY, and 1H decoupled (CW) CPMG experiments (7) at 1H frequencies of 500 and 800 MHz. The constant-time delay was set to 30 ms, and data were recorded at 18 CPMG frequencies between 33.33 and 1,000 Hz. RDCs were then extracted from simultaneous fits of the resulting relaxation dispersion profiles by using in-house written software (available upon request) and following protocols described in detail previously (7, 10).

Structure Determination Protocol.

Structures were calculated by using Xplor-NIH software following well established protocols (23). Details are provided in SI Text, along with a flow chart (Fig. S3) that summarizes the steps involved in the process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

This work was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (to L.E.K.). P.V. and D.F.H. are the recipients of postdoctoral fellowships from the CIHR Training Grant on Protein Folding in Health and Disease and the CIHR, respectively. L.E.K. holds a Canada Research Chair in Biochemistry.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates, chemical shifts, and restraints used for the structure calculations are available from the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2k3b).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0804221105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Karplus M, Kuriyan J. Molecular dynamics and protein function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6679–6685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408930102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henzler-Wildman K, Kern D. Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature. 2007;450:964–972. doi: 10.1038/nature06522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer AG, Kroenke CD, Loria JP. NMR methods for quantifying microsecond-to-millisecond motions in biological macromolecules. Methods Enzymol. 2001;339:204–238. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)39315-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korzhnev DM, et al. Low-populated folding intermediates of Fyn SH3 characterized by relaxation dispersion NMR. Nature. 2004;430:586–590. doi: 10.1038/nature02655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skrynnikov NR, Dahlquist FW, Kay LE. Reconstructing NMR spectra of “invisible” excited protein states using HSQC and HMQC experiments. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12352–12360. doi: 10.1021/ja0207089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen DF, Vallurupalli P, Lundstrom P, Neudecker P, Kay LE. Probing chemical shifts of invisible states of proteins with relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy: How well can we do? J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2667–2675. doi: 10.1021/ja078337p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vallurupalli P, Hansen DF, Stollar EJ, Meirovitch E, Kay LE. Measurement of bond vector orientations in invisible excited states of proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18473–18477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708296104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Igumenova TI, Brath U, Akke M, Palmer AG., 3rd Characterization of chemical exchange using residual dipolar coupling. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13396–13397. doi: 10.1021/ja0761636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallurupalli P, Hansen DF, Kay LE. Probing structure in invisible protein states with anisotropic NMR chemical shifts. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2734–2735. doi: 10.1021/ja710817g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen DF, Vallurupalli P, Kay LE. Quantifying two-bond 1HN-13CO and one-bond 1Ha-13Ca dipolar couplings of invisible protein states by spin-state selective relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8397–8405. doi: 10.1021/ja801005n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wishart DS, Sykes BD. Chemical shifts as a tool for structure determination. Methods Enzymol. 1994;239:363–392. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)39014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spera S, Bax A. Emperical correlation between protein backbone conformation and c-alfa and c-beta c13 nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5490–5492. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cavalli A, Salvatella X, Dobson CM, Vendruscolo M. Protein structure determination from NMR chemical shifts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9615–9620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen Y, et al. Consistent blind protein structure generation from NMR chemical shift data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:4685–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800256105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prestegard JH, Mayer KL, Valafar H, Benison GC. Determination of protein backbone structures from residual dipolar couplings. Methods Enzymol. 2005;394:175–209. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)94007-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bax A. Weak alignment offers new NMR opportunities to study protein structure and dynamics. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1–16. doi: 10.1110/ps.0233303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haynes J, et al. The biologically relevant targets and binding affinity requirements for the function of the yeast actin-binding protein 1 SRC-homology 3 domain vary with genetic context. Genetics. 2007;176:193–208. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.070300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drubin DG, Mulholland J, Zhu ZM, Botstein D. Homology of a yeast actin-binding protein to signal transduction proteins and myosin-I. Nature. 1990;343:288–290. doi: 10.1038/343288a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loria JP, Rance M, Palmer AG. A relaxation compensated CPMG sequence for characterizing chemical exchange. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:2331–2332. doi: 10.1023/a:1008355631073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen DF, Vallurupalli P, Kay LE. An improved 15N relaxation dispersion experiment for the measurement of millisecond time-scale dynamics in proteins. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:5898–5904. doi: 10.1021/jp074793o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishima R, Torchia D. Extending the range of amide proton relaxation dispersion experiments in proteins using a constant-time relaxation-compensated CPMG approach. J Biomol NMR. 2003;25:243–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1022851228405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fazi B, et al. Unusual binding properties of the SH3 domain of the yeast actin-binding protein Abp1: Structural and functional analysis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5290–5298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Clore GM. Using Xplor-NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2006;48:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cornilescu G, Delaglio F, Bax A. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J Biomol NMR. 1999;13:289–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1008392405740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clore GM, Starich MR, Bewley CA, Cai M, Kuszewski J. Impact of residual dipolar couplings on the accuracy of NMR structures determined from a minimal number of NOE restraints. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:6513–6514. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen MR, Mueller L, Pardi A. Tunable alignment of macromolecules by filamentous phage yields dipolar coupling interactions. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruckert M, Otting G. Alignment of biological macromolecules in novel nonionic liquid crystalline media for NMR experiments. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7793–7797. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chou JJ, Li S, Bax A. Study of conformational rearrangement and refinement of structural homology models by the use of heteronuclear dipolar couplings. J Biomol NMR. 2000;18:217–227. doi: 10.1023/a:1026563923774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korzhnev DM, Neudecker P, Mittermaier A, Orekhov VY, Kay LE. Multiple-site exchange in proteins studied with a suite of six NMR relaxation dispersion experiments: An application to the folding of a Fyn SH3 domain mutant. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15602–15611. doi: 10.1021/ja054550e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.