Abstract

Mucosal epithelial cells in the respiratory tract act as the first line of host innate defense against inhaled microbes by producing a range of molecules for clearance. In particular, epithelial mucins facilitate the mucociliary clearance by physically trapping the inhaled microbes. Up-regulation of mucin production thus represents an important host innate defense response against invading microbes. Excess mucin production, however, overwhelms the mucociliary clearance, resulting in defective mucosal defenses. Thus, tight regulation of mucin production is critical for maintaining an appropriate balance between beneficial and detrimental outcomes. Among various mechanisms, negative regulation plays an important role in tightly regulating mucin production. Here we show that the PAK4-JNK signaling pathway acted as a negative regulator for Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC mucin transcription. Moreover pneumolysin also selectively induced expression of MKP1 via a TLR4-dependent MyD88-TRAF6-ERK signaling pathway, which inhibited the PAK4-JNK signaling pathway, thereby leading to up-regulation of MUC5AC mucin production to maintain effective mucosal protection against S. pneumoniae infection. These studies provide novel insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the tight regulation of mucin overproduction in the pathogenesis of airway infectious diseases and may lead to development of new therapeutic strategies.

Inhaled microbes adhere to the mucosal surface in the upper respiratory tract and interact with host epithelial cells, resulting in activation of intracellular signaling pathways (1). Toll-like receptors (TLRs)3 on the surface of epithelial cells act as sensors for the invading pathogens, and mucosal epithelial cells produce diverse molecules including mucins, the major constituent of mucus secretions, which facilitate bacterial clearance from airways via the mucociliary escalator (2). Thus, up-regulation of mucins during infection represents a critical mucosal defense response (2). Excess mucin production, however, overwhelms the mucociliary clearance, contributing to airway obstruction and conductive hearing impairment in otitis media (3, 4). Thus, tight regulation of mucin production is critical for maintaining an appropriate balance between beneficial and detrimental outcomes. Among various mechanisms, negative regulation plays an important role in tightly regulating mucin production.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is an important human bacterial pathogen that colonizes the upper respiratory tract and causes potentially life-threatening pneumonia and the most common childhood disease otitis media (5). Among numerous known virulence factors, pneumolysin is a key virulence factor produced by virtually all clinical isolates and released during respiratory infections in humans by bacterial spontaneous autolysis (6). The pneumolysin serves as a potent inducer of host defense responses by activation of host complement and induction of immune cell-mediated inflammation (7, 8). In addition, we have reported previously that pneumolysin is also capable of up-regulating MUC5AC mucin gene expression (9). The molecular mechanisms underlying the tight regulation especially the negative regulation of S. pneumoniae-induced MUC5AC mucin transcription remain unknown.

To date, 11 mucins have been described to be expressed on surface mucous epithelial cells in the lungs. Among them, MUC5AC is considered to be the predominant mucin in airway mucus (10). In airway epithelial cells, numerous stimuli have been reported to induce MUC5AC expression. Those include inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, environmental pollutants such as cigarette smoke, and bacterial products such as LPS, peptidoglycan, flagellin, and pneumolysin (9, 11). Tumor necrosis factor-α has been shown to induce MUC5AC via ERK and p38-dependent signaling pathways (12), and phorbol esters such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate also activate MUC5AC expression through ERK signaling pathways (13). A cytoplasmic protein, P6, from nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae induces MUC5AC expression via TLR2-dependent p38 and NF-κB signaling pathways (14). Epidermal growth factor receptor is also known to play an important role in mediating MUC5AC induction by many stimuli such as cigarette smoke, phorbol esters, and bacterial products (13, 15, 16). Reactive oxygen species generated by cigarette smoke can also induce MUC5AC by JNK activation (17). In contrast to the relatively well known molecular mechanisms underlying the positive regulation of mucin up-regulation, little is known about the negative regulation of mucin induction in diseased conditions.

In the present study, we investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying the negative regulation of MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin. We show that pneumolysin activated the PAK4-JNK signaling pathway, which acted as a negative regulator for MUC5AC induction. Interestingly pneumolysin also induced MAPK phosphatase-1 (MKP1) expression in a TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6-ERK-dependent manner, and the increased MKP1 inhibited JNK signaling, thereby leading to the up-regulation of MUC5AC expression. Our data thus unveil a novel mechanism underlying the tight regulation especially the negative regulation of MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents—SP600125 was purchased from A. G. Scientific, Inc. Ro31-8220 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions—Clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae wild-type (WT) strain D39 were used in this study (18). D39 isogenic pneumolysin-deficient mutant was developed through insertion-duplication mutagenesis as described previously (19). S. pneumoniae was grown on chocolate agar plates and in Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (THY) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 water-jacketed incubator. The whole bacterial cells cultured in THY were harvested at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C to obtain a pellet after growth to early stationary phase. The bacterial pellet was suspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and the bacterial cell suspension was sonicated on ice three times at 150 watts for 3 min at 5-min intervals. Residual intact cells were removed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The bacterial lysate was stored at -80 °C, and 5 μg/ml lysate was used in all experiments.

Purification of Pneumolysin—His6 tag-fused pneumolysin was expressed in and purified from an Escherichia coli. Residual LPS was removed by passage over AffinityPak Detoxi-Gel (Endotoxin Removal Gel; Pierce) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell Culture—All media described below were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 100 units/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin. HM3 (human colon epithelial) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium H-21 (University of California Cell Culture Facility, San Francisco, CA), and mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen). WT MEF was provided by Dr. I. M. Verma (The Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA) (20). Tlr4Lps-d MEF was isolated from Tlr4Lps-d mutant mice (homozygous mice for the point mutation (Pro712 to His) in the Tlr4 gene) purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. HeLa (human cervix epithelial) cells were maintained in minimum Eagle's medium (American Type Culture Collection). HMEEC-1 (human middle ear epithelial) cells were maintained as described previously (21). All cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 water-jacketed incubator.

Plasmids, Transfections, and Luciferase Assays—The expression plasmids TLR4 dominant-negative (DN), WT TLR4, MyD88 DN, TRAF6 DN, JNK1 DN, JNK2 DN, ERK1 DN, PAK4 DN, a constitutively active form of PAK4 (PAK4 CA), MKP1 DN, and WT MKP1 have been described previously (9, 22, 23). The construct containing the 5′-flanking region of human MUC5AC gene was described previously (24). A MUC5AC thymidine kinase luciferase construct (300TK) was obtained by subcloning the MUC5AC promoter (base pair -3752/-3452) to upstream of the TK-32 promoter. The construct was confirmed by DNA sequencing. All of the transient transfections were carried out in triplicate using TransIT-LT1 reagent (Mirus, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's instructions. In all co-transfections, an empty vector was used as a control. Transfected cells were pretreated with chemical inhibitors for 1 h followed by pneumolysin treatment for 7 h prior to lysis for luciferase assay. The luciferase assay was carried out in triplicate, and luciferase activity was normalized with respect to β-galactosidase activity.

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA)—RNA-mediated interference for down-regulating JNK1, JNK2, PAK4, and MKP1 expressions was done by the transfection of siRNA-JNK1, siRNA-JNK2, siRNA-PAK4, and siRNA-MKP1 following the instructions of Invitrogen. siRNAs and siCONTROL Non-Targeting siRNA Pool were purchased from Dharmacon. 40–50% confluent cells were transfected with a final concentration of 100 nm siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). 40 h after the start of transfection, cells were treated with pneumolysin for the indicated time before being lysed for Western blot analysis and real time quantitative PCR.

Western Blot Analysis—Antibodies were used to analyze total cell lysates according to the manufacturers' instructions. Phospho-stress-activated protein kinase/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), stress-activated protein kinase/JNK, phospho-PAK4 (Ser474), and PAK4 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Monoclonal anti-β-actin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. MKP1 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay of MUC5AC Protein— MUC5AC protein released from cells was measured with slight modifications to the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay described previously (25). Briefly serial dilutions of each sample were plated in duplicate on 96-well microtiter plates and dried overnight at 40 °C. After washing, plates were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin overnight at 4 °C. To detect MUC5AC, antigen-coated wells were incubated with a 1:100 dilution of anti-mucin 5AC primary antibody (45M1, Neo Markers) for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing, the plates were incubated with a 1:10,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG for 1 h. Plates were incubated with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine peroxidase substrate (Bio-Rad), and the reaction was stopped with 1 n H2SO4. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The data were expressed as the percentage above base line on the same experimental day in HMEEC-1 cells.

Real Time Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) Analysis—Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent following the instructions of Invitrogen. Synthesis of complementary DNA from total RNA was performed with MultiScribe reverse transcriptase. Primers for human MUC5AC, PAK4, MKP1, MKP3, MKP5, and MKP7 and mouse Muc5ac have been described previously (9, 14, 22, 23, 26, 27). The remaining sequence information is as follows: human JNK1 primers, 5′-TGCCATCATGAGCAGAAGCAAACG-3′ and 5′-TCTGATTCTGAAATGGCCGGCTGA-3′; human JNK2 primers, 5′-GATATCTGGTCAGTGGGTTGCA-3′ and 5′-CAATATGGTCAGTGCCTTGGAA-3′; and mouse Mkp1 primers, 5′-ACAACAATGACTTGACCGCA-3′ and 5′-GGAATGGTTAATACTGGTGG-3′. Reactions were amplified and quantified using a 7500 Real-Time PCR System and the manufacturer's software (Applied Biosystems). Relative quantities of mRNAs were calculated using the comparative threshold cycle method and normalized using Predeveloped TaqMan Assay Reagent human cyclophilin (Applied Biosystems) and mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Applied Biosystems) as an endogenous control.

Animal Experiments—C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Rochester. In our mouse model of upper respiratory (middle ear) infections, the middle ears of anesthetized mice were inoculated transtympanically with D39 WT lysate (equivalent of 6.25 × 105 colony-forming units). Saline was inoculated as a control. Bullae were dissected from mice 9 h after inoculation and then subjected to Muc5ac and Mkp1 mRNA expression analysis by Q-PCR. For the inhibition study, mice were pretreated with SP600125 (0.25 mg/kg intraperitoneally) 1 h before S. pneumoniae lysate inoculation.

RESULTS

JNK Acts as a Negative Regulator for Pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC Mucin Transcription—Mucin plays an important role in innate defense response against bacterial infections. However, the molecular mechanism by which mucin is negatively regulated during pneumococcal infection remains unknown. Because MUC5AC has been identified as a prominent mucin in respiratory secretions and middle ear effusions, we focused on elucidating how MUC5AC induction is negatively regulated. Among various host signaling pathways, MAPKs have been shown to play important roles in mediating a variety of cellular responses (28). We have shown previously that ERK but not p38 signaling is required for pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC transcription (9). There is also evidence showing the opposing roles of ERK and JNK pathways (29). This led us to focus on investigating whether JNK acts as a negative regulator for pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC up-regulation. It should be noted that in the present study we assessed MUC5AC expression in a variety of human epithelial cell lines including human middle ear HMEEC-1, cervical HeLa, and colon HM3 cells. Previous studies have shown that MUC5AC expression is induced in all of these epithelial cell lines in response to S. pneumoniae, indicating that MUC5AC induction by S. pneumoniae may be generalizable to most human epithelial cells (9). To test our hypothesis, we first examined whether pneumolysin induces activation of JNK. As shown in Fig. 1A, pneumolysin induced phosphorylation of JNK in a time-dependent manner as assessed by Western blot analysis. We next investigated whether JNK acts as a negative regulator for MUC5AC induction by perturbing JNK signaling using various approaches. As shown in Fig. 1B, pretreatment with SP600125, a specific chemical inhibitor for JNK, resulted in 1.6-fold enhanced up-regulation of MUC5AC transcription by pneumolysin in HeLa cells. Next we confirmed the role of JNK in pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC transcription by using more specific approaches to inhibit JNK signaling. As shown in Fig. 1C, overexpressing dominant-negative JNK1 and JNK2 enhanced MUC5AC up-regulation at the transcriptional levels in all human epithelial cell lines tested including human epithelial HMEEC-1, HeLa, and HM3 cells, indicating that negative regulation of MUC5AC by JNK may be generalizable to most human epithelial cells. To further confirm the negative role of JNK, JNK1 and -2 knockdown using siRNA-JNK1 or -2 was carried out. Indeed JNK1 or -2 knockdown also enhanced MUC5AC expression, suggesting that JNK1/2 is critically involved in negatively regulating MUC5AC induction (Fig. 1D, right panels). The efficiency of siRNA-JNK1/2 in reducing endogenous JNK1/2 mRNA was also confirmed by real time Q-PCR analysis (Fig. 1D, left panels). Consistent with MUC5AC mRNA data, JNK1/2 knockdown also enhanced MUC5AC protein production in response to pneumolysin in HMEEC-1 cells as accessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Fig. 1E, right panels). The efficiency of siRNA-JNK1/2 in reducing endogenous JNK1/2 mRNA in HMEEC-1 cells was also confirmed by real time Q-PCR analysis (Fig. 1E, left panels). Consistent with these in vitro findings, induction of Muc5ac mRNA was also enhanced by SP600125 in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these data suggest that JNK indeed acts as a negative regulator for pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC expression in vitro and in vivo.

FIGURE 1.

JNK acts as a negative regulator for pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC mucin transcription. A, purified recombinant pneumolysin (Ply) induced phosphorylation of JNK in a time-dependent manner as assessed by performing Western blot analysis in HMEEC-1 cells. B, 1 μm SP600125 enhanced recombinant pneumolysin (100 ng/ml)-induced MUC5AC transcription in HeLa cells. C, overexpressing DN JNK1 and JNK2 enhanced pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC expression at transcriptional levels in HMEEC-1, HeLa, and HM3 cells. D, JNK1 or JNK2 knockdown by using siRNA-JNK1 or -2 (100 nm) enhanced MUC5AC expression at mRNA levels by pneumolysin (right panels) in HeLa cells. The efficiency of siRNA-JNK1 or -2 in reducing endogenous JNK1 or JNK2 mRNA was confirmed by performing real time Q-PCR (left panel). E, JNK1 or JNK2 knockdown by using siRNA-JNK1 or -2 (100 nm) enhanced MUC5AC expression at protein levels by pneumolysin (right panel) in HMEEC-1 cells. MUC5AC protein was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and expressed as percentage above base line. The efficiency of siRNA-JNK1 or -2 in reducing endogenous JNK1 or JNK2 mRNA was confirmed by performing real time Q-PCR (left panel). F, SP600125 (0.25 mg/kg intraperitoneally) enhanced S. pneumoniae lysate-induced Muc5ac mRNA expression in the middle ear of C57BL/6 mice in vivo. Data in A are representative of three separate experiments. Data in B–F are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 versus in the presence of only recombinant pneumolysin (B). *, p < 0.05 versus mock in the presence of recombinant pneumolysin (C–E). *, p < 0.05 versus in the presence of only S. pneumonia (F). **, p < 0.01 versus control group (D and E). p-JNK, phosphorylated JNK; CON, control.

PAK4 Acts Upstream of JNK in Negative Regulation of MUC5AC Induction by Pneumolysin—Because of the important role for PAK4 in mediating bacteria-induced activation of MAPKs (22), we next evaluated the role of PAK4 in MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin. We first examined whether pneumolysin induces activation of PAK4. As shown in Fig. 2A, pneumolysin induced phosphorylation of PAK4 in a time-dependent manner as assessed by Western blot analysis. Overexpressing dominant-negative PAK4 enhanced MUC5AC transcription in HMEEC-1 and HeLa cells, whereas overexpressing a constitutively active form of PAK4 (PAK4 CA) inhibited it (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that PAK4 is negatively involved in MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin. To further confirm the negative role of PAK4, PAK4 knockdown using siRNA-PAK4 was carried out. As shown in Fig. 2C, PAK4 knockdown also enhanced MUC5AC induction (Fig. 2C, right panel). The efficiency of siRNA-PAK4 in reducing endogenous PAK4 mRNA was confirmed by real time Q-PCR analysis (Fig. 2C, left panel). Thus, our data suggest that PAK4 also acts as a negative regulator for MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin. To further determine whether PAK4 acts upstream of JNK in negative regulation of MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin, we next assessed the effect of overexpressing dominant-negative PAK4 on pneumolysin-induced JNK activation. As shown in Fig. 2D, overexpressing PAK4 DN reduced JNK activation, thereby suggesting that PAK4 acts upstream of JNK in negative regulation of MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin.

FIGURE 2.

PAK4 acts upstream of JNK in negative regulation of MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin. A, purified recombinant pneumolysin (Ply) potently induced phosphorylation of PAK4 in a time-dependent manner as assessed by performing Western blot analysis in HMEEC-1 cells. B, overexpressing a dominant-negative PAK4 enhanced recombinant pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC expression at transcriptional levels in HMEEC-1 and HeLa cells, whereas overexpressing a constitutively active form of PAK4 (PAK4 CA) inhibited it. C, PAK4 knockdown by using siRNA-PAK4 (100 nm) enhanced MUC5AC expression at mRNA levels by recombinant pneumolysin (right panel) in HeLa cells. The efficiency of siRNA-PAK4 in reducing endogenous PAK4 mRNA was confirmed by performing real time Q-PCR (left panel). D, phosphorylation of JNK by recombinant pneumolysin was reduced by overexpressing a dominant-negative PAK4 in HeLa cells. Data in A and D are representative of three separate experiments. Data in B and C are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 versus mock in the presence of recombinant pneumolysin (B and C). **, p < 0.01 versus control group (C). p-PAK4, phosphorylated PAK4; p-JNK, phosphorylated JNK; CON, control.

Pneumolysin Induces Activation of PAK4-JNK Pathway via TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6—We have reported previously that the TLR4-dependent MyD88-TRAF6 signaling pathway is required for MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin (9). In addition, it was also reported that pneumolysin induces tumor necrosis factor-α and IL-6 production via TLR4 (30). Thus, we hypothesized that pneumolysin may induce activation of PAK4 and JNK via the TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6 pathway. To test our hypothesis, we first assessed the effect of perturbing TLR4 signaling. As shown in Fig. 3A, overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant of TLR4 inhibited pneumolysin-induced PAK4 and JNK activation. The requirement of TLR4 in PAK4 activation was also confirmed by TLR4 knockdown using TLR4 siRNA (data not shown). Moreover overexpressing dominant-negative mutants of MyD88 and TRAF6 inhibited pneumolysin-induced PAK4 and JNK activation (Fig. 3, B and C). Collectively these data demonstrate that the TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6 pathway is required for activation of PAK4 and JNK by pneumolysin.

FIGURE 3.

Pneumolysin induces activation of PAK4-JNK pathway via TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6. A–C, overexpressing a dominant-negative TLR4 (A), MyD88 (B), and TRAF6 (C) reduced phosphorylation of PAK4 and JNK in HeLa cells. Data in A–C are representative of three separate experiments. p-PAK4, phosphorylated PAK4; p-JNK, phosphorylated JNK.

MKP1 Acts as a Positive Regulator for Pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC Mucin Transcription—Up-regulation of mucins in infectious disease represents an important host innate defense response against invading microbes (2). Excess mucin production, however, overwhelms the mucociliary escalator, contributing to airway obstruction. Thus, tight regulation of mucin expression is critical for balancing beneficial and detrimental effects of mucin production. Because our data already demonstrated that phosphorylation and activation of JNK is negatively involved in MUC5AC induction, we next investigated whether MKP1, a critical phosphatase for dephosphorylating JNK, is involved in regulating MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin. We first investigated whether pretreatment with Ro31-8220, a specific chemical inhibitor for MKP1 expression, attenuates induction of MUC5AC by pneumolysin. As shown in Fig. 4A, pretreatment with Ro31-8220 significantly reduced pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC transcription, indicating the positive involvement of MKP1 in MUC5AC induction. We next confirmed the role of MKP1 in pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC transcription by using more specific approaches. As shown in Fig. 4B, overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant of MKP1 reduced MUC5AC transcription, whereas overexpressing wild-type MKP1 enhanced it. To further confirm the requirement of MKP1, MKP1 knockdown using siRNA-MKP1 was carried out. As shown in Fig. 4C (right panel), MKP1 knockdown reduced MUC5AC expression. The efficiency of siRNA-MKP1 in reducing endogenous MKP1 mRNA was confirmed by performing real time Q-PCR analysis (Fig. 4C, left panel). These data suggest that MKP1 acts as a positive regulator for MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin.

FIGURE 4.

MKP1 acts as a positive regulator for pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC mucin transcription. A, 2.5 μm Ro31-8220 reduced recombinant pneumolysin (Ply) (100 ng/ml)-induced MUC5AC transcription in HeLa cells. B, overexpressing a dominant-negative MKP1 inhibited recombinant pneumolysin-induced MUC5AC expression at transcriptional levels in HeLa cells, whereas overexpressing a wild-type MKP1 enhanced it. C, MKP1 knockdown by using siRNA-MKP1 (100 nm) reduced MUC5AC induction at mRNA levels by recombinant pneumolysin (right panel) in HeLa cells. The efficiency of siRNA-MKP1 in reducing endogenous MKP1 mRNA was confirmed by performing real time Q-PCR (left panel). D, overexpressing wild-type MKP1 reduced recombinant pneumolysin-induced JNK phosphorylation. E, MKP1 knockdown by using siRNA-MKP1 (100 nm) increased JNK phosphorylation by recombinant pneumolysin (lower panel) in HeLa cells. The efficiency of siRNA-MKP1 in reducing endogenous MKP1 protein was confirmed by performing Western blot analysis (upper panel). Data in A–C are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Data in D and E are representative of three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus in the presence of only recombinant pneumolysin (A). *, p < 0.05 versus mock in the presence of recombinant pneumolysin (B and C). **, p < 0.01 versus control group (C). CON, control; p-JNK, phosphorylated JNK.

We demonstrated that MKP1 acts as a positive regulator for MUC5AC induction, whereas JNK acts as a negative regulator for MUC5AC induction. Still unknown was whether MKP1 is positively involved in MUC5AC induction by inhibiting JNK phosphorylation. To test our hypothesis, we first determined whether overexpressing wild-type MKP1 reduced JNK phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 4D, pneumolysin-induced JNK phosphorylation was reduced by overexpressing wild-type MKP1. Next we assessed the effect of MKP1 knockdown on pneumolysin-induced JNK phosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 4E (lower panel), MKP1 knockdown increased JNK phosphorylation induced by pneumolysin. The efficiency of siRNA-MKP1 in reducing endogenous MKP1 protein was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4E, upper panel). Together these data suggest that MKP1 acts as a positive regulator by deactivating JNK signaling.

MKP1 Expression Is Induced by Pneumolysin—Having demonstrated that MKP1 was positively involved in MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin, it was still unknown whether pneumolysin also induces MKP1. As shown in Fig. 5A, pneumolysin specifically induced expression of MKP1 but not MKP3, -5, and -7 in HeLa cells. To further determine whether pneumolysin also induces MKP1 in other epithelial cell line, WT S. pneumoniae strain D39 and its isogenic pneumolysin-deficient mutant were compared in their MKP1-inducing activity in human middle ear HMEEC-1 cells. As shown in Fig. 5B, D39 WT and purified pneumolysin equally potently induced MKP1 transcription, whereas the pneumolysin-deficient mutant did not, indicating that pneumolysin is required for MKP1 induction. Consistent with these in vitro findings, induction of Mkp1 mRNA by S. pneumoniae strain D39 WT was also confirmed in C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 5C). In addition to the up-regulation of MKP1 at the mRNA level, induction of MKP1 by pneumolysin was also observed at the protein level by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5D). Collectively we conclude from these data that pneumolysin induces MKP1 expression in vitro and in vivo.

FIGURE 5.

MKP1 expression is induced by pneumolysin. A, recombinant pneumolysin (Ply) (100 ng/ml) induced MKP1 but not MKP3, -5, and -7 at the mRNA level in HeLa cells. B, MKP1 transcription was induced by D39 WT and recombinant pneumolysin (100 ng/ml) but not by pneumolysin-deficient mutant (Ply mt) in HMEEC-1 cells. C, D39 WT induced Muc5ac mRNA expression in the middle ear of C57BL/6 mice in vivo. D, purified recombinant pneumolysin induced MKP1 expression as assessed by performing Western blot analysis in HMEEC-1 cells. Data in A–C are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Data in D are representative of three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus control group (A–C). **, p > 0.05 versus control group (A and B). CON, control.

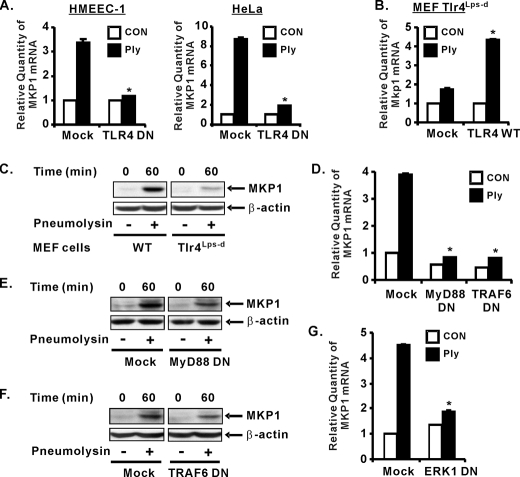

TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6-ERK Signaling Is Required for MKP1 Induction by Pneumolysin—We next investigated whether the TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6 pathway also mediates MKP1 induction. We first investigated whether TLR4 is involved in mediating MKP1 induction at the mRNA levels. As shown in Fig. 6A, overexpressing dominant-negative TLR4 reduced MKP1 expression at the mRNA levels in both HMEEC-1 and HeLa cells. Moreover overexpressing wild-type TLR4 markedly increased Mkp1 expression at the mRNA levels in TLR4-deficient Tlr4Lps-d MEF cells (Fig. 6B). To further confirm the involvement of TLR4 in MKP1 induction at the protein levels, we compared pneumolysin-induced MKP1 expression in wild-type and Tlr4Lps-d MEF cells by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 6C, MKP1 protein expression was greatly reduced in Tlr4Lps-d MEF cells compared with wild-type cells. Next we investigated whether MyD88 and TRAF6 are also involved in mediating pneumolysin-mediated MKP1 expression. As shown in Fig. 6D, overexpressing dominant-negative MyD88 and TRAF6 reduced MKP1 expression at the mRNA levels. Similarly perturbing MyD88-TRAF6 signaling also reduced the MKP1 expression at the protein levels (Fig. 6, E and F). We showed previously that ERK acts downstream of TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6 in regulating induction of MUC5AC by pneumolysin (9). Thus, we examined whether ERK is also required for MKP1 induction by pneumolysin. As shown in Fig. 6G, overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant of ERK1 inhibited MKP1 induction by pneumolysin. Together our data suggest that the TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6-ERK pathway is required for MKP1 induction by pneumolysin, which in turn deactivates JNK and results in up-regulation of MUC5AC expression.

FIGURE 6.

TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6-ERK signaling is required for MKP1 induction by pneumolysin. A, overexpressing a dominant-negative TLR4 reduced recombinant pneumolysin (Ply)-induced MKP1 expression at mRNA levels in HMEEC-1 and HeLa cells. B, overexpressing wild-type TLR4 in Tlr4Lps-d MEFs markedly enhanced Mkp1 expression at the mRNA level. C, induction of MKP1 by recombinant pneumolysin (100 ng/ml) was reduced in Tlr4Lps-d MEF cells compared with wild-type MEFs. D, overexpressing a dominant-negative MyD88 and TRAF6 reduced recombinant pneumolysin-induced MKP1 expression at mRNA levels in HeLa cells. E and F, overexpressing a dominant-negative MyD88 (E) and TRAF6 (F) reduced expression of MKP1 in HeLa cells. G, overexpressing a dominant-negative ERK1 reduced recombinant pneumolysin-induced MKP1 expression at mRNA levels in HeLa cells. Data in A, B, D, and G are expressed as mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Data in C, E, and F are representative of three separate experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus mock in the presence of recombinant pneumolysin (A, B, D, and G). CON, control.

DISCUSSION

Pneumococcal pneumolysin is a key cytoplasmic virulence protein well conserved among all clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae. Here we showed that the pneumolysin stimulates diverse signaling intermediates involved in the regulation of MUC5AC mucin gene expression. Pneumolysin activated JNK via the TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6-dependent PAK4 signaling pathway, which acts as a critical negative regulator for MUC5AC induction. Interestingly pneumolysin also induced MKP1 expression via the TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6-ERK signaling pathway. The induced MKP1 deactivates JNK, which in turn leads to up-regulation of MUC5AC expression (9). Thus, our studies provide novel insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the tight regulation of mucin overproduction in the pathogenesis of airway infectious diseases and may lead to development of new therapeutic strategies (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Schematic representation of tight regulation of MUC5AC mucin induction by pneumolysin via PAK4-JNK and MKP1 signaling pathways. As indicated, the PAK4-JNK signaling pathway negatively regulates MUC5AC induction by recombinant pneumolysin in a TLR4-dependent manner. Interestingly induction of MKP1 appears to be crucial for inhibiting JNK activation. Our data thereby unveil a complex signaling mechanism underlying tight regulation of MUC5AC mucin by pneumococcal pneumolysin.

Pneumolysin is a multifunctional protein possessing both pore-forming cytolytic and immunomodulatory properties (31). Pneumolysin is thought to be present at relatively low concentrations early in infection when it mediates both immunomodulatory effects and low sublytic activities (7, 8). Later in infection, pneumolysin rises to lytic concentrations at which it mainly forms membrane pores that cause direct cellular and tissue damage, promoting widespread pneumococcal dissemination (32). In the previous study, we found that 100–200 ng/ml doses of pneumolysin induce high MUC5AC expression via TLR4-dependent activation of ERK, and this concentration causes about 5–25% cytotoxicity as measured by lactate dehydrogenase release assay (9). In this study, we used a 100 ng/ml dose of pneumolysin, which caused less than 10% cytotoxicity as measured by lactate dehydrogenase release assay (data not shown). Moreover pneumolysin was found to be involved in activating the TLR4-dependent JNK signaling pathway in this study. LPS is a well known bacterial toxin that interacts with TLR4 to initiate downstream signaling pathways. To eliminate possible contamination of LPS during the purification of recombinant pneumolysin from E. coli, the pneumolysin used for this study was filtered through AffinityPak Detoxi-Gel to remove residual LPS. In addition, the pneumolysin was also pretreated with polymyxin B, a well characterized LPS inhibitor (data not shown). Thus it is evident that it is the pneumolysin but not LPS that initiates TLR4-MyD88-TRAF6-dependent signaling cascades leading to activation of PAK4-JNK and up-regulation of MKP1. It should also be noted that His-tagged recombinant pneumolysin purified from E. coli was used in the present study. A native pneumolysin was previously purified from S. pneumoniae (30). However, it is difficult and time-consuming to obtain a sufficient amount of native pneumolysin. For these reasons, a recombinant His6-tagged pneumolysin was purified from E. coli (48). Interestingly no difference was found between the recombinant pneumolysin and the native pneumolysin in terms of their ability to interact with TLR4 as well as cytotoxicity. In our studies, we compared this His-tagged pneumolysin with the native pneumolysin on their ability to induce MUC5AC transcription (9). No difference was found in MUC5AC induction, suggesting that recombinant pneumolysin behaves identically to the native pneumolysin obtained from S. pneumoniae.

MAPKs have been well studied and are known to be important signaling molecules diversely involved in regulating mucin gene expression. In contrast to the positive involvement of MAPKs in regulating MUC5AC expression, little is known about the negative involvement of MAPKs in MUC5AC induction. Here we identified a critical role of JNK signaling in negatively regulating MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin. This finding is in line with the previous report that tumor necrosis factor-α-induced MUC2 up-regulation is reduced by the activation of JNK (33) but in contrast with a report that JNK and ERK are positively involved in inducing MUC4 gene expression by activating PEA3 transcription factor (34). In addition to MUC4, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate-induced MUC5AC expression was also found to be mediated by activating both JNK and ERK signaling pathways (35). Moreover reactive oxygen species generated by cigarette smoke also induces MUC5AC expression by JNK activation (17). Thus, it may well be that the exact role of JNK in mucin induction is inducer- or cell type-dependent.

PAKs have been shown to be involved in regulating diverse cellular responses such as controlling cell morphology and motility, modulating proapoptotic or antiapoptotic properties, and activating MAPK signaling pathways (36–38). We showed that PAK4 acts as an upstream kinase for JNK activation and is negatively involved in MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin (Fig. 2). This finding is in line with a previous report that JNK phosphorylation was reduced by PAK4 knockdown (39). On the other hand, there is also evidence showing that PAK4 is a relatively weak activator of JNK and p38 signaling pathways (40). We also found that PAK4 is a weak inducer for p38 activation in response to pneumolysin (data not shown). It appears that kinase activity of PAK4 may play a more important role in JNK activation in response to bacteria components such as pneumolysin.

As shown in Fig. 5A, pneumolysin specifically induced expression of MKP1 but not MKP3, MKP5, and MKP7. MKP3 is known to selectively dephosphorylate ERK (41), and MKP5 and MKP7 exhibit preference for dephosphorylating JNK but not ERK (42, 43). MKP1, also termed DUSP1, is known to be a key negative regulator of TLR-induced inflammation in vivo (44, 45) and specifically inactivates JNK and ERK (46, 47). The duration and timing of MKP1 expression may account for its role in positive regulation of mucin gene expression. Our kinetic studies showed that MKP1 expression peaked at 1 h after treatment with pneumolysin and declined gradually thereafter. Interestingly the induction of MUC5AC began to increase at 3 h after treatment with pneumolysin and peaked at 5 h. We have already shown that ERK and JNK act as a positive and negative regulator, respectively. ERK activation occurs at early time point, whereas JNK activation occurs at later time points, which serves as a key mechanism to negatively regulate mucin. Thus, MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin is relatively weak at early time points because MKP1 mainly targets and inactivates ERK, the positive regulator of MUC5AC induction. At later time points, MKP1 inactivates JNK, the negative regulator for MUC5AC induction. It was reported previously that MKP1 preferentially inactivates JNK rather than ERK (46, 47). This may explain the increased induction of MUC5AC at later time points.

In the present study, we showed that MUC5AC mucin expression is tightly regulated in response to pneumolysin via positive MKP1 and negative PAK4-JNK signaling pathways. Both pathways appear to be mediated by the same TLR4-dependent MyD88-TRAF6 signaling pathway. These findings suggested that pneumolysin is able to cause a net up-regulation of MUC5AC production by inducing MKP1 expression, which counterbalances the suppressive effect of the JNK signaling. It is still unclear how kinase activity of JNK is negatively involved in induction of MUC5AC. Future studies will focus on elucidating the detailed molecular mechanism underlying the negative regulation of MUC5AC induction by pneumolysin. Nonetheless our studies unveil a novel complex signaling mechanism involved in both the positive and negative regulation of host mucosal defense response to pneumococcal infection. It may help to developing new therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Li laboratory for helpful discussion and suggestions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DC004562 and DC005843 (to J.-D. L.) and Training Grant DC008703 (to U.-H. H.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TLR, Toll-like receptor; MyD88, myeloid differentiation factor 88; TRAF6, tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase; MAPK, serine/threonine mitogen-activated protein kinase; PAK, p21-activated kinase; MKP, MAPK phosphatase; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; DN, dominant-negative; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; siRNA, small interfering RNA; Q-PCR, quantitative PCR; WT, wild-type.

References

- 1.Kopp, E., and Medzhitov, R. (2003) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15 396-401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowles, M. R., and Boucher, R. C. (2002) J. Clin. Investig. 109 571-577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose, M. C., Nickola, T. J., and Voynow, J. A. (2001) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 25 533-537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Majima, Y., Hamaguchi, Y., Hirata, K., Takeuchi, K., Morishita, A., and Sakakura, Y. (1988) Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 97 272-274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klugman, K. P., and Feldman, C. (2001) Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 14 173-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benton, K. A., Everson, M. P., and Briles, D. E. (1995) Infect. Immun. 63 448-455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell, T. J., Andrew, P. W., Saunders, F. K., Smith, A. N., and Boulnois, G. J. (1991) Mol. Microbiol. 5 1883-1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cockeran, R., Theron, A. J., Steel, H. C., Matlola, N. M., Mitchell, T. J., Feldman, C., and Anderson, R. (2001) J. Infect. Dis. 183 604-611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha, U., Lim, J. H., Jono, H., Koga, T., Srivastava, A., Malley, R., Pages, G., Pouyssegur, J., and Li, J. D. (2007) J. Immunol. 178 1736-1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose, M. C., and Voynow, J. A. (2006) Physiol. Rev. 86 245-278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borchers, M. T., Carty, M. P., and Leikauf, G. D. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 276 L549-L555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song, K. S., Lee, W. J., Chung, K. C., Koo, J. S., Yang, E. J., Choi, J. Y., and Yoon, J. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 23243-23250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewson, C. A., Edbrooke, M. R., and Johnston, S. L. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 344 683-695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, R., Lim, J. H., Jono, H., Gu, X. X., Kim, Y. S., Basbaum, C. B., Murphy, T. F., and Li, J. D. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324 1087-1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeyama, K., Dabbagh, K., Lee, H. M., Agusti, C., Lausier, J. A., Ueki, I. F., Grattan, K. M., and Nadel, J. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 3081-3086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeyama, K., Jung, B., Shim, J. J., Burgel, P. R., Dao-Pick, T., Ueki, I. F., Protin, U., Kroschel, P., and Nadel, J. A. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. 280 L165-L172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gensch, E., Gallup, M., Sucher, A., Li, D., Gebremichael, A., Lemjabbar, H., Mengistab, A., Dasari, V., Hotchkiss, J., Harkema, J., and Basbaum, C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 39085-39093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briles, D. E., Crain, M. J., Gray, B. M., Forman, C., and Yother, J. (1992) Infect. Immun. 60 111-116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry, A. M., Yother, J., Briles, D. E., Hansman, D., and Paton, J. C. (1989) Infect. Immun. 57 2037-2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, Q., Estepa, G., Memet, S., Israel, A., and Verma, I. M. (2000) Genes Dev. 14 1729-1733 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chun, Y. M., Moon, S. K., Lee, H. Y., Webster, P., Brackmann, D. E., Rhim, J. S., and Lim, D. J. (2002) Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 111 507-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, Y., Mikami, F., Jono, H., Zhang, W., Weng, X., Koga, T., Xu, H., Yan, C., Kai, H., and Li, J. D. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 359 691-696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakai, A., Han, J., Cato, A. C., Akira, S., and Li, J. D. (2004) BMC Mol. Biol. 5 2-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, D., Gallup, M., Fan, N., Szymkowski, D. E., and Basbaum, C. B. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 6812-6820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgel, P. R., Lazarus, S. C., Tam, D. C., Ueki, I. F., Atabai, K., Birch, M., and Nadel, J. A. (2001) J. Immunol. 167 5948-5954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jono, H., Xu, H., Kai, H., Lim, D. J., Kim, Y. S., Feng, X. H., and Li, J. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 27811-27819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imasato, A., Desbois-Mouthon, C., Han, J., Kai, H., Cato, A. C., Akira, S., and Li, J. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 47444-47450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garrington, T. P., and Johnson, G. L. (1999) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 11 211-218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xia, Z., Dickens, M., Raingeaud, J., Davis, R. J., and Greenberg, M. E. (1995) Science 270 1326-1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malley, R., Henneke, P., Morse, S. C., Cieslewicz, M. J., Lipsitch, M., Thompson, C. M., Kurt-Jones, E., Paton, J. C., Wessels, M. R., and Golenbock, D. T. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 1966-1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell, T. J., and Andrew, P. W. (1997) Microb. Drug Resist. 3 19-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilbert, R. J., Jimenez, J. L., Chen, S., Tickle, I. J., Rossjohn, J., Parker, M., Andrew, P. W., and Saibil, H. R. (1999) Cell 97 647-655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahn, D. H., Crawley, S. C., Hokari, R., Kato, S., Yang, S. C., Li, J. D., and Kim, Y. S. (2005) Cell Physiol. Biochem. 15 29-40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez, A., Barco, R., Fernandez, I., Price-Schiavi, S. A., and Carraway, K. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 36942-36952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato, S., Hokari, R., Crawley, S., Gum, J., Ahn, D. H., Kim, J. W., Kwon, S. W., Miura, S., Basbaum, C. B., and Kim, Y. S. (2006) Int. J. Oncol. 29 33-40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gnesutta, N., Qu, J., and Minden, A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 14414-14419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schurmann, A., Mooney, A. F., Sanders, L. C., Sells, M. A., Wang, H. G., Reed, J. C., and Bokoch, G. M. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 453-461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bagrodia, S., and Cerione, R. A. (1999) Trends Cell Biol. 9 350-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li, X., and Minden, A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 41192-41200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abo, A., Qu, J., Cammarano, M. S., Dan, C., Fritsch, A., Baud, V., Belisle, B., and Minden, A. (1998) EMBO J. 17 6527-6540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muda, M., Theodosiou, A., Rodrigues, N., Boschert, U., Camps, M., Gillieron, C., Davies, K., Ashworth, A., and Arkinstall, S. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 27205-27208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanoue, T., Moriguchi, T., and Nishida, E. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 19949-19956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masuda, K., Shima, H., Watanabe, M., and Kikuchi, K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 39002-39011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chi, H., Barry, S. P., Roth, R. J., Wu, J. J., Jones, E. A., Bennett, A. M., and Flavell, R. A. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 2274-2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salojin, K. V., Owusu, I. B., Millerchip, K. A., Potter, M., Platt, K. A., and Oravecz, T. (2006) J. Immunol. 176 1899-1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farooq, A., and Zhou, M. M. (2004) Cell. Signal. 16 769-779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franklin, C. C., and Kraft, A. S. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 16917-16923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Srivastava, A., Henneke, P., Visintin, A., Morse, S. C., Martin, V., Watkins, C., Paton, J. C., Wessels, M. R., Golenbock, D. T., and Malley, R. (2005) Infect. Immun. 73 6479-6487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]