Abstract

RNA editing in land plant organelles is a process primarily involving the conversion of cytidine to uridine in pre-mRNAs. The process is required for gene expression in plant organelles, because this conversion alters the encoded amino acid residues and improves the sequence identity to homologous proteins. A recent study uncovered that proteins encoded in the nuclear genome are essential for editing site recognition in chloroplasts; the mechanisms by which this recognition occurs remain unclear. To understand these mechanisms, we determined the genomic and cDNA sequences of moss Takakia lepidozioides chloroplast genes, then computationally analyzed the sequences within −30 to +10 nucleotides of RNA editing sites (neighbor sequences) likely to be recognized by trans-factors. As the T. lepidozioides chloroplast has many RNA editing sites, the analysis of these sequences provides a unique opportunity to perform statistical analyses of chloroplast RNA editing sites. We divided the 302 obtained neighbor sequences into eight groups based on sequence similarity to identify group-specific patterns. The patterns were then applied to predict novel RNA editing sites in T. lepidozioides transcripts; ∼60% of these predicted sites are true editing sites. The success of this prediction algorithm suggests that the obtained patterns are indicative of key sites recognized by trans-factors around editing sites of T. lepidozioides chloroplast genes.

Key words: bioinformatics, chloroplast, computational biology, plant organelle, singlet and doublet propensities, Takakia lepidozioides

1. Introduction

Pre-mRNAs from land plant organelles frequently undergo single nucleotide conversions of cytidine residues to uridine.1 This process, called RNA editing, was first discovered in wheat mitochondrion mRNA encoding coxII2 and maize chloroplast mRNA encoding rpl2.3 Many reports of RNA editing sites followed these discoveries.4–8 In Arabidopsis thaliana, 441 nucleotides within mitochondrial mRNAs have been determined to be edited,9 and there are at least 26 edited sites in chloroplast transcripts from black pine.10 The majority of these RNA edited sites are found in protein coding regions, typically within the first or second letter of a codon; therefore, RNA editing usually alters the amino-acid sequence of the encoded protein in plant organelles. Such alterations in amino-acid sequence frequently improve sequence identity to other homologous proteins, suggesting that RNA editing is a process to repair ‘damaged’ codons.1 The editing process, therefore, must be highly specific.11

The editing process is divided into two distinct steps: site recognition and nucleotide modification. The modification process occurs via deamination of the base,12,13 although the factor(s) mediating this process in plant organelles have not yet been identified. The recognition process for both mitochondrial and chloroplast RNA editing has remained a mystery. Cis-elements upstream of the editing sites have been identified in multiple mRNAs.14–20 Although rearrangements of nucleotides downstream of one of the editing sites in the maize rps12 mitochondrial mRNA did not affect the editing, similar rearrangements at another editing site within this sequence altered editing,11 suggesting that each editing site has different cis-elements at different positions. Miyamoto et al.21 identified three distinct trans-factor proteins that bound cis-elements at three different editing sites, suggesting that each RNA editing site is recognized by unique proteins. In vitro assays examining RNA editing in tobacco chloroplasts identified an RNA editing site in ndhB that requires a short upstream region for proper editing and one in ndhF that requires both upstream and downstream sequences surrounding the editing site and an additional 5′ distal sequence.22 The cis-elements found by those experiments were typically located within 15–30 nucleotides of the 5′ nucleotides of the editing sites.21,23 Several reports indicated nucleotide sequence similarity upstream of several different RNA editing sites,24,25 but there was no obvious consensus sequence motif for all the upstream sequences.9,26 Recently, a genetic approach identified CRR4 and CRR21, members of the pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins, as essential trans-factors in chloroplasts for RNA editing site recognition.27–29 CRR4 specifically bound the 25 nucleotides upstream and 10 nucleotides downstream of the first editing site in ndhD mRNA.28 The length of the mRNA segment protected by CRR4 binding is similar to the length suggested to be necessary for editing site recognition. Arabidopsis thaliana has a huge number of members of the PPR protein family,30 proteins suggested to function in organelle biogenesis.31 Current advances in understanding the mechanisms of RNA editing in chloroplasts, which likely apply to mitochondrion as well, can be summarized as follows: (i) PPR proteins recognize several RNA editing sites, (ii) PPR proteins bind a region spanning from ∼30 nucleotides upstream to 10 nucleotides downstream of the editing site and (iii) the same protein may also convert the target cytidine to uridine.32

Further understanding of RNA editing site recognition mechanisms in chloroplast transcripts can be achieved by computational analyses of nucleotide sequences aimed at identifying target nucleotides upstream and downstream of editing sites. For this type of analyses, multiple RNA editing sites with non-homologous nucleotide sequences are required. As the nucleotide sequences in homologous sites of homologous sequences are evolutionarily related, this conservation hampers the detection of functionally important nucleotide sequences essential in RNA editing site recognition. Although substantial known non-homologous RNA editing sites exist in mitochondrial mRNAs to allow these statistical calculations to be performed,33–36 those methods have not yet been applied to chloroplast RNA editing sites from a single species due to the paucity of known RNA editing sites. The maximum number of known C-to-U RNA editing sites in a chloroplast was 44 in the moth orchid Phalaenopsis aphrodite.37

Transcripts from chloroplasts of the moss Takakia lepidozioides are thought to contain a large number of RNA editing sites,38 which may provide the opportunity to perform classification and motif analyses of RNA editing site surrounding sequences (−30 to +10 nucleotide). Here, we sequenced the genomic and mRNA transcripts from T. lepidozioides. We then performed statistical analyses of RNA editing site sequences and identified statistically significant patterns in the sequences. We used these patterns to predict novel RNA editing sites and experimentally verified these predictions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Amplification of plastid DNA fragments and analysis of cDNA

We extracted total cellular DNA from T. lepidozioides S. Hatt. & Inoue (Takakiaceae, Bryophyta) as described previously.38 We used the resulting sequences as a template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using appropriate primers (Supplementary Table S1) with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min and extension at 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. Amplified DNA fragments were cloned into pGEM-T Easy plasmids (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). RNA extraction, first-strand cDNA synthesis and amplification of cDNA were performed as described.39 cDNA was amplified by PCR using appropriate primers (Supplementary Table S1) and subjected to direct sequencing. cDNAs encoding accD, ndhC, ndhJ, petA, petL, petG, psaJ, rpl33, rps18, rpl20, 5′-rps12 and clpP were cloned into pGEM-T Easy plasmids; at least two independent cDNA clones were sequenced for each cDNA.

2.2. DNA sequencing and identification of RNA editing sites

DNA sequencing was performed as described39 using M13 universal primers and internal sequence primers designed from the sequences determined in this study (Supplementary Table S1). RNA editing sites were analyzed by comparing each cDNA sequence to that of genomic DNA. Nucleotide sequence data were deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database under the accession numbers AB299142, AB367138 (plastid DNA), AB299143–AB299154 and AB367139–AB367144 (cDNA).

2.3. Classification of neighbor nucleotide sequences of RNA editing sites

We collected sequences from each RNA editing site from 30 nucleotides upstream to 10 nucleotides downstream (41 nucleotides in total), which we named the neighbor sequence. After aligning these neighbor sequences without any gaps, we calculated the sequence identities. We used ungapped alignments here to avoid any dependency of the results on the value of gap penalty. Using dissimilarity, defined as 1.0-identity, as a distance among those sequences, we built a dendrogram using the neighbor-joining method.40 The dendrogram was expected to show only those sequence similarities derived from similarities in the recognition mechanism. On the basis of the obtained dendrograms, we divided the neighbor sequences into several groups at the first major branches from the root.

2.4. Singlet and doublet propensities for each group

Here, we used the method of deducing functionally and structurally important residue position pairs from sets of functionally related sequences, originally proposed by Yura et al.41 The method used to calculate the propensities for residue positions was based on Kim et al.42 As we used cDNA to treat the nucleotide data, uridine is hereafter denoted as thymine.

The singlet propensity for each group was calculated as follows. In a group with N nucleotide sequences, the number of a certain nucleotide x (x = 1, 2, 3 or 4, which corresponds to A, T, G or C, respectively) at position i (i = −30, −29, −28, … , +10) was denoted as nix. The frequency of finding nucleotide x at position i (fix) was defined as

|

1 |

The informative value was the deviation of fix from the expected frequency of nucleotide x at position i, which was calculated as

|

2 |

We assumed that the expected frequency did not depend on position i and defined the singlet propensity of nucleotide x at position i (Pix) as

| 3 |

A singlet propensity Pix > 1.0 indicated that nucleotide x was favored at position i, whereas values <1.0 implied the nucleotide was disfavored.

The doublet propensity indicates the preference for a pair of nucleotides at two different, but linked, positions within the neighbor sequence. In a group with N nucleotide sequences, the number of the pair of nucleotides x and y (x, y = 1, 2, 3, 4) at positions i and j (i, j = −30, −29, −28, … , +10) was denoted as ni,jx,y. The frequency of finding a pair of nucleotides x and y at positions i and j, respectively, was

|

4 |

The informative value was the deviation of fi,jx,y from the expected frequency, which was calculated for nucleotide x at position i with nucleotide y at position j as

| 5 |

We defined the doublet propensity as

|

6 |

The doublet propensity Pi,jx,y represents the coupling constant for nucleotides x and y at positions i and j, respectively. When Pi,jx,y was >1.0, the pair of nucleotides x and y was favored, whereas values <1.0 indicated that this pairing was disfavored. When Pi,jx,y was equal to 1.0, no preference for a pair of nucleotides x and y at positions i and j exists.

When Equations (1)–(6) were applied to the neighbor sequences of RNA editing sites from T. lepidozioides chloroplasts, the paucity of events in the count of nix and ni,jx,y hampered our ability to obtain valid values for Pix and Pi,jx,y. To minimize possible statistical error caused by a paucity of data, we employed pseudo-counts for nix and ni,jx,y.43 These pseudo-counts should reflect the a priori expectations of the occurrence of the nucleotides x and y; we used a background frequency to define these a priori expectations. Therefore, in the real-data calculations, nix was given by nix + bxN, and ni,jx,y was given by ni,jx,y + bi,jx,yN.

The limited number of data reduced the statistical reliability of the calculated propensities. To estimate the standard deviation of Pix and Pi,jx,y, we used a bootstrap procedure in which we constructed bootstrap datasets based on 1000 resamplings, then calculated bootstrap replications of Pix and Pi,jx,y. We estimated standard deviations from these replications. We assessed the reliability of Pi,jx,y by the 5% significance Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to examine if the values derived from the replications followed a Gaussian distribution and by the 15% bootstrap percentile method to test if the values obtained using the entire data set were within a 15% deviation of the average values calculated from the replication.42

2.5. Application of propensities to predicting new RNA editing sites from a region covering petL to clpP

The propensity values Pix and Pi,jx,y represent the odds of a certain nucleotide sequence being present in the RNA editing site over a random sequence for nucleotides x and y at positions i and j, respectively. From the values, it is possible to calculate the odds of a given nucleotide sequence being an RNA editing site neighbor sequence over a random sequence by

|

7 |

where A is a given 41-nucleotide sequence in which the 31st residue was a cytidine and Ai is the type of nucleotide at the ith position. In the real calculations, we used the logarithmic value, defining the score for sequence A as

|

8 |

In the calculation, only statistically significant log2Pi,jx,y values were used; non-significant log2 Pi,jx,y values were set to 0. Pix and Pi,jx,y values for i, j = 0, candidate editing sites, were not used throughout these calculations, because position 0 was cytidine by definition. Greater values of SA indicate a higher likelihood that the 31st position of the sequence is edited. We determined the threshold values for SA based on the prediction applied to sequences used to obtain Pix and Pi,jx,y.

We applied the prediction to newly sequenced transcripts from T. lepidozioides chloroplasts and experimentally verified in a blind test if the predicted RNA editing sites were actually edited.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Identification of RNA editing sites in T. lepidozioides chloroplasts

We previously identified 132 RNA editing sites in transcripts from the psbB operon and rpoA gene38 as well as one site in the tRNALeu anticodon39 of T. lepidozioides chloroplasts. To identify additional RNA editing sites, we determined the nucleotide sequences of a 27 kb plastid DNA region from rps4 to psbE (Fig. 1) and the cognate cDNAs. To identify RNA editing sites in rbcL, we compared the cDNA sequences in the database (AB427089) to the sequenced plastid DNA. This comparison of plastid DNA and cDNA sequences identified 170 novel RNA editing sites in a region between rps4 and psbE, including one site in the tRNALeu anticodon (Supplementary Table S2). All sites contained C-to-U conversions. In total, there were 302 RNA editing sites, 132 previously identified and 170 newly recognized, available for computational analysis.

Figure 1.

Gene arrangement of the region spanning rps4 to rps11 in the T. lepidozioides plastid genome. The filled boxes indicate the translated regions for each gene, and the open boxes represent introns. The genes over the thick horizontal bar were transcribed from left to right, whereas those below the bar were transcribed in the opposite direction. Fragments 1–19, shown under the bar, were amplified by PCR. Sequences for the dotted fragments under the bar were taken from Genbank/EMBL/DDBJ.

3.2. Classification of 302 nucleotide sequences with RNA editing site

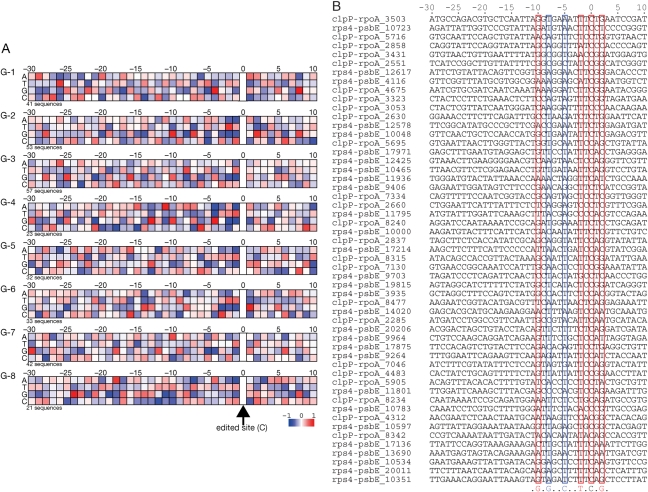

We classified the 302 41-nucleotide sequences with the RNA editing site at the 31st position (neighbor sequences) from T. lepidozioides chloroplast (Fig. 2) in a dendrogram based on sequence identity. Grouping of the sequences, visualized by background color, was based on branching of the dendrogram. The threshold for grouping of the sequences was set at the second branching point of the dendrogram from the root. The 302 initial sequences were divided into eight groups, named G-1 to G-8. The largest group (G-1 plus G-2) was further divided into two groups, as the sequence identities within this group were very low. The average number of sequences in each group was ∼38, ranging from 21 to 57. Within each group, the sequences had a sequence identity with the other sequences in that group of at least 40%.

Figure 2.

Classification of neighbor sequences for RNA editing sites. We drew the classification dendrogram for 41-nt sequences based on sequence identity. The sequences were grouped at the second or third branching points. Each group, named from G-1 to G-8, was depicted by a background color. Each sequence was named based on the sequenced region and number of nucleotides. Note that the figure does not express the phylogenetic relation of the sequences.

Previous reports have been unable to identify common motifs in the neighbor sequences of RNA editing sites. The dendrogram in Fig. 2 demonstrates that although none of the neighbor sequences for RNA editing sites are similar, the sequences can be grouped into at least eight different patterns. These groups likely correspond to the neighbor sequence of RNA editing sites recognized by different trans-factors. Unique or similar trans-factors may recognize the neighbor sequences of each group; the classification derived from the dendrogram suggests that each trans-factor recognizes different neighbor sequences. To investigate this possibility, we analyzed the singlet and doublet propensities for each group and compared similarities in propensities within a group and differences between groups.

3.3. Singlet and doublet propensities of each group

Singlet propensities for each group, shown in Fig. 3A, are expressed as a preference for individual nucleotides at each position in the neighbor sequence color-coded from red to blue on a log2 scale, with the exception of the RNA editing site (position 0). When statistically significant support could not be obtained for the singlet value of a nucleotide at that site, the log2 scaled singlet value was set as 0 and colored white. A deep red box indicates that the nucleotide appeared at that position twice as frequently as expected from a random distribution; a deep blue box indicates that the nucleotide appeared half as frequently as expected.

Figure 3.

(A) Singlet propensities of eight groups at each position for every nucleotide. The preference was color-coded from red to blue on a log2 scale, with the exception of the RNA editing site (position 0). When the value was not statistically significant, the singlet value was set to 0 and colored as white. The number of sequences in each group is noted at the bottom of each diagram. (B) All 53 neighbor sequences in group G-2. On the basis of this alignment, we calculated the singlet propensities for G-2 in A. Strong tendencies for specific nucleotides, found in A, at positions −10, −8, −5, −2 and +2 as well as the RNA editing site are boxed. At positions −10 and +2, G is favored, whereas T is favored at −2. At −8, G is avoided, and at −5, C is avoided. C at 0 is edited to U.

Throughout the eight groups, several characteristics repeatedly observed from the singlet propensity values. At position −1, purine nucleotides were strongly avoided (deep blue) in all groups with favoring of pyrimidines, especially T.1,23,44 At position 1, C is unfavorable.1,23 With these two exceptions, we could not identify characteristics common to all the groups. Each group, however, has unique characteristics. In G-1, T at −26 and G at −4 and +8 were strongly favored, with G at −17, C at −14 and G at −5 being strongly disfavored. In G-2, G at −10, T at −2 and G at +2 were favored, and G at −8, C at −5 and G at −2 were disfavored. In G-3, G was favored at −25, whereas C at −23 and G at −21 and −1 were disfavored. In G-4, G at −13, A at −11 and G at −4 were favored, and G at −21, C at −18, C at −5, A/T at −4, G at −2 and A/G at −1 were all disfavored. In G-5, A at −26, C at −13, A at −12, G at −5 and A/G at −1 were disfavored. In G-6, G was favored at +1, but disfavored at −25 and −3. In G-7, G was favored at −30, and C at −28 and G at −5 were disfavored. In G-8, G was favored at −24, and G at −19, C at −12, G at −11, A at −7 and A at −1 were disfavored. The skewed distribution of nucleotides at each position may work as a marker for each RNA editing site facilitating the binding of site recognition trans-factors. G-1, G-2 and G-6 had strong markers both upstream and downstream of the editing site. The markers for G-2 sequences were located close to the RNA editing site, whereas the markers for G-3 were located remotely from the RNA editing sites. In contrast, the markers for G-6 and G-7 were sparsely located throughout the neighbor sequence. Those markers for G-2 are shown in Fig. 3B. Strong singlet propensities demonstrate conservation, as shown in red boxes, but do not necessarily mean perfect conservation. At position −8, singlet propensities describe that G is disfavored, appearing only once in the alignment. At position −5, C also appeared only once.

RNA editing sites are frequently found at the second letter of a codon; the distribution of singlet propensity may reflect codon usage. If so, then the distribution pattern should have a period of three nucleotides in all places within the sequence. The patterns we observed, however, were free from periodicity and do not reflect the pattern of codons (Fig. 3A).

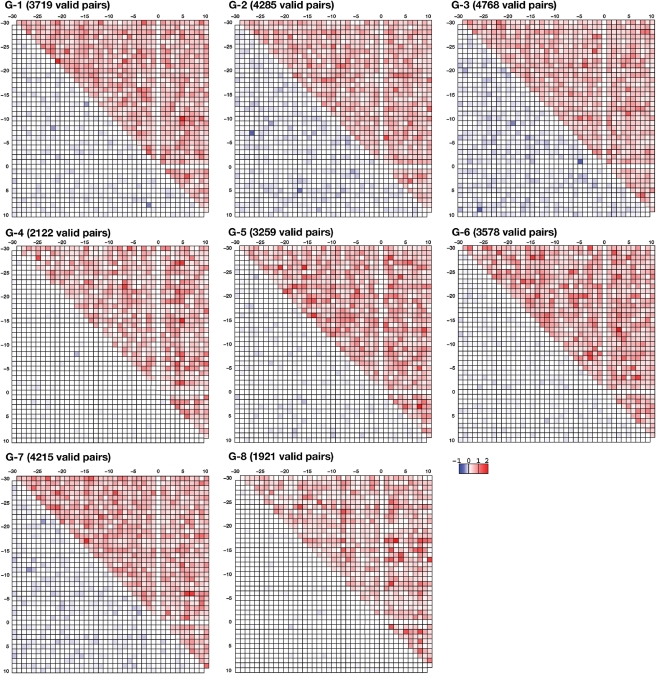

As seen for the singlet propensities, strong favoring or disfavoring typically described G and C, suggesting the existence of base pair patterns in the neighbor sequences of RNA editing sites. We therefore analyzed the doublet propensities for each group (Fig. 4). For each pair position, there are 16 (=4 × 4) possible combinations of nucleotides. When no statistical significance could be achieved for the doublet propensity value of a given nucleotide pair position, the log2 scaled doublet propensity value was set to 0. We calculated the square sum of all log2-scaled positive and negative doublet propensities, which are color-coded in the upper and lower triangular portions of the matrix, respectively. All of the groups had pairs of positions with high positive values; high negative values were rarely seen in any of the groups. High values in the far off-diagonal portions of the matrix suggested that there would be long-range correlations in the neighbor sequences of RNA editing sites. An intriguing point is that high positive values were found at pairs of nucleotides located upstream and downstream of the RNA editing site.

Figure 4.

The magnitude of doublet propensities for the eight groups in a log2 scale at each pair of positions. At each position pair, there are 16 possible combinations of nucleotides. Each combination has a value for doublet propensity. When the value was not statistically significant, it was set to 0. A square sum of positive doublet propensity at each position was color-coded from white to red in the upper triangular portion of the matrix. A square sum of negative doublet propensity at each position was color-coded from white to blue in the lower triangular portion of the matrix. The number of statistically significant values for doublet propensity is noted at the top of each matrix. The maximum number of doublet propensities should be 12 480 (=40 nt × 39 nt/2 × 16 pairs).

There were multiple specific nucleotide pairs with high doublet propensities (Table 1). For the 65 pairs with positions of log2 doublet propensities >0.9, the appearance of the nucleotide pair is ∼1.87 times more frequent than random occurrence. Of the 65 cases, only 18 cases (28%) exhibited a potential for Watson–Crick base pairing. The remaining 47 cases were unable to form Watson–Crick base pairs. Twenty-nine pairs (45%) were formed by the same nucleotide, suggesting that the pair preferences observed for that nucleotide is not due to base pairing, but to other unknown causes, possibly restrictions stemming from the interactions between these positions and a trans-factor.

Table 1.

Log2 doublet propensities >0.9 in each group

| Group | nt1* | nt2* | Pair* | Log2 doublet propensity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-1 | −30 | 9 | (C–G) | 0.94 | Watson–Crick pair |

| −25 | −24 | (G–G) | 0.92 | ||

| −22 | (G–G) | 1.02 | |||

| −22 | −21 | (C–C) | 1.01 | ||

| −10 | 5 | (G–C) | 0.92 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| 6 | (C–C) | 0.90 | |||

| −3 | −2 | (C–G) | 0.92 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| G-2 | −25 | −10 | (C–C) | 0.94 | |

| G-3 | −16 | 5 | (G–G) | 0.95 | |

| −10 | −5 | (C–C) | 0.91 | ||

| 6 | 8 | (G–G) | 0.93 | ||

| G-4 | −28 | −25 | (C–G) | 1.07 | Watson–Crick pair |

| −27 | 4 | (C–A) | 0.99 | ||

| 5 | (C–G) | 0.90 | Watson–Crick pair | ||

| −26 | 10 | (C–C) | 0.91 | ||

| −25 | −9 | (G–A) | 0.91 | ||

| −21 | −5 | (C–C) | 0.99 | ||

| −19 | 4 | (A–C) | 1.01 | ||

| 5 | (A–A) | 0.96 | |||

| −15 | 5 | (A–A) | 1.05 | ||

| −9 | 2 | (A–C) | 0.95 | ||

| −8 | 5 | (G–G) | 0.94 | ||

| −6 | 9 | (C–C) | 0.94 | ||

| −2 | 5 | (A–G) | 0.92 | ||

| 1 | 10 | (A–C) | 0.91 | ||

| 4 | 5 | (C–A) | 0.94 | ||

| G-5 | −27 | 5 | (C–G) | 0.90 | Watson–Crick pair |

| −26 | −16 | (C–C) | 0.98 | ||

| −24 | −16 | (G–G) | 0.98 | ||

| −22 | 2 | (A–C) | 1.01 | ||

| −21 | −20 | (C–C) | 0.96 | ||

| −16 | −14 | (C–C) | 1.05 | ||

| −15 | −8 | (C–G) | 0.90 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| −13 | −9 | (G–A) | 0.97 | ||

| 3 | 8 | (A–C) | 1.02 | ||

| G-6 | −29 | −13 | (G–G) | 0.90 | |

| −23 | −15 | (C–G) | 0.94 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| −22 | −6 | (C–G) | 0.93 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| −20 | −14 | (C–C) | 0.95 | ||

| −4 | (C–T) | 0.95 | |||

| −18 | 6 | (C–C) | 0.92 | ||

| −13 | 3 | (C–C) | 1.21 | ||

| −8 | −3 | (G–C) | 0.98 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| −3 | 4 | (C–A) | 0.96 | ||

| 7 | (C–A) | 1.06 | |||

| G-7 | −27 | −15 | (G–G) | 0.96 | |

| −9 | (C–G) | 0.95 | Watson–Crick pair | ||

| −18 | 9 | (C–G) | 0.92 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| G-8 | −27 | −6 | (A–C) | 0.97 | |

| −26 | −15 | (C–G) | 0.92 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| −24 | −17 | (G–C) | 0.92 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| 3 | (G–C) | 1.00 | Watson–Crick pair | ||

| −23 | −8 | (G–G) | 1.01 | ||

| −21 | −2 | (G–C) | 0.91 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| −17 | −16 | (G–C) | 0.93 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| 3 | (G–G) | 1.06 | |||

| 8 | (G–G) | 0.91 | |||

| −15 | 2 | (G–G) | 0.91 | ||

| −14 | 4 | (G–G) | 0.92 | ||

| −13 | 2 | (G–G) | 0.91 | ||

| 4 | (G–G) | 1.03 | |||

| −6 | 8 | (C–G) | 1.06 | Watson–Crick pair | |

| −2 | 8 | (T–G) | 0.97 | ||

| 2 | 5 | (C–A) | 0.93 | ||

| 8 | (G–G) | 1.02 | |||

*The statistically significant nucleotide pair in the parentheses appears at positions nt1 and nt2, respectively. We used the following rule of numbering nucleotide positions; position of the edited C was defined as 0, the nucleotides located on the 3′ side of the edited C had positive numbers and the nucleotides located on the 5′ side had negative numbers based on the distance in nucleotides from the C.

One focus in the investigation of the editing mechanism has been the role of RNA secondary structures in RNA editing site recognition. Yu et al.44 could not identify any RNA secondary structure motifs in the sequences surrounding mitochondrial RNA editing sites. Mulligan et al.11 confirmed these findings by demonstrating that the RNA editing sites in the mitochondria rps12 transcript did not have conserved RNA secondary structures. In contrast, Cummings and Myers33 analyzed RNA editing sites in mitochondria from three different species, discussing the possibility of secondary structure involvement in editing site recognition based on their free-energy calculations for RNA folding. Our study suggests that standard Watson–Crick pairs are not involved in the recognition processes.

3.4. Application of the propensities to prediction of RNA editing site

Although the prediction of RNA editing sites in mitochondrial transcripts has been attempted by several groups,33–36 prediction of RNA editing sites in chloroplast transcripts has not been tried, as there are significantly fewer known RNA editing sites in chloroplast transcripts.

One of the prediction methods that is widely used to identify RNA editing sites in chloroplast transcripts requires initial translation of the RNA into the amino-acid sequence followed by alignment of the homologous sequences. As RNA editing improves the amino-acid sequence identity of the edited sequence for homologous sequences, if a well-conserved position in the amino-acid sequence from the chloroplast gene is not conserved and C-to-U conversion within the codon can amend this difference, then the nucleotide is a candidate for an RNA editing site. This rule of thumb is practical, but cannot be used to detect silent RNA editing events that convert nucleotides at the third position in a codon and do not alter the encoded amino acid. In addition, a subset of editing events result in diversity of amino-acid sequences; this method also fails to identify this type of event.45 Furthermore, the method does not provide any understanding of the mechanism of RNA editing. Here, we apply the singlet and doublet propensities to neighbor sequences of RNA editing sites, as explained in Equation (8), to assess if this score can be a good predictor for the editing sites.

We applied singlet and doublet propensities of group G-2 to the whole cDNAs (open reading frames) for the rps4–psbE and clpP–rpoA sequences (Fig. 1). Coding sequences were read with a moving window 41-nucleotide in length. When the 31st position was a C, we calculated the score based on Equation (8) and plotted in the histogram (Fig. 5). Red regions in the figure indicate a count of edited sequences in G-2, whereas the cyan regions indicate a count of non-edited sequences. As we deduced the propensities from the edited sequences in G-2, it is trivial that the red regions were clustered in high-score regions. It is not trivial, however, that non-edited sequences were rarely found in high-score regions and that a peak was found in low-score regions. Similar distribution patterns were observed for the other groups (Supplementary Fig. S1). On the basis of this prediction using propensities of G-2, sequences with scores >130 were certainly neighbor sequences of RNA edited sites and sequences with score >100 were neighbor sequences with a likelihood of ∼60%. If the threshold for editing site prediction was set at score 100, then the predicted sites reflected truly edited sites with an accuracy of 60% (true positive), with 40% that were not edited (false-positive) and 15% of true RNA editing sites were missed (false-negative). Similar conclusions were found for the other groups (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 5.

Prediction score histogram for group G-2. The horizontal axis is the score in a bin of scale 10, and the vertical axis is the count of the prediction score in the bin. A red bar indicates the score for the edited C, and a bar in cyan indicates the score for a non-edited C. The prediction was performed for all transcripts (coding regions) between clpP and rpoA and between rps4 and psbE in the T. lepidozioides chloroplast genome. A bar for scores >70 has two numbers separated by a slash on the top. The number on the left is a count of the edited C, and the number on the right is the whole count in the bar.

The current prediction method measures the similarity of given nucleotide sequences with the propensities of the set of known sequences. In this way, the method is similar to homology search methods. Most conventional homology search methods, however, do not account for the similarity of residue pairs; this method attempted to address this issue by introducing doublet propensity into the score. When the prediction score was dissected into terms derived from the singlet and doublet propensities, singlet propensities contributed 4–6%, whereas doublet propensities provided 94–96% of the score. The higher proportion contributed by the doublet propensities in the score makes this method significantly different from conventional homology search methods. In a 41-nucleotide sequence, there are 40 singlet propensities (the C at 31st position is not included in the score) and 780 (=40 × 39/2) doublet propensities, which is part of the reason why doublet propensities contribute to the score greater than singlet propensities.

3.5. Application of the prediction to the newly sequenced portion of the T. lepidozioides chloroplast genome

The most rigorous test of the prediction method is a blind test, in which we predict a result and verify the prediction experimentally. After sequencing the region between petL and clpP, we (i) predicted RNA editing sites in the transcript from that region and (ii) experimentally detected RNA editing sites after the prediction. We sequenced cDNA transcripts from petL to clpP (Fig. 1), identifying 42 C-to-U conversions in this region (Supplementary Table S2).

We expected from the assessment of the prediction method that a score >100 has an accuracy of ∼60%. Seven of the 12 predicted sites (∼58%) were actually edited. Higher scores had a greater accuracy of prediction (Table 2). None of those predicted sequences were identical to the sequences obtained with the singlet and doublet propensities, which makes this result quite important. This blind test clearly demonstrated that a high score using our prediction method provides a high likelihood that the sequence contains an RNA editing site at the 31st position. In Table 2, there were two silent RNA editing sites that did not change the encoded amino-acid residues. Those two predictions can only be achieved using our method. The success of the prediction method above confirms that the characteristics described above (Figs 3A and 4) reflect tangible nucleotide patterns recognized by trans-factors.

Table 2.

Prediction and verification of RNA editing sites (score > 101) in newly sequenced T. lepidozioides genome

| Predicted edited site with −30 to +10 nucleotides | Gene | Position* | Score | Codon* | Unedited → edited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTGTTGATTTCGTAGCTACAGAAACTGCTTCAAATTCTCCA | clpP | −6243 | 120.00 | 199 | S(tCa) → L(tTa) |

| AACCTGTTATTGTCACTAGGATTCCTTCCACGCTTACTACA | petL | 1897 | 112.01 | 1 | T(aCg) → M(aTg) |

| TATTTGCTGCTTCAATTTCAGCTTTAGTTTCATTTATTGGC | petL | 1957 | 109.97 | 21 | S(tCa) → L(tTa) |

| AATGATCCATCAACCTGCTAGTTCCTACTACGATGGACAAG | clpP | −6440 | 108.17 | false positive | |

| AAGTTTATGGCATTGTTGATTTCGTAGCTACAGAAACTGCT | clpP | −6255 | 107.40 | 195 | T(aCa) → I(aTa) |

| CTCCCGGTGGAGCAGTATTAGCAGGAATATCTGTTTATGAT | clpP | −7143 | 106.91 | False positive | |

| GGATTTCAAGGAGCTCATTCAAAACTATTTCGAACTGCTAA | rpl20 | −4681 | 106.11 | 33 | R(Cga) → *(Tga) |

| CAATGCAAGATGTAAAAACATATCTTTCTACAGCACCTGTG | psaJ | 3317 | 106.02 | False positive | |

| AAAATGGTGAAAAAATAAAATTAGGTGTTTCTAGATATACT | rpl33 | 3834 | 105.03 | False positive | |

| ATTTCGTAGCTACAGAAACTGCTTCAAATTCTCCAACGAAT | clpP | −6237 | 103.90 | False positive | |

| TTTAGGCTCCCCGGAGAAGAAGATGCTGTTCGGATCGACGT | clpP | −8036 | 103.15 | 27 | L(ctC) → L(ctT) |

| AGAAGCAAAAGTTTATGGCATTGTTGATTTCGTAGCTACAG | clpP | −6263 | 101.19 | 192 | F(ttC) → F(ttT) |

*Position is the nucleotide number of the predicted edited site (bold) in the sequenced region, whereas the minus number indicates that the editing site is predicted to be on the opposite strand of the deposited sequence. The codon number and conversion in the codon were shown for seven sites.

Experimental identification of RNA editing sites resulted in the identification of additional sites not listed in Table 2 (Supplementary Table S2). Our prediction method gave low scores to those sites. We assume that the RNA editing sites with low scores in our prediction are recognized by trans-factors independent from the ones that recognize G-1 to G-8 sequences (Fig. 2). The current prediction method is based on our classification of the RNA editing site neighbor sequences that may reflect similarities in the trans-factors that recognize those sequences. Therefore, an RNA editing site recognized by a different trans-factor cannot be predicted by this method. This may mean, however, that RNA editing sites recognized by homologous trans-factors, even in other species, can be predicted by the current propensities.

3.6. Application of the prediction to the Araidopsis thaliana chloroplast genome

To test if our method could identify RNA editing sites in other species, we applied our prediction method to the A. thaliana chloroplast genome. RNA editing sites in transcripts of A. thaliana chloroplasts have been extensively analyzed by Tillich et al.,25 and Chateigner-Boutin and Small46 have recently extended these studies. There are 32 known RNA editing sites in protein-coding regions. Our method determined scores >101 for 254 Cs in A. thaliana chloroplast transcripts (GenBank ID: AP000423). Six out of the verified 32 RNA editing sites were included in the 254 Cs. They are editing sites from psbF, clpP, rpoA, rpl23 and ndhB. There are 248 (=254−6) predicted RNA editing sites that have not been experimentally verified and 26 (=32−6) verified RNA editing sites that were missed by our prediction. The large number of predicted sites may contain sites that can be verified as true RNA editing sites, of which the top seven are listed in Table 3. If those predicted sites are false-positives, then the high score was obtained because of lack of information in the prediction method, the existence of trans-factors in T. lepidozioides that evolved to recognize different sequences or the disappearance of trans-factors during the course of evolution. The inability to predict the RNA editing sites in A. thaliana may be due to the existence of trans-factors for RNA editing site recognition that do not exist in T. lepidozioides.

Table 3.

Predicted RNA editing site (score > 130) for A. thaliana chloroplast genome transcripts (AP000423)

| predicted edited site with -30 to +10 nucleotides | gene | position* | score |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATACTGCTCTAGTTGCTGGTTGGGCTGGTTCGATGGCTCTA | psbB | 72477 | 146.96 |

| GACTATAACGAATCCGGGTCTTTGGAGTTACGAAGGGGTAG | psbB | 72649 | 145.06 |

| AAGCAGGGGCTGCGGTAGCTGCTGAATCTTCTACTGGTACA | rbcL | 55142 | 144.09 |

| GCAGGATTCATCATGACAGGAGCTTTTGCTCATGGAGCTAT | psaB | −38415 | 133.73 |

| TATCTGGTGGAGATCATATTCACGCGGGTACAGTAGTAGGT | rbcL | 55946 | 132.84 |

| TACCTATCTCAATAAAGTTTATGATTGGTTCGAAGAACGTC | petB | 75668 | 131.15 |

| CTGGAGTTCCACCTGAAGAAGCAGGGGCTGCGGTAGCTGCT | rbcL | 55124 | 130.87 |

*Position is the nucleotide number of the predicted edited site (bold) in the sequence and the minus number indicates that the editing site is predicted to be on the opposite strand.

3.7. Conclusion

We classified the neighbor sequences of T. lepidozioides chloroplast RNA editing sites, taking advantage of the fact that chloroplast transcripts have multiple RNA editing sites. The neighbor sequences of RNA editing sites can be classified into eight groups using distinct singlet and doublet propensities. The differences in propensities among groups are hypothesized to result from recognition by different trans-factors for each group. The propensities predicted RNA editing sites using the nucleotide sequence alone and worked to predict sites in the genome of the same species. Our prediction was also able to identify silent RNA editing sites. Application of the prediction to chloroplast transcripts of a different species worked with a lower efficiency, yet the validity of these result needs to be experimentally tested. The prediction method is available at http://cib.cf.ocha.ac.jp/~yura/RNAE/.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available online at www.dnaresearch.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

K.Y. was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI (19570157), Y.M. by the JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists, T.A. by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan (17770073), M.H. by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from JSPS KAKENHI (13640707) and M.S. by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from JSPS KAKENHI (2057003).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Kaori Maruyama and Chieko Sugita (Nagoya University) for DNA sequencing.

References

- 1.Bock R. Sense from nonsense: how the genetic information of chloroplasts is altered by RNA editing. Biochimie. 2000;82:549–557. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)00610-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Covello P. S., Gray M. W. RNA editing in plant mitochondria. Nature. 1989;341:662–666. doi: 10.1038/341662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoch B., Maier R. M., Appel K., Igloi G. L., Kössel H. Editing of a chloroplast mRNA by creation of an initiation codon. Nature. 1991;353:178–180. doi: 10.1038/353178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiesel R., Combettes B., Brennicke A. Evidence for RNA editing in mitochondria of all major groups of land plants except the Bryophyta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:629–633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshinaga K., Iinuma H., Masuzawa T., Ueda K. Extensive RNA editing of U to C in addition to C to U substitution in the rbcL transcripts of hornwort chloroplasts and the origin of RNA editing in green plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1008–1014. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.6.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freyer R., Kiefer-Meyer M-C., Kössel H. Occurrence of plastid RNA editing in all major lineages of land plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:6285–6290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin S., Zhang H., Spencer D. F., Norman J. E., Gray M. W. Widespread and extensive editing of mitochondrial mRNAs in dinoflagellates. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320:727–739. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00468-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kugita M., Yamamoto Y., Fujikawa T., Matsumoto T., Yoshinaga K. RNA editing in hornwort chloroplasts makes more than half the genes functional. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2417–2423. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giegé P., Brennicke A. RNA editing in Arabidopsis mitochondria effects 441 C to U changes in ORFs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakasugi T., Hirose T., Horihata M., Tsudzuki T., Kössel H., Sugiura M. Creation of a novel protein-coding region at the RNA level in black pine chloroplasts: the pattern of RNA editing in the gymnosperm chloroplast is different from that in angiosperms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8766–8770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mulligan R. M., Williams M. A., Shanahan M. T. RNA editing site recognition in higher plant mitochondria. J. Hered. 1999;90:338–344. doi: 10.1093/jhered/90.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanc V., Litvak S., Araya A. RNA editing in wheat mitochondria proceeds by a deamination mechanism. FEBS Lett. 1995;373:56–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00991-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu W., Schuster W. Evidence for a site-specific cytidine deamination reaction involved in C to U RNA editing of plant mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:18227–18233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaudhuri S., Carrer H., Maliga P. Site-specific factor involved in the editing of the psbL mRNA in tobacco plastids. EMBO J. 1995;14:2951–2957. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bock R., Hermann M., Kössel H. In vivo dissection of cis-acting determinants for plastid RNA editing. EMBO J. 1996;15:5052–5059. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bock R., Hermann M., Fuchs M. Identification of critical nucleotide positions for plastid RNA editing site recognition. RNA. 1997;3:1194–1200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhuri S., Maliga P. Sequences directing C to U editing of the plastid psbL mRNA are located within a 22 nucleotide segment spanning the editing site. EMBO J. 1996;15:5958–5964. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermann M., Bock R. Transfer of plastid RNA-editing activity to novel sites suggests a critical role for spacing in editing-site recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4856–4861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed M. L., Peeters N. M., Hanson M. R. A single alternation 20 nt 5′ to an editing target inhibits chloroplast RNA editing in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1507–1513. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.7.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitz-Linneweber C., Tillich M., Hermann R. G., Maier R. M. Heterologous, splicing-dependent RNA editing in chloroplasts: allotetrapolidy provides trans-factors. EMBO J. 2001;20:4874–4883. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyamoto T., Obokata J., Sugiura M. A site-specific factor interacts directly with its cognate RNA editing site in chloroplast transcripts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:48–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307163101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasaki T., Yukawa Y., Wakasugi T., Yamada K., Sugiura M. A simple in vitro RNA editing assay for chloroplast transcripts using fluorescent dideoxynucleotides: distinct types of sequence elements required for editing of ndh transcripts. Plant J. 2006;47:802–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tillich M., Lehwark P., Morton B. R., Maier U. G. The evolution of chloroplast RNA editing. Mol. Biol., Evol. 2006;23:1912–1921. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gualberto J. M., Bonnard G., Lamattina L., Grienenberger J. M. Expression of the wheat mitochondrial nad3-rps12 transcription unit: correlation between editing and mRNA maturation. Plant Cell. 1991;3:1109–1120. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.10.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tillich M., Funk H. T., Schmitz-Linneweber C., Poltnigg P., Sabater B., Martin M., Maier R. M. Editing of plastid RNA in Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes. Plant J. 2005;43:708–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirose T., Kusumegi T., Tsudzuki T., Sugiura M. RNA editing sites in tobacco chloroplast transcripts: editing as a possible regulator of chloroplast RNA polymerase activity. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1999;262:462–467. doi: 10.1007/s004380051106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotera E., Tasaka M., Shikanai T. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein is essential for RNA editing in chloroplasts. Nature. 2005;433:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nature03229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okuda K., Nakamura T., Sugita M., Shimizu T., Shikanai T. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein is a site recognition factor in chloroplast RNA editing. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:37661–37667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okuda K., Myouga F., Motohashi R., Shinozaki K., Shikanai T. Conserved domain structure of pentatricopeptide repeat proteins involved in chloroplast RNA editing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8178–8183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700865104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Toole N., Hattori M., Andres C., Iida K., Lurin C., Schmitz-Linneweber C., Sugita M., Small I. On the Expansion of the pentatricopeptide repeat gene family in plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:1120–1128. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lurin C., Andrés C., Aubourg S., Bellaoui M., Bitton F., Bruyère C., Caboche M., Debast C., Gualberto J., Hoffmann B., Lecharny A., Le Ret M., Martin-Magniette M. L., Mireau H., Peeters N., Renou J. P., Szurek B., Taconnat L., Small I. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2089–2103. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salone V., Rüdinger M., Polsakiewicz M., Hoffmann B., Groth-Malonek M., Szurek B., Small I., Knoop V., Lurin C. A hypothesis on the identification of the editing enzyme in plant organelles. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4132–4138. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cummings M. P., Myers D. S. Simple statistical models predict C-to-U edited sites in plant mitochondrial RNA. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mower J. P. PREP-Mt: predictive RNA editor for plant mitochondrial genes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson J., Gopal S. Genetic algorithm learning as a robust approach to RNA editing site prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:145. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du P., He T., Li Y. Prediction of C-to-U RNA editing sites in higher plant mitochondria using only nucleotide sequence features. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;358:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeng W. H., Liao S. C., Chang C. C. Identification of RNA editing sites in chloroplast transcripts of Phalaenopsis aphrodite and comparative analysis with those of other seed plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:362–368. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugita M., Miyata Y., Maruyama K., Sugiura C., Arikawa T., Higuchi M. Extensive RNA editing in transcripts from the psbB operon and rpoA gene of plastids from the enigmatic moss Takakia lepidozioides. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006;70:2268–2274. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyata Y., Sugita C., Maruyama K., Sugita M. RNA editing in the anticodon of tRNALeu (CAA) occurs before group I intron splicing in plastids of a moss Takakia lepidozioides S. Hatt. & Inoue. Plant Biol. 2008;10:250–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2007.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yura K., Toh H., Go M. Putative mechanism of natural transformation as deduced from genome data. DNA Res. 1999;6:75–82. doi: 10.1093/dnares/6.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim T. P. O., Yura K., Go N. Amino acid residue doublet propensity in the protein-RNA interface and its application to RNA interface prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6450–6460. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawrence C. E., Altschul S. F., Boguski M. S., Liu J. S., Neuwald A. F., Wootton J. C. Detecting subtle sequence signals: a Gibbs sampling strategy for multiple alignment. Science. 1993;262:208–214. doi: 10.1126/science.8211139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu W., Fester T., Bock H., Schuser W. RNA editing in higher plant mitochondria: Analysis of biochemistry and specificity. Biochimie. 1995;77:79–86. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)88108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inada M., Sasaki T., Yukawa M., Tsudzuki T., Sugiura M. A systematic search for RNA editing sites in pea chloroplasts: an editing event causes diversification from the evolutionarily conserved amino acid sequence. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;45:1615–1622. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chateigner-Boutin A. L., Small I. A rapid high-throughput method for the detection and quantification of RNA editing based on high-resolution melting of amplicons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.