Abstract

F1-ATPase is an ATP-driven rotary molecular motor in which the central γ-subunit rotates inside the cylinder made of α3β3 subunits. The amino and carboxy termini of the γ-subunit form the axle, an α-helical coiled coil that deeply penetrates the stator cylinder. We previously truncated the axle step by step, starting with the longer carboxy terminus and then cutting both termini at the same levels, resulting in a slower yet considerably powerful rotation. Here we examine the role of each helix by truncating only the carboxy terminus by 25–40 amino-acid residues. Longer truncation impaired the stability of the motor complex severely: 40 deletions failed to yield rotating the complex. Up to 36 deletions, however, the mutants produced an apparent torque at nearly half of the wild-type torque, independent of truncation length. Time-averaged rotary speeds were low because of load-dependent stumbling at 120° intervals, even with saturating ATP. Comparison with our previous work indicates that half the normal torque is produced at the orifice of the stator. The very tip of the carboxy terminus adds the other half, whereas neither helix in the middle of the axle contributes much to torque generation and the rapid progress of catalysis. None of the residues of the entire axle played a specific decisive role in rotation.

INTRODUCTION

The enzyme ATP synthase consists of a membrane-embedded F0 portion and an off-membrane F1 portion (1–3). Both are rotary molecular motors, and are interconnected with each other through a common rotor shaft and a stator stalk (4). A downhill proton flow through the F0 motor drives rotation of the common shaft, which causes conformational changes in F1 that lead to the synthesis of ATP from ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi). Conversely, hydrolysis of ATP in F1 can make the rotor rotate in the reverse direction, so that F0 is forced to pump protons in the reverse direction (against the proton gradient). The proton flow in F0 is thus coupled with the chemical reaction (ATP synthesis/hydrolysis) in F1 by a rotational catalysis mechanism (5,6). The isolated F1 motor only hydrolyzes ATP, and is called F1-ATPase. The minimal subcomplex of F1-ATPase capable of ATP hydrolysis-driven rotation consists of α3β3γ subunits (4,7), which we here refer to also as F1. In a crystal structure of mitochondrial F1 (MF1; see Fig. 1), the central γ-subunit is surrounded by the stator cylinder formed of α3β3 subunits (8). Three catalytic nucleotide-binding sites reside at β-α interfaces, and are hosted primarily by a β-subunit. In the original structure (8), the three sites contain an ATP analog (between βTP and αTP), ADP (βDP and αDP), and no nucleotide (βE and αE). The other three interfaces form, mainly through an α-subunit, noncatalytic nucleotide-binding sites, which bind the ATP analog in the crystal. The noncatalytic sites take part in relieving the enzyme of the MgADP-inhibited state (9–11).

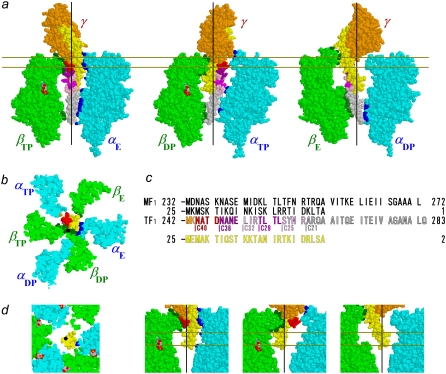

FIGURE 1.

Atomic structure of MF1 (22). Truncations of γ-subunit are shown, with color scheme in c; the N-terminal α-helix is shown in yellow. Those atoms of α-subunits and β-subunits that are within 0.5 nm from an atom of γ (excluding hydrogens) are colored blue and dark green, respectively. Nucleotides are shown in CPK colors. Black lines in side views and black dots in bottom views represent putative rotation axis (21). (a) Side views show central γ and an opposing α-β pair. Membrane-embedded F0 portion of ATP synthase would be above the γ-subunit. (b) Bottom view of section between pair of gold lines in a. (c) Amino-acid sequences at the C-terminus and N-terminus of γ in MF1 (36) and TF1 (30), except that numbering for TF1 in our study here starts from Met-1, which is absent in the expressed wild-type protein. In Fig. 1 B of Furuike et al. (27), Ala-2 was incorrectly shown as Ala-1. (d) Central portions of bottom and side views for γ-ΔC36.

During ATP hydrolysis, the central γ-subunit rotates in the counterclockwise direction when viewed from the F0 side (12), in steps of 120° per ATP hydrolyzed (13,14). The 120° step is divided into 80–90° and 40–30° substeps, separated by at least two chemical reactions, each taking ∼1 ms at room temperature. The 80–90° substep is driven by ATP binding and likely also by ADP release, and the 40–30° substep by the release of Pi (15,16). Hydrolysis of ATP occurs in the 80–90° interim (17). The α3β3 hexamer of F1 from thermophilic Bacillus PS3 (TF1) has a structure similar to MF1, but is threefold symmetric in the absence of bound nucleotides (18). It is the asymmetric γ-subunit that dictates which of the three basically equivalent catalytic sites will bind an ATP molecule (19). Dictation by the γ-subunit was clearly demonstrated in an experiment (20) where clockwise rotation of the γ-subunit, driven by an external force, led to ATP synthesis in the catalytic sites of the α3β3γ subcomplex of TF1: by itself, F1 is a reversible mechano-chemical energy converter in which the γ-angle determines which of the chemical reactions (binding/release of ADP and Pi, synthesis/hydrolysis of ATP, and release/binding of ATP) will occur in the three catalytic sites.

Although the basic coupling scheme between rotation and chemical reactions was worked out (16) as outlined above, the structural basis of torque generation remains unclear. One suggestion involved a push-pull mechanism (21). In the MF1 structure in Fig.1 a (22), the axle of the F1 motor, i.e., the portion of the γ-subunit that deeply penetrates the α3β3 cylinder, is formed of the antiparallel α-helical coiled coil of amino- (N-) and carboxy- (C-) termini, the bottom tip comprising the longer C-terminal α-helix alone. The axle is held by the stator cylinder at two positions, i.e., the top orifice and the bottom (Fig. 1, dark green and blue atoms). The β-subunits binding a nucleotide (βTP and βDP) are bent toward, and apparently push, the axle at the top, whereas the empty β-subunit (βE) retracts and pulls the axle. The push-pull actions would rotate the skewed and slightly curved axle in a conical fashion. This mechanism would require the axle to be rigid and its tip be held relatively stationary as a pivot. Indeed, the bottom of the α3β3 cylinder forms a hydrophobic “sleeve” that could act as a bearing (8). For communication of the γ-angle to the catalytic sites, the lever action of a rigid axle would also be an efficient mechanism.

Truncation of the axle will reveal whether, or to what extent, the rotation and control of catalysis rely on the pivoting of a rigid axle. In earlier studies, a deletion of 10 residues (23) at the C-terminus of Escherichia coli F1 (EF1) or of 20 C-terminal residues (24) of chloroplast F1 (CF1) resulted in reduced but significant ATPase activity. With a deletion of 12 C-terminal residues, EF1 remained functional, without affecting torque, although hydrolysis activity was gradually diminished at longer deletions (25). We truncated the C-terminus of TF1-γ up to 21 residues (Fig. 1 a, gray), but the mutants rotated with a torque ∼50% or more of the wild-type (26). These studies did not remove the bottom interactions completely: the remaining axle tip would still touch the bottom sleeve of the stator cylinder. In our most recent study (27), we found that an axle-less mutant in which 43 C-terminal and 22 N-terminal residues of the γ-subunit of TF1 were deleted (up to slightly above the red residues and opposing yellow residues in Fig. 1 a) still rotated in the correct direction. This work ruled out the necessity of pivoting action of a rigid axle in producing unidirectional rotation. However, both the rotary speed and the rate of ATP hydrolysis decreased as we truncated the axle (opposing N-terminal and C-terminal α-helices were truncated simultaneously, such that their remaining tips were at about the same height), and short mutants could rotate only small (40 nm in diameter) beads and not larger ones (0.29 μm and above). Efficient catalysis would still require axle-stator interactions.

Here, we investigated the role of the C-terminal α-helix of the γ-subunit by truncating it stepwise beyond 21 amino-acid residues, leaving the N-terminal helix intact in the stator cavity. Mutants of up to 36 deletions were active with reduced functionality, although their stability gradually decreased with longer deletions. The 36-deletion mutant, in which the entire C-terminal α-helix inside the stator cavity was absent, rotated stepwise with ∼50% the torque of the wild-type. The very tip of the C-terminal α-helix that touches the bottom sleeve is essential for rapid catalysis and generation of full torque, but the rest of the C-terminal helix up to the base of the axle is completely unnecessary for the residual rotation with half the torque. The N-terminal helix also contributes little, in that its presence does not improve rotational characteristics significantly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Streptavidin-coated polystyrene beads (0.29 μm in diameter) were purchased from Seradyn (Indianapolis, IN). Biotin-PEAC5-maleimide was from Dojindo (Kumamoto, Japan), and other chemicals were of the highest grade commercially available. In rotation and hydrolysis experiments, Mg2+ was always 2 mM in excess over ATP.

Construction of mutants

Mutations were constructed on the plasmid pKABG1/HC95 that carries genes for the α (C193S), β (His10 at the amino terminus), and γ (S107C and I210C) subunits of TF1 that we regard as the wild-type (15,28). We introduced γ C-terminal truncations, designated as γ-ΔCm, where m is the number of residues deleted, in pKABG1/HC95, as previously described (26,27). The mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Shimadzu Biotech, DNA Sequence Service, Kyoto, Japan). In E. coli strain JM103 Δ(uncB–uncD), which has lost the ability to express authentic FoF1-ATPase (29), all mutant proteins were expressed to a level similar to that of the wild-type. Purified γ-ΔC36 was checked by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (APRO Life Science Institute, Naruto, Japan). The γ-ΔC36 contained three major components with masses of 54,700 (expected mass for α, 54,714.8), 53,340 (expected mass for β, 53,355.9), and 27,770 (expected mass for γ Ala-2 to Asp-247, 27,785.1). The amino-acid sequence here and in Fig. 1 c is from Ohta et al. (30), except that our numbering in this and in previous work (26,27) began with Met-1, which is absent in the expressed wild-type, and which we assume is also absent in the mutants described here. The actual sequence of TF1 that we used here and previously (26,27) is slightly different from that in Ohta et al. (30), and the C-terminus of the wild-type in this study is Gln-285 and not Gln-283, counting from Met-1 (M. Yoshida, unpublished findings). Because the differences are not in the N-terminal and C-terminal that form the axle, we adopt the published sequence in this study. The expected masses above, however, were calculated on the basis of the actual sequence.

Purification and biotinylation of F1

Wild-type and mutant F1 were purified as described (26,27,31), without heat treatment and passage through a butyl-Toyopearl column (Tosoh 650M, Tokyo, Japan, used for removal of bound nucleotide). The cell lysate was ultracentrifuged for 30 min at 40,000 rpm. Decanted supernatant was passed through a Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) Superflow column (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The eluent containing F1 in buffer A (300 mM imidazole, pH 7.0, and 100 mM NaCl) was mixed with 70% ammonium sulfate and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and stored at 4°C. Before use, the precipitate was dissolved in buffer B (100 mM KPi, pH 7.0, and 2 mM EDTA) and passed through a size exclusion column (Superdex 200 HR 10/30, Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) pre-equilibrated with buffer B to remove DTT and possible denatured enzyme. All procedures were at 4°C, except for the Ni-NTA column treatment, which was at room temperature.

Purified F1 was biotinylated at the two cysteines (γ-107C and γ-210C) by incubation with a fourfold molar excess of biotin-PEAC5-maleimide within 4 h after lysis of E. coli. Unbound biotin was removed using the above size exclusion column, pre-equilibrated with buffer B.

Measurement of hydrolysis activity

The rate of ATP hydrolysis by the mutants at 2 mM ATP was measured using a spectrophotometer (model U-3100, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) at 23°C. The reaction was started by rapidly adding unbiotinylated F1 in buffer B, at a final concentration of 5–10 nM, into buffer C (10 mM MOPS (3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid)-KOH, pH 7.0, 50 mM KCl, and 2 mM MgCl2) containing an ATP regeneration system consisting of 0.2 mM NADH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), 1 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 250 μg mL−1 pyruvate kinase (rabbit muscle, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), and 50 μg mL−1 lactate dehydrogenase (hog muscle, Roche Diagnostics). The hydrolysis rate was determined from the decrease in NADH absorbance at 340 nm (10). The rate was estimated over 2–40 s after mixing.

Preparation of Ni-NTA glass surface

Glass coverslips (NEO Micro Cover Glass No. 1, 24 × 32 mm2, Matsunami, Osaka, Japan) were set vertically and separately on a ceramic glass holder, and were immersed in 12 N KOH for 24 h to clean the surfaces (20,26). Then the coverslips, along with the holder, were extensively washed with ultrapure water. To 100 mL ultrapure water in a glass beaker containing a small stirrer bar, 0.02% (v/v) acetic acid was added and mixed well on a magnetic stirrer at 60°C in a fume hood; ∼2% (v/v) 3-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane (TSL8380, Toshiba GE silicone, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) was then added with a glass pipette and mixed. The prewashed coverslips in the holder were placed carefully in the silane solution, and stirring continued for a further 15–20 min. The hot glass beaker containing the silane solution and coverslips was taken out of the fume hood and placed in a constant-temperature oven at 90°C for 2 h. After cooling in the fume hood, the coverslips were washed vigorously with ultrapure water. On a clean paper, 20 μL of 100 mM DTT in 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.0, were sandwiched between pairs of silanized coverslips and kept for 20 min at room temperature to reduce the −SH groups on the surfaces. After vigorous washing with ultrapure water, 10 mg mL−1 Maleimide-C3-NTA (Dojindo) in 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.0, was sandwiched between coverslip pairs and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After washing with water, the coverslips were incubated at room temperature in 100 mL of 10 mM NiCl2 for 20 min. Finally, the coverslips in the holder were washed and stored in 100 mL of ultrapure water at room temperature. They were used within a few weeks.

Observation of rotation

A flow chamber was constructed of the Ni-NTA-coated bottom coverslip (24 × 32 mm2) and a top uncoated coverslip (18 × 18 mm2), separated by two greased strips of Parafilm cover sheet. Rotation assays were conducted in buffer C containing an ATP regenerating system consisting of 0.2 mg mL−1 creatine kinase (rabbit muscle, Roche Diagnostics) and 2.5 mM creatine phosphate (Roche Diagnostics). Streptavidin-coated beads of 0.29-μm diameter were washed three times with buffer C containing 5 mg mL−1 bovine serum albumin (BSA; Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) through centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to remove preservatives. The concentration of beads was finally adjusted to 0.1% (w/v) with 5 mg mL−1 BSA. One flow-chamber volume of biotinylated 0.5–100 nM F1 was infused into the chamber and incubated at room temperature for 2 min, so that the F1 subcomplex was fixed on the Ni-NTA coated coverslip through the histidine tags. The chamber was then washed three times with 5 mg mL−1 BSA and incubated for 5 min. One chamber volume of the prewashed streptavidin-coated beads was infused into the chamber and kept for 15 min at room temperature, so that beads were attached to the biotinylated γ-subunit of the α3β3γ complex. The flow cell was washed three times with buffer C to remove unbound beads. Finally, five chamber volumes of 2 mM MgATP in buffer C containing the regeneration system were infused, and the chamber was sealed with silicone grease to avoid evaporation. Rotation was observed at 23°C on an inverted microscope (IX71, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a stable mechanical stage (KS-O, ChuukoushaSeisakujo, Tokyo, Japan). Bead images were captured with a CCD camera (Lynx IPX-VGA210L, Imperx, Boca Raton, FL) at 500 frames s−1 as an eight-bit AVI file. The centroid of bead images was calculated as described previously (15). For clear identification of rotation, a duplex of beads was always selected for analysis.

Estimation of torque

The torque N that the motor produced was estimated from the instantaneous rotary speed ω (in radian s−1) during a 120° step, using (13,32):

|

(1) |

where ξ is the frictional drag coefficient given, for the case of a duplex of spherical beads, by

|

(2) |

where a is the bead radius, x1 and x2 the radii of the rotation of inner and outer beads, and η is the viscosity of the medium (∼0.93 × 10−3 N s m−2 at 23°C). We selected those duplexes with x2 > 0.2 μm; x1 was taken as 0. The drag in Eq. 2 is likely an underestimate (13,33).

RESULTS

Assembly of mutant subcomplexes

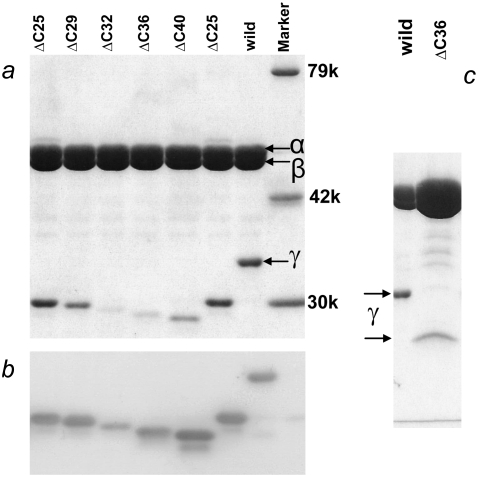

In this study, we used an α(C193S)3β(His10 at amino terminus)3γ(S107C, I210C) subcomplex of TF1 (15) as the wild-type. This subcomplex has sole two cysteines at the protruding portion of the γ-subunit for labeling with an external probe, and histidine tags at the bottom of the β- subunits for attachment of the protein to a glass surface. We made mutants in which 25, 29, 32, 36, or 40 amino-acid residues were deleted from the C-terminus of the γ-subunit, i.e., γ-ΔC25 to γ-ΔC40. All these mutants were expressed in E. coli to a level similar to that of the wild-type. In particular, the expression level of the γ-subunit was independent of the degree of truncation. The yield of purified mutant subcomplex containing the γ-subunit, however, was variable and lower compared with the wild-type (Fig. 2): short mutants did not assemble well. We also found that shorter mutants were unstable upon storage, and we had to use γ-ΔC32 and γ-ΔC36 within 3 days of final purification.

FIGURE 2.

Confirmation of γ-truncations by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. (a) Ten percent gel contains 0.1% SDS, stained with Coomassie brilliant Blue R-250. (b) Western blot of a stained with anti-γ-antibody. (c) Overloaded gel shows absence of intact γ in mutant. Amount of γ in purified samples was variable, depending on preparations; γ-ΔC40 in another preparation showed a barely detectable γ band. Side bands in b are presumably dissociated and degraded γ.

Rotation

Rotation of the wild-type and mutants was observed by attaching the β-subunits to a glass surface through the histidine residues at the N-terminus, and putting a duplex of 0.29-μm beads on the γ-subunit as a marker. We found rotary beads up to γ-ΔC36, but none with γ-ΔC40. When a duplex on a mutant rotated, it did so in a counterclockwise direction, as with the wild-type (observed from above in Fig. 1 a), usually for more than 100 revolutions, even with γ-ΔC36 (Fig. 3 a).

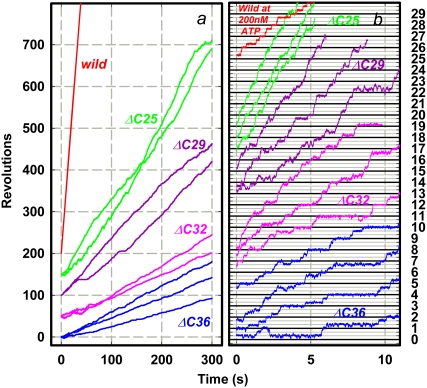

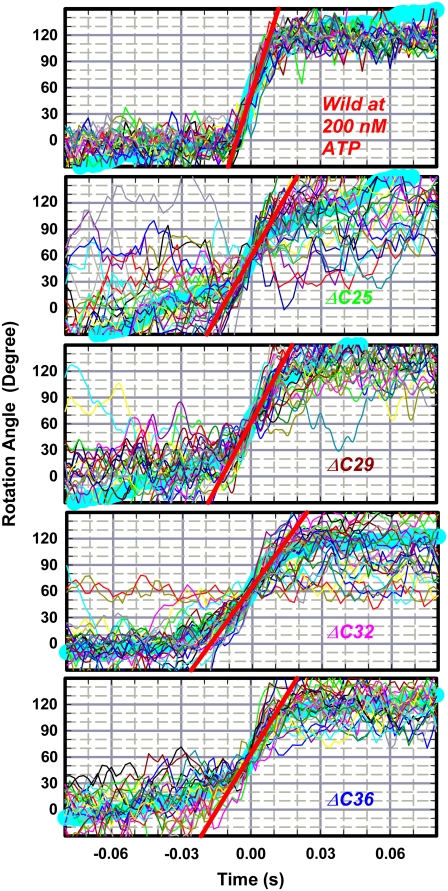

FIGURE 3.

Time courses of rotation of 0.29-μm bead duplex attached to γ-subunit. All rotations were counterclockwise when viewed from above in Fig. 1 a. Horizontal lines in b are separated by 120°. ATP concentration was 2 mM, except for the wild-type in b, which stepped because of infrequent binding of ATP at 200 nM (rate constant for ATP binding (13), ∼2 × 107 M−1s−1). Dwelling angles of mutants are plotted ∼80° ahead of ATP-waiting dwells of the wild-type, because long pauses such as those in γ-ΔC29 in a also occurred at same angles and because long pauses in the wild-type, because of MgADP inhibition (11), occur at ∼80°. This assignment, however, is tentative because we could not determine ATP-waiting angles of mutants. Bottom curve in b shows an exceptional case of reversal over two 120°-steps in a sluggish phase, after which more regular rotation resumed beyond the right-hand axis. Temperature, 23°C.

Finding rotary beads became progressively difficult for shorter mutants. With the wild-type, several hundred rotating bead duplexes were found per observation chamber when F1 at 0.5 nM was infused. Mutants were examined within 3–4 days of preparation (kept at room temperature because TF1 is cold-labile), and F1 at a higher concentration had to be applied to observe rotation. With γ-ΔC25, 20–25 duplexes rotated per chamber at 2 nM F1; 8–10 duplexes at 10 nM γ-ΔC29; 3–4 duplexes at 20 nM γ-ΔC32; and ∼2 duplexes at 50 nM γ-ΔC36, if observed within 2 days (none rotated after 4 days). Rotation could be observed for at least 2 h after chamber preparation. Nonrotating mutant γ-ΔC40 was closely examined in 5–6 chambers at various F1 concentrations up to 100 nM, beginning a few hours after purification, but no bead rotated.

Rotation time courses of beads that rotated relatively fast at 2 mM ATP are shown in Fig. 3. For mutants except γ-ΔC25, we failed to observe rotation at lower ATP concentrations. Rotation of wild-type F1 was basically continuous at a video resolution of 2 ms. At this saturating ATP concentration, a catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis under unloaded conditions takes only ∼2 ms at room temperature (15), and thus the average speed of ∼15 revolutions per second (rps) observed here is limited by viscous friction against the 0.29-μm bead duplex. Time-averaged speeds of mutants were an order of magnitude lower, ranging from ∼2 rps (γ-ΔC25) to ∼0.5 rps (γ-ΔC36). The cause is not the mutants' lower torque, which would result in a lower speed at all moments, but the mutants' tendency to dwell at angles separated by 120° (Fig. 3 b). Unlike longer mutants in our previous study (γ-ΔC21 or longer) (26), we could not find rotation when 0.49-μm beads were attached instead of the 0.29-μm beads. The failure to find rotation in γ-ΔC40 with 0.29-μm beads, despite the rotation, though very rare, of 40-nm beads attached to γ-ΔN22C43 (27), also points to a load effect.

The wild-type also showed a tendency to stumble at angles separated by 120°, even at 2 mM ATP, at ∼80° ahead of ATP-waiting angles (32). The stumbling in the wild-type is load-dependent: with a high load such as a duplex of 0.95-μm beads, we often observed a momentary pause at this angle, but pauses were less conspicuous with smaller beads. At this angle, the torque of the motor vanishes until the splitting of ATP into ADP and Pi and the release of Pi have taken place, each requiring ∼1 ms under a negligible load (7,15–17). Presumably, a thermal barrier against one or both of these reactions is effectively heightened by friction between the beads and the glass surface (or between the beads and F1), leading to a longer dwell before torque generation. The implication here is that climbing the barrier requires some rotation or rotational fluctuation, as, for example, discussed for Pi release (16). For the mutants, we could not ascertain the angles of stumbling, but the load dependence suggests that the mutants also tend to dwell at ∼80° ahead of ATP-waiting angles. The barrier at these angles would be higher for the mutants because of inefficient coupling between γ rotation and chemical reactions, or because fluctuation (inclination) of short γ may increase the chance of surface interaction. Possibilities other than the barrier at ∼80° cannot be excluded.

ATP hydrolysis activity

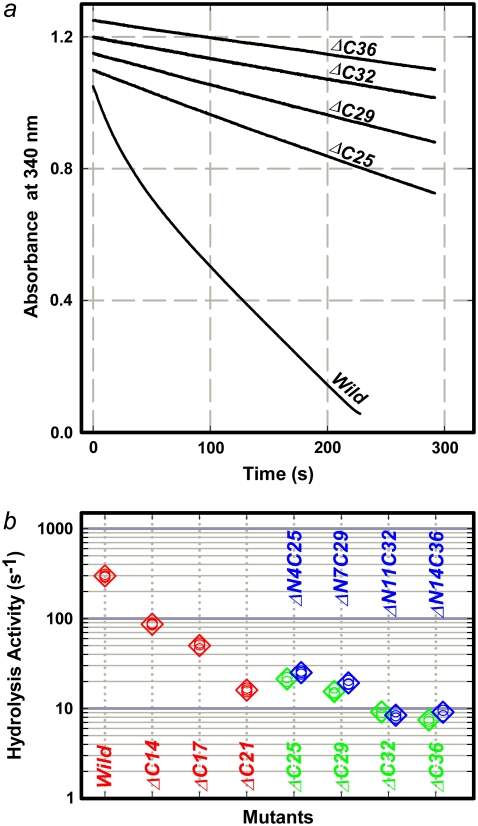

The rate of ATP hydrolysis measured under bulk, unloaded conditions supported the above view that load-dependent stumbling slows down the rotation. Precise estimation of the rate of hydrolysis was impossible, because mutant γ tended to dissociate from the subcomplex, and for this reason, we were unable to go through the time-consuming procedure of removing completely the tightly bound inhibitory nucleotide (31). Without correcting for these effects, and thus at lower bounds, we obtained the following hydrolysis rates (Fig. 4 b): ∼22 s−1 (γ-ΔC25), ∼16 s−1 (γ-ΔC29), ∼9 s−1 (γ-ΔC32), and ∼8 s−1 (γ-ΔC36) at 2 mM ATP, which we confirmed as saturating (same rates at 6 mM ATP). These values are lower than the wild-type rate of ∼300 s−1 (Fig. 4 b), but higher than the rate of hydrolysis by the γ-less mutant α3β3 of ∼5 s−1 (27), implying that the short γ-subunits still contribute to the progress of catalysis. The hydrolysis rates of the short-γ mutants above, on the other hand, are higher than the rate of 120° stepping, or three times the average speed, in the bead rotation (Fig. 3). If the infrequent stepping of the mutants compared to the wild-type (Fig. 3 b) resulted solely from inefficiency of catalysis in the mutants, e.g., from infrequent ATP binding, then hydrolysis and rotational stepping rates should both be low and of the same value. In fact, the rotation was slower (and unobserved with large beads), which we attribute to the attachment of a bead duplex that would augment the probability of surface hindrance. In the previous study on γ-ΔN4C25 to γ-ΔN22C43, the rotation of 40-nm beads was commensurate with the rate of hydrolysis, whereas 0.29-μm beads rotated more slowly (27).

FIGURE 4.

ATP hydrolysis activity. (a) Time courses of hydrolysis monitored as decrease in NADH absorbance at 340 nm. A decrease of one absorbance unit corresponds to hydrolysis of 1.6 × 10−4 M of ATP. Reaction was initiated by adding F1 at a final concentration of 10 nM (mutants) or 5 nM (wild-type) to coupled-assay medium containing 2 mM ATP. (b) Summary of hydrolysis rates at 2 mM ATP. Green, this work; red, previous work (26), in which mutants were prepared with a regular procedure including heat shock, and bound nucleotides were removed; blue, simultaneous truncation of both N-terminus and C terminus of γ-subunit (27), where treatment with size-exclusion column was performed at room temperature, which helped to stabilize mutants. Small circles indicate individual data, and large diamonds indicate their average.

We note that the activities of the mutants γ-ΔC25 to γ-ΔC36 are almost time-independent, compared with the wild-type that is gradually converted to a steady-state mixture of active and MgADP-inhibited enzymes (Fig. 4 a). The mutants might have been inhibited from the beginning, but if we start with inhibited wild-type enzyme, the activity initially rises to reach the same steady-state value. The activities of γ-ΔN4C25 to γ-ΔN22C43 also changed little with time (27), whereas longer mutants up to γ-ΔC21 showed deceleration (26). Leverage action supported by the γ tip may promote the process of inhibition, in addition to allowing rapid rotation to proceed.

Torque of the mutants

Except for the stumblings, the mutants rotated basically in one direction, implying generation of a torque. To infer the torque, we analyzed the instantaneous rotary speed during the 120° stepping, assuming that the speed was limited by viscous friction against the bead duplex. The stepping speed of the short mutants was about half the speed of the wild-type (Fig. 5), implying half the wild-type torque.

FIGURE 5.

Stepping records for torque estimation. Thin colored curves show 30 consecutive steps; thick cyan curve constitutes their average. Individual step records were shifted vertically by a multiple of 120° to obtain overlap. Time zero for each step record was assigned by eye to the data point closest to 60°. Straight red lines indicate linear fit to the cyan curve between 30° and 90°.

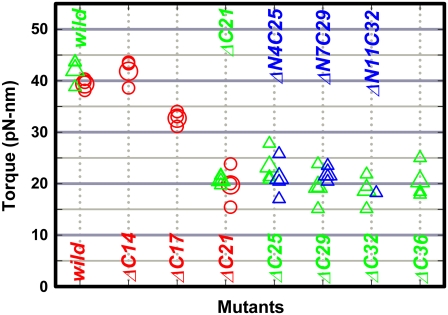

For quantitative estimation, we averaged 30 consecutive steps to obtain the thick cyan curves in Fig. 5, and calculated the torque as the slope of the cyan curve (instantaneous rotary speed) times the frictional drag coefficient of the bead duplex, as shown in Eqs. 1 and 2. The wild-type rotated at a constant speed, implying an angle-independent torque of ∼40 pN·nm, as previously reported (7). The torque of the mutants estimated in the central 30°–90° portion of the average curve was ∼20 pN·nm (Fig. 6, green symbols), half the torque of the wild-type. Angle dependence could not be determined in the mutants because the steps were too noisy. The apparent sluggishness outside the 30°–90° region likely resulted from the simple averaging of noisy and ill-synchronized steps. These mutants, however, apparently produce half the normal torque at least over half the step angle of 120°.

FIGURE 6.

Torque of gamma deletion mutants. Green, this study; red (26) and blue (27), previous results. Circles, torque estimated with a duplex of 0.49-μm beads; triangles, 0.29-μm bead duplex. Small symbols represent individual estimations, and large symbols represent their average.

Because the fluctuation of the bead (γ) angle is large in the mutants compared to the wild-type (Fig. 5), one could argue that the 120° steps of the mutants represent occasional large-amplitude thermal fluctuations (diffusion and catch) rather than motion under torque (with overlapping fluctuations). We cannot rule out this possibility completely, but our previous study (26) suggests that our torque estimation is reasonable. There, we used the same method to estimate the torque of the wild-type and mutants γ-ΔC14 to γ-ΔC21 (Fig. 6, red). The torque values of these mutants were independent of the ATP concentration between 2 mM and 20 nM. At a saturating concentration of 2 mM ATP, the previous mutants rotated continuously with only occasional stumblings, and thus the torque values at 2 mM ATP, essentially calculated from the average speed over many revolutions, are genuine. At low ATP concentrations, both the wild-type and the mutants rotated in 120° steps, and the fluctuations of γ-ΔC17 and γ-ΔC21 were as extensive as the present mutants of γ-ΔC25 to γ-ΔC36. Yet the torque of stepping and fluctuating γ-ΔC17 and γ-ΔC21 estimated in the 30–90° portion of the averaged steps agreed with the estimates at 2 mM ATP. The apparent torque values for the present mutants are all ∼20 pN·nm, similar to the torque of γ-ΔC21. The extent of fluctuations, which, to some extent, varies from bead to bead, is not different from that of the previous mutants. We thus think that the torque values in Fig. 6 are reliable. Thus the residues between γ-ΔC21 and γ-ΔC36 do not contribute to torque production, except for a probable role as lever for an additional torque when the γ tip is present.

DISCUSSION

In the MF1 structure (Fig. 1 a), we see that the α-helical coiled coil of the N-terminus and C- terminus of the γ-subunit deeply penetrates the central cavity of the α3β3 cylinder, to serve as the axle. The axle is held by the cylinder wall at two positions, at the orifice and at the bottom. Presumably, similar contacts/interactions exist in EF1 and TF1, as indicated by structural (18,34) and sequence (Fig. 1 c) resemblances. Most of the bottom interactions are in the region deleted in the γ-ΔC21 mutation (Fig. 1 a, gray). Fig. 6 shows that the bottom interactions are essential for the generation of normal torque. Half the torque, however, is produced without the bottom contacts. The middle portion of the axle, i.e., those residues of γ in the central cavity of the α3β3 cylinder, appears to play no positive role in torque production.

The previous study, where both the N-terminus and C-terminus of the γ-subunit were truncated simultaneously (27), indicated nonessential roles for the middle portion. A possibility remained, however, that the tip of the truncated axle still touched the cylinder wall, thereby sustaining the residual torque. Here, we truncated only the C-terminus, leaving the N-terminal helix intact. The results are basically indistinguishable from those of double truncations (Figs. 4 b and 6). The implication is that the N-terminal helix alone does not add anything to the mechanism of torque production. Either the remaining N-terminus is too flexible, possibly failing to form a complete α-helix, or its tip remains in the cavity and does not make significant contact with the wall. The residual torque of ∼20 pN·nm appears to be produced entirely by the contacts at the orifice.

The rate of ATP hydrolysis (Fig. 4 b), which would correspond to the rate of unloaded rotation, also suggests that the middle portion of the axle does not play a significant role in the progression of catalysis. The N-terminus which remained intact in this study does not accelerate catalysis, implying that it cannot lower the energy barrier that causes the stepping behavior at the saturating ATP concentration. Although the measured rate of hydrolysis is not reliable, indicative only of the lower bound, it seems reasonable that the truncated tip that would stay in the central cavity does not play a significant role. For CF1, a report indicated that truncation of the N-terminal helix alone diminishes ATPase activity, depending on the extent of truncation (35). Whether the lower activity resulted from a lower stability of the reconstituted α3β3γ complex, or from less efficient transmission of the conformational signal to the catalytic sites, has not been established. In this regard, we also note that successive truncations of TF1 γ, whether both N-terminus and C-terminus or C-terminus alone, resulted in a gradual and significant loss of stability of the complex. The residues in the middle portion of the axle contributed to stability, though not much to function.

The major issue to be clarified is of how the orifice interactions alone can produce the sizable torque. More mysterious is the fact that the γ head alone, the portion of γ that would simply sit on the concave entrance of the orifice, can rotate in the correct direction for more than 100 revolutions without being detached from the stator cylinder (27). We cannot yet propose a persuasive mechanism. New atomic structures, other than those available to date that are not grossly different from each other, are highly awaited. Whether the truncated constructs can synthesize ATP when rotated in reverse is another key question that remains open.

As a final remark, we note that all the γ-truncation studies reported so far, including our own, do not reveal a specific residue in the axle that plays a key role in catalysis or rotation. All show a progressive diminishment of function with degree of truncation, including a plateau phase, as in our studies. Specific interactions, such as the hydrogen bond or salt-bridge formation, appear to play a minor role, if any, in rotation.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Shimo-Kon, K. Shiroguchi, T. Okamoto, Y. Onoue, M. Yusuf Ali, D. Patra, and M. Shio for technical assistance and discussions, and K. Sakamaki and M. Fukatsu for encouragement and laboratory management.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Specially Promoted Research and the 21st Century COE Program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan.

Editor: David D. Hackney.

References

- 1.Kagawa, Y., and E. Racker. 1966. Partial resolution of the enzymes catalyzing oxidative phosphorylation. IX. Reconstruction of oligomycin-sensitive adenosine triphosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 241:2467–2474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catteral, W. A., and P. L. Pedersen. 1971. Adenosine triphosphatase from rat liver mitochondria. I. Purification, homogeneity, and physical properties. J. Biol. Chem. 246:4987–4994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cox, G. B., J. A. Downie, L. Langman, A. E. Senior, G. Ash, D. R. H. Fayle, and F. Gibson. 1981. Assembly of the adenosine triphosphatase complex in Escherichia coli: assembly of F0 is dependent on the formation of specific F1 subunits. J. Bacteriol. 148:30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida, M., E. Muneyuki, and T. Hisabori. 2001. ATP synthase—a marvelous rotary engine of the cell. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer, P. D., and W. E. Kohlbrenner. 1981. The present status of the binding-change mechanism and its relation to ATP formation by chloroplasts. In Energy Coupling in Photosynthesis. B. R. Selman and S. Selman-Reimer, editors. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 231–240.

- 6.Oosawa, F., and S. Hayashi. 1986. The loose coupling mechanism in molecular machines of living cells. Adv. Biophys. 22:151–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinosita, K., Jr., K. Adachi, and H. Itoh. 2004. Rotation of F1-ATPase: how an ATP-driven molecular machine may work. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33:245–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrahams, J. P., A. G. W. Leslie, R. Lutter, and J. E. Walker. 1994. Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria. Nature. 370:621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jault, J.-M., C. Dou, N. B. Grodsky, T. Matsui, M. Yoshida, and W. S. Allison. 1996. The α3β3γ subcomplex of the F1-ATPase from the thermophilic Bacillus PS3 with the βT165S substitution does not entrap inhibitory MgADP in a catalytic site during turnover. J. Biol. Chem. 271:28818–28824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsui, T., E. Muneyuki, M. Honda, W. S. Allison, C. Dou, and M. Yoshida. 1997. Catalytic activity of the α3β3γ complex of F1-ATPase without noncatalytic nucleotide binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 272:8215–8221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirono-Hara, Y., H. Noji, M. Nishiura, E. Muneyuki, K. Y. Hara, R. Yasuda, K. Kinosita Jr., and M. Yoshida. 2001. Pause and rotation of F1-ATPase during catalysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:13649–13654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noji, H., R. Yasuda, M. Yoshida, and K. Kinosita Jr. 1997. Direct observation of the rotation of F1-ATPase. Nature. 386:299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasuda, R., H. Noji, K. Kinosita Jr., and M. Yoshida. 1998. F1-ATPase is a highly efficient molecular motor that rotates with discrete 120° steps. Cell. 93:1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adachi, K., R. Yasuda, H. Noji, H. Itoh, Y. Harada, M. Yoshida, and K. Kinosita Jr. 2000. Stepping rotation of F1-ATPase visualized through angle-resolved single-fluorophore imaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:7243–7247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yasuda, R., H. Noji, M. Yoshida, K. Kinosita Jr., and H. Itoh. 2001. Resolution of distinct rotational substeps by submillisecond kinetic analysis of F1-ATPase. Nature. 410:898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adachi, K., K. Oiwa, T. Nishizaka, S. Furuike, H. Noji, H. Itoh, M. Yoshida, and K. Kinosita Jr. 2007. Coupling of rotation and catalysis in F1-ATPase revealed by single-molecule imaging and manipulation. Cell. 130:309–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimabukuro, K., R. Yasuda, E. Muneyuki, K. Y. Hara, K. Kinosita Jr., and M. Yoshida. 2003. Catalysis and rotation of F1 motor: cleavage of ATP at the catalytic site occurs in 1 ms before 40° substep rotation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:14731–14736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirakihara, Y., A. G. W. Leslie, J. P. Abrahams, J. E. Walker, T. Ueda, Y. Sekimoto, M. Kambara, K. Saika, Y. Kagawa, and M. Yoshida. 1997. The crystal structure of the nucleotide-free α3β3 subcomplex of F1-ATPase from the thermophilic Bacillus PS3 is a symmetric trimer. Structure. 5:825–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishizaka, T., K. Oiwa, H. Noji, S. Kimura, E. Muneyuki, M. Yoshida, and K. Kinosita Jr. 2004. Chemomechanical coupling in F1-ATPase revealed by simultaneous observation of nucleotide kinetics and rotation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Itoh, H., A. Takahashi, K. Adachi, H. Noji, R. Yasuda, M. Yoshida, and K. Kinosita Jr. 2004. Mechanically driven ATP synthesis by F1-ATPase. Nature. 427:465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, H., and G. Oster. 1998. Energy transduction in the F1 motor of ATP synthase. Nature. 396:279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibbons, C., M. G. Montgomery, A. G. W. Leslie, and J. E. Walker. 2000. The structure of the central stalk in bovine F1-ATPase at 2.4 Å resolution. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:1055–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwamoto, A., J. Miki, M. Maeda, and M. Futai. 1990. H+-ATPase γ subunit of Escherichia coli: role of the conserved carboxyl-terminal region. J. Biol. Chem. 265:5043–5048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sokolov, M., L. Lu, W. Tucker, F. Gao, P. A. Gegenheimer, and M. L. Richter. 1999. The 20 C-terminal amino acid residues of the chloroplast ATP synthase γ subunit are not essential for activity. J. Biol. Chem. 274:13824–13829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller, M., O. Pänke, W. Junge, and S. Engelbrecht. 2002. F1-ATPase, the C-terminal end of subunit γ is not required for ATP hydrolysis driven rotation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:23308–23313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hossain, M. D., S. Furuike, Y. Maki, K. Adachi, M. Y. Ali, M. Huq, H. Itoh, M. Yoshida, and K. Kinosita Jr. 2006. The rotor tip inside a bearing of a thermophilic F1-ATPase is dispensable for torque generation. Biophys. J. 90:4195–4203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Furuike, S., M. D. Hossain, Y. Maki, K. Adachi, T. Suzuki, A. Kohori, H. Itoh, M. Yoshida, and K. Kinosita Jr. 2008. Axle-less F1-ATPase rotates in the correct direction. Science. 319:955–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsui, T., and M. Yoshida. 1995. Expression of the wild-type and the Cys-/Trp-less α3β3γ complex of thermophilic F1-ATPase in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1231:139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monticello, R. A., E. Angov, and W. S. A. Brusilow. 1992. Effects of inducing expression of cloned genes for the F0 proton channel of the Escherichia coli F1F0 ATPase. J. Bacteriol. 174:3370–3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohta, S., M. Yohda, M. Ishizuka, H. Hirata, T. Hamamoto, Y. Otawara-Hamamoto, K. Matsuda, and Y. Kagawa. 1988. Sequence and over-expression of subunits of adenosine triphosphate synthase in thermophilic bacterium PS3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 933:141–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adachi, K., H. Noji, and K. Kinosita Jr. 2003. Single molecule imaging of the rotation of F1-ATPase. Methods Enzymol. 361B:211–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakaki, N., R. Shimo-Kon, K. Adachi, H. Itoh, S. Furuike, E. Muneyuki, M. Yoshida, and K. Kinosita Jr. 2005. One rotary mechanism for F1-ATPase over ATP concentrations from millimolar down to nanomolar. Biophys. J. 88:2047–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pänke, O., D. A. Cherepanov, K. Gumbiowski, S. Engelbrecht, and W. Junge. 2001. Visco-elastic dynamics of actin filaments coupled to rotary F-ATPase: angular torque profile of the enzyme. Biophys. J. 81:1220–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hausrath, A. C., R. A. Capaldi, and B. W. Matthews. 2001. The conformation of the ɛ- and γ-subunits within the Escherichia coli F1 ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:47227–47232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ni, Z.-L., H. Dong, and J.-M. Wei. 2005. N-terminal deletion of the γ subunit affects the stabilization and activity of chloroplast ATP synthase. FEBS J. 272:1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker, J. E., I. M. Fearnley, N. J. Gay, B. W. Gibson, F. D. Northrop, S. J. Powell, M. J. Runswick, M. Saraste, and V. L. J. Tybulewicz. 1985. Primary structure and subunit stoichiometry of F1-ATPase from bovine mitochondria. J. Mol. Biol. 184:677–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]